Abstract

The binding profile of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotypes 1 and 2 to various glycosphingolipids was evaluated by using thin-layer chromatogram overlay. A. pleuropneumoniae whole cells recognized glucosylceramide (Glcβ1Cer), galactosylceramide (Galβ1Cer) with hydroxy and nonhydroxy fatty acids, sulfatide (SO3-3Galβ1Cer), lactosylceramide (Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer), gangliotriaosylceramide GgO3 (GalNAcβ1-4Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer), and gangliotetraosylceramide GgO4 (Galβ1-3GalNAcβ1-4Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer) glycosphingolipids. We observed no binding to globoseries, globotriaosylceramide Gb3, globoside Gb4, or Forssman Gb5 glycosphingolipids or to gangliosides GM1, GM2, GM3, GD1a, GD1b, GD3, and GT1b. The A. pleuropneumoniae strains tested also failed to detect phosphatidylethanolamine or ceramide. Interestingly, extracted lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of serotype 1 and serotype 2 as well as detoxified LPS of serotype 1 showed binding patterns similar to that of whole bacterial cells. Binding to GlcCer, GalCer, sulfatide, and LacCer, but not to GgO3 and GgO4 glycosphingolipids, was inhibited after incubation of the bacteria with monoclonal antibodies against LPS O antigen. These findings indicate the involvement of LPS in recognition of three groups of glycosphingolipids: (i) GlcCer and LacCer, where glucose is probably an important saccharide sequence required for LPS binding; (ii) GalCer and sulfatide glycosphingolipids, where the sulfate group is part of the binding epitope of the isoreceptor; and (iii) GgO3 and GgO4, where GalNacβ1-4Gal disaccharide represents the minimal common binding epitope. Taken together, our results indicate that A. pleuropneumoniae LPS recognize various saccharide sequences found in different glycosphingolipids, which probably represents a strong virulence attribute.

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae is the causative agent of porcine fibrinohemorrhagic necrotizing pleuropneumonia (23). Twelve serotypes of A. pleuropneumoniae based on capsular and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) antigens have been recognized (24). Serotypes 1 and 5 are predominant in Québec, while serotype 2 is dominant in most European countries (22). Several bacterial factors have been suggested as important virulence attributes of A. pleuropneumoniae. The hemolytic and cytotoxic RTX toxins have been shown to be major virulence factors (6). In addition, the polysaccharidic capsule, some outer membrane proteins, and LPS also seem to be involved in virulence (9, 12, 30). We have shown that LPS play a major role in adherence of A. pleuropneumoniae to porcine respiratory tract cells and mucus (1, 2, 13, 25). The LPS are complex molecules composed of three well-defined regions: lipid A; the core region, which is an oligosaccharide containing Kdo; and the O antigen, a polysaccharide chain consisting of repeated units (11).

Selection of various tissues (tropism) by bacteria, virus, and toxins prior to colonization and infection is a well-known phenomenon (15, 16, 21, 32). In the colonization process, recognition of the carbohydrate moiety of glycoproteins and glycosphingolipids is a specific interaction which requires an adhesin (3, 30). A number of pulmonary pathogens, associated with infections in humans, specifically recognized the carbohydrate sequence GalNAcβ1-4Gal isolated from human lung tissues (19). It was recently shown that the gangliotetraosylceramide GgO4 (asialo-GM1) glycosphingolipid, expressed by human regenerating respiratory epithelial cells, is recognized by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (5). Another report demonstrated a specific binding of P. aeruginosa LPS to GgO4 glycosphingolipid on thin-layer chromatograms (TLC) (8).

In this study, putative glycosphingolipid receptors for A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 and serotype 2, whole cells as well as extracted LPS, were identified by using a TLC binding assay and various glycosphingolipids of acid and nonacid nature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Glycosphingolipids.

The lipids and glycosphingolipids used in this study (Table 1) were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, Calif.) or Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, Ontario, Canada).

TABLE 1.

Glycosphingolipids used in the TLC binding assay

| No. | Name | Structure |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cer | Cer |

| 2 | GlcCer | Glcβ1Cer |

| 3 | GalCer type I | Galβ1Cera |

| 4 | GalCer type II | Galβ1Cerb |

| 5 | Sulfatide | SO3-3Galβ1Cer |

| 6 | LacCer | Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer |

| 7 | GM3 | NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer |

| 8 | GM2 | GalNAcβ1-4(NeuAcα2-3)Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer |

| 9 | GM1 | Galβ1-3GalNAcβ1-4(NeuAcα2-3)Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer |

| 10 | GD3 | NeuAcα2-8NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer |

| 11 | GD1a | NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-3GalNAcβ1-4(NeuAcα2-3)Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer |

| 12 | GD1b | Galβ1-3GalNAcβ1-4(NeuAcα2-8NeuAcα2-3)Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer |

| 13 | GT1b | NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-3GalNAβ1-4(NeuAcα2-8NeuAcα2-3)Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer |

| 14 | GgO3 (asialo-GM2) | GalNAcβ1-4Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer |

| 15 | GgO4 (asialo-GM1) | Galβ1-3GalNAcβ1-4Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer |

| 16 | Globotriaosylceramide (Gb3; Pk antigen) | Galα1-4Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer |

| 17 | Globoside (Gb4; P antigen) | GalNAcβ1-3Galα1-4Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer |

| 18 | Globopentaosylceramide (Gb5; Forssman) | GalNAcα1-3GalNAcβ1-3Galα1-4Galβ1-4Glcβ1Cer |

| 19 | PE | PE |

Ceramide with hydroxy fatty acid.

Ceramide with non-hydroxy fatty acid.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

A. pleuropneumoniae reference strain 4074 of serotype 1 (with a semirough LPS profile) and reference strain 4226 of serotype 2 (with a smooth LPS profile) were obtained from the National Veterinary Institute, Uppsala, Sweden. Bacterial strains were cultivated on brain heart infusion agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 15 μg of NAD per ml. Inoculated agar plates were incubated overnight at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Extraction and isolation of LPS.

LPS from A. pleuropneumoniae serotypes 1 and 2 was extracted and isolated by the method of Darveau and Hancock (4), with some modifications (27). Briefly, disrupted cells were treated with DNase, RNase, pronase, and sodium dodecyl sulfate and were subjected to MgCl2 precipitation and high-speed centrifugation. These LPS preparations contained less than 1% protein as determined by a dye-binding assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.), and no bands were detected after silver staining of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels.

LPS hydrolysis.

Ten milligrams (dry weight) of LPS was hydrolyzed at 100°C for 2 h in 1 ml of 1% (vol/vol) acetic acid previously saturated with nitrogen. Lipid A (insoluble) and polysaccharides (soluble) were separated by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min after neutralization with 5 N NaOH (25). The polysaccharidic fraction (also referred to as detoxified LPS) was used in the TLC binding assay.

TLC binding assay.

The binding of A. pleuropneumoniae to glycosphingolipids (Table 1) separated on TLC was carried out as described previously (10). TLC were prepared in duplicate, using 4 μg of pure glycosphingolipids. The glycosphingolipids were separated on aluminum-packed silica gel plates (high-performance TLC; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), using chloroform-methanol-water (60:35:8 by volume) as a solvent system. One TLC plate was treated with anisaldehyde as described previously (31). An identical plate was immersed in 0.3% (wt/vol) polyethylmethacrylate (Plexigum P28; Röm, GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) in a mixture of diethylether and n-hexane (3:1 by volume) for 1 min prior to the overlay binding assay. The plates were dried at room temperature (RT) and then incubated in a blocking solution containing 2% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin and 0.1% (wt/vol) Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.01 M KH2PO4, 0.1 M Na2HPO4, 1.37 M NaCl, 0.027 M KCl [pH 7.4]) for 2 h at RT. The chromatograms were then overlaid with either a bacterial suspension resuspended in PBS to an A540 of 1.8, equivalent to approximately 3 × 109 CFU/ml, or extracted LPS resuspended in PBS (2 mg/ml) and incubated for 2 h with gentle agitation. After five washes in PBS to remove unbound bacteria or extracted LPS, the TLC plates were incubated with either rabbit polyclonal antibodies raised against whole cells of A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 or serotype 2 or monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) directed against an epitope in the O chain of LPS of serotype 1 (5.1 G8F10) (20) or serotype 2 (102-G02) (7). After 2 h incubation at RT, the plates were washed three times with PBS, overlaid with goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (heavy plus light chain)-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin IgG (heavy plus light chain)-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and incubated at RT for 1 h. The chromatograms were washed again, and the conjugate-bound peroxidase was developed with 4-chloro-1-naphthol and hydrogen peroxide (Sigma). The plates were then dried at RT in a dark place before the binding activities were evaluated and photographed with an Alpha Imager 2000 (Canberra Packard Canada, Montréal, Québec, Canada). As controls, TLC plates that had not been overlaid with bacterial cells or extracted LPS were incubated with primary and secondary antibodies; these antibodies did not bind directly to the glycosphingolipids.

Inhibition with MAbs.

The bacterial suspensions were preincubated with various dilutions of the MAbs against serotype 1 O antigen (5.1 G8F10) or against serotype 2 O antigen (102-G02) at 37°C with mild agitation for 30 min. The prepared mixtures were used in the overlay assay. The immunostaining and development steps were carried out as described under “TLC binding assay.”

RESULTS

Binding of A. pleuropneumoniae whole cells.

Binding of A. pleuropneumoniae cells of serotype 1 and serotype 2 to various acid and nonacid glycosphingolipids separated on TLC was evaluated. Both serotypes of A. pleuropneumoniae bound to glucosylceramide (GlcCer), galactosylceramide sulfate (sulfatide; SO3-3GalCer), lactosylceramide (LacSer; Galβ4GlcCer), gangliotriaosylceramide (GgO3), and GgO4 (Table 2 and Fig. 1). A. pleuropneumoniae serotypes 1 and 2 bound weakly GalCer, whether the fatty acids were hydroxylated or not. Weak and sporadic binding of serotype 1 strain to sulfatide was detected. Strong binding of both serotypes, manifest by thick and intensely stained bands, to GgO3 and GgO4 on TLC plates was observed. No binding was observed for serotype 1 and serotype 2 whole bacteria to any of the gangliosides, globoseries glycosphingolipids, phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and ceramide (Cer) on TLC.

TABLE 2.

Binding of A. pleuropneumoniae cells and extracted LPS to glycosphingolipids separated on TLC

| Glycolipida | Relative bindingb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serotype 1

|

Serotype 2

|

|||

| Bacteria | LPS | Bacteria | LPS | |

| Cer | − | − | − | − |

| GlcCer | + | + | + | + |

| GalCer type I | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| GalCer type II | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| Sulfatide | ± | ± | + | + |

| LacCer | + | + | + | + |

| GM3 | − | − | − | − |

| GM2 | − | − | − | − |

| GM1 | − | − | − | − |

| GD3 | − | − | − | − |

| GD1a | − | − | − | − |

| GD1b | − | − | − | − |

| GT1b | − | − | − | − |

| GgO3 | ++ | + | ++ | + |

| GgO4 | ++ | + | ++ | + |

| Gb3 | − | − | − | − |

| Gb4 | − | − | − | − |

| Gb5 | − | − | − | − |

| PE | − | − | − | − |

Glycolipid designations are defined in Table 1.

(+), positive binding in about 10% of performed assays; ±, weak binding.

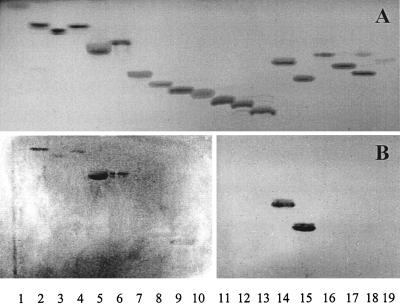

FIG. 1.

TLC after chemical detection with anisaldehyde (A) and immunostained chromatograms obtained by overlay with cells of A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 2 (B). The purified glycosphingolipids were separated on TLC plates by using chloroform-methanol-water (60:35:8 by volume). The lanes contain glycosphingolipids (4 μg) as listed by number in Table 1.

Binding of A. pleuropneumoniae extracted LPS.

Since we have previously identified LPS as the major adhesin of A. pleuropneumoniae, we wished to evaluate this molecule in the TLC binding assay. Extracted LPS of serotypes 1 and 2 bound to the same glycosphingolipids recognized by whole cells (Fig. 2B). Sulfatide was bound sporadically by extracted LPS of serotype 1 as did whole cells of serotype 1. No binding was observed by extracted LPS of both serotypes to gangliosides, globoseries glycosphingolipids, PE, and Cer.

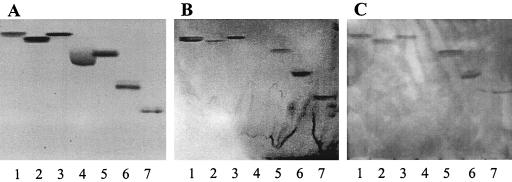

FIG. 2.

TLC showing separated glycosphingolipids stained with anisaldehyde (A) after overlay with A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 extracted LPS (B) or serotype 1 detoxified LPS (C). The following glycosphingolipids (4 μg) were tested: lane 1, GlcCer; lane 2, GalCer type I; lane 3, GalCer type II; lane 4, sulfatide; lane 5, LacCer; lane 6, GgO3; lane 7, GgO4.

To see whether the polysaccharidic fraction of LPS could bind to the glycosphingolipids, detoxified LPS (devoid of lipid A) of A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 was used in the TLC binding assay. The detoxified LPS of A. pleuropneumoniae bound GlcCer and GalCer with and without hydroxylated fatty acids, whereas it weakly recognized the sulfatide (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, the binding patterns of whole bacterial cells, extracted LPS, and detoxified LPS to glycosphingolipids were quite similar.

Inhibition of binding by MAbs specific for LPS O antigen.

The binding of A. pleuropneumoniae to glycosphingolipids on TLC plates was inhibited by O-antigen-specific MAbs (Table 3). After incubation of bacteria with the specific MAbs, both serotypes 1 and 2 failed to recognize GlcCer, GalCer with hydroxy and nonhydroxy fatty acids, sulfatide, and LacCer. Incubation of bacterial strains with MAbs raised against O antigen completely abolished binding to mono- and disaccharide glycosphingolipids, whereas no such effect was shown with GgO3 and GgO4 asialogangliosides. As a negative control, bacterial cells were incubated with MAb against the heterologous serotype; no inhibition of binding to glycosphingolipids was detected.

TABLE 3.

Inhibition of binding of A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 and serotype 2 cells to glycosphingolipids on TLC plates, using MAbs against LPS O-antigen (5.1 G8F10 and 102-G02, respectively)

| Serotype | Binding to glycosphingolipids

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before incubation with MAb

|

After incubation with MAb

|

|||||||||||||

| GlcCer | GalCer type I | GalCer type II | Sulfatide | LacCer | GgO3 | GgO4 | GlcCer | GalCer type I | GalCer type II | Sulfatide | LacCer | GgO3 | GgO4 | |

| 1 | + | ± | ± | (+) | + | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | ++ | ++ |

| 2 | + | ± | ± | + | + | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | ++ | ++ |

±, weak binding; (+), positive binding in about 10% of performed assays.

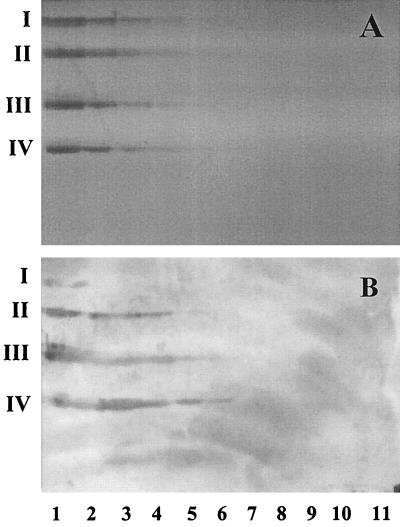

Binding activity and concentration of glycosphingolipid.

The relative binding affinity of GlcCer, LacCer, GgO3, and GgO4 on TLC plates was evaluated (Fig. 3). Different concentrations of these glycosphingolipids (3.75 ng, 7.5 ng, 15 ng, 30 ng, 60 ng, 125 ng, 250 ng, 500 ng, 1 μg, 2 μg, and 4 μg) were separated on TLC plates. The lowest amounts of GlcCer, LacCer, GgO3, and GgO4 which showed visible binding by bacteria were 2 μg, 500 ng, 125 ng, and 125 ng, respectively. The final amount of the glycosphingolipids needed to obtain visible bands, after chemical detection with anisaldehyde, was 250 ng.

FIG. 3.

TLC stained with anisaldehyde (A) and immunostained chromatograms obtained by overlay with A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 2 cells (B). Lanes contain the following concentrations of GlcCer (I), LacCer (II), GgO3 (III), or GgO4 (IV); lane 1, 4 μg; lane 2, 2 μg; lane 3, 1 μg; lane 4, 500 ng; lane 5, 250 ng; lane 6, 125 ng; lane 7, 60 ng; lane 8, 30 ng; lane 9, 15 ng; lane 10, 7.5 ng; lane 11, 3.75 ng.

DISCUSSION

It has been reported by our laboratory that LPS is involved in the binding of A. pleuropneumoniae to porcine respiratory tract cells (1, 25). Interaction between receptors on target tissue and different pathogens, by means of one or more adhesin(s), is the first step in colonization and infection. The successful selection of the specific tissues by bacteria is dependent, among other factors, on the presence or absence of specific receptor(s) for that organism. The majority of described receptors for microbes on host cells are glycoconjugates, which is explained in part by the abundance of these substances at the cell surfaces (15). An in vitro TLC binding assay, described by Karlsson and Strömberg (18), was used to evaluate the binding profile of A. pleuropneumoniae whole cells and LPS to glycosphingolipids.

A. pleuropneumoniae reference strains of serotypes 1 and 2, as well as their extracted LPS, bound to GlcCer, GalCer, LacCer, sulfatide, GgO3, and GgO4 on TLC plates. Interestingly, these glycosphingolipids were bound by whole bacterial cells as well as their extracted LPS. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first reports describing the binding of LPS to glycosphingolipids, including sphingolipids with mono- and disaccharide moieties. Gupta et al. (8) reported that P. aeruginosa whole cells and extracted LPS bound the GgO4 glycosphingolipid on TLC plates, but extracted LPS failed to detect GM1, lactosylceramide, and globoside.

Both serotypes of A. pleuropneumoniae recognized weakly hydroxylated GalCer as well as nonhydroxylated GalCer. It is known that the fatty acid of Cer plays a role on the presentation of the carbohydrates. The sulfatide was also detected by serotype 1 and serotype 2 reference strains, but serotype 1 strains bound this isoreceptor only sporadically. The presence of a sulfate group in sulfatide increased the binding compared to GalCer, which may suggest that the sulfate group is most probably important for this interaction. The sulfatide, isolated from human gastric tissue, was shown to be recognized by Helicobacter pylori, a causative agent of human gastritis (14, 26).

The binding data shown in Fig. 3 indicate that A. pleuropneumoniae recognized less well GlcCer than LacCer glycosphingolipids. The binding of A. pleuropneumoniae to LacCer, which is stronger than that to GalCer of types I and II or GlcCer, clearly indicates that the binding of bacteria to LacCer requires the Galβ1-4Glc sequence. Recognition of internal sequences in various glycosphingolipid as well as binding of LacCer was previously reported for Propionibacterium spp., Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Neisseria subflava whole bacterial cells (17, 28, 29).

To identify the region of LPS involved in binding to glycosphingolipids, detoxified LPS as well as MAbs against LPS O antigen were used. Detoxified LPS (devoid of lipid A) bound to the same glycosphingolipids recognized by extracted LPS, which suggests the involvement of the saccharide moiety of the LPS in the binding. Preincubation of bacteria with the O-antigen specific MAbs resulted in inhibition of binding to mono- and disaccharide glycosphingolipids (GlcCer, GalCer, LacCer, and sulfatide). However, binding to the asialogangliosides was not affected by incubation of bacteria with O-antigen specific MAbs. Therefore, our findings suggest that the polysaccharide moiety (presumably the O antigen) of LPS seems to be involved in binding to GlcCer, GalCer types I and II, sulfatide, and LacCer. The lactose (Galβ1-4Glc) is a core structure present in most acid and nonacid glycosphingolipids. Linkage of a neuraminic acid residue abolished binding of A. pleuropneumoniae and its extracted LPS to LacCer, as demonstrated in Fig. 1. Hence, one may speculate that carbohydrate linkage to Galβ1-4Glc of LacCer abolishes the binding to this receptor. Furthermore, the large difference in binding affinity between LacCer and the asialogangliosides suggest that the binding to these asialogangliosides is not based solely, if at all, on the interaction with the lactose moiety. The structural difference between GgO3 and GgO4 is a Galβ1-3 linkage to GalNAc. However, A. pleuropneumoniae bound with comparable strength to the GgO3 and GgO4, indicating that the minimal binding epitope sequence appears to be the GalNAcβ1-4Gal disaccharide. This observation indicates also that the Galβ1-3 linkage is not part of the binding epitope of GgO4. Taken together, our data from binding of LPS and inhibition of binding by specific MAbs against LPS O antigen of serotypes 1 and 2 suggest that the core region of LPS may represent a conserved binding domain of the LPS adhesin which binds the GalNAcβ1-4Gal sequence found in both GgO3 and GgO4 glycosphingolipids. It was reported that many human pulmonary pathogens recognize the saccharide sequence GalNAcβ1-4Gal in fucosylasialo-GM1, asialo-GM1, and asialo-GM2 glycosphingolipids (19). On the other hand, these pathogens failed to detect GlcCer, GalCer, sulfatide, and LacCer (19), which may indicate that the binding mechanisms developed by A. pleuropneumoniae are advantageous for successful colonization and infection of its host. Inability to bind sialic acid-containing glycosphingolipids by A. pleuropneumoniae or their extracted LPS, despite the presence of the specific GalNAcβ1-4Gal binding sequence, may correlate with different conformational presentation of the binding epitope in a way not accessible for binding by the LPS adhesin. Human pulmonary pathogens also failed to recognize these gangliosides (19). Interestingly, the terminal part of LPS (O side chain) is involved in binding to mono- and disaccharide glycosphingolipids, which are in nature short and therefore close to the cell membrane and poorly accessible.

Multiple-carbohydrate binding specificities have been observed in various microbial pathogens (15). The fact that A. pleuropneumoniae LPS effectively recognized various saccharide sequences found in different glycosphingolipids probably represents an advantage for this pathogen. However, competitive binding studies should help establish the specificity of the interaction between LPS and various glycosphingolipids. The binding of A. pleuropneumoniae LPS to these putative receptors may eventually be used in the development of an effective multivalent antiadhesion reagent containing carbohydrates representing specific receptor binding sequences to eliminate A. pleuropneumoniae infection. Further studies are needed to determine the presence, location, and functionality of these putative receptors in the pig respiratory tract.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (OPG0003428 to M.J.) and from Fonds pour la Formation de Chercheurs et l’Aide à la Recherche (99-ER-0214). We also thank Service de la Coopération Internationale, Ministère de l’Éducation, Gouvernement du Québec, for a short-term fellowship to M.A.-M.

We are grateful to Marcelo Gottschalk (Université de Montréal) for MAbs 5.1 G8F10 and 102-G02.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bélanger M, Dubreuil D, Harel J, Girard C, Jacques M. Role of lipopolysaccharides in adherence of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae to porcine tracheal rings. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3523–3530. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3523-3530.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bélanger M, Dubreuil D, Jacques M. Proteins found within porcine respiratory tract secretions bind lipopolysaccharides of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1994;62:868–873. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.868-873.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bock K, Breimer M E, Bringnole A, Hansson G C, Karlsson K-A, Larson G, Leffler H, Samuelsson B E, Strömberg N, Svanborg Edén C, Thurin J. Specificity of binding of a strain of uropathogenic Escherichia coli to Galα1-4Gal-containing glycosphingolipids. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:8545–8551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darveau R P, Hancock R E. Procedure for isolation of bacterial lipopolysaccharides from both smooth and rough Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Salmonella typhimurium strains. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:831–838. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.2.831-838.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Bentzmann S, Roger P, Dupuit F, Bajolet-Laudinat O, Fuchey C, Plotkowski M C, Puchelle E. Asialo GM1 is a receptor for Pseudomonas aeruginosa adherence to regenerating respiratory epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1582–1588. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1582-1588.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frey J. Virulence in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and RTX toxins. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:257–261. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88939-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giese S B, Stenbaek E, Nielsen R. Identification of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 2 by monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies in latex agglutination tests. Acta Vet Scand. 1993;34:223–225. doi: 10.1186/BF03548215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta S K, Berk R S, Masinick S, Hazlett L D. Pili and lipopolysaccharide of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bind to the glycolipid asialo GM1. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4572–4579. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4572-4579.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haesebrouck F, Chiers K, van Overbeke I, Ducatelle R. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae infections in pigs: the role of virulence factors in pathogenesis and protection. Vet Microbiol. 1997;58:239–249. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(97)00162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansson G C, Karlsson K-A, Larson G, Strömberg N, Thurin J. Carbohydrate-specific adhesion of bacteria to thin layer chromatograms: a rationalized approach to the study of host cell glycolipid receptors. Anal Biochem. 1985;146:158–163. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hitchcock P J, Leive L, Mäkelä P H, Rietschel E T, Strittmatter W, Morrison D C. Lipopolysaccharides nomenclature—past, present, and future. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:699–705. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.3.699-705.1986. . (Minireview.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inzana T J. Virulence properties of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Microb Pathogen. 1991;11:305–316. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacques M. Role of lipooligosaccharides and lipopolysaccharides in bacterial adherence. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:408–410. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)10054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamisago S, Iwamori M, Tai T, Mitamura K, Yazaki Y, Sugano K. Role of sulfatides in adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to gastric cancer cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:624–628. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.624-628.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karlsson K-A. Meaning and therapeutic potential of microbial recognition of host glycoconjugates. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlsson K-A, Abul-Milh M, Andersson C, Ångstrom J, Berström J, Danielsson D, Landergren M, Lanne B, Leonardsson I, Miller-Podraza H, Olsson B-M, Schierbeck B, Teneberg S, Uggla C, Wilhelmsson W T, U, Yang Z. Carbohydrate attachment sites for microbes on animal cells. In: Bock K, Clausen H, editors. Aspects on the possible use of analogs to treat infections. Copenhagen, Denmark: Munksgaard; 1994. pp. 397–409. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karlsson K-A, Abul-Milh M, Ångstrom J, Berström J, Dezfoolian D H, Lanne B, Leonardsson I, Teneberg S. Membrane proximity and internal binding in the microbial recognition of host cell glycolipids: a conceptual discussion. In: Korhonen T, Hovi T, Mäkelä P H, editors. Molecular recognition in host-parasite interactions. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1992. pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlsson K-A, Strömberg N. Overlay and solid-phase analysis of glycolipid receptors for bacteria and viruses. Methods Enzymol. 1987;138:220–232. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)38019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krivian H C, Roberts D D, Ginsburg V. Many pulmonary pathogenic bacteria bind specifically to the carbohydrate sequence GalNacβ1-4Gal found in glycolipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6157–6161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.6157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lairini K, Stenbaek E, Lacouture S, Gottschalk M. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies against Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 1. Vet Microbiol. 1995;46:369–381. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)00139-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindberg A A, Brown J E, Strömberg N, Westling-Ryd M, Schultz J E, Karlsson K-A. Identification of the cabohydrate receptor for Shiga toxin produced by Shigella dysenteriae type 1. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:1779–1785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mittal K R, Higgins R, Lariviere S, Nadeau M. Serological characterization of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae strains isolated from pigs in Québec. Vet Microbiol. 1992;32:135–148. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(92)90101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicolet J. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. In: Leman A D, Straw B E, Mengeling W L, D’Allaire S, Taylor D J, editors. Diseases of swine. 7th ed. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press; 1992. pp. 401–408. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nielsen R. Serological characterization of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae strains and proposal of a new serotype: serotype 12. Acta Vet Scand. 1986;27:453–455. doi: 10.1186/BF03548158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paradis S-, Dubreuil D, Rioux S, Gottschalk M, Jacques M. High-molecular-mass lipopolysaccharides are involved in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae adherence to porcine respiratory tract cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3311–3319. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3311-3319.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saitoh T, Natomi H, Zhao W L, Okuzumi K, Sugano K, Iwamori M, Nagai Y. Identification of glycolipid receptors for Helicobacter pylori by TLC-immunostaining. FEBS Lett. 1991;282:385–387. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80519-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sprott G D, Koval S F, Schnaitman C A. Cell fractionation. In: Gerhardt P, Murray R G E, Wood W A, Krieg N R, editors. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 72–103. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strömberg N, Deal C, Nyberg G, Normark S, So M, Karlsson K-A. Identification of carbohydrate structures that are possible receptors for Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4902–4906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strömberg N, Ryd M, Lindberg A A, Karlsson K-A. Studies on the binding of bacteria to glycolipids. Two species of Propionibacterium apparently recognize separate epitopes on lactose of lactosylceramide. FEBS Lett. 1988;232:193–198. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80415-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tascón R I, Vásquez-Boland J A, Gutiérrez-Martin C B, Rodríguez-Barbosa J I, Rodríguez-Ferri E F. Virulence factors of the swine pathogen Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Microbiologia Sem. 1996;12:171–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waldi D. Sprühreagentien für die Dünnschicht-Chromatographie. In: Stahl E, editor. Dünnschicht-Chromatographie. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1962. pp. 496–515. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weis W, Brown J H, Cusack S, Paulson J C, Skehel J J, Wiley D C. Structure of the influenza virus haemagglutinin complexed with its receptor, sialic acid. Nature. 1988;333:426–431. doi: 10.1038/333426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]