Abstract

The importance of economic policy uncertainty (EPU) and environmental policy stringency (EPS) in affecting environmental quality is gaining great attention in the literature. However, none of the existing studies has thought to investigate their combined effects on carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. Additionally, the individual investigations into the nexuses EPU-emissions and EPS-emissions primarily took a symmetric assumption between these variables into consideration. The current paper is an early attempt to close these gaps by examining the combined effects of economic policy uncertainty and environmental policy stringency on CO2 emissions within asymmetric (nonlinear) frameworks in China and the United States (US). The empirical findings indicate that an improvement in EPU degrades the environmental quality in both countries. However, a negative shift in EPU decreases emissions in China while increasing them in the US. In terms of EPS, the estimates in the two nations led to similar results. A positive change in EPS is conducive to fewer emissions, whereas a negative change worsens environmental damage. These findings still hold with the sensitivity analysis using ecological footprint as an alternative gauge of environmental destruction. This study, therefore, suggests that both nations adopt stricter environmental policies. Additionally, Chinese policymakers should work to lessen uncertainty shocks, while the US government should promote more transparent economic policies.

Keywords: Economic policy uncertainty, Environmental policy stringency, CO2 emissions, Ecological footprint, China, The United States

Introduction

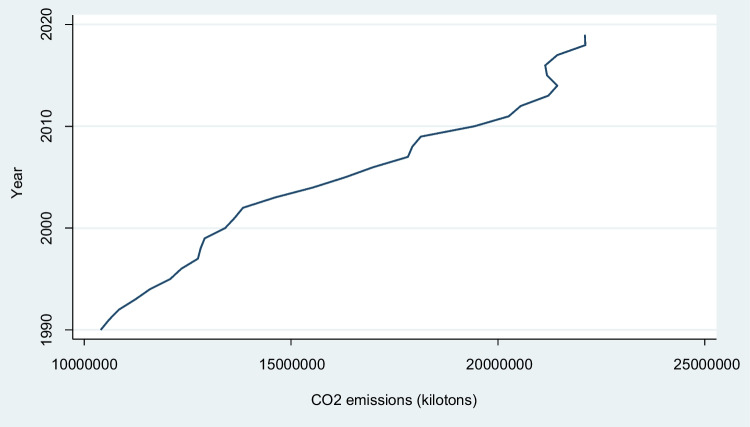

Consistent with the sustainable development goals (SDGs), every nation now has improving environmental quality as one of its major objectives. Addressing the pressing environmental problems of today is necessary to ensure this success. Among these, climate change poses substantial risks to the environment and human health, leading to hotter temperatures, stronger storms, more frequent droughts, rising sea levels, the extinction of species, the spread of diseases, and an estimated annual five million fatalities annually around the world (World Bank 2016). It is commonly known that the increases in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions seen over the past few decades are the primary factor contributing to climate change and the above-mentioned damaging consequences (IPCC 2021). For instance, Fig. 1 illustrates the trends in carbon emissions from the world’s top ten emitters between 1990 and 2019. Over this period, the global carbon emissions from these countries significantly surged from about 10.4 million to close to 22.1 million kilotons (World Bank 2021), aggravating climate change and global warming. Thus, improving the environmental quality is inextricably linked to a reduction in CO2 emissions (Jiang et al. 2022), which implies the need to identify and understand the potential influencing factors of CO2 emissions.

Fig. 1.

Trends in combined carbon emissions from the world’s top ten emitters

Among these factors, the literature attached great importance to the significant role of environmental policies. The primary driver of this interest is the expectation that environmental policies will internalize the negative externality caused by environmental pollution and help improve air quality (Hashmi and Alam 2019). These policies or regulations should create incentives for environmentally friendly behaviors from businesses and people. As a result, every nation’s efforts to combat climate change are increasingly driven by its stringency in environmental policy (Pinto et al. 2018). Consequently, some available studies have empirically evaluated the effectiveness of stricter environmental policies in reducing emissions. Though the prevailing idea is that environmental policy stringency (EPS) is conducive to fewer emissions (Cohen and Tubb 2018; Ahmed 2020; Wang et al. 2020), a few studies revealed the opposite impact and mostly suggested that EPS requires a certain time to have the desirable effect on the environment (Wolde-Rufael and Weldemeskel 2020; Wolde-Rufael and Mulat-Weldemeskel 2021).

Another potential contributor to emissions that has lately begun to receive attention in certain literature is economic policy uncertainty (EPU). A growing body of literature on the effects of EPU on various macroeconomic and financial variables, including investment choices, oil prices (Olanipekun et al. 2019), and stock market conditions (Adebayo et al. 2022), has evolved in response to the works of Bloom (2009) and later Baker et al. (2016). However, the impact of EPU on the environment lacked empirical evidence until the initial investigation by Jiang et al. (2019). Overall, they emphasized the need to consider EPU as an important influencing factor of the environmental quality since EPU typically influences the external environment of the businesses, which in turn could affect their production and investment decisions and, consequently, their CO2 emission performance. Moreover, the importance of EPU in affecting the environment should be stressed since the world is subject to economic and political instability due to global uncertainties (such as the recent COVID-19), which ultimately affect business decisions. Following Jiang et al. (2019), further research looked at the relationship between EPU and environmental quality with conflicting results (Adedoyin and Zakari 2020; Amin and Dogan 2021; Yu et al. 2021).

Considering their relevance, and as previously mentioned, some available studies have looked at how EPU and EPS affect the environment. However, it is worth noting that none of these studies has considered exploring the combined effects of EPS and EPU on carbon dioxide emissions. As pointed out by Jiang et al. (2019), economic policy uncertainty may affect the government’s commitment to efficiently implementing environmental policies, which could influence the environmental quality. Therefore, it could be worthwhile to look at how EPU and EPS together affect environmental degradation. Besides, most existing studies considered the symmetry assumption while examining the environmental impacts of EPU and EPS individually. However, as argued by Ahmed et al. (2021), the symmetric (linear) models may fall short of capturing true correlations between variables prone to uncertain economic, political, and environmental events, among others. Therefore, investigating the relationships between EPU, EPS, and emissions within asymmetric frameworks may be more feasible and realistic. Similarly, Sharif et al. (2020a) argued that the reliance on nonlinear estimation models helps to ensure the significance of empirical inquiries.

Addressing these gaps, this study assesses the simultaneous asymmetric effects of environmental regulation stringency and economic policy uncertainty on carbon dioxide emissions in China and the United States (US). The following are the justifications for focusing on these two nations: First, the fact that China and the US are the two biggest CO2 emitters in the world, accounting for roughly 44.93% of all carbon emissions in 2018 (World Bank 2021), underscores the significance and the role that these nations have to play in the fight against global warming and climate change. Second, as the two largest economies accounting for about 34% of the entire world’s GDP in purchasing power standards in 2020 (World Bank 2021), the global economy is subject to the effect of their domestic economic policies and the possible uncertainty associated, as evidenced by the 2007–2008 US financial crisis, and the recent and ongoing COVID-19 outbreaks. China and the US are currently implementing a number of economic policy reforms in response to policy uncertainty shocks; thus, EPU may have significant implications for the frequency of the two nations’ macroeconomic business cycles (Amin and Dogan 2021). Finally, there is still very little empirical evidence on the asymmetric nexuses EPU-emissions and EPS-emissions in the two countries. These factors make China and the US compelling cases for conducting such an investigation.

The contributions of the current investigation are listed below. First, it is a pioneering effort to investigate the combined asymmetric effects of environmental policy stringency and economic policy uncertainty on carbon dioxide emissions. To this end, the study relies on the nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) framework developed by Shin et al. (2014). This method extends the conventional and linear ARDL approach by capturing the short-run and long-run asymmetric relationships between variables subject to upward and downward trends in their dynamics, especially for relatively small-size samples. Second, to examine the nonlinear causalities between EPU, EPS, and CO2 emissions, the study uses the newly proposed nonlinear Granger causality test based on the vector autoregressive neural network (VARNN) model of Hmamouche (2020). Third, employing a different measure of environmental degradation in a robustness analysis, fresh insights are offered into the asymmetric relationships between EPU, EPS, and ecological footprint. Finally, the study also complies with the recent suggestions on the non-inclusion of energy consumption in the CO2 emission regression specifications since this may lead to biased results (Haug and Ucal 2019; Ahmed et al. 2021).

Overall, the findings of this study reveal long-term asymmetric effects of economic policy uncertainty and environmental policy stringency on CO2 emissions in China and the US. More specifically, positive shocks in EPU harm the environmental quality in the two countries. However, negative changes in EPU reduced CO2 emissions in China while increasing them in the US. Besides, increases in environmental policy stringency are beneficial to the environment in both China and the US. However, a negative shift in EPS raised CO2 emissions in the two nations. We find similar results in a robustness analysis using ecological footprint as an alternative measure of environmental degradation. Finally, the findings show unidirectional nonlinear EPS-emissions causation in the US and EPU-emissions causation in both nations. However, there is bidirectional causality between environmental policy stringency and carbon dioxide emissions in China.

The remainder of this essay is organized as follows. In part 2, the literature on the nexuses EPU-CO2 and EPS-CO2 emissions are reviewed. In the “Data and econometric technique” section, a thorough explanation of the data, model parameters, and the econometric procedure is given. The results are presented in the “Empirical results” section, and they are discussed and further clarified in the “Discussion of the results” section. Finally, the “Conclusion and policy implications” section presents the study’s conclusions and policy repercussions.

Literature review

Economic policy uncertainty and CO2 emissions

The literature on the impact of unclear economic policy on carbon emissions is relatively recent. The first study by Jiang et al. (2019) explored conceptually the mechanisms through which economic policy uncertainty might impact environmental quality. The first channel is concerned with environmental governance. From their perspective, higher uncertainty times may be detrimental to the environmental quality because governments’ attention could be fully (or more importantly) devoted to economic recovery and social measures, and this could be at the expense of consistent and efficient implementations of the environmental regulations. A second channel is related to the economic situation and the firms’ performance. According to them, a bad economic situation induced by EPU could lead to decreased energy demand and carbon emissions. However, Jiang et al. (2019) also emphasized that bad economic conditions may have negative environmental implications since they could incentivize businesses to increase their reliance on conventional cheap energy sources. This was further supported by Danish et al. (2020) and Yu et al. (2021). They stressed the importance of the energy intensity channel as mediation to the linkage between EPU and carbon emissions. It is clear from these theoretical justifications that the impact of EPU on environmental quality is not immediately apparent.

Although relatively limited, the empirical literature also revealed conflicting effects of EPU on environmental quality. According to certain research, EPU increased CO2 emissions. These included the study by Jiang et al. (2019) that analyzed the association between EPU and US sectoral CO2 emissions. Their findings showed that, except for the commercial sector, EPU positively influences the rise of carbon emissions in the lower distributions of this growth in all other sectors. Thus, they advised US policymakers to pay close attention to EPU during times of lower emissions. Still, in the US, Danish et al. (2020) discovered that EPU hindered environmental quality. Additionally, they noted that EPU increased the negative effects of energy intensity on CO2 emissions because it might reduce FDI inflow and deter the transfer of eco-friendly technologies. Likewise, Pirgaip and Dinçergök’s (2020) findings of a unidirectional causal relationship between US EPU and CO2 further suggest that national policies should be delineated without jeopardizing policy stability. Focusing on China, Amin and Dogan (2021) discovered that higher EPU causes CO2 emissions and suggested that Chinese policymakers reduce uncertainties by improving the transparency and consistency of adopted economic policies. This could positively influence the investors’ attitudes toward clean energy investments and helps to mitigate carbon emissions. Similarly, Yu et al. (2021) revealed that Chinese manufacturing companies’ carbon emission intensity increased due to higher EPU. An important contribution of their study is that they constructed and relied on a new EPU index for Chinese provinces. Furthermore, they determined that the most efficient transmission channels via which EPU favorably affects the carbon emission intensity of Chinese manufacturing enterprises are the fuel mix and energy intensity channels. Thus, they mainly called for efforts from the government to maintain continuous and stable economic policies to encourage manufacturing firms to optimize their energy consumption behaviors and reduce their emission intensity. More recently, Xue et al. (2022) disclosed that EPU encouraged larger emissions in France and suggested the French government reduce the domestic level of policy uncertainty. Moreover, they advised the government to engage in discussions with its citizens to adopt an optimum policy to eliminate possible misunderstandings regarding the social-economic effects of environmental policies. In contrast, Anser et al. (2021) discovered that raising EPU causes the top ten CO2 emitters to cut their emissions. As a result, they advised these nations to support policies that encourage innovation, renewable energy, and eco-friendly technology. Likewise, Adedoyin and Zakari (2020) revealed that increases in EPU initially (in the short run) curtailed UK CO2 emissions but, over time (in the long run), hurt the environmental quality. They argued that low EPU over time would raise industries’ income through investments, which in turn could facilitate their shift from traditional cheaper energy sources to cleaner energy and thus reduces carbon emissions. Thus, they emphasized the need to implement pertinent policies to discourage increases in CO2 emissions. Unlike previous studies, the Ahmed et al. (2021) research was the first to attempt to evaluate the asymmetric effects of EPU on CO2 emissions, in contrast to other studies. The findings demonstrated that changes in EPU, both positive and negative, decreased US CO2 emissions, with the negative shift having a stronger depressing effect. Therefore, they called for a reduction in EPU since this could allow businesses to afford cleaner energy sources and the government to focus on achieving long-term environmental sustainability goals.

Environmental policy stringency and CO2 emissions

The importance of environmental policies to cope with environmental pollution was extensively stressed in the environment-related literature. This is because pollution activities or any environmentally harmful behavior are undoubtedly negative externalities that cannot be handled by the market forces only and thus require government interventions (Zheng et al. 2014). Overall, the authors identified the direct cost channel as the main channel through which environmental regulations influence environmental quality. This channel refers to the incentives to reduce (or rise) pollution due to increases (or decreases) in the cost of polluting activities induced by environmental policies (Porter and Vander Linde 1995). These policies generally take the form of tax or emission permits. Thus, more stringent environmental policies such as higher prices per unit of pollutants or lower emission permits are expected to increase incentives to reduce emissions by making the producing-polluting activities expensive and less attractive (Neves et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020; Yirong 2022). In opposition, less stringent environmental regulations (such as low prices per pollutant unit or higher emission permits) are likely to cause an adverse effect. Another transmission channel, which can be identified from the literature and referred to as an indirect channel, is related to the incentives towards green innovation or innovation in clean technologies due to changes in the opportunity cost of pollution. In this sense, stricter environmental policies or measures such as higher public spending on renewable energy research and development or renewable energy tariff, which are aimed at reducing the input prices for competitive green products, will raise the opportunity cost of pollution and encourage firms to invest in clean technologies (Ahmed 2020; Wang et al. 2020). Similarly, Johnstone et al. (2012) stressed the importance of public demand (demand from government-related institutions) for environmentally friendly technologies in the economy. Recently, the role of environmental mass awareness as an influencing mechanism was also pointed out. For example, Wang and Shao (2019) and Ahmed (2020) believed that adequate (more stringent) environmental policies might stimulate and increase consumers’ awareness and encourage them to spend on green goods. A similar explanation holds for inadequate (less strict) environmental regulations. The theoretical discussions regarding the transmission channels revealed that the effect of environmental regulations on environmental pollution is not conclusive.

Along with these theoretical discussions, the nexus between environmental regulations and environmental degradation was extensively examined empirically. In order to save space, this empirical review is restricted to studies that used the OECD (2016) environmental policy stringency index to assess environmental regulation. This composite index incorporates market and non-market-based environmental regulations (Hille and Möbius 2019). Thus, the focus is firstly on studies that found a beneficial impact of strict environmental regulation on environmental quality. These comprised the Wang et al. (2020) study that confirmed that strict environmental policies improved the air quality measured by several indicators (including CO2, NOx, and SOx emissions) in 23 OECD countries. Likewise, Ahmed (2020) indicated that EPS reduces CO2 emissions while spurring innovation in clean technologies in 20 OECD countries. Similarly, Georgatzi et al. (2020), who focused on 12 European nations, discovered that EPS decreases CO2 emissions brought on by the transportation industry. They emphasized the beneficial effect of EPS in advancing new environmentally friendly technologies and raising the number of patents on the environment. In another study, Wang et al. (2022) reported that EPS mitigated CO2 emissions by boosting renewable energy transition in BRICS countries. Likewise, Wang et al. (2019) indicated that EPS reduced carbon dioxide emissions in 62 OECD and non-OECD countries. Besides, the single-country study of Ahmed and Ahmed (2018) also confirmed the beneficial effect of EPS on the environment in China. Conversely, another strand of few studies revealed that the severity of environmental regulations has detrimental impacts on the environment. These included the analysis of Wolde-Rufael and Mulat-Weldemeskel (2021), which found a harmful effect of EPS on environmental quality, at least before reaching a certain threshold, in seven emerging countries. This finding suggested that the effectiveness of environmental policies requires a certain time. A similar conclusion was found by the same authors when they examined the impact of EPS on CO2 emissions in BRIICTS countries (Wolde-Rufael and Weldemeskel 2020). Unlike the studies mentioned above, which concentrated on the symmetric nexus, Yirong (2022) adds to the body of research by exploring the asymmetry relationship between the severity of environmental regulation and CO2 emissions. Focusing on the top five emitters, the results showed that changes in environmental policy stringency, both positive and negative, are beneficial to the quality of the environment. Therefore, he advised that when creating environmental rules, officials in those highly polluted economies should consider this asymmetry aspect.

To sum up, the literature review revealed that none of the previous studies had examined the combined effects of uncertain economic policy and strict environmental policy on environmental quality. The existing body of literature has rather separately analyzed the environmental effects of EPU and EPS, with inconclusive results. Furthermore, with very few exceptions, most previous studies only took a symmetric assumption into account when examining the distinct effects of EPU and EPS on environmental quality. Thus, by examining the combined asymmetric effects of EPU and EPS on CO2 emissions in China and the United States, the current study seeks to close this gap and add to the body of literature. Due to their status as the world’s two largest economies and carbon dioxide polluters, the focus on these two nations is particularly pertinent. Additionally, this study is the first to look into the combined asymmetric effects of EPU and EPS on ecological footprint.

Data and econometric technique

Data and variable selection

Data sources and the theoretical relevance of the selected variables

Using quarterly time-series data for China and the United States, the current study examines the effects of EPU and EPS on CO2 emissions. The time selection ranges for China from 1995Q1 to 2020Q4 and the United States from 1985Q1 to 2020Q4 based on the data availability for the relevant variables. Following Jiang et al. (2019), Amin and Dogan (2021), Wolde-Rufael and Mulat-Weldemeskel (2021), and Yirong (2022), a thorough discussion of the significance of adding EPU and EPS in the CO2 emission models was presented in the previous section. Overall, there is conflicting evidence in the literature about how EPS and EPU affect CO2 emissions.

Besides, the following control variables are also taken into account in this analysis based on prior research on the factors that drive CO2 emissions. These firstly include economic growth (GDP per capita), which is believed, relying on Grossman and Krueger’s (1991) environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) hypothesis, to initially harm the environment through a strong reliance on fossil fuel energy to support the growth process. However, over time, GDP per capita is expected to improve environmental quality through technological efficiency (notably in the energy sector) and environmental awareness channels. The literature has covered the EKC hypothesis in great detail (Sapkota and Bastola 2017; Shahbaz et al. 2018; Sharif et al. 2019; Assamoi et al. 2020; Jahanger et al. 2022a, among others). Unlike most of these studies, and to prevent potential multicollinearity problems, this analysis does not incorporate the square of GDP per capita into the emission models to test the validity of the EKC hypothesis. The study followed Narayan and Narayan’s (2010) methodology, which involved comparing the GDP per capita’s short- and long-run elasticities.

Second, the literature also underlined the significance of urbanization (URB) in impacting the environment. It is anticipated that increased urbanization, typically correlated with increased energy demand and consumption, will have a detrimental impact on environmental degradation (Liu and Bae 2018; Ali et al. 2019; Salahuddin et al. 2019). One argument is that people in metropolitan regions tend to use more energy-intensive products than their counterparts in rural areas, such as various home appliances. In addition, it is thought that urbanization promotes the growth of manufacturing businesses, private transportation, and the development of public infrastructures, all of which need greater energy consumption and raise pollution levels.

Finally, this analysis also incorporates the role of technological innovation in the emission models. It is anticipated that technological advancement will accelerate the creation and adoption of cutting-edge energy-efficient technology, which could further enhance environmental quality (Churchill et al. 2019; Chen and Lee 2020). Additionally, effective technologies might aid nations in making the best use and usage of their natural resources, which could lower emissions (Obobisa et al. 2022). In the same vein, Godil et al. (2021) argued that technological innovation would improve economic output without requiring additional amounts of potential energy-intensive inputs. This analysis substitutes research and development spending for technical innovation, following Xu and Lin (2016), Petrovic and Lobanov (2019), and Wang et al. (2019).

Table 1 summarizes the variables’ data sources, measurement units, and descriptive statistics. Following Shahbaz et al. (2020) and Ahmed et al. (2021), the monthly data for EPU and the annual data for the other variables were converted into quarterly data using the quadratic-match sum option of the low-to-high frequency approach. The advantage of this method is that it can smooth out data with too much volatility.

Table 1.

Variables description and statistics summary

| Abbreviation | Indicator name | Unit | Collecting source | China | United States | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Max | Min | JB | Prob | Mean | Max | Min | JB | Prob | ||||

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide emissions | Metric tons | Global Carbon Atlas | 6251.21 | 9976.05 | 3353.29 | 43.99 | 0.001 | 5763.59 | 6128.54 | 5345.98 | 49.61 | 0.000 |

| EPU | Economic policy uncertainty | Index | “Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty” by Baker et al. (2016) | 109.64 | 246.48 | 40.15 | 29.15 | 0.000 | 109.75 | 194.98 | 62.33 | 42.07 | 0.000 |

| EPS | Environmental policy stringency | Index | OECD (a) | 4060.91 | 8120.61 | 1547.82 | 27.91 | 0.011 | 50,816.3 | 56,979.11 | 42,018.26 | 39.11 | 0.001 |

| GDP | Gross domestic product per capita | Constant 2010$ | World Development Indicators | 1.30 | 2.066 | 0.56 | 53.16 | 0.000 | 2.62 | 2.80 | 2.42 | 26.53 | 0.001 |

| URB | Urban population | % of total population | World Development Indicators | 42.96 | 55.76 | 31.16 | 36.94 | 0.000 | 79.85 | 81.71 | 77.34 | 28.25 | 0.000 |

| RD | Gross domestic spending on R&D | Total, % of GDP | OECD (b) | 1.01 | 2.16 | 0.52 | 46.55 | 0.000 | 1.88 | 3.06 | 1.059 | 37.05 | 0.000 |

JB stands for Jarque–Bera statistics, and Prob refers to the probability (P-value). Global Carbon Atlas: (https://www.globalcarbonatlas.org/en/CO2-emissions);

Economic Policy Uncertainty: (https://www.policyuncertainty.com);

OECD (a): (https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EPS); OECD (b): (https://data.oecd.org/rd/gross-domestic-spending-on-r-d.htm)

World Development Indicators: (https://www.databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators)

Empirical relevance of the selected variables: the least shrinkage and selection operator (Lasso) and Ridge regressions

In addition to the theoretical background, this study relies on the Lasso and Ridge models to motivate the choice of selected variables explaining CO2 emissions in this inquiry. The Lasso method introduced by Frank and Friedman (1993) and Tibshirani (1996) involves a shrinkage process that sets the coefficients of the less important predictors to zero and suggests removing them from the model. Hence, it serves as a variable-selection technique and helps highlight the more contributing predictors that are suggested to be kept in the model. For sensitivity analysis, the Ridge regression is also applied. Unlike the Lasso, the Ridge regression does not set any coefficient estimates to zero; however, it involves more severe constraints while shrinking them toward zero (James et al. 2013). The outputs in Table 2 confirmed the importance of all selected explanatory variables since the coefficient of each predictor differs from zero (in the Lasso regression) in both countries. Hence, the selection of these explanatory variables is empirically justified.

Table 2.

Lasso and Ridge regressions

| LASSO | RIDGE | |

|---|---|---|

| China | ||

| Intercept | 1.04923041 | 1.65688116 |

| EPU | 0.01547942 | 0.01166932 |

| EPS | 0.03215219 | 0.15352486 |

| GDP | 0.76344315 | 0.28438557 |

| URB | 0.68775322 | 0.65445244 |

| RD | 0.13759127 | 0.15308357 |

| United States (US) | ||

| Intercept | 1.15923406 | 0.77390804 |

| EPU | − 0.05288953 | − 0.06794641 |

| EPS | − 0.06939917 | − 0.05345050 |

| GDP | 0.60602604 | 0.36592741 |

| URB | 0.60356133 | 0.79296629 |

| RD | − 0.31020309 | − 0.23192605 |

The nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) model and asymmetric cointegration test

This study intends to evaluate the asymmetric impacts of stringent environmental regulations and unpredictable economic policies on carbon dioxide emissions in China and the United States. The NARDL method created by Shin et al. (2014) is used to achieve this goal. The main reason is that the NARDL framework provides the advantage of capturing and allowing for nonlinear and asymmetric correlations between variables that could come from uncertain political, economic, and natural events, in contrast to the ARDL and other linear approaches. Additionally, the NARDL model has the benefits of the traditional ARDL, including the flexibility to include both I(0) and I(1) variables in the analysis, the capacity to handle potential concerns with the endogeneity of specific variables, and the well-proven effectiveness in small-sample sizes (Sharif et al. 2017; Haug and Ucal 2019). The NARDL model used in this investigation adopts the following specification based on the above discussions and the environmental functions provided by Ahmed et al. (2021) and Yirong (2022):

| 1 |

where , standardized on yields the long-run coefficients, whereas reflects the corresponding short-term coefficients, and IID (0, ). and denote, respectively, the positive and negative shifts in EPU (and EPS). According to the Akaike information criteria, the up scripts m, n, o, p, q, r, s, and indicate the optimal lags. The subscripts i and t, respectively, stand for the nation (China and the US) and the time. Finally, the term DUM refers to the dummy variable corresponding to the data’s most frequent structural break (date break), as determined by Zivot and Andrews’ unit root test. All factors are taken into account in their logarithmic form to make it easier to interpret the findings. The partial sums of the variables for economic policy uncertainty and environmental policy, according to Shin et al. (2014), are further decomposed into positive () and negative changes as follows:

| 2 |

| 3 |

The ARDL bounds test presented in Shin et al. (2014) is used to validate the asymmetric (nonlinear) cointegration among variables before the long-run estimations. A combined test for the lagged levels of the regressors is used with the null hypothesis that cointegration does not occur. The comparison between the F-statistics (t-statistics) and the critical values of the extreme bounds determines the null hypothesis’ acceptation (or rejection). Additionally, the short-run () and long-run () asymmetries of the EPU and EPS variables are tested using the Wald tests.

The long-run estimations are carried out after the cointegration relationship has been verified. Based on Eq. (1), and , respectively, can be used to compute the long-term estimates of the positive and negative changes in EPU on CO2 emissions. Similarly, and capture the long-term effects of both positive and negative shocks in EPS on CO2 emissions.

Finally, this inquiry captures the asymmetric dynamic multipliers effects through the following expressions:

| 4 |

| 5 |

where, if , then , and indicate the asymmetric reactions of CO2 emissions to positive and negative shocks in economic policy uncertainty and environmental policy stringency. The dynamic adjustment to the new equilibrium point in the variables system can be captured from the computed multipliers in Eqs. (4) and (5).

Nonlinear Granger causality test

Since the long-run asymmetric (nonlinear) association between economic policy uncertainty, environmental policy stringency, and carbon dioxide emissions is confirmed, the study further explores the nonlinear causal relationships between them. To this end, the paper adopts the proposed nonlinear Granger causality test using the artificial (feed-forward) neural network (ANN) of Hmamouche (2020). Unlike the traditional linear Granger causality, this proposed test intends to deal with nonlinear dependencies between variables. Hence, instead of only considering vector autoregressive (VAR) models as in the classic Granger causality test, Hmamouche (2020) rather relied on vector autoregressive neural network (VARNN) models. The VARNN model combines both VAR models and neural networks, which are nonlinear and nonparametric methods and proved to perform well in forecasting nonlinear time series (Sun et al. 2019). The architecture of the VARNN model involves a transfer function that processes the nonlinear estimation in the hidden layer (which serves as an interface between the input and the output layers). Further and detailed explanations of the VARNN model are provided by Sun et al. (2019). Following Hmamouche (2020), the based-VARNN model causality test between two variables, K and L, involves the two predictions models specified as follows:

| 6 |

| 7 |

where and , respectively, represent the network functions (using the VARNN model) of Models 1 and 2, is the lag parameter, and indicates the error terms. The null hypothesis of this test (that is, K does not cause L) is examined using the Fisher test, which compares the residual sum of squares (RSS) of the errors from the two models. Accordingly, the statistic F of the Fisher test is computed as follows:

| 8 |

where and , respectively, indicate the number of the parameters in Models 1 and 2, and is the size of the lagged variables.

Empirical results

Unit root tests and BDS nonlinearity test

The unit root analysis is employed as the initial phase in this empirical inquiry to ascertain the order of the variables’ integration because the NARDL approach only requires I(0) or I(1) variables. First, common unit root tests like the Dickey–Fuller GLS and Philips–Perron (PP) tests were applied. The results in Table 3 confirmed that all the variables are stationary at the first difference, except for EPS, which was shown to be stationary at the level for both nations. In terms of the variables’ integration order, the NARDL requirement is thus satisfied.

Table 3.

Common unit root tests

| DF–GLS | Phillips–Perron | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | First difference | Level | First difference | |

| Country | China | |||

| CO2 | − 2.14 | − 3.12** | − 1.81 | − 4.56** |

| EPU | − 2.45 | − 3.53* | − 2.06 | − 3.59*** |

| EPS | − 4.01*** | − 7.45*** | − 2.32 | − 5.51 |

| GDP | − 2.36 | − 4.37*** | − 1.47 | − 4.17*** |

| URB | − 1.45 | − 3.91** | − 2.06 | − 6.86*** |

| RD | − 1.23 | − 3.41* | − 1.72 | − 5.83** |

| Country | United States | |||

| CO2 | − 1.84 | − 4.34*** | − 2.11 | − 5.01*** |

| EPU | − 2.23 | − 3.81** | − 1.65 | − 3.76** |

| EPS | − 2.93* | − 5.026** | − 2.22 | − 3.91*** |

| GDP | − 1.79 | − 2.97* | − 1.87 | − 5.21*** |

| URB | − 2.18 | − 3.67** | − 2.04 | − 4.36** |

| RD | − 1.07 | − 3.85* | − 1.83 | − 4.21*** |

*, **, and *** denote 10%, 5%, and 1% level of significance, respectively

The study also uses the Zivot–Andrews (ZA) unit root test because, as Solarin et al. (2017) noted, the reliability of the aforementioned traditional tests was heavily challenged and questioned when the series experienced structural discontinuities. The ZA test is carried out under the null hypothesis that the variable has a unit root with a structural break and allows for a structural shift in the series. Table 4 demonstrates that all variables, either I(0) or I(1), satisfy the NARDL methodology’s integration order criteria. Moreover, the findings of the ZA test revealed that most break dates (six out of 12) in China were observed at the beginning of the 2000s, with the break 2002Q1 as the most recurrent. This can be linked to the accession of China to the World Trade Organization in December 2001, which implied structural reforms to improve the manufacturing capacity and infrastructure to support internal and external demand. As for the United States, it was observed that most variables experienced a sudden and abrupt change in the years 2007 and 2008 (seven out of 12), which coincided with the 2007–2008 great financial crisis experienced by the country that significantly affected the overall economy. Based on the ZA test, the study incorporates a dummy variable for 2002Q1 and 2007Q2 into the emission models of China and the US, respectively.

Table 4.

Zivot–Andrews unit root test

| Variables | Level | First difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-stat | Break date | T-stat | Break date | |

| China | ||||

| CO2 | − 3.892[4] | 2002Q1 | − 6.612***[4] | 2001Q2 |

| EPU | − 3.677[4] | 2015Q2 | − 5.674**[4] | 2015Q1 |

| EPS | − 3.536[4] | 2011Q2 | − 5.111**[4] | 2008Q2 |

| GDP | − 1.345[4] | 2008Q2 | − 5.581***[4] | 2005Q2 |

| URB | − 3.273[2] | 2000Q3 | − 7.872***[4] | 2002Q1 |

| RD | − 4.951**[2] | 2000Q2 | − 6.765***[2] | 2002Q1 |

| United States | ||||

| CO2 | − 0.721[4] | 2009Q2 | − 5.035**[4] | 2007Q2 |

| EPU | − 1.786[4] | 2007Q2 | − 5.822***[4] | 2008Q3 |

| EPS | − 0.265[2] | 2005Q4 | − 5.414***[2] | 1992Q1 |

| GDP | − 1.901[4] | 2007Q2 | − 4.775*[4] | 2008Q1 |

| URB | − 1.022[2] | 1990Q1 | − 5.883***[2] | 2007Q3 |

| RD | − 1.789[2] | 2008Q2 | − 5.332**[4] | 2010Q1 |

*, **, and*** indicate 10%, 5%, and 1% level of significance, respectively. The critical values for the ZA test are − 5.34, − 4.93, and − 4.58 at 1%, 5%, and 10% significance levels, respectively. Lag lengths are indicated in brackets

Besides, we checked for the nonlinear behavior of the variables of interest in this study (CO2, EPU, and EPS) by using the Broock–Dechert–Scheinkman (BDS) test. It is a nonparametric test developed by Broock et al. (1996) to detect nonlinear serial dependence in time series. The null hypothesis of the BDS test assumes linearity of the series, whereas the alternative hypothesis suggests nonlinearity of the variables. Table 5 reports the BDS test results, which indicate the rejection of the null hypothesis and, thus, confirm the nonlinearity in CO2, EPU, and EPS in both countries.

Table 5.

Broock–Dechert–Scheinkman (BDS) test

| Countries | CO2 | EPU | EPS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDS | BDS | BDS | ||

| China | 2 | 0.206*** | 0.174*** | 0.192*** |

| 3 | 0.349*** | 0.284*** | 0.318*** | |

| 4 | 0.447*** | 0.352*** | 0.402*** | |

| 5 | 0.514*** | 0.394*** | 0.457*** | |

| 6 | 0.559*** | 0.419*** | 0.494*** | |

| United States | 2 | 0.181*** | 0.157*** | 0.180*** |

| 3 | 0.304*** | 0.251*** | 0.299*** | |

| 4 | 0.389*** | 0.306*** | 0.378*** | |

| 5 | 0.449*** | 0.337*** | 0.428*** | |

| 6 | 0.491*** | 0.356*** | 0.461*** |

*** indicates the rejection of the null hypothesis at 1%. We report the BDS test results for the variables of interest (CO2, EPU, and EPS) only for clarity purposes. However, the BDS test results for the control variables are available on request

NARDL asymmetric cointegration and diagnostic tests

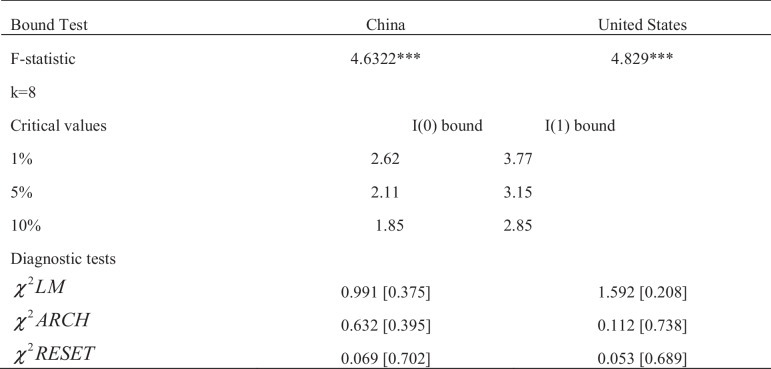

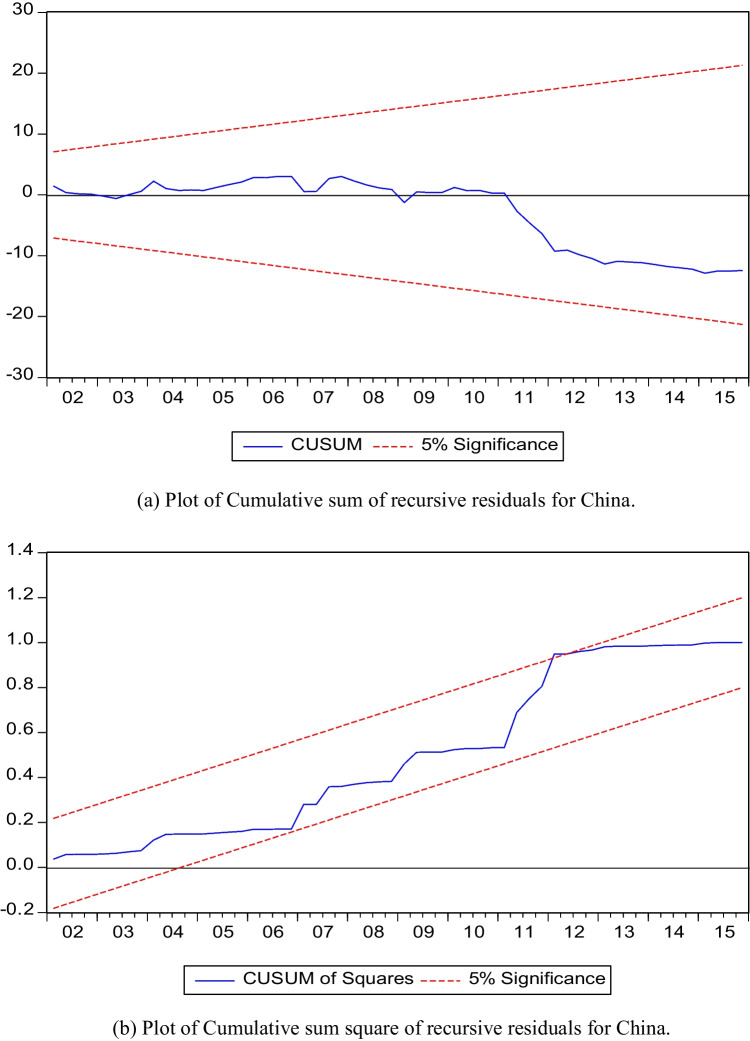

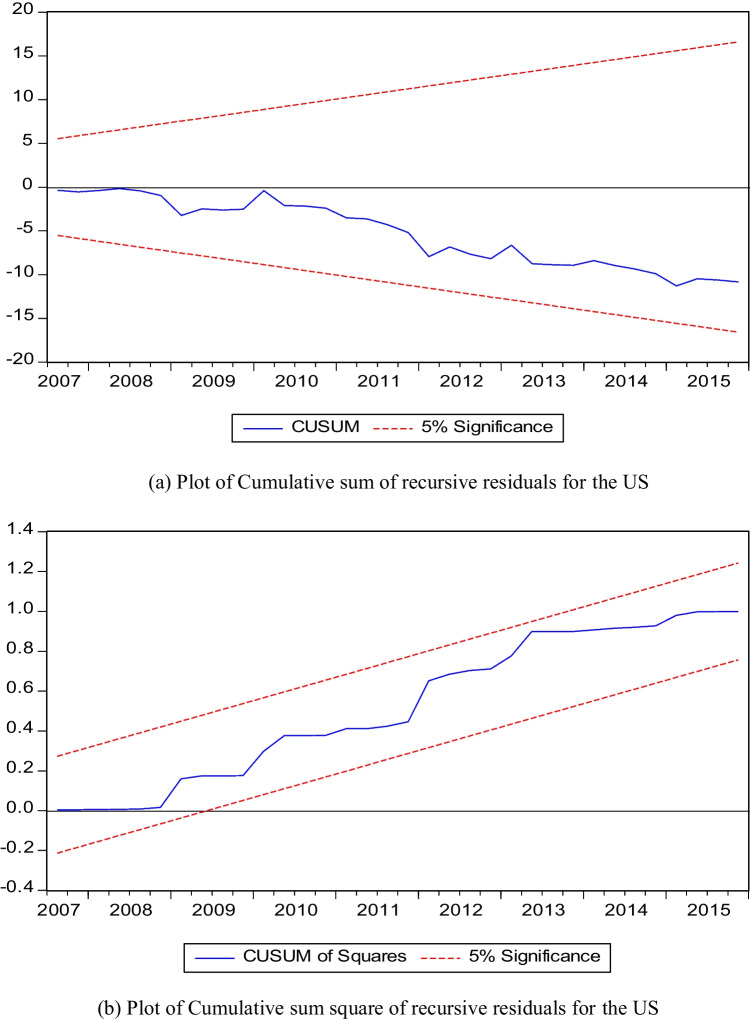

The cointegration study was conducted to verify the long-term relationship between the variables once it had been shown that each variable was I(0) or I(1). As mentioned earlier, this analysis was based on the bound test covered by Shin et al. (2014). Table 6’s findings show that there is cointegration between the variables in both nations because the F-stat values (4.632 for China and 4.829 for the US) are higher than the critical values’ upper bound of 3.77 at the 1% level of significance. This validates the long-term link between the variables. Additionally, various diagnostic tests were carried out to determine the effectiveness of the models. Due to the differing p-values of these tests (the LM and ARCH tests, respectively) being greater than 0.10, the results shown in Table 6 demonstrated that the emission models in the two countries are free from serial correlation and heteroskedasticity. Additionally, because the p-values of the Ramsey reset test (0.702 for China and 0.689 for the US) are higher than 0.10, the various models do not suffer any misspecification. Last but not least, the stability of the models is determined by the cumulative sum (CUSUM), and cumulative sum of square (CUSUMSQ) values seen in Figs. 2 and 3 in Appendix.

Table 6.

Bound test for cointegration and diagnostic tests

*** indicates a 1% level of significance. The p-values of the diagnostic tests are in brackets

Fig. 2.

Plot of cumulative sum and cumulative sum square of recursive residuals for China

Fig. 3.

Plot of cumulative sum and cumulative sum square of recursive residuals for the United States

Long-run and short-run estimations

After the cointegrating connection has been verified, the long-run estimates are computed and shown in Table 7. As demonstrated by the results, CO2 emissions in China will, respectively, increase and decrease in response to positive and negative shocks to uncertainty in economic policy. More clearly, China’s emissions increased by 0.045% for every 1% increase in EPU, while they decreased by 0.021% for every 1% decrease in EPU. However, in the case of the US, both positive and negative shocks will hurt the environment quality. More specifically, CO2 emissions in the US will go up by 0.059% and 0.062% for a 1% positive and negative change in EPU, respectively. As for the long-term environmental effects of strict environmental policy, the findings are remarkably comparable in both nations regarding the sign and significance. In China and the US, a 1% increase in EPS reduces emissions by 0.042% and 0.046%, respectively, which enhances environmental quality. A 1% decrease in EPS, on the other hand, causes CO2 emissions in China and the US to rise by 0.017% and 0.054%, respectively.

Table 7.

NARDL long-run results

| Country | China | United States | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Coefficient | P-value | Coefficient | P-value |

| EPU+ | 0.045** | 0.034 | 0.059* | 0.042 |

| EPU− | − 0.021** | 0.036 | 0.032*** | 0.000 |

| EPS+ | − 0.042* | 0.062 | − 0.046*** | 0.002 |

| EPS− | 0.017** | 0.031 | 0.054** | 0.033 |

| GDP | 0.853*** | 0.008 | 1.461*** | 0.000 |

| URB | 0.078* | 0.058 | 0.055 | 0.228 |

| RD | − 0.022** | 0.042 | − 0.024* | 0.055 |

| Dummy | 0.003 | 0.163 | − 0.007* | 0.084 |

| C | 3.761** | 0.037 | 4.626*** | 0.009 |

| R2 | 0.982 | 0.977 | ||

| AdjR2 | 0.975 | 0.969 | ||

| DW | 2.08 | 2.11 | ||

| Wald tests | ||||

| EPU | F = 5.014** | 0.022 | F = 7.521*** | 0.009 |

| EPS | F = 5.123** | 0.016 | F = 7.302*** | 0.002 |

*, **, and *** denote 10%, 5%, and 1% level of significance, respectively. The dummy variable corresponds to 2002Q1 for China and 2007Q2 for the United States

Regarding the control variables, the findings confirmed that economic growth contributes to rising emissions levels. In both countries, a 1% rise in GDP is expected to push carbon emissions by 1.132% in China and 1.65% in the US. Likewise, urbanization was also found to distort the environment quality in both countries, even if the positive impact on emissions in the US was not significant. A 1% increase in the urbanization levels in China leads to a 0.078% increase in carbon emissions. Conversely, domestic spending on research and development is conducive to fewer carbon emissions in both countries. The dummy variable for the first quarter of 2002 has no discernible effect on emissions in China, whereas the second quarter of 2007 has a marginally negative impact on emissions in the US.

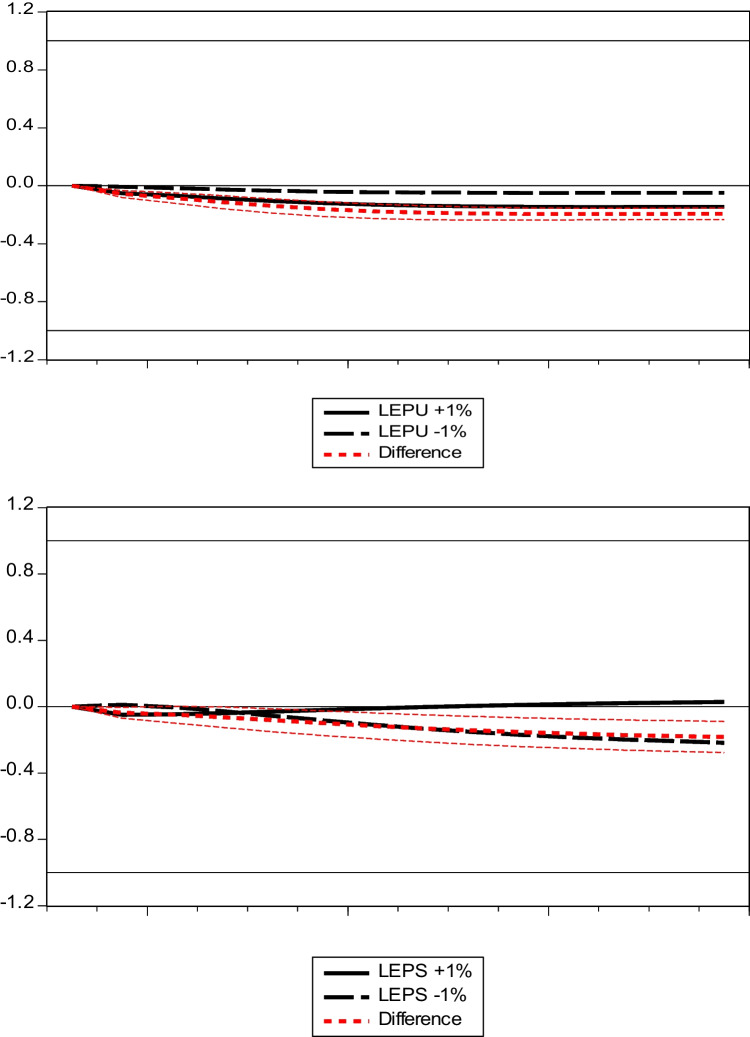

Furthermore, the Wald test outcomes give evidence of significant long-run asymmetric associations between EPU and CO2 and between EPS and CO2 in the two countries since the p-values in the various cases are less than at least 10%. Lastly, Figs. 4 and 5 in Appendix display the NARDL multipliers for both nations. The black dots represent the CO2 asymmetries adaptations to negative shocks in EPU (EPS), whereas the solid black lines show the corresponding adaptations to EPU’s (EPS’s) positive shifts. Finally, the red dotted lines depict the asymmetric pattern that differentiates between positive and negative shocks.

Fig. 4.

Dynamic multipliers for EPU and EPS in China

Fig. 5.

Dynamic multipliers for EPU and EPS in the United States

The study also reports the NARDL short-run estimations in Table 8. Overall, the results support the long-term findings on the significance and signs of the EPS and control variables coefficients in both countries. Likewise, the signs of the EPU effects on emissions in China do not vary over time. The economic policy uncertainty’s positive and negative shocks, though, produced no appreciable short-term environmental impacts in the United States. Additionally, the error correction terms’ (ECT) significance and negative sign supported the long-term correlation between the variables in China and the US. The Wald tests confirm the short-run asymmetries of EPU and EPS in both countries.

Table 8.

NARDL short-run results

| Country | China | United States | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Coefficient | P-value | Coefficient | P-value |

| EPU+ | 0.016** | 0.047 | 0.018 | 0.562 |

| EPU− | − 0.008* | 0.066 | 0.038 | 0.417 |

| EPS+ | − 0.019** | 0.035 | − 0.024* | 0.063 |

| EPS− | 0.011* | 0.074 | 0.015* | 0.058 |

| GDP | 1.132*** | 0.000 | 1.657*** | 0.000 |

| URB | 0.036* | 0.062 | 0.052 | 0.335 |

| RD | − 0.015** | 0.023 | − 0.026* | 0.043 |

| Dummy | 0.019 | 0.245 | − 0.013 | 0.281 |

| ECT | − 0.059*** | 0.000 | − 0.068*** | 0.000 |

| Wald tests | ||||

| EPU | F = 4.382* | 0.067 | F = 5.591*** | 0.005 |

| EPS | F = 4.463** | 0.026** | F = 7.952*** | 0.003 |

Same as Table 7

Nonlinear Granger causality test

The study further analyzes the nonlinear causality between EPU, EPS, and CO2 after demonstrating the long-run asymmetric (nonlinear) relationship between them. This was accomplished by relying on the based-VARNN nonlinear Granger causality of Hmamouche (2020). According to the findings in Table 9, uncertainty in economic policy has a unidirectional nonlinear causal influence on carbon emissions in China and the US. Similarly, there is a one-way nonlinear causal direction from US stringency in environmental policy to carbon dioxide emissions. However, a bidirectional nonlinear causality was found between China’s carbon dioxide emissions and environmental policy uncertainty. It should be noted that the nonlinear Granger causality was performed with two hidden layers in the VARNN model and a maximum number of lags set to two based on the AIC criterion.

Table 9.

Nonlinear Granger causality

| Countries | Null hypothesis (HO) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPU CO2 | CO2 EPU | EPS CO2 | CO2 EPS | |

| China | ||||

| GCI | 0.385 | 0.052 | 0.352 | 0.426 |

| F-stat | 2.901*** | 0.258 | 2.758*** | 3.051*** |

| P-value | 0.000 | 0.998 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| Decision | Reject HO | No reject HO | Reject HO | Reject HO |

| United States | ||||

| GCI | 0.310 | 0.107 | 0.296 | 0.087 |

| F-stat | 2.666*** | 0.544 | 2.485*** | 0.347 |

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.914 | 0.003 | 0.942 |

| Decision | Reject HO | No reject HO | Reject HO | No reject HO |

“” indicates “does not Granger cause (nonlinearly) to.” GCI denotes the Granger causality index

Robustness analysis: ecological footprint, as an alternative measure of the environmental degradation

The paper explores the asymmetric impacts of EPU and EPS on ecological footprint as a sensitivity analysis. Since it intends to examine the effect of human demand on natural resources, the ecological footprint is frequently used as a gauge of the environmental quality in the literature (Solarin 2019; Ullah et al. 2021; Jahanger et al. 2022b; Rafei et al. 2022). Unlike carbon emissions which mainly refer to an air pollution concept, the ecological footprint encompasses different aspects of environmental degradation, including carbon footprints, fishing grounds, forest land, cropland, grazing area, and built-up land. Thus, it provides a more inclusive picture of the land, air, and water degradation (Solarin 2019; Suki et al. 2019). The data on ecological footprint originated from the Global Footprint Network and covered the same periods as previously, with the only difference being that the latest data were available in 2018. Table 10 lists the long-term asymmetric effects of stringency in environmental policy and economic policy uncertainty on ecological footprint. According to the results, a 1% positive change in EPU causes the ecological footprint in China and the US to grow by 0.033% and 0.041%, respectively. Conversely, a 1% negative change in EPU induces a 0.018% decrease in ecological footprint in China while leading to a 0.023% rise in the US. Regarding the effects of EPS, a 1% positive shock is conducive to a reduction in the ecological footprint of 0.049% and 0.036% in China and the US, respectively. In opposition, negative change in EPS encourages a higher ecological footprint in both countries. Overall, these findings are quite similar in terms of significance to those of the analysis with CO2 emissions, indicating the robustness of the results.

Table 10.

Robustness analysis: long-term asymmetric effects of EPU and EPS on ecological footprint

| Country | China | United States | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Coefficient | P-value | Coefficient | P-value |

| EPU+ | 0.033* | 0.067 | 0.041** | 0.028 |

| EPU− | − 0.018* | 0.056 | 0.023* | 0.074 |

| EPS+ | − 0.049** | 0.024 | − 0.036** | 0.013 |

| EPS− | 0.021*** | 0.003 | 0.047** | 0.036 |

| GDP | 1.152*** | 0.006 | 1.764*** | 0.001 |

| URB | 0.083** | 0.018 | 0.066* | 0.088 |

| RD | − 0.026* | 0.054 | − 0.028** | 0.027 |

| Dummy | 0.003 | 0.163 | − 0.004* | 0.248 |

| C | 4.583*** | 0.007 | 3.444*** | 0.005 |

| R2 | 0.971 | 0.981 | ||

| AdjR2 | 0.957 | 0.979 | ||

| DW | 2.04 | 2.06 | ||

| Diagnostic tests | ||||

| 0.912 [0.534] | 1.112 [0.381] | |||

| 0.411 [0.405] | 0.226 [0.648] | |||

| 0.057 [0.691] | 0.044 [0.623] | |||

| Wald tests | ||||

| EPU | F = 5.346** | 0.047 | F = 6.716** | 0.016 |

| EPS | F = 5.683** | 0.035 | F = 7.085*** | 0.005 |

Discussion of the results

The main findings of this inquiry indicate that positive changes in EPU will cause more pollution by rising CO2 emissions in both China and the US. This result is in agreement with Jiang et al. (2019) and Danish et al. (2020), as times of high EPU are generally associated with less stringency from the government regarding environmental degradation issues. During those periods, economic activity recoveries are generally considered top-priority issues far ahead of environmental issues. This could negatively affect the implementation of environmental policies and, in turn, encourage more air pollution. Another possible explanation is that those periods of high EPU lead to bad economic conditions that may eventually incentivize people to rely on conventional, less expensive energy sources, which could ultimately raise emissions, as supported by Pirgaip and Duncergok (2020). For instance, Demir and Gozgor (2016) discovered that periods of high EPU helped to lower the number of miles that US vehicles were driven. Regarding the negative changes in EPU, the findings reveal opposite effects on CO2 emissions in the two countries. The negative shocks in EPU decrease CO2 emissions in China, meaning that periods of low uncertainties benefit the environmental quality. A reason is that, in periods of low uncertainties, governments may become more concerned and stringent in implementing environmental policies, which in turn may positively affect the environmental quality. Likewise, low uncertainties may promote businesses’ investments and more job opportunities for people, which could increase their income and enable them to afford relatively expensive modern and cleaner energies. This result supports the conclusions reached by Ahmed et al. (2021). Conversely, negative change in EPU surprisingly leads to more emissions in the US. This could be explained by the tendency that businesses may have to increase their energy consumption in support of potential additional investments induced by low uncertainties. Besides, during low uncertainty times, people may be more reluctant to save, increasing their tendency to consume more goods and services. This could boost economic activities and energy consumption. Thus, the combined increase in energy consumption from businesses’ investments and people’s consumption would negatively affect the environmental quality. These results are in consonance with Anser et al. (2021). Besides, in harmony with Ahmed et al. (2021), the evidence of unidirectional EPU-emissions causation identified in both nations suggested that unpredictable economic policies influence environmental quality.

Another meaningful finding relates to the asymmetric effects of environmental policy stringency on carbon dioxide emissions. In China and the US, a positive change in EPS reduces CO2 emissions. This outcome means that more stringent environmental policies improve the environmental quality in the two largest emitter countries. This is in line with Wang et al. (2020) and Yirong (2022), as stricter environmental policies by increasing the costs of polluting activities push firms and businesses to promote environmental-friendly technologies and investment projects. Moreover, stringent environmental regulations might increase mass awareness and compel people to adopt eco-friendly consumption behaviors, as reported by OECD (2016). Another possible explanation of the positive influence of stricter EPS on the environment is related to the green technology channel. As supported by Ahmed (2020), more stringent environmental-oriented policies in reducing input prices for green products may induce higher investments in environmental-related technology, which might further mitigate carbon emissions. In opposition, a negative change in EPS boosts emissions in both countries. This finding implies that periods of less stringent environmental policies are associated with rising emissions. An explanation is that during those periods, firms and businesses have fewer incentives to shift the reliance of their production process towards cleaner energy and technologies since there is a decrease in extra costs of harming the environmental quality. Besides, less strict environmental regulations might not stimulate the awareness and willingness of people to consume green products. Furthermore, the findings exhibit bidirectional causality between China’s EPS and carbon emissions. This suggests that the strictness of environmental policies affects CO2 emissions, and in turn, environmental degradation influences the stringency of the environmental regulations in China. This result follows Georgatzi et al. (2020), which revealed bidirectional causality between EPS and emissions brought on by the transport sector. However, in the US, the causality goes one way from EPS to emissions, suggesting that EPS affects environmental quality. This outcome is in accordance with Wolde-Rufael and Mulat-Weldemeskel (2021), who demonstrated EPS-to-CO2 emissions causation in seven emerging countries.

Regarding the effects of the control variables, the findings confirmed that economic growth escalates emissions in both China and the US. The fact that the long-term impact is less than the short-term one, however, shows that rising GDP per capita over time lowered emissions. In light of Narayan and Narayan (2010), the EKC theory is therefore supported in both nations. This resonates with several inquiries on the growth-environment nexus (Nasir et al. 2019; Assamoi et al. 2020; Sharif et al. 2020b; Khan and Ozturk 2021; Kassi et al. 2022) as the growth process initially heavily relied on fossil fuels energy which significantly deteriorates the environmental quality. However, this deterioration will be gradually lessened with enormous efforts toward clean energy transition and people’s increasing awareness and demand for a green environment in further stages of economic development. Besides, higher levels of urbanization were also found to encourage more emissions in China. This unsurprising outcome lies in the fact that higher urbanization goes up with the energy demand and thus increases emissions (Bello et al. 2018; Ali et al. 2019; Salahuddin et al. 2019). Finally, both countries reduced carbon emissions by higher spending on research and development. This emphasizes the importance of technological innovation induced by higher R&D spending in mitigating CO2 emissions, as supported by Xu and Lin (2016), Wang et al. (2019), and Chen et al. (2022).

Finally, it is noteworthy that the effects of EPU and EPS on the environment in China and the US are robust to the measure of environmental damage. As shown in the robustness analysis, EPU and EPS also have long-term asymmetric impacts on the ecological footprint of the world’s two largest economies. Specifically, positive changes in EPU increased the ecological footprint in both countries. This resonates with the recent study of Jiao et al. (2022) that indicated that EPU raises the ecological footprint by hindering investments in renewable energy and R&D. Similar to the emission models, negative changes in EPU reduce the ecological footprint in China while increasing it in the United States. Besides, positive shocks in the stringency of environmental policies improve the environmental quality by lowering the ecological footprint in both countries, while negative changes in EPS have an adverse effect.

Conclusion and policy implications

It is an undeniable fact that continuous increases in carbon dioxide emissions are the foremost cause of climate change leading to disastrous consequences on both the environment and human health. To address this issue and help improve the environmental quality, there is an absolute need to reverse the long-term ongoing increasing trend observed in CO2 emissions. To this end, the potential factors influencing CO2 emissions need to be identified and understood. This study concentrated on how China and the United States emissions, the world’s two largest economies and largest emitters of carbon dioxide, were affected by the uncertainty of economic policy and the strictness of environmental regulation. Unlike the existing literature, the current paper was an early attempt to examine the concurrent impacts of EPU and EPS on CO2 emissions. Furthermore, the combined influence of these two factors on environmental quality was analyzed within asymmetric (nonlinear) frameworks employing the NARDL approach and the recently published nonlinear Granger causality test based on the feed-forward neural network model. The paper also investigated the combined asymmetric effects of EPU and EPS on ecological footprint, employed as a substitute evaluation of environmental damage, in a robustness analysis.

The major conclusions showed that both EPU and EPS had long-term asymmetric effects on CO2 emissions in China and the US, with a notable difference regarding the influence of negative change in EPU. More specifically, the results indicated that positive changes in EPU hurt the environmental quality in both countries. Negative shock in EPU, on the other hand, decreased CO2 emissions and raised environmental quality in China. However, a negative shift in EPU in the US also encourages higher emissions. The results indicated that tougher environmental rules had a good impact on the environment in both China and the US with regard to the asymmetries of their effects. However, the two nations’ carbon dioxide emissions increased due to the negative EPS shift. With the robustness analysis, similar outcomes are obtained. Additionally, in China, the short-term estimates generated the same results as the long-run ones, while in the US, EPU and EPS showed no appreciable short-term asymmetric effects on emissions. The data also revealed unidirectional nonlinear EPS-emissions causation in the US and EPU-emissions causation in both nations. However, China’s emissions data showed a bidirectional causal relationship between environmental policy stringency and emissions.

In conformity with the empirical findings, the study suggests the following policy implications. First, China and the US should increase the stringency in environmental policies to reduce environmental degradation. The strictness of environmental regulations will incentivize firms and consumers to adopt environmentally friendly behaviors. In this sense, recent laudable regulatory changes such as the Revised Environmental Protection Law in 2014 and the Environmental Protection Tax Law entered into force in 2018 in China should be efficiently promoted and implemented. Besides, the degree of stringency in environmental policies in China should also consider the current level of emissions in the country. Second, to improve the environmental quality, policymakers in China should strive to reduce uncertainty shocks associated with their economic policies. As for the United States, policymakers need to pay careful attention to the transparency of their economic policies and avoid those that can be a source of uncertainty since either positive change or negative change in EPU leads to higher emissions. Third, the two nations should work on improving the reliance of their economic growth on clean and modern energy sources rather than conventional ones. In this regard, they should adopt policies such as subsidies to ensure access to affordable, reliable, and sustainable energy for more economic participants in the country. Fourth, there is a need to increase domestic spending on R&D in both countries, which could boost innovation and technological development in the energy sector and improve environmental quality. Finally, Chinese policymakers should prioritize sustainable urbanization by fostering more efficient land use and resource management.

This inquiry has some limitations. It has investigated the asymmetric impacts of EPU and EPS on CO2 emissions in China and the United States using aggregate-level data. In so doing, the investigation disregarded the possible regional disparities within each country. Hence, future studies can consider examining the asymmetric environmental effects of EPU and EPS using regional-level (i.e., state-level or provincial-level) data. Likewise, the use of aggregate-level data in this analysis ignored to highlight the asymmetric influences of both EPU and EPS on emissions in different sectors within the two economies. Therefore, another avenue for further studies could include the sectoral differences in the analysis. Lastly, future investigations may consider exploring the interacting effects of EPU and EPS with some variables such as eco-innovation and renewable energy on the environment.

Appendix

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Guy Roland Assamoi and Shaoyuan Wang. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Guy Roland Assamoi, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The data and materials that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adebayo TS, Akaridi SS, Rjoub H. On the relationship between economic policy uncertainty, geopolitical risk, and stocks market returns in South Korea: a quantile causality analysis. Annals Financ Econ. 2022;17(1):2250005. doi: 10.1142/S2010495222500087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adedoyin FF, Zakari A. Energy consumption, economic expansion, and CO2 emission in the UK: the role of economic policy uncertainty. Sci Total Environ. 2020;738:140014. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed K, Ahmed S. A predictive analysis of CO2 emissions, environmental policy stringency, and economic growth in China. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25(16):16091–16100. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-1849-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed K. Environmental policy stringency, related technological change and emissions inventory in 20 OECD countries. J Environ Manage. 2020;274:111209. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Z, Cary M, Shahbaz M, Vo VX. Asymmetric nexus between economic policy uncertainty, renewable energy technology budgets, and environmental sustainability: evidence from the United States. J Clean Prod. 2021;313:127723. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali R, Bakhsh K, Yasin MA. Impact of urbanization on CO2 emissions in emerging economy: evidence from Pakistan. Sustain Cities Soc. 2019;48:101553. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2019.101553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amin A, Dogan E. The role of economic policy uncertainty in the energy-environment nexus for China: evidence from the novel dynamic simulations method. J Environ Manage. 2021;292:112865. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anser MK, Apergis N, Syed QR. Impact of economic policy uncertainty on CO2 emissions: evidence from top ten carbon emitter countries. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28:29369–209378. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-12782-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assamoi GR, Wang S, Liu Y, Gnangoin TBY, Kassi DF, Edjoukou AJR. Dynamics between participation in global value chains and carbon dioxide emissions: empirical evidence for selected Asian countries. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2020;27(14):16496–16506. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-08166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SR, Bloom N, David SJ. Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Q J Econ. 2016;131(4):1593–1636. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjw024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bello MO, Solarin SA, Yen YY. The impact of electricity consumption on CO2 emissions, carbon footprint, water footprint and ecological footprint: the role of hydropower in an emerging economy. J Environ Manage. 2018;219:218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.04.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom N. The impact of uncertainty shocks. Econometrica. 2009;77:623–685. doi: 10.3982/ECTA6248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broock WA, Scheinkman JA, Dechert WD, LeBaron B. A test for independence based on the correlation dimension. Economet Rev. 1996;15(3):197–235. doi: 10.1080/07474939608800353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Lee CC. Does technological innovation reduce CO2 emissions? Cross-Country Evid J Clean Prod. 2020;263:121550. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Ahmad S, Arshad S, Ali S, Rizwan M, Saleem MH, Driha OM, Balsalobre-Lorente D. Towards achieving eco-efficiency in top 10 polluted countries: the role of green tehnology and natural resources rents. Gondwana Res. 2022;110:114–127. doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2022.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill SA, Inekwe J, Smyth R, Zhang X. R&D intensity and carbon emissions in the G7. Energy Econ. 2019;80:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2018.12.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MA, Tubb A. The impact of environmental regulation on firm and country competitiveness: a meta-analysis of the porter hypothesis. J Assoc Environ Resour Econ. 2018;5:371–399. [Google Scholar]

- Danish U, R., Khan, S. Relationship between energy intensity and CO2 emissions: does economic policy matter? Sustain Dev. 2020;28(5):1457–1464. doi: 10.1002/sd.2098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir E, Gozgor G. The impact of economic policy uncertainty on the vehicle miles traveled (vmt) in the US. Eurasian J Bus Manag. 2016;4:39–48. doi: 10.15604/ejbm.2016.04.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frank IE, Friedman JH. A statistical view of some chemometrics regression tools. Technometrics. 1993;35(2):109–135. doi: 10.1080/00401706.1993.10485033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Georgatzi VV, Stamboulis Y, Vestikas A. Examining the determinants of CO2 emissions caused by the transport sector: empirical evidence from 12 European countries. Econ Anal Policy. 2020;65:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2019.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Godil DI, Yu Z, Sharif A, Usman R, Khan, SAR (2021) Investigating the role of technological innovation and renewable energy in reducing transport sector CO2 emission in China: a path toward sustainable development. Sustain Dev1–14. 10.1002/sd.2167

- Hashmi R, Alam K. Dynamic relationship among environmental regulation, innovation, CO2 emissions, population, and economic growth in OECD countries: a panel investigation. J Clean Prod. 2019;231:1100–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haug AA, Ucal M. The role of trade and FDI for CO2 emissions in Turkey: nonlinear relationships. Energy Econ. 2019;81:297–207. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2019.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hmamouche Y. NlinTS: An R package for causality detection in time series. R Journal. 2020;12(1):21–31. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2020-016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hille E, Möbius P. Environmental policy, innovation, and productivity growth: controlling the effects of regulation and endogeneity. Environ Resource Econ. 2019;73:1315–1355. doi: 10.1007/s10640-018-0300-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) (2021) In: Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pirani A, Connors SL, Pean C, Berger S, Caud N, Chen Y, Goldfarb L, Gomis MI, Huang M, Leitzell K, Lonnoy E, Matthews JBR, Maycook TK, Waterfield T, Yelekci O, Yu R, Zhou B. (Eds), Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2391 pp.

- Jahanger A, Usman M, Balsalobre-Lorente D (2022a) Linking institutional quality to environmental sustainability. Sustain Dev 1-17. 10.1002/sd.2345

- Jahanger A, Usman M, Murshed M, Mahmood H, Balsalobre-Lorente D. The linkages between natural resources, human capital, globalization, economic growth, financial development, and ecological footprint: the moderating role of technological innovations. Resour Policy. 2022;76:102569. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James G, Witten D, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. An introduction to statistical learning with applications in R. New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Yu Y, Jahanger A, Balsalobre-Lorente D. Structural emissions reduction of China’s power and heating industry under the goal of “double carbon”: a perspective from input-output analysis. Sustain Prod Consump. 2022;31:346–356. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2022.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Zhou Z, Liu C. Does economic policy uncertainty matter for carbon emission? Evidence from US sector level data. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26:24380–24394. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05627-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Xiao X, Bao X. Economic policy uncertainty, geopolitical risks, energy output and ecological footprint – empirical evidence from China. Energy Rep. 2022;8(6):324–334. doi: 10.1016/j.egyr.2022.03.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone N, Hascic I, Poirier J, Hemar M, Michel C. Environmental policy stringency and technological innovation: evidence from survey data and patent counts. Appl Econ. 2012;44(17):2157–2170. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2011.560110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kassi DF, Li Y, Riaz A, Wang X, Batala LK. Conditional effect of governance quality on the finance-environment nexus in a multivariate EKC framework: evidence from the method of moments-quantile regression with fixed-effects models. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29:52915–52939. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-18674-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M, Ozturk I. Examining the direct and indirect effects of financial development on CO2 emissions for 88 developing countries. J Environ Manage. 2021;293:112812. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Bae J. Urbanization and industrialization impact of CO2 emissions in China. J Clean Prod. 2018;172:178–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan PK, Narayan S. Carbon dioxide emissions and economic growth: panel data evidence from developing countries. Energy Policy. 2010;38(1):661–666. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2009.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nasir MA, Huynh TLD, Tram HTX. Role of financial development, economic growth & foreign direct investment in driving climate change: a case of emerging ASEAN. J Environ Manage. 2019;242:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.03.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves SA, Marques AC, Patrício M. Determinants of CO2 emissions in European Union countries: does environmental regulation reduce environmental pollution? Econ Anal Policy. 2020;68:114–125. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2020.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obobisa SE, Chen H, Mensah IA. The impact of green technological innovation and institutional quality on CO2 emissions in African countries. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2022;180:121670. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- OECD (2016) How stringent are environmental policies? http://www.oecd.org/eco/greeneco/how-stringent-are-environmental-policies.htm. Accessed Apr 2022

- Olanipekun I, Olasehinde-Williams G, Akadiri SS. Gasoline prices and economic policy uncertainty: what causes what, and why does it matter? Evidence from 18 selected countries. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26(15):15187–15193. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-04949-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto GMC, Pedroso B, Moraes J, Pilatti LA, Picinin CT. Environmental management practices in industries of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) from 2011 to 2015. J Clean Prod. 2018;198:1251–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porter ME, Van der Linde C. Toward a new conception of the environment competitiveness relationship. J Econ Perspect. 1995;9(4):97–118. doi: 10.1257/jep.9.4.97. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic P, Lobanov MM. The impact of R&D expenditures on CO2 emissions: evidence from sixteen OECD countries. J Clean Prod. 2019;248:119187. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pirgaip B, Dinçergök B. Economic policy uncertainty, energy consumption and carbon emissions in G7 countries: evidence from a panel Granger causality analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2020;27:30050–30066. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-08642-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafei M, Esamaeili P, Balsalobre-Lorente D. A step towards environmental mitigation: how do economic complexity and natural resources matter? Focusing on different institutional quality level countries. Resour Policy. 2022;78:102848. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota P, Bastola U. Foreign direct investment, income and environmental pollution in developing countries: panel data analysis of Latin America. Energy Econ. 2017;64:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2017.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salahuddin M, Gow J, Ali MI, Hossain MR, Al-Azami KS, Akbar D, Gedikli A. Urbanization-globalization-CO2 emissions nexus revisited: empirical evidence from South Africa. Heliyon. 2019;5(6):e01974. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz M, Nasir MA, Roubaud D. Environmental degradation in France: the effects of FDI, financial development, and energy innovations. Energy Economics. 2018;74:843–857. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2018.07.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz M, Raghutla C, Song M, Zameer H, Jiao Z. Public-private partnerships investment in energy as new determinant of CO2 emissions: the role of technological innovations in China. Energy Econ. 2020;86:104664. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif A, Jammazi R, Raza AS, Shahzad SJH. Electricity and growth nexus dynamics in Singapore: fresh insights based on wavelet approach. Energy Policy. 2017;110:686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2017.07.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]