Key Points

Question

Do patients with resected melanoma at high risk for relapse have improved quality of life when treated with adjuvant pembrolizumab vs standard of care with ipilimumab or high-dose interferon α 2b (HDI)?

Findings

In this phase 3 randomized clinical trial including 1303 eligible patients, those randomized to treatment with pembrolizumab compared with ipilimumab/HDI had statistically significantly improved quality-of-life outcomes according to multiple validated measures. The primary end point of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Biologic Response Modifiers trial outcome index score was 9.6 points higher for pembrolizumab at the pre-specified cycle 3 assessment time, exceeding the hypothesized difference of 5.0 points.

Meaning

The trial results found that treatment with adjuvant pembrolizumab improved quality of life vs treatment with adjuvant ipilimumab or HDI in patients with high-risk resected melanoma.

Abstract

Importance

A key issue for the adjuvant treatment of patients with melanoma is the assessment of the effect of treatment on relapse, survival, and quality of life (QOL).

Objective

To compare QOL in patients with resected melanoma at high risk for relapse who were treated with adjuvant pembrolizumab vs standard of care with either ipilimumab or high-dose interferon α 2b (HDI).

Design, Setting, and Participants

The S1404 phase 3 randomized clinical trial was conducted by the SWOG Cancer Research Network at 211 community/academic sites in the US, Canada, and Ireland. Patients were enrolled from December 2015 to October 2017. Data analysis for this QOL substudy was completed in March 2022. Overall, 832 patients were evaluable for the primary QOL end point.

Interventions

Patients were randomized (1:1) to treatment with adjuvant pembrolizumab vs standard of care with ipilimumab/HDI.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Quality of life was assessed for patients at baseline and cycles 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 after randomization using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) Biological Response Modifiers (FACT-BRM), FACT-General, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Diarrhea, and European QOL 5-Dimension 3-Level scales. The primary end point was the comparison by arm of cycle 3 FACT-BRM trial outcome index (TOI) scores using linear regression. Linear-mixed models were used to evaluate QOL scores over time. Regression analyses included adjustments for the baseline score, disease stage, and programmed cell death ligand 1 status. A clinically meaningful difference of 5 points was targeted.

Results

Among 1303 eligible patients (median [range] age, 56.7 [18.3-86.0] years; 524 women [40.2%]; 779 men [59.8%]; 10 Asian [0.8%], 7 Black [0.5%], 44 Hispanic [3.4%], and 1243 White [95.4%] individuals), 1188 (91.1%) had baseline FACT-BRM TOI scores, and 832 were evaluable at cycle 3 (ipilimumab/HDI = 267 [32.1%]; pembrolizumab = 565 [67.9%]). Evaluable patients were predominantly younger than 65 years (623 [74.9%]) and male (779 [58.9%]). Estimates of FACT-BRM TOI cycle 3 compliance did not differ by arm (ipilimumab/HDI, 96.0% vs pembrolizumab, 98.3%; P = .25). The adjusted cycle 3 FACT-BRM TOI score was 9.6 points (95% CI, 7.9-11.3; P < .001) higher (better QOL) for pembrolizumab compared with ipilimumab/HDI, exceeding the prespecified clinically meaningful difference. In linear-mixed models, differences by arm exceeded 5 points in favor of pembrolizumab through cycle 7. In post hoc analyses, FACT-BRM TOI scores favored the pembrolizumab arm compared with the subset of patients receiving ipilimumab (difference, 6.0 points; 95% CI, 4.1-7.8; P < .001) or HDI (difference, 17.0 points; 95% CI, 14.6-19.4; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

This secondary analysis of a phase 3 randomized clinical trial found that adjuvant pembrolizumab improved QOL vs treatment with adjuvant ipilimumab or HDI in patients with high-risk resected melanoma.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02506153

This randomized clinical trial examines quality of life in patients with resected melanoma at high risk for relapse who were treated with adjuvant pembrolizumab vs standard of care with either ipilimumab or high-dose interferon α 2b.

Introduction

An important issue in the adjuvant treatment of patients with high-risk melanoma is how patients weigh the benefits of recurrence-free survival (RFS), overall survival (OS), and quality of life (QOL). Adjuvant high-dose interferon (HDI) improves RFS for this patient population but is known to be associated with major grade 3 to 4 toxic effects and impaired QOL.1,2,3 Ipilimumab, a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4–blocking antibody, has been shown to provide longer RFS in resectable high-risk melanoma, but to result in potentially dose-limiting toxic effects. In a trial comparing ipilimumab with a masked placebo, patients treated with ipilimumab experienced severe (grade ≥3) gastrointestinal (16%), hepatic (11%), and endocrine (8%) adverse events (AEs), contributing to treatment discontinuation in half of patients treated with ipilimumab.4 Anti–programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) agents as monotherapy have a more favorable toxic effect profile and have proven to be more efficacious compared with ipilimumab in the advanced and adjuvant settings.5,6,7,8 Yet, these drugs can also result in acute and occasionally irreversible immune-related toxic effects.8,9,10

In a setting with potentially complex tradeoffs that consider efficacy, risk reduction, and QOL, a comprehensive evaluation of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) is vital for aiding in decision-making between patients and physicians. Patient-reported outcomes are standardized measures used to collect patients’ direct experience of treatment, including symptom burden and QOL. Their use informs the interpretation of treatment outcomes, especially given the limitations of physician reporting for symptomatic and subjective AEs.11 Physicians may underreport symptomatic AEs by up to 50%.12 Moreover, overall QOL is not reflected in standard physician AE reporting, but is important to patients.13 Thus, PROs represent an important component of the patient experience of cancer care, particularly in the resected setting, in which many patients are already cured with treatment with local therapy.

We previously reported the clinical findings of SWOG S1404, an intergroup, randomized phase 3 clinical trial in patients with high-risk melanoma that examined whether adjuvant pembrolizumab improved clinical outcomes compared with standard care with physician/patient choice of adjuvant ipilimumab or high-dose interferon-α 2b (HDI).7 The study showed that patients treated with pembrolizumab had statistically significantly longer RFS, with a 23% reduction in risk of relapse. In this article, we report on QOL outcomes by arm for patients with resected melanoma treated with adjuvant pembrolizumab vs ipilimumab/HDI.

Methods

Patient Selection and Study Design

The S1404 phase 3 randomized clinical trial was conducted by the SWOG Cancer Research Network at 211 community/academic sites in the US, Canada, and Ireland (Supplement 1). Detailed eligibility for S1404 was previously reported.7 Key eligibility criteria included patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th edition stage IIIA (N2a), IIIB, IIIC, or IV melanoma of nonocular origin who had undergone complete surgical resection.14 Prior use of immunotherapy was not permitted.7 Under the initial design, pembrolizumab was compared with HDI. After US Food and Drug Administration approval of adjuvant ipilimumab in October 2015, the design was amended (in April 2016) to add the choice of ipilimumab; further details, including dosing, were previously reported.7 Patients were randomized 1:1 using block randomization using the National Cancer Institute web-based OPEN platform and stratified according to stage, programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) melanoma staining, and the planned standard-of-care regimen. Patients who were able to complete questionnaires in English, Spanish, or French were required to participate in the QOL assessment.

Patients were required to provide written informed consent to participate. The study protocol was approved by the National Cancer Institute central institutional review board and at each institution. This report followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline, as well as international guidelines for PRO reporting.15,16

Timing of QOL Assessments

The QOL assessments were collected at baseline and cycles 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 (corresponding per protocol to weeks 4, 13, 25, 37, and 49), as well as at 24 and 48 weeks after protocol treatment discontinuation. At each assessment, QOL instruments were administered before all other study procedures. An additional assessment was collected at the time of recurrence. Assessments were indexed by cycle number.

QOL Questionnaires

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) Biologic Response Modifiers (FACT-BRM) represents 4 domains comprising the FACT-General (FACT-G) subscales, including physical, social/family, emotional, and functional well-being, and 2 additional subscales, the BRM physical subscale and the BRM cognitive/emotional subscale.17 Each subscale is derived from 6 to 7 items on the questionnaire, with responses given on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 4 (0 = not at all; 1 = a little bit; 2 = somewhat; 3 = quite a bit; 4 = very much). Combined, the 6 subscales form a single FACT-BRM total score. The FACT-BRM trial outcome index (TOI) is derived from the physical well-being, functional well-being, BRM physical, and BRM cognitive/emotional subscales.

The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Diarrhea (FACIT-D) comprises the FACT-G and a symptom-specific subscale that measures QOL related to diarrhea.18 The FACIT-D items are also scored on 5-point Likert-type scales that range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating better QOL. The FACIT-D total score, TOI, and diarrhea subscale were analyzed.

The European QOL 5-Dimension 3-Level (EQ-5D-3L) scale is a descriptive system assessing 3 functional domains (mobility, self-care, and usual activities) and 2 symptom domains (pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression), each domain with 3 levels (no problems, some problems, extreme problems).19 The domains were combined into a single summary index.20 Additionally, a visual analog system recorded self-rated global health between the best imaginable health state and worst imaginable health state.21 For each included instrument and its subscales, the higher the score, the better the QOL.

Statistical Analyses

The primary end point was the FACT-BRM TOI score at cycle 3 using all eligible randomized patients (within intent to treat) who were evaluable for QOL assessment. Cycle 3 was chosen as the earliest assessment time that would adequately reflect the cumulative effect of treatment while also minimizing potential differences in attrition between arms.4,9 Evaluable patients had a baseline and cycle 3 assessment. Compliance was determined as the number of patients by arm at cycle 3 who provided sufficient data to score the FACT-BRM TOI, divided by the number expected to complete the instrument (that is, excluding patients who died or experienced recurrence). Thus, the design targeted the experience of evaluable patients who were still receiving active treatment.

The standard deviation was assumed to be 20 points.17,22 The estimated FACT-BRM TOI minimally important difference is 5 to 8 points, which is consistent with an effect size of 0.25 to 0.40 points using distribution-based methods.23 A 5-point difference was targeted. In this study of 1240 anticipated eligible patients, at cycle 3, 20% of patients were assumed to drop out and 10% were assumed to be nonadherent, reducing the nominal effect size by 10%. Using a 2-sided α of .05 and 2-arm normal design, 94% power was anticipated.

The cycle 3 FACT-BRM TOI score was analyzed using multivariable linear regression analysis, adjusting for the randomization stratification factors and the baseline FACT-BRM TOI score. Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute), and R, version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Additional Analyses

The FACT-BRM TOI score was also evaluated at cycles 1, 5, 7, and 9. The remaining instruments and domains were also evaluated at each cycle. Each of these analyses was conducted using linear regression analysis with covariate adjustment for the baseline score and the stratification factors.

Changes over time were analyzed using linear mixed models, with individual patients treated as random effects. Adjustment covariates included treatment arm, assessment time, the baseline score, and the randomization stratification variables. Additionally, the interactions of treatment with time and treatment with time squared were examined. Because models were nested, we compared log-likelihood values using χ2 tests with appropriate degrees of freedom to determine which model provided a best fit; if multiple models were identified, preference was given to the higher order model.

Given the likelihood of informative missing data (because, by design, PRO evaluations were discontinued at recurrence), pattern mixture models (which condition the type of missingness pattern through covariate adjustment) were used as a sensitivity analysis.24,25,26 Appropriate missingness patterns were identified using cohort plots.

Post Hoc Analyses

To aid interpretation, we examined the FACT-BRM TOI cycle 3 scores comparing pembrolizumab with the subset of patients in the standard care arm who were receiving ipilimumab and, separately, the subset receiving HDI. Comparisons by arm were also examined within levels of the stratification variables. In a sensitivity analysis, any cycle 3 QOL assessments occurring at recurrence were excluded to evaluate whether assessments possibly administered after the reporting of recurrence to patients may have biased estimates by arm.

Results

Eligibility and Primary End Point Evaluability

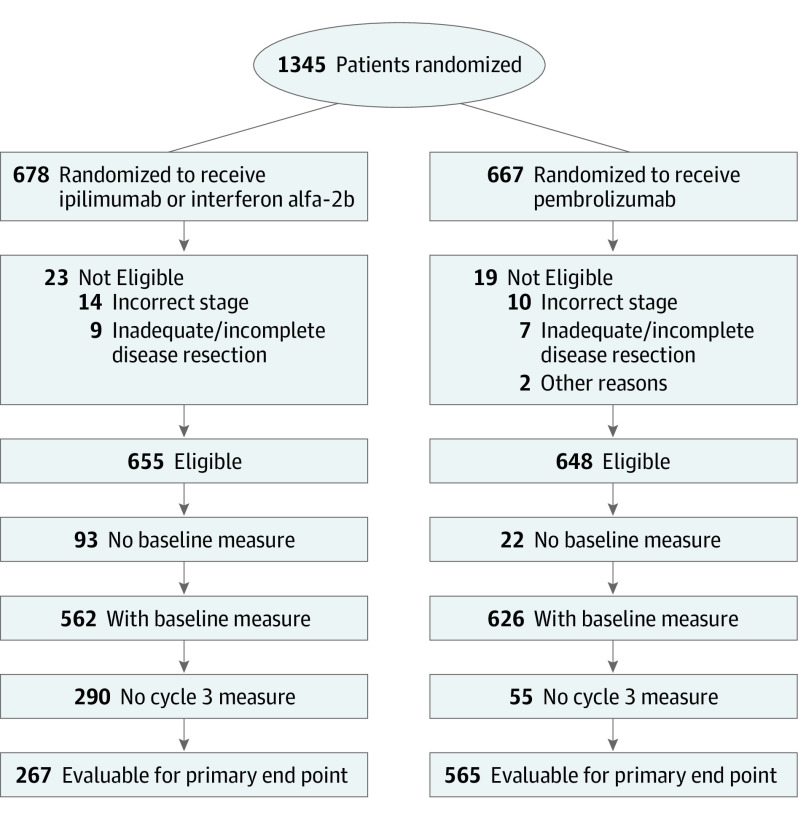

Overall, 1345 patients were randomized from December 2015 to October 2017, with 42 ineligible, leaving 1303 eligible patients (678 [52.0%] in the ipilimumab/HDI arm and 667 [48.0%] in the pembrolizumab arm) (Figure 1). The trial reached full accrual. An imbalance in receipt of baseline questionnaires between patients randomized to treatment with pembrolizumab (626 of 648 [96.6%]) vs ipilimumab/HDI (562 of 655 [85.8%]) reflected the relatively large number of patients in the ipilimumab/HDI arm who refused assigned treatment.7 The proportion of patients evaluable for the primary end point assessment at cycle 3 was 565 of 648 (87.2%) in the pembrolizumab arm and 267 of 655 (40.8%) in the ipilimumab/HDI arm. This difference is primarily because of the protocol-specified design strategy for PRO data collection, which required form submission only until progression. Thus, protocol-defined FACT-BRM TOI cycle 3 compliance rates did not differ by arm (267 of 276 [96.7%] for ipilimumab/HDI and 565 of 575 [98.3%] for pembrolizumab; P = .25). For both arms, FACT-BRM TOI compliance rates also exceeded 90% for cycles 1, 5, 7, and 9.

Figure 1. Patient Flow Diagram for the Primary End Point Assessment of the FACT-BRM TOI Scores at Cycle 3.

FACT-BRM TOI indicates Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Biological Response Modifiers trial outcome index.

Patient Characteristics

There were no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics between patients with vs without an available cycle 3 FACT-BRM TOI score (Table 1). Patients evaluable for the primary end point assessment (n = 832) were primarily younger than 65 years (623 [74.9%]) and male (490 [58.9%]). Patients were predominantly White (802 [96.4%]) and not Hispanic (785 [94.4%]). In evaluable patients, there were no statistically significant differences in patient characteristics by arm.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics Overall and by FACT-BRM TOI Baseline and Week 13 Score Availability.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All eligible | Baseline FACT-BRM TOI score available | By whether the cycle 3 FACT-BRM TOI score was available | By arm for patients with baseline and cycle 3 FACT-BRM TOI scores available | |||||

| Not available | Available | P value | Ipilimumab/HDI | Pembrolizumab | P valuea | |||

| No. | 1303 | 1188 | 356 | 832 | NA | 267 | 565 | NA |

| Age, median (range), y | 56.7 (18.3-86.0) | 56.6 (18.3-86.0) | 56.2 (18.7-84.5) | 56.7 (18.3-86.0) | NA | 56.8 (18.3-86.0) | 56.3 (20.0-82.6) | NA |

| <65 | 970 (74.4) | 881 (74.2) | 258 (72.5) | 623 (74.9) | .39 | 190 (71.2) | 433 (76.6) | .09 |

| >65 | 333 (25.6) | 307 (25.8) | 98 (27.5) | 209 (25.1) | NA | 77 (28.8) | 132 (23.4) | NA |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 524 (40.2) | 481 (40.5) | 139 (39.0) | 342 (41.1) | .51 | 113 (42.3) | 229 (40.5) | .62 |

| Male | 779 (59.8) | 707 (59.5) | 217 (61.0) | 490 (58.9) | NA | 154 (57.7) | 336 (59.5) | |

| Raceb | ||||||||

| Asian | 10 (0.8) | 6 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | 4 (0.5) | NA | 1 (0.4) | 3 (0.5) | .34 |

| Black | 7 (0.5) | 5 (0.4) | 0 | 5 (0.6) | .10 | 3 (1.1) | 2 (0.4) | |

| White | 1243 (95.4) | 1139 (95.9) | 337 (94.7) | 802 (96.4) | NA | 255 (95.5) | 547 (96.8) | |

| Other/unknown | 43 (3.3) | 38 (3.2) | 17 (4.8) | 21 (2.5) | NA | 8 (3.0) | 13 (2.3) | |

| Ethnicityc | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 44 (3.4) | 33 (2.8) | 10 (2.8) | 23 (2.8) | >.99 | 8 (3.0) | 15 (2.7) | .33 |

| Not Hispanic | 1223 (93.9) | 1121 (94.4) | 336 (94.4) | 785 (94.4) | NA | 248 (92.9) | 537 (95.0) | |

| Unknown | 36 (2.8) | 34 (2.9) | 10 (2.8) | 24 (2.9) | NA | 11 (4.1) | 13 (2.3) | |

| Performance status | ||||||||

| 0 | 1091 (83.7) | 1005 (84.6) | 297 (83.4) | 708 (85.1) | .47 | 233 (87.3) | 475 (84.1) | .23 |

| 1 | 212 (16.3) | 183 (15.4) | 59 (16.6) | 124 (14.9) | NA | 34 (12.7) | 90 (15.9) | |

| Staged | ||||||||

| IIIA | 144 (11.1) | 132 (11.1) | 41 (11.5) | 91 (10.9) | .29 | 27 (10.1) | 64 (11.3) | .45 |

| IIIB | 637 (48.9) | 585 (49.2) | 400 (48.1) | NA | 126 (47.2) | 274 (48.5) | ||

| IIIC | 443 (34.0) | 400 (33.7) | 115 (32.3) | 285 (34.3) | NA | 95 (35.6) | 190 (33.6) | |

| IV | 79 (6.1) | 71 (6.0) | 15 (4.2) | 56 (6.7) | NA | 19 (7.1) | 37 (6.5) | |

| PD-L1 statusc | ||||||||

| Positive | 1070 (82.1) | 979 (82.4) | 290 (81.5) | 689 (82.8) | .79 | 218 (81.6) | 471 (83.4) | .63 |

| Negative | 188 (14.4) | 171 (14.4) | 53 (14.9) | 118 (14.2) | NA | 42 (15.7) | 76 (13.5) | |

| Indeterminate | 45 (3.5) | 38 (3.2) | 13 (3.7) | 25 (3.0) | NA | 7 (2.6) | 18 (3.2) | |

Abbreviation: FACT-BRM, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Biological Response Modifiers; HDI, high-dose interferon α 2b; NA, not applicable; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; TOI, trial outcome index.

Differences between groups tested using χ2 test, unless otherwise specified.

Represents a test of White vs racial and ethnic minority groups. Race was categorized by self-report.

Statistical significance of χ2 statistics indicates heterogeneity by availability of baseline FACT-BRM TOI across nonordered categories. Ethnicity was categorized by self-report.

Used Mantel-Haenszel test for trend to test group differences based on linear ordering (ie, ordinal categorical variable) of stage groups.

Primary Outcome

Baseline measures of the FACT-BRM TOI score were similar between treatment arms (ipilimumab/HDI = 91.9 vs pembrolizumab = 91.9; eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Compared with baseline, the mean observed FACT-BRM TOI score was 1.8 points lower at cycle 3 in the pembrolizumab arm and 11.3 points lower in the ipilimumab/HDI arm. The model-adjusted cycle 3 FACT-BRM TOI score was 9.6 points (95% CI, 7.9-11.3; P < .001; Table 2) higher (improved QOL) for patients in the pembrolizumab arm compared with the ipilimumab/HDI arm. The magnitude of this effect exceeded the prespecified clinically meaningful difference of 5 points.

Table 2. Cycle 3 Patient-Reported Outcomes by Arm.

| PRO measure | No. | Observed mean (95% CI) | Fitted difference (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Cycle 3 | Pembrolizumab vs ipilimumab/HDI | P value | ||

| FACT-BRM | |||||

| Trial outcome index | |||||

| Ipilimumab/HDI | 267 | 91.9 (90.5-93.4) | 80.6 (78.4-82.9) | NA | NA |

| Pembrolizumab | 565 | 92.1 (91.0-93.2) | 90.3 (89.2-91.5) | 9.6 (7.9-11.3) | <.001 |

| Total score | |||||

| Ipilimumab/HDI | 267 | 135.6 (133.5-137.6) | 124.4 (121.5-127.2) | NA | NA |

| Pembrolizumab | 563 | 135.7 (134.3-137.2) | 134.9 (133.3-136.4) | 10.4 (8.1-12.6) | <.001 |

| Physical subscale | |||||

| Ipilimumab/HDI | 271 | 24.4 (24.0-24.8) | 21.2 (20.6-21.8) | NA | NA |

| Pembrolizumab | 575 | 24.4 (24.1-24.6) | 23.7 (23.4-24.0) | 2.5 (2.0-3.0) | <.001 |

| Cognitive/emotional subscale | |||||

| Ipilimumab/HDI | 271 | 19.4 (19.0-19.9) | 17.9 (17.3-18.5) | NA | NA |

| Pembrolizumab | 575 | 19.2 (18.9-19.5) | 19.2 (18.8-19.5) | 1.5 (1.0-2.0) | <.001 |

| FACT-G | |||||

| Total score | |||||

| Ipilimumab/HDI | 269 | 91.8 (90.3-93.2) | 85.5 (83.6-87.3) | NA | NA |

| Pembrolizumab | 566 | 92.1 (91.1-93.1) | 91.9 (90.8-93.0) | 6.2 (4.6-7.8) | <.001 |

| Physical well-being | |||||

| Ipilimumab/HDI | 270 | 25.8 (25.5-26.2) | 21.5 (20.8-22.2) | ||

| Pembrolizumab | 571 | 26.1 (25.9-26.3) | 24.8 (24.5-25.1) | 3.2 (2.6-3.7) | <.001 |

| Social/family well-being | |||||

| Ipilimumab/HDI | 273 | 24.9 (24.4-25.4) | 24.3 (23.8-24.9) | NA | NA |

| Pembrolizumab | 578 | 24.7 (24.4-25.1) | 24.4 (24.0-24.8) | 0.1 (−0.4-0.7) | .61 |

| Emotional well-being | |||||

| Ipilimumab/HDI | 273 | 18.7 (18.3-19.2) | 19.3 (18.9-19.8) | NA | NA |

| Pembrolizumab | 576 | 18.8 (18.5-19.1) | 20.0 (19.7-20.2) | 0.6 (0.2-1.0) | .01 |

| Functional well-being | |||||

| Ipilimumab/HDI | 273 | 22.3 (21.7-22.9) | 20.2 (19.4-20.9) | NA | NA |

| Pembrolizumab | 577 | 22.4 (22.0-22.8) | 22.6 (22.1-23.0) | 2.3 (1.7-2.9) | <.001 |

| FACIT-D | |||||

| Trial outcome index | |||||

| Ipilimumab/HDI | 132 | 91.0 (89.7-92.4) | 83.5 (81.3-85.6) | NA | NA |

| Pembrolizumab | 289 | 91.3 (90.4-92.3) | 89.6 (88.4-90.7) | 5.8 (4.0-7.6) | <.001 |

| Total score | |||||

| Ipilimumab/HDI | 132 | 134.9 (132.8-137.0) | 127.3 (124.4-130.3) | NA | NA |

| Pembrolizumab | 287 | 134.8 (133.3-136.3) | 134.2 (132.6-135.9) | 6.8 (4.3-9.4) | <.001 |

| Diarrhea subscale | |||||

| Ipilimumab/HDI | 136 | 43.0 (42.6-43.3) | 41.9 (41.3-42.5) | NA | NA |

| Pembrolizumab | 292 | 42.8 (42.5-43.1) | 42.5 (42.1-42.9) | 0.7 (0.0-1.4) | .05 |

| EQ-5D-3L | |||||

| Index score | |||||

| Ipilimumab/HDI | 250 | 0.89 (0.88-0.91) | 0.86 (0.84-0.88) | NA | NA |

| Pembrolizumab | 546 | 0.90 (0.89-0.91) | 0.90 (0.89-0.91) | 0.04 (0.02-0.06) | <.001 |

| Global Health score | |||||

| Ipilimumab/HDI | 264 | 83.6 (81.9-85.2) | 77.1 (74.8-79.3) | NA | NA |

| Pembrolizumab | 565 | 84.9 (83.8-86.0) | 84.6 (83.6-85.6) | 6.7 (4.9-8.5) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: FACT, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy; FACT-BRM, FACT Biological Response Modifiers; FACIT-D, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy diarrhea; FACT-G, FACT general; HDI, high-dose interferon α 2b; PROs, patient-reported outcomes.

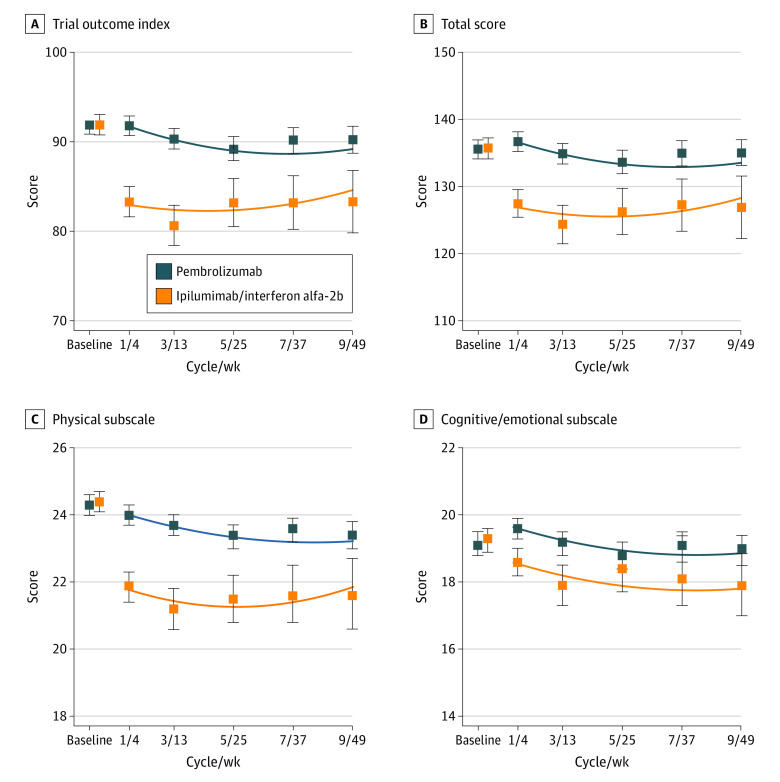

In linear mixed models, a treatment-by-time-squared interaction was evident (Figure 2; eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Model-adjusted scores in favor of pembrolizumab were greater at the first follow-up assessment and were nearly twice as great at cycle 1 (8.8; 95% CI, 7.4-10.2; P < .001) than at cycle 9 (4.6; 95% CI, 2.4-6.8; P < .001; eTable 3 in Supplement 2). Differences in favor of pembrolizumab were highly statistically significant at each assessment time and exceeded the specified clinically meaningful difference for all cycles except cycle 9.

Figure 2. Linear Mixed Model Results for Selected Domains From the FACT-BRM Questionnaire.

The blue and orange boxes indicate the observed mean scores for patients randomized to the pembrolizumab arm vs the ipilimumab/high-dose interferon-α 2b (HDI) arms, respectively, with corresponding 95% CIs indicated by the vertical lines through the boxes. The curvilinear lines indicate the fitted estimates from linear mixed models. Baseline measures are offset for illustration purposes. FACT-BRM indicates Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Biological Response Modifiers.

An analysis of missing data using cohort plots indicated 3 patterns of FACT-BRM TOI scores over time by arm (eMethods in Supplement 2). A similar pattern of larger model-adjusted scores in favor of pembrolizumab at the outset of treatment (cycle 1, 9.7 points; 95% CI, 7.1-12.2; P < .001) compared with cycle 9 (4.9 points; 95% CI, 2.2-7.6; P < .001) was observed. The adjusted treatment difference at cycle 3 was 7.6 points (95% CI, 5.2-9.9; P < .001) in favor of pembrolizumab.

Secondary Cycle-Specific Outcomes

For other assessment times, in individual linear regression models, the model-adjusted FACT-BRM TOI score was 8.5 (95% CI, 7.1-10.0; P < .001), 5.6 (95% CI, 3.7-7.6; P < .001), 5.7 (95% CI, 3.7-7.7; P < .001), and 5.0 (95% CI, 2.6-7.4; P < .001) points lower for patients in the ipilimumab/HDI arm compared with those in the pembrolizumab arm for cycles 1, 5, 7, and 9, respectively (eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

In addition, the FACT-BRM total score, FACT-BRM physical subscale, and FACT-BRM cognitive/emotional subscale were each statistically significantly higher at cycle 3 for patients in the pembrolizumab arm, indicating improved QOL (Table 2). Statistically significantly better scores for patients in the pembrolizumab arm were also observed at all other assessment times (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Statistically significant differences in favor of pembrolizumab were evident for nearly all domains of the FACT-G, FACIT-D, and EQ-5D-3L instruments at cycle 3 and at other cycles (Table 2; eTables 4-6 in Supplement 2).

Longitudinal Assessments of Secondary Scales

The best model for each domain was determined by comparing the log-likelihood statistics from nested models (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). An interaction between treatment and time squared represented the best fit for the FACT-BRM total score and physical subscale, with waning (but still highly statistically significant) differences between arms as time increased (Figure 2; eTable 3 in Supplement 2). The FACT-BRM cognitive/emotional subscale scores varied over time in a quadratic fashion, but were constant by arm, favoring pembrolizumab. The effect of treatment differed over time (ie, interaction) for the FACT-G total score and FACT-G physical, emotional, and functional well-being subscale scores; statistically significant differences uniformly favored the pembrolizumab arm at all assessment times. For the social well-being subscale, no interaction was evident; differences by arm were only marginally statistically significant (0.4 points; 95% CI, 0-0.7; P = .05). An interaction of quadratic time and treatment was also apparent for the FACIT-D TOI and FACIT-D total score, with larger initial differences that waned over time. A small but statistically significant difference in the FACIT-D diarrhea subscale was constant (linear) over time. The EQ-5D-3L index score also favored the pembrolizumab arm, with highly statistically significant differences that were constant over time. Trends in the EQ-5D-3L global quality of life score also favored pembrolizumab, but estimates differed over time.

Post Hoc Analyses

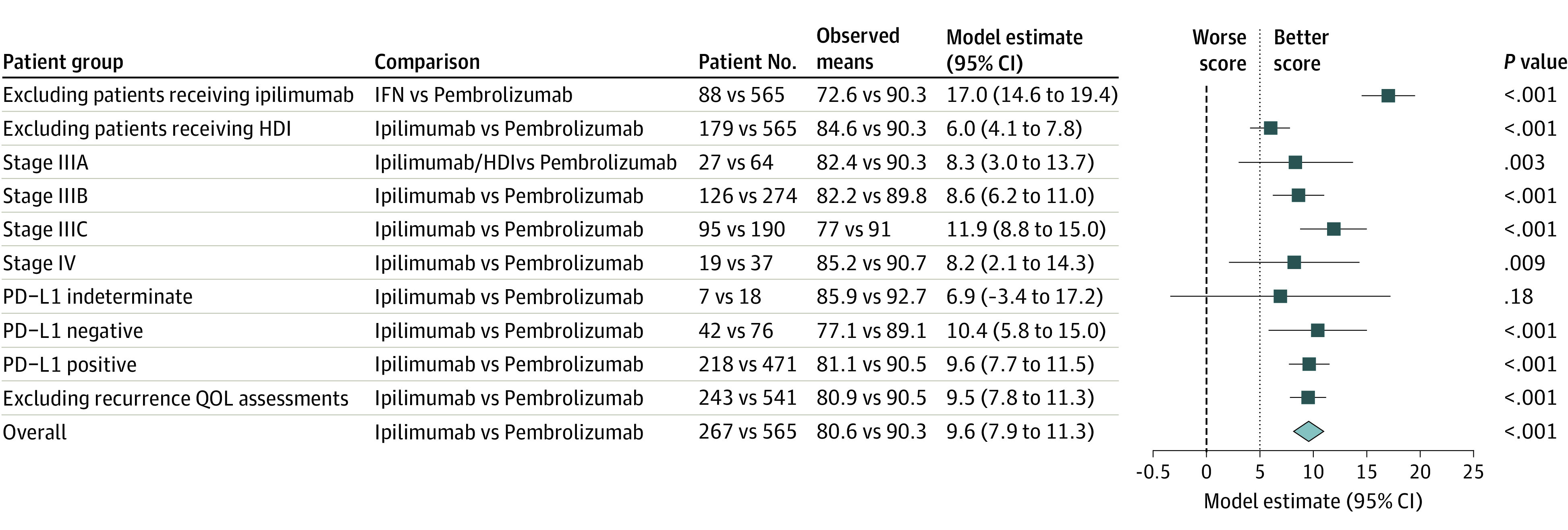

Patients randomized to the pembrolizumab arm had better cycle 3 FACT-BRM TOI scores compared with the subset of patients randomized to standard care who received ipilimumab (6.0 points; 95% CI, 4.1-7.8; P < .001) and the subset who received HDI (17.0 points; 95% CI, 14.6-19.4; P < .001); both differences exceeded the target clinically meaningful difference of 5.0 points (Figure 3). Statistically significant differences exceeding the target difference of 5 points in favor of pembrolizumab were evident among all categories of the stratification variables, except for patients with PD-L1 indeterminate status, likely because of small numbers and limited power (6.9 points; 95% CI, −3.4 to 17.2; P = .18). The exclusion of cycle 3 assessments coinciding with a recurrence had little effect on the estimate of benefit in favor of pembrolizumab (9.5 points; 95% CI, 7.8-11.3; P < .001).

Figure 3. Results of Post Hoc Analyses of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Biological Response Modifiers (FACT-BRM) Trial Outcome Index (TOI) Score at Cycle 3 in Different Subgroups of Patients.

The blue boxes show the multivariable linear regression model–derived point estimates (adjusting for the stratification factors and the baseline score) for the group comparisons, and the horizontal lines show the corresponding 95% CIs. The bold, dashed vertical line indicates the 0 value representing no difference between groups, while the light dotted vertical line shows the value of 5 points between groups, in favor of patients randomized to the pembrolizumab arm and corresponding to the design-specified clinically meaningful difference in FACT-BRM TOI scores. HDI indicates high-dose interferon α 2b; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; QOL, quality of life.

Discussion

To our knowledge, S1404 is the largest published adjuvant anti-PD-1 monotherapy study in melanoma. We found that QOL end points for patients randomized to receive treatment with pembrolizumab were superior than those of patients randomized to treatment with ipilimumab/HDI. At the prespecified primary end point assessment at cycle 3, the adjusted FACT-BRM TOI score was 9.6 points higher (better QOL) for patients in the pembrolizumab arm compared with patients in the standard arm, substantially exceeding the target of 5.0 points. Additionally, an overall benefit in favor of pembrolizumab was affirmed using longitudinal analyses of assessments through cycle 9, and QOL scores favored pembrolizumab when compared with the subset of patients who received ipilimumab and the subset who received HDI.

The benefit of immune checkpoint blockade as adjuvant treatment for high-risk melanoma has been demonstrated in multiple randomized clinical trials. In 2015, ipilimumab was shown to improve RFS compared with placebo in EORTC 18071.4 Some patient-reported symptom domains (diarrhea, insomnia) were worse among patients in the ipilimumab arm, and overall QOL was statistically significantly worse for patients randomized to treatment with ipilimumab, although the difference was not considered clinically relevant.27 In the KEYNOTE-054 trial for patients with stage III resected melanoma, pembrolizumab also provided improved RFS compared with placebo.9,28,29 A PRO analysis showed that pembrolizumab resulted in a statistically significant worsening in global QOL; however, it was not considered clinically relevant.30 For both trials, improved efficacy of the immune checkpoint inhibitor experimental arm compared with placebo without clinically meaningful detriment in QOL assessment supported widespread adoption of immune checkpoint inhibitor adjuvant therapy in melanoma. The CheckMate 238 trial, conducted in patients with resected American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th edition stage IIIB, IIIC, or IV melanoma, compared anti-PD-1 adjuvant therapy with anti–cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 adjuvant therapy. Recurrence-free survival was superior with nivolumab compared with ipilimumab, and nivolumab was less toxic, with 14% of patients in the nivolumab arm experiencing grade 3 or 4 adverse events compared with 46% in the ipilimumab group.6 But despite improved clinical outcomes and fewer toxic effects, the study reported that patients in the nivolumab group had QOL responses that were not meaningfully different from those in the ipilimumab group.

Limitations

In SWOG S1404, pembrolizumab provided superior RFS compared with the control, as previously reported,7 and has now been demonstrated to result in better QOL. One concern is that this finding could be an artifact of the inclusion of HDI in the control group, since HDI has a known acute toxic effect profile that is burdensome to patients, with attendant reductions in QOL.1,2,31,32 Yet in additional analyses, we found that pembrolizumab provided superior QOL outcomes compared with the subset of control arm patients receiving ipilimumab, including differences exceeding the prespecified target difference of 5.0 points. This finding is limited by the fact that the comparison represents a subset analysis that was not fully powered within the design. Nonetheless, it suggests that the finding of superior QOL for pembrolizumab was not simply an artifact of a control arm that allowed HDI as a treatment option.

This study was also limited by the requirement that PRO instruments be collected only up to progression. This strategy is allowed within international standards and is used when the intention is to more closely reflect the patient experience while receiving protocol therapy.16,33,34,35 However, it can also introduce a dependency between assessment of QOL and the patient’s clinical course based on missing data, because PRO assessments were no longer required after therapy was discontinued. In part for this reason, more patients in the ipilimumab/HDI arm did not complete QOL assessments, resulting in the potential for noncompatibility of the 2 treatment arms. Importantly, the findings were robust to patterns of missing data using pattern mixture models. Additionally, although comparisons between pembrolizumab vs ipilimumab and pembrolizumab vs HDI, separately, were provided to aid interpretation, the interpretation of these post hoc results is limited because the study was not designed or powered for these analyses.

Conclusions

Patients with cancer, in consultation with their physicians, are routinely challenged to balance the benefits of a given treatment with the potential adverse consequences to QOL. Taken together with the primary clinical results, this secondary analysis of the SWOG S1404 phase 3 randomized clinical trial demonstrated that pembrolizumab conveyed superior clinical and patient-reported QOL outcomes compared with standard treatment for high-risk melanoma. Physicians should be encouraged to incorporate and discuss treatment-related QOL issues with patients when making shared decisions regarding the risks and benefits of adjuvant therapy in resected melanoma.

Trial protocol

eTable 1. Observed and fitted group mean results for the FACT-BRM scales

eTable 2. Determination of best model fit for longitudinal data analyses

eTable 3. Best model results for longitudinal analyses using linear mixed models

eTable 4. Observed and fitted group mean results for the FACT-G scales

eTable 5. Observed and fitted group mean results for FACIT-D scales

eTable 6. Observed and fitted group mean results for the EQ-5D-3L Index score

eMethods. Pattern mixture model analysis

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Kilbridge KL, Weeks JC, Sober AJ, et al. Patient preferences for adjuvant interferon alfa-2b treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(3):812-823. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mocellin S, Lens MB, Pasquali S, Pilati P, Chiarion Sileni V. Interferon alpha for the adjuvant treatment of cutaneous melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD008955. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008955.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirkwood JM, Strawderman MH, Ernstoff MS, Smith TJ, Borden EC, Blum RH. Interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy of high-risk resected cutaneous melanoma: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial EST 1684. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(1):7-17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ, et al. Adjuvant ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of high-risk stage III melanoma (EORTC 18071): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(5):522-530. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70122-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ascierto PA, Del Vecchio M, Mandalá M, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage IIIB-C and stage IV melanoma (CheckMate 238): 4-year results from a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(11):1465-1477. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30494-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, et al. ; CheckMate 238 Collaborators . Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(19):1824-1835. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossmann KF, Othus M, Patel SP, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus IFNa2b or ipilimumab in resected high-risk melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(3):644-653. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. ; KEYNOTE-006 investigators . Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2521-2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(19):1789-1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang PF, Chen Y, Song SY, et al. Immune-related adverse events associated with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 treatment for malignancies: a meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:730. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, Basch E. Patient-reported outcomes and the evolution of adverse event reporting in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(32):5121-5127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fromme EK, Eilers KM, Mori M, Hsieh YC, Beer TM. How accurate is clinician reporting of chemotherapy adverse effects? a comparison with patient-reported symptoms from the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire C30. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(17):3485-3490. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calvert MJ, Freemantle N. Use of health-related quality of life in prescribing research: part 1: why evaluate health-related quality of life? J Clin Pharm Ther. 2003;28(6):513-521. doi: 10.1046/j.0269-4727.2003.00521.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6199-6206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG, Revicki DA, Moher D, Brundage MD; CONSORT PRO Group . Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA. 2013;309(8):814-822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coens C, Pe M, Dueck AC, et al. ; Setting International Standards in Analyzing Patient-Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life Endpoints Data Consortium . International standards for the analysis of quality-of-life and patient-reported outcome endpoints in cancer randomised controlled trials: recommendations of the SISAQOL Consortium. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(2):e83-e96. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30790-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacik J, Mazumdar M, Murphy BA, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy-BRM (FACT-BRM): a new tool for the assessment of quality of life in patients treated with biologic response modifiers. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(1):137-154. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000015297.91158.01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.FACIT Group . Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—diarrhea. Accessed March 30, 2021. https://www.facit.org/measures/FACIT-D

- 19.Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, et al. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(7):1717-1727. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0322-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care. 2005;43(3):203-220. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.EuroQol . EQ-5D-3L: about. Accessed March 30, 2021. https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-3l-about/

- 22.Trask PC, Paterson AG, Esper P, Pau J, Redman B. Longitudinal course of depression, fatigue, and quality of life in patients with high risk melanoma receiving adjuvant interferon. Psychooncology. 2004;13(8):526-536. doi: 10.1002/pon.770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yost KJ, Sorensen MV, Hahn EA, Glendenning GA, Gnanasakthy A, Cella D. Using multiple anchor- and distribution-based estimates to evaluate clinically meaningful change on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Biologic Response Modifiers (FACT-BRM) instrument. Value Health. 2005;8(2):117-127. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.08202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little RJA. A class of pattern-mixture models for normal incomplete data. Biometrika. 1994;81:471-483. doi: 10.1093/biomet/81.3.471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fairclough DL. Design and Analysis of Quality of Life Studies in Clinical Trials. 2nd ed. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Taylor & Francis Group, LLC; 2010. doi: 10.1201/9781420061185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pauler DK, McCoy S, Moinpour C. Pattern mixture models for longitudinal quality of life studies in advanced stage disease. Stat Med. 2003;22(5):795-809. doi: 10.1002/sim.1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coens C, Suciu S, Chiarion-Sileni V, et al. Health-related quality of life with adjuvant ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of high-risk stage III melanoma (EORTC 18071): secondary outcomes of a multinational, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(3):393-403. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30015-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandalà M, et al. ; EORTC Melanoma Group . Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma (EORTC 1325-MG/KEYNOTE-054): distant metastasis-free survival results from a double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):643-654. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00065-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, et al. Longer follow-up confirms recurrence-free survival benefit of adjuvant pembrolizumab in high-risk stage III melanoma: updated results from the EORTC 1325-MG/KEYNOTE-054 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(33):3925-3936. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bottomley A, Coens C, Mierzynska J, et al. ; EORTC Melanoma Group . Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma (EORTC 1325-MG/KEYNOTE-054): health-related quality-of-life results from a double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):655-664. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00081-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tarhini AA, Lee SJ, Hodi FS, et al. Phase III study of adjuvant ipilimumab (3 or 10 mg/kg) versus high-dose interferon alpha-2b for resected high-risk melanoma: North American Intergroup E1609. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(6):567-575. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarhini AA, Zheng Y, Lee SJ, et al. Patient-reported outcomes among patients with resected high-risk melanoma (AJCC7 IIIB, IIIC, M1a, M1b) randomized to low- or high-dose adjuvant ipilimumab (ipi) versus high-dose interferon alfa-2b (HDI): health-related quality of life (HRQL) analysis of ECOG-ACRIN E1609. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:e22078-e22078. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.e22078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cortés J, Baselga J, Im YH, et al. Health-related quality-of-life assessment in CLEOPATRA, a phase III study combining pertuzumab with trastuzumab and docetaxel in metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(10):2630-2635. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strosberg J, Wolin E, Chasen B, et al. ; NETTER-1 Study Group . Health-related quality of life in patients with progressive midgut neuroendocrine tumors treated with 177lu-dotatate in the phase III NETTER-1 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(25):2578-2584. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.5865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M, et al. Maintenance olaparib for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):317-327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

eTable 1. Observed and fitted group mean results for the FACT-BRM scales

eTable 2. Determination of best model fit for longitudinal data analyses

eTable 3. Best model results for longitudinal analyses using linear mixed models

eTable 4. Observed and fitted group mean results for the FACT-G scales

eTable 5. Observed and fitted group mean results for FACIT-D scales

eTable 6. Observed and fitted group mean results for the EQ-5D-3L Index score

eMethods. Pattern mixture model analysis

Data sharing statement