Abstract

Background and aims

Play-based interventions are used ubiquitously with children with social, communication, and language needs but the impact of these interventions on the mental health of this group of children is unknown. Despite their pre-existing challenges, the mental health of children with developmental language disorder (DLD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) should be given equal consideration to the other more salient features of their condition. To this aim, a systematic literature review with meta-analysis was undertaken to assess the impact of play-based interventions on mental health outcomes from studies of children with DLD and ASD, as well as to identify the characteristics of research in this field.

Methods

The study used full systematic review design reported to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (PRISMA prisma-statement.org) with pre-specified inclusion criteria and explicit, transparent and replicable methods at each stage of the review. The study selection process involved a rigorous systematic search of seven academic databases, double screening of abstracts, and full-text screening to identify studies using randomised controlled trial (RCT) and quasi-experimental (QE) designs to assess mental health outcomes from interventions supporting children with DLD and ASD. For reliability, data extraction of included studies, as well as risk of bias assessments were conducted by two study authors. Qualitative data were synthesised narratively and quantified data were used in the metaanalytic calculation.

Main contribution

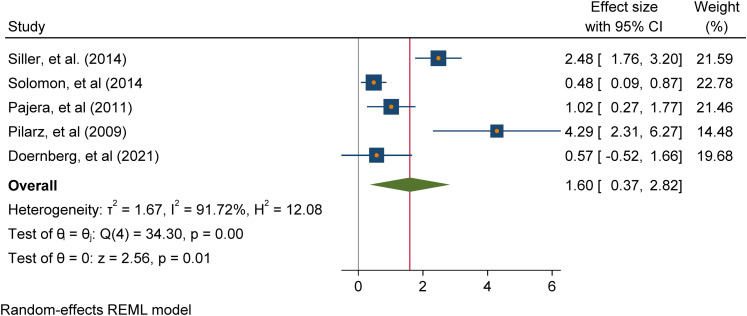

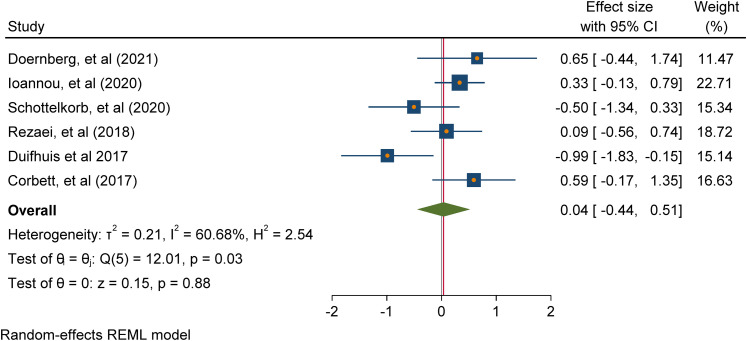

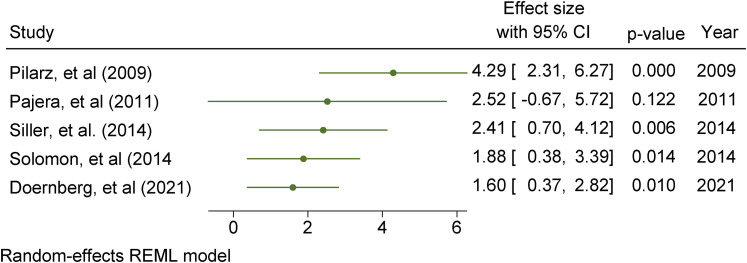

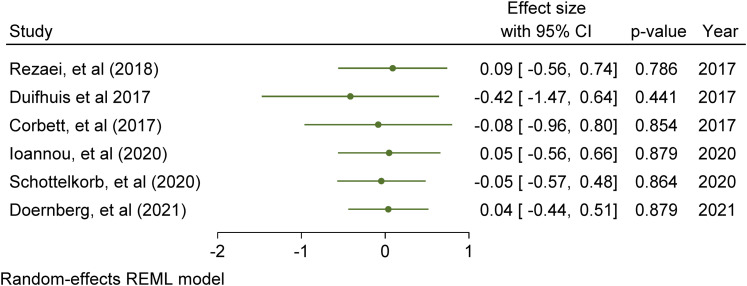

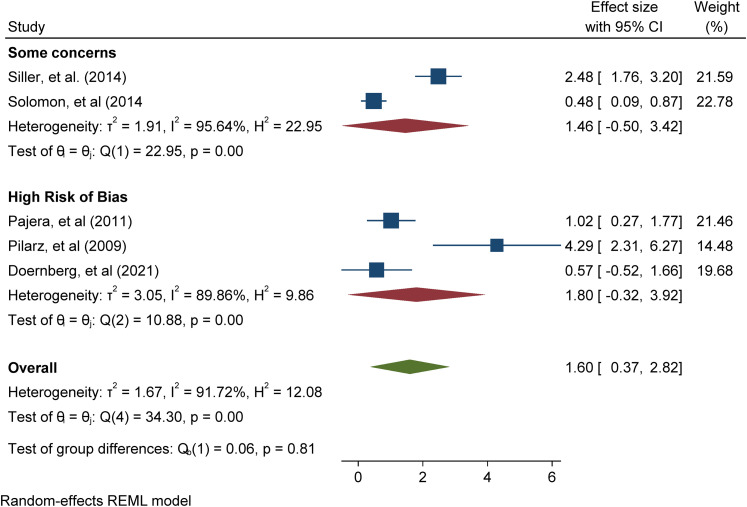

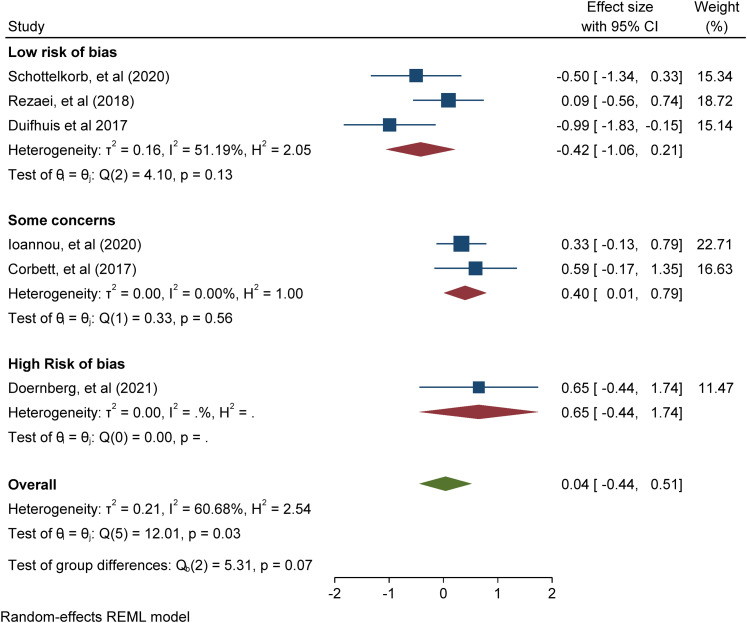

A total of 2,882 papers were identified from the literature search which were double screened at the abstract (n = 1,785) and full-text (n = 366) levels resulting in 10 papers meeting the criteria for inclusion in the review. There were 8 RCTs and 2 QEs using 7 named play-based interventions with ASD participants only. Meta-analysis of 5 studies addressing positive mental health outcomes (e.g. positive affect and emotional functioning) found a significant overall intervention effect (Cohen's d = 1.60 (95% CI [0.37, 2.82], p = 0.01); meta-analysis of 6 studies addressing negative mental health outcomes (e.g., negative affect, internalising and externalising problems) found a non-significant overall intervention effect (Cohen's d = 0.04 -0.17 (95% CI [-0.04, 0.51], p = 0.88).

Conclusions

A key observation is the diversity of study characteristics relating to study sample size, duration of interventions, study settings, background of interventionists, and variability of specific mental health outcomes. Play-based interventions appear to have a beneficial effect on positive, but not negative, mental health in children with ASD. There are no high quality studies investigating the efficacy of such interventions in children with DLD.

Implications

This review provides good evidence of the need for further research into how commonly used play-based interventions designed to support the social, communication, and language needs of young people may impact the mental health of children with ASD or DLD.

Keywords: Play-based interventions, autism spectrum disorder, developmental language disorder, mental health, systematic literature review

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and developmental language disorder (DLD) are common neurodevelopmental disorders, with prevalence rates of ∼1% and ∼7%, respectively (Baird et al., 2006, Norbury et al., 2016). The disorders are characterised by social, communication, and or language impairments. Young people with ASD and DLD also tend to have poorer mental health compared to their neurotypical peers (Yew & O’Kearney, 2013). Given their language and communication impairments, these young people may find it difficult to access talking therapies. There is some evidence from observational studies that play may be associated with a decrease in subsequent mental health difficulties in children with ASD and DLD (e.g. Toseeb et al., 2020a). However, observational studies cannot demonstrate whether such associations are causal. There is a growing body of experimental research reporting on mental health outcomes for young people with social, communication, and or language impairments from play-based interventions but the findings are inconsistent. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis sought to review the evidence from experimental studies to investigate the effectiveness of play-based interventions for mental health in children and adolescents with ASD and DLD.

ASD and DLD

ASD and DLD are common neurodevelopmental disorders. Both can be conceptualised as spectrum disorders such that affected individuals have a unique set of strengths and weaknesses. ASD is characterised by difficulties in social communication and interaction and restricted and repetitive behaviours, interests, and activities (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These features of ASD manifest differently across affected individuals to varying frequencies and severities. Young people with DLD are impaired in their ability to learn and use oral language (Bishop et al., 2017). This is in the absence of certain biomedical conditions, such as ASD and hearing loss. The term DLD has been adopted in recent years and encompasses other terms such as specific language impairment (SLI). Young people with SLI have impaired oral language ability but their non-verbal cognitive ability is within the normal range (Tomblin et al., 1997). The term DLD does not require a discordant verbal and non-verbal cognitive ability; therefore, all young people with SLI can be described as having DLD. For consistency and ease of comprehension, the term DLD is used here to include both SLI and DLD. Additionally, young people with ASD and DLD tend to have poorer mental health compared to neurotypical young people.

Mental health

Mental health is a multi-dimensional complex construct, which consists of both positive and negative features. Positive mental health refers to positive affect and has been described in the literature as happiness, wellbeing, and life-satisfaction (Westerhof & Keyes, 2010). Negative mental health refers to the presence of negative affect and behaviours and is the focus of most mental health research, commonly referred to as mental health disorders. These include symptoms of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The World Health Organisation defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (World Health Organisation, 1948), suggesting that both positive and negative mental health are important features of overall mental health. The absence of mental health difficulties is not synonymous with positive mental health. For example, young people may be neither happy nor experiencing low mood, whilst others with a high level of mental health difficulties might have high levels of life-satisfaction (Patalay & Fitzsimons, 2018). This is in line with psychological theory, whereby positive and negative mental health are related but distinct constructs (Dual-continua model of mental health, Westerhof & Keyes, 2010). Given also that the correlation between positive and negative mental health is moderate (Patalay & Fitzsimons, 2016), the evidence suggests that positive and negative mental health should be considered separately.

Diagnosable mental health conditions are not necessarily the same as mental health difficulties. Experiencing mental health difficulties, such as symptoms of low mood, anxiety, irritability etc., are a normal part of life. Low mood is to be expected after a negative life event and anxiety is an adaptive response to alert us to imminent danger. These responses turn into a diagnosable disorder when they become persistent and cause functional impairment1 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Psychiatric diagnoses rely on individuals to be able to explain their symptoms and the related functional impairment. Young people with ASD and DLD are likely to struggle with this due to their language and communication difficulties. In addition to this, individuals who fall slightly below diagnostic thresholds may be precluded from a diagnosis. Such binary categorisations are unhelpful in understanding the frequency and intensity of mental health difficulties. For these reasons, symptom-based measures of mental health may be preferred as they provide a comprehensive account of the nature and type of difficulties rather than simply the presence or absence of disorder. This is important because some interventions may lead to an improvement at a symptom level, which improves the quality of life in the affected individuals.

Child and adolescent mental health can be viewed through the lens of social and emotional development. Features of mental health may manifest differently through development. During the first few years of life, an infant's ability to form relationships, recognise and respond to emotions, explore their environment, and meet major milestones may be considered a positive indicator of their mental health. Difficulties in these areas might sometimes be precursors to mental health difficulties in later life. As infants grow older and become children and then adolescents, it becomes easier to identify their feelings and behaviours as mental health difficulties. This is partly due to more established measures of mental health at these ages but also because behaviour at these ages more closely corresponds to documented symptoms of mental health difficulties. Therefore, in this systematic review, a broad definition of mental health has been adopted to account for the diversity in the manifestation of mental health difficulties across development.

ASD, DLD, and mental health

Young people with ASD and DLD tend to have poorer mental health compared to their unaffected peers. Early research reported that approximately 70% of young people with a language disorder have a diagnosable mental health condition (Cantwell & Baker, 1987). This also translates at the symptom level. Young people with DLD have more symptoms of internalising and externalising problems compared to their unaffected peers (Yew & O’Kearney, 2013). There is a similar state of affairs for young people with ASD. Approximately 40% of children and adolescents with ASD have a diagnosable anxiety disorder (van Steensel et al., 2011). They also have higher rates of a diagnosable depression disorder (Hudson et al., 2019). In addition to the quantitative differences in mental health difficulties in ASD and DLD populations, there is also emerging evidence to suggest that they experience such difficulties in a qualitatively different way. For example, young people with ASD experience sensory symptoms differently (Ben-Sasson et al., 2009) and have different coping strategies (Mazefsky et al., 2013).

The co-occurrence of an ASD or DLD and mental health difficulties may be due to three possible explanations: 1) The presence of ASD or DLD features lead to mental health difficulties, 2) mental health difficulties lead to ASD or DLD, and or 3) ASD or DLD are caused by a third factor (e.g., genetics or a common environmental risk factor). First, the presence of ASD or DLD affects children's cognitive abilities which, according to the social information processing theory (Crick & Dodge, 1994), affect their social interactions. Young people with ASD or DLD may be less able to navigate social situations leading to withdrawal and the onset of psychopathology. For example, young people with DLD have higher levels of social anxiety (Durkin et al., 2017), which is associated with poorer mental health compared to their neurotypical peers In addition to this, it is well documented that young people with ASD or DLD are more likely to be bullied by siblings and peers (Toseeb et al., 2018, 2020b, van den Bedem et al., 2018), and may have poorer quality friendships (e.g., Andres-Roqueta et al., 2016), all of which are associated with mental health difficulties. The second possibility is that earlier social and emotional difficulties exacerbate or trigger the onset of features of ASD or DLD. Usage-based approaches to social, language, and communication development highlight the importance of social context (e.g., Tomasello, 2003). Social interactions between primary caregiver and child, and also between the child and their peers, provide a context in which to develop social, language, and communication skills (e.g., Hoff, 2006). Young people with pre-existing social and emotional difficulties may find it difficult to access these social interactions and so features of ASD or DLD are exacerbated. The final possibility is that the occurrence of ASD or DLD and mental health difficulties is due to a third unmeasured factor. Recent evidence suggests that common environmental factors, primarily consisting of socioeconomic variables, explain much of the variation in social, communication, and mental health outcomes (Bignardi et al., 2021). Additionally, common genetic variants may influence both DLD and mental health (Newbury et al., 2019, Toseeb et al., 2021). Playing with others may be beneficial for the mental health of children and adolescents with ASD or DLD as it enables them to learn and practise key emotional and behavioural regulation skills.

Play

Play is the leading form of activity in most children's lives which provides them with limitless opportunities to satisfy their unrealisable tendencies and sudden desires (Vygotsky, 1933). Play is a difficult term to define, as any activity that is freely chosen, child-driven, and pleasurable for the child can be conceptualised as play (Sturgess, 2009). The overall characteristics of play are described as spontaneous, free, non-literal, intrinsically motivated, pleasurable, and purified from externally imposed rules (Rubin, 1982; Saracho & Spodek, 1998; Hughes, 2003).

Numerous theories have tried to explain the necessity of play in children's lives. Home Ludens, a modern historical theory of play, suggests that play is the core element of children's lives as it provides them freedom, pleasure, and joy (Huizinga, 1949). In addition, the constructivist theory indicates that play is an integral part of children's development, as it is closely related to cognitive and language skills (Piaget, 1952). From a psychosocial perspective, it is claimed that play is children's own way to self-define social reality and provides them with a suitable environment to build their self-control skills (Erikson, 1993). In psychoanalysis, it is proposed that play creates a fantasy world for children to cope with the complexity of reality and provides the opportunity to explore and express their deep emotional states (Freud, 1955). As suggested by these theories, far from being thought to be a trivial activity in children's lives, play has a fundamental role in supporting children's various development, including, but not limited to, their cognitive, emotional, language and behavioural regulation skills.

The term play-based intervention stands for either the socio-cognitive techniques that are specifically built on the elements of play or the implementations that are delivered during the playtime or within the play settings (Ingersoll & Walton, 2013). The importance of play-based interventions in supporting children's development was recognised in the early 20th century. Little Hans is known as the first child who was treated with play for his phobic symptoms (Freud, 1909). Melanie Klein (1929), a student of Freud, also used play as a therapeutic tool to apply Freud's psychoanalytic techniques initially used with adults to subsequently apply to children. Wells (1912) and Lowenfeld (1939) were the other earliest child psychoanalysts that used sand play to support children with emotional problems. However, Virginia Axline (1947), a student and later colleague of Carl Rogers, firstly used the term play therapy and introduced client-centred play therapy as a structured play intervention to treat children's emotional difficulties.

Children of today's world are growing up in a dynamic environment in which they may not be getting enough time and opportunities to play freely. Today, children are playing less than those in previous generations; Natural England (NE) reports that less than 10% of the new generation play outside, naturally, whereas this rate was more than 50% in their parents’ generation (England Marketing, 2009). In the United States, it is claimed that children's playtime is significantly reduced by their parents stealing their spare playtime to invest more in schoolwork (Chudacoff, 2007). The lack of play in children's lives, thus, may be the reason underlying the failure of the new generation of children in reaching some developmental milestones at certain ages. For instance, early opportunities for make-believe play are suggested to be crucial for developing imaginative thought (Goldstein, 1994). It is also suggested that a child's playfulness is connected to their secure attachment, emotion regulation, empathy, and emotional resilience (Whitebread, 2017). Play deprivation in early childhood, however, is suggested to be associated with emotional/self-dysregulation and aggression with higher deprivation results in higher prevalence of dysfunctioning in these areas (Brown, 2014). In addition, children with identifiable deficits in play skills are at further risk in accessing developmental affordances from play (Toseeb et al., 2020b).

Numerous interventions have been built on play to support children's social, emotional, and cognitive development. However, the characteristics of such interventions vary in the sense of the definition and representation of play, play approach (e.g., directive or non-directive), or type of play (make-believe, fantasy, parallel, etc) that the delivered intervention is built on (Thomas & Smith, 2004). It is crucial to well-define play to differentiate the interventions that are solely built on play from any other interventions. Play is defined as activities that are intrinsically motivated, spontaneous, free from externally imposed rules, guided by organism-guided questions, non-literal and requires active engagement (Rubin et al., 1983, p.698). The authors also drew a clear line between play and game as: “Play is further distinguished from game in that the latter phenomenon is goal oriented whereas the former phenomenon is not. One plays for the satisfaction of playing. One engages in games to compete, to win, and to achieve some specified goal” (p.728). Taking Rubin et al.'s broad definition of play into account, this review focuses on the interventions that were solely play-based, delivered during the playtime or within the play settings such as, robot/animal-based play (e.g., canine-assisted play), peer-mediated play (e.g., the SENSE Theatre), parent-child interaction play (e.g. DIR/Floortime), school-based play (e.g., Early Start Denver Model), non-directive play (e.g., child-centred play), cognitive-therapeutic play (e.g., Jungian play), etc.

Although there is considerable evidence supporting the effectiveness of play-based interventions on children's holistic development, the majority of interventions have focused on children's social, communication, and language skills. For example, a study on the relationship between play and children's social development has reported that social-interactive play increases social competence in young children (Newton & Jenvey, 2011). Another study reports a significant increase in social interaction and language skills and a decrease in play deficits and disruptive behaviours of children with special educational needs and disabilities following a play intervention (O’Connor & Stagnitti, 2011). Furthermore, it has been suggested that play increases receptive and expressive vocabulary in at-risk preschoolers (Han et al., 2010), and a strong link has been found between symbolic play skills and functional language abilities of children with ASD (Mundy et al., 1987). Despite this, very few empirical studies have targeted the mental health outcomes of children. A recent systematic review of child-led play interventions also argued that such interventions mostly target children's social development instead of focusing on emotional outcomes (Gibson, et al., 2017).

The effectiveness of play-based interventions on children's emotional outcomes has only grabbed a few researchers’ interests. For example, one study investigated the effectiveness of unstructured play in reducing the anxiety level of young children in paediatric inpatient care and reported that a nurse-delivered play intervention was highly effective in reducing the anxiety levels of hospitalised children (Al-Yateem & Rossiter, 2017). Additionally, another study examined whether an unstructured play intervention reduced the stress level of hospitalised children in inpatient care and reported that children aged 7 to 11 years old showed a significant decrease in cortisol levels (a marker for stress) compared to the control group (Potasz et al., 2013). In addition, a playful approach of Six Bricks and DUPLO® has also been found effective on positive emotions and emotional competence of early adolescents (Harn & Bo, 2019).

Relevant systematic literature reviews

There are a handful of published reviews and meta-analysis synthesising work that address the mental health of individuals with social, communication and or language impairments generally or assess the impact of a play-based intervention on such individuals’ mental health. For instance, in a meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies reporting the prevalence of depressive disorders among individuals with ASD, Hudson, Hall, and Harkness (2019) reported that lifetime and prevalence of depressive disorders was 14.4% (95% CI 10.3–19.8) and 12.3% (95% CI 9.7–15.5), respectively, across samples of children, adolescents, and adults with ASD. Their findings indicate that the rates of depressive disorders are high among individuals with ASD. In a separate narrative review, Blewitt et al. (2019) investigated the extent to which preservice education programmes led by early childhood teachers and carers address ASD children's social and emotional development. After screening papers from MEDLINE Complete, PsychINFO and ERIC between January 1999 and July 2019, the authors identified only a limited number of studies (n = 19) and concluded that teachers are not adequately prepared to deal with ASD children's social, emotional and behavioural challenges. Newton and Jenvey (2011) recommended that programmes should promote naturalistic and embedded social skill instruction within and across everyday interactions, play, activities and the environment, thereby offering contextually relevant opportunities to strengthen children's social-emotional skills can help.

Three additional review studies were found that synthesise the effect of different types of play-based intervention - Child-Centered Play-therapy (Hillman, 2018), DIR/Floortime (Mercer, 2017), and Pivotal Response Treatment (PRT) (Verschuur, et al., 2014). These are recognised play-based interventions derived from play-therapy approaches developed to support ASD children's social, emotional, and cognitive development and the reviews included in their synthesis at least one mental health outcome. Child-centered play therapy is used to improve core concerns related to ASD, such as social communication skills, joint attention and emotional regulation (Hillman, 2018). The effectiveness of Child-centered play therapy with ASD populations was investigated by Hillman (2018) in a comprehensive search of the Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC) and PsycINFO databases between 1900 and September 2017. Only four studies were identified in this review, of which only two addressed mental health outcomes - emotional growth and empathy, using single-case and multiple-baseline designs, with mixed results. According to Hillman (2018) more research is needed to understand the impact of Child-centered play therapy on ASD children. The other review, Mercer (2017), assessed the plausibility of, and evidentiary support for, the treatment DIR/Floortime - an intervention that uses therapeutic goals to work with autistic children and typically involves a functional emotional assessment along with other social communication and language evaluations. Mercer (2017) searched the Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO, and PubMed databases articles up to January 2015 and identified ten studies of which two studies used experimental designs and included an assessment of ASD children's emotions as a study outcome. Mercer concluded that although there is some support for the effectiveness of the DIR/Floortime intervention; the support is weak because of design flaws. The third review used PRT to teach pivotal behaviours to children with ASD in order to achieve generalised improvements in their functioning on four aspects of pivotal functioning: (a) motivation, (b) self-initiations, (c) responding to multiple cues, and (d) self-management (Verschuur et al., 2014). The authors screened studies published in ERIC, Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts, Medline, PubMed, and PsychINFO databases between December and June 2013 and identified thirty five intervention studies of which three studies reported mental health outcomes (increase in positive affect).

Whereas, the first two meta-analyses highlighted mental health challenges as prevalent among individuals with ASD none of the reviews of play-based interventions explicitly focused on the impact of mental health outcomes. This indicates a gap in the literature and a need for a review of play-based interventions and mental health outcomes.

The current study

A better understanding of how interventions also impact the mental health of children is valuable for evaluating the utility of these interventions in fostering holistic child development in neurodiverse populations. This review is important as it illuminates how play-based interventions designed for children with social, communication, and or language impairments related to diagnoses of ASD and DLD impact mental health outcomes. Questions addressing both the contextual design and the effectiveness of interventions can validate good practice in the field or make recommendations for improvement. This systematic review and meta-analysis addresses the following research questions:

What are the characteristics of play-based interventions used to support children and young people with ASD or DLD to improve their mental health outcomes?

Are play-based interventions designed for children with ASD or DLD effective in supporting their mental health?

Methods

A systematic literature review with meta-analysis was conducted following standards from the Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for evaluating and reporting on the effectiveness of interventions (Higgins et al., 2021; Page et al., 2021). This involved searching for, locating, quality appraising and synthesising, both narratively and statistically, all the relevant studies that can address the question about the effectiveness of play-based interventions on the social, communication, language, and mental health outcomes of children with social, communication, and language impairments. The systematic review included studies exploring all outcomes in a broad ‘mapping’ of the field but narrowed to an in-depth synthesis and a meta-analysis of studies with the findings for mental health outcomes only. At the inception of the review, a-priori criteria for including studies in the review were developed in a protocol through collaborative discussions among the study authors before commencing the search process to identify potentially relevant studies.

Eligibility criteria

Pre-specified inclusion criteria were developed to identify studies evaluating high-quality interventions based on topic, study designs, characteristics of participants and intervention and control conditions, in order to include studies that can address the research questions. These pre-specified inclusion criteria provided the basis for selecting studies for inclusion in the review (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Criteria for Selecting Studies for this Review.

| Study Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Experimental Designs | Experimental designs using single group comparisons |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Date | Studies published between 2000–2021 | Studies published < 2000 |

| Language | Studies published in English | Non-English publications |

| Participants | Participants age ranges include: | Adults |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Classification of participants with social-communication needs e.g.: | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Interventions | Play interventions addressing mental health as well as social, communication, and language outcomes in children with social-communication impairments | Non-play-based interventions |

| Comparisons | Comparison of play-based interventions to a control group using no intervention, wait-list control, usual care, or an active control group which is a nonplay-based intervention. | Comparisons of two play-based interventions |

| Outcomes | Mental-Health/Wellbeing outcomes | Non social-communication, socio-emotional or mental health outcomes |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Social - Communication outcomes | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Setting | Research settings e.g. | No exclusions on the basis of description of research settings. |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Play intervention setting e.g.: | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Play intervention provider e.g. | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

|

Only studies using experimental designs were included. These include: (1) randomized controlled trials (RCTs): studies that randomly assign participants to intervention and control or comparison conditions; (2) quasi-experimental designs (QEs) using pre/post- tests designs with non-equivalent comparison groups where participants are not randomly assigned to conditions; (3) regression discontinuity designs which assign participants to conditions on the basis of a predetermined cut-off on a continuous variable; and (4) time-series designs involving at least three observations made both before and after a treatment. All included studies were required to have a control or comparison group that either did not receive a treatment or were on a waitlist to receive treatment after the end of the experiment (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). As the aim was to evaluate intervention designs that infer causality, studies that employed single case experimental designs and multiple-baseline designs were excluded. Although they are commonly used in research with children with social, communication, and language disorders and can provide limited evidence of causality, for the purposes of this review the inclusion criteria specified only the most robust designs were included.

In addition, as mentioned earlier, this review focuses on the studies that used interventions that were inherently playful but not based on any other behavioural modification techniques. Therefore, studies that focus on behavioural interventions, teaching or training, peer-based group activities, and game-with-rules (e.g., script-fading, activity schedules, group activity schedules, computer/online-games, video-prompting, behavioural intervention, wearable devices/virtual reality, and gaming activities) were kept out of the scope of this review. Hence, to meet this inclusion criterion, interventions should either be solely play-based or delivered during the playtime or within the play settings. Also, studies that compared the effectiveness of two or more play-based interventions on the mental health outcome of children with ASD or DLD were also excluded.

An initial scoping exercise was conducted by the first and second authors to inform the aspects of the study's eligibility criteria. The scoping exercise was especially useful for two reasons: (1) to ascertain the period during which a significant record of publications reporting play-based interventions with children with social-communication impairments exist so as to specify the time-line for the review, and; (2) to identify relevant terms, specifically the name of play-based interventions and terms used to refer to children with ASD and DLD. The list of play-based interventions identified include: Play Therapy, Theraplay, Play-based interventions, PRT, Joint Attention, Symbolic Play, Engagement & Regulation (JASPER, Advancing Social-communication And Play (ASAP), LEGO Therapy, The Developmental, Individual Difference, Relationship-Based (DIR) Floortime Model, The Paediatric Autism, Communication Therapy (PACT), Stay, Play, & Talk, PLAY Project, Project ImPACT, Early Start Denver Model (ESDM), E-PLAYS, CCPT (Child-centred play therapy), Filial therapy, Animal/Parent/Peer/Sibling assisted play, Non-named play-based interventions. Classification terms used to refer to individuals with social-communication needs were also identified.

Only relevant publications dating from the last two decades (2000 to 2021) published in English Language journals were included. The scoping exercise indicated the majority of play-based experimental interventions were undertaken during that timeline. We screened for peer-reviewed journal articles as well as masters and doctoral theses but excluded conference papers and grey literature due to insufficient resources.

To identify eligible studies, detailed specifications of the population, intervention, comparators, outcomes, and settings (PICOS) were outlined as key components of interest (Thomas et al., 2021). Study participants were inclusive of children diagnosed with a social, communication, and language impairment including ASD or DLD. Participants’ ages ranged from infancy to adolescence and we categorised infancy as less than two years, childhood from 2 to 12 years, and adolescents 12 to 21 years (Hardin et al., 2017). The intervention types considered are all play-based interventions whether using validated or less formally developed programmes, as well as those supporting children with social-communication disorders through peer-mediated and parent-mediated designs. Comparisons between intervention groups are based on studies having the following control conditions: no intervention; wait-list control; usual care; or interventions with active controls if the comparison is a nonplay-based control. Studies with outcomes relating to the social communication, language, and mental health needs of children were deemed eligible for inclusion. Studies needed to describe the setting of the intervention in detail as this level of description is important for understanding the context under which play-based interventions may or may not be effective.

Information sources

To identify studies, a comprehensive search of academic research databases was undertaken between January and March 2021. The searchable publication databases used were: ‘Ebscohost/ERIC’, ‘Web of Science’, ‘Pubmed’, ‘SCOPUS’, ‘PsycINFO’, ‘PROQuest’, and ‘ETHOS’.

Search strategy

A consistent search strategy was applied across databases. Boolean search strings were developed using keywords. These included references to play as a generic term stringed with types of language impairments e.g., Play AND “language disorder”, Play AND “specific language impairment”, etc or types of play-based interventions, only e.g. “PRT”, or “Theraplay”. The full list of Boolean search strings is presented in Appendix A.

Selection process

An exhaustive search of the selected academic databases using all combinations of the Boolean search strings was undertaken by one author [ED] and all hits were downloaded into the Mendeley Reference Manager software (Mendeley, 2021). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses based on the same topic area generated from the search were retained to undertake manual hand-searching of their reference lists as a strategy for capturing additional peer-review articles not published in the databases searched. The titles and abstracts of all studies in Mendeley were independently double screened and the papers which both authors [ED & GF] agreed met the eligibility criteria were carried over for independent double screening of full texts and agreement. To identify any other potential articles overlooked from the database searches, backward chaining was done by authors [ED & GF] by consulting the reference lists of papers recommended for full-text screening when in-text citations indicate an article might be highly relevant.

Data extraction process

A data extraction form was designed to abstract relevant bibliographic details and information about the sample and sample characteristics, intervention and control or comparison conditions, and quantified outcomes from individual papers included in the review. To quality assure the robustness of the completion of the data extraction form for each included study, the following process was followed: first, all four authors [ED, GF, CT, UT], extracted data from one paper and the results were compared for consistency and sufficiency of the evidence to answer the research questions; subsequently, data extraction was divided between three authors [ED, GF, CT] such that data from each paper was independently extracted by two different authors and compared for agreement, with any adjustments being made if there was any initial disagreement, and arbitration by the fourth author [UT] where necessary.

Outcomes

The review investigated the effect of play-based interventions on mental health and wellbeing outcomes including variables like happiness, self-esteem, wellbeing, depression, anxiety, stress, emotional difficulties, internalising or externalising difficulties, etc. All post-intervention outcomes were extracted. The decision was taken to include both primary and secondary outcomes, and experimenter-developed outcome measures as well as validated measures, where applicable.

Mid-intervention data and post-intervention follow-up data were excluded. Other pertinent data extracted include information about participant characteristics, e.g., social communication and language diagnosis, age of participants, etc., and intervention characteristics e.g., sample size, the background of the person delivering the intervention, setting of the intervention, etc. Missing data were sourced by contacting the corresponding author of a given study, if necessary.

Study risk of bias

An assessment of the risk of bias2 was conducted for all studies included in the review using sample questions from the revised ‘Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Trials’ (RoB 2) and ‘Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions’ (ROBINS-1) to appraise RCTs and QE studies, respectively (see Appendix B). Both instruments focus on different aspects of trial design, conduct and reporting comprising six domains under which signal questions are posed to elicit information about features of the trial that are relevant to the risk of bias (Sterne et al., 2016, 2019). The six domains addressed the risk of bias arising from:

randomisation in RCT or confounds in QEs

deviations from the intended interventions in RCTs or effect of assignment to interventions in QEs

missing outcome data

measurement of the outcome

selection of the reported result

In each domain, a judgement of ‘low’, ‘high’, or ‘some concerns’ for risk of bias is asserted and used to make an overall judgment about the ‘risk of material bias’ of the study. A judgement of ‘high’ risk of bias for any individual domain will lead to the result being at ‘high’ risk of bias overall, and a judgement of ‘some concerns’ for any individual domain will lead to the result being at ‘some concerns’, or ‘high’ risk, overall. The aim is to expressly identify issues that are likely to affect the ability to draw reliable conclusions from the study (Sterne et al., 2019). The shortened versions of the risk of bias tools used were trialled by all four authors on a selected paper and a final version was agreed upon through discussion. The review papers were appraised independently by the first and second authors [GF & ED] and 25% of each author's sample was independently appraised by the other two authors [CT & UT].

Effect measures

Effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals were computed based on post-intervention measurements as study outcomes were continuous. Effect sizes were calculated based on Cohen's d using the online Practical Meta-analysis Calculator and replicated in Stata (StataCorp, 2021. Standardised mean difference and standard error values for each outcome were generated from values of means and standard deviations reported in the individual papers. . Where data were not available, the effect size was computed using other appropriate statistical indices, e.g. F-test statistics and sample sizes. Issues of missing data were addressed by contacting the corresponding author of individual papers to request additional information. According to White, Redford, & MacDonald (2020), suggested thresholds of statistically significant effects of Cohen's d in social science research include: (1) 0 < d < 0.1 indicates a trivial effect; (2) 0.1 < d < 0.2 indicates a small effect; (3) 0.2 < d < 0.5 indicates a moderate effect; (4) 0.5 < d < 0.8 indicates a medium size effect; (5) 0.8 < d < 1.3 indicates a large effect; (6) 1.3 < d < 2.0 indicates a very large effect; (7) d > 2.0 indicates an extremely large effect.

It was necessary to correct for differences in the direction of measurement scales because the standardised mean difference method does not account for such differences (Higgins, et al., 2021). This was necessary for studies grouped as measuring negative mental health. For example, some scales increased with trait severity (e.g., a higher score indicated severe negative mental health) whilst others decreased (e.g., a lower score indicated less severe negative mental health). To ensure that all scales pointed in the same direction, the mean values for scales with positive directionality were multiplied by −1, before standardisation (Higgins, et al., 2021).

To account for statistical dependencies, cases where the data are dependent i.e., multiple outcomes from one study, the average effects were computed to yield a single effect estimate (Borenstein, 2009). Some studies were comparisons of two intervention approaches; hence, these were included only if it was a comparison between a play-based and non-play-based intervention. Therein, the non-play-based intervention was treated as the control group and the play-based approach as the intervention group.

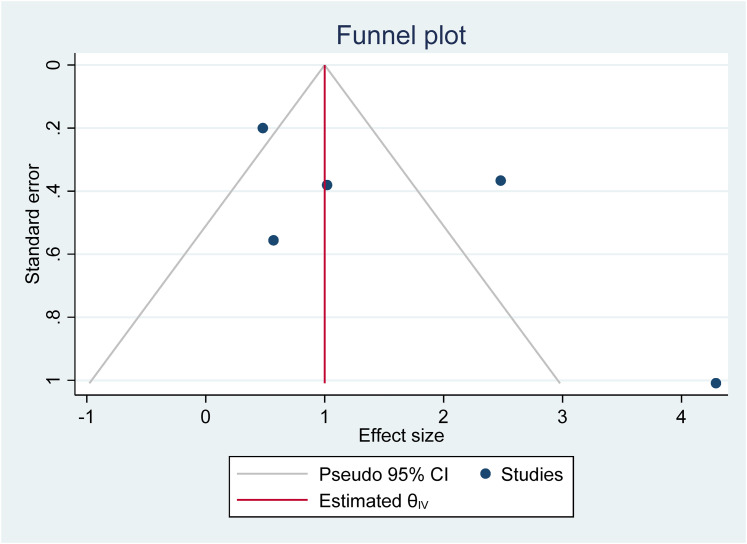

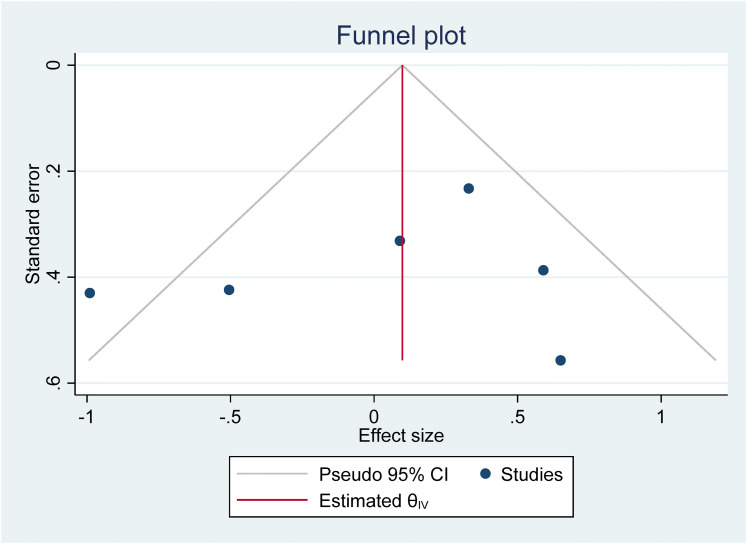

Synthesis methods

Study outcomes were classified based on whether the measures assessed positive or negative mental health. In addition, both narrative and statistical analyses were undertaken. The narrative analysis involved comparing intervention characteristics across studies [RQ1] and statistical analysis involved meta-analytic calculations of the mental health outcomes to make inferences about the effectiveness of play-based interventions [RQ2]. To undertake statistical syntheses of the review data, meta-analyses of study outcomes were conducted in Stata using the inverse variance estimation method and a random effects model. The random-effects model assumes the existence of within-and between-study variability or heterogeneity in estimating individual and combined study effects and attempts to minimise both sources of variance (Borenstein, 2009). The meta-analytic results are depicted with forest plots which show effect sizes and corresponding confidence intervals for studies at the individual and combined level, as well as heterogeneity statistics. Within study variability is assessed by the χ2 (Q) test and a significant p-value (or a large χ2 statistic relative to its degree of freedom) is indicative of evidence of heterogeneity of intervention effects (Hedges, 1982; Higgins et al., 2021). Between-study variance is inferred from tau (T²). The proportion of variance in study effect size is indicated by I² (Higgins & Thompson, 2002). Values of 25%, 50%, and 75% are proposed as benchmarks of low, moderate, and high variance with large I² inviting speculation for the reasons of the variance (Higgins, et al., 2003; Borenstein, 2009). A high I² suggests that variability between effect size estimates are due to between-study differences rather than the sampling variation (Borenstein et al., 2017). Also, the prediction interval or range of predicted effects (standard deviation of the overall effect size estimate) is reported. However, this should be interpreted cautiously, as the results can be very spuriously wide or spuriously narrow when the number of included studies are small (Higgins et al., 2021). Further inspection of the data included assessment of publication bias to explore concerns around the under-reporting of non-significant results. This involves visual inspections of funnel plots to check for study asymmetry and statistical tests of small study effects using the non-parametric trim and fill method to assess the impact of missing studies from potential publication bias. A sensitivity analysis to compare studies by research design or risk of bias results was undertaken. Meta-regression analyses were undertaken to investigate whether study heterogeneity could be explained by study moderators or pre-specified study characteristics depending on whether there are sufficient numbers of homogenous studies.

Results

Study selection results

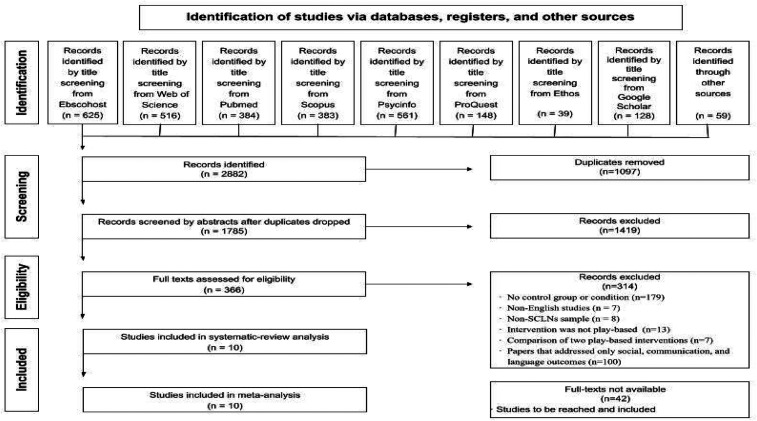

The automated searching of electronic databases yielded 2882 papers including existing related systematic review papers used for citation searches and additional sources obtained from backward chaining, that is, articles identified from checking the reference list of review papers and from following up on relevant citations flagged during the full-text screening (n = 59). After deduplication, 1785 papers were retained. Titles and abstracts were double screened by the first and second authors [GF & ED]. The two authors [GF & ED], agreed on the inclusion of 366 papers, the exclusion of 1362 papers, and identified 42 papers that could not be evaluated due to being inaccessible3 at the time of screening. There was disagreement on 15 papers that were discussed and resolved through discussion with the research team. Cohen's kappa coefficient for inter-rater reliability was κ = .88 (95% CI, .85 - .91) which indicates that the agreement between the first two authors on the selection of articles for full-text screening was very good.

The process of double screening was repeated on the 366 papers eligible for full-text screening. Through a process of consensus agreement, a total of 314 papers were excluded for the following reasons: a) no control or comparison group (n = 179); b) published in languages other than English (n = 7); c) sample participants did not have a diagnosed social communication or language impairment (8); (d) intervention was not play-based (n = 13); e) comparison between two play-based interventions (n = 7); f) only social, communication, and language outcomes (n = 100). In total, 10 papers met the eligibility criteria, i.e., explicitly reported mental health outcomes for study participants which is the focus of this review (see PRISMA Flow Diagram in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram for Record of Systematic Searches of Databases

Of particular note was the fact that the 10 studies were published during the period 2008 to 2021, although the database screening was conducted from the period January 1st, 2000 to January 31st, 2021. The absence of records of play-based interventions using RCTs and QEs addressing mental health outcomes of children with ASD or DLD before 2008 is striking.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the ten studies are described based on study design, sample sizes, and characteristics of play-based interventions used. A full description of studies at the individual level is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Included Studies and Study Characteristics

| Study ID | Study reference, publication, and country | Sample characteristics | Research design | Play intervention | Outcome variable | Summary of results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S01 |

Corbett et al.

(2017) Publication: Journal of Autism Country: USA |

Sample size: N = 30 Sample: Children with ASD Age: 8-14 years old Girls: N = 6 (20%) Boys: N = 24 (80%) INV: N = 17 CON: N = 13 |

Design: RCT Type of control: Randomly allocated, waitlist control Control group treatment: SENSE Theatre® Outcome Measure: The STAI-C (Spielberger et al., 1983) Measure standardised: Yes |

Name of intervention: SENSE

Theatre® Intervention valid: Yes Type of play: Role play Place: Outside of school Provider: Not reported Duration: 40 hours |

Reported outcome:Trait anxiety Category: Negative mental health |

Test of between-subject effects revealed a significant group effect on post-STAI-C Trait, with pre-STAI-C Trait included as a covariate (F(1, 27) = 9.16, p = 0.005). Changes in play did not show a significant mediational effect on changes in trait-anxiety (B = −0.32; CI = −3.35 to 2.11). Conversely, the direct effect of the intervention on changes in trait-anxiety remained significant (B = −6.97, CI = −12.62 to −1.31). |

| Reported outcome: State anxiety Category: Negative mental health |

No group effect was observed for STAI-C State (F(1, 27) = 0.03, p = 0.86)). | |||||

| S02 |

Doernberg et al.

(2021) Publication: Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders Country: USA |

Sample size: N = 25 Sample: Children with HF ASD Age: 6-9 years old Girls: N = 3 (12%) Boys: N = 22 (88%) INV: N = 18 CON: N = 7 |

Design: RCT Type of control: Randomly allocated, waitlist control Control group treatment: Treatment as usual Outcome Measure: The APS (Fehr & Russ (2014)) Measure standardised: Yes |

Name of intervention: Pretend

Play Intervention valid: Yes Type of play: Pretend play Place: School Provider: The researchers Duration: 100 minutes |

Reported outcome: Total positive affect Category: Positive mental health |

Results did not indicate any significant effects for children’s abilities to generate a list of positive feelings, nor define complex emotions appropriately. |

| Reported outcome: Total negative affect Category: Negative mental health |

Results did not indicate any significant effects for children’s abilities to generate a list of negative feelings, nor define complex emotions appropriately. | |||||

| S03 |

Ioannou et al.

(2020). Publication: Frontiers in Psychology Country: USA |

Sample size: N = 77 Sample: Children with HF ASD Age: 8-16 years old Girls: N = 18 (24%) Boys: N = 59 (76%) INV: N = 44 CON: N = 33 |

Design: RCT Type of control: Randomly allocated, waitlist control Control group treatment: SENSE Theatre® Outcome Measure: The STAI-C (Spielberger et al., 1983) Measure standardised: Yes |

Name of intervention: SENSE

Theatre® Intervention valid: Yes Type of play: Role play Place: Outside of school Provider: Not reported Duration: 40 hours |

Reported outcome: State anxiety Category: Negative mental health |

There was no difference in State anxiety between EXP and WCL groups [F(2,71) = 0.07, p = 0.935]. |

| Reported outcome: Trait anxiety Category: Negative mental health |

Children in the EXP group reported significantly less Trait anxiety than children in the WLC group following intervention [F(2,71) = 6.87, p = 0.01]. | |||||

| S04 |

Pajareya &

Nopmaneejumruslers (2011) Publication: Journal of Autism Country: Thailand |

Sample size: N = 32 Sample: Children with ASC Age: 2-6 years old Girls: N = 5 (15%) Boys: N = 28 (85%) INV: N = 16 CON: N = 16 |

Design: RCT Type of control: Randomly allocated control group Control group treatment: Treatment as usual Outcome Measure: (1) The FEAS (Greenspan, DeGangi & Wieder, (2001). (2) The FEDQ (Pajareya, Sutchritpongsa & Sanprasath, 2014). Measures standardised: Yes |

Name of intervention: DIR/Floortime Intervention

valid: Yes Type of play: Parent and child interaction play Place: Home Provider: The first author Duration: 240 hours |

Reported outcome: Functional Emotional Assessment Score

(FEAS) Category: Positive mental health |

The change of the FEAS score for the control group reflects the overall developmental progression of only 1.9 (SD = 6.1), compared to the increment of 7.0 (SD = 6.3) for the intervention group. The Student t test shows that the difference is statistically significant (p = .031). |

| Reported outcome: Functional Emotional Developmental Score

(FEDQ) Category: Positive mental health |

Developmental rating of the children was estimated by the parent using the Thai version of the Functional Emotional Questionnaires at baseline and follow-up. The change in data for the intervention group shows that there was a more statistically significant gain in it than in the data of the control group. | |||||

| S05 | Rezaei et al. (2018) Publication: Journal of Children Country: Iran |

Sample size: N = 34 Sample: Children with ASD Age: Mean = 12.36 Girls: N = 12 (35%) Boys: N = 22 (65%) INV: N = 17 CON: N = 17 |

Design: RCT Type of control: Randomly allocated, waitlist control Control group treatment: PRT + Risperidone Measures: The ABC (Akhondzadeh et al., 2010) Measures standardised: Yes |

Name of intervention: Pivotal response treatment

(PRT) (Koegel, 2011) + Risperidone Intervention valid: Yes Type of play: Parent and child interaction play Place: School Provider: Speech/language therapist Duration: 27 hours |

Reported outcome: Irritability Category: Negative mental health |

There was no significant difference between the INV and Control groups in Irritability subscale. |

| Reported outcome: Hyperactivity Category: Negative mental health |

There was no significant difference between the INV and Control groups in Hyperactivity subscale. | |||||

| S06 | Schottelkorb et al.. (2020) Publication: Journal of Counseling & Development Country: USA |

Sample size: N = 23 Sample: Children with ASD Age: 4-10 years old Girls: N = 4 (17%) Boys: N = 19 (83%) INV: N = 12 CON: N = 11 |

Design: RCT Type of control: Randomly allocated, waitlist control Control group treatment: Treatment as usual Measure: CBCL (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Measures standardised: Yes |

Name of intervention: Child-centred play (Axline,

1947) Intervention valid: Yes Type of play: Non-directive play Place: Not reported Provider: Graduate-level counselling students and two licensed counsellors Duration: 12 hours |

Reported outcome: Externalising problems Category: Negative mental health |

Following the same trend as previous analyses, participants in the play therapy treatment group were reported to have decreased externalising symptoms from pre- to post-testing (M = 68.67, SD = 9.35; M = 63.08, SD = 7.90), whereas control group scores increased (M = 65.36, SD = 9.54; M = 67.27, SD = 8.72). |

| S07 |

Siller et al.

(2014) Publication: Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders Country: USA |

Sample size: N = 70 Sample: Children with ASD Age: 2-6 years old Girls: N = 6 (9%) Boys: N = 64 (91%) INV: N = 36 CON: N = 34 |

Design: RCT Type of control: Randomly allocated control group Control group treatment: Parent Advocacy Coaching (PAC) Measures: (1) PCSB (Ainsworth, 1978) (2)AB (Ainsworth, 1978) (3) MPCA (Hoppes & Harris, 1990) Measures standardised: Yes |

Name of intervention: Focused Playtime

Intervention (Siller et al.,2013) Intervention valid: Yes Type of play: Parent and child interaction play Place: Research lab + participants’ home Provider: Trained graduate and postdoctoral students in developmental psychology and counselling. Duration: 18 hours |

Reported outcome: Maternal Perceptions of Child Attachment

(MPCA) Category: Positive mental health) |

A significant main effect of treatment group allocation on gains in parent reported attachment behaviours (MPCA scores), t(48) = 3.0, p < .01. |

| Reported outcome: Proximity/ Contact Seeking Behavior Scale

(PCSB) Category: Positive mental health) |

Proximity and Contact Seeking Behaviors was only marginally significant, t(54) = 1.8, p\.08. | |||||

| Reported outcome: Avoidant Behavior Scale

(AB) Category: Positive mental health) |

For children’s Avoidant Behaviors, results revealed a significant main effect of treatment group allocation on improvements in Avoidant Behaviors from Time 1 to Time 2, t(54) = 2.2, p\.05. | |||||

| S08 |

Solomon

et al. (2014) Publication: Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics Country: USA |

Sample size: N = 128 Sample: Children with ASD Age: 2-5 years old Girls: N = 20 (16%) Boys: N = 108 (84%) INV: N = 64 CON: N = 64 |

Design: RCT Type of control: Randomly allocated control group Control group received treatment: Treatment as usual Measure: The FEAS (Greenspan et al., (2001). Measures standardised: Yes |

Name of intervention: PLAY Project home consultation

programme (Solomon et al., 2007) Intervention valid: Yes Type of play: Parent and child interaction play Place: Home Provider: 6 PLAY consultants (1 occupational therapist, 2 speech and language therapists, and 3 special educators) Duration: 36 hours |

Reported outcome: Functional Emotional Assessment Score

(FEAS) Category: Positive mental health |

The FEAS video ratings showed a significant moderate time 3 group effect with the PLAY group showing improvement in observed socioemotional behaviour, whereas the CS group remained stable. |

| S09 |

Duifhuis et al.

(2017) Publication:Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders Country: Netherlands |

Sample size: N = 24 Sample: Children with ASD Age: 3-8 years old Girls: N = 4 (16%) Boys: N = 20 (84%) INV: N = 11 CON: N = 13 |

Design: QE Type of control: Non-randomly allocated control group Control group received treatment: Yes, treatment as usual Measure: Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Measures standardised: Yes |

Name of intervention: Pivotal response treatment

(PRT) (Koegel, 2011) Intervention valid: Yes Type of play: Parent and child interaction play Place: School Provider: Therapist Duration: 15 hours |

Reported outcome: Internalizing score Category: Negative mental health |

The analysis did not show any treatment effects on internalising score of the INV group on CBCL. |

| Reported outcome: Externalizing score Category: Negative mental health |

The analysis did not show any treatment effects on externalising score of the INV group on CBCL. | |||||

| S10 |

Pilarz

(2009) Publication: PhD Dissertation Country: USA |

Sample size: N = 26 Sample: Children with ASD Age: 3-12 years old Girls: N = 5 (19%) Boys: N = 21 (81%) INV: N = 13 CON: N = 13 |

Design: QE Type of control: Non-randomly allocated control group Control group received treatment: No treatment Measure: The Functional Emotional Assessment Scale (FEAS) (Greenspan, DeGangi & Wieder, (2001). Measures standardised: Yes |

Name of intervention: DIR/Floortime Intervention valid:

Yes Type of play: Parent and child interaction play Place: Not reported Provider: Certified school psychologist Duration: 16 hours |

Reported outcome: Functional Emotional Assessment Score

(FEAS) Category: Positive mental health |

The slopes of the pretest scores for the total scale score did not significantly vary across conditions; p-values ranged from .092 to .549. |

Study designs

The 10 studies comprised RCTs (n = 8) and QEs (n = 2). Overall, RCT studies randomly allocated participants to intervention (n = 224) and control (n = 195) groups and QE studies assigned participants to the intervention (n = 24) and control (n = 26) groups non-randomly. In the majority of studies, participants received either no treatment and then the same treatment as the intervention group on a waiting list (n = 5), treatment as usual (TAU, n = 3), a different intervention (Parent advocacy coaching (PAC), n = 1) or no treatment (n = 1).

Sample sizes of sStudies

The sample size of the included studies ranged between 23 and 128 (mean sample = 47), with a total of 469 participants. Intervention groups’ sample sizes varied from 11 to 64 with a total of 248 participants, while control groups’ samples were between 7 and 64 with a total of 221 children. Of the total sample, 386 were boys (82%) and 83 were girls (18%). Of the included studies, seven were focused on childhood with an age range of 2 to 12, while the other three studies focused on late childhood and adolescence with their samples’ ages ranging from 8 to 16.

Participant identification

All studies were conducted with children with ASD with two being focused on children with “high functioning” ASD. There was no study reporting any other type of social, communication, and or language impairment or used participants with multiple diagnoses. To confirm children's ASD diagnosis, eight out of the 10 studies used additional autism screening tools. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule - Generic (ADOS-G, Lord et al., 2000) was the most commonly used measure as six of the included studies (Siller et al., 2014; Corbett et al., 2017; Solomon et al., 2014; Duifhuis et al., 2017; Ioannou et al., 2020; Doernberg et al., 2021) used this scale to test the autistic traits of their sample. ADOS-G is a gold standard, semi-structured, standardised observational tool administered by a clinician or researcher that focuses on children's social, communication, and cognitive skills. It consists of two domains, namely social and communication domains with four distinct sections which serve to diagnose children at different language levels. The ADOS-G is suitable to use with children from 2 years old to adulthood and the diagnostic classification relies on two different cutoff values, autism (cutoff = 12) and ASD (cutoff = 8) (Lord et al., 1999). In addition, Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R, Lord et al., 1994) scale was also used by two studies to test the ASD characteristics of their samples (Siller et al., 2014; Doernberg et al., 2021). ADI-R is a semi-structured interview for parents/caregivers of children at risk for possible autism diagnosis. The scale is suitable to use with children from 18 months old to adulthood and consists of 93 items which focuses on three developmental domains: Language/ communication, reciprocal social interactions, and restricted, repetitive and stereotyped behaviours. The ADI-R cutoff values for autism diagnosis are as follows: Social interaction (cutoff = 10), communication and language (cutoff = 7–8) and restricted/repetitive behaviours (cutoff = 3). Moreover, the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS, Schopler et al., 1986), Social Responsiveness Scale–2nd Edition (SRS-2; Constantino & Gruber, 2012), and Early Social Communication Scale (ESCS, Seibert et al., 1982) were the other measures that were used in some studies, respectively; Pajareya and Nopmaneejumruslers (2011), Schottelkorb et al. (2020), and Siller et al. (2014).

Characteristics of play-based interventions

A range of different types of play-based interventions were used in the included studies, such as parent-child interaction play (n = 6), role/pretend play (n = 3), and non-directive play (n = 1). Although nine studies applied named play-based interventions (SENSE, DIR/Floortime, PRT, PLAY Project, CCPT, FPI), only one study used a non-named play intervention (pretend play, see S02). Interventions’ frequencies ranged from once a month to 4 times a week, and the total duration of the interventions ranged from 100 min to 240 h. Three interventions were conducted at participants’ schools, two interventions were conducted at home, two interventions were undertaken outside of school (exact locations were not reported) and one intervention was conducted at a research lab; nevertheless, two papers did not indicate the intervention place. Intervention providers were licensed counsellors (n = 3), therapists (n = 2), researcher/s (n = 2), and not reported (n = 3). Detailed information about the characteristics of the play-based interventions is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the Play-Based Interventions

| Name of the intervention | Type of Play and Leadership Roles | Target age, developmental areas and skills | Core Features of the intervention | Study ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Developmental, Individual-Difference, Relationship-Based (DIR / Floortime®) | Type of Play: Parent-child interaction

play Provider: Therapist Role: Trains the parent Leader: Child Role: Leads the play Mediator: Parent Role: Joins the child's play and supports them according to the therapist's feedback. |

Specifically developed for children with ASD:

Yes Age: Early childhood Developmental Area: Functional and Emotional Development Targeted skills: 1-Auditory processing 2-Visual–spatial processing 3-Tactile processing 4-Motor planning 5-Sensory modulation |

The DIR / Floortime is a developmental,

individual-difference, and relationship-based approach

that was introduced by (Greenspan &

Wieder (1997). It is a child-centered,

parent-mediated play intervention that aims to support

children's social functioning, and emotional and

language development. The DIR / Floortime intervention targets children in their early childhood years who show delay in their developmental progression and provides them a range of support according to their developmental needs (Pajareya and Nopmanejumruslers, 2011). In the DIR / Floortime intervention, first, the parent(s) attend initial training sessions about the principles of DIR/Floortime. During sessions, the therapist trains the parents and other individuals, who play a role in the child's everyday life, about how to set a playground in their home to play with their children, how to extend parent-child interaction their play, and increase circles of social communication and interaction between them (Pilarz, 2009) |

S04, S10 |

| The Pivotal Response Treatment (PRT) | Type of Play: Parent-child interaction

play Provider: Therapist Role: Trains the parent Leader: Child Role: Leads the play Mediator: Parent Role: Joins the child's play and supports them according to the therapist's feedback. |

Specifically developed for children with ASD:

Yes Age: Early childhood Developmental Area: Social and Emotional Development Targeted skills: 1- Motivation 2- Self-initiation, 3- Self-Management 4- Responsiveness to multiple cues 5- Empathy |

The PRT is a play-based intervention that was developed

by Koegel et al., (1987) to increase motivation while

teaching new skills to children with ASD. It targets

five pivotal skills of children with ASD: motivation,

self-initiation, self-management, and responsiveness to

multiple cues, and empathy (Koegel et al.,

1987). The PRT has been shown effective in improving social, communication skills and reducing behaviour problems in children with ASD (Rezai et al., 20018). In the PRT sessions, first, the therapist teaches parents how to use the PRT techniques while the child gets used to the therapist. Second, the therapist and parents discuss the developmental needs of the child and set the therapy goals. Third, the parents start to play with their children using the PRT techniques under the therapist's supervision.Fourth, the therapist explains the other possible ways that the parents can apply the PRT techniques into the daily life activities at home. Lastly, the therapist gives the parents videotaped and written feedback about how to improve their PRT skills and apply them in a different range of activities (Duifhuis, 2017). |

S05, S09 |

| The Play and Language for Autistic Youngsters (PLAY) Project Home Consultation | Type of Play: Parent-child interaction

play Provider: Therapist Role: Trains the parent Leader: Child Role: Leads the play Mediator: Parent Role: Joins the child's play and supports them according to the therapist's feedback |

Specifically developed for children with ASD:

Yes Age: Early childhood Developmental Area: Social and Functional Development Targeted skills: 1- Social reciprocity 2- Social competency 3- Child's autism symptomatology (autistic traits) |

The PLAY Project was developed by Solomon et al. (2007)

based on the DIR / Floortime approach (Greenspan & Wieder, 1997) which aims to

help the parents to connect with their own child with

ASD. The PLAY is a child-centred, parent-mediated intervention that targets to improve social development and reduce autism symptomatology of children with ASD. In the PLAY, the therapist/consultant trains the parent about how to interact with their child with ASD “through coaching, modelling, and video feedback. During coaching, consultants help parents identify their child's subtle and hard to detect cues, respond contingently to the child's intentions, and effectively engage the child in reciprocal exchanges” (Solomon et al., 2014, p. 478). |

S07 |

| The Focused Playtime Intervention (FPI) | Type of Play: Parent-child interaction

play Provider: Therapist Role: Observes, guides, models, and provides feedback to the parent Leader: Child Role: Plays independently Mediator: Parent Role: Joins the child's play and guides and supports the child's social responsiveness and communication attempts |

Specifically developed for children with ASD:

Yes Age: Early childhood Developmental Area: Social - Communication Development, Attachment Targeted skills: 1- Attachment skills 2- Social responsiveness 3- Child's spoken communication skills |

The FPI is a home-based naturalistic intervention that

was developed by Siller et al.

(2013). It aims to provide a naturalistic

playground to the child to understand the child's

developmental stage to set parents’ goals and plan a

play environment that would support communication and

attachment behaviours of the child (Siller et al., 2014). The FPI is a family-centred, parent-mediated intervention that targets responsive parental communication to improve participatory and attachment skills of the child in a naturalistic play setting in their homes. In the FPI, parent advocacy coaching sessions hold in their homes, in which the consultant helps the parents to understand their child's developmental needs, guides them to initiate functional and meaningful social interactions during the play with their child, and trains them about how to respond their child's social-communication attempts in a naturalistic way during their playtime (Siller et al., 2013). |

S08 |

| The Social Emotional NeuroScience Endocrinology Theatre® (SENSE) | Type of Play: Role / Pretend play Provider: Therapist Role: Trains the peers to support the child with ASD during their role play Leader: Child Role: Demonstrates role play Mediator: Peers Role: Join the child's play to encourage and motivate their friend with ASD, and provide a warm social environment to them. |

Specifically developed for children with ASD:

Yes Age: Early childhood Developmental Area: Social, Cognitive and Emotional Development Targeted skills: 1- Imagination 2- Theory of mind 3- Social competence |

The SENSE is a theatre-based play intervention that was

developed by Corbett et al. (2011) and targets social

and emotional functioning in children with

ASD. The SENSE is designed as a peer-mediated intervention that aims to improve social competence and reduce the stress level of children with ASD with an intensive peer support. SENSE includes theatrical games, role-playing, and exercises in which children work on their roles for the play (Corbett et al., 2017). In the SENSE, peers receive training on ten core principles (Corbett et al., 2014) that are mainly about how to socially support the child with ASD, provide them with a warm social environment, and engage in positive social interactions with them. Following the training, peers and the child with ASD engage in role-playing activities under the guidance of the interventionist. While performing role-play, children with ASD experience positive social interactions, develop their level of imagination and TOM skills, learn how to engage with their peers, and respond to social invitations (Ioannou et al., 2020). |

S01, S03 |

| The Child-Centered Play Therapy (CCPT) | Type of Play: Non-directive play Provider: Therapist Role: Joins the child during their play, follows the child's leadership, and reflects the child's emotions. Leader: Child Role: Leads the play Mediator: None |

Specifically developed for children with ASD:

No Age: Early childhood Developmental Area: Social, Emotional and Behavioural Development Targeted skills: 1- Attachment skills 2- Emotional regulation 3- Emotional recognition 4- Self-control 5- Self-regulation 6- Social competence |

The CCPT is a naturalistic and therapeutic intervention

that was firstly introduced by Axline (1947)

based on Carl Rogers's client-based psycho-therapy

principles. It is a theoretically grounded intervention

that targets children's emotional and behavioural

problems. The CCPT is a child-centered, non-directive approach that aims to help children to explore and express their deep feelings, emotions, and thoughts during a free play session. During the CCPT, the therapist develops a warm and friendly relationship with the child, accept the child unconditionally, provide them a suitable atmosphere to freely express their feelings, reflect their feelings, believe in the child's problem-solving potential, does not direct or limit the child unless it is necessary (Axline, 1969, p.73). In the CCPT, the therapist creates a play environment that would suit CCPT principles. At the beginning of the session, the therapist informs the child about the time of the play. During the play, the therapist follows the child's lead and takes notes about the play themes, play behaviours, verbalisations, expressed emotions and informs the parents accordingly after each session (Schottelkorb et al., 2020). |

S06 |

| Pretend Play | Type of Play: Pretend / Symbolic play Provider: Therapist Role: Joins the child during their pretend-play activity, follows the child's leadership, and reflects the child's emotions. Leader: Child Role: Leads the play Mediator: None |

Specifically developed for children with ASD:

No Age: Early childhood Developmental Area: Social, Emotional and Cognitive Development Targeted skills: 1- Imagination 2- Perspective taking 3- Affect expression 5- Social communication 6- Prosociality |

Pretend play is a common type of play that is closely

related to a range of cognitive abilities of a child

such as symbolic functioning, memory, and imagination.

Children start pretend-playing (make-believe) at around

2, and become masters in pretend play at around 4 years

of age (Piaget,

1952). The Pretend play intervention is a child centred play intervention that targets the child's imaginative skills, expressed emotions, verbalisation, and role-play skills. In the pretend play intervention, in which the therapist creates a free play environment with unstructured toys for the child. During the intervention, the therapist joins the child's play, follows the child's lead, uses prompts, and reflects the child's emotions to help children to developing new skills such as making up new things, creating stories, and to improve their level of imagination and organisation (Doernberg et al., 2021). |

S02 |

Mental health outcomes

Of the included studies, five studies used parent-report, three used self-report, and four used observational scales to test the effectiveness of the play-based interventions on the mental health outcome of children with ASD. In terms of measuring the negative mental health outcomes, the researchers used the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAI-C, Spielberger et al., 1983) to measure the anxiety level of children with ASD. In addition, the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL, Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) was used to measure internalising and externalising problems, the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC, Aman et al., 1985) was used to test irritability and hyperactivity, and the Kusche Affective Inventory-Revised (KAI-R, Kusche et al., 1988) was used to measure total negative affect. In terms of testing the positive mental health outcomes; however, the Functional Emotional Assessment Scale (FEAS, Greenspan et al., 2001) was used to assess emotional functioning; the Functional Emotional Developmental Questionnaire (FEDQ, Greenspan & Greenspan, 2002) was used to assess emotional development; the Proximity and Contact Seeking Behaviors (PCSB, Ainsworth, 1978) and Maternal Perceptions of Child Attachment Scales (MPCA, Hoppes and Harris, 1990) were used to evaluate children's attachment-related behaviours; and the KAI-R scale was used to measure total positive affect in children with ASD. The measures noted are well-used standardised measures of the relevant concepts. More information about the mental health classifications of the reported outcomes and the outcome measures can be found in Appendix D.

Geographical location of studies

Studies were undertaken in the United States of America (n = 7), Thailand (n = 1), Netherlands (n = 1), and Iran (n = 1).

Risk of bias