Abstract

Background and aim:

the healthcare workers, mostly in emergency departments, are exposed to emotionally strong situations: this condition often can lead them to operate incorrectly. In the face of the mistake, many of them experience psychological trauma, becoming “second victims” of the event. In this case they can find comfort in dealing with Peers that can help to understand emotions and normalize lived experiences. A scoping review was conducted to clarify the key concepts available in the literature and understand Peer Support characteristics and methods of implementation.

Methods:

scoping review approach of Joanna Briggs Institute was used. The reviewers analyzed the last twenty-one years of literature and extracted data from relevant studies.

Results:

49 articles were relevant. Articles involve mostly physicians and nurses, but all the other healthcare professionals are included. 56% of the articles have been published in the last two years during the Covid 19 pandemic, which revealed the growing need of developing Peer Support programs; the Anglo-Saxon countries are the main geographical area of origin (82%). Peer support emerges as a preclinical psychological support for people involved in tiring situations. It’s based on mutual respect and on voluntary and not prejudicial help. Peers are trained to guide the support relationship. Peer Support can be proposed as one to one/group peer support, or through online platforms.

Conclusions:

many of the studies affirm that the personnel involved have benefited from the programs available. It is necessary to carry out further research to determine the pre and post intervention benefits. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: Peer Support, Nursing, Stress, Hospital, Emergency, Burnout, Healthcare worker

Introduction

The medical personnel, in particular the nursing one, stands close to patients not only when the latter have the possibility and the clinical conditions to heal, but also when they have to face sudden events and unfortunate prognosis. Health professionals, especially in the field of hospital and extra-hospital emergency, are exposed to emotionally strong situations which can even result in psychological traumas. These, if not identified and treated accordingly, can limit the cognitive status of the personnel and hence the workplace safety (1,2). Chronic stress as well as daily exposure to traumatic events can turn the sanitary professional into a second victim who can develop the burnout syndrome. Nurses, for instance, represent the category showing the highest prevalence of burnout. In particular professionals working in intensive care areas have to face stressful situations in operational contexts characterised by high levels of assistance and organisational complexity (3) and are regularly exposed to potentially traumatic events from a psychological point of view (4). Consequently, it is pivotal to find instruments capable of dealing with such an issue, and one of the tools at our disposal are Peer Support programmes. It is a kind of support that can be provided by someone who has suffered or is still suffering from the same illness, following a training making him/her expert by experience, that is to say Peer Supporter. Sharing such life experiences with others can foster the development of a deeper understanding of one’s own situation. Peer Support increases the assumption of responsibility, autonomy and hope (5).

Peer Support aims at providing emotional and practical support to people experiencing a certain pathologic condition; it can only be offered by individuals having shared or sharing a similar status in the role of patient, relative or professional (6). The main objective of Peer Support interventions is indeed to provide support based on the sharing of information and experiences, mutual consultation and exchange among peers. The WHO conceives the strengthening of social relations as a strategy for the promotion of health and the increase of support resources, such as mutual help (7). Dennis (2003) highlights how Peer Support has become a significant element in the provision of a good quality sanitary assistance. Unfortunately, Peer Support is a complex phenomenon whose application is vague and highly variable, even though its benefits are still investigated as means to improve health (6). Peer Support was first created in the US in the mid Sixties as Peer Counselling among students with disabilities. In 1970 it became a way for former patients with mental pathology diagnosis to discuss common problems resulting from their therapies (8). During the Eighties, the US intervention model arrived in Europe, finding there a fertile soil to grow and evolve (9,10). Generally, a Peer Supporter is an individual sharing similar features with a group or a person, fact enabling him/her to relate with and empathise at a level otherwise impossible for a non-peer. In order to perform this role, a personal growth path towards self-consciousness, the identification of one’s own limits and potentialities is necessary. The Peer should have the ability to engage with others (10). In a study addressed to nurses, the Peer was identified as a person who, following a specific training in psychological first aid, is available to listen to colleagues feeling the need to speak about an emotionally complex event with the purpose of facilitating the elaboration of the emotion linked to this experience (1). The presence of a training for Peer Supporters is relevant to recognise situations creating inconveniences and discomfort in people receiving the support (11), focusing on avoiding the professionalisation and the successive creation of paraprofessionals thus risking diminishing mutual identification, credibility and feeling of commonality in patients (6).

Through the sharing of experiences and mutual understanding resulting from common traumas, Peer Support gives a chance for personal growth, reflection, conferral of new meanings to the experience lived (12). Results, albeit providing weak statistical evidence, show an emerging knowledge on needs and benefits of Peer Support programmes, even though, as claimed by Anderson (2020), comparing the effectiveness of various Peer Support programmes in mitigating the effects deriving from a critical event is extremely difficult and there are rarely quality evaluations of the impact that such programmes can have on mental health and absenteeism.

Studies carried out on experiences of Peer Support among healthcare workers in hospital mainly concern emergency wards for they typically require working in stressful situations and with higher contentious levels compared with other wards (13, 14, 15). Several studies underline that those who experience the second victim phenomenon find relief in relating with their recognised Peers or colleagues (16). Peers have got three important instruments at their disposal: listening, evaluation and support. They offer to colleagues the possibility to express their difficulties, frustrations, fears and emotions, creating an environment of empathic listening. Peers can help their colleagues to acknowledge their emotions and identify the aspects for which an external professional aid is necessary. For this reason, the Peer is guided by expert professionals guaranteeing him/her an adequate training and supervision (15). Peer Support programmes for healthcare workers were developed not only during the Covid-19 pandemic, but also in occasion of other global ‘catastrophes’, such as the SARS epidemic, the H1N1 flu or the World Trade Center disaster (17).

At the very base of all these methodologies it is nonetheless essential to always have a culture assuring the healthcare workers’ mental health as this fosters the safety of the patient himself (18).

Aims of the work

The study aims at clarifying what is meant in the literature for Peer support, not only for physicians and nurses, but also for all the other healthcare professionals who work in contact with patients, answering to the following research questions identified for this study: What does Peer Support among sanitary professionals mean? Who is identified as Peer Supporter among healthcare workers? Which kind of training is envisaged for Peer Support? What is the function of Peer Support among health professionals? What are the contexts of use of Peer Support in the healthcare domain? What are the modalities of Peer Supporting? What is the diffusion and the development of Peer Support in the national and international scenario?

Methodology

To realise this Scoping Review the work followed from the beginning the guidelines of the Joanna Briggs Method Manual for Scoping Review (19). Starting from the definition of Peer Support provided by Dennis in 2003 (6), the review was conducted in the literature produced in the last 21 years, between January 2000 and December 2021. The scientific literature was researched through the following databases: Cochrane Library, Pubmed, Cinahl, Ovid, Google Scholar, Embase. The details of the research strategy used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Database search strategy.

| Database | Group 1 | Group 2 |

|---|---|---|

| PUBMED | Peer support AND Healthcare worker AND Burnout AND Hospital | Professional burnout AND Coping behaviour AND (Healthcare providers AND Peer support |

| Peer support AND Healthcare worker AND (First aid OR Emergency) AND Hospital AND Stress | Peer support AND Healthcare worker AND Burnout AND Emergency AND Hospital | |

| Peer support AND Healthcare worker AND Burnout | Peer support AND Healthcare workers AND Stress AND Burnout | |

| (Peer group OR Social support) AND Emergency AND Burnout AND Resilience | ||

| (Healthcare workers OR Nurses OR Medical workers OR Healthcare professionals) AND Peer support AND Stress AND Emergency | ||

| COCHRANE LIBRARY | Peer support AND Healthcare worker AND (First aid OR emergency) AND Hospital AND Stress | Peer support AND Burnout AND Stress AND Nurse |

| (Healthcare worker OR Nurses OR Medical workers OR Healthcare professionals) AND Peer support AND Stress AND Emergency | Peer support AND Healthcare worker AND (Emergency OR First aid) | |

| Peer support AND Healthcare worker AND Burnout | Peer support AND Burnout AND Emergency AND Hospital | |

| (Peer group OR Social support OR Peer support) AND Burnout AND (Health personnel OR Nurses) | Peer support AND (Burnout OR stress) AND Emergency AND (Resilience or Coping) AND Nurse AND Emergency AND Healthcare worker | |

| Peer support AND Healthcare worker AND (Burnout OR Stress) AND Hospital | Peer support AND Coping AND Nursing | |

| (Peer group OR Social support OR Peer support) AND (Emergencies OR Emergency) AND (Stress OR Burnout) AND (Resilience or Coping) | ||

| EMBASE | (Peer group OR Peer support) AND Physiological stress AND (Emergency ward OR Emergency health service) | Peer support AND Burnout |

| (Nurse OR Clinician) AND Peer support AND (Burnout OR Professional burnout) | Peer support AND Emergency AND Nursing | |

| (Burnout OR Physiological stress) AND (Psychological resilience OR Coping behaviour) AND (Emergency ward) | Peer support AND Healthcare Worker AND Hospital | |

| (Peer group OR peer support) AND (Nurse OR Clinician) AND (Burnout OR Physiological stress) AND (Psychological OR Coping behaviour) | ||

| CINAHL DATABASE | Peer support AND Healthcare worker AND (Burnout OR Stress) AND Hospital | Peer support AND Healthcare workers AND (Stress OR Burnout) AND Resilience |

| Peer support AND Healthcare worker AND (First aid OR Emergency) AND Hospital AND Stress | Peer support AND Healthcare workers AND (First aid OR Emergency) AND professional burnout | |

| Peer support AND Healthcare worker AND Burnout | ||

| (Peer group OR Social support OR Peer support) AND (Emergencies OR Emergency) AND (Stress or Burnout) AND Resilience OR Coping | ||

| (Healthcare workers OR nurses OR medical workers OR healthcare professionals) AND Peer support AND Stress AND Emergency | ||

| OVID | Peer group OR Social support OR Peer support) AND (Emergencies OR Emergency) AND (Occupational Stress OR Psychological stress) | Peer support AND Healthcare workers NOT Patient AND Emergency |

| (Peer group OR Social support OR Peer support) AND Burnout AND (Health personnel or Nurses) | ||

| Peer group OR Social support OR Peer support) AND (Health personnel OR Nurses) AND (Stress OR Burnout) and (Resilience OR Coping) | ||

| Peer group OR Social support OR Peer support) AND (Emergencies OR Emergency) and (Stress OR Burnout) and (Resilience OR Coping) | ||

| GOOGLE SCHOLAR | Peer support AND Healthcare workers AND Hospital AND First aid AND Stress | Peer support AND Healthcare professionals AND Emergency AND Resilience AND Burnout |

| Peer support AND Resilience AND Healthcare worker | Peer support AND Nurse AND Healthcare workers NOT patient NOT Caregiver AND Hospital AND Emergency AND First aid AND Icu stress AND Resilience AND Burnout | |

| Nursing AND Healthcare worker NOT Patient AND Peer support AND Hospital AND Emergency AND First aid AND Burnout AND Stress AND Coping AND Resilience |

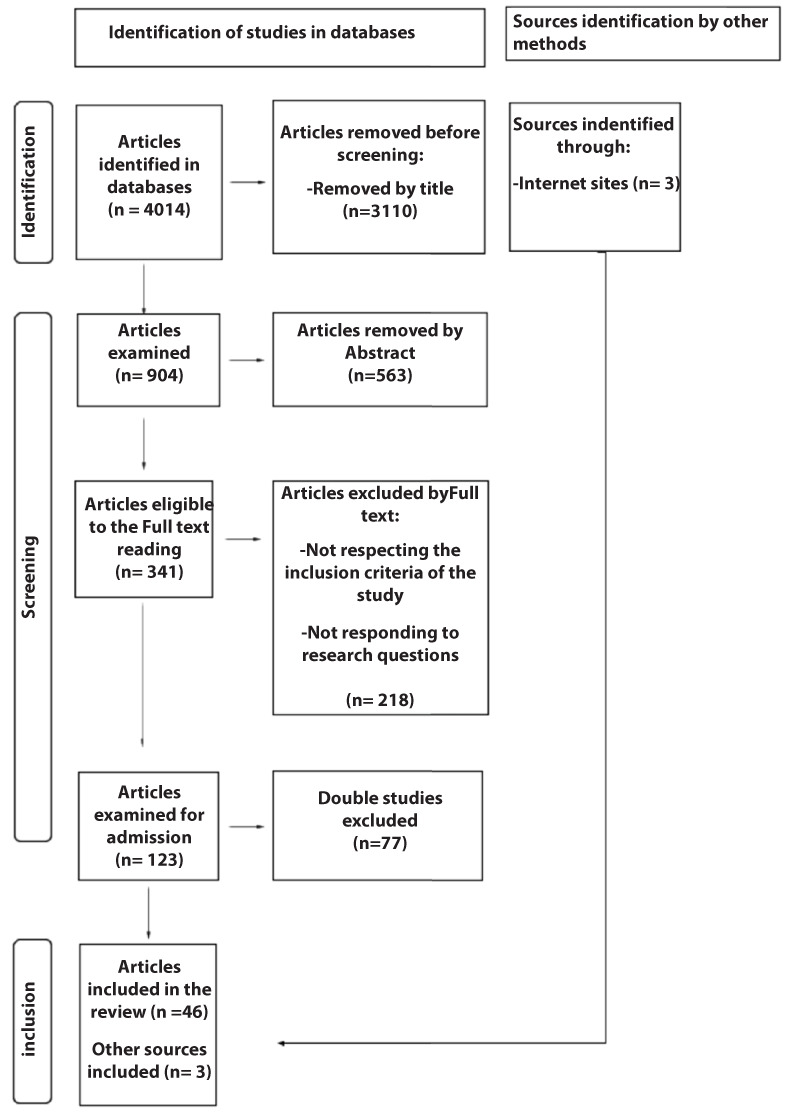

The inclusion criteria are the following: I) English and Italian language, II) any type of study, included grey literature, III) exclusive interest in the field of healthcare professionals in the hospital and extra-hospital environment. In total, 4014 articles were identified. Autonomously, two members of the research group (first and second author) read every title/abstract and determined whether they were relevant in the light of the research question and the inclusion criteria. In this way, 3110 articles were directly removed at the stage of titles reading, 563 more were, on the other hand, removed at the stage of abstracts reading. If the pertinence of a study was yet to be clarified, this article was then read in its integrity, which lead to the further removal of 218 articles, for they were not pertinent and did not respect the aforementioned criteria. 77 articles were doubles, identified and thus excluded. 46 studies were deemed to be pertinent, with the addition of three documents coming from grey literature sources. A flowchart representing the selection process of each phase of the review is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of sources screened and included in the Scoping Review.

At the end of an attentive revision, a synoptic table for the extraction of data was created on the basis of the following domains: title, author, year, journal, type of study, sample, context, geographical area, objective, results, research questions answered in the article. The table with the results obtained from the review process provides information on the corpus of the research carried out (Table 2).

Table 2.

Synoptic Table of data extraction - an extract.

| Title | Author | Year | Journal | Type of study/ methodology | Sample/context/ country | Aim of the study | Results of the study | Research questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Battle Buddies: Rapid Deployment of a Psychological Resilience Intervention for Health Care Workers

During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic |

Cristina Sophia Albott; Jeffrey R. Wozniak; Brian P. McGlinch; Michael H. Wall; Barbara S. Gold;Sophia Vinogradov; | 2020 | International Anesthesia Research Society |

Special article Buttle Buddy check-in through a five questions-survey; application of the revisited Buttle Buddy model for healthcare workers according to the sequence ANTICIPATE-PLAN- DETER, through inoculation of stressors and resilience training |

Not specified sample of healthcare workers/ Covid 19 Pandemic/ U. S.A. | The study aims to be a guideline for all future programs dealing with psychological resilience in the work environment, specially in the sanitary one. | At the moment of the publication the study was still in progress: no defined results. | What does Peer Support among sanitary professionals mean? Who is identified as Peer Supporter among healthcare workers? What is the function of Peer Support among health professionals? What are the contexts of use of Peer Support in the healthcare domain? What are the modalities of Peer Supporting? |

|

Buddy Care, a Peer-to- Peer Intervention: A Pilot Quality Improvement Project to Decrease Occupational Stress Among an

Overseas Military Population |

Jean F. Villaruz Fisak; Barbara S. Turner; Kyle Shepard; Sean P. Convoy; |

2020 | Military Medicine |

Qualitative study/ Pilot study Pre-test with 79 items; Post-test three and six months after the intervention. |

40 U. S. Navy healthcare workers assigned to three patient units/ Military Hospital/ Guam | To implement and consider “Buddy Care” (fundamental component in Navy programs), as an evidence-based intervention in stress management. | The sample considered is too small to make significant statistics. A replica of the project is recommended. |

What does Peer support among sanitary professionals mean? Who is identified as Peer supporter among healthcare workers? What is the function of Peer support among health professionals? What are the contexts of use of Peer support in the healthcare domain? What are the modalities of Peer supporting? |

| Building a Program of Expanded Peer Support for the Entire Health Care Team: No One Left Behind | Timothy E. Klatt; Jessica F. Sachs; Chiang-Ching Huang; Alicia M. Pilarski. | 2021 | The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety | Case report | 149 physicians and nurses/ Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board/U. S. A. | To describe the implementation of a Peer Support Program for an entire health system. | The study highlights that the team implemented with success a Peer Support Program with trained Peers. | Which kind of training is envisaged for Peer Support? |

| Burnout in Physicians: a Case For Peer- Support | S.M.Bruce; H.M. Conaglen; J.V. Conaglen; |

2005 | Internal Medicine Journal |

Original Article 83 surveys sent; the data analysis includes descriptive statistics, using t-test for the comparison with other studies. |

83 physicians / different working contexts/ New Zealand (Waikato and Bay of plenty) | To observe the level and the presence of burnout in a sample of New Zealand physicians; to show up the necessity to create support systems/ peer supervision. | The study shows up the presence of significant difficulties for doctors in the working context; just 50 of them answered the survey; all of them sunstein the need of a Peer Support model in the working environment, through group intervention or through single intervention. | Who is identified as Peer Supporter among healthcare workers? What is the function of Peer Support among health professionals? What are the modalities of Peer Supporting? |

| CAIR: Implementation of peer response support for frontline health care workers facing the COVID-19 pandemic | Rubin, E. W.; Rassman, A. | 2021 | Social work in health care |

Qualitative study Peer Support through in sync online videos, One-to-One Peer Support, other resources; online survey to have results. |

71 healthcare workers/ Not specified context/Seattle, U. S. A. |

To determine the benefit of the rapid development of a Peer Support Program during the Covid 19 Pandemic. | The speed of development and application of this program contributed to the low efficacy of the study; the participants were just 13; however the study can be the start point for new projects for possible new clinical emergencies. | What is the function of Peer Support among health professionals? What are the contexts of use of Peer Support in the healthcare domain? What are the modalities of Peer Supporting? |

|

Care of the clinician after an

adverse event |

PrattS. D.Jach a B.R. | 2015 | International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia 2015 24:1 (54-63) |

Review Article Review of the existing literature. |

Physicians, not specified sample/ Intensive Care and Anesthesiology Departement/ Boston, U. S. A. | To describe how to take care of “Second Victims” identifying signs and needs. | Second Victims could not be able to ask for help and Sanitary Systems should develop programs to give emotional support. | What does Peer Support among sanitary professionals mean? Which kind of training is envisaged for Peer Support? What is the function of Peer Support among health professionals? What are the contexts of use of Peer Support in the healthcare domain? |

| COVID-19 Pandemic Support Programs for Healthcare Workers and Implications for Occupational Mental Health: A Narrative Review | David, E., DePierro, J.M., Marin, D.B. et al. | 2021 | Psychiatric Quarterly | Narrative Review Research on Medline/Pubmed, Cochrane Library, and Embase. Inclusion Criteria : Healthcare workers’ mental health during Covid 19; studies publicated between April 2020 and April 202; inclusion of studies whose validation of effectiveness was in progress or needed update. |

Not specified sample of healthcare workers/Covid 19 Pandemic/ U. S. A., Europe, Asia, Australia. |

To resume the initiatives developed during the Covid 19 Pandemic to support healthcare workers’ mental well being, in the context of pre- existing guidelines on mental health at work. | A negative period like Covid 19 Pandemic, definitely, could help to catalyze a positive change and a transformation for healthcare workers’ mental well being. The hope is that healthcare workers accept psychological interventions and make good use of these, supplementing in their working days seeing the efficacy noted. |

What is the function of Peer Support among health professionals? What are the contexts of use of Peer Support in the healthcare domain? What are the modalities of Peer Supporting? |

| Covid-19: peer support and crisis communication strategies to promote institutional resilience | Wu, A. W., Connors, C., Everly, G. S. |

2020 | Annals of Internal Medicine, 172, 822-823 | Case Report | Not specified sample of healthcare workers/Covid 19 Pandemic/The Johns Hopkins Hospital/ Baltimora, Maryland | To describe the three strategic principles useful to Sanitary Institutions involved in the Covid 19 Pandemic. The third principle concerns Peer Support Programs. | The approach described in the report has the potential to improve organizational cohesion, resilience and healthcare workers’ well being. | What does Peer Support among sanitary professionals mean? What is the function of Peer Support among health professionals? What are the contexts of use of Peer Support in the healthcare domain? What is the diffusion and the development of Peer Support in the national and international scenario? |

|

Creating the Hematology/Oncology

/Stem Cell Transplant Advancing Resiliency Team: A Nurse-Led Support Program for Hematology/Oncology /Stem Cell Transplant Staff |

Schuster M.A. | 2021 | Journal of pediatric oncology nursing :official journal of the Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses | Process paper/pilot study The HART Program offered a confidential space for interaction, for group/ one-to-one support, and for multiple ways of intervention. |

Every professional at the service of hospitalized oncological patients or stem cell transplant patients, not specified sample/Boston Children’s Hospital/Boston, U. S. A. |

To evaluate the efficacy of the Hematology/Oncol ogy/Stem Cell Transplant Advancing Resiliency Team (HART): a peer-to-peer support program guided by Nurses for all the healthcare personnel. | The HART program has been well received and used a lot by the personnel. An increase of more than 25% has been registered for the extreme satisfaction with this work support intervention. |

Who is identified as Peer Supporter among healthcare workers? Which kind of training is envisaged for Peer Support? What is the function of Peer Support among health professionals? What are the contexts of use of Peer Support in the healthcare domain? What are the modalities of Peer Supporting? |

| Deployment of a Second Victim Peer Support Program: A Replication Study. | MERANDI, J. et al. | 2017 | Pediatric quality & safety, [s. l.], v. 2, n. 4, p. e031 |

Retrospective Study Draft of a report about the advancements of the “forYOU/You matter” program in the various stages of application, to draw final conclusions. | 232 Peer Support Meetings/ Nationwide children’s hospital/ U. S. A. | To implement awareness about the “Second Victim” phenomenon developing a Peer Support Program named “You matter” | Replication of the “forYou” Peer Support Program designed by MUCH (University of Missouri Health Care’s). The University, with NCH, from 2013 developed various stages of the program. From 2013, 300 peer supporters has been formed, 232 peer to peer meetings and 21 group meetings have been done. |

Who is identified as Peer Supporter among healthcare workers? Which kind of training is envisaged for Peer Support? What is the function of Peer Support among health professionals? What are the contexts of use of Peer Support in the healthcare domain? What are the modalities of Peer Supporting? |

Results

The 49 selected studies were analysed in the following conceptual categories.

Type of study

Quantitative type of studies (n = 17; 35%), in detail: 4 experimental studies, of which 2 Randomised Controlled Trials, 13 non-experimental studies of which 1 descriptive, 4 transversal, 8 observational (1 cohort, 2 pilot studies, 2 retrospective, 3 prospective). Qualitative studies (n = 6; 12%), review articles (n = 8; 17%), Case Report (n = 7; 14%), quali-quantitative studies (n = 2; 4%) and grey literature articles (n = 3; 6%).

Methodology of studies

Methodologies of studies were catalogued for prevalence and subdivided in macro areas.

The questionnaire resulted as the most used instrument (n = 11; 23%), followed by the methodology of reviews (n = 9; 19%), detailed narrative for the redaction of reports (n = 7; 15%), mixed methodology (n = 6; 13%). Furthermore, we found the direct application of Programmes with the creation of interactive spaces (n = 4; 8%), the subdivision in case-control groups (n = 3; 6%), the Focus Group (n = 2; 4%) and the structured interviews (n = 1; 2%). The last category contains non-specific methodologies such as manuscripts, didactic material, summary (n = 5; 10%).

Population of studies

The reference population of the selected articles concerns all sanitary professionals. We refer as population object of the research to: mixed samples of professionals without specifying their specialisation (n = 26; 59%), doctors (n = 7; 15%), the nursing category (n = 7; 14%), samples of doctors and nurses in mixed modality (n = 3; 6%), other healthcare workers, among which paramedics, therapists responsible for radiations and students majoring in Medicine (n = 3; 6%).

Temporal analysis

The publication years of the studies are:

2005 (n = 2; 4%), 2006 (n = 1; 2%), 2007 (n = 1; 2%), 2008 (n = 2; 4%), 2012 (n = 1; 2%), 2014 (n = 1; 2%), 2015 (n = 2; 4%). We can notice an increase in publications during the years: 2016 (n = 3; 6%), 2017 (n = 2; 4%), 2018 (n = 4; 8%), 2019 (n = 3; 6%), 2020 (n = 12; 25%), 2021 (n = 15; 31%). This increase, concentrating particularly during the last two years, is linked to the Covid-19 Pandemics.

Geographical context

Sources stem from: the United States of America (n = 25; 51%), Australia (n = 5; 11%), the United Kingdom and Canada, both with 4 articles (8% each), New Zealand (n = 2; 5%), Sweden (n = 2; 4%), China (n = 2; 4%) and Italy (n = 1; 2%). Finally, we find articles that, having analysed several studies and hence different geographical areas, were catalogued as mixed geographical context (n = 4; 8%).

Intervention contexts

The analysis shows that the majority of the studies does not refer to a specific context where it is possible to benefit from Peer Support (n = 17; 35%); the necessity for support originates rather from difficult working experiences. We observe the predominance of the Critical Area and Anaesthesia (n = 10; 21%), because of the high risk of adverse events contributing to the personnel’s stress, followed by the Covid-19 pandemic context (n = 8; 16%). The oncological field (n = 5; 10%) and the paediatric one (n = 4; 8%) are contexts in which the experiences lived by patients can affect operators’ emotions. We then find the territorial emergency context (n = 2; 4%), military hospitals (n = 2; 4%) and the domain of mental health (n = 1; 2%).

Objectives of the studies

Frequently, the finality, more or less common, to describe, introduce, evaluate or implement a support programme is reported (n = 17; 35%). In addition, some studies tried to evaluate the benefit, the efficacy or the development of a programme, with the objective to foster awareness (n = 8; 17%) and others intended to identify, explore and evaluate the healthcare operators’ needs, the causes of stress and burnout, recognising possible interventions and investigating the necessity and the perception of support (n = 7; 14%). Among the finalities identified, there were some to resume and describe initiatives, interventions, resources and strategic principles to support the wellbeing (n = 4; 8%); to analyse and recognise already existing support methods (n = 3; 6%); to analyse and describe support experiences and how they were profitable (n = 2; 4%); the relation among support, stress and burnout was examined (n = 2; 4%). Finally, six other categories emerged, each supported by 1 article (n = 1; 2%) with other, more detailed, objectives: to serve as a guideline to create future support programmes; to examine the relations among support, auto efficacy and resilience; to identify the role of the Peer Supporter; to evaluate operators trained for support; to evaluate storytelling modalities; to pilot a virtual experience of support in order to demonstrate its acceptability. It remains intrinsic the desire to sensitise on the topic, focusing on the past of the operators and on the potential benefits.

Studies results

In order to catalogue articles based on their results, pertinence areas were defined unifying the main common features of the studies. The demonstration of the Peer Support interventions efficacy in different working contexts (n = 23; 47%); Peer Support as a successful instrument in the management of adverse events, stressful situations, anxiety and burnout and of critical and hurtful moments. Subsequently, numerous Peer Support interventions were enacted during the Covid-19 pandemic. The positive evaluation in the application of pre-existing and already functioning Peer Support programmes, highlighting its validity and encouraging its replication in several different realities (n = 12; 25%); among these programmes: Resilience in Stressful Events (R.I.S.E.), Hematology/Oncology/Stem Cell Transplant Advancing Resiliency Team (H.A.R.T.), forYOU, Ice Cream Round, CopeColumbia, Schwarts Rounds. It is reported the clear necessity to create Peer Support programmes where not yet present (n = 8; 16%), studies underline the demand for a major involvement of the institutions and the sanitary systems as long as stress prevention and management, burnout and post traumatic syndromes are concerned, through the incentivisation and the elaboration of programmes and the education and the training of Peer Supporters. Finally, some articles were catalogued as non-statistically meaningful, because of programmes being still in process, too small samples, or results minor than those expected due to scarce participation (n = 6; 12%).

Discussion

This scoping review provides a framework of the current knowledge on Peer Support, described after having gathered and analysed the scientific and the grey literature (Table 3).

Table 3.

Answers to research questions.

| Peer Support | Definition Emotional support, between colleagues considered peers, to support wellbeing and front stressing situations, through the condivision of experiences. |

Identity

|

Training

|

Function

|

Context

|

Mode

|

Diffusion

|

What does Peer support among sanitary professionals mean?

The individual Peer Support is a psychological process through which people gain a sense of self efficacy and aim, by means of sharing one’s own narrative (20), emotions and perspectives (21). A way to give and receive support (22), to face professional fatigue, weariness, stress and burnout (23), to support emotional well being and improve healthcare workers’ resilience (24). It is the social support stemming from working sources that allows people to develop feelings of belonging and solidarity, leading to healthier coping behaviours, helping people redefine difficult situations and improving the regulation of feelings such as mistrust, anxiety and fear (25). It refers to a group of healthcare workers reciprocally supporting each other after a sudden, overwhelming crisis (26), adverse medical events (27, 28, 29), offering psychological first aid and emotional support (17). Its distinctive features are: peer credibility, immediate availability, voluntary access, confidentiality, emotional first aid (non-therapeutic), easiness of access to the following support level (27), 24/7 availability for the whole hospital personnel and being provided by trained Peer answerers (29).

Who identifies himself/herself as Peer Supporter among healthcare workers?

Peer Supporters are selected not to be friends nor confidants, but are rather coupled with Peers based on similar working perspectives, similar specialities and disciplines to remove hierarchical challenges (22), life experiences and exposure to stress factors (20). Desired features include leadership capacity, reliability, efficacy, communication skills and second victim personal experience (18), respect, empowerment and mutual trust (23). The partnership should be voluntary (23). Peer Supporters should be reliable colleagues, able to guarantee a safe environment to talk and having the necessary emotional and relational capacity (13) to have emotionally strong conversations and set aside personal relations (30). It is important for Peer Supporters to be self-sympathetic as this feature is associated to psychological well-being and adaptability (16).

The most desire support sources, depending on the context, are other doctors, suggested by colleagues, having common experiences of errors and/or controversies (31), nurse colleagues (32), nurse colleagues from unities of neonatal intensive care (33), respected anaesthetists and doctors (13), sympathetic and non-judgemental with an interest in the well being and the will to dedicate time to the programme (34).

What kind of training does Peer Support envisage?

Having training helps to develop relational skills, the ability to understand and recognise situations, provides knowledge to identify behavioural alarm signals, recognising the limits and sending, when necessary, people to other professionals, expands one’s own active listening and negotiating skills in emotionally engaging conversations (34). Training courses vary from 2 h to 5 h, with recalls during other learning days (35), in presence or through online platforms. In some cases, follow-up meetings and debriefings are organised after months (13, 36), with the possibility to ensure a continuative trust in the role (34). To leaders, it can be taught the concept of Peer Support and of crisis management (26, 36, 37, 38), the concept of second victim and simple steps to help the personnel after an adverse event (18, 27, 36, 39). Even training in psychological first aid (PFA) is a form of early intervention to deal with emotional discomfort (28, 29, 34). Teachings can include several exercises that stimulate reflections on the solicitations to which professionals are subject after being exposed to these events. One of the components of the training is the stimulation, where Peer Support is shown through past or potential successful cases examples (13, 34).

What is the function of Peer Support among sanitary professionals?

Peer Support is a relation where crises are overcome through encouragement, social support and hope (4, 22). The objective of Peer Support programmes is, above all, to provide an efficient recovery from the event and then limit the recurrence of an error. A sanitary operator duly supported will know how to act in the aftermath of a stressful event, will effectively support involved patients/caregivers, will know how to prevent the recurrence of the same error and limit negative consequences of an adverse event, foster resilience (40), protect from correlated anxiety and/or depression (33). Peer Support, diminishing emotional stress and increasing professional life quality, ensures patients’ safety (33). Among the objectives, are listed: to learn to navigate through familiar/personal dynamics and complex moral, ethical and medical scenarios, to address professionals to potential hospital or interdisciplinary resources, to promote personal well being in the working environment (41); to create a non-judgemental atmosphere in order to explore without fears feelings and attitudes (42); to prevent burnout (43), stress and anxiety (44); to identify wrong or dangerous behaviours and to express listening and negotiating skills in complex emotional conversations (34); to facilitate emotional decompression, diminish the isolation phenomenon identifying social support networks and fostering resilience (1) and coping strategies (24). Peer Support groups represent an opportunity of discussion and reflection with colleagues to share and compare experiences and of mutual learning, to face situations perceived as stressful (38, 45), to maintain a sense of psychological well being, self-efficacy and hope identifying individuals predisposed to stress reactions and connecting every professional with his/her Peer (20).

Which are the application contexts of Peer Support in the sanitary field?

Among the contexts where Peer Support programmes are considered necessary, we find: Intensive Care wards and Intensive Care operational units (4, 16, 27), where patients’ criticality leads healthcare workers to be in a continuative contact with death, to work for long shifts thus facilitating the possibility of crises occurrence and mental instability (34, 46), first aid and territorial emergency (1, 4, 47); paediatric intensive care (26, 33); cardiothoracic intensive care (18), stressful areas because of treatments’ intensity and the difficult decisions to take (32, 36). Widely cited are oncologic wards where nurses are especially vulnerable to anguish feelings caused by the interactions with patients and families in a spirit of uncertainty and fear to die (38, 41, 48). The Covid-19 pandemic led to the need for support because of the inadequate working conditions, in terms of available personnel and devices figures (22, 49), isolation and increased pressure (50), fear of contamination leading to post-traumatic stress situations (17, 30, 51). To exhaust the contexts, we cite the university domain as, during the education period, emergency medicine doctors are subject to exhausting shifts and exposed to hitherto never experiences working situations hence increasing the stress level (43, 44): the military domain (20, 23), the Radiology context (52) and the one of mental health (21). Every and any context where legal situations, involvement in medical errors, patients’ adverse events, abuse of substances, physical or mental illnesses and interpersonal conflicts incentive to search for support can be taken into account (31).

Which are the Peer Supporting modalities?

The modalities in which Peer support programmes are carried out are several and diverse. ‘One to one’, namely Peer Support individual meetings between applicant and Peer Supporter (13, 18, 23, 28, 31, 36, 37, 38, 39, 49, 53, 54). Among these, the pilot programme COVID-19 Am I Resilient (cAIR), Peer Support model developed during the first wave of the COVID pandemic to help frontline health workers (49), involves planned meetings through video call platforms. The model suggests informal and emotional support through three modalities: synchronised video presentations, one to one Peer support, resourcing and referral. The programme You Matter, a Peer Support program for “second victims” born at Nationwide Children’s Hospital (18), establishes an initial support inside the operational unit, with meetings delivered by a colleague with a basic training and, if not sufficient, it is the clinical risk unit with trained personnel that intervenes. Finally, a support by a professional can be requested. The ‘victim’ can contact or can be reached telephonically, via e-mail, Internet link, or directly by a Peer Supporter. The programme R.I.S.E, second victim support program for healthcare workers who experience emotional distress as a result of patients adverse events (28), envisages individual meetings with an average duration of 50 minutes. Group Peer Support meetings (20, 21, 22, 24, 26, 30, 34, 41, 43, 44, 45, 48, 50, 51, 52, 55). An example of this model is the Schwartz rounds programme (21, 30, 51) involving a monthly meeting of one hour to discuss, listen and metabolise any personal emotional ailment and reflect on coping strategies. In the Ice Cream Rounds (44), sessions of one hour were conducted by two colleagues in a protected space and were structured in four phases: introduction, check-in, discussion and check-out. It is relevant to mention the articles in which the Peer Support is supplied through video call platforms (56) allowing long distance interactions, such as Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp (22, 24, 55) or Zoom (26). During the Covid-19 pandemic, sanitary operators worked via Microsoft Teams with an online forum accessible 24/24 h (50). CopeColumbia developed a programme with Peer Support groups having a duration of 30 minutes divided based on departments and carried out virtually and with collegial meetings creating Town Halls, namely thematic discussion with back and forth of 30/60 minutes. Peer Support groups were managed by psychiatrists or psychotherapists and some moderators (24).

What is the diffusion and the development of Peer Support in the national and international scenario?

The USA represent the main source of studies and operating Peer Support programmes among healthcare workers. In 2008, the creation of the ‘Center for Professionalism and Peer Support’ at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) in Boston, made the USA the leading state in the sector (54). The programme R.I.S.E, elaborated by the John Hopkins school of Medicine in Baltimore, was applied in 30 different US hospitals with excellent results and was implemented in similar academic medical centres as well (29, 17). From the research, Canadian Peer Support programmes emerged in the emergency medicine wards, known as Ice Cream Rounds (44). In the UK, Schwartz Rounds spread in over 116 hospitals and were then exported in the USA and in Canada (21). In Australia and New Zealand, the programme Hand-n-Hand developed a service guaranteeing even Peer Supporters training (22). Some publications also originate from Sweden and China. Only one study on Peer support in the field of territorial emergency comes from Italy (1).

Conclusions

This scoping review explored the present knowledge in literature related to the concept of Peer Support. Indeed, healthcare workers find relief in discussing with a recognised ‘Peer’ or with colleagues (16). This mutual support in the sanitary field is known with the term Peer Support, which includes the task of listening and providing active support normalising stress reactions, through psychoeducation and the identification of potential worsening symptoms (57). We hence infer the idea that is important to find structured and Peer Support interventions among sanitary professionals in the hospital and extra-hospital context. From the 49 articles analysed, it can be affirmed that Peer Support, notwithstanding the ongoing lack of specific guidelines, represents an organisational change towards a sharing and welcoming culture, an acceptance of our fallible human nature, a psychological safety culture where it is possible to learn from our own errors. The beauty of these (non-therapeutic) programmes lies in Peers’ credibility, in the immediate availability, in the voluntary access and in the confidentiality (27, 29). For organisations, the creation of this kind of programmes would uniquely consists in the training for Peer Supporters, training which, from our research, would possibly require the identification of a dedicated space, of subjects apt to be Peer Supporter and of training meetings of some hours repeated during time in order to acquire specific techniques and methodologies constituting the necessary instruments to conduct a helping relationship (10). In the international scenario, as already stated in the data analysis data section, the USA represents the main source of studies. Already in 2008, with the creation of the Center for Professionalism and Peer Support at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) of Boston, Jo Shapiro promoted support programmes and healthcare workers’ well being, thus making the USA the leading state in the sector (54). In the Italian context, the only reference we could find are the programmes carried out by the A.R.E.U. (Agenzia Regionale Emergenza Urgenza) Lombardy, well structured, but of which there is no scientific publication. As for the limits of our study, we first and foremost recommend the necessity to conduct further researches or studies with the aim of objectively determining the pre- and post-intervention benefits. Moreover, for the future we hope that more and more programmes will be activated in the single working realities and, why not, for the creation of guidelines for the organisation of Peer Support programmes as well.

Conflict of Interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- Carvello M, Zanotti F, Rubbi I, Bacchetti S, Artioli G, Bonacaro A. Peer-support: a coping strategy for nurses working at the Emergency Ambulance Service. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2019 Nov 11;90(11-S):29–37. doi: 10.23750/abm.v90i11-S.8923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors CA, Dukhanin V, March AL, Parks JA, Norvell M, Wu AW. Peer support for nurses as second victims: Resilience, burnout, and job satisfaction. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2020 Feb 1;25(1):22–8. [Google Scholar]

- Woo T, Ho R, Tang A, Tam W. Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;123:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GS, Di Nota PM, Groll D, Carleton RN. Peer Support and Crisis-Focused Psychological Interventions Designed to Mitigate Post-Traumatic Stress Injuries among Public Safety and Frontline Healthcare Personnel: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Oct 20;17(20) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementi S. Il Peer Support in contesti sanitari: un’indagine esplorativa in tre reparti ospedalieri [Peer Support in healthcare settings: an exploratory survey in three hospital departments]. Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milano. 2018 Available from: http://tesionline.unicatt.it. (Accessed on May, 24th, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Dennis CL. Peer support within a health care context: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003 Mar;40(3):321–32. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(02)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization WH. Milestones in health promotion: statements from global conferences. World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://who.int. Reference number: WHO/NMH/CHP/09.01. (Accessed on Sep, 8th, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J. The Historical and Philosophical Development of Peer-Run Support Programs. Our Own Together Peer Programs People Ment Illn. 2005:17–64. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon P. Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;27(4):392–401. doi: 10.2975/27.2004.392.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbuto R, Ferrarese V, Griffo G, Napolitano E, Spinuso G. Consulenza alla pari. Da vittime della storia a protagonisti della vita [Peer counselling. From victims of history to protagonists of life] Comunità Edizioni, Lamezia Terme. 2012:70–89-92. [Google Scholar]

- Mead S, Hilton D, Curtis L. Peer support: a theoretical perspective. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2001;25(2):134–41. doi: 10.1037/h0095032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolley JS, Foroushani PS. What do we know about one-to-one peer support for adults with a burn injury? A scoping review. J Burn Care Res Off Publ Am Burn Assoc. 2014 Jun;35(3):233–42. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182957749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro J, Galowitz P. Peer Support for Clinicians: A Programmatic Approach. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2016 Sep;91(9):1200–4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane MA, Newman BM, Taylor MZ, et al. Supporting Clinicians After Adverse Events: Development of a Clinician Peer Support Program. J Patient Saf. 2018 Sep;14(3):e56–60. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuliani A, De Marzi K. Il peer supporter: un modello da conoscere e su cui riflettere [The peer supporter: a model to know and to reflect on]. PdE Rivista di psicologia applicata all’emergenza, alla sicurezza e all’ambiente. 2006;6:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Vinson AE, Randel G. Peer support in anesthesia: turning war stories into wellness. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2018 Jun;31(3):382–7. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu AW, Connors C, Everly GSJ. COVID-19: Peer Support and Crisis Communication Strategies to Promote Institutional Resilience. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jun 16;172(12):822–3. doi: 10.7326/M20-1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merandi J, Liao N, Lewe D, et al. Deployment of a Second Victim Peer Support Program: A Replication Study. Pediatr Qual Saf. 2017 Jun 21;2(4):e031. doi: 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI. 2020 [Internet]. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. (Accessed on Sep, 29th, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Albott CS, Wozniak JR, McGlinch BP, Wall MH, Gold BS, Vinogradov S. Battle Buddies: Rapid Deployment of a Psychological Resilience Intervention for Health Care Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Anesth Analg. 2020 Jul;131(1):43–54. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen D, Spencer G, McEwan K, et al. The Schwartz Centre Rounds: supporting mental health workers with the emotional impact of their work. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29(5):942–52. doi: 10.1111/inm.12729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridson TL, Jenkins K, Allen KG, McDermott BM. PPE for your mind: a peer support initiative for health care workers. Med J Aust. 2021 Jan;214(1):8–11e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villaruz Fisak JF, Turner BS, Shepard K, Convoy SP. Buddy Care, a Peer-to-Peer Intervention: A Pilot Quality Improvement Project to Decrease Occupational Stress Among an Overseas Military Population. Mil Med. 2020 Sep 18;185(9–10):e1428–34. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usaa171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Mayer LES, Glasofer DR, et al. Supporting the well-being of health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The CopeColumbia response. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020 Dec;67:62–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Tao H, Bowers BJ, Brown R, Zhang Y. Influence of Social Support and Self-Efficacy on Resilience of Early Career Registered Nurses. West J Nurs Res. 2018 May;40(5):648–64. doi: 10.1177/0193945916685712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly PD, Davidson M, Dunlop N, et al. Well-Being During Coronavirus Disease 2019: A PICU Practical Perspective. Pediatr Crit Care Med J Soc Crit Care Med World Fed Pediatr Intensive Crit Care Soc. 2020 Aug;21(8):e584–6. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt SD, Jachna BR. Care of the clinician after an adverse event. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2015 Feb;24(1):54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edrees H, Connors C, Paine L, Norvell M, Taylor H, Wu AW. Implementing the RISE second victim support programme at the Johns Hopkins Hospital: a case study. BMJ Open. 2016 Sep 30;6(9):e011708. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors C, Wu AW. RISE: An Organized Program to Support Health Care Workers. Qual Manag Health Care. 2020 Mar;29(1):48–9. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0000000000000233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garros D, Austin W, Dodek P. How Can I Survive This?: Coping During Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. Chest. 2021 Apr;159(4):1484–92. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu YY, Fix ML, Hevelone ND, et al. Physicians’ needs in coping with emotional stressors: the case for peer support. Arch Surg Chic Ill 1960. 2012 Mar;147(3):212–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronqvist A, Lützén K, Nyström M. Nurses’ lived experiences of moral stress support in the intensive care context. J Nurs Manag. 2006 Jul;14(5):405–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2934.2006.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winning AM, Merandi JM, Lewe D, et al. The emotional impact of errors or adverse events on healthcare providers in the NICU: The protective role of coworker support. J Adv Nurs. 2018 Jan;74(1):172–80. doi: 10.1111/jan.13403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slykerman G, Wiemers MJ, Wyssusek KH. Peer support in anaesthesia: Development and implementation of a peer-support programme within the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Department of Anaesthesia and Perioperative Medicine. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2019 Oct 29;47(6):497–502. doi: 10.1177/0310057X19878450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatt TE, Sachs JF, Huang CC, Pilarski AM. Building a Program of Expanded Peer Support for the Entire Health Care Team: No One Left Behind. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2021 Dec;47(12):759–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2021.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton A. Mitigating burnout and enhancing wellness in anesthesiologists: individual interventions, wellness programs, and peer support. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2021 Oct 1;59(4):73–80. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0000000000000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyser EA, Weir LF, Valdez MM, Aden JK, Matos RI. Extending Peer Support Across the Military Health System to Decrease Clinician Burnout. Mil Med. 2020 doi: 10.1093/milmed/usaa225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadel AL, Barbach N, Fish JD. How I approach peer support in pediatric hematology/oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. agosto 2020;67(8):e28297. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SD. The Pandemic’s Toll-A Case for Clinician Support. Mo Med. febbraio 2021;118(1):45–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch IM, Moretti F, Campagna I, et al. Promoting the Psychological Well-Being of Healthcare Providers Facing the Burden of Adverse Events: A Systematic Review of Second Victim Support Resources. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet] 2021;18(10) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105080. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/10/5080. (Accessed on Dec, 28th, 2021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster MA. Creating the Hematology/Oncology/Stem Cell Transplant Advancing Resiliency Team: A Nurse-Led Support Program for Hematology/Oncology/Stem Cell Transplant Staff. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs Off J Assoc Pediatr Oncol Nurses. 2021 Oct;38(5):331–41. doi: 10.1177/10434542211011046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez LT, Candilis PJ, Arnstein F, et al. Effectiveness of a Unique Support Group for Physicians in a Physician Health Program. J Psychiatr Pract. 2016 Jan;22(1):56–63. doi: 10.1097/PRA.0000000000000121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunasingam N, Burns K, Edwards J, Dinh M, Walton M. Reducing stress and burnout in junior doctors: the impact of debriefing sessions. Postgrad Med J. 2015 Apr;91(1074):182–7. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder-Sprackman S, Kumar T, Gerin-Lajoie C, Kilvert M, Sampsel K. Ice cream rounds: The adaptation, implementation, and evaluation of a peer-support wellness rounds in an emergency medicine resident training program. CJEM. 2018 Sep;20(5):777–80. doi: 10.1017/cem.2018.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson U, Bergström G, Samuelsson M, Asberg M, Nygren A. Reflecting peer-support groups in the prevention of stress and burnout: randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2008 Sep;63(5):506–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow E, Call M, Marcus R, Locke A. Focus on the Quadruple Aim: Development of a Resiliency Center to Promote Faculty and Staff Wellness Initiatives. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018 May;44(5):293–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinks D, Warren-James M, Katsikitis M. Does a peer social support group intervention using the cares skills framework improve emotional expression and emotion-focused coping in paramedic students? Australas Emerg Care. 2021 Dec 1;24(4):308–13. doi: 10.1016/j.auec.2021.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson CF. Peer-supported storytelling for grieving pediatric oncology nurses. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs Off J Assoc Pediatr Oncol Nurses. 2008 Jun;25(3):148–63. doi: 10.1177/1043454208317236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin EW, Rassman A. cAIR: Implementation of peer response support for frontline health care workers facing the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Work Health Care. 2021;60(2):177–86. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2021.1904321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C, Oyebode J, Bicknell S, Webster N, Bentham P, Smythe A. Exploring newly qualified nurses’ experiences of support and perceptions of peer support online: A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2021 Oct;30(19–20):2924–34. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David E, DePierro JM, Marin DB, Sharma V, Charney DS, Katz CL. COVID-19 Pandemic Support Programs for Healthcare Workers and Implications for Occupational Mental Health: A Narrative Review. Psychiatr Q. 2021 Oct 4:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s11126-021-09952-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dungey G, Neser H, Sim D. New Zealand radiation therapist_perceptions of peer group supervision as a tool to reduce burnout symptoms in the clinical setting. J Med Radiat Sci. 2020;67:225–32. doi: 10.1002/jmrs.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce SM, Conaglen HM, Conaglen JV. Burnout in physicians: a case for peer-support. Intern Med J. 2005 May;35(5):272–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2005.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro J, Whittemore A, Tsen LC. Instituting a culture of professionalism: the establishment of a center for professionalism and peer support. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2014 Apr;40(4):168–77. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(14)40022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan S, Bryson E, Phillips A, Nash P. 1413 Piloting a virtual ‘safe space’ for facilitated peer support discussion. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106(Suppl 1):A361–2. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira L, Radovic T, Haykal KA. Peer support programs in the fields of medicine and nursing: a systematic search and narrative review. Can Med Educ J. 2021 Jun;12(3):113–25. doi: 10.36834/cmej.71129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Buschbach S, van der Meer CAI, Dijkman L, Olff M, Bakker A. Web-Based Peer Support Education Program for Health Care Professionals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2020 Apr;46(4):227–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2019.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]