Abstract

We have investigated whether the nonpathogenic gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus xylosus and S. carnosus can display a whole domain of a toxic protein on their surface and if such vectors are suitable for immunization of BALB/c mice. The nucleotide sequence encoding the receptor-binding domain (DTR; amino acids 382 to 535) of diphtheria toxin (DT) was inserted into plasmids pSE′mp18ABPXM and pSPPmABPXM, which were designed to display heterologous proteins on S. xylosus and S. carnosus cell surfaces, respectively. Western blot analysis of the resulting bacterial lysates indicates that DTR is produced by each expression system. However, analysis of rabbit anti-DTR antisera binding to the transformed live bacteria shows that DTR is not displayed on the surface of S. xylosus cells whereas it is efficiently exposed on S. carnosus. A significant anti-DT antibody response was raised in BALB/c mice immunized intraperitoneally with S. carnosus displaying DTR, and the antisera abolished DT cytotoxicity on Vero cells. Thus, only S. carnosus can display a whole domain of a toxic protein and represents a potential vector for humoral vaccination.

The advent of genetic manipulation has allowed the development of nonpathogenic live bacteria as vehicles for antigens (31). The interest in these vectors resides in their potential ability to induce a durable immune response (27), to bypass the use of adjuvants, and to induce a mucosal immune response following oral or nasal administration (16). For safety reasons, the live vector must be nonpathogenic or at least of greatly attenuated pathogenicity. In this context, several types of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, such as Salmonella (29, 30), Mycobacterium (27, 32), Streptococcus (16, 19, 20), and Staphylococcus (10, 18, 21), have been previously engineered to express foreign antigens.

Among these bacterial strains, Staphylococcus xylosus and S. carnosus represent particularly safe and potentially interesting vectors for immunization. These two nonpathogenic strains possess a low level of DNA homology to the pathogenic strain S. aureus and are currently used for applications in meat fermentation (26). Furthermore, they do not produce toxins, hemolysins, protein A, coagulase, or clumping factors (7). Also, two expression systems have recently been developed for the surface display of heterologous proteins on S. xylosus (17, 18) and S. carnosus (25) cells, and the two live vectors were shown to be efficient for protein or protein fragment expression (8, 14, 21).

In the present work, we investigated whether a structurally well-defined domain of a toxic protein could be expressed on the surface of S. xylosus or S. carnosus and if the resulting live vector could trigger, in mice, antitoxin antibodies with neutralizing potency. We focused our work on the diphtheria toxin (DT) fragment from amino acids 382 to 535, called receptor-binding domain (DTR), which mediates the targeting of DT to a cell surface receptor (22). DTR was selected because (i) it is structurally organized as a whole domain in DT (1–3), (ii) it is devoid of any cytotoxicity per se (15), (iii) a large proportion of antibodies able to neutralize DT cytotoxicity are directed against the DTR region (11, 33), and (iv) DTR expressed as a soluble fusion protein is capable of eliciting neutralizing anti-DT antibodies in rabbits (15).

In this report, we describe the insertion of the nucleotide sequence encoding amino acids 382 to 535 of DT in plasmids pSE′mp18ABPXM and pSPPmABPXM, which were developed for surface display of heterologous proteins on S. xylosus and S. carnosus cells, respectively. We examined DTR cell surface expression and investigated the immunogenic properties of S. carnosus displaying DTR in BALB/c mice and the capacity of the resulting antisera to neutralize DT cytotoxicity in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and DNA manipulation.

Escherichia coli MC1061 was used as a host in subcloning the DTR fragment in the S. carnosus expression vector. S. carnosus TM300 and S. xylosus SJ21 were provided by the Centre d’Immunologie Pierre Fabre (CIPF) (Saint Julien en Genevois, France). The expression vectors pSE′mp18ABPXM (17, 18) and pSPPmABPXM (25) were also provided by CIPF.

All DNA manipulations were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (24). Bacteria were grown aerobically in basic broth medium (Difco, Detroit, Mich.). Culture medium was supplemented with ampicillin (200 μg/ml) for selection of pSE′mp18ABPXM or pSPPmABPXM in E. coli or chloramphenicol (10 μg/ml) for selection in Staphylococcus species.

The nucleotide sequence coding for amino acids 382 to 535 of DT, corresponding to the receptor domain of the toxin (DTR), was excised from pCP-DTR (15) by SalI-HindIII enzymatic restriction. The DNA fragment was then inserted in the mp18 multicloning site of pSE′mp18ABPXM by using the SalI and HindIII restriction sites, and the resulting plasmid was called pSE′DTR. From pSE′DTR, a BamHI-XhoI DNA fragment containing DTR was extracted and ligated to a BamHI-XhoI-restricted pSPPmABPXM plasmid, leading to pSPPDTR.

Preparation and transformation of the protoplasts from Staphylococcus cells were carried out by a method adapted from that of Götz (7).

Western blot analysis.

Overnight cultures of Staphylococcus cells were diluted in basic broth medium to give an absorbance of 1 at 600 nm. Diluted cultures (2-ml fractions) were centrifuged for 5 min at 3,900 × g. The cells were then suspended in 150 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 10 mM EDTA, 5 μg of lysostaphin per ml, 500 μg of lysozyme per ml). After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, bacterial lysates were diluted twofold in Laemmli buffer and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on an 8% acrylamide gel. After migration, proteins were electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany). The membrane was first saturated with a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–2% bovine serum albumin solution and then incubated in PBS–0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) containing a mouse polyclonal anti-albumin-binding protein (ABP) antiserum (CIPF) diluted 1/80,000. After being washed with PBST, the membrane was incubated with a goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated to peroxidase (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, Pa.) diluted 1/5,000 in PBST. After the membrane was washed, labeling was assessed by using 20 ml of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) containing 10 mg of diaminobenzidine (Sigma) and 100 μl of 30% H2O2.

Detection of DT fragments on the surface of S. carnosus.

Overnight cultures of S. xylosus containing pSE′DTR and S. carnosus containing pSPPDTR were diluted in culture medium to 2.6 × 108 CFU/ml. Samples were added to a 96-microfilter-well plate (MADV N65; Millipore), at 50 μl per well and incubated in the presence of 50 μl of either an anti-ZZ-DTR rabbit serum or an anti-ZZ-DT168–220 antiserum (15) (final dilution, 1/150). After 2 h at 4°C, the contents of the plates were filtered with the Millipore multiscreen assay system and washed five times with PBS. Goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to peroxidase was then added at a dilution of 1/5,000, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After extensive washing of the mixture with PBS, 250 μl of a 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) substrate solution was added per well. The mixtures were transferred (100 μl per well) to an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay maxisorp plate (Nunc) 30 min later, and the plate was read at 414 nm.

Immunization of mice.

Three groups of four BALB/c mice (IFFA CREDO) were injected intraperitoneally with 3 × 108 CFU of S. carnosus containing pSPPDTR. The mice were reimmunized every 3 or 4 days (nine injections in total [group C]), every 7 days (five injections in total [group B]), or every 14 days (three injections in total [group A]). As a control, four BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally at 14-day intervals with 5 × 108 CFU of S. carnosus containing pSPPmABPXM (three doses in total [group D]). Blood samples were collected 14 days after the last injection.

Determination of anti-DT titer.

Microtiter ELISA plates were coated overnight at 4°C with DT (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.) (0.1 μg/well) diluted in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and subsequently saturated with 200 μl of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4)–0.3% bovine serum albumin per well. The DT-coated plates were washed, serial dilutions of the different antisera were added (100 μl/well), and the mixtures were incubated overnight at 4°C. After extensive washing, a goat anti-mouse IgG antibody conjugated to peroxidase was added (100 μl/well; dilution, 1/5,000), and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After extensive washing, 200 μl of ABTS substrate solution was added per well. The plates were read at 414 nm after 60 min. The titer was defined as the highest serum dilution giving an absorbance of 0.6 above the negative control. As a control, we used mouse preimmune sera.

In vitro neutralization assay.

Vero cells were grown in 250-ml culture flasks (Falcon) at 37°C in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum without β-mercaptoethanol. The cells were grown to confluence and detached from the flasks for experimental seeding by incubation in a 0.02% trypsin–0.05% EDTA solution (Biological Industries). Pooled sera from mice immunized with S. carnosus pSPPDTR or a preimmune serum were diluted 1/10 in a synthetic culture medium (DCCM1; Biological Industries) without calf serum or β-mercaptoethanol. DT was serially diluted in DCCM1 and preincubated overnight at 4°C in 96-well MADV N65 filter plates (Millipore) in the presence of the diluted sera (50 μl per well for DT and antisera). Then 50 μl of a solution containing 3 × 104 Vero cells was added per well. After 3.5 h at 37°C, the medium was removed by filtration with the Millipore multiscreen assay system and the cells were washed and filtered with cold Hanks balanced salt solution (Biological Industries). The cells were further incubated in Leu-deficient minimal essential medium (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) for 1 h at 37°C. The medium was then removed by filtration, and minimal essential medium containing [14C]Leu was added (0.4 μCi/well; C.E.A., Saclay, France). After 2.5 h at 37°C, the medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with Hanks balanced salt solution. The cells were then solubilized with 0.4 M KOH for 10 min. Proteins were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and collected on filters by using a TOMTEC apparatus (Wallac, Turku, Finland). The filters were dried, and [14C]Leu incorporation was measured by liquid scintillation with a 1450 Microbeta counter (Wallac).

RESULTS

Insertion of the sequence coding for the receptor-binding domain of DT in two expression systems.

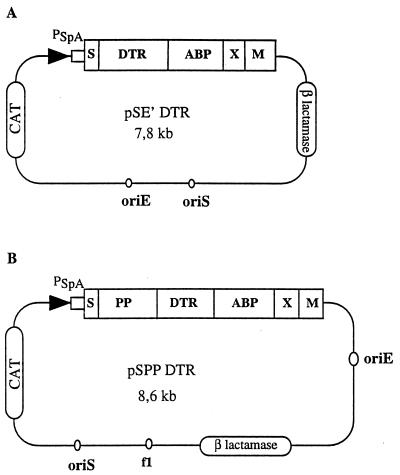

Two expression systems, called pSE′mp18ABPXM and pSPPmABPXM, have been developed for surface display of heterologous proteins by S. xylosus and S. carnosus, respectively (17, 25). The two vectors contain (i) the origin of replication from E. coli and the β-lactamase gene conferring ampicillin resistance (13), (ii) the origin of replication from phage f1, (iii) the origin of replication from S. aureus and the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene for Staphylococcus expression, and (iv) a multicloning site. In both systems, the heterologous polypeptide was inserted in the N-terminal part of a serum albumin-binding region (ABP) of protein G from Streptococcus sp. strain G148 followed by the cell surface-anchoring regions of protein A from S. aureus. In pSE′mp18ABPXM, the recombinant polypeptide was preceded by the promoter region, the signal sequence, and fragment E′ (6 residues) of protein A. In the pSPPmABPXM vector, the inserted sequence was preceded by the promoter region, the signal sequence, and the 207-residue propeptide of a lipase from S. hyicus (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Vectors suitable for surface display on staphylococcal cells of DTR fused to the ABP region of protein G of Streptococcus sp. strain G148. (A) Plasmid used in the S. xylosus strain. (B) Plasmid used in the S. carnosus strain. CAT, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase; X and M, cell-surface anchoring regions of S. aureus protein A; S, fragment E′ (6 residues) of protein A; PP, 207-residue propeptide of a lipase from S. hyicus.

We selected the DTR region for insertion in each expression system. This choice was supported by the previous observation that a soluble fusion protein containing DTR is able to abolish the cytotoxicity of DT for Vero cells and to elicit neutralizing antibodies in rabbits, suggesting that this region, which is organized as a whole domain in DT (1–3), can fold independently in a type of native structure (15).

The sequence coding for DTR was isolated from plasmid pCP-DTR (15) and transferred to pSE′mp18ABPXM. The insertion of this sequence in the resulting pSE′DTR plasmid was then assessed by restriction analysis. S. xylosus was subsequently transformed with the plasmid. To transfer the sequences coding for DTR in the S. carnosus expression vector, a BamHI-XhoI fragment was isolated from pSE′DTR and inserted in pSPPmABPXM. S. carnosus was transformed with the resulting plasmid, called pSPPDTR.

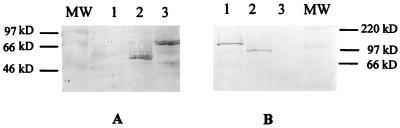

Western blot analysis.

The synthesis of the recombinant proteins was checked by Western blot analysis. Extracts of overnight cultures of Staphylococcus strains containing pSE′mp18ABPXM, pSPPmABPXM, pSE′DTR, pSPPDTR, or no plasmids were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis with ABP-reactive antibodies (Fig. 2). An immunoreactive product was detected in the lysates of S. xylosus and S. carnosus containing either pSE′mp18ABPXM derivative plasmids (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 3) or pSPPmABPXM derivative plasmids (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 and 2) but not in the lysates of the untransformed staphylococci (Fig. 2A, lane 1, and Fig. 2B, lane 3). The estimated sizes of the proteins produced by cells containing pSPPmABPXM and pSE′mp18ABPXM were 89 ± 3 and 50 ± 3 kDa, respectively. For the hybrid proteins, the estimated sizes were 108 ± 3 kDa for pSPPDTR and 66 ± 4 kDa for pSE′DTR. These values indicate that the sequence of DTR (17 kDa) is expressed by the two transformed bacteria.

FIG. 2.

Western blot analysis of bacterial lysates with ABP-reactive antibodies. The bacterial lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE (8% acrylamide) before being blotted onto nitrocellulose. Proteins were detected with goat anti-rabbit IgG coupled to peroxidase and with diaminobenzidine as the chromogenic substrate. Apparent molecular masses are given in kilodaltons. (A) Lanes: 1, S. xylosus; 2, S. xylosus containing pSE′mp18APBXM; 3, S. xylosus containing pSE′DTR. (B) Lanes: 1, S. carnosus containing pSPPDTR; 2, S. carnosus containing pSPPmABPXM; 3, S. carnosus. MW, molecular mass standards.

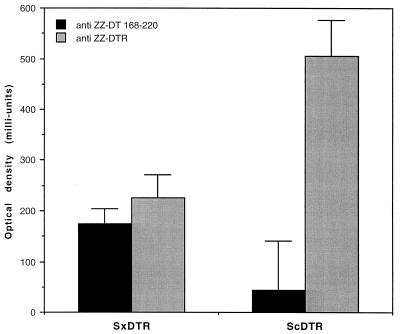

Immunological characterization of the surface display of DTR by S. carnosus and S. xylosus cells.

The display of heterologous proteins on the surface of transformed bacteria can be estimated by investigating the binding of antibodies specific to the inserted proteins (21). We therefore assessed the surface display of DTR by using a rabbit antiserum raised against the soluble fusion protein ZZ-DTR and a second rabbit antiserum raised against the region of DT from residues 168 to 220 (ZZ-DT168–220) (15). The rabbit anti ZZ-DT168–220 antiserum was used as a negative control since it does not recognize DTR (data not shown). The two antisera were incubated with the recombinant bacteria in microfilter plates for 3 h. After extensive washing and filtering, the antibodies still bound to the transformed staphylococci were detected by using a goat anti-rabbit IgG covalently coupled to peroxidase and with ABTS as the substrate.

As shown in Fig. 3, S. carnosus containing pSPPDTR was efficiently recognized by the ZZ-DTR antiserum but was only weakly bound by the ZZ-DT168–220 antiserum. In contrast, the two antisera did not differ significantly in their binding to S. xylosus containing pSE′DTR. Hence, DTR is efficiently displayed on the surface of recombinant S. carnosus but weakly exposed on S. xylosus cells.

FIG. 3.

Surface display of DTR on S. carnosus and S. xylosus cells. S. xylosus containing pSE′DTR (SxDTR) and S. carnosus containing pSPPDTR (ScDTR) were incubated with a ZZ-DT168–220 rabbit antiserum and a ZZ-DTR rabbit antiserum, respectively. After extensive washing and filtering, the antibodies still bound to the transformed staphylococci were detected with a goat anti-rabbit IgG covalently coupled to peroxidase and with ABTS as the substrate.

Immunogenicity of S. carnosus displaying DTR in BALB/c mice.

We investigated the ability of S. carnosus displaying DTR to elicit a humoral immune response in BALB/c mice. Four BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with 3 × 108 CFU of the live recombinant bacteria every 3 or 4 days (group C), every 7 days (group B), or every 14 days (group A). As a control, a fourth group of BALB/c mice was injected with 5 × 108 CFU of S. carnosus containing pSPPmABPXM every 2 weeks. Blood samples were collected 2 weeks after the last injection, and antisera were subsequently tested for their ability to bind to DT on microtiter enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plates. The anti-DT titers measured on pooled antisera were 1/1,000 for group A and the control group, 1/2,000 for group B, and 1/44,000 for group C. An anti-DT antibody response was therefore raised in BALB/c mice only after nine injections, every 3 or 4 days, with 3 × 108 CFU of S. carnosus displaying DTR. The individual variability of the immune response in group C was subsequently examined by measuring anti-DT titers for each individual serum sample. Titers were distributed over a range of 10% around the value measured for the pooled sera (data not shown), indicating that surface display of DTR on S. carnosus cells can trigger a homogeneous immune response in BALB/c mice.

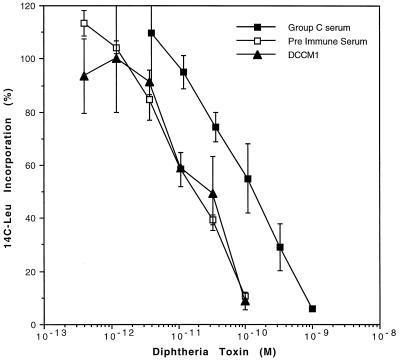

Neutralization of DT cytotoxicity by immune sera.

The neutralizing potency of the antisera raised against recombinant S. carnosus displaying DTR was tested in vitro with toxin-sensitive Vero cells. Various dilutions of DT were preincubated overnight at 4°C with culture medium, a fixed dilution of antisera from group C, or a fixed dilution of preimmune serum. Vero cells were subsequently added to these mixtures, and DT cytotoxicity was estimated by measuring [14C]Leu incorporation into TCA-precipitable material.

As shown in Fig. 4, the preimmune serum did not alter the ability of DT to inhibit the protein synthesis of the Vero cells. In contrast, in the presence of the pooled immune sera from group C mice, approximately 10 times more DT was required to reach a level of inhibition similar to that observed with culture medium only. Therefore, nine intraperitoneal injections of BALB/c mice with 3 × 108 CFU of S. carnosus displaying DTR elicited anti-DT antibodies with in vitro neutralizing potency.

FIG. 4.

In vitro inhibition of DT cytotoxicity by sera from group C mice. Various dilutions of DT were preincubated overnight at 4°C with culture medium, a fixed dilution of the pooled immune serum from group C mice, or a fixed dilution of a preimmune serum. The Vero cells were incubated with these mixtures for 3.5 h at 37°C, and the [14C]Leu incorporation was detected after 2.5 h in the TCA-precipitable fraction.

DISCUSSION

Vaccination with a nonpathogenic bacterium expressing a fragment of a heterologous protein is a promising concept. Numerous heterologous antigens have been tentatively expressed in the cytoplasm (5, 31), in the periplasm (9, 12), or on the cell surface (6, 29) of or secreted by (23) different bacterial strains. In principle, bacterial surface display is particularly suitable for eliciting a humoral immune response because Igs expressing B lymphocytes can bind the heterologous antigen directly. However, the development of this approach is partly limited by the need to display a protein fragment in a structure that resembles the conformation adopted by the same fragment in the cognate protein. In this context, we previously observed that a soluble fusion protein containing the DTR domain is able to abolish efficiently the cytotoxicity of DT for Vero cells and to elicit neutralizing antibodies in rabbits, suggesting that DTR may fold independently in a native type of structure (15). These observations prompted us to investigate whether such a structurally well-defined domain (1–3) may be expressed on the surface of S. xylosus and S. carnosus and if the resulting vectors can trigger, in mice, anti-toxin antibodies with neutralizing potency.

Our results show that the two recombinant bacteria differ markedly in the expression of the DTR domain. DTR was not displayed on the surface of S. xylosus, but it was efficiently produced on S. carnosus. There are various possible explanations for these differences. First, DTR may be translocated efficiently by S. carnosus but only weakly by S. xylosus. This hypothesis is supported by a recent report showing that the expression system developed for S. carnosus is more efficient in its ability to translocate heterologous proteins on the cell surface than is the system developed for S. xylosus (21). Second, the heterologous protein can be degraded by the extracellular protease activity exhibited on the surface of S. xylosus, whereas S. carnosus has been shown to be devoid of such extracellular activity (26). Third, the folding and/or degradation of the DTR domain can be favored or affected by the N-terminal region of the hybrid, which differs in the two expression systems. In S. carnosus, the DTR fragment is preceded by a 209-residue propeptide from lipase, whereas in S. xylosus, this extension is replaced by a 10-residue propeptide from protein A of S. aureus. At present, we cannot determine which of these possibilities applies. However, the weak capacity of S. xylosus to display DTR prompted us to exclude this recombinant vector from our immunization experiments.

The anti-DT antibody titer measured after intraperitoneal injections of BALB/c mice with S. carnosus displaying DTR and the “in vitro” neutralizing capacities of the resulting antisera indicate that this live vector efficiently presents the DTR domain to the immune system. Although these results are promising, it cannot yet be concluded that the live vector is appropriate for heterologous immunizations, because nine injections of high doses of recombinant live bacteria (3 × 108 CFU) were required to raise an efficient anti-DT antibody response. Furthermore, the intraperitoneal route was selected since in preliminary experiments (results not shown) we observed a weak antibody response after subcutaneous injections of BALB/c mice. These observations raised the question of how to increase the immunogenicity of the recombinant bacterium. Since the antibody response is related to the amount of heterologous protein expressed by the live vector (4), one way might be to increase the proportion of DTR displayed on the surface of S. carnosus. Another approach would consist of targeting the recombinant bacterium to appropriate cells of the immune system by using specific antibodies. The latter seems particularly well suited to S. carnosus, since this bacterium has been successfully used for surface display of the single-chain variable fragment of immunoglobulin (ScFv) (8).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge T. N. Nguyen for his advice on the expression of the DT fragments on the surface of staphylococci.

This work was supported by grant BIO2CT-CT920089 from the European Biotechnology Programme, “New approaches for oral vaccination against infectious diseases and autoimmune disorders.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Bennett M J, Choe S, Eisenberg D. Refined structure of dimeric diphtheria toxin at 2.3 Å resolution. Protein Sci. 1994;3:1444–1463. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett M J, Eisenberg D. Refined structure of monomeric diphtheria toxin at 2.3 Å resolution. Protein Sci. 1994;3:1464–1475. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choe S, Bennett M J, Fujii G, Curmi P M G, Kantardjief K A, Collier R J, Eisenberg D. The crystal structure of diphteria toxin. Nature. 1992;357:216–222. doi: 10.1038/357216a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fayolle C, O’Callaghan D, Martineau P, Charbit A, Clément J M, Hofnung M, Leclerc C. Genetic control of antibody responses induced against an antigen delivered by recombinant attenuated Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4310–4319. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4310-4319.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fouts T R, Tuskan R G, Chada S, Hone D, Lewis G. Construction and immunogenicity of Salmonella typhimurium vaccine vectors that express HIV-1 gp120". Vaccine. 1995;13:1697–1705. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00106-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Georgiou G, Stathopoulos C, Daugherty P S, Nayak A R, Iverson B L, Curtiss R. Display of heterologous proteins on the surface of microorganisms: from the screening of combinatorial libraries to live recombinant vaccines. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:29–34. doi: 10.1038/nbt0197-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Götz F. Staphylococcus carnosus: a new host organism for gene cloning and protein production. Soc Appl Bacteriol Symp Ser. 1990;19:49S–53S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb01797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunneriusson E, Samuelson P, Uhlen M, Nygren P A, Stahl S. Surface display of a functional single-chain Fv antibody on staphylococci. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1341–1346. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1341-1346.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haddad D, Liljeqvist S, Kumar S, Hansson M, Stahl S, Perlmann H, Berzins K. Surface display compared to periplasmic expression of a malarial antigen to Salmonella typhimurium and its implication for immunogenicity. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1995;12:175–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansson M, Stahl S, Nguyen T N, Bachi T, Robert A, Binz H, Sjolander A, Uhlen M. Expression of recombinant proteins on the surface of the coagulase-negative bacterium Staphylococcus xylosus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4239–4245. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4239-4245.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayakawa S, Uchida T, Mekada E, Moynihan M R, Okada Y. Monoclonal antibody against diphtheria toxin. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:4311–4317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leclerc C, Martineau P, Van Der Werf S, Deriaud E, Duplay P, Hofnung M. Induction of virus-neutralizing antibodies by bacteria expressing the C3 poliovirus epitope in the periplasm. J Immunol. 1990;144:3174–3182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liebl W, Götz F. Studies on lipase directed export of Escherichia coli β-lactamase in Staphylococcus carnosus. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;204:166–173. doi: 10.1007/BF00330205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liljeqvist S, Samuelson P, Hansson M, Nguyen T N, Binz H, Stahl S. Surface display of the cholera toxin B subunit on Staphylococcus xylosus and Staphylococcus carnosus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2481–2488. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2481-2488.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lobeck K, Drevet P, Léonetti M, Fromen-Romano C, Ducancel F, Lajeunesse E, Lemaire C, Ménez A. Towards a recombinant vaccine against diphtheria toxin. Infect Immun. 1997;66:418–423. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.418-423.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medaglini D, Pozzi G, King T P, Fischetti V. Mucosal and systemic immune responses to a recombinant protein expressed on the surface of the oral commensal bacterium Streptococcus gordonii after oral colonization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6868–6872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen T N, Gourdon M H, Hansson M, Robert A, Samuelson P, Libon C, Andréoni C, Nygren P A, Binz H, Uhlen M, Stahl S. Hydrophobicity engineering to facilitate display of heterologous gene products on Staphylococcus xylosus. J Biotechnol. 1995;42:207–219. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(95)00081-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen T N, Hansson M, Stahl S, Bächi T, Robert A, Domzig W, Binz H, Uhlen M. Cell-surface display of heterologous epitopes on Staphylococcus xylosus as a potential delivery system for oral vaccination. Gene. 1993;128:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90158-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oggioni M R, Manganelli R, Contorni M, Tommasino M, Pozzi G. Immunization of mice by oral colonization with live recombinant commensal streptococci. Vaccine. 1995;13:775–779. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)00060-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pozzi G, Contorni M, Oggioni M R, Manganelli R, Tommasino M, Cavalieri F, Fischetti V A. Delivery and expression of a heterologous antigen on the surface of streptococci. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1902–1907. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.1902-1907.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robert A, Samuelson P, Andreoni C, Bächi T, Uhlen M, Binz H, Nguyen T N, Stahl S. Surface display on staphylococci: a comparative study. FEBS Lett. 1996;390:327–333. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00684-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rolf J M, Gaudin H M, Eidels L. Localization of the diphtheria toxin receptor-binding domain to the carboxyl-terminal Mr approximately 6000 region of the toxin. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:7331–7337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan E T, Butterton J R, Smith R N, Carroll P A, Crean T I, Calderwood S B. Protective immunity against Clostridium difficile toxin A induced by oral immunization with a live attenuated Vibrio cholerae vector strain. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2941–2949. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2941-2949.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samuelson P, Hansson M, Ahlborg N, Andréoni C, Gotz F, Bachi T, Nguyen T N, Binz H, Uhlen M, Stahl S. Cell surface display of recombinant proteins on Staphylococcus carnosus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1470–1476. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.6.1470-1476.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schleifer K H, Fischer U. Description of a new species of the genus Staphylococcus: Staphylococcus carnosus. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1982;32:153–156. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stover C K, Bansal G P, Hanson M S, Burlein J E, Palaszynski S R, Young J F, Koenig S, Young D B, Sadziene A, Barbour A G. Protective immunity elicited by recombinant Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) expressing outer surface protein A lipoprotein: a candidate Lyme disease vaccine. J Exp Med. 1993;178:197–209. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strauss A, Gotz F. In vivo immobilization of enzymatically active polypeptides on the cell surface of Staphylococcus carnosus. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:491–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verma N K, Ziegler H K, Stocker B A D, Schoolnik G K. Induction of a cellular immune response to a defined T-cell epitope as an insert in the flagellin of a live vaccine strain of Salmonella. Vaccine. 1995;13:235–244. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)93308-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker M J, Rohde M, Timmis K N, Guzman C A. Specific lung mucosal and systemic immune responses after oral immunization of mice with Salmonella typhimurium AroA, Salmonella typhi Ty21A, and invasive Escherichia coli expressing recombinant pertussis toxin S1 subunit. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4260–4268. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4260-4268.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wells J, Wilson P, Norton P, Gasson M, Le Page R. Lactococcus lactis: high-level expression of tetanus toxin fragment C and protection against lethal challenge. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:1155–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winter N, Lagranderie M, Gangloff S, Leclerc C, Gheorghiu M, Gicquel B. Recombinant BCG strains expressing the SIV mac251nef gene induce proliferative and CTL responses against nef synthetic peptides in mice. Vaccine. 1995;13:471–478. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)00001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zucker D R, Murphy J R. Monoclonal antibody analysis of diphtheria toxin. I. Localization of epitopes and neutralization of cytotoxicity. Mol Immunol. 1984;21:785–793. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(84)90165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]