Abstract

Both periodontitis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are complex chronic conditions characterized by aberrant host immune response and dysregulated microbiota. Emerging data show an association between periodontitis and IBD, including direct and indirect mechanistic links between oral and intestinal inflammation. Direct pathways include translocation of pro-inflammatory microbes from the oral cavity to the gut and immune priming. Indirect pathways involve systemic immune activation with possible non-specific effects on the gut. There are limited data on the effects of periodontal disease treatment on IBD course and vice-versa, but early reports suggest that treatment of periodontitis decreases systemic immune activation and that treatment of IBD is associated with periodontitis healing, underscoring the importance of recognizing and treating both conditions.

Keywords: periodontal disease, oral-gut axis, microbiome, pathobiont, immunology, inflammatory bowel disease

Clinical and epidemiologic context of periodontal disease and inflammatory bowel disease

The oral-gut axis is an area of emerging interest because of the high burden of oral disease and recent discoveries elucidating the interplay between inflammation, the microbiome (see Glossary), and chronic disease in these related sites[1, 2]. Prior epidemiologic research has identified associations between oral health and a variety of medical conditions[3]. In this review, we will focus on the relationship between periodontitis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Periodontal disease is characterized by chronic inflammation affecting the bone and tissues around the tooth. This develops initially as gingivitis, a reversible inflammation of the gums and soft tissues around the tooth, and it progresses to involve the bone, cementum, and periodontal ligament. The causes of periodontitis are multifactorial but lead to chronic inflammation with progressive tissue destruction, exposing deeper structures to the oral microbiome, which leads to further host immune activation.

Periodontitis is one of the most prevalent conditions worldwide[4]. There is limited high-quality data on the international prevalence and trends in periodontal disease. The global prevalence of periodontitis is estimated to be 11.2% and increases with age[3–7]. There is significant variation in prevalence and incidence by region and country. The variability may be attributable to individual-level differences, availability of oral care, methodologic differences between studies, and a lack of nationally representative samples in most countries.

Despite these research challenges, data suggest that the prevalence of severe tooth loss (i.e. edentulism) is decreasing while the prevalence of advanced periodontitis is increasing, likely because of increasing longevity and improved preventive dental care that limits tooth loss[4, 5, 8].

In the US, an estimated 42% of all community-dwelling adults aged 30 years and older have periodontal disease, and 7.8% of the population has severe periodontitis[6]. Longitudinal Scandinavian data show that overall rates of periodontal disease are improving in highly developed countries, though the percentage of the population with severe disease has remained stable[9–14]. In China, Japan, and India, periodontal disease incidence has increased over the past three decades, and in South Korea and Thailand, the incidence has decreased[15]. There are limited data for other regions.

IBD is a set of idiopathic chronic inflammatory disorders affecting the GI tract. It includes two main types, Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). The pathogenesis of IBD is multifactorial, involving both host and environmental factors, such as genetics, diet, stress, and the microbiome[16]. CD is characterized by chronic transmural mucosal inflammation that can occur throughout the GI tract from mouth to anus, at times in a discontinuous pattern. Inflammation in UC is limited to the mucosa and occurs in a contiguous fashion in the colon, starting at the rectum, though there can be some involvement of the terminal ileum. The mouth is a common extra-intestinal site of IBD involvement, suggesting a role for the oral-gut immune and microbiome axis in pathogenesis. Previously, CD was felt to be a Th1 cell-predominant process, whereas UC was Th2-driven, though work on Th17 cells has led to a more complex understanding of these diseases[17].

In the US, IBD affects an estimated 1.3% of adults[18]. Globally, the incidence of IBD varies but has been increasing[19, 20]. In the past 25 years, IBD incidence in highly developed countries has risen slowly or plateaued[21, 22]. However in Asia, IBD incidence has increased dramatically, with some countries reporting rates that doubled or tripled in the same time frame[23, 24]. The highest age-standardized prevalence of IBD is in high-income areas of North America (422.0 cases per 100,000), whereas the lowest is in the Caribbean (6.7 per 100,000 population)[20].

The mechanisms by which periodontal disease may cause or exacerbate chronic gastrointestinal (GI) diseases are complex. We will discuss the epidemiologic evidence supporting an association between periodontitis and IBD, emerging research on the pathways behind these associations, controversies in the field, and future directions.

Associations between periodontal disease and IBD

On an epidemiologic level, multiple studies have demonstrated a strong association between IBD and periodontal disease (Table 1). Three recent meta-analyses found that periodontitis is associated with both CD and UC, with pooled odds ratios of 1.7–3.6 for CD and 2.4–5.4 for UC[25–27]. This association is seen both in adults as well as children and adolescents with IBD[28]. Individuals with IBD are more likely to have had dental treatments and have worse perceived oral health than healthy controls[29, 30]. This may be based on a greater need for dental procedures among individuals with IBD as compared to those without IBD, as was found in a Swedish cohort study[31].

Table 1.

Studies of Periodontitis and IBD

| Country | Design | IBD patients (n) | Healthy controls (n) | Periodontitis measures | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taiwan | Cohort | 6,657 (CD) | 26,628 | Billing codes | CD patients at increased risk of developing periodontitis (HR 1.36) | [68] |

| Sweden | Cohort | 3,161 (CD) and 2,085 (UC) | 5,246 | Dental care utilization | CD and UC patients had higher numbers of dental procedures following diagnosis, including more total procedures and fillings. | [31] |

| Korea | Cohort | 9,950,548 overall (IBD and no IBD) | Oral screening exam | Periodontitis associated with increased risk of UC development (aHR 1.091) but not CD (aHR 0.879). | [32] | |

| Taiwan | Cohort | 27,041 periodontal disease | 108,149 no periodont al disease | Billing codes | HR of IBD in both groups similar (HR 1.01), but increased risk of UC in periodontitis group after adjustment (aHR 1.56) | [34] |

| Sweden | Cohort | 20,162 overall (IBD and no IBD) | Oral exam at study entry | Tooth loss at baseline associated with lower risk of IBD development (HR 0.56). More plaque associated with lower CD risk (HR 0.32) | [34] | |

| Brazil | Cross-sectional case-control | 179 (99 CD and 80 UC) | 74 | DMFT, PPD, CAL, BOP, plaque index | More IBD patients had periodontitis than controls (81.8% CD, 90% UC, 67.6% controls). | [79] |

| Japan | Cross-sectional case-control | 60 (18 CD and 42 UC) | 45 | BOP, caries, PPD | No difference in periodontitis or caries between IBD and control groups. | [37] |

| Germany | Cross-sectional case-control | 62 (IBD type not specified) | 59 | DMFS, caries, plaque index, BOP, PPD, CAL | No difference in DMFS between groups but more dental caries and CAL in IBD group. | [80] |

| Jordan | Cross-sectional case-control | 160 (59 CD and 101 UC) | 100 | PPD, GR, LA, BOP, plaque index, gingival index | Higher prevalence of periodontitis in IBD group <45 years old and in adjusted analysis (OR for CD 4.9, OR for UC 7.0), and more severe periodontitis in IBD group. | [81] |

| Greece | Cross-sectional case-control | 55 (36 CD and 19 UC) | 55 | DMFT, gingival index, plaque index, periodontitis treatment needs | DMFT, gingival inflammation both higher in IBD. No difference in plaque index. Higher periodontal treatment needs in IBD group. | [28] |

| Italy | Cross-sectional case-control | 110 (IBD type not specified) | 110 | DMFT, PAI | DMFT and prevalence of apical periodontitis similar between IBD and control groups but higher PAI in IBD group. | [82] |

| Spain | Cross-sectional case-control | 54 (28 CD and 26 UC) | 54 | RPL, PAI, RFT | More RPL in IBD group (35.2% vs 16.7%), no difference in number of teeth with apical periodontitis or number of RFT | [83] |

| Germany | Cross-sectional case-control | 59 (30 CD and 29 UC) | 59 | DMFT, PPD, BOP, CAL | IBD patients had higher CAL, more severe periodontitis, and more gingival bleeding. | [84] |

| Sweden | Cross-sectional case-control | 150 (71 CD with prior intestinal surgery and 79 CD no surgery) | 75 | DMFT, DMFS, salivary flow, dental plaque | CD with prior resection had higher DMFS and more plaque than controls. | [85] |

| Netherlands | Cross-sectional case-control | 229 (148 CD, 80 UC, 1 IBD undetermined) | 229 | DMFT, DPSI | DMFT higher in IBD group. DMFT higher for CD than controls but not for UC. DPSI not different between IBD and control groups, but more IBD patients edentulous | [86] |

| Switzerland | Cross-sectional case-control | 113 (69 CD and 44 UC) | 113 | DMFT, PPD, PBI, LA, PPD, BOP | Worse DMFT, PBI, LA-PPD, BOP in IBD. In CD group, clinical activity (HBI) associated with worse LA-PPD; perianal disease associated with BOP. | [87] |

| Greece | Cross-sectional case-control | 30 (15 CD and 15 UC) | 47 | Appearance of periodontitis, gingivitis, BOP, other lesions | Higher rates of oral lesions in IBD group (87% CD, 93% UC, 55% control group). More periodontitis and BOP in CD compared to controls. | [88] |

| China | Cross-sectional case-control | 389 (265 CD and 124 UC) | 265 | DMFT, DMFS, PPD, CAL, BOP, GR, gingival index, plaque index, CAL | DMFS increased in IBD vs controls (OR 4.27 for CD, 2.21 for UC). Higher risk of dental caries, probing pocket depth ≥5mm, CAL ≥4mm in IBD group. | [89] |

| Studies of perceived oral health and behaviors | ||||||

| United States | Cross-sectional case-control | 880 (IBD type not specified) | 72,741 | Oral health questionnaire | Self-reported periodontal disease not associated with IBD. Poorer self-rated oral health and eating limitations due to teeth more common in IBD group (OR 1.15 and 1.22, respectively) | [30] |

| Sweden | Cross-sectional case-control | 1,598 (all CD) | 748 | Oral health questionnaire | IBD patients rate worse oral health and greater need for dental treatment after controlling for age, smoking, gender, and education. | [29] |

| United States | Cross-sectional case-control | 83 (57 CD and 26 UC) | 54 | Oral health questionnaire | Higher frequency of brushing and flossing at disease onset in IBD patients. More frequent dental visits, more caries. | [90] |

Abbreviations: BOP=bleeding on probing; CAL=calculus index; CD=Crohn’s disease; DMFS=decayed missing filled surfaces; DMFT=decayed missing filled teeth; DPSI=Dutch Periodontal Screening Index; GR=gingival recession; HR=hazard ratio; aHR=adjusted hazard ratio; IBD=inflammatory bowel disease; LA=loss of attachment; OR=odds ratio; PAI=periapical index; PBI=papilla bleeding index; PPD=probing pocket depth; RFT=root filled tooth; RPL=radiographic radiolucent periapical lesions; UC=ulcerative colitis

However, a major challenge in understanding the causal pathways implicated is that most epidemiologic studies of periodontal disease and IBD have been cross-sectional rather than longitudinal. Some of the larger cohort studies on this topic report mixed results. A retrospective cohort study in Korea showed that periodontal disease was associated with an increased risk of a new diagnosis of UC but not of CD[32]. In a 20,000-patient retrospective cohort from Sweden, poor dental hygiene and tooth loss were associated with lower risk of IBD; loss of 5–6 teeth was associated with a 50% lower risk of developing IBD, and high dental plaque burden was associated a 70% lower risk of development of CD, though plaque burden was not associated with UC[33]. In a Taiwanese cohort study of individuals with periodontitis, there was an increased risk of development of UC (adjusted hazard ratio 1.56) but not of CD[34]. Taken collectively, these studies suggest a link but that standardized prospective studies are needed.

Association between oralization of the gut microbiome and IBD

The link between periodontal disease and IBD is further supported by the changes seen in both the oral and gut microbiome of individuals with IBD[35, 36]. When compared to healthy controls, individuals with IBD have altered gut and salivary microbiomes, often referred to as dysbiosis. This is accompanied by failures of mucosal immunity and a loss of symbiotic relationships between bacteria and the human host, which leads to inflammation and illness[16]. One characteristic of the dysbiotic gut microbiome in IBD is a greater resemblance to the oral microbiome or “oralization” of the gut microbiome[37]. This includes enrichment of typically oral bacteria such as Fusobacteriaceae, Pasteurellaceae, Klebsiella spp. and Veillonellaceae and loss of more typical gut bacteria, like F. prausnitzii [2, 37–39]. Patients with IBD also experience salivary dysbiosis, with increased Bacteroidetes, which is associated increased salivary inflammatory cytokines[38]. Small studies have reported that salivary dysbiosis in IBD may correlate with IBD activity, suggesting a reciprocal relationship[40, 41].

Mechanisms

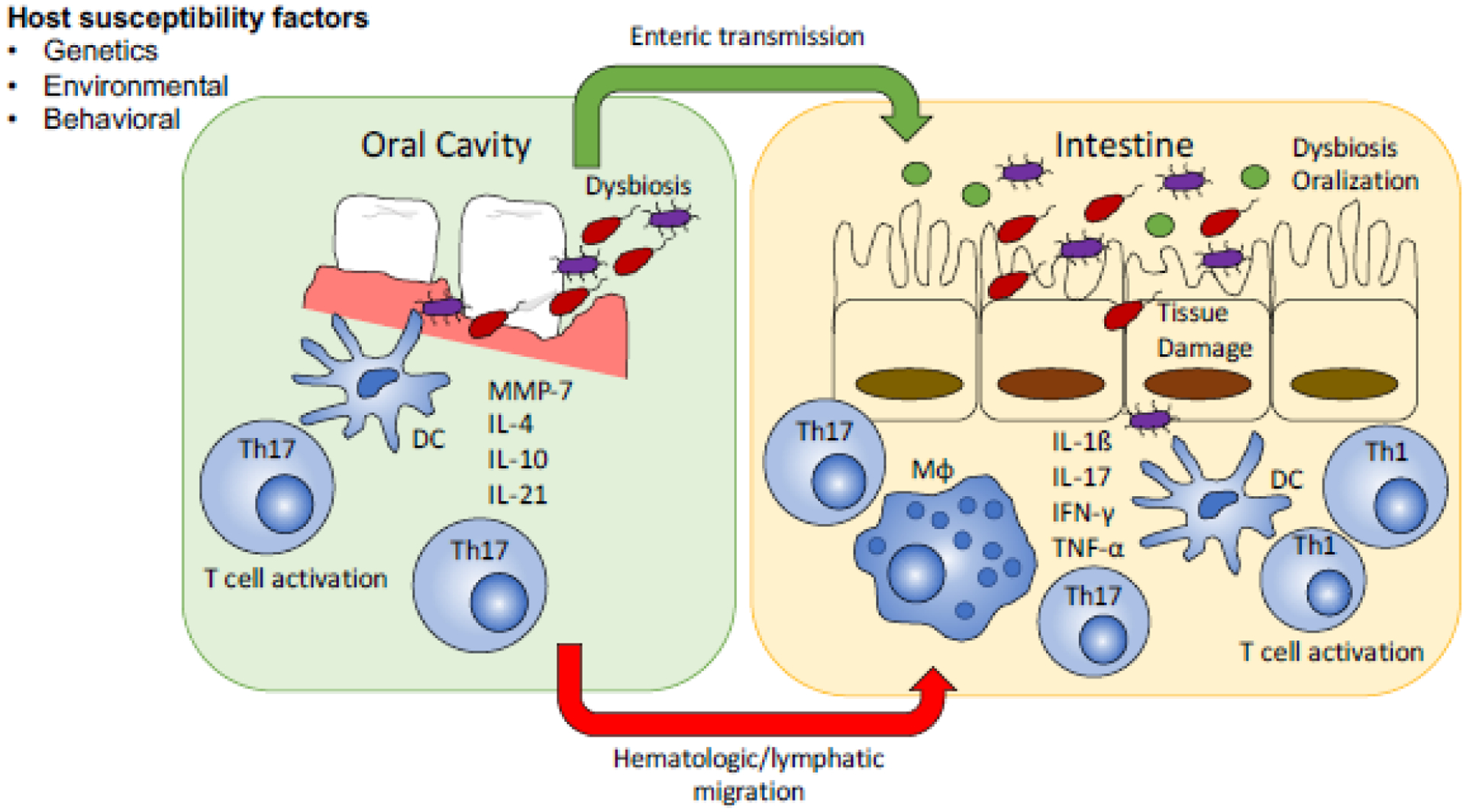

The mechanisms of oral-gut microbiome interaction in IBD are an area of active clinical and translational investigation. Current hypotheses are based off observations from translational research in humans and animal models of IBD. The working theory is that there are both direct and indirect pathways of oral-gut interaction that depend on both the microbiome and immune cell activation to synergistically promote inflammation in susceptible individuals (Figure 1). These may operate in a series of steps that gradually establish the conditions necessary for ectopic bacterial colonization and promote a hyperactive immune response[36].

Figure 1. Mechanisms of periodontal and intestinal inflammation.

In the setting of host factors that increase susceptibility periodontal disease with altered microbial communities and activation of inflammatory T cells through dendritic cell signaling can lead to intestinal inflammation. This occurs through enteric transmission of inflammatory microbes that lead to in situ T cell activation and through hematogenous and lymphatic migration of activated T-cells to the gut.

Abbreviations: DC=dendritic cell, IFN=interferon, IL=interleukin, MMP=matrix metalloprotease, Mφ=macrophage, Th=T-helper, TNF=tumor necrosis factor.

Underlying factors that may predispose to increased intestinal inflammation from periodontitis are not fully understood. However, a disruption or instability of the healthy microbiome is necessary to allow for ectopic gut colonization by oral pathobionts. Host genetic variants can alter immune response to pathogens, increase susceptibility to colonization with specific bacteria, and change the threshold for dysbiosis as opposed to self-resolution in response to an acute change[42–44]. Data from the spontaneous ileitis SAMP1/YitFc mouse model suggests that there may be genetic factors involved in the immune response that predispose to both IBD and periodontitis, as these mice exhibit severe periodontitis that correlates with intestinal inflammation[45]. This is supported by additional work that has identified shared susceptibility loci in both periodontitis and IBD, such as NOD2[43, 46]. Environmental factors such as diet, tobacco use, medications, and individual behaviors (e.g. dental care) may also contribute[47, 48].

In susceptible individuals, oral inflammation leads to large blooms of pathobionts, such as Klebsiella and Enterobacter species, that are swallowed and colonize the gut, displacing healthy gut microbes. IBD may increase the amount of oral bacterial exposure, as individuals with IBD and periodontitis harbor larger populations of oral pathobionts than healthy controls[40, 49, 50]. Possible reasons for altered oral microbiota in IBD include oral involvement of disease with ulceration and other histologic findings plus changes in salivary function[51]. Preexisting intestinal inflammation facilitates the colonization process by creating an environment that is more favorable to oral bacteria colonization, less diverse, and more unstable[41, 52].

The underlying conditions that lead to translocation of oral bacteria to the intestine and allow their survival in there are important active areas of study. Stomach acid and enzymes are potent antibacterials, but some bacteria can tolerate low pH environments and enzymatic exposure for limited periods of time [53]. Additionally, if there is a significantly large bacterial input, such as with the proliferation of oral pathobionts seen in periodontitis, some may survive through strain-specific features [54] or by protection within biofilms[55]. Finally, there may be hematogenous spread of bacteria as well.

Ectopic colonization of the gut by oral pathobionts activates the inflammasome and leads to local tissue damage. Data from mouse models have shown that the salivary microbiota from humans with periodontitis is pro-inflammatory in mice treated with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)[56]. One mechanism is through more epithelial permeability, which increases antigen exposure and immune activation[57]. In addition, saliva from CD and UC patients can cause intestinal inflammation in mice lacking an anti-inflammatory cytokine (interleukin (IL)-10) through Klebsiella spp.-induced dendritic cell signaling and Th1 activation[58]. In response to oral bacteria, there is CD4+ T cell accumulation in the intestinal mucosa of these mice, as is seen in humans with CD.

While some of these T cells may be in direct response to the presence of pathobionts, there are thought to be other mechanisms as well. Pathogenic T cells may arise from lymph nodes that drain the oral cavity and then transmigrate to other lymphoid tissues, such as those in the gut. A second source is through hematologic spread, by which T cells sensitized to oral pathobionts in the mouth can then home to the gut in response to the presence of similar bacteria. Prior work has shown that Th17-skewed T cells reactive against oral pathobionts arise in the mouth in response to periodontitis[59]. These are imprinted with intestinal tropism and migrate to the inflamed intestinal mucosa, where they are then activated by ectopic oral pathobionts, leading to further inflammation.

Though less-investigated than the T cell responses, periodontitis also causes neutrophil activation. Gingival calprotectin is associated with more aggressive periodontitis and is elevated in individuals with IBD when compared to healthy controls[60, 61]. In individuals with periodontitis, systemically circulating neutrophils have cytokine hyper-reactivity and impaired chemotaxis[62–64]. Hyper-reactive neutrophils in patients with periodontitis exhibit a type I interferon (IFN) pattern of cytokine expression. These primed and systemically circulating neutrophils express up-regulated phagocytic receptors and activity and have elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production[63]. When coupled with impaired chemotaxis, this may cause increased collateral damage to host tissues through increased transit time, though this has not yet been demonstrated in the gut. Thus, non-T immune cells, such as neutrophils, may also contribute to the oral-gut axis in the context of IBD.

An additional hypothesized mechanism linking IBD and periodontitis is through trained immunity[65]. Periodontitis can cause bacteremia and systemic circulation of bacterial components. In a mouse model simulating periodontitis-induced P. gingivalis bacteremia, this led to bone marrow changes in response to elevated serum IL-6[66]. Though the focus of the prior study was on bone loss, the finding of bone marrow-level effects of systemic inflammation from oral pathobionts suggests that these effects may also include effects on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) via inflammatory cytokine signaling[67]. HSPCs are essential for the production of neutrophils, dendritic cells, and macrophages, all of which have been implicated in IBD pathogenesis, though an experimental link between periodontitis and IBD via HSPCs has not yet been experimentally investigated.

Controversies

The main controversies in understanding the role of periodontitis in IBD are about causality, confounding, and the direction of the effect. Animal models indicate that oral inflammation and dysbiosis can promote intestinal inflammation in a susceptible host[59], however this has not been conclusively demonstrated in humans. As described previously, there are many epidemiologic studies that show an association between IBD and periodontitis, but there is a lack of well-designed prospective research to help understand whether periodontitis more often is a consequence of IBD or is a cause, if periodontitis can precipitate IBD flares, or if the association between the two conditions is the product of confounding by shared genetic, environmental, or immunologic risk factors (Table 2). The presence of incipient periodontitis may contribute to worse outcome in some CD patients[37]. However, in that study, patients enrolled were relatively few and heterogeneous in diagnosis, disease activity, and treatment. Therefore, prospective studies with more controlled study populations are required to assess the impact of periodontitis on IBD. A retrospective cohort study using the national Taiwanese health insurance database showed that individuals with CD were 36% more likely to develop periodontitis than individuals without IBD, highlighting the need for studies examining the association in both directions[68].

Table 2.

Risk factors for IBD and Periodontitis

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Environmental | Diet/nutrition |

| Tobacco use (Crohn’s disease only) | |

| Medications | |

| Stress | |

| Genetic | NOD2 |

| IL-10 | |

| IL-1 | |

| Autophagy genes | |

| Peroxidase genes | |

| Microbiome | Dysbiosis |

| Hygiene hypothesis | |

| Mucosal microbial load | |

| Immunologic | Immunodeficiencies |

Abbreviations: IL=interleukin; NOD2=Nucleotide Binding Oligomerization Domain Containing 2

Clinical implications

The clinical impact of both periodontal disease and IBD are substantial (see Clinician’s Corner). Emerging evidence around the interplay of these conditions highlights the importance of diagnosis and treatment of both. However, clinical data in this area are still lacking. There are no trials of the treatment of periodontal disease and IBD-related outcomes, but translational research suggests that periodontal disease treatment can reduce inflammation and improve oral microbiome composition. Prospective studies have shown that periodontal disease treatment reduced IFN-α levels, neutrophil IFN-signaling genes, and neutrophil ROS production[63, 69]. A similar study showed that neutrophil chemotaxis was improved by periodontal disease treatment, but there was no reduction in cytokine production[64]. Periodontitis treatment through mechanical biofilm removal leads to fewer disease-associated bacteria and decreases in inflammatory markers[70].

Clinician’s Corner:

Both periodontitis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are complex chronic conditions characterized by aberrant host immune response and dysregulated microbiota.

Emerging data show that periodontitis is associated with IBD, with higher rates of aggressive periodontitis among IBD patients even in adolescence and childhood. Recent studies have shown mechanistic links between periodontitis and intestinal inflammation. The inflammation and altered oral microbiome of periodontitis can worsen intestinal inflammation through direct and indirect immune activation. Oral bacteria are swallowed and may ectopically colonize the gut, leading to a pro-inflammatory gut microbiota that leads to inflammation and tissue damage. In addition, oral inflammation primes T cells which travel to the gut, leading to additional inflammation via a CD4+ T cell response.

There are limited data on the effects of periodontal disease treatment on IBD course and vice-versa, but early reports suggest that treatment of periodontitis decreases systemic immune activation and that treatment of IBD is associated with periodontitis healing.

In light of these newly recognized pathways and the high rates of periodontal disease among patients with IBD, it is important that dental assessments be included as part of comprehensive IBD and preventive health maintenance.

There are also no trials of IBD treatment and periodontal disease outcomes. However, a small study showed that treatment of IBD with an anti-TNF-alpha biologic was associated with an increased probability of periodontal disease healing[71]. This is an important finding, because it emphasizes the role of aberrant immune activation in both periodontal disease and IBD and its contribution to poor tissue healing. A study of individuals IBD but without identified periodontitis who were started on treatment for IBD showed improved salivary immunoglobulin A and myeloperoxidase in individuals with UC who responded to therapy, suggesting that there may be improvement in oral host defenses with IBD treatment[72].

Concluding Remarks

Epidemiologic, translational, and basic science research are beginning to illuminate the oral-gut connections behind periodontal disease and IBD. While it remains to be discovered the underlying pathways behind these links, a picture is emerging that incorporates the complex interplay between environmental, host, and microbiome factors. There is a need for future clinical innovation and rigorous study design to better understand this important area.

There is a need for large-scale, prospective observational and interventional studies to better characterize the natural history of periodontitis in individuals with IBD, the temporal relationship between periodontitis and IBD development and flares, and the effects of periodontal disease treatments and IBD treatments on disease outcomes. Further basic science research is needed to evaluate the role of neutrophils and other immune cell types in the oral-gut axis, interrogate the role of non-bacterial components of the microbiome, and clarify the mechanisms behind the observed associations (see Outstanding Questions).

Outstanding Questions:

Does the treatment of periodontitis reduce the risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease or reduce flares?

Does the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease reduce the risk of aggressive periodontitis?

What is the effect of preventive dental hygiene procedures on inflammatory bowel disease development and flares?

How do genetic and environmental factors contribute to both periodontal disease and inflammatory bowel disease?

What is the temporal relationship between oral and gut inflammation in IBD and periodontitis?

What environmental, immunologic, and microbiologic characteristics promote translocation and survival of oral bacteria in the intestine?

T cells have been relatively well studied, but what is the role of other immune cells in inflammation of the oral-gut axis?

What is the role of trained immunity in periodontitis and inflammatory bowel disease?

What specific factors make the oral microbiome in periodontitis pro-inflammatory in the intestinal environment? Is it specific to the presence of particular bacterial species or are there community-level metabolic or other features that drive immune activation?

Is there a role for non-bacterial components of the microbiome in exacerbating oral-gut axis inflammation?

Are there oral biomarkers with clinical utility for both periodontitis and inflammatory bowel disease?

Use of salivary biomarkers for IBD is an emerging area of research[73]. These include cytokines, microRNAs, oxidation markers and other molecules including calprotectin[73]. Prior microbiome research has also shown that the salivary microbiome can distinguish between individuals with and without IBD, with one study reporting an average area under the curve for saliva of 0.73[40]. Currently, no salivary IBD biomarkers are available for commercial testing.

In addition to bacteria, the microbiome is comprised of a diverse community of other organisms, including viruses and fungi (i.e. the virome and mycobiome). The investigation of their role in IBD and periodontitis is another important area for future research. Viruses and fungi have the potential to both directly interact with the host immune system and to modify the bacterial microbiome[74, 75]. IBD and periodontitis are associated with shifts in viral diversity and virome composition[76–78]. To date, studies have not examined the impact of these changes on the relationship between IBD and periodontitis.

Highlights:

Inflammatory bowel disease and periodontitis are associated in epidemiologic studies.

Both complex conditions involve microbial and host immune system interactions that create chronic inflammation and tissue damage in susceptible individuals.

Emerging evidence shows a link between oral inflammation and gut inflammation through direct and indirect mechanisms, including hematologic and lymphatic trafficking of activated T-cells and enteric transmission of inflammatory bacteria.

There is a need for prospective interventional research to determine the clinical implications of these findings.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK108901, DK125087, DK119219, AI142047 (to N.K.), and T32 DK094775 (to K.L.N).

Glossary:

- Dextran sulfate sodium

a chemical irritant used for mouse models of colitis. Mice administered dextran sulfate sodium in their drinking water develop colonic inflammation. The model is simple, widely used, and has similarities to human ulcerative colitis. However, it is an irritant colitis rather than a spontaneous autoimmune colitis.

- Dysbiosis

a state of imbalance or altered microbial composition of a microbiome from what is found in a healthy state, often associated with disease or illness.

- Inflammasome

a complex intracellular immune complex of multiple proteins that is activated in response to pathogens or other stressors.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

an idiopathic chronic inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract. Inflammatory bowel disease is typically subdivided into two major types: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, which are distinguished by histopathologic features and the areas of intestinal involvement.

- Microbiome

the community of microbes that reside in an environment, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other organisms.

- Pathobiont

a microbe that does not cause disease under normal circumstances but can be pathogenic under specific conditions or for susceptible hosts.

- Periodontitis

chronic inflammation affecting the bone and tissues around the tooth triggered by bacterial infiltration. Periodontitis is a serious condition that is thought to be the consequence of untreated less severe acute inflammation of the gums.

- Th1/Th2/Th17 cell immune response

broad categorizations of T-helper cell (Th) inflammatory responses. These responses are based on the types of cytokines produced and the immune function of the cells. Th1 cells typically produce interleukin (IL)-2 and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and are involved in cell-mediated immunity. Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and are involved in antibody-mediated immunity. Th17 cells produce IL-17 and are important for activating the immune response.

- Trained immunity

increased immunologic responsiveness to pathogens resulting from epigenetic and metabolic changes following early microbial exposures. Trained immunity arises through priming of bone marrow hematopoietic progenitor cells. These give rise to myeloid cells, which include basophils, dendritic cells, eosinophils, macrophages, and neutrophils. Trained immunity is adaptive in fighting reinfection, but it may increase chronic inflammation and cause or exacerbate autoimmune diseases.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures:

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Peres MA et al. (2019) Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet 394 (10194), 249–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitamoto S et al. (2020) The Bacterial Connection between the Oral Cavity and the Gut Diseases. J Dent Res 99 (9), 1021–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin LJ et al. (2016) Global burden of oral diseases: emerging concepts, management and interplay with systemic health. Oral Dis 22 (7), 609–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcenes W et al. (2013) Global burden of oral conditions in 1990–2010: a systematic analysis. J Dent Res 92 (7), 592–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kassebaum NJ et al. (2014) Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990–2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. J Dent Res 93 (11), 1045–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eke PI et al. (2020) Recent epidemiologic trends in periodontitis in the USA. Periodontol 2000 82 (1), 257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dye BA (2012) Global periodontal disease epidemiology. Periodontol 2000 58 (1), 10–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kassebaum NJ et al. (2014) Global Burden of Severe Tooth Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Dent Res 93 (7 Suppl), 20S–28S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gjermo PE (2005) Impact of periodontal preventive programmes on the data from epidemiologic studies. J Clin Periodontol 32 Suppl 6, 294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hugoson A et al. (2008) Trends over 30 years, 1973–2003, in the prevalence and severity of periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 35 (5), 405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skudutyte-Rysstad R et al. (2007) Trends in periodontal health among 35-year-olds in Oslo, 1973–2003. J Clin Periodontol 34 (10), 867–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ankkuriniemi O and Ainamo J (1997) Dental health and dental treatment needs among recruits of the Finnish Defence Forces, 1919–91. Acta Odontol Scand 55 (3), 192–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalsbeek H et al. (2000) Trends in periodontal status and oral hygiene habits in Dutch adults between 1983 and 1995. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 28 (2), 112–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demmer RT and Papapanou PN (2010) Epidemiologic patterns of chronic and aggressive periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 53, 28–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo LS et al. (2021) Secular trends in severe periodontitis incidence, prevalence and disability-adjusted life years in five Asian countries: A comparative study from 1990 to 2017. J Clin Periodontol 48 (5), 627–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caruso R et al. (2020) Host-microbiota interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol 20 (7), 411–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brand S (2009) Crohn’s disease: Th1, Th17 or both? The change of a paradigm: new immunological and genetic insights implicate Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease. Gut 58 (8), 1152–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dahlhamer JM et al. (2016) Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Among Adults Aged >/=18 Years - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65 (42), 1166–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mak WY et al. (2020) The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: East meets west. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 35 (3), 380–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collaborators GBDIBD (2020) The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 5 (1), 17–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shivashankar R et al. (2017) Incidence and Prevalence of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota From 1970 Through 2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 15 (6), 857–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bitton A et al. (2014) Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Quebec: recent trends. Inflamm Bowel Dis 20 (10), 1770–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HJ et al. (2015) Incidence and natural course of inflammatory bowel disease in Korea, 2006–2012: a nationwide population-based study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 21 (3), 623–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng SC et al. (2013) Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn’s and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology 145 (1), 158–165 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorenzo-Pouso AI et al. (2021) Association between periodontal disease and inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Odontol Scand 79 (5), 344–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.She YY et al. (2020) Periodontitis and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 20 (1), 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y et al. (2021) The Association between Periodontitis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int 2021, 6692420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koutsochristou V et al. (2015) Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease in Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Case-Control Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 21 (8), 1839–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rikardsson S et al. (2009) Perceived oral health in patients with Crohn’s disease. Oral Health Prev Dent 7 (3), 277–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kato I et al. (2020) History of Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Self-Reported Oral Health: Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 29 (7), 1032–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johannsen A et al. (2015) Consumption of dental treatment in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, a register study. PLoS One 10 (8), e0134001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang EA et al. (2020) Periodontitis combined with smoking increases risk of the ulcerative colitis: A national cohort study. World J Gastroenterol 26 (37), 5661–5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin W et al. (2017) Inverse Association Between Poor Oral Health and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 15 (4), 525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin CY et al. (2018) Increased Risk of Ulcerative Colitis in Patients with Periodontal Disease: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15 (11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kitamoto S and Kamada N (2022) Periodontal connection with intestinal inflammation: Microbiological and immunological mechanisms. Periodontol 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Read E et al. (2021) The role of oral bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 18 (10), 731–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Imai J et al. (2021) A potential pathogenic association between periodontal disease and Crohn’s disease. JCI Insight 6 (23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Said HS et al. (2014) Dysbiosis of salivary microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease and its association with oral immunological biomarkers. DNA Res 21 (1), 15–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai Z et al. (2021) Co-pathogens in Periodontitis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Med (Lausanne) 8, 723719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Somineni HK et al. (2021) Site- and Taxa-Specific Disease-Associated Oral Microbial Structures Distinguish Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 27 (12), 1889–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu S et al. (2021) Ectopic gut colonization: a metagenomic study of the oral and gut microbiome in Crohn’s disease. Gut Pathog 13 (1), 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loos BG et al. (2005) Identification of genetic risk factors for periodontitis and possible mechanisms of action. J Clin Periodontol 32 Suppl 6, 159–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sudo T et al. (2017) Association of NOD2 Mutations with Aggressive Periodontitis. J Dent Res 96 (10), 1100–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shaddox LM et al. (2021) Periodontal health and disease: The contribution of genetics. Periodontol 2000 85 (1), 161–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pietropaoli D et al. (2014) Occurrence of spontaneous periodontal disease in the SAMP1/YitFc murine model of Crohn disease. J Periodontol 85 (12), 1799–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramanan D et al. (2014) Bacterial sensor Nod2 prevents inflammation of the small intestine by restricting the expansion of the commensal Bacteroides vulgatus. Immunity 41 (2), 311–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piovani D et al. (2019) Environmental Risk Factors for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses. Gastroenterology 157 (3), 647–659 e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kinane DF et al. (2006) Environmental and other modifying factors of the periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000 40, 107–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brito F et al. (2013) Subgingival microflora in inflammatory bowel disease patients with untreated periodontitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 25 (2), 239–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang T et al. (2020) Dynamics of the Salivary Microbiome During Different Phases of Crohn’s Disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10, 544704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Vries SAG et al. (2018) Salivary Function and Oral Health Problems in Crohn’s Disease Patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis 24 (6), 1361–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lloyd-Price J et al. (2019) Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature 569 (7758), 655–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tennant SM et al. (2008) Influence of gastric acid on susceptibility to infection with ingested bacterial pathogens. Infect Immun 76 (2), 639–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Bokhorst-van de Veen H et al. (2012) Congruent strain specific intestinal persistence of Lactobacillus plantarum in an intestine-mimicking in vitro system and in human volunteers. PLoS One 7 (9), e44588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang X et al. (2020) Bioinspired oral delivery of gut microbiota by self-coating with biofilms. Sci Adv 6 (26), eabb1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qian J et al. (2021) Periodontitis Salivary Microbiota Worsens Colitis. J Dent Res, 220345211049781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsuzuno T et al. (2021) Ingestion of Porphyromonas gingivalis exacerbates colitis via intestinal epithelial barrier disruption in mice. J Periodontal Res 56 (2), 275–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Atarashi K et al. (2017) Ectopic colonization of oral bacteria in the intestine drives TH1 cell induction and inflammation. Science 358 (6361), 359–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kitamoto S et al. (2020) The Intermucosal Connection between the Mouth and Gut in Commensal Pathobiont-Driven Colitis. Cell 182 (2), 447–462 e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaner D et al. (2011) Calprotectin levels in gingival crevicular fluid predict disease activity in patients treated for generalized aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontal Res 46 (4), 417–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Majster M et al. (2019) Salivary calprotectin is elevated in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Oral Biol 107, 104528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ling MR et al. (2015) Peripheral blood neutrophil cytokine hyper-reactivity in chronic periodontitis. Innate Immun 21 (7), 714–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wright HJ et al. (2008) Periodontitis associates with a type 1 IFN signature in peripheral blood neutrophils. J Immunol 181 (8), 5775–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roberts HM et al. (2015) Impaired neutrophil directional chemotactic accuracy in chronic periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol 42 (1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hajishengallis G and Chavakis T (2021) Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat Rev Immunol 21 (7), 426–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao Y et al. (2020) Characterization and regulation of osteoclast precursors following chronic Porphyromonas gingivalis infection. J Leukoc Biol 108 (4), 1037–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.King KY and Goodell MA (2011) Inflammatory modulation of HSCs: viewing the HSC as a foundation for the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol 11 (10), 685–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chi YC et al. (2018) Increased risk of periodontitis among patients with Crohn’s disease: a population-based matched-cohort study. Int J Colorectal Dis 33 (10), 1437–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Matthews JB et al. (2007) Neutrophil hyper-responsiveness in periodontitis. J Dent Res 86 (8), 718–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Johnston W et al. (2021) Mechanical biofilm disruption causes microbial and immunological shifts in periodontitis patients. Sci Rep 11 (1), 9796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cotti E et al. (2018) Healing of Apical Periodontitis in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and under Anti-tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha Therapy. J Endod 44 (12), 1777–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nijakowski K et al. (2021) Changes in Salivary Parameters of Oral Immunity after Biologic Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Life (Basel) 11 (12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nijakowski K and Surdacka A (2020) Salivary Biomarkers for Diagnosis of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci 21 (20). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hoarau G et al. (2016) Bacteriome and Mycobiome Interactions Underscore Microbial Dysbiosis in Familial Crohn’s Disease. mBio 7 (5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liang G and Bushman FD (2021) The human virome: assembly, composition and host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol 19 (8), 514–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gao L et al. (2020) Polymicrobial periodontal disease triggers a wide radius of effect and unique virome. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 6 (1), 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Clooney AG et al. (2019) Whole-Virome Analysis Sheds Light on Viral Dark Matter in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cell Host Microbe 26 (6), 764–778 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ly M et al. (2014) Altered oral viral ecology in association with periodontal disease. mBio 5 (3), e01133–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brito F et al. (2008) Prevalence of periodontitis and DMFT index in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J Clin Periodontol 35 (6), 555–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grossner-Schreiber B et al. (2006) Prevalence of dental caries and periodontal disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. J Clin Periodontol 33 (7), 478–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Habashneh RA et al. (2012) The association between inflammatory bowel disease and periodontitis among Jordanians: a case-control study. J Periodontal Res 47 (3), 293–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Piras V et al. (2017) Prevalence of Apical Periodontitis in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Retrospective Clinical Study. J Endod 43 (3), 389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Poyato-Borrego M et al. (2020) High Prevalence of Apical Periodontitis in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Age- and Gender- matched Case-control Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 26 (2), 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schmidt J et al. (2018) Active matrix metalloproteinase-8 and periodontal bacteria-interlink between periodontitis and inflammatory bowel disease? J Periodontol 89 (6), 699–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Szymanska S et al. (2014) Dental caries, prevalence and risk factors in patients with Crohn’s disease. PLoS One 9 (3), e91059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tan CXW et al. (2021) Dental and periodontal disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Oral Investig 25 (9), 5273–5280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vavricka SR et al. (2013) Periodontitis and gingivitis in inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19 (13), 2768–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zervou F et al. (2004) Oral manifestations of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Annals of Gastroenterology 17 (4), 395–401. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang L et al. (2020) Increased risks of dental caries and periodontal disease in Chinese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Int Dent J 70 (3), 227–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Singhal S et al. (2011) The role of oral hygiene in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 56 (1), 170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]