Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the nature of communication has changed dramatically owing to lockdowns and the need for social distancing with ongoing outbreaks. As a result, patient's help-seeking behavior for mental health may have changed. We summarized the research on help-seeking behavior for mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic and investigated changes that have occurred.

Methods

This study was a systematic review. We searched four literature databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CHINAHL, and PsycINFO. We included the following in the review: 1) studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and 2) studies that dealt with help-seeking behavior for mental health. Eligible studies were summarized according to characteristics such as research participants and study type.

Results

In total, 41 studies (38 observational studies 2 qualitative studies and 1 randomized trial) were eligible for the review. Most studies reported delays, decreases, or deficits in help-seeking behavior. The study participants included medical professionals, local residents, hospitals, children and adolescents, online participants, pregnant women, people who experienced intimate partner violence, those with eating disorders, and other individuals.

Limitations

Findings from observational studies may have bias as confounder. Meta-analysis could not be performed, because the studies had variations of design.

Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, delay in seeking help from mental health services may have resulted in lost opportunities to link patients with appropriate treatment and care. The COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing as of 2022. Therefore, it is important to examine the impact of the pandemic on mental health in future research.

Keywords: COVID-19, Help-seeking behavior, Mental health, Systematic review

1. Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the nature of communication changed dramatically owing to lockdowns and the need for social distancing. As a result, help-seeking behavior for mental health may have changed. Help-seeking behavior is a critical mediating factor in mental health outcomes. People with mental health problems are known to have low levels of help-seeking. Despite the availability of effective treatment options, some patients with major depression do not seek professional help. Sociodemographic and need factors influence help-seeking behavior. Although existing studies provide insight into the characteristics of help-seeking for major depression, cohort studies and research on beliefs about, barriers to, and the perceived need for treatment are lacking. Based on the present review, interventions to increase help-seeking behavior can be developed.

Numerous psychological models have been used to explain variations in help-seeking behavior among individuals (Magaard et al., 2017). Many issues regarding help-seeking behaviors have already been reported in populations and patients with specific risks. In young people and adolescents, past review studies have identified that most young people who self-injure do not seek professional help; they may not even seek medical attention after an overdose. The fact that a diagnosis of mental illness does not increase help-seeking behavior underscores the need to promote help-seeking behavior among those who engage in suicidal ideation or self-harm and have symptoms of mental illness (Oliver et al., 2005). In pregnant women, barriers to mental health help-seeking included not having sufficient time or being too busy, deciding not to seek care, cost, and not knowing where to go for help (Da Costa et al., 2018). In patients with eating disorders, a review identified both facilitators and barriers to care from the perspectives of those experiencing the interface firsthand (Johns et al., 2019). In patients who have experienced intimate partner sexual violence (IPSV), some differences in the procurement of support across cultural groups have been reported (Satyen et al., 2019). Help-seeking can also reduce the risk of future IPSV and decrease poor mental health outcomes (Wright et al., 2021). Across studies among suicidal individuals, some reviews have revealed low levels of help-seeking behavior with barriers to care and have discussed assessments in help-seeking and connections to suicide prevention (Hom et al., 2015; Hom and Stanley, 2021).

Interventions such as mental health literacy interventions are a promising method for promoting positive help-seeking attitudes with depression; however, there is no evidence that these lead to help-seeking behavior. There is even less evidence for other intervention types, such as efforts to destigmatize or provide help-seeking resource information (Gulliver et al., 2012; Kauer et al., 2014). The objective of the present study was to investigate the impact of help-seeking behaviors toward mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Methods

This systematic review was conducted and reported in accordance with the published protocol and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (Liberati et al., 2009).

2.1. Search strategy

We searched the following electronic databases: MEDLINE and EMBASE (from 1949), PsycINFO (from 1806), and CINAHL (from 1981). The following were used as search terms: ((coronavirus) OR (covid) AND (help-seeking)). Keywords were identified in the title, abstract, or both. There were no language restrictions. The search was performed in May 2022.

2.2. Data extraction and management

All records identified in the electronic databases and manual searches were loaded into ENDNOTE version X6 (Thomson Reuters, USA) and duplicate records were removed. Eligibility criteria were 1) the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and 2) addressed help-seeking behavior for mental health. Titles and/or abstracts of studies retrieved using the search strategy and those from additional sources were screened by the authors to identify those that potentially met the inclusion criteria outlined above. The full text of potentially eligible articles was retrieved and independently assessed by the researchers. Any disagreement over the eligibility of particular articles was resolved through discussion with another author. The researchers extracted the data, and any discrepancies were identified and resolved through discussion. Data extraction was conducted independently by at least two authors.

We extracted information and basic bibliographic data regarding the study country, study design, characteristics of study participants, number of participants, outcomes, measurements of help-seeking behavior, and associations with factors in baseline characteristics. These studies were summarized according to characteristics such as research participants and study type. Groups were basically classified as at-risk subjects. However, “online participants” was classified as a separate group, because direct communication was restricted by the pandemic. Summary tables were created for the eligible studies; however, meta-analysis was not performed because of the large variation in outcomes across studies. Ethics approval and consent to participate was not applicable, because this was the review by published papers.

3. Results

3.1. Study flow

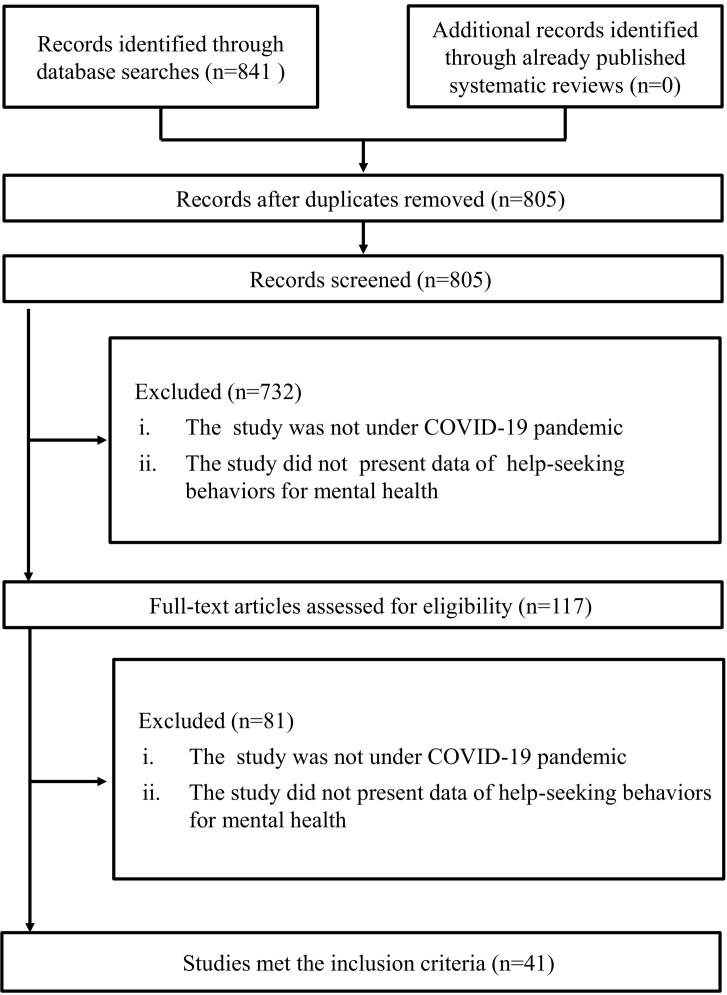

In the search, we identified 841 articles as follows: MEDLINE and EMBASE (n = 692), PsycINFO (n = 55), and CINAHL (n = 94), as presented Fig. 1 . After removing duplicates and studies that did not meet the selection criteria, 805 articles remained. These 805 articles were screened on the basis of titles and abstracts, leaving 117 potentially relevant articles that were reviewed for inclusion. The 117 articles were assessed by reviewing the full-text (Fig. 1). Of these, 41 articles, comprising 38 observational studies (23 cross-sectional studies, 5 time-series studies, 4 cohort studies, and 6 others), two qualitative studies and a randomize controlled trial were identified.

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart.

3.2. Study characteristics

As presented in Table 1 , we divided the 41 studies into 9 categories by type of study population, as follows: 1) medical professionals, 2) local residents, 3) hospitals, 4) children and adolescents, 5) online participants, 6) pregnant women, 7) individuals who experienced IPV, 8) individuals with eating disorders, and 9) others.

Table 1.

Summary of eligible studies.

| Author (year) | Country | Participants, n | Study design | Period | Measurement of help-seeking | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical professionals | ||||||

| She et al. (2021) | China | Public health workers (PHW), n = 9475 | Cross-sectional study | February 18 to March 1, 2020 | Sought help from professionals or did not (Yes or No) | PHW were more likely to report mental help-seeking (odds ratio [OR] range: 1.02–1.73, all p < 0.05); those who worked in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were less likely to seek help (OR = 0.57, p < 0.01). |

| Zhang et al. (2020) | China | Community workers, n = 702 | Cross-sectional study with online questionnaire | February 29 to March 27, 2020 | Have you ever thought about seeking help during the COVID-19 pandemic? (Yes or No) | Community workers who thought of seeking help, had more sources of work pressure, and higher stress had worse self-rated physical health. |

| Mrklas et al. (2020) | Canada | Health care professionals, n = 1414 and other workers who used SMS services, n = 3951 | Cross-sectional study, online by Text4Hope SMS service | March 23 to May 4, 2020 | Seeking support through Text4Hope by text message | Submitted by 44,992 Text4Hope subscribers (19.39 %) as help-seeking. |

| Chen et al. (2020) | United Kingdom (UK) | Presentations and referrals to the primary provider of mental health and community health services in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, plus service activity and deaths | Interrupted time-series analyses with respect to the time of lockdown in the UK | March 23, 2020 (lockdown, week 13) as the event date. Data up to and Including August 9, 2020. | Presentations and referrals to Mental Health Services | Demand for changes reflected a genuine reduction in need or a lack of help-seeking with pent-up demand. |

| Cai et al. (2020) | China | Recruited (case: n = 1173) frontline and (control: n = 1173) age- and sex-matched non-frontline medical workers | Case-control study, online questionnaire | February 11 to 26, 2020 | “Have you ever sought help from a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist since the COVID-19 pandemic began?” was used to estimate help-seeking behavior. | No significant difference was observed in terms of suicidal ideation in help-seeking (4.5 % vs. 4.5 %, adjusted OR = 1.00, 95 % CI = 0.53–1.87) in treatment for mental problems. |

| Smallwood et al. (2021) | Australia | Australian health care workers, nationwide, voluntary, anonymous (n = 9518) | Cross-sectional study, online | August 27 to October 23, 2020 | Sought help for stress or mental health issues from other sources: - Doctor or psychologist - Employee support program at workplace - Professional support program outside of work - None of the above |

Few used psychological well-being apps or sought professional help; those who did were more likely to have moderate to severe symptoms of mental illness. Rate of seeking help from a doctor or psychologist was 18.3 %. |

| Pascoe et al. (2021) | Australia | Australian junior and senior hospital medical staff (n = 9518) | Cross-sectional study, online | 27 August to 23 October 2020 | Sought help for stress or mental health issues from other sources: - Doctor or psychologist - Employee support program at workplace - Professional support program outside of work - None of above |

Seeking formal help for mental health concerns was uncommon for both groups, with more than three-quarters using no support services. Junior doctors were significantly more likely than senior doctors to see another doctor or psychologist for help with mental health symptoms during the pandemic (p = 0.005), albeit at low rates. Very few doctors reported seeking mental health support from employee or professional services at or outside their workplace. |

| Weibelzahl et al. (2021) | Germany | Health care professionals (n = 300) | Cross-sectional study, online | 22 May to 22 July 2020 | Barriers to seeking help for psychological strain | Most participants declined to receive psychological support to deal with the COVID-19 crisis. |

| Braquehais et al. (2022) | Spain | The sample was divided into two periods: before (n = 637) and after (n = 824) the official lockdown (14 March 2020). A total of 1461 medical e-records of health professionals (HPs) working in Catalonia who were admitted to the Galatea Care Program Clinical Unit | An observational retrospective chart review study. Data from all e-medical records of HPs consecutively admitted to the Galatea Care Program were downloaded from the program databases. | From June 2018 until December 2021, before and after Official lockdown in Spain (14 March 2020) | Type of referral, self-referral or directed referral | A significant increase (29.4 %) in the number of referrals to the specialized clinical unit during the pandemic, especially among physicians compared with that among nurses |

| Local residents | ||||||

| Wang et al., 2021 Feb 11, Wang et al., 2021 May 1 | China | Participants living in a severely affected area of Wuhan (n = 1397) and participants (n = 2794) living in other areas | Cross-sectional study, online via SMS | February 10 to February 20, 2020 | “During the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic, have you ever sought help from psychiatrists or clinical psychologists over the past month?” (Yes or No) | Participants from Wuhan had a significantly higher prevalence of any mental health problems and had a slightly higher rate of help-seeking behavior (7.1 % vs. 4.2 %; adjusted OR = 1.76, 95 % CI = 1.12–2.77). However, there was no significant difference in the proportion of the treatment of mental problems (3.5 % vs, 2.7 %; adjusted OR = 1.23, 95 % CI = 0.68–2.24) between the two groups. |

| Tambling et al. (2021) | United States (US) | Adults in the US who spoke English and were caring for a child younger than 18 years in their home were eligible to participate through Mechanical Turk (MTurk). (n = 322 at time 1, and n = 189 at time 2) | A follow-up study with time 1 and 2 | Early 2020 | Have you sought counseling or other professional help during the COVID-19 pandemic (Yes or No)? Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form (ATSPPHS-SF) was used to assess attitudes toward seeking help from mental health professionals (a 10-item questionnaire). | The binary question 18 (95 %) indicated that participants had sought help. Ratings regarding likelihood of seeking professional help were high. |

| Lueck (2021) | US | Representative sample of US adults (N = 5010) sampled from the Lucid marketplace survey platform | Cross-sectional survey | 2020 | Self-Stigma of Seeking Help measure (SSOSH; Vogel et al., 2006) was used to test stigma perceptions. Ten 5-point Likert items (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) were used for responses to statements such as, “I would feel okay about myself if I made the choice to seek professional help (R).” Current help-seeking was assessed with one Item: “Are you currently receiving counseling or therapy from a health care professional (e.g., psychologist, psychiatrist, social worker)?” (Yes or No) | The reasoned action framework explained 36 % of variance in help-seeking intentions in this US population and identified injunctive norms (social support) as the primary determinant of intention. Neither suicidal ideation, COVID-19 financial hardship, nor self-stigma regarding seeking help were determinants of help-seeking. |

| Chen et al. (2021) | China | Chinese residents in Wuhan and other cities of Hubei Province, (n = 3145) and (n = 3814) other participants | Two cross-sectional surveys; online self-administrated questionnaire | February 1–5 and February 20–24 (Wuhan shutdown on January 23) | The item of mental health help-seeking was reported as 2 = found and tried, 1 = found but not tried, 0 = not found yet, −1 = not looked for, and −2 = no need. | Compared with the first survey, the changes in scores for anxiety, depression, and stress in the second survey were decreased, but mental health help-seeking had no significant impact on anxiety, depression, or stress in the two surveys. |

| Zhong et al. (2020) | China | Recruited residents from four subpopulations: Wuhan residents (n = 2617), migrants from Wuhan (those who left Wuhan before lockdown, n = 930), other Hubei residents (n = 633), and residents of other provinces in China (“other residents” n = 3561) | Cross-sectional survey, online | January 27 to February 2, 2020 (Wuhan shutdown on January 23) | “During recent days, did you recognize that you need professional help from mental health specialists because of your high level of stress, negative emotions, poor sleep, or other mental health problems?” (Yes or No) “Did you seek any help from mental health specialists for your mental health problems?” (Yes or No) |

Among the four groups, Wuhan residents had the highest rate of any type of mental health problem; 63.0 % of mental health service users received services via Internet and telephone, and 83.1 % of participants with perceived mental health needs ascribed their lack of help-seeking to barriers regarding accessibility and availability. Among those with unmet mental health needs, 83.1 % ascribed their lack of seeking help from mental health professionals to barriers owing to poor accessibility and availability. |

| Jacoby and Li (2022) | US | Adults in Jewish households, New York, n = 4403 | Cross-sectional survey by random sampling | February to May 2021 | “Have you sought professional help, or are you planning to seek professional help, for symptoms of depression or anxiety?” (Yes or No) | No meaningful relationship between the general presence of mental health care services and help-seeking behavior was found. However, the zip code tabulation area-level density of office practices was significantly associated with service utilization among socially isolated, foreign-born, and Hispanic or non-white respondents. |

| Children and adolescents | ||||||

| Jeong et al. (2021) | US | Full-time undergraduate students in a large public university located in the Appalachian area (n = 1225) | Cross-sectional study, online | From March 25, 2020, the 10 days after campus closure owing to the outbreak of COVID-19 to May 8, 2020, the last day of spring classes. | Will seek mental and emotional help from; - Friend - Family - Professor/academic advisor - Free counseling service - Paid health professional - Social media - Website - Won't seek any help All measured from 1 to 5. |

First-generation college students (FGCS) were less likely to seek mental and emotional help from family (p < 0.01) and friends (p < 0.001) or “won't seek any help” (p < 0.05) compared with non-FGCSs. |

| Upton et al. (2021) | Australia | Subsample of APSALS (registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02280551) cohort of young adults (n = 443) | Prospective cohort study, compared with annual survey | Additional survey during COVID-19 restrictions (May–June 2020), and latest annual survey (August 2019–March 2020) | Self-reported help-seeking from a health professional. Participants were asked whether they had sought help for their mental health from a general practitioner or other qualified health professional (e.g. psychologist) in February and the month prior to completing the survey. | There was no increase in help-seeking over time (odds ratio 0.50; 95 % CI 0.19–1.32). |

| Marchini et al. (2021) | Belgium and Italy | Young adults aged 18 to 25 years (n = 825) | Cross-sectional study, online on the secured platform Research Electronic Data Capture | April 7 and May 4, 2020 | Changes in online contacts (i.e., through phone and social media) and offline contacts (i.e., face-to-face) with family and friends | Differences were found in online contacts with family and offline contacts with friends. |

| Mourouvaye et al. (2021) | Paris, France | Sick children in Necker Hospital (n = 234) | Retrospective cohort study | January 2018 to June 2020 (National COVID-19 lockdown, March–May 2020). | Incidence of admissions for suicidal behavior | Significant decrease in the incidence of admissions for suicidal behavior during the lockdown (adjusted incidence rate ratio: 0.46; 95 % CI 0.24 to 0.86). The association might result from reduced help-seeking and decreased hospital admission rates during lockdown, as well as cognitive and environmental factors. |

| Liang et al. (2020) | Guangdong, China | College students (n = 4164) | Cross-sectional study, online | At the peak of the outbreak, February 13 to 22, 2020 | “Counseling group” or “non-counseling group” according to whether they had sought psychological help. Experience with seeking psychological help. (Yes or No) | Fear, depression, and trauma scores were significantly higher in the counseling group than in the non-counseling group (p < 0.001). Fear (OR = 1.27, p < 0.001), depression (OR = 1.02, p = 0.032), trauma (OR = 1.08, p < 0.001), poor perceived mental health status (OR = 3.61, p = 0.001), and experience with seeking psychological help (OR = 7.06, p < 0.001) showed increased odds of seeking psychological help. |

| Wathelet et al. (2020) | France | University students living in France who experienced COVID-19 quarantine (n = 69,054) | Cross-sectional study, e-mail and online questionnaire | April 17 to May 4, 2020 | Seeking treatment for mental health reasons during the quarantine (if yes, whether they accessed the university medical service or another health professional) | Among all students, 4682 (6.8 %) reported seeing a professional for mental health reasons, and 1037 (1.5 %) reported having requested the university health service. Of 29,564 students with at least one outcome, 3675 (12.4 %) consulted a mental health professional, and 810 (2.7 %) used the university service. |

| Hospitals | ||||||

| Sveticic et al. (2021a) | Australia | Visitor at emergency departments (EDs) within the Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service (Number was not repotting, only percentage) | Time-series study, with descriptive and expected number | January to August 2020 | Number of suicidal presentations (including suicidal ideation, non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts) | At the peak of the pandemic, the reductions in suicidal presentations were the largest (29.8 % in March and 23.6 % in April 2020). Over the next 2 months, daily numbers of diagnosed COVID-19 cases remained low, and the difference between observed and projected numbers gradually narrowed (20.8 % in May and 14.6 % in June 2020). In July 2020, observed numbers exceeded projected numbers by 11.4 %, but then declined again in August 2020, coinciding with another resurgence of COVID-19. Between March and August 2020, there were 554 fewer suicidal presentations than expected. |

| Sveticic et al. (2021b) | Australia | Visitors to emergency departments (EDs) within the Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service, before COVID-19, (n = 3299) and after (n = 3190) the start of the COVID-19 pandemic | Case-series study | Before COVID-19, Mar–Aug 2019; after COVID-19, Mar–Aug 2020 | Number of suicidal and self-harm presentations to EDs | Significantly more suicidal and self-harm presentations among individuals younger than 18 years (16.8 % vs. 15.1 %, p = 0.041), and fewer among those with an indigenous background (5.2 % vs. 6.4 %, p = 0.035) after the start of the pandemic. More presenting individuals received a triage score indicating greater clinical acuity (19.5 % vs. 17.9 %, p = 0.043) and more presented involuntarily (22.2 % vs. 13.3 %, p < 0.001). More patients were discharged following suicidal and self-harm presentations (78.9 % vs. 74.4 %, p < 0.001), and fewer were admitted to inpatient care (17.9 % vs. 19.9 %, p = 0.038) or left the ED before being seen (5.4 % vs, 3.2 %, p < 0.001). |

| Smith et al. (2021) | Hawaii, US | Patients seen at Hawaii Pacific Neuroscience (HPN), which adapted their patient care to ensure continuity of neurological treatment (n = 367); 133 patients with migraine and 234 patients with other neurological conditions. | Cross-sectional study, telephone | April 22, to May 18, 2020 | Access to health care (Yes or No) - Difficulty obtaining medications - Skipped or ran out of medications - Unable to attend scheduled doctor visit - Unable to obtain diagnostic testing - Avoided seeing doctor for new health problem owing to pandemic - Trouble with health insurance - Participated in a telemedicine visit |

Several significant differences were found between migraine and non-migraine groups for health care access. Patients with migraine were significantly more likely to report running out of medications than those with other diagnoses (20/133, 15 % vs. 18/234, 7.7 %; p = 0.026). More patients avoided seeking medical help for new health problems because of the pandemic (30/133, 22.6 % vs. 30/234, 12.8 %; p = 0.015). |

| Wong et al. (2020) | Hong Kong, China | Older adults with multimorbidity in primary care (n = 583), recruited from 7 June 2016 to 23 October 2017 as the initial cohort. | Prospective cohort study, telephone | Pre-COVID-19, 3 April 2018 to 6 March 2019 and peri-COVID-19 period, 24 March to 15 April 2020 | Information on missed scheduled medical appointments was retrieved from the clinical management system in Hong Kong and was validated in another study. | In total, 16.5 % and 22.0 % of Participants missed their scheduled medical appointments for chronic disease care over a period of 3 months a year before and after the onset of the outbreak, respectively (p = 0.014). |

| Online | ||||||

| Tambling et al. (2022) | US | English-speaking individuals over the age of 18 who resided in the US, posted through the MTurk online worker platform n = 1545 | Cross-sectional study, online, national survey | April 7 and 14, 2020 | Outcomes measures on help-seeking during 60-day follow-up included three single-item indicators: “Have you sought counseling or other professional mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic?” and “Did you seek new supports or were you already receiving these services when the COVID-19 pandemic started?”. Propensity to seek psychological help was a single item: “How likely are you personally to seek professional help to manage stress or anxiety during COVID-19?”. Respondents rated this item on a 100-point scale. | Individuals with higher levels of anxiety rated their likelihood of help-seeking as higher, and those who sought psychological help reported higher levels of depression. |

| Scerri et al. (2021) | Malta | 2908 calls to a national mental health helpline | Time-series design | January to October 2020, 2 months prior to (pre-COVID) and 8 months during the pandemic period, which incorporated implementation of a partial lockdown | Calls for assistance | Although the number of deaths and cases had significantly increased in the latter months during the second COVID-19 wave, individuals were significantly focused on seeking information during a crisis as a means of coping and possibly to avoid mental health struggles that may have burdened them in the early months of the pandemic. |

| Singh et al. (2020) | India | Data by Goggle | Google Trends in health-related research | Three timeframes representing pre-lockdown (4–24 March), lockdown 1 (25 March–14 April), and lockdown 2 (15–27 April) periods | Keywords related to help-seeking for alcohol use disorders. | Online search interest in the two most popular keywords representing help-seeking behaviors for alcohol use disorders peaked in the lockdown 2 period. |

| Chen et al. (2022) | China | Weibo users, the diffusion levels of 705 original posts varied from 0 to 6, with an average of 1.15. | Diffusion level of help-seeking information on social media. Content analysis was conducted with multilevel regression analysis. | From 1 August 2020 to 11 August 2020. | Sender, content, and environmental factors to investigate what makes help-seeking messages become widely disseminated in social media networks. | Bandwagon cues, anger, instrumental appeal, and intermediate self-disclosure facilitated the diffusion level of help-seeking messages. |

| Intimate partner violence (IPV) | ||||||

| Vives-Cases et al. (2021) | Spain | Cases of 016 calls, police reports, women killed, and protection orders (PO) issued owing to IPV across Spain as a whole and by province (2015–2020). | Time-series design, descriptive ecological study | March and June 2020 | 016 calls, police reports, women killed, and POs issued owing to IPV | The COVID-19 lockdown fostered a change in help-seeking behavior among women affected by IPV. During the second quarter of 2020, the highest 016 call rate was recorded (12.19 per 10,000 women aged 15 or over). Police report rates (16.62), POs (2.81), and fatalities (0.19 per 1,000,000 women aged 15 years or over) decreased in the second quarter of 2020. In the third quarter, 016 calls decreased, and police reports and POs increased. |

| Sorenson et al. (2021) | US | Cases of emergency calls to police and hotlines for domestic violence, assault, and rape (4587 calls for domestic violence and 1091 rape calls). | Time-series design, an interrupted time-series analysis | January 1, 2020 to May 30, 2020 | Emergency calls to police and calls to rape crisis and domestic violence hotlines. | There was a decrease in help-seeking for sexual assault and assault in general, but not for domestic violence, during the initial phases of the COVID-19 outbreak. |

| Gama et al. (2020) | Portugal | People reporting domestic violence (n = 1062) | Cross-sectional study, online | April to October 2020 | Experiences of domestic violence and help-seeking during the pandemic (multiple response) - From whom did you seek help or advice after this? - What are the main reasons why you haven't sought help or advice from these people or services (so far)? - Did you or somebody else tell the police about this? - Which are the main reasons why you haven't told the police (so far)? |

Most victims did not seek help (62.3 %); the main reasons were considering it unnecessary, that help would not change anything, and feeling embarrassed about what had happened. Only 4.3 % of victims sought police help. The most common reasons for not coming forward to file a complaint were considering that the abuse was not severe and believing the police would not do anything. |

| Alvarez-Hernandez et al. (2022) | US | Videos related to IPV help-seeking from Univision's main website, the most-watched Spanish-speaking media network (29 videos) | An exploratory content analysis to determine frequencies and inductive interpretive content analysis to code for help-seeking messages | March 19 to April 21, 2020 | Content of videos | A total of 25 videos provided information about resources where individuals could seek help for IPV (86 %). Eight messages related to seeking help when experiencing IPV in times of a crisis were: (1) contact a professional resource; (2) contact law enforcement; (3) contact family, friends, and members of your community; (4) create a safety plan; (5) don't be afraid, be strong; (6) leave the situation; (7) protect yourself at home; and (8) services are available despite the pandemic. |

| Eating disorders | ||||||

| Nutley et al. (2021) | US | Social media posts, popular subreddits acknowledging eating disorders as the primary discussion topic | Qualitative analysis of social media posts | January 1 to May 31, 2020 | Evaluated using inductive, thematic data analysis | Six primary themes were identified: change in eating disorder symptoms, change in exercise routine, impact of quarantine on daily life, emotional well-being, help-seeking behavior, and associated risks and health outcomes. |

| Richardson et al. (2020) | Canada | Eating disorders and their caregivers, service utilization data from the National Eating Disorder Information Centre (NEDIC). (609 times) | A retrospective observational design | March 1 to April 30, 2020 | Anonymous NEDIC service utilization with symptoms. Symptoms were considered present (Yes or No) based on the self-report of help-seekers. | Among affected individuals, the number of contacts during the pandemic was significantly higher (n = 439, p < 0.001) than in 2018 (n = 197) and 2019 (n = 312). There were higher rates of eating disorder symptoms, anxiety, and depression in 2020 than in previous years. Thematic analysis of instant messages and chats during the pandemic revealed four emerging themes: 1) lack of access to treatment, 2) worsening of symptoms, 3) feeling out of control, and 4) need for support. |

| Pregnant women | ||||||

| Wang et al., 2021 Feb 11, Wang et al., 2021 May 1 | China | Pregnant women recruited from maternal health care centers across China (n = 19,515). | A cross-sectional study, online | February to March 2020 | Participants rated their intention to seek mental health services by choosing 1 of the following 3 options: “I don't need mental health services”; “I need mental health services, but I will not seek help from these services”; “I need mental health services and I will seek help from these services.” | More than half (3292/6248, 52.7 %) of participants reported they did not need mental health services; 28.3 % (1770/6248) of participants felt they needed mental health services but had no intention to seek help. Only 19 % (1186/6248) felt they needed mental health services and had the intention to seek help. The results of multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that age, education level, and gestational age were factors involved in not seeking help. However, COVID-19–related lockdowns in participants' place of residence, social support during the COVID-19 pandemic, and trust in health care providers were protective factors in participants' intention to seek help from mental health services. |

| Moyer et al. (2021) | Ghana | Pregnant women in Ghana, distributed via SMS related to pregnancy (n = 71). | Cross-sectional study, online, anonymous survey | July and August 2020 | Reports of care-seeking | Over one-third of participants (36.2 %) reported missing an in-person antenatal care (ANC) visit as a result of COVID-19; 6 (8.7 %) replaced their visit with a remote visit via telephone or video. Sixty-four percent (16 of 25 who missed an ANC appointment) reported not attending for fear of COVID-19 infection. |

| Other topics | Country | Participants, (n) | Study design | Period | Measurement of help-seeking | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balhara et al. (2020) | India | Patients in an ongoing project assessing the impact of disulfiram among patients with alcohol use disorder (n = 79). | Cross-sectional study | During the, nationwide lockdown after 25 March 2020 | Visitors to treatment center | A total of 28 (36.8 %) patients tried to attend follow-up at the treatment center; only five (17.8 %) were able to reach the center. Lack of transportation, restrictions by law-enforcement agencies, and fear of contracting COVID-19 infection during travel were the common barriers to treatment-seeking. |

| Sass et al. (2022) | UK | People who self-harm in the UK. (n = 14) | A qualitative study based on telephone and email interviews | The study explored experiences among people who self-harm during the first lockdown in March 2020 | “Factors affecting help-seeking during the pandemic” was used to identify factors that affected help-seeking using thematic analysis | Help-seeking was impeded by feeling like a burden and potential for spread of the virus. People who self-harm exercised self-reliance in response to “stay home” messaging, but some may have struggled without formal support. |

| Strongylou et al. (2022) | UK and Republic of Ireland | Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM), Survey, n = 1368; qualitative interview, n = 18 | Cross-sectional study and sequential, mixed-methods study | July and September 2020 | Remote mental help-seeking behavior during the first COVID-19 lockdown: Men were asked about their use of remote resources to seek mental health support during lockdown: “Have you accessed any of the following resources to help with your mental health since lockdown?” Participants could select Websites, Apps, Phone lines, or None of the above. | Identified multiple barriers and enablers to GBMSM seeking remote mental health help, with help primarily sought from GBMSM support organizations and generic online resources. |

| Amsalem et al. (2021) | US | English speaking US residents, 18–80 years old, with self-reported military experience with three groups: Video (n = 86), Vignette (n = 44), and No intervention (n = 42). | A randomized controlled trial; follow-up assessments were conducted 14 and 30 days after post-intervention assessment | 2020, COVID-19 era | Primary outcome measure was three items measuring “openness to seeking help” from the Attitude Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale (ATSPPH-SF). The chosen items specifically tested help-seeking intentions: “I might want to have psychological counseling in the future,” “I would want to get psychological help if I were worried or upset for a long period of time,” and “A person with an emotional problem is not likely to solve it alone; he or she is more likely to solve it with professional help.” Response options were: 1 = “disagree,” 2 = “partially disagree,” 3 = “partially agree,” and 4 = “agree.” The total score ranged from 4 to 12, with higher scores indicating greater help-seeking intentions. In this study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the ATSPPH items was 0.79. The ATSPPH-SF was assessed at four time points (i.e., baseline, post intervention, 14- and 30-day follow-up). | Brief video-based intervention yielded greater increase in treatment-seeking intentions among veterans. Increased treatment-seeking intentions in the video group only (95 % CI 0.51–1.13, p < 0.001); Cohen's d = 0.32; video from 7.4 (95 % CI 6.9–8.0) to 8.2 (95 % CI 7.7–8.8); vignette from 8.0 (95 % CI 7.3–8.6) to 8.1 (95 % CI 7.4–8.7); control from 7.3 (95 % CI 6.6–8.1) to 7.6 (95 % CI 6.9–8.3). |

3.3. Medical professionals

Nine studies involved medical professionals in areas affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. A researcher (She et al., 2021) found that public health workers were more likely to report mental health help-seeking whereas individuals who worked at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were less likely to seek help. Zhang (Zhang et al., 2020) reported that community workers with more thoughts about seeking help, more work pressure sources, and higher stress had worse self-rated physical health. Mrklas (Mrklas et al., 2020) found that submissions by 44,992 Text4Hope subscribers (19.39 %) were for seeking support. Chen (Chen et al., 2020) reported that COVID-19 has been associated with a system-wide decline in the use of mental health services, with some subsequent return in activity. “Supply” changes may have reduced access to mental health services for some. “Demand” changes may reflect a genuine reduction in need or a lack of help-seeking with pent-up demand. Cai (Cai et al., 2020) reported that no significant difference was observed in terms of suicidal ideation in help-seeking (4.5 % vs. 4.5 %, adjusted odds ratio = 1.00, 95 % confidence interval = 0.53–1.87) for treatment of mental problems. Swallwood (Smallwood et al., 2021) reported that few participants used psychological well-being apps or sought professional help; those who did were more likely to have moderate to severe symptoms of mental illness. The rate of seeking help from a doctor or psychologist was 18.3 %. Pascoe (Pascoe et al., 2021) revealed that seeking formal help for mental health concerns was uncommon for all groups, with more than three-quarters using no support services. Junior doctors were significantly more likely than senior doctors to see another doctor or psychologist for help with mental health symptoms during the pandemic (p = 0.005), albeit at low rates. Very few doctors reported seeking mental health support from employee or professional services at or outside their workplace. Weibelzahl (Weibelzahl et al., 2021) reported that when asked whether they would like to receive psychological support to deal with the crisis, most participants declined. Braquehais (Braquehais et al., 2022) showed there was a significant increase (29.4 %) in the number of referrals to specialized clinical units during the pandemic, especially with respect to physicians compared with that with respect to nurses.

3.4. Local residents

A total of six studies involved local residents of areas affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Wang (Wang et al., 2021 Feb 11, Wang et al., 2021 May 1) reported that participants from Wuhan had a significantly higher prevalence of any mental health problems and a slightly higher rate of help-seeking behavior. Among the subgroup of participants with any mental health problem, participants from Wuhan had a slightly higher rate of help-seeking behavior for mental health problems than did participants from other areas of China. However, there was no significant difference in the proportion of treatment for mental problems between the two groups. Tambling (Tambling et al., 2021) reported that from ratings on a short-form scale regarding attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help, the likelihood of seeking help was high, indicating positive feelings toward seeking professional help. This item assessed the likelihood of help-seeking rather than the actual behavior. Also, increasing severity of depressive symptoms resulted in an increased likelihood of seeking medical help. The likelihood of help-seeking heightened the need to consider the availability of services for those caring for children during the community-wide crisis. Lueck (2021) found that participants were more convinced of the positive outcomes of help-seeking and slightly less convinced that help-seeking would be a pleasant experience. Intentions were primarily a function of injunctive norms, i.e., the belief that important others approved of the participant's help-seeking if they chose to seek help. The study indicated that social normative cues, and injunctive norm cues in particular (social support), could be effective targets for help-seeking and suicide prevention campaigns. Chen (Chen et al., 2021) reported that 1 week after the Wuhan shutdown, anxiety, depression, and stress in participants had all increased. Compared with those in the first survey, the changes in scores for anxiety, depression, and stress in the second survey were decreased, but mental health help-seeking had no significant impacts on anxiety, depression, and stress in the two surveys. Zhong (Zhong et al., 2020) reported that 63.0 % of mental health service users received services via Internet and telephone, and 83.1 % of participants with perceived mental health needs ascribed their lack of help-seeking to barriers regarding accessibility and availability. The high proportions of telephone and Internet users among Wuhan residents and migrants from Wuhan indicated that help-seeking behavior and patterns were dramatically changed by the epidemic response to enforce lockdown, with resulting social isolation. Jacoby and Li (2022) reported that whereas they found no meaningful relationship between the general presence of mental health care services and help-seeking behavior, the zip code tabulation area-level density of office practices was significantly associated with service utilization among socially isolated, foreign-born, and Hispanic or non-white respondents.

3.5. Children and adolescents

Six studies included children, adolescents, and young adults (university students). Jeong et al. (2021) showed that whereas FGCSs (first-generation college students) and non-FGCSs reported similar levels of stress and depression, FGCSs had higher anxiety and lower levels of life satisfaction and supportive parental communication than non-FGCSs. FGCSs were less likely to seek mental and emotional help from family and friends than non-FGCSs, even though those help-seeking behaviors may mitigate their mental distress and enhance their life satisfaction. In a study by Upton (Upton et al., 2021), participants were asked whether they had sought help for their mental health from a general practitioner or other qualified health professional, such as a psychologist, in February and in the month prior to completing the survey. Mean symptom scores on the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire and 7-item General Anxiety Disorder scale increased from before to during the COVID-19 restrictions, but there was no increase in help-seeking over time. There were no differences by sex for reported changes in help-seeking from before to during the pandemic. Marchini (Marchini et al., 2021) reported that the lack of ability to face adversity, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown, was associated with a help-seeking attitude during this period. A help-seeking attitude and resilience have been linked, including dealing with stigma, in an exploration of pathways. People who seek help for their mental health concerns feel stigmatized because they may be viewed as less resilient. These findings question the role of psychological distress during the lockdown period or the relationship with a possible mental health disorder, justifying a help-seeking attitude. Mourouvaye (Mourouvaye et al., 2021) found a significant decrease in the incidence of admissions for suicide behaviors during lockdown. This association might result from reduced help-seeking and decreased hospital admission rates during lockdown, as well as cognitive and environmental factors. Liang (Liang et al., 2020) reported that the proportion of respondents seeking psychological help in response to the COVID-19 epidemic was low, at only 0.64 %. College students in poor psychological condition more frequently sought psychological counseling. Fear, depression, trauma, experiences with seeking psychological help, and perceived mental health can effectively predict psychological help-seeking behavior. The study findings emphasized the importance of closely monitoring college students' psychological status, providing psychological intervention, and improving the probability of seeking psychological help. Wathelet (Wathelet et al., 2020) reported that the prevalence of suicidal thoughts, severe distress, high levels of perceived stress, severe depression, and high levels of anxiety was 11.4 %, 22.4 %, 24.7 %, 16.1 %, and 27.5 %, respectively, with 42.8 % of participants reporting at least one outcome, among whom 12.4 % reported seeing a health professional. Among all students, 6.8 % reported seeing a professional for mental health reasons, and 1.5 % reported having requested university health services. Of the students with at least one outcome, 12.4 % consulted a mental health professional and 2.7 % used university services.

3.6. Hospitals

Four studies included visitors to hospital settings such as emergency departments and primary care. Sveticic (Sveticic et al., 2021a) indicated changes in help-seeking behavior, with fewer people willing to seek help for suicidal behavior through in-hospital consultation owing to fears of contracting COVID-19. Also, same authors (Sveticic et al., 2021b) separately reported that since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, indigenous Australians and individuals with less severe suicidal and self-harm behaviors had significantly reduced presentations whereas those younger than age 18 years had more presentations. Patients presenting for suicidal behavior had fewer admissions to inpatient care. It is therefore considered vital to continue to promote help-seeking among at-risk individuals through models of care that are adaptable to the fast-changing circumstances of the pandemic and tailored to the needs of vulnerable groups. Smith (Smith et al., 2021) found that more participants avoided seeking medical help for new health problems because of the pandemic. Telemedicine was well received by nearly all patients who took advantage of the option. Wong (Wong et al., 2020) reported significant increases in loneliness, anxiety, and insomnia after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Missed medical appointments over a 3-month period increased from 16.5 % a year earlier to 22.0 % after the onset of the pandemic.

3.7. Online

Four studies involved individuals online. Tambling (Tambling et al., 2022) reported that individuals with higher levels of anxiety rated their likelihood of seeking help as higher and those who did seek psychological help reported higher levels of depression. Scerri (Scerri et al., 2021) reported that in the pre-COVID-19 phase, calls for assistance were related to information needs and depression. With implementation of a partial lockdown coupled with the first local deaths and spikes in the number of diagnosed cases, a significant increase in the number of calls targeting mental health, medication management, and physical and financial issues were identified. Following the removal of local restrictions, the number of calls decreased significantly; however, with the subsequent reintroduction of restrictions, coupled with the rise in cases and deaths, the assistance requested significantly targeted informational needs. Singh (Singh et al., 2020) reported that online search interest, with the two most popular keywords representing help-seeking behaviors for alcohol use disorders, peaked during the lockdown periods. Chen (Chen et al., 2022) investigated which sender, content, and environmental factors led to help-seeking messages being disseminated through social media networks. Bandwagon cues, anger, instrumental appeal, and intermediate self-disclosure facilitated the diffusion level of help-seeking messages.

3.8. Intimate partner violence (IPV)

Four studies involved people who were affected by IPV. Vives-Cases (Vives-Cases et al., 2021) reported that the COVID-19 lockdown fostered a change in the help-seeking behavior of women who had experienced IPV. Differences between the volume of contacts made via 016 calls and the police reports generated provided evidence regarding the existence of barriers to IPV service access during lockdown and the period of remote working. Sorenson (Sorenson et al., 2021) reported a decrease in help-seeking for sexual assault and assault in general, but not for domestic violence, during the initial phases of the COVID-19 outbreak. Gama (Gama et al., 2020) reported that most victims did not seek help (62.3 %), the main reasons being that they considered it unnecessary, felt that seeking help would not change anything, and felt embarrassed about what had happened. Only 4.3 % of victims sought police help. The most common reasons for not coming forward to file a complaint were considering that the abuse was not severe and believing the police would not do anything. Alvarez-Hernandez (Alvarez-Hernandez et al., 2022) identified eight main messages related to seeking help when experiencing IPV in times of a crisis: (1) contact a professional resource; (2) contact law enforcement; (3) contact family, friends, and members of your community; (4) create a safety plan; (5) don't be afraid, be strong; (6) leave the situation; (7) protect yourself at home; and (8) services are available despite the pandemic.

3.9. Eating disorders

Two studies investigated patients with an eating disorder. Nutley (Nutley et al., 2021) identified six primary themes: change in eating disorder symptoms, change in exercise routine, impact of quarantine on daily life, emotional well-being, help-seeking behavior, and associated risks and health outcomes. Content that fell under the overarching theme of help-seeking behavior detailed users' attempts to seek professional or informal help for disordered eating behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. In seeking help on behalf of another individual, 10 users (3.3 %) searched for advice on how to help a loved one with an eating disorder as they dealt with pandemic-related anxiety. Richardson (Richardson et al., 2020) reported that the number of total contacts for help-seeking significantly increased from 2018 to 2019 and from 2018 to 2020 (p < 0.001). Among affected individuals (80.4 % women), the number of contacts during the pandemic period was significantly higher than in 2018 and 2019. There were higher proportions of eating disorder symptoms, anxiety, and depression in 2020 than in previous years. Thematic analysis of chats and instant messages during the pandemic revealed four emerging themes: 1) lack of access to treatment, 2) worsening of symptoms, 3) feeling out of control, and 4) need for support.

3.10. Pregnant women

Two included studies were conducted among pregnant women. Wang (Wang et al., 2021 Feb 11, Wang et al., 2021 May 1) found that more than half (52.7 %) of participants reported that they did not need mental health services. In total, 28.3 % of participants felt that they needed mental health services but had no intention of seeking help. Only 19 % of women felt that they needed mental health services and had the intention to seek help. The results of multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that age, education level, and gestational age were factors in not seeking help. However, COVID-19–related lockdowns in participants' place of residence, social support during the COVID-19 pandemic, and trust in health care providers were protective factors in participants' intention to seek help from mental health services. Moyer (Moyer et al., 2021) found that over one-third of participants (36.2 %) reported that they had missed an in-person antenatal clinic (ANC) visit as a result of COVID-19. However, 6 (8.7 %) women had replaced the missed ANC visit with a remote visit via phone or video. Sixty-four percent reported not attending for fear of COVID-19 infection.

3.11. Other topics

Balhara (Balhara et al., 2020) reported that a lack of transportation, restrictions by law-enforcement agencies, and fear of contracting COVID-19 infection during travel were the common barriers to treatment-seeking among patients with alcohol use disorder. Reduced help-seeking behavior owing to safety concerns has also been reported during previous pandemics. The number of days since the last use of alcohol was the only variable independently associated with an attempt to seek alcohol during the lockdown period. There is a need to address barriers to help-seeking going forward during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sass (Sass et al., 2022) reported that those who self-harm were inhibited from seeking help because they felt burdened or feared spread of the virus. Participants practiced self-reliance in response to “stay home” messaging, but some may have struggled without formal support. Strongylou (Strongylou et al., 2022) identified multiple barriers and enablers to gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) seeking remote mental health help, with help primarily sought from GBMSM support organizations and generic online resources. Finally, Amsalem (Amsalem et al., 2021) reported a randomized controlled trial using a video-based intervention among veterans. The trial aimed to screen for clinical symptoms and evaluate the efficacy of a brief, online social contact-based video intervention in increasing treatment-seeking intentions among veterans. Participants were randomized to either a (a) brief video-based intervention, (b) written vignette intervention, or (c) nonintervention control group. The findings showed that the brief video intervention increased treatment-seeking intentions, most likely through identification and emotional engagement with the video protagonist.

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 epidemic had a significant impact on the incidence of mental illness and access to health care facilities and treatment, and consequently, on help-seeking behavior. Individuals who had previous issues or high risk population with help-seeking behavior were even more restricted. Studies on help-seeking behaviors were conducted in a variety of populations and settings, from general to specific populations with clinical and social risk factors.

4.1. Stigma as a barrier to help-seeking behaviors

As some studies suggested, stigma because of mental health problems owing to COVID-19 infection and risk of infection is an important factor in help-seeking behavior during the pandemic. Stigma was a mediator of help-seeking behavior and had a small to moderately negative effect on help-seeking. Internalized and treatment stigma was most often associated with reduced help-seeking behavior. Stigma was the highest ranked barrier to help-seeking, with disclosure concerns the most commonly reported stigma barrier. A detailed conceptual model was derived describing the processes contributing to, and counteracting, the deterrent effect of stigma on help-seeking. Ethnic minorities, youth, men, and those in military and health professions were disproportionately deterred by stigma (Clement et al., 2015; Coleman et al., 2017).

4.2. Health professionals

A review focused on Chinese mental health professionals found (Shi et al., 2020) that frequently reported barriers to help-seeking for mental health among Chinese adults included a preference for self-reliance, seeking help from alternate sources, low perceived need for help-seeking, a lack of affordability, and negative attitudes toward or poor experiences with help-seeking. Less frequently mentioned barriers included stigma, family opposition, limited knowledge about mental illness, a lack of accessibility, unwillingness to disclose mental illness, and fear of burdening the family. These supports for help-seeking behavior should be a high priority issue. Findings from our review suggested that health care professionals are unable to engage in appropriate help-seeking behaviors owing to a heavy workload, stigma from risk of infection and even poor mental health because health care workers experience heavy stress levels during COVID-19 epidemic waves.

4.3. Online help-seeking

Approaches to improving help-seeking among young people should consider the role of the Internet and online resources as an adjunct to offline help-seeking. Even during the pandemic, such approaches would be useful, but with limitations. In particular, young people would prefer to seek help via social networks that are commonly used among their peers (Michelmore and Hindley, 2012). Some studies in our review reported similar findings. One review identified opportunities and challenges in this area (Pretorius et al., 2019) and highlighted the limited use of theoretical frameworks to conceptualize online help-seeking. Self-determination theory and the help-seeking model provide promising starting points for the development of online help-seeking theories. Text-based queries via an Internet search engine were the most commonly identified help-seeking approaches. Social media, government or charity websites, live chat, instant messaging, and online communities were also used. Key benefits include anonymity and privacy, immediacy, ease of access, inclusivity, the ability to connect with others and share experiences, and a greater sense of control over the help-seeking journey. Online help-seeking has the potential to meet the needs of individuals with a preference for self-reliance or to act as a gateway to further help-seeking. Barriers to help-seeking included a lack of mental health literacy, concerns about privacy and confidentiality, and uncertainty about the trustworthiness of online resources. Until now, there has been limited development and use of theoretical models to guide research into online help-seeking.

4.4. Development of new interventions

Developments of more interventions to promote health-seeking behaviors are needed. However, the evidence was limited in our review. Amsalem reported a video-based intervention among veterans and presented evidence for increased intention to seek treatment among participants. More effective interventions that target multiple and flexible populations are desirable.

4.5. Strengths and limitations

This report was a comprehensive systematic review. However, the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing globally, with additional reports being published continuously. We may need to update the present review in the future once the pandemic has been declared at an end. Findings from observational studies may have bias as confounder. Meta-analysis could not be performed, because the studies had variations of design. Also, there is no gold standard with respect to measures of help-seeking behavior; therefore, the validity and confidence in our findings are still uncertain, to some extent. Terms varied among studies; therefore, there may be some missed or misinterpreted content regarding help-seeking. However, many studies measured changes in actual behaviors rather than attitudes toward help-seeking behavior.

5. Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a delay in seeking help from mental health services may have resulted in lost opportunities to link patients with appropriate treatment and care. The COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing as of 2022. It is therefore important to continue to examine the impact of the pandemic on mental health.

Author statement

All persons who meet authorship criteria are listed as authors, and all authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content, including participation in the concept, design, analysis, writing, or revision of the manuscript. Furthermore, each author certifies that this material or similar material has not been and will not be submitted to or published in any other publication before its appearance in the Journal of Affective disorders.

Funding

The review was supported by funding from the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research, (KAKEN-C), 20K10337, Japan.

Availability of data materials

The data supporting this review can be found in the database and journals mentioned throughout the manuscript text.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

NY was responsible for the study concept and design. NY also performed the review, analysis and drafted the manuscript, YK performed the review, contributed to writing the manuscript and provided critical review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgment

We thank for Ms. Hiromi Muramatsu for her helpful assistance.

References

- Alvarez-Hernandez L.R., Cardenas I., Bloom A. COVID-19 pandemic and intimate partner violence: an analysis of help-seeking messages in the Spanish-speaking media. J. Fam. Violence. 2022;37(6):939–950. doi: 10.1007/s10896-021-00263-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsalem D., Lazarov A., Markowitz J.C., Gorman D., Dixon L.B., Neria Y. Increasing treatment-seeking intentions of US veterans in the Covid-19 era: a randomized controlled trial. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38(6):639–647. doi: 10.1002/da.23149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balhara Y.P.S., Singh S., Narang P. Effect of lockdown following COVID-19 pandemic on alcohol use and help-seeking behavior: observations and insights from a sample of alcohol use disorder patients under treatment from a tertiary care center. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020;74(8):440–441. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braquehais M.D., Gómez-Duran E.L., Nieva G., Valero S., Ramos-Quiroga J.A., Bruguera E. Help seeking of highly specialized mental health treatment before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among health professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19(6):3665. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q., Feng H., Huang J., Wang M., Wang Q., Lu X., Xie Y., Wang X., Liu Z., Hou B., Ouyang K., Pan J., Li Q., Fu B., Deng Y., Liu Y. The mental health of frontline and non-frontline medical workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: a case-control study. J. Affect. Disord. 2020 Oct;1(275):210–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A., Ng A., Xi Y., Hu Y. What makes an online help-seeking message go far during the COVID-19 crisis in mainland China? A multilevel regression analysis. Digit Health. 2022;8 doi: 10.1177/20552076221085061. 20552076221085061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Li M., Wang Y., Zhang L., Tan X. Changes in anxiety, depression, and stress in 1 week and 1 month later after the Wuhan shutdown against the COVID-19 epidemic. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021;21:1–8. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2021.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Jones P.B., Underwood B.R., Moore A., Bullmore E.T., Banerjee S., Osimo E.F., Deakin J.B., Hatfield C.F., Thompson F.J., Artingstall J.D., Slann M.P., Lewis J.R., Cardinal R.N. The early impact of COVID-19 on mental health and community physical health services and their patients' mortality in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, UK. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;131:244–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement S., Schauman O., Graham T., Maggioni F., Evans-Lacko S., Bezborodovs N., Morgan C., Rüsch N., Brown J.S., Thornicroft G. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol. Med. 2015;45(1):11–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman S.J., Stevelink S.A.M., Hatch S.L., Denny J.A., Greenberg N. Stigma-related barriers and facilitators to help seeking for mental health issues in the armed forces: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Psychol. Med. 2017 Aug;47(11):1880–1892. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa D., Zelkowitz P., Nguyen T.V., Deville-Stoetzel J.B. Mental health help-seeking patterns and perceived barriers for care among nulliparous pregnant women. Arch. Womens Ment. Health. 2018;21(6):757–764. doi: 10.1007/s00737-018-0864-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama A., Pedro A.R., de Carvalho M.J.L., Guerreiro A.E., Duarte V., Quintas J., Matias A., Keygnaert I., Dias S. Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal port. J. Public Health. 2020;38(Suppl. 1):32–40. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdac024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver A., Griffiths K.M., Christensen H., Brewer J.L. A systematic review of help-seeking interventions for depression, anxiety and general psychological distress. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;16(12):81. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hom M.A., Stanley I.H., Joiner T.E., Jr. Evaluating factors and interventions that influence help-seeking and mental health service utilization among suicidal individuals: a review of the literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2015;40:28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hom M.A., Stanley I.H. Considerations in the assessment of help-seeking and mental health service use in suicide prevention research. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2021;51(1):45–47. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby A., Li Y. Mental health care access and individual help-seeking during the Covid-19 pandemic. Community Ment. Health J. 2022;25:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10597-022-00973-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H.J., Kim S., Lee J. Mental health, life satisfaction, supportive parent communication, and help-seeking sources in the wake of COVID-19: firstgeneration college students (FGCS) Vs. non-first-generation college students (non-FGCS) J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 2021 doi: 10.1080/87568225.2021.1906189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johns G., Taylor B., John A., Tan J. Current eating disorder healthcare services - the perspectives and experiences of individuals with eating disorders, their families and health professionals: systematic review and thematic synthesis. BJPsych Open. 2019;5(4) doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer S.D., Mangan C., Sanci L. Do online mental health services improve help-seeking for young people? A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014;16(3) doi: 10.2196/jmir.3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S.W., Chen R.N., Liu L.L., Li X.G., Chen J.B., Tang S.Y., Zhao J.B. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on Guangdong college students: the difference between seeking and not seeking psychological help. Front. Psychol. 2020;4(11):2231. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P.C., Ioannidis J.P., Clarke M., Devereaux P.J., Kleijnen J., Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lueck J.A. Help-seeking intentions in the U.S. population during the COVID-19 pandemic: examining the role of COVID-19 financial hardship, suicide risk, and stigma. Psychiatry Res. 2021;303 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaard J.L., Seeralan T., Schulz H., Brütt A.L. Factors associated with help-seeking behaviour among individuals with major depression: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchini S., Zaurino E., Bouziotis J., Brondino N., Delvenne V., Delhaye M. Study of resilience and loneliness in youth (18–25 years old) during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown measures. J. Community Psychol. 2021;49(2):448–468. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelmore L., Hindley P. Help-seeking for suicidal thoughts and self-harm in young people: a systematic review. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2012;42(5):507–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourouvaye M., Bottemanne H., Bonny G., Fourcade L., Angoulvant F., Cohen J.F., Ouss L. Association between suicide behaviours in children and adolescents and the COVID-19 lockdown in Paris, France: a retrospective observational study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021;106(9):918–991. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer C.A., Sakyi K.S., Sacks E., Compton S.D., Lori J.R., Williams J.E.O. COVID-19 is increasing ghanaian pregnant women's anxiety and reducing healthcare seeking. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021;152(3):444–445. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrklas K., Shalaby R., Hrabok M., Gusnowski A., Vuong W., Surood S., Urichuk L., Li D., Li X.M., Greenshaw A.J., Agyapong V.I.O. Prevalence of perceived stress, anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in health care workers and other Workers in Alberta during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional survey. JMIR Ment Health. 2020 Sep 25;7(9) doi: 10.2196/22408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutley S.K., Falise A.M., Henderson R., Apostolou V., Mathews C.A., Striley C.W. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on disordered eating behavior: qualitative analysis of social media posts. JMIR Ment Health. 2021;8(1) doi: 10.2196/26011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver M.I., Pearson N., Coe N., Gunnell D. Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: cross-sectional study. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2005;186:297–301. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe A., Paul E., Johnson D., Putland M., Willis K., Smallwood N. Differences in coping strategies and help-seeking behaviours among Australian junior and senior doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021 Dec 16;18(24):13275. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182413275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius C., Chambers D., Coyle D. Young People's online help-seeking and mental health difficulties: systematic narrative review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019;21(11) doi: 10.2196/13873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson C., Patton M., Phillips S., Paslakis G. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on help-seeking behaviors in individuals suffering from eating disorders and their caregivers. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2020;67:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sass C., Farley K., Brennan C. "They have more than enough to do than patch up people like me." experiences of seeking support for self-harm in lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022;29(4):544–554. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satyen L., Rogic A.C., Supol M. Intimate partner violence and help-seeking behaviour: a systematic review of cross-cultural differences. J. Immigr. Minor. Health. 2019;21(4):879–892. doi: 10.1007/s10903-018-0803-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scerri J., Sammut A., Cilia Vincenti S., Grech P., Galea M., Scerri C., Calleja Bitar D., Dimech Sant S. Reaching out for help: calls to a mental health helpline prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18(9):4505. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She R., Wang X., Zhang Z., Li J., Xu J., You H., Li Y., Liang Y., Li S., Ma L., Wang X., Chen X., Zhou P., Lau J., Hao Y., Zhou H., Gu J. Mental health help-seeking and associated factors among public health workers during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Front. Public Health. 2021;11(9) doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.622677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W., Shen Z., Wang S., Hall B.J. Barriers to professional mental health help-seeking among Chinese adults: a systematic review. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;20(11):442. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Sharma P., Balhara Y.P.S. The impact of nationwide alcohol ban during the COVID-19 lockdown on alcohol use-related internet searches and behaviour in India: an infodemiology study. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;40(2):196–200. doi: 10.1111/dar.13187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood N., Karimi L., Pascoe A., Bismark M., Putland M., Johnson D., Dharmage S.C., Barson E., Atkin N., Long C., Ng I., Holland A., Munro J., Thevarajan I., Moore C., McGillion A., Willis K. Coping strategies adopted by australian frontline health workers to address psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2021;72:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M., Nakamoto M., Crocker J., Tiffany Morden F., Liu K., Ma E., Chong A., Van N., Vajjala V., Carrazana E., Viereck J., Liow K. Early impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on outpatient migraine care in Hawaii: results of a quality improvement survey. Headache. 2021 Jan;61(1):149–156. doi: 10.1111/head.14030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson S.B., Sinko L., Berk R.A. The endemic amid the pandemic: seeking help for violence against women in the initial phases of COVID-19. J. Interpers. Violence. 2021;36(9–10):4899–4915. doi: 10.1177/0886260521997946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strongylou D.E., Flowers P., McKenna R., Kincaid R.A., Clutterbuck D., Hammoud M.A., Heng J., Kerr Y., Frankis J.S., McDaid L. Understanding and responding to remote mental health help-seeking by gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) in the U.K. and Republic of Ireland: a mixed-method study conducted in the context of COVID-19. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2022;10(1):357–378. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2022.2053687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sveticic J., Stapelberg N.J., Turner K. A suicide prevention during COVID-19: identification of groups with reduced presentations to emergency departments. Australas. Psychiatry. 2021;29(3):333–336. doi: 10.1177/1039856221992632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sveticic J., Stapelberg N.J., Turner K. Reduced suicidal presentations to emergency departments during the COVID-19 outbreak in Queensland, Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2021;214(6):284. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50981. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambling R.R., Russell B.S., Fendrich M., Park C.L. Predictors of mental health help-seeking during COVID-19: social support, emotion regulation, and mental health symptoms. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2022;14:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11414-022-09796-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambling R., Russell B., Tomkunas A., Horton A., Hutchison M. Factors contributing to parents' psychological and medical help seeking during the COVID-19 global pandemic. Fam. Community Health. 2021;44(2):87–98. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton E., Clare P.J., Aiken A., Boland V.C., Torres C., Bruno R., Hutchinson D., Kypri K., Mattick R., McBride N., Peacock A. Changes in mental health and help-seeking among young Australian adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: a prospective cohort study. Psychol. Med. 2021;10:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721001963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vives-Cases C., Parra-Casado D., Estévez J.F., Torrubiano-Domínguez J., Sanz-Barbero B. Intimate partner violence against women during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021 Apr 28;18(9):469. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel D.L., Wade N.G., Haake S. Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006;53(3):325–337. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]