Abstract

Introduction

Although remarkable progress has been made in osteoporosis treatment over the last two decades, no study has reported the change in the prevalence of vertebral fractures (VFs) during this time. This study aimed to compare the prevalence and pattern of VFs at three time points from 1997 to 2019 in a Japanese medical examination-based study.

Materials and methods

The participants of this study were inhabitants of a typical Japanese mountain village who participated in these surveys at three time points: 1997 (group A), 2009 or 2011 (group B), and 2019 (group C). The age- and sex-adjusted groups were defined as groups A’, B’, and C’, respectively (39 men and 85 women; mean age 73.6–74.0 years old). The type and extent of deformities of the prevalent fractures from T4 to L4 on the lateral thoracic and lumbar spine radiographs were semiquantitatively evaluated.

Results

The prevalence of VFs has significantly decreased over the past two decades. In group A, the percentages of thoracic level, biconcave type, and severe deformity of VFs were significantly higher than expected. The bone mineral density of the participants increased significantly over time. The treatment rate for osteoporosis in participants with osteoporosis has improved over the past two decades.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the prevalence of VFs has decreased, and the pattern of VFs has changed over the last two decades in a typical Japanese mountain village due to multifactorial improvements in skeletal fragility, including improvement in osteoporosis treatment rate.

Keywords: Vertebral fracture, Prevalent vertebral fracture, Morphometric fracture, Bone mineral density

Introduction

Vertebral fracture (VF) is the most common osteoporotic fracture [1] and is associated with decreased activities of daily living, quality of life, and increased mortality rate [2–4]. The prevalence of osteoporosis continues to escalate with the aging global population [5]. Aging has become a significant global issue, especially in Japan. Japan's aging rate (the ratio of the population aged ≥ 65 years among the total population) has exceeded 20%, ahead of any other country, and the percentage of the older adult population (aged ≥ 65 years) has reached 25% in 2013; it is expected to exceed 30% in 2025 and reach 39.9% in 2060 [6]. Since the watershed in osteoporosis drug development around the year 2000, the treatment of osteoporosis has made remarkable progress from calcium and vitamin D supplementation to bisphosphonates or selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), followed by teriparatide, denosumab, and romosozumab [7]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports evaluating longitudinal changes in the prevalence of VFs since 2000.

This study aimed to investigate the longitudinal changes in the prevalence and characteristics of VFs among the three time points from the past two decades (from 1997 to 2019).

Materials and methods

Data were analyzed from a population-based longitudinal prospective study of osteoporosis, knee osteoarthritis (OA), VFs, and disk degeneration in a typical mountain village, Ohdai-cho, in the central Mie Prefecture, Japan [2, 8, 9]. This study was conducted with the approval of the institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent before enrollment in the study.

Participants

Since 1997, the inhabitants of a typical mountain village who were 61 years or older have undergone medical examination every two years. Of these inhabitants in 1997 (210 men and 419 women), 2009 (or 2011) (174 men and 356 women) and 2019 (73 men and 197 women), those who underwent the next medical examination held two year later were included in this study and classified into Groups A (65 men and 141 women, mean age: 72.1 years), B (49 men and 106 women, mean age: 75.8 years) and C (73 men and 197, mean age: 73.9 years), respectively (Table. 1). The medical examination in 2021 was not held due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The number of participants in all these groups accounted for approximately 5% of the population of the village. Participants whose lateral radiographs were unclear due to scoliosis, severe degenerative changes, severe obesity, spinal implantation or any other reason were excluded from this study. To adjust the number, age, and sex of the included participants, 124 inhabitants (39 men and 85 women) were randomly picked from groups A, B, and C and formed into groups A’, B’, and C’, respectively (mean ages: 73.6, 74.0, and 74.1 years, respectively). Random sampling and allocation were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 (IBM Japan, Tokyo).

Table 1.

Age and sex distribution of each group

| a: Age and sex distribution of all the participants who underwent the medical examination | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | 1997 | 2009 (2011) | 2019 | |||||||||

| Age | 61–70 | 71–80 | 81– | Total | 61–70 | 71–80 | 81– | Total | 61–70 | 71–80 | 81– | Total |

| Men | 84 | 96 | 30 | 210 | 19 | 82 | 45 | 146 | 24 | 38 | 11 | 73 |

| Women | 166 | 188 | 59 | 413 | 81 | 183 | 90 | 354 | 65 | 96 | 36 | 197 |

| b: Age and sex distribution of the group A, B and C | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Group A | Group B | Group C | |||||||||

| Age | 61–70 | 71–80 | 81– | Total | 61–70 | 71–80 | 81– | Total | 61–70 | 71–80 | 81– | Total |

| Men | 27 | 32 | 6 | 65 | 8 | 28 | 13 | 49 | 24 | 38 | 11 | 73 |

| Women | 60 | 74 | 7 | 141 | 26 | 56 | 24 | 106 | 65 | 96 | 36 | 197 |

| c: Age and sex distribution after age-sex adjustment among the groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Group A’, B’ and C’ | |||

| Age | 61–70 | 71–80 | 81– | Total |

| Men | 7 | 26 | 6 | 39 |

| Women | 23 | 55 | 7 | 85 |

Clinical interview and physical examination

The participants completed an interviewer-administered questionnaire that included information on age, sex, medical history, hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), and treatment for osteoporosis. The bone mineral density (BMD) of the forearm was measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DCS-600EX, Aloka, Tokyo).

Radiographic assessment of VFs

Lateral thoracic and lumbar spine radiographs of each participant were obtained during each medical examination. The type (wedge, biconcave, or crush) and extent (G1: mild; G2: moderate; G3: severe) of VFs from T4 to L4 at the examination were evaluated using Genant’s semiquantitative technique [10]. Briefly, the type of deformity was defined as the wedge (the collapse of the anterior vertebral body), biconcave (the collapse of the central portion of both vertebral body endplates), or crush (the collapse of the posterior vertebral body) types. The extent of the deformity was defined as G1 (the collapse of approximately 20–25% of the vertebral body), G2 (the collapse of approximately 25–40% of the vertebral body), and G3 (the collapse of more than 40% of the vertebral body). Vertebral levels were divided into three groups: thoracic (T4–T10), thoracolumbar (T11–L2), and lumbar (L3–L4). All radiographs were evaluated by a certified orthopedic surgeon, who was blinded to the classification groups used in this study. To assess the intra- and inter-observer reliability of SQ grading, 37 randomly isolated radiographs were assessed by the same evaluator (J.Y.) again after 2 weeks and by another spine surgeon (N.T.) who was also blinded to the SQ grading results. The percentages of intra- and inter-observer reliability agreement were 97.7% and 97.1%, respectively, and the kappa statistics for these were 0.77 and 0.72, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence, extent, vertebral level, and deformity type of VFs and osteoporosis treatment rates in all groups were statistically evaluated using the Chi-square test. A post hoc test was performed to assess the probability values for each combination of independent category levels using a Bonferroni correction to control for type I error inflation [11]. Statistical analyses of age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and T-score of BMD were performed with a one-way analysis of variance using Fisher’s least significant difference as a post hoc test. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Background data of the participants

There was no significant difference in age and sex among the three groups due to age and sex adjustment (Table 2). However, there were significant difference in height and weight between the groups (P < 0.01), with those in group A’ having significantly lower levels of the same than those in groups B’ and C’ (P < 0.01, respectively), whereas BMI did not reach significance. BMD showed a significant difference among the groups (P < 0.05) and an increasing trend over the two decades. A post hoc test showed that the BMD of group C’ was significantly higher than that of group A’ (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in the prevalence of HTN, DM, or osteoporosis among the groups. The smoking rate decreased over time. It was significantly higher in group A’ (20.2%) and significantly lower in group C’ (3.3%) than expected (P < 0.01).

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants in each group

| Group A’ | Group B’ | Group C’ | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 73.7 ± 0.5 | 74.0 ± 0.5 | 74.1 ± 0.6 | 0.86 |

| Height | 149.0 ± 0.7 | 153.5 ± 0.6** | 154.9 ± 0.8** | < 0.01 |

| Weight | 51.9 ± 0.7 | 55.7 ± 0.8** | 54.8 ± 0.9** | < 0.01 |

| BMI | 23.3 ± 0.3 | 23.6 ± 0.3 | 22.7 ± 0.3 | 0.09 |

| BMD (YAM%) | 76.6 ± 1.4 | 80.0 ± 1.2 | 80.8 ± 1.2† | < 0.05 |

| HTN (%) | 65 (52.4%) | 58 (46.8%) | 64 (51.6%) | 0.63 |

| DM (%) | 8 (6.5%) | 12 (9.7%) | 17 (13.7%) | 0.16 |

| Osteoporosis treatment (%) | 14 (11.3%) | 21 (16.9%) | 26 (22.0%) | 0.08 |

| Smoking (%) | 25 (20.2%) | 14 (11.4%) | 4 (3.3%) | < 0.01 |

Data on age, height, weight, BMI, and BMD are shown as mean ± standard error. Data on HTN, DM, osteoporosis treatment, and smoking are shown as the number (percentage) of participants

BMI body mass index, BMD bone mineral density, YAM% percentage young adult mean, HTN hypertension, DM diabetes mellitus

**Significantly higher compared to group A’ (P < 0.01)

†Significantly higher compared to group A’ (P < 0.05)

Prevalence of VFs

The prevalence of participants who had VFs in groups A’ (71.0%, 88 participants), B’ (46.0%, 57 participants), and C’ (32.3%, 40 participants) showed a decreasing trend and differed significantly among the three groups (P < 0.01; Fig. 1a). The post hoc test showed a significantly higher percentage than expected in group A’ and a significantly lower percentage than expected in group C’ (P < 0.01). This trend was observed in both men and women (Fig. 1b). In participants in their 60 s and 70 s, the percentage of participants with prevalent VFs showed a decreasing trend with significant differences among the groups (P < 0.01, Fig. 1c). A post hoc test revealed a significantly higher percentage in group A’ and a significantly lower percentage in group C’ than expected. In participants in their 80 s, while the prevalence of VFs showed a decreasing trend and differed significantly among the three groups (P < 0.05), the post hoc test did not show any significance.

Fig. 1.

Change in prevalence of vertebral fractures (a) as well as sex (b) and age distribution (c) of prevalent VFs. Data are shown as the percentage (number) of participants with vertebral fractures. *Significantly higher than expected (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). †Significantly lower than expected (†P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01)

The percentage of participants with G1 VFs differed significantly among the three groups (group A’: 65.3%, 81 participants, B’: 39.5%, 49 participants, and C’: 29.8%, 37 participants; P < 0.01). A post hoc test showed that this was significantly higher than expected in group A’ (P < 0.01) and was significantly lower than expected in group C’ (P < 0.01).

The percentage of participants with G2 and G3 VFs differed significantly among the three groups (group A’: 23.4%, 29 participants, B’: 11.3%, 14 participants, and C’: 11.3%, 13 participants; P < 0.01). A significantly higher percentage than expected was found in group A’ (P < 0.05).

Characteristics of VFs

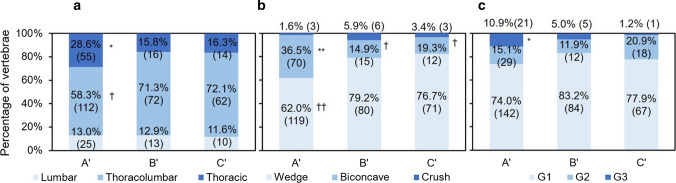

The prevalence of VFs by spinal level differed among the three groups; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.052). The prevalence of VFs was significantly higher at the thoracic level and significantly lower at the thoracolumbar level than expected in group A’ (P < 0.05; Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Percentage of spinal levels involved (a), type (b), and extent (c) of vertebral fractures. Data are shown as the percentage (number) of fractured vertebrae. *Significantly higher than expected (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). †Significantly lower than expected (†P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01)

There were significant differences in the types of prevalent VFs among the three groups (P < 0.01). The post hoc test showed that the percentage of biconcave-type deformities was significantly higher in group A’ (P < 0.01) and significantly lower in groups B’ and C’ (P < 0.05; Fig. 2b) than expected. In contrast, wedge-type deformities were significantly less frequent than expected in group A’ (P < 0.01).

The Chi-square test showed a significant difference in the extent of VFs among the groups (P < 0.05). There was a decreasing trend in the percentage of G3 VFs over time. The post hoc test showed that the percentage of G3 VFs in group A’ was significantly higher than expected (P < 0.05; Fig. 2c).

Osteoporosis treatment

To evaluate the treatment rate of osteoporosis, participants who did not require treatment (young adult, mean equal or more than 70%) were excluded from the analysis. The percentage of treatment rate of osteoporosis in participants with osteoporosis (BMD < 70% young adult mean) in groups A’ (8/45, 17.8%), B’ (16/31, 51.6%), and C’ (15/25, 60.0%) showed an increasing trend and a significant difference among the groups (P < 0.01; Fig. 3). A post hoc test showed that the treatment rate was significantly lower than expected in group A’ (P < 0.01; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Treatment rate for osteoporosis. Data are shown as the percentage (number) of participants with low bone mineral density (< 70% young adult mean). **Significantly higher than expected (P < 0.01). ††Significantly lower than expected (P < 0.01)

Discussion

This medical examination-based study demonstrated that the prevalence of prevalent VFs has decreased, and the pattern of VFs has changed over the last two decades in a typical Japanese mountain village. The reported prevalence of VFs varies widely due to the variety of regions, races, and definitions of prevalent VF [12]. Since the prevalence of VF is also known to differ between men and women and increases in an age-dependent manner [3, 13], the sex and age of participants from each time point were adjusted among the groups.

Yoshimura et al. conducted a cohort study to clarify the changes in prevalence and cumulative incidence of VFs in a rural Japanese community [13]. A total of 400 participants were selected and divided into four age strata from the 40 s to 70 s, each comprising 50 men and 50 women. Radiographic assessments performed in 1990 and 2000 showed a significant decrease in the prevalence of VFs, which concurred with the results of our study. They also suggested that nutritional improvements, such as calcium intake, over the decades from 1946 to 1975 might contribute to the decrease in the prevalence of VFs and the increase in BMD. Fujiwara et al. reported the incidence of thoracic vertebral fractures (TVF) in 14,607 individuals from Hiroshima and Nagasaki diagnosed based on lateral chest radiographs made from 1958 to 1986. The participants were classified into 10-year birth cohorts from 1880–1889 to 1930–1939. TVF incidence was significantly lower in the younger birth cohorts in men and women as seen in this study. The authors also suggested that nutritional improvement might be associated with the decrease in incidence of TVF.

In a meta-analysis, Ward et al. reported that smokers had significantly reduced bone mass than nonsmokers (never and former smokers) at all bone sites [14]. They also reported that smoking increased the lifetime risk of VFs by 13% and 32% in women and men, respectively. This study demonstrated a significant decrease in the smoking rate of older adults in accordance with the results of the National Health and Nutrition Survey, which showed a continuous decrease in the smoking rate in young and older adult Japanese populations [15]. Therefore, we speculated that a continuous decrease in the smoking rate in our cohort could be one of the factors that contributed to the decreasing prevalence of VFs in this study.

A previous study on the survey of physical strength and athletic abilities of older adults conducted by the Japan Sports Agency showed a continuous improvement in walking and balance ability during the two decades since 1998 [16, 17]. This improvement in physical condition is reportedly associated with the prevention of falls [18], which could also contribute to the decrease in the prevalence of VFs in our study.

Furthermore, the percentage of economically active population in the primary industry, such as forestry or agriculture, has decreased by 30% while that of the service sector had been increasing in the village [19]. Change in the work style from heavy manual work to an office job might also contribute to decrease in prevalent VFs.

A previous report on hip fracture patients in Japan by Takusari et al. showed that despite the increasing number of patients, the estimated incidence rates of hip fracture in both men and women aged 70–79 years in 2017 were the lowest among the surveys conducted from 1992 to 2017 and declined significantly over the 25-year period. They speculated that using a wide variety of drugs, especially bisphosphonates, for osteoporosis treatment and prevention of hip fracture might have decreased its incidence. In our study, osteoporosis treatment rates in participants with low BMD increased over the decades. Improvements in screening and medication for osteoporosis have, therefore, contributed to a decrease in prevalent VFs over the past two decades.

Spiegl et al. reported that upper thoracic VFs are more associated with skeletal fragility than the lower thoracolumbar spine [20]. Anderson et al. examined, in 40 cases with moderate or severe prevalent VFs and 80 age- and sex-matched controls, how spinal location affects the relationships between quantitative computed tomography-based bone measurements, including BMD and prevalent VFs [21]. They reported that while prevalent VFs at any location were significantly associated with BMD, upper spine (T4-T10) fractures were more strongly associated with BMD than lower spine (T11-L4) fractures. In accordance with these reports, this study showed that compared to the other groups, the prevalence of thoracic VF was higher and that of thoracolumbar VFs was lower in group A’, in which participants with BMD were the lowest among the groups.

In a population-based study of 300 older men and women, Jones et al. showed that biconcave deformities were more strongly associated with low BMD than were other types of deformities [22]. In accordance with their study, the BMD of participants with biconcave deformities in our cohort was significantly lower than that of participants with wedge deformities (P < 0.01, data not shown). The central region of the vertebral endplate adjacent to the nucleus pulposus was reported to be the weakest area and exposed to greater vertical stress than other regions, resulting in biconcave deformity [23]. Moreover, the central area of the vertebra without cortical bone is more likely to be influenced by trabecular bone loss, with which osteoporotic bone loss begins [24]. This study showed that the prevalence of biconcave-type fractures decreased, especially during the first decade, accompanied by a significant decrease in the number of VFs in each subject.

Severe VF has been associated with skeletal fragility due to aging and low BMD [3, 25]. Of the 2576 older women in the clinical study, Delmas et al. reported that women with grade 3 VFs were significantly higher for age and number of prevalent VFs and significantly lower for height, weight, and femoral neck BMD compared to women with less severe or no prevalent VFs [25]. In accordance with the previous study, our study showed that the percentage of severe (G3) VFs as well as the prevalence of VFs showed a decreasing trend over the decades, and that group A’ had a significantly higher percentage of G3 VFs than expected, accompanied by lower height, weight, and BMD than group C’.

Our study has several limitations. Originally, this study was designed to investigate changes in the prevalence of prevalent and incident VFs over two years. The participants in group A and B were extracted from those who underwent the first medical examination and second medical examination two years later from 1997 or 2009. Unfortunately, the next examination two years later from 2019 was not held due to COVID-19 pandemic and the investigation for change in incident VFs could not be performed. Thus, this study focuses on the change in prevalence of prevalent VFs over the last two decades. Therefore, there might be an unequal background of the participants among group A, B and C. Second, sample size in each group was smaller compared to those of the other epidemiological studies [3, 22]. Moreover, participants of this study were those who voluntarily underwent the medical examination for the elderly inhabitants recruited by an invitation letter from the town office. A majority of participants were elderly women. Therefore, this result does not reflect the prevalence of VFs in all age groups of men and women. Third, this study was conducted in a mountain village where many inhabitants are typically engaged in forestry and agriculture. Therefore, the occupation ratio in Japan differs from that of the general Japanese population. Furthermore, we have not evaluated the influence of health-related quality of life in the prevalence and characteristics of VFs. In this study, morphologic VFs were evaluated based on Genant’s semiquantitative method while pain symptom associated VFs was not evaluated. Finally, participants who could attend each medical survey were a relatively healthy population without serious illness and severe physical disability. Therefore, the participants in this study may differ from those of patients in a clinical setting.

In Conclusion, for the first time, we demonstrated a significant decrease in the prevalence of VFs in the rural Japanese population during the last two decades. The multifactorial improvement, including increased BMD, improvement in diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis, changes in lifestyle including decreased smoking rate, and strengthened physical status, may be factors contributing to the change in prevalence and characteristics of VFs.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

JY performed data acquisition, statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. KA performed data acquisition, drafted the manuscript, conceived of this study, and made substantial contributions to study design. NT, TF and AN performed data acquisition and revised the manuscript. AS contributed to the study design and coordination and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 15K08732.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author at a reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Committee for the Ethics of Human Research of Mie University (IRB reference number: U2018-022).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sambrook P, Cooper C. Osteoporosis. Lancet. 2006;367:2010–2018. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68891-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishimura A, Akeda K, Kato K, Asanuma K, Yamada T, Uchida A, Sudo A. Osteoporosis, vertebral fractures and mortality in a Japanese rural community. Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24:840–843. doi: 10.3109/14397595.2013.866921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horii C, Asai Y, Iidaka T, Muraki S, Oka H, Tsutsui S, Hashizume H, Yamada H, Yoshida M, Kawaguchi H, Nakamura K, Akune T, Tanaka S, Yoshimura N. Differences in prevalence and associated factors between mild and severe vertebral fractures in Japanese men and women: the third survey of the ROAD study. J Bone Miner Metab. 2019;37:844–853. doi: 10.1007/s00774-018-0981-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papaioannou A, Kennedy CC, Ioannidis G, Sawka A, Hopman WM, Pickard L, Brown JP, Josse RG, Kaiser S, Anastassiades T, Goltzman D, Papadimitropoulos M, Tenenhouse A, Prior JC, Olszynski WP, Adachi JD. The impact of incident fractures on health-related quality of life: 5 years of data from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:703–714. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0743-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salari N, Darvishi N, Bartina Y, Larti M, Kiaei A, Hemmati M, Shohaimi S, Mohammadi M. Global prevalence of osteoporosis among the world older adults: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16:669. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02821-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arai H, Ouchi Y, Toba K, Endo T, Shimokado K, Tsubota K, Matsuo S, Mori H, Yumura W, Yokode M, Rakugi H, Ohshima S. Japan as the front-runner of super-aged societies: perspectives from medicine and medical care in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15:673–687. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khosla S, Hofbauer LC. Osteoporosis treatment: recent developments and ongoing challenges (in Eng) Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:898–907. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30188-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akeda K, Yamada T, Inoue N, Nishimura A, Sudo A. Risk factors for lumbar intervertebral disc height narrowing: a population-based longitudinal study in the elderly (in Eng) BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:344–344. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0798-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishimura A, Hasegawa M, Kato K, Yamada T, Uchida A, Sudo A. Risk factors for the incidence and progression of radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee among Japanese. Int Orthop. 2011;35:839–843. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1073-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:1137–1148. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.García-pérez MA, Núñez-antón V. Cellwise Residual analysis in two-way contingency tables. Educ Psychol Meas. 2003;63:825–839. doi: 10.1177/0013164403251280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballane G, Cauley JA, Luckey MM, El-Hajj Fuleihan G. Worldwide prevalence and incidence of osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:1531–1542. doi: 10.1007/s00198-017-3909-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshimura N, Kinoshita H, Oka H, Muraki S, Mabuchi A, Kawaguchi H, Nakamura K. Cumulative incidence and changes in the prevalence of vertebral fractures in a rural Japanese community: a 10-year follow-up of the Miyama cohort (in Eng) Arch Osteoporos. 2006;1:43–49. doi: 10.1007/s11657-006-0007-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward KD, Klesges RC. A meta-analysis of the effects of cigarette smoking on bone mineral density. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;68:259–270. doi: 10.1007/bf02390832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemmi O, Nomura Y, Konishi H, Kakizoe T, Inoue M. Impact of reduced smoking rates on lung cancer screening programs in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2020;50:1126–1132. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyaa104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.JSA (2020) Japan Sports Agency. Nationwide survey of physical fitness, athletic ability, and exercise habits. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/dbview?sid=0003295660

- 17.Kidokoro T, Peterson SJ, Reimer HK, Tomkinson GR. Walking speed and balance both improved in older Japanese adults between 1998 and 2018 (in Eng) J Exerc Sci Fit. 2021;19:204–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jesf.2021.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwamoto J, Suzuki H, Tanaka K, Kumakubo T, Hirabayashi H, Miyazaki Y, Sato Y, Takeda T, Matsumoto H. Preventative effect of exercise against falls in the elderly: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1233–1240. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0794-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Odai-Town (2021) https://www.odaitown.jp/material/files/group/1/202106_vision.pdf

- 20.Spiegl UJ, Scheyerer MJ, Osterhoff G, Grüninger S, Schnake KJ. Osteoporotic mid-thoracic vertebral body fractures: what are the differences compared to fractures of the lumbar spine?—a systematic review. Eur J Trauma. 2021;48:1639–1647. doi: 10.1007/s00068-021-01792-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson DE, Demissie S, Allaire BT, Bruno AG, Kopperdahl DL, Keaveny TM, Kiel DP, Bouxsein ML. The associations between QCT-based vertebral bone measurements and prevalent vertebral fractures depend on the spinal locations of both bone measurement and fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:559–566. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2452-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones G, White C, Nguyen T, Sambrook PN, Kelly PJ, Eisman JA. Prevalent vertebral deformities: relationship to bone mineral density and spinal osteophytosis in elderly men and women. Osteoporos Int. 1996;6:233–239. doi: 10.1007/BF01622740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diacinti D, Guglielmi G. How to define an osteoporotic vertebral fracture? Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2019;9:1485–1494. doi: 10.21037/qims.2019.09.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osterhoff G, Morgan EF, Shefelbine SJ, Karim L, McNamara LM, Augat P. Bone mechanical properties and changes with osteoporosis (in Eng) Injury. 2016;47:S11–S20. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(16)47003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delmas PD, Genant HK, Crans GG, Stock JL, Wong M, Siris E, Adachi JD. Severity of prevalent vertebral fractures and the risk of subsequent vertebral and nonvertebral fractures: results from the MORE trial (in Eng) Bone. 2003;33:522–532. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author at a reasonable request.