Abstract

Interactions between CD40 expressed on macrophages and CD40 ligand expressed on T lymphocytes can be an important signal for optimal macrophage activation. Previous studies have demonstrated that the optimal response against certain intracellular pathogens (e.g., Crytosporidium and Leishmania spp.) by macrophages requires CD40-CD40 ligand interactions. However, this finding is not universal, since two recent reports utilizing CD40 knockout mice have shown no such contribution to the protective immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Histoplasma capsulatum. We demonstrate here that CD40-CD40 ligand interactions are significant events in the protective response against the intracellular pathogen Salmonella dublin in normal mice but not for animals genetically deficient in CD40 ligand expression. Treating BALB/c mice exogenously with a CD40 agonist (i.e., soluble trimeric CD40 ligand) increased resistance against a lethal, orally administered dose of S. dublin. Conversely, in vivo administration of a monoclonal antibody against CD40 ligand to block endogenous CD40-CD40 ligand interactions resulted in a decreased resistance to salmonellosis. In contrast, CD40 ligand knockout mice demonstrated no increased susceptibility to salmonellosis. In vitro treatment of Salmonella-infected macrophages from BALB/c mice with soluble trimeric CD40 ligand resulted in an elevated production of interleukin 12p70 by these cells, suggesting a mechanism whereby CD40-CD40 ligand interactions might enhance protective immune responses to this pathogen. Taken together, these studies strongly suggest that CD40-CD40 ligand interactions in normal mice play an important protective role in immune responses against the gram-negative, intracellular pathogen S. dublin.

Macrophages express CD40, and ligation of this cell surface molecule by interaction with T-lymphocyte-expressed CD40 ligand can augment macrophage responses. For example, CD40-CD40 ligand interactions augment cytokine expression (2, 21, 32), most notably interleukin 12 (IL-12) secretion (3, 7, 10, 18–20, 29). In addition, ligation of CD40 on macrophages has also been reported to modulate the production of reactive nitrogen intermediates (31), augment expression of matrix metalloproteinases (24), increase tumoricidal activity (1), and upregulate expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1, LFA-3, B7-2, and major histocompatibility complex molecules (21).

Taken together, the ability of ligated CD40 to augment macrophage activity suggested that this molecule might be an important target for affecting macrophage-mediated responses in vivo. Such a suggestion received support from the finding that CD40-CD40 ligand interactions were necessary for optimal protective responses against the intracellular pathogens Leishmania spp. (7, 13, 15, 17, 30) and from the observation that patients who do not express functional CD40 ligand are susceptible to the intracellular pathogens Pneumocystis carinii (27) and Cryptosporidium parvum (14).

However, the relative importance of CD40-CD40 ligand interactions in the protective responses against intracellular pathogens may not be universal. Two recent investigations have suggested that susceptibility to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (8) or Histoplasma capsulatum (33) infection was not significantly different between mice genetically deficient in CD40 ligand expression and normal, control mice.

Thus, it might be suggested that CD40-CD40 ligand interactions are preferentially important in certain intracellular microbial infections but not in others. No studies to date have been performed to address whether ligation of CD40 is an important event in the protective response against intracellular, gram-positive or -negative bacterial infections. Furthermore, it is not clear if CD40-CD40 ligand interactions will be an important mechanism for protection for pathogens which invade the gut mucosa following oral inoculation. In the present study, we have investigated the contribution of CD40-CD40 ligand interactions in mounting a protective cellular immune response against orally inoculated Salmonella dublin. In vivo treatment of normal BALB/c mice with the agonist trimeric CD40 ligand decreased susceptibility, while administration of an anti-CD40 ligand antibody antagonist increased susceptibility to S. dublin. Conversely, mice genetically deficient in the expression of CD40 ligand were as susceptible to salmonellosis as were matched wild-type control animals. As such, the present results suggest a significant role for CD40-CD40 ligand interactions in resistance to this intracellular pathogen in normal mice but not in CD40 ligand knockout mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vivo treatment of BALB/c mice.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of exogenous ligation of CD40 for survival against a lethal oral dose of Salmonella, groups of BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories; 18 to 20 g) were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with soluble trimeric CD40 ligand (Immunex Corp., Seattle, Wash.) in 500 μl of saline containing 0.3% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Each mouse received 25 μg of soluble trimeric CD40 ligand per day on day −2, day −1, day 0, day +1, day +2, and day +4. Groups of control mice received only 500 μl of saline containing 0.3% BSA on the same days. Treatment with soluble trimeric CD40 ligand was selected since this ligand is an agonist and mimics the responses observed when macrophages interact with CD40 ligand present on activated T lymphocytes. The soluble trimeric CD40 ligand was prepared and purified as previously described (12). On day 0, groups of mice were orally inoculated with 107 S. dublin (wild-type strain SL1363) bacteria, and survival was monitored.

To demonstrate the importance of endogenous ligation of CD40 for survival of a lethal, oral dose of Salmonella, groups of BALB/c mice were injected i.p. with a monoclonal rat anti-mouse CD40 ligand antibody (clone M158; Immunex) in 500 μl of saline. Each mouse received 500 μg of monoclonal anti-CD40 ligand antibody per day on day −1, day 0, day +1, day +2, day +3, and day +4. Groups of control mice received 500 μg of normal rat immunoglobulin G (IgG) per day on the same days. The M158 monoclonal antibody was selected for use since it is an antagonist of CD40-CD40 ligand interactions, as has been previously documented (20). On day 0, groups of mice were orally inoculated with 106 S. dublin (wild-type strain SL1363) bacteria.

In vivo treatment of CD40 ligand knockout mice.

CD40 ligand knockout mice (strain C57BL/6J-Tnfsf5tm1Imx) and appropriate control animals (strain C57BL/6J) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). These animals have previously been documented to be genetically deficient in CD40 ligand expression and to display altered immune function as a consequence of a targeted mutation at the gene encoding tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily member 5 (7, 28). On day 0, groups of mice were orally inoculated with 106 S. dublin (wild-type strain SL1363) bacteria, and survival was monitored.

Isolation of murine peritoneal macrophages and in vitro activation.

Elicited peritoneal macrophages were isolated as previously described (5, 6). Briefly, BALB/c mice were injected i.p. with 250 μl of incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). Three days later, the peritoneal cavities were lavaged with RPMI 1640 (7 × 1.5 ml per animal) containing 2% fetal calf serum (FCS) to remove the elicited peritoneal macrophages. After being washed twice in RPMI 1640, cells for use in extended in vitro studies were made to adhere to plastic culture flasks (Corning, Cambridge, Mass.) for 30 to 45 min in RPMI 1640 containing 2% FCS. Nonadherent cells were washed off, and the adherent macrophages were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 2% FCS.

In vitro intracellular infection of macrophages by S. dublin.

Macrophages (2 × 106 per well) were suspended in 0.5 ml of RPMI 1640 containing 15 mM HEPES and 10% FCS in 48-well culture plates. Viable S. dublin wild-type strain SL1363 (Salmonella-to-macrophage ratio of 3:1) was added to the cultures for 90 min at 37°C. Extracellular bacteria were washed off, and plates were then cultured for the duration in medium containing gentamicin to kill any extracellular bacteria. Gentamicin was selected as the antibiotic due to its limited uptake by eukaryotic cells (11).

Quantification of IL-12p70 secretion in culture supernatants.

A capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed to quantify IL-12p70 secretion essentially as described previously (5). Briefly, a capture antibody against murine IL-12p70 (clone G297-289; PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) was applied as a coating to microtiter plates (Nunc Maxisorp, Naperville, Ill.) at 10 μg/ml for 18 h. After washing and blocking with phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% BSA, culture supernatants were added to each well for 2 h. Unbound material was washed off, and biotinylated anti-mouse IL-12p70 antibody (clone C17.8; PharMingen) was added at 5 μg/ml for 2 h. Bound antibody was detected by addition of streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.) for 30 min, followed by addition of nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma Chemical Co.). Absorbances at 405 nm were measured approximately 30 min after substrate addition. A standard curve was constructed by using varying dilutions of mouse recombinant IL-12p70 (PharMingen). The IL-12p70 content of culture supernatants was determined by extrapolation of absorbances to the standard curve. The minimum detectable level in this assay was 30 pg of IL-12p70 per ml.

Statistical analysis.

Results of survival studies were tested statistically by the Kaplan-Meier method (GraphPad Prism; GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif.) to determine survival fractions and the Mantel-Haenszel log rank test to determine P values. In addition, Student’s paired t test or one-way analysis of variance was used as appropriate. Results were determined to be statistically significant when a probability of less than 0.01 was obtained.

RESULTS

CD40-CD40 ligand interactions augment survival of normal mice in salmonellosis.

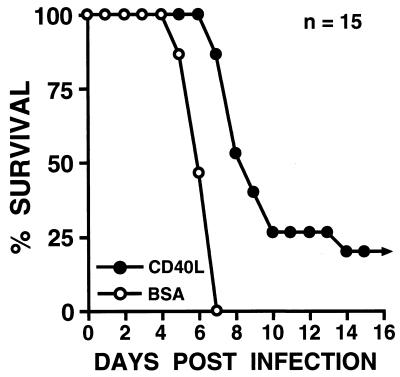

To determine whether activation via CD40 could increase survival after a lethal, oral dose of Salmonella, mice were treated with soluble trimeric CD40 ligand, and their ability to survive an oral inoculation of Salmonella (107 bacteria) was monitored. As shown in Fig. 1, mice treated with a regimen of soluble trimeric CD40 ligand were significantly (P < 0.0001) less susceptible to this pathogen (mean survival, >10.2 ± 0.9 days; n = 15) than those mice treated with BSA (mean survival, 6.3 ± 0.2 days; n = 15). Indeed, the mean survival time for the CD40 ligand treatment group is underestimated since 3 of 15 treated animals were still alive and well 30 days following Salmonella inoculation, when this experimental protocol was terminated.

FIG. 1.

Survival of BALB/c mice treated with soluble trimeric CD40 ligand (CD40L) following oral challenge with Salmonella. Groups of mice (15 per group) were treated i.p. with 25 μg of CD40 ligand or BSA according to the regimen described in Materials and Methods both prior to and following oral challenge with 107 Salmonella bacteria. Results are presented as the percent survival following oral challenge with Salmonella.

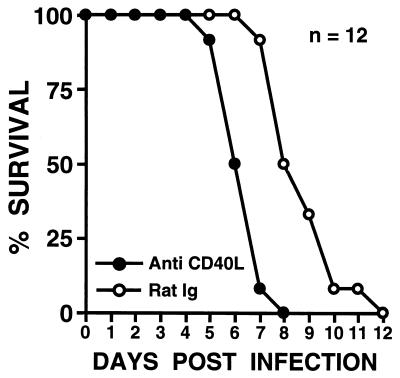

While exogenous stimulation of CD40 with soluble trimeric CD40 ligand increased survival after a lethal dose of Salmonella, it was also important to determine whether endogenous CD40-CD40 ligand interactions were involved in the protective response against Salmonella. To address this question, mice were treated with a monoclonal anti-CD40 ligand antibody which is an antagonist of this interaction (20), and their ability to survive an oral inoculation of Salmonella (106 bacteria) was monitored. A lower dose of Salmonella was selected for use in these studies to accentuate potentially increased susceptibility to salmonellosis in mice treated with the anti-CD40 ligand antibody. As shown in Fig. 2, mice treated with anti-CD40 ligand antibody were significantly (P < 0.0001) more susceptible to an oral challenge of Salmonella (mean survival, 6.3 ± 0.2 days; n = 12) than mice treated with normal rat Ig (mean survival, 8.5 ± 0.4 days; n = 12), suggesting a role for endogenous CD40-CD40 ligand interactions in the protective response against Salmonella.

FIG. 2.

Survival of BALB/c mice treated with anti-mouse CD40 ligand monoclonal antibodies following oral challenge with Salmonella. Groups of mice (12 per group) were treated i.p. with either 0.5 mg of anti-mouse CD40 ligand monoclonal antibody (Anti CD40L) or 0.5 mg of nonspecific rat IgG (Rat Ig) according to the regimen described in Materials and Methods both prior to and following oral challenge with 106 Salmonella bacteria. Results are presented as the percent survival following oral challenge with Salmonella.

CD40 ligand-deficient animals do not demonstrate increased susceptibility to salmonellosis.

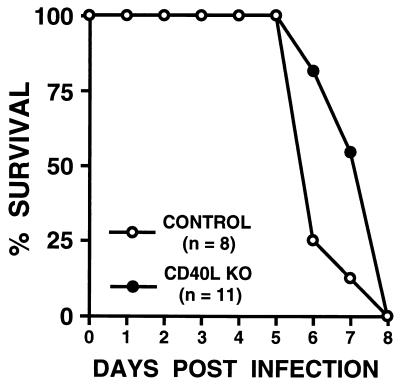

To investigate whether mice genetically deficient in CD40 ligand expression display impaired ability to survive a lethal oral dose of Salmonella, C57BL/6J-Tnfsf5tm1Imx CD40 ligand knockout mice (7, 28) and control C57BL/6J animals were treated with an oral inoculation of Salmonella, and their survival was monitored. As shown in Fig. 3, CD40 ligand knockout mice displayed no significant difference in susceptibility to oral challenge with Salmonella (mean survival, 7.4 ± 0.3 days; n = 11) from that seen with control strain mice (mean survival, 6.4 ± 0.3 days; n = 8). To further investigate the susceptibility of mice genetically deficient in CD40 ligand to oral challenge with Salmonella, the bacterial burdens in the mesenteric lymph nodes and spleens of CD40 ligand-deficient mice and control animals were determined 3 days after oral challenge with 106 Salmonella bacteria. No significant differences in the numbers of CFU of Salmonella from those seen with control strain mice were detected in CD40 ligand knockout mice in either the mesenteric lymph nodes (4.9 × 105 ± 1.2 × 105 CFU/g of tissue in CD40 ligand knockout mice versus 3.0 × 105 ± 0.6 × 105 CFU/g of tissue in control mice) or spleens (0.6 × 105 ± 0.2 × 105 CFU/g of tissue in CD40 ligand knockout mice versus 0.7 × 105 ± 0.2 × 105 CFU/g of tissue in control mice). Taken in concert, these data demonstrate that the congenital absence of CD40-CD40 ligand interactions in the C57BL/6J mice does not impair the ability of these animals to mount protective immune responses to Salmonella.

FIG. 3.

Survival of mice genetically deficient in CD40 ligand expression following oral challenge with Salmonella. Groups of normal mice (CONTROL) (n = 8) and mice genetically deficient in CD40 ligand (CD40L KO) (n = 11) were challenged orally with 106 Salmonella bacteria. Results are presented as the percent survival following oral challenge with Salmonella.

Ligation of CD40 augments the production of IL-12p70 by Salmonella-infected macrophages.

To begin to address the mechanisms by which CD40-CD40 ligand interactions might augment the protective response against Salmonella seen with normal BALB/c mice, we questioned whether ligation of CD40 might augment IL-12 secretion by Salmonella-infected macrophages. This seemed a logical question to address, since it has been convincingly demonstrated elsewhere that exogenous IL-12 production or exogenous IL-12 administration results in increased resistance to a variety of intracellular pathogens including Salmonella (22, 25). The mechanism of such protection appears to be the ability of IL-12 to augment gamma interferon production by NK cells and activated CD4+ T lymphocytes, which can subsequently activate macrophages to destroy the invading intracellular pathogen (22, 25). Importantly, CD40-CD40 ligand interactions have previously been shown to induce IL-12 secretion by macrophages (3, 7, 10, 18–20, 29).

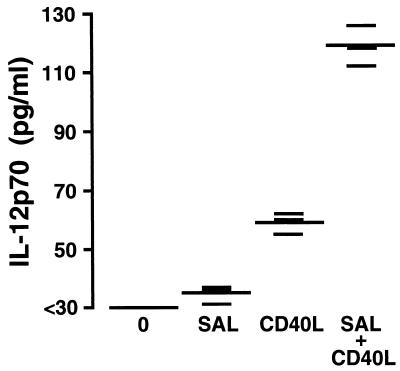

Macrophages from BALB/c mice were cultured in the presence or absence of Salmonella for 90 min prior to the removal of extracellular bacteria and addition of gentamicin. Some of the cultured macrophages were then treated with soluble trimeric CD40 ligand. After 48 h of culture, the supernatants were removed, and the quantity of the bioactive heterodimer of IL-12, IL-12p70, was determined. As shown in Fig. 4, treatment of Salmonella-infected macrophages with soluble trimeric CD40 ligand resulted in a significant (P ≤ 0.01) augmentation of IL-12p70 secretion. The secretion of IL-12p70 from CD40 ligand-treated Salmonella-infected macrophages was significantly greater than that observed for uninfected macrophages treated with CD40 ligand or for macrophages infected with Salmonella only. These results confirm previous reports that ligation of CD40 ligand can augment IL-12p70 secretion (3, 7, 10, 18–20, 29). Furthermore, these results demonstrate that Salmonella-infected macrophages demonstrate enhanced IL-12p70 secretion upon ligation of CD40.

FIG. 4.

Effect of CD40 ligand on secretion of IL-12p70 from Salmonella-infected macrophages from BALB/c mice. Uninfected cells were cultured in medium alone (0) or with recombinant soluble trimeric CD40 ligand (1 μg/ml) (CD40L). Salmonella-infected cells (3:1 ratio of Salmonella bacteria to macrophages) were cultured in medium alone (SAL) or with recombinant soluble trimeric CD40 ligand (1 μg/ml) (SAL + CD40L) as indicated. At 48 h after exposure, the supernatant was removed from each culture and the amount of IL-12p70 present was quantified by a capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. This experiment was performed twice with similar results. Results are shown as triplicate determinations (short bars) with the means indicated (long bars).

DISCUSSION

Animal models and clinical observations have provided mixed results concerning the importance of CD40-CD40 ligand interactions in the protective immune response against intracellular microbial infections. Strong support for an important role for such interactions comes from observations of patients with hyper-IgM syndrome. These individuals do not express CD40 ligand and not only develop infections to encapsulated bacteria due to ineffective Ig production but are also susceptible to the intracellular pathogens P. carinii (27) and C. parvum (14). In support of these clinical observations, mice genetically deficient in CD40 ligand expression have limited T-lymphocyte-dependent macrophage-mediated immune responses (31) and in particular have limited cellular immune responses to the intracellular pathogens Leishmania major (7) and Leishmania amazonensis (29). Furthermore, genetic disruption of CD40 or CD40 ligand expression in mice results in the inability of these animals to clear C. parvum (9). Taken together, these findings provide strong support for CD40-CD40 ligand interactions in the protective immune responses against rather diverse intracellular pathogens.

However, the finding that CD40-CD40 ligand interactions are important in macrophage responses to intracellular infections may not be ubiquitous. Recent studies employing mice genetically deficient in CD40 ligand have shown that such interactions are not essential for protective immune responses against the intracellular pathogens H. capsulatum (23) and M. tuberculosis (8). Mice genetically deficient in CD40 ligand expression were not found to differ significantly in their mortality or IL-12 production when challenged with these microbes (8, 33).

If the results obtained thus far (7–9, 14, 27, 30, 31, 33) are reproducible, they would suggest that distinct differences in pathogenesis by various intracellular microbes dictate whether CD40-CD40 ligand interactions can contribute to protective immune responses. Since no studies to date have investigated the importance of this interaction in intracellular gram-positive or gram-negative bacterial infections, we addressed this question. The present study provides evidence for a significant role for CD40-CD40 ligand interactions in mounting a successful cellular immune response against Salmonella in normal BALB/c mice. Not only was survival augmented in BALB/c mice treated with exogenous soluble trimeric CD40 ligand, but animals were found to be more susceptible to this intracellular pathogen when interactions between CD40 and endogenous CD40 ligand were antagonized by using an anti-murine CD40 ligand monoclonal antibody. On the basis of these data, we suggest that these molecules play an important role in T-cell-dependent activation of Salmonella-infected macrophages.

While the results obtained from soluble CD40 ligand treatment and from anti-CD40 ligand administration support the same conclusion, these experiments have slightly different implications. Administration of anti-CD40 ligand antibodies demonstrated that endogenous CD40-CD40 ligand interactions which could facilitate the protective immune response occurred in vivo during the development of salmonellosis in BALB/c mice. On the other hand, the ability to augment cell-mediated resistance against Salmonella infection by using soluble trimeric CD40 ligand suggests that this exogenous treatment might have therapeutic potential. Furthermore, this result would be consistent with the notion that endogenous CD40-CD40 ligand interactions might not be optimal in infected mice, since it is possible to significantly augment this protective response with trimeric CD40 ligand.

A mechanism of action whereby soluble trimeric CD40 ligand treatment of BALB/c mice augments survival of salmonellosis was suggested by the demonstration that ligation of CD40 on infected macrophages resulted in increased secretion of the bioactive heterodimer IL-12p70 (Fig. 4). Such investigations were a logical starting point for understanding the mechanism of protection, since it is clear that endogenous IL-12 secretion or exogenous IL-12 treatment augments the protective cellular immune response against Salmonella (22, 25). IL-12 is thought to augment gamma interferon production, which can subsequently activate macrophages to destroy intracellular pathogens such as Salmonella (22, 25). Furthermore, ligation of CD40 expressed on macrophages has previously been shown to augment IL-12 production by these cells (3, 7, 10, 18–20, 29). However, it is important to note that there are other potential mechanisms attributed to ligation of CD40 on macrophages which could contribute to the protective response against Salmonella. For example, ligation of CD40 has been shown to enhance the production of nitric oxide (31) and an array of monokines (2, 21, 32) and chemokines (23). More comprehensive studies will be required to determine the precise mechanisms mediating the protective responses following ligation of CD40 on macrophages.

In contrast, CD40 ligand knockout mice from the C57BL/6J background displayed no significant differences either in their survival of an oral challenge with Salmonella or in the bacterial burdens measured in mesenteric lymph nodes and spleens compared with those seen with control strain mice. Together, the present results suggest that the congenital absence of CD40-CD40 ligand interactions in these C57BL mice does not impair their ability to mount protective immune responses to Salmonella. Such data might suggest that the importance of CD40-CD40 ligand interactions for the immune response following salmonellosis is not ubiquitous for all strains of mice, despite the fact that both BALB/c and C57BL mice express the susceptible form of the Ity gene. Alternatively, these results may be indicative of the existence of compensatory mechanisms to combat this intracellular pathogen in these genetically deficient mice. It is important to note that those reports that have previously shown that CD40-CD40 ligand interactions are not essential for certain protective immune responses employed mice genetically deficient in CD40 ligand (8, 33). As such, the present observations illustrate a potential caveat in those studies that exclusively employ such knockout animals and may help to reconcile the disparate reports in the literature as to the relative contribution that such interactions play in protective immune responses to intracellular pathogens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work is supported by grant AI32976 to Kenneth L. Bost from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alderson M R, Armitage R J, Tough T W, Strockbine L, Fanslow W C, Spriggs H. CD40 expression by human monocyte: regulation by cytokines and activation of monocytes by the ligand CD40. J Immunol. 1992;149:1252–1257. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alderson M R, Armitage R J, Tough T W, Strockbine L, Fanslow W C, Spriggs H. CD40 expression by human monocytes: regulation by cytokines and activation of monocytes by the ligand for CD40. J Exp Med. 1993;178:669–674. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balashov K E, Smith D R, Khoury S J, Hafler D A, Weiner H L. Increased interleukin 12 production in progressive multiple sclerosis: induction by activated CD4+ T cells via CD40 ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:599–603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bost K L, Clements J D. In vivo induction of interleukin-12 mRNA expression after oral immunization with Salmonella dublin or the B subunit of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1076–1083. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.1076-1083.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bost K L, Clements J D. Intracellular Salmonella dublin induces substantial secretion of the 40-kilodalton subunit of interleukin-12 (IL-12) but minimal secretion of IL-12 as a 70-kilodalton protein in murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3186–3192. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3186-3192.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bost K L, Mason M J. Thapsigargin and cyclopiazonic acid initiate rapid and dramatic increases of IL-6 mRNA expression and IL-6 secretion in murine peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 1995;155:285–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell K A, Ovendale P J, Kennedy M K, Fanslow W C, Reed S G, Maliszewski C R. CD40 ligand is required for protective cell-mediated immunity to Leishmania major. Immunity. 1996;4:283–289. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campos-Neto A, Ovendale P, Bement T, Koppi T A, Fanslow W C, Rossi M A, Alderson M R. CD40 ligand is not essential for the development of cell-mediated immunity and resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1998;160:2037–2041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosyns M, Tsirkin S, Jones M, Flavell R, Kikutani H, Hayward A R. Requirement for CD40-CD40 ligand interaction for elimination of Cryptosporidium parvum from mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:603–607. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.603-607.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeKruyff R H, Gieni R S, Umetsu D T. Antigen-driven but not lipopolysaccharide-driven IL-12 production in macrophages requires triggering of CD40. J Immunol. 1997;158:359–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elsinghorst E A. Measurement of invasion by gentamicin resistance. Methods Enzymol. 1994;236:405–420. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)36030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fanslow W C, Srinivasan S, Paxton R, Gibson M G, Spriggs M K, Armitage R J. Structural characteristics of CD40 ligand that determine biological function. Semin Immunol. 1994;6:267–278. doi: 10.1006/smim.1994.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferlin W G, von der Weid T, Cottrez F, Ferrick D A, Coffman R L, Howard M C. The induction of a protective response in Leishmania major-infected BALB/c mice with anti CD40 mAb. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:525–531. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199802)28:02<525::AID-IMMU525>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayward A R, Levy J, Facchetti F, Notarangelo L, Ochs H D, Etzioni A, Bonnefoy J Y, Cosyns M, Weinberg A. Cholangiopathy and tumors of the pancreas, liver, and biliary tree in boys with X-linked immunodeficiency with hyper-IgM (XHIM) J Immunol. 1997;158:977–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinzel F P, Rerko R M, Hujer A M. Underproduction of interleukin-12 in susceptible mice during progressive leishmaniasis is due to decreased CD40 activity. Cell Immunol. 1998;184:129–142. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hormaeche C E. Natural resistance to Salmonella typhimurium in different inbred mouse strains. Immunology. 1979;37:311–318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamanaka M, Yu P, Yasui T, Yoshida K, Kawabe T, Horii T, Kishimoto T, Kikutani H. Protective role of CD40 in Leishmania major infection at two distinct phases of cell-mediated immunity. Immunity. 1996;4:275–281. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80435-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato T, Hakamada R, Yamane H, Nariuchi H. Induction of IL-12p40 messenger RNA expression and IL-12 production of macrophages via CD40-CD40 ligand interaction. J Immunol. 1996;156:3932–3938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato T, Yamane H, Nariuchi H. Differential effects of LPS and CD40 ligand stimulations on the induction of IL-12 production by dendritic cells and macrophages. Cell Immunol. 1997;181:59–67. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kennedy M K, Picha K S, Fanslow W C, Grabstein K H, Alderson M K, Clifford K N, Chin W A, Mohler K M. CD40/CD40 ligand interactions are required for T cell-dependent production of interleukin-12 by mouse macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:370–378. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiener P A, Moran-Davis P, Rankin B M, Wahl A F, Aruffo A, Hollenbaugh D. Stimulation of CD40 with purified soluble gp39 induces proinflammatory responses in human monocytes. J Immunol. 1995;155:4917–4925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kincy-Cain T, Bost K L. Increased susceptibility of mice to Salmonella infection following in vivo treatment with the substance P antagonist, Spantide II. J Immunol. 1996;157:255–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kornbluth R S, Kee K, Richman D D. CD40 ligand (CD154) stimulation of macrophages to produce HIV-1-suppressive beta-chemokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5205–5210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malik N, Greenfield B W, Wahl A F, Kiener P A. Activation of human monocytes through CD40 induces matrix metalloproteinases. J Immunol. 1996;156:3952–3960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mastroeni P, Harrison J A, Chabalgoity J A, Hormaeche C E. Effect of interleukin 12 neutralization on host resistance and gamma interferon production in mouse typhoid. Infect Immun. 1996;64:189–196. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.189-196.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramarathinam L, Shaban R A, Neisel D W, Klimpel G R. Interferon-gamma production by gut-associated lymphoid tissue and spleen following oral Salmonella typhimurium challenge. Microb Pathog. 1991;11:347–356. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90020-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramesh N, Fuleihan R, Geha R. Molecular pathology of X-linked immunoglobulin deficiency with normal or elevated IgM (HIGMX-1) Immunol Rev. 1994;138:87–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1994.tb00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Renshaw B R, Fanslow III W C, Armitage R J, Campbell K A, Liggitt D, Wright B, Davison B L. Humoral immune responses in CD40 ligand-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1889–1900. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shu U, Kiniwa M, Wu C Y, Maliszewski C, Vezzio N, Hakimi J, Gately M, Delespesse G. Activated T cells induce interleukin-12 production by monocytes via CD40-CD40 ligand interaction. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1125–1128. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soong L, Xu J C, Grewal I S, Kima P, Sun J, Longley B J, Jr, Ruddle N H, McMahon-Pratt D, Flavell R A. Disruption of CD40-CD40 ligand interactions results in an enhanced susceptibility to Leishmania amazonensis infection. Immunity. 1996;4:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stout R D, Suttles J, Xu J, Grewal I S, Flavell R A. Impaired T cell-mediated macrophage activation in CD40 ligand-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1996;156:8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner D H, Jr, Stout R D, Suttles J. Role of the CD40-CD40 ligand interaction in CD4+ T cell contact-dependent activation of monocytic interleukin-1 synthesis. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:3148–3154. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou P, Seder R A. CD40 ligand is not essential for induction of type 1 cytokine responses or protective immunity after primary or secondary infection with Histoplasma capsulatum. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1315–1324. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]