Abstract

In this contribution, five Ni(II) complexes have been synthesized from sulfonamide-based Schiff bases (SB1–SB5) that comprise bromo or iodo substituents in the salicylidene moiety. The chemical structures of these compounds were extensively elucidated by different analytical and physicochemical studies. All ligands act as bidentate chelators with ON binding mode yielding octahedral, square planar, or tetrahedral geometries. The phenolic OH at δ 12.80 ppm in the free Schiff base SB2 vanishes in the 1H NMRspectrum of diamagnetic complex [Ni(SB2–H)2] favoring the OH deprotonation prior to the chelation with Ni(II) ion. The appearance of twin molecular ion peaks ([M − 1]+ and [M + 1]+) is due to the presence of bromine isotopes (79Br and 81Br) in the mass spectra of most cases. Also, the thermal decomposition stages of all complexes confirmed their high thermal stability and ended with the formation of NiO residue of mass 6.42% to 14.18%. Besides, antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity of the ligands and some selected complexes were evaluated. Among the ligands, SB4 showed superior antimicrobial efficacy with MIC values of 0.46, 7.54, and 0.95 µM against B. subtilis, E. coli, and A. fumigatus strains, respectively. The consortium of different substituents as two bromine atoms either at positions 3 and/or 5 on the phenyl ring and a thiazole ring is one of the reasons behind the recorded optimal activity. Moreover, there is a good correlation between the cytotoxicity screening (IC50) and molecular docking simulation outcomes that predicted a strong binding of SB2 (16.0 μM), SB4 (18.8 μM), and SB5 (6.32 μM) to the breast cancer protein (3s7s). Additionally, [Ni(SB4–H)2] (4.33 µM) has nearly fourfold potency in comparison with cisplatin (19.0 μM) against breast carcinoma cells (MCF-7) and is highly recommended as a promising, potent, as well as low-cost non-platinum antiproliferative agent after further drug authorization processes.

Subject terms: Cancer, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Chemistry

Introduction

Conjugated heterocyclic systems containing nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur atoms in their structures have long been known for their diverse biological actions1–3. The activity of these heterocyclic compounds against wide varieties of pathogens increases especially when introduced in the form of metal complexes4,5. Transition metal complexes of Schiff bases derived from sulfa drugs are among systems that have been reported extensively for their pronounced medicinal performance5–8. Most of the sulfa drugs exhibit a bacteriostatic effect by preventing cell division through the inhibition of the dihydropteroate synthase enzyme that is essential in the proteins and nucleic acids formation in bacterial cells9,10. Crucially, coupling of Schiff bases-sulfonamide moieties with halogen substituents could enhance the therapeutic efficiency including antimicrobial, antitumor, and antiviral activities11–14. Halogens, such as bromine and iodine have a prominent ability to interact with electron donor atoms due to their electron-withdrawing property that generates σ-hole, positive electrostatic potential, along the halogen bond 15. They can effectively form stable donor–acceptor bonds with the surrounding molecules such as the electron-rich sites of the adjacent amino acids. This enhances the binding affinity to certain proteins16.

Clearly, the mutual existence of different units of hetero atoms, halogens, and metal ions in one combined structure is particularly important because of the role played by each entity. Such combined structure creates unequal electron density distribution with different electrophilic and nucleophilic regions on the surface of the molecules which increases the chance of chelation with proteins and provides a wide range of chemical and biological practices. Although there are massive investigations on antipathogenic agents with different functional groups and structures to find more effective and less toxic drugs, the rapid evolution of research is still challenging the need to overcome the quick development of drug-resistant microbes. Besides, Schiff bases have been recognized as catalysts17, corrosion inhibitors18, and efficient polymer stabilizers19. The diversity of the bioinorganic applications of Schiff bases is stemmed from the fact that this class of compounds possesses a high complexing ability through the azomethine group and neighboring donor atoms in a polydentate fashion20–23. In consideration of the mentioned observations, the current research is aiming to examine the microbial and tumor inhibition activities of newly synthesized nickel (II) complexes derived from mono- and di-halogenated Schiff bases bearing the bioactive benzenesulfonamide group. In addition, the structural variations of the investigated ligands and complexes such as different pendant substituents or geometric chelation types are correlated theoretically and experimentally as important parameters accountable for their chemical and biological behaviors.

Experimental

Chemicals, instruments, and computations

Nickel (II) nitrate hexahydrate salt and 5-bromosalicylaldehyde were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich with high purity (≥ 98%). 3,5-Dihalosubstituted salicylaldehyde (X2C6H2(o-OH)CHO), where X = Br or I, were prepared following the known methods in the literature24,25. Infrared spectra of the synthesized ligands and their complexes were recorded by FT-IR tensor 37 spectrophotometer in the range 400–4000 cm−1. Microanalysis (CHNS) was performed at the microanalytical laboratory, Cairo University. The metal content in each sample was doubly determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometer and by complexometric back titration using standard EDTA solution and Eriochrome black T indicator26. Also, the absorption in the UV–Vis region was conducted by the SHIMADZU UV-1800 scanning spectrophotometer in the wavelength range 200–800 nm using dimethylformamide as a solvent. The mass-to-charge ratio of the molecular ions was measured by SHIMADZU mass spectrometer (QP2010 Plus) at an electron energy of 70 eV at Cairo University and by Thermo Scientific GCMS model ISQ et al.-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt. Thermal decomposition of the complexes was investigated by the thermogravimetric (TGA) as well as the differential thermogravimetric (DTA) techniques using LINSEIS STA PT1000 analyzer under N2 atmosphere as inert gas and a temperature rate of 10 °C/min. The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were studied for the ligands and the diamagnetic complex in a deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide solvent on a 500 MHz spectrometer.

Geometry optimization and structural energy calculations of some selected compounds were computed by density functional theory (DFT) using GAUSSIAN09 software, Version 9.5, and GAUSSVIEW 6.0.1627,28. Hybrid exchange–correlation function (B3LYP) with the basis set Lanl2dz was chosen for the investigated systems. This level of theory (DFT/B3LYP) has been approved as an effective approach to calculate the electronic properties of organic systems containing electronegative atoms, analogous to the present work29,30. True energy minima of the optimized structures were proved by the absence of imaginary vibrational frequencies in the GAUSSIAN output files. A molecular docking study was conducted by the Molecular Operating Environmental module (MOE 2015.10). The 3D structure of the selected protein 3s7s was adopted from the protein data bank. As docking initial steps, the protein structure was set up by removing water molecules and adding hydrogen atoms. Also, a site finder was used for the ligand-binding site prediction. Evaluation of the best binding pose between the investigated ligands and the receptor protein was based on the H-bond length and the scoring energy of the simulated docked complex.

Antimicrobial and cytotoxicity assessment

The in vitro biological activity of the synthesized halogenated Schiff bases and some of their complexes was investigated employing Kirby–Bauer agar diffusion assay against different pathogenic species including Gram-negative bacteria (P. vulgaris & E. coli), Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus & B. subtilis), and fungi (A. fumigatus & C. albicans) as depicted in the literature31. All inhibition zone diameter values in mm were assessed in triplicates for the tested samples. Also, MIC (minimal inhibitory concentration in µg/ml) was determined by the serial dilution method as reported32,33. The activity of the tested compounds was compared to ketoconazole, gentamycin, and ampicillin as reference controls for antifungal and antibacterial potencies.

Besides, the cytotoxicity of some selected synthesized ligands and complexes against human breast carcinoma cell line (MCF-7) and normal human oral epithelial cell (OEC) was evaluated by colorimetric viability assay as reported34. All human cancer cell lines were obtained from the VACSERA Tissue Culture Unit, Egypt and the OEC cells (PCS-200-014) were from American Culture Type Collection. Cisplatin was used as a standard reference under the same assay specifications. The biological measurements were carried out et al.-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt.

Synthesis of Schiff bases (SB1–SB5)

Mono- or dihalosubstituted salicylaldehyde (10 mmol) was dissolved in ethanol and then added to equimolar of a primary amine solution, sulfanilamide (10 mmol, 1.7220 g) or sulfathiazole (10 mmol, 2.5552 g). A few drops of acetic acid were added as a catalyst. The reaction mixture was refluxed with continuous stirring for 5–8 h in a water bath. The colored Schiff bases were filtered off, washed by ethanol and ether then dried in a calcium chloride desiccator. Recrystallization of the resulted solids was performed in hot ethanol–water solvents (1:1) for complete purification. The synthesized sulfonamide-Schiff bases are presented in Fig. 1. The IUPAC names of the synthesized ligands are 4-((5-Bromo-2-hydroxybenzylidene)amino)-benzenesulfonamide (SB1), 4-((5-Bromo-2-hydroxybenzylidene)amino)-N-(1,3-thiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamide (SB2), 4-((3,5-Dibromo-2-hydroxybenzylidene)amino)-benzenesulfonamide (SB3), 4-((3,5-Dibromo-2-hydroxybenzylidene)amino)-N-(1,3-thiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamide (SB4), and 4-((3,5-Diiodo-2-hydroxybenzylidene)amino)-N-(1,3-thiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamide (SB5).

Figure 1.

Systematic path for the synthesis of sulfonamide-Schiff base ligands (SB1–SB5).

Synthesis of nickel (II) complexes

Ni (II) complexes were prepared by mixing an aqueous solution of Ni(NO3)2.6H2O (1.4533 g, 5 mmol) with hot ethanolic solution of Schiff bases (SB1–SB5) (10 mmol) under stirring and reflux at 70 °C for 2 h. The solution was turned to a slightly basic medium (pH ≈ 8) by adding a few drops of ammonia (1:1). The yielded complexes were filtered, washed with a small amount of ethanol and ether, then kept in desiccators for drying. Elemental analysis and some physical properties of the synthesized ligands and their complexes are specified in Table 1.

Table 1.

Elemental analysis and physical properties of the synthesized nickel (II) complexes. All complexes have m.p. > 300 °C.

| Compound | Formula Color, m.p. °C | % Calculated/(Found) | μeff B.M | Geometry | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | C | H | N | S | ||||

| SB1 |

C13H11BrN2O3S Orange, 184–186 |

– |

43.96 (44.12) |

3.12 (3.32) |

7.89 (7.96) |

9.03 (8.82) |

– | – |

| [Ni(SB1–H)2(SB1)]·2H2O |

C39H35Br3N6O11S3Ni Yellow |

5.07 (4.89) |

40.44 (40.62) |

3.05 (3.15) |

7.26 (7.43) |

8.30 (8.22) |

3.13 | Oh |

| SB2 |

C16H12BrN3O3S2 Yellow, 162–164 |

– |

43.84 (43.97) |

2.76 (2.89) |

9.59 (9.73) |

14.63 (14.32) |

– | – |

| [Ni( SB2–H)2]·3H2O |

C32H28Br2N6O9S4Ni Greenish yellow |

5.94 (5.84) |

38.93 (39.05) |

2.86 (3.01) |

8.51 (8.82) |

12.99 (12.81) |

dia | SP |

| SB3 |

C13H10Br2N2O3S Red, 242–244 |

– |

35.97 (36.12) |

2.32 (2.35) |

6.45 (6.43) |

7.39 (7.22) |

– | – |

| [Ni(SB3–H)(OH)(H2O)] |

C13H12Br2N2O5SNi Yellowish green |

11.14 (11.02) |

29.64 (29.71) |

2.30 (2.62) |

5.32 (5.59) |

6.09 (5.98) |

0.50 | SP |

| SB4 |

C16H11Br2N3O3S2 Buff, 141–142 |

– |

37.16 (37.42) |

2.14 (2.35) |

8.12 (8.41) |

12.40 (12.22) |

– | – |

| [Ni( SB4–H)2]·4H2O |

C32H28Br4N6O10S4Ni Bright yellow |

5.05 (4.88) |

33.04 (33.29) |

2.43 (2.56) |

7.23 (7.42) |

11.03 (10.92) |

2.91 | Td |

| SB5 |

C16H11I2N3O3S2 Brown, 243–245 |

– |

31.44 (31.62) |

1.81 (2.15) |

6.87 (7.10) |

10.49 (10.22) |

– | – |

| [Ni(SB5–H)(OH)(H2O)] |

C16H13I2N3O5S2Ni Yellowish green |

8.34 (8.55) |

27.30 (27.47) |

1.86 (2.06) |

5.97 (6.22) |

9.11 (9.04) |

2.15 | SP ↔ Td |

Results and discussion

FT-IR, NMR, and MS spectroscopy

Some fundamental FT-IR bands of the free ligands (SB1–SB5) and the synthesized Ni(II) complexes are compared in their position and shape as presented in Table S1 and illustrated in Figs. 1 and S1–S6. It is discernible from the spectral data that the assigned bands for the νCH=N and νC–O in the free ligands at 1559–1584 cm−1 and 1232–1279 cm−1, respectively, both suffer a lowering in intensity and wavenumbers supporting the bidentate coordination mode towards the Ni(II) through the phenolic oxygen and the nitrogen atom of the azomethine group (Fig. 2)13.

Figure 2.

Structure of [Ni(SB4–H)2]·4H2O complex.

In the case of SB1 and SB3 ligands derived from sulfonamide moiety, typical adjacent bands of asymmetric and symmetric νNH2 were observed at 3314–3359 cm−1 and 3232–3270 cm−1, successively. Also, two stretching bands of the SO2 group of these ligands were detected in 1318–1336 cm−1 and 1138–1157 cm−1 for the asymmetric and symmetric vibrational modes, respectively. No change in the band’s position of NH2 or SO2 was discerned upon complexation which excludes these groups from being involved in the binding mode with the central metal ion. As for the ligands derived from sulfathiazole (SB2, SB4, and SB5), the inference of the exact change in position or the disappearance of the νO–H band of the phenolic group upon complexation was not straightforward due to overlapping with the νN–H band in the spectral region (3053–3457 cm−1) as depicted in Table S1. However, some remarkable changes in this spectral region were spotted. For example, the broad feature in this region could be attributed to intramolecular hydrogen-bonding (O–H–N) with the nearby azomethine group in ligands or of (O–H–O) type with water molecules inside or outside the coordination sphere35. In addition, the new broad bands assigned for νO–H at ~ 3440 cm−1 in the IR spectra of [Ni(SB3–H)(OH)(H2O)] and [Ni(SB5–H)(OH)(H2O)] complexes, Fig. 3, could endorse the existence of covalently bonded OH group in their inner spheres from the alkaline medium as previously reported36. Furthermore, the isolated complexes showed extra vibrational bands in the ranges 506–566 cm−1 and 458–506 cm−1, where these developed bands were assigned to the Ni–O and Ni–N stretching modes, respectively, indicating the proposed chelation mode37.

Figure 3.

FT-IR of (a) SB3, (b) [Ni(SB3–H)(OH)(H2O)], (c) SB5, (d) [Ni(SB5–H)(OH)(H2O)].

1H NMR and 13C NMR are additional techniques that support plentifully the structure elucidation of the synthesized compounds. The NMR data are collected in Figs. 4 and S7–S15 in the supplementary information with detailed assignments on each designated structure. Regarding the fundamental 1H NMR peaks, the phenolic OH at C(2) in the free Schiff base ligands (SB1–SB5) were located within the range of δ 12.53–14.26 ppm. This peak at δ 12.80 ppm in SB2 vanishes in the diamagnetic complex [Ni(SB2–H)2] (Fig. 4) favoring the OH deprotonation prior to the chelation with Ni(II) ion. The presence of halogen atoms (Br or Cl) at positions C(3) and/or C(5) (Fig. 1) with an electron-withdrawing feature may facilitate the proton elimination at C(2). However, the NH peak of the sulfathiazole moiety in SB2, SB4, and SB5 which appeared at δ 12.52–12.84 ppm exhibits no change upon complexation. Also, the two protons of the sulfanilamide NH2 group of SB1 and SB3 were observed in the aromatic region at δ 7.42 and 7.38 ppm, respectively. Moreover, Schiff base formation was further supported by the spotted azomethine proton (C7(H) = N) as a singlet peak in the range δ 8.86–9.01 ppm. Pertain to 13C NMR, the compound SB2, C16H12N3O3S2Br, showed 14 different carbon peaks of which two possess integration corresponding to 2 identical carbons at 122.1 and 127.2 ppm for [C(9), C(13] and [C(10), C(12)], respectively. Further, the position of halogen-bearing carbons [C(3) and C(5)] is clearly downfield shifted ongoing from SB4 (Fig. S13) to SB5 (Fig. S15) owing to the higher deshielding effect by Br atoms [C(3) 111.2; C(5) 112.4 ppm] relative to that induced by I atoms [C(3) 88.9; C(5) 82.1 ppm].

Figure 4.

1H NMR spectra of (a) SB2, (b) [Ni(SB2–H)2] complex in DMSO-d6.

The structures of some selected ligands and complexes were further elucidated by the mass spectrometric technique. The mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) is displayed in Figs. 5, 6 and S16–S18, where the recorded molecular ion peaks are in accordance with the determined formula mass from the microanalytical technique. The m/z peaks at 987.59, 526.37, and 703.47 are assigned to the molecular weight of [Ni(SB2–H)2]·3H2O, [Ni(SB3–H)(OH)(H2O)], and [Ni(SB5–H)(OH)(H2O)] complexes, respectively. Besides, the peak with the highest intensity (100% abundance) that appeared at m/z 685.01 (Fig. S18) could be attributed to the corresponding fragment [Ni(SB5–H)(OH)]+ with one water molecule less than its precursor. Moreover, the peak corresponding to the Ni isotope appeared clearly at m/z of ~ 59 in the mass spectra of the studied complexes (Figs. 6, S17, and S18). Similarly, the molecular ion peaks are well in agreement with the molecular weight of the synthesized ligands (SB1 and SB2). Clearly, two molecular ion peaks of nearly equal intensity appeared at m/z of 354 and 356 for SB1 and m/z of 437 and 439 for SB2 respectively (Figs. S16 and 3). These twin molecular ion peaks represent [M − 1]+ and [M + 1]+ and appear due to bromine isotopes (79Br and 81Br)38. In addition, the base peak (100% intensity) of SB1 at m/z ~ 80 corresponds to the [SO2NH2] fragment of the sulfonamide group39. Also, the twin peaks that appeared at m/z 274 and 276 in the mass spectra of SB1 and SB2 is manifestly defining the cation [C13H9NOBr]+ (Fig. 7) which results from the elimination of the sulfonamide or sulfathiazole fragments in that order. The structural mass fragmentation pathways of SB2 ligand and [Ni(SB3–H)(OH)(H2O)] complex are represented in Figs. 7 and 8.

Figure 5.

Mass spectrum of SB2.

Figure 6.

MS of [Ni(SB3–H)(OH)(H2O)] complex.

Figure 7.

Proposed mass fragmentation SB2 ligand.

Figure 8.

Proposed mass fragmentation of [Ni(SB3–H)(OH)(H2O)] complex.

Electronic spectra, magnetic, and conductivity measurements

UV–Vis absorption spectra of the synthesized compounds were measured in the range 200–700 nm in DMF solvent. Two distinct absorption bands were observed within the ranges 265–292 and 326–367 nm attributed to the π → π* and n → π* transitions, respectively (Fig. 9). These bands are owing to the presence of OH, azomethine, and sulfonyl groups in the vicinity of the conjugated system. Similarly, these bands have appeared in the spectra of the Ni(II) complexes in the same wavelength ranges whereas obvious broadband in the region 415–454 nm is ascribed to the charge transfer of the type LMCT. This broad CT band in the absorbance spectra of the complexes completely obscured the expected d-d transitions in this region40.

Figure 9.

UV–Vis absorption band of SB3 and SB5 ligands and their complexes.

The synthesized complexes possess a neutral non-electrolytic feature. This was verified by the low measured molar conductance of Λm < 4.5 Ω–1 mol−1 cm2 for a concentration of 10–3 M in DMF39. Additionally, different geometries of Ni (II) complexes were confirmed by the effective magnetic moments (μeff) at room temperature (Table 1). Commonly, the diamagnetic behavior coincides with square planar geometry as in the case of [Ni(SB2–H)2]·3H2O complex8. Also, [Ni(SB1–H)2(SB1)]·2H2O that exhibited magnetic moments of 3.13 was assigned to octahedral geometry and consistent with the 1:3 (M:L) stoichiometry41. However, the relatively low spin values within the range 0.5–2.91 B.M of the Ni(II) complexes derived from SB3, SB4, and SB5 may be caused either by spin–spin interaction or tetrahedral ↔ square planar configurational equilibrium42. The tetrahedral percentage can be calculated by the following mathematical formula:

where Nt is the tetrahedral percentage in the solid-state of the 4-coordinate complex and μobs is the measured magnetic moment at 296 K43. The calculated Nt for [Ni(SB3–H)(OH)(H2O)] was found to be 2.3% which indicates the dominance of the square planar configuration. Nevertheless, Nt values for [Ni(SB4–H)2]·4H2O and [Ni(SB5–H)(OH)(H2O)] were 77.8 and 42.4%, respectively.

Thermal analysis

The thermal stability of the synthesized nickel complexes was studied by TGA and DTA approaches in the temperature range up to 700 °C in a nitrogen atmosphere, Table 2 and Figs. 10 & S19. The main thermal decomposition stage of breaking the metal–ligand bonds starts in the temperature range 299.1–423.9 °C implying their thermal stability. This stage is preceded by the removal of small molecules such as hydrated H2O, coordinated H2O, NH3, or SO2. As an example, the thermal breakdown of [Ni(SB4–H)2]·4H2O complex proceeds in three successive steps. The first step with a percentage mass loss of 6.32% (calc. 6.20%) was assigned to the removal of four outer sphere water molecules. This step was followed by the elimination of inner sphere small molecules (2 NH3 and 2 SO2) which started at the temperature of 220.4 °C. The decomposition of the bulk of two ligand molecules (C32H14N4OS2Br4) begins at 347.0 °C with a DTA peak maximum (Tmax) at 531.1 °C. The elevated Tmax for this step is an indication of the complex thermal stability44. For all complexes, the thermal decomposition ended with the formation of NiO residue with a mass percentage in the range of 6.42% to 14.18%. Noteworthy, the combination of the decomposed fragments is in accord with the proposed structure of a given complex as deduced from spectroscopic and analytical data. However, the common overlap in the steps of the thermal decomposition could explain the slight variation between the calculated and found masses of the yielded thermal fragments.

Table 2.

Thermogravimetric decomposition steps of Ni(II) complexes derived from SB1–SB5.

| Complex (M:L) | Tmax °C | Temp. Range (oC) | Wt. loss / Residue % | Assignment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Found | Calc | ||||

|

[Ni(SB1)2(SB1–H)]·2H2O (1:3) |

132.6 | 31.0–230.0 | 5.86 | 6.05 | –2H2O, –2NH3 |

| 313.9 | 230.0–377.4 | 16.43 | 16.59 | –3SO2 | |

| 436.8 | 377.5–695.8 | 71.28 | 70.91 | –C39H25O2N4Br3 | |

| Residue | 6.43 | 6.45 | NiO | ||

|

[Ni(SB2)2]·3H2O (1:2) |

185.4 | 34.9–265.4 | 9.24 | 8.92 | –3H2O, –2NH3 |

| 305.4 | 265.4–389.2 | 12.71 | 12.98 | –2SO2 | |

| 446.2 | 389.2–697.8 | 70.58 | 70.53 | –C32H16N4OS2Br2 | |

| Residue | 7.47 | 7.56 | NiO | ||

|

[Ni(SB3–H)(OH)(H2O)] (1:1) |

143.6 | 35.3–201.3 | 6.79 | 6.84 | –2H2O |

| 374.5 | 304.6–423.9 | 15.52 | 15.39 | –NH3, –SO2 | |

| 517.5 | 423.9–698.6 | 63.78 | 63.59 | –C13H5NBr2 | |

| Residue | 13.91 | 14.18 | NiO | ||

|

[Ni(SB4–H)2]·4H2O (1:2) |

151.9 | 28.3–220.4 | 6.32 | 6.20 | –4H2O |

| 320.1 | 220.4–347.0 | 13.96 | 13.94 | –2NH3, –2SO2 | |

| 531.1 | 347.0–698.3 | 73.32 | 73.44 | –C32H14N4OS2Br4 | |

| Residue | 6.40 | 6.42 | NiO | ||

|

[Ni(SB5–H)(OH)(H2O)] (1:1) |

96.6 | 39.7–160.3 | 5.04 | 5.12 | –2H2O |

| 236.4 | 160.3–299.1 | 11.36 | 11.52 | –NH3, –SO2 | |

| 327.2 | 299.1–698.6 | 73.20 | 72.75 | –C16H6N2SI2 | |

| Residue | 10.40 | 10.61 | NiO |

Figure 10.

TGA of the Ni(II)-Schiff base complexes under N2 atmosphere.

Molecular modeling study

Structural optimization and reactivity descriptors

Molecular parameters of all synthesized ligands and Ni(II) complex of SB5 including frontier eigenvalues, dipole moments, bond lengths, and angles were calculated using DFT with B3LYP function and Lanl2dz basis set (Table 3 and Figs. 11, 12 & S20–S25). The chemical reactivity of the synthesized Schiff bases was predicted from the energy difference between the low unoccupied (LUMO) and the high occupied molecular orbitals (HOMO) of the corresponding ligand, E (Fig. 13)8. Noticeably, there is a good correlation between the structure of synthesized ligands and their reactivity. For example, the sulfathiazole Schiff bases, SB2, and SB4 showed nearly similar E values within the range 3.466–3.487 eV. Also, the sulfonamide Schiff bases, SB1 and SB3 exhibited analogous E of 3.553–3.611 eV which implies parallel reactivity of these Schiff bases and indicates the existence of structural-activity relation among the ligands. Based on the optimization parameters, the halogen substituents induce extra stability of the LUMO levels45. This can be predicted by the higher negative total energy, ET, of the di-halogenated ligands (SB3, SB4, and SB5) compared to the mono-halogenated ligands (SB1 and SB2) (Table 3). Moreover, the iodide substituents gave more induced LUMO level stability than the bromide substituents due to the relatively large size of iodide and hence increases the electrophilic character45. Furthermore, the high negative total energy of the complex [Ni(SB5–H)(OH)(H2O)], ET = –1370 Hartree, indicates the great stability of the isolated complex compared to its free ligand46. Besides, the distortion of the standard square planar geometry of the complex Ni(II)–SB5 (1:1) was estimated from the calculated bond angles around the Ni(II) core which are consistent with the determined tetrahedral percentage (Nt = 42.4%) from the experimental magnetism value. The estimated angles N(12)–Ni(34)–O(9), O(9)–Ni(34)–O(36), O(36)–Ni(34)–O(35), and O(35)–Ni(34)–N(12) of Ni(II)–SB5 complex were 95.38°, 87.47°, 78.36°, and 98.97°, respectively representing a mixture of square planar and tetrahedral geometries around the central Ni (II) ion (Table S2 and Fig. 14). Additionally, it was observed that the bonds between the atoms incorporated in the coordination sphere (C(4)–O(9) and C(10)=N(12)) showed longer lengths in the complex than in the free ligand (Table S2)47. However, no change in the bond lengths was noted in the sulfonamide or sulfathiazole parts after the complex formation excluding them from any expected coordination. The magnitude of the calculated dipole moment (D) gives a good indication of the capability of the compound to penetrate the biological cell membrane. Generally, the lower the dipole moment, the higher the penetration strength across the phospholipid bilayer48. In addition, based on the other calculated molecular descriptors; softness (S), hardness (η), electrophilicity (ω), and electronegativity (χ), the estimated chemical reactivity of the ligands toward metal ions or any neighboring biological receptors is in the order: SB5 > SB4 > SB2 > SB3 > SB1, where 4 SB5 is proposed to have the highest softness character (S = 0.300 eV−1) and the smallest E, i.e. the highest electron donation ability.

Table 3.

The molecular parameters of Schiff bases and the Ni(II)–SB5 complex calculated by DFT-B3LYP/Lanl2dz method.

| Compound | ET (Hartree) | D (Debye) | EHOMO (eV) | ELUMO (eV) | ΔE (eV) | η (eV) | S (eV–1) | μ (eV) | χ (eV) | ω (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SB1 | –860 | 4.640 | –6.533 | –2.922 | 3.611 | 1.806 | 0.277 | –4.728 | 4.728 | 6.189 |

| SB2 | –1040 | 4.252 | –6.604 | –3.117 | 3.487 | 1.744 | 0.287 | –4.861 | 4.861 | 6.774 |

| SB3 | –873 | 5.255 | –6.657 | –3.104 | 3.553 | 1.777 | 0.281 | –4.881 | 4.881 | 6.703 |

| SB4 | –1052 | 4.396 | –6.722 | –3.256 | 3.466 | 1.733 | 0.289 | –4.989 | 4.989 | 7.181 |

| SB5 | –1049 | 4.452 | –6.557 | –3.220 | 3.337 | 1.669 | 0.300 | –4.889 | 4.889 | 7.161 |

| [Ni(SB5–H)(OH)(H2O)] | –1370 | 3.149 | –6.068 | –3.014 | 3.054 | 1.527 | 0.327 | –4.541 | 4.541 | 6.752 |

Figure 11.

The optimized structure of Schiff base sulfathiazole, 5-(2-hydroxy-3,5-diiodobenzylidene amino)-N-(1,3-thiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamide (SB5) using DFT-B3LYP/ Lanl2dz method by GAUSSIAN 09 software version 9.5 and GAUSSVIEW 6.0.16.

Figure 12.

The optimized structure of [Ni(SB5–H)(OH)(H2O)] complex using DFT-B3LYP Lanl2dz method by GAUSSIAN 09 software version 9.5 and GAUSSVIEW 6.0.16.

Figure 13.

LUMO and HOMO of SB5 and [Ni(SB5–H)(OH)(H2O)] complex, using GAUSSIAN 09 software version 9.5 and GAUSSVIEW 6.0.16.

Figure 14.

Molecular electrostatic potential map of SB5, using GAUSSIAN 09 software version 9.5 and GAUSSVIEW 6.0.16.

Furthermore, the electron density cloud was mapped over the surface of the ligands to evaluate the nucleophilic (high electron density, red) and the electrophilic (low electron density, blue) sites of interactions (Figs. 14 and S25)49. The regions with zero electronic potential are denoted by green. For all ligands, the (SO2) group represents the site with intense electron density, while there is a lack of electron density at the hydrogen terminals. Nevertheless, the N(13) of the azomethine and O(9) of the phenol parts of SB5 (Fig. 14) showed moderate nucleophilicity with Mulliken charges of − 0.587 and − 0.596 a.u. for N(13) and O(9) respectively, and hence can be possible electron donor atoms in the coordination mode as proposed spectroscopically.

Molecular docking

Docking investigation is an essential step preceding the in vitro study of any proposed biologically active compound. This approach elucidates the ligand-receptor site and type of interactions. It also gives an estimation of the distance between the ligand and the receptor inside the interaction grid. The scoring energy of each pose simulated by the docking calculations reflects the degree of inhibition effect of the corresponding ligand. In the present study, the selected protein 3s7s represents the crystal structure of the human placental aromatase enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of estrogen hormone and contributes to estrogen-dependent breast cancer50. All ligands possess an appreciable extent of interactions with the receptor protein based on the scoring energy (S), the number, and the length of H-bonds (Table 4 and Figs. 15 & S26). Favorable interaction was discerned for SB5 with many bonds formed inside the protein binding pocket and high scoring energy of (− 8.6219 kcal/mol). The great number of H-bonds would successfully facilitate its penetration across the cell membrane.

Table 4.

The interaction parameters of the synthesized compounds versus 3s7s protein.

| Compound | Ligand site | Receptor site | Interaction type | Distance (Å) | E (kcal/mol) | S (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SB1 | N 28 | PHE 430 | H-donor | 3.28 | − 0.7 | − 6.6717 |

| N 28 | ARG 435 | H-donor | 3.33 | − 1.2 | ||

| Br 31 | MET 447 | Halogen bonding | 4.31 | − 0.4 | ||

| O 27 | ARG 115 | H-acceptor | 2.81 | − 1.8 | ||

| SB2 | S 31 | MET 303 | H-donor | 3.94 | − 0.2 | − 8.3594 |

| Br 37 | ARG 435 | Halogen bonding | 3.32 | − 0.8 | ||

| O 27 | ALA 307 | H-acceptor | 3.20 | − 0.8 | ||

| SB3 | O 9 | MET 311 | H-donor | 3.17 | − 1.9 | − 7.1499 |

| N 27 | GLU 302 | H-donor | 3.28 | − 1.4 | ||

| N 27 | MET 303 | H-donor | 3.70 | − 3.1 | ||

| Br 30 | PRO 429 | Halogen bonding | 3.04 | − 0.5 | ||

| Br 31 | MET 447 | Halogen bonding | 3.52 | − 0.4 | ||

| 6-ring | ALA 306 | π-H | 3.73 | − 0.7 | ||

| SB4 | O 9 | ARG 435 | H-donor | 2.99 | − 2.2 | − 8.9932 |

| Br 37 | ARG 375 | Halogen bonding | 3.31 | − 1.0 | ||

| SB5 | O 9 | MET 311 | H-donor | 3.40 | − 1.2 | − 8.6219 |

| S 30 | ARG 435 | H-donor | 3.87 | − 0.9 | ||

| I 37 | MET 447 | Halogen bonding | 3.99 | − 0.8 | ||

| O 26 | ARG 115 | H-acceptor | 3.50 | − 0.6 | ||

| [Ni( SB5-H)(OH)(H2O)] | O 9 | MET 311 | H-donor | 3.76 | − 1.1 | − 8.5098 |

| I 37 | MET 447 | Halogen bonding | 4.10 | − 1.0 | ||

| Sulfamethoxazole moiety of standard drug | N 15 | LEU 372 | H-donor | 3.24 | − 1.1 | − 6.2313 |

| O 13 | MET 374 | H-acceptor | 3.08 | –1.6 |

Figure 15.

Ligand-receptor interactions of SB5 and its Ni(II) complex versus 3s7s protein, using the Molecular Operating Environmental module (MOE 2015.10) software.

Also, the ligands SB4 and SB2 exhibited reasonable interaction with the target protein with scoring energies of − 8.9932 and − 8.3594 kcal/mol, respectively, indicating their high binding affinity with the receptor protein51. Effectively short H-bond was observed in most of the docked protein–ligand complexes. As an example, the interaction of SB1 and SB4 through O(27) with ARG 115 amino acid and O(9) with ARG 435 amino acid respectively, displayed bond lengths that are less than 3.5 Å8,48. Worth mentioning that the negative values of the binding energies (Table 4) indicate spontaneous interaction with the protein. Moreover, a number of halogen bonds were observed between ligands and some receptor sites inside the protein pocket (Figs. 15 and S26). However, these multiple weak bonds boost the inhibition impact of the ligands. Docking parameters against the protein 3s7s were also evaluated for a standard sulfa drug Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim). The drug contains a sulfamethoxazole moiety that resembles the synthesized ligands. The drug showed less scoring energy, Table 4 and Fig. S27, than the synthesized Schiff bases, implying high 3s7s inhibition activity for the ligands SB1- SB5.

Biological activity assessment

Antimicrobial potency study

The biological activity data of all ligands (SB1–SB5) and some selected complexes are summarized in Table 5 and Fig. 16. The observed mean zone diameter of inhibition in mm is considered a good index of the antimicrobial activity of the tested samples. For most of the studied strains, ligands show more inhibition efficacy than their corresponding complexes. However, a plausible comparative study of the antimicrobial potency of the compounds under investigation was achieved based on their minimum inhibitory concentration values in μM rather than µg/ml owing to their different molecular weights and according to the microdilution broth assay. Among the ligands, SB4 showed superior broad-spectrum activity in prohibiting microbial growth that is sometimes matching or even better than that of the utilized references. For instance, B. subtilis, E. coli, and A. fumigatus strains were very sensitive to SB4 with MIC values of 0.46, 7.54, and 0.95 µM, respectively, which are lower than that displayed by ampicillin (1.40 μM), gentamycin (8.38 μM), and ketoconazole (1.88 μM) as reference controls. In general, it is difficult to deduce a certain conclusion relating the observed activity with the skeleton of such compounds that contain diverse bioactive moieties such as benzenesulfonamide or salicylaldehyde imine including hydroxyl group, halogens, or heteroatomic thiazole ring, (Fig. 1). Notwithstanding such difficulty, the superior potency of the Schiff base ligand (SB4) could be credited to the consortium of different bioactive substituents as two bromine atoms and a thiazole ring attached to the Schiff base backbone structure. The two bromine substituents probably enhance the inhibitory effect of the attached system by their electron-withdrawing property as reported for analogous Schiff base compounds52,53. This is in harmony with the spotted decrease in the activity of SB1 or SB2 (mono-brominated Schiff bases), and SB3 (absence of thiazole ring) in comparison with SB4. Also, the substituent size (I or Br) is a crucial factor in determining the feasibility of pathogen inhibition54,55. Noticeably, the Gram-negative P. vulgaris bacteria showed the least susceptible character against most tested compounds (Table 5) pointing to the importance of its outer lipid membrane as an additional shield despite its thinner peptidoglycan wall56.

Table 5.

Antibacterial and antifungal inhibition zone in mm and the MIC (µM) of the Schiff bases and some of their complexes. NA: no activity, NT: not tested.

| Compound | Gram-positive bacteria | Gram-negative bacteria | Fungi | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | B. subtilis | P. vulgaris | E. coli | A. fumigatus | C. albicans | |

| SB1 |

14.6 ± 0.4 (351.9) |

16.2 ± 0.5 (176.0) | NA |

13.7 ± 0.3 (> 1000) |

15.2 ± 0.4 (176.0) |

NA |

| SB2 |

16.0 ± 0.4 (142.6) |

18.3 ± 0.6 (35.7) | NA |

13.0 ± 0.4 (> 1000) |

16.5 ± 0.6 (142.6) |

NA |

| SB3 |

15.0 ± 0.5 (> 1000) |

23.0 ± 0.8 (719.9) |

22.0 ± 0.77 (> 1000) |

24.0 ± 0.6 (> 1000) |

40.0 ± 0.9 (359.9) |

22.0 ± 0.7 (719.9) |

| SB4 |

20.6 ± 0.4 (7.54) |

24.4 ± 0.7 (0.46) |

NA |

19.8 ± 0.5 (7.54) |

23.4 ± 0.6 (0.95) |

NA |

| SB5 |

13.0 ± 0.3 (> 1000) |

20.0 ± 0.7 (511.3) |

12.0 ± 0.6 (> 1000) |

NA |

22.0 ± 0.7 (511.3) |

15.0 ± 0.5 (255.6) |

| [Ni(SB4–H)2]·4H2O |

15.0 ± 0.6 (> 1000) |

20.0 ± 0.8 (537.3) |

15.0 ± 0.5 (> 1000) |

12 0.0 ± 0.4 (> 1000) |

28.0 ± 0.9 (537.3) |

15.0 ± 0.6 (268.7) |

| [Ni(SB5–H)(OH)(H2O)] |

10.0 ± 0.4 (> 1000) |

15.0 ± 0.6 (88.8) |

18.0 ± 0.7 (> 1000) |

17.0 ± 0.7 (88.8) |

20.0 ± 0.9 (> 1000) |

19.0 ± 0.8 (> 1000) |

| Ampicillin |

23.7 ± 0.6 (2.85) |

26.4 ± 0.5 (1.40) | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| Gentamycin | NT | NT |

25.0 ± 0.3 (8.38) |

30.0 ± 0.4 (8.38) | NT | NT |

| Ketoconazole | NT | NT | NT | NT |

17.1 ± 0.3 (1.88) |

20.2 ± 0.4 (1.88) |

Figure 16.

Inhibition zone (mm) of the synthesized compounds against selected microbes.

The antiproliferative potency

The concentration of some selected synthesized compounds as anticancer candidates to inhibit the growth of the proliferative cells by 50% (IC50) in μM was evaluated against MCF-7 (human breast cancer cell line). All ligands and some of their nickel complexes showed appreciable cytotoxicity against MCF-7 (Table 6 and Figs. 17 & S28), compared to cisplatin as a chemotherapy standard drug for breast cancer. Based on the IC50 values, both SB2 (16.0 μM) and SB4 (18.8 μM) have nearly equipotent antiproliferative activity as cisplatin (19.0 μM) against MCF-7 cells and both are more active than SB1 (28.2 μM) and SB3 (29.7 μM) (Table 6). This variety in IC50 values points to the importance of the existence of the thiazole moiety and Br atom(s) in the building structure of the Schiff base ligands (SB2 and SB4) (Fig. 1) as deduced in the antimicrobial Sect. 8,55. Interestingly, SB5 (6.32 μM) exhibited threefold inhibition efficacy more than cisplatin recommending it as a promising breast anticancer drug and in accord with US NCI program (IC50 < 10 μM)57. A similar cytotoxicity tendency was observed for complexes where [Ni(SB2–H)2]·3H2O (11.2 μM) and [Ni(SB4–H)2]·4H2O (4.33 μM) have nearly twofold or fourfold potency in comparison with cisplatin against the human MCF-7 cell lines. The double cytotoxicity of Ni(SB4–H)2]·4H2O could be related to the presence of two additional Br atoms than the case of [Ni(SB2–H)2]·3H2O complex as both complexes have the same 4-coordinate geometry, metal to ligand ratio (1:2), and the same bioactive functional groups (benzenesulfonamide, thiazole, and salicylaldehyde imine). Unlike the SB5 ligand, [Ni(SB5–H)(OH)(H2O)] complex (1:1) has insignificant activity against MCF-7 cells where the chelation suppresses the antiproliferation in this case as discerned from the docking simulation.

Table 6.

Cytotoxicity activity (IC50) in μg/ml and µM of Schiff bases and some of their complexes.

| Compounds | MCF-7 | OEC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| μg/ml | μM | μg/ml | |

| SB1 | 10.0 ± 0.9 | 28.2 ± 1.9 | NT |

| SB2 | 7.0 ± 0.6 | 16.0 ± 1.2 | NT |

| SB3 | 12.9 ± 1.2 | 29.7 ± 1.8 | NT |

| SB4 | 9.73 ± 1.0 | 18.8 ± 1.3 | 49.53 ± 1.95 |

| SB5 | 3.86 ± 0.5 | 6.32 ± 0.8 | NT |

| [Ni( SB2–H)2]·3H2O | 11.3 ± 1.1 | 11.2 ± 0.9 | 62.23 ± 3.11 |

| [Ni( SB4–H)2]·4H2O | 5.04 ± 0.6 | 4.33 ± 0.5 | 33.59 ± 1.68 |

| [Ni( SB5–H)(OH)(H2O)] | 365 ± 24.6 | > 100 | > 100 |

| Cisplatin | 5.71 ± 0.7 | 19.0 ± 2.3 | 32.68 ± 2.74 |

Figure 17.

Inhibitory activity of the synthesized ligands against breast carcinoma cells MCF-7.

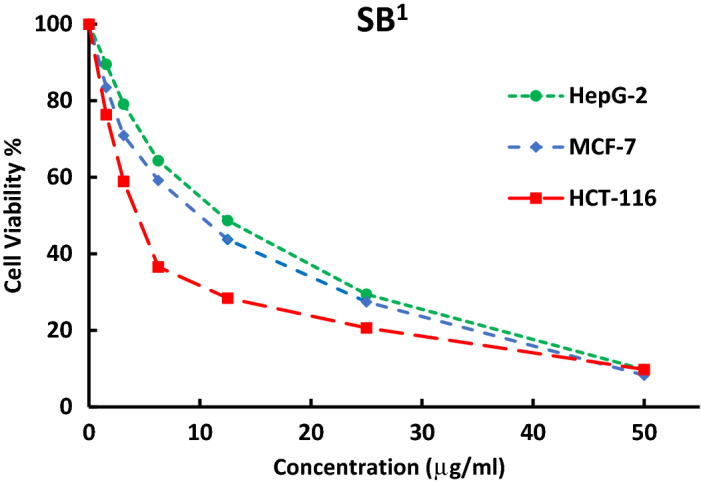

Furthermore, a comparative study was also made to compare the cytotoxicity of some ligands (SB1 and SB2) against different human cell lines HCT-116 (colon carcinoma), HepG-2 (hepatocellular carcinoma), and MCF-7 (breast carcinoma) (Figs. 18, 19). The investigated ligands SB1 and SB2 exhibited the same trend of cytotoxicity where the best inhibitory activity was observed against HCT-116 (IC50 12.4 and 12.3 μM) and the least was against HepG-2 (IC50 33.8 and 21.7 μM), respectively. Noteworthy, SB4 and all Ni (II) complexes exhibited less cytotoxic activity against the human normal oral epithelial cell, OEC, compared to cisplatin Table 6 and Fig. S29.

Figure 18.

The inhibitory dose curves of SB1 against three cell lines HepG-2, MCF-7, and HCT-116.

Figure 19.

The inhibitory dose curves of SB2against three cell lines HepG-2, MCF-7, and HCT-116.

Conclusion

In the current investigation, five new nickel complexes of halogenated sulfonamide-based Schiff bases (SB1–SB5) were synthesized and structurally explored by microanalytical analyses, FT-IR, NMR, UV–Vis., MS, and thermal analysis techniques. Spectral studies supported the bidentate coordination mode of all ligands towards the Ni(II) through the phenolic oxygen after deprotonation and the nitrogen atom of the azomethine group. The magnetic data revealed that the geometries of complexes are octahedral, square planar, or tetrahedral. The recorded molecular ion peaks (m/z) are in accordance with the determined formula mass from the microanalytical technique. The molecular descriptor parameters calculated by DFT-B3LYP/ Lanl2dz and the molecular docking simulation with the breast cancer protein (3s7s) approved the structural-activity relationship of the investigated compounds. SB4 showed the most significant inhibition activity towards some pathogen strains (B. subtilis, E. coli, and A. fumigatus) which is attributed to the presence of two electron-withdrawing bromine atoms in the salicylidene moiety and the attached thiazole ring to the bioactive benzenesulfonamide group. According to the IC50 values, SB5 and [Ni(SB4–H)2]·4H2O have nearly threefold or fourfold potency in comparison with cisplatin against breast carcinoma cells (MCF-7) recommending them as promising antiproliferative agents after further drug authorization processes. Ultimately, the nickel (II) complex derived from SB4 is economically expected to be of less expense with respect to other chemotherapeutic platinum-based drugs.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to convey their appreciation to Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt for offering technical and administrative support.

Author contributions

Author contribution RMI Elsamra, AM Ramadan, and MS Masoud contributed to the study design, RMI Elsamra and AM Ramadan performed the experiments and analysis of the data. RMI Elsamra and AM Ramadan contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-24512-y.

References

- 1.Hassan MA, Omer AM, Abbas E, Baset W, Tamer TM. Preparation, physicochemical characterization, and antimicrobial activities of novel two phenolic chitosan Schiff base derivatives. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:11416. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29650-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Safdari F, Raissi H, Shahabi M, Zaboli M. DFT calculations and molecular dynamics simulation study on the adsorption of 5-fluorouracil anticancer drug on graphene oxide nanosheet as a drug delivery vehicle. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2017;27:805–817. doi: 10.1007/s10904-017-0525-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makhova NN, Belen’kii LI, Gazieva GA, Dalinger IL, Konstantinova LS, Kuznetsov VV, Kravchenko AN, Krayushkin MM, Rakitin OA, Starosotnikov AM, Fershtat LL. Progress in the chemistry of nitrogen-, oxygen-and sulfur-containing heterocyclic systems. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2020;89:55–124. doi: 10.1070/RCR4914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masoud MS, Soayed AA, Almesmari SA, Elsamra RMI. New mixed-ligand complexes of cytosine and its silver nanoparticles: Spectral, analytical, theoretical and biological activity studies. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2021;31:2842–2858. doi: 10.1007/s10904-021-01945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pervaiz M, Munir A, Riaz A, Saeed Z, Younas U, Imran M, Ullah S, Bashir R, Rashid A, Adnan A. Amalgamation, scrutinizing, and biological evaluation of the antimicrobial aptitude of thiosemicarbazide Schiff bases derivatives metal complexes. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022;141:109459. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2022.109459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amer HH, Eldrehmy EH, Abdel-Hafez SM, Alghamdi YS, Hassan MY, Alotaibi SH. Antibacterial and molecular docking studies of newly synthesized nucleosides and Schiff bases derived from sulfadimidines. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:17953. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97297-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mondal S, Mondal TK, Rajesh Y, Mandal M, Sinha C. Copper (II)-sulfonamide Schiff base complexes: Structure, biological activity and theoretical interpretation. Polyhedron. 2018;151:344–354. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2018.05.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramadan AM, Bayoumi HA, Elsamra RMI. Synthesis, characterization, biological evaluation, and molecular docking approach of nickel (II) complexes containing O, N-donor chelation pattern of sulfonamide-based Schiff bases. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2021;35:e6412. doi: 10.1002/aoc.6412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffith EC, Wallace MJ, Wu Y, Kumar G, Gajewski S, Jackson P, Phelps GA, Zheng Z, Rock CO, Lee RE, White SW. The structural and functional basis for recurring sulfa drug resistance mutations in Staphylococcus aureus dihydropteroate synthase. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1369. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muthukumar R, Karnan M, Elangovan N, Karunanidhi M, Thomas R. Synthesis, spectral analysis, antibacterial activity, quantum chemical studies and supporting molecular docking of Schiff base (E)-4-((4-bromobenzylidene) amino)benzenesulfonamide. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2022;99:100405. doi: 10.1016/j.jics.2022.100405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nunes P, Yildizhan Y, Adiguzel Z, Marques F, Costa Pessoa J, Acilan C, Correia I. Copper (II) and oxidovanadium (IV) complexes of chromone Schiff bases as potential anticancer agents. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2022;27:89–109. doi: 10.1007/s00775-021-01913-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parsekar SU, Fernandes J, Banerjee A, Chouhan OP, Biswas S, Singh M, Mishra DP, Kumar M. DNA binding, cleavage and cytotoxicity studies of three mononuclear Cu (II) chloro-complexes containing N-S donor Schiff base ligands. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2018;23:1331–1349. doi: 10.1007/s00775-018-1620-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kargar H, Adabi Ardakani A, Munawar KS, Ashfaq M, Tahir MN. Nickel (II), copper (II) and zinc (II) complexes containing symmetrical Tetradentate Schiff base ligand derived from 3, 5-diiodosalicylaldehyde: Synthesis, characterization, crystal structure and antimicrobial activity. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2021;18:2493–2503. doi: 10.1007/s13738-021-02207-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elangovan N, Gangadharappa B, Thomas R, Irfan A. Synthesis of a versatile Schiff base 4-((2-hydroxy-3, 5-diiodobenzylidene) amino) benzenesulfonamide from 3, 5-diiodosalicylaldehyde and sulfanilamide, structure, electronic properties, biological activity prediction and experimental antimicrobial properties. J. Mol Struct. 2022;1250:131700. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thakur S, Gil DM, Frontera A, Chattopadhyay S. Exploration of Br⋯ O halogen bonding interactions in dinuclear vanadium (V) complexes with Schiff base ligands. Polyhedron. 2020;187:114676. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2020.114676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kordestani N, Rudbari HA, Fernandes AR, Raposo LR, Luz A, Baptista PV, Bruno G, Scopelliti R, Fateminia Z, Micale N, Tumanov N. Copper (ii) complexes with tridentate halogen-substituted Schiff base ligands: Synthesis, crystal structures and investigating the effect of halogenation, leaving groups and ligand flexibility on antiproliferative activities. Dalton Trans. 2021;50(11):3990–4007. doi: 10.1039/d0dt03962d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daraie M, Bagheri D, Malmir M, Heravi MM. Investigation of halloysite nanotubes and Schiff base combination with deposited copper iodide nanoparticles as a novel heterogeneous catalytic system. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:23658. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02991-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behpour M, Ghoreishi SM, Mohammadi N, Soltani N, Salavati-Niasari M. Investigation of some Schiff base compounds containing disulfide bond as HCl corrosion inhibitors for mild steel. Corros. Sci. 2010;52:4046–4057. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2010.08.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yousif E, Hasan A, El-Hiti GA. Spectroscopic, physical and topography of photochemical process of PVC films in the presence of Schiff base metal complexes. Polymers. 2016;8:204. doi: 10.3390/polym8060204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang XF, Zhang YB, Wang XL, Tang JF, Ruan BF. Synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activities of a dinuclear copper (II) complex with bis (2-[(2-hydroxy-ethylimino)-methyl]-4, 6-diiodo-phenol) J. Coord. Chem. 2011;64:630–636. doi: 10.1080/00958972.2011.552604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Sonbati AZ, Mahmoud WH, Mohamed GG, Diab MA, Morgan SM, Abbas SY. Synthesis, characterization of Schiff base metal complexes and their biological investigation. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019;33:e5048. doi: 10.1002/aoc.5048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reiss A, Cioateră N, Dobrițescu A, Rotaru M, Carabet AC, Parisi F, Gănescu A, Dăbuleanu I, Spînu CI, Rotaru P. Bioactive Co (II), Ni (II), and Cu (II) complexes containing a tridentate sulfathiazole-based (ONN) Schiff base. Molecules. 2021;26:3062. doi: 10.3390/molecules26103062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muthukumar R, Karnan M, Elangovan N, Karunanidhi M, Sankarapandian V, Thomas R. Synthesis, spectral, computational, wavefunction and molecular docking studies of 4-((thiophene-2-ylmethylene) amino) benzenesulfonamide from sulfanilamide and thiophene-2-carbalaldehyde. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2022;99(10):100718. doi: 10.1016/j.jics.2022.100718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brewster CM. Schiff's bases from 3, 5-dibromo-salicylaldehyde. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1924;46:2463–2468. doi: 10.1021/ja01676a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu SP, Shi L, Lv PC, Fang RQ, Zhu HL. Synthesis and antibacterial activities of metal (II) complexes with Schiff bases derived from 3, 5-diiodosalicylaldehyde. J. Coord. Chem. 2009;62:2048–2057. doi: 10.1080/00958970902741251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeffery GH, Bassett J, Mendham J, Denney RC. Vogel's Textbook of Quantitative Chemical Analysis. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frisch, M.J., Trucks, G.W., Schlegel, H.B., Scuseria, G.E., Robb, M.A., Cheeseman, J.R. Gaussian 09, Revision A.02, Gaussian Inc, Wallingford CT 34, Wallingford CT (2009).

- 28.Dennington, R. D., Keith, T. & Millam, J. GaussView, Version 4.1. 2 (Semichem Inc., Shawnee Mission, KS, 2007).

- 29.Becke AD. A new mixing of Hartree-Fock and local density-functional theories. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:1372–1377. doi: 10.1063/1.464304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-ghamry MA, Elzawawi FM, Aziz AAA, Nassir KM, Abu-El-Wafa SM. New Schiff base ligand and its novel Cr (III), Mn (II), Co (II), Ni (II), Cu (II), Zn (II) complexes: Spectral investigation, biological applications, and semiconducting properties. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:17942. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-22713-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biemer JJ. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing by the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 1973;3:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gecgel C, Simsek UB, Turabik M, Ozdemir S. Synthesis of titanium doped iron based metal–organic frameworks and investigation of their biological activities. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020;30:749–757. doi: 10.1007/s10904-019-01329-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramadan AM, Elsamra RMI, Bondock S. New pyrazole-4-carbothioamide-based metal complexes: Synthesis, spectral characterization, computational, antimicrobial, and antitumor investigations. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2021;35:e6102. doi: 10.1002/aoc.6102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Mutabagani LA, Abdelrazek FM, Gomha SM, Hebishy AS, Abdelfattah MS, Hassan SM, Sayed AR, Elaasser MM. Synthesis and biological evaluation of thiazolyl-ethylidene hydrazino-thiazole derivatives: A novel heterocyclic system. Appl. Sci. 2021;11:8908. doi: 10.3390/app11198908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagpal P, Singh RV. Toxicological effects, biological aspects and spectral characterization of organoboron (III) complexes of sulfonamide-imines. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2004;18:221–226. doi: 10.1002/aoc.610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abu-Melha KS, El-Metwally NM. Synthesis and spectral characterization of some investigated thiocarbohydrazone binuclear complexes with an illustrated EPR study for d1 complexes. Transit. Met. Chem. 2007;32:828–834. doi: 10.1007/s11243-007-0274-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Gammal OA, Mohamed FS, Rezk GN, El-Bindary AA. Synthesis, characterization, catalytic, DNA binding and antibacterial activities of Co (II), Ni (II) and Cu (II) complexes with new Schiff base ligand. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;326:115223. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.115223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khansari-Zadeh SH, Farrokhpour H, Tabrizchi M, Kianfar AH, Momeni MM. Study of the structural ligand effects on the fragmentation pattern of some Schiff base complexes of V (IV), Cu (II) and Ni (II) against the IR laser radiation using Matrix-free LDI-TOF technique. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2019;436:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2018.11.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharaby CM, Amine MF, Hamed AA. Synthesis, structure characterization and biological activity of selected metal complexes of sulfonamide Schiff base as a primary ligand and some mixed ligand complexes with glycine as a secondary ligand. J. Mol. Struct. 2017;1134:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2016.12.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKnight J, Cheesman MR, Thomson AJ, Miles JS, Munro AW. Identification of charge-transfer transitions in the optical spectrum of low-spin ferric cytochrome P-450 Bacillus megaterium. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;213:683–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cotton FA, Wilkinson G, Murillo CA, Bochmann M. Advanced Inorganic Chemistry. 6. New York: Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mansour AM, Shehab OR. Spectroscopic and TDDFT studies of N-phenyl-N′-(3-triazolyl) thiourea) compounds with transition metal ions. Arabian J. Chem. 2021;14:102932. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.102932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Awadi N, Shuaib NM, El-Dissouky A. A Synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of nickel (II) complexes of 1-benzotriazol-1-yl-[(pX-phenyl) hydrazone] propan-2-one. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2006;65:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2005.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramadan AM, Alshehri AA, Bondock S. Synthesis, physico-chemical studies and biological evaluation of new metal complexes with some pyrazolone derivatives. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2019;23:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.jscs.2019.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kulandaisamy A, Panneerselvam M, Solomon RV, Jaccob M, Ramakrishnan J, Poomani K, Maruthamuthu M, Tharmalingam N. Halogen-Based 17β-HSD1 Inhibitors: Insights from DFT, Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Studies. Molecules. 2022;27:3962. doi: 10.3390/molecules27123962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elsebach M, Sierda E, Goedecke JJ, Bignardi L, Hermanowicz M, Rohde M, Wiesendanger R, Bazarnik M. In situ synthesis of metal–salophene complexes on intercalated graphene. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2020;124:4279–4287. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b08943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.West DX, Swearingen JK, Valdés-Martínez J, Hernández-Ortega S, El-Sawaf AK, van Meurs F, Castiñeiras A, Garcia I, Bermejo E. Spectral and structural studies of iron (III), cobalt (II, III) and nickel (II) complexes of 2-pyridineformamide N (4)-methylthiosemicarbazone. Polyhedron. 1999;18:2919–2929. doi: 10.1016/S0277-5387(99)00210-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamad A, Khan MA, Ahmad I, Khalil R, Khalid M, Abbas U, Azhar R, Uddin J, Batiha GES, Khan A, Shafiq Z. Bio-oriented synthesis of new sulphadiazine derivatives for urease inhibition and their pharmacokinetic analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:18973. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-98413-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mehmood A, Jones SI, Tao P, Janesko BG. An orbital-overlap complement to ligand and binding site electrostatic potential maps. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2018;58:1836–1846. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghosh D, Lo J, Morton D, Valette D, Xi J, Griswold J, Hubbell S, Egbuta C, Jiang W, An J, Davies HM. Novel aromatase inhibitors by structure-guided design. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:8464–8476. doi: 10.1021/jm300930n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mansour MA, AboulMagd AM, Abdel-Rahman HM. Quinazoline-Schiff base conjugates: In silico study and ADMET predictions as multi-target inhibitors of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) proteins. RSC Adv. 2020;10:34033–34045. doi: 10.1039/D0RA06424F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cui Y, Dong X, Li Y, Li Z, Chen W. Synthesis, structures and urease inhibition studies of Schiff base metal complexes derived from 3, 5-dibromosalicylaldehyde. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;58:323–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saedi Z, Hoveizi E, Roushani M, Massahi S, Hadian M, Salehi K. Synthesis, characterization, anticancer properties and theoretical study of asymmetrical Cd (II) N2-Schiff base complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1176:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.08.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo J, Yuan H, Jia D, Guo M, Li Y. Synthesis and improved photochromic properties of pyrazolones in the solid state by incorporation of halogen. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2017;171:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2016.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krátký M, Konečná K, Janoušek J, Janďourek O, Maixnerová J, Kalivodová S, Trejtnar F, Vinšová J. Sulfonamide-salicylaldehyde imines active against methicillin-and trimethoprim/sulfonamide-resistant Staphylococci. Future Med. Chem. 2021;13:1945–1962. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2021-0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raman N, Jeyamurugan R, Sudharsan S, Karuppasamy K, Mitu L. Metal based pharmacologically active agents: Synthesis, structural elucidation, DNA interaction, in vitro antimicrobial and in vitro cytotoxic screening of copper (II) and zinc (II) complexes derived from amino acid based pyrazolone derivatives. Arabian J. Chem. 2013;6:235–247. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2012.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuete V, Ngameni B, Wiench B, Krusche B, Horwedel C, Ngadjui BT, Efferth T. Cytotoxicity and mode of action of four naturally occuring flavonoids from the genus Dorstenia: Gancaonin Q, 4-hydroxylonchocarpin, 6-prenylapigenin, and 6, 8-diprenyleriodictyol. Planta Med. 2011;77:1984–1989. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1280023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.