Abstract

Earlier investigations have not shown an important role for gamma interferon (IFN-γ) in the early clearance of chlamydial infection from the murine female genital tract. In a model using a human genital isolate of Chlamydia trachomatis in IFN-γ and IFN-γ receptor knockout mice, we were able to demonstrate a major role for IFN-γ in mediating control of infection throughout the course of infection.

Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) has been shown to have antichlamydial activity both in vitro (1, 2) and in vivo (9). Recently, Perry et al. (8) demonstrated that IFN-γ-deficient (IFN-γ−/−) mice were capable of clearing vaginal chlamydial (mouse pneumonitis [MoPn]) infections at the same rate as control animals during the first 3 weeks. After this initial period, however, the IFN-γ−/− animals continued to maintain local infection, and many progressed to dissemination and death. It was concluded that the bulk of chlamydial clearance from the genital tract was not mediated by IFN-γ, while elimination of chronic chlamydial infection and prevention of dissemination was. Cotter et al. (3) reported similar infection kinetics but observed dissemination in the control animals as well, although to a lesser degree. Johansson et al. (6) observed somewhat different infection kinetics when they infected IFN-γ receptor-deficient (IFN-γ-R−/−) mice with a human genital Chlamydia trachomatis strain. Early infection was equally intense in the control and deficient animals, but, after the 10th day, infection was slower to resolve in the deficient animals. Both groups were, however, able to eliminate infection by the 45th day, and there was no mention of dissemination or persistence of infection in the IFN-γ-R−/− animals. We have examined the course of chlamydial genital tract infection by using a human genital (serovar D) isolate of C. trachomatis in both IFN-γ−/− and IFN-γ-R−/− mice and have observed infection kinetics different from those reported previously (3, 6, 8), and we conclude that IFN-γ plays a major role in both early and late infection in this model.

IFN-γ-R−/− mice, produced in the 129 Sv/Ev background using the AB1 ES stem cell line, were obtained from Michael Aquest (University of Zurich). IFN-γ−/− mutants, isolated in the same background, were supplied by Edouard Cantin (City of Hope National Medical Center). These mice were derived by using an ES cell clone carrying the IFN-γ null mutation kindly supplied by Tim Stewart (Genentech, Inc.). Both mutant strains were bred and maintained at the City of Hope National Medical Center Animal Resource Center. Age-matched female 129 Sv/Ev mice were purchased from Teconic Farms. A human genital isolate of C. trachomatis (serovar D) (5) was propagated, titrated, and isolated in cycloheximide-treated McCoy cell monolayers by standard techniques. The MoPn agent was kindly provided by Joseph Igietseme (Morehouse School of Medicine). In order to induce prolonged diestrus and thus enhance the initial infection rate, progesterone, in the form of medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera; Upjohn), was administered subcutaneously in 2.5-mg doses 10 and 3 days prior to infection (4, 10). Mice were inoculated intravaginally by direct instillation of 10 μl of bacterial suspension containing either 2 × 104 inclusion forming units (IFU) of serovar D or 9 × 103 IFU of MoPn agent. The presence of chlamydiae in the lower genital tract was determined by culturing the material obtained by swabbing the vaginal vault and ectocervix with a calcium alginate swab which was stored at −70°C in 2-SP transport medium. Tissues were aseptically isolated and stored at −70°C in 2-SP, thawed, and homogenized, and centrifugation clarified supernatants were cultured for chlamydiae. Regardless of type, specimens were plated in microtiter plates containing cycloheximide-inhibited McCoy cell monolayers, incubated at 37°C for 72 h, fixed, and stained with iodine. Iodine-stained inclusions were enumerated.

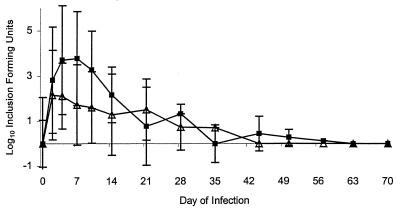

Chlamydial (both serovar D and MoPn) genital tract infection was monitored in IFN-γ−/−, IFN-γ-R−/−, and control (129 Sv/Ev) mice for 70 days (Fig. 1 and 2; Table 1). In MoPn infections (Fig. 1), no significant differences were noted in bacterial shedding between the IFN-γ−/−, IFN-γ-R−/−, and control animals (data not shown for IFN-γ-R−/− animals). There was a trend of less shedding in the control animals during the first 2 weeks of infection, and there were a few IFN-γ−/− animals (and no control animals) who had persistent infection beyond day 44 (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

MoPn strain shedding from the genital tract of IFN-γ−/− (■) and normal (129 Sv/Ev) (▵) mice. Each point represents the mean of the log10 IFU ± standard deviation.

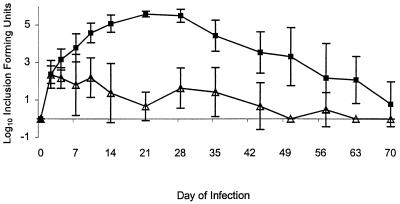

FIG. 2.

Serovar D shedding from the genital tract of IFN-γ−/− (■) and normal (129 Sv/Ev) (▵) mice. Each point represents the mean of the log10 IFU ± standard deviation.

TABLE 1.

Lower genital tract cultures

| Infecting strain | Mouse strain | Animal | Culture result(s)a on indicated day after infection

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 14 | 21 | 28 | 35 | 44 | 50 | 57 | 63 | 70 | |||

| MoPn | IFN-γ−/− | D1 | 1,050 | 99,500 | 338,000 | 58,500 | 210 | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/− | 150 | 0/− | 0/+ | 0/− |

| D2 | 6,880 | 8,944 | 4,560 | 1,620 | 33,500 | 1,810 | 250 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| D3 | 78,000 | 232,500 | 228,220 | 30,000 | 1,500 | 0/+ | 370 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| D4 | 500,000 | 500,000 | 130,000 | 53,500 | 12,000 | 90 | 10 | 0/− | 30 | 0/+ | 10 | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| D5 | 330 | 158,000 | 98,222 | 34,000 | 90 | 10 | 0/− | 0/− | 120 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| D6 | 0/− | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| D7 | 360 | 29,000 | 369,200 | 30,000 | 20 | 0/+ | 48,000 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/+ | 0/− | ||

| D8 | 0/+ | 0/− | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| Normal | A1 | 530 | 50 | 0/+ | 0/+ | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | |

| A2 | 80 | 690 | 810 | 1,150 | 30 | 3,940 | 730 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| A3 | 250 | 1,560 | 940 | 17,000 | 700 | 1,420 | 0/− | 20 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| A4 | 2,130 | 30,000 | 110 | 1,000 | 14,500 | 12,000 | 1,010 | 220 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| A5 | 740 | 49,000 | 1,190 | 370 | 0/+ | 20 | 0/+ | 110 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| A6 | 330 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| A7 | 0/+ | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| A8 | 30 | 0/− | 600 | 0/− | 70 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| Pb | 0.435 | 0.165 | 0.062 | 0.107 | 0.305 | 0.357 | 0.457 | 0.09 | 0.178 | 0.351 | 0.351 | NAc | NA | ||

| D | IFN-γ−/− | B1 | 360 | 970 | 50,000 | 370,000 | 120,000 | 250,000 | 50,000 | 12,000 | 25,000 | 25,000 | 500,000 | 12,000 | 490 |

| B2 | 140 | 220 | 5,800 | 50,000 | 120,000 | 500,000 | 500,000 | 250,000 | 5,480 | 12,000 | 100 | 20 | 0/− | ||

| B3 | 380 | 4,450 | 4,960 | 25,000 | 25,000 | 250,000 | 500,000 | 250,000 | 12,000 | 5,800 | 650 | 1,610 | 0/+ | ||

| B4 | 100 | 500 | 8,510 | 25,000 | 120,000 | 500,000 | 500,000 | 1,500 | 80 | 90 | 30 | 30 | 10 | ||

| B5 | 790 | 1,870 | 8,380 | 12,000 | 250,000 | 500,000 | 500,000 | 5,220 | 90 | 6,570 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| B6 | 20 | 640 | 11,210 | 25,000 | 370,000 | 250,000 | 500,000 | 120,000 | 25,000 | 25,000 | 1,480 | 350 | 440 | ||

| B7 | 5,030 | 12,000 | 120 | 9,800 | 25,000 | 500,000 | 250,000 | 50,000 | 50,000 | 12,000 | 0/+ | 40 | 0/+ | ||

| B8 | 60 | 2,450 | 12,000 | 120,000 | 370,000 | 500,000 | 250,000 | 7,770 | 1,160 | 0/+ | 180 | 270 | 0/+ | ||

| Normal | C1 | 70 | 20 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | |

| C2 | 90 | 250 | 0/+ | 1,220 | 0/− | 0/+ | 580 | 140 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| C3 | 170 | 30 | 0/+ | 40 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| C4 | 160 | 230 | 12,000 | 810 | 2,260 | 0/− | 120 | 3,800 | 900 | 0/− | 140 | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| C5 | 840 | 980 | 740 | 800 | 0/− | 70 | 100 | 80 | 250 | 0/+ | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| C6 | 620 | 110 | 130 | 750 | 30 | 10 | 280 | 60 | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| C7 | 850 | 310 | 2,190 | 280 | 1,870 | 10 | 40 | 100 | 0/− | 0/− | 60 | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| C8 | 80 | 190 | 110 | 50 | 710 | 30 | 170 | 0/+ | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | 0/− | ||

| P | 0.944 | 0.003 | 0.011 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.042 | 0.002 | 0.106 | ||

Results are presented as number of IFU per 100 μl of specimen (1.0-ml total volume)/presence (+) or absence (−) of IFU upon passage.

P (t test) of mean log10 IFU for comparison of normal and IFN-γ−/− animals.

NA, not applicable.

In serovar D infection (Fig. 2), there were clear and significant differences between the control and both IFN-γ−/− and IFN-γ-R−/− (data not shown for the latter) mice. While the chlamydial infection continued to progress logarithmically beginning by the day 2 and peak at over 5 logs of chlamydiae by the 3rd week in the IFN-γ−/− and IFN-γ-R−/− mice, the control mice limited the chlamydial infection from the beginning to a much lower level (<3 logs) throughout the course. By day 50 the control animals had virtually eliminated the infection. The deficient animals, on the other hand, did not begin to show a decrease in shedding until day 35 and continued to shed chlamydiae throughout the period of monitoring (70 days), albeit at a slowly decreasing rate.

Multiple organs were removed, examined, and cultured on days 7 and 21 in order to determine if there was any invasion or dissemination of infection from the genital tract (Table 2). In both serovar D- and MoPn-infected control animals there was no evidence of infection outside the genital tract. However, in both serovar D- and MoPn-infected IFN-γ−/− animals there was evidence of extension to local lymph nodes. In MoPn-infected IFN-γ−/− mice, there was one case of dissemination to lung tissue and there were two cases of mesenteric node involvement.

TABLE 2.

Organ cultures

| Infecting strain | Mouse strain | Day postinoculation | No. of animals | No. of animals with culture-positive:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vagina and cervix | Uterine horns | Ovaries | Local lymph nodes | Lungs | Liver | Spleen | Kidney | Mesenteric lymph nodes | ||||

| MoPn | Normal | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 21 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| IFN-γ−/− | 7 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 21 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| D | Normal | 7 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 21 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| IFNγ−/− | 7 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 21 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

Earlier investigations have not demonstrated an important role for IFN-γ in the early clearance of chlamydiae from the genital tract. Most did show a role for IFN-γ in eradicating late or chronic infection and in attenuating dissemination (3, 6, 8). When we infected IFN-γ−/− mice with MoPn we observed similar results although the differences in late infection were not significant. When we infected animals with the human genital isolate serovar D, however, we saw striking differences in infection kinetics between IFN-γ−/− and control animals beginning as early as day 4 and continuing throughout the observation period (70 days). There was a decline in the IFN-γ−/− curve toward the end, but this apparent control of infection may just be a reflection of the waning effect of progesterone, which maintains the animals in diestrus, providing fresh target (epithelial) cells for infection (4). Alternatively, there could be another immune mechanism coming into play at this time. Booster progesterone injections might help to differentiate between these two possible scenarios.

These differences observed between the two models may reflect the differences in the chlamydia biovars used for infection. The MoPn agent, a mouse biovar of C. trachomatis first isolated from a mouse, is much more virulent in mice than human biovars (11) and is quite capable of causing systemic infection (7). Human genital (non-lymphogranuloma venereum) strains of C. trachomatis rarely invade beyond the genital tract and do not disseminate systemically. Johansson et al. (6) used a human genital isolate (serovar D) of C. trachomatis in their studies, but their infectious inoculum contained 107 IFU, a much higher dose than our inoculum of approximately 104 IFU. Their larger challenge dose may have overwhelmed any local defense mechanisms and masked any differences between the deficient and control mice that might have been operative during the early period of infection.

In this model of murine genital tract infection using a human genital isolate of C. trachomatis, IFN-γ appears to play a major role in mediating control of shedding of bacteria throughout the course of infection and may be the major factor determining the termination of such shedding.

REFERENCES

- 1.Byrne G I, Carlin J M, Merkert T P, Arter D L. Long-term effects of gamma interferon on chlamydia-infected host cells: microbicidal activity follows microbistasis. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1318–1320. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1318-1320.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrne G I, Krueger D A. Lymphokine-mediated inhibition of Chlamydia replication in mouse fibroblasts is neutralized by anti-gamma interferon immunoglobulin. Infect Immun. 1983;42:1152–1158. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.3.1152-1158.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cotter T W, Ramsey K H, Miranpuri G S, Poulsen C E, Byrne G I. Dissemination of Chlamydia trachomatis chronic genital tract infection in gamma interferon gene knockout mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2145–2152. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2145-2152.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito J I, Harrison H R, Alexander E R, Billings L J. Establishment of genital tract infection in the CF-1 mouse by intravaginal inoculation of a human oculogenital isolate of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:577–582. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.4.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito J I, Lyons J M, Airo-Brown L P. Variation in virulence among oculogenital serovars of Chlamydia trachomatis in experimental genital tract infection. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2021–2023. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.2021-2023.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson M, Schon K, Ward M, Lycke N. Genital tract infection with Chlamydia trachomatis fails to induce protective immunity in gamma interferon receptor-deficient mice despite a strong local immunoglobulin A response. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1032–1044. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.1032-1044.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nigg C. Unidentified virus which produces pneumonia and systemic infection in mice. Science. 1942;95:49. doi: 10.1126/science.95.2454.49-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perry L L, Feilzer K, Caldwell H D. Immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis is mediated by T helper 1 cells through IFN-γ-dependent and -independent pathways. J Immunol. 1997;158:3344–3352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rank R G, Ramsey K H, Pack E A, Williams D M. Effect of gamma interferon on resolution of murine chlamydial genital infection. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4427–4429. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4427-4429.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuffrey M D, Taylor-Robinson D. Progesterone as a key factor in the development of a mouse model of genital-tract infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. FEMS Microbiol. 1981;12:111–115. . (Letter.) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams D M, Schachter J, Drutz D J, Sumaya C V. Pneumonia due to Chlamydia trachomatis in the immunocompromised (nude) mouse. J Infect Dis. 1981;143:238–241. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]