Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic demanded exceptional physical and mental effort from healthcare workers worldwide. Since healthcare workers often refrain from seeking professional psychological support, internet-delivered interventions could serve as a viable alternative option.

Objective

We aimed to investigate the effects of a therapist-guided six-week CBT-based internet-delivered stress recovery intervention among medical nurses using a randomized controlled trial design. We also aimed to assess program usability.

Methods

168 nurses working in a healthcare setting (Mage = 42.12, SDage = 11.38; 97 % female) were included in the study. The intervention group included 77 participants, and the waiting list control group had 91 participants. Self-report data were collected online at three timepoints: pre-test, post-test, and three-month follow-up. The primary outcome was stress recovery. Secondary outcomes included measures of perceived stress, anxiety and depression symptoms, psychological well-being, posttraumatic stress and complex posttraumatic stress symptoms, and moral injury.

Results

We found that the stress recovery intervention FOREST improved stress recovery, including psychological detachment (d = 0.83 [0.52; 1.15]), relaxation (d = 0.93 [0.61, 1.25]), mastery (d = 0.64 [0.33; 0.95]), and control (d = 0.46 [0.15; 0.76]). The effects on psychological detachment, relaxation, and mastery remained stable at the three month follow-up. The intervention was also effective in reducing its users' stress (d = − 0.49 [− 0.80; − 0.18]), anxiety symptoms (d = − 0.31 [− 0.62; − 0.01]), depression symptoms (d = − 0.49 [− 0.80; − 0.18]) and increasing psychological well-being (d = 0.53 [0.23; 0.84]) with the effects on perceived stress, depression symptoms, and well-being remaining stable at the three-month follow-up. High user satisfaction and good usability of the intervention were also reported.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated that an internet-based intervention for healthcare staff could increase stress recovery skills, promote psychological well-being, and reduce stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms, with most of the effects being stable over three months.

Trial registration

NCT04817995 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04817995). Registration date: March 30, 2021. Date of first recruitment: April 1, 2021.

Keywords: Efficacy, Internet-based intervention, Nurses, RCT, Stress recovery

What is already known

-

•

The COVID-19 pandemic demanded exceptional physical and mental efforts from healthcare workers worldwide.

-

•

There is some evidence that internet-delivered programs targeting various mental health components might be effective in healthcare professionals' sample.

-

•

However, no efficacy studies on stress recovery have been conducted with healthcare workers.

What this paper adds

-

•

The present study demonstrated that an internet-based intervention for healthcare staff could increase stress recovery skills, promote psychological well-being, and reduce stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms, with most of the effects being stable over three months.

-

•

Participants assessed the intervention as very good, and their satisfaction with the program was high.

-

•

Since healthcare workers face various emotional challenges and seldom seek professional psychological support, an internet-based stress recovery intervention could be a feasible option for increasing the well-being of medical nurses.

1. Background

The COVID-19 pandemic demanded exceptional physical and mental efforts from healthcare workers worldwide. A significant number of healthcare workers experienced medium to high emotional load or extremely acute stress (Mira et al., 2020). Additionally, many reported psychological symptoms, including anxiety, fear, distress, and depression, leading to stress-related conditions and insomnia (Chow et al., 2020). Distress factors comprised quarantine, heavy workload, the fear of infecting themselves and their family members, witnessing patients' poor and deteriorating conditions, and the requirement to wear protective gear (Chow et al., 2020). Also, the presence of trauma-related stress among healthcare staff ranged between 7.4 and 35 %. In particular, this occurred among women, nurses, frontline workers, and workers who experienced physical symptoms (Benfante et al., 2020). Moreover, a significant proportion of healthcare professionals began to consider a career change, and this ideation was related to higher levels of depression, stress, anxiety, and lower psychological well-being (Norkiene et al., 2021). This context highlights the need for psychosocial support for healthcare workers targeted at recovery from stressful experiences.

Since healthcare workers face various emotional challenges as well as trauma related to the specifics of their work and seldom seek professional psychological support, often due to the mental health stigma (Mehta and Edwards, 2018; Knaak et al., 2017; Søvold et al., 2021), internet-delivered interventions could serve as a viable alternative option for providing psychological services. There is some evidence from previous randomized controlled trials that internet-delivered programs targeting various mental health components might be effective in both healthcare professionals and other non-clinical samples. Among healthcare professionals, internet-delivered programs showed potential in equipping participants with coping skills to manage stress (Morrison Wylde et al., 2017), reducing stress levels (Gollwitzer et al., 2018), improving some components of well-being (Smoktunowicz et al., 2021), and enhancing work engagement (Gollwitzer et al., 2018; Sasaki et al., 2021). A decrease in perceived stress (Heber et al., 2016) and changes in anxiety, depression, productivity, and academic work impairment (Harrer et al., 2018), among other positive outcomes, have also been observed in other adult samples.

However, to the best of our knowledge, no efficacy studies on stress recovery have been conducted with healthcare workers. Stress recovery refers to a process during which individual functional systems that have been called upon during a stressful experience return to their prestress levels (Meijman and Mulder, 1998). An understanding of successful recovery experiences highlights the importance of refraining from work demands and avoiding activities that call upon the same functional systems or internal resources as those required at work. Alternatively, gaining new internal resources such as energy, self-efficacy, or positive mood should also help restore threatened resources (Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007). Using a data-driven approach, four distinct recovery experiences have been differentiated: psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, and control (Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007). Psychological detachment refers to refraining from being occupied by work-related duties and disengaging oneself mentally from work. Relaxation is a process that contrasts psychological strains and is often associated with leisure activities. Mastery experiences imply off-job activities that distract from the job and provide challenging experiences and learning opportunities in other domains. Control refers to the degree to which a person can decide which activity to pursue during leisure time and when and how to pursue this activity (Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007).

Although there is some research on internet-based stress intervention programs, and evidence suggests that they are effective in reducing stress within the healthcare staff and other samples, no randomized controlled trials have assessed whether internet-delivered interventions can improve stress recovery. High physical and emotional load among healthcare workers, especially in the context of difficult pandemic conditions, highlights the need for brief and easily accessible interventions that help reduce stress, which is inevitable during extreme pandemic conditions. Interventions should also enhance stress recovery skills, which could equip medical personnel with relevant psychological resources to sustain the effects of stress reduction. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the effects of an internet-based stress recovery intervention on stress recovery skills among nurses in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic using a randomized controlled trial design and comparing the intervention group with a waiting list control group. We also aimed to investigate the effects of the intervention on perceived stress, anxiety and depression symptoms, psychological well-being, posttraumatic stress and complex posttraumatic stress symptoms, and moral injury. Additionally, we aimed to assess the usability of the stress recovery intervention.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

A two-armed randomized controlled trial was conducted in Lithuania, comparing the six-week online intervention FOREST participants against a waiting list control group. We randomly allocated participants to the intervention or the waiting list control group (allocation ratio 1:1). Participants assigned to the intervention group received the intervention immediately after randomization, whereas participants in the waiting list control group received the same intervention six months later. Assessments took place at three-time points: pre-test T1 (April/2021), post-test T2 (June–July/2021), and 3-month follow-up T3 (September–October/2021). Self-report data were collected using a secure encrypted treatment platform – Iterapi (Vlaescu et al., 2016). All procedures involved in the trial were consistent with the ethical standards. The study was approved by Vilnius University Psychology Research Ethics Committee (Reference No. 2021-03-22/61). The trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04817995, March 30, 2021). In the current study, the data were reported following the CONSORT statement for reporting parallel group trials (Schulz et al., 2011).

2.2. Participants

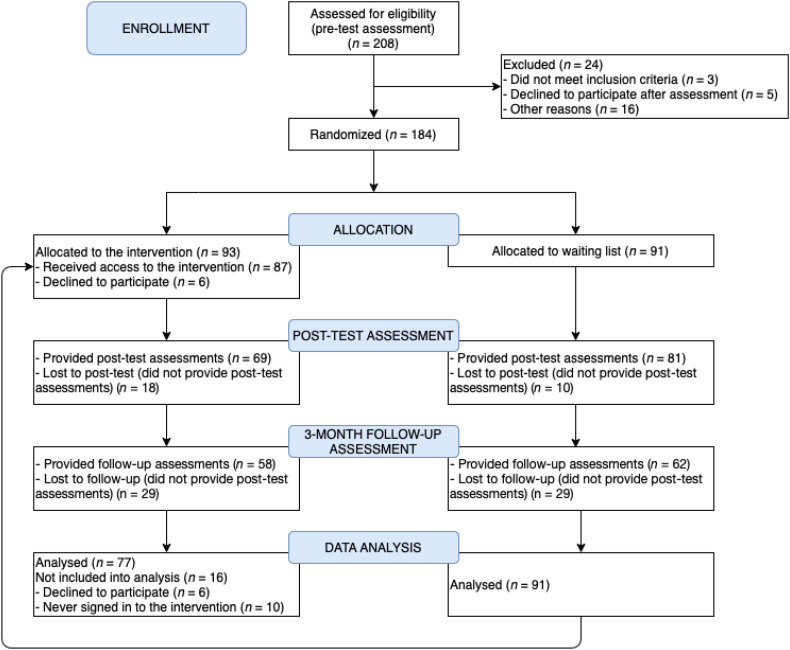

Participants were enrolled after disseminating invitations to participate in the program through social networks of nurses, healthcare institutions, and press releases to national media throughout the whole country. Recruitment was carried out in April/2021 (date of first recruitment: April 1, 2021). Individuals interested in participation registered on the study website www.forestmedikams.lt, where all the information about the study was presented. Potential participants were informed about the length of the program, its overall structure, and each module's structure; it was also highlighted that the program is internet-based, delivered remotely, and the intensity of the program can be chosen by the participants themselves. Participants provided informed consent and completed pre-test assessment questionnaires during the online registration. After registration, individuals who fully completed the online pre-test assessment were contacted by phone for a brief interview to finalize their eligibility for the current study; also, their questions regarding the program and all the procedures were answered. A flowchart of the study is presented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study.

To be included in the study, participants had to be nurses working in a healthcare setting, at least 18 years old, comprehend Lithuanian, and have a device with an Internet connection. Predefined exclusion criteria were an acute psychiatric crisis, high suicide risk, alcohol/drug addiction, and interpersonal violence.

2.3. Randomization

Eligible participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention or the waiting list control group. Randomization was conducted by a researcher not associated with the current study using the random number calculation procedure (www.random.org). No stratification was applied. Before registering for the study, participants were informed that they would get access to the intervention either in April/2021 or October/2021.

2.4. Intervention

The intervention FOREST has been described in detail previously (Jovarauskaite et al., 2021). In brief, it is a six-week online program based on cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), with the inclusion of mindfulness principles. The program used for the current study was developed by clinical psychologists and researchers with expertise in stress-related conditions and internet-delivered interventions; the program FOREST is available for researchers interested upon a reasonable request. The program consists of six modules: Introduction, Psychological detachment, Distancing, Mastery, Control, and Keeping the change alive. Every module consists of psychoeducation on the specific topic, several exercises, and a reminder to message the psychologist who responds to the participant within 24 h. Participants were provided with access to a new program module weekly on the same weekday, and they received an email stating the availability of the new module. Also, additional weekly reminders were sent to the participants who had not signed into the intervention platform, had not read the new material, or had not done the new exercises. Eight psychologists were involved in the study. The psychologists' role included giving feedback to participants after completing the intervention exercises, answering questions, and providing psychological support. Responses by the psychologists were standardized according to the guidelines, and weekly supervision meetings were held.

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Stress recovery

The Recovery Experiences Questionnaire (REQ) (Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007) was used to measure stress recovery. The REQ comprises 16 items measuring four components of stress recovery: (1) psychological detachment (e.g., “I forget about work”), (2) relaxation (e.g., “I kick back and relax”), (3) mastery (e.g., “I learn new things”), and (4) control (e.g., “I feel like I can decide for myself what to do”) with 4 items on each subscale. The participants indicated their level of agreement with the REQ items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “totally disagree” to 5 “totally agree”. Cronbach's alpha was good for the total REQ in the current study at T1 (α = 0.89), indicating sufficient internal consistency. Each subscale also showed good or acceptable internal consistency: psychological detachment (α = 0.83), relaxation (α = 0.85), mastery (α = 0.78), and control (α = 0.82).

2.5.2. Stress

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) (Cohen et al., 1983) was used to measure the perceived level of stress. The PSS-4 comprises 4 items (e.g., “In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?”). The participants indicated their level of agreement with items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “never” to 4 “very often”. Cronbach's alpha was acceptable for the PSS-4 in the current study at T1 (α = 0.73).

2.5.3. Depression and anxiety symptoms

The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) (Kroenke et al., 2009) was used to measure depression and anxiety symptoms. The PHQ-4 comprises 4 items and 2 subscales with two items each: anxiety symptoms (e.g., “Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge”), and depression symptoms (e.g., “Little interest or pleasure in doing things”). The participants indicated their level of agreement with the PHQ-4 items on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “not at all” to 3 “nearly every day”. Cronbach's alpha was good for the PHQ-4 in the current study at T1 (α = 0.88).

2.5.4. Psychological well-being

The World Health Organization Well-being Index (WHO-5) (Bech, 2004) was used to measure psychological well-being. The WHO-5 comprises 5 items (e.g., “I have felt cheerful and in good spirits”). The participants indicated their level of agreement with the WHO-5 items on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “at no time” to 5 “all the time”. Cronbach's alpha was good for the WHO-5 in the current study at T1 (α = 0.89).

2.5.5. Posttraumatic stress symptoms

The International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) (Cloitre et al., 2018) was used to measure symptoms of posttraumatic stress and complex posttraumatic stress. As posttraumatic stress and complex posttraumatic stress are reactions to trauma exposure, the ITQ responses were collected only from participants who reported exposure to at least one lifetime traumatic event as measured with the trauma exposure screening. The ITQ comprises 18 items constituting two parts, that is, a subscale of the core posttraumatic stress symptom cluster (6 symptom items, e.g., “Having upsetting dreams that replay part of the experience or are clearly related to the experience”) and a subscale for complex posttraumatic stress-specific symptoms of disturbances in self-organization (6 symptom items, e.g., “When I am upset, it takes me a long time to calm down”). The additional 6 items measure functional impairment either related to posttraumatic stress symptoms (3 items) or disturbances in self-organization symptoms (3 items). The participants indicated their level of agreement with ITQ items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “not at all” to 4 “extremely”. Cronbach's alpha was good for the ITQ in the current study at T1 (α = 0.86), as well as for subscales of posttraumatic stress (α = 0.86) and disturbances in self-organization (α = 0.83).

2.5.6. Moral injury

The Moral Injury Outcome Scale (MIOS) (Litz et al., 2020) was used to measure moral injury. The MIOS comprises 14 items (e.g., “I have lost faith in humanity”). The participants indicated their level of agreement with the MIOS items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “strongly disagree” to 4 “strongly agree”. Cronbach's alpha was good for the MIOS in the current study at T1 (α = 0.89).

2.5.7. Usability of the FOREST intervention

Participants were asked to evaluate the usability of the FOREST intervention by indicating how useful (from 1 “not useful at all” to 5 “very useful”), satisfactory (from 1 “I did not like it at all” to 5 “I liked it a lot”), and easy to use (from 1 “it was not easy at all” to 5 “it was very easy”) the program had been. Participants were also asked to report their subjective impression regarding the improvement of mental well-being (from 1 “worsened a lot” to 5 “improved a lot”), physical health (from 1 “worsened a lot” to 5 “improved a lot”), general understanding of oneself and one's well-being (from 1 “not at all” to 5 “definitely improved”), and recommending the program to others (from 1 “not at all” to 5 “definitely would recommend”).

2.6. Data analysis

To estimate intervention effects, we used the latent change modeling approach (Duncan et al., 2006). In latent change models, the intercept represents the mean level of the measure at the first measurement point (pre-test), and the slope represents the change from one measurement point to the other. To compare the intervention and control groups in terms of outcome measures at the baseline, we regressed the intervention condition (0 = waiting list control group; 1 = intervention group) on the intercepts of variables of interest. To indicate the intervention effects, we regressed the intervention condition on the slopes of outcome variables. The immediate intervention effects were indicated by the regression coefficients on slopes from pre- to post-tests, and the sustainability of effects over the period of three months was indicated by the regression coefficients on slopes from the pre-test to follow-up. To contrast the changes in the intervention and control groups, we ran the series of multiple-group latent change models, indicating the change of outcome variables from the pre- to post-test and from the pre-test to follow-up in each group separately. We tested the intervention effects on separate stress recovery components of psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, and control using the sum scores for each subscale. We tested the intervention effects on secondary outcomes (perceived stress, anxiety and depression symptoms, and well-being) using the sum scores of the respective measures. Finally, we tested the effects on posttraumatic stress and disturbances in self-organization symptoms in a sample of participants who had experienced at least one traumatic event and moral injury in a sample of participants who had experienced an event or events that may lead to moral injury using the sum scores of respective measures. To have the latent change models identified, in all models, we fixed the residuals to zero.

Further, we calculated between-group and within-group effect sizes, following the correct effect size calculation recommendations for latent change models (Feingold, 2009). The between-group pre- to post-test and pre-test to follow-up effect sizes were calculated using the mean slopes from the pre- to post-test and from the pre-test to follow-up in the intervention group and waiting list control group, respectively, and the standard deviations of the intercept in each group. The within-group pre- to post-test and pre-test to follow-up effect sizes were calculated by using the intercepts in each group indicating the level of the measure at the pre-test, estimated means at the post-test or follow-up, and standard deviations of the intercepts. Bias-corrected effect sizes (Fritz et al., 2012) were reported. In all analyses, the magnitude of the effect expressed in d was interpreted according to Cohen (Cohen, 1988), that is, 0.50 = medium effect, and 0.80 = large effect.

The independent samples t-test and χ2-test were used to test for between-group differences in demographic characteristics using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26. The latent change analyses were performed with Mplus 8.2 (Muthén and Muthén, 2017). No data imputation was applied. The full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimator was used in latent change analyses for handling the missing data (Enders, 2010).

3. Results

3.1. Participants

The participant flowchart is presented in Fig. 1. Overall, 208 individuals registered for the study and completed the pre-test assessment. After the exclusion of 24 individuals (due to not meeting inclusion or meeting exclusion criteria (two were not medical nurses, and one had an alcohol addiction), declining to participate, and other reasons), 184 participants were randomly assigned to the intervention group (n = 93) or waiting list control group (n = 91). Sixteen participants from the intervention group declined to participate after randomization (n = 6) or never signed into the intervention application (n = 10); therefore, were excluded from the analysis.

The final study sample comprised 168 nurses (M age = 42.12, SD age = 11.38; 97 % female): 77 in the intervention group and 91 in the waiting list control group. Descriptive data on study participants at the pre-test are presented in Table 1 . Analysis of the chi-square and t-test showed no statistically significant differences between the intervention and waiting list control groups at the pre-test for any of demographic characteristics. Also, there were no differences between intervention and waiting list control groups at the pre-test in terms of stress recovery components of psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, and control, as well as no differences were found for perceived stress, anxiety and depression symptoms, well-being, posttraumatic stress and disturbances in self-organization symptoms, and moral injury between the two groups (Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants (N = 168) at pre-test.

| Variable | Intervention group (n = 77) n (%) |

Control group (n = 91) n (%) |

Significance statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 75 (97.4) | 88 (96.7) | χ2(1) = 0.07, p = .790 |

| Male | 2 (2.6) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Age | |||

| M (SD) | 40.39 (11.90) | 43.58 (10.77) | t(166) = 1.82, p = .070 |

| Range | 23–61 | 23–65 | |

| Position | |||

| Nurse | 72 (93.5) | 88 (96.7) | χ2(1) = 0.94, p = .332 |

| Assistant nurse | 5 (6.5) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Education | |||

| Secondary or lower | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.1) | χ2(2) = 0.56, p = .756 |

| Higher or non-university higher | 43 (55.8) | 56 (61.5) | |

| Higher university | 33 (42.9) | 34 (37.4) | |

| Working status | |||

| Part-time | 6 (7.8) | 1 (1.1) | χ2(2) = 4.93, p = .085 |

| Full-time | 28 (36.4) | 39 (42.9) | |

| More than full-time | 43 (55.8) | 51 (56.0) | |

| Department | |||

| Surgical | 6 (7.8) | 8 (8.8) | χ2(5) = 3.35, p = .646 |

| Therapy | 32 (41.6) | 38 (41.8) | |

| Anesthesiology and intensive care | 14 (18.2) | 14 (15.4) | |

| Outpatient care | 12 (15.6) | 9 (9.9) | |

| Emergency | 7 (9.1) | 8 (8.8) | |

| Other | 6 (7.8) | 14 (15.4) | |

| Work experience | |||

| < 2 years | 10 (13.0) | 6 (6.6) | χ2(3) = 6.04, p = .109 |

| 2–5 years | 12 (15.6) | 12 (13.2) | |

| 6–10 years | 12 (15.6) | 7 (7.7) | |

| > 10 years | 43 (55.8) | 66 (72.5) | |

| Long-term relationship | |||

| No | 18 (23.4) | 26 (28.6) | χ2(1) = 0.58, p = .445 |

| Yes | 59 (76.6) | 65 (71.4) | |

| Consulting a psychologist | |||

| No | 70 (90.9) | 87 (95.6) | χ2(1) = 1.50, p = .220 |

| Yes | 7 (9.1) | 4 (4.4) | |

| Taking medication due to mental health difficulties | |||

| No | 72 (93.5) | 86 (94.5) | χ2(1) = 0.07, p = .785 |

| Yes | 5 (6.5) | 5 (5.5) | |

| Recently used other self-help app | |||

| No | 65 (84.4) | 79 (86.8) | χ2(1) = 0.20, p = .658 |

| Yes | 12 (15.6) | 12 (13.2) | |

| Worked with COVID-19 patients | |||

| No | 23 (29.9) | 28 (30.8) | χ2(1) = 0.02, p = .900 |

| Yes | 54 (70.1) | 63 (69.2) | |

| Experienced the death of COVID-19 patient(s) | |||

| No | 50 (64.9) | 52 (57.1) | χ2(1) = 1.06, p = .303 |

| Yes | 27 (35.1) | 39 (42.9) | |

| Was diagnosed with COVID-19 | |||

| No | 60 (77.9) | 68 (74.7) | χ2(1) = 0.24, p = .628 |

| Yes | 17 (22.1) | 23 (25.3) | |

| Had someone close to them diagnosed with COVID-19 | |||

| No | 34 (44.2) | 42 (46.2) | χ2(1) = 0.07, p = .795 |

| Yes | 43 (55.8) | 49 (53.8) | |

| Lost a loved one due to COVID-19 | |||

| No | 72 (93.5) | 88 (96.7) | χ2(1) = 0.94, p = .332 |

| Yes | 5 (6.5) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Was vaccinated against COVID-19 | |||

| No | 21 (27.3) | 24 (26.4) | χ2(1) = 0.02, p = .896 |

| Yes | 56 (72.7) | 67 (73.6) |

Table 2.

Baseline comparison and intervention effects as well as mean intercepts and slopes for intervention (n = 77) and the control (n = 91) groups.

| N = 168 | Intercept |

βbaseline | Slope (pre-post) |

βpre-post | Slope (pre-follow-up) |

βpre-follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | Var | M | Var | M | Var | ||||

| Psychological detachment | |||||||||

| Intervention | 10.87 | 12.71 | 0.05 | 2.49⁎⁎⁎ | 17.36 | 0.35⁎⁎⁎ | 2.60⁎⁎⁎ | 13.53 | 0.37⁎⁎⁎ |

| Control | 10.58 | 7.34 | − 0.13 | 9.34 | − 0.23 | 12.06 | |||

| Relaxation | |||||||||

| Intervention | 13.18 | 10.46 | − 0.06 | 2.14⁎⁎⁎ | 11.82 | 0.41⁎⁎⁎ | 1.71⁎⁎⁎ | 14.49 | 0.30⁎⁎⁎ |

| Control | 13.55 | 7.15 | − 0.60⁎ | 7.43 | − 0.27 | 5.90 | |||

| Mastery | |||||||||

| Intervention | 12.96 | 8.87 | − 0.03 | 1.47⁎⁎⁎ | 10.20 | 0.30⁎⁎⁎ | 1.27⁎⁎ | 13.49 | 0.24⁎⁎ |

| Control | 13.17 | 9.52 | − 0.49 | 9.03 | − 0.45 | 11.04 | |||

| Control | |||||||||

| Intervention | 14.46 | 7.76 | 0.02 | 1.19⁎⁎⁎ | 7.16 | 0.26⁎⁎⁎ | 0.89 | 11.62 | 0.14 |

| Control | 14.36 | 9.64 | − 0.17 | 6.19 | 0.10 | 5.30 | |||

| Perceived stress | |||||||||

| Intervention | 7.99 | 6.07 | 0.05 | − 1.61⁎⁎⁎ | 5.29 | − 0.24⁎⁎⁎ | − 2.02⁎⁎⁎ | 8.92 | − 0.33⁎⁎⁎ |

| Control | 7.70 | 8.10 | − 0.29 | 9.29 | 0.10 | 9.71 | |||

| Anxiety symptoms | |||||||||

| Intervention | 2.66 | 2.43 | − 0.10 | − 0.66⁎⁎⁎ | 2.40 | − 0.15⁎ | − 0.44⁎ | 2.20 | − 0.10 |

| Control | 2.99 | 3.22 | − 0.13 | 3.24 | − 0.13 | 2.74 | |||

| Depression symptoms | |||||||||

| Intervention | 2.53 | 1.86 | − 0.03 | − 0.75⁎⁎⁎ | 2.44 | − 0.22⁎⁎ | − 0.53⁎ | 2.75 | − 0.15 |

| Control | 2.64 | 2.85 | 0.01 | 2.98 | − 0.01 | 3.02 | |||

| Well-being | |||||||||

| Intervention | 9.61 | 21.80 | 0.01 | 2.65⁎⁎⁎ | 21.06 | 0.28⁎⁎⁎ | 2.84⁎⁎⁎ | 25.67 | 0.25⁎⁎ |

| Control | 9.51 | 23.50 | 0.09 | 16.98 | 0.50 | 16.71 | |||

| Posttraumatic stress symptoms (N = 121) | |||||||||

| Intervention (n = 51) | 6.86 | 23.88 | − 0.06 | − 0.69 | 24.75 | − 0.20⁎ | 0.02 | 31.47 | − 0.05 |

| Control (n = 70) | 7.57 | 41.79 | 1.19⁎ | 19.27 | 0.74 | 38.75 | |||

| Disturbances in self-organization symptoms (N = 121) | |||||||||

| Intervention (n = 51) | 8.77 | 21.20 | 0.01 | − 1.11 | 22.07 | − 0.16 | − 1.14 | 17.92 | − 0.07 |

| Control (n = 70) | 8.69 | 28.59 | 0.27 | 13.18 | − 0.55 | 19.29 | |||

| Moral injury (N = 96) | |||||||||

| Intervention (n = 49) | 20.76 | 95.53 | − 0.13 | − 1.83 | 52.12 | − 0.03 | − 4.78⁎⁎ | 83.12 | − 0.09 |

| Control (n = 47) | 22.96 | 47.87 | − 1.31 | 59.43 | − 3.26⁎ | 65.54 | |||

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

3.2. Engagement in the intervention and attrition

In the intervention group, participants were considered engaged in the present study if they had signed into the intervention platform at least once. Most of the participants (77/87, 88.5 %) met this criterion. Of those who signed into the intervention platform, 24.7 % (19/77) signed in < 5 times, 37.7 % (29/77) signed in 5–10 times, and 37.7 % (29/77) signed in 11–20 times. Participants signed into the separate modules of the intervention as follows: 98.7 % (76/77) to the first (Introduction), 88.3 % (68/77) to the second (Psychological detachment), 80.5 % (62/77) to the third (Distancing), 67.5 % (52/77) to the fourth (Mastery), 62.3 % (48/77) to the fifth (Control), and 53.2 % (41/77) to the sixth (Keeping the change alive) module. More than half of the participants from the intervention group provided post-test (61/77, 79.2 %) and follow-up (52/77, 67.5 %) assessments. From the waiting list control group, 89.0 % (81/91) of participants provided post-test and 68.1 % (62/91) follow-up assessments. Thus, the attrition rates were 15.5 % (26/168) at the post-test and 32.1 % (54/168) at the follow-up.

3.3. Intervention outcomes

The results of latent change analyses are presented in Table 2. The analyses revealed a statistically significant intervention effect on the increase of stress recovery components of psychological detachment, relaxation, and mastery both from the pre- to post-test and from the pre-test to follow-up; the positive effect on the change of control scores was observed from the pre- to post-test only. During the study period, psychological detachment, relaxation, and mastery increased in the intervention group. Psychological detachment and mastery remained stable in the control group over three months. Relaxation decreased in the control group from the pre- to post-test and returned to the baseline level at the three-month follow-up. The control increased in the intervention group from the pre- to post-test and returned to the baseline level at the three-month follow-up, while in the control group, it remained stable over the study period. Effect sizes are presented in Table 3 . The between-group effect sizes from the pre- to post-test indicated a large intervention effect on the increase of psychological detachment and relaxation scores, a moderate intervention effect on the increase of mastery score, and a small intervention effect on the increase of control score. Also, a large increase in psychological detachment, a moderate increase in relaxation, and mastery scores were observed from the pre-test to follow-up. The within-group effect sizes from the pre- to post-test and from the pre-test to follow-up indicated a moderate increase in psychological detachment and relaxation scores and a small increase in mastery and control scores in the intervention group. No statistically significant within-group changes were observed in the control group.

Table 3.

Intervention effect sizes.

| Variable | Group | Within-group Pre-test and post-test d [95 % CI] |

Within-group Pre-test and follow-up d [95 % CI] |

Between-group Pre-test and post-test d [95 % CI] |

Between-group Pre-test and follow-up d [95 % CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological detachment | Intervention | 0.70 [0.37; 1.02] | 0.73 [0.40; 1.05] | 0.83 [0.52; 1.15] | 0.90 [0.58; 1.22] |

| Control | − 0.05 [− 0.34; 0.24] | − 0.08 [− 0.38; 0.21] | |||

| Relaxation | Intervention | 0.66 [0.33; 0.98] | 0.53 [0.21; 0.85] | 0.93 [0.61; 1.25] | 0.67 [0.36; 0.98] |

| Control | − 0.22 [− 0.52; 0.07] | − 0.10 [− 0.39; 0.19] | |||

| Mastery | Intervention | 0.49 [0.17; 0.81] | 0.42 [0.10; 0.74] | 0.64 [0.33; 0.95] | 0.56 [0.25; 0.87] |

| Control | − 0.16 [− 0.45; 0.13] | − 0.15 [− 0.44; 0.15] | |||

| Control | Intervention | 0.42 [0.10; 0.74] | 0.32 [0.00; 0.64] | 0.46 [0.15; 0.76] | 0.27 [− 0.04; 0.57] |

| Control | − 0.05 [− 0.35; 0.24] | 0.03 [− 0.26; 0.32] | |||

| Perceived stress | Intervention | − 0.65 [− 0.98; − 0.33] | − 0.82 [− 1.15; − 0.49] | − 0.49 [− 0.80; − 0.18] | − 0.79 [− 1.10; − 0.47] |

| Control | − 0.10 [− 0.39; 0.19] | 0.03 [− 0.26; 0.33] | |||

| Anxiety symptoms | Intervention | − 0.42 [− 0.74; − 0.10] | − 0.28 [− 0.60; 0.04] | − 0.31 [− 0.62; − 0.01] | − 0.18 [− 0.49; 0.12] |

| Control | − 0.07 [− 0.36; 0.22] | − 0.07 [− 0.36; 0.22] | |||

| Depression symptoms | Intervention | − 0.55 [− 0.87; − 0.23] | − 0.39 [− 0.71; − 0.07] | − 0.49 [− 0.80; − 0.18] | − 0.33 [− 0.64; − 0.03] |

| Control | 0.01 [− 0.28; 0.30] | − 0.01 [− 0.30; 0.28] | |||

| Well-being | Intervention | 0.56 [0.24; 0.89] | 0.61 [0.28; 0.93] | 0.53 [0.23; 0.84] | 0.49 [0.18; 0.80] |

| Control | 0.02 [− 0.27; 0.31] | 0.10 [− 0.19; 0.39] | |||

| Posttraumatic stress symptoms | Intervention | − 0.14 [− 0.53; 0.25] | 0.00 [− 0.38; 0.39] | − 0.32 [− 0.68; 0.04] | − 0.12 [− 0.48; 0.24] |

| Control | 0.18 [− 0.15; 0.52] | 0.11 [− 0.22; 0.45] | |||

| Disturbances in self-organization symptoms | Intervention | − 0.24 [− 0.63; 0.15] | − 0.25 [− 0.64; 0.14] | − 0.27 [− 0.63; 0.09] | − 0.12 [− 0.48; 0.25] |

| Control | 0.05 [− 0.28; 0.38] | − 0.10 [− 0.43; 0.23] | |||

| Moral injury | Intervention | − 0.19 [− 0.58; 0.21] | − 0.49 [− 0.89; − 0.08] | − 0.06 [− 0.46; 0.34] | − 0.18 [− 0.58; 0.22] |

| Control | − 0.19 [− 0.59; 0.22] | − 0.47 [− 0.88; − 0.06] |

The latent change analyses of the secondary outcomes (perceived stress, anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms, and well-being) indicated statistically significant intervention effects on a decrease in perceived stress and increase in well-being both from the pre- to post-test and from the pre-test to follow-up. The statistically significant intervention effects on decrease in depression and anxiety symptoms were observed from the pre- to post-test only. Perceived stress, depression, and anxiety symptoms decreased, and well-being increased in the intervention group over three months, while all these outcomes remained stable in the control group. Effect sizes are presented in Table 3. The between-group effect sizes from the pre- to post-test indicated a moderate intervention effect on the increase of well-being score and a small intervention effect on the decrease of perceived stress, anxiety symptoms, and depression symptoms scores. Also, a moderate decrease in perceived stress score and a small decrease in depression symptoms score, and a small increase in well-being score were observed from the pre-test to follow-up. The within-group effect sizes from the pre- to post-test indicated a moderate decrease in perceived stress and depression symptoms scores, a moderate increase in well-being scores, and a small decrease in anxiety symptoms scores in the intervention group. Also, a large decrease in perceived stress score, a moderate increase in well-being score, and a small decrease in depression symptoms score were observed from the pre-test to follow-up in the intervention group. No statistically significant within-group changes were observed in the control group.

Finally, the latent change analyses of posttraumatic stress symptoms and disturbances in self-organization symptoms in a sample of participants who had experienced at least one traumatic event and moral injury were performed in a sample of participants who had experienced an event or events that may lead to moral injury. Traumatic experiences were reported by 66.2 % (n = 51) of the intervention group participants and 76.9 % (n = 70) of the participants from the waiting list control group. The analyses revealed a statistically significant intervention effect on posttraumatic stress symptoms from the pre- to post-test, but not from the pre-test to follow-up. No intervention effects on disturbances in self-organization symptoms were observed. In the intervention group, posttraumatic stress symptoms and disturbances in self-organization symptoms remained stable over three months; in the control group, posttraumatic stress symptoms increased from the pre- to post-test and returned to baseline level at the follow-up when disturbances in self-organization symptoms remained stable over time. Neither between- nor within-group effects were found in either of the groups.

Events that may lead to moral injury were reported by 63.6 % (n = 49) of the intervention group participants and 51.6 % (n = 47) of the participants from the waiting list control group. The analysis revealed no statistically significant intervention effects on moral injury scores. Moral injury decreased statistically significantly over three months in the intervention and control groups. No between-group effects were found, but a small decrease in moral injury score was observed from the pre-test to follow-up in the intervention and control groups.

3.4. Usability of the FOREST intervention

After using the program, of those intervention group participants who had provided post-test assessments and signed into the intervention at least once (n = 61), most of them assessed the program FOREST as useful (51/61, 83.6 %), satisfactory (53/61, 86.9 %), and easy to use (56/61, 91.8 %). Also, a great part of the participants reported that the program FOREST improved their mental well-being (45/61, 73.8 %), physical health (28/61, 45.9 %), and a general understanding of themselves and their well-being (37/61, 60.7 %). Finally, most participants (54/61, 88.5 %) indicated that they would recommend the program FOREST to others. We have also explored the links between the level of engagement to the intervention and participants' perception of its usefulness. We found that participants' perception of the intervention as useful was positively related to the times logged in to the intervention (p = .044, rho = 0.259), but not with the number of modules logged in (p = .079, rho = 0.226).

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal findings

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the effects of the internet-based stress recovery intervention on stress recovery, as well as perceived stress, anxiety and depression symptoms, psychological well-being, posttraumatic stress and complex posttraumatic stress symptoms, and moral injury among medical nurses in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. We also aimed to assess the usability of the program among its users. We found promising intervention effects indicating that the stress recovery intervention FOREST fostered stress recovery skills, including psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, and control, and most of the effects remained stable three months after the intervention. In addition, the intervention was effective in reducing its users' stress, depression, and anxiety symptoms as well as increasing psychological well-being with stable decreased stress and depression symptoms as well as improved psychological well-being three months after the intervention. Finally, we found that participants assessed the intervention as very good, and their overall satisfaction with the program was high.

Study findings revealed that using a six-week duration internet-based stress recovery intervention improved healthcare workers' skills of disengaging from work both physically and mentally, taking time for relaxation, getting involved in challenging experiences that distract from work and learning opportunities in other domains, as well as for deciding which activities to pursue during leisure time as well as when and how to do that. All the skills gained remained stable several months later, except for the control skill. It may be that control skill is the most difficult to acquire compared to psychological detachment, relaxation, and mastery skills. Also, all the information and exercises regarding control were presented in the intervention's last and single module. In contrast, other components were introduced earlier in time and were reminded in further modules. Therefore, the acquisition of the control skill could be related to its insufficient representation, especially having in mind that the last modules were used less by its users than the first modules. Nevertheless, most of the stress recovery skills acquired while using the intervention were stable over the three months, and this looks promising, taking into consideration the heavy workloads and stressful experiences of medical staff.

It is important to note that healthcare workers who were using this CBT-based internet-delivered intervention not only gained stress recovery skills that remained active after three months, but their perceived stress levels were also reduced and remained reduced over three months. It would be interesting to explore whether stress recovery works as a mediator in reducing stress levels; possibly, the intervention could have indirect effects on reducing stress levels through the increase of recovery skills. It is also important that anxiety and depression symptoms were reduced while using the intervention. However, only depression symptoms remained reduced over three months, while anxiety symptoms returned to the baseline level. It may be that more specific intervention may be needed to address anxiety symptoms. One of the most relevant findings of the current study is that the intervention helped reduce various symptoms and improved its participants' quality of life. After using the program, they felt more rested, calm, cheerful, active, and more interested in their daily lives.

Another interesting aspect that should be considered is the benefits of the intervention despite the decreasing engagement with every module. We believe that the intervention started providing benefits from its very beginning. We hypothesize that people, in this case, medical nurses, benefited from the intervention from its first module, meaning that simply identifying all the stressors experienced, naming the most important ones, and trying to understand their possible impact on a person's daily life can be of extreme importance in order to improve mental health. It is possible that the more the intervention is used, the more effective it is, but the very first effect starts with the first engagement. The possibility of addressing experiences, difficulties, and challenges might help to understand the links between these experiences and daily lives.

To the best of our knowledge, it was among the first studies that explored the efficacy of internet-based stress recovery interventions for healthcare workers. However, there are several studies that our results could indirectly be compared. Other studies that assessed the effectiveness of online programs in the healthcare professionals sample showed similar results to ours. Internet-based interventions were effective in improving well-being (Smoktunowicz et al., 2021), reducing stress levels (Gollwitzer et al., 2018), and equipped with stress management skills (Morrison Wylde et al., 2017). The results suggest that online programs have the potential to help healthcare workers to improve their well-being.

4.2. Limitations

Several limitations should be addressed regarding the current study. First, the study was conducted with a waiting list as a control condition. The results could be replicated with an active control condition in future trials, which would allow testing whether the stress recovery intervention has unique benefits compared to other interventions. Second, the intervention comprised multiple components (psychoeducation via texts and videos, various exercises, and communication with a psychologist). Due to the study design, it is impossible to identify which components contributed to the intervention effects the most. Therefore, future research should address these questions. Third, the study focused on medical nurses, and it remains unclear whether these findings can be generalized to other healthcare workers or other professions in general. Also, regarding the generalizability of results, all study participants were self-referred, which may present the risk of volunteer bias. Finally, the current study explored the effects of the intervention right after the intervention and after three months; such a follow-up period is still too short to assess the stability of the intervention effects in the long term, and future studies should address this issue.

5. Conclusion

The current study demonstrates that the internet-based stress recovery intervention for healthcare staff can effectively increase stress recovery skills, such as psychological detachment, relaxation, and mastery, and have a positive effect on reducing stress and depression symptoms and increasing psychological well-being. In addition, the intervention has the potential to increase stress recovery skill control and reduce anxiety symptoms. Moreover, participants assessed the intervention as very good, and their satisfaction with the program was high. Since healthcare workers face various emotional challenges and seldom seek professional psychological support, internet-based stress recovery interventions could be a feasible option for increasing the well-being of medical nurses.

Funding

The project has received funding from European Regional Development Fund (project no [01.2.2-LMT-K-718-03-0072]) under a grant agreement with the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Austeja Dumarkaite: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Inga Truskauskaite: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Gerhard Andersson: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Lina Jovarauskaite: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Ieva Jovaisiene: Writing – review & editing. Auguste Nomeikaite: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Evaldas Kazlauskas: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.

References

- Bech P. Measuring the dimensions of psychological general well-being by the WHO-5. QoL Newsl. 2004;32:15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Benfante A., Di Tella M., Romeo A., Castelli L. Traumatic stress in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: a review of the immediate impact. Front. Psychol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.569935. (October) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow K.M., Law B.M.H., Ng M.S.N., et al. A review of psychological issues among patients and healthcare staff during two major coronavirus disease outbreaks in China: contributory factors and management strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(18):1–17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M., Shevlin M., Brewin C.R., et al. The international trauma questionnaire: development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018;138(6):536–546. doi: 10.1111/acps.12956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Accociates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavoral Sciences. ISBN 0-8058-0283-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Kamarck T., Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress authors. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan T.E., Duncan S.C., Strycker L.A. 2nd ed. Routledge; New York: 2006. An Introduction to Latent Variable Growth Curve mModeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. ISBN 9780805855470. [Google Scholar]

- Enders C.K. Guilford Press; New York: 2010. Applied Missing Data Analysis. ISBN 9781606236390. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. Trials in the same metric as for classical analysis. Psychol. Methods. 2009;14(1):43–53. doi: 10.1037/a0014699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz C.O., Morris P.E., Richler J.J. Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012;141(1):2–18. doi: 10.1037/a0024338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer P.M., Mayer D., Frick C., Oettingen G. Promoting the self-regulation of stress in health care providers: an internet-based intervention. Front. Psychol. 2018;9(June):1–11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrer M., Adam S.H., Fleischmann R.J., et al. Effectiveness of an internet- and app-based intervention for college students with elevated stress: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018;20(4):1–16. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heber E., Lehr D., Ebert D.D., Berking M., Riper H. Web-based and mobile stress management intervention for employees: a randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016;18(1):1–15. doi: 10.2196/JMIR.5112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovarauskaite L., Dumarkaite A., Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene I., Jovaisiene I., Andersson G., Kazlauskas E. Internet-based stress recovery intervention FOREST for healthcare staff amid COVID-19 pandemic: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05512-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaak S., Mantler E., Szeto A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthc. Manage. Forum. 2017;30(2):111–116. doi: 10.1177/0840470416679413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W., Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ–4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–621. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3182(09)70864-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz B.T., Phelps A., Frankfurt S., Murphy D., Nazarov A., Houle S., Levi-Belz Y., Zerach G., Dell L., Hosseiny F., the members of the M. I. O. S. (MIOS) MIOS Consortium Activities. 2020. The Moral Injury Outcome Scale. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta S.S., Edwards M.L. Suffering in silence: mental health stigma and physicians’ licensing fears. Am. J. Psychiatry Resid. J. 2018;13(11):2–4. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2018.131101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meijman T.F., Mulder G. In: Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology. 1st ed. Drenth P.J.D., Thierry H., Wolff C.J., editors. Psychology Press; London: 1998. Psychological aspects of workload. ISBN 9780203765425. [Google Scholar]

- Mira J.J., Carrillo I., Guilabert M., et al. Acute stress of the healthcare workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic evolution: a cross-sectional study in Spain. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison Wylde C., Mahrer N.E., Meyer R.M.L., Gold J.I. Mindfulness for novice pediatric nurses: smartphone application versus traditional intervention. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017;36:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L.K., Muthén B.O. 8th ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2017. Mplus User’s Guide. ISBN 978-0982998328. [Google Scholar]

- Norkiene I., Jovarauskaite L., Kvedaraite M., et al. ‘Should I stay, or should I go?’ Psychological distress predicts career change ideation among intensive care staff in Lithuania and the UK amid COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18(5):1–9. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki N., Imamura K., Thu Tran T.T., et al. Effects of smartphone-based stress management on improving work engagement among nurses in Vietnam: secondary analysis of a three-arm randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021;23(2):1–12. doi: 10.2196/20445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz K.F., Altman D.G., Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int. J. Surg. 2011;9(8):672–677. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoktunowicz E., Lesnierowska M., Carlbring P., Andersson G., Cieslak R. Resource-based internet intervention (med-stress) to improve well-being among medical professionals: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021;23(1):1–18. doi: 10.2196/21445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag S., Fritz C. The recovery experience questionnaire: development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007;12(3):204–221. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søvold L.E., Naslund J.A., Kousoulis A.A., et al. Prioritizing the mental health and well-being of healthcare workers: an urgent global public health priority. Front. Public Health. 2021;9(May):1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.679397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaescu G., Alasjö A., Miloff A., Carlbring P., Andersson G. Features and functionality of the Iterapi platform for internet-based psychological treatment. Internet Interv. 2016;6:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.