Abstract

Background

Screening with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) reduces lung cancer mortality; however, the most effective strategy for optimising participation is unknown. Here we present data from the Yorkshire Lung Screening Trial, including response to invitation, screening eligibility and uptake of community-based LDCT screening.

Methods

Individuals aged 55–80 years, identified from primary care records as having ever smoked, were randomised prior to consent to invitation to telephone lung cancer risk assessment or usual care. The invitation strategy included general practitioner endorsement, pre-invitation and two reminder invitations. After telephone triage, those at higher risk were invited to a Lung Health Check (LHC) with immediate access to a mobile CT scanner.

Results

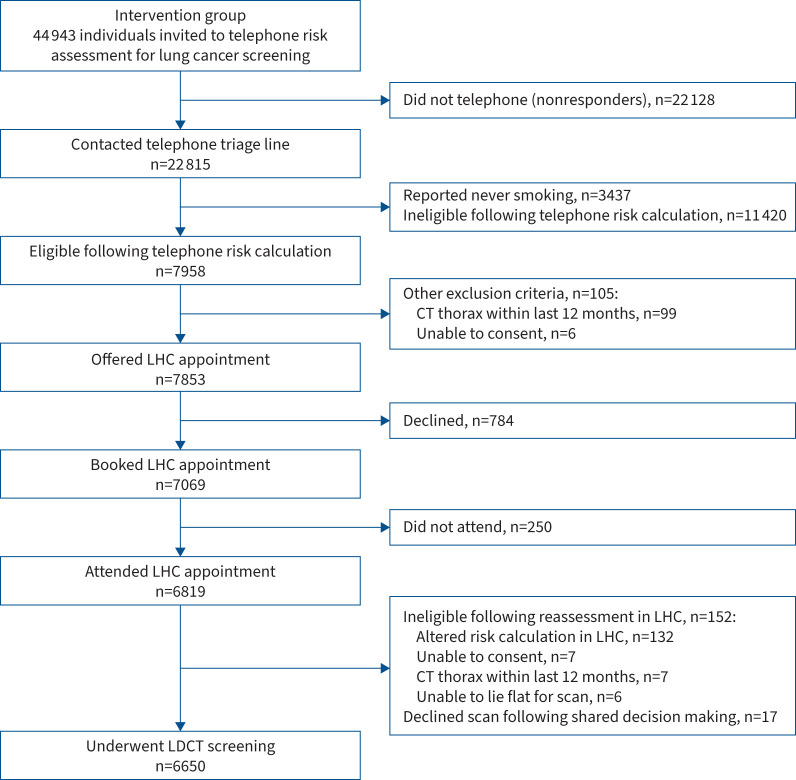

Of 44 943 individuals invited, 50.8% (n=22 815) responded and underwent telephone-based risk assessment (16.7% and 7.3% following first and second reminders, respectively). A lower response rate was associated with current smoking status (adjusted OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.42–0.46) and socioeconomic deprivation (adjusted OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.54–0.62 for the most versus the least deprived quintile). Of those responding, 34.4% (n=7853) were potentially eligible for screening and offered a LHC, of whom 86.8% (n=6819) attended. Lower uptake was associated with current smoking status (adjusted OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.62–0.87) and socioeconomic deprivation (adjusted OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.62–0.98). In total, 6650 individuals had a baseline LDCT scan, representing 99.7% of eligible LHC attendees.

Conclusions

Telephone risk assessment followed by a community-based LHC is an effective strategy for lung cancer screening implementation. However, lower participation associated with current smoking status and socioeconomic deprivation underlines the importance of research to ensure equitable access to screening.

Short abstract

Telephone triage followed by community-based lung cancer screening is an effective model of screening delivery. However, lower participation in people who currently smoke and those from more deprived areas is notable and requires further research. https://bit.ly/38O9z2m

Introduction

Lung cancer outcomes are poor as symptomatic disease is commonly associated with advanced, incurable cancer. Screening with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) dramatically improves outcomes by finding early-stage disease, thereby reducing lung cancer-specific mortality [1, 2]. LDCT screening was approved by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) in 2013, yet only 5% of eligible adults underwent screening in 2018 [3]. As in other developed nations, lung cancer incidence and mortality in the UK are highest in more deprived areas [4], reflecting the link between smoking and low socioeconomic position [5].

People who smoke and those from more deprived communities historically have lower levels of cancer screening participation [6, 7]. Several “barriers” to participation have been identified, including practical issues such as travel or psychological factors which negatively impact a person's motivation to attend [8, 9]. A number of approaches to overcome these “barriers” have been explored in the UK. Examples include Manchester's Lung Health Check (LHC), which took screening directly into highly deprived areas using mobile CT scanners [10, 11], and the Lung Screen Uptake Trial (LSUT) in London, which tested a low-burden, stepped invitation strategy to a hospital-based LHC and demonstrated uptake of 52.6% and reduced social gradient [12].

The UK does not yet have a comprehensive lung cancer screening programme, although a number of pilots have recently commenced [13]. The Yorkshire Lung Screening Trial (YLST) is a large randomised controlled trial of LDCT screening taking place across Leeds in the UK that includes a number of novel design features [14]. First, through permission granted by the UK Health Research Authority, we analysed demographic and clinical data for nonresponders to a written LHC invitation. Second, YLST is one of the first targeted screening programmes worldwide to exclusively use telephone triage to determine screening eligibility. Finally, as in the Manchester LHCs, screening takes place on mobile units located in convenient community locations across Leeds. Here we report the response to telephone triage invitation, screen eligibility and LHC uptake in those at higher risk of lung cancer, including an analysis of factors associated with nonresponse and nonuptake.

Materials and methods

Study design

The design of YLST has been published previously [14]. Primary objectives include participation rates, performance of risk-based eligibility criteria and clinical outcomes of invitation to targeted community-based LDCT screening for lung cancer versus usual care (no invitation). YLST utilises a Zelen design, with residents of Leeds recorded as having ever smoked randomised (1:1) prior to consent to either invitation to a telephone risk assessment and for those at higher risk community-based LHC and LDCT screening, or to no invitation (current usual care in the UK). The unit of randomisation is the household to avoid cohabitees being allocated to different study arms.

Study population

Individuals aged 55–80 years, registered with a participating general practice in Leeds, whose primary care record indicated they had ever smoked were identified as potential study participants. Exclusion criteria included: lung cancer within 5 years, prior metastatic cancer, terminal illness, severe frailty/dementia, nursing home resident or CT thorax within 12 months. General practice data were extracted monthly during the recruitment period (November 2018 and February 2021). Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) was recorded; this is a measure of relative deprivation in small areas of England (based on postcode of residence) ranked from 1 (most deprived) to 32 844 (least deprived).

Study invitation

A general practice-endorsed pre-invitation and invitation letter, alongside a low-burden information leaflet (adapted from the LSUT) [15], was sent to the intervention arm. For the first 2 months of the study, people who had not responded within 2 weeks were sent a reminder letter; from January 2019 onwards two reminder letters were sent to nonresponders. Invitational material was designed to replicate a clinical service and therefore research was not mentioned (until individuals attended the LHC).

Telephone triage

Individuals who contacted the telephone triage service had their screening eligibility checked according to USPSTF 2013 criteria (age 55–80 years, ≥30 pack-years, smoked within 15 years) or lung cancer risk using Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCOm2012) (6-year risk ≥1.51%) and Liverpool Lung Project (LLP) (v2) (5-year risk ≥5%) models [16–18]. If at least one of the three criteria were met, a LHC appointment was offered. The PLCOm2012 model includes height and weight, which participants reported during the telephone call, and ethnicity criteria (White/Black/Asian/Hispanic/Other/Prefer not to say). Those eligible for screening were offered a LHC appointment.

Lung Health Check

The LHC took place in mobile units in 11 community locations (supermarket/retail centre or council car parks) across Leeds. LHCs were run by a research nurse or senior clinical trial assistant, and included measurement of height and weight and re-checking of screening eligibility. The consultation involved a detailed discussion about the benefits and harms of screening. Those who wished to proceed provided fully informed written consent for study participation. Participants completed a LHC questionnaire, clinical parameters were measured (spirometry, oxygen saturation and exhaled carbon monoxide) and immediate opt-out smoking cessation support was offered [19]. A baseline LDCT scan was performed immediately or at a future date, according to participant preference.

COVID-19 pandemic

The study opened in November 2018 but paused due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (March to June 2020). Following appropriate adaptations (pre-visit telephone calls for COVID-19 symptoms, temperature check, appropriate personal protective equipment, information on the trial website (www.leedslunghealthcheck.nhs.uk) and cessation of spirometry), recruitment recommenced July 2020 and completed February 2021.

Analysis

A YLST primary objective is to measure participation in community-based screening. A primary outcome measure is response to telephone triage invitation, defined as the proportion posted an invitation who contacted the telephone triage line. A secondary outcome measure is LHC uptake, defined as the proportion offered a LHC appointment who attended. Simple descriptive analyses are used for response/uptake and characteristics of attendees. General practice codes were used to derive most recent smoking status and ethnicity, which were adapted from UK Government definitions (Office for National Statistics) [20] and primary care research [21]. Factors associated with telephone response and LHC uptake were investigated using univariate and multivariable logistic regression (Stata version 17.0; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The multivariable model was derived by including variables with a p-value <0.20 by univariate analysis and using backwards stepwise selection with a threshold p-value of 0.01 for elimination. Odds ratios are presented with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical tests are two-sided.

Ethical and regulatory framework

The study design was approved by the Health Research Authority following review by Research Advisory Group (18/NW/0012) and the Confidentiality Advisory Group (CAG) (18/CAG/0038). The study was granted a Section 251 exemption in order to process identifiable information from nonconsenting participants.

Results

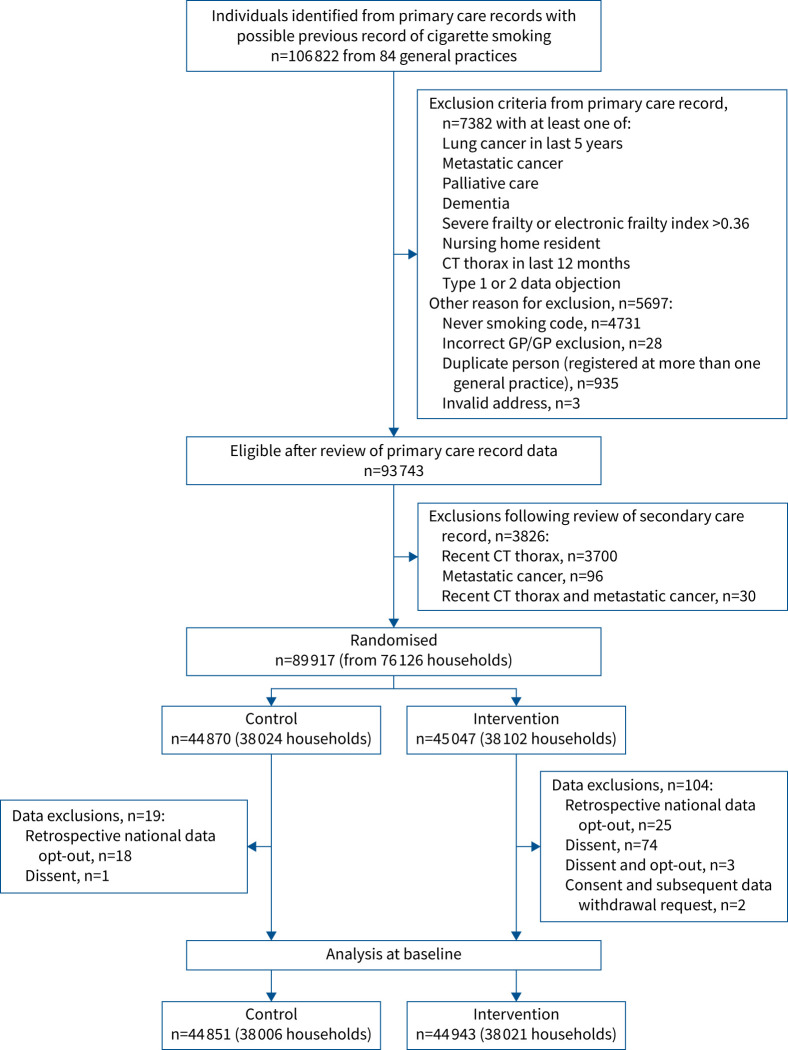

Almost all general practices in Leeds participated in the study (n=84/86 (97.7%)). 44 943 individuals randomised to the intervention arm were included in this analysis (CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) flow diagrams in figures 1 and 2). Most were from single-participant households (69.3% (n=31 157)), 30.3% (n=13 620) were from two-participant households and 0.4% (n=166) were from households with three or more participants. Baseline characteristics are summarised in table 1. Overall, mean age was 66 years, approximately half were male (52.3%) and 30% were in the most deprived IMD quintile. Based on general practice codes, 50.1% were categorised as “White” and 40.8% as “Mixed” ethnicity; 69.1% were categorised as previous smokers and 29.9% as current smokers.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT flow diagram showing extraction of participant information from primary care records, exclusions, randomisation and numbers for final analysis. CT: computed tomography; GP: general practitioner.

FIGURE 2.

CONSORT flow diagram showing outcomes for 44 943 individuals analysed in the intervention group. CT: computed tomography; LHC: Lung Health Check; LDCT: low-dose computed tomography.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of the intervention arm of the Yorkshire Lung Screening Trial stratified by nonresponse or response (contacted telephone triage line) following invitation

| Intervention group | Nonresponders | Responders | p-value | |

| Subjects | 44 943 (100) | 22 128 (49.2) | 22 815 (50.8) | |

| Age, years | 66.1±7.2 | 64.8±7.1 | 67.3±7.1 | |

| Age group, years | <0.001 | |||

| <60 | 11 809 (26.3) | 7244 (32.7) | 4565 (20.0) | |

| 60–64 | 9936 (22.1) | 5329 (24.1) | 4607 (20.2) | |

| 65–69 | 8619 (19.2) | 3745 (16.9) | 4874 (21.4) | |

| 70–74 | 8149 (18.1) | 3317 (15.0) | 4832 (21.2) | |

| ≥75 | 6430 (14.3) | 2493 (11.3) | 3937 (17.3) | |

| Gender | <0.001 | |||

| Female | 21 446 (47.7) | 9969 (45.1) | 11 477 (50.3) | |

| Male | 23 496 (52.3) | 12 158 (54.9) | 11 338 (49.7) | |

| Indeterminate | 1 (<0.1) | 1 (<0.1) | 0 | |

| IMD rank | 15 050 (4014–23 016) |

11 508 (3091–21 681) |

17 272 (6658–23 723) |

<0.001 |

| IMD quintile | <0.001 | |||

| 1 (most deprived) | 13 641 (30.4) | 8102 (36.6) | 5539 (24.3) | |

| 2 | 7184 (16.0) | 3709 (16.8) | 3475 (15.2) | |

| 3 | 7621 (17.0) | 3537 (16.0) | 4084 (17.9) | |

| 4 | 9638 (21.4) | 4012 (18.1) | 5626 (24.7) | |

| 5 (least deprived) | 6811 (15.2) | 2744 (12.4) | 4067 (17.8) | |

| Missing | 48 (0.1) | 24 (0.1) | 24 (0.1) | |

| Ethnicity (derived )# | <0.001 | |||

| White | 22 500 (50.1) | 10 524 (47.6) | 11 958 (52.4) | |

| Black or Black British | 690 (1.5) | 415 (1.9) | 275 (1.2) | |

| Asian or Asian British | 932 (2.1) | 544 (2.5) | 388 (1.7) | |

| Mixed | 18 339 (40.8) | 9102 (41.1) | 9237 (40.5) | |

| Other | 486 (1.1) | 291 (1.3) | 195 (0.9) | |

| Unclear | 357 (0.8) | 190 (0.8) | ||

| Not stated | 1639 (3.7) | 1067 (4.8) | 572 (2.5) | |

| COPD code | 4364 (9.7) | 2219 (10.0) | 2145 (9.4) | 0.16 |

| Smoking status (derived)# | <0.001 | |||

| Currently smoking | 13 435 (29.9) | 8907 (40.3) | 4528 (19.9) | |

| Previously smoked | 31 036 (69.1) | 12 990 (58.7) | 18 046 (79.1) | |

| Never smoked | 13 (<0.1) | 5 (<0.1) | 8 (<0.1) | |

| Noninformative code | 459 (1.0) | 226 (1.0) | 233 (1.02) |

Data are presented as n (%), mean±sd or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise stated. IMD: Index of Multiple Deprivation; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. #: general practice electronic record codes used to derive ethnicity and smoking status.

Response to invitation

Just over half (n=22 815) of invitees contacted the telephone triage service (50.8%, 95% CI 50.3–51.2%) (table 1). Response rate was marginally higher in one-participant households (51.2% (n=15 962/31 157)) compared with households with two or more participants (49.7% (n=6853/13 786)). Response rate was 50% prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (November 2018 to February 2020) and 52.5% when the study reopened with COVID-19 adaptations (July 2020 to February 2021). Analysis of the impact of reminder invitations, undertaken from January 2019 when invitees (n=39 117) received up to two reminder letters, showed that 28% (n=10 971) responded after the initial invitation, 16.7% (n=6520) after a first reminder and 7.3% (n=2845) after a second reminder.

Based on primary care recorded smoking status, response was 33.7% (n=4528/13 435) in people who currently smoke and 58.1% (n=18 046/31 036) in people who used to smoke. Equivalent values were 40.6% (n=5539/13 641) in the most socioeconomically deprived quintile and 59.7% (n=4067/6811) in the least deprived, and 38.7% (n=4565/11 809) and 61.2% (n=3937/6430) in those aged <60 and ≥75 years, respectively. Unadjusted and adjusted analyses are shown in table 2. Response increased with age; those aged ≥75 years were twice as likely to respond compared with those aged <60 years (adjusted OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.87–2.12). After adjustment, the odds of responding were 19% lower in men (adjusted OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.78–0.84), 42% lower in the most deprived IMD quintile compared with the least deprived (adjusted OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.54–0.62) and 56% lower in people categorised as currently smoking (adjusted OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.42–0.46). Asian/Asian British and Mixed ethnicity were associated with lower response compared with White (adjusted OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.68–0.90 and 0.93, 95% CI 0.89–0.97, respectively).

TABLE 2.

Investigation of factors associated with response to the telephone triage line following invitation: univariate and multivariable analyses

| Univariate | Multivariable | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI)# | p-value | |

| Age group, years | ||||

| <60 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 60–64 | 1.37 (1.30–1.45) | <0.001 | 1.31 (1.24–1.39) | <0.001 |

| 65–69 | 2.06 (1.95–2.18) | <0.001 | 1.86 (1.76–1.97) | <0.001 |

| 70–74 | 2.31 (2.18–2.45) | <0.001 | 1.92 (1.81–2.04) | <0.001 |

| ≥75 | 2.50 (2.35–2.67) | <0.001 | 1.99 (1.87–2.12) | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Male | 0.81 (0.78–0.84) | <0.001 | 0.81 (0.78–0.84) | <0.001 |

| IMD quintile | ||||

| 1 (most deprived) | 0.46 (0.43–0.49) | <0.001 | 0.58 (0.54–0.62) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 0.63 (0.59–0.68) | <0.001 | 0.71 (0.66–0.76) | <0.001 |

| 3 | 0.78 (0.73–0.83) | <0.001 | 0.84 (0.78–0.89) | <0.001 |

| 4 | 0.95 (0.89–1.01) | 0.09 | 0.98 (0.92–1.05) | 0.54 |

| 5 (least deprived) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Ethnicity (derived )¶ | ||||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Black or Black British | 0.58 (0.50–0.68) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.79–1.09) | 0.36 |

| Asian or Asian British | 0.63 (0.55–0.72) | <0.001 | 0.79 (0.68–0.90) | 0.001 |

| Mixed | 0.89 (0.86–0.93) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | <0.001 |

| Other | 0.59 (0.49–0.70) | <0.001 | 0.73 (0.61–0.89) | 0.001 |

| Unclear | 1.00 (0.81–1.23) | 0.98 | 1.06 (0.85–1.32) | 0.62 |

| Not stated | 0.47 (0.43–0.52) | <0.001 | 0.52 (0.47–0.58) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status (derived)¶ | ||||

| Previously smoked | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Currently smoking | 0.37 (0.35–0.38) | <0.001 | 0.44 (0.42–0.46) | <0.001 |

| Never smoked | 1.15 (0.38–3.52) | 0.80 | 1.13 (0.36–3.53) | 0.83 |

| Noninformative smoking code | 0.74 (0.62–0.89) | 0.002 | 0.78 (0.65–0.94) | 0.01 |

| COPD | 0.93 (0.87–0.99) | 0.025 | ||

IMD: Index of Multiple Deprivation; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. #: n=44 943; ¶: general practice electronic record codes used to derive ethnicity and smoking status.

Telephone triage outcome

Of 22 815 individuals who contacted the telephone triage line, 34.9% (n=7958) fulfilled the screening eligibility criteria (table 3); 15.1% (n=3437) were ineligible because they self-reported never smoking (despite having a smoking-related code in their general practice record). Baseline data from responders with a self-reported history of ever smoking are summarised in table 3. Self-reported ethnicity was predominantly White (95.3%); this differed from primary care records where 52.4% were recorded as White and 40.5% Mixed.

TABLE 3.

Baseline characteristics of responders who had ever smoked by eligibility for lung cancer screening based on telephone risk assessment

| Responders who had ever smoked | Eligible (high risk) | Ineligible (low risk) | p-value | |

| Subjects | 19 378 (100) | 7958 (41.1) | 11 420 (58.9) | |

| Age group, years | <0.001 | |||

| <60 | 3858 (19.9) | 1129 (14.2) | 2729 (23.9) | |

| 60–64 | 3882 (20.0) | 1333 (16.8) | 2549 (22.3) | |

| 65–69 | 4131 (21.3) | 1727 (21.7) | 2404 (21.1) | |

| 70–74 | 4150 (21.4) | 1922 (24.2) | 2228 (19.5) | |

| ≥75 | 3357 (17.3) | 1847 (23.2) | 1510 (13.2) | |

| Gender | <0.001 | |||

| Female | 9567 (49.37) | 3653 (45.9) | 5914 (51.8) | |

| Male | 9811 (50.63) | 4305 (54.1) | 5506 (48.2) | |

| IMD rank | 17 272 (6658–23 723) |

12 679 (3531–21 819) |

18 918 (8077–25 059) |

<0.001 |

| IMD quintile | <0.001 | |||

| 1 (most deprived) | 4857 (25.1) | 2622 (33.0) | 2235 (19.6) | |

| 2 | 3035 (15.7) | 1396 (17.5) | 1639 (14.4) | |

| 3 | 3479 (18.0) | 1400 (17.6) | 2079 (18.2) | |

| 4 | 4637 (24.0) | 1577 (19.8) | 3060 (26.8) | |

| 5 (least deprived) | 3352 (17.3) | 955 (12.0) | 2397 (21.0) | |

| Missing | 18 (0.09) | 8 (0.1) | 10 (0.1) | |

| Ethnicity (self-report) # | <0.001 | |||

| White | 18 461 (95.3) | 7682 (96.5) | 10 779 (94.4) | |

| Black | 238 (1.2) | 61 (0.8) | 177 (1.6) | |

| Asian | 338 (1.7) | 98 (1.2) | 240 (2.1) | |

| Hispanic | 25 (0.1) | 2 (<0.1) | 23 (0.2) | |

| Other | 217 (1.1) | 76 (1.0) | 141 (1.2) | |

| Prefer not to say | 99 (0.5) | 39 (0.5) | 60 (0.5) | |

| COPD code | 2122 (9.3) | 1826 (23.0) | 296 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status (self-report) # | ||||

| Current smoking | 3427 (17.69) | 2683 (33.7) | 744 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| Previously smoked | 15 951 (82.31) | 5275 (66.3) | 10 676 (93.5) | |

| Pack-years | 17.25 (6–32) | 35 (25.5–45) | 8.5 (3–16.5) | <0.001 |

| Missing | 3437 (15.1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Quit time | 20 (6–37) | 12 (6–21) | 33 (20–42) | <0.001 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| No qualifications (left school age ≤15 years) | 9515 (49.1) | 4896 (61.5) | 4619 (40.5) | |

| O-levels or equivalent | 3944 (20.4) | 1396 (17.5) | 2548 (22.3) | |

| A-levels or equivalent | 845 (4.4) | 234 (2.9) | 611 (5.4) | |

| Some college (not a degree) | 2600 (13.4) | 836 (10.5) | 1764 (15.5) | |

| Graduate | 1595 (8.2) | 408 (5.1) | 1187 (10.4) | |

| Post-graduate | 755 (3.9) | 142 (1.8) | 613 (5.4) | |

| Prefer not to say | 124 (0.6) | 46 (0.6) | 78 (0.7) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Family history of lung cancer | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 2908 (15.0) | 1598 (20.1) | 1310 (11.5) | |

| No | 16 471 (85.0) | 6360 (79.9) | 10 110 (88.5) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| First-degree relative with lung cancer | 0.96 | |||

| Yes | 2802 (96.4) | 1540 (96.4) | 1262 (96.4) | |

| No | 106 (3.7) | 58 (3.6) | 48 (3.7) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| First-degree relatives, n | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 2525 (86.8) | 1357 (84.9) | 1168 (89.2) | |

| 2 | 239 (8.2) | 158 (9.9) | 81 (6.2) | |

| ≥3 | 38 (1.3) | 25 (1.6) | 13 (1.0) | |

| Missing | 106 (3.7) | 58 (3.6) | 48 (3.7) | |

| Age of first-degree relative with lung cancer, years | <0.001 | |||

| <60 | 801 (27.5) | 483 (30.2) | 318 (24.3) | |

| ≥60 | 2001 (68.8) | 1057 (66.1) | 944 (72.1) | |

| Missing | 106 (3.7) | 58 (3.6) | 48 (3.7) |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise stated. IMD: Index of Multiple Deprivation; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. #: self-reported ethnicity and current smoking status collected during telephone triage.

The median (interquartile range (IQR)) telephone call duration was 4.1 (2.6–9.8) min overall, 0.8 (0.5–1.3) min in people who reported never smoking, 3.6 (2.8–4.8) min in people who had ever smoked but were ineligible and 7.5 (5.7–10.1) min in eligible people (table 4). The total duration of telephone calls with responders who were ineligible for screening (n=11 420) was 685 h. Ineligible people who continued to smoke were offered immediate online referral to the local Stop Smoking Service.

TABLE 4.

Duration of telephone triage calls and appointment booking according to self-reported smoking history and risk-assessed eligibility for screening

| Type of call | Call duration (min)# | Calls during baseline round | Calls per day | Total call time during baseline round (min)# | Time for calls per day (min)# |

| Ever smoked eligible¶ | 7.5 (5.7–10.1) | 7954 | 11.5 (5–22) | 64 912 | 91.7 (38.8–182.6) |

| Ever smoked ineligible+ | 3.6 (2.8–4.8) | 11 424 | 14 (6–31) | 46 135 | 64.3 (24.4–120.2) |

| Never smoked+ | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 3437 | 5 (2–9) | 3898 | 5.62 (2.4–11.3) |

| Total | 4.1 (2.6–9.8) | 22 815 | 29 (10–61) | 114 945 | 139.3 (51.6–303.4) |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or n. #: time expressed in minutes with decimal points; ¶: for people who had ever smoked and were eligible for screening, the call time was estimated to be double the time taken to complete the electronic lung cancer risk triage form to allow time for appointment booking on the patient administration system; +: for people who had never smoked, or who had ever smoked but were ineligible for lung screening, the time taken to complete the triage form was taken to be the call duration.

The characteristics of responders stratified by screening eligibility is detailed in table 3. Eligibility increased with age, a self-report of currently smoking (33.7% of eligible compared with 6.5% of ineligible individuals) and greater tobacco smoke exposure. Significant differences in eligibility by gender and IMD were noted, variables not currently included in risk models. The proportion of people who currently smoke eligible for screening was 78.3% (n=2683/3427) compared with 33.1% in those who used to smoke (n=5275/15 951). Of note, 33% of those eligible were in the most socioeconomically deprived quintile compared with 19.6% of those ineligible.

Lung Health Check

Of 7853 individuals offered a LHC appointment, 9.8% (n=784) declined and 3.5% (n=250/7069) did not attend. LHC uptake in those offered an appointment was therefore 86.8% (n=6819/7853). Of 6819 LHC attendees, 152 were found to be ineligible following either re-calculation of risk score (n=132) or another exclusion criteria identified during the face-to-face consultation (n=20). A further 17 declined a CT scan following supported information decision making. This resulted in 6650 people undergoing a baseline LDCT scan, representing 84.7% of those eligible following telephone triage (n=6650/7853) and 99.7% of those eligible following their LHC appointment (n=6650/6667). The median (IQR) time between telephone triage and LHC was 20 (15–29) days.

Characteristics were compared between those attending (n=6819) the LHC appointment and those who either declined or did not attend (n=1034) (table 5). Adjusted analysis demonstrated that nonattendance increased with age (adjusted OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.29–0.48 for those aged ≥75 years compared with <60 years), deprivation (adjusted OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.62–0.98 for the most deprived IMD quintile compared with the least deprived) and self-reported current smoking (adjusted OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.62–0.87) (table 6). Attendance in responders who were eligible and invited to a LHC was higher in men (adjusted OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.16–1.52).

TABLE 5.

Demographic and clinical information for people invited for a Lung Health Check by attendance

| Total invited | Attended | Declined/did not attend | p-value | |

| Subjects | 7853 (100) | 6819 (86.8) | 1034 (13.2) | |

| Age group, years | <0.001 | |||

| <60 | 1121 (14.3) | 1005 (14.7) | 116 (11.2) | |

| 60–64 | 1318 (17.8) | 1165 (17.1) | 153 (14.8) | |

| 65–69 | 1702 (21.7) | 1489 (21.8) | 213 (20.6) | |

| 70–74 | 1899 (24.2) | 1654 (24.3) | 245 (23.7) | |

| ≥75 | 1813 (23.1) | 1506 (22.1) | 307 (29.7) | |

| Gender | <0.001 | |||

| Female | 3606 (45.9) | 3057 (44.8) | 549 (53.1) | |

| Male | 4247 (54.1) | 3762 (55.2) | 485 (46.9) | |

| IMD rank | 12 679 (3531–21 843) |

12 732 (3605–21 860) |

10 212 (3086–20 733) |

0.003 |

| IMD quintile | <0.001 | |||

| 1 (most deprived) | 2587 (32.9) | 2194 (32.2) | 393 (38.0) | |

| 2 | 1379 (17.6) | 1229 (18.0) | 150 (14.51) | |

| 3 | 1385 (17.6) | 1187 (17.4) | 198 (19.2) | |

| 4 | 1555 (19.8) | 1377 (20.2) | 178 (17.2) | |

| 5 (least deprived) | 939 (12.0) | 825 (12.1) | 114 (11.0) | |

| Missing | 8 (0.1) | 6 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Ethnicity# | 0.26 | |||

| White | 7583 (96.6) | 6592 (96.7) | 991 (95.8) | |

| Black | 60 (0.8) | 52 (0.8) | 8 (0.8) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (<0.1) | 1 (<0.1) | 0 | |

| Asian | 94 (1.2) | 82 (1.2) | 12 (1.2) | |

| Other | 76 (1.0) | 63 (0.9) | 13 (1.3) | |

| Prefer not to say | 39 (0.5) | 29 (0.4) | 10 (1.0) | |

| COPD code | 1791 (22.8) | 1508 (22.1) | 283 (27.4) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status# | <0.001 | |||

| Currently smoking | 2652 (33.8) | 2226 (32.6) | 608 (58.8) | |

| Previously smoked | 5201 (66.2) | 4593 (67.4) | 426 (41.2) | |

| Pack-years | 35 (25.5–45) | 35 (26.7–45) | 34 (25–45) | 0.49 |

| Quit time (previously smoked) | 12 (6–21) | 12 (6–21) | 11 (5–20) | 0.16 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise stated. IMD: Index of Multiple Deprivation; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. #: self-reported ethnicity and smoking status.

TABLE 6.

Univariate and multivariable analysis of factors predicting the likelihood of Lung Health Check/screening uptake among those invited

| Univariate | Multivariable | |||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI)# | p-value | |

| Age group, years | ||||

| <60 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 60–64 | 0.88 (0.68–1.13) | 0.32 | 0.82 (0.63–1.06) | 0.12 |

| 65–69 | 0.81 (0.63–1.03) | 0.08 | 0.70 (0.54–0.89) | 0.003 |

| 70–74 | 0.78 (0.62–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.59 (0.46–0.75) | <0.001 |

| ≥75 | 0.57 (0.45–0.71) | <0.001 | 0.38 (0.29–0.48) | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Male | 1.39 (1.22–1.59) | <0.001 | 1.33 (1.16–1.52) | <0.001 |

| IMD quintile | ||||

| 1 (most deprived) | 0.77 (0.62–0.96) | 0.02 | 0.78 (0.62–0.98) | 0.04 |

| 2 | 1.13 (0.87–1.47) | 0.35 | 1.12 (0.86–1.46) | 0.38 |

| 3 | 0.83 (0.65–1.06) | 0.14 | 0.84 (0.66–1.08) | 0.17 |

| 4 | 1.06 (0.83–1.37) | 0.60 | 1.09 (0.84–1.40) | 0.52 |

| 5 (least deprived) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||

| Previously smoked | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Current smoking | 0.69 (0.61–0.79) | <0.001 | 0.73 (0.62–0.87) | <0.001 |

| Quit time | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | <0.001 | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | 0.001 |

| Pack-years | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.49 | ||

| COPD | 1.33 (1.14–1.54) | <0.001 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 1.00 | |||

| Black | 0.98 (0.46–2.06) | 0.95 | ||

| Hispanic¶ | ||||

| Asian | 1.03 (0.56–1.89) | 0.93 | ||

| Other | 0.73 (0.40–1.30) | 0.18 | ||

| Prefer not to say | 0.44 (0.21–0.90) | 0.02 | ||

IMD: Index of Multiple Deprivation. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. #: n=7845; ¶: only two individuals in this group, odds ratio not calculable. Multivariable analysis shows final model after backwards stepwise logistic regression using a p-value threshold of 0.01 for elimination.

Discussion

In this study we assessed the participation of residents in Leeds, aged 55–80 years who had a general practice record of having ever smoked, in a community-based targeted lung cancer screening programme. From a total of 44 943 invitees, 50.8% responded. Of those responding, 34.4% were potentially eligible for screening, 29.9% attended a LHC and 29.1% (n=6650) underwent LDCT screening. We demonstrated a marked difference in response according to primary care-derived smoking status, with odds of responding reduced by 56% in people who currently smoke (adjusted OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.42–0.47). This inequality in participation persisted in those at higher risk and invited to a community-based LHC, with 27% lower screening attendance in those self-reporting current smoking (adjusted OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.62–0.87). A similar pattern was seen for high socioeconomic deprivation, with response 42% lower in the most deprived IMD quintile compared with the least deprived (adjusted OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.54–0.62) and LHC attendance 22% lower (adjusted OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.62–0.98). While older age groups were more likely to respond, they were less likely to attend if offered a LHC.

Our data provide novel insights into those individuals who choose not to respond to a written invitation to a LHC assessment. While consistent with evidence from other cancer screening programmes [12, 22–24], the magnitude of the difference in response is notable for age, deprivation and current smoking status, and the size of the YLST population allows for good precision around estimates. Current smoking status and lower socioeconomic position are associated with higher incidence of lung cancer [25], so our data suggest that the people most at risk seem the least likely to engage with the LHC/screening programme. Future work will investigate how these factors are related to the clinical outcome of lung cancer diagnosis and inequalities relating to stage at diagnosis. The finding of lower response rates in Asian/Asian British and Mixed ethnicity groups is also noteworthy, and underlines the importance of future research to ensure access to screening is equitable irrespective of ethnicity. Ethnic categorisation was closely matched between the two sources (general practice coded and self-reported) for Black and Asian groups (1.2% and 1.7% of respondents, respectively). The proportions categorised as White were markedly different between the two sources (52.4% for general practice data versus 94.4% for self-reported data), which reflected the Mixed ethnicity category in general practice data (40.5%) that was not an option for self-reported data (where the categorisation matched that used in the PLCO risk model).

The overall proportion of people responding to the invitation process (50.8%) was similar to that seen in the LSUT (52.6%) [12] and significantly higher than participation reported in the USA [3]. This may reflect the similar invitation strategy used in the two studies (pre-warning letter, general practice endorsement of invitation, use of a low-burden leaflet and a reminder letter for nonresponders). YLST was the first study to use a second reminder letter and this appeared to augment the overall response rate by 7%. Interestingly, participation rates were not adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which may reflect the fact that LHCs were provided in community locations rather than hospital sites.

Assessing lung cancer risk and screen eligibility by a telephone triage line proved highly effective. Only 2.2% of mobile unit attendees (n=152/6819) were found to be ineligible following reassessment during the face-to-face LHC (often due to differences between estimated and measured height and weight). The telephone calls were generally of short duration (median 4.1 min). For those self-reporting that they had never smoked, or for those who had ever smoked but were ineligible for screening, calls were shorter still (median duration 0.8 and 3.6 min, respectively). There were 11 420 ever-smokers who after telephone assessment were ineligible for screening, equating to a time of 685 h over the course of the study. Services that offer face-to-face risk assessments for all participants generally offer 20-min appointments, which would result in 3807 h for these respondents, a more than 5-fold increase. Although there was no formal process evaluation, the telephone conversations were well received.

One possible downside of telephone triage and subsequent attendance for a face-to-face LHC with LDCT screening is the potential for people to disengage between the telephone call and appointment at the mobile unit. Those people opting not to take up the offer of a face-to-face LHC were more likely to be from deprived populations and currently smoking. Despite a higher rate of response to the telephone triage invitation, women and older people were less likely to attend or take up the offer of a LHC appointment or screening, and further research is needed to investigate underlying reasons.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the study include the high participation rate among general practices within Leeds (84 out of 86 general practices took part in the study) and the high level of completeness of data analysis. Of 89 917 individuals for whom data were extracted from primary care systems, only 123 (0.14%) were excluded from analysis due to either registered dissent or a national NHS data opt-out. The ability to analyse characteristics of those not responding to screening invitation gives valuable insight into this population.

A possible limitation of YLST is that as a research study it may not accurately predict participation rates in a national lung cancer screening programme provided as a routine NHS service. People from lower socioeconomic groups are less likely to participate in research studies and this might have contributed to the differential response reported. To mitigate this (and with approval from the Research Ethics Committee), no contact was made with the control (usual care) population. A full explanation of the research nature of the study was only provided at the time of attendance at the LHC when participants were invited to provide informed written consent for participation in a research study. There was a conscious decision not to advertise the service or undertake community engagement, given that only those people randomised to the intervention group could access this service. It may be that this limited overall participation.

Summary

YLST has shown an encouraging response to invitation to a LHC with lung cancer screening, considerably in excess of the most recently reported participation rates in the USA. This may relate to the use of invitation strategies that have been shown to work in other screening programmes. In addition, the use of a second reminder letter appears to augment the response rate by 7% and may be a useful addition to future programmes. The use of a telephone triage service to identify those fulfilling eligibility criteria for screening was accurate and efficient, and may represent the optimal model of triage for lung cancer screening. Despite the overall encouraging response to invitation, very significant disparities remain, with people who currently smoke and those from more deprived populations much less likely to respond. Thus, people at higher risk of lung cancer appear less inclined to participate in screening. There is therefore an urgent need to address barriers to participation in these populations in order to maximise the lives saved by lung cancer screening and ensure equitable access to services in those most at risk of lung cancer.

Shareable PDF

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of the whole YLST clinical team (Sayyorakhon Alieva, Carol Bisby, Cat Bruckner, Andy Cameron, Richard Cannon, Elly Charles, Suzette Colquhoun, Sam Curtis, Angie Dunne, Melanie Brear, Fazia Fazal, Helen Ford, Alice Forkin, Rita Haligah, Jade McAndrew, Sadia Moyudin, Joseph Peill, Angelika Pelka, Ellie Scott, Sophie Stevenson and Matt Ward), Nazia Ahmed (University of Leeds, Leeds, UK), Ann Cochrane (York Trials Unit, York, UK), Philip Melling (Leeds Teaching Hospitals, Leeds, UK) and David Torgerson (York Trials Unit, York, UK).

Footnotes

The YLST study is registered at the ISRCTN registry with identifier ISRCTN42704678. In order to meet our ethical obligation to responsibly share data generated by clinical trials, YLST operates a transparent data-sharing request process. Anonymous data will be available for request once the study has published the final proposed analyses. Researchers wishing to use the data will need to complete a request for data-sharing form describing a methodologically sound proposal. The form will need to include the objectives, what data are requested, timelines for use, intellectual property and publication rights, data release definition in the contract and participant informed consent, etc. A data-sharing agreement from the sponsor may be required.

Conflict of interest: P.A.J. Crosbie reports consulting fees and stock options from Everest Detection; lecture honoraria from AstraZeneca; designing a questionnaire for Novartis; and designing a study for North West eHealth; outside the submitted work. D. Baldwin reports lecture honoraria from MSD, AstraZeneca, Roche and BMS; outside the submitted work. K.N. Franks reports grants from Yorkshire Cancer Research, AstraZeneca and CRUK/AstraZeneca; consulting fees from AstraZeneca; lecture honoraria and payment for expert testimony from AstraZeneca, Roche and Takeda; advisory board membership with Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS, Lilley and Takeda; outside the submitted work. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Support statement: This work was funded by Yorkshire Cancer Research (award reference L403). From September 2021, P. Alexandris was supported by the Barts Hospital Charity (MRC&U0036). From January 2021, S.L. Quaife was supported by the Barts Hospital Charity (MRC&U0036). P.A.J. Crosbie is supported by the Manchester National Institute for Health Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (IS-BRC-1215-20007). Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 503–513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team . Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fedewa SA, Kazerooni EA, Studts JL, et al. State variation in low-dose computed tomography scanning for lung cancer screening in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 2021; 113: 1044–1052. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iyen-Omofoman B, Hubbard RB, Smith CJ, et al. The distribution of lung cancer across sectors of society in the United Kingdom: a study using national primary care data. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 857. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauld L, Bell K, McCullough L, et al. The effectiveness of NHS smoking cessation services: a systematic review. J Public Health 2010; 32: 71–82. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutton S, Wardle J, Taylor T, et al. Predictors of attendance in the United Kingdom flexible sigmoidoscopy screening trial. J Med Screen 2000; 7: 99–104. doi: 10.1136/jms.7.2.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Wagner C, Baio G, Raine R, et al. Inequalities in participation in an organized national colorectal cancer screening programme: results from the first 2.6 million invitations in England. Int J Epidemiol 2011; 40: 712–718. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali N, Lifford KJ, Carter B, et al. Barriers to uptake among high-risk individuals declining participation in lung cancer screening: a mixed methods analysis of the UK Lung Cancer Screening (UKLS) trial. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e008254. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quaife SL, Waller J, Dickson JL, et al. Psychological targets for lung cancer screening uptake: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. J Thorac Oncol 2021; 16: 2016–2028. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crosbie PA, Balata H, Evison M, et al. Second round results from the Manchester ‘Lung Health Check’ community-based targeted lung cancer screening pilot. Thorax 2019; 74: 700–704. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crosbie PA, Balata H, Evison M, et al. Implementing lung cancer screening: baseline results from a community-based ‘Lung Health Check’ pilot in deprived areas of Manchester. Thorax 2019; 74: 405–409. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-211377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quaife SL, Ruparel M, Dickson JL, et al. Lung Screen Uptake Trial (LSUT): randomized controlled clinical trial testing targeted invitation materials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 201: 965–975. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201905-0946OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NHS England National Cancer Programme . Targeted screening for lung cancer with low radiation dose computed tomography. 2019. www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/targeted-lung-health-checks-standard-protocol-v1.pdf Date last accessed: 24 May 2022.

- 14.Crosbie PA, Gabe R, Simmonds I, et al. Yorkshire Lung Screening Trial (YLST): protocol for a randomised controlled trial to evaluate invitation to community-based low-dose CT screening for lung cancer versus usual care in a targeted population at risk. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e037075. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quaife SL, Ruparel M, Beeken RJ, et al. The Lung Screen Uptake Trial (LSUT): protocol for a randomised controlled demonstration lung cancer screening pilot testing a targeted invitation strategy for high risk and ‘hard-to-reach’ patients. BMC Cancer 2016; 16: 281. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2316-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cassidy A, Myles JP, van Tongeren M, et al. The LLP risk model: an individual risk prediction model for lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2008; 98: 270–276. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moyer VA. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160: 330–338. doi: 10.7326/M13-2771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tammemagi MC, Church TR, Hocking WG, et al. Evaluation of the lung cancer risks at which to screen ever- and never-smokers: screening rules applied to the PLCO and NLST cohorts. PLoS Med 2014; 11: e1001764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray RL, Brain K, Britton J, et al. Yorkshire Enhanced Stop Smoking (YESS) study: a protocol for a randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effect of adding a personalised smoking cessation intervention to a lung cancer screening programme. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e037086. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.UK Government . List of ethnic groups. 2021. www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/style-guide/ethnic-groups Date last accessed: 24 May 2022.

- 21.Mathur R, Hull SA, Badrick E, et al. Cardiovascular multimorbidity: the effect of ethnicity on prevalence and risk factor management. Br J Gen Pract 2011; 61: e262–e270. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X572454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McRonald FE, Yadegarfar G, Baldwin DR, et al. The UK Lung Screen (UKLS): demographic profile of first 88,897 approaches provides recommendations for population screening. Cancer Prev Res 2014; 7: 362–371. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team . Baseline characteristics of participants in the randomized National Lung Screening Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010; 102: 1771–1779. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yousaf-Khan U, Horeweg N, van der Aalst C, et al. Baseline characteristics and mortality outcomes of control group participants and eligible non-responders in the NELSON lung cancer screening study. J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10: 747–753. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cancer Intelligence Team at Cancer Research UK . Lung cancer incidence by deprivation. 2020. www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/lung-cancer/incidence#heading-Four Date last accessed: 24 May 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-00483-2022.Shareable (637.1KB, pdf)