Abstract

Endotoxemia is accompanied by significant changes in the reductive-oxidative (redox) balance of critical target organs. Redox stress has been shown to regulate the expression of proinflammatory genes that are induced by endotoxic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in vitro; however, much less is known about the effects of redox imbalance on LPS-induced gene expression in vivo. To assess the effects of redox stress on inflammatory responses in endotoxemia, mice were treated with either diethyl maleate (DEM), a glutathione-depleting agent, or buthionine sulfoximine (BSO), an inhibitor of glutathione synthesis, and challenged with LPS. While serum tumor necrosis alpha (TNF-α) responses and the appearance of TNF-α-positive Kupffer cells in the liver were virtually eliminated by DEM or BSO treatment, the expression of both CD14 and inducible NO synthase (iNOS) by Kupffer cells was unaffected by glutathione depletion. By contrast, LPS-induced hepatocyte and hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cell iNOS expression was significantly inhibited in DEM-treated mice. Hepatocyte iNOS induced by recombinant mouse TNF-α was also inhibited by DEM treatment. These results indicate that the effects of oxidative stress in this organ are cell type specific and suggest that both the production and the action of TNF-α are substantially influenced by the redox state of the liver during endotoxemia.

Sepsis is a complex biological response to infection that involves the action of a number of proinflammatory cells and soluble mediators. One of the hallmarks of this condition is the production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates that have a range of biological effects, including antimicrobial activity and the induction of host tissue damage. Several observations, including the appearance of circulating lipid peroxidation products, changes in tissue antioxidant levels, and the expression of stress-responsive genes, suggest that reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates are produced at high concentrations in animals challenged with endotoxic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (12, 21, 46, 48, 55, 56, 61). These findings also indicate that significant changes in the reductive-oxidative (redox) state of tissues occur during endotoxemia and are due, in part, to the release of radicals and other pro-oxidants from activated inflammatory cells (4, 29, 60).

The expression of many LPS-inducible inflammatory genes can be regulated by redox stress in vitro (10, 14, 19, 37, 39, 42, 47), and evidence suggests that reduced oxygen intermediates and nitric oxide-derived metabolites can mediate many of these effects (14, 19, 47). Thus, altered cellular redox balance can be viewed as an important means of regulating the expression of LPS-induced genes, suggesting that reactive oxygen and nitrogen species may even be integral intermediates in certain LPS signaling pathways (43).

Glutathione plays a central role in maintaining intracellular redox balance (11, 58). Reduced glutathione sulfhydryl (GSH) is the most plentiful nonprotein thiol within cells and serves as a major antioxidant by ensuring a highly reduced intracellular environment. Several changes in the glutathione redox cycle, including the depletion of total cellular glutathione, decreases in the ratio of GSH to glutathione disulfide, and the inhibition of important glutathione-associated enzymes (e.g., glutathione reductase), can lead to redox stress. For example, diethyl maleate (DEM) conjugates directly with GSH and rapidly depletes the antioxidant (11). For this reason the compound has been widely used to induce redox stress both in vitro and in vivo. Glutathione can also be depleted by blocking its biosynthesis with buthionine sulfoximine (BSO), which inhibits the rate-limiting enzyme γ-glutamylcysteine synthase (22). Treating either animals or cells with DEM or BSO induces the expression of a variety of stress-responsive genes, including those for the heat shock protein HSP-32 and metallothionein-1 (15, 20, 49).

The tissue macrophage plays a central role in the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin in the mouse, given its wide anatomical distribution, its sensitivity to activation by LPS, and the ability of the cell to produce large quantities of key inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin 1β, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and nitric oxide. For this reason, a number of investigators have asked to what extent redox stress can influence macrophage responses to LPS in vitro. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species derived from exogenous chemical sources (e.g., NO donors) as well as exogenous antioxidants, radical scavengers, NO synthase inhibitors, and agents that deplete glutathione have been used to alter cellular redox balance in this context (14, 23, 25, 39, 41, 42, 52). The results of these in vitro studies have indicated that the LPS-induced expression of many murine macrophage genes, including that of the TNF-α, inducible NO synthase (iNOS), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor genes, is redox regulated (14, 23, 25, 39, 41, 42). However, much less is known about the effects of redox stress on macrophage responses to LPS in vivo or the specificities of these effects in LPS-challenged animals.

This study was designed to address these important topics. We have analyzed LPS-induced inflammatory responses in the liver for several reasons. The liver contains large numbers of tissue macrophages (i.e., Kupffer cells), and these cells contribute significantly to the elevated circulating levels of inflammatory mediators induced by LPS challenge (7, 27). In addition, several Kupffer cell responses to LPS are shared by neighboring hepatic parenchymal cells, affording us the opportunity to compare the effects of redox imbalance on macrophages to its effects on other hepatic cell types. The findings reported here indicate the existence of inherently stress-sensitive and stress-resistant LPS signaling pathways in the liver and suggest that the redox state of Kupffer cells may have profound effects on inflammatory responses of other cells in this important shock organ.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

LPS from Salmonella enteritidis, DEM, BSO, 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid), Nonidet P-40, glutathione reductase, lactate dehydrogenase, hydrogen peroxide, cold-water fish skin gelatin, and paraformaldehyde were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). A single lot of S. enteritidis LPS (no. 65H4069) was used for the experiments reported here. Paraplast X-Tra was purchased from Fisher Scientific (St. Louis, Mo.). Peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin was from BioGenex (San Ramon, Calif.). Aspergillus nitrate reductase was obtained from Boehinger Mannheim (Indianapolis, Ind.). Normal goat serum, rabbit serum, and immunoglobulin G (IgG) and protease-free bovine serum albumin were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, Pa.). Avidin-biotin blocking and diaminobenzidine chromogen kits were obtained from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, Calif.). Recombinant mouse TNF-α was kindly provided by Genentech (South San Francisco, Calif.).

Animals.

Female 6- to 10-week-old C3HeB/FeJ and CF1 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) and Charles River (Wilmington, Mass.), respectively. Both strains are LPS responsive (lps+). The animals were maintained on 12-h light–12-h dark cycles, with food and water being given ad libitum in an American Association of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited facility at the University of Kansas Medical Center. Animal care and use protocols were approved by an institutional animal care and use committee.

Measurement of glutathione.

Mouse tissues were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and extracts were prepared by homogenizing the tissues in 0.125 M phosphate–EDTA buffer with a Polytron tissue homogenizer (Brinkman Instruments, Westbury, N.Y.). Following centrifugation, the extracts were deproteinized by the addition of a 6% (vol/vol) solution of 0.1 M HCl and a 6% (vol/vol) solution of 50% sulfosalicylic acid as described by Tietze (57). After centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min, samples were neutralized with 3 M K2PO4. The total glutathione concentrations (reduced plus oxidized) of tissue extracts were determined by the recycling assay described by Tietze (57) and were expressed as nanomoles of glutathione per milligram of protein. Protein concentrations were determined according to the method of Bradford (5) with a Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) protein dye reagent.

Assay for TNF-α.

The concentrations of TNF in mouse sera were determined by the L929 cell cytotoxicity assay as previously described (44). Serum samples were diluted 1:4 prior to the assay, which resulted in a detection limit of 40 U/ml. None of the chemicals used to induce stress affected the killing of L929 cells by recombinant mouse TNF-α.

Measurement of serum nitrate and nitrite.

The concentrations of nitrate and nitrite (the principal metabolites of nitric oxide in blood) were measured in serum samples by a modification of the procedure described by Schmidt et al. (53). Briefly, the nitrate in 5- to 10-μl samples of serum was reduced to nitrite by the addition of 200 mU of nitrate reductase/ml, 100 μM NADPH, and 5 μM flavine adenine dinucleotide in 20 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.6. After the reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 45 min, the excess NADPH was oxidized with lactate dehydrogenase (10 U/ml) in the presence of 10 mM sodium pyruvate. Nitrite was then determined in a two-step procedure by first adding 2 mM sulfanilamide and by then adding 4% (vol/vol) concentrated HCl. After 15 min, 0.2 mM naphthylethylenediamine was added and the incubation was continued for an additional 10 minutes. Absorbance was read at 550 nm, and nitrite concentrations were extrapolated from a standard curve prepared with NaNO2.

Immunohistology.

Liver tissue was fixed in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at 4°C for 12 h. Following overnight washing in cold phosphate-buffered saline, the fixed tissues were dehydrated in graded ethanol and embedded in Paraplast X-Tra by standard procedures. Five-micrometer-thick sections were cut and deposited onto Superfrost slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.).

The primary antibodies used in this study included the following: purified rat monoclonal anti-mouse macrophage F4/80 antibody (3), rat monoclonal anti-mouse TNF-α (MP6-XT22) antibody (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.), affinity-purified rabbit anti-mouse iNOS (M-19) antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, Calif.), rat monoclonal anti-mouse CD14 antibody (rmC5-3; Pharmingen), and rabbit anti-HSP-32 antibody (SPA895; StressGen, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada).

Immunohistochemical staining was performed by the indirect peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin procedure (18) with the following modifications. All incubations were performed at room temperature. Briefly, deparaffinized sections were incubated in a blocking solution consisting of phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 0.5% gelatin, and either 5% normal goat serum (for the iNOS and HSP-32 antibodies) or 5% normal rabbit serum (for the TNF-α, CD14, and F4/80 antibodies). The respective blocking solution was also used as a dilution medium for all primary and secondary antibodies. Following initial blocking, sections were treated with an avidin-biotin blocking reagent according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Vector Laboratories). The sections were then incubated for 2 h with antibody to either TNF-α, CD14, iNOS, or F4/80 at concentrations of 10, 10, 1, or 10 μg/ml, respectively. After the sections were washed, either biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG diluted 1:30 (BioGenex) or biotinylated rabbit anti-rat IgG (Vector Laboratories) at a concentration of 10 μg/ml was added for 30 min. After further washing, the sections were treated for 15 min with 1% H2O2 in methanol to inactivate endogenous peroxidases. The bound secondary antibodies were then detected by incubating sections with a peroxidase-streptavidin conjugate diluted 1:30 (BioGenex). Reaction sites were visualized with diaminobenzidine according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sections were counterstained with Gill II hematoxylin (Shandon, Pittsburgh, Pa.).

All slides were read independently by two individuals. The densities of positively stained Kupffer cells and hepatocytes were determined for at least five microscopic fields (magnification, ×200) and expressed as cells per high-power field (HPF). Hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells were scored in a semiquantitative fashion, with −, +, ++, and +++ representing negative, faint, moderate, and strong staining, respectively.

RESULTS

DEM depletes glutathione and induces stress responses in the mouse liver.

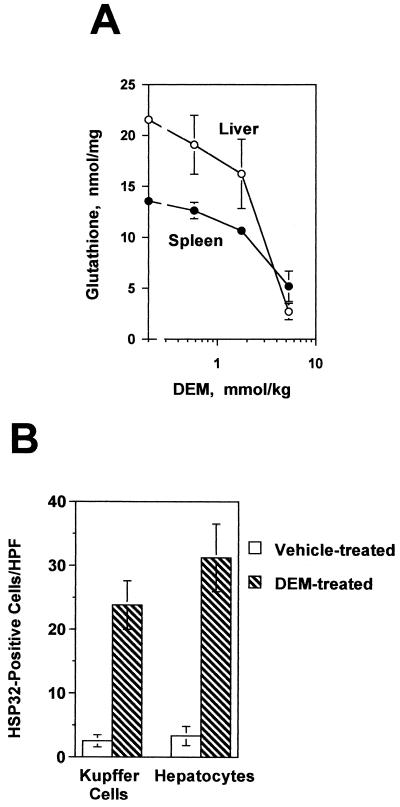

Dose-response experiments indicated that an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of DEM at a dose of 5.3 mmol/kg of body weight was sufficient to decrease levels of glutathione in the livers of C3HeB/FeJ mice by 90% within 2 h (Fig. 1A). Glutathione levels remained depressed for at least 6 h thereafter. To determine whether DEM treatment also led to the expression of oxidant-stress-responsive genes, immunohistological techniques were used to detect the heat shock protein HSP-32 in the liver. Kupffer cells, hepatocytes, and sinusoidal endothelial cells from DEM-treated mice (Fig. 1B and 2A) each expressed HSP-32, indicating that glutathione depletion was associated with stress protein expression in several different hepatic cell types. Therefore, in subsequent experiments redox stress was induced by treating mice with DEM at a dose of 5.3 mmol/kg for 2 h prior to LPS challenge.

FIG. 1.

DEM depletes liver glutathione and induces HSP-32 expression in C3HeB/FeJ mice. (A) Four mice in each group were injected i.p. with the indicated doses of DEM, and their hepatic and splenic glutathione levels were measured 2 h later. Levels of both hepatic and splenic glutathione in the group receiving 5.3 mmol of DEM/kg were significantly different from the levels of the control group (P < 0.005) as determined by Student’s t test. (B) Mice were injected i.p. with 5.3 mmol of DEM per kg, and HSP-32 expression in their livers was characterized 5 h later by immunohistology. Five HPFs (magnification, ×200) were examined for each section. The two groups in panel B are significantly different from one another (P < 0.01) as calculated by Student’s t test. Each group contained four mice.

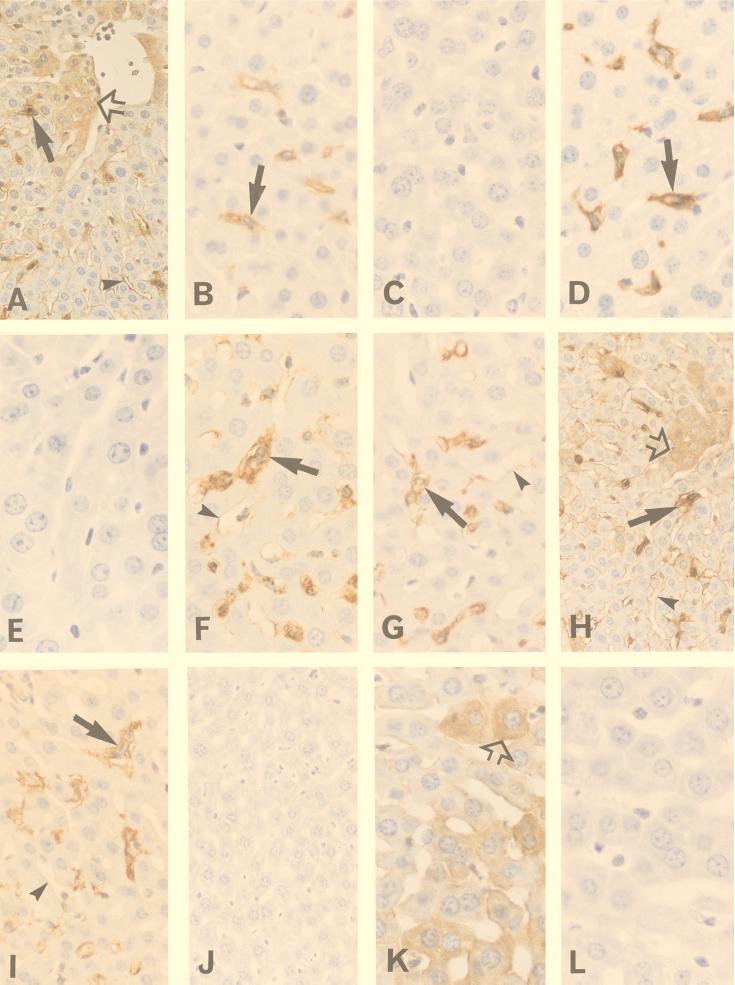

FIG. 2.

Expression of HSP-32, TNF-α, CD14, and iNOS in the livers of control and DEM-treated C3HeB/FeJ mice. One group of mice was injected with DEM (5.3 mmol/kg i.p.), and HSP-32 expression was determined 5 h later. The remaining mice were pretreated with either DEM or the vehicle for 2 h and were then challenged i.p. with either 100 μg of S. enteritidis LPS/kg or 12 μg of recombinant mouse TNF-α/kg. With the LPS-challenged mice, liver samples were recovered 1 h later to measure TNF-α expression or 6 h later to measure CD14 and iNOS expression. In mice challenged with recombinant TNF-α, tissues were collected 12 h after challenge. (A) HSP-32 staining in DEM-treated mice. Note that Kupffer cells (filled arrow), hepatocytes (open arrow), and sinusoidal endothelial cells (arrowhead) all expressed HSP-32. (B) TNF-α staining in the vehicle control, LPS-challenged mice. Shown here are TNF-α-expressing Kupffer cells (arrow). (C) TNF-α staining in DEM-treated, LPS-challenged mice. Note the absence of TNF-α-positive Kupffer cells. (D) Kupffer cells (arrow) identified by staining with F4/80 antibody. (E) Preabsorbing the anti-TNF-α antibody with recombinant TNF-α blocked staining in the vehicle control, LPS-challenged mice. (F) CD14 staining in the vehicle control, LPS-challenged mice. Shown here are CD14-positive Kupffer cells (arrow) and moderately stained sinusoidal endothelial cells (arrowhead). (G) CD14 staining in DEM-treated, LPS-challenged mice. Note that the staining of Kupffer cells (arrow) is similar to what was seen in the control, LPS-challenged group. (H) iNOS staining in control, LPS-challenged mice. Note that Kupffer cells (filled arrow), hepatocytes (open arrow), and sinusoidal endothelial cells (arrowhead) all express iNOS. (I) iNOS staining in DEM-treated, LPS-challenged mice. While Kupffer cells remained strongly iNOS positive (arrow), sinusoidal endothelial cells (arrowhead) were only faintly stained and there was no hepatocyte iNOS staining. (J) Preabsorption of the iNOS antibody with the immunizing iNOS peptide abolished staining in the control, LPS-challenged group. (K) iNOS staining in control, recombinant-TNF-α-challenged mice. Note that iNOS staining is essentially seen only in hepatocytes (open arrow). (L) iNOS staining in DEM-treated, recombinant-TNF-α-challenged mice showing the loss of hepatocyte iNOS expression. The original magnification for panels B to G, K, and L was ×360. For panels I and J the magnification was ×300, and for panels A and H the magnification was ×250.

Redox stress differentially inhibits Kupffer cell gene expression in mice challenged with endotoxic LPS.

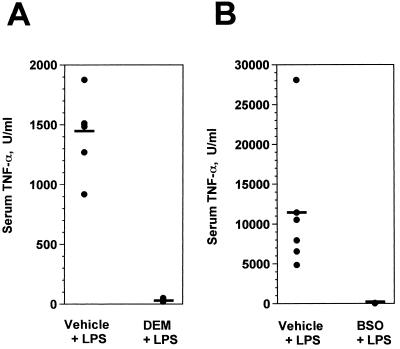

Because it has been reported that LPS-induced Kupffer cell TNF-α production in vitro is regulated by intracellular thiol content (39), we first characterized the effects of DEM on serum TNF-α levels in LPS-challenged mice. As shown in Fig. 3A, serum TNF-α responses to challenge with 100 μg of LPS were completely inhibited by DEM treatment compared to the responses of control mice that had been pretreated with the drug vehicle (sesame oil) and then challenged with LPS. This result indicated that TNF-α responses to LPS in vivo were highly sensitive to tissue redox changes, which was confirmed by treating mice with BSO to inhibit glutathione synthesis (Fig. 3B). Under conditions in which BSO inhibited hepatic glutathione levels by 86%, serum TNF-α responses to LPS were reduced to near background levels.

FIG. 3.

Treating mice with DEM or BSO inhibits serum TNF-α responses to LPS challenge. (A) C3HeB/FeJ mice (lps+) were injected with either sesame oil (vehicle) or DEM i.p. The animals were challenged i.p. 2 h later with 100 μg of S. enteritidis LPS, and serum samples were collected 1 h later. (B) CF1 mice (lps+) were injected with 0.15 M NaCl (vehicle) or 5 mmol of BSO in 0.15 M NaCl 6 h and again 3 h prior to LPS challenge. Serum samples were collected 1 h after LPS challenge, and TNF-α concentrations were measured. Each point represents the result with an individual animal (five to six mice per group), and the horizontal lines represent group means. In both panels A and B the two groups are significantly different from one another (P < 0.005), as calculated by Student’s t test.

To determine whether DEM decreased circulating TNF-α levels by inhibiting its biosynthesis or enhancing the metabolism of the cytokine, the frequency of TNF-α-producing Kupffer cells in the liver was measured by immunohistological techniques. The liver was selected for this purpose because the organ is a major source of circulating TNF-α produced in response to LPS (7, 27). Mice that were either challenged with 100 μg of S. enteritidis LPS or pretreated with the drug vehicle and then challenged with LPS showed significant numbers of TNF-α-expressing Kupffer cells in their livers (Fig. 2B). Pretreating mice with DEM virtually eliminated this response (Fig. 2C). The TNF-α-positive cells were identified as Kupffer cells based on their expression of the macrophage-specific marker F4/80 (Fig. 2D). No TNF-α staining was seen in liver tissues from normal mice (data not shown), and the TNF-α staining of Kupffer cells in LPS-challenged mice was completely abolished by preabsorbing the primary antibody with recombinant mouse TNF-α (Fig. 2E). These data indicate that DEM decreased the serum TNF-α response to LPS, in large part by inhibiting the synthesis of the cytokine in the liver.

Because Kupffer cells also expressed high densities of CD14 after LPS challenge, this response was used to determine the specificity of DEM. In contrast to Kupffer cell TNF-α expression, cellular CD14 expression was unaffected by DEM pretreatment (Fig. 2F versus G). This result indicates that redox imbalance in the mouse liver differentially inhibits LPS-induced macrophage gene expression rather than causing a global inhibition of inflammatory responses.

Redox regulation of LPS-induced iNOS responses in the liver.

We then undertook a similar analysis of iNOS expression in the liver based on the premise that TNF-α and iNOS expression represent two independent signaling pathways in LPS-activated macrophages (2, 45, 63). Normal mouse livers contained few, if any, iNOS-expressing cells. When mice were either challenged with 100 μg of LPS or pretreated with sesame oil and then challenged with LPS, their livers contained numerous iNOS-positive cells 6 h later (Fig. 2H). These included Kupffer cells, hepatocytes, and sinusoidal endothelial cells, a finding that is consistent with those in previous reports (1, 9, 13, 30, 50, 54). As reported by others (36, 40), hepatocyte iNOS staining was not uniform throughout the liver and positive cells were often found adjacent to blood vessels. Of interest, this pattern was similar to the distribution of staining obtained with antibody to LPS (data not shown). Pretreating mice with DEM had no effect on either the staining intensity or the frequency of iNOS-positive Kupffer cells (Fig. 2I), indicating that LPS-induced macrophage iNOS expression in the mouse liver, like the CD14 response, was unaffected by redox stress. However, iNOS expression by hepatocytes and endothelial cells was highly sensitive to redox changes. DEM treatment essentially eliminated the hepatocyte iNOS response to LPS and reduced the intensity of iNOS expression by sinusoidal endothelial cells (Fig. 2H and I).

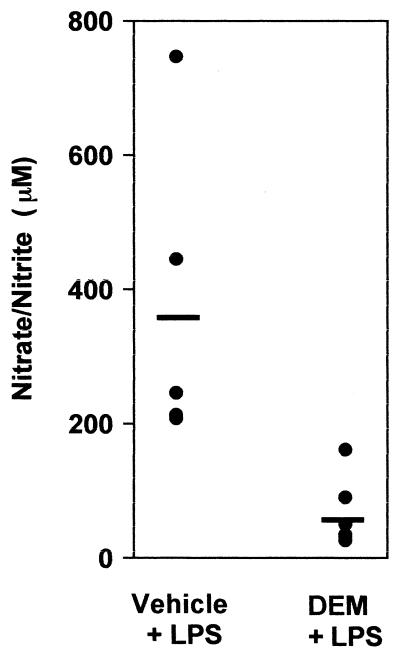

To estimate the magnitude of the effects of DEM on these in vivo liver responses to LPS, the frequencies of TNF-α-, CD14-, and iNOS-positive hepatic cells were determined. The results are summarized in Table 1 and demonstrate that TNF-α expression by Kupffer cells was completely blocked in DEM-treated mice. By contrast, both the Kupffer cell CD14 and iNOS responses were stress resistant under these conditions. The frequency of hepatocytes expressing iNOS was significantly decreased by DEM pretreatment as was the intensity of iNOS staining by sinusoidal endothelial cells. These effects of DEM on iNOS expression in hepatocytes and endothelial cells correlated with a significantly lower level of circulating nitrates and nitrites in stressed animals measured 16 h after LPS challenge (Fig. 4). Thus, glutathione depletion not only decreased hepatocyte and hepatic endothelial cell iNOS responses but also substantially impaired total nitric oxide synthesis in response to LPS challenge.

TABLE 1.

Frequencies of various cell types in the livers of DEM-treated, LPS-challenged C3HeB/FeJ mice that express TNF-α, CD14, or iNOS

| Antigen | Treatmenta | No. of positive Kupffer cells/HPFb | No. of positive hepatocytes/HPFb | Intensity of positive endothelial cellsbc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | Vehicle | 20.8 ± 1.1 | <0.2 | − |

| DEM | <0.2d | <0.2 | − | |

| CD14 | Vehicle | 61.7 ± 2.1 | <0.2 | ++ |

| DEM | 61.0 ± 2.5 | <0.2 | ++ | |

| iNOS | Vehicle | 65.2 ± 2.9 | 81 ± 4 | ++ |

| DEM | 63.3 ± 1.8 | <0.2d | + |

Two groups of mice (n = 6/group) received either the sesame oil vehicle or 5.3 mmol of DEM/kg i.p. 2 h prior to being challenged i.p. with 100 μg of S. enteritidis LPS. Tissues were recovered either 1 h (for TNF-α) or 6 h (for iNOS and CD14) later.

At least five randomly selected HPFs (magnification, ×200) were scored for each tissue section (n = 6 mice/group).

Intensity scores for endothelial cells were assigned on a scale from − to +++ (see Materials and Methods).

The results for this group differed significantly from those for its control (vehicle-treated) group (P < 0.005) as calculated by Student’s t test.

FIG. 4.

Serum nitrate and nitrite responses to LPS challenge are inhibited by redox stress. (A) C3HeB/FeJ mice were treated with either sesame oil or DEM and then challenged i.p. with 100 μg of S. enteritidis LPS. Sixteen hours later, serum nitrate and nitrite concentrations were measured. Each point represents the response of a single animal (six to seven mice per group), and the horizontal lines indicate group means. Group results were significantly different from one another (P < 0.01), as calculated by Student’s t test. The concentrations of nitrates and nitrites in the sera of normal mice were less than 25 μM.

TNF-α-induced hepatic iNOS expression is redox regulated in vivo.

Hepatocyte iNOS can be induced by TNF-α in vitro (1, 13, 30), and this response is inhibited by DEM (13). Thus, the loss of the hepatocyte iNOS response in DEM-treated mice may have resulted from either the decreased production of TNF-α or the direct effects of DEM on the hepatocytes themselves. To determine which of these mechanisms explained the observations summarized in Table 1, we challenged DEM-treated and control mice with recombinant mouse TNF-α and measured hepatic iNOS expression. The results are shown in Fig. 2K and L and summarized in Table 2. While recombinant TNF-α was not an effective stimulus for inducing iNOS in Kupffer cells or endothelial cells, it did stimulate strong hepatocyte iNOS expression in control mice (Fig. 2K). However, this response was absent in DEM-treated animals (Fig. 2L). Likewise, exogenous TNF-α did not restore the hepatocyte iNOS response in DEM-treated, LPS-challenged mice (data not shown). These findings indicate that the hepatocyte iNOS response to TNF-α in vivo is inherently stress sensitive and suggest that the loss of hepatocyte iNOS expression in DEM-treated, LPS-challenged mice resulted from redox imbalance within the hepatocytes themselves.

TABLE 2.

Effects of DEM on hepatic iNOS expression induced by recombinant TNF-α

| Treatmenta | No. of positive Kupffer cells/HPFb | No. of positive hepatocytes/HPFb | Intensity of positive endothelial cellsbc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 1 ± 1.3 | 64.0 ± 7.3 | + |

| DEM | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 2.5 ± 1.9d | − |

Two groups of mice (n = 4/group) received either sesame oil or 5.3 mmol of DEM/kg i.p. 2 h prior to being challenged i.p. with 10 μg of recombinant mouse TNF-α/kg. Twelve hours later, tissues were recovered and iNOS expression was determined.

At least five randomly selected HPFs (magnification, ×200) were scored for each tissue section.

Intensity scores for endothelial cells were assigned on a scale of − to +++ (see Materials and Methods).

The results for this group differed significantly from those for its control (vehicle-treated) group (P < 0.01) as calculated by Student’s t test.

DISCUSSION

A number of published reports indicate that redox stress can substantially alter macrophage responses to LPS in vitro (6, 10, 14, 23, 25, 39, 41), but relatively few studies have determined the significance of these findings with regard to intact, endotoxemic animals (e.g., see reference 38). For this reason, we treated mice with DEM to deplete cellular glutathione and characterized the LPS-induced gene expression in the liver that resulted. We included an analysis of TNF-α and iNOS expression because the results of several in vitro studies suggest that these responses represent two independent LPS signaling pathways in mouse macrophages (2, 45, 63). Control, LPS-challenged mice expressed high levels of hepatic TNF-α and iNOS protein, and elevated levels of TNF-α and nitrate or nitrite were measured in their sera. While Kupffer cell iNOS and CD14 expression were unaffected by DEM treatment, TNF-α expression by these cells was virtually eliminated.

This pattern of gene expression differs somewhat from that reported by Nathens et al. (38), who studied local responses to LPS in the rat lung. In that study, DEM inhibited the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 by pulmonary endothelial cells responding to the local instillation of LPS but did not affect TNF-α mRNA levels in lung tissues. The lack of an effect on TNF-α production in the lung may reflect differences between pulmonary and hepatic macrophages and parallels the findings described by Matuschak and colleagues (35, 59), who have compared TNF-α responses in perfused rat livers and lungs elicited by challenge with viable Escherichia coli bacteria. Transient hypoxia and reoxygenation was found to inhibit TNF-α mRNA responses in the liver but had the opposite effect in the lung. Thus, the same response can be regulated differently in these two organs, emphasizing the need to evaluate each shock organ affected by endotoxemia independently. The finding that two biochemically distinct forms of stress induction (i.e., DEM and BSO treatment) used in the present study produced similar effects on gene expression underscores the important conclusion that macrophage inflammatory genes inherently differ from one another in their redox sensitivities in vivo.

A number of investigators (6, 8, 13, 24, 25, 28, 30, 41) have shown that the expression of iNOS in cultured cells, including macrophages, hepatocytes, and endothelial cells, is regulated by cellular redox balance. For example, Buchmuller-Rouiller et al. (6) reported that DEM treatment of mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages inhibited the induction of iNOS by LPS plus gamma interferon in vitro and both Hecker et al. (25) and Pahan et al. (41) showed that antioxidants blocked LPS-induced iNOS expression in cultured murine macrophages. Glutathione depletion has also been shown by a number of groups to substantially inhibit the expression of iNOS by primary cultures of hepatocytes (13, 25). By contrast, Kuo et al. (28) have more recently reported that oxidant stress associated with superoxide formation increased iNOS gene transcriptional activity in rat hepatocytes. For this reason, we were interested in determining how redox stress associated with glutathione depletion in vivo would affect iNOS expression in the livers of endotoxin-challenged mice. The results of this study indicate that there are substantial cell-type-specific differences in this regard. While DEM treatment induced the expression of HSP-32 in all three hepatic cell types studied, only the hepatocyte and endothelial cell iNOS responses to LPS challenge were inhibited by redox stress. Kupffer cell iNOS expression was unaffected when glutathione was depleted in vivo with DEM. Thus, in addition to showing gene-specific effects, oxidative stress in vivo shows cell type and, perhaps, organ-specific effects, and one cannot always predict from in vitro models the behavior of a given cell type in vivo.

Because hepatocytes contribute substantially to the systemic inflammatory responses seen in endotoxemia (1, 7, 13, 26, 27, 32), it is important to understand how the activation of these cells is regulated and what role Kupffer cells play in their responses to LPS. Hepatocyte iNOS expression can be induced by TNF-α, a response that depends on the type I TNF receptor (31). Although some differences of opinion exist regarding the role of TNF-α as a required mediator of LPS-induced iNOS expression (51, 62), a recent study with type I TNF receptor-null mice indicates that the expression of iNOS mRNA by at least some hepatic cells of LPS-stimulated mice is highly TNF-α dependent (51). Thus, the simplest explanation for decreased LPS-induced iNOS expression by hepatocytes of DEM-treated mice was the absence of detectable TNF-α production by these animals. However, the finding that DEM inhibited TNF-α-induced hepatocyte iNOS expression in vivo indicates that redox changes in the hepatocytes themselves also regulate this response, regardless of the availability of stimulating TNF-α. This interpretation is consistent with the results of an earlier study by Duval et al. (13), who showed that DEM can inhibit TNF-α-induced rat hepatocyte iNOS expression in vitro.

An incidental finding reported in this study was the moderate immunohistological staining of hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells of LPS-challenged mice with CD14 antibody (Fig. 2F), which was not seen in the livers of unstimulated mice. We have not confirmed this reaction with other CD14-specific antibodies, and at least three other reports (16, 17, 33) have failed to note the expression of hepatic endothelial cell CD14 protein or mRNA in LPS-challenged mice. Thus, the significance of endothelial cell staining in the present study remains to be determined.

Not surprisingly, inflammatory responses to gram-negative bacterial infections also appear to be redox regulated. As noted above, Matushak and his colleagues (34, 35, 59) have reported that E. coli-induced IL-1α and TNF-α gene expression in the perfused rat liver and lung can be regulated by brief hypoxia followed by reoxygenation, a treatment that is thought to induce radical formation. A greater understanding of the specific redox-regulated changes that occur during gram-negative infections, compared to those seen in endotoxemia, would aid in predicting the outcomes of therapies directed at restoring redox balance. The results of the present study suggest that such therapies would indeed enhance the expression of certain proinflammatory genes in the liver (e.g., the TNF-α gene) and may have other unexpected effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant KS-97-GS-62 from the American Heart Association. F.W. was a recipient of a fellowship from the Infectious Disease and Cancer Training Program of the Kansas Health Foundation/Margaret Jane Harley Fund.

We thank David Morrison for his contributions to this study. Joan Hunt generously provided the antibody F4/80. We also thank Glen Andrews for his advice and comments about the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamson G M, Billings R E. Cytokine toxicity and induction of NO synthase activity in cultured mouse hepatocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1993;119:100–107. doi: 10.1006/taap.1993.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amura C R, Chen L C, Hirohashi N, Lei M G, Morrison D C. Two functionally independent pathways for lipopolysaccharide-dependent activation of mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 1997;159:5079–5083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austin J M, Gordon S. F4/80, a monoclonal antibody directed specifically against the mouse macrophage. Eur J Immunol. 1981;11:805–815. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830111013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bautista A P, Meszaros K, Bojta J, Spitzer J J. Superoxide anion generation in the liver during the early stages of endotoxemia in rats. J Leukoc Biol. 1990;48:123–128. doi: 10.1002/jlb.48.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchmuller-Rouiller Y, Corradin S B, Smith J, Schneider P, Ransijn A, Jongeneel C V, Mauel J. Role of glutathione in macrophage activation: effect of cellular glutathione depletion on nitrite production and leishmanicidal activity. Cell Immunol. 1995;164:73–80. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chensue S W, Terebuh P D, Remick D G, Scales W E, Kunkel S L. In vivo biologic and immunohistochemical analysis of interleukin-1 alpha, beta and tumor necrosis factor during experimental endotoxemia. Kinetics, Kupffer cell expression, and glucocorticoid effects. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:395–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colasanti M, Persichini T, Menegazzi M, Mariotto S, Giordano E, Caldarera C M, Sogos V, Laura G M, Suzuki H. Induction of nitric oxide synthase mRNA expression. Suppression by exogenous nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26731–26733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curran R D, Billiar T R, Stuehr D J, Hofmann K, Simmons R L. Hepatocytes produce nitrogen oxides from l-arginine in response to inflammatory products of Kupffer cells. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1769–1774. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.5.1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeForge L E, Preston A M, Takeuchi E, Kenney J, Boxer L A, Remmick D G. Regulation of interleukin 8 gene expression by oxidant stress. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25568–25576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deneke S M, Fanburg B L. Regulation of cellular glutathione. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:L163–L173. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1989.257.4.L163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhaunsi G S, Singh I, Hanevold C D. Peroxisomal participation in the cellular responses to the oxidative stress of endotoxin. Mol Cell Biochem. 1993;126:25–35. doi: 10.1007/BF01772205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duval D L, Sieg D J, Billings R E. Regulation of hepatic nitric oxide synthase by reactive oxygen intermediates and glutathione. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;316:699–706. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eigler A, Moeller J, Endres S. Exogenous and endogenous nitric oxide attenuates tumor necrosis factor synthesis in the murine macrophage cell line RAW 264.7. J Immunol. 1995;154:4048–4054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ewing J F, Maines M D. Glutathione depletion induces heme oxygenase-1 (HSP32) mRNA and protein in rat brain. J Neurochem. 1993;60:1512–1519. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fearns C, Kravchenko V V, Ulevitch R J, Loskutoff D J. Murine CD14 gene expression in vivo: extramyeloid synthesis and regulation by lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1995;181:857–866. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fearns C, Loskutoff D J. Role of tumor necrosis factor alpha in induction of murine CD14 gene expression by lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4822–4831. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4822-4831.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felix R, Cecchini M G, Hofstetter W, Elford P R, Stuttzer A, Fleisch H. Impairment of macrophage colony-stimulating factor production and lack of resident bone marrow macrophages in the osteopetrotic op/op mouse. J Bone Miner Res. 1990;5:781–789. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650050716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng L, Xia Y, Garcia G E, Hwang D, Wilson C G. Involvement of reactive oxygen intermediates in cyclooxygenase-2 expression induced by interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-α, and lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Investig. 1995;95:1669–1675. doi: 10.1172/JCI117842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu K, Sarras M P, De Lisle R C, Andrews G K. Expression of oxidative stress-responsive genes and cytokine genes during caerulein-induced acute pancreatitis. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G696–G705. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.3.G696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh B, Hanevold C D, Dobashi K, Ovak J K, Singh I. Tissue differences in antioxidant enzyme gene expression in response to endotoxin. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;21:533–540. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffith O W, Meister A. Potent and specific inhibition of glutathione synthesis by buthionine sulfoximine (S-n-butyl homocysteine sulfoximine) J Biol Chem. 1979;254:7558–7560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griscavage J M, Rogers N E, Sherman M P, Ignarro L J. Inducible nitric oxide synthase from a rat alveolar macrophage cell line is inhibited by nitric oxide. J Immunol. 1993;151:6329–6337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harbecht B G, Di Silvio M, Chough V, Kim Y-M, Simmons R L, Billiar T R. Glutathione regulates nitric oxide synthase in cultured hepatocytes. Ann Surg. 1997;225:76–87. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199701000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hecker M, Preiss C, Klemm P, Busse R. Inhibition by antioxidants of nitric oxide synthase expression in murine macrophages: role of nuclear factor κB and interferon regulatory factor 1. Brit J Pharmacol. 1996;118:2178–2184. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15660.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koj A. The role of interleukin-6 as the hepatocyte stimulating factor in the network of inflammatory cytokines. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;557:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb23994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumins N H, Hunt J, Gamelli R L, Filkins J P. Partial hepatectomy reduces the endotoxin-induced peak circulating level of tumor necrosis factor in rats. Shock. 1996;5:385–388. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199605000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuo P C, Abe K Y, Schroeder R A. Oxidative stress increases hepatocyte iNOS gene transcription and promoter activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;234:289–292. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landmann R, Scherer F, Schumann R, Link S, Sansano S, Zimmerli W. LPS directly induces oxygen radical production in human monocytes via LPS binding protein and CD14. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:440–449. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laskin D L, Heck D E, Gardner C R, Feder L S, Laskin J L. Distinct patterns of nitric oxide production in hepatic macrophages and endothelial cells following acute exposure of rats to endotoxin. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56:751–758. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leist M, Gantner F, Jilg S, Wendel A. Activation of the 55 kDa TNF receptor is necessary and sufficient for TNF-induced liver failure, hepatocyte apoptosis, and nitrite release. J Immunol. 1995;154:1307–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luster M I, Germolec D R, Yoshida T, Kayama F, Thompson M. Endotoxin-induced cytokine gene expression and excretion in the liver. Hepatology. 1994;19:480–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsuura K, Ishida T, Setoguchi M, Higuchi Y, Akizuki S, Yamamoto S. Upregulation of mouse CD14 expression in Kupffer cells by lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1671–1676. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matuschak G M, Johanns C A, Chen Z, Gaynor J, Lechner A J. Brief hypoxic stress downregulates E. coli-induced IL-1α and IL-1β gene expression in perfused liver. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:R1311–R1318. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.5.R1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matuschak G M, Munoz C F, Johanns C A, Rahman R, Lechner A J. Upregulation of postbacteremic TNF-α and IL-1α gene expression by alveolar hypoxia/reoxygenation in perfused rat lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:629–637. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.2.9707120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morikawa A, Kato Y, Sugiyama T, Koide N, Chakravortty D, Yoshida T, Yokochi T. Role of nitric oxide in lipopolysaccharide-induced hepatic injury in d-galactosamine-sensitized mice as an experimental endotoxic shock model. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1018–1024. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1018-1024.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Munoz C, Castellanos M C, Alfranca A, Vara A, Esteban M A, Redondo J M, de Landazuri M O. Transcriptional up-regulation of intracellular adhesion molecule-1 on human endothelial cells by the antioxidant pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate involves the activation of activating protein-1. J Immunol. 1996;157:3587–3597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nathens A B, Biaar R, Watson R W G, Issekutz T B, Marshall J C, Dackiw A P B, Rotstein O D. Thiol-mediated regulation of ICAM-1 expression in endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. J Immunol. 1998;160:2959–2966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neuschwander-Tetri B A, Bellezzo J M, Britton B S, Bacon B R, Fox E S. Thiol regulation of endotoxin-induced release of tumor necrosis factor α from isolated rat Kupffer cells. Biochem J. 1996;320:1005–1010. doi: 10.1042/bj3201005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Osei S Y, Ahima R S, Fabry M E, Nagel R L, Bank N. Immunohistological localization of hepatic nitric oxide synthase in normal and transgenic sickle cell mice: the effects of hypoxia. Blood. 1996;88:3583–3588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pahan K, Sheikh F G, Namboodiri A M S, Singh I. N-Acetyl cysteine inhibits induction of NO production by endotoxin or cytokine stimulated rat peritoneal macrophages, C6 glial cells and astrocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;24:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park K K, Lin H L, Murphy S. Nitric oxide regulates nitric oxide synthase-2 gene expression by inhibiting NF-κB binding to DNA. Biochem J. 1997;322:609–613. doi: 10.1042/bj3220609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parmely M J. Nitric oxide as a signaling molecule in the systemic inflammatory response to LPS. In: Brade H, Morrison D, Opal S, Vogel S, editors. Endotoxin in health and disease. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1999. pp. 591–604. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parmely M J, Gale A, Clabaugh M, Horvat R, Zhou W-W. Proteolytic inactivation of cytokines by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3009–3014. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.3009-3014.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parmely M J, Hao S-Y, Morrison D C, Pace J L. Role of macrophage-derived nitric oxide in endotoxin lethality in mice. J Endotoxin Res. 1995;2:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peavy D L, Fairchild E J., II Evidence for lipid peroxidation in endotoxin-poisoned mice. Infect Immun. 1986;52:613–616. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.2.613-616.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peng H-B, Rajavashisth T B, Libby P, Liao J K. Nitric oxide inhibits macrophage-colony stimulating factor gene transcription in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17050–17055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.17050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Portoles M T, Tatala M, Anton A, Pagani R. Hepatic response to the oxidative stress induced by E. coli endotoxin: glutathione as an index of the acute phase during the endotoxic shock. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996;159:115–121. doi: 10.1007/BF00420913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rizzardini M, Carelli M, Cabello Porras M R, Cantoni L. Mechanisms of endotoxin-induced haem oxygenase mRNA accumulation in mouse liver: synergism by glutathione depletion and protection by N-acetylcysteine. Biochem J. 1994;304:477–483. doi: 10.1042/bj3040477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rockey D C, Chung J J. Regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase in hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:G260–G267. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.2.G260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salkowski C A, Detore G, McNally R, van Rooijen N, Vogel S N. Regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase messenger RNA expression and nitric oxide production by lipopolysaccharide in vivo. J Immunol. 1997;158:905–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scheffler L A, Wink D A, Melillo G, Cox G W. Exogenous nitric oxide regulates IFN-γ plus lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide synthase expression in mouse macrophages. J Immunol. 1995;155:886–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt H H H W, Warner T D, Nakane M, Forstermann U, Murad F. Regulation and subcellular location of nitrogen oxide synthase in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:615–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spitzer J A. Cytokine stimulation of nitric oxide formation and differential regulation in hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells of endotoxemic rats. Hepatology. 1994;19:217–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spolarics Z. Endotoxin stimulates gene expression of ROS-eliminating pathways in rat hepatic endothelial and Kupffer cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:G660–G666. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.270.4.G660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sugino K, Dohi K, Yamada K, Kawasaki T. Changes in the levels of endogenous antioxidants in the liver of mice with experimental endotoxemia and the protective effects of the antioxidants. Surgery. 1989;105:200–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tietze F. Enzymic method for quantitative determination of nanogram amounts of total and oxidized glutathione: applications to mammalian blood and other tissues. Anal Biochem. 1969;27:502–522. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Uhlig S, Wendel A. The physiological consequences of glutathione variations. Life Sci. 1992;51:1083–1094. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90509-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wibbenmeyer L A, Lechner A J, Munoz C F, Matuschak G M. Downregulation of E. coli-induced TNF-α expression in perfused liver by hypoxia-reoxygenation. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:G311–G319. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.268.2.G311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wizemann T M, Gardner C R, Laskin J D, Quinones S, Durham S K, Goller N L, Ohnishi S T, Laskin D L. Production of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in the lung during acute endotoxemia. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56:759–768. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.6.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong C, Flynn J, Demling R H. Role of oxygen radicals in endotoxin-induced lung injury. Arch Surg. 1984;119:77–82. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1984.01390130059011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xie J, Joseph K O, Bagby G J, Giles T D, Greenberg S S. Dissociation of TNF-α from endotoxin-induced nitric oxide and acute-phase hypotension. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H164–H174. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.1.H164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang X, Morrison D C. Lipopolysaccharide-induced selective priming effects on TNF-α and nitric oxide production. J Exp Med. 1993;177:511–516. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]