Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2’s (SARS-CoV-2) rapid global spread has posed a significant threat to human health, and similar outbreaks could occur in the future. Developing effective virus inactivation technologies is critical to preventing and overcoming pandemics. The infection of SARS-CoV-2 depends on the binding of the spike glycoprotein (S) receptor binding domain (RBD) to the host cellular surface receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). If this interaction is disrupted, SARS-CoV-2 infection could be inhibited. Magnetic nanoparticle (MNP) dispersions exposed to an alternating magnetic field (AMF) possess the unique ability for magnetically mediated energy delivery (MagMED); this localized energy delivery and associated mechanical, chemical, and thermal effects are a possible technique for inactivating viruses. This study investigates the MNPs’ effect on vesicular stomatitis virus pseudoparticles containing the SARS-CoV-2 S protein when exposed to AMF or a water bath (WB) with varying target steady-state temperatures (45, 50, and 55 °C) for different exposure times (5, 15, and 30 min). In comparison to WB exposures at the same temperatures, AMF exposures resulted in significantly greater inactivation in multiple cases. This is likely due to AMF-induced localized heating and rotation of MNPs. In brief, our findings demonstrate a potential strategy for combating the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic or future ones.

Keywords: magnetic nanoparticles, alternating magnetic field, SARS-CoV-2, virus inactivation, COVID-19

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The outbreak of COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) in China during late 2019 soon transformed into a global pandemic with devastating implications. In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the disease as a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). COVID-19 is caused by an infection with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). SARS-CoV-2 is a spherical enveloped beta coronavirus with a diameter of 120 nm.1 This virus has four structural proteins: S, E, M, and N. The spike glycoprotein (S) is made up of two functional subunits, S1 and S2. The S1 subunit is composed of an N-terminal domain (NTD) and a receptor binding domain (RBD), and the S2 subunit contains a fusion peptide (FP), heptad repeat 1 (HR1), central helix (CH), connector domain (CD), heptad repeat 2 (HR2), transmembrane domain (TM), and cytoplasmic tail (CT). To enter a host cell, SARS-CoV-2 RBD, from the S1 subunit, must recognize the host cell surface receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), triggering a fusion event and beginning the infectious cycle. Interrupting the interaction between the spike RBD and ACE2 could be effective in preventing infection, making the RBD a critical target for antiviral compounds and antibodies.2–5

Researchers have investigated physical and chemical methods for inactivating SARS-CoV-2 with varying degrees of success. The physical inactivation of viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, by heating is a widely used technique involving the denaturation of viral proteins, which disrupts structure and attachment, impeding replication in the host cell.6–8 A recent study explored chemical inactivation with plasma-activated water, and the data suggests that the reactive species in plasma-activated water interacted with amino acids of the RBD, inducing oxidative modification, aggregation, and fragmentation, resulting in the inactivation of the RBD.9 Thus far, the use of magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) to inactivate SARS-CoV-2, using alternating magnetic field (AMF), has not been investigated. It is possible that a combination of physical and chemical effects, caused by MNPs when exposed to AMF, could inactivate SARS-CoV-2 viral particles.

MNPs show a variety of unique and novel properties. They are comparable in size to a wide variety of biological molecules (e.g., proteins, DNA, RNA), which enables them to readily interact with these biological entities. In addition, MNPs exhibit superparamagnetic properties that can vary with temperature. These superparamagnetic properties allow them to be manipulated in an external magnetic field without a net remanent magnetization once the external magnetic field is removed. When MNPs are exposed to an AMF, they absorb energy and convert it to heat through the processes of Neel and Brownian relaxation.10–13 In addition, the AMF can cause physical effects by the MNPs on surrounding media resulting from the rotational motion and cause enhanced surface reactivity of the MNPs due to the energy release from the surface and potential local temperature rise. In fact, Polo-Corrales and Rinaldi demonstrated that the surface temperature of MNPs is higher than the temperature of the liquid in the AMF application.14 In another study, Vlasova et al. showed the release of fluorescent dye (calcein) from magnetic liposomes in the presence of AMF.15 In this work, they proposed that the AMF application would cause MNPs embedded in the lipid membrane to cluster, thereby enhancing the force and deformations exerted by oscillation of the MNPs. The oscillating motion of MNPs embedded in gel phase lipid membranes disrupts the lipid packaging, increasing permeability or rupturing the membrane. As the temperature rises, the probability of such a transition increases as well. In a similar study, Qiu and An demonstrated that AMF can induce cargo release from liposomes containing MNPs embedded in the membrane, which they demonstrated was caused by a reversible and controllable change in the bilayer’s permeability, rather than liposome destruction.16 Other studies also showed that AMF induced magnetic hyperthermia led to necrotic cell death.17,18 Moreover, MNPs in the presence of hydrogen peroxide alone generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) via Fenton-like chemistry, and in AMF applications, the ROS generation increases.11 This high ROS generation in combination with hyperthermia can result in a significant therapeutic response. For example, heat stress and ROS production in the cellular environment damages DNA, and this combined effect can be utilized for targeted cancerous cell death.19–21

In this study, we investigated the ability of MNPs excited by AMF to inactivate SARS-CoV-2, likely through the spike protein. Because SARS-CoV-2 is a BSL-3 pathogen, we utilized the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) pseudotyping system.22 VSV is a bullet shaped rhabdovirus, which is roughly 160–200 nm in length and 80 nm in diameter (Figure 1). VSV utilizes its glycoprotein (VSV G) to promote binding and entry of host-cell low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) upon infection. When using VSV for a pseudotype system, a modified VSV genome is used, which contains all of the viral proteins required for propagation, except the glycoprotein, and encodes an additional green fluorescent protein gene (GFP) for downstream visualization (VSVΔG-GFP). This process results in a VSVΔG-GFP-spike pseudoparticle that is safe for a BSL-2 laboratory (Figure 2). The ability of VSVΔG-GFP-spike (VSVΔG-GFP-S) particles to enter host cells can be measured by utilizing fluorescent microscopy to visualize and quantify GFP production (provided in the VSVΔG genome), which can be further quantified. The wild-type (WT) S protein or desired mutants (such as mutations observed in circulating strains) could be incorporated into the VSV-pseudotype to create particles that present the SARS-CoV-2 S protein on the particle surface.

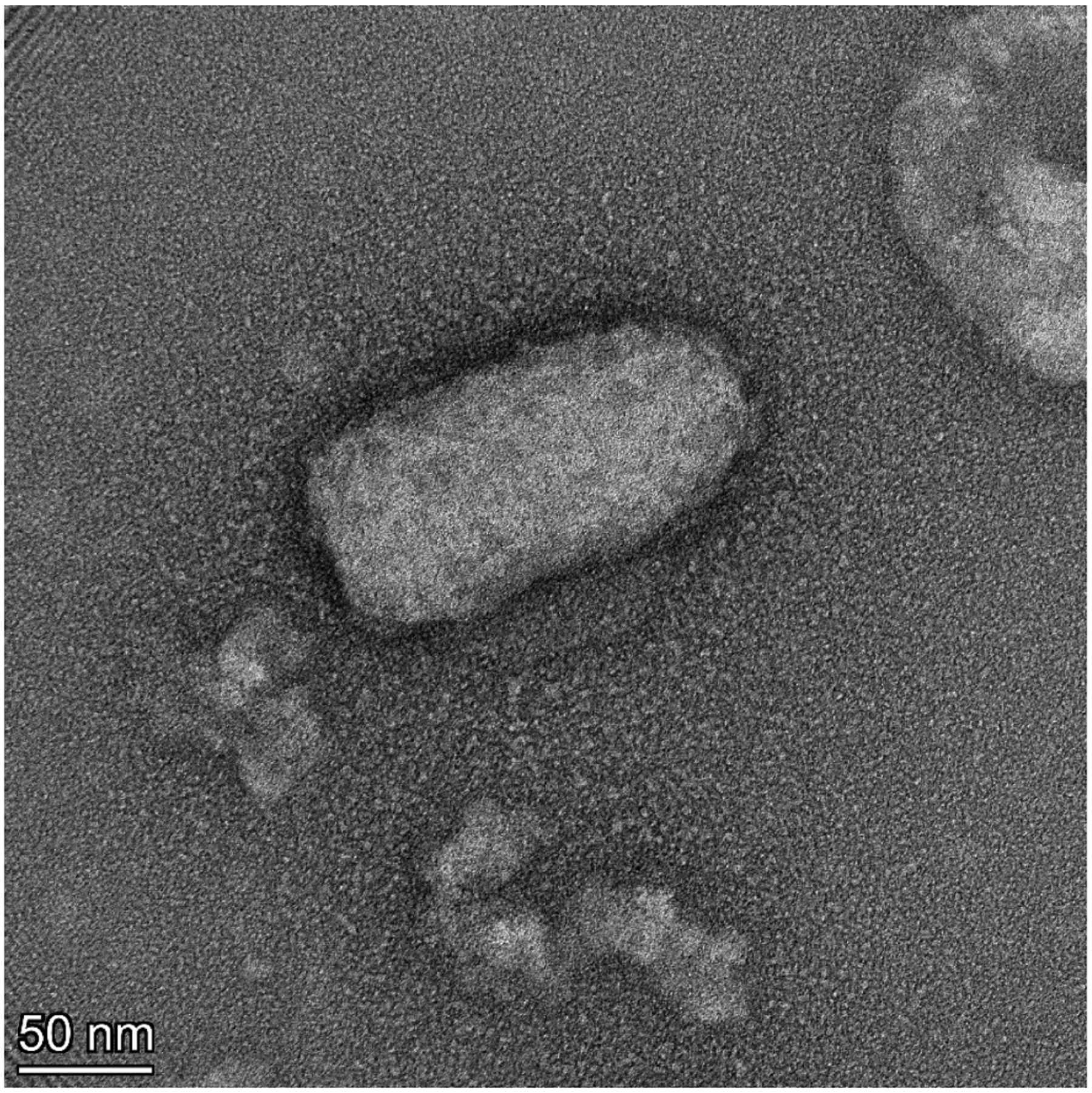

Figure 1.

Negative stain TEM image of VSV pseudovirus. Intact bullet shaped particle of VSVΔG-GFP-G measuring ~160 nm × ~80 nm. The roughness around the edges of the particles is likely the not fully resolved structure of G proteins on the pseudoparticle surface.

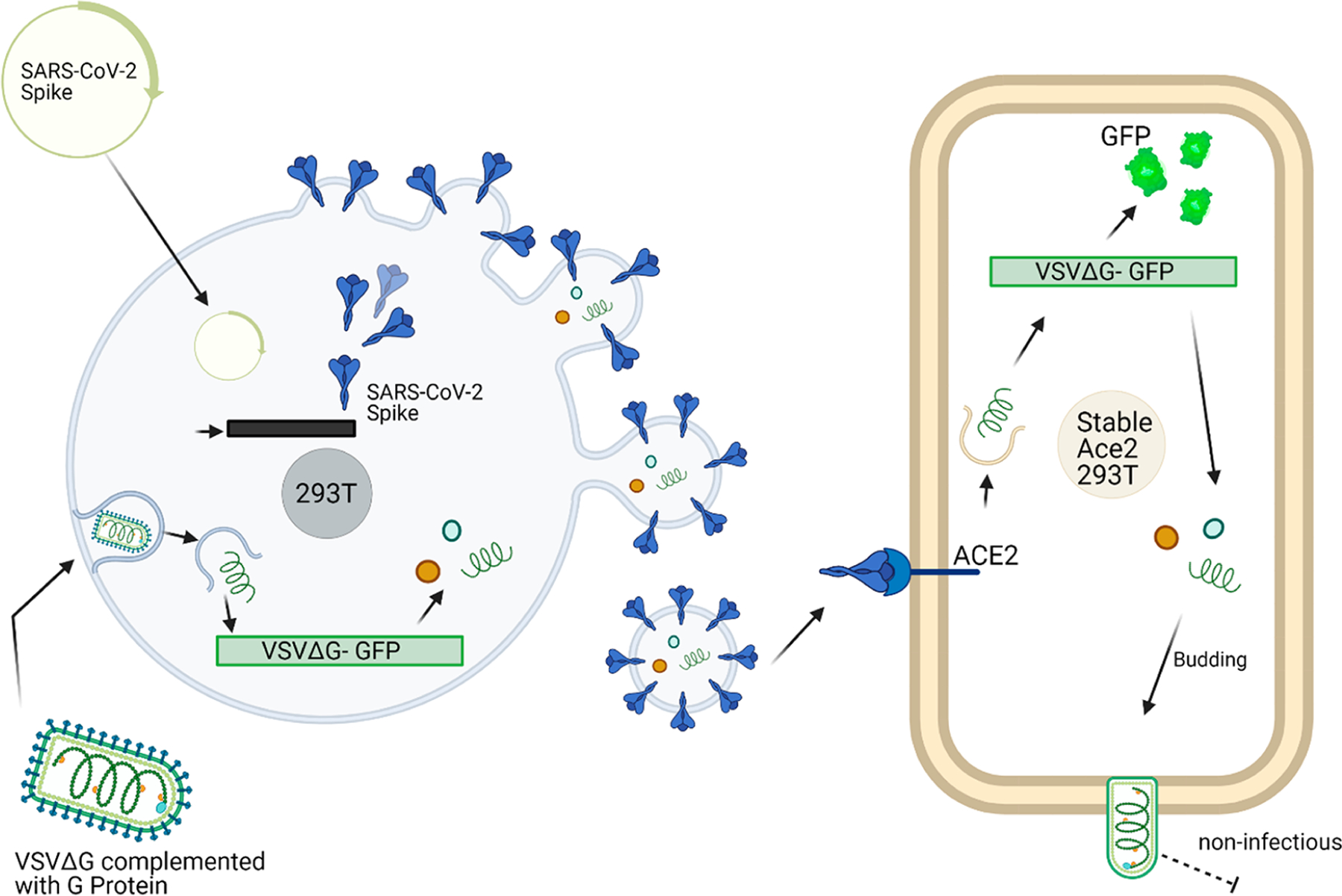

Figure 2.

Pseudotype system. The VSVΔG-GFP-spike pseudotype system is created using a transient transfection of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein followed by VSVΔG-GFP-G transduction. This process results in spike surface protein imbedded particles capable of downstream transduction via the ACE2 receptor but cannot propagate. The green fluorescent protein production can then be visualized via fluorescent microscopy. Created using BioRender.com.

VSV pseudotype systems are a common technique utilized in research studies concerning SARS-CoV-2, including studies of viral entry and inhibition by neutralizing antibodies.23–25 In a recent study, Baldridge et al. used the VSVΔG complimented with G protein to study viral particle separation through aerosolization.26 Treatments on pseudoparticles that result in proteolytic loss or unfolding of the S protein on the particle surface will reduce or abolish particle binding and cell entry. These alterations can be analyzed using the pseudoviral titer assays, visualizing GFP production.

MNPs with the aforementioned physical and chemical properties can be utilized to inactivate SARS-CoV-2 S protein with exposure to AMF heating effects by protein misfolding as well as the potential physical and chemical effects discussed above. In this study, the inactivation of pseudoparticles containing SARS-CoV-2 S protein using MNPs exposed to AMF or a water bath (WB) with varying exposure times and MNP concentrations was studied via pseudovirus transduction assays.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Here, we synthesized and characterized MNPs and exposed them to a WB or AMF to inactivate pseudoparticles containing the SARS-CoV-2 S protein. The experimental procedure for the inactivation study is represented in Figure 3. Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the results of the MNP characterization, including dynamic light scattering (DLS) for particle size distribution and zeta potential, and specific absorption rate (SAR) values after the exposure to an AMF with an amplitude of 44.43 kA/m. Additionally, Figures S1 and S2 show the particle distribution profile of MNPs and the SAR calculation plots, respectively. Moreover, Table S1 compares the particle size and zeta potential of MNPs in DI water and TNE buffer, showing that MNPs aggregate more in the TNE buffer than in DI water.

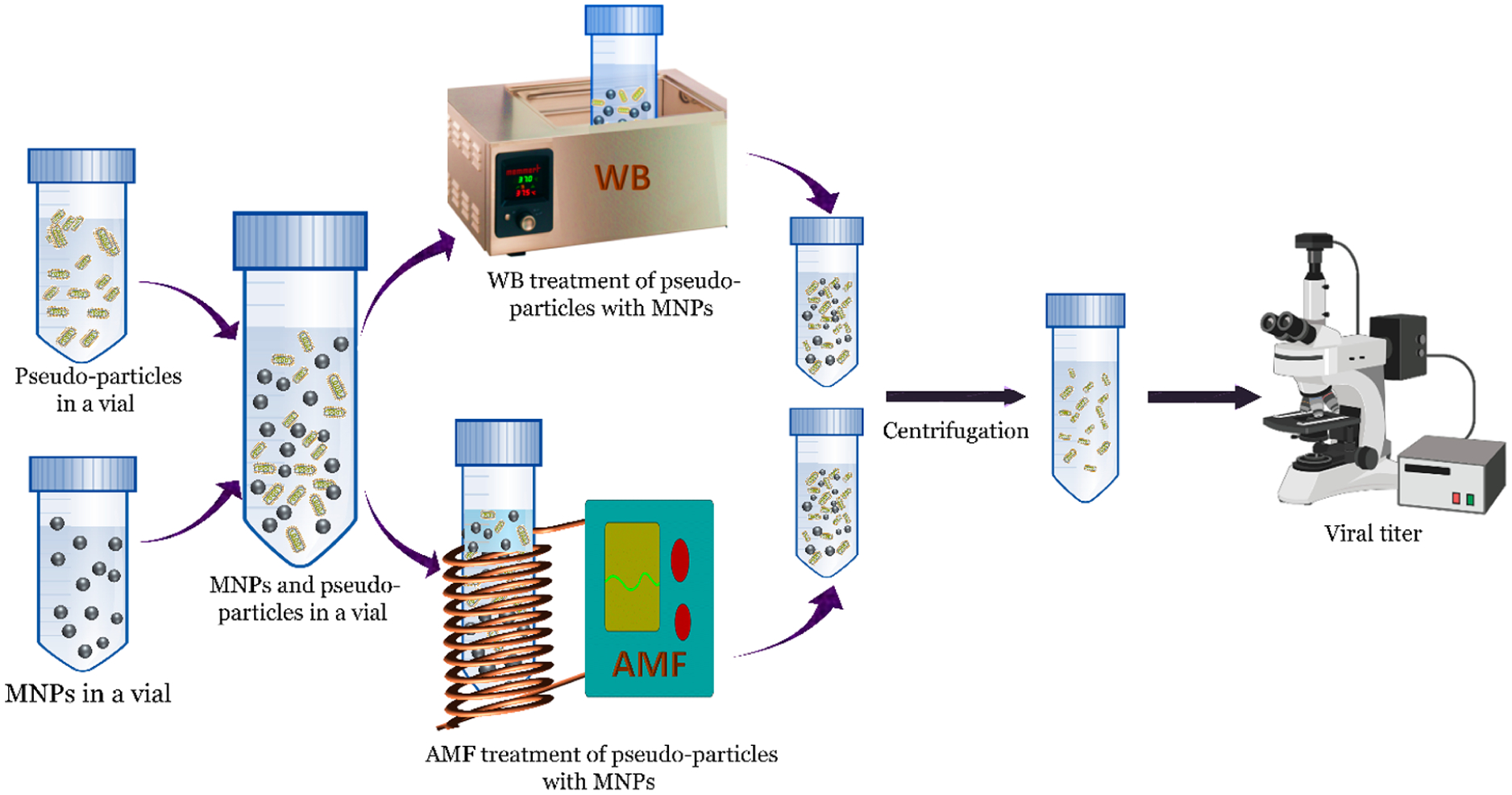

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the overall treatment of MNPs with a WB and AMF to inactivate pseudoparticles containing SARS CoV-2 S protein. Created using BioRender.com.

Table 1.

Particle Size and Zeta Potential of the 1.2 mg/mL MNP Concentration in TNE Buffer

| particle size diameter (nm) | Zeta potential (mV) | |

|---|---|---|

| hydrodynamic diameter | 2896 ± 502 | −8.5 ± 0.887 |

| intensity distribution peak | 2495 ± 504 | |

| volume distribution peak | 2131 ± 516 | |

| number distribution peak | 2216 ± 513 |

Table 2.

Characterization Results of Different MNP Concentration in TNE Buffer in AMF

| concentration (mg/mL) | SAR value (W/g) | steady-state temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.8 | 270 ± 57 | 45 ± 0.90 |

| 1.2 | 272 ± 52 | 50 ± 0.84 |

| 1.7 | 275 ± 40 | 55 ± 1.15 |

To determine the viability of AMF or WB treatments for inactivating viruses, pseudoparticles containing SARS-CoV-2 S protein were mixed with MNPs and exposed to AMF or WB, and active transducible pseudoparticles were analyzed using the viral titer assay following treatment. The temperature profiles of MNPs mixed with TNE buffer during AMF or WB exposure as well as the titer levels for pseudoparticles following AMF or WB exposure at three target steady-state temperatures (45 50, and 55 °C) are shown in Figures 4, 5, and 6.

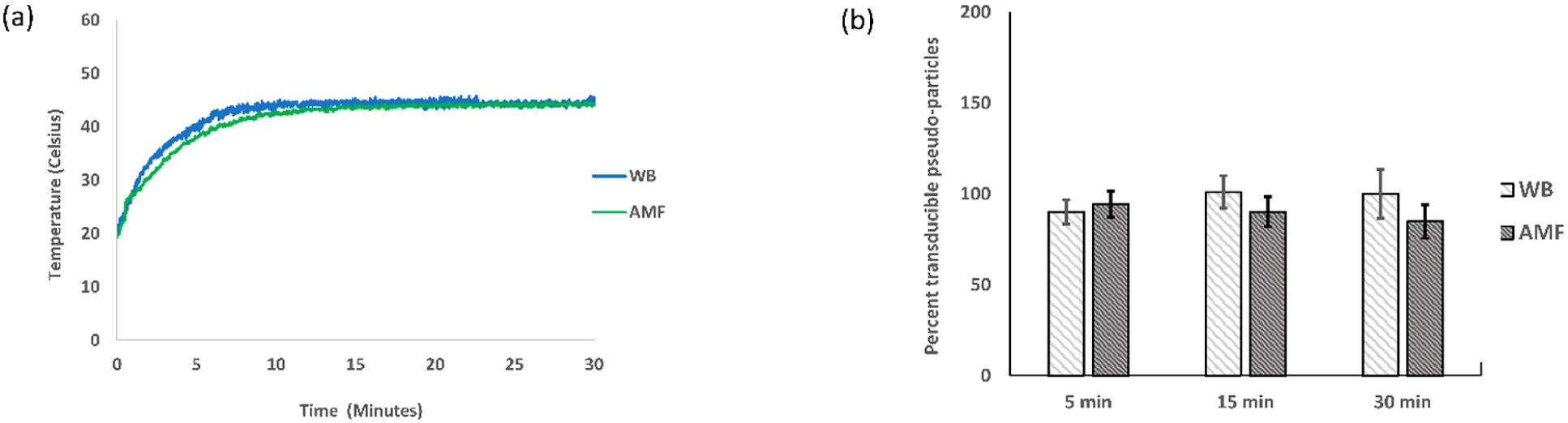

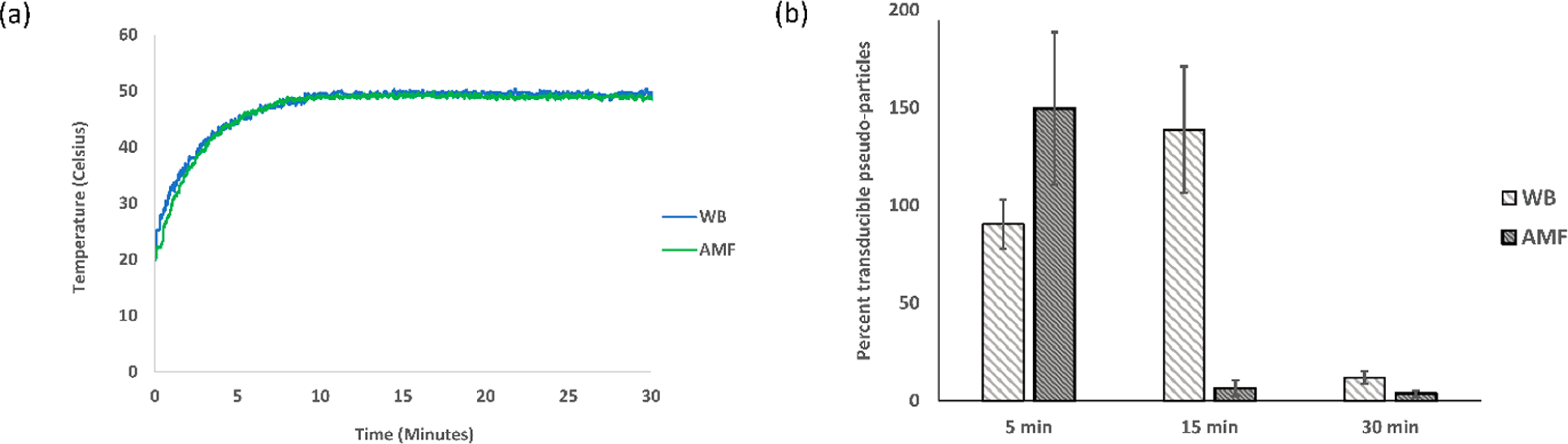

Figure 4.

Temperature profile and transduction assay at 45 °C. The experiment was replicated three times (N = 3), and the average and standard errors were used for plotting (a) the temperature profile of the sample (0.8 mg/mL MNPs and TNE buffer) in a WB with a set temperature of 45 °C and in an AMF of strength 44.43 kA/m and 292 kHz; (b) the percent transduction of pseudoparticles in a 45 °C water bath (WB) and alternating magnetic field (AMF).

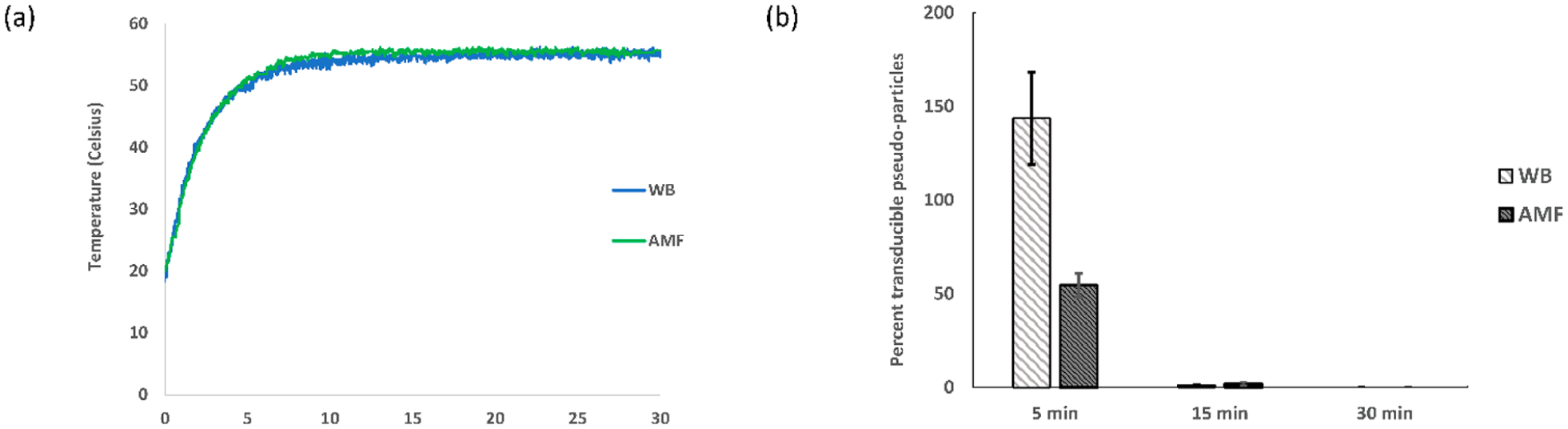

Figure 5.

Temperature profile and transduction assay at 50 °C. The experiment was replicated three times (N = 3), and the average and standard error were used for plotting (a) the temperature profile of the sample (1.2 mg/mL MNPs and TNE buffer) in a WB with a set temperature of 50 °C and in an AMF of strength 44.43 kA/m and 292 kHz; (b) the percent transduction of pseudoparticles in a 50 °C water bath (WB) and alternating magnetic field (AMF).

Figure 6.

Temperature profile and transduction assay at 55 °C. The experiment was replicated three times (N = 3), and the average and standard error were used for plotting (a) the temperature profile of the sample (1.7 mg/mL MNPs and TNE buffer) in a WB with a set temperature of 55 °C and in an AMF of strength 44.43 kA/m and 292 kHz; (b) the percent transduction of pseudoparticles in a 55 °C water bath (WB) and alternating magnetic field (AMF).

Negligible to no inactivation of pseudoparticles was found following AMF treatment without MNPs (Figure S3), and minimal inactivation was observed with the addition of MNPs (Figure S4). The MNP impact did not follow a trend with increasing concentration, and it likely resulted from variable physical removal of a fraction of the pseudoparticles during the centrifugation step used to separate the MNPs prior to the transduction assay. For the quantification of the impact of the WB and AMF treatments, the transducible pseudoparticles reported in Figures 4, 5, and 6 are normalized to the samples exposed only to MNPs without WB/AMF treatment and reported as a percentage. For the 45 °C case (Figure 4b), neither AMF nor WB treatments had a significant effect on the transduction. In a couple cases at low treatment times for 50 and 55 °C, the percent transduction is greater than 100%, which is likely not a real effect due to the limited number of samples and inherent variability of the assay. Following AMF treatment at 50 °C for 15 and 30 min, a notable inactivation of pseudoparticles resulted, which is also significantly greater than that observed with WB treatment (Figure 5b). Similarly, 5 min of a 55 °C temperature exposure of AMF was found to have a greater impact on transduction of the pseudoparticles when compared to the WB (Figure 6b). The 15 and 30 min exposures at 55 °C resulted in approximately complete inactivation and complete inactivation (within detectable limit of the titer assays), respectively, for both the WB and AMF (Figure 6b).

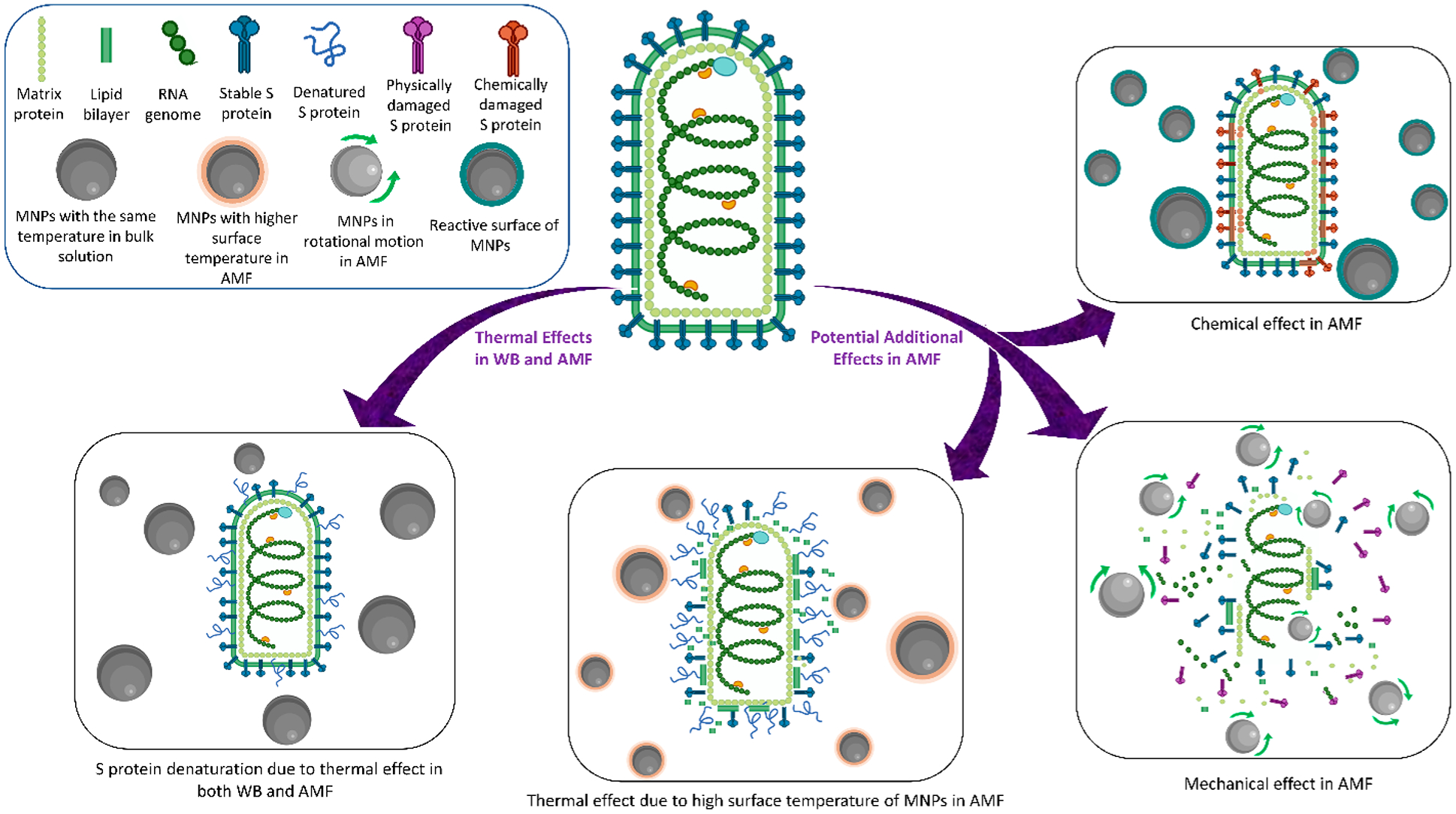

Inactivation of pseudoparticles in a WB is likely caused by thermally induced protein denaturation, leading to decreased transduction efficiency.6,27–29 The enhanced inactivation in AMF compared to WB with matched conditions may be a result of one or more of the following possible AMF-induced interactions of the MNPs with the pseudoparticles: (i) mechanical impacts to the virus structure due to the rotational aspects of the MNPs in AMF application; (ii) pseudoparticles near the surface of MNPs exposed to higher temperatures than the bulk solution; (iii) local enhanced reactivity (e.g., ROS generation) at the surface of the MNPs. In Figure 7, we summarize these hypothesized effects under AMF exposure and contrast them to the thermal effects that would dominate in the WB treatment. The specific mechanisms of enhancement in the AMF treatment as well as the possibility of further enhancing the inactivation with a coating on the surface of the MNPs that specifically binds SARS-CoV-2 S protein or potentially other target virus proteins will be the focus of future studies.

Figure 7.

Illustration of the pseudoparticle inactivation mechanism in WB and AMF exposure with MNPs. Created using BioRender.com.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, MNPs and pseudoparticles containing SARS-CoV-2 S protein were successfully synthesized and characterized. Pseudoparticles were mixed with MNPs and then exposed to either AMF or a WB with targeted steady-state temperatures of 45, 50, and 55 °C for 5, 15, and 30 min. In multiple treatment cases, AMF exposure significantly increased virus inactivation in comparison to WB exposure. This high level of inactivation following AMF exposure is hypothesized to most likely be due to the physical effects resulted from the rotation of MNPs and the higher surface temperature of the MNPs. This is the first demonstration of enhanced inactivation of pseudoparticles with SARS-CoV-2 S protein, and this study shows the potential for MNPs and AMF treatments to effectively inactivate viruses.

METHODS

Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Synthesis.

A one-pot coprecipitation method was used to synthesize the uncoated iron oxide nanoparticles. Briefly, 40 mL of aqueous solution of FeCl3·6H2O and FeCl2·6H2O in a 2:1 M ratio (2.2 and 0.8 g, respectively) was prepared in a sealed three-neck flask. The mixture was heated to 83.5 °C while being vigorously stirred (300 rpm) under an inert environment (nitrogen flow). Once the temperature reached 83 °C, 4.5 mL of NH4OH was added into the mixture; the temperature increased to 85 °C, and the reaction was performed for 1 h at 85 °C. The particles were then magnetically decanted and washed three times with deionized (DI) water. The nanoparticles were then resuspended in DI water and dialyzed against DI water for 24 h with periodic water changes.9

Nanoparticle Characterization.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was performed to analyze the size distribution and zeta potential of nanoparticles. To mimic the pseudoparticle treatment conditions for the 1.2 mg/mL MNP solution, 9 mg/mL MNPs were dispersed in DI water using ultrasonication for 10 min. Next, the MNPs dispersed in DI water were mixed with a TNE (50 mM TRIS, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) buffer solution containing 10% sucrose in a 40:260 ratio and vortexed for 30 s to make a 1.2 mg/mL MNP solution in buffer. Then, the particle size and zeta potential were measured in triplicate using an Anton Paar Litesizer 500.

The AMF of the Taylor Winfield magnetic induction source and WB heating were performed to observe the temperature profiles of the nanoparticles using a fiber optic temperature sensor (Luxtron FOT Lab kit). MNPs were dispersed in water using ultrasonication for 10 min. Three stock MNP solutions of 12.75, 9, and 6 mg/mL were made. To make the desired concentrations of MNPs (1.7, 1.2, 0.8 mg/mL), 40 μL MNPs were taken from respective stock MNP solutions and mixed with 260 μL of a TNE (50 mM TRIS, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) buffer solution with 10% sucrose in a 2 mL cryogenic vial. The cryogenic vial was placed in a 15 mL centrifuge tube that was placed in the WB or in the center of the AMF induction coil.

The solution in AMF was heated under the magnetic field of 44.43 kA/m and 292 kHz, and the SAR values were calculated using the following equation.

where Cp is the specific heat capacity (0.65 and 4.18 J/g·K for iron oxide and the buffer (buffer’s heat capacity was assumed to be equivalent to water), respectively), mFe and mbuffer are the mass of iron and buffer, respectively, and ΔT/Δt is the initial slope of the heating profile, which is calculated from the 0 and 50 s time points.

Pseudoparticles Production.

HEK 293T cells were cultured in DMEM + 10% FBS. Transfections of 293T cells with wild-type full length SARS-CoV-2 spike protein plasmid took place in 10 cm dishes with 8 μg of plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine 3000 reagents (Life technologies L3000075). For each preparation of pseudovirus, plates were transfected with either VSV G protein or SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Each preparation included a null sample, where no transfection took place. Plates transfected with VSV G protein were incubated for 24 h, while spike transfections were incubated for 48 h. All incubations were performed at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were then transduced with VSVΔG-GFP genome pseudovirus complemented with VSV G protein (VSVΔGG), incubated for 1 h, washed 3× with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and incubated for 24 h. Supernatants were collected, frozen in a methanol bath, and stored at −80 °C. Samples were purified on a 20% sucrose cushion in an ultracentrifuge SW28 rotor for 2 h at 27 000 rpm and 4 °C. Virus was resuspended in 10% sucrose in TNE with shaking at 4 °C overnight. Pseudovirus was pooled, frozen using a methanol bath, and stored at −80 °C. It is important to note that the starting titer of pseudovirus varies per production batch, as every experimental replicate used particles from the same batch with controls in place.

AMF and WB Treatment.

MNPs were dispersed in water using ultrasonication for 10 min (10 s of sonication followed by 5 s of rest until a total of 10 min of sonication). 50 μL of pseudoparticles in a TNE buffer containing 10% sucrose, 210 μL of TNE buffer containing 10% sucrose, and 40 μL of MNPs dispersed in water were mixed and vortexed for 30 s. For each set of experiments, eight identical samples were made with the same concentration of MNPs. For control samples not exposed to MNPs, two additional samples were prepared using 50 μL of pseudoparticles in a TNE buffer containing 10% sucrose and 250 μL of TNE buffer containing 10% sucrose. All the samples were placed in an ice bucket and transported approximately 30 min from the biochemistry lab to the AMF or WB treatment lab. The sample without MNPs (only pseudoparticles + buffer) and treatment was referred to as the untreated pseudoparticle sample in Figures S3 and S4. To control for the potential of AMF alone to have an effect, one sample containing no MNPs (only pseudoparticles + buffer) was exposed to an AMF for 30 min and then placed back in the ice bucket. To examine the effect of MNPs alone on pseudoparticle inactivation, one sample (MNPs + pseudoparticles + buffer) was simply transported in the ice bucket with the other samples without being treated. For each MNP concentration (i.e., 0.8, 1.2, and 1.7 mg/mL), one pair of samples containing MNPs from the ice bucket was exposed simultaneously to the AMF and WB for 30 min and then placed back in the ice bucket. Then, another pair of samples was taken from the ice bucket and similarly exposed to the AMF and WB for 15 min, followed by the same procedure for 5 min. Following that, all samples were returned to the biochemistry laboratory for further analysis using the infectivity assay. In this way, three different MNP concentrations (i.e., 0.8, 1.2, and 1.7 mg/mL) were combined with pseudoparticles and TNE buffer and treated with an AMF and WB, respectively.

To normalize the data, the following formula was used for Figures 4, 5, and 6

For each set of single MNPs concentrations, experiments were conducted three times and normalized individually with that set’s (MNPs + pseudoparticles + buffer) sample. The three normalized data for the single MNP concentration were then averaged and used for plotting.

Transduction Assay.

Stable ACE2 expressing HEK 293T cells were seeded in 24-well plates and transduced the following day with pseudoparticles. Serial 10-fold dilutions were performed in a fresh 24-well plate, starting with 5 μL of pseudoparticles in DMEM + 10% FBS, and 300 μL per well was transferred to an aspirated well of stable ACE2 293T cells. Transductions were incubated for 24 h before being visualized on the Axiovert 200M 5× objective. Transduced, GFP expressing cells were counted, and the pseudoviral titer was calculated using the dilution factor. Samples were transduced in duplicate. A control sample was used for each assay, which did not receive either WB or AMF treatment but underwent travel conditions identical to the variable samples. All assays were performed in triplicate and analyzed as such. Statistical significance was calculated using a t test with unequal variance with a multiple comparison between WB and AMF at each time point (sample size, N = 3).

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM).

A pseudoparticle suspension in TNE with 10% sucrose was fixed at room temperature for 24 h in 2% glutaraldehyde in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube by mixing 8 μL of 2.5% glutaraldehyde in water and 2 μL of a pseudoparticle suspension. After fixing, the 10 μL volume was placed on a tweezer-held gold TEM grid with lacey carbon film (Ted Pella 01824-G) for 1 min with excess solution removed by blotting on a Kimwipe, followed by 15 s of washing with phosphate buffered saline (pH 4.5) and staining three times in freshly prepared aqueous 2% uranyl acetate. Both washing and staining were performed by placing ~15 μL drops of the appropriate solution on a piece of parafilm and then agitating the TEM grid upside down (sample side on top of the wash or stain drop) for 15 s at each step with excess solution removed by blotting against a Kimwipe after the third and final staining step. The stained grid was then air-dried for 1 min before being placed back in the grid storage box, which was stored in a plastic bag with desiccant to fully dry before imaging was performed using a FEI Talos F200X in the UK Electron Microscopy Center.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported was primarily supported by NIEHS/NIH grant P42ES007380. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH. Partial support was also provided by the NSF-RAPID grant (Award Number: 2030217).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsabm.2c00522.

Additional characterizations (Figures S1–S4 and Table S1) (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acsabm.2c00522

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Pranto Paul, Department of Chemical & Materials Engineering, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0046, United States.

Kearstin L. Edmonds, Molecular & Cellular Biochemistry, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40536, United States

Kevin C. Baldridge, Department of Chemical & Materials Engineering, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0046, United States.

Dibakar Bhattacharyya, Department of Chemical & Materials Engineering, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0046, United States.

Thomas Dziubla, Department of Chemical & Materials Engineering, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0046, United States.

Rebecca Ellis Dutch, Molecular & Cellular Biochemistry, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40536, United States.

J. Zach Hilt, Department of Chemical & Materials Engineering, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0046, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Widera M; Westhaus S; Rabenau HF; Hoehl S; Bojkova D; Cinatl J Jr.; Ciesek S Evaluation of stability and inactivation methods of SARS-CoV-2 in context of laboratory settings. Medical microbiology and immunology 2021, 210 (4), 235–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Wang M-Y; Zhao R; Gao L-J; Gao X-F; Wang D-P; Cao J-M SARS-CoV-2: Structure, Biology, and Structure-Based Therapeutics Development. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2020, 10, 587269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Walls AC; Park YJ; Tortorici MA; Wall A; McGuire AT; Veesler D Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181 (2), 281–292.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wrapp D; Wang N; Corbett KS; Goldsmith JA; Hsieh CL; Abiona O; Graham BS; McLellan JS Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 2020, 367 (6483), 1260–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Letko M; Marzi A; Munster V Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nature Microbiology 2020, 5 (4), 562–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Patterson EI; Prince T; Anderson ER; Casas-Sanchez A; Smith SL; Cansado-Utrilla C; Solomon T; Griffiths MJ; Acosta-Serrano Á; Turtle L; Hughes GL Methods of Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 for Downstream Biological Assays. J. Infect Dis 2020, 222 (9), 1462–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Yu L; Peel GK; Cheema FH; Lawrence WS; Bukreyeva N; Jinks CW; Peel JE; Peterson JW; Paessler S; Hourani M; Ren Z Catching and killing of airborne SARS-CoV-2 to control spread of COVID-19 by a heated air disinfection system. Mater. Today Phys 2020, 15, 100249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Batéjat C; Grassin Q; Manuguerra J-C; Leclercq I Heat inactivation of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Journal of biosafety and biosecurity 2021, 3 (1), 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Guo L; Yao Z; Yang L; Zhang H; Qi Y; Gou L; Xi W; Liu D; Zhang L; Cheng Y; Wang X; Rong M; Chen H; Kong MG Plasma-activated water: An alternative disinfectant for S protein inactivation to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection. Chem. Eng. J 2021, 421, 127742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Mai T; Hilt JZ Magnetic nanoparticles: reactive oxygen species generation and potential therapeutic applications. J. Nanopart. Res 2017, 19 (7), 253. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Wydra RJ; Oliver CE; Anderson KW; Dziubla TD; Hilt JZ Accelerated generation of free radicals by iron oxide nanoparticles in the presence of an alternating magnetic field. RSC Adv. 2015, 5 (24), 18888–18893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Mai T; Hilt JZ Functionalization of iron oxide nanoparticles with small molecules and the impact on reactive oxygen species generation for potential cancer therapy. Colloids Surf., A 2019, 576, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Rosensweig RE Heating magnetic fluid with alternating magnetic field. J. Magn. Magn. Mater 2002, 252, 370–374. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Polo-Corrales L; Rinaldi C Monitoring iron oxide nanoparticle surface temperature in an alternating magnetic field using thermoresponsive fluorescent polymers. J. Appl. Phys 2012, 111, 07B334. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Vlasova KY; Piroyan A; Le-Deygen IM; Vishwasrao HM; Ramsey JD; Klyachko NL; Golovin YI; Rudakovskaya PG; Kireev II; Kabanov AV; Sokolsky-Papkov M Magnetic liposome design for drug release systems responsive to super-low frequency alternating current magnetic field (AC MF). J. Colloid Interface Sci 2019, 552, 689–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Qiu D; An X Controllable release from magnetoliposomes by magnetic stimulation and thermal stimulation. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 104, 326–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Lu Y-J; Chuang E-Y; Cheng Y-H; Anilkumar TS; Chen H-A; Chen J-P Thermosensitive magnetic liposomes for alternating magnetic field-inducible drug delivery in dual targeted brain tumor chemotherapy. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 373, 720–733. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Tanaka K; Ito A; Kobayashi T; Kawamura T; Shimada S; Matsumoto K; Saida T; Honda H Intratumoral injection of immature dendritic cells enhances antitumor effect of hyperthermia using magnetic nanoparticles. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 116 (4), 624–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Gupta R; Sharma D Manganese-Doped Magnetic Nano-clusters for Hyperthermia and Photothermal Glioblastoma Therapy. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2020, 3 (2), 2026–2037. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kutuk O; Aytan N; Karakas B; Kurt AG; Acikbas U; Temel SG; Basaga H Biphasic ROS production, p53 and BIK dictate the mode of cell death in response to DNA damage in colon cancer cells. PLoS One 2017, 12 (8), No. e0182809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kantidze OL; Velichko AK; Luzhin AV; Razin SV Heat Stress-Induced DNA Damage. Acta Naturae 2016, 8 (2), 75–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Whitt MA Generation of VSV pseudotypes using recombinant ΔG-VSV for studies on virus entry, identification of entry inhibitors, and immune responses to vaccines. J. Virol Methods 2010, 169 (2), 365–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Johnson MC; Lyddon TD; Suarez R; Salcedo B; LePique M; Graham M; Ricana C; Robinson C; Ritter DG Optimized Pseudotyping Conditions for the SARS-COV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. J. Virol 2020, 94 (21), e01062–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Hoffmann M; Kleine-Weber H; Schroeder S; Krüger N; Herrler T; Erichsen S; Schiergens TS; Herrler G; Wu NH; Nitsche A; Müller MA; Drosten C; Pöhlmann S SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181 (2), 271–280.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Schmidt F; Weisblum Y; Muecksch F; Hoffmann H-H; Michailidis E; Lorenzi JCC; Mendoza P; Rutkowska M; Bednarski E; Gaebler C; Agudelo M; Cho A; Wang Z; Gazumyan A; Cipolla M; Caskey M; Robbiani DF; Nussenzweig MC; Rice CM; Hatziioannou T; Bieniasz PD Measuring SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody activity using pseudo-typed and chimeric viruses. bioRxiv 2020, 2020.06.08.140871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Baldridge KC; Edmonds K; Dziubla T; Hilt JZ; Dutch RE; Bhattacharyya D Demonstration of Hollow Fiber Membrane-Based Enclosed Space Air Remediation for Capture of an Aerosolized Synthetic SARS-CoV-2 Mimic and Pseudovirus Particles. ACS ES&T Engineering 2022, 2 (2), 251–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Abe H; Ikebuchi K; Hirayama J; Fujihara M; Takeoka S; Sakai H; Tsuchida E; Ikeda H VIRUS INACTIVATION IN HEMOGLOBIN SOLUTION BY HEAT TREATMENT. Artificial Cells, Blood Substitutes, and Biotechnology 2001, 29 (5), 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Wang Y; Wu X; Wang Y; Li B; Zhou H; Yuan G; Fu Y; Luo Y Low stability of nucleocapsid protein in SARS virus. Biochemistry 2004, 43 (34), 11103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lee Y-N; Chen L-K; Ma H-C; Yang H-H; Li H-P; Lo S-Y Thermal aggregation of SARS-CoV membrane protein. Journal of virological methods 2005, 129 (2), 152–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.