Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been garnered increasing for its rapid worldwide spread. Each country had implemented city-wide lockdowns and immigration regulations to prevent the spread of the infection, resulting in severe economic consequences. Materials and technologies that monitor environmental conditions and wirelessly communicate such information to people are thus gaining considerable attention as a countermeasure. This study investigated the dynamic characteristics of batteryless magnetostrictive alloys for energy harvesting to detect human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E). Light and thin magnetostrictive Fe–Co/Ni clad plate with rectification, direct current (DC) voltage storage capacitor, and wireless information transmission circuits were developed for this purpose. The power consumption was reduced by improving the energy storage circuit, and the magnetostrictive clad plate under bending vibration stored a DC voltage of 1.9 V and wirelessly transmitted a signal to a personal computer once every 5 min and 10 s under bias magnetic fields of 0 and 10 mT, respectively. Then, on the clad plate surface, a novel CD13 biorecognition layer was immobilized using a self-assembled monolayer of –COOH groups, thus forming an amide bond with –NH2 groups for the detection of HCoV-229E. A bending vibration test demonstrated the resonance frequency changes because of HCoV-229E binding. The fluorescence signal demonstrated that HCoV-229E could be successfully detected. Thus, because HCoV-229E changed the dynamic characteristics of this plate, the CD13-modified magnetostrictive clad plate could detect HCoV-229E from the interval of wireless communication time. Therefore, a monitoring system that transmits/detects the presence of human coronavirus without batteries will be realized soon.

Abbreviations: AC, alternating current; APS, aminopropyl silane; BSA, bovine serum albumin; CTF, corrected total fluorescence; DC, direct current; EDC, 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide; HCoV, human coronavirus; IC, integrated circuit; IoT, Internet of things; MES, 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid; MUA, mercaptoundecanoic acid; NHS, N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; RC, rectifier circuit; SAM, self-assembled monolayer; SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

Keywords: Virrari effect, Fluorescence microscopy, CD13, Energy harvesting, Wireless communications, Virus detection

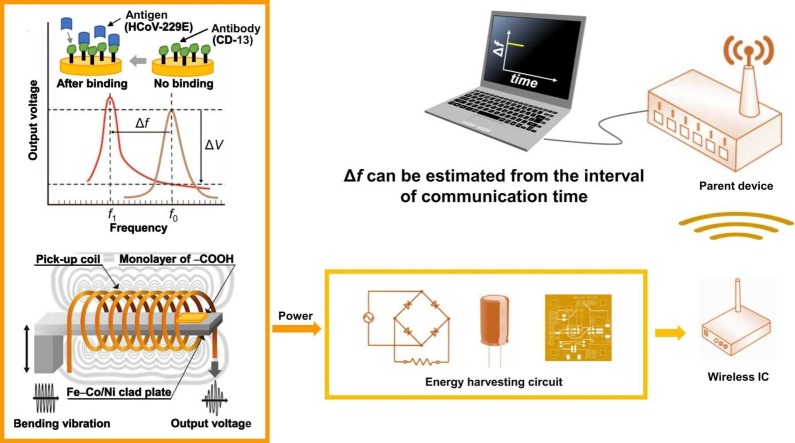

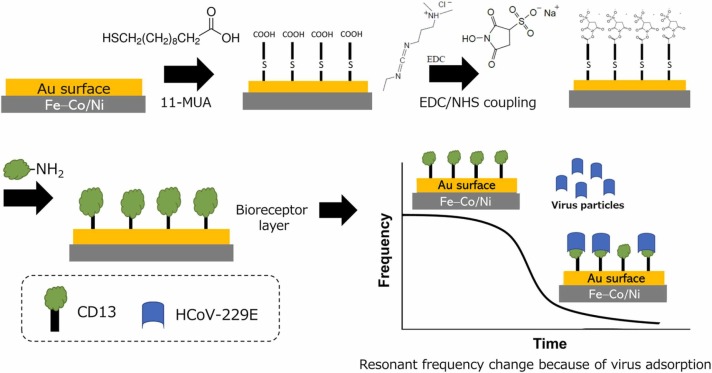

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

COVID-19, a new coronavirus that emerged in December 2019, caused cluster infections in hospitals, nursing homes, live-in homes, restaurants, and other establishments, halting social and economic activities. Furthermore, the virus continues to replicate mutations and increase its infectivity. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the ideal way of a with-corona/post-corona society based on the spread of infectious diseases and to rapidly develop technology that can respond to a sudden outbreak of a new acute respiratory tract infection [1]. Building an environment that allows for safe and secure social and economic activities is important. Therefore, many studies on COVID-19 have been conducted and discussed in detail [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. Several studies have been conducted on developing devices for analytical health monitoring and proof-of-concept diagnostics [7], [8], [9], [10].

Early detection of COVID-19 is critical because of its rapid transmission [11]. This has shifted the attention to alternative biosensing devices that can successfully detect COVID-19 infection and curb the spread of coronavirus cases [12]. Recently, some methods for detecting SARS-CoV-2 using a field-effect transistor-based [13], [14], nucleic acid-based [15], electrochemical conducting polymer-based [16], and loop-mediated isothermal amplification-based [17] new biosensors have been reported. The role of engineered surface chemistry in personal protective equipment in preventing the spread of SARS-CoV-2 has been highlighted [18], [19].

However, developing a technology to prevent infection by transmitting information to people as soon as the new coronavirus is detected is required. Therefore, integrating biosensors and IoT technologies is important. Power supply will be an issue deploying such IoT biosensors globally [20]. For this purpose, a piezoelectric or magnetostrictive material is used for biosensors [21]. This is because these materials have been extensively studied for more than a decade [22], [23] and are useful for energy harvesting [24] and recovery of electric power from unused energy (vibration, heat, light, and radio waves) in the natural environment. The development of piezoelectric composites has recently attracted attention [25], [26] to compensate for the limitations of piezoelectric ceramic materials, which can easily result in fracture under static [27] and cyclic [28] mechanical loading. Several studies and review articles on various piezoelectric energy harvesting materials and devices have been published [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]. Highly flexible magnetostrictive composites for wireless vibration energy harvesting have been developed [36], [37], and numerous studies on magnetostrictive energy harvesting materials and devices have been conducted [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43].

Unlike the abovementioned new biosensors [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], piezoelectric [44], [45] and magnetostrictive [46], [47], [48] sensors can be linked with IoT technologies and are batteryless; however, research on batteryless detection of viruses using these materials is currently unexamined. Even if this pandemic is over, new infectious diseases may emerge in the future; therefore, it is important to make the best use of piezoelectric and magnetostrictive materials that are easy to integrate with IoT devices, allowing for developing self-powered energy harvesting systems and biosensors for virus detection [21], [49], [50].

It is rational to continue research on virus detection using magnetostrictive materials because magnetostrictive biosensors have numerous advantages [21], [50], [51]. However, selecting a suitable biorecognition layer to adsorb viruses and adhere them to the surface of magnetostrictive materials is critical. Furthermore, it is desirable to conduct research with viruses that are easy to handle before focusing on SARS-CoV-2 because such research is challenging.

SARS-CoV-2, the COVID-19 causative virus, and the cold causative viruses HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, and HCoV-229E are among the HCoV that infect humans. Similar to influenza, the HCoV epidemic peaks in the winter; however, the outbreaks of HCoV-229E can occur in spring and autumn [52]. HCoV-229E exacerbates chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchial asthma; therefore, studies on this virus are still ongoing [53], [54], [55], [56]. However, no research has been conducted to detect HCoV-229E because there was previously no requirement to detect HCoV-229E.

This study identified a suitable magnetostrictive alloy that can be used in a batteryless, wireless device to detect HCoV-229E. For this purpose, Fe–Co/Ni clad plates and a power storage/information transmission circuit was developed and integrated. The characterization of magnetostrictive Fe–Co/Ni clad plates with vibration energy harvesting, wireless communication, and HCoV-229E sensing capabilities are presented. Bending vibration energy harvesting and voltage storage experiments were conducted, and the amount of stored voltage was measured. Then, a novel biorecognition layer was presented for HCoV-229E, and the receptor CD13 was chosen. A self-assembled monolayer of active carboxylic acid (–COOH) groups, forming an amide bond with –NH2 groups on CD13, was used on the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate. The feasibility of HCoV-229E sensing using a CD13-modified Fe–Co/Ni clad plate under bending vibration was discussed. Here, attempts were made to detect HCoV-229E, but when detecting SARS-CoV-2 or influenza, the biorecognition layer on the surface of the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate must be replaced.

2. Experimental procedure

2.1. Sensor materials

A Fe30Co70 plate with a thickness of 0.1 mm and a Ni plate with a thickness of 0.1 mm were diffusion-bonded to form a clad plate [57]. The average values of the initial (maximum) relative permeability of the Fe30Co70 and Ni plates are ∼150 (2500) and ∼400 (2600), respectively. The energy harvesting ability of the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate is far greater than that of the single Fe–Co plate, attributed to the enhancement in the magnetic induction variation between Fe–Co with positive magnetostrictive properties and Ni with negative magnetostrictive properties in response to bending vibration. The Fe–Co/Ni clad plate with a thickness of 0.2 mm was cut into a specified shape ( Fig. 1(a)).

Fig. 1.

(a) Image of a Fe–Co/Ni clad plate; (b) Circuit for energy storage and management; and (c) Schematic of the self-powered wireless communication test setup.

2.2. Self-powered wireless communication

In this study, we developed a circuit that stores vibration energy and transmits data at an indefinite frequency and incorporated it into a system. The power storage circuit regulated the power on and off of the wireless device handset unit (TWE-L-WX, MONO-WIRELESS.COM, Japan) because the energy generated by vibration was not large. The storage circuit turned on the power of the wireless device and transmitted data only when a certain amount of energy was stored in the storage capacitor. Except when transmitting data, the circuit turned off the wireless device to reduce power consumption and focus on energy storage.

Fig. 1(b) shows the entire circuit and the unit picture. The AC of the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate under bending vibration was rectified to DC using the full-wave RC. DC was stored in a storage capacitor (electric field capacitor). The storage circuit [58] detected that the storage capacitor voltage increased and the higher DC voltage source V H = 1.9 V was exceeded. The storage capacitor was connected to the DC-DC converter, and the DC-DC converter produced a constant power supply voltage (2.6 V). The power supply voltage entered the wireless device slave unit, and an internal program caused the wireless device to emit 2.4-GHz radio waves. At this time, the storage circuit detected that the voltage of the storage capacitor had dropped below the lower DC voltage source V L = 0.5 V. The storage capacitor was disconnected from the DC-DC converter, and energy storage started again.

Fig. 1(c) shows a schematic of the energy storage and wireless communication system test setup. The fabricated Fe–Co/Ni clad plate with a thickness of 0.2 mm and a width of 5 mm was mounted on a vibration shaker (ET-132, Labworks Inc., USA). The resonance frequency of this clad plate was 116 Hz [57]. A pick-up coil with 28,000 turns and a resistance of 11.7 kΩ were used. A circuit was developed in which a signal was transmitted at a DC voltage of 1.9 V, and connected to the clad plate with a 1000-μF Al electrolytic capacitor. AC voltage generated by bending vibration on the Fe-Co/Ni clad plate was converted to DC voltage and stored in the capacitor using the RC. At this point, a voltmeter was used to measure the stored DC voltage, and the transmitted data and time were recorded on a personal computer.

Experiments were conducted when the bias magnetic field was 0 and 10 mT. The bias magnetic field was loaded with a neodymium (Nd) magnet.

2.3. Virus detection

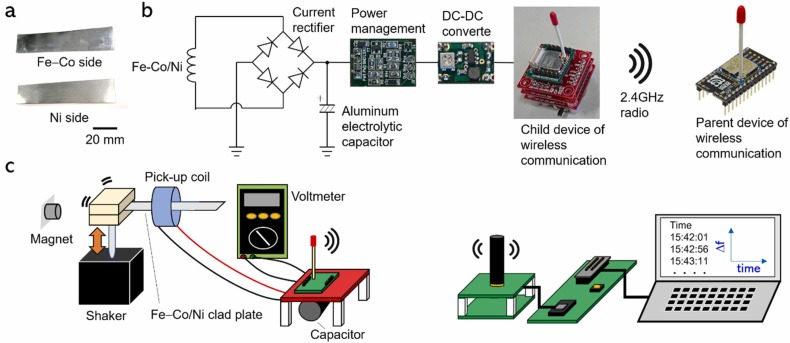

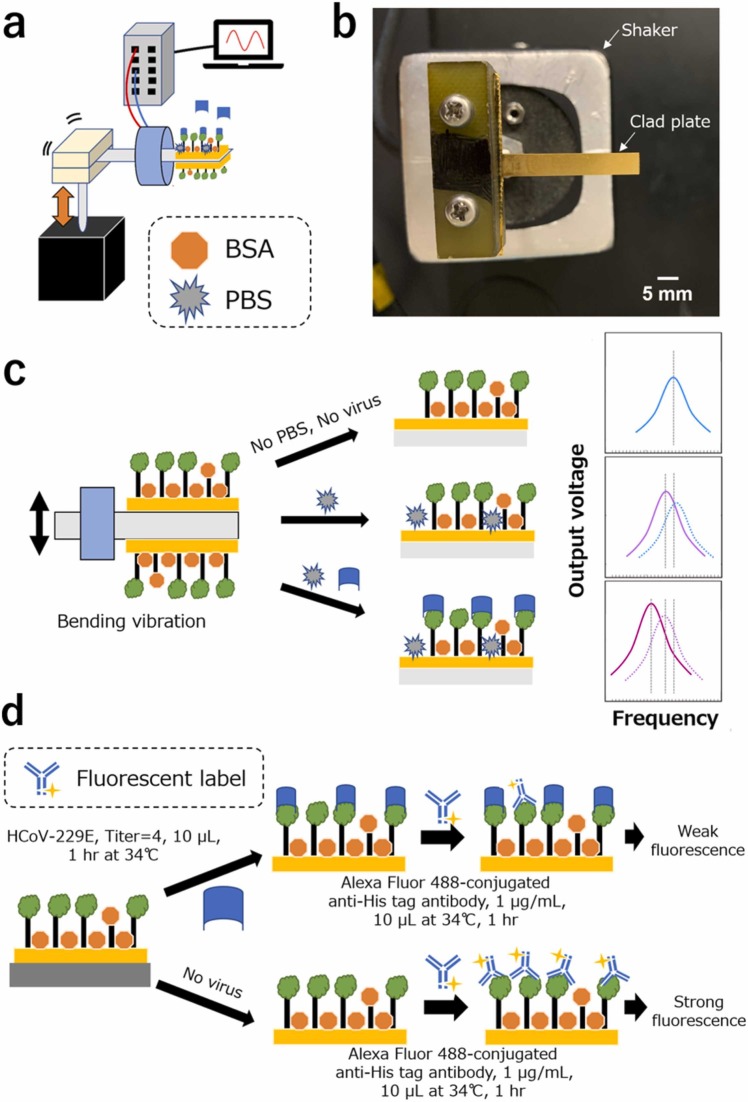

Here, we estimated dynamic characteristics such as changes in frequency Δf and output voltage ΔV because of the virus binding to the clad plate to demonstrate the possibility of developing a batteryless wireless virus sensing device ( Fig. 2). Consider the surface of the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate vibrating at the resonance frequency f 0 and covered with a biomolecular recognition element such as an antibody. The fundamental resonance frequency f 0 of the clad plate without antigen binding decreases to f 1 because the antigen binds to the antibody immobilized on the surface. This resonance frequency shift can be monitored via a pick-up coil. The Fe–Co/Ni clad plate serves as the bending vibration energy harvesting device, and the harvested power can supply the transmitting power to transmit information from the clad plate. Furthermore, our biosensor can detect the mass from the reduced resonance frequency Δf or communication time interval.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the magnetostrictive clad plate with vibration energy harvesting, wireless communication, and HCoV sensing capabilities. The power storage circuit controls the wireless communication IC.

HCoV-229E was purified. The used purification kit tested was the Retrovirus Purification Mini Kit, ViraTrap (Cat. V1172–02, Biomiga Inc.).

2.4. Receptor

To detect HCoV-229E, the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate was modified with a 150–160-kDA type II glycoprotein, a membrane peptidase, CD13/aminopeptidase N [59]. It is a multifunctional ectoenzyme (expressed as a dimer extending 10.5 nm on multiple cell surfaces). CD13, a biomarker for acute myeloid leukemia that cleaves N-terminal amino acids from peptides, inducing their inactivation or degradation, is critical in tumor invasion [60]. It acts as a receptor for HCoV-229E spike glycoprotein binding [61], [62], initiating cell entry and infection. The receptor-binding domain of HCoV-229E has even evolved to have a higher binding affinity than before (from ∼440 to ∼30 nm) [63]. CD13 is frequently used as a receptor for HCoV-229E in cell-based assays or as a receptor for HCoV-229E spike protein. Here, we used CD13 only as a bioreceptor for HCoV-229E. The viability of this capture method, i.e., using CD13 as a biorecognition layer for HCoV-229E, was first confirmed using fluorescence microscopy and amino silane-treated glass slides (Appendix A).

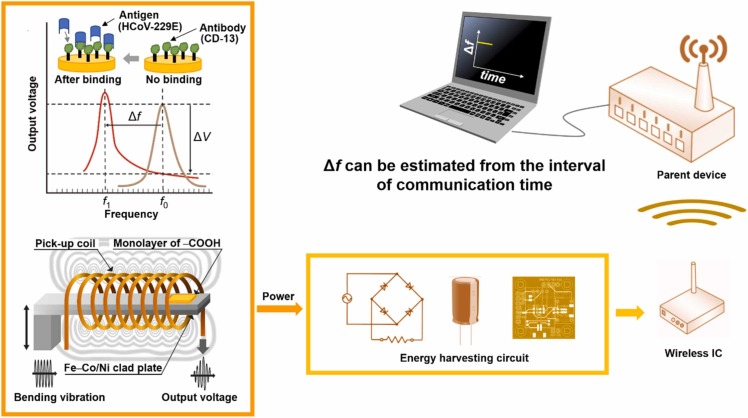

Fig. 3 shows a schematic of the biofunctionalization for the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate. The clad plate, with a length of 30 mm, a width of 5 mm, and a thickness of 0.2 mm, was sputtered with an Au film on both sides to promote biofunctionalization and prevent surface rust. The Fe–Co/Ni clad plate was then cleaned by immersing it in Milli-Q, acetone, isopropanol, and 99.5% ethanol, in that order. Ultrasonication is not recommended because the gold (Au) film may disintegrate, particularly on Ni. The Fe–Co/Ni clad plate was dropped in 10-mM 11-MUA (2 mL in ethanol, from Sigma-Aldrich) in a 2-mL test tube overnight at room temperature, covered in Al foil to protect it from light. Then, 11-MUA formed a SAM with –COOH groups on the surface. The Fe–Co/Ni clad plate was rinsed first in ethanol and then in the MES buffer solution (pH 5.5). Then, it was immersed in 40-mM EDC (from Nacalai Tesque) and 10-mM sulfo- NHS (from Nacalai Tesque) in the MES buffer solution (pH 5.5) for 2 h at room temperature, covered in Al foil to protect it from light. EDC/NHS reacted with –COOH groups to form an amine-reactive sulfo-NHS ester. The Fe–Co/Ni clad plate was immersed in a CD13 protein solution overnight at room temperature for virus detection experiments. Similarly, CD13 (25 µg/mL) was diluted in the MES buffer solution.

Fig. 3.

Biofunctionalization and measurement steps for the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate.

2.5. Sensor testing

Fig. 4(a) shows the HCoV-229E sensing test setup. The experiment was conducted using a CD13-modified Fe–Co/Ni clad plate under bending vibration. CD13 was immobilized using a SAM of –COOH groups forming amide bonds with –NH2 groups on CD13. The CD13-modified Fe–Co/Ni clad plate was then rinsed with PBS at a pH of 7.4 to eliminate unreacted CD13. The CD13-modified clad plate then underwent a BSA blocking step. The image of a clad plate cantilever before the bending vibration testing is shown in Fig. 4(b). The shaker applied a bending vibration, and the output voltage and frequency were measured. The resonance frequency and output voltage changes confirmed the feasibility of HCoV-229E sensing with the clad plate. When the CD13-modified Fe–Co/Ni clad plate was subjected to bending vibration to resonate, the resonance frequency of the clad plate reacting with PBS decreased. Furthermore, when the clad plate reacted with HCoV-229E, the resonance frequency decreased. The amount of change in this resonance frequency can be used to detect HCoV-229E (Fig. 4(c)).

Fig. 4.

(a) HCoV-229E sensing test setup using Fe–Co/Ni clad plate; (b) Photograph of a CD13-modified clad plate cantilever before the testing; (c) CD13-HCoV-229E pseudo-competitive binding assay; and (d) CD13-HCoV-229E pseudo-competitive binding assay.

After the HCoV-229E sensing test, the surface of the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate was incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-His tag antibody (1 µg/mL, in PBS solution) for 1 h at 34 ℃ (Fig. 4(d)). The Au surface was rinsed with PBS to remove unreacted anti-His tag antibody before observing it using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus) with Ex:460–490 nm and Em: 510 nm∼ filters. Fluorescence images were captured using exposure times of 250-, 400-, or 700 ms to observe the sample and a typical magnification of 10 × . Fluorescent labels react with CD13 and HCoV-229E. Therefore, if the HCoV-229E was attached, the fluorescence intensity would decrease.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Wireless communication

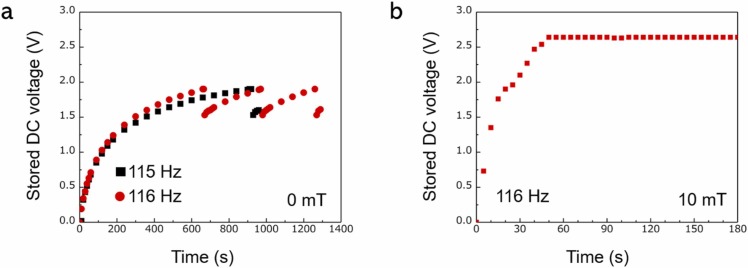

We used energy storage and a wireless communication system (Fig. 1(c)). The relationship between the DC voltage stored in the capacitor and time for the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate without the bias magnetic field at 115 and 116 Hz is shown in Fig. 5(a). The amount of stored DC voltage increases with time. The stored DC voltage reached ∼1.9 V after ∼670 s at the resonance state (116 Hz) and then dropped because a signal was wirelessly transmitted to the remote personal computer. Here, the signal was the time when the voltage dropped (not shown here). The DC voltage increased as electrical storage resumed. After ∼310 s, the stored DC voltage again reached ∼1.9 V and dropped because of the second wireless communication. The third wireless communication was ∼290 s. However, at 115 Hz, which deviated from the resonance frequency, it took some time to store the DC voltage, and the first signal was wirelessly transmitted after ∼930 s. As the frequency deviated from the resonant frequency, the output voltage decreased, and more time was required to store the DC voltage. Consequently, the intervals at which the signal could be transmitted increased. The clad plate could transmit signals with the power obtained by bending vibration at 115 Hz or 116 Hz using our developed wireless communication system. Thus, the signal transmission interval could be monitored without using the batteries. Furthermore, the transmission interval changes with frequency, making it possible to detect deviations from the resonance state from the time interval at which the signal was wirelessly transmitted. For example, if any substance adheres to the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate, the weight of the clad plate will change, as will the resonance frequency [50]. Therefore, the developed Fe–Co/Ni clad plate can detect substance adhesion using time interval information.

Fig. 5.

(a) DC voltage stored in the capacitor versus time under no bias magnetic field at 115 and 116 Hz; and (b) Experimental data that rapidly accumulates DC voltage under a bias magnetic field of 10 mT at 116 Hz. Even if the communication is transmitted once every 10 s, the storage DC voltage does not decrease.

Fig. 5(b) shows the relationship between the stored DC voltage in the capacitor and time for the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate in a biased magnetic field of 10 mT at 116 Hz. The stored DC voltage rapidly increased to ∼1.9 V, and the signal was wirelessly transmitted. Even after the wireless communication, the stored DC voltage did not decrease but rather increased, maintaining ∼2.6 V. In other words, the bending vibration of the developed Fe–Co/Ni clad plate generated an AC voltage, which was stored in the capacitor through the RC, and the maximum-stored DC voltage of the clad plate after rectification was 2.6 V. Note that the first signal was transmitted ∼20 s later and subsequent signals were transmitted every 10 s. The results showed that the energy stored in the capacitor did not decrease because the amount of power harvested by the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate was greater than the radio wave transmission energy. The capacitor was always completely charged because of the biased magnetic field. The amount of transmitted information (e.g., not only the time interval but also the frequency, and voltage value) or the signal strength to transmit information further away can be increased because of sufficient power. In this manner, not only the time interval but also the frequency and voltage value can be directly known, and the adhesion of substances can be detected.

3.2. HCoV-229E sensing

We demonstrated that HCoV-229E could sense the CD13 receptor on the clad plate under bending vibration for 1 h. The detection experiment was performed without a biased magnetic field for simplicity.

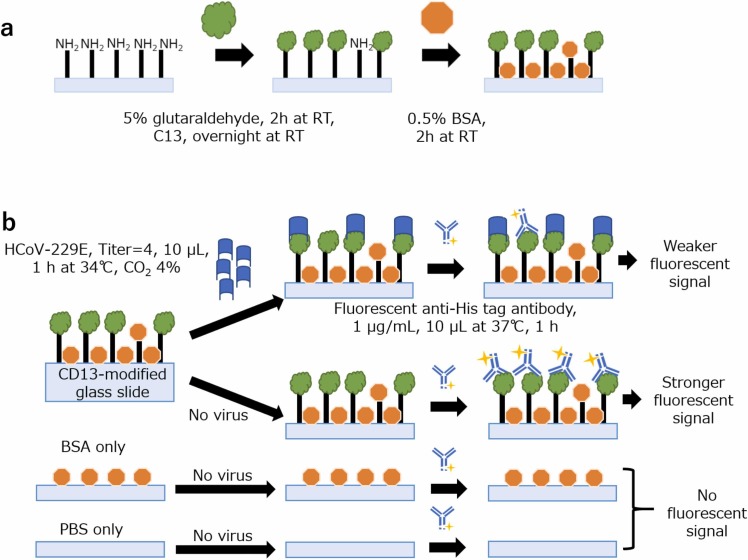

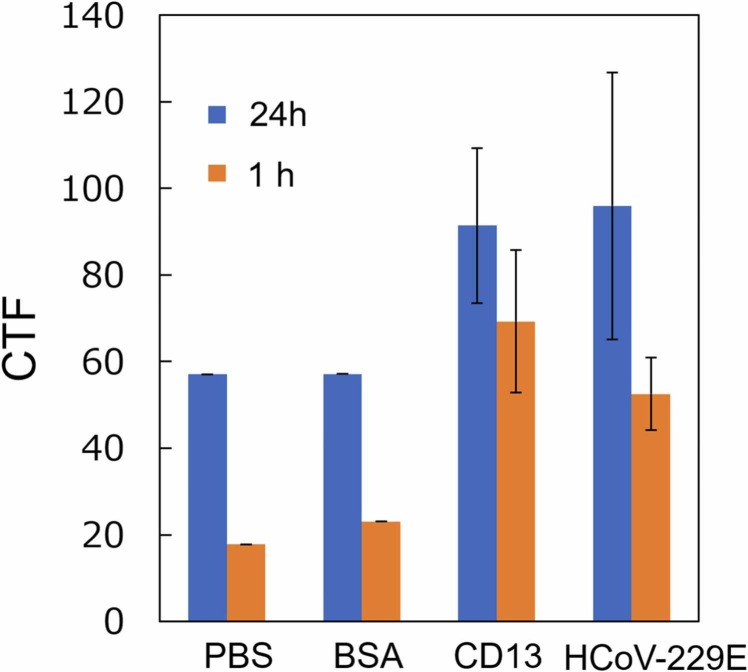

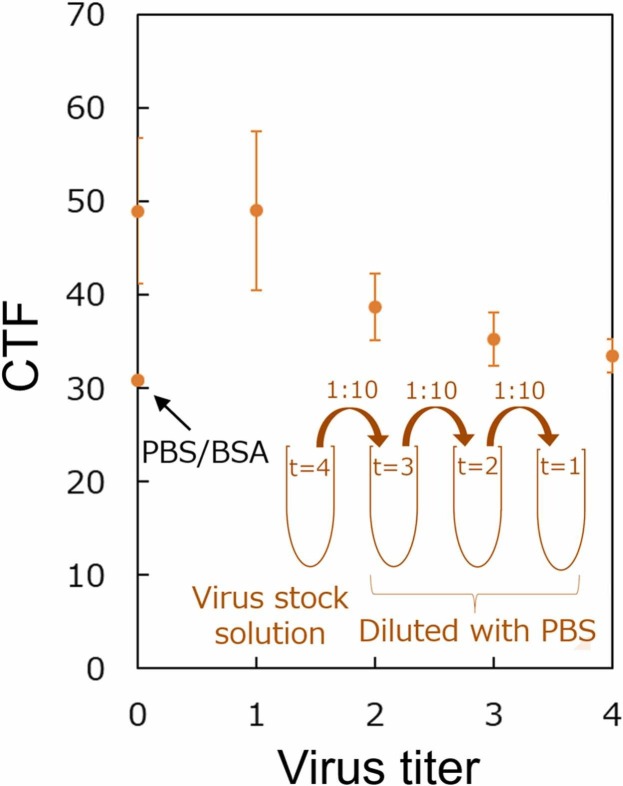

We first evaluated the CD13 binding to HCoV-229E on an APS glass slide surface (Fig. A.1 (a)). The CD13 immobilization onto the APS glass slide should not affect its receptor-binding capability with HCoV-229E spike glycoprotein because the receptor-binding domain was in a different location [64], [65]. Fluorescence assays with 1 and 24-h incubation periods were used to confirm this and to evaluate the CD13 binding to HCoV-229E (Fig. A.1 (b)). A pseudo-competitive binding assay was used by incubating HCoV-229E onto CD13-modified APS glass slides. Incubating the Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-His tag antibody can prevent the fluorescent probe from binding to the His tag on CD13 because of steric hindrance from the virus. Therefore, when the virus is bound to CD13, the fluorescence can decrease. CTF values of the fluorescence images of HCoV-229E are shown in Fig. 6. Here, CTF is defined by “Integrated density (Area of selected image Average mean fluorescence of background).” The results showed an increase in aggregated fluorescent signals in 24-h incubation compared with 1-h incubation, indicating that longer virus incubation times may affect CD13 protein integrity and induce clustering by crosslinking [66], [67], although amide bonds immobilizing CD13 protein are stable. Furthermore, the fluorescence of the virus after 1-h incubation decreased but not for 24 h. Note that incubation for 1 h was sufficient for binding the virus to CD13. However, incubation for 24 h induced an increase in nonspecific binding, as observed by higher CTF for negative controls PBS and BSA. Therefore, an incubation period of 1 h for the virus was used for CD13-virus binding conformations.

Fig. A.1.

(a) Biofunctionalization of the APS glass slide with a concentration of CD13; (b) CD13-HCoV-229E pseudo-competitive binding.

Fig. 6.

CTF values of the fluorescence images of HCoV-229E bound by CD13-modified APS glass slides. The graph plots the corrected total fluorescence values of fluorescence images for both 1 and 24-h incubation periods, n = 3.

We performed fluorescent detection of HCoV-229E using the CD13 proposed method as a bioreceptor after optimizing the virus incubation period and CD13 concentration. The virus stock solution of titer 4 (Log10TCID50 = 4) was serially diluted ten-fold to obtain virus titer = 1, 2, 3, 4. The CTF intensity gradually decreased in a sigmoidal pattern typically seen in competitive binding assays as the virus titer (virus quantity) increased ( Fig. 7). As the virus titer increased, the amount of virus bound onto CD13 increased, as did the steric hindrance, preventing fluorescent anti-His tag antibody from binding to CD13 and thus decreasing fluorescence intensity. Therefore, the biorecognition method of using CD13 as the bioreceptor for HCoV-229E can detect different virus concentrations.

Fig. 7.

CTF values of the fluorescence images of HCoV-229E bound by CD13-modified APS glass slides for various titers. The graph plots the corrected total fluorescence values of fluorescence images for both 1-h incubation periods, n = 3.

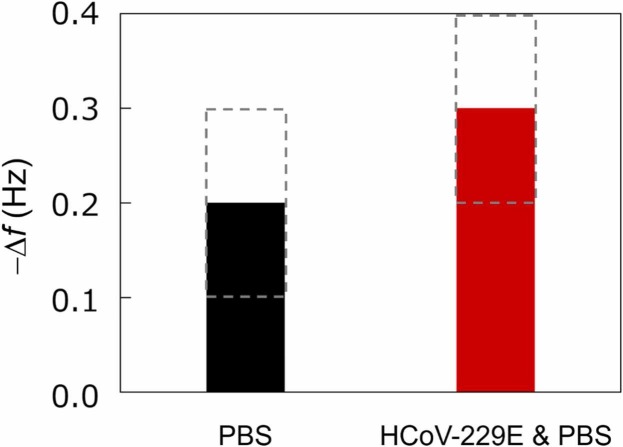

As shown in Fig. 3, we immobilized a CD13 biorecognition layer onto the surface of the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate. Then, we measured the resonance frequency changes in the CD13-modified clad plate cantilever under bending vibration due to HCoV-229E adsorption (Fig. 4(a) and (b)). The resonance frequency changes were expected in the tests because of the surface stress caused by HCoV-229E binding (Fig. 4(c)). The frequency change − Δf when the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate reacted only with PBS and HCoV-229E with PBS for 1 h ( Fig. 8). Squares with a gray-dashed line represent the measurement accuracy range. The frequency of the Fe–Co/Ni clad plate under bending vibration was measured before and after incubation in PBS and HCoV-229E sample solutions for 1 h at 33–34 °C and 4% CO2. In the clad plate reacted with HCoV-229E in PBS, a resonance frequency change of ∼0.3 Hz occurred before and after the reaction. However, in the clad plate that only reacted with PBS, a resonance frequency change of ∼0.2 Hz was observed. Using PBS for incubation could have caused the salt from the solution to remain on the clad plate, even after washing it in Milli-Q water before magnetostrictive measurement, affecting the results. Note that ∼0.1 Hz (obtained by subtracting 0.2 from 0.3) is only expected to cause a frequency change in HCoV-229E.

Fig. 8.

Frequency change due to PBS and HCoV-229E. Squares with a gray dashed line represent the range of measurement accuracy.

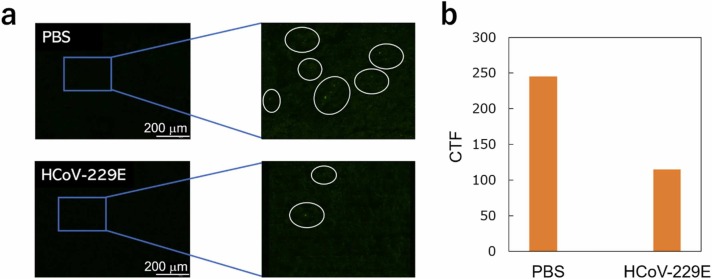

Finally, we conducted a detection experiment of HCoV-229E using the Fe–Co/Ni clad plates and confirmed CD13-virus binding via fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4(d)). Two CD13-modified clad plates were incubated in separate sample solutions with and without HCoV-229E for 1 h at 33–34 ℃ and 4% CO2. The clad plates were observed using a fluorescence microscope after additional incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-His tag antibody ( Fig. 9(a)). The plotted results similarly showed a decrease in fluorescence after incubation with HCoV-229E compared with incubation without HCoV-229E (Fig. 9(b)), indicating that the HCoV-229E was successfully bound to the CD13-modified clad plate. Therefore, the change in the frequency shown in Fig. 8 must be attributed to the HCoV-229E adsorption.

Fig. 9.

(a) Fluorescence images of HCoV-229E bound by CD13-modified Fe–Co/Ni clad plate; (b) fluorescence confirmation of HCoV-229E bound by CD13-modified Fe–Co/Ni clad plate.

The results showed that HCoV-229E can be detected using the frequency shift of the clad plate. However, the frequency change was only 0.1 Hz. It is difficult to detect the HCoV-229E amount smaller than the one used in this experiment because of the accuracy of the measuring equipment. Metglas can eliminate the disadvantage associated with a small shift because of its high magnetic permeability. However, materials with high magnetic permeability are not suitable for vibration energy harvesting [68], [69], making batteryless wireless communications impossible.

Table 1 compares our CD13-modified clad plate with two types of biosensors [70], [71] for coronavirus detection. The CD13-modified clad plate has several advantages; however, additional research is required to reduce the detection time. We must increase the repeatability and predict an optimal design to improve precision.

Table 1.

Techniques applied for detecting coronavirus. In the electrochemical method, i0 is the square wave voltammetry current measured at the antigen-modified electrodes after blocking with 1% BSA, and i is the current measured after incubating the sensor with a mixture of HCoV antibodies.

| Method | Virus type | Titer/Concentration | Sensitivity | Binding time | Advantage | Future work | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetostrictive | HCoV-229E | Log10TCID50 = 4, 10 μL | Δf = 0.1 Hz (f0 = ∼0.1 kHz) | 1 h | Battery-less Wireless Simple configuration Flexibility |

Increasing repeatability and precision | This study |

| Piezoelectric | SARS-CoV | 1 μg/mL | Δf = 585 Hz (f0 = 9 MHz) | 2 min | Repeatability Rapid |

Increasing stability and precision | [70] |

| Electrochemical | HCoV-OC43 | 0.4 pg/mL | (i0 − i)/i0 = 0.38 | 20 min | Repeatability Stability Highly sensitive Low cost |

Further testing for patient and healthy samples | [71] |

Here, only HCoV-229E was considered; however, our magnetostrictive Fe–Co/Ni clad plate can be used to detect other species, such as HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43, or HCoV-HKU1, as well as SARS-CoV-2. This is a challenging research area, but progress will be made sooner or later.

4. Conclusions

This study examined vibration energy harvesting, wireless communication, and HCoV-229E detectability using Fe–Co/Ni clad plates. The research developed a gravimetric-based biosensor modified using a novel biorecognition method for HCoV-229E detection. CD13, a well-known virus receptor that is frequently used in cell-based assays, was immobilized onto the clad plate surface.

We stored the DC voltage and succeeded in transmitting wireless information once every 5 min using a high energy harvesting ability peculiar to magnetostrictive materials. Additional storage capacity is realized using a biased magnetic field, and a signal can be transmitted once every 10 s. After confirming the feasibility of using CD13 as a bioreceptor for HCoV-229E detection using fluorescence microscopy and a pseudo-competitive binding assay method, it was immobilized on the magnetostrictive Fe–Co/Ni cantilever for dynamic characteristics measurement. The results showed that the novel biorecognition method based on CD13 was successful, even with the magnetostrictive cantilever biosensor. The experiments with HCoV-229E revealed changes of ∼0.1 Hz in the resonance frequency before and after the reaction.

In this study, HCoV-229E was successfully detected. The output voltage was increased using a biased magnetic field, and the information transmission function to the clad plate was enhanced. Our CD13-modified magnetostrictive Fe–Co/Ni clad plate may be useful in detecting other HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, and SARS-CoV-2, in addition to HCoV-229E; thus, it is important to assess their effect on the dynamic characteristics of the CD13-modified Fe–Co/Ni clad plate. To summarize, real-time detection of the frequency change can be performed by simultaneously capturing the HCoV and transmitting wireless information. The interval of wireless communication time can enable us to predict frequency changes and detect viruses. Soon, a monitoring system that transmits HCoV detection without batteries will be realized.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Daiki Neyama: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Siti Masturah Binti Fakhruddin: Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Kumi Y. Inoue: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. Hiroki Kurita: Validation, Investigation. Shion Osana: Methodology, Resources. Naoto Miyamoto : Methodology, Investigation. Tsuyoki Tayama: Resources. Daiki Chiba: Resources. Masahito Watanabe: Resources. Hitoshi Shiku: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Fumio Narita : Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly acknowledge the support of this work by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) Matching Planner Program under Grant No. JPMJTM20K3 and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) under Grant No. 22H00183. The technical assistance of Jin Ono, Industrial Technology Institute, Miyagi Prefectural Government, on the circuit design process is greatly appreciated.

Biographies

Daiki Neyama is a master’s student in the Department of Materials Processing, Graduate School of Engineering, Tohoku University (Japan). His research interests lie in magnetostrictive materials design for energy harvesting technology.

Siti Masturah binti Fakhruddin is a Ph.D. student in the Graduate School of Environmental Studies at Tohoku University (Japan). She obtained her Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Biomolecular Engineering from the same university in 2017 and 2019, respectively. Her research is based on electrochemical analysis, specifically biosensors.

Kumi Y. Inoue is an associate professor in Faculty of Engineering, University of Yamanashi (Japan). She worked for Miyagi Miso and Soy-sauce Industries Cooperative Association as a researcher (1995–2005). From 2005, she worked in Tohoku University as a researcher. She received her Ph.D. degree from Tohoku University in 2010. She worked as a Research Fellow and an Assistant Professor in the Micro System Integration Center, Tohoku University, and then as a Lecturer and Associate Professor in Graduate School of Environmental Studies, Tohoku University. She proceeds with her research for highly sensitive and easy handling biosensors and electrochemical bioimaging systems.

Hiroki Kurita is an assistant professor in the Department of Frontier Sciences for Advanced Environment, Graduate School of Environmental Studies, Tohoku University (Japan). His current research interests involve the development of piezoelectric and magnetostrictive materials for energy harvesting and sensor applications. He also ad-dresses the development of high specific strength metal and ceramic matrix composites, and recently studies the three-dimensional printing of fiber-reinforced ceramic matrix composites.

Shion Osana is a Project Assistant Professor at the Graduate School of Biomedical Engineering, Tohoku University (Japan). His research area is molecular biology, specializing in animal and cellular experiments and virus research. In particular, his research interests are related to the maintenance mechanism of protein metabolism in skeletal muscle cells.

Naoto Miyamoto is an associate professor in New Industry Creation Hatchery Center, Tohoku University (Japan). His current research interests include low-power and low-noise reconfigurable circuit design, especially for robotics and sports motion analysis, using kinematic global navigation satellite systems.

Tsuyoki Tayama is an engineer at Tohoku Steel Co. Ltd. (Japan). He is the leader of the applied equipment team in the highly functional materials division. His research interest is focused on the magnetostrictive vibration energy harvesting for the IoT and magnetostrictive actuators for agriculture.

Daiki Chiba is an engineer at Tohoku Steel Co. Ltd. (Japan). He belongs to the heat treatment plant of the composite processing division and is involved in the research and development of diffusion bonding. He works on the development of composite materials using diffusion bonding technology.

Masahito Watanabe belongs to the materials development team of the high-performance materials division at Tohoku Steel Co. Ltd. (Japan). He is researching and developing magnetic/magnetostrictive materials and manufacturing processes for these materials.

Hitoshi Shiku received his Doctorate of Engineering from Tohoku University in 1997. Then, as an associate professor in Graduate School of Environmental Studies, Tohoku University (2003–2016), he researched bioelectrochemistry, multianalyte sensing, and development of bioanalytical tools based on scanning probe microscopy. He is currently a professor in the Department of Biomolecular Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Tohoku University (Japan).

Fumio Narita is currently a professor at the Department of Frontier Sciences for Advanced Environment, Graduate School of Environmental Studies, Tohoku University (Japan). He is engaged in research to design and develop piezoelectric/magnetostrictive materials and structures in energy harvesting and self-powered environmental monitoring. He extensively uses state-of-the-art electromagneto–mechanical characterization techniques in combination with computational multiscale modeling to understand the fundamental structure–property relationships of complex multifunctional composite materials.

Appendix A.

Here a glutaraldehyde crosslinking method immobilized CD13 onto the glass slide surface. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-His tag antibody was used as the fluorescent label, bonding to the His-tagged CD13-modified glass slide surface.

The glass slide (TF2404A, APS-coated, 24 wells, 4 cm diameter, Matsunami) was ultrasonicated in Milli-Q water, acetone, isopropanol, and 99.5% ethanol in that order. Glutaraldehyde (5%, 20 μL) was dropped onto each well, and the glass slide was stored in a plastic Petri dish (with a wet tissue to provide a humid environment) for 2 h at room temperature. The glass slide was then rinsed thoroughly in Milli-Q water. CD13 was added to each well (10 μL, 25 μg/mL, Recombinant Human CD13 protein with His tag, ab276194, Abcam) and incubated overnight at room temperature to ensure maximum CD13 immobilization. The glass slide was then rinsed with PBS to remove the unreacted CD13 protein. BSA (10 μL, 0.5%) was then added to each well to block the unreacted glutaraldehyde and incubated for 2 h at room temperature (see Fig. A.1 (a)).

Fig. A.1 (b) shows a schematic of CD13-HCoV-229E pseudo-competitive binding. The glass slide was then rinsed with PBS before being incubated with the virus solution for 1 h at 34 ℃ with 4% CO2 level for optimum virus incubation environment. These conditions mimic the air that enters the body. The glass slide was rinsed again with PBS to remove unreacted virus particles before incubating with BSA (0.5%) to prevent nonspecific binding. The glass slide was rinsed with PBS before incubating with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-His tag antibody (1 μg/mL, in PBS solution) for 1 h or 24 h at 37 ℃. The glass slide with no virus was also incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-His tag antibody.

The glass slide was rinsed with PBS to remove unreacted anti-His tag antibody before being observed using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus) with a filter for Ex: 460–490 nm and Em: 510 nm∼. The fluorescence images were observed with exposure times of 250 or 400 or 700 msec and 10 magnifications. Steric hindrance from the virus prevents the fluorescent label from binding, implying that a decrease in the fluorescence signal indicates successful virus binding.

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Long M.J.C., Aye Y. Science’s response to CoVID-19. Chem. Med. Chem. 2021;16:2288–2314. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202100079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goud K.Y., Reddy K.K., Khorshed A., Kumar V.S., Mishra R.K., Oraby M., Ibrahim A.H., Kim H., Gobi K.V. Electrochemical diagnostics of infectious viral diseases: trends and challenges. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021;180 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2021.113112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Payandehpeyman J., Parvini N., Moradi K., Hashemian N. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 using antibody-antigen interactions with graphene-based nanomechanical resonator sensors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021;4:6189–6200. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.1c00983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahanta N., Saxena V., Pandey L.M., Batra P., Dixit U.S. Performance study of a sterilization box using a combination of heat and ultraviolet light irradiation for the prevention of COVID-19. Environ. Res. 2021;198 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Etienne E.E., Nunna B.B., Talukder N., Wang Y., Lee E.S. Covid-19 biomarkers and advanced sensing technologies for point-of-care (Poc) diagnosis. Bioengineering. 2021;8:98. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering8070098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen P.Q., Soenksen L.R., Donghia N.M., Angenent-Mari N.M., de Puig H., Huang A., Lee R., Slomovic S., Galbersanini T., Lansberry G., Sallum H.M., Zhao E.M., Niemi J.B., Collins J.J. Wearable materials with embedded synthetic biology sensors for biomolecule detection. Nat. Biotech. 2021;39 doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-00950-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fakhruddin S.M., Ino K., Inoue K.Y., Nashimoto Y., Shiku H. Bipolar electrode-based electrochromic devices for analytical applications – a review. Electroanalysis. 2021;33:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sung W.-H., Tsao Y.-T., Shen C.-J., Tsai C.-Y., Cheng C.-M. Small-volume detection: platform developments for clinically-relevant applications. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19:114. doi: 10.1186/s12951-021-00852-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Numan A., Singh S., Zhan Y., Li L., Khalid M., Rilla K., Ranjan S., Cinti S. Advanced nanoengineered—customized point-of-care tools for prostate-specific antigen. Microchim. Acta. 2022;189:27. doi: 10.1007/s00604-021-05127-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Y. Wang, Y. Yu, X. Wei, F. Narita, Self-powered wearable piezoelectric monitoring of human motion and physiological signals for the post pandemic era: a review, Adv. Mater. Tech., in press. 10.1002/admt.202200318. [DOI]

- 11.Singh B., Datta B., Ashish A., Dutta G. A comprehensive review on current COVID-19 detection methods: From lab care to point of care diagnosis. Sens. Int. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.sintl.2021.100119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naikoo G.A., Arshad F., Hassan I.U., Awan T., Salim H., Pedram M.Z., Ahmed W., Patel V., Karakoti A.S., Vinu A. Nanomaterials-based sensors for the detection of COVID-19: a review. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2022;7 doi: 10.1002/btm2.10305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seo G., Lee G., Kim M.J., Baek S.-H., Choi M., Ku K.B., Lee C.-S., Jun S., Park D., Kim H.G., Kim S.-J., Lee J.-O., Kim B.T., Park E.C., Kim S.I. Rapid detection of COVID-19 causative virus (SARS-CoV-2) in human nasopharyngeal swab specimens using field-effect transistor-based biosensor. ACS Nano. 2020;14:5135–5142. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c02823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui T.-R., Qiao Y.-C., Gao J.-W., Wang C.-H., Zhang Y., Han L., Yang Y., Ren T.-L. Ultrasensitive detection of COVID-19 causative virus (SARS-CoV-2) spike protein using laser induced graphene field-effect transistor. Molecules. 2021;26:6947. doi: 10.3390/molecules26226947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farzin L., Sadjadi S., Sheini A., Mohagheghpour E. A nanoscale genosensor for early detection of COVID-19 by voltammetric determination of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) sequence of SARS-CoV-2 virus. Microchim. Acta. 2021;188:121. doi: 10.1007/s00604-021-04773-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran V.V., Tran N.H.T., Hwang H.S., Chang M. Development strategies of conducting polymer-based electrochemical biosensors for virus biomarkers: potential for rapid COVID-19 detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021;182 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2021.113192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding S., Chen G., Wei Y., Dong J., Du F., Cui X., Huang X., Tang Z. Sequence-specific and multiplex detection of COVID-19 virus (SARS-CoV-2) using proofreading enzyme-mediated probe cleavage coupled with isothermal amplification. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021;178 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2021.113041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandey L.M. Design of engineered surfaces for prospective detection of SARS-CoV-2 using quartz crystal microbalance-based techniques. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2020;17:425–432. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2020.1794831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandey L.M. Surface engineering of personal protective equipments (PPEs) to prevent the contagious infections of SARS-CoV-2. Surf. Eng. 2020;36:901–907. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu L., Guo X., Lee C. Promoting smart cities into the 5G era with multi-field Internet of Things (IoT) applications powered with advanced mechanical energy harvesters. Nano Energy. 2021;88 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narita F., Wang Z., Kurita H., Li Z., Shi Y., Jia Y., Soutis C. A review of piezoelectric and magnetostrictive biosensor materials for detection of COVID-19 and other viruses. Adv. Mater. 2021;33 doi: 10.1002/adma.202005448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shindo Y., Narita F. Dynamic bending/torsion and output power of S-shaped piezoelectric energy harvesters. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 2014;10:305–311. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mori K., Horibe T., Ishikawa S., Shindo Y., Narita F. Characteristics of vibration energy harvesting using giant magnetostrictive cantilevers with resonant tuning. Smart Mater. Struct. 2015;24 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narita F., Fox M. A review on piezoelectric, magnetostrictive, and magnetoelectric materials and device technologies for energy harvesting applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2018;20 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narita F., Nagaoka H., Wang Z. Fabrication and impact output voltage characteristics of carbon fiber reinforced polymer composites with lead-free piezoelectric nano-particles. Mater. Lett. 2019;236:487–490. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Z., Kurita H., Nagaoka H., Narita F. Potassium sodium niobate lead-free piezoelectric nanocomposite generators based on carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer electrodes for energy-harvesting structures. Compos. Sci. Tech. 2020;199 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shindo Y., Narita F., Mikami M. Double torsion testing and finite element analysis for determining the electric fracture properties of piezoelectric ceramics. J. Appl. Phys. 2005;97 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narita F., Shindo Y., Saito F. Cyclic fatigue crack growth in three-point bending PZT ceramics under electromechanical loading. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2007;90:2517–2524. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hara Y., Zhou M., Li A., Otsuka K., Makihara K. Piezoelectric energy enhancement strategy for active fuzzy harvester with time-varying and intermittent switching. Smart Mater. Struct. 2021;30 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xing J., Chen H., Jiang L., Zhao C., Tan Z., Huang Y., Wu B., Chen Q., Xiao D., Zhu J. High performance BiFe0.9Co0.1O3 doped KNN-based lead-free ceramics for acoustic energy harvesting. Nano Energy. 2021;84 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sezer N., Koç M. A comprehensive review on the state-of-the-art of piezoelectric energy harvesting. Nano Energy. 2021;80 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takaishi K., Kubota Y., Kurita H., Wang Z., Narita F. Fabrication and electromechanical characterization of mullite ceramic fiber/thermoplastic polymer piezoelectric composites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2022;105:308–316. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Z., Maruyama K., Narita F. A novel manufacturing method and structural design of functionally graded piezoelectric composites for energy harvesting. Mater. Des. 2022;214 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vijayakanth T., Liptrot D.J., Gazit E., Boomishankar R., Bowen C.R. Recent advances in organic and organic–inorganic hybrid materials for piezoelectric mechanical energy harvesting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022;32 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen B., Jia Y., Narita F., Wang C., Shi Y. Multifunctional cellular sandwich structures with optimised core topologies for improved mechanical properties and energy harvesting performance. Compos. B. 2022;238 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z., Mori K., Nakajima K., Narita F. Fabrication, modeling and characterization of magnetostrictive short fiber composites. Materials. 2020;13:1494. doi: 10.3390/ma13071494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Z., Wang Z., Nakajima K., Neyama D., Narita F. Structural design and performance evaluation of FeCo/epoxy magnetostrictive composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021;210 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu H., Li W., Sun X., Cong C., Cao C., Zhao Q. Enhanced the capability of magnetostrictive ambient vibration harvester through structural configuration, pre-magnetization condition and elastic magnifier. J. Sound Vib. 2021;492 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujieda S., Gorai N., Kawamata T., Simura R., Fukuda T., Suzuki S. Performance of vibration power generators using single crystal and polycrystal magnetic cores of Fe-Ga alloys. Mater. Sci. Forum. 2021;1016:453–457. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu K.-F., Zhang Y.-W., Zang J., Niu M.-Q., Chen L.-Q. Integration of vibration control and energy harvesting for whole-spacecraft: experiments and theory. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021;161 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu L., Wu H., Zhang Q., You H., Jiao J., Luo H., Wang Y., Gao A., Duan C. Self-powered energy-harvesting magnetic field sensor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2022;120 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sowjanya P., Kumar N.P., Chelvane A., Reddy M.V.R. Synthesis and analysis of low field high magnetostrictive Ni-Co ferrite for magneto-electric energy harvesting applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 2022;279 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurita H., Lohmuller P., Laheurte P., Nakajima K., Narita F. Additive manufacturing and energy-harvesting performance of honeycomb-structured magnetostrictive Fe52–Co48 alloys. Addit. Manuf. 2022;54 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joshi P., Kumar S., Jain V.K., Akhtar J., Singh J. Distributed MEMS mass-sensor based on piezoelectric resonant micro-cantilevers. J. Micro Syst. 2019;28:382–389. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erofeev A.S., Gorelkin P.V., Kolesov D.V., Kiselev G.A., Dubrovin E.V., Yaminsky I.V. Label-free sensitive detection of influenza virus using PZT discs with a synthetic sialylglycopolymer receptor layer. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019;6 doi: 10.1098/rsos.190255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saberkari H., Ghavifekr H.B., Shamsi M. Comprehensive performance study of magneto cantilevers as a candidate model for biological sensors used in lab-on-a-chip applications. J. Med. Signals Sens. 2015;5:77–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo X., Sang S., Guo J., Jian A., Duan Q., Ji J., Zhang Q., Zhang W. A magnetoelastic biosensor based on E2 glycoprotein for wireless detection of classical swine fever virus E2 antibody. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:15626. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15908-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo X., Liu R., Li H., Wang J., Yuan Z., Zhang W., Sang S. A novel NiFe2O4/paper-based magnetoelastic biosensor to detect human serum albumin. Sensors. 2020;20:5286. doi: 10.3390/s20185286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y., Shi Y., Narita F. Design and finite element simulation of metal-core piezoelectric fiber/epoxy matrix composites for virus detection. Sens. Actuators A. 2021;327 doi: 10.1016/j.sna.2021.112742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mori K., Wang Y., Katabira K., Neyama D., Onodera R., Chiba D., Watanabe M., Narita F. On the possibility of developing magnetostrictive Fe-Co/Ni clad plate with both vibration energy harvesting and mass sensing elements. Materials. 2021;14:4486. doi: 10.3390/ma14164486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li D., Yuan Z., Huang X., Li H., Guo X., Zhang H., Sang S. Surface functionalization, bioanalysis and applications: progress of new magnetoelastic biosensors. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2022;24 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gaunt E.R., Hardie A., Claas E.C., Simmonds P., Templeton K.E. Epidemiology and clinical presentations of the four human coronaviruses 229E, HKU1, NL63, and OC43 detected over 3 years using a novel multiplex real-time PCR method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:2940–2947. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00636-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coden M.E., Loffredo L.F., Abdala-Valencia H., Berdnikovs S. Comparative study of sars-cov-2, sars-cov-1, mers-cov, hcov-229e and influenza host gene expression in asthma: importance of sex, disease severity, and epithelial heterogeneity. Viruses. 2021;13:1081. doi: 10.3390/v13061081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Demers-Mathieu V., DaPra C., Mathijssen G., Sela D.A., Järvinen K.M., Seppo A., Fels S., Medo E. Human milk antibodies against s1 and s2 subunits from sars-cov-2, hcov-oc43, and hcov-229e in mothers with a confirmed covid-19 pcr, viral symptoms, and unexposed mothers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:1749. doi: 10.3390/ijms22041749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Song X., Shi Y., Ding W., Niu T., Sun L., Tan Y., Chen Y., Shi J., Xiong Q., Huang X., Xiao S., Zhu Y., Cheng C., Fu Z.F., Liu Z.-J., Peng G. Cryo-EM analysis of the HCoV-229E spike glycoprotein reveals dynamic prefusion conformational changes. Nat. Comm. 2021;12:141. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20401-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma Q., Wang Z., Chen R., Lei B., Liu B., Jiang H., Chen Z., Cai X., Guo X., Zhou M., Huang J., Li X., Dai J., Yang Z. Effect of Jinzhen granule on two coronaviruses: the novel SARS-CoV-2 and the HCoV-229E and the evidences for their mechanisms of action. Phytomedicine. 2022;95 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kurita H., Fakhruddin S.M.B., Neyama D., Inoue K.Y., Tayama T., Chiba D., Watanabe M., Shiku H., Narita F. Detection of virus-like particles using magnetostrictive vibration energy harvesting. Sens. Actuators A. 2022;345 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Japan patent No. 6796843.

- 59.Vijgen L., Keyaerts E., Zlateva K., Ranst M.V. Identification of six new polymorphisms in the human coronavirus 229E receptor gene (aminopeptidase N/CD13) Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;8:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wentworth D.E., Holmes K.V. Molecular determinants of species specificity in the coronavirus receptor aminopeptidase N (CD13): influence of N-linked glycosylation. J. Virol. 2001;75:9741–9752. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9741-9752.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yeager C.L., Ashmun R.A., Williams R.K., Cardellichio C.B., Shapiro L.H., Look A.T., Holmes K.V. Human aminopeptidase N is a receptor for human coronavirus 229E. Nature. 1992;357:420–422. doi: 10.1038/357420a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kolb A.F., Maile J., Heister A., Siddell S.G. Characterization of functional domains in the human coronavirus HCV 229E receptor. J. Gen. Virol. 1996;77:2515–2521. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-10-2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wong A.H.M., Tomlinson A.C.A., Zhou D., Satkunarajah M., Chen K., Sharon C., Desforges M., Talbot P.J., Rini J.M. Receptor-binding loops in alphacoronavirus adaptation and evolution. Nat. Comm. 2017;8:1735. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01706-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kolb A.F., Hegyi A., Siddell S.G. Identification of residues critical for the human coronavirus 229E receptor function of human aminopeptidase. New J. Gen. Virol. 1997;78:2795–2802. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-11-2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Z., Tomlinson A.C.A., Wong A.H.M., Zhou D., Desforges M., Talbot P.J., Benlekbir S., Rubinstein J.L., Rini J.M. The human coronavirus HCoV‐229E S‐protein structure and receptor binding. Biochem. Chem. Biol. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.51230. (eLife) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nomura R., Kiyota A., Suzaki E., Kataoka K., Ohe Y., Miyamoto K., Senda T., Fujimoto T. Human coronavirus 229E binds to CD13 in rafts and enters the cell through caveolae. J. Virol. 2004;78:8701–8708. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8701-8708.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mina-Osorio P., Winnicka B., O’Conor C., Grant C.L., Vogel L.K., Rodriguez-Pinto D., Holmes K.V., Ortega E., Shapiro L.H. CD13 is a novel mediator of monocytic/endothelial cell adhesion. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008;84:448–459. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roundy S. On the effectiveness of vibration-based energy harvesting. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2005;16:809–823. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nakajima K., Tanaka S., Mori K., Kurita H., Narita F. Effects of heat treatment and Cr content on the microstructures, magnetostriction, and energy harvesting performance of Cr-doped Fe–Co alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2022;24 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zuo B., Li S., Guo Z., Zhang J., Chen C. Piezoelectric immunosensor for SARS-associated coronavirus in sputum. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:3536–3540. doi: 10.1021/ac035367b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Layqah L.A., Eissa S. An electrochemical immunosensor for the corona virus associated with the Middle East respiratory syndrome using an array of gold nanoparticle-modified carbon electrodes. Microchim. Acta. 2019;186:224. doi: 10.1007/s00604-019-3345-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.