Abstract

Introduction

Our study aims to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of uro-oncological surgeries (cystectomy, nephrectomy, prostatectomy, orchiectomy, and transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT)) and pathological staging and grading.

Materials and Methods

The present study is a retrospective study on patients with genitourinary cancers treated from 2018 to 2021 in a referral tertiary center. The data were obtained from the hospital records with lengths of 22 and 23 months, labeled hereafter as non-COVID and COVID pandemic, respectively (2018/3/21-2020/1/20 and 2020/1/21-2021/12/21). The total number of registered patients, gender, age, stage, and grade were compared in the targeted periods. Moreover, all the pathologic slides were reviewed by an expert uropathologist before enrolling in the study. The continuous and discrete variables are reported as mean (standard deviation (SD)) and number (percent) and the χ2 test for the comparison of the discrete variables' distribution.

Results

In this study total number of 2077 patients were enrolled. The number of procedures performed decreased during the Covid pandemic. The tumors' distribution stage and grade and patients' baseline characteristics were not significantly different in non-COVID and COVID pandemic periods for Radical Nephrectomy, Radical Cystectomy, Radical Prostatectomy, and orchiectomy. For TURBT only, the tumor stage was significantly different (P-value<.001) from the higher stages in the COVID pandemic period.

Conclusion

Among urinary tract cancers, staging of bladder cancer and TURBT are mainly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic with higher stages compared to the non-COVID period.

We evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of uro-oncological surgeries based on pathological staging and grading. Total number of 2077 patients were enrolled. Among urinary tract cancers, staging of bladder cancer and TURBT are mainly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic with higher stages compared to the non-COVID period.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Cystectomy, Nephrectomy, Orchiectomy, Prostatectomy, TURBT

Micro-Abstract

Our study aims to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of uro-oncological surgeries. Our study aims to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of uro-oncological surgeries.

Introduction

Since COVID-19′s discovery in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, more than 468 million people have been infected, and more than 6 million have died worldwide.1 The Covid-19 outbreak has been a significant setback for health care systems, particularly for vulnerable populations such as cancer patients. The influx of large numbers of COVID-19 patients requiring intensive monitoring and mechanical ventilation has caused health care systems to become overburdened. Therefore, oncology patients' outcomes are likely to be harmed by standard delayed treatment.2, 3, 4 Previous research has linked the COVID-19 pandemic to lower diagnosis rates for malignancies, including breast, colorectal, lung, pancreatic, gastric, and esophageal cancers.5 , 6

Timely diagnosis of cancer is essential to optimize the clinical outcomes of patients and has been considered to improve in recent decades.7 , 8 Like many other oncologists, urologists are fighting the pandemic on 2 fronts: the pandemic itself and cancers. It confronts Urologists because therapeutic delays may lead to adverse oncological outcomes and patients with higher cancer stages. Urologic cancers such as the bladder and prostate are among the most prevalent cancers worldwide, and delays in recognizing them can be life-threatening. Patients in their late 60s and early 70s have a higher risk of urologic cancers; these groups are more prone to COVID-19 and have several comorbidities. Approximately 80% of COVID-19 deaths in China occurred in adults over 60.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Several recommendations and guidelines have been published to improve the triage and treatment of uro-oncological patients in times of limited resources. These guidelines are beneficial in dealing with the current pandemic situation. Still, due to differences in health care systems, demographic features, genetics, stage, grade, and fear of pandemic in any country, we encourage optimization of these guidelines by each country's characteristics.14, 15, 16

We aimed to check whether the COVID-19 pandemic can change the number of uro-oncological surgeries (radical cystectomy, radical nephrectomy, radical prostatectomy, radical orchiectomy, and transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT)) and the tumor staging and grading during non-pandemic and pandemic period in Iran's referral tertiary center.

Material and Methods

Study Design and Sampling

A retrospective study on patients confirmed by post-operative or biopsy pathology reports with urology cancer treated from 2018 to 2021, at Sina Hospital affiliated to Tehran University of Medical Sciences, and MohebMehr Hospital affiliated to Iran University of Medical Sciences designed to compare patients' gender and age and tumors stage and grade over two time periods: 1. non-covid pandemic (2018/3/21-2020/1/20), 2. covid pandemic (2020/1/21-2021/12/21), with lengths of 22 and 23 months, labeled hereafter as non-COVID and COVID pandemic, respectively. The Scientific and Ethics Committee approved this study at the Tehran University of Medical Science (IR.TUMS.SINAHOSPITAL.REC.1400.037).

Tumors were classified according to the prognostic AJCC tumor, lymph node, metastasis (TNM)-based staging system,17 ISUP 2016 grading for bladder and prostate,18 and Fuhrman Nuclear Grade for renal carcinoma based on cellular appearance.19

In the Fuhrman Nuclear grading system, chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (ChRCC) is not classified, so we excluded 6 cases of ChRCC in non-COVID and 6 cases of ChRCC in the COVID pandemic from the study. In addition, we excluded urothelial carcinoma of the renal pelvis (14 cases of TCC in non-COVID and 8 cases of TCC during the COVID pandemic).

The known cancer cases with recurrence malignancy or post-chemotherapy biopsy were excluded from the study, and all the pathological slides were reviewed by an expert uropathologist before enrolling in the study.

Statistical Analysis

The continuous and discrete variables are reported as mean (standard deviation (SD)) and number (percent), respectively. The χ2 test compared the discrete variables' distribution between the time intervals.

Results

In this study total number of 2077 patients were enrolled. The tumors' distribution and patients' age and sex characteristics are reported in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Tumors' Distribution was compared for the Two Target Time Intervals

| Tumor | non-COVID | COVID Pandemic | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number total/monthly | 43 / 2.0 | 18 / 0.8 | ||

| Cystectomy | Age, mean (SD) | 62.3 (9.1) | 63.6 (6.1) | .585 |

| Sex (male), num. (%) | 40 (93.0 %) | 17 (94.4 %) | .838 | |

| Number total/monthly | 199 / 9.0 | 145 / 6.6 | ||

| Nephrectomy | Age, mean (SD) | 58.9 (12.9) | 59.7 (11.8) | .540 |

| Sex (male), num. (%) | 124 (62.3 %) | 91 (62.8 %) | .933 | |

| Prostatectomy | Number total/monthly | 284 / 12.9 | 188 / 8.5 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 64.4 (6.6) | 64.2 (6.6) | .712 | |

| Orchiectomy | Number total/monthly | 18 / 0.8 | 12 / 0.5 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 40.3 (14.8) | 38.3 (14.8) | .716 | |

| Number total/monthly | 652 / 29.6 | 518 / 23.5 | ||

| TURBT | Age, mean (SD) | 67.2 (11.4) | 65.9 (12.4) | .061 |

| Sex (male), num. (%) | 533 (81.8 %) | 423 (81.7 %) | .969 |

SD = standard deviation.

The total number of kidney cancers was 219 non-COVID and 159 COVID pandemics and finally, 199 non-COVID nephrectomy cases and 145 COVID pandemic cases of nephrectomy remain for additional analysis. The number of tumor related sutgical procedures decreased during the Covid pandemic. The age and sex distributions showed no significant difference. The monthly frequencies of all tumors are also presented in Figure 1 . While an almost seasonal pattern is apparent in the case of men, with the peaks in the spring, the women are almost uniformly distributed.

Figure 1.

The monthly frequencies of tumors

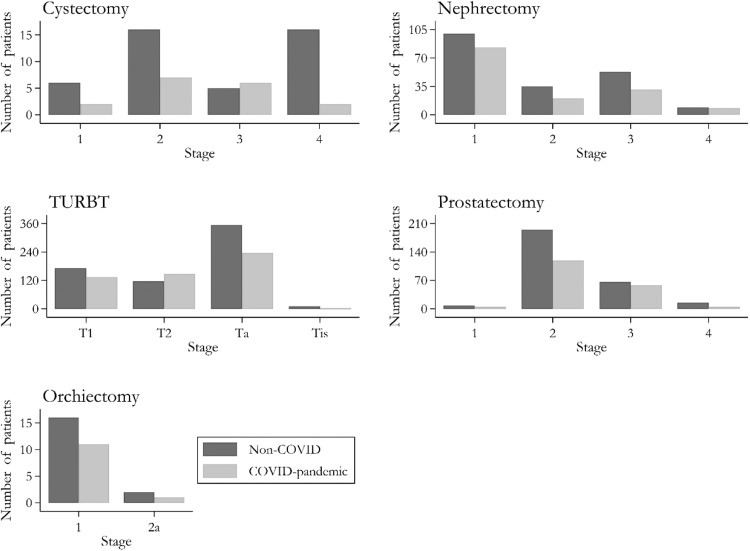

Figure 2 presents the tumors' staging in the 2 target periods as percentages of each period. The only significant difference between the non-COVID and COVID pandemic periods was observed for TURBT (P-value<.001), obtained through the χ2 test.

Figure 2.

The distribution of tumors' staging, compared for the non-COVID and COVID pandemic periods (numbers over the bars are percentages) Similarly, in Figure 3, tumor grading is reported as percentages comparing the periods. The cystectomy tumors were all high grades, and no grading was documented for the orchiectomy tumors. There was no significant difference between the 2 periods for nephrectomy, prostatectomy, and TURBT tumors

Additionally, enough observations were collected to compare men's and women's stages and grades of nephrectomy and TURBT tumors. Table 2 presents these findings.

Table 2.

Nephrectomy and TURBT Tumors' Staging and Grading, Compared between Men and Women

| Tumor | non-COVID |

P-Value | COVID-pandemic |

P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | ||||

| Nephrectomy | Stage | ||||||

| 1 | 39 (52.0 %) | 61 (50.0 %) | 0.373 | 33 (61.1 %) | 50 (56.8 %) | .972 | |

| 2 | 9 (12.0 %) | 26 (21.3 %) | 7 (12.9 %) | 13 (14.8 %) | |||

| 3 | 23 (30.7 %) | 30 (24.6 %) | 11 (20.4 %) | 20 (22.7 %) | |||

| 4 | 4 (5.3 %) | 5 (4.1 %) | 3 (5.6 %) | 5 (5.7 %) | |||

| Grade | |||||||

| 1 | 3 (4.0 %) | 9 (7.3 %) | 0.442 | 7 (13.0 %) | 6 (6.6 %) | .086 | |

| 2 | 27 (36.0 %) | 33 (26.8 %) | 20 (37.0 %) | 34 (37.4 %) | |||

| 3 | 37 (49.3 %) | 70 (56.9 %) | 19 (35.2 %) | 46 (50.5 %) | |||

| 4 | 8 (10.7 %) | 11 (8.9 %) | 8 (14.8 %) | 5 (5.5 %) | |||

| TURBT | Stage | ||||||

| T1 | 22 (18.5 %) | 150 (28.1 %) | 0.061 | 17 (17.9 %) | 117 (27.7 %) | .004 | |

| T2 | 18 (15.1 %) | 98 (18.4 %) | 21 (22.1 %) | 126 (29.8 %) | |||

| Ta | 77 (64.7 %) | 277 (52.0 %) | 56 (58.9 %) | 180 (42.5 %) | |||

| Tis | 2 (1.7 %) | 8 (1.5 %) | 1 (1.1 %) | 0 (0 %) | |||

| Grade | |||||||

| Low | 66 (55.5 %) | 216 (40.5 %) | 0.003 | 51 (53.7 %) | 159 (37.6 %) | .004 | |

| High | 53 (44.5 %) | 317 (59.5 %) | 44 (46.3 %) | 264 (62.4 %) | |||

Values inside the table are numbers (percent). P-values were obtained from the χ2 test.

While no sex difference was observed in the nephrectomy's staging and grading, before and during the pandemic, men and women were significantly different in TURBT. Finally, the Gleason scores for prostatectomy are reported in Table 3 , comparing the periods. No significant differences were observed in the Gleason scores corresponding to the two target time intervals.

Table 3.

The Gleason Scores for Prostatectomy Reported as Number (%), Compared to the Time Intervals

| Score | non-COVID | COVID Pandemic | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3+3 | 15 (5.3 %) | 5 (2.7 %) | .835 |

| 3+4 | 116 (40.8 %) | 80 (42.6 %) | |

| 3+5 | 3 (1.1 %) | 2 (1.1 %) | |

| 4+3 | 105 (37.0 %) | 73 (38.7 %) | |

| 4+4 | 10 (3.5 %) | 9 (4.8 %) | |

| 4+5 | 26 (9.2 %) | 16 (8.5 %) | |

| 5+4 | 8 (2.8 %) | 3 (1.6 %) | |

| 5+5 | 1 (0.4 %) | 0 (0.0 %) |

P-value from the χ2 test

Discussion

We investigate whether the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the stage and grade of genitourinary malignancies at diagnosis in Iran. Several reports are on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the numbers of patients for almost all cancer types.20 , 21 Worries about contracting COVID-19 and fear of higher incidence risk in healthcare systems have prevented patients from referring to their doctors.22 Our findings showed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of nephrectomies, prostatectomies, and the total number of urology procedures decreased but not significantly. Same as the report by Van Deukeren D. and colleagues that showed an initial decrease of 17% in prostate cancer in the first COVID-19 wave but restored the number by the end of 2020.23 Contrary to some data on reducing all urologic activities.24

Other studies in the urologic oncology field have already described a decrease in elective oncological surgical activity; however, this finding has been associated with an increase in the average waiting time for surgery.25, 26, 27, 28 This decrease is related to the health care system's overburdening, pandemic fears, public reluctance, social isolation, and quarantine not change in guidelines and recommendations for urology standard of care during the COVID-19 pandemic.29 New cancer diagnoses dropped during the COVID-19 pandemic because patients with symptoms (eg hematuria or stomach ache) may avoid seeking medical attention due to concern about contracting COVID-19.30 , 31 Semi-structured interviews in the United States found that patients may be reluctant to receive primary care from a physician because they consider hospitals where contagious diseases can spread.32 Moreover, health care systems were quickly overburdened, and non-urgent care services in hospitals and primary care settings were delayed or discontinued.33 A recent survey by Dotzauer et al. showed that 93% of urologists from 44 countries appealed that COVID-19 had decreased their patient number; less TURBT (27%), radical cystectomy (21%-24%), nephroureterectomy (21%) and radical nephrectomy (18%).34

Except for TURBT, which had a significant decline in the Ta, Tis stages and an increase in T2 during the COVID pandemic, no considerable tumor stage change was observed in our study. Ferro M. et al. explained that the COVID-19 pandemic represented an unprecedented challenge to their health system. They did not display noteworthy differences in TURBT quality, but a delay in treatment schedule and disease management was observed.35

It was shown that 2 to 5 months of delay in follow-up cystoscopy as suggested in the COVID-19 pandemic raises the risk of recurrence.36 A study by Tulchiner G. and colleagues indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic gap can increase rates of advanced and aggressive tumors in patients with primary bladder cancer, and additional awareness is required to avoid adverse consequences.37 A recent meta-analysis by Kang DH et al. highlighted the EAU guidelines Rapid Reaction Group in which patients with T2N0M0 muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) should strongly consider omitting neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) until the end of the COVID-19 pandemic.38 However, NAC in T3-4aN0M0 MIBC should be considered.38 According to a review published in the Journal of Urology, this delay should be less than 10 weeks, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy should be considered.39

A systematic review also stated that except for MIBC, high-grade and upper tract urothelial carcinoma, large renal masses, and testicular and penile cancer, most urologic oncologic surgeries could be safely postponed without affecting long-term cancer-specific or overall survival.40 despite the report of no decrease in uro-oncological surgical procedures in an Italic tertiary referral center, an increase was reported in lymph node metastasis, and non-organ confined disease in MIBC T2-T441

We have many patients in the TURBT groups in our study, which allows us to go deep into the data to investigate if gender differences influence the stage and grade of tumors. The TURBT surgery process in Men has shown the higher stage and grade than women during the pandemic. No other study compares gender differences in pathological staging and grading of TURBT tumors before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. This disparity could be attributed to male patients' lack of attention or fear of a pandemic in seeking medical treatment. We propose that future research might employ questionnaires to assess the gap between clinical presentation and seeking medical care and the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) to determine this gender difference in bladder cancer patients.42

Several novel biomarkers and treatment strategies are considered in genitourinary cancers, dependent on timely tumor diagnosis.7 , 43, 44, 45, 46 A significant reduction in radical prostatectomy during the COVID-19 pandemic was reported in our study. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the stage, grade, and Gleason prostate cancer scores have no significant difference in non-COVID and COVID pandemics. Findings from a contemporary prostate cancer cohort by Diamand R., et al. indicate no evidence that a delay in radical prostatectomy is associated with a decrease in oncologic outcomes.47 Similarly, in a systematic review published on intermediate-risk and high-risk prostate cancer, time to surgery can be delayed up to 3 months without adverse effects on their health, and delays of more than 6 to 9 months have been linked to worse pathological results. There have been no reports of worse cancer-specific survival or overall survival due to delaying therapy for intermediate and high-risk prostate cancer.48 Also, in a recent article, Ginsburg et al. state that in radical prostatectomy, early oncological outcomes such as upgrading on radical prostatectomy, lymph node involvement, and secondary treatments after surgery were not related to delays up to 12 months.49 According to the findings, our study did not precisely determine how long each participant had a prostatectomy delay; it can be estimated that this time was probably less than 12 months. In comparison to our study, only one cross-sectional study in Sweden found no decline in the number of radical prostatectomies during the peak of the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.50 Based on most studies' results, we can highlight prostate cancer's slow progression and the necessity for an effective telemedicine system to assist in diagnosing, triaging, and treating patients and minimize the risk of COVID-19 exposure Figure 3 .

Figure 3.

The distribution of tumors' grading, compared for the non-COVID and COVID pandemic periods (numbers over the bars are percentages)

Based on the findings, and given that the COVID-19 pandemic is still active in Iran and many countries, strategies should be done to improve cancer detection with limited healthcare resources. Patients should be better educated about symptoms that necessitate immediate medical attention as a first step. Second, patients should have access to more teleconsultations with their primary care physicians and be referred to specialists as soon as further investigation is required. Third, COVID-19 patients should be assigned to specific hospitals, while other clients should access various facilities. Patients' worry about contracting the sickness will be decreased by attending the hospital in this manner. Certain limitations apply to this investigation. The number of patients in the cystectomy and orchiectomy categories is minimal. We conduct multicenter research, but we do not have a separate report from each center.

Conclusion

The numbers and rates of uro-oncological surgical procedure decreased during the Covid19 period. This phenomenon affected only pathologic tumor stage at trans-urethral resection of the bladder, where a clinically meaningful and statistically significant higher rates of T2/muscle-invasive bladder cancer were diagnosed during the Covid 19 outbreak than during the previous time-period.

Clinical Practice Point

Our study aims to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of uro-oncological surgeries (cystectomy, nephrectomy, prostatectomy, orchiectomy, and transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT)) and pathological staging and grading. The total number of registered patients, gender, age, stage, and grade were compared in the targeted periods. Moreover, all the pathologic slides were reviewed by an expert uropathologist before enrolling in the study. The continuous and discrete variables are reported as mean (standard deviation (SD)) and number (percent) and the χ2 test for the comparison of the discrete variables' distribution. Total number of 2077 patients were enrolled. All tumors tend to decrease in the COVID pandemic period. The tumors' distribution stage and grade and patients' baseline characteristics were not significantly different in non-COVID and COVID pandemic periods for Radical Nephrectomy, Radical Cystectomy, Radical Prostatectomy, and orchiectomy. For TURBT only, the tumor stage was significantly different (P-value<.001) from the higher stages in the COVID pandemic period. Among urinary tract cancers, staging of bladder cancer and TURBT are mainly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic with higher stages compared to the non-COVID period.

Availability of Data and Material

All information, data, and photos are all provided through the manuscript, and additional will be provided if requested.

Ethical Considerations

All patients signed the written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences ethical committee (IR.TUMS.SINAHOSPITAL.REC.1400.037).

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Sina hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Disclosure

All authors claim that there is not any potential competing or conflict of interest.

There is no funding.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Diana Taheri: Writing – review & editing. Fatemeh Jahanshahi: Writing – review & editing. Alireza Khajavi: Data curation, Writing – original draft. Fatemeh Kafi: . Alireza Pouramini: Visualization, Investigation. Reza M. Farsani: Visualization, Investigation. Yasamin Alizadeh: Supervision. Maryam Akbarzadeh: Supervision. Leonardo O. Reis: Software, Validation. Fatemeh Khatami: Visualization, Investigation, Software, Validation. Seyed Mohammad Kazem Aghamir: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software.

References

- 1.COVID Live - Coronavirus Statistics - Worldometer, 2022. Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

- 2.Saini KS, de Las Heras B, de Castro J, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer treatment and research. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(6):e432–e4e5. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30123-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aghamir ZS, Shivarani S, Manafi Shabestari R. The molecular structure and case fatality rate of COVID-19. Translational Res Uro. 2020;2(3):96–106. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mirzaei A, Taheri D, Oliveira Reis L. Vaccine production by recognizing the functional mechanisms of COVID-19. Translational Res Uro. 2020;2(2):59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Niles J, Fesko Y. Changes in the number of US patients with newly identified cancer before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17267. -e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohammadi A, Dialameh H, Hamidi M, et al. Effect of Covid-2019 infection on main sexual function domains in iranian patients. Translational Res Uro. 2022;4(1):41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirzaei A, Zareian Baghdadabad L, Khorrami MH, Aghamir SMK. Arsenic Trioxide (ATO), a novel therapeutic agent for prostate and bladder cancers. Translational Res Uro. 2019;1(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khatami F, Aghamir SMK, Tavangar SM. Oncometabolites: A new insight for oncology. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Med. 2019;7(9) doi: 10.1002/mgg3.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahase E. Sasson I. Age and COVID-19 mortality. Demographic Res. 2021;44:379–396. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Travassos TC, De Oliveira JMI, Selegatto IB, Reis LO. COVID-19 impact on bladder cancer-orientations for diagnosing, decision making, and treatment. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2021;9(1):132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fakhr Yasseri A, Taheri D. Urinary Stone Management During COVID-19 Pandemic. Translational Res Uro. 2020;2(1):1–3. doi: 10.1177/1756287220939513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khatami F, Saatchi M, Zadeh SST, et al. A meta-analysis of accuracy and sensitivity of chest CT and RT-PCR in COVID-19 diagnosis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80061-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohammadi A, Khatami F, Azimbeik Z, Khajavi A, Aloosh M, Aghamir SMK. Hospital-acquired infections in a tertiary hospital in Iran before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2022:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10354-022-00918-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heldwein FL, Loeb S, Wroclawski ML, et al. A systematic review on guidelines and recommendations for urology standard of care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol Focus. 2020;6(5):1070–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mian BM, Siddiqui S, Ahmad AE. Management of urologic cancers during the pandemic and potential impact oftreatment deferrals on outcomes. In Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2021 May 1 (Vol. 39, No. 5, pp. 258–267). Elsevier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Ribal MJ, Cornford P, Briganti A, et al. European association of urology guidelines office rapid reaction group: an organisation-wide collaborative effort to adapt the european association of urology guidelines recommendations to the coronavirus disease 2019 era. Eur Urol. 2020;78(1):21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.AminMB G, Edge S. The eighth edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):93–99. doi: 10.3322/caac.21388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aghamir ZS, Shivarani S, Manafi ShabestariSrigley R. The Molecular Structure and Case Fatality Rate of COVID-19. Transl Res Urology. 2020;2(3):96–106. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuhrman SA, Lasky LC, Limas C. Prognostic significance of morphologic parameters in renal cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6(7):655–663. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutter MD, Brookes M, Lee TJ, Rogers P, Sharp LJG. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on UK endoscopic activity and cancer detection: a National Endoscopy Database Analysis. Gut. 2021;70(3):537–543. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacob L, Loosen SH, Kalder M, Luedde T, Roderburg C, Kostev KJC. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer diagnoses in general and specialized practices in Germany. Cancers. 2021;13(3):408. doi: 10.3390/cancers13030408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Covid C, Team R, COVID C, et al. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Deukeren D, Heesterman BL, Roelofs L, et al . Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on prostate cancer care in the Netherlands. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2022;31 doi: 10.1016/j.ctarc.2022.100553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dell'Oglio P, Cacciamani GE, Muttin F, et al. Applicability of COVID-19 Pandemic Recommendations for Urology Practice: Data from Three Major Italian Hot Spots (BreBeMi) Eur Urol Open Sci. 2021;26:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.euros.2021.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Vahid S, Eberg M, et al. Clearing the surgical backlog caused by COVID-19 in Ontario: a time series modelling study. CMAJ. 2020;192(44):E1347–E1E56. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.201521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uimonen M, Kuitunen I, Paloneva J, Launonen AP, Ponkilainen V, Mattila VMJPO. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on waiting times for elective surgery patients: A multicenter study. PLoS One. 2021;16(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uimonen M, Kuitunen I, Seikkula H, Mattila VM, Ponkilainen V. Healthcare lockdown resulted in a treatment backlog in elective urological surgery during COVID-19. BJU Int. 2021;128(1):33. doi: 10.1111/bju.15433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guerrieri R, Rovati L, Dell'Oglio P, Galfano A, Ragazzoni L, P Aseni. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on urologic oncology surgery: implications for moving forward. J Clin Med. 2021;11(1):171. doi: 10.3390/jcm11010171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heldwein FL, Loeb S, Wroclawski ML, Sridhar AN, Carneiro A, Lima FS, et al. A systematic review on guidelines and recommendations for urology standard of care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol Focus. 2020;6(5):1070–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKay D, Yang H, Elhai J, Asmundson GJ. Anxiety regarding contracting COVID-19 related to interoceptive anxiety sensations: The moderating role of disgust propensity and sensitivity. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;73 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X, Zhuang J, Yu H, et al. Effect of coronavirus disease 2019 on patients with bladder cancer in China. Urol Int. 2021;105(7-8):726–728. doi: 10.1159/000512895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong LE, Hawkins JE, Langness S, Murrell KL, Iris P, Sammann A. Where are all the patients? Addressing Covid-19 fear to encourage sick patients to seek emergency care. NEJM Catalyst. 2020;1(3):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verhoeven V, Tsakitzidis G, Philips H, Van Royen P. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the core functions of primary care: will the cure be worse than the disease? A qualitative interview study in Flemish GPs. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dotzauer R, Böhm K, Brandt MP, et al. Global change of surgical and oncological clinical practice in urology during early COVID-19 pandemic. World J Urol. 2021;39(9):3139–3145. doi: 10.1007/s00345-020-03333-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferro M, Del Giudice F, Carrieri G, et al. The impact of sars-cov-2 pandemic on time to primary, secondary resection and adjuvant intravesical therapy in patients with high-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: A retrospective multi-institutional cohort analysis. Cancer. 2021;13(21):5276. doi: 10.3390/cancers13215276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Culpan M, Keser F, Acar HC, et al. Impact of delay in cystoscopic surveillance on recurrence and progression rates in patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(9):e14490. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tulchiner G, Staudacher N, Fritz J, et al. The “COVID-19 Pandemic Gap” and its influence on oncologic outcomes of bladder cancer. Cancers. 2021;13(8):1754. doi: 10.3390/cancers13081754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang DH, Cho KS, Moon YJ, Chung DY, Jung HD, JYJPo Lee. Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on overall survival of patients with T2-4aN0M0 bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis according to EAU COVID-19 recommendation. PLoS One. 2022;17(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tachibana I, Ferguson EL, Mahenthiran A, Natarajan JP, Masterson TA, Bahler CD, et al. Delaying cancer cases in urology during COVID-19: Review of the literature. J Urol. 2020;204(5):926–933. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katims AB, Razdan S, Eilender BM, Wiklund P, Tewari AK, Kyprianou N, Badani KK, Mehrazin R. Urologiconcology practice during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review on what can be deferrable vs. nondeferrable. In UrologicOncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2020 Oct 1 (Vol. 38, No. 10, pp. 783–792). Elsevier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH, et al. The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020;27:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahorsu DK, Lin C-Y, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aghamir SMK, Heshmat R, Ebrahimi M, Ketabchi SE, Dizaji SP, Khatami F. The impact of succinate dehydrogenase gene (SDH) mutations in renal cell carcinoma (RCC): A systematic review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:7929. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S207460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Azodian Ghajar H, Koohi Ortakand R. The Promising Role of MicroRNAs, Long Non-Coding RNAs and Circular RNAs in Urological Malignancies. Translational Res Uro. 2022;4(1):9–23. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rashedi S. Landscape of Circular Ribonucleic Acids in Urological Cancers. Translational Res Uro. 2021;3(2):45–47. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mirzaei A, Zendehdel K, Rashidian H, Aghaii M, Ghahestani SM, Roudgari H. The Impact of OPIUM and Its Derivatives on Cell Apoptosis and Angiogenesis. Translational Res Uro. 2020;2(4):110–117. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diamand R, Ploussard G, Roumiguié M, et al. Timing and delay of radical prostatectomy do not lead to adverse oncologic outcomes: results from a large European cohort at the times of COVID-19 pandemic. World J Urol. 2021;39(6):1789–1796. doi: 10.1007/s00345-020-03402-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nguyen D-D, Haeuser L, Paciotti M, et al. Systematic Review of Time to Definitive Treatment for Intermediate Risk and High Risk Prostate Cancer: Are Delays Associated with Worse Outcomes? J Urol. 2021;205(5):1263–1274. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ginsburg KB, Curtis GL, Timar RE, George AK, Cher ML. Delayed radical prostatectomy is not associated with adverse oncologic outcomes: implications for men experiencing surgical delay due to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Urol. 2020;204(4):720–725. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fallara G, Sandin F, Styrke J, et al. Prostate cancer diagnosis, staging, and treatment in Sweden during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Scand J Urol. 2021;55(3):184–191. doi: 10.1080/21681805.2021.1910341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All information, data, and photos are all provided through the manuscript, and additional will be provided if requested.