Abstract

Information provided by experts is believed to play a key role in shaping attitudes towards policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. This paper uses a survey experiment to assess whether providing citizens with expert information about the health risk of COVID-19 and the economic costs of lockdown measures affects their attitudes towards these policies. Our findings show that providing respondents with information about COVID-19 fatalities among the elderly raises support for lockdown measures, while information about their economic costs decreases support. However, different population subgroups react differently. Men and younger respondents react more sensitively to information about lockdown costs, while women and older respondents are more susceptible towards information regarding fatality rates. Strikingly, our results are entirely driven by respondents who underestimate the fatality of COVID-19, who represent a majority.

Keywords: Corona, COVID-19, Pandemic, Lockdown, Survey experiment, Germany

1. Introduction

To contain the spread of the coronavirus, governments worldwide took measures that severely curtail economic and social life. These include contact restrictions, curfews, as well as the temporary closure of certain businesses. Arguably, the success of these policies critically depends on support from the public. A lack of support may not only reduce compliance with the containment measures, but also the governments’ ability to uphold them. In the debate about policy responses to the crisis, information provided by experts, in particular scientists, is widely seen to play an important role in shaping attitudes of the population.

This paper investigates whether information provision really affects what citizens think about key aspects of the crisis management and how reactions differ across different groups. We study whether providing people with information about (i) the fatality rates of COVID-19 (i.e., the share of persons with a positive Corona test who died) and (ii) the economic costs associated with the containment measures, causally affects their attitudes towards these measures. To this end, we designed a survey including an information experiment.

The survey was conducted in Germany in June 2020 and it comprises roughly 30,000 representatively selected German citizens. For the information experiment, the interviewees were randomly assigned to eight different groups and each group was ‘treated’ with different information. The information we provided encompassed potential economic costs caused by the containment measures, as well as the fatality rates among all infected persons and among those younger or older than 70 years. After receiving the information, respondents were asked what they think about the containment measures implemented in March, as well as the relaxation of these measures in May.

Our findings suggest that respondents’ attitudes towards the containment measures are significantly affected by information about the fatality of the coronavirus among the elderly. Respondents were informed that during the first months of the pandemic, an average of 210 out of 1000 persons older than 70 years registered as being infected with the coronavirus died. Respondents receiving this information tend to show greater support for stricter lockdown measures and greater opposition against relaxing these measures. In contrast, we do not find significant average treatment effects for treatments involving information about the coronavirus’ fatality in the entire population or among persons younger than 70 years.

Closer inspection suggests that this is linked to respondents’ prior beliefs about the fatality of COVID-19. Most respondents underestimate the fatality rate among the elderly. The median respondent believes that only seven persons older than 70 years die from COVID-19, while the actual number is 210. While the share of respondents underestimating the fatality rate in the entire population as well as among persons younger than 70 years is also large (88 per cent and 74 per cent, respectively), discrepancies between believed and actual fatality rates are smaller on average. If we restrict our analysis to respondents who underestimate the corresponding fatality rate and estimate treatment effects for the treated, we also find significant effects for the treatments involving information about the coronavirus’ fatality in the entire population and among persons younger than 70 years, albeit of smaller magnitude. Arguably, this is because the corresponding fatality rates are notably smaller. In the entire population, 46 out of 1000 persons registered as infected died, whereas the number of deaths per 1000 infected persons among persons younger than 70 years was eight. What is more, providing respondents with information about the economic costs associated with containment measures weakens their support for them.

While the average reactions among the population to the information treatment are intuitive, different population subgroups respond very differently and sometimes quite surprisingly. Firstly, we find that respondents who economically suffered from the Corona crisis are less responsive to information about the fatality of the coronavirus, but more responsive to information about the economic costs. The same is true for respondents who are younger than 70 years as well as male respondents. In other words, respondents scarcely affected (economically) by the Corona crisis, older respondents, and female respondents are more susceptible to information about fatality rate among the elderly but react less sensitively to information about economic repercussions ensuing from the Corona pandemic. Finally, we find that East German citizens show no significant reaction to any of the information we provided.

Our analysis offers insights into the way in which the population reacts to information provided by experts about the pandemic and policy measures taken to fight it. This is important because the extent to which policymakers can react to new empirical evidence in a rational way depends on how the population is willing to react to this evidence. The paper shows that the reaction of the population differs across groups and individuals. There is a systematic correlation between the way people react and their socioeconomic characteristics as well as the way in which they are affected by the pandemic. Through these results our paper contributes to understanding how evidence based policy making may find political support in the population.

Our findings contribute to a steadily growing literature on the Corona pandemic, containment policies, and the determinants of compliance behavior. Recent research highlights several factors influencing compliance with social distancing and other policy measures implemented to contain the spread of the coronavirus.1 These include socio-demographic characteristics (Chiou and Tucker, 2020, Coven and Gupta, 2020, Knittel and Ozaltun, 2020, Papageorge et al., 2021, El-Far Cardo et al., 2021, Muto et al., 2020); differences in risk perception (Allcott et al., 2020, Barrios and Hochberg, 2020, Fan et al., 2020); political affiliation and partisanship (Allcott et al., 2020, Baccini and Brodeur, 2020, Barrios and Hochberg, 2020, Engle et al., 2020, Painter and Qiu, 2020); social capital and trust (Bargain and Aminjonov, 2020, Barrios and Hochberg, 2020, Bartscher et al., 2020, Brodeur et al., 2020, Durante et al., 2021); as well as trust in science (Brzezinski et al., 2020) and the media (Bursztyn et al., 2020, Simonov et al., 2020).2

Most relevant to our paper are studies exploring how information affects behavior and attitudes towards containment measures using survey experiments.3 For instance, Abel et al. (2021) investigate how the perception of risk affects individual behavior during the crisis, and whether correcting biased perceptions could help from a public health perspective. Conducting a series of online experiments in the U.S., the authors document that people overestimate their own COVID-19 mortality risk as well as that of young people but underestimate the mortality risk of older people. Correcting people’s risk perception by informing them about actual risk has no effect on donations for disease control and leads to a decrease in the amount of time invested in learning how to protect others from the virus. However, these negative effects could be counteracted by providing additional information on older people’s risk of mortality.

Akesson et al. (2020) analyze how beliefs about the infectiousness of the coronavirus affects social distancing behavior. They conduct an online experiment in the U.S. and the U.K., where randomly selected treatment groups are shown either upper or lower bound expert estimates of the virus’ infectiousness. They find that, on average, people overestimate the infectiousness and that providing people with expert information rectifies their beliefs to some extent. Moreover, Akesson et al. (2020) show that the more infectious people believe the virus to be, the less willing they are to adopt social distancing measures. The authors explain this finding with fatalism: If individuals believe they are highly likely to be infected by the virus irrespective of their own behavior, they may ignore social distancing and other containment policies.

Other survey experiments on compliance behavior show that the willingness to comply with self-isolation measures depends on how long citizens expect the measures to last in comparison to the official end date announced by the government (Briscese et al., 2020), and that providing information about the safety, effectiveness, and availability of COVID-19 vaccines reduces people’s voluntary social distancing, adherence to hygiene guidelines, as well as their willingness to stay at home (Andersson et al., 2020). Moreover, Daniele et al. (2020) investigate whether the COVID-19 crisis affects attitudes towards policies, values, and (political) institutions. Conducting online survey experiments in Italy, Spain, Germany, and the Netherlands, they find that the Corona crisis has given rise to a sharp decline in interpersonal and institutional trust and has decreased support for the EU as well as for social welfare spending financed by taxes.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section briefly describes the situation in Germany at the time the survey was conducted. Section 3 introduces the survey. In Section 4, we present some descriptive statistics. In Section 5, we introduce our empirical model. The results for different specifications are presented and discussed in Section 6. Section 7 concludes.

2. The situation in Germany

The first coronavirus infections in Germany were detected in late January 2020. It was, however, initially possible to stop the spread of the virus. The number of infections began to increase again in late February, which roughly corresponded with when infection numbers in other European countries increased, too (see Fig. 1). Since the infection numbers soon followed an exponential trend, the federal and state governments took measures to contain the spread of the virus. To the public, these restrictions where justified inter alia with the situation in (Northern) Italy just weeks earlier, were the public health care system was overwhelmed and the number of COVID-19 related deaths soared. The period between mid-March and the end of June (when our survey was completed) can be divided into two phases: a phase characterized by far-reaching restrictions on public and private life (lockdown phase; see the red shaded area in Fig. 1), and a phase in which these restrictions where gradually relaxed (relaxation phase).4

Fig. 1.

Number of new Corona infections per day and cumulative number of infections.

Notes: The figure shows the number of daily infections (dark blue columns, left axis) and the aggregate number of infections (light blue line, right axis) over the period from January 1st until July 1st. The red shaded area indicates the lockdown period characterized by comprehensive restrictions on public life.

Robert Koch Institute (12/7/2020).

The lockdown phase began with the closure of schools and day care centers on March 16. One week later, many businesses and venues where people gather were also shut down, including restaurants, bars, hotels and other lodging places, most retail stores (excluding supermarkets, drug stores, and pharmacies), cinemas, theaters, libraries, museums, and playgrounds. The same applied to personal service providers such as hairdressers, beauty salons, and the like, excluding those providing medically necessary services. Moreover, public events were prohibited, and it was no longer allowed to meet with more than one person living in another household. While it was not forbidden to leave home, people were asked to limit stays in public places to a minimum. As a result of these measures, public life in Germany essentially came to a standstill.

By late April, the infection curve had considerably flattened. The federal and state governments thus decided to gradually relax the lockdown measures. Schools opened again, first only for students of graduating classes, then for other classes as well. However, regular school attendance for all students was only possible again after the end of the summer holidays in August/September. In mid-May, restaurants, hotels, and retail stores were allowed to reopen as well, but employees and customers had to comply with strict hygiene (such as wearing a face mask) and distancing rules. Also, the number of customers allowed in a restaurant or store at the same time was restricted.

3. The survey

We designed a survey that includes an information experiment in order to assess individual attitudes towards the containment measures and to study the impact of providing expert information about the measures’ economic consequences as well as the fatality of the coronavirus on these attitudes.5 The survey was conducted between June 8 and June 20 2020 by forsa, one of the largest public opinion poll companies in Germany. The sample comprises roughly 30,000 randomly selected participants of the so-called forsa.omninet panel. Participants of the forsa.omninet panel are recruited completely offline via phone as a stratified random sample of the German population. Methodologically, recruitment is based on quota sampling, ensuring that the pool of panel participants is representative of the German population aged 18 or above in terms of age, education, household income, gender, and region as depicted by official census data. However, while recruitment is done offline, the survey itself was conducted online, which allows presenting survey participants visual stimuli. During the survey, the respondents are comfortably seated within their own homes. They answer the questions on their computer, mobile device or TV screen (which can be linked to forsa by a set-top-box if the household does not have internet access). Note that all respondents who participated in our survey were already recruited before the Corona pandemic.

The questionnaire can be broadly divided into three parts. The first part contains several questions eliciting whether and in what regard the interviewees were affected by the Corona pandemic. More precisely, the interviewees were asked:

-

•

Whether they or family members were tested positive for the coronavirus (binary variables).

-

•

Whether they were temporarily or permanently dismissed from their job due to the consequences of the Corona crisis (binary variable).

-

•

Whether the Corona pandemic affected their household income (binary variable).

-

•

Whether their relationship with family members and friends has changed for the better or the worse since the onset of the Corona pandemic (ordinal variables measured on a five-point scale).

-

•

To what extent they perceived restrictions on public life to be a burden (ordinal variable measured on a five-point scale).

-

•

Whether they are worried that they may encounter financial difficulties due to the Corona pandemic (ordinal variable measured on a five-point scale).

In order to find out about the interviewees’ priors on fatality rates, we also asked them how many people they believed to have died from the virus out of 1000 positively tested people (under the age of 70/over the age of 70).6 The second part of the survey comprised the information experiment as well questions eliciting the interviewees’ attitudes towards containment measures, and their relaxation. This part started with a brief introductory statement provided to all interviewees:

To contain the spread of the coronavirus, comprehensive measures were implemented in March, which included contact restrictions, a prohibition of public events, and the closure of businesses, schools, and day care centers.

Subsequently, the interviewees were randomly assigned to eight different groups. The first group did not receive any additional information and thus serves as our reference group. Group 2 received information about the economic costs associated with containment measures while groups 3 to 5 received information about fatality rates of different population subgroups7 :

-

•

Group 1 (benchmark):

No additional information was provided.

-

•

Group 2 (economic costs):

According to current estimates, the economic costs of the shutdown may amount to EUR 57 billion per week. Compared to April 2019, the number of unemployed increased by 400,000 persons in April 2020, and approximately ten million employees are currently on short-time work.

-

•

Group 3 (fatality per 1000):

The current fatality rate of COVID-19 measured in Germany is 4.6 per cent. This means that out of 1000 positively tested persons, 46 die. According to health experts, a too early lifting of the restrictions could overwhelm the health care system as was the case in Italy and thus increase the fatality rate.

-

•

Group 4 (fatality per 1000 under 70 years):

The current fatality rate of COVID-19 among people under the age of 70 measured in Germany is 0.8 per cent. This means that out of 1000 positively tested persons who are younger than 70, eight die. According to health experts, a too early lifting of the restrictions could overwhelm the health care system as was the case in Italy and thus increase the fatality rate.

-

•

Group 5 (fatality per 1000 over 70 years):

The current mortality rate of COVID-19 among people over the age of 70 measured in Germany is 21 per cent. This means that out of 1000 positively tested persons older than 70, 210 die. According to health experts, a too early lifting of the restrictions could overwhelm the health care system, as was the case in Italy and thus increase the fatality rate.

To study how interviewees evaluate the trade-off between the economic costs associated with containment measures and the lives they may save, we provided the three remaining groups with information about the economic costs plus the fatality rates:

-

•

Group 6 (economic costs + fatality per 1000):

Information economic costs plus fatality per 1000

-

•

Group 7 (economic costs + fatality per 1000 under 70 years):

Information economic costs plus fatality per 1000 under 70 years

-

•

Group 8 (economic costs + fatality per 1000 over 70 years):

Information economic costs plus fatality per 1000 over 70 years

We are interested in studying whether providing this information influences respondents’ attitudes towards the German government’s measures that were implemented to contain the spread of the coronavirus. To elicit these attitudes, we included two questions. The first question focused on the lockdown measures implemented in mid-March:

What is your opinion on measures implemented by the government in mid-March, that is, the measures in effect prior to the relaxations adopted at the beginning of May?

The respondents could indicate that the measures were (i) far too strict, (ii) somewhat too strict, (iii) just right, or that the measures should have been (iv) somewhat stricter or (v) far stricter.

The second question concerns relaxing containment measures, a process that started at the beginning of May. Respondents were asked the following question:

As of the start of May, the measures have been relaxed. Inter alia, schools are gradually reopened and many stores may open again. What is your opinion on the relaxations?

The answer options were: (i) the relaxations do not go far enough, (ii) the relaxations are adequate, (iii) the relaxations came too early, and (iv) the measures should have been relaxed only when a vaccine or a drug becomes available. In the third part of the survey, we collect additional socio-demographic information about the interviewees, including their sex, age, household income, employment status, employment type, education level, and the state they live in.

4. Descriptive statistics

Before estimating the effects of the information treatments on respondents’ attitudes, we start with a descriptive analysis of the survey answers. Table 1 elicits how the Corona pandemic affected people’s lives by showing the distribution of answers to the corresponding questions.

Table 1.

Influence of the Corona pandemic on people’s lives.

| Were you ever tested positive for Corona? | |||||

| Yes | No/ do not know | ||||

| 0.3% | 99.7% | ||||

| Was a family member ever tested positive for Corona? | |||||

| Yes | No/ do not know | ||||

| 3.4% | 96.6% | ||||

| Have you been released from your job due to the Corona crisis (temporarily or permanently? | |||||

| Yes | No/ do not know | ||||

| 11.6% | 88.4% | ||||

| Did your household income decrease as a result of the Corona pandemic? | |||||

| Yes | No/ do not know | ||||

| 16.7% | 85.3% | ||||

| Are you concerned that the Corona crisis gets you into financial trouble? | |||||

| 1: Not at all | 2: A little | 3: Moderately | 4: Very | 5: Extremely | Do not know |

| 46.6% | 28.0% | 14.9% | 7.2% | 3.2% | 0.1% |

| How much of a burden do you experience the restrictions on public life to be? | |||||

| 1: Not at all | 2: A little | 3: Moderately | 4: Very | 5: Extremely | Do not know |

| 17.5% | 42.3% | 30.1% | 7.3% | 2.0% | 0.2% |

| Has the relationship between you and your family members changed since the | |||||

| beginning of the Corona pandemic? | |||||

| 1: Worsened | 2: Worsened | 3: Did not | 4: Improved | 5: Improved | Do not know |

| a lot | somewhat | change | somewhat | a lot | |

| 2.4% | 12.1% | 69.4% | 11.7% | 3.5% | 0.9% |

| Has the relationship between you and your friends changed since the | |||||

| beginning of the Corona pandemic? | |||||

| 1: Worsened | 2: Worsened | 3: Did not | 4: Improved | 5: Improved | Do not know |

| a lot | somewhat | change | somewhat | a lot | |

| 4.8% | 27.4% | 62.3% | 4.1% | 0.8% | 0.7% |

Only 0.3 per cent of the interviewees stated that they tested positive for the coronavirus. While this number is very small, it roughly corresponds to the total share of positive test results in the German population at the time the survey was conducted. A notable larger proportion, that is, 3.4 per cent of the interviewees, reported to have a family member who had COVID-19. Almost one-third of interviewees stated that their relationship with friends has worsened somewhat (27 per cent) or a lot (five per cent) since the onset of the Corona pandemic; only 15 per cent said the same about their relationship with family members.

More than half of the interviewees (53.3 per cent) reported concerns that they may get into financial trouble because of the Corona pandemic. However, only ten per cent stated that they are very (seven per cent) or extremely (three per cent) concerned. Twelve per cent of the interviewees (20 per cent of those who were employed) have been temporarily or permanently dismissed from their job due to the consequences of the Corona pandemic. The share of interviewees who experienced a reduction in household income due to the Corona pandemic is 17 per cent. These figures highlight the severity of the recession caused by the Corona pandemic in Germany.

How well are people informed about the death toll of the coronavirus? The answer is: rather poorly. A large majority of interviewees underestimate the fatality rates of the coronavirus (cf. Table 2). Among the entire population, the true fatality rate is 46 per 1000 registered cases. The median response given by our interviewees is five, and even the 75th percentile of answers does not reach half of the actual number. In total, 88 per cent of the respondents underestimate the number of deaths per 1000 registered infections. Even more dramatic still is the misperception of the coronavirus’ fatality among the elderly. For instance, 97 per cent of the interviewees underestimate the actual rate of 210. This finding is well in line with the results by Abel et al. (2021), who also document that people severely underestimate the mortality risk of a Corona infection for the elderly.8

Table 2.

Believed fatality rates.

| Mean | Median | Min. | P25 | P75 | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Believed fatality (per 1,000) | 19.9 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 20 | 1,000 |

| Believed fatality under 70 years (per 1,000) | 11.9 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 1,000 |

| Believed fatality over 70 years (per 1,000) | 35.5 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 27 | 1,000 |

Notes: The true number of deaths per 1,000 persons tested positive for the Corona virus is 46 in the entire population, 8 among persons under 70 years, and 210 among persons over 70 years.

Table 3, Table 4 reveal the German population’s attitude towards lockdown measures implemented in March, and their relaxation adopted in May. Two thirds of the interviewees voiced support for the lockdown, while only approximately 17 per cent considered it too stringent. About the same share (16 per cent) wished for even stricter measures to contain the spread of the coronavirus. Slightly less than half of the respondents were satisfied with the relaxation of measures as adopted by the government in May, while 36 per cent thought it was too early to start lifting the measures. Only 15 per cent called for a more extensive relaxation.

Table 3.

Attitudes towards lockdown measures implemented in March.

| What is your opinion on the measures? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Far | 2: Somewhat | 3: Just | 4: Somewhat | 5: Far |

| too strict | too strict | right | too lenient | too lenient |

| 5.8% | 11.1% | 66.2% | 14.0% | 1.8% |

Notes: The number of responses is 29,778.

Table 4.

Attitudes towards relaxations adopted in May.

| What is your opinion on the relaxation of the measures? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Not far enough | 2: Adequate | 3: Too early | 4: No relaxation until |

| vaccine is available | |||

| 15.3% | 48.8% | 34.2% | 1.8% |

Notes: The number of responses is 29,476.

5. Estimation approach

We estimate the following empirical model to evaluate whether the information we provide exerts a causal influence on respondents’ attitudes towards the containment measures as well as their relaxation:

| (1) |

We use two dependent variables, , in our analysis: (i) an ordinal variable indicating respondents’ attitudes towards the lockdown measures in effect between mid-March and the beginning of May, and (ii) an ordinal variable indicating respondents’ attitudes towards the relaxation of lockdown measures adopted at the beginning of May. Both variables are measured on a three-point scale and coded in a way so that higher (lower) values indicate preferences for stricter (more lenient) measures.9 The vector contains seven dummy variables indicating which information a respondent received. Respondents who did not receive any information serve as the reference group.

The vector includes several control variables capturing characteristics of respondents that might influence compliance with or attitudes toward policy measures implemented to contain the spread of the coronavirus — see the discussion in the Introduction. In particular, we control for monthly net household income (dummies for income quartiles); educational attainment (dummies for different educational degrees); sex; age (dummies for different age groups); residence in East Germany; past infection with the coronavirus; past infection with coronavirus in the family; job loss (temporarily or permanently) due to the Corona crisis; reduction in income due to the Corona crisis; dummies indicating whether the relationship to family members (friends) has improved, remained unchanged, or worsened due to the Corona crisis; concern that the Corona crisis may cause financial troubles (dummies indicating degree of concern); believed fatality rates in the entire population as well as among persons younger (older) than 70 years (dummies for overestimation, correct assessment, underestimation, and do not know); as well as a set of dummy variables indicating which party the respondent would vote for at the next federal election.

The control variables should be orthogonal to the information treatment indicators, as the treatment was randomly assigned. However, we include these variables for three reasons. First, the inclusion of control variables should reduce the idiosyncratic error, , of our estimation, thus allowing us to estimate the treatment effects more precisely. Second, we investigate whether treatment effects vary across different population subgroups by interacting the treatment dummies with some of our control variables. Third, the inclusion of control variables may reveal some interesting correlations. A description of all variables as well as descriptive statistics are provided in Table A1 of Appendix A. Since the dependent variables are ordinal, we estimate the empirical model using maximum likelihood logit estimation. We use White-robust standard errors to account for heteroscedasticity.

In an extension, we use interaction terms to check whether treatment effects vary across different population subgroups. Moreover, we check whether the information treatment effects are related to respondents’ prior beliefs about the fatality rate in the entire population/among persons younger than 70 years/among persons older than 70 years using kernel-weighted local polynomial regressions.

The causal interpretation of our treatment effect estimates depends on the random assignment of respondents to the different treatment groups. To test whether the randomization was indeed successful, we check the covariate balance across the treatment groups by regressing the control variables included in our baseline specification on the treatment indicators. This yields 315 coefficient estimates, of which 1.6 per cent have a -value that is smaller than one per cent, while 6.3 per cent have a -value smaller than five per cent. Thus, the share of significant coefficient estimates is close to the expected share of falsely significant ones. Also note that omitting the control variables from our regression leaves the point estimates of the treatment indicators virtually unchanged.10

6. Results

This section presents and discusses the main results from our estimations. We start with the results from our baseline specification (Sections 6.1 to 6.3) and then commence with heterogeneous effects for different population subgroups (Section 6.4). Finally, we explore whether the effects of the treatments involving information about fatality rates vary depending on respondents’ prior beliefs (Section 6.5).

6.1. Baseline estimation

Fig. 2 shows the results of the baseline specification. The figure displays the estimated average marginal effects of the information treatments along with the 90 per cent (transparent lines) and 95 per cent (non-transparent lines) confidence intervals. The results for individual attitudes towards the lockdown measures implemented in March are in the left panel, and for the relaxations adopted in May in the right panel. A table showing the marginal effect estimates of the treatment indicators and all control variables is provided in Appendix B (cf. Table B2).

Fig. 2.

Information treatment effects—baseline specification.

Notes: The figure shows the estimated average marginal effects of the information treatments along with the 90% (transparent horizontal lines) and 95% (non-transparent horizontal lines) confidence intervals. Results are based on ordered logit estimation. White (1980) robust standard errors are used.

The only statistically significant treatment effects we detect are those involving information about the economic costs associated with the March lockdown and those involving information about the fatality rate among the elderly. The estimated effects are of a relevant magnitude. Our results suggest that respondents ‘treated’ with information about the economic costs are 1.5 percentage points (pp) more likely to indicate that the lockdown measures are too strict and 1.5 pp less likely to state that the measures should have been stricter. Compared to the sample averages (16.9 per cent indicated that the lockdown measures were too strict, 15.8 per cent indicated that they were not strict enough), this implies an increase in the share of lockdown opponents of 8.9 per cent and a decrease in the share of supporters of even stricter measures of 9.5 per cent. However, we do not detect a significant relationship between the economic cost treatment, and individual attitudes towards the relaxations implemented in May.

Providing information about the fatality rate among persons over 70 years has the opposite effect. Respondents receiving this information are 1.4 pp less likely to consider the lockdown measures to be too strict, and 1.4 pp more likely to call for even tougher restrictions. Similarly, information about the fatality of COVID-19 among elderly also reduces support for the relaxation of the containment measures. I.e., the information treatment increases agreement with the notion that the relaxations come too early by 2.5 pp. Compared to the sample average (36 per cent), the associated increase in the share of supporters of a more cautious policy stance is 6.9 per cent.

But what about the relevance of the estimated information treatment effects? Whether our estimates can be considered economically significant depends on the perspective one takes. When asked about their opinion toward the lockdown measures adopted in March, 66 per cent of the respondents express their support, while 17 per cent consider them too strict (cf. Table 3). Providing information about the economic costs associated with the lockdown (the fatality rate among persons older than 70 years) decreases (increases) the share of opponents by 1.5 percentage points. While this does not change the fact that supporters of the lockdown still represent a majority, it nevertheless corresponds to an increase (decrease) in the number of opponents by almost 9 per cent, which can be considered a large effect. When it comes to the German public’s opinion toward the relaxations adopted in May, the provision of information about the coronavirus’s fatality among the elderly increases the share of those who would have preferred a longer lockdown by 7 per cent, which again is a relevant magnitude.

Interestingly, the effect that providing information about the fatality rate among elderly has on both attitudes towards the lockdown measures, and their relaxation, remains significant even when respondents are simultaneously informed about the economic costs of the lockdown (although the former effect is now significant only at the ten per cent level). Arguably, this finding indicates that people attach greater importance to saving lives than to minimizing (short-term) economic damage.

Note that, in general, providing individuals with information about the economic and/or health risks of COVID-19 may also affect their responses through a salience effect (Haaland et al., 2021), i.e., prompting people to focus on health or on economic issues in our setting. However, our findings suggest that the treatment effects are driven by the information we provide rather than by making economic and/or health risks salient to respondents. For example, providing information about fatality rates per se does not trigger stronger responses, but only the specific information about fatality rates among the elderly affects attitudes towards lockdown measures.

6.2. Sensitivity checks

We check the robustness of our results in two different ways. First, we use the original variables indicating respondents’ attitudes toward the lockdown measures implemented in March (which was coded on a five-point scale) and toward the relaxations adopted in May (coded on a four-point scale) as dependent variables. The results are depicted in Figs. C2 and C3 of Appendix C. They indicate that respondents who were informed about the economic costs of the lockdown measures are significantly more likely to consider these measures far too strict and somewhat too strict and significantly less likely to consider the lockdown measures somewhat or far too lenient. The opposite is true for respondents who were informed about the fatality rate of COVID-19 among persons older than 70 years as well as those who were provided with information about both the fatality rate and the economic costs. Consequently, our main conclusions appear to be unaffected by our choice of coding.

Second, to account for sample stratification and potential non-random item non-response, we re-estimate our baseline specification using sample weights provided by forsa. The results are shown in Fig. C1 of Appendix C. However, we find that our treatment effect estimates are hardly affected.

6.3. Control variables

Although they do not necessarily have a causal interpretation, it is still interesting to look at the coefficient estimates of the control variables (cf. Table B2 of Appendix B).11 The higher a respondent’s household income, the lower her preferences for strict containment measures tend to be. Respondents in the third income quartile have a 1.5 pp higher likelihood of voicing that lockdown measures were too strict, and a 3.2 pp lower likelihood of considering the relaxation of these measures to be too early. Preferences for stricter (more lenient) measures are also related to age. However, the pattern appears to be non-linear. For instance, respondents between 18 and 29 years of age (reference group), are more likely to call for even stricter containment measures and are more skeptical about the relaxation of these measures than respondents who are older than 29 years. However, beyond the age of 29 years, opposition to the containment measures (their relaxation) decreases (increases), the older a respondent becomes. East Germans as well as respondents whose income decreased due to the Corona crisis are more likely to consider the lockdown measures too strict, and their relaxation too slow. The corresponding marginal effects are 3.6 pp (lockdown measures too strict) and 4.4 pp (relaxation too slow) for East Germans, and 2.3 pp and 3.2 pp for respondents who experienced a decrease in income.

Respondents infected with the coronavirus do not differ from those who were not regarding their attitudes towards the lockdown measures effective in March and April. However, they do have quite different views about the relaxation of these measures. I.e., respondents who were infected with the coronavirus are 8.6 pp more likely to state that the lockdown measures are lifted too slowly and show a 11.5 pp lower likelihood of indicating that the relaxation is premature. However, having a family member who was infected with the virus is not related to individual attitudes towards the lockdown measures and their relaxation.

Not surprisingly, respondents whose relationship to family members and friends has worsened since the beginning of the Corona crisis are more opposed to the containment measures. Respondents who state that their relationship with family members (friends) has worsened (reference group), are 3.9 pp (3.6 pp) more likely to state that the lockdown measures are too strict, and 6.4 pp (5.9 pp) less likely to indicate that the relaxations are premature. Similar effects, albeit of lesser magnitude, are found among respondents concerned that the Corona crisis may cause them financial trouble. A particularly strong effect is found for respondents who experience the restrictions to be a great burden on their life. Those respondents have an 18.6 pp higher likelihood of calling the containment measures too strict and a 19.8 pp lower likelihood of stating that the relaxations are premature (reference group: restrictions are not experienced to be a burden).

We also observe notable differences between the voters of different political parties. Voters of the Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland, AfD), a far-right populist party, demonstrate by far the strongest opposition to containment measures. Supporters of this party are 18.3 pp more likely to consider the lockdown measures to be too strict and have an 18.3 pp lower likelihood of considering the relaxations too far-reaching than voters of chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Party (Christliche Demokratische Union, CDU; reference group). In contrast, supporters of the Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, SPD), which forms the governing coalition together with the CDU, as well as supporters of the Green Party (Die Grünen) and the Leftist Party (Linkspartei), are more likely to indicate that the relaxations came too early.

6.4. Treatment effects for different population subgroups

The Corona pandemic as well as measures implemented to contain the spread of the virus have had highly divergent effects on population subgroups. In this section, we analyze whether differences regarding vulnerability to the Corona pandemic affect respondents’ sensitivity to the information we provide. To this end, we interact the information treatment indicators with several control variables to estimate separate treatment effects for different subgroups. Specifically, in this section, we present separate treatment effect estimates for (i) respondents younger and older than 70 years and (ii) respondents who lost their job due to the Corona crisis. Moreover, we check whether the information treatment effects vary (iii) across male and female respondents, as well as (iv) across respondents living in West Germany and East Germany.12 The corresponding regression equation looks as follows:

| (2) |

is a dummy variables that takes the value 1 if the respondent is younger than 70 years/lost her job due to the Corona crisis/male/living in West Germany, respectively, and a dummy taking the value 1 if the respondent is older than 70 years/did not lose her job due to the Corona crisis/female/living in East Germany, respectively. The vectors and contain treatment indicators and control variables, respectively, and are defined as in the baseline specification of Eq. (1). Note that we estimate Eq. (2) separately for each of the four group variables. To improve readability, we only display marginal effects of the information treatments on the likelihood that respondents oppose the lockdown measures and consider the relaxation to be too slow.

6.4.1. Treatment effects by age

A Corona infection is far more dangerous for older persons than for younger ones. Older persons are more likely to suffer from severe health consequences when infected and are more likely to die of a Corona infection. As highlighted in our information treatments, the fatality rate in Germany is 26 times higher among persons older than 70 years compared to those who are younger than 70. Arguably, this may make older persons more susceptible to the information about the coronavirus’s fatality which, in turn, implies that they react to the corresponding information treatment more strongly. In contrast, younger people may bear a larger share of the economic burden of the lockdown measures, as they have to fear to lose their jobs and income, whereas people aged above 70 years are typically not part of the working population and their income is usually not directly affected by the crisis. This suggests that younger people are more responsive to the information about the economic costs of the government’s lockdown measures. To test these conjectures, we estimate separate treatment effects for respondents younger than 70 years versus respondents older than 70 years. The results are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Information treatment effects by age groups.

Notes: The figure shows the estimated average marginal effects of the information treatments along with the 90% (transparent horizontal lines) and 95% (non-transparent horizontal lines) confidence intervals. Results are based on ordered logit estimation. White (1980) robust standard errors are used.

Our estimates do not support our conjectures. Although our treatment effect estimates vary across both groups of respondents—those who are younger and those who are older than 70 years—and show the expected pattern, the differences we observe are not sizeable and never statistically significant.

6.4.2. Treatment effects by job status

The Corona crisis has resulted in severe economic consequences. During the lockdown in March and April, many businesses had to close, threatening the economic existence of their owners and employees. Other businesses, even though not forced to close, experienced a dramatic decline in profits due to the global recession accompanying the Corona pandemic. Here, we are interested in testing whether those who were economically adversely affected by the Corona crisis react differently to the information we provided than those who were not. For this purpose, we estimate separate treatment effects for those who lost their job (either temporarily or permanently) due to the Corona crisis and those who did not. Our expectation is that the former group is more concerned about the lockdown costs compared to the coronavirus’s fatality. The results are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Information treatment effects by Corona-related job loss.

Notes: The figure shows the estimated average marginal effects of the information treatments along with the 90% (transparent horizontal lines) and 95% (non-transparent horizontal lines) confidence intervals. Results are based on ordered logit estimation. White (1980) robust standard errors are used.

Our findings indicate that the two groups vary particularly regarding their reactions to information about the economic costs of the lockdown. In line with our expectations, respondents who lost their jobs are significantly less likely to disagree with the notion that lockdown measures are lifted too slowly when informed about their costs (average marginal effect: −3.9 pp), while respondents who did not lose their jobs do not react to this information. The difference between the treatment effect estimates across the two groups is statistically significant as well (at the 5% level). Interestingly, for those who experienced a job loss, the effect of information about the lockdown costs remains significantly negative even if this information is combined with information about COVID-19’s fatality. Arguably, this finding indicates that those who were adversely affected by the lockdown are more concerned about the economic consequences of the measures than the risk of an increasing death toll due to removing constraints. Note that we find similar (though less significant) effects for respondents who experienced a decrease income due to the consequences of the Corona pandemic (see Fig. C4 of Appendix C).

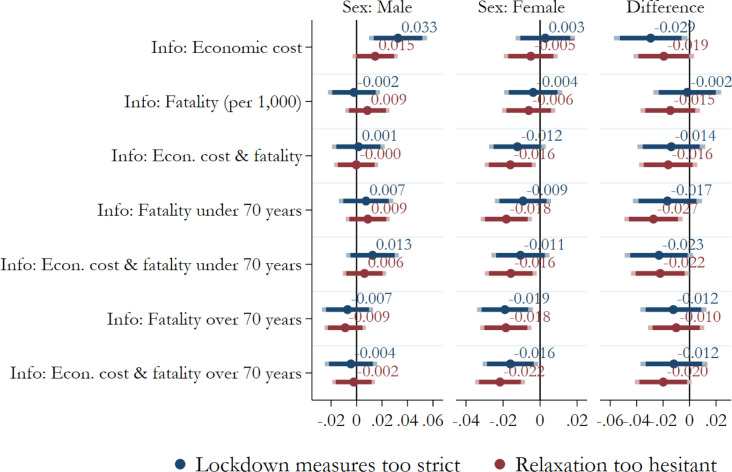

6.4.3. Treatment effects for men versus women

The economics literature provides ample evidence for gender differences in preferences, attitudes, and behavior. Women tend to be more inclined than men to act in a prosocial manner, appear to have stronger other-regarding preferences, and are more risk-averse (Croson and Gneezy, 2009, Eckel and Grossman, 2008). These differences between the sexes also become visible during the Corona pandemic. Based on U.S. survey data, Fan et al. (2020) show that women worry more than men about the physical well-being of others and are also more inclined to reduce their mobility. In light of these findings, we expect that women show a greater reaction to the treatments involving information about the fatality of COVID-19 in that these treatments make them more supportive of lockdown measures compared to men.

Estimating separate treatment effects for male versus female respondents indeed reveals notable (and statistically significant) differences between the sexes. Only female respondents react to information about fatality rates. Revealing the coronavirus’ fatality among persons younger than 70 years as well as among persons older than 70 years significantly decreases their support for the notion that containment measures are relaxed too slowly. This is irrespective of whether information about fatality rates is combined with information about the economic costs these measures impose. Male respondents, on the other hand, are only susceptible to information about the economic costs the containment measures cause. Providing male respondents with this information increases the likelihood that they voice agreement with the notion that the lockdown measures were too strict (their relaxation is too slow) by 3.3 pp (1.6 pp) (cf. Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Information treatment effects by sex.

Notes: The figure shows the estimated average marginal effects of the information treatments along with the 90% (transparent horizontal lines) and 95% (non-transparent horizontal lines) confidence intervals. Results are based on ordered logit estimation. White (1980) robust standard errors are used.

6.4.4. Treatment effects for west and east German respondents

Even 30 years after German reunification, there continue to be significant differences between West and East Germans in terms of attitudes and behavior, which may also have implications for the susceptibility to information we provide. Importantly, notable differences occur regarding political attitudes, which also manifest themselves in voting behavior and trust in public institutions. For example, far-left and far-right populist political parties enjoy much greater support in East Germany, arguably reflecting greater dissatisfaction with the mainstream political parties as well as the political system as such. Greater support for radical parties may also reflect that East Germans are often reported as feeling like second-class citizens compared to West Germans who have higher incomes. Their trust in the federal government and satisfaction with democracy are lower than in Western Germany.13

In addition, the communist government of Eastern Germany systematically disseminated false information (Bursztyn and Cantoni, 2016, Friehe et al., 2020). This portends that East Germans may be less receptive to change their views based on information about economic or health aspects of the pandemic provided by experts. To test whether these difference between West and East Germany affect the impact of information treatments, we estimate separate treatment effects for respondents residing in West and East Germany. Fig. 6 shows the results.

Fig. 6.

Information treatment effects by region.

Notes: The figure shows the estimated average marginal effects of the information treatments along with the 90% (transparent horizontal lines) and 95% (non-transparent horizontal lines) confidence intervals. Results are based on ordered logit estimation. White (1980) robust standard errors are used.

Our estimates reveal that only West German citizens react significantly to the information we provide. West German respondents who are informed about the economic costs of the lockdown measures are 1.6 pp more likely to indicate that they oppose these measures. Providing them with information about the coronavirus’ fatality rate among the elderly decreases the likelihood that they indicate opposition by 1.5 pp. In contrast, for East German respondents the corresponding treatment effects are not significantly different from zero. However, the differences between the two groups are not statistically significant as the confidence bands of the treatment effects for East German citizens are relatively large, suggesting that this group is rather heterogeneous. In fact, we observe that the answers of East German respondents to our questions eliciting individual attitudes toward the lockdown exhibit a larger variation than the answers provided by West German respondents. Nine per cent (14 per cent) of East German respondents consider the lockdown measures implemented in March far too strict (somewhat too strict), compared to five per cent (eleven per cent) in West Germany. With regard to the relaxations adopted in May, 22 per cent of the East German respondents believe that they did not go far enough, compared to 14 per cent in West Germany. At the same time, the share of respondents who consider the relaxations to be ‘just right’ is roughly the same in West and East Germany (49 per cent vs. 48 per cent).

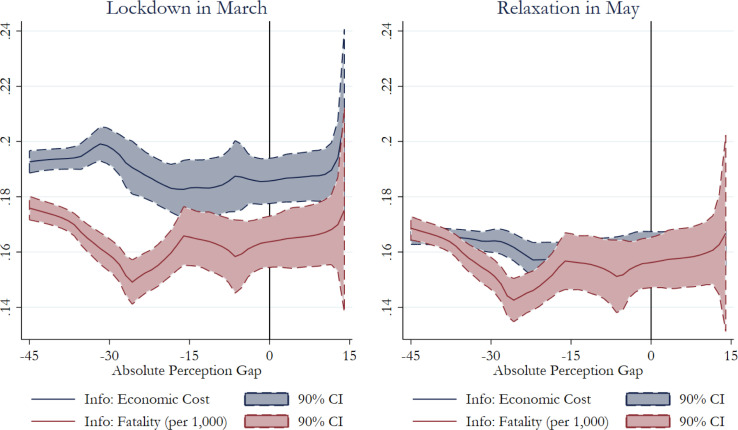

6.5. The role of prior beliefs

Arguably, the effects of information treatments may depend on respondents’ prior beliefs.14 Specifically, respondents whose beliefs about fatality rates are accurate may not react to the information we provide. In contrast, respondents who underestimate (overestimate) these rates may be more (less) inclined to opt for more restrictive measures after receiving the corresponding information. In order to assess the importance of biases in respondents’ beliefs, we proceed in three steps.

First, we estimate Eq. (1) separately for each treatment group (omitting the treatment indicators, of course). Second, we compute the probability of opposing the lockdown measures (considering their relaxation too slow) for each respondent based on the estimation results. Third, we estimate the association between these probabilities and the ‘perception gap’—that is, the absolute difference between the believed fatality rates and the actual fatality rates—using kernel-weighted local polynomial regressions. The perception gap is negative if a respondent understates the true fatality rate and positive if she overstates the true fatality rate.

The results are shown in Figs. 7, 8, and 9. In all three figures, the blue lines show the association between the estimated probability of opposing the lockdown (considering its relaxation too slow) and the perception gap for treatment group 2, i.e., the group that received information about the economic costs of the lockdown. The red lines in Fig. 7 show the association between the two variables for treatment group 3 (fatality per 1000 infected persons), in Fig. 8 for treatment group 4 (fatality among persons younger than 70 years), and in Fig. 9 for treatment group 5 (fatality among persons older than 70 years). The shaded areas represent 90 per cent confidence intervals. The figures’ left panels show the results for lockdown measures implemented in March, the right panels for the gradual relaxation of measures starting in May. The range of the x-axes is determined by the 5th and 95th percentile of the perception gap measures.

Fig. 7.

Information treatment effects depending on prior beliefs about the overall fatality rate.

Notes: The figure shows the association between the probability of considering the lockdown measures too strict (left panel)/their relaxation too hesitant (right panel) and the perception gap (difference between believed and actual fatality rate) for treatment group 2 (info: economic costs of lockdown; blue lines) and treatment group 3 (info: fatality per 1000 infected persons; red lines). The shaded areas show 90% confidence intervals. Results are based on kernel-weighted local polynomial regressions.(For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 8.

Information treatment effects depending on prior beliefs about the fatality rate among persons younger than 70 years.

Notes: The figure shows the association between the probability of considering the lockdown measures too strict (left panel)/their relaxation too hesitant (right panel) and the perception gap (difference between believed and actual fatality rate) for treatment group 2 (info: economic costs of lockdown; blue lines) and treatment group 4 (info: fatality among persons younger than 70 years; red lines). The shaded areas show 90% confidence intervals. Results are based on kernel-weighted local polynomial regressions.

Fig. 9.

Information treatment effects depending on prior beliefs about the fatality rate among persons older than 70 years.

Notes: The figure shows the association between the probability of considering the lockdown measures too strict (left panel)/their relaxation too hesitant (right panel) and the perception gap (difference between believed and actual fatality rate) for treatment group 2 (info: economic costs of lockdown; blue lines) and treatment group 5 (info: fatality among persons older than 70 years; red lines). The shaded areas show 90% confidence intervals. Results are based on kernel-weighted local polynomial regressions.

The results indicate that respondents’ reactions to the information treatments indeed depend on their prior beliefs. If the perception gap is negative (meaning that respondents underestimate the true fatality rate), providing information about the coronavirus’s actual fatality decreases the probability of opposing the lockdown, and of considering its gradual relaxation too slow, relative to the ‘economic costs’ treatment.

Conditional on the perception gap being negative, the probability of opposing the lockdown measures (considering their relaxation too slow) is 2.3 pp lower if respondents are informed about the overall fatality rate, 2.2 pp lower if they are informed about the fatality rate among persons younger than 70 years, and 3.6 pp lower if they are informed about the fatality rate among the elderly. In a similar vein, the probability of indicating that the lockdown measures were lifted too slowly is 0.2 pp/1.2 pp/2.3 pp lower when informed about the fatality rate for the entire population/among persons younger than 70 years/among persons older than 70 years.

However, once the perception gap becomes positive (sometimes a little sooner, sometimes later), the effects of the ‘economic costs’ treatment and the treatments involving information about fatality rates converge.15 Note that comparing those treatment groups that received information about the fatality of COVID-19 to our reference group that did not receive any information yields a similar pattern. However, the treatment effect estimates are somewhat smaller (see Figs. C10 to C12 of the Appendix). Thus, while the average treatment effect estimates are only significant for the ‘fatality over 70 years’ treatment, we obtain significant estimates for the treatment effects on the treated. This also applies to treatments involving information about the overall fatality as well as the fatality among persons younger than 70 years.

As a robustness check, we construct a set of binary variables indicating whether the believed fatality rates are smaller, about the same, or larger than the actual fatality rates. Additionally, we construct a binary variable indicating a non-answer. The results are shown in Figs. C13 to C15 of the Appendix. Our conclusions remain unaffected by this modification to our empirical specification.

7. Conclusions

This paper studies how providing information about health risks caused by the coronavirus and economic costs of lockdown measures affects views about these measures. Our key finding is that citizens respond to receiving information about health risks and lockdown costs; as one would expect, their support for lockdown restrictions increases when they learn about high fatality rates among patients above the age of 70 years and decreases when they are informed about the economic consequences of the lockdown measures.

We also find that different population subgroups react very differently to the information treatments. While men seem to be more worried about the economic costs of shutdown measures and react more sensitively to new information about these costs, women focus more on health risks. The finding that people are more critical about lockdown measures if their incomes have declined during the crisis is intuitive.

What are the implications of our results for economic policy? The key policy conclusion is not that people may or even should be ‘nudged’ into any particular direction by the provision of specific pieces of information. Rather, the main policy conclusion is twofold. First, it is worth providing expert information to the broader public, in particular in crises like the Covid 19 pandemic where uncertainty is large and the set of available information about the crisis changes over time. Not everybody will process this information and react to it, but many will. Second, at a more general level, if more evidence based policy making is desirable, and if participation of the population in reacting to new evidence is needed for political feasibility, it is key to understand whether and how different parts of the population react to this type of information. This paper contributes to understanding the role of expert information in shaping the views prevailing in the population. Of course, our analysis leaves open some important questions in this context and raises new ones. For instance, while we can speculate about why particular parts of the German population do not adjust their views in reaction to expert information, more research is needed to shed light on what these reasons really are. Moreover, to what extent the treatment effects we observe persist over time is also a question future research will have to answer.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Andreas Peichl reports financial support was provided by German Federal Ministry of Health. Clemens Fuest reports financial support was provided by German Federal Ministry of Health. Lea Immel reports financial support was provided by German Federal Ministry of Health. Florian Neumeier reports financial support was provided by German Federal Ministry of Health.

Footnotes

This research includes work financed by the German Federal Ministry of Health . The work was done independently by the authors and on their own responsibility. The views expressed in this paper are thus those of the authors. We are grateful to Manfred Güllner, Ute Müller, and the team of forsa for their help with designing the survey and data collection. We also thank three anonymous referees for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Also related is a study by Picchio and Santolini (2022), who find that electoral turnout decreases in areas with a high share of COVID-19 fatalities, indicating that people reduce their mobility voluntarily.

In addition, Fetzer et al. (2021) provide a systematic assessment of the development and determinants of economic anxiety at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, Haan et al. (2021) examine how the expectation management of the German government affects expectations about the duration of the pandemic and Dylong and Koenings (2022) analyze how news outlets’ communication of macroeconomic information affects policy support. Naumann et al. (2020) analyze political attitudes, risk perceptions, and the social consequences of the lockdown using survey data for Germany.

For a review of methodological questions relevant for the design of information provision see Haaland et al. (2021).

Also see Naumann et al. (2020), who summarize the main policies adopted during the lockdown period and then explore political attitudes to, risk perceptions during, and the social consequences of the lockdown using survey data from Germany.

The questionnaire can be found in the Online Appendix.

We asked for a concrete number for the believed fatality rates. A different option would have been to elicit probabilistic belief distributions (see, e.g., Haaland et al., 2021 for a discussion of the advantages and drawbacks of the different methods for belief elicitation). For example, Harrison et al. (2021), in the tradition of Savage (1971), use incentivized forecasting tasks to elicit the distribution of subjective beliefs about the expected COVID-19 prevalence and mortality. However, their analysis is restricted to 598 students at Georgia State University, while we survey 30,000 individuals representative for the German population.

The estimate of economic costs associated with the lockdown measures was taken from a publication by the ifo Institute (Dorn et al., 2020), the number of unemployed and short-time workers from the Federal Employment Agency (Bundesagentur für Arbeit). Fatality rates were provided by the Robert Koch Institute, a federal government agency responsible for disease control and prevention. Note that we referred to the situation in Italy when informing respondents about the fatality of COVID-19. The reason is that the dramatic scenes occurring in Italy where used as a justification for the imposition of the strict lockdown measures in Germany. However, including this reference may create noise as it implies that respondents receive two pieces of information: fatality rates and the comparison to a nearby country, which brings with it a lot of possible confounders related to how Germans think of the situation in Italy. This should be kept in mind when interpreting the results.

Another explanation for the discrepancy between actual and believed fatality rates is that respondents mistakenly relate the number of corona deaths to the size of the total population when being asked to estimate the fatality of COVID-19. Although we explained in the survey that fatality rates are defined as the number of COVID-related deaths per 1000 persons tested positive for the coronavirus, we cannot rule out that respondents ignored this fact.

The variable indicating respondents’ attitudes towards the lockdown measures implemented in March (relaxations adopted in May) was originally measured on a five-point (four-point) scale. We recoded them to facilitate the interpretation of our results. Note that using the original coding does not affect our results qualitatively, as highlighted in Figs. C2 and C3 of Appendix C.

See Table B1 of Appendix B.

Here we only focus on effects that we deem particularly interesting.

In Figs. C4 to C9 in Appendix C, we present separate estimates for additional subgroups. We divide respondents into groups depending on their net household income, level of education, degree of concern that the Corona crisis may get them into financial trouble, the effect the Corona crisis had on their relationship with family members, and whether they experienced a decrease in income due to the Corona crisis.

Note again, that – as discussed in Section 3 and especially footnote 6 – we asked for a quantitative point belief and not a probabilistic belief distribution. This should be kept in mind when interpreting the results in this section.

In this context, it is important to remember that the large majority of respondents underestimate the true fatality rates: 88 per cent underestimate the overall fatality rate, 74 per cent underestimate the fatality rate among persons younger than 70 years, and 97 per cent underestimate the fatality rate among persons older than 70 years. Consequently, the fit of the local kernel-weighted estimates may become poorer for positive realizations of the perception gap measures.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2022.102350.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary material related to this article.

Additional tables and figures.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abel M., Byker T., Carpenter J. Socially optimal mistakes? Debiasing COVID-19 mortality risk perceptions and prosocial behavior. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Akesson J., Ashworth-Hayes S., Hahn R., Metcalfe R.D., Rasooly I. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Fatalism, beliefs, and behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allcott H., Boxell L., Conway J., Gentzkow M., Thaler M., Yang D. Polarization and public health: Partisan differences in social distancing during the coronavirus pandemic. J. Public Econ. 2020;191 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson O., Campos-Mercade P., Meier A., Wengström E. Available at SSRN 3765329; 2020. Anticipation of COVID-19 vaccines reduces social distancing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccini L., Brodeur A. Explaining governors’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Am. Politics Res. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Bargain O., Aminjonov U. Trust and compliance to public health policies in times of COVID-19. J. Public Econ. 2020;192 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios J.M., Hochberg Y. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Risk perception through the lens of politics in the time of the covid-19 pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Bartscher A.K., Seitz S., Slotwinski M., Siegloch S., Wehrhöfer N. CESifo Working Paper; 2020. Social capital and the spread of Covid-19: Insights from European countries. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscese G., Lacetera N., Macis M., Tonin M. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Expectations, reference points, and compliance with COVID-19 social distancing measures. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur A., Grigoryeva I., Kattan L. IZA Discussion Paper; 2020. Stay-at-home orders, social distancing and trust. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski A., Kecht V., Van Dijcke D., Wright A.L. University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper; 2020. Belief in science influences physical distancing in response to COVID-19 lockdown policies. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesregierung A. 2020. Jahresbericht der Bundesregierung zum Stand der Deutschen Einheit. https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Neue-Laender/jahresbericht-zum-stand-der-deutschen-einheit-2020.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=12, (Accessed: 2021-03-29) [Google Scholar]

- Bursztyn L., Cantoni D. A tear in the iron curtain: The impact of Western television on consumption behavior. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2016;98(1):25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bursztyn L., Rao A., Roth C.P., Yanagizawa-Drott D.H. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Misinformation during a pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou L., Tucker C. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Social distancing, internet access and inequality. [Google Scholar]

- Coven J., Gupta A. New York University; 2020. Disparities in mobility responses to covid-19. [Google Scholar]

- Croson R., Gneezy U. Gender differences in preferences. J. Econ. Lit. 2009;47(2):448–474. [Google Scholar]

- Daniele G., Martinangeli A.F., Passarelli F., Sas W., Windsteiger L. CESifo Working Paper; 2020. Wind of change? Experimental survey evidence on the COVID-19 shock and socio-political attitudes in Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn F., Fuest C., Göttert M., Krolage C., Lautenbacher S., Lehmann R., Link S., Möhrle S., Peichl A., Reif M., et al. EconPol Policy Brief; 2020. The economic costs of the coronavirus shutdown for selected European countries: A scenario calculation. [Google Scholar]

- Durante R., Guiso L., Gulino G. Asocial capital: Civic culture and social distancing during COVID-19. J. Public Econ. 2021;194 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dylong P., Koenings F. Framing of economic news and policy support during a pandemic: Evidence from a survey experiment. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2022.102249. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S017626802200057X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eckel C.C., Grossman P.J. Differences in the economic decisions of men and women: Experimental evidence. Handbook Exp. Econ. Results. 2008;1:509–519. [Google Scholar]

- El-Far Cardo A., Kraus T., Kaifie A. Factors that shape People’s attitudes towards the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany—The influence of MEDIA, politics and personal characteristics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18(15) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18157772. URL https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/15/7772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle S., Stromme J., Zhou A. Working Paper; 2020. Staying at home: mobility effects of COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Orhun A.Y., Turjeman D. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Heterogeneous actions, beliefs, constraints and risk tolerance during the COVID-19 pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer T., Hensel L., Hermle J., Roth C. Coronavirus perceptions and economic anxiety. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2021;10:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Friehe T., Müller H., Neumeier F. Media’s role in the making of a democrat: Evidence from East Germany. J. Comp. Econ. 2020;48(4):866–890. [Google Scholar]

- Haaland I., Roth C., Wohlfart J. Designing information provision experiments. J. Econ. Literature. 2021 forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Haan P., Peichl A., Schrenker A., Weizs”acker G., Winter J. mimeo; 2021. Expectation management of policy leaders: Evidence from COVID-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison G.W., Hofmeyr A., Kincaid H., Monroe B., Ross D., Schneider M., Swarthout J.T. Eliciting beliefs about COVID-19 prevalence and mortality: Epidemiological models compared with the street. Methods. 2021;195:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2021.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knittel C.R., Ozaltun B. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. What does and does not correlate with COVID-19 death rates. [Google Scholar]

- Muto K., Yamamoto I., Nagasu M., Tanaka M., Wada K. Japanese citizens’ behavioral changes and preparedness against COVID-19: An online survey during the early phase of the pandemic. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(6):1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumann E., Möhring K., Reifenscheid M., Wenz A., Rettig T., Lehrer R., Krieger U., Juhl S., Friedel S., Fikel M., Cornesse C., Blom A.G. COVID-19 policies in Germany and their social, political, and psychological consequences. Eur. Policy Anal. 2020;6(2):191–202. doi: 10.1002/epa2.1091. URL https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/epa2.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter M., Qiu T. Working Paper; 2020. Political beliefs affect compliance with COVID-19 social distancing orders. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorge N.W., Zahn M.V., Belot M., Van den Broek-Altenburg E., Choi S., Jamison J.C., Tripodi E. Socio-demographic factors associated with self-protecting behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Popul. Econ. 2021:1–48. doi: 10.1007/s00148-020-00818-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picchio M., Santolini R. The covid-19 pandemic’s effects on voter turnout. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2022;73 doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2021.102161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage L.J. Elicitation of personal probabilities and expectations. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 1971;66(336):783–801. [Google Scholar]

- Simonov A., Sacher S.K., Dubé J.-P.H., Biswas S. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. The persuasive effect of fox news: non-compliance with social distancing during the covid-19 pandemic. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional tables and figures.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.