Abstract

Fourteen of the 38 C-terminal repeats from Clostridium difficile toxin A (14CDTA) were cloned and expressed either with an N-terminal polyhistidine tag (14CDTA-HIS) or fused to the nontoxic binding domain from tetanus toxin (14CDTA-TETC). The recombinant proteins were successfully purified by bovine thyroglobulin affinity chromatography. Both C. difficile toxin A fusion proteins bound to known toxin A ligands present on the surface of rabbit erythrocytes. Intranasal immunization of BALB/c mice with three separate 10-μg doses of 14CDTA-HIS or -TETC generated significant levels of anti-toxin A serum antibodies compared to control animals. The coadministration of the mucosal adjuvant heat labile toxin (LT) from Escherichia coli (1 μg) significantly increased the anti-toxin A response in the serum and at the mucosal surface. Importantly, the local and systemic antibodies generated neutralized toxin A cytotoxicity. Impressive systemic and mucosal anti-toxin A responses were also seen following coadministration of 14CDTA-TETC with LTR72, an LT derivative with reduced toxicity which shows potential as a mucosal adjuvant for humans.

Clostridium difficile is the primary cause of antibiotic-associated disease in both nosocomial and tertiary care environments (20, 39). C. difficile-associated disease (CDAD) results from disruption of the resident bowel microflora, usually by the administration of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents which allows the organism to flourish (31). Disease symptoms characteristically range from self-limiting diarrhea to pseudomembranous colitis, which can be life threatening (16, 32). The population at risk is substantial and includes not only patients on antimicrobial therapy, but also the immunocompromised and the elderly (41). Hospital outbreaks are well documented and result in ward closures and, in extreme instances, hospital closures (2). Currently, the major treatment against CDAD is vancomycin (15), which is expensive and often fails to eradicate the organism (51). Relapses or reinfections are common (52), and the worldwide appearance of vancomycin-resistant enterococci has added complications (38). Clearly, new preventative strategies against CDAD are required.

Two large exotoxins, toxin A (308 kDa) and toxin B (270 kDa), have been determined as the main virulence determinants for C. difficile (34). These toxins have identical intracellular modes of action (9, 23) and are cytotoxic for various cell lines in vitro (46). A striking feature of these toxins is the repetitive nature of the amino acid sequence at the carboxyl terminus of the protein (1, 13). In the case of toxin A, this region is composed of 38 contiguous repeat sequences which encode the receptor-binding domain of toxin A (33, 40). One of these repeat sequences, the class IIB repeat, is of particular interest because a synthetic decapeptide encoding amino acids conserved within this repeat was shown to promote cellular attachment in vitro (53). Toxin A has been shown to be the primary mediator of tissue damage within the gastrointestinal tract, as direct administration of toxin A alone induces tissue damage characteristic of infection (35, 37). Recently, the direct binding of toxin A to human colonic epithelial cells has been demonstrated (42).

To date, the experimental vaccine strategies employed to induce a protective anti-toxin A response have been limited, although parenteral immunization with small amounts of purified toxin A has been shown to solidly protect rabbits against toxin-induced death (26). However, this form of immunization was unable to prevent toxin-mediated mucosal damage. Indeed, mucosal damage appeared to be a prerequisite for protection, allowing toxin-neutralizing antibodies to be released from serum and into the intestinal lumen. This result suggests that the induction of a toxin-neutralizing, secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA)-mediated response at the mucosal surface, to prevent tissue damage, would be desirable. Toxin A-specific IgA harvested from human mucosa has been shown to inhibit toxin A from binding to intestinal brush border (25), thus validating the principle of anti-toxin A mucosal immunity.

Mucosal immunization with C. difficile toxoid vaccines has also been shown to protect against mucosal challenge by whole organisms (18, 45). However, chemically detoxified immunogens are not wholly satisfactory due to possible residual toxicity and the random structural and chemical modifications which occur to the antigen. In addition, formalin-inactivated molecules that cannot bind to or target mucosal surfaces have been described as being generally poorer mucosal immunogens than molecules that can successfully target receptors on the mucosal surface (8).

The nontoxic C-terminal repeat region of toxin A has been reported to be a good vaccine candidate. Immunization with a recombinant protein expressing 33 of the 38 C-terminal repeats generated a partially protective anti-toxin A response (33). Also, a synthetic peptide containing 10 conserved amino acids from the class IIB repeat stimulated toxin-neutralizing antibodies (53). Several studies have shown the induction of a toxin-neutralizing response to protect against whole-organism challenge in vivo (18, 45). Our goal, therefore, was to induce an antibody response against nontoxic fragments of the toxin A repeat region which would be able to neutralize the effects of the whole molecule systemically and at the mucosal surface. Such a fragment would be desirable as a component of a recombinant C. difficile vaccine.

We have previously shown all 14 C-terminal repeats of C. difficile toxin A (14CDTA) to be immunogenic when fused genetically to the nontoxic C-terminal domain (TETC) from tetanus toxin (TT) and delivered to the mucosal surface by attenuated Salmonella typhimurium (48). In the present study, we evaluate the immunogenicity of 14CDTA when administered directly to the murine nasal mucosa in a purified form. It is well documented that other bacterial toxins which bind to mucosal surfaces, such as heat labile toxin (LT) from Escherichia coli, can act as adjuvants, generating both systemic and local (IgA) responses to coadministered proteins (6, 12). The potential problem, however, of using such proteins in humans is the residual toxicity of the molecule. A genetically detoxified mutant, LTR72, has recently been developed and has the potential for use in humans (19). Data presented in this study shows the increased immunogenicity of 14CDTA at the mucosal surface when administered with either native LT or the LTR72 variant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and toxins.

S. typhimurium LB5010 (galE) and BRD915 (htrA) and plasmid pTECH-1 were kind gifts from Steve Chatfield, Medeva Development, Vaccine Research Unit, Imperial College, London, United Kingdom. E. coli BL21 (DE3) was obtained from Novagen, and plasmid pRSET-A was supplied by Invitrogen (De Schelp, The Netherlands). Bacteria were routinely cultivated in either Luria broth (LB) or on Luria-Bertani agar with or without ampicillin (100 μg/ml).

Whole toxin A, generously supplied by D. Lyerly, TechLab, Inc., Blacksburg, Va., was purified by thyroglobulin affinity chromatography as described (29). Native LT and the LTR72 variant were kind gifts from Mariagrazia Pizza, IRIS, Sienna, Italy (19). TETC was purified from Pichia pastoris and kindly supplied by Medeva Development, Vaccine Research Unit.

DNA manipulation.

Restriction enzymes and DNA ligase were purchased from Promega (Southampton, United Kingdom) and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Restriction enzyme-digested DNA was purified by using either S-300 HR Microspin columns (Pharmacia) or Prep-A-Gene purification resin (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom). PCR was carried out with a Perkin Elmer 9600 cycle sequencer and Taq DNA polymerase as described by the manufacturer (Appligene Oncor, Watford, United Kingdom). DNA cycle sequencing was performed with an ABI PRISM reaction kit (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom) and analyzed with an Applied Biosystems 373A DNA sequencer.

Amplification and cloning of toxin A repeat sequence to generate 14CDTA-HIS and 14CDTA-TETC recombinant proteins.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from C. difficile VPI 10463 using the method of Wren and Tabaqchali (54). A 960-bp DNA fragment encoding 14CDTA (bp 7159 to 8118, inclusive) was amplified by using the following PCR primers which were based on the published toxin A sequence from strain VPI 10463 (13): sense strand 5′-ACTTCTAGAGCCTCAACTGGTTATACAAGT-3′ and anti-sense strand 5′-ATAACTAGTAGGGGCTTTTACTCCATCAAC-3′. Underlining denotes a XbaI restriction site within the sense-strand primer and a SpeI restriction site within the anti-sense-strand primer.

For construction of the 14CDTA-TETC recombinant protein, the amplified toxin A sequence was subcloned into the pTAg cloning vector (R&D Systems Europe, Ltd., Abingdon, United Kingdom), was excised with XbaI-SpeI, and was inserted into SpeI-digested pTECH-1 downstream of the TETC-encoding sequence (27). This construct was named p56TETC. For construction of 14CDTA-HIS recombinant protein, the entire toxin A sequence was first excised from the pTECH-1 vector with SpeI and XbaI and subcloned into XbaI-digested pUC18 (Promega). Clones containing the toxin A fragment in the correct orientation were isolated, and the toxin A sequence was excised with BamHI and HindIII and then inserted into similarly digested pRSET-A to create plasmid p56HIS. All recombinant plasmids were initially transformed into Epicurian coli XL2-blue MRF′ ultracompetent cells (Stratagene, Cambridge, United Kingdom), and the integrity of the cloning junctions was confirmed by Dye Terminator cycle sequencing.

Expression and affinity purification of recombinant toxin A C-terminal repeat proteins.

Plasmid p56TETC was first electroporated into S. typhimurium LB5010 as described (4) and then introduced into rationally attenuated S. typhimurium BRD915 (htrA) via P22 bacteriophage transduction (47). To induce protein expression, recombinant S. typhimurium BRD915 was incubated at 37°C with aeration in LB containing ampicillin until early/mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm, 0.3 to 0.5). The anaerobically-inducible nirB promoter located on the pTECH-1 plasmid was then activated by incubating the culture for a further 24 h without shaking in an anaerobic atmosphere (Mark III work station; Don Whitley Scientific Limited, Shipley, United Kingdom). E. coli BL21 (DE3) transformed with p56HIS was grown in LB containing ampicillin until mid-log phase, and the expression of the plasmid-encoded protein was induced by the addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM and incubating for a further 5 h. After recombinant protein induction, both cultures were harvested and spheroplasts were generated (49). Fractions (10 ml) of the spheroplasts were disrupted with three 50-s bursts of ultrasonic power (Ultrasonic Processor; Jencons Scientific Ltd., Leighton Buzzard, United Kingdom), and the cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 15 min. The soluble fraction was recovered by centrifugation for 30 min at 12,000 × g and was filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size membrane (Millipore).

The recombinant toxin A fragments were purified by Bovine thyroglobulin affinity chromatography with a modification of the method of Krivan and Wilkins (29). In brief, soluble protein harvested as described above was diluted with an equal volume of Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (0.05 M Tris, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.0) and cooled to 4°C. The chilled material was passaged through 4 ml of prechilled Affi-Gel 15 resin (Bio-Rad) which had been coupled to 140 mg of bovine thyroglobulin (Sigma). After four applications of the cellular lysate at 4°C, the column was washed with at least 40 bed volumes of cold TBS, and the bound material was eluted with TBS prewarmed to 37°C. Purified material collected was concentrated with Centriplus 30 centrifugal concentrators (Amicon, Stonehouse, United Kingdom) and stored in aliquots at −70°C.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot.

Proteins were separated by using 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels and the discontinuous buffer system of Laemmli (30). Prior to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis, the protein content of samples was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce & Warriner Ltd., Chester, United Kingdom). Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were transferred to Hybond C nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Life Science Ltd., Amersham, United Kingdom) and processed as described (5). Membranes were probed with either the monoclonal antibody PCG-4 specific for the C-terminal repeat region of toxin A (generously supplied by D. Lyerly, TechLab, Inc.) or a polyclonal rabbit anti-TETC antiserum (14).

Hemagglutination activity of toxin A fragments.

Samples of protein were serially diluted twofold in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) within a 96-well U-bottomed plate (Sterilin), and 25 μl of a 2% (vol/vol) suspension of washed rabbit erythrocytes was added to each well (TCS Microbiology, Botolph Claydon, United Kingdom). Plates were incubated for 18 h at 4°C, and agglutinating activity was determined as the highest dilution of protein able to promote 100% agglutination of erythrocytes. Each assay was performed in duplicate.

Animals and immunization.

Groups of five female BALB/c mice aged 6 to 8 weeks (Harlan Olac, Bicester, United Kingdom) were immunized intranasally (i.n.) with combinations of either 10 μg of 14CDTA-HIS or 14CDTA-TETC, 5 μg of TETC, and 1 μg of E. coli LT or LTR72. Each inoculum was diluted to a final volume of 30 μl in PBS (pH 7.2), and 15 μl was administered to each nostril of lightly anesthetized animals (Halothane, Rhone Merieux, France). Mice were immunized with three identical doses administered on days 0, 20, and 35. Serum samples were collected from the tail vein of each animal 1 day prior to immunization. All mice were exsanguinated on day 47 by cardiac puncture, and nasal, lung, and intestinal lavage was carried out with 0.1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin in PBS as described (12). For intestinal lavage, all samples were stored with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom) to inhibit intestinal proteases.

ELISA.

Anti-toxin A and anti-TT antibody responses within individual serum samples were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). These assays were performed as described (10), with ELISA wells coated overnight at 4°C with either purified whole toxin A (0.15 μg/well in 0.1 M NaHCO3, pH 9.5) or formalin-inactivated TT (0.5 μg/well in PBS, pH 7.2). ELISA titers were determined as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution which gave an absorbance value of 0.5 U above the background for toxin A and 0.3 U above the background for TT. All titers were standardized against either monoclonal antibody PCG-4 or rabbit polyclonal anti-TETC positive control antiserum (14).

Measurement of anti-toxin antibody levels in mucosal secretions.

The levels of both anti-toxin A and anti-TT-specific IgA within the mucosal lavage samples were determined by ELISA as previously described (12), with toxin A at a concentration of 0.15 μg/well. ELISA titers were calculated as the reciprocal of the highest dilution which gave an absorbance 0.2 U above the background.

Antibody-mediated toxin A neutralization.

The toxin-A-neutralizing properties of both antiserum and mucosal lavage samples were determined by using CHO-K1 cells and affinity-purified toxin A. In brief, CHO-K1 cells (passage number 28-38) were grown in Ham’s F-12 medium (Sigma) containing 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum and 1 mM l-glutamine and supplemented with streptomycin-neomycin-penicillin (Sigma). Freshly trypsinized CHO-K1 cells were seeded into 96-well trays (Corning Costar) at 3 × 104 cells per well and allowed to recover for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The test sample was serially diluted twofold in growth medium and allowed to react with toxin A (final concentration, 0.6 μg/ml) for 90 min at 37°C. The toxin A-antiserum mixtures were then added to the CHO-K1 cells to give a final total volume of 100 μl for antiserum or 125 μl for lung lavage, and the cellular morphology was noted after a 24-h incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2. The neutralizing titer was taken as the highest dilution of sample to prevent 100% cellular rounding. All samples were tested in duplicate, and individual assays were standardized against a positive-control rabbit antiserum which had been raised against a conserved decapeptide located within the C-terminal region of toxin A (53).

Statistical analysis.

Unpaired Student’s t test was used to compare unrelated groups of data. If the standard deviations (SDs) were found to be significantly different, the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was used to determine the statistical relatedness of the data groups. P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was carried out with the InStat statistical software package (Sigma).

RESULTS

Expression and affinity purification of recombinant 14CDTA proteins.

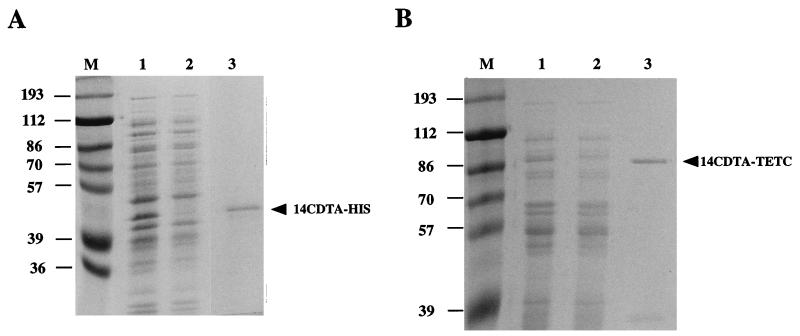

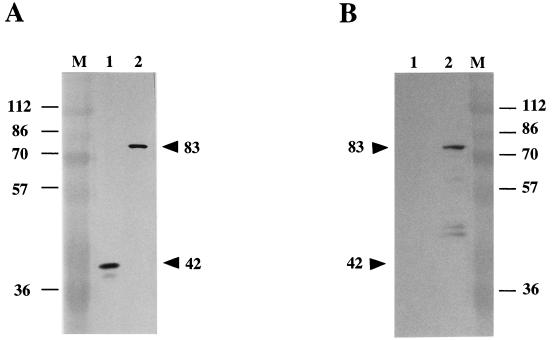

SDS-PAGE analysis of cellular lysates expressing 14CDTA-HIS revealed an additional recombinant protein with a mean apparent molecular mass of 42 kDa (calculated from three separate gels), which corresponded to the toxin A-polyhistidine fusion (Fig. 1A, lane 1). Similar analysis of recombinant cells expressing 14CDTA-TETC showed an additional protein band with a mean apparent molecular mass of 83 kDa which corresponded to the toxin A-fragment C fusion protein (Fig. 1B, lane 1). Both 14CDTA-HIS and 14CDTA-TETC fusion proteins were successfully purified by bovine thyroglobulin affinity chromatography. SDS-PAGE analysis showed purified 14CDTA-HIS (Fig. 1A, lane 3) and 14CDTA-TETC (Fig. 1B, lane 3) to be relatively free of other bacterial proteins. Immunoblot analysis showed both proteins to be immunoreactive with monoclonal antibody PCG-4, which is specific for the toxin A repeat region (Fig. 2A). The 14CDTA-HIS purified material also appeared to contain low levels of an immunoreactive 41-kDa protein. This protein also reacted with a monoclonal antibody specific for the polyhistidine tag attached to the N terminus of the toxin A repeats, indicating that limited proteolytic degradation had occurred at the C terminus of the 42-kDa protein (data not shown). Anti-TETC serum reacted in immunoblotting with an 83-kDa immunoreactive band which corresponded to the 14CDTA-TETC protein (Fig. 2B). In addition, several other immunoreactive bands of lower molecular weight were also present at low levels. As these bands did not react with the PCG-4 monoclonal antibody, limited proteolysis of TETC appeared to have occurred.

FIG. 1.

Thyroglobulin affinity-purified 14CDTA-HIS (A) and 14CDTA-TETC (B) in SDS–10% PAGE gels stained with Coomassie blue. Lanes 1, cell lysates before affinity column; lanes 2, cell lysates after affinity column; lanes 3, purified protein collected from column (approximately 3 μg); lanes M, prestained molecular weight markers (apparent molecular masses are shown in kilodaltons).

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot of affinity-purified 14CDTA-HIS (lanes 1) and 14CDTA-TETC (lanes 2) against the toxin A-specific monoclonal antibody PCG-4 (A) or anti-TT polyclonal antiserum (B). Lanes M, molecular weight markers (apparent molecular masses are shown in kilodaltons).

Hemagglutination and cytotoxic properties of the 14CDTA.

As the attachment of either the polyhistidine tag or TETC to the N terminus of 14CDTA could compromise the ability of the repeats to bind to known toxin A receptors, the binding of both recombinant proteins to the Galα1-3Galβ1-4GlcNac trisaccharide toxin A receptor found on the surface of rabbit erythrocytes was determined (28). Although there was no significant difference in the amounts of 14CDTA-HIS and 14CDTA-TETC required to bind to the erythrocyte surface and promote 100% hemagglutination (P > 0.05), both recombinant proteins failed to agglutinate the erythrocytes as effectively as whole toxin A (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of the minimum amounts of purified 14CDTA proteins required to promote 100% agglutination of rabbit erythrocytes

| Protein preparation | Amt of protein (in pmols) required to promote 100% hemagglutination of 2% (vol/vol) rabbit erythrocytesa |

|---|---|

| 14CDTA-HIS | 3.61 ± 2.77 |

| 14CDTA-TETC | 5.28 ± 1.74 |

| Toxin A | 0.05 ± 0.002 |

| TT | No hemagglutinationb |

Values shown represent means ± standard errors of the means from three separate experiments, each performed in duplicate with protein taken from three different batches of purified protein.

10 pmol tested.

Both 14CDTA-HIS and 14CDTA-TETC were shown to possess no cytotoxic activity against monolayers of CHO-K1 cells, even when 10 pmol of purified protein was tested (data not shown). In contrast, 0.2 pmol of whole toxin A induced 100% cytotoxicity.

Anti-toxin A responses in mice immunized i.n. with toxin A repeat proteins.

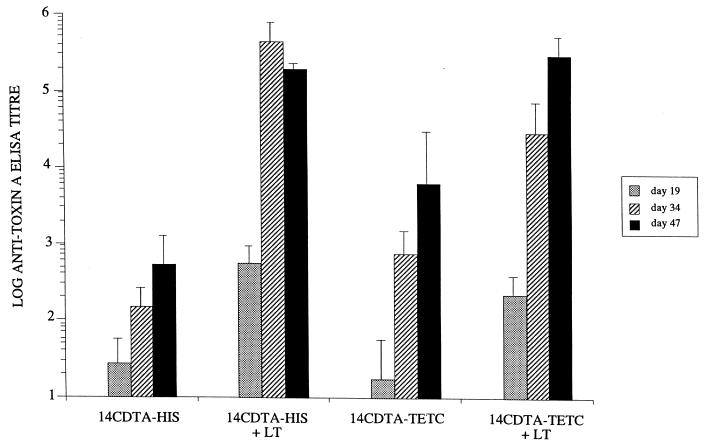

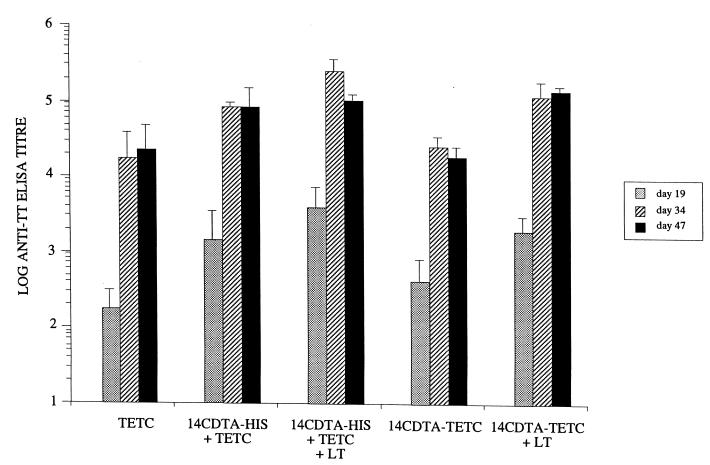

Mice were immunized i.n. with three doses of either 14CDTA-HIS or 14CDTA-TETC affinity-purified protein as described, with or without LT as a mucosal adjuvant. ELISA analysis of serum samples taken after one, two, and three doses showed the 14CDTA-HIS protein to be weakly immunogenic, inducing detectable anti-toxin A antibody responses even after a single dose (Fig. 3). These antibody levels were boosted with subsequent doses and were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than the background titers seen in control mice immunized with TETC alone after three doses (data not shown). The coadministration of LT with 14CDTA-HIS resulted in very impressive responses, with mean anti-toxin A titers over 4,000-fold greater than those generated by recombinant protein alone (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). The genetic coupling of TETC to the toxin A repeats (14CDTA-TETC) was also shown to increase anti-toxin A responses, raising the mean anti-toxin A titer approximately eightfold when compared to 14CDTA-HIS alone after three doses (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). The addition of LT to 14CDTA-TETC again dramatically increased the anti-toxin A titers. The increased responses were not due to nonspecific cross-reactivity between LT and toxin A epitopes, as control serum samples containing high titers of LT-specific antibody did not react with toxin A in ELISA (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Mean anti-toxin A total Ig responses in the serum of i.n. immunized BALB/c mice. Antibody titers were measured by ELISA in serum taken after one dose (day 19), two doses (day 34), and three doses (day 47) of antigen. Mean titers are shown ± SDs from five mice. Individual preimmune titers have been subtracted from the calculated titer of each corresponding mouse.

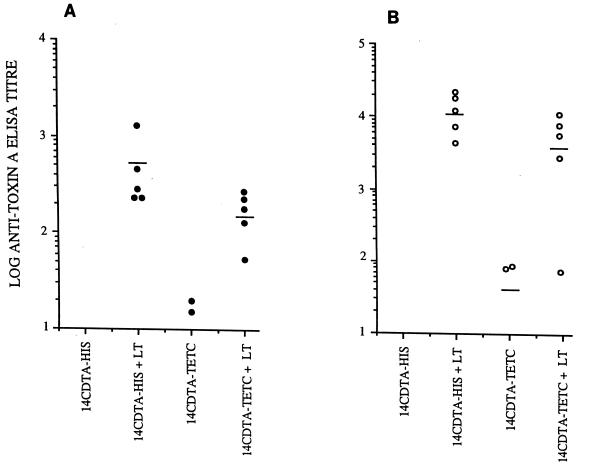

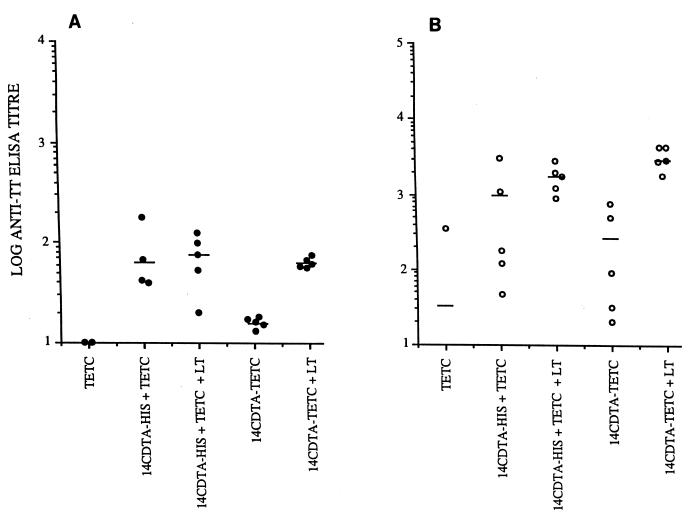

Anti-toxin A mucosal IgA responses after immunization with toxin A repeat proteins.

When coadministered with LT, both 14CDTA-HIS and -TETC generated high levels of toxin A-specific IgA at the pulmonary and nasal mucosal surfaces in all mice (Fig. 4). The responses seen were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than those found in mice which did not receive LT, although some mice immunized with 14CDTA-TETC alone did induce significant mucosal IgA responses.

FIG. 4.

Mucosal toxin A-specific IgA responses generated by three i.n. doses of antigen in nasal (A) and pulmonary (B) lavage samples. Responses show the variation in the immune responses between individual mice within each group. Bars represent mean antibody titers.

Lavage samples were also taken from the small intestines of all immunized mice, and the level of toxin A-specific IgA was determined as above. Even in the presence of LT, both 14CDTA-HIS and 14CDTA-TETC did not generate significant levels of toxin-specific IgA at this distal mucosal surface (data not shown).

Toxin A neutralization with serum and mucosal antibodies harvested from i.n. immunized mice.

Toxin A exhibits a cytotoxic effect on CHO-K1 cells in vitro which can be neutralized by specific antibodies (24, 53). Serum harvested from all five mice immunized with 14CDTA-HIS plus LT exhibited significant neutralizing activity, while four of the five mice immunized with 14CDTA-TETC plus LT produced toxin-neutralizing responses (Table 2). In contrast, the levels of toxin A-specific antibody in serum harvested from mice immunized with antigen alone were generally too low to consistently neutralize toxin A (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Toxin A-neutralizing properties of serum and mucosal antibodies harvested after three i.n. doses of antigena

| Immunogen | Serum

|

Lung washb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxin A neutralization titer | Responders/total mice tested | Toxin A neutralization titer | Responders/total mice tested | |

| 14CDTA-HIS | 0 | 0/5 | 0 | 0/5 |

| 14CDTA-TETC | 1 ± 2 | 1/5 | 0 | 0/5 |

| 14CDTA-HIS + LT | 51 ± 17 | 5/5 | 2.4 ± 3.6 | 2/5 |

| 14CDTA-TETC + LT | 17 ± 15 | 4/5 | 0.4 ± 0.84 | 1/5 |

| TETC | 0 | 0/5 | 0 | 0/5 |

Toxin-neutralizing titers were scored as the highest dilution of antiserum or mucosal lavage to promote 100% neutralization of toxin A (60 ng/well) as measured against CHO-K1 cells in vitro. Mean neutralizing titers ± SDs for five mice are shown, with each assay being performed in duplicate.

Four times the amount of serum sample (100 μl) was tested.

Since lung lavage samples had been shown to contain high levels of toxin A-specific IgA by ELISA, these samples were also tested for neutralizing activity. Although the level of neutralization was lower than that seen with the corresponding serum samples, single mice from the 14CDTA-TETC-plus-LT-immunized group did generate sufficient levels of toxin-neutralizing IgA at the lung mucosa (Table 2). The highest mean neutralization titer was seen with lavage samples taken from 14CDTA-HIS-plus-LT-immunized mice, with two of five samples possessing toxin A-neutralizing activity.

Anti-tetanus serum responses in mice immunized i.n. with toxin A repeat proteins.

In addition to anti-toxin A responses, anti-TT serum antibody levels were also determined. High titers of anti-TT-specific antibody were generated with either 14CDTA-TETC or 14CDTA-HIS plus TETC coadministered with LT (Fig. 5). These responses were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than those generated by the antigens alone. The addition of 14CDTA-HIS to TETC also produced mean anti-TT titers which were approximately fourfold higher after both two and three doses than those seen in control mice immunized with TETC alone (Fig. 5). LT-specific antibodies did not cross-react with TT in ELISA (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Mean anti-TT total Ig responses in the serum of i.n. immunized BALB/c mice. Antibody titers were measured by ELISA in serum taken after one dose (day 19), two doses (day 34), and three doses (day 47) of antigen. Mean titers are shown ± SDs from five mice. Individual preimmune titers have been subtracted from the calculated titer of each corresponding mouse.

Anti-TT IgA responses in mice immunized i.n. with toxin A repeat proteins.

Similar to the serum responses, mice coadministered LT in conjunction with either 14CDTA-TETC or 14CDTA-HIS plus TETC induced very strong anti-TT responses in the nose and lungs (Fig. 6). These titers were consistent between individuals within the group of five mice. Interestingly, both nose and lung lavage samples taken from mice immunized with 14CDTA-HIS plus TETC were also shown to contain very high levels of anti-TT-specific IgA (Fig. 6). These mean antibody titers were higher than those obtained with TETC alone in both nasal washes (P < 0.05) and lung washes (P = 0.05). Although the spread of the response was much greater between individual mice immunized with 14CDTA-HIS plus TETC, the mean response of the group was not significantly (P > 0.05) different from the mice coimmunized with LT adjuvant.

FIG. 6.

Mucosal TT-specific IgA responses generated by three i.n. doses of antigen in nasal (A) and pulmonary (B) lavage. Responses show the variation in the immune responses between individual mice in each group. Bars represent mean antibody titers.

Systemic and local anti-toxin A immune responses in mice immunized i.n. with 14CDTA-TETC and LTR72 adjuvant.

The immunogenicity of the 14CDTA recombinant proteins was shown to be significantly enhanced in the presence of LT. However, as LT is highly toxic to cells, the mucosal adjuvant activity of LTR72, a recombinant derivative of LT with much-reduced toxicity, was determined when administered with the toxin A repeats. Mice were coimmunized with 14CDTA-TETC and LTR72, and the resulting systemic and mucosal antibody responses were compared. After three doses of 14CDTA-TETC plus LTR72, high levels of serum anti-toxin A antibody, comparable (P > 0.05) to those found in control mice immunized with 14CDTA-TETC plus native LT, were seen (Table 3). Similarly, high levels of toxin A-specific IgA were also found on the nasal and pulmonary mucosa from mice immunized with 14CDTA-TETC plus LTR72. These local responses were not significantly different (P > 0.05) to those seen in mice coimmunized with native LT (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Mean toxin A-specific serum and mucosal antibody titers as measured by ELISAa

| Immunogen | Serum | Lung wash | Nasal wash |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14CDTA-TETC | 5,405 ± 3,793 | 48 ± 45 | 3 ± 4 |

| 14CDTA-TETC + LT | 43,785 ± 34,904 | 1,275 ± 1,555 | 86 ± 71 |

| 14CDTA-TETC + LTR72 | 40,724 ± 17,285 | 853 ± 711 | 40 ± 19 |

Samples were taken after three i.n. doses (day 47) of 14CDTA-TETC given with or without LTR72 adjuvant. For serum, specific total Ig levels are shown, while specific IgA titers were measured in lung and nasal lavage samples. Mean titers ± SDs are shown for five mice per group.

DISCUSSION

We have previously shown that 14CDTA of toxin A is immunogenic when expressed as a fusion to TETC and presented to the mucosal immune system within an attenuated S. typhimurium vaccine strain (48). In this study, we have further characterized the immunogenicity of this repeat region with two pure proteins. The recombinant proteins were purified either with (14CDTA-TETC) or without (14CDTA-HIS) TETC fused to the N terminus of the toxin A repeats. The results show both 14CDTA-HIS and -TETC to be immunogenic when given i.n. to mice. However, much higher systemic and local specific antibody responses were induced when the proteins were coadministered with LT. Importantly, the mucosal and systemic antibodies generated were able to neutralize the cytotoxic effects of whole toxin A. To our knowledge, this is the first time that purified fragments of the toxin A binding domain have been shown to be immunogenic at the nasal mucosa.

For successful mucosal immunization, an additional adjuvant, such as LT or cholera toxin, is often required to break immunological nonresponsiveness (36, 44). Within this study, both the 14CDTA-HIS and -TETC fusion proteins induced high anti-toxin A serum responses when given in conjunction with LT. The 14CDTA-HIS-plus-LT preparation was more proficient at stimulating anti-toxin A antibody than was 14CDTA-TET plus LT. Both LT and TETC have been shown to bind to GM1 ganglioside (7, 43). Therefore, the reduced antibody responses seen with 14CDTA-TETC plus LT could be due to competition for the same cellular receptor, altering protein uptake and interfering with the immunogenicity of LT. Alternatively, it is possible that the genetic coupling of TETC could induce conformational changes within the toxin A repeats, possibly masking or destroying toxin A epitopes. However, if structural changes occurred, they were not sufficient to alter the ability of the repeats to bind to a known toxin A receptor, as both 14CDTA fusion proteins were equally efficient at promoting agglutination of rabbit erythrocytes. Indeed, the pTECH-1 plasmid used to express the 14CDTA-TETC fusion protein was designed to introduce a G-P-G-P spacer sequence between TETC and the downstream guest protein. This sequence allows greater flexibility between the two proteins and is believed to promote optimal folding of both fusion protein components (27).

In the absence of LT, 14CDTA-TETC induced higher anti-toxin A responses than 14CDTA-HIS. TETC is a highly immunogenic protein (14) and has been used as a carrier protein for several guest antigens expressed within attenuated Salmonella vaccine strains (3, 27). Without LT being present, it is possible that the costimulatory activity of TETC could be realized, possibly as a result of a lack of competition for cellular receptors with LT.

Several studies have evaluated the immunological potential of various C. difficile toxin-based test vaccines, but the local immune responses were neglected in the majority of cases (33, 45). As it is highly likely that mucosal immunity will play an important role in protecting against toxin-induced mucosal damage, local immune responses were also characterized in this study. Similar to the serum responses, both 14CDTA-HIS and -TETC induced high levels of anti-toxin A-specific mucosal IgA when given with LT. These responses were highest at the pulmonary surface. Within rodents, the induction of antibody responses following i.n. immunization is known to involve the aggregates of nasal-associated lymphoid tissue located at the base of the nasal cavity (17). However, it is likely that the bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue will also play a role, as i.n. administered material is also found within the lung (21). This could explain the strong IgA responses seen within the lung aspirates. Intestinal lavage samples were also harvested in this study but did not contain significant levels of anti-toxin IgA as measured by this system (data not shown). This inability to detect significant levels of specific IgA at mucosal sites distal to the site of induction has been shown by others (11) and could be explained by a compartmentalization of the various inductive and effector sites which comprise the mucosal-associated lymphoid system.

A genetically modified LT variant, designated LTR72, has been shown to be well tolerated in vivo due to a much-reduced toxicity and to behave as a potent mucosal adjuvant (19). It is perceived that LTR72 will be tested as a potential mucosal adjuvant in human clinical trials. In this study, both the systemic and mucosal immunogenicity of the 14CDTA-TETC protein was shown to be significantly enhanced when coadministered with LTR72. Indeed, LTR72 appeared to be as potent an adjuvant as native LT at the 1-μg dose when given i.n.

In addition to anti-toxin A responses, both serum and lavage samples were tested for anti-TT antibody. The administration of 14CDTA-HIS with TETC generated antibody responses which were approximately fourfold larger than those seen with TETC alone. This suggests that the 14CDTA may be able to enhance the serum immune response against guest antigens. Analysis of the anti-TT mucosal IgA responses showed the toxin A repeats to exert a greater immunomodulatory effect at the mucosa, especially when the proteins were admixed rather than presented as a genetic fusion. The mucosal adjuvant activity of several bacterial toxins appears to be dependent on a successful specific toxin-receptor interaction (8). It is possible that the increased levels of anti-TT mucosal IgA induced by TETC when admixed with 14CDTA-HIS may result from the toxin A repeats binding to specific receptors on the mucosal surface and providing an adjuvant effect. We have tentative evidence for the presence of toxin A receptors within the murine upper respiratory tract. Experiments have shown very small amounts (500 ng) of i.n. administered native toxin A to be lethal. Autopsy revealed extensive hemorrhage within the mucosa of the upper lung (data not shown), indicating a potential localization of toxin within this tissue. The F9 murine cell line has also been shown to possess a high density of toxin A cell surface receptors (46), demonstrating the ability of mouse tissue to express toxin A receptors.

Several studies have shown the important roles that serum and mucosal toxin-neutralizing antibodies play in protecting against toxin A-mediated disease (22, 50). Indeed, elevated levels of systemic neutralizing antibody have been correlated to protection from whole-organism challenge in vivo (18, 45). Within this study, both serum and mucosal aspirates were shown to possess toxin-neutralizing activity. The highest neutralization responses were seen with serum taken from mice immunized with 14CDTA-HIS and LT. In addition, lung lavage samples taken from these immunized animals were able to neutralize toxin A, but the titers were much lower than those seen with serum, and not all of the samples were neutralizing. This is probably due to the high dilution factor associated with lavage samples compared with serum. However, the data from this proof-of-principle study does show that mucosal IgA raised against a nontoxic fragment of the toxin A binding domain is capable of neutralizing the cytotoxic action of whole toxin A. Further studies are needed to develop a system to induce these desirable neutralizing IgA responses at the intestinal mucosa, the site of toxin A-mediated damage.

Systemic toxin-neutralizing antibody responses have been successfully induced in hamsters after i.n. immunization with formalin-inactivated whole toxoid A and B vaccines (18, 45). Our study has shown that even a small fragment of the toxin A binding domain is capable of inducing both systemic and local neutralizing responses when applied directly to the nasal mucosa along with LT adjuvant. Due to these properties, we believe the 14CDTA repeat protein to be an ideal choice as one component of a recombinant C. difficile vaccine. In addition, high levels of anti-TT antibody were also generated when the 14CDTA-TETC fusion was coadministered with LTR72 mucosal adjuvant. As TETC is an antitetanus vaccine candidate, the exciting possibility of a human mucosal vaccine directed against two clostridial pathogens appears feasible.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David Lyerly for the kind gifts of purified toxin A and monoclonal antibody PCG-4. Native LT and LTR72 were kind gifts from Mariagrazia Pizza. We also thank Lynne Batty for her technical assistance.

S.J.W. was supported by the Welcome Trust, grant number 042686/Z/94. G. Douce was supported by a Wellcome Trust program grant to G. Dougan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barroso L A, Wang S Z, Phelps C J, Johnson J L, Wilkins T D. Nucleotide sequence of Clostridium difficile toxin B gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4004. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.13.4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cartmill T D I, Panigrahi H, Worsley M A, McCann D C, Nice C N, Keith E. Management and control of a large outbreak of diarrhoea due to Clostridium difficile. J Hosp Infect. 1994;27:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chabalgoity J A, Khan C M, Nash A A, Hormaeche C E. A Salmonella typhimurium htrA live vaccine expressing multiple copies of a peptide comprising amino acids 8-23 of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D as a genetic fusion to tetanus toxin fragment C protects mice from herpes simplex virus infection. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:791–801. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.426965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatfield S N, Fairweather N, Charles I, Pickard D, Levine M, Hone D, Posada M, Strugnell R A, Dougan G. Construction of a genetically defined Salmonella typhi Ty2 aroA, aroC mutant for the engineering of a candidate oral typhoid-tetanus vaccine. Vaccine. 1992;10:53–60. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90420-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christodoulides M, McGuiness B T, Heckels J E. Immunisation with synthetic peptides containing epitopes of the class 1 outer membrane protein of Neisseria meningitidis: production of bactericidal antibodies on immunisation with a cyclic peptide. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1729–1738. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-8-1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clements J D, Hartzog N M, Lyon F L. Adjuvant activity of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin and effect on the induction of oral tolerance in mice to unrelated protein antigens. Vaccine. 1988;6:269–277. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(88)90223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Critchley D R, Habig W H, Fishman P H. Reevaluation of the role of gangliosides as receptors for tetanus toxin. J Neurochem. 1986;47:213–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb02852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cropley I, Douce G, Roberts M, Chatfield S, Pizza M, Marsili I, Rappuoli R, Dougan G. Mucosal and systemic immunogenicity of a recombinant, non-ADP-ribosylating pertussis toxin: effects of formaldehyde treatment. Vaccine. 1995;13:1643–1648. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00134-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dillon S T, Rubin E J, Yakubovich M, Pothoulakis C, LaMont J T, Feig L A, Gilbert R J. Involvement of Ras-related Rho proteins in the mechanisms of action of Clostridium difficile toxin A and toxin B. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1421–1426. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1421-1426.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douce G, Fontana M, Pizza M, Rappuoli R, Dougan G. Intranasal immunogenicity and adjuvanticity of site-directed mutant derivatives of cholera toxin. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2821–2828. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2821-2828.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douce G, Giuliani M M, Giannelli V, Pizza M, Rappuoli R, Dougan G. Mucosal immunogenicity of genetically detoxified derivatives of heat labile toxin from Escherichia coli. Vaccine. 1998;16:1065–1073. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)80100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douce G, Turcotte C, Cropley I, Roberts M, Pizza M, Domenghini M, Rappuoli R, Dougan G. Mutants of Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin lacking ADP-ribosyltransferase activity act as nontoxic, mucosal adjuvants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1644–1648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dove C H, Wang S Z, Price S B, Phelps C J, Lyerly D M, Wilkins T D, Johnson J L. Molecular characterization of the Clostridium difficile toxin A gene. Infect Immun. 1990;58:480–488. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.2.480-488.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fairweather N F, Lyness V A, Maskell D J. Immunization of mice against tetanus with fragments of tetanus toxin synthesized in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2541–2545. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2541-2545.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fekety R, Silva J, Kauffman C, Buggy B, Gunner H, Deery H. Treatment of antibiotic-associated Clostridium difficile colitis with oral vancomycin: comparison of two dosage regimens. Am J Med. 1989;86:15–19. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George R H, Symonds J M, Dimock F, Brown J D, Arabi Y, Shinagawa N, Keighley M R B, Alexander Williams J, Burdon D W. Identification of Clostridium difficile as a cause of pseudomembranous colitis. Br Med J. 1978;1:695. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6114.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giannasca P J, Boden J A, Monath T P. Targeted delivery of antigen to hamster nasal lymphoid tissue with M cell-directed lectins. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4288–4298. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4288-4298.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giannasca P J, Zhang Z-X, Lei W-D, Boden J A, Giel M A, Monath T P, Thomas J W D. Serum antitoxin antibodies mediate systemic and mucosal protection from Clostridium difficile disease in hamsters. Infect Immun. 1999;67:527–538. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.527-538.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giuliani M M, Del Giudice G, Giannelli V, Dougan G, Douce G, Rappuoli R, Pizza M. Mucosal adjuvanticity and immunogenicity of LTR72, a novel mutant of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin with partial knockout of ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heard S R, O’Farrell S, Holland D, Crook S, Barnett M J, Tabaqchali S. The epidemiology of Clostridium difficile with use of a typing scheme: nosocomial acquisition and cross-infection among immunocompromised patients. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:159–162. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopkins S, Kraehenbuhl J P, Schodel F, Potts A, Peterson D, De Grandi P, Nardelli-Haefliger D. A recombinant Salmonella typhimurium vaccine induces local immunity by four different routes of immunization. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3279–3286. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3279-3286.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson S, Sypura W D, Gerding D N, Ewing S L, Janoff E N. Selective neutralization of a bacterial enterotoxin by serum immunoglobulin A in response to mucosal disease. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3166–3173. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3166-3173.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Just I, Selzer J, Wilm M, von Eichel-Streiber C, Mann M, Aktories K. Glucosylation of Rho proteins by Clostridium difficile toxin B. Nature. 1995;375:500–503. doi: 10.1038/375500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katoh T, Higaki M, Honda T, Miwatani T. Cytotonic effect of Clostridium difficile enterotoxin on Chinese hamster ovary cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1986;34:241–244. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly C P, Pothoulakis C, Orellana J, LaMont J T. Human colonic aspirates containing immunoglobulin A antibody to Clostridium difficile toxin A inhibit toxin A-receptor binding. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:35–40. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91781-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ketley J M, Mitchell T J, Candy D C, Burdon D W, Stephen J. The effects of Clostridium difficile crude toxins and toxin A on ileal and colonic loops in immune and non-immune rabbits. J Med Microbiol. 1987;24:41–52. doi: 10.1099/00222615-24-1-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan C M, Villarreal-Ramos B, Pierce R J, Riveau G, Demarco de Hormaeche R, McNeill H, Ali T, Fairweather N, Chatfield S, Capron A, Dougan G, Hormaeche C E. Construction, expression, and immunogenicity of the Schistosoma mansoni P28 glutathione S-transferase as a genetic fusion to tetanus toxin fragment C in a live Aro attenuated vaccine strain of Salmonella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11261–11265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krivan H C, Clark G F, Smith D F, Wilkins T D. Cell surface binding site for Clostridium difficile enterotoxin: evidence for a glycoconjugate containing the sequence Galα1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAc. Infect Immun. 1986;53:573–581. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.3.573-581.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krivan H C, Wilkins T D. Purification of Clostridium difficile toxin A by affinity chromatography on immobilized thyroglobulin. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1873–1877. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.8.1873-1877.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larson H E, Borriello S P. Quantitative study of antibiotic-induced susceptibility to Clostridium difficile enterocecitis in hamsters. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1348–1353. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.7.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larson H E, Price A B, Honour P, Borriello S P. Clostridium difficile and the aetiology of pseudomembranous colitis. Lancet. 1978;1:1063–1066. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90912-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lyerly D M, Johnson J L, Frey S M, Wilkins T D. Vaccination against lethal Clostridium difficile enterocolitis with a nontoxic recombinant peptide of toxin A. Curr Microbiol. 1990;21:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyerly D M, Krivan H C, Wilkins T D. Clostridium difficile: its disease and toxins. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1988;1:1–18. doi: 10.1128/cmr.1.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyerly D M, Saum K E, MacDonald D K, Wilkins T D. Effects of Clostridium difficile toxins given intragastrically to animals. Infect Immun. 1985;47:349–352. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.2.349-352.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGhee J R, Mestecky J, Dertzbaugh M T, Eldridge J H, Hirasawa M, Kiyono H. The mucosal immune system: from fundamental concepts to vaccine development. Vaccine. 1992;10:75–88. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90021-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell T J, Ketley J M, Burdon D W, Candy D C, Stephen J. The effects of Clostridium difficile crude toxins and purified toxin A on stripped rabbit ileal mucosa in Ussing chambers. J Med Microbiol. 1987;23:199–204. doi: 10.1099/00222615-23-3-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moellering R C J. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1196–1199. doi: 10.1086/520283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pierce P F, Wilson R, Silva J. Antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis: an epidemic investigation of a cluster of cases. J Infect Dis. 1982;145:269–274. doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price S B, Phelps C J, Wilkins T D, Johnson J L. Cloning of the carbohydrate-binding portion of the toxin A gene of Clostridium difficile. Curr Microbiol. 1987;16:82–86. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simor A E, Yake S L, Tsimidis K. Infection due to Clostridium difficile among elderly residents of a long-term care facility. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:672–678. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.4.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith J A, Cooke D L, Hyde S, Borriello S P, Long R G. Clostridium difficile toxin A binding to human intestinal epithelial cells. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:953–958. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-11-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spangler B D. Structure and function of cholera toxin and related Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:622–647. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.4.622-647.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Staats H F, Jackson R J, Marinaro M, Takahashi I, Kiyono H, McGhee J R. Mucosal immunity to infection with implications for vaccine development. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:572–583. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torres J F, Lyerly D M, Hill J E, Monath T P. Evaluation of formalin-inactivated Clostridium difficile vaccines administered by parenteral and mucosal routes of immunization in hamsters. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4619–4627. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4619-4627.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tucker K D, Carrig P E, Wilkins T D. Toxin A of Clostridium difficile is a potent cytotoxin. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:869–871. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.5.869-871.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turner S J, Carbone F R, Strugnell R A. Salmonella typhimurium aroA aroD mutants expressing a foreign recombinant protein induce specific major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes in mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5374–5380. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5374-5380.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ward S J, Douce G, Figueiredo D, Dougan G, Wren B W. Immunogenicity of a Salmonella typhimurium aroA aroD vaccine expressing a nontoxic domain of Clostridium difficile toxin A. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2145–2152. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2145-2152.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ward S J, Scopes D, Christodoulides M, Clarke I N, Heckels J E. Expression of Neisseria meningitidis class 1 porin as a fusion protein in Escherichia coli: the influence of liposomes and adjuvants on the production of a bactericidal immune response. Microb Pathog. 1996;21:499–512. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Warny M, Vaerman J P, Avesani V, Delmee M. Human antibody response to Clostridium difficile toxin A in relation to clinical course of infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:384–389. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.384-389.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilcox M H. Treatment of Clostridium difficile infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:41–46. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.suppl_3.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilcox M H, Spencer R C. Clostridium difficile infection: responses, relapses and re-infections. J Hosp Infect. 1992;22:85–92. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(92)90092-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wren B W, Russell R R, Tabaqchali S. Antigenic cross-reactivity and functional inhibition by antibodies to Clostridium difficile toxin A, Streptococcus mutans glucan-binding protein, and a synthetic peptide. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3151–3155. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3151-3155.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wren B W, Tabaqchali S. Restriction endonuclease DNA analysis of Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:2402–2404. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.12.2402-2404.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]