Abstract

Salmonella typhi, the etiologic agent of typhoid fever, is adapted to the human host and unable to infect nonprimate species. The genetic basis for host specificity in S. typhi is unknown. The avirulence of S. typhi in animal hosts may result from a lack of genes present in the broad-host-range pathogen Salmonella typhimurium. Genomic subtractive hybridization was successfully employed to isolate S. typhimurium genomic sequences which are absent from the S. typhi genome. These genomic subtracted sequences mapped to 17 regions distributed throughout the S. typhimurium chromosome. A positive cDNA selection method was then used to identify subtracted sequences which were transcribed by S. typhimurium following macrophage phagocytosis. A novel putative transcriptional regulator of the LysR family was identified as transcribed by intramacrophage S. typhimurium. This putative transcriptional regulator was absent from the genomes of the human-adapted serovars S. typhi and Salmonella paratyphi A. Mutations within this gene did not alter the level of S. typhimurium survival within macrophages or virulence within mice. A subtracted genomic fragment derived from the ferrichrome operon also hybridized to the intramacrophage cDNA. Nucleotide sequence analysis of S. typhimurium and S. typhi chromosomal sequences flanking the ferrichrome operon identified a novel S. typhimurium fimbrial operon with a high level of similarity to sequences encoding Proteus mirabilis mannose-resistant fimbriae. The novel fimbrial operon was absent from the S. typhi genome. The absence of specific genes may have allowed S. typhi to evolve as a highly invasive, systemic human pathogen.

Bacteria classified as Salmonella enterica are capable of infecting a variety of hosts, resulting in diseases ranging from self-limiting gastroenteritis to life-threatening systemic infections. The extent and nature of the disease produced is the direct result of complex interactions between the infecting S. enterica serovar and the host species. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. typhimurium) causes disease in both mice and humans, yet the nature of the infection is distinctly different in each host. S. typhimurium is a frequent cause of gastroenteritis in humans yet typically causes a lethal systemic infection in genetically susceptible mice. The capacity to cause a range of diseases within a variety of host species is the hallmark of broad-host-range S. enterica serovars. Other S. enterica serovars are adapted to a specific host; these include S. enterica serovar Typhi (S. typhi), the etiologic agent of human typhoid fever. S. typhi is capable of causing a potentially fatal systemic infection in humans, but it is completely avirulent in nonprimate hosts. The natural resistance of most animals to S. typhi infection is such that a mouse is capable of surviving an oral dose of S. typhi which could lead to a fatal infection in a human. The innate resistance of mice to S. typhi infection and their susceptibility to S. typhimurium infection is correlated with the differential survival of these two serovars in murine macrophages. S. typhimurium 14028s survived phagocytosis by murine bone marrow-derived macrophages at a dramatically higher level than a clinical isolate of S. typhi (1). Unlike S. typhimurium, S. typhi was cleared from murine Peyer’s patches soon after M-cell entry (54), possibly through killing by Peyer’s patch-associated macrophages. Therefore, phagocytic cells may play an important role in determining host susceptibility to infection by various Salmonella serovars, and murine macrophages may serve as a model system to investigate host specificity. The absence of genes in S. typhi that are expressed by S. typhimurium following macrophage phagocytosis may contribute to the inability of S. typhi either to survive in murine macrophages or to cause systemic infections in mice.

The inability of S. typhi to survive within murine macrophages or to successfully infect mice can be hypothesized to result from either the presence of dominant avirulence genes or the absence of virulence genes which are necessary in a mouse but superfluous, or perhaps even deleterious, during infection of the human host. The presence of dominant avirulence genes in bacterial plant pathogens clearly plays an important role in determining host specificity (66). The presence of analogous dominant avirulence genes within S. typhi would allow for infection of mice following a mutation which inactivated these genes. However, S. typhi has never been observed to cause disease within mice regardless of the strain or the route of inoculation tested (20, 23, 50). Saturation mutagenesis of the S. typhi chromosome also failed to yield mutants capable of expressing virulence in mice (41). Additionally, 20 serial passages of S. typhi through intravenously inoculated mice failed to increase the virulence toward mice (21). Therefore, it seems more likely that virulence genes necessary for establishing infection within the mouse are absent from the S. typhi genome. Recently developed molecular genetic techniques have permitted the rapid isolation of DNA sequences unique to a species, serovar, or strain. One such technique, genomic subtractive hybridization, has been successfully employed to isolate sequences present within an avian pathogenic strain of Escherichia coli but absent from a nonpathogenic E. coli K-12 strain (16). Construction of mutants in which unique avian pathogenic chromosomal regions were replaced with corresponding DNA from E. coli K-12 revealed a role for some of these sequences in virulence (16). In order to identify S. typhimurium genes that are necessary for mouse virulence and that are absent from the S. typhi genome, genomic subtractive hybridization was employed, resulting in a large collection of S. typhimurium DNA sequences. The collected subtracted sequences were then used in a positive cDNA selection to identify sequences actively transcribed by S. typhimurium following macrophage phagocytosis. Screening of a set of cloned subtracted genomic sequences identified four clones as actively transcribed by intramacrophage S. typhimurium. This study focuses on the initial characterization of two genomic sequences, a novel putative transcriptional regulator and a previously undescribed fimbrial operon that was identified through its linkage to genes expressed by S. typhimurium following macrophage phagocytosis. Both of these novel genes are absent from the S. typhi genome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

Bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. typhimurium UK-1 (χ3761) and S. typhi Ty2 (χ3769) were the sources of genomic DNA used for subtractive hybridization. Bacteria were cultured in Lennox broth (46) at 37°C with aeration. Solid growth medium included 1.5% agar (Difco). Ampicillin (100 μg per ml) and chloramphenicol (25 μg per ml) were added to the medium as required.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| χ3761 | S. typhimurium UK-1 | 25 |

| χ3000 | S. typhimurium LT2 | 32 |

| χ3339 | S. typhimurium SL1344a | 32 |

| χ8019 | S. typhimurium 14028s | E. A. Groisman |

| χ8391 | S. typhimurium UK-1 stmR | This study |

| χ8392 | S. typhimurium SL1344 stmR | This study |

| χ3769 | S. typhi Ty2 | L. S. Baron |

| χ3744 | S. typhi ISP1820 | D. M. Hone |

| χ8207 | S. typhi ATCC 10749 | ATCCb |

| χ8209 | S. typhi ATCC 9993 | ATCC |

| χ8437 | S. sendai | 15c |

| χ8282 | S. paratyphi A | CDC 164-94d |

| χ8283 | S. paratyphi B | CDC 284-94 |

| χ8436 | S. paratyphi C | 15c |

| χ4761 | S. choleraesuis | 49 |

| χ3540 | S. gallinarum | NVSLe |

| χ4821 | S. dublin | C. Poppe |

| χ3763 | S. arizonaef | NVSL |

| χ6193 | E. coli, EAF+ | S. Mosely |

Mouse-passaged derivative of SL1344 obtained from B. A. D. Stocker.

American Type Culture Collection.

Obtained from A. J. Baumler.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

National Veterinary Science Laboratory, Ames, Iowa.

Chicken-passaged derivative of 88-3869.

General molecular techniques.

Plasmid DNAs were prepared by alkaline lysis as described previously (13). Lysate DNAs from the Mud-P22 set of S. typhimurium strains were prepared following mitomycin C induction, as described by Benson and Goldman (12). Radioactive probes were generated by random priming of template DNA in the presence of [α-32P]dCTP (4), except as noted otherwise. Southern blot hybridizations were performed following alkaline transfer of DNAs from agarose gels (57) to positively charged nylon membranes (GeneScreen Plus; NEN DuPont). Southern blot hybridizations were performed at 42°C in 50% formamide, 6× SSC (1× SSC contains 0.15 M NaCl and 0.015 M sodium citrate, pH 7.4), 0.3% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 100 μg of sheared, denatured calf thymus DNA (Sigma) per ml. PCR was performed with Amplitaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Cetus) in a 480 Thermal Cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus). Construction of the S. typhimurium χ3761 cosmid library was performed with chromosomal DNA that was purified on cesium chloride gradients (36) and then partially digested with Sau3A. Fragments in the range of 35 to 40 kbp were isolated from sucrose gradients (4) and ligated into the BamHI site of the low-copy-number cosmid vector pYA3174 (16). Ligated DNAs were packaged in vitro according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Stratagene) and transduced into E. coli S17-1 (64). Cosmid clones were stored individually to prevent the introduction of bias through unequal amplification. Cosmids capable of complementing E. coli strains carrying auxotrophic mutations in thr (at 0 min), pro (7 min), pur (51 min), phe (55 min), and ile (83 min) (65) were readily obtained, indicating that the library was likely complete due to the presence of sequences from around the chromosome. Nucleotide sequencing was performed with ABI Prism fluorescent Big Dye Terminators, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (PE Applied Biosystems); a 480 Thermal Cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus); and a combination of custom synthesized and pBluescript SK and KS oligonucleotide primers (Stratagene). Sequencing gels were run at the Protein and Nucleic Acid Chemistry Laboratory of Washington University. Some DNA templates were cloned into the vector pBC SK + (Stratagene) from size-selected chromosomal DNA restriction fragments.

Genomic subtractive hybridization.

Genomic subtractive hybridization between S. typhimurium and S. typhi was performed as described by Straus and Ausubel (67). Genomic DNAs were prepared from each strain by centrifugation through cesium chloride gradients, as described by Hull et al. (36). S. typhi DNA was sheared to an average size of 1 to 3 kbp by using a sonicator equipped with a microtip probe (W-380; Heat Systems-Ultrasonics) and then biotinylated with photoactivatible biotin, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Clontech). One microgram of S. typhimurium DNA that had been completely digested with Sau3A was mixed with 10 μg of biotinylated S. typhi DNA, denatured by boiling for 1 min, and then dried. Nucleic acids were resuspended in 4 μl of 2.5× EE buffer [1× EE buffer contains 10 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(3-propanesulfonic acid) and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0], mixed with 1.5 μl of 4 M NaCl, and allowed to anneal at 62°C for 18 h under a layer of mineral oil. The solution was then brought to a volume of 100 μl with EE buffer containing 500 mM NaCl and mixed with 100 μl (2 mg) of streptavidin-coated paramagnetic beads (Dynabeads M-280; Dynal), which had been washed and resuspended in EE buffer containing 1 M NaCl. Biotinylated S. typhi DNA and any annealing S. typhimurium DNA were removed from the solution with a magnet. The remaining unbound DNA was further enriched for DNA sequences unique to S. typhimurium through an additional four rounds of subtractive hybridization. Following the fifth round, unhybridized DNA fragments were ligated to Sau3A adaptors and PCR amplified with a primer complementary to one strand of the adapter. Radiolabeled probes were made from aliquots of the subtracted, amplified genomic sequences by primer extension. A second aliquot of the amplified sequences was cloned into the SmaI site of the vector pGEM4z (Promega) following treatment with T4 DNA polymerase to generate blunt ends.

Selective capture of transcribed sequences (SCOTS).

Cells of the murine macrophage-like cell line RAW264.7 (56) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Atlanta Biologicals) and 4 mM glutamine at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment. Cell cultures were passaged every 3 to 5 days for up to eight passages. Macrophages were seeded at approximately 5 × 105 cells per ml into 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks (Corning Costar). For macrophage infection, S. typhimurium χ3761 was inoculated into Lennox broth from a frozen stock, cultured overnight at 37°C with aeration, and then diluted 1:100 into fresh medium and cultured for 90 min. Bacteria were then collected by centrifugation and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to macrophage inoculation at a multiplicity of infection of 2.5. After a 2-h incubation, macrophages were washed once with prewarmed DMEM and incubated for an additional 2 h in DMEM containing 10% FCS and gentamicin (100 μg per ml) to eliminate extracellular bacteria. Infected macrophages were then washed once more with prewarmed DMEM and lysed with 10 ml of guanidinium isothiocyanate RNA extraction buffer (22). Lysates were transferred to centrifuge tubes and extracted with equilibrated phenol, and the RNA was precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated deionized water. RNA samples were then treated with RNase-free DNase I according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Boehringer Mannheim), extracted with phenol-chloroform, and ethanol precipitated. A 20-μg aliquot of RNA isolated from infected macrophages was converted to first-strand cDNA by using SuperscriptII (Gibco-BRL), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and a 35-nucleotide primer containing a random nonamer at its 3′ end (5′-GACACTCTCGAGACATCACCGGTACCNNNNNNNNN-3′). The random 3′ nonamer contained within the primer facilitated random priming of the first-strand cDNA. cDNA was made double stranded by random priming with Klenow DNA polymerase (Gibco-BRL), as described by Froussard (28), with the same 35-nucleotide primer that was used to prime the first-strand cDNA. Both cDNA strands were synthesized through random priming, and the indicated 26-nucleotide sequence 5′ to the random nonamer facilitated PCR amplification. For positive selection of cDNAs complementary to the subtracted genomic sequences, S. typhimurium PCR-amplified subtracted genomic sequences were biotinylated with photoactivatible biotin. A total of 4 μg of biotinylated subtracted genomic DNA was mixed with 10 μg of double-stranded cDNA, ethanol precipitated, resuspended in 15 μl of 2× EE buffer supplemented with 0.2 M NaCl, overlayed with mineral oil, and denatured at 94°C for 1.5 min. The nucleic acid mixture was then allowed to anneal at 69°C for 17 h. Biotinylated DNA, along with any hybridizing cDNAs, were removed from solution by binding to streptavidin-coated paramagnetic beads. Bound DNA was then washed twice with 2 mM NaCl and 0.1% SDS at 45°C for 20 min. Captured cDNA was then eluted with 0.5 M NaOH and 0.1 M NaCl at 25°C for 15 min. Eluted, captured cDNA was ethanol precipitated and amplified by PCR with a primer complementary to the 26-nucleotide sequence contained within the primer that was used to synthesize both cDNA strands.

Construction of S. typhimurium mutants.

To inactivate stmR, site-directed insertional mutations were created in S. typhimurium χ3761 and SL1344 (χ3339). A 130-bp HincII-EcoRI fragment from the genomic subtracted clone was cloned into the suicide vector pJP5603 (55). The resulting plasmid, pYA3468, was conjugated from E. coli S17-1 (λpir) into S. typhimurium χ3761 and χ3339, selecting for kanamycin resistance and growth on medium lacking proline. Insertion of the suicide vector into the chromosome through a single recombination event resulted in the disruption of the stmR open reading frame (ORF) through the generation of two mutated copies of stmR. Chromosomal insertions were confirmed through Southern blot hybridization (data not shown). Strains carrying mutated copies of stmR in S. typhimurium χ3761 and χ3339 genetic backgrounds were named χ8391 and χ8392, respectively.

Macrophage survival assays.

Primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophages were obtained from female CFW mice (Charles River Breeders), at 6 to 8 weeks old, according to the method of Buchmeier and Heffron (17). Mouse femurs and tibias were perfused with DMEM, followed by culture of adherent cells in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 5% horse serum, 10% conditioned medium from L929 cells, 2 mM glutamine, and 1% penicillin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment for 5 days. Prior to infection, macrophages were scraped from the tissue culture flask, resuspended in fresh medium lacking penicillin, and used to seed 24-well tissue culture plates at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells per well. Macrophages were inoculated the next day with wild-type and mutant S. typhimurium cells, which had been opsonized by 0.1% normal mouse serum in PBS, at a bacteria/macrophage ratio of 10:1. Tissue culture plates were centrifuged at 800 rpm for 5 min to synchronize phagocytosis. After a 20-min incubation, macrophages were washed twice with Hanks’ buffered salts solution and then incubated in tissue culture medium containing 10 μg of gentamicin per ml to kill extracellular bacteria. Surviving bacteria were enumerated as CFU on agar plates following macrophage lysis with 0.1% sodium deoxycholate.

Virulence in perorally inoculated mice.

For the peroral inoculation of mice, bacteria were cultured with aeration to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm, 0.4 to 0.6), pelleted, and resuspended in buffered saline gelatin (BSG). Seven-week-old female BALB/c mice (Harlan Sprague-Dawley) were removed from food and water for 4 h and then inoculated perorally with approximately 4 × 108 to 7 × 108 total CFU. Mice were returned to food and water at 30 min after inoculation. At 1, 3, and 6 days following inoculation, three mice per strain were euthanized and the small intestinal wall, Peyer’s patches, small intestinal contents, mesenteric lymph nodes, and spleen were removed and placed in 1 ml of BSG. Samples were homogenized, and bacterial titers were determined on MacConkey agar supplemented with lactose.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the S. typhi fhuB-hemL intergenic region and the S. typhimurium stmR gene have been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF134977 and AF134978, respectively.

RESULTS

Identification of S. typhimurium genomic sequences absent from the S. typhi genome.

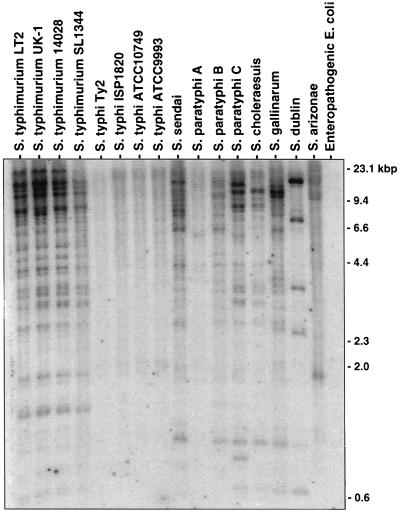

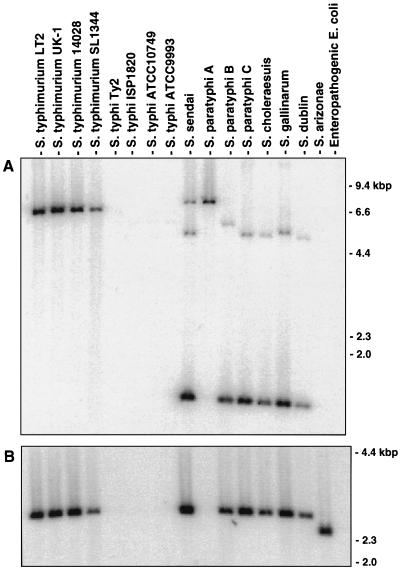

The inability of S. typhi to infect mice may be related to the absence of genes present in mouse-virulent strains of S. typhimurium, and the identification and characterization of these genes may lead to a better understanding of host adaptation by a pathogen. To identify S. typhimurium genomic sequences that are absent from S. typhi, a genomic subtractive hybridization was performed in which DNA fragments common to both genomes were selectively removed through five rounds of subtractive hybridization. Each round of subtractive hybridization progressively enriched for S. typhimurium sequences absent from the S. typhi genome. In order to verify the efficacy of the subtractive hybridization, Southern blot hybridizations of genomic DNAs from several Salmonella serovars and from an enteropathogenic strain of E. coli were performed with radiolabeled subtracted S. typhimurium sequences as probes. Hybridization to a minimum of 15 EcoRI bands, ranging in size from 1 to 23 kbp, from genomic DNAs of four wild-type strains of S. typhimurium was detected (Fig. 1). As expected, no hybridization to genomic DNA from four S. typhi strains was observed. No hybridization to a wild-type strain of S. enterica serovar Paratyphi A (S. paratyphi A), which is also adapted to humans, was observed. Hybridization to several EcoRI bands of DNA from strains of the human-adapted S. enterica serovars Sendai (S. sendai), Paratyphi B (S. paratyphi B), and Paratyphi C (S. paratyphi C) was observed, although fewer hybridizing bands were detected in these serovars than in S. typhimurium. The extent of hybridization of subtracted sequences to human-adapted serovar genomic DNA was observed as an increasing pattern of hybridization from S. typhi and S. paratyphi A to S. paratyphi B, S. sendai, and S. paratyphi C. Hybridization to DNA from S. enterica serovars Gallinarum (S. gallinarum), a host-restricted serovar causing fowl typhoid; Dublin (S. dublin), which is strongly adapted to cattle; and Choleraesuis (S. choleraesuis), which is adapted to swine, was also detected. A few hybridizing EcoRI bands were detected in DNA from S. enterica serovar Arizonae (S. arizonae), which is frequently associated with cold-blooded animals. No hybridization to DNA from a human enteropathogenic E. coli isolate was detected.

FIG. 1.

Presence of S. typhimurium subtracted genomic sequences in host-adapted Salmonella serovars and E. coli. Two micrograms of EcoRI-digested chromosomal DNA from each tested strain was hybridized with radiolabeled S. typhimurium genomic sequences that were subtracted of DNA sequences in common with S. typhi.

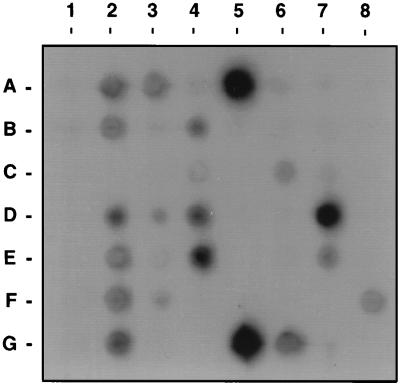

The distribution of subtracted sequences along the S. typhimurium chromosome was determined by hybridizing the radiolabeled subtracted sequences to Mud-P22 lysate DNAs from the ordered set of S. typhimurium mapping strains (12). S. typhimurium subtracted sequences hybridized to a total of 20 of 56 lysates which package DNA throughout the chromosome (Fig. 2). Therefore, sequences absent from S. typhi do not map to a single region or even to a few regions of the chromosome. Since lysates in opposing orientations may package overlapping regions of the chromosome, the 20 hybridizing lysates represent DNA from 17 sites distributed throughout the chromosome, including from min 0.0, 3.5, 7, 14, 17, 36, 40.5, 52, 54, 57, 62.7, 65, 72, 79.7, 86.7, 93, and 97. The strongest hybridization signals observed were to lysates which package DNA from min 7, 57, 97, and, to a lesser extent, 65, possibly indicating that most subtracted sequences were derived from these four chromosomal regions. If each hybridizing lysate contains a single contiguous chromosomal region which is absent from S. typhi, then a conservative estimate of 17 S. typhimurium chromosomal regions of undetermined size are absent from the S. typhi genome.

FIG. 2.

Mapping of S. typhimurium subtracted genomic sequences by hybridization to lysate DNAs from the Mud-P22 set of S. typhimurium strains. DNA from the 56 lysates was spotted in 8 rows, which follow in order from left to right and top to bottom (DNA from the first lysate is in row A, column 1).

The radiolabeled S. typhimurium subtracted sequences hybridized to a total of 104 of 422 cosmids screened from an unamplified S. typhimurium χ3761 genomic library. Nine of these cosmids hybridized with radiolabeled virulence plasmid DNA purified from S. typhimurium χ3761 (data not shown). The large virulence plasmid served as a positive control, since S. typhi does not carry the plasmid or chromosomal sequences homologous to the plasmid-encoded virulence genes (32, 58). The presence of virulence plasmid sequences in the radiolabeled probe mixture indicates that some observed hybridization to DNA from S. choleraesuis, S. dublin, and S. gallinarum may be attributed to virulence plasmid sequences carried by these serovars (58). Cosmids containing DNA inserts derived from the virulence plasmid were not analyzed further. Southern blot hybridization patterns of EcoRI-digested cosmid DNA probed with the subtracted sequences revealed that five pairs of cosmids had identical restriction patterns (data not shown). One cosmid from each of the five pairs was considered to be a duplicate and eliminated from further analysis. A total of 90 independent cosmids remained; they contained an average of 35 kbp of S. typhimurium genomic DNA, with all or a portion of each insert being absent from the S. typhi genome. Southern blot hybridization of EcoRI-digested cosmid DNAs probed with the subtracted sequences indicated that each cosmid contained numerous EcoRI fragments hybridizing with the S. typhimurium genomic subtracted DNA (data not shown). The genomic subtracted sequences mapped to 17 regions of the S. typhimurium chromosome, yet a total of 90 cosmids carrying subtracted sequences were isolated from a genomic library. This indicates that many of the cosmids must contain overlapping genomic DNA inserts derived from the same chromosomal region. Based upon the sizes of hybridizing EcoRI bands in Southern blots, many of the 90 cosmids could be divided into groups in which each cosmid contained one or more common bands. The presence of overlapping inserts in 90 cosmids which map to 17 chromosomal regions supports the conclusion that the screen was likely complete in isolating all unique regions of the S. typhimurium chromosome.

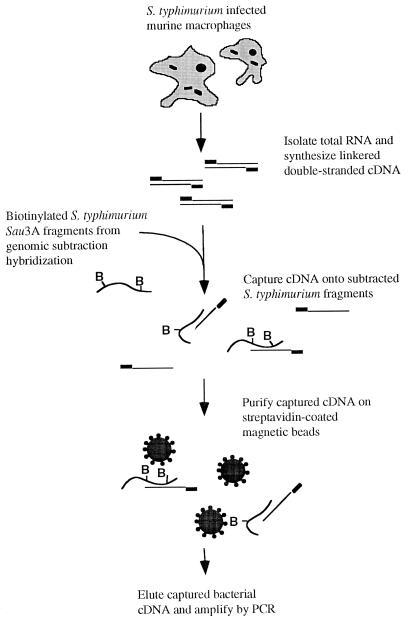

SCOTS.

Identification of coding regions within large segments of cloned genomic DNA can be readily accomplished through selective capture of cDNAs encoded by the genomic DNA of interest (53). A cDNA capture method developed to identify Mycobacterium tuberculosis genes induced within macrophages (30) was adapted to the large collection of S. typhimurium subtracted genomic DNA fragments to identify sequences that are expressed as RNA in an environment relevant to the role of Salmonella as an intracellular pathogen. The differential survival of S. typhi and S. typhimurium in murine macrophages (1) allows these cells to be used as a model system for studying host specificity. Selective capture of transcribed sequences that are complementary to S. typhimurium subtracted genomic sequences was performed as outlined in Fig. 3. Cells of the murine macrophage-like line RAW264.7 were inoculated with S. typhimurium χ3761 bacteria. Following phagocytosis and gentamicin treatment to eliminate extracellular bacteria, both macrophages and bacteria were lysed and total RNA was purified. Bacterial cDNAs complementary to the subtracted sequences were then selectively captured through hybridization to biotinylated S. typhimurium subtracted genomic sequences. cDNAs synthesized from RAW264.7 RNA or from bacterial transcripts of genes common to S. typhi and S. typhimurium were eliminated through stringent washing following the selective capture of cDNAs complementary to the S. typhimurium genomic subtracted sequences. The captured cDNAs were then eluted and amplified by PCR.

FIG. 3.

Schematic diagram of the SCOTS technique to identify subtracted genomic sequences which are transcribed by bacteria following macrophage phagocytosis.

SCOTS generated a population of cDNA molecules corresponding to genes present in S. typhimurium subtracted genomic sequences that were expressed as RNA in murine macrophages. Our next objective was to identify specific genes represented in this population of captured cDNA molecules. To do this we constructed a library of S. typhimurium subtracted genomic sequences. A subset of this library was then probed with radiolabeled captured cDNAs. A total of 4 of the 100 clones that were probed hybridized. The potential for unequal amplification of both the subtracted genomic sequences and the captured cDNAs through PCR (69) precludes an accurate extrapolation from these results to the number of S. typhimurium subtracted sequences which are expressed within murine macrophages. The nucleotide sequence of each hybridizing clone was determined and then compared with known sequences by using the BLAST computer program (3). Similarities between the predicted amino acid sequences of ORFs within each clone and previously sequenced genes allowed for tentative identification of three of the four clones. The putative identification of each clone is presented in Table 2. The clones were designated Stm-Sty, for “S. typhimurium genomic sequences minus common S. typhi genomic sequences.” Stm-Sty clone 3 did not exhibit significant similarity to any available sequence.

TABLE 2.

Similarities of S. typhimurium subtracted genomic clones hybridizing to captured intramacrophage cDNA based on nucleotide sequence comparisons with the nonredundant database

| Clone | Similarity | E valuea |

|---|---|---|

| Stm-Sty 1 | Y. pestis ORF 49b | 5e-19 |

| Stm-Sty 2 | E. coli R plasmid TraY | 8e-09 |

| Stm-Sty 3 | Unknown | NA |

| Stm-Sty 4 | E. coli FhuBc | 1e-05 |

The E value represents the number of sequence alignments with an equivalent or superior score which are expected to have been found purely by chance. NA, not applicable.

Y. pestis ORF 49 is from the nucleotide sequence of the 102-kbp unstable region (GenBank accession no. AL031866).

Similarity to FhuB is based on the 5′ 121 bp of the 454-bp insert in Stm-Sty 4. The remaining 333 bp do not exhibit similarity to any previously sequenced gene.

The genomic subtracted DNA insert from each hybridizing clone was gel purified, radiolabeled, and used to probe a Southern blot of S. typhimurium and S. typhi genomic DNA. DNA inserts from Stm-Sty clones 1, 2, and 3 hybridized to S. typhimurium but not to S. typhi DNA (data not shown). The remaining clone, Stm-Sty 4, hybridized to DNA from both serovars, although a restriction fragment polymorphism was present between strains of the two serovars (data not shown). Stm-Sty clones 2 and 3 were not analyzed further in the present study.

Identification of a novel fimbrial operon.

Nucleotide sequence analysis revealed that Stm-Sty 4 contained the final 121 bp of the fhuB coding sequence and 333 bp of downstream DNA. fhuB is the final gene in the ferrichrome operon, which encodes products necessary for ferric hydroxamate uptake and maps to min 4.9 of the S. typhimurium chromosome, adjacent to the convergently transcribed gene hemL (60). Hybridization of cDNA from intramacrophage S. typhimurium to fhuB is consistent with a previous report that used in vivo expression technology (IVET) to show that the ferrichrome operon is expressed within host tissues (35). A probe derived from the portion of Stm-Sty 4 containing fhuB hybridized to DNA from S. typhimurium and S. typhi in a Southern blot. However, a probe derived from DNA downstream of fhuB hybridized only to S. typhimurium DNA (data not shown). Genomic DNA derived from the chromosomal region containing fhuB and hemL was cloned from S. typhimurium and S. typhi restriction fragments hybridizing to the DNA insert from Stm-Sty 4. Nucleotide sequence analysis revealed that S. typhi ISP1820 (χ3744) contains a fhuB-hemL intergenic region of 90 bp, whereas the fhuB-hemL intergenic region in S. typhimurium χ3339 is 7,495 bp. A comparison of the convergently transcribed fhuB and hemL coding sequences from both serovars reveals a sequence divergence in the last two codons plus the stop codon of the fhuB coding sequence and in the final codon of the hemL coding sequence. The sequence alterations between the two serovars did not change the specified amino acids for the carboxy terminus of either FhuB or HemL. Southern blot hybridizations of cloned sequences probed with radiolabeled captured cDNA indicated that transcription of the S. typhimurium ferrichrome operon, but not of sequences present in the fhuB-hemL intergenic region, was detected by SCOTS in intramacrophage S. typhimurium (data not shown). Therefore, Stm-Sty 4 was likely identified by cDNA hybridization due to the presence of fhuB sequences.

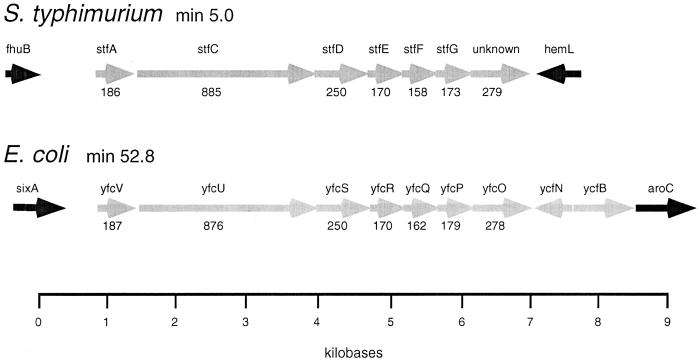

Nucleotide sequence analysis of the S. typhimurium fhuB-hemL intergenic region revealed the presence of seven ORFs organized as an operon. None of these ORFs were present in S. typhi, either in the intergenic region between fhuB and hemL or at another chromosomal location, as determined by Southern blot hybridizations. The genetic organization of these ORFs strongly resembles that of other enteric fimbrial operons. Six of these ORFs, stfACDEFG, exhibit significant protein level similarities to genes encoding mannose-resistant fimbriae from Proteus mirabilis and Serratia marcescens (Table 3) (6, 47). The first ORF encodes a predicted protein, StfA, which is very similar to the major structural subunits of P. mirabilis and S. marcescens mannose-resistant fimbrial adhesins. The second and third ORFs, stfC and stfD, are very similar to outer membrane fimbrial ushers and chaperones, respectively, of P. mirabilis MR/P fimbriae and E. coli Pap. The fourth, fifth, and sixth ORFs, stfE, stfF, and stfG, each encode predicted proteins with similarities to minor fimbrial subunits. The genes constituting this novel fimbrial operon did not exhibit similarity to any previously characterized E. coli fimbrial genes. Analysis of the complete E. coli K-12 genome (14), however, did identify ORFs which exhibit high levels of similarity to each gene within the S. typhimurium operon (Table 3). Within the E. coli K-12 genome, these ORFs map to a single region between aroC (min 52.7) and sixA (min 52.9) and are organized as an operon very similar in structure to that identified in S. typhimurium (Fig. 4). The E. coli K-12 ORF exhibiting similarity to fimbrial ushers, yfcU, is interrupted by a stop codon, potentially precluding functional expression of the encoded fimbrial genes. This reading frame is intact within S. typhimurium. The novel fimbrial operons in both S. typhimurium and E. coli are unusual in that they lack regulatory genes typically found to be proximal to the major fimbrial subunit genes of E. coli Pap and S fimbriae (5, 48) and potentially in the S. typhimurium virulence plasmid-encoded fimbria, pef (27). The penultimate ORF in the S. typhimurium operon exhibited a high degree of similarity to the E. coli S fimbrial adhesin. The final ORF in the operon exhibited similarity only to an E. coli ORF of unknown function, yfcO. The nucleotide sequence of the stf operon has a G+C content of 51.4% (Table 3), which is typical of the S. typhimurium chromosome (42). The nucleotide sequence of the entire S. typhimurium fimbrial operon was identical to a sequence recently submitted to GenBank, accession no. AF093503 (26), and the gene names presented here follow that scheme.

TABLE 3.

Similarities of the novel S. typhimurium fimbrial operon and StmR with sequences available in the nonredundant database

| Name | Size (aa) | % G+C | Similarity(s) | Identity/similarity (%) | E valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| StfA | 186 | 52.0 | E. coli hypothetical fimbrial protein YfcV | 40/54 | 1e-25 |

| S. marcescens major fimbrial protein SmfA | 37/54 | 1e-24 | |||

| P. mirabilis MR/P major fimbrial protein | 37/53 | 5e-17 | |||

| StfC | 885 | 54.9 | E. coli hypothetical outer membrane usher YfcU | 56/74 | 0.0 |

| P. mirabilis fimbrial usher MrpC | 48/65 | 0.0 | |||

| E. coli outer membrane usher PapC | 42/62 | 0.0 | |||

| StfD | 250 | 54.2 | E. coli hypothetical fimbrial chaperone YfcS | 62/76 | 4e-82 |

| P. mirabilis fimbrial chaperone MrpD | 53/71 | 4e-70 | |||

| E. coli fimbrial chaperone PapD | 43/63 | 3e-52 | |||

| StfE | 170 | 55.9 | E. coli hypothetical fimbrial protein YfcR | 44/66 | 2e-35 |

| P. mirabilis fimbrial protein MrpE | 36/56 | 6e-19 | |||

| S. marcescens fimbrial protein SmfE | 36/52 | 3e-15 | |||

| StfF | 158 | 48.4 | E. coli hypothetical fimbrial protein YfcQ | 48/66 | 5e-34 |

| S. marcescens fimbrial protein SmfE | 46/63 | 6e-29 | |||

| P. mirabilis fimbrial protein MrpF | 42/65 | 2e-28 | |||

| StfG | 173 | 55.5 | E. coli hypothetical fimbrial protein YfcP | 40/57 | 3e-28 |

| S. marcescens fimbrial protein SmfF | 36/55 | 3e-13 | |||

| E. coli S fimbrial adhesin major subunit SfaA | 31/49 | 3e-09 | |||

| ORF 7 | 279 | 49.5 | E. coli YfcO | 38/55 | 3e-49 |

| StmR | 292 | 52.5 | Y. pestis hypothetical transcriptional regulatorb | 78/86 | 1e-125 |

| Klebsiella terrigena BudR | 42/61 | 3e-57 | |||

| E. coli hypothetical transcriptional regulator YnfLc | 38/57 | 1e-48 |

FIG. 4.

Structural organization of ORFs comprising the S. typhimurium novel fimbrial operon, stf, and highly similar ORFs from E. coli K-12 yfc. The chromosomal location of each region is noted, and the genes flanking each set of ORFs are indicated. The name of each ORF is given above each arrow, and the size in amino acids of the product of each ORF is given below each arrow. The two intergenic regions are drawn to scale.

Identification of a novel transcriptional regulator.

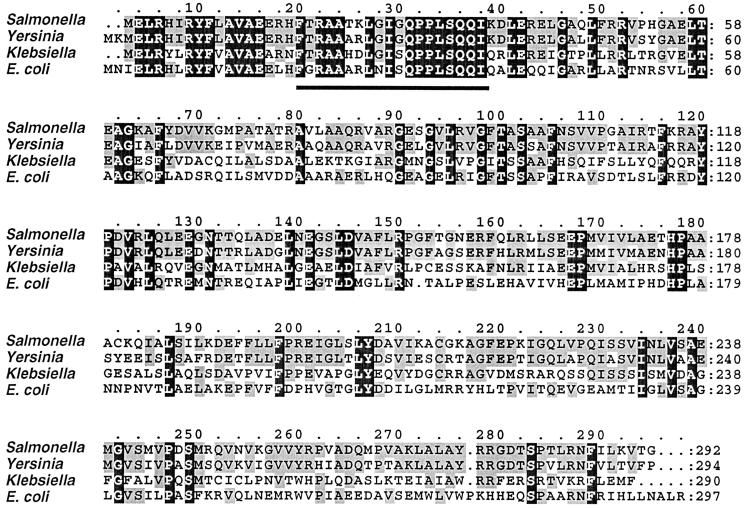

A comparison of the nucleotide sequence of Stm-Sty 1 with available sequences revealed a high degree of similarity to numerous transcriptional regulators of the LysR family (Table 3). A clone obtained from an S. typhimurium χ3761 genomic cosmid library that hybridized to the Stm-Sty 1 insert contained an ORF predicted to encode a protein of 292 amino acids, with a molecular mass of 31.9 kDa and a pI of 9.35. This predicted protein was designated StmR, for “Salmonella typhimurium regulator.” StmR was most similar to a hypothetical transcriptional regulator from the Yersinia pestis high-pathogenicity island (GenBank accession no. AL031866 [ORF 49] (19). A very high level of similarity to Klebsiella terrigena BudR, which regulates the transcription of genes necessary for butanediol synthesis (44), and to a hypothetical transcriptional regulator from E. coli, YnfL (14) (Table 3), was also observed. Alignment of the similar amino acid sequences revealed a high degree of conservation, especially between the S. typhimurium and Y. pestis ORFs, which exhibit similarity over their entire length (Fig. 5). The amino termini of the four sequences are particularly conserved and include helix-turn-helix motifs characteristic of LysR-like regulators (Fig. 5) (61). StmR does not exhibit significant similarity to previously characterized E. coli or S. typhimurium LysR family members, including SpvR, which regulates the S. typhimurium plasmid-encoded virulence genes and is also absent from the S. typhi genome. Southern blot hybridization of S. typhi chromosomal DNA using a probe consisting of the Stm-Sty 1 insert, which was derived entirely from the stmR ORF, did not indicate the presence of this sequence in S. typhi (see Fig. 6). Southern blots probed with stmR and flanking sequences derived from the corresponding S. typhimurium cosmid revealed the absence of at least 2.7 kbp of contiguous DNA from the S. typhi genome (data not shown). The stmR sequence has a G+C content of 52.5%, which is similar to the S. typhimurium chromosome as a whole. The nucleotide sequence of stmR matches S. typhimurium sequences derived from BlnI fragment A-A, which was sequenced as part of the genome sequencing project (Genome Sequencing Center, Washington University, St. Louis, Mo.). This places stmR within the chromosomal region of min 93.5 to 97.

FIG. 5.

Multiple alignment of the S. typhimurium StmR putative amino acid sequence with highly similar proteins of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Salmonella, S. typhimurium StmR; Yersinia, Y. pestis ORF 49 (GenBank accession no. AL031866); Klebsiella, K. terrigena BudR; E. coli, E. coli YnfL (GenBank accession no. AE000322). The bar below the amino acid alignment, residues 20 through 38, indicates the helix-turn-helix motif.

FIG. 6.

Distribution of stf and stmR among Salmonella serovars. (A) Southern blot hybridization of EcoRI-digested chromosomal DNAs probed with a 1.2-kbp S. typhimurium genomic fragment containing 526 bp of the stfA ORF and the fhuB-stfA intergenic region. (B) Southern blot hybridization of PstI-digested chromosomal DNAs probed with insert DNA from Stm-Sty 1, which is 382 bp in length and contains DNA upstream of stmR and 153 bp of the stmR ORF.

StmR is not required by S. typhimurium for survival within macrophages or for virulence in mice.

To evaluate the potential contribution of stmR to virulence, a site-directed insertional mutation was constructed within stmR in S. typhimurium χ3761 and χ3339. Mutants in both strain backgrounds grew well in laboratory media, indicating that this gene is not essential. Mutant strains along with their respective parental strains were tested for survival within primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophages in three separate experiments. In one representative experiment, the wild-type S. typhimurium strain χ3339 and the isogenic stmR mutant strain χ8392 exhibited 6.5 and 4.8% survival, respectively, at 4 h postinoculation and 2.8 and 2.5% survival, respectively, at 24 h postinoculation. Additionally, upon oral inoculation into BALB/c mice, the wild-type and stmR mutant strains were equally capable of establishing systemic infections. Mice orally inoculated with either χ3339 or χ8392 had bacterial titers of greater than 106 CFU per gram of spleen by the 6th day following inoculation. These data indicate that stmR and any genes potentially under its regulation are not necessary for S. typhimurium survival within murine macrophages or for the establishment of systemic infection in mice via the oral route of inoculation. Introduction of an episomal copy of stmR and at least 2 kbp of upstream and downstream flanking DNA into S. typhi χ3744 did not confer an increased level of survival upon this strain in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages.

Distribution of the novel fimbrial operon and stmR among Salmonella serovars.

The clones identified through cDNA capture were originally isolated as subtracted genomic S. typhimurium DNA fragments that were absent from the S. typhi genome. The phylogenetic distribution of the novel fimbrial operon and stmR was examined through Southern blot hybridization of chromosomal DNAs from various Salmonella serovars. The distribution of the fimbrial operon among Salmonella serovars was tested with chromosomal fragments containing stfA (Fig. 6A), stfC, or stfDEFG as probes (data not shown). The three stf probes generated identical results. The distribution of stmR was analyzed by using the insert of the genomic subtracted clone Stm-Sty 1 as a probe (Fig. 6B). The resulting blots (Fig. 6) clearly demonstrated the presence of both the fimbrial operon and stmR in four wild-type strains of S. typhimurium, as well as their absence from four strains of S. typhi. Distribution of the two loci differed with respect to the human-adapted serovar S. paratyphi A. The novel fimbrial operon, stf, was present in S. paratyphi A, but the stmR locus was absent from this serovar (Fig. 6). Both loci were present within the remaining tested human-adapted serovars, S. sendai, S. paratyphi B, and S. paratyphi C. Chromosomal DNAs from tested strains of S. choleraesuis, S. gallinarum, and S. dublin also hybridized with probes derived from both loci. Hybridization of the fimbrial operon to S. arizonae DNA was not detected, while hybridization to stmR was detected within this serovar. Neither probe hybridized to chromosomal DNA from a human enteropathogenic strain of E. coli.

DISCUSSION

Genomic subtractive hybridization successfully isolated a large collection of S. typhimurium genomic sequences that are absent from the S. typhi genome. Some of these DNA sequences were present in host-adapted Salmonella serovars, including the human-adapted serovars S. sendai, S. paratyphi A, S. paratyphi B, and S. paratyphi C, and the extent of hybridization to DNA from these serovars is inversely correlated with the severity of human infection typically caused by each human-adapted serovar. These results indicate that the absence of some subtracted sequences from the S. typhi genome may not be related to host adaptation in general or to human adaptation specifically. Additionally, differences in the numbers of sequences that different serovars share with S. typhimurium indicate that adaptation to the human host by these serovars has likely occurred independently. Genomic subtractive hybridization and genome sequencing have supplied abundant evidence that the chromosomes of closely related bacteria are significantly different (16, 45). The genetic differences between S. typhi and an avirulent strain of S. typhimurium were estimated by Lan and Reeves (39) to be in the range of 305 to 629 kbp, although such comparisons between Salmonella serovars are clearly strain dependent. The genomes of independent S. typhi isolates were found to vary by as much as 20%, or greater than 900 kbp (52). In addition to the absence of sequences, the S. typhi genome also contains sequences not found in most Salmonella serovars, including viaB, which is required for expression of the Vi capsular antigen (37), and an S. typhi-specific pathogenicity island (70). The large number of S. typhimurium genomic sequences absent from S. typhi complicates any analysis of individual sequences concerning their potential contribution to host adaptation.

The use of a selective cDNA capture technique to identify S. typhimurium sequences that were transcribed by intramacrophage bacteria effectively reduced the complexity of this set of subtracted sequences, facilitating the analysis of genomic differences. In light of the differential survival of S. typhimurium and S. typhi within murine macrophages (1), S. typhimurium genomic sequences that are transcribed within macrophages may play an important role in virulence in mice. We identified two such expressed sequences, fhuB, which was previously identified through IVET as being expressed in vivo (35), and a novel putative transcriptional regulator of the LysR family. Although fhuB is common to both S. typhimurium and S. typhi, analysis of the chromosomal regions adjacent to fhuB in both serovars led to the identification of a novel fimbrial operon in the S. typhimurium fhuB-hemL intergenic region that is absent from the corresponding S. typhi region. Nucleotide sequence divergence identified only within the final codons of the genes flanking the region absent in S. typhi may indicate that the fimbrial operon was deleted from S. typhi and that the flanking ORFs were subsequently restored. In addition to the short fhuB-hemL intergenic region, S. typhi also carries a similarly sized sequence at the chromosomal locus containing lpf in S. typhimurium (10), suggesting a common mechanism for loss of lpf and stf from S. typhi. The novel fimbrial operon exhibits a high protein level similarity to P. mirabilis and S. marcescens mannose-resistant hemagglutinating fimbriae, which contribute to pathogenesis (6). The presence of this fimbrial operon in all tested Salmonella serovars with the exceptions of S. typhi and S. arizonae argues that it has been deleted from the S. typhi chromosome rather than independently acquired by multiple serovars. The G+C nucleotide content of the operon is similar to the S. typhimurium chromosome as a whole, arguing against recent acquisition through horizontal transfer. Additionally, the presence of ORFs in E. coli that are very similar both in predicted protein sequence and in structural organization to the novel S. typhimurium fimbrial operon indicate considerable evolutionary conservation.

Along with the absence of stf, S. typhi also does not carry three of the five previously characterized S. typhimurium fimbrial operons, sef, pef, and lpf (7, 10), although S. typhi does carry genes encoding type 1 fimbriae and thin aggregative fimbriae (10). The loss of the virulence plasmid-encoded fimbrial operon, pef, as well as three chromosomally encoded fimbriae may reflect the evolutionary adaptation of S. typhi as a systemic human pathogen. The expression of different fimbrial adhesins, which are involved in tissue colonization as well as attachment to and entry into epithelial cells (2, 8, 9, 38), may contribute to host adaptation or to the nature of infection caused by the same bacterium within different hosts. Species specificity exhibited by Neisseria spp. is correlated with the binding of purified PilC to human epithelial cells but not to cells of nonhuman origin (59). S. typhi would therefore appear to be at a disadvantage in colonizing and infecting human hosts without the benefit of expressing four different fimbrial operons found together or in various combinations in other Salmonella serovars. However, the global incidence and severity of typhoid fever indicates that type 1 fimbriae, thin aggregative fimbriae, and nonfimbrial adhesins must be sufficient to allow S. typhi to colonize the human gastrointestinal tract and initiate systemic infection. Strains of S. typhi are highly invasive, and during establishment of a human systemic infection the expression of multiple fimbrial operons may be deleterious. In addition, the lack of specific fimbriae in S. typhi, or inappropriate fimbrial expression, may lead to an interaction within animal hosts that places S. typhi in the wrong niche, resulting in a more effective host response and subsequent resistance to S. typhi infection. Although the expression of certain fimbriae enhance bacterial colonization and contribute to pathogenesis in many bacterial species, fimbriae have also been demonstrated to enhance phagocytosis (51, 63), neutrophil activation (29, 68), and clearance of bacteria from sites of infection (40).

Selective capture of macrophage-expressed cDNAs identified a novel putative transcriptional regulator, stmR, with a high level of similarity to several members of the LysR family. The predicted amino acid sequence is nearly identical to that of a hypothetical transcriptional regulator within the pigmentation segment of the Y. pestis high-pathogenicity island, which is essential for expression of high levels of virulence (11, 18). Several other transcriptional regulators which influence S. typhimurium virulence in mice have been identified, including the LysR family member SpvR, which regulates expression of plasmid-encoded virulence genes (33). However, mutations in SinR, an S. typhimurium LysR member not found in other enterobacteria, did not detectably alter the level of virulence in mice (31). Transcription of stmR in macrophages is consistent with a potential role in activating the transcription of genes involved in survival within phagocytic cells, but mutations within stmR in two S. typhimurium strains did not reduce the level of survival in macrophages. Additionally, a mutation in stmR did not affect the ability of S. typhimurium to establish systemic infection in orally inoculated mice. Identification of the target genes regulated by StmR may indicate a function for this sequence and its potential contribution to host adaptation, in light of the fact that it has apparently been deleted from both S. typhi and S. paratyphi A.

Genomic subtraction demonstrated a significant degree of genetic divergence between S. typhi and S. typhimurium. The acquisition and deletion of genes by S. typhi may be associated with host adaptation, but a defined role for most of these sequences is not clear. Several S. typhimurium genes have been identified previously as being absent from the S. typhi genome, including the chromosomally encoded fimbrial genes sef and lpf and a gene with similarity to a Xanthomonas campestris avirulence gene, avrA (34). Isolation of in vivo-induced S. typhimurium sequences by IVET demonstrated that some sequences contributing to virulence are absent from the genomes of both S. typhi and S. choleraesuis (24). However, mutations within each of the genes that are absent from S. typhi had either a moderate effect or no effect upon S. typhimurium virulence, eliminating simplistic explanations for the avirulence of S. typhi in animal hosts. Multilocus enzyme electrophoretic (MLEE) analysis of the human-adapted Salmonella serovars did not reveal a close relationship between strains of S. typhi and the other serovars, S. sendai, S. paratyphi A, S. paratyphi B, and S. paratyphi C (62). With the exception of S. paratyphi A, this conclusion is supported here by the number of bands hybridizing to the S. typhimurium subtracted sequences, as well as to stmR and stf. MLEE analysis indicated a very close relationship between strains of S. sendai and S. paratyphi A (62). However, S. sendai has many subtracted sequences in common with S. typhimurium that S. paratyphi A does not, including stmR. MLEE data, in combination with the phylogenetic distribution of S. typhimurium subtracted DNA described here, indicate independent evolutionary paths for adaptation to the human host. Of the human-adapted Salmonella serovars, strains of S. typhi and S. paratyphi A tend to be the most virulent. The presence of the novel fimbrial operon, stf, in S. paratyphi A and its absence from S. typhi indicates that adaptation as a systemic human pathogen may have occurred through a convergent evolutionary mechanism involving deletion of specific genes. The evolutionary distance between S. typhi and S. paratyphi A is further supported by the distribution of viaB, which is present in S. typhi but absent from S. paratyphi A (62). The theory of increased virulence through the loss of genes, as opposed to the evolution of a pathogen through gene acquisition, has been proposed as the “black hole” model, exemplified by Shigella spp. (43). Within S. typhi, the absence of numerous genes that are present in the broad-host-range serovar S. typhimurium may have played a significant role in the emergence of S. typhi as a successful human-adapted pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI24533-10 and AI35267 from the National Institutes of Health. B.J.M. was supported by a National Research Service Award, AI09465.

We thank Andreas Baumler for providing S. sendai and S. paratyphi C strains, Mary Wilmes-Riesenberg and France Daigle for assistance with tissue culture, and Charles Dozois for critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alpuche-Aranda C M, Berthiaume E P, Mock B, Swanson J A, Miller S I. Spacious phagosome formation within mouse macrophages correlates with Salmonella serotype pathogenicity and host susceptibility. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4456–4462. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4456-4462.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altmeyer R M, McNern J K, Bossio J C, Rosenshine I, Finlay B B, Galan J E. Cloning and molecular characterization of a gene involved in Salmonella adherence and invasion of cultured epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:89–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baga M, Goransson M, Normark S, Uhlin B E. Transcriptional activation of a pap pilus virulence operon from uropathogenic Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1985;4:3887–3893. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahrani F K, Massad G, Lockatell C V, Johnson D E, Russell R G, Warren J W, Mobley H L. Construction of an MR/P fimbrial mutant of Proteus mirabilis: role in virulence in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3363–3371. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3363-3371.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumler A J, Heffron F. Identification and sequence analysis of lpfABCDE, a putative fimbrial operon of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2087–2097. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2087-2097.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumler A J, Tsolis R M, Heffron F. Contribution of fimbrial operons to attachment to and invasion of epithelial cell lines by Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1862–1865. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1862-1865.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumler A J, Tsolis R M, Bowe F A, Kusters J G, Hoffmann S, Heffron F. The pef fimbrial operon of Salmonella typhimurium mediates adhesion to murine small intestine and is necessary for fluid accumulation in the infant mouse. Infect Immun. 1996;64:61–68. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.61-68.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumler A J, Gilde A J, Tsolis R M, van der Velden A W, Ahmer B M, Heffron F. Contribution of horizontal gene transfer and deletion events to development of distinctive patterns of fimbrial operons during evolution of Salmonella serotypes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:317–322. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.317-322.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bearden S W, Fetherston J D, Perry R D. Genetic organization of the yersiniabactin biosynthetic region and construction of avirulent mutants in Yersinia pestis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1659–1668. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1659-1668.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benson N R, Goldman B S. Rapid mapping in Salmonella typhimurium with Mud-P22 prophages. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1673–1681. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1673-1681.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blattner F R, Plunkett G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyd E F, Wang F S, Beltran P, Plock S A, Nelson K, Selander R K. Salmonella reference collection B (SARB): strains of 37 serovars of subspecies I. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1125–1132. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-6-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown P K, Curtiss R., III Unique chromosomal regions associated with virulence of an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11149–11154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchmeier N A, Heffron F. Intracellular survival of wild-type Salmonella typhimurium and macrophage-sensitive mutants in diverse populations of macrophages. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.1-7.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchrieser C, Prentice M, Carniel E. The 102-kilobase unstable region of Yersinia pestis comprises a high-pathogenicity island linked to a pigmentation segment which undergoes internal rearrangement. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2321–2329. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2321-2329.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchrieser, C., C. Rusniok, E. Couve, L. Frangeul, A. Billault, F. Kunst, E. Carniel, and P. Glaser. Unpublished data. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Carter P B, Collins F M. The route of enteric infection in normal mice. J Exp Med. 1974;139:1189–1203. doi: 10.1084/jem.139.5.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter P B, Collins F M. Growth of typhoid and paratyphoid bacilli in intravenously infected mice. Infect Immun. 1974;10:816–822. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.4.816-822.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chomczynski P, Saachi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins F M, Carter P B. Growth of salmonellae in orally infected germfree mice. Infect Immun. 1978;21:41–47. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.1.41-47.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conner C P, Heithoff D M, Julio S M, Sinsheimer R L, Mahan M J. Differential patterns of acquired virulence genes distinguish Salmonella strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4641–4645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curtiss R, III, Porter S B, Munson M, Tinge S A, Hassan J O, Gentry-Weeks C, Kelly S M. Nonrecombinant and recombinant avirulent Salmonella live vaccines for poultry. In: Blankenship L C, editor. Colonization and control of human bacterial enteropathogens in poultry. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1991. pp. 169–198. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emmerth, M., W. Goebel, S. I. Miller, and C. J. Hueck. Unpublished data.

- 27.Friedrich M J, Kinsey N E, Vila J, Kadner R J. Nucleotide sequence of a 13.9 kb segment of the 90 kb virulence plasmid of Salmonella typhimurium: the presence of fimbrial biosynthetic genes. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:543–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Froussard P. A random-PCR method (rPCR) to construct whole cDNA library from low amounts of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:2900. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.11.2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goetz M B. Priming of polymorphonuclear neutrophilic leukocyte oxidative activity by type 1 pili from Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:533–542. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham, J. E., and J. Clark-Curtiss. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNAs synthesized in response to phagocytosis by human macrophages by selective capture of transcribed sequences (SCOTS). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Groisman E A, Sturmoski M A, Solomon F R, Lin R, Ochman H. Molecular, functional, and evolutionary analysis of sequences specific to Salmonella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1033–1037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gulig P A, Curtiss R., III Plasmid-associated virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2891–2901. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.2891-2901.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gulig P A, Danbara H, Guiney D G, Lax A J, Norel F, Rhen M. Molecular analysis of spv virulence genes of the Salmonella virulence plasmids. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:825–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hardt W D, Galan J E. A secreted Salmonella protein with homology to an avirulence determinant of plant pathogenic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9887–9892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heithoff D M, Conner C P, Hanna P C, Julio S M, Hentschel U, Mahan M J. Bacterial infection as assessed by in vivo gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:934–939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hull R A, Gill R E, Hsu P, Minshew B H, Falkow S. Construction and expression of recombinant plasmids encoding type 1 or d-mannose-resistant pili from a urinary tract infection Escherichia coli isolate. Infect Immun. 1981;33:933–938. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.3.933-938.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson E M, Krauskopf B, Baron L S. Genetic mapping of Vi and somatic antigenic determinants in Salmonella. J Bacteriol. 1965;90:302–308. doi: 10.1128/jb.90.2.302-308.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones G W, Richardson L A. The attachment to, and invasion of, HeLa cells by Salmonella typhimurium: the contribution of mannose-sensitive and mannose-resistant haemagglutinating activities. J Gen Microbiol. 1981;127:361–370. doi: 10.1099/00221287-127-2-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lan R, Reeves P R. Gene transfer is a major factor in bacterial evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 1996;13:47–55. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malaviya R, Ikeda T, Ross E, Abraham S N. Mast cell modulation of neutrophil influx and bacterial clearance at sites of infection through TNF-alpha. Nature. 1996;381:77–80. doi: 10.1038/381077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maloy S. Of mice and men: what limits genetic exchange between Salmonella typhimurium and Salmonella typhi. 1998. p. 2. . Midwest Microbial Pathogenesis Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marmur J, Doty P. Determination of the base composition of deoxyribonucleic acid from its thermal denaturation temperature. J Mol Biol. 1962;5:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(62)80066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maurelli A T, Fernandez R E, Bloch C A, Rode C K, Fasano A. “Black holes” and bacterial pathogenicity: a large genomic deletion that enhances the virulence of Shigella spp. and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3943–3948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mayer D, Schlensog V, Bock A. Identification of the transcriptional activator controlling the butanediol fermentation pathway in Klebsiella terrigena. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5261–5269. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.18.5261-5269.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McClelland M, Wilson R K. Comparison of sample sequences of the Salmonella typhi genome to the sequence of the complete Escherichia coli K-12 genome. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4305–4312. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4305-4312.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1992. p. 25.5. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mizunoe Y, Nakabeppu Y, Sekiguchi M, Kawabata S, Moriya T, Amako K. Cloning and sequence of the gene encoding the major structural component of mannose-resistant fimbriae of Serratia marcescens. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3567–3574. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3567-3574.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morschhauser J, Uhlin B E, Hacker J. Transcriptional analysis and regulation of the sfa determinant coding for S fimbriae of pathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;238:97–105. doi: 10.1007/BF00279536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nnalue N A, Newton S, Stocker B A. Lysogenization of Salmonella choleraesuis by phage 14 increases average length of O-antigen chains, serum resistance and intraperitoneal mouse virulence. Microb Pathog. 1990;8:393–402. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90026-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Brien A D. Innate resistance of mice to Salmonella typhi infection. Infect Immun. 1982;38:948–952. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.3.948-952.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ofek I, Goldhar J, Keisari Y, Sharon N. Nonopsonic phagocytosis of microorganisms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:239–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.001323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pang T. Genetic dynamics of Salmonella typhi—diversity in clonality. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:339–342. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01341-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parimoo S, Patanali S R, Shukla H, Chaplin D D, Weissman S M. cDNA selection: efficient PCR approach for the selection of cDNAs encoded in large chromosomal DNA fragments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9623–9627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pascopella L, Raupach B, Ghori N, Monack D, Falkow S, Small P L. Host restriction phenotypes of Salmonella typhi and Salmonella gallinarum. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4329–4335. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4329-4335.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Penfold R J, Pemberton J M. An improved suicide vector for construction of chromosomal insertion mutations in bacteria. Gene. 1992;118:145–146. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90263-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ralph P, Nakoinz I. Antibody-dependent killing of erythrocyte and tumor targets by macrophage-related cell lines: enhancement by PPD and LPS. J Immunol. 1977;119:950–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reed K C, Mann D A. Rapid transfer of DNA from agarose gels to nylon membranes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:7207–7221. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.20.7207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roudier C, Krause M, Fierer J, Guiney D G. Correlation between the presence of sequences homologous to the vir region of Salmonella dublin plasmid pSDL2 and the virulence of twenty-two Salmonella serotypes in mice. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1180–1185. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1180-1185.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rudel T, Scheurerpflug I, Meyer T F. Neisseria PilC protein identified as type-4 pilus tip-located adhesin. Nature. 1995;373:357–359. doi: 10.1038/373357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sanderson K E, Hessel A, Rudd K E. Genetic map of Salmonella typhimurium, edition VIII. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:241–303. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.2.241-303.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schell M A. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:597–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Selander R K, Beltran P, Smith N H, Helmuth R, Rubin F A, Kopecko D J, Ferris K, Tall B D, Cravioto A, Musser J M. Evolutionary genetic relationships of clones of Salmonella serovars that cause human typhoid and other enteric fevers. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2262–2275. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2262-2275.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silverblatt F J, Dreyer J S, Schauer S. Effect of pili on susceptibility of Escherichia coli to phagocytosis. Infect Immun. 1979;24:218–223. doi: 10.1128/iai.24.1.218-223.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Singer M, Baker T A, Schnitzler G, Deischel S M, Goel M, Dove W, Jaacks K J, Grossman A D, Erickson J W, Gross C A. A collection of strains containing genetically linked alternating antibiotic resistance elements for genetic mapping of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:1–24. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.1-24.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Staskawicz B J, Dahlbeck D, Keen N T. Cloned avirulence gene of Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea determines race-specific incompatibility on Glycine max. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6024–6028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.19.6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Straus D, Ausubel F M. Genomic subtraction for cloning DNA corresponding to deletion mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1889–1893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tewari R, MacGregor J I, Ikeda T, Little J R, Hultgren S J, Abraham S N. Neutrophil activation by nascent FimH subunits of type 1 fimbriae purified from the periplasm of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3009–3015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wieland I, Bolger G, Asouline G, Wigler M. A method for difference cloning: gene amplification following subtractive hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2720–2724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang X L, Morris C, Hackett J. Molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence, and function of a site-specific recombinase encoded in the major ‘pathogenicity island’ of Salmonella typhi. Gene. 1997;202:139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00466-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]