Abstract

The identification of genes with increased expression in vivo may lead to the identification of novel or unrecognized virulence traits and/or recognition of environmental signals involved in modulating gene expression. Our laboratory is studying an extraintestinal isolate of Escherichia coli as a model pathogen. We had previously used human urine ex vivo to identify the unrecognized urovirulence genes guaA and argC and to establish that arginine and guanine (or derivatives) were limiting in this body fluid (T. A. Russo et al., Mol. Microbiol. 22:217–229, 1996). In this study, we have continued with this approach and identified three additional genes that have increased expression in human urine relative to Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. Expression of ure1 (urine-responsive element) is increased a mean of 47.6-fold in urine but completely suppressed by exogenous glucose. This finding suggests that ure1 is regulated by catabolite repression and that limiting glucose in urine is a regulatory signal. ure1 is present in the E. coli K-12 genome, but its function is unknown. Although disruption of ure1 results in diminished growth in human urine, limiting concentrations of amino acids, nucleosides, or iron (Fe), or changes in osmolarity or pH do not affect the expression of ure1. Therefore, Ure1 appears to have a role independent of the synthesis or uptake of these nutrients and does not appear to be involved in osmoprotection. iroNE. coli is a novel E. coli gene with 77% DNA homology to a catecholate siderophore receptor gene recently identified in Salmonella. Its expression is increased a mean of 27.2-fold in urine and is repressed by exogenous Fe and a urinary pH of 5.0. This finding supports the contention that Fe is a limiting element in urine and that alteration of pH can affect gene expression. It is linked to the P-pilus (prs) and F1C fimbrial (foc) gene clusters on a pathogenicity island and appears to have been acquired by IS1230-mediated horizontal transmission. The homologous iroNE. coli sequence is significantly more prevalent in urinary tract and blood isolates of E. coli compared to fecal isolates. Last, the expression of ArtJ, an arginine periplasmic binding protein, is increased a mean of 16.6-fold in urine. This finding implicates arginine concentrations as limited in urine and, in combination with previous data demonstrating that argC is important for urovirulence, suggests that the ability of E. coli to synthesize or acquire arginine is important for urovirulence. ure1, iroNE. coli, and artJ all have increased expression in human blood and ascites relative to LB medium as well. The identification of these genes increases our understanding of regulatory signals present in human urine, blood, and ascites. Ure1, IroNE. coli, and ArtJ also warrant further evaluation as virulence traits both within and outside the urinary tract.

The majority of urinary tract infections (UTI) are caused by extraintestinal isolates of Escherichia coli. Eighty to ninety percent of ambulatory UTI, 73% of UTI in individuals over 50, and 25% of nosocomial UTI are due to extraintestinal strains of E. coli (11, 21, 47). Uncomplicated urethritis or cystitis occurs most commonly. However, more severe sequelae of UTI include pyelonephritis, intrarenal and perinephric abscess, and bacteremia with or without septic shock. E. coli is the most common cause of gram-negative bacteremia, and the urinary tract is the source for 50 to 70% of these episodes (9, 13, 14, 27). Therefore, it is clear that despite effective antimicrobial therapy, UTI due to E. coli causes considerable morbidity and mortality, resulting in a significant medical-economic burden to our national health care system (21, 33). By understanding which bacterial determinants are important in the pathogenesis of UTI, we will be able to logically develop novel, effective strategies for the prevention and treatment of the infections. This need becomes even more pressing with the increasing number of reports describing the emergence of antimicrobial-resistant strains of E. coli (12, 15, 24, 34).

The human urinary tract represents a unique host environment in which E. coli can grow and survive better than the other numerous members of the human bowel and vaginal flora. For optimal adaptation to the conditions of the urinary tract, it is logical to assume that a variety of genes and/or their products are differentially expressed within this host environment. Although a number of virulence factors have been identified in extraintestinal isolates of E. coli (10, 18, 30) and a substantial body of information has been generated on the pathogenesis of UTI, our understanding of factors that are differentially expressed within the urinary tract and the environmental signals that mediate their increased expression is limited (8, 29). Urine, cellular components in the urinary tract, or parts thereof, however, are likely candidates to serve as signals for the increased expression of a variety of genes important in various aspects of uropathogenesis.

A recent report has suggested that P-pilus-mediated attachment to human erythrocytes or globoside, both of which contain the PapG receptor Gal(α1-4)Gal, results in a 3.5-fold induction of the sensor-regulator protein AirS. This protein is essential for the iron starvation response (51). Although it was not directly demonstrated in this study, it is reasonable to assume that P-pilus-mediated adherence to cells or their components within the urinary tract will also result in induction of airS. Our laboratory has previously identified argC as having a greater than 10-fold increase in expression (relative to Luria-Bertani [LB] medium) in every human urine sample evaluated. The addition of exogenous arginine abolished this increase in expression. Further, an isogenic derivative with a disruption of argC demonstrated significantly decreased growth in human urine ex vivo and diminished urovirulence in vivo in a mouse model of ascending, unobstructed UTI compared to its wild-type parent (37). This finding established that the identification of genes with increased expression in human urine ex vivo was a potential means to identify additional urovirulence traits and/or recognize environmental signals involved in modulating virulence gene expression.

To identify such genes, TnphoA′1 and TnphoA mutant libraries of a model extraintestinal E. coli pathogen (CP9) were screened for mutant derivatives with increased lacZ or phoA activity in the presence of urine relative to LB medium. In this report, we describe the identification and initial characterization of one lacZ gene fusion and two phoA gene fusions with increased expression in human urine relative to LB medium. We also describe studies that evaluate potential environmental signals responsible for their differential expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The model pathogen CP9 is an E. coli blood isolate cultured from a patient with sepsis hospitalized at the National Institutes of Health and is being used as a model pathogen. It is characterized by growth in 80% normal human serum, β-hemolysis, no known antibiotic resistance, O4/K54/H5 serotype, P pilus (class I PapG adhesin), Prs pilus (class III PapG adhesin), type 1 pilus, possession of a 36.2-kb cryptic plasmid (pJEG), and an aerobactin-minus genotype. By DNA dot blot assays, it has also been determined to be sfa, ompT, cnf-1, and drb positive (20, 36). It is highly virulent in a mouse UTI infection model (35). Recent studies have established that CP9 is part of a widely disseminated group of uropathogens that are characterized, in part, by possessing group three capsules, the O4 specific antigen, and class 1 and class 3 Pap adhesins (20, 22).

TABLE 1.

E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or other relevant characteristics | Derivation | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | |||

| CP9 | O4/K54/H5 | Clinical blood isolate | 36 |

| CP9.I-2 | ure1::TnphoA′1 Tn10tet::proΔlacZ, active lacZ fusion | Kanr exconjugant of BW16948 × CP917 | 37, this study |

| CPI-2 | ure1::TnphoA′1 | T4 (CP9.I-2) × CP9 | This study |

| CP9.45 | iroNE. coli::TnphoA, active TnphoA fusion | Kanr exconjugant of CP9/pRT291 × MM294/pPH1J1 | 36, this study |

| CP45 | iroNE. coli::TnphoA | T4 (CP9.45) × CP9 | This study |

| CP9.82 | iroNE. coli::TnphoA, active TnphoA fusion | Kanr exconjugant of CP9/pRT291 × MM294/pPH1J1 | 36, this study |

| CP82 | iroNE. coli::TnphoA | T4 (CP9.82) × CP9 | This study |

| CP9.274 | artJ::TnphoA, active TnphoA fusion | Kanr exconjugant of CP9/pRT291 × MM294/pPH1J1 | 36, this study |

| CP274 | artJ::TnphoA | T4 (CP9.274) × CP9 | This study |

| XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac (F+proAB lacIq ZΔM15 Tn10) | Stratagene | |

| Plasmids | |||

| pCPI-2.1 | 8.8-kb SalI/EcoRI fragment from CPI-2 containing the leftward 5.0 kb of TnphoA (active fusion) and a portion of ure1 cloned into pBSII SK(−) | This study | |

| p45.1 | 21-kb SalI/SacI fragment from CP45 containing the leftward 5.0 kb of TnphoA (active fusion) and a portion of iroNE. coli cloned into pBSII SK(−) | This study | |

| p45.3 | 22-kb ClaI/XbaI fragment from CP45 containing the rightward 6.7 kb of TnphoA (nonfusion) and a portion of iroNE. coli cloned into pBSII SK(−) | This study | |

| p82.1 | 22-kb BamHI/SacI fragment from CP82 containing the leftward 5.0 kb of TnphoA (active fusion) and a portion of iroNE. coli cloned into pBSII SK(−) | This study | |

| p274.1 | 7.4-kb BamHI/XbaI fragment from CP274 containing the leftward 5.0 kb of TnphoA (active fusion) and a portion of artJ cloned into pBSII SK(−) | This study |

All strains were maintained at −80°C in 50% LB medium and 50% glycerol. LB broth consisted of 5 g of yeast extract, 10 g of tryptone, and 10 g of NaCl per liter. Incubations were performed at 37°C unless otherwise described. For plates, 15 g of Bacto Agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) was added per liter, and kanamycin (40 μg/ml) or ampicillin (200 μg/ml) (Amresco, Solon, Ohio) was added where appropriate. Urine agar plates were made as described elsewhere (37), using pooled urine from five healthy donors who did not have a history of UTI. For gene expression studies, we used urine that was (i) fresh unfiltered, (ii) fresh and filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter, or (iii) filtered and stored at 4°C. Urine samples were obtained from individuals who have had or never had a UTI.

Transposon mutagenesis and mutant library construction. (i) TnphoA′1 mutagenesis.

A CP9 derivative (CP917) possessing a lacZ deletion was constructed and subsequently used as a recipient for transposon mutagenesis as described previously (37). Approximately 5,000 transposon mutants containing TnphoA′1 (lacZ operon fusion element [48]) were pooled, resulting in the generation of a TnphoA′1 mutant library.

(ii) TnphoA mutagenesis.

To identify genes with increased expression in human urine ex vivo that coded for extracytoplasmically located gene products, random TnphoA mutagenesis was performed on CP9. A previously constructed TnphoA mutant library consisting of 527 CP9 derivatives that contained active TnphoA fusions (36) was used in this study.

Identification of genes with increased expression in human urine.

The random TnphoA′1 mutant library was screened to identify genes that coded for cytoplasmically located gene products which had increased expression in human urine ex vivo. Transposon mutants were initially plated on human urine agar plates containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside (XG; 40 μg/ml), an indicator of β-galactosidase activity, and kanamycin (40 μg/ml) (37). Mutants with active fusions and apparent high-level activity on urine plates (as manifested by the relative blue color of colonies) were gridded onto LB plates plus XG and screened for those with low-level activity on that medium. The TnphoA mutant library was screened to identify genes that coded for extracytoplasmically located gene products which had increased expression in human urine ex vivo. The initial screen was performed in a similar fashion except that 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate-p-toluidine salt (XP), an indicator of alkaline phosphatase activity, was the colorimetric substrate used. Mutants that appeared to have increased expression via these qualitative screens were confirmed with quantitative assays.

Quantitative alkaline phosphatase and β-galactosidase assays.

For urine and LB assays, quantitative alkaline phosphatase and β-galactosidase assays were performed as previously described (37, 39). In brief, CP9 and each of its mutant derivatives were grown overnight in LB broth and human urine. Preliminary experiments for each of the genes of interest in this report established that expression was the same for cells grown to log phase and those grown to stationary phase. Cells were then washed and permeabilized, and either p-nitrophenyl phosphate or o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranosidose was added for detection of alkaline phosphatase or β-galactosidase activity, respectively. To control for both endogenous bacterial alkaline phosphatase or β-galactosidase activity and any activity from the growth medium (e.g., urine) that may persist despite washing, alkaline phosphatase or β-galactosidase activity from CP9 was subtracted from the measured activity of its mutant derivatives.

Genetic and DNA manipulations and analyses.

Transduction of a transposon insertion back into the wild-type strain CP9 was accomplished by using the bacteriophage T4 (36). Whole-cell DNA preparation, restriction enzyme (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.)-mediated DNA digestion, and Southern hybridization using PCR-generated radioactive probes were performed as described elsewhere (36, 38). Primers 63 (5′ GATCAAGAGACAGGATGA 3′) and 64 (5′ TGATCCTCGCCGTACTGC 3′) were used to amplify 4.0-kb internal fragments of TnphoA (contained in pRT291 [36]), which were used to probe for TnphoA′1 and TnphoA insertions, respectively. Southern analysis of BglII-digested whole-cell DNA containing TnphoA′1 produces a 1.2-kb internal fragment and a single variable junction fragment per copy, and TnphoA produces a 2.8-kb internal fragment and one variable junction fragment per copy. Lipopolysaccharide, capsular polysaccharide, and outer membrane protein profiles were determined as described elsewhere (38).

Construction of subclones of ure1, iroNE. coli, and artJ.

Subclones of the gene loci 5′ to the TnphoA insertions in CP9.45 (iroNE. coli), CP9.82 (iroNE. coli), CP9.274 (artJ), and the TnphoA′1 insertion in CPI-2 (ure1) were obtained by restricting whole-cell DNA with BamHI or SalI, which recognizes a site located 3′ to the kanamycin resistance gene in TnphoA and TnphoA′1, plus either EcoRI (CPI-2), SacI (CP45 and CP82), or XbaI (CP274), which does not have a restriction site within TnphoA or TnphoA′1. Ligation of this restriction into pBluescript II (pBSII) SK(−), electroporation into Escherichia coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), and selection of ampicillin (200 μg/ml) and kanamycin (40 μg/ml)-resistant transformants resulted in the identification of the subclones p45.1, p82.1, p274.1, and pCPI-2.1 (Table 1). A subclone of the iroNE. coli gene locus 3′ to the TnphoA insertion in CP9.45 was obtained by restricting whole-cell DNA with ClaI, which recognizes a site 5′ to the kanamycin resistance gene in TnphoA, and XbaI, which does not possess a restriction site within TnphoA. Ligation of this restriction into pBSII SK(−), electroporation into XL1-Blue (Stratagene), and selection of ampicillin- and kanamycin-resistant transformants resulted in the identification of subclone p45.3.

DNA sequencing, determination of TnphoA insertion sites, and gene analysis.

DNA sequence was determined by the dideoxy-chain termination method of Sanger et al. (42), using the gene subclones p45.1, p45.3, p82.1, p274.1, and pCPI-2.1 as the DNA templates. DNA sequencing of the gene subclones p45.1, p82.1, p274.1, and pCPI-2.1 initially used a TnphoA fusion joint primer (5′ AATATCGCCCTGAGC 3′) which established the location for a given TnphoA insertion. Sequencing of the gene subclone p45.3 initially used the TnphoA primer (5′ CATGTTAGGAGGTCACAT 3′). Subsequent DNA sequence was determined with primers derived from the deduced sequences of the gene subclones. A consensus sequence for iroNE. coli was generated by assembling and editing the DNA sequence obtained from 34 overlapping but independent sequencing reactions, using AssemblyLIGN 1.0.2 (Oxford Molecular Group, Beaverton, Oreg.). Both strands of the gene sequences described in this report were sequenced. Sequence analysis, comparisons, and CLUSTAL alignments were performed, in part, with MacVector (version 6.0; Oxford Molecular Group). Comparisons were also performed via BLAST analysis of the nonredundant GenBank, EMBL, DDBJ, and PDB sequences. SignalP V1.1 (31) was used for identification of signal sequences.

Dot blot hybridization assays.

DNA was prepared from relevant strains by boiling cells from overnight growth in LB medium (1 ml concentrated to 200 μl of sterile H2O) at 105°C for 10 min. The supernatant was saved and used for analysis. Nytran membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.) were prewet in 6× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) for 10 min and dotted with 3 μl of denatured DNA preparation from each strain in triplicate. The membrane was subsequently placed on filter paper saturated with denaturing solution (0.4 N NaOH, 0.6 M NaCl) followed by neutralizing solution (1.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M Tris HCl [pH 7]) for 1 min each, then air dried and UV cross-linked with 1,200 J (UV Stratalinker 2400; Stratagene). Primers 192 (5′ GACGCCGACATTAAGACG 3′) and 197 (5′ AAGTCAAAGCAGGGGTTGC 3′) were used to amplify a 0.67-kb internal fragment of iroNE. coli (contained in p45.3) that did not share any homology with fepA. Aqueous hybridization was performed under high-stringency conditions (65°C) as described elsewhere (38). Results were scored as either 0 (no hybridization), 1+, or 2+. Under these conditions, the negative control strains (HB101 and XL1-Blue) were consistently scored as 0 and the positive control strain CP9 was scored as 2+. Experimental strains consisted of seven groups: group 1, 14 unique fecal isolates that had been previously established not to contain pap, hly, or cnf-1 (19); group 2, 5 unique fecal isolates that possessed some combination of pap, hly, or cnf-1 (19); group 3, 20 unique first-time UTI isolates (40); group 4, 15 unique recurrent UTI isolates (40); group 5, 21 blood isolates obtained from patients hospitalized at Erie County Medical Center (Buffalo, N.Y.); group 6, all 35 UTI isolates; and group 7, all 56 clinical isolates. Group 1 was most representative of nonpathogenic or commensal strains and therefore was used in statistical comparisons against the clinical isolate groups 5 to 7.

Ex vivo growth in human urine.

Human urine samples from subjects who had and who never had experienced a UTI were used for studies assessing growth of strains ex vivo. For these studies, urine was collected, individually filter sterilized, and stored at 4°C. The strain to be tested was grown overnight in 2 ml of LB medium with or without kanamycin (40 μg/ml). The next day, the bacterial cells were diluted into urine to achieve a starting concentration of approximately 102 to 103 CFU/ml, since this titer is at the lower end of the spectrum for what is considered significant for UTI in symptomatic young women (45). For A600 growth curves, a starting A600 of about 0.03 was used. During incubation at 37°C, aliquots were removed at intervals and either the A600 was determined or the bacterial titers were established by plating 10-fold serial dilutions in 1× phosphate-buffered saline in duplicate on appropriate media.

Gene regulation studies.

For osmoregulation studies, modified Davis medium was used with variable concentrations of either NaCl (0.05 to 0.7 M) or urea (0.05 to 0.7 M) (41). Some gene regulation studies used urine to which exogenous Fe (0.1 mM) or glucose (0.5%) was added. M9 minimal medium was also used in gene regulation studies. Fe was chelated from M9 medium by mixing 200 ml of medium with 21.2 g of washed (twice with one liter of distilled H2O) iminodiacetic acid (Chelex 100; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) for 90 min followed by filter sterilization. Siderophore production was determined by the Arnow assay as described previously (44) and was concomitantly measured to confirm that the Fe concentration was limiting when Fe was chelated. As expected, siderophore production increased from 3.1 μM/A600 in the presence of Fe (0.1 mM) to 10.7 μM/A600 when Fe was chelated. The effect of pH on expression was determined by using pooled urine whose pH was adjusted with either HCl or NaOH to achieve pHs 5.0, 6.0, and 7.0. For a given experiment, assays were performed in triplicate and experiments were repeated at least once. Results were presented as the ratio of reporter gene expression in urine relative to LB medium. For all studies, quantitative alkaline phosphatase and β-galactosidase assays were performed as described above.

Expression in human ascites and blood.

To assess gene expression in human ascites and blood, filter-sterilized ascites (peritoneal fluid) was obtained from a patient hospitalized at Erie County Medical Center, divided into multiple aliquots, and frozen at −80°C. Blood was used fresh and was obtained from a single donor. It was collected in sterile, 8.3-ml Vacutainer tubes which contained 1.7 ml of sodium polyanetholesulfonate (0.35%) and NaCl (0.85%) (nonbactericidal) as the anticoagulant. For blood assays, the bacterial cells were washed twice at 4°C with 4 ml of 0.1 M Tris (pH 9.8)–0.001 M MgCl2 buffer and resuspended in a total volume of 2 ml. For ascites assays, the bacterial cells were concentrated via centrifugation and the resultant pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of 0.1 M Tris (pH 9.8)–0.001 M MgCl2 buffer. Aliquots were removed twice, and CFU per milliliter was determined via serial 10-fold dilutions. Bacterial cells were subsequently permeabilized by adding 100 μl of 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 200 μl of chloroform, vortexed for 10 s, and kept on ice. A fluorescence assay was performed because erythrocytes with or without hemoglobin present in blood could not be reliably separated from bacterial cells. Their presence interfered with the colorimetric assays described above for measuring alkaline phosphatase and β-galactosidase activities.

Assays were performed in a 48-well tissue culture plate. Each assay mixture consisted of 1 ml of Tris buffer, 50 μl of bacterial cell extract, and 50 μl (0.01 M) of the fluorescent substrate (4-methylumbelliferonephosphate or 4-methylumbelliferyl-2-acetamido-2-deoxy-β-d-galactoside). Samples were read with a fluorescence multiwell plate reader (CytoFluor II; PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, Mass.) at an excitation setting of 360 nm, an emission setting of 460 nm, and a gain of 80 for 15 cycles. The net sample rate (SR) in blood or ascites relative to that in LB broth established the fold induction. The SR was calculated as {[(fluorescence cycle B − fluorescence cycle A over the linear portion of the curve)/(elapsed time)] × 20} − (CP9 SR). Specific activities were determined by dividing net sample rates by CFU per milliliter. The sensitivities of the colorimetric and fluorescent assays were established to be similar.

Statistical analysis.

Fisher’s exact test was used for the comparison of fecal versus clinical isolates for the presence of iroNE. coli DNA sequence via dot blot assay.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession number of the complete nucleotide sequence for iroNE. coli is AF135597.

RESULTS

Isolation of mutants possessing active fusions with increased expression in human urine.

To identify genes from an extraintestinal isolate of E. coli with increased expression in human urine, we screened mutant libraries of CP9 containing active lacZ (TnphoA′1) or phoA (TnphoA) fusions ex vivo on human urine plates and on LB medium containing either XG or XP. Mutants with an apparent increase in activity when exposed to urine relative to LB medium underwent quantitative evaluation for confirmation. This approach had been previously used to identify argC, which upon subsequent evaluation also proved to be a urovirulence trait (37). Screening of the TnphoA′1 library resulted in the identification of CP9.I-2, and screening of the TnphoA library resulted in the identification of CP9.45, CP9.82, and CP9.274 (Table 1). To establish that these mutants were isogenic derivatives of CP9, we performed a series of studies to exclude the possibility that cryptic mutations were acquired during the mutagenesis procedure. The mutants were established as being isogenic and the gene fusions solely responsible for the identified increased expression in urine as follows: (i) mutants had a single transposon insertion, (ii) transduction of this insertion back into the wild-type strain (CP9) resulted in a derivative that possessed the same degree of increased expression in urine relative to LB medium as the original mutant, (iii) the transposon was physically in the same location in the transductant as in the original mutant via Southern analysis, and (iv) alterations in capsule, lipopolysaccharide, and outer membrane profiles did not occur. CP9.I-2, CP9.45, CP9.82, CP9.274, and their respective T4-generated transductants CPI-2, CP45, CP82, and CP274 met these criteria (data not shown). The transductants were used for further studies (Table 1).

Identification of genes with increased expression in human urine.

Subclones from CPI-2, CP45, CP82, and CP274 containing a portion of their transposon insertion and a portion of the chromosomal DNA 5′ to their insertion were obtained as described above. These subclones were designated pCPI-2.1, p45.1, p82.1, and p274.1 (Table 1). The sequence obtained from these subclones was compared with GenBank, EMBL, DDBJ, and PDB entries.

(i) CPI-2.

A portion of the gene into which TnphoA′1 was inserted in CPI-2 was subcloned and partially sequenced. Comparisons with sequences in both DNA and protein databases disclosed 95% homology with an E. coli K-12 gene that encodes a putative 474-amino-acid (aa) protein of unknown identity and function (b1444, AE000241 [bases 6820 to 8244]). Using a modification of a previously devised nomenclature system for genes with increased expression in vivo (50), this gene was designated ure1 (urine-responsive element). The identification of ure1 via an active lacZ fusion suggests that it encodes a protein that is, at least in part, located in the cytoplasm. Although ure1 encodes a distinct product, a limited degree of homology was identified in several genes encoding aldehyde dehydrogenases, including betB from E. coli, which codes for a protein that is part of the pathway responsible for the conversion of choline to betaine. Betaine is considered the most important substance conferring osmoprotection in E. coli (5, 6). At the DNA level, ure1 has 71% (120 of 168 bases) homology over two short, selected regions spanning a total of 168 bases. At the protein level (over 381 bases) there are identities of 36% (46 of 127 aa) and similarities of 54% (69 of 127 aa).

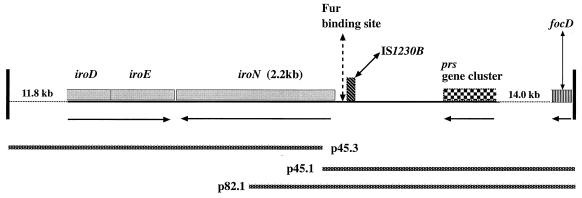

(ii) CP45 and CP82.

The gene into which TnphoA inserted in both CP45 and CP82 has been designated iroNE. coli. Using subclones p45.1, p45.3, and p82.1, we determined and analyzed the DNA sequence of iroNE. coli (accession no. AF135597) and the regions 5′ and 3′ to this gene (Fig. 1). This is a novel gene for E. coli. The predicted protein (IroNE. coli) consists of 725 aa, a putative molecular mass of 79,380 kDa, and an estimated pI of 5.68, and the first 24 aa represent a putative signal sequence. Comparison with entries in GenBank revealed that iroNE. coli was most homologous (77% nucleotide homology) with the recently identified Salmonella enterica catecholate siderophore receptor gene designated iroNS. enterica (3). iroNS. enterica is part of a five-gene cluster that includes iroBCDEN. The specific functions of the gene products for iroBCDE remains unclear, and a gene encoding the cognate siderophore for IroNS. enterica has yet to be identified. To date we also have identified E. coli homologues (iroDEE. coli) of iroDES. enterica 3′ to iroNE. coli in CP9, and the genomic organization has been maintained (Fig. 1). This cluster is iron regulated, and a putative Fur DNA binding site was present 5′ to both iroNS. enterica (86 bases) and iroNE. coli (100 bases), with 15 of 19 bases conserved. Further, 184 bases 5′ to the start site of iroNE. coli are 137 bases which were 87% (120 of 137 bases) homologous to the Salmonella insertion sequence IS1230 (bases 1 to 137; accession no. AJ000635). These bases correspond to the first 137 bases from this IS3-like element, the first 39 of which consist of an imperfect inverted repeat (7). This IS element was not present 5′ to iroNS. enterica. Taken together, these data suggested that iroNE. coli was acquired from S. enterica via IS element-mediated horizontal transfer. iroNE. coli possessed a lesser degree of homology with the catecholate siderophore receptors from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (pfeA), Bordetella pertussis (bfeA), and the fepA siderophore receptor from E. coli. The deduced protein sequence identity and similarity of IroNE. coli determined by pairwise amino acid alignment using the program CLUSTAL to IroNS. enterica, FepA, PfeA, and BfeA are summarized in Table 2. Although we have not established that iroNE. coli is fully translated and its product is functional, its identification as an active phoA fusion demonstrates it is at least partially translated. Further, sequence analysis did not reveal any premature stop codons, and its predicted size is nearly identical to that of iroNS. enterica.

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the iroNE. coli gene and the flanking sequence described in this report. From left to right, 11.8 kb of sequence, represented by the dotted line (not to scale relative to the solid line), consisting of the 5′ portion of the iroDE. coli gene and genome 5′ to it; a portion of the iroDE. coli gene (0.6 kb), iroEE. coli (0.9 kb), and iroNE. coli (2.2 kb); a putative Fur DNA binding site which is 100 bases 5′ to the deduced start site of iroNE. coli (79% [15 of 19 bases] homologous to the analogous iroNS. enterica site); a portion of an IS1230-like element (bp 1 to 137; accession no. AJ000635) which is 184 bp 5′ to the deduced start site of iroNE. coli (87% [120 of 137 bases] homologous to IS1230) and consists of its first 137 bases of which the initial 39 bases consist of an imperfect inverted repeat; end of the prs operon (the 17-kDa-protein gene; accession no. X62158) 1.6 kb 5′ to the deduced start site of iroNE. coli; 14 kb of sequence represented by the dotted line (not to scale relative to the solid line), the most distal boundary of which consists of the 3′ portion of focD, the molecular usher for the F1C fimbria. Arrows below the solid line indicate directions of transcription for iroDEE. coli, iroNE. coli, the prs operon, and focD. DNA sequence from the inserts (represented by the labeled bars minus TnphoA sequence) contained in plasmids p45.3, p45.1, and p82.1 was used to define the sequence of iroNE. coli and the genomic organization of its flanking regions. Their construction is described in Table 1.

TABLE 2.

Deduced protein sequence identity and similarity of IroNE. coli determined by CLUSTAL alignments to IroNS. enterica, FepA, PfeA, and BfeA

| Species | Homologue | % Identity | % Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. enterica | IroNS. enterica | 82 | 91 |

| E. coli | FepA | 52 | 69 |

| P. aeruginosa | PfeA | 52 | 69 |

| B. pertussis | BfeA | 53 | 68 |

Additional sequence analysis of DNA 5′ to iroNE. coli has demonstrated that this gene is 1.6 kb 3′ to the prs gene cluster, which encodes the class III PapG adhesin (Fig. 1). Further, although the precise genomic organization of the region 5′ to the prs operon has not been determined, the molecular usher for the F1C fimbria (26), focD, has also been identified approximately 15.6 kb 5′ to the deduced start site for iroNE. coli (Fig. 1). Novel loci of unique DNA not present in laboratory strains of E. coli have been termed pathogenicity islands (PAI), and iroNE. coli represents a portion of such a locus. The prs gene cluster is located on PAI II in the E. coli pathogen 536 and on PAI V in the closely related strain J96 (46).

To determine the phylogenetic distribution of iroNE. coli among various isolates of E. coli, a 667-bp internal DNA probe (AF135597 bases 1729 to 2396) which did not have any homology with fepA was generated from iroNE. coli. This probe was used in a dot blot assay to detect the presence of homologous iroNE. coli sequence (Table 3). In short, 43% of the 14 group 1 fecal isolates did not possess DNA sequence homologous to iroNE. coli. In contrast, only 20% of the 5 group 2, 5% of the 20 group 3, 7% of the 15 group 4, and 10% of the 21 group 5 isolates were negative for iroNE. coli-homologous sequence under high-stringency conditions. The differences between group 1 versus either group 5, group 6, or group 7 were statistically significant (P = 0.039, P = 0.004, or P = 0.003, respectively). In summary, these data demonstrate that DNA sequence homologous to iroNE. coli is significantly less prevalent in fecal isolates without the virulence gene pap, hly, or cnf-1 than clinical isolates.

TABLE 3.

Phylogenetic distribution of iroNE. coli-homologous DNA sequencea

| Dot Blot scoreb | % (no.) of isolatesc

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 | Group 6 | Group 7 | |

| 0 | 43 (6) | 20 (1) | 5 (1) | 7 (1) | 10 (2)d | 6 (2)e | 7 (4)f |

| 1+ | 43 (6) | 0 (0) | 50 (10) | 27 (4) | 57 (12)g | 40 (14)g | 46 (26)g |

| 2+ | 14 (2) | 80 (4) | 45 (9) | 67 (10) | 33 (7)g | 54 (19)h | 46 (26)i |

| Any+ | 57 (8) | 80 (4) | 95 (19) | 93 (14) | 90 (19)d | 94 (33)e | 93 (52)f |

Group 1, 14 unique fecal isolates previously established not to contain pap, hly, or cnf-1 and therefore most representative of nonpathogenic strains (19); group 2, 5 unique fecal isolates possessing some combination of pap, hly, or cnf-1 and therefore most likely to represent pathogenic strains (19); group 3, 20 unique first-time UTI isolates (40); group 4, 15 unique recurrent UTI isolates (40); group 5, 21 blood isolates obtained from patients hospitalized at Erie County Medical Center; group 6, all 35 UTI isolates (groups 3 and 4); group 7, all 56 clinical isolates (groups 3 to 5).

0, no homology; 1+, positive homology; 2+, maximal homology; any+, combination of 1+ and 2+.

Fisher’s exact test was used for proportions. All comparisons are versus group 1.

P = 0.039.

P = 0.004.

P = 0.003.

P > 0.10 (not significant).

P = 0.01.

P = 0.03.

(iii) CP274.

CP274 possessed an active TnphoA fusion in artJ (97% DNA homology). artJ is part of a recently described periplasmic arginine transport system (artPIQMJ), with artJ coding for a periplasmic protein that binds arginine with high affinity (49). Since artJ (19.38 centisomes) and argC (89.51 centisomes) are not part of the same operon, these findings independently support the results obtained with CPI-1 (argC), which demonstrate that arginine concentrations are limited and are a regulatory signal in urine (37).

Expression of ure1, iroNE. coli, and artJ in human urine.

Expression of ure1, iroNE. coli, and artJ was increased in human urine relative to LB medium. Since the composition of human urine has the potential to be variable, assays were performed with 17 to 29 independent urine samples collected from 10 different individuals, 5 of whom were women with a prior history of UTI. The results of these quantitative assays are summarized in Table 4. Although there was variance in the degree of increased expression from urine sample to urine samples, increased expression was seen in all samples evaluated. The degrees of expression of ure1, iroNE. coli, and artJ were similar in urine samples from individuals with and without a prior history of UTI. The 17 to 29 independent samples used were filter sterilized and stored at 4°C prior to use. To determine if the processing of urine affected gene expression, assays were performed in parallel, using samples that were either (i) fresh and unfiltered, (ii) fresh and filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter, or (iii) filtered and stored at 4°C. The degrees of expression of ure1, iroNE. coli, and artJ were similar, regardless of how the urine was processed (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Ex vivo expression of ure1, iroNE. coli, and artJ in human urine relative to LB medium

| Strain | Mean fold increased expression ± SE | Median fold increase in expression (range) |

|---|---|---|

| CPI-2a (ure1) | 47.6 ± 7.5 | 36.7 (3.3–206) |

| CP9.82bc (iroNE. coli) | 27.2 ± 5.0 | 19.0 (2.4–132) |

| CP9.274bd (artJ) | 16.6 ± 1.9 | 15.4 (2.9–39.3) |

β-Galactosidase specific activity measured in Miller units (17 experiments).

PhoA specific activity expressed as micromoles of p-nitrophenyl phosphate hydrolyzed per minute per A600 unit.

29 experiments.

28 experiments.

Modulation of ure1, iroNE. coli, and artJ expression.

To substantiate or gain insight into the function of the gene products of ure1, iroNE. coli, and artJ, and/or environmental signals present in urine, fusion expression and growth were measured in various media in vitro.

(i) Osmolarity.

Sequence analysis suggested that ure1 may encode a novel aldehyde dehydrogenase. Therefore we speculated that ure1 may be involved in a novel pathway that results in the generation of osmoprotectants in urine. To begin to test this hypothesis, we evaluated whether the expression of ure1 was osmotically regulated. However, the expression of ure1 in modified Davis medium was unaffected by increases in osmolarity from exogenous urea or NaCl compared to expression in LB medium. Further, other than the previously observed decrease in plateau density of CPI-2 relative to CP9 when grown in urine, no additional growth differences occurred between these strains when grown in human urine to which increasing concentrations of urea were added (data not shown). Taken together, these findings suggest that ure1 does not play a role in osmoprotection.

(ii) Carbon source.

Glucose is present in low concentrations (0.33 nmol/ml) in urine (2) and therefore may regulate gene expression. Interestingly, the increased expression of ure1 in three independent urine samples relative to LB medium was completely suppressed by the exogenous addition of 0.5% glucose (mean 86-fold decrease in lacZ activity). However, exogenous glucose did not affect the expression of iroNE. coli and artJ in human urine relative to LB medium (data not shown). Suppression of only ure1 expression in urine by glucose suggests that ure1, but not iroNE. coli or artJ, is a gene in E. coli that is regulated by catabolite repression.

(iii) Amino acids and nucleotides.

Certain amino acids (e.g., arginine) and nucleosides (guanine) are limiting in urine, whereas others are available (16, 37). The addition of exogenous arginine (0.01%) to human urine repressed the increased expression of artJ relative to LB in that medium (mean 35-fold decrease in phoA activity). This finding demonstrates that the concentration of arginine affects the expression of artJ in urine and supports previous data that established that the concentration of arginine is limited in human urine. In contrast, limiting concentrations of amino acids or nucleosides did not affect the expression of ure1 (M9 with glycerol) or iroNE. coli (M9 with glucose) relative to LB medium (data not shown).

(iv) Iron.

Sequence analysis of iroNE. coli strongly suggests that this gene codes for a catecholate siderophore receptor; therefore, the role of Fe in the regulation of iroNE. coli was evaluated. Expression of iroNE. coli was measured when CP82 (iroNE. coli) was grown in M9 minimal medium in which Fe was either chelated or added exogenously. iroNE. coli expression was 20.8-fold higher in CP82 grown in Fe-chelated M9 medium than in CP82 grown in M9 medium plus Fe. Further, the addition of exogenous Fe to three independent human urine samples suppressed the increased expression of iroNE. coli relative to LB medium (mean 64-fold decrease in phoA activity). These experimental findings, in combination with the identification of a Fur binding sequence 5′ to the start of iroNE. coli, suggest that iroNE. coli is Fur regulated and that Fe is limited in urine. In contrast, the addition of exogenous Fe to six independent urines did not significantly alter the expression of ure1 in human urine.

(v) pH.

Although the pH of normal urine usually ranges from 5.5 to 6.5, values from 5.0 to 8.0 can occur. Therefore, the effect of pHs 5.0, 6.0, and 7.0 on the expression of ure1, iroNE. coli, and artJ in human urine was evaluated. Changes in pH had no dramatic effect on the expression of artJ and ure1 in urine relative to LB. We measured fold inductions of 54, 38, and 53 for artJ and 89, 134, and 150 for ure1 at pHs 5.0, 6.0, and 7.0, respectively. In contrast, the expression of iroNE. coli was completely suppressed at pH 5.0 but unaffected at pHs 6.0 and 7.0; induction ratios of 0.23, 32, and 34, respectively, were measured. Therefore, for at least iroNE. coli, urinary pH can affect gene expression.

In summary, these findings support the concept that low concentrations of glucose, Fe, and arginine are present in human urine. Further, urinary pH can modulate gene expression. The addition of glucose to urine suppresses the expression of ure1; however, its expression is unaffected by limiting concentrations of amino acids, nucleotides, or Fe or differences in osmolarity or pH from 5.0 to 7.0. Low Fe concentrations increase the expression of iroNE. coli, and its expression is suppressed at a urinary pH 5.0 but unaffected by limiting concentrations of amino acids, nucleotides, or glucose. Last, the expression of artJ is suppressed by the addition of exogenous arginine to urine but is unaffected by limiting concentrations of nucleotides or glucose or differences in pH from 5.0 to 7.0.

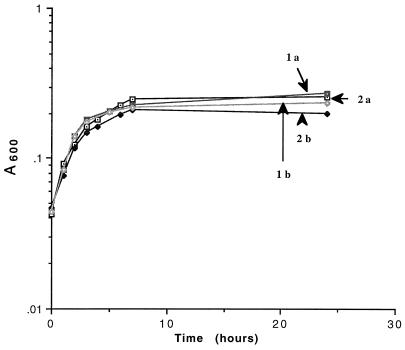

Growth of CPI-2, CP82, and CP274 in human urine.

Growth of CP9 (wild type), CPI-2 (ure1), CP82 (iroNE. coli), and CP274 (artJ) was evaluated in multiple independent urine samples via both enumeration of bacterial titers and A600. Growth of CP82 (five urine samples) and CP274 (eight urine samples) was equivalent to that of their wild-type parent CP9 (data not shown). CPI-2 demonstrated a small but reproducible decrease in plateau density compared to CP9. Representative growth curves of CPI-2 and CP9 in human urine are depicted in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Growth curves of CP9 (wild type) and CPI-2 (ure1) in human urine, incubated at 37°C and shaken at 90 rpm. Cultures were grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium with or without kanamycin (40 μg/ml) and diluted in urine to achieve an A600 of approximately 0.03. Aliquots were removed over time, and growth was measured by A600. 1a, CP9 in urine 1; 1b, CPI-2 in urine 1; 2a, CP9 in urine 2; 2b, CPI-2 in urine 2.

Expression of ure1, iroNE. coli, and artJ in human blood and ascites.

The expression of various virulence traits may vary depending on the site of infection. Therefore, ure1, iroNE. coli, and artJ expression was evaluated in human blood and ascites, two additional body fluids which extraintestinal E. coli isolates commonly infect. All of these genes had increased expression in blood and ascites (Table 5). Although there was some variance in expression compared to urine, particularly the increased expression of iroNE. coli and the diminished expression of artJ in ascites, these findings should be interpreted with caution. The ascites and blood were obtained from single individuals. A range of increased expression was seen when these genes were evaluated in individual urine samples (Table 4). This may also prove to be the case when ascites and blood from a number of different individuals are evaluated.

TABLE 5.

Ex vivo expression of ure1, iroNE. coli, and artJ in human blood and ascites relative to LB medium

| Strain | Mean fold increased expression ± SE ina:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Blood | Ascites | |

| CPI-2 (ure1) | 31.5 ± 7.4 | 35.4 ± 3.3 |

| CP9.82 (iroNE. coli) | 65.8 ± 6.7 | 207.2 ± 27 |

| CP9.274 (artJ) | 20.2 ± 1.8 | 5.1 ± 2.0 |

Specific activities were determined by dividing SR (calculated as described in Materials and Methods) by CFU per milliliter (mean of five experiments).

DISCUSSION

The identification of genes with increased expression in vivo may lead to the identification of novel or unrecognized virulence traits and/or recognition of environmental signals involved in modulating virulence gene expression (29). We had previously reported that argC had increased expression in human urine ex vivo, and subsequent in vivo studies confirmed that ArgC played a role in uropathogenesis in vivo. We also demonstrated that arginine and guanine (or derivatives) were limiting in urine (37). In this study we have continued with this approach and have identified and initially characterized three additional genes, ure1, iroNE. coli, and artJ, that have increased expression ex vivo in human urine.

Sequence analysis of iroNE. coli strongly suggests that this gene encodes a catecholate siderophore receptor that has not been previously identified in E. coli. Likewise, sequence analysis identifies artJ as the gene that encodes the periplasmic protein ArtJ, which binds arginine with high affinity (49). We speculated that the increased expression of artJ in urine may be part of an acid stress response since decarboxylation of arginine consumes a proton and hence helps stabilize the pH within the cell (4). However, an unvarying degree of expression in urine over the pH range of 7.0 to 5.0 is against this hypothesis. The function of Ure1 also remains unclear. However, regulatory studies suggest that Ure1 does not play a role in osmoprotection. Further, a small but reproducible decrease in growth of CPI-2 suggests that Ure1 is required for maximal growth in urine; however, since limiting concentrations of amino acids, nucleosides, or Fe do not affect the regulation of ure1, the role of Ure1 is likely independent of the synthesis or uptake of these nutrients.

The increased expression of artJ, ure1, and iroNE. coli in human urine supports the contention that arginine, glucose, and Fe are limiting in urine. The reported range for concentrations of arginine in adult urine is 10 to 90 nmol/ml (28). We had previously determined experimentally that concentrations in seven urine samples ranged from 3.8 to 34.6 nmol/ml, with respective 90 to 50% decreases in plateau density growth (37). Therefore, it appears that in most if not all urines, the arginine concentration does not support optimal growth of E. coli. The detection of increased expression of argC and artJ in human urine represents a form of bioassay that is consistent with this finding. The reported concentration of glucose in normal human urine is 0.33 nmol/ml (2). Since the limiting concentration of glucose (0.05%) for the growth of E. coli is 280 nmol/ml, E. coli genes regulated by catabolite repression may have increased expression in human urine. The gene ure1 appears to be such an example. Prediction as to the expression of Fe-regulated genes in human urine, based on the concentrations of Fe in urine, is less straightforward. The reported range of Fe in urine is 0.54 to 3.6 nmol/ml, concentrations more than sufficient for growth (8). However, it is highly likely that most, if not all, of this Fe is not bioavailable. The increased expression of iroNE. coli in human urine supports this contention. In addition, the increased expression of artJ, ure1, and iroNE. coli in blood and ascites suggests that arginine, glucose, and Fe may be limiting in these biologic fluids as well. The increased expression of iroNE. coli in urine observed at pHs 6.0 and 7.0 did not occur at pH 5.0. Whether the suppression of iroNE. coli expression in urine at pH 5.0 is due to either increased solubility and hence bioavailability of Fe or an Fe-independent regulatory mechanism is being investigated. Regardless of the mechanism, however, urinary pH can significantly modulate gene expression.

Although studies to directly assess whether these genes encode virulence traits have not yet been performed, the combination of sequence results, expression studies, regulatory studies, and homologues in other pathogens suggests that several of these genes most likely contribute to pathogenesis. Sequence analysis suggests that Ure1 may act as an aldehyde dehydrogenase. Of interest is the presence of an aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (aldA) in a Vibrio cholerae PAI (23) which is regulated by the cholera toxin transcriptional activator ToxR (32). The location and regulation of aldA suggest that it may be a virulence trait; however, its role, if any, in the pathogenesis of cholera is unknown. Although a role for ure1 in the pathogenesis of E. coli infection has not yet been tested, in contrast to V. cholerae, a variety of animal infection models exist for E. coli, which should facilitate studies that address this question. Since CP9 does not contain an aerobactin gene cluster (20), the finding that CP82 (iroNE. coli) grows equivalently to its wild-type parent CP9 in human urine might be considered surprising. However, CP9, like most pathogens, possesses a functional redundancy in Fe acquisition systems. A homologue of the siderophore receptor FyuA (43) is present in CP9 (17). It is likely that both known Fe uptake systems present in the K-12 chromosome (i.e., Fep and Cir), and others not yet identified are present as well. In fact, until the full extents of these systems have been defined and mutants with disruptions in multiple Fe acquisition genes have been generated, it may be difficult to demonstrate a role for a given trait in vivo. When properly defined mutants become available and are tested in a variety of host fluids and infection models, it will be interesting to determine if the functionally redundant Fe acquisition proteins merely serve as backups or possess more specific site- or host substrate-related functions (1). It is clear that much remains to be learned about the specific uptake systems present in extraintestinal isolates of E. coli and the details surrounding the biology of this superfamily. Nonetheless, the deduced function of iroNE. coli, its increased expression in urine, blood, and peritoneal fluid, its location on a PAI with linkage to the prs and foc operons, and the increased prevalence of iroNE. coli-homologous sequence in UTI and blood isolates versus fecal isolates implicate it as a potential virulence trait. In contrast to CPI-1 (argC), the growth of CP274 (artJ) was equivalent to that of its wild-type parent CP9 in human urine. These results suggest that in the presence of an intact arginine biosynthetic pathway, sufficient arginine can be synthesized or transported via other uptake systems to maintain normal growth in urine. Interestingly, a gene that is part of the arginine transport system in Listeria monocytogenes, arpJ, has increased expression during infection of host cells (25). It can be inferred from these findings that the ability of E. coli to synthesize or acquire arginine is necessary for maximal virulence within the urinary tract.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant AI 42059 and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

We appreciate the continued support of Tim Murphy and Bruce Holm. We thank Jim Johnson for statistical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Åslund F, Beckwith J. The thioredoxin superfamily: redundancy, specificity, and gray-area genomics. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1375–1379. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1375-1379.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asscher A W, Sussman M, Weiser R. Bacterial growth in human urine. In: O’Grady F, Brumfitt W, editors. Urinary tract infection. London, England: Oxford University; 1968. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumler A J, Norris T L, Lasco T, Voigt W, Reissbrodt R, Rabsch W, Heffron F. IroN, a novel outer membrane siderophore receptor characteristic of Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1446–1453. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1446-1453.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bearson S, Bearson B, Foster J W. Acid stress responses in enterobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;147:173–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers S, Kunin C M. The osmoprotective properties of urine for bacteria: the protective effect of betaine and human urine against low pH and high concentrations of electrolytes, sugars, and urea. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:1308–1316. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.6.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambers S T, Kunin C M. Isolation of glycine betaine and proline betaine from human urine. J Clin Investig. 1987;79:731–737. doi: 10.1172/JCI112878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collighan R J, Woodward M J. Sequence analysis and distribution of an IS3-like insertion element isolated from Salmonella enteritidis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;154:207–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnenberg M S, Welch R A. Virulence determinants of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. In: Mobley H, Warren J, editors. Urinary tract infections: molecular pathogenesis and clinical management. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 135–174. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DuPont H L, Spink W W. Infections due to gram-negative organisms: an analysis of 860 patients with bacteremia at the University of Minnesota Medical Center, 1958–1966. Medicine. 1969;48:307–332. doi: 10.1097/00005792-196907000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenstein B I, Jones G W. The spectrum of infections and pathogenic mechanisms of Escherichia coli. Adv Intern Med. 1988;33:231–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emori T G, Gaynes R P. An overview of nosocomial infections, including the role of the microbiology laboratory. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:428–442. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.4.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ena J, Amador C, Martinez C, Delatabla V O. Risk factors for acquisition of urinary tract infections caused by ciprofloxacin resistant Escherichia coli. J Urol. 1995;153:117–120. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199501000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geerdes H F, Ziegler D, Lode H, et al. Septicemia in 980 patients at a university hospital in Berlin: prospective studies during 4 selected years between 1979 and 1989. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:991–1002. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.6.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gransden W R, Eykyn S J, Phillips I, Rowe B. Bacteremia due to Escherichia coli: a study of 861 episodes. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:1008–1018. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.6.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henquell C, Sirot D, Chanal C, De Champs C, Chatron P, Lafeuille B, Texier P, Sirot J, Cluzel R. Frequency of inhibitor-resistant TEM β-lactamases in Escherichia coli isolates from urinary tract infections in France. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:707–714. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.5.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hull R A, Hull S I. Nutritional requirements for growth of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in human urine. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1960–1961. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1960-1961.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson, J. Personal communication.

- 18.Johnson J R. Virulence factors in Escherichia coli urinary tract infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:80–128. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson J R, Brown J J, Carlino U B, Russo T A. Colonization with and acquisition of uropathogenic Escherichia coli as revealed by polymerase chain reaction-based detection. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1120–1124. doi: 10.1086/517409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson J R, Russo T A, Scheutz F, Brown J J, Zhang L, Palin K, Rode C, Bloch C, Marrs C F, Foxman B. Discovery of a disseminated J96-like clone of uropathogenic Escherichia coli O4:H5 containing both genes for both PapGJ96 (class I) and PrsGJ96 (class III) Gal (α1-4)Gal-binding adhesins. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:983–988. doi: 10.1086/514006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson J R, Stamm W E. Urinary tract infections in women: diagnosis and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:906–917. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-11-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson J R, Stapleton A E, Russo T A, Scheutz F, Brown J J, Maslow J N. Characteristics and prevalence within serogroup O4 of a J96-like clonal group of uropathogenic Escherichia coli O4:H5 containing the class I and class III alleles of papG. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2153–2159. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2153-2159.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karaolis D K, Johnson J A, Bailey C C, Boedeker E C, Kaper J B, Reeves P R. A Vibrio cholerae pathogenicity island associated with epidemic and pandemic strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;17:3134–3139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kern W V, Andriof E, Oethinger M, Kern P, Hacker J, Marre R. Emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli at a cancer center. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:681–687. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.4.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klarsfeld A D, Goossens P L, Cossart P. Five Listeria monocytogenes genes preferentially expressed in infected mammalian cells: plcA, purH, purD, prE and an arginine ABC transporter gene, arpJ. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:585–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klemm P, Jørgensen B J, Kreft B, Christiansen G. The export systems of type 1 and F1C fimbriae are interchangeable but work in parental pairs. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:621–627. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.621-627.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreger B E, Craven D E, Carling P C, McCabe W R. Gram-negative bacteremia. III. Reassessment of etiology, epidemiology and ecology in 612 patients. Am J Med. 1980;68:332–343. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee P L Y, Slocum R H. A high-resolution method for amino acid analysis of physiologic fluids containing mixed disulfides. Clin Chem. 1988;34:719–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mekalanos J L. Environmental signals controlling expression of virulence determinants in bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.1-7.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muhldorfer I, Hacker J. Genetic aspects of Escherichia coli virulence. Microb Pathog. 1994;16:171–181. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. Identification of procaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parsot C, Mekalanos J J. Expression of the Vibrio cholerae gene encoding aldehyde dehydrogenase is under control of ToxR, the cholera toxin transcriptional activator. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2842–2851. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2842-2851.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patton J P, Nash D B, Abrutyn E. Urinary tract infection: economic considerations. Med Clin North Am. 1991;75:495–513. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30466-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perez-Trallero E, Urbieta M, Jimenez D, Garcia-Arenzana J M, Cilla G. Ten-year survey of quinolone resistance in Escherichia coli causing urinary tract infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:349–351. doi: 10.1007/BF01964432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russo T A, Brown J J, Jodush S T, Johnson J R. The O4 specific antigen moiety of lipopolysaccharide but not the K54 group 2 capsule is important for urovirulence in an extraintestinal isolate of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2343–2348. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2343-2348.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russo T A, Guenther J E, Wenderoth S, Frank M M. Generation of isogenic K54 capsule-deficient Escherichia coli strains through TnphoA-mediated gene disruption. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:357–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russo T A, Jodush S T, Brown J J, Johnson J R. Identification of two previously unrecognized genes (guaA, argC) important for uropathogenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:217–229. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russo T A, Sharma G, Brown C R, Campagnari A A. The loss of the O4 antigen moiety from the lipopolysaccharide of an extraintestinal isolate of Escherichia coli has only minor effects on serum sensitivity and virulence in vivo. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1263–1269. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1263-1269.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Russo T A, Singh G. An extraintestinal, pathogenic isolate of Escherichia coli (O4/K54/H5) can produce a group 1 capsule which is divergently regulated from its constitutively produced group 2, K54 capsular polysaccharide. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7617–7623. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.23.7617-7623.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russo T A, Stapleton A, Wenderoth S, Hooton T M, Stamm W E. Chromosomal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of Escherichia coli strains causing recurrent urinary tract infections in young women. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:440–445. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sage A E, Vasil A I, Vasil M L. Molecular characterization of mutants affected in the osmoprotectant-dependent induction of phospholipase C in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:43–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.1681542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;85:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schubert S, Rakin A, Karch H, Carniel E, Heeseman J. Prevalence of the “high-pathogenicity island” of Yersinia species among Escherichia coli strains that are pathogenic to humans. Infect Immun. 1998;66:480–485. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.480-485.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwyn B, Neilands J B. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal Biochem. 1987;160:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stamm W E, Counts G W, Running K R, Fihn S, Turck M, Holmes K K. Diagnosis of coliform infection in acutely dysuric women. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:463–468. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198208193070802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Susa M, Kreft B, Wasenauer G, Ritter A, Hacker J, Marre R. Influence of cloned tRNA genes from a uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain on adherence to primary human renal tubular epithelial cells and nephropathogenicity in rats. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5390–5394. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5390-5394.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vorland I H, Carlson K, Aalen O. An epidemiologic survey of urinary tract infections among outpatients in northern Norway. Scand J Infect Dis. 1985;17:277–283. doi: 10.3109/inf.1985.17.issue-3.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilmes-Riesenberg M R, Wanner B L. TnphoA and TnphoA′ elements for making and switching fusions for study of transcription, translation, and cell surface localization. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4558–4575. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4558-4575.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wissenbach U, Keck B, Unden G. Physical map location of the new artPIQMJ genes of Escherichia coli, encoding a periplasmic arginine transport system. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3687–3688. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3687-3688.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young G M, Miller V L. Identification of novel chromosomal loci affecting Yersinia enterocolitica pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:319–328. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4661829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang J P, Normark S. Induction of gene expression in Escherichia coli after pilus-mediated adherence. Science. 1996;273:1234–1236. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5279.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]