Abstract

Psychological distress and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors are highly prevalent among undergraduate students. Importantly, numerous longitudinal studies show that these phenomena rise significantly during the first months of college and remain high thereafter. However, research identifying theory-driven mechanisms to explain these phenomena is lacking. Using two complementary statistical approaches (person- and variable-centered), this study assesses basic psychological needs (BPNs) and self-control as possible explanatory factors underlying the association between student’s educational experience and multiple health-related outcomes. A total of 2450 Canadian undergraduates participated in this study study involving two time points (12 months apart; NTime1 = 1783; NTime2 = 1053), of which 386 participated at both measurement occasions. First, results from person-centered analyses (i.e., latent profile and transition analyses) revealed three profiles of need-satisfaction and frustration in students that were replicated at both time points. Need-supportive conditions within college generally predicted membership in the most adaptive profile. In turn, more adaptive profiles predicted higher self-control, lower levels of psychological distress (anxiety, depression), and healthier lifestyle behaviors (physical activity, fruit and vegetable consumption). Second, results from variable-centered analyses (i.e., structural equation modeling) showed that the association between students’ BPNs and health-related outcomes was mediated by self-control. In other words, high need satisfaction and low need frustration were associated with higher self-regulatory performance at Time 1, which in turn predicted a more adaptive functioning at Time 2. Overall, these findings help clarify the mechanisms underlying the association between college educational climate and students’ health-related functioning.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12144-022-04019-5.

Keywords: Basic psychological needs, Self-control, Psychological distress, Health behaviors, Educational climate, Latent transition analysis

The health of college students has become a significant and growing concern on campuses. One in three college students meets criteria for a clinically significant mental health problem such as anxiety and depression (Auerbach et al., 2018; Eskin et al., 2016). Beyond these indicators of psychological distress, college students are also known for adopting several unhealthy lifestyle behaviors such as physical inactivity and low consumption of fruit and vegetable (Calamidas & Crowell, 2018; Whatnall et al., 2020). Interestingly, longitudinal studies have highlighted that the transition to college was a critical period for the onset of psychological distress and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors. For instance, levels of anxiety and depression rise significantly after the transition from high school to college, and do not fall back to pre-college levels, even after several months (Bewick et al., 2010; Cooke et al., 2006). Meanwhile, physical inactivity and poor eating habits were also shown to rise after the transition to college and these behaviors were linked to important weight gains in the first year of higher education (Deforche et al., 2015; Vadeboncoeur et al., 2015).

These findings suggest that the college years generally rhyme with heightened distress and unfavorable changes in students’ health behaviors, which entail a spiral of other negative consequences. Indeed, psychological distress (e.g., anxiety, depression) can lead to poor academic functioning in the form of low achievement, absenteeism, and high drop-out rates (Sharp & Theiler, 2018). Students suffering from psychological distress are also more likely to have suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Mortier et al., 2018) and are more vulnerable to future mental health disorders (Arango et al., 2018). On the other hand, unhealthy lifestyle behaviors (e.g., physical inactivity, poor eating habits) are risk factors for several non-communicable diseases that can reduce mobility and independence in later life, in addition to significantly shortening life expectancy (Loef & Walach, 2012). Moreover, unhealthy lifestyle behaviors and psychological distress often co-develop (Jao et al., 2019), increasing the risk associated with experiencing one or the other. Ultimately, college is an important period for promoting students’ physical and psychological well-being given that health patterns in young adults are directly linked to health patterns in later life.

In light of these consequences, it is not surprising that higher education institutions are under increasing pressure to provide adequate support for students’ well-being (Sheldon et al., 2021). In response to this pressure, efforts are being made to improve psychological support services offered to students and reduce on-campus barriers to healthy lifestyles (Gouvernement du Québec, 2021). Identifying pathways to healthier functioning in college students has also become a central area of research throughout the last two decades (Zhang et al., 2016). Several studies have been conducted to uncover individual (e.g., stress, financial difficulties, self-esteem) and contextual (e.g., dissatisfaction with the curriculum, workload, social support) factors playing a role in students’ mental health and lifestyle (see Mello Rodrigues et al., 2019; Moulin et al., 2021; Sheldon et al., 2021 for recent literature reviews). However, despite this large body of research, there is a notable lack of studies that examine theoretical explanations for the onset of students’ psychological distress and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors in college. This is an important shortcoming given that a theoretical understanding of the processes involved can potentially lead to better intervention applications (Michie et al., 2005). To address this gap, this study relied on two important psychological frameworks in the education and health domains, self-determination theory and the study of self-control, to examine why and how an important proportion of students develop symptoms of psychological distress and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors during their first year in college.

Self-determination theory

Self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2017) is a broad framework of human behavior and development that is particularly concerned with human flourishing. At the heart of SDT lies the assumption that each individual has three basic psychological needs (BPNs) representing the core determinants of their vitality, motivation, and well-being across life domains, including education (Ryan & Deci, 2020). These needs are autonomy (having a sense of volitional functioning and ownership in one’s actions), competence (experiencing a sense of effectiveness and mastery when interacting with one’s environment), and relatedness (experiencing meaningful and reciprocal relationships with important others). Importantly, the theory proposes two different pathways to psychological development and functioning. On the one hand, the satisfaction of each BPN should foster individuals’ active propensities towards growth and well-being. On the other hand, the frustration of any BPN should entail maladjustment and symptoms of ill-being (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). In support of these propositions, accumulating research evidence has revealed important relations between BPNs and a wide variety of psychological health indicators, including psychological well-being, depression, and anxiety (Ryan & Deci, 2017; Sheldon & Krieger, 2007). Through their positive effects on motivational outcomes, BPNs were also linked to health behaviors, including physical activity and diet (Gillison et al., 2019).

Self-control

Self-control1 represents the ability to down-regulate undesirable thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, and to mobilize desirable ones, especially in the face of temptations and impulses (Baumeister & Heatherton, 1996). Because of its association with numerous self-regulatory processes, general self-control strength (i.e., trait self-control) has been consistently shown to predict a broad range of positive health-related outcomes among various populations (Tangney et al., 2004), including college students. For instance, students with high trait self-control tend to present low levels of psychological distress because they engage in adaptative coping styles when facing academic-related stressors (Powers et al., 2020). They also tend towards healthy exercise and eating habits because they are able to resist temptations and invest the time and effort that such behaviors require (i.e., planification, preparation; de Vet & Verkooijen, 2018; Tomasone et al., 2015). Trait self-control, just like BPNs, is thus an important determinant of health-related functioning.

According to the strength model of self-control (Baumeister et al., 1994), being in control of oneself represents an effortful operation that relies on a limited pool of mental energy. This model postulates that self-control resembles a muscle in that it is vulnerable to deterioration when used repeatedly over a certain period of time. Acts of self-control can therefore exert one’s limited resources, leading to an ego-depleted state that increases passivity, and therefore the risk of self-control failures (Baumeister et al., 2018).

Multiple meta-analyses (e.g., Dang, 2018; Dang et al., 2017) and large scale experimental studies (e.g., Dang et al., 2021; Garrison et al., 2019) have supported the ego depletion effect by showing that initial exertion of self-control impairs subsequent self-regulatory performance. However, other serious research endeavours have failed to replicate the ego depletion effect (e.g., Hagger et al., 2016; Vohs et al., 2021). According to many scholars, this replication crisis is primarily due to conceptual and methodological limitations that impede the ability of the current dual-task paradigm to generate the ego depletion effect in the first place (de Ridder et al., 2018; Forestier et al., 2022). Among these limitations is the use of experimental tasks that have little to no relevence from a motivational and affective standpoint. However, resolving a motivational conflict (or self-control dilemma) represents the energy-depriving aspect of self-control; it is this aspect that should lead to an ego-depleted state (Forestier et al., 2022). Based on these considerations, the phenomenon of ego depletion should not be discarted (de Ridder et al., 2018).

Likewise, SDT scholars have also been critical of the ego depletion effect due to the lack of consideration of motivational factors (Ryan & Deci, 2008). More precisely, these scholars have proposed that the amplitude of the ego depletion effect should be impacted by BPN experiences, and particularly by need frustrating ones (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). Past studies have correspondingly demonstrated that need satisfaction increases vitality (i.e., the energy available to the self) while need frustration erodes available energy because it promotes controlled forms of regulation characterized by pressure, tension, and negative emotions (Moller et al., 2006; Ryan & Deci, 2008). These forms of external regulation, by consuming more energy, further burden the individual’s regulatory capacity, thus leading to or increasing the ego depletion effect. Moreover, beyond ego depletion, need frustration can also lead to a compensation phenomenon where individuals will volontarily stop self-regulating their behaviors in order to restore their sense of volition, effectiveness, and belonging (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013).

These theroetical propositions imply that students experiencing need frustration in college may have to mobilize important resources to meet frustrating academic demands, leaving them deprived and short of energy for repeling their hedonistic impulses. These students might also be at risk of engaging in a compensation phenomenon, relying on self-comforting behaviors such as academic procrastination and low-energy activities (e.g., watching TV shows, eating out) to alleviate the negative feelings generated by need frustrating experiences in college (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). Over time, need frustration in college could thus contribute to heightened psychological distress and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors through impaired self-control. In contrast, need satisfaction could facilitate students’ self-regulatory capacities, leading to healthier functioning. Although a limited number of studies have concretely assessed the association between BPNs and self-control, the available evidence shows that experiences of need satisfaction and need frustration are strong predictors of general self-control strength (e.g., Bai et al., 2020; Mills & Allen, 2020).

Need-nurturing conditions in college

Given the importance of BPNs for adaptive functioning and wellness, an important body of research has focused on social-contextual conditions that support or thwart their satisfaction. This has led to the proposition of six dimensions of practices related to the support or thwarting of each BPN that are purported to foster need satisfaction or need frustration, respectively (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). In educational contexts, teachers and peers are two important socializing agents whose need-supportive/thwarting practices have been strongly associated with students’ BPNs (Leenknecht et al., 2017; Ratelle et al., 2013). Need support from teachers refer to a set of pedagogical practices that include providing students with choices (autonomy), constructive and informational feedback (competence), and acknowledging their importance (relatedness). Need thwarting from teachers include the use of pressure and controlling tools to motivate students (autonomy), unclear and constantly changing instructions (competence), and an interpersonal attitude characterized by emotional coldness (relatedness). Need support from peers correspond to interpersonal behaviors that include openness to others’ opinion (autonomy), cooperating with others (competence), and being friendly and respectful (relatedness). Need thwarting from peers include manipulative and controlling behaviors (autonomy), a lack of cooperation and predictability (competence), and conflictual relationships (relatedness). More recently, Gilbert et al. (2021) proposed that need-supportive and need-thwarting characteristics related to study programs in college were also important predictors of students’ adjustment. They argued and demonstrated that need-related circumstances within study programs could impact students’ psychological adjustment beyond need-related practices emitted by teachers and peers. These various aspects derive from program committee orientations, and include, among others, a diversified offer of courses and ways to personalize the curriculum (autonomy), an easy access to important information regarding the program (competence), and a workload that does not encroach on students’ social life (relatedness) (Gilbert et al., 2021). Additional examples of need-supportive/thwarting practices from teachers, peers, and relative to study programs are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Need nurturing conditions within college

| Example(s) of Need-Related Practices | |

|---|---|

| Teachers | |

| Autonomy-Support | Letting students choose subject in assignment; Encouraging divergent opinions |

| Competence-Support | Course goals are stated clearly; Concrete tips help students improve their skills |

| Relatedness-Support | Appreciation and interest in students; Being understanding of students |

| Autonomy-Thwarting | Competition and other tools are used to control students; No rationale accompanying teachers’ requests |

| Competence-Thwarting | Course goals are constantly changing; No feedback is given to students |

| Relatedness-Thwarting | Relationships with students are disinterested; Teachers are unavailable for students |

| Peers | |

| Autonomy-Support | Students accept each other’s individuality; Students are open to others’ opinions |

| Competence-Support | Students are cooperative; Students help each other |

| Relatedness-Support | Students show understanding and respect; Students are interested in others |

| Autonomy-Thwarting | Students try to control others’ behaviors; Students try to manipulate others |

| Competence-Thwarting | Students' actions are not predictable; Students do not share important information with each other |

| Relatedness-Thwarting | Students don’t care about others; Students don’t get along well |

| Study Programs Climate | |

| Autonomy-Support | Many course options are available; Course relevance is explained |

| Competence-Support | Information on the study program is easily and quickly accessible; Information on the curriculum is clear |

| Relatedness-Support | Networking activities are encouraged and organized; Students get to know their teachers through organized events |

| Autonomy-Thwarting | Comments and suggestions for improvements are not welcome; Some mandatory courses are perceived as irrelevant |

| Competence-Thwarting | Information on the study program is confusing; No pedagogical support is offered to students |

| Relatedness-Thwarting | The workload impairs social life; Networking is not encouraged and seen as a waste of time |

Globally, need-nurturing conditions in students’ college experience, defined as high need support and low need thwarting from teachers, peers, and relative to study programs, should predict students’ experiences of need satisfaction and frustration in this context. In turn, these need-based experiences should influence college students’ mental health and lifestyle, especially through their purported impact on self-control abilities. This suggests that BPNs and self-control could represent important intervening factors in the frequent onset of psychological distress and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors observed in students during their first year in college. To the best of our knowledge, this whole theoretical sequence from need-supportive conditions to students’ health-related functioning, through need satisfaction and self-control, has not been tested in previous studies.

The present study

The general objective of this study was to examine whether BPNs and self-control represent intervening factors in the association between college educational climate and students’ psychological distress and health behaviors. To reach this objective, we pursued three specific goals illustrated in Fig. 1. First, this study aimed at precisely documenting students’ experiences of need satisfaction and frustration across one year of college education, starting from their first semester. To do so, we relied on latent profile analysis (LPA) to identify homogeneous subgroups (or profiles) of students sharing similar levels of BPN satisfaction and frustration. We also relied on latent transition analysis (LTA) to assess the evolution and stability of these profiles across the two measurement occasions. These person-centered analyses were selected because they allow the identification of subpopulations of students exhibiting varying configurations of need satisfaction and frustration. In doing so, they help capture the inter-individual and developmental heterogeneity at play in college students’ need-based experiences, which is not the case of variable-centered analyses that assume these experiences, and their evolution over time, to be similar for all members of the population (Morin & Litalien, 2019). Moreover, BPN profiles can be estimated using all six facets of need satisfaction and frustration, thus providing an encompassing portrait of students need-based experiences. In contrast, it is practically impossible to estimate simultaneously all six facets of need satisfaction and frustration in more common variable-centered analyses due to issues with multicollinearity (Tóth-Király et al., 2020). To date, only one study relied on a combination of LPA and LTA to assess profiles of BPNs among first-year college students (Gillet et al., 2020). However, this study took place over the course of one semester, focusing on a shorter span of their longitudinal evolution. It also did not include a measure of need frustration, providing an incomplete portrait of students’ need-based experiences.

Fig. 1.

Graphical representation of study objectives and hypotheses

Second, this study aimed at documenting the role of need-nurturing conditions within college in predicting students’ experiences of need satisfaction and frustration. This was achieved by assessing how general levels of need-nurturing practices (i.e., high need support, low need thwarting) emitted by teachers, peers, and relative to study programs, predicted the likelihood of membership into the various BPN profiles identified through LPA. With this regard, we assessed the prediction of the likelihood of membership to the various profiles at the first (Time 1; T1) and second (Time 2; T2) measurement occasion. For this specific objective, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: At T1 and T2, high need support and low need thwarting from each source (teachers, peers, and study programs) will predict increased likelihood of membership into more adaptive profile(s), characterized by higher levels of need satisfaction and lower levels of need frustration.

Lastly, this study aimed at examining the possible explanatory role of self-control in the association between students need-based experiences in college and negative outcomes of psychological distress and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors. This goal was achieved through two statistical approaches. First, we systematically assessed the relationship between each BPN profile identified through LPA and students’ self-control and other outcomes (i.e., anxiety, depression, physical activity, and fruit and vegetable consumption). Second, a follow-up variable-centered analysis was computed to test whether self-control mediated the associations between students’ BPNs and their psychological distress and health behaviors. For this specific objective, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a (person-centered approach): At T1 and T2, profiles characterized by higher levels of need satisfaction and lower levels of need frustration will predict more adaptive functioning in students (i.e., higher self-control, lower levels of psychological distress and more frequent health behaviors).

Hypothesis 2b (variable-centered approach): Self-control (at T1) will mediate the longitudinal association between students’ BPNs at T1 and their psychological distress and health behaviors at T2.

Method

Procedure and participants

After receiving ERB approval, we collected two waves of data, 12 months apart, in two large Canadian French-speaking universities. The first wave of data was collected during the fall semester of 2019. We sent an email to the entire population of first-year undergraduate students registered in disciplinary baccalaureates2 (N = 12,153). Of all these students, 1783 (participation rate: 14.67%; female = 79.8%, M age = 21.58, SD age = 4.95) completed at least one scale of the online questionnaire containing measures of need support/thwarting, need satisfaction/frustration, self-control, psychological distress, and health behaviors. The second wave of data was collected online during the fall semester of 2020 (i.e., 12 months later). We contacted the same group of 12,153 students of which 1053 (participation rate: 8.66%; female = 77.6%, M age = 22.60, SD age = 4.71) completed at least one scale of the online questionnaire at that point. Participation in the project was voluntary and completely anonymous at both measurement occasions, meaning that we had no contact information for participants at T1. A special code generated from four simple questions to students (e.g., month of birth, first two digits of home address) helped identify and merge data of those who answered at both time points. As a drawback, this did not allow for targeted communication at T2 to participants who initially answered at T1 but whose responses were missing (only general reminders were sent). Due to this procedure, while several participants answered at both time points (N = 386), collected data had some participants who only answered at T1 (N = 1397) and others who only answered at T2 (N = 667).

Measures

Need support and need thwarting

To assess participants’ perception of need-supportive and need-thwarting practices emitted by their teachers, peers, and relative to their study program, we used the French version of the College Need Support/Thwarting Questionnaire (CNSTQ; Gilbert et al., 2021). This questionnaire was developed in French and specifically assesses need support and need thwarting from three sources in the college context. The CNSTQ contains 72 items divided into 18 subscales, each one focusing on one of the three sources, on one of the three BPNs, and on one of the two directions (support vs. thwarting). Following a stem indicating “In my study program…”, participants completed items such as " Teachers encourage students to work their own way " (autonomy support by teachers), "My classmates are not interested in hearing about my difficulties or problems" (relatedness thwarting by peers) and "When students wonder about the content of their education, they easily find answers to their questions" (competence support by study programs). The items were answered on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (completely false) to 7 (completely true). In this study, instead of using 18 variables to reflect all subscales of the CNSTQ, each of the three sources of need support and thwarting was represented by one variable reflecting its general levels of need-nurturing practices (see Section 1 of the online supplements for more details on the estimation of these variables). Omega coefficients of composite reliability (McDonald, 1970) for these three general factors were adequate, ranging from 0.94 to 0.97 (Mω = 0.96) at T1, and from 0.95 to 0.97 (Mω = 0.96) at T2.

Need satisfaction and need frustration

We assessed participants’ BPN satisfaction and frustration with the French version (Chevrier & Lannegrand, 2021) of the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (BPNSFS; Chen et al., 2014). Made of 24 items, this scale is divided into six subscales: one subscale for the satisfaction and the frustration of each basic need. Following a stem indicating “In general in college…”, participants answered items such as "I feel forced to do many things I wouldn’t choose to do" (autonomy frustration), "I feel capable at what I do" (competence satisfaction) and "I feel connected with people who care for me, and for whom I care" (relatedness satisfaction). Items were answered on a 7-point scale (1 = completely false to 7 = completely true). Omega coefficients for the six subscales of the BPNSFS ranged from 0.84 to 0.94 (Mω = 0.85) at T1 and from 0.84 to 0.94 (Mω = 0.89) at T2.

Self-control

We used the French version (Brevers et al., 2017) of the Brief Self-control Scale (BSCS; Tangney et al., 2004) to assess participants trait self-control. This 13-item unidimensional scale captures the ability of each participant to resist short-term temptations and reach important long-term goals. Out of the 13 items of the BSCS, nine negatively worded items were reverse coded to obtain a homogeneous and positive score of self-control. Examples items for this scale include "I often act without thinking through all the alternatives" and "Pleasure and fun sometimes keep me from getting work done". Participants were asked to indicate how strongly they agreed with each item using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Omega coefficients for this scale were 0.85 at T1 and 0.86 at T2.

Psychological distress

Psychological distress was assessed using a combination of measures of anxiety and depression. To measure participants’ anxious symptoms, we relied on the French version (Micoulaud-Franchi et al., 2016) of the General Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006). This scale allows the detection of symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder. Participants were asked to rate how often they were bothered by symptoms of anxiety over the last 14 days using a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Omega coefficients for the GAD-7 in this study were 0.91 at both T1 and T2. To measure participants’ level of depressive symptoms, we used the French version (Carballeira et al., 2007) of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001). With nine items, this scale detects symptoms of major depression. Participants were asked to rate how often they struggled with depressive symptoms over the last 14 days (0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day). For this scale, we obtained omega coefficients of 0.86 at T1 and 0.88 at T2.

Health behaviors

Finally, we assessed participants’ health behaviors with items derived from surveys used by the governments of Quebec (provincial level) and Canada (federal level) as part of provincial and national population health assessments (Institut de la statistique du Québec, 2016; Statistics Canada, 2021). More precisely, we used one item to assess the weekly frequency of physical activity (i.e., sports, fitness, or recreational physical activities), and two items to assess the daily frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption. For each item, we asked participants to rate how often they practiced each health behavior in the past four weeks. Two response scales were used, a 1 (never) to 8 (7 or more times per week) scale for physical activity, and a 1 (never) to 9 (4 to 6 times per day) scale for fruit and vegetable consumption. A score representing the average fruit and vegetable consumption of each participant was calculated and used in the analyses.

Analyses

Latent profile analysis (LPA) and latent transition analysis (LTA) were conducted with the robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimator in Mplus 8.5 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Given the objective of assessing the over time stability of need satisfaction and frustration profiles, the LPA and LTA models were estimated using only the participants who responded to both time points (N = 386). Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) was used to handle missing data within those participants who answered at both time points (% missing values: 13.13%; Enders, 2010). To avoid local maxima, all LPA were conducted with 5000 random sets of start values, 1000 iterations per start values, and we retained the 200 best solutions for final stage optimization (Gillet et al., 2017). For the longitudinal models, random sets of start values were increased to 10,000, and the 500 best solutions were retained for final stage optimization (Morin & Litalien, 2017).

We first started by estimating LPA models separately at each time point (T1 and T2) using three factors of need satisfaction and three factors of need frustration as profile indicators (see Section 1 of the online supplements for more information on these factors). This was done to control the extraction of an equal number of profiles at each time point. Given the scarcity of research using LPA and LTA to identify profiles of need satisfaction and frustration among college students, we did not specify any hypothesis about the nature, number, and stability of expected profiles. However, in line with past person-centered research (e.g., Gillet et al., 2020; Huyghebaert-Zouaghi et al., 2020; Tóth-Király et al., 2020), we expected that a relatively small number of profiles (i.e., between two and five profiles) would be identified. Therefore, we examined solutions including 1 to 6 latent profiles at T1 and T2. Beyond the theoretical meaningfulness of each tested solution, the optimal number of profiles was selected using multiple statistical indices (Morin & Litalien, 2019): the Akaïke Information Criterion (AIC), the Consistent AIC (CAIC), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the sample-size Adjusted BIC (ABIC), the Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT), and the adjusted standard Lo et al. (2001) Likelihood Ratio Tests (aLMR). Models with higher fit to the data are the ones with lower AIC, CAIC, BIC, and ABIC values while significant BLRT and/or aLMR suggest that a k-profile solution should be retained at the expense of a k – 1-profile solution. Finally, entropy indicates the precision of participants’ classification into the various profiles. Although entropy should not be considered in the process of selecting the optimal solution (Lubke & Muthén, 2007), it provides useful information on classification accuracy, with values closer to 1 indicating a more accurate solution.

After selecting the optimal number of profiles at both T1 and T2, we integrated the two retained LPA solutions into a single longitudinal LPA model to assess their longitudinal similarity (longitudinal similarity can be compared to longitudinal invariance in factor analysis). More specifically, we assessed the configural (number of profiles), structural (mean of indicators), dispersion (variance of indicators), and distributional (size of profiles) similarity of these two solutions across time points (Morin & Litalien, 2017). On the premise that one form of similarity was satisfactory, the next one in the sequence was evaluated, each time integrating more equality constraints into the longitudinal LPA model. In that regard, the same statistical indices as previously mentioned were used to evaluate the fit of each model across the similarity sequence (i.e., AIC, CAIC, BIC, and ABIC), with lower values on at least two of these indices in a more constrained model indicating profile similarity (Morin et al., 2016). Then, the model with the highest time-lagged similarity from this sequence was converted into a final LTA model which allowed the investigation of within-person stability and transitions in profile membership across time (Morin & Litalien, 2019).

Predictors of profile membership

Next, we included predictors into the final LTA model. We conducted multinomial logistic regression analyses to verify whether general levels of need nurturing (i.e., high need support, low need thwarting) from teachers, peers, and relative to study programs were predictive of the likelihood of membership into the various profiles at T1 and T2. As done in Gillet et al. (2017), three models helped identify whether the predictors explained profile membership within and across time points. In a first model [transition model], we estimated the associations between the predictors and profile membership freely at both times, predicting the membership to the various profiles within a time point. In this first model, the prediction of profile membership at T2 was further differentially evaluated as a function of participants’ profile membership at T1, predicting the membership of T2 profiles for members of each T1 profile independently. In a second model [no-transition model], we estimated the associations between the predictors and profile membership freely within time points (T1 antecedents predicting T1 profile membership, and T2 antecedents predicting T2 profile membership), but not differentially as a function of T1 profile membership. Finally, a third model [predictive similarity] estimated the similarity of the within-time-point profile membership predictions by the antecedents by constraining their equality for the two time points. A better-fitting no-transition model over a transition model would imply no significant prediction of transitions by antecedents. A better-fitting predictive similarity model over other models would imply invariance of profile membership prediction by antecedents over time.

Students’ basic psychological needs and outcomes

Latent profile and transition analyses

Regarding the role of students’ BPNs in predicting important outcomes, we started by assessing the links between students’ profiles of need satisfaction and frustration and students’ self-control, psychological distress (anxiety, depression), and health behaviors (physical activity, fruit and vegetable consumption). These outcomes were incorporated into the final LTA model using the MODEL CONSTRAINT command of Mplus paired with the multivariate delta method (Kam et al., 2016) to test for mean-level differences across profiles and time points. As recommended by Morin and Litalien (2017), we then tested for explanatory similarity by testing and comparing a model in which within-profile means of the outcomes were constrained to equality across time points, to a model with no such constraints.

Structural equation modeling

Finally, using structural equation modeling (SEM), we analyzed a model with the MLR estimator available in Mplus 8.5 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) where BPNs (T1) predicted self-control (T1) which, in turn, predicted psychological distress (T2) and health behaviors (T2). This model also included a direct prediction of psychological distress (T2) and health behaviors (T2) by BPNs (T1). This model was autoregressive as we controlled for T1 levels of T2 outcomes, which were also allowed to correlate. For parsimony and to reduce collinearity, we focused on general levels of need satisfaction and frustration in students rather than specifying satisfaction and frustration variables for each need (see Section 1 of the online supplements for more details on these general factors). In order to examine whether the effects of need satisfaction and frustration at T1 on students’ health-related outcomes at T2 were mediated by self-control at T1, we conducted a mediation analysis using the bootstrap methodology (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

For the variable-centered analyses, we estimated a model (Model 1) with data from all respondents (T1: N = 1783, T2: N = 1053), rather than proceeding with listwise deletion, using FIML to handle missing data (Enders, 2010). In longitudinal variable-centered studies, FIML paired with MLR has been found to yield the most unbiased parameter estimates when respondents miss one or multiple time points, even in the case of very high levels of missing data, when missing at random assumptions are mostly respected (Enders, 2001, 2010; Enders & Bandalos, 2001; Graham, 2009; Larsen, 2011; Shin et al., 2009). The combination of FIML and MLR estimation was found to perform better than other strategies (e.g., listwise deletion, pairwise deletion, mean substitution). However, to ensure that the obtained results were unbiased by this decision, two other prediction models were estimated using two different configurations of respondents. A second model (Model 2) was estimated using all T1 respondents (N = 1783) paired with T2 respondents who participated in T1 (N = 386). Lastly, a third model (Model 3) was estimated using only the respondents who answered both time points (N = 386). In all cases, model fit was assessed with the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), with CFI and TLI values ≥ 0.95 or 0.90, and RMSEA and SRMR values ≤ 0.06 or 0.08 respectively used to indicate excellent and acceptable levels of fit to the data (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Marsh et al., 2005).

Results

Preliminary analyses

Before proceeding with the main analyses, factorial analyses (bifactor-exploratory structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis) were conducted to assess the structure of all measures used in this study, apart from that of health behaviors which are each represented by one item only. The results from these measurement models supported factor validity and reliability. Moreover, longitudinal measurement invariance for measures used in defining and predicting profiles (i.e., BPNs and need-nurturing practices) was also tested and supported. Details on the estimation of all preliminary measurement models and results from the tests of longitudinal measurement invariance are reported in the online supplements (see Sections 1 and 2). Factor scores estimated in standardized units (M = 0, SD = 1) were saved from these preliminary (and longitudinally invariant) measurement models and used as inputs for the person- and variable-centered analyses (for a detailed discussion on the advantages of factor scores, see Guay et al., 2021; Morin et al., 2016). Correlations among the variables included in the study are reported in Table S2 of the online supplements. Finally, results from MANOVA showed no significant differences in the included variables (i.e., need support by teachers/peers/study programs, need satisfaction/frustration, self-control, anxiety, depression, physical activity, fruit and vegetable consumption) between participants assessed at both measurement times (T1 and T2) versus T1 only (main effect; F [9, 1312] = 1.819, p = 0.061; Wilk’s Λ = 0.988).

Latent profile solution

Fit indices for LPA optimization at each time point are presented in Table S3 of the online supplements. These fit indices are also depicted in Figure S1 and S2 of these supplements in the form of elbow plots. The results revealed improvements on the AIC, CAIC, BIC, and ABIC as well as significant BLRTs as the number of profiles increased. However, the aLMR difference test indicated, at both T1 and T2, that the 4- (and 5-) profile solution did not provide a better estimation of the within combination of need satisfaction and frustration indicators compared to a 3- (and 4-) profile solution. Moreover, at both time points, the 4- and 5-profile solutions contained profiles regrouping less than 5% of the sample, meaning that these solutions did not result in the addition of well defined and meaningful profiles over the 3-profile solution (Modecki et al., 2015). The 3-profile solution was thus retained across time points. The fit indices from this final solution at T1 and T2 and for all further longitudinal models are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results from the latent profile analyses and latent transition analyses

| 3-Profile Solution | LL | #fp | SC | AIC | CAIC | BIC | ABIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final latent profile analyses | |||||||

| Time 1 | -2745.004 | 26 | 1.34 | 5542.009 | 5669.406 | 5643.406 | 5560.919 |

| Time 2 | -2714.061 | 26 | 1.45 | 5480.122 | 5607.519 | 5581.519 | 5499.032 |

| Longitudinal latent profile analyses | |||||||

| Configural similarity | -5243.025 | 76 | 1.33 | 10,638.050 | 11,010.442 | 10,934.442 | 10,693.325 |

| Structural similarity | -5255.281 | 58 | 1.58 | 10,626.561 | 10,910.755 | 10,852.755 | 10,668.745 |

| Dispersion similarity | -5262.288 | 40 | 1.95 | 10,604.575 | 10,800.571 | 10,760.571 | 10,633.667 |

| Distributional similarity | -5262.329 | 38 | 2.00 | 10,600.657 | 10,786.853 | 10,748.853 | 10,628.295 |

| Final Latent Transition Analysis | -5274.340 | 54 | 1.13 | 10,656.680 | 10,921.275 | 10,867.275 | 10,695.955 |

| Predictive similarity | |||||||

| Profile-specific free relations with predictors | -5205.027 | 34 | 0.83 | 10,478.053 | 10,644.557 | 10,610.557 | 10,502.689 |

| Free relations with predictors | -5212.463 | 16 | 1.02 | 10,456.925 | 10,535.280 | 10,519.280 | 10,468.519 |

| Equal relations with predictors | -5214.693 | 10 | 1.10 | 10,449.387 | 10,498.358 | 10,488.358 | 10,456.632 |

| Explanatory similarity | |||||||

| Free relations with outcomes | -9534.027 | 44 | 1.04 | 19,156.053 | 19,371.769 | 19,327.769 | 19,188.175 |

| Equal relations with outcomes | -9553.652 | 29 | 1.21 | 19,165.305 | 19,307.481 | 19,278.481 | 19,186.475 |

LL = Model LogLikelihood; #fp = Number of free parameters; SC = Scaling factor associated with MLR loglikelihood estimates; AIC = Akaïke Information Criteria; CAIC = Constant AIC; BIC = Bayesian Information Criteria; ABIC = Sample-Size adjusted BIC

Next, we explored the similarity of the 3-profile solutions obtained at both time points, starting by estimating a model of configural similarity in which the number of profiles was constrained at equality across time points. This model was then contrasted to a model of structural similarity (constraining the within-profile means of the six BPN indicators to be equal across time points) which was in turn contrasted to a model of dispersion similarity (constraining the within-profile variance of the six BPN indicators to be equal across time points). Finally, the dispersion model was contrasted to a model of distributional similarity (constraining the class probabilities to be equal across time points). Each model of similarity exhibited lower values on at least two statistical indices compared to the previous model of similarity in the sequence (see Table 2). Thus, the structural, dispersion, and distributional similarity of the 3-profile solution across time points were supported. As the most similar model, the distributional similarity model was retained for interpretation and for further analyses. This model is illustrated in Fig. 2 (the exact within-profile means are presented in Table S4 of the online supplements).

Fig. 2.

Final 3-Profile solution selected at both time points. Note. The profile indicators are estimated from factor scores with mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Profile 1 = High need satisfaction; Profile 2 = Average need satisfaction; Profile 3 = Need frustration

Profile 1 presents higher-than-average levels of need satisfaction and lower-than-average levels of need frustration.3 More specifically, this profile is characterized by high levels of competence and autonomy satisfaction and moderately high levels of relatedness satisfaction. This profile is also characterized by low levels of need frustration, which is particularly pronounced for the competence need, respectively followed by the autonomy and relatedness needs. This profile was labeled “High need satisfaction” and includes 25.04% of the sample. Profile 2 is characterized by average levels of autonomy and competence satisfaction and frustration, moderately high levels of relatedness satisfaction, and moderately low levels of relatedness frustration. This profile was labeled “Average need satisfaction” and regroups 45.34% of the sample. Lastly, Profile 3 displays higher-than-average levels of need frustration and lower-than-average levels of need satisfaction. In this profile, the need for competence appears to be particularly frustrated followed by the need for relatedness and the need for autonomy, respectively. This profile was labeled “Need frustration” and includes 29.62% of the sample.

Latent transitions

The final model of distributional similarity was then converted to a final LTA model using the manual auxiliary 3-step approach (Morin & Litalien, 2017). The latent transition probabilities, which reflect stability of profile membership over time, are reported in Table 3. The Average need satisfaction profile is the most stable (stability of 68.5%) followed by the High need satisfaction (stability of 66.8%) and Need frustration (stability of 29.6%) profiles. Regarding the transitions that occurred between T1 and T2, 25.9% of students that were in the High need satisfaction profile at T1 switched to the Average need satisfaction profile, and 7.3% to the Need frustration profile. Next, 15% of students that were in the Average need satisfaction profile at T1 transitioned to the High need satisfaction profile, and 16.5% to the Need frustration profile. Lastly, 25% of students that were in the Need frustration profile at T1 switched to the High need satisfaction profile, and 45.3% to the Average need satisfaction profile. Overall, these results suggest that profile membership is quite volatile over time, particularly for the initial Need frustration profile.

Table 3.

Latent transition probabilities of profiles across time

| Probability of Transition to… | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| T2 Profile 1 | T2 Profile 2 | T2 Profile 3 | |

| T1 Profile 1 | .668 | .259 | .073 |

| T1 Profile 2 | .150 | .685 | .165 |

| T1 Profile 3 | .250 | .453 | .296 |

Profile 1 = High need satisfaction; Profile 2 = Average need satisfaction; Profile 3 = Need frustration; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2

Predictors of profile membership

General levels of need-supportive practices from teachers, peers, and study programs were added as predictors to the final LTA model of distributional similarity. We estimated and contrasted three models: a transition model, a no-transition model, and a predictive similarity model. As shown in Table 2, the model of predictive similarity exhibited lower AIC, CAIC, BIC, and ABIC values than the other two models, meaning that the results supported the equivalence of the predictions across time points, and therefore the absence of significant associations between each predictor and specific profile transitions (Morin & Litalien, 2019).

The results from the model of predictive similarity are presented in Table 4. The obtained multinomial regression statistics reflect the likelihood of belonging to a target profile versus a comparison one (the target profile always represents higher levels of need satisfaction than the comparison profile). To facilitate the interpretation of the regression coefficients, they are provided in conjunction with odds ratios (ORs). ORs reflect changes in the likelihood of belonging to the target profile versus the comparison one for each unit increase in the predictor. ORs above 1 indicate that the likelihood of membership in the target profile is increased whereas ORs under 1 indicate that the likelihood of membership in the target profile is reduced.

Table 4.

Results from multinomial logistic regressions for the effects of the predictors on profile membership

| High Need Satisfaction (1) Versus Average Need Satisfaction (2) |

High Need Satisfaction (1) Versus Need Frustration (3) |

Average Need Satisfaction (2) Versus Need Frustration (3) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (SE) | OR | Coefficient (SE) | OR | Coefficient (SE) | OR | |

| General Levels of Need-Support | ||||||

| Teachers | -.043 (.198) | 0.958 | .147 (.184) | 1.158 | .197 (.142) | 1.218 |

| Peers | .000 (.172) | 1.000 | .909 (.155)** | 2.481 | .661 (.132)** | 1.937 |

| Study programs | .778 (.205)** | 2.179 | 1.241 (.208)** | 3.460 | .481 (.150)** | 1.618 |

SE = Standard error; OR = Odds ratio. The coefficients and OR reflect the effects of the predictors on the likelihood of membership into the first listed profile relative to the second-listed profile

* p < .05. ** p < .01

Inspection of Table 4 reveals multiple statistically significant associations between the predictors and profile membership. First, need-supportive practices from peers and study programs predicted an increased likelihood of membership into the High need satisfaction profile relative to the Need frustration profile. Need-supportive practices from these two sources also predicted an increased likelihood of membership into the Average need satisfaction profile relative to the Need frustration profile. Lastly, only need-supportive practices from study programs predicted an increased likelihood of membership into the High need satisfaction profile relative to the Average need satisfaction profile. No significant results were observed for need support by teachers. In terms of ORs, students perceiving high levels of need support from their study program were 2.179 times more likely to be in the High need satisfaction profile relative to the Average need satisfaction profile (OR for teachers: 0.958; OR for peers: 1), 3.460 times more likely to be in High need satisfaction profile relative to the Need frustration profile (OR for teachers: 1.158; OR for peers: 2.481), and 1.618 times more likely to be in the Average need satisfaction profile relative to the Need frustration profile (OR for teachers: 1.218; OR for peers: 1.937). Globally, these results partially support Hypothesis 1 by showing that the social and educational conditions within college, as defined by need support from peers and relative to study programs, predict high levels of need satisfaction and low levels of need frustration in students.

Students’ psychological needs and outcomes

Latent profile and transition analyses

Outcomes were added to the final LTA model of distributional similarity. To test for explanatory similarity, we contrasted a model in which the outcomes levels were freely estimated across time points to a model in which these levels were constrained to equality across time points. As shown in Table 2, the explanatory similarity was supported as the more constrained model resulted in lower CAIC, BIC, and ABIC values (Morin & Litalien, 2019). The within-profile means (and 95% confidence intervals) of each outcome are presented in Table 5 and depicted in Fig. 3. These results emphasize the distinct nature of each profile as many significant differences between profiles emerged. First, students with membership to the High need satisfaction profile presented higher levels of self-control and lower levels of anxiety and depression relative to the two other profiles. The Average need satisfaction profile was also characterized by higher self-control and lower psychological distress compared to the Need frustration profile. In terms of physical activity, the results showed that students in the High need satisfaction profile tended to be more physically active than those in the Average need satisfaction and Need frustration profiles. However, no differences were observed between students from the latter two. Moreover, students from the High need satisfaction and Average need satisfaction profiles tended to eat more fruits and vegetables than those in the Need frustration profile, but no differences emerged between the two profiles characterized by more need satisfaction. Overall, these results highlight that more need satisfaction and less need frustration co-occur with high self-control, low levels of psychological distress and healthier lifestyle behaviors. These results support Hypothesis 2a.

Table 5.

Time-invariant associations between profile membership and the outcomes

| High need satisfaction (1) | Average need satisfaction (2) | Need frustration (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean [CI] | Mean [CI] | Mean [CI] | |

| Self-Control (1 to 5) | 3.765a [3.654; 3.876] | 3.292b [3.212; 3.373] | 2.870c [2.768; 2.971] |

| Anxiety (0 to 3) | 0.752a [0.635; 0.870] | 1.296b [1.191; 1.401] | 1.803c [1.659; 1.946] |

| Depression (0 to 3) | 0.644a [0.559; 0.729] | 1.116b [1.037; 1.196] | 1.679c [1.568; 1.790] |

| Physical Activity (1 to 8) | 2.944a [2.644; 3.244] | 2.454b [2.262; 2.647] | 2.334b [2.070; 2.599] |

| Fruit & Vegetable (1 to 9) | 6.938a [6.682; 7.194] | 6.896a [6.721; 7.071] | 6.463b [6.222; 6.704] |

The within-profile means presented in this table are not standardized. Means who share the same letter are not significantly different. CI = 95% Confidence Interval

Fig. 3.

Associations between profile membership and the outcomes (equal across time). Note. For purpose of clarity, the within-profile mean of each outcome was standardized before being graphically illustrated. Profile 1 = High need satisfaction; Profile 2 = Average need satisfaction; Profile 3 = Need frustration

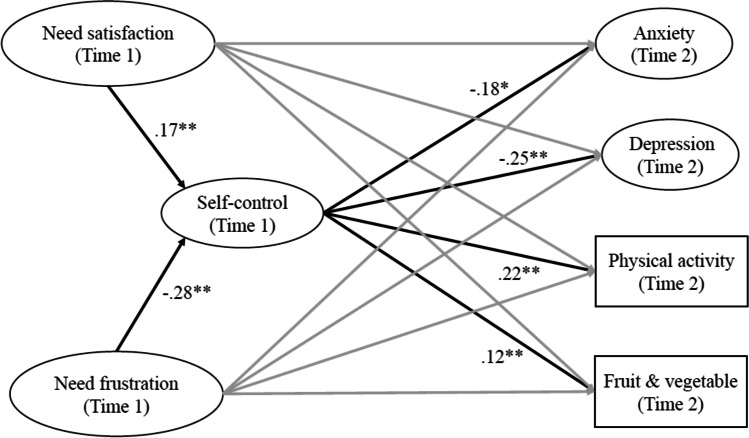

Structural equation modeling

The results from Model 1 are summarized in Fig. 4 and presented in Table S5 of the online supplements. These results, which supported the fit of this model, showed that need satisfaction and need frustration were respectively positive and negative predictors of students’ self-control abilities at T1. In turn, self-control significantly predicted lower levels of anxious and depressive symptoms as well as more frequent physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption at T2. Once self-control was taken into account, need satisfaction and need frustration were not significant predictors of students’ psychological distress and health behaviors at T2 (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Results from the autoregressive prediction model tested in the variable-centered analyses. Note. Model fit: χ.2(13) = 46.893, p < .01, CFI = 0.975, TLI = 0.922, RMSEA = 0.037; SRMR = 0.032. Gray paths are not statistically significant. Correlation paths between predictors and those between outcomes are not shown for the sake of simplicity. Time 1 outcomes and their paths towards their Time 2 counterparts are not illustrated for the same reason. Ovals represent factor scores, and rectangles represent observed indicators. * p < .05. ** p < .01

To ensure the validity of these results, two alternative models (Models 2 and 3) were estimated using different sample sizes. Model 2 was estimated using all T1 respondents (N = 1783) paired with T2 respondents who participated in T1 (N = 386) while Model 3 was estimated using only the respondents who answered both time points (N = 386). The results of these models, which are presented in Table S5 of the online supplements, were closely similar to those of Model 1 in terms of fit indices, regression paths, and confidence intervals. This suggests that Model 1 was as precise in estimation as Models 2 and 3 despite missing data proportions (Kelley & Rausch, 2006). Based on these observations, we selected Model 1 for the mediation analysis. Using 5000 bootstrapping resamples, this mediation analysis revealed small but significant indirect effects through self-control for need satisfaction at T1 to anxiety (β = -0.031, SE = 0.012, bias corrected [BC] 95% CI [-0.047; -0.007]), depression (β = -0.043, SE = 0.014, BC 95% CI [-0.052; -0.012]), physical activity (β = 0.036, SE = 0.012, BC 95% CI [0.013; 0.065]), and fruit and vegetable consumption (β = 0.020, SE = 0.009, BC 95% CI [0.002; 0.042]) at T2. Similarly, small but significant indirect effects through self-control were also obtained for need frustration at T1 to anxiety (β = 0.051, SE = 0.017, BC 95% CI [0.016; 0.075]), depression (β = 0.071, SE = 0.018, BC 95% CI [0.028; 0.081]), physical activity (β = -0.060, SE = 0.017, BC 95% CI [-0.102; -0.030]), and fruit and vegetable consumption (β = -0.034, SE = 0.014, BC 95% CI [-0.067; -0.008]) at T2. Overall, these results support Hypothesis 2b by demonstrating that self-control mediates the relationship between need satisfaction and frustration and students’ psychological distress and health behaviors.

Discussion

Through a refined understanding of the processes through which psychological distress and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors occur among college students, this study aimed at better documenting the onset of these highly prevalent negative experiences during the first year in college. More precisely, we emphasized students’ BPNs and self-control abilities as intervening factors linking college educational climate to students’ psychological distress (anxiety, depression), and health behaviors (physical activity, fruit and vegetable consumption). Ultimately, we highlight a process by which factors related to the educational context can influence students’ health-related functioning.

Profiles of need satisfaction and frustration in college

Three distinct profiles best represented the configurations of BPN satisfaction and frustration among our sample of students during their first year of college. First, the High need satisfaction profile was characterized by high levels of need satisfaction and low levels of need frustration. More precisely, this profile was marked by particularly higher-than-average levels of competence and autonomy satisfaction relatively to relatedness satisfaction, and by particularly lower-than-average levels of competence frustration relatively to autonomy and relatedness frustration. Therefore, students belonging to this profile generally associate their experiences in college with a sense of mastery and effectiveness (competence satisfaction), and volition and freedom (autonomy satisfaction), while also feeling connected with important others (relatedness satisfaction). Next, the Average need satisfaction profile was characterized by average levels of autonomy (satisfaction and frustration) and competence (satisfaction and frustration), and by slightly above-average levels of relatedness satisfaction and below-average levels of relatedness frustration. Interestingly, the levels of relatedness satisfaction in this profile were similar to those in the High need satisfaction profile. Lastly, the Need frustration profile was characterized by high levels of frustration and low levels of satisfaction on all three BPNs and showed particularly high levels of competence frustration. Students belonging to this profile are those who seriously doubt their ability to succeed (competence frustration), feel pressured to act in certain ways (autonomy frustration) and feel rejected from important others (relatedness frustration) in college.

Interestingly, the number of profiles obtained in this study (i.e., three) differ from the number of profiles obtained in previous LPA research. Indeed, Gillet et al. (2020) demonstrated that a five-profile solution best represented college students’ experiences of need satisfaction while Reed-Fitzke and Lucier-Greer (2020) showed that a two-profile solution was optimal. Although these varying results could be due to both cultural and methodological differences (e.g., sample size and composition, estimating profiles with composite scores vs. factor scores, measuring need satisfaction vs. need satisfaction and frustration), this level of inconsistency pinpoints the need for additional research using LPA to assess BPN profiles among college students.

However, contrary to most studies, we adopted a prospective design that allowed us to assess the within-sample and within-person stability of each profile over the course of a college year. Regarding the within-sample stability, our results demonstrated that the 3-profile solution obtained at T1 was replicated at T2, thus supporting the generalizability of this solution. Indeed, we obtained the same number of profiles (configural similarity), similar within-profile levels of need satisfaction and frustration (structural similarity), similar within-profile variability in these levels (dispersion similarity), and similar profile size (distributional similarity) across time points. In terms of within-person stability, our results revealed that around 30% of the sample migrated from one profile to another over the course of the study. The majority of these transisions occurred among students who belonged at T1 to the Need frustration profile (stability of 29.6%). Conversly, membership to the High need satisfaction (stability of 66.8%) and Average need satisfaction (stability of 68.5%) profiles was more stable over time, although changes did occur in these profiles between T1 and T2. The general conclusion that can be drawn from these transitions is that each BPN profile reflects a set of experiences that are susceptible to change throughout students’ first years in college. However, the probability of students’ migrating from one profile to another appears to be partly related to the nature of their need-based experiences. Indeed, our results demonstrated that this probability is significantly lower when students perceive all of their BPNs to be satisfied (i.e., belonging to the High or Average need satisfaction profiles). Moreover, the probability of “downgrading” from the High or Average need satisfaction profiles to the Need frustration one was lower than the probability of “upgrading” from the former profile to either of the more adaptive profiles.

Interestingly, our results are different from those obtained by Gillet et al. (2020) who observed that profiles reflecting low levels of need satisfaction (i.e., need dissatisfaction) were more stable throughout the first college semester relatively to profiles reflecting high need satisfaction. This pattern of results might be partly explained by the fact that the transition to college involves notable changes related to students’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Indeed, college requires students to get used to an independent learning style that involves making their own decisions for learning goals, contents, and progression (Ding & Yu, 2021; Macaskill & Taylor, 2010). College is also accompanied by increased workload and new types of assessments and requirements. Becoming an autonomous learner and facing these academic demands requires students to develop new skills and refine the ones they already have (e.g., time management, note-taking, knowledge translation). Finally, college students are faced with the duty of social integration as they have to develop new relationships and integrate new peer groups (Kyndt et al., 2017). All of these changes require a great deal of coping that is likely to have major impacts on students’ BPNs during their first months of college, as observed by Gillet et al. (2020). However, our results suggest that many students (initially in the Need frustration profile) have successfully adapted to this new reality by the time they reached their second year of higher education. With this in mind, it is possible that the educational climate within college may facilitate this adaptation by promoting students’ need satisfaction and by preventing need frustration during the first year of college.

How need-nurturing conditions in college may help students

Having identified three profiles of need satisfaction and frustration, a key objective of this study was to examine the role of need-nurturing conditions in college in predicting students’ profile membership. To take into account the numerous facets that characterize the college educational climate, we measured need-supportive and need-thwarting practices from three sources: teachers, peers, and relative to study programs. Of these three sources of need support, only peers and study programs predicted an increased probability of membership into the Average need satisfaction profile relative to the Need frustration profile, and an increased probability of membership into the High need satisfaction profile relative to the Need frustration one. Interestingly, only need support from study programs predicted an increased likelihood of membership into the High need satisfaction profile relative to the Average need satisfaction profile. Noteworthy, these results appeared to be particularly robust as they were found to generalize across T1 and T2 (predictive similarity).

Altogether, these results demonstrate that need-thwarting conditions in college may lead students to experience high need frustration while need support in this context may foster high need satisfaction, which is aligned with Hypothesis 1. However, it appears that only need-supportive practices emitted by peers and relative to study programs are important in that matter and of the two, only need support relative to study programs can explain the difference between students with average vs. high levels of need satisfaction. Our findings underline that having need supportive peers and evolving in a need supportive study program strongly contributes to making the first year in college a highly satisfying experience. The importance of these two sources is not surprising. Indeed, higher education represents an important life stage during which college students seek to develop their social identity. This involves individuating from family members and, more importantly, developing new social relationships (Alsubaie et al., 2019). From a developmental perspective, it is thus important for students to feel positively connected to their social network in college. This might explain why peers, as a source of need support, were so important in predicting students profile membership.

Moreover, while students are exposed to many different teachers and peers throughout their studies, they are exposed to the same general orientations that characterize their study program (e.g., course options, clarity and access to curriculum information, workload). Because of their encompassing and permanent nature, Gilbert et al. (2021) proposed that these orientations will inevitably shape students’ experience of volition, effectiveness, and connectedness in college, even beyond need-supportive practices generally emitted by other sources (e.g., teachers and peers). Our results support this proposition by illustrating the importance of study program climate in fostering high levels of need satisfaction in students. Lastly, it is surprising that need support by teachers did not significantly predict students’ profile membership. Indeed, previous research has shown that teachers were an important determinant of students’ need-based experiences (e.g., Leenknecht et al., 2017; Sheldon & Krieger, 2007). However, compared to previous studies, we examined the concurrent prediction of need-based experiences by three different sources at the college level. We can thus only conclude that when peers and study programs are considered, the role played by teachers in fostering need satisfaction or need frustration in students is no longer noticeable. Overall, need-supportive conditions in college, as established by peers and, more particularly by study programs, are important determinants of students’ need satisfaction.

Associations of profile membership with students’ outcomes

Lastly, this study examined the contribution of students BPNs and self-control in the prediction of their health-related functioning (i.e., psychological distress, health behaviors). To reach this aim, we first started by assessing between-profile differences in terms of students’ self-control, anxiety, depression, physical activity, and fruit and vegetable consumption. In general, membership into the High need satisfaction profile was associated with the most positive outcomes, followed by membership into the Average need satisfaction profile, while membership into the Need frustration profile was associated with the most negative outcomes. More specifically, students belonging to the High need satisfaction profile reported higher levels of self-control, less psychological distress, and more frequent health behaviors than those from the other two profiles, although no differences emerged between the High and Average need satisfaction profiles regarding fruit and vegetable consumption. While students from the Need frustration profile exhibited the worst outcomes, physical activity frequency by those students did not differ from that of students belonging to the Average need satisfaction profile.

Globally, these results supported Hypothesis 2a by revealing that higher levels of need satisfaction and lower levels of need frustration are associated with greater self-control, lower psychological distress, and, overall, with healthier lifestyle behaviors. Importantly, this pattern of associations was invariant over the course of a college year (explanatory similarity), which suggests that students’ need-based experiences have immediate associations with their health-related functioning at any given point in their college experience.

A pattern of associations mediated by self-control

Interestingly, the pattern of associations described in the previous section illustrated that the relationship between students’ BPNs and health behaviors was not as linear as the relationships between students’ BPNs and other outcomes (self-control and psychological distress). This can be expected given that SDT does not assume a direct association between need satisfaction and frustration in the educational context and students’ general propensity to be physically active or eat healthy foods. Rather, need-based experiences are expected to influence one’s health behaviors through their purported impact on other variables, such as self-control (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013).

In line with previously-stated theoretical assumptions, our results confirmed that need frustration in students was linked to reduced self-control abilities while need satisfaction was associated with stronger reported self-control. In turn, self-control systematically predicted a higher frequency of physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption and lower levels of anxious and depressive symptoms 12 months later, at T2. Conversely, students’ need satisfaction and frustration at T1 did not directly predict students’ health-related functioning at T2. Rather, these longitudinal associations were mediated by self-control, which supported Hypothesis 2b. In sum, it appears that experiencing high need satisfaction and low need frustration in college might facilitate students’ self-regulatory capacities which, over time, reduce their propensity to be emotionally distressed and stuck in a pattern of unhealthy lifestyle behaviors.

Implications for practice

By highlighting the contribution of college educational climate in predicting students’ BPN profiles, and by demonstrating the importance of students’ BPNs for their health-related functioning, our study has several implications for faculty members, provosts, and teaching/learning centers. First, an important consideration should be given to study program climate. Numerous practices could be implemented or reinforced to ensure that study programs promote students’ need satisfaction. These practices include giving students access to sufficient (1) opportunities to shape their educational path in accordance with their interests and needs, (2) information regarding their curriculum and possible progression paths, and (3) pedagogical support services (Gilbert et al., 2021).

Being subject to a fair workload that promotes students’ academic and professional development without unnecessarily harming their life balance is another important factor to foster need satisfaction. Although workload in college can be thought of as a characteristic of study programs, it is in fact the sum of the requirements imbedded in each individual course for a given semester. These requirements are mostly under the responsibility of teachers who tend to work in silos when developing their courses. To tackle this issue and increase the coherence between each component of a specific study program, a program-approach was introduced in some institutions of higher education in the early 2000s (Basque, 2017). This approach consisted of ensuring a close and continuous communication between the actors involved in designing and implementing elements of the curriculum. For instance, when new courses are developed and incorporated into the curriculum, the primary concern is whether these courses will help students achieve their program-specific learning objectives (Sylvestre & Berthiaume, 2013). In other words, the contribution of each course to the whole curriculum is considered more important than the mere relevance of individual courses. In doing so, the program-approach fosters a more harmonious curriculum that support students’ learning integration throughout their studies without forcing the accumulation of scattered knowledge (Basque, 2017). In our view, relying on such an approach when designing or reviewing study programs could represent a way to stimulate students’ need satisfaction, especially by promoting a more balanced workload and reducing unnecessary repetitive study topics. Importantly, a more thorough reflection on how study programs support or thwart students’ BPNs could also be integrated in this approach.

Next, although students are themselves responsible for actively seeking and maintaining need-supportive relationships with their peers, colleges and their study programs are responsible for encouraging opportunities for students to meet each other. This can be done in several ways, including by organizing informal social activities or by establishing peer learning programs (Noyens et al., 2019). Teachers can also contribute to this effort by fostering students’ collaboration, relying on teaching methods such as collaborative learning and problem- or project-based learning (Dillenbourg, 1999). These methods have been shown to be efficient in promoting first-year college students academic and social integration (Tinto, 1975, 2012). They can thus help make the classroom a nurturing environment for students’ relatedness (Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005) and provide them with invaluable opportunities to develop supportive relationships with their peers. Professional development programs intended to help teachers master such need-supportive practices have been developed in past studies (e.g., Guay et al., 2020) and could be implemented in colleges and universities (by their teaching and learning centres, for instance).

Limitations and future directions

The COVID-19 pandemic