Abstract

Objectives

Moringa oleifera is an herbal galactagogue that is used to increase the volume of breast milk. The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of Moringa oleifera leaves in increasing the volume of breast milk in early postpartum mothers.

Methods

A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial was conducted. Eighty-eight postpartum women were randomized to either the study group receiving oral Moringa oleifera capsules or to the control group receiving oral placebo capsules.

Results

There was no difference in median breast milk volume on the third day of postpartum between the Moringa oleifera leaf group and the control group (73.5 vs 50 ml, p = 0.19). However, the amount of breast milk in the Moringa oleifera group was 47% more than the one in the control group. The exclusive breastfeeding rate at 6 months in this study was 52.3% in the Moringa oleifera group, which met the goals set by the World Health Organization.

Conclusions

Even 900 mg/day of the Moringa oleifera leaf could not significantly increase breast milk volume in early postpartum mothers, but the amount of breast milk in the Moringa oleifera group was 47% more than the one in the control group. The exclusive breastfeeding rate at 6 months in the Moringa oleifera group achieved the goals set by the WHO. Therefore, Moringa oleifera leaf may be used as a galactagogue herb to increase the volume of breast milk.

Keywords: Breast milk volume, Breastfeeding, Moringa oleifera, Postpartum

1. Introduction

Breast milk is the best food for babies. It is safe and clean, and contains antibodies that protect them against common illnesses. It also contains helpful nutrients and energy for babies, especially in the first month of life. Breastfeeding provides physiological and health benefits for both the mother and the baby. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) recommend that the baby be breastfed within the first hour and exclusively for the first 6 months of life. WHO actively promotes breastfeeding as the best source of nourishment for infants and young children, and has set the rate of exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months up to at least 50% by the year 2025 [1].

Adequate volume of breast milk is the key factor for success in exclusive breastfeeding. Various methods have been used to increase the volume of breast milk. The Cochrane database systemic review of 2020 demonstrated that natural milk boosters may improve milk volume and infants' weight, but the review lacks adequate supporting evidence. This, therefore, requires that more thorough studies be carried out to reliably certify the effects of milk boosters [2]. Galactagogue herbs, of which Moringa oleifera is one, have been used by breastfeeding mothers who have breast milk problems to increase the volume of breast milk [3]. Moringa oleifera is widely used in traditional medicine. And the leaves together with the immature seed pods are used as food products [4]. Moringa oleifera leaves increases the volume of breast milk by increasing prolactin and providing essential nutrients [2], [5]. It takes about 24 h after ingestion for the Moringa oleifera to work [6], [7]. Various safety studies were conducted on animals using aqueous leaf extracts and the results indicated that there was a high degree of safety. No adverse effects were reported in human studies [4]. However, few studies have evaluated Moringa oleifera in breastfeeding. One study found that the consumption of Moringa cookies increased the quality of breast milk, especially the amount of protein [8]. Another study found that Moringa oleifera leaves increased the production of breast milk on postpartum days 4 and 5 among mothers who delivered preterm infants [7]. Also, it was discovered in a study that women who took Moringa oleifera capsules had more breast milk per day from postpartum days 3–10 compared to those women who were on placebos. However, this was not statistically significant [6]. Thus, the objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of Moringa oleifera leaves in increasing the volume of breast milk in early postpartum mothers.

2. Materials and methods

This randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial was performed at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand. It is a baby-friendly hospital. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (IRB No. 157/63) and performed in accordance with the approved guidelines of the Research Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This clinical trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Clinical trials registration: NCT04487613). The authors confirmed that all ongoing and related trials for this drug were registered. The complete date range for participant recruitment and follow-up was 1 year and 6 months (November 1, 2020 – April 30, 2022). This study protocol (version 3, dated 4 June 2020) was published in PLoS One 2021 [9].

Pregnant women aged 18 years or more with a gestational age of 37 weeks or more who intended to breastfeed were recruited for the sutdy and consent was obtained before delivery. Randomization was done after delivery. Women with an uncomplicated full-term delivery who had accomplished similar antenatal breastfeeding promotion protocol were included. Postpartum women with contraindication to breastfeeding such as HIV, those on chemotherapeutic drugs, on radioactive substances, those whose babies had galactosemia or needed phototherapy were excluded, as were postpartum women with unstable conditions (i.e., postpartum hemorrhage, sepsis), known allergy to Moringa oleifera, or women with insufficient glandular tissue or who had breast surgery, women with a history of infertility, women with hypothyroidism, women with twins or higher order births, premature infants and infants with sucking problems or structural oral anomalies that can affect sucking (e.g. tongue tie, birth asphyxia, clefts, etc.).

After the study was approved, eligible postpartum women who had given informed consent were consecutive enrolled in the study. All women received the same postpartum care along with breastfeeding support procedures. The research nurses confirmed that all of them correctly nursed their infants. Breastfeeding was initiated immediately after delivery in all the women. They were encouraged to breastfeed their baby as frequently as they desired or whenever the baby became hungry. The babies were fed directly from the breasts and all the women breastfed exclusive. If the baby showed signs of inadequate milk intake, and if supplemental feeds were given, these were controlled for the analysis. The data about supplemental feeds were recorded by asking the women.

The drugs and placebo were prepared before the study by a pharmacist who was not involved in the study. The treatment capsule contained 450 mg of Moringa oleifera leaves. The placebo capsule had no content.

The participants were randomized into two groups: the treatment or placebo groups. A randomization scheme was generated by a random number table using a block-of-four technique. The co-investigator, who had no contact with the participants, generated the allocation sequence before the study. To ensure randomization, each envelope was distributed in sequential numerical order. Both the health care providers and the participants were masked to the treatment assignment.

The nurses enrolled the participants. For each participant who met the inclusion criteria, the nurses selected a sequentially numbered opaque envelope which contained 6 capsules of Moringa oleifera leaf powder or placebo (identical in size, shape, and color). The opaque envelopes were sealed to ensure that the allocation sequence was secure. The treatment group received Moringa oleifera leaves powder (450 mg per capsule) (Ouay Un Osoth, Thailand) and the placebo group received no-drug capsules. All the women took 1 capsule of the Moringa oleifera or placebo 2 times before meal for 3 days. Participants took their first capsule at the first 6 h of birth. Treatment assignment was not revealed until data collection was completed 6 months later. All women were admitted into the postpartum ward and discharged on the fourth day postpartum. Hence, all of them received all their medications. The research nurses captured the measured outcome, and 8 personnel were involved in this study. The dosage of 450 mg Moringa oleifera leaf powder was used in the study due to the recommendation from Thai traditional medicine for galactagogue. This dosage is higher than what was used in previous studies [6], [7].

The primary outcome was the volume of breast milk on the third day postpartum. Secondary outcomes were time to noticeable breast fullness, maternal satisfaction, quality of life, side effects, and exclusive breastfeeding rate at 6 months. The third day was used as the measurement time point because it represented the timing of stage II lactogenesis [6]. The weighing method was used on the third day postpartum (48–72 h). The weighing procedure started 48 h after delivery in all the women. The nurse weighed the infant fully clothed before and after each feeding using an electronic weight scale (Camry ER 7210, accurate to 5 g) for 24 h. Babies were weighed each time they wanted to be fed, even if they wanted the breast every 20 min.

The volume of breast milk was evaluated. The sum of the weight difference in grams was converted into the volume of the breast milk in milliliter (1 g = 1 ml). This method is comparable to the measurement of the volume of the breast milk based on the deuterium oxide dilution technique from a previous study [10], [11], [12].

Time to noticeable breast fullness was defined as the mean time from birth to noticeable breast fullness. The participants were asked if they noticed their breasts were full, which was followed by ‘When did you feel breast fullness?.’.

The participants were asked satisfaction and quality of life questions on postpartum day 7 via a phone interview. Satisfaction answer choices consisted of the following: very satisfied, satisfied, neutral, unsatisfied, and very unsatisfied. Quality of life was assessed by WHOQoL-BREF [13]. Side effects were recorded on postpartum day 3 by an interview and on postpartum day 7 via a phone interview. The exclusive breastfeeding rate and any breastfeeding at 6 months were asked via a phone interview.

The sample size calculation was based upon the findings from a previous study [14]. A two-tailed test was used. The average volume of breast milk on day 3 postpartum was 123.8 ± 84.9 ml. We expected a 30% increase in the volume of the breast milk. With adjustments for a withdrawal rate of 30%, a minimum of 44 women in each group were required to detect a statistical difference (α = 0.05, β = 0.2) between the two groups. Therefore, a total of 88 women were used for this study.

A data monitoring committee (DMC) was not needed in this study due to the short duration of the trial and known minimal risks. Interim analyses were not performed in this trial due to the short duration of recruitment and no potentially serious outcomes. No adverse effects were reported in human studies eventhough the risk, both its types and severity, and the harm were monitored. Side effects (such as constipation, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, heartburn, hypotension, hypoglycemia) and serious adverse effects/reactions both in the mothers and especially vulnerable newborns (such as neonatal hypoglycemia, and hypotension) were monitored. Harm was monitored and reported to the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University. Auditing was performed every 3 months by research nurses who were not involved in the study. Investigators planned to provide care for participants’ healthcare needs that arose as a direct consequence of trial participation and pay compensation to those who suffered harm from it.

2.1. Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS version 22 (SPSS: An IBM Company, New York, USA) was used for statistical analysis. A two-tailed test was used in this study. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess data distribution before statistical analysis. The Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables such as percentage of satisfaction and side effects. An independent t-test was used for parametric continuous variables such as the volume of breast milk. A Mann-Whitney U test was used for nonparametric variables. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis of the trial was conducted by using intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis.

3. Results

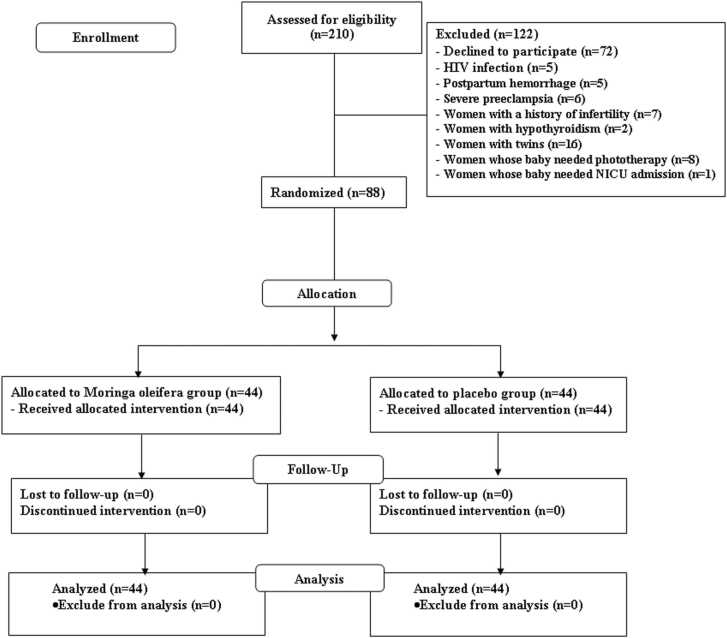

Two hundred and ten women were assessed for eligibility, and 122 were excluded (Fig. 1). Eighty-eight women were enrolled in the study. All the women were randomized into two groups: 44 received Moringa oleifera capsules and 44 received a placebo. All the women completed the study. Baseline characteristics, including maternal age, gravida, parity, body mass index, total weight gain, vital signs, gestational age at the delivery, and route of delivery were similar between the two groups (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Baseline characteristics | Moringa oleifera group (n = 44) |

Placebo group (n = 44) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 32.8 ± 5.7 | 33.18 ± 5.4 | 0.74 |

| Gravida | 0.82 | ||

| Primigravida | 15 (34.1%) | 16 (36.3%) | |

| Multigravida | 29 (65.9%) | 28 (63.6%) | |

| Parity | 0.39 | ||

| Primiparity | 20 (45%) | 24 (54%) | |

| Multiparities | 24 (54%) | 20 (45%) | |

| BMI (kgs/m2) | 23.47 ± 4 | 23.68 ± 4.3 | 0.82 |

| Total weight gain (kgs) | 14.28 ± 5.8 | 12.52 ± 5.6 | 0.15 |

| Vital signs SBP (mmHg) DBP (mmHg) Pulse rate (beats/minute) Body temperature (°C) |

109.54 ± 12.7 64.79 ± 10.1 83.57 ± 13.1 36.87 ± 0.4 |

109.79 ± 21.4 64.39 ± 8.8 83.18 ± 12.4 36.89 ± 0.5 |

0.95 0.84 0.89 0.32 |

| GA at delivery (weeks) | 38.64 ± 1.1 | 38.54 ± 0.9 | 0.62 |

Route of delivery

|

2 (5%) 42 (95%) |

4 (10%) 40 (90%) |

0.39 |

| Labor medication | |||

|

41 (93%) 41 (93%) 2 (4.5%) |

40 (90%) 40 (90%) 3 (6.8%) |

0.82 0.12 0.27 |

| Amount of intravenous fluid (ml) | 3000 | 3000 | NA |

| Baby gender Male Female |

22 (50%) 22 (50%) |

20 (45%) 24 (55%) |

0.67 |

| Birth weight (grams) | 3143.2 ± 467.5 | 3180.2 ± 382.2 | 0.69 |

| APGAR score at 1 min | 8.98 ± 0.1 | 8.86 ± 0.5 | 0.16 |

| APGAR score at 5 min | 9.95 ± 0.2 | 9.91 ± 0.3 | 0.40 |

| Supplemental feeds | 14 (31.8%) | 20 (45.5%) | 0.19 |

Do you think you got the placebo or the intervention?

|

22 (50%) 22 (50%) |

25 (56.8%) 19 (43.2%) |

0.27 |

Data presented as mean + SD, n (%) or median (interquartile range)

BMI: body mass index, SBP: systolic blood pressure, DBP: diastolic blood pressure, GA: gestational age

The amount of breast milk volume on the third day postpartum was not different in the Moringa oleifera and the placebo groups (median 73.5 ml vs 50 ml, p = 0.19) (Table 2). However, the amount of breast milk in the Moringa oleifera group was 47% more than the one in the control group.

Table 2.

Breast milk volume, satisfaction, quality of life and side effects.

| Result | Moringa oleifera group (n = 44) |

Placebo group (n = 44) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast milk volume (ml) | |||

| Day 3 | 73.5 (35.7–138.7) | 50 (26.3–126.5) | 0.19 |

| Participants noticed their breasts were full | 41 (93.2%) | 37 (84.1%) | 0.18 |

| When did participants feel breast fullness? (hours after delivery) | 52.5 (47–65) | 54 (42–69.7) | 0.18 |

| Satisfaction | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–5) | 0.83 |

| Quality of life | 49.9 ± 6.3 | 48 ± 5.3 | 0.12 |

Side effect

|

0 2 (4.5%) 0 0 1 (2.3%) 0 0 0 1 (2.3%) 0 |

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 |

NA 0.15 NA NA 0.31 NA NA NA 0.32 NA |

| Exclusive breast feeding at 6 months postpartum | 23 (52.3%) | 20 (45.5%) | 0.52 |

Data presented as mean + SD or n (%) or median (interquartile range)

About the secondary outcomes, which included time to noticeable breast fullness, maternal satisfaction, quality of life, and exclusive breastfeeding rate at 6 months, the results were not different between two groups. However, the exclusive breastfeeding rate at 6 months in the Moringa oleifera group met the goals set by the WHO (the rate of exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months up to at least 50% by the year 2025); it did not meet the goals in the placebo group.

In terms of side effects, none were detected among participants and newborns in both groups.

4. Discussion

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the efficacy of the Moringa oleifera leaf capsule to increase breast milk volume in early postpartum patients (day 3 postpartum). The result showed that the amounts of breast milk in the Moringa oleifera group and control group were not significantly different. Even Moringa oleifera leaf could not significantly increase the amount of breast milk on the third day postpartum, but the amount of breast milk in the Moringa oleifera group was 47% more than what was in the control group.

The result of this study was different from the previous study by Estrella et al. [7]. They found that Moringa oleifera leaves increased breast milk volume on postpartum days 4 and 5 in mothers of preterm infants. This difference might be due to the different ethnic groups and gestational age at delivery of the newborn. The participants in our study were Thai women who delivered their babies at the mean gestational age of 38 weeks, while in the study by Estrella et al., they were Filipino women whose babies were delivered at the gestational age of 33 weeks.

The result of this study was similar to the previous study by Espinosa-Kuo [6], which found that women who took Moringa oleifera capsules had more breast milk per day from postpartum day 3–10 compared to those who were on placebo. But this was not statistically significant. However, one recent review article mentioned 500 mg/day of Moringa associate with increase breast milk [15].

The exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months in this study was 52.3% in the Moringa oleifera group. This exclusive breastfeeding rate met the goals set by the WHO (the rate of exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months up to at least 50% by the year 2025) [1]. Moringa oleifera may be used for supporting women who intend to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months.

The strengths of this study were its study design, which was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted to evaluate the efficacy of the Moringa oleifera capsule in increasing breast milk volume in the early postpartum period. There was no dropout in our study.

The limitations of this study were the proportion of route of delivery among participants which was mostly cesarean delivery. This might not represent all postpartum patients. We only recorded the amount of breast milk on the third day postpartum which might not represent the whole breast milk production period. Thus, this study does not represent the efficacy of the Moringa oleifera capsule in increasing the amount of the breast milk during the whole breastfeeding period; hence further study is necessitated. Further research should be conducted to include day 3/4/5 of quantification of breast milk amount in comparison to placebo group and the long-term adverse effects to confirm the clinical benefits of Moringa oleifera in breastfeeding.

5. Conclusions

Even 900 mg/day of the Moringa oleifera leaf could not significantly increase breast milk volume in early postpartum mothers, but the amount of breast milk in the Moringa oleifera group was 47% more than the one in the control group. The exclusive breastfeeding rate at 6 months in the Moringa oleifera group achieved the goals set by the WHO. As a result, Moringa oleifera leaf may be used as a galactagogue herb to increase the volume of breast milk.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The work was funded by a Grant for International Research Integration: Research Pyramid, Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund, Chulalongkorn University and Placental related diseases Research Unit, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Document Production Service: Geneva, Switzerland; 2017. [PubMed]

- 2.Foong S.C., Tan M.L., Foong W.C., Marasco L.A., Ho J.J., Ong J.H. Oral galactagogues (natural therapies or drugs) for increasing breast milk production in mothers of non-hospitalised term infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011505.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Othman N., Lamin R.A.C., Othman C.N. Exploring behavior on the herbal galactagogue usage among Malay lactating mothers in Malaysia. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci. 2014;153:199–208. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stohs S.J., Hartman M.J. Review of the Safety and Efficacy of Moringa oleifera. Phytother Res. 2015;29:796–804. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King J., Raguindin P., Dans L. Moringa oleifera as galactagogue for breastfeeding mothers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. Philos J Pedia. 2013;61:34–42. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espinosa-Kuo C.L. A randomized controlled trial on the use of malunggay (Moringa oleifera) for augmentation of the volume of breastmilk among mothers of term infants. Filip Fam Physician. 2005;43:26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estrella C.P., Man taring J.B.V., III, David G.Z., Taup M.A. A double-blind, randomized controlled trial on the use of malunggay (Moringa oleifera) for augmentation of the volume ofbreastmilk among non-nursing mothers of preterm infants. Philos J Pedia. 2000;49:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sumarni Puspasari I., Mallongi A., Yane E., Sekarani A. Effect of Moringa oleifera cookies to improve quality of breastmilk. Enferm Clínica. 2020;30:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fungtammasan S., Phupong V. The effect of Moringa oleifera capsule in increasing breastmilk volume in early postpartum patients: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Plos One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boss M., Gardner H., Hartmann P. Normal Human Lactation: closing the gap. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14452.1. Faculty Rev-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butte N.F., Wong W.W., Patterson B.W., Garza C., Klein P.D. Human-milk intake measured by administration of deuterium oxide to the mother: a comparison with the test-weighing technique. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;47:815–821. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/47.5.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kent J.C., Gardner H., Lai C.T., Hartmann P.E., Murray K., Rea A., et al. Hourly breast expression to estimate the rate of synthesis of milk and fat. Nutrients. 2018;10:1144. doi: 10.3390/nu10091144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahin K., Mojgan M., Fatemeh R., Nasrin G. Quality of life predictors in breastfeeding mothers referred to health centers in Iran. Int J Women'S Health Reprod Sci. 2018;6:84–89. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paritakul P., Ruangrongmorakot K., Laosooksathit W., Suksamarnwong M., Puapornpong P. The effect of ginger on breast milk volume in the early postpartum period: a randomized, double-blind controlled trial. Breast Med. 2016;11:361–365. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2016.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brar S., Haugh C., Robertson N., Owuor P.M., Waterman C., Fuchs G.J., 3rd, et al. The impact of Moringa oleifera leaf supplementation on human and animal nutrition, growth, and milk production: A systematic review. Phytother Res. 2022;36:1600–1615. doi: 10.1002/ptr.7415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]