Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of global mortality and disease burden. The perceived risk of CVD, a central psychological construct, may affect health behavior change and maintenance, such as lifestyle modification and medication adherence. Risk perception varies based on the knowledge of risk in the context of cultural health-world views. Little is known about CVD-related knowledge and risk perception in China. The aim of this study is to cross-culturally translate, adapt, and evaluate the psychometric properties of the Attitudes and Beliefs about Cardiovascular Disease (ABCD) Risk Perception Questionnaire in Chinese. The translation and cross-cultural adaptation process followed established guidelines. A cross-sectional study of 318 adults between April and May 2022 was conducted in Zhejiang province. The study evaluated the item- and scale-level psychometric properties and validity indices of the ABCD risk perception questionnaire. The exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of the risk scale supported a three-factor solution that accounts for 69.63% of the total variance, corresponding to risk perception (F1), perceived benefits and intention to change physical activity (F2), and perceived benefits and intention to change dietary habits (F3). Adequate content validity (I-CVI = 0.852–1.00, S-CVI = 946) was ensured by expert panel. The internal consistency of the dimensions showed good results ranging from 0.801 to 0.940 for Cronbach's α, and 0.853 to 0.952 for McDonald’s ω. The item analysis of knowledge dimension indicated that the item difficulty index was 0.440 to 0.852, the item discrimination index was 0.572 to 0.707. This study confirmed that the Chinese version of the ABCD risk perception questionnaire has good psychometric properties in terms of measuring CVD-related knowledge and risk perception in the Chinese adult population, which can lead to the development of individually tailored CVD-risk reduction intervention programs or risk communication programs by health providers.

Subject terms: Cardiology, Health care, Risk factors

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease prevention in China

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of global mortality and a major contributor to disability1 as well as the leading cause of death and disease burden in China, accounting for 40% of deaths2. An unhealthy lifestyle, including physical inactivity, poor dietary habits, tobacco use, and excessive alcohol consumption, has been identified as an alterable risk factor for CVD3. As such, CVD risk can be reduced through the adoption of a healthy lifestyle, which has been recommended by CVD primary and secondary prevention guidelines4,5. Nevertheless, a large number of individuals have a low awareness of CVD risk factors and poor treatment and control rates of these major risk factors2.

Relationship between CVD knowledge, risk perception, and healthy lifestyle

Understanding of individual risk and the potential benefits of prevention is a prerequisite for the implementation of preventive measures6. Further, active involvement of the target population is critical for CVD prevention interventions. The perceived risk of CVD, a central psychological construct, may affect health behavior change and maintenance7,8; specifically, individuals who perceive themselves as having a higher risk of CVD are more likely to adopt a healthy lifestyle or adhere to prevention measures for CVD9,10. Although the perception of risk can be formed by comparing risk-factor knowledge with one’s lifestyle and experience11, risk perception varies based on knowledge of the risk in the context of cultural health-world views12. Without taking these views into consideration, people may under- or overperceive their CVD risk. If they over-perceive their CVD risk, then people may be thrust into situations that they are ill-prepared to handle and suffer psychological strain; in turn, if they under-perceive their CVD risk, individuals may ignore the risk and be less likely to modify their health behaviors13.

CVD knowledge and risk perception measurements

Poor knowledge or misperception of CVD risk impedes the attainment of better health outcomes. Thus, the measurement of CVD knowledge and risk perception is essential to promoting a healthy lifestyle intervention. A single-item measurement of absolute or relative CVD risk has been used in many studies in the past four decades14–16, which is not sufficient to assess the multiple dimensions of risk perception17. The Perception of Risk of Heart Disease Scale (PRHDS)18 or the Coronary Risk Individual Perception Scale (CRIP)8, as a type of specific risk perception measurement, focuses mainly on heart disease and does not measure CVD risk knowledge; as such, it is not appropriate for risk perception evaluation. In response to this need, Woringer et al. constructed the Attitudes and Beliefs about Cardiovascular Disease (ABCD) Risk Perception Questionnaire to measure CVD knowledge and risk perception among individuals in England19. The ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire consists of 26 items classified into four subscales: Knowledge of CVD Risk and Prevention, Perceived Risk of Heart Attack/Stroke, Perceived Benefits and Intention to Change Behavior, and Healthy Eating Intentions. The ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire has been translated to other languages and applied in Hungary20, Belgium21 and Malay22; and research has shown that this scale had good psychometric properties in terms of accessing CVD-related knowledge and risk perception. Further, the Packages of Interventions for Cardiovascular Diseases in Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa identified the ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire as a potential tool to measure CVD knowledge and risk perception prior to and after an intervention21.

Purpose of the study

To the best of our knowledge, there is not an appropriate CVD knowledge and risk perception measurement in the Chinese cultural context. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the validity and reliability of a Chinese version ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire. This questionnaire is a multidimensional measurement that can lead to the development of individually tailored CVD risk reduction interventions or risk communication programs by health providers.

Materials and methods

Study setting and participants

A cross-sectional survey was conducted and reported, following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement23. A convenience sample was recruited for the study from health check center and endocrinology department of the second affiliated hospital of Zhejiang University school of medicine in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, China. A paper-based survey and online survey platform powered by WJX (www.wjx.com) between April and May 2022 were performed. The inclusion criteria were being a Zhejiang citizen, age greater than 18 years, not undergoing treatment for a psychiatric disorder, and no barriers to communication. Before the assessment process, the participants were informed about the topic of the study and gave informed consent. The sample size was based on the recommended subject-to-item of (5–10):1, for which 130–260 participants were required. Taking into consideration a missing data rate of 10% and adequate sample size for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)24, 318 participants were included.

Measures

Chinese version of the ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire

Permission was obtained from the author to translate the English version to Chinese. We conducted this procedure following the Cross-cultural Adaptation of Self-report Measures guidelines25,26 and consensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement instruments27.

Translation procedure

First, two native Mandarin Chinese-speaking translators who were fluent in English translated the English ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire into Mandarin Chinese independently. Then, the two Chinese versions were compared with the original scale by a third translator. The research team discussed any discrepancies and formed a consensual Mandarin version. This consensual Mandarin version was given to two bilingual translators who were blind to the original English version and who translated the Mandarin version back into English. The back-translated versions of ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire were compared with the original one, and the translators clarified a few ambiguities and inconsistencies.

Cross-cultural adaptation process

An expert panel, including a cardiologist, two nurse specialists from a cardiology department, a health management specialist, a methodologist, and a language professional, reviewed all translation reports with translators in terms of semantic equivalence, idiomatic equivalence, experiential equivalence, and conceptual equivalence until consensus was achieved. The pre-final version proposed by these experts was sufficiently close to the original one. Finally, all experts rated the relevance of each item of the ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire to the Chinese context on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = very irrelevant; 4 = very relevant). Further, comprehensiveness and intelligibility, according to the COSMIN rating system, was determined by experts, using a 3-point scale (1 = not clear, 2 = not sufficient, 3 = sufficient)27.

Pilot testing of the pre-final version

The pre-final ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire was tested among 40 Chinese adults according to the aforementioned cross-cultural adaptation guidance25. Participants took about 5 min to complete the questionnaire. In addition, each participant was invited to comment on his or her understanding of the wording, particularly in regard to confusing or unreadable statements. After minor revisions, the final ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire was generated for psychometric evaluation.

Final Chinese version of the ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire (ABCD-C)

This questionnaire consists four subscales. The Knowledge of CVD Risk and Prevention diemsion consists of eight statements about CVD risk, regarding whether the respondent agrees or disagrees with the statements with three options (True/False/I don’t know). For each item, the correct answer was scored as 1, and an incorrect or “I don’t know” answer was scored as 0. Values are summed to create a summary score that can range from 0 to 8, for which higher values indicate higher CVD-related knowledge. The other dimensions include Perceived Risk of Heart Attack/Stroke (8 items), Perceived Benefits and Intention to Change Behavior (7 items), and Healthy Eating Intentions (3 items). Answer options are presented on a 4-point scale and range from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. Items 15, 21 and 26 were reverse-coded.

Other measures

Demographic characteristics included age, sex, marital status, education level, religion, employment status, smoking and drinking status, family history, and related variables. Subjective health status was estimated through the question, “In general, how would you rate your health status?” (1 = very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = fair, 4 = good, 5 = excellent). Smoking and drinking status was determined by the answer to the question, “What is your current smoking/drinking status?” (1 = never smoked/drank, 2 = ever smoked/drank, 3 = currently smoke/drink). In addition, one item estimated absolute CVD risk: “What do you think the risk of your getting any kind of cardiovascular disease within the next 10 years is?” by selecting a number from 1 to 10, with 0 = no risk and 10 = very high risk, a question routinely used in CVD risk perception related studies16,28.

Data collection procedures

Data were collected on-site and online. Well-trained and eligible research assistants who were all nursing Ph.D. candidates collected data through face-to-face interviews. All participants were informed of the purpose of the research and that their participation was voluntary and confidential. Questionnaires with more than three blank items in the paper survey were excluded. No items were missing for the online survey because all items were required, but a completion time of less than 2 min or similar option choices invalidated the questionnaire, which was excluded. In addition, the ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire was completed twice by twenty participants who were randomly selected from the total sample in two-week intervals to calculate the test–retest reliability.

Psychometric assessments and statistical analysis

Scale reliability of the ABCD-C was tested by internal consistency and test–retest reliability. The degree of internal consistency is described as Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω. An item‐total corrected correlation coefficient was employed to calculate items discrimination. Test–retest reliability was assessed by an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), rooted in a two-way analysis of the variance in a random effect model. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of ICC value also reported. Both Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s ω and ICC values higher than 0.70 are recommended which indicate that the scale has acceptable reliability29,30.

Construct validity and content validity were evaluated to verify the validity of ABCD-C. The content validity of the scale was assessed by the content validity index of items (I-CVI) and the scale content validity index-average (S-CVI/Ave) based on the ratings of experts on this questionnaire. A S-CVI/Ave value of 0.9 is considered an excellent criterion and a value of 0.8 as the lower content validity limit for acceptance of the whole scale31, I-CVI ≥ 0.78 is considered to be appropriate if the number of experts is ≥ 632. Exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with maximum likelihood were performed to explore the dimensionality of items in more detail. The standardized factor loadings and an estimated of the variance in the measured variable explained by the latent variable (R2), together with fit statistics (χ2, CFI—comparative fit index, IFI—incremental fit index; TLI—Tucker-Lewis index, RMSEA—root mean square error of approximation). A CFA > 0.95, TLI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.08 were considered acceptable33. Average variance extracted (AVE) was applied to assess the internal convergent validity of each factor, with a score ≥ 0.5 indicating satisfactory convergent validity34. The square root of AVE value exceeding each of its correlations with other factors indicate appropriate discriminant validity34. To evaluate the concurrent validity, the Spearman rank correlations were analyzed between the ABCD-C and single-item CVD subjective risk perception. The correlation of |r|= 0.10–0.30, |r|= 0.31–0.60, and |r|= 0.61–1.00 were considered low, moderate and high, respectively35.

Item difficulty for knowledge subscale was determined by descriptive statistics, consistent with previous knowledge studies36. The difficulty level index was calculated as the number of correct answers divided by the total number of answers, a higher index indicates a lower level of difficulty37. The difficulty level of a test is expected to be around 0.5037. The corrected correlations between the performance among individual items and the overall test were calculated to determine the ability of each item to discriminate high- and low-scoring participants. A correlation value of 0.5 to 0.7 indicated good discrimination power38.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 26.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), was used for statistical analysis. The data are expressed as the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD). Mean difference of ABCD-C scores across the sociodemographic variables were determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey`s multiple comparison test. The effect size partial eta squared (η2) was calculated through the sum of squares of the effect divided by the total sum of squares; η2 = 0.01 indicates small effect, η2 = 0.06 with medium and η2 = 0.014 with large effect36. CFA was conducted using AMOS 22.0 to assess the structural validity of the scale. SPSSAU was used to conduct reliability analysis. A p-value less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval

The study protocol had been approved by the Institutional Review Board of the second affiliated hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (No. ID: 2022-0280).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The study was in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Translation and cultural adaptation

Slight differences were identified in sentence statements between the original and translated versions, and minor revisions were made. In Items 14, 17, and 18, “five portions of fruit and vegetables” was not easily understood by participants without a medical background; therefore, we used “500 g of fruit and vegetables,” according to the Cardiovascular Primary Prevention guidelines in China39. Similarly, “2–1/2 h” is not idiomatic in Chinese, so 2–1/2 h was changed to 2.5 h. In the pilot testing, 40 participants were randomly selected to identify whether the questionnaire could be understood correctly. All participants were satisfied with the number and comprehensibility of the items.

Respondent characteristics

A total of 341 participants were approached for the study. Of these, 93 (27.3%) completed the paper-based questionnaire, and seven answers (2.0%) had more than three blanks and were excluded. A total of 248 participants (72.7%) finished the online survey, for which five responses had a completion time of less than 2 min, and 11 responses had very similar option choices for most items; thus, the data from 16 questionnaires (4.7%) were excluded. No difference in response rate was found between paper-based and online participants, other comparisons across characteristic variables were showed in supplementary file Table S1. As such, the data from 318 (93.3%) surveys were included in the final analysis. Ages ranged between 20 and 87 years (M = 42.04, SD = 16.89). The score of single item subjective risk perception ranged from 0 to 10 (M = 2.55, SD = 1.625). Table 1 displays the sociodemographic information of the participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

| Characteristic | n (%) | ABCD-C (M ± SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk perception (Range 0–32) |

PA (Range 0–24) |

Dietary (Range 0–16) |

Knowledge (Range 0–8) |

||

| Total sample | 318 | 17.30 ± 5.17 | 18.11 ± 4.16 | 12.76 ± 2.21 | 5.82 ± 2.19 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 134 (42.1) | 17.64 ± 5.10 | 18.19 ± 3.68 | 12.53 ± 2.16 | 5.43 ± 2.22 |

| Female | 184 (57.9) | 17.05 ± 5.22 | 18.05 ± 4.49 | 12.93 ± 2.24 | 6.11 ± 2.13 |

| ANOVA F (p value) | 1.000 (0.318) | 0.087 (0.768) | 2.533 (0.112) | 7.487 (0.007) | |

| Partial η2 | 0.003 | < 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.023 | |

| Education level | |||||

| Junior school or below | 44 (13.8) | 18.57 ± 3.53 | 19.32 ± 3.10a | 13.05 ± 1.84 | 3.39 ± 1.48abc |

| High school/specialized secondary school | 59 (18.6) | 18.17 ± 2.90 | 18.95 ± 3.11 | 12.69 ± 2.00 | 4.73 ± 2.10ade |

| Specialty/bachelor | 193 (60.7) | 16.80 ± 5.91 | 17.58 ± 4.54a | 12.66 ± 2.36 | 6.52 ± 1.86bdf |

| Postgraduate or above | 22 (6.9) | 16.86 ± 5.15 | 18.18 ± 4.32 | 13.27 ± 2.07 | 7.55 ± 1.01cef |

| ANOVA F (p value) | 2.118 (0.098) | 3.159 (0.025) | 0.788 (0.501) | 49.367 (< 0.001) | |

| Partial η2 | 0.020 | 0.029 | 0.007 | 0.320 | |

| Ethnic group | |||||

| Han Chinese | 309 (97.2) | 17.31 ± 5.17 | 18.07 ± 4.20 | 12.75 ± 2.24 | 5.83 ± 2.20 |

| Minorities | 9 (2.8) | 17.11 ± 5.39 | 19.44 ± 2.29 | 13.00 ± 1.00 | 5.67 ± 2.12 |

| ANOVA F (p value) | 0.013 (0.911) | 0.946 (0.331) | 0.107 (0.743) | 0.047 (0.828) | |

| Partial η2 | < 0.001 | 0.003 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Employment status | |||||

| Employed | 193 (60.7) | 16.91 ± 5.73 | 17.89 ± 4.39 | 12.85 ± 2.18 | 6.48 ± 1.92 |

| Unemployed | 125 (39.3) | 17.90 ± 4.10 | 18.46 ± 3.76 | 12.62 ± 2.26 | 4.81 ± 2.21 |

| ANOVA F (p value) | 2.807 (0.095) | 1.463 (0.227) | 0.882 (0.348) | 50.979 (< 0.001) | |

| Partial η2 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.139 | |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Current smoking | 43 (13.5) | 18.56 ± 2.76 | 18.19 ± 2.61 | 12.47 ± 1.94 | 4.81 ± 2.18 |

| Non-smoking/quit smoking | 275 (86.5) | 17.11 ± 5.43 | 18.10 ± 4.36 | 12.81 ± 2.25 | 5.98 ± 2.16 |

| ANOVA F (p value) | 2.951 (0.087) | 0.015 (0.902) | 0.887 (0.347) | 10.833 (0.001) | |

| Partial η2 | 0.009 | < 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.033 | |

| Drinking status | |||||

| Current drinking | 55 (17.3) | 18.58 ± 3.78* | 18.49 ± 4.10 | 13.02 ± 2.13 | 5.33 ± 2.31 |

| Non-drinking/quit drinking | 263 (82.7) | 17.03 ± 5.38* | 18.03 ± 4.18 | 12.71 ± 2.23 | 5.93 ± 2.16 |

| ANOVA F (p value) | 4.112 (0.054) | 0.546 (0.460) | 0.896 (0.345) | 3.424 (0.065) | |

| Partial η2 | 0.013 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.011 | |

| CVD family history | |||||

| Yes | 28 (8.8) | 19.04 ± 5.78 | 18.79 ± 2.79* | 12.89 ± 2.23 | 5.79 ± 2.40 |

| No | 290 (91.2) | 17.13 ± 5.08 | 18.05 ± 4.27* | 12.75 ± 2.21 | 5.83 ± 2.18 |

| ANOVA F (p value) | 3.477 (0.063) | 0.800 (0.372) | 0.108 (0.742) | 0.009 (0.923) | |

| Partial η2 | 0.011 | 0.003 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Subjective health status | |||||

| Excellent | 120 (37.7) | 16.30 ± 5.74a | 17.43 ± 5.32a | 12.83 ± 2.62 | 6.53 ± 2.07abc |

| Good | 154 (48.4) | 17.53 ± 4.72 | 18.92 ± 2.99a | 12.77 ± 1.97 | 5.49 ± 2.16a |

| Fair | 39 (12.3) | 19.49 ± 4.45a | 17.31 ± 3.53 | 12.56 ± 1.68 | 5.26 ± 2.18b |

| Poor | 5 (1.6) | 17.40 ± 4.33 | 15.80 ± 4.08 | 12.40 ± 2.70 | 3.60 ± 1.14c |

| ANOVA F (p value) | 4.031 (0.008) | 4.121 (0.007) | 0.188 (0.904) | 8.519 (< 0.001) | |

| Partial η2 | 0.037 | 0.038 | 0.002 | 0.075 | |

ABCD-C, Chinese version of Attitudes and Beliefs about Cardiovascular Disease (ABCD) Risk Perception Questionnaire; RP, risk perception; PA, perceived benefits and intention to change physical activity; DH, perceived benefits and intention to change dietary habits; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

*The significance level of the mean difference is 0.05; ** The significance level of the mean difference is 0.001. Same lower-case alphabets denote a significant difference between each level of variables in Colum, p < 0.05.

Psychometric analysis

Validity

The content validity of ABCD-C was assessed through expert consultation, according to the COSMIN Checklist27. The CVI for “relevance,” “comprehensiveness,” and “intelligibility” ranged from 85 to 100%. The results indicated that the content validity of the ABCD-C was excellent, with the I-CVI as between 0.852 and 1.00 and S-CVI as 0.946.

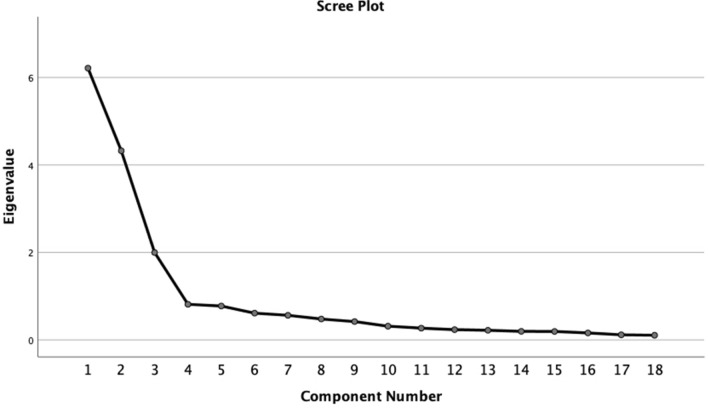

Structural validity was investigated via EFA. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value was 0.861, and Bartlett`s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), which indicated that the 18-item ABCD risk perception questionnaire was adequate in terms of EFA (the Knowledge of CVD Risk and Prevention subscale had 8 items, and the data type did not qualify for factor analysis). Based on the scree plot (Fig. 1) and parallel analysis, a three-factor solution emerged with a cumulative variance contribution rate of 69.632%, although the pattern of factor loadings in our analysis was slightly different from the original one. The domains in the original ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire were Perceived Risk of Heart Attack/Stroke (Items 1–8), Perceived Benefits and Intention to Change Behavior (Items 9–15), and Healthy Eating Intentions (Items 16–18). In our analysis, Items 14 and 16–18 had the same factor loading (Factor 3); in addition, all of these items expressed healthy diet semantically. Thus, we renamed the domains according to loading patterns and Hassen HY et al.’s results21: Factor 1: risk perception (RP), Factor 2: perceived benefits and intention to change physical activity (PA); and Factor 3: perceived benefits and intention to change dietary habits (DH) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Scree plot of the exploratory factor analysis.

Table 2.

Factor loadings of the EFA.

| Item No | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Item score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Skewness (SE) | Kurtosis (SE) | ||||

| 09 | 0.826 | 0.188 | 0.118 | 2.45 (0.82) | − 0.86 (0.14) | 0.89 (0.27) |

| 10 | 0.882 | 0.119 | 0.040 | 2.25 (0.77) | − 0.45 (0.14) | 0.77 (0.27) |

| 11 | 0.825 | 0.104 | 0.111 | 2.21 (0.79) | − 0.35 (0.14) | 0.73 (0.27) |

| 12 | 0.836 | 0.016 | 0.046 | 2.01 (0.69) | − 0.35 (0.14) | 1.04 (0.27) |

| 13 | 0.825 | 0.119 | 0.037 | 2.03 (0.69) | − 0.27 (0.14) | 1.17 (0.27) |

| 14 | 0.891 | 0.053 | 0.038 | 2.11 (0.74) | − 0.51 (0.14) | 0.35 (0.27) |

| 15 | 0.776 | − 0.083 | − 0.057 | 2.12 (0.89) | 0.31 (0.14) | − 0.08 (0.27) |

| 16 | 0.863 | − 0.070 | − 0.047 | 2.13 (0.71) | − 0.29 (0.14) | 0.49 (0.27) |

| 17 | 0.132 | 0.856 | 0.101 | 2.93 (0.86) | − 1.22 (0.14) | 2.27 (0.27) |

| 18 | 0.064 | 0.860 | 0.122 | 2.95 (0.96) | − 1.05 (0.14) | 1.72 (0.27) |

| 19 | 0.008 | 0.783 | 0.201 | 3.19 (0.88) | − 1.56 (0.14) | 3.17 (0.27) |

| 20 | 0.072 | 0.787 | 0.192 | 2.85 (0.88) | − 0.88 (0.14) | 1.14 (0.27) |

| 21 | 0.040 | 0.803 | − 0.023 | 2.93 (0.79) | − 0.85 (0.14) | 1.48 (0.27) |

| 23 | 0.013 | 0.721 | 0.252 | 3.26 (0.80) | − 1.33 (0.14) | 2.44 (0.27) |

| 22 | − 0.006 | 0.190 | 0.767 | 3.25 (0.59) | − 0.87 (0.14) | 3.70 (0.27) |

| 24 | 0.195 | 0.188 | 0.809 | 3.11 (0.75) | − 0.89 (0.14) | 1.79 (0.27) |

| 25 | 0.041 | 0.189 | 0.881 | 3.13 (0.68) | − 0.82 (0.14) | 1.86 (0.27) |

| 26 | − 0.031 | 0.078 | 0.716 | 3.27 (0.67) | − 0.76 (0.14) | 0.96 (0.27) |

| Factor score [Median, M(P25, P75)] | − 0.714 (− 0.329, 0.746) | 0.101 (− 0.309, 0.566) | 0.005 (− 0.453, 0.570) | |||

| Eigenvalues | 5.730 | 4.069 | 2.735 | |||

| Variance explained (%) | 31.833 | 22.603 | 15.195 | |||

| Cumulative variance explained | 31.833 | 54.437 | 69.632 | |||

Varimax was the applied rotation method. Factor loadings with absolute values higher than 0.5 are in bold. Factor 1: Risk perception, Factor 2: Perceived benefits and intention to change physical activity, and Factor 3: Perceived benefits and intention to change dietary habits.

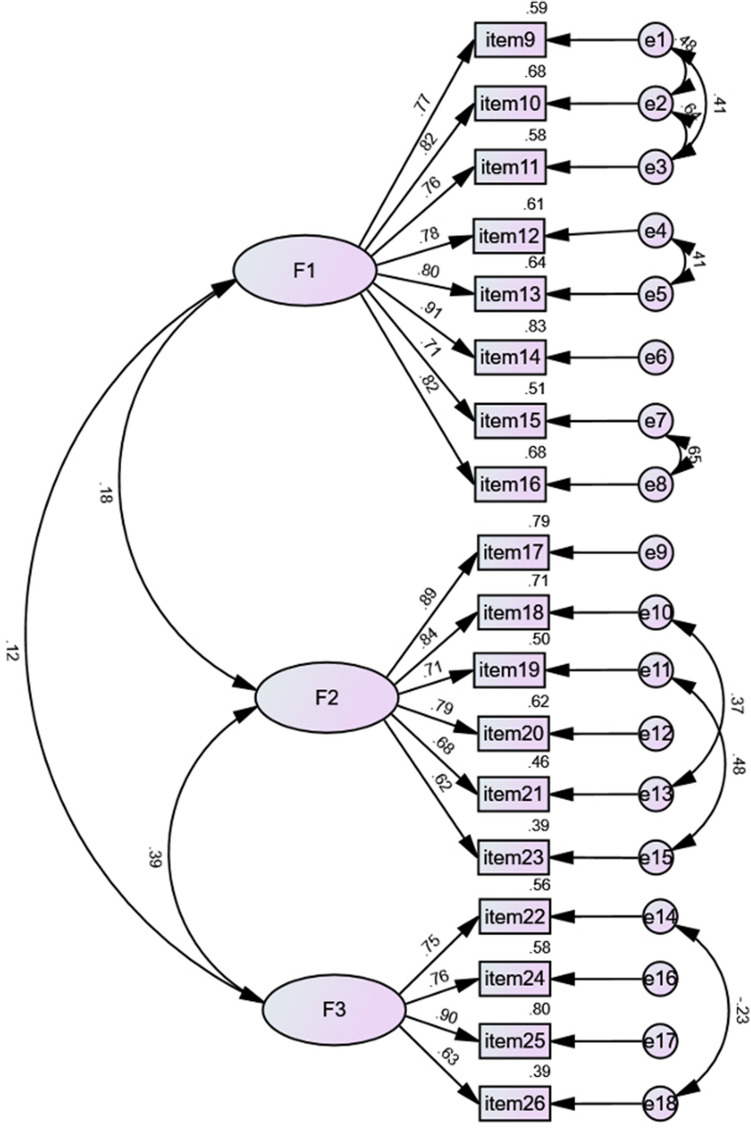

We further performed CFA to confirm the EFA-derived 3-factor structure. The initial model indices suggested an inadequate model fit, and eight paths of covariance between errors were added based on the modification indices. The adjusted model had satisfactory fit indices: χ2 = 348.69, df = 124, χ2/df = 2.812, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.948, IFI = 0.948, TLI = 0.936; RMSEA = 0.076 (90% CI 0.066 to 0.085). The CFA path diagram of the ABCD-C plotted with standardized parameter estimates is displayed in Fig. 2. We also performed CFA to confirm the model structure of original ABCD, the results showed that the model fit indices were mediocre: χ2 = 1019.254, df = 132, χ2/df = 7.722, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.736, IFI = 0.796, TLI = 0.762; RMSEA = 0.146 (90% CI 0.137 to 0.154).

Figure 2.

Factor structure model and estimated value of the standardized loadings of ABCD-C.

The score of AVE for three subscales were higher than 0.5, in addition, all square root of AVE scores exceeded each of their correlations with other subscales which indicating appropriate convergent and discriminant validity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Convergent and discriminant validity analysis.

| ABCD-C | AVE | Inter-dimension correlations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP | PA | DH | ||

| RP | 0.671 | 0.819 | ||

| PA | 0.603 | 0.140* | 0.777 | |

| DH | 0.573 | 0.121* | 0.368** | 0.757 |

AVE, average variance extracted; ABCD-C, Chinese version of Attitudes and Beliefs about Cardiovascular Disease (ABCD) Risk Perception Questionnaire; RP, risk perception; PA, perceived benefits and intention to change physical activity; DH, perceived benefits and intention to change dietary habits.

Bold characters show the square of root of average variance extracted values.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

The significant positive correlation was founded between ABCD-C and one-item subjective CVD risk perception (r = 0.258, P < 0.001). The correlation coefficient of four dimensions (knowledge, risk perception, PA and Dietary) and subjective CVD risk perception was 0.043 (P = 0.446), 0.466 (P < 0.001), − 0.145 (P = 0.010), and 0.008 (P = 0.890), respectively.

Internal consistency and reliability

We calculated internal consistency estimates of reliability based on the factorial solution of EFA. The Cronbach’s α values of the four dimensions ranged from 0.801 to 0.940, the McDonald’s ω ranged from 0.853 to 0.952, which indicated acceptable and satisfactory internal consistency (Table S7). The corrected item-total subscale correlations ranged from 0.448 to 0.853, and no individual item was found to greatly increase the Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω if deleted (Table S8). For the 2-week test–retest reliability, 20 participants finished the second test. The test–retest reliability showed acceptable results (ICC = 0.788, 95% CI 0.527 to 0.902).

Item difficulty for Knowledge subscale of ABCD-C

The item difficulty index was 0.726 (ranging from 0.44 to 0.85), which means that the CVD Knowledge subscale has a moderate difficulty level (Table 4). Four items (2–5) showed an item difficulty index of more than 0.80, which means these items were easier for participants. Item 7 had the highest difficulty level (0.44); thus, more than half of the participants could not answer this question correctly. Regarding discrimination ability, the point-biserial coefficients of the items ranged from 0.572 to 0.707 (Table 4), which indicating sufficient discrimination ability.

Table 4.

Item Statistic of Knowledge subscale of ABCD-C (N = 318, M ± SD).

| No | Knowledge subscale Items | Difficulty Index | Discrimination power |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stress is one of the main causes of heart attack and stroke | 0.701 | 0.659 |

| 2 | Walking and gardening are considered types of exercise that can lower the risk of having a heart attack or stroke | 0.852 | 0.572 |

| 3 | Moderately intensive activity of 2.5 h a week will reduce your chance of having a heart attack or stroke | 0.821 | 0.635 |

| 4 | People who have diabetics are at a higher risk of having a heart disease or stroke | 0.824 | 0.588 |

| 5 | Managing your stress levels will help to manage your blood pressure | 0.811 | 0.661 |

| 6 | Heavy drinking can increase your cholesterol and triglyceride levels | 0.780 | 0.656 |

| 7 | High-density lipoprotein is the "good" cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein is the "bad" cholesterol | 0.440 | 0.707 |

| 8 | A family history of heart disease is not a risk factor for high blood pressure | 0.594 | 0.693 |

Discussion

With the continuing burden of CVD worldwide, targeting the knowledge and risk perception of populations is critical to the performance of CVD primary and secondary prevention. Thus, a reliable and valid tool to measure CVD-related knowledge and subjective risk perception is needed. In response, Woringer et al. developed the ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire. To the best of our knowledge, the ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire had not been translated and validated in China. Thus, we conducted a cross-sectional study to cross-culturally adapt and validate the ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire into Chinese. We found that the Chinese version of the ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire was a reliable measurement. Thus, this questionnaire could be a valuable tool for public health providers, clinical practitioners, and researchers to evaluate an individual’s CVD knowledge and risk perception, which can be used to guide target CVD risk-reduction interventions.

The translation and adaptation processes were undertaken, following established guidelines26. When compared with the original scale, only two phrases were revised. In China, “five servings” as the diet unit is difficult to understand, as the definition of a “serving” varies. Hence, we revised “five servings” to “500 g,” according to the healthy diet recommendation of the Chinese CVD prevention guidelines39. Likewise, 2–1/2 h was revised to 2.5 h. Moreover, the total scale proved understandable and took about 6 to 10 min to complete.

We confirmed a three-factor structure for the 18-item scale, which accounted for 69.632% of the total variance; nevertheless, the pattern of factor loadings in our analysis was slightly different from the original one. The original subscales include perceived risk, perceived benefits and intention to change, and healthy eating intentions. The Hungarian version of the ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire contained the same constructs as the original one, but the pattern of factor loadings varied. In addition, they created a simplified 10-item short version based on the factor loadings of CFA and item meaning, of which risk perception, perceived benefits and healthy eating habits containing 4, 3, 3 items respectively20. The recent Dutch version is a revision of the original ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire, with two items added, and the subscale name was revised to Risk Perception, Perceived Benefits and Intention to Change Physical Activity, and Perceived Benefits and Intention to Change Dietary Habits, according to the factor analysis results21. In our analysis, Item 14 (“When I eat at least 500 g fruit and vegetables a day, I do something good for the health of my heart”), which was in Factor 2, showed a better loading to Factor 3. Further, we performed CFA to test the factorial structure, and the model fit indices were improved, which means that the item is logically related to Factor 3. This result was similar to the Dutch version21. In addition, we tested the model structure of the original ABCD questionnaire using our data, and the model fit indices were inferior to our model. Thus, we also revised the factor name in consideration of the factorial loading pattern, item meaning, and the Dutch version factor name, that is, Risk Perception, Perceived Benefits and Intention to Change Physical Activity, and Perceived Benefits and Intention to Change Dietary Habits.

The reliability evaluation showed that the ABCD -C was an acceptable instrument in this population. The Cronbach’s α value of ABCD-C was similar to those of the Dutch version (0.75, 0.93, 0.88, 0.84 for each of four dimensions)21 and slightly higher than those of the original scale (0.85, 0.82, 0.56 for last three dimensions)19 and Hungarian version (0.504, 0.945, 0.822, 0.756 for each of four dimensions)20. Cronbach’s α coefficients are an inherent property of the response pattern of a specific sample and not a characteristic of the scale itself30. Therefore, it is important to measure Cronbach’s α when validating an instrument in a different sample from that of the original participants. The results also indicated that the ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire was a reliable instrument when applied to Chinese population. In addition, we reported a higher Cronbach’s α value of risk perception dimension beyond Tavakol et al. recommendation30, it may suggest that some items were redundant as they were testing the same question but in a different guise. Further study would conduct to shorten item according to semantic and subjective judgment of expert team, and explore the internal consistency between shorter version and original versions.

The item difficulty analysis showed that the Knowledge subscale had a moderate difficulty level and a potential discriminatory capability. The CVD Knowledge subscale contains four easy items, three moderate items, and one difficult item; thus, it can differentiate participants sufficiently and provide an understanding of the individual’s CVD knowledge level. The knowledge score (46.8% participants had an accuracy rate higher than 80%) was slightly higher than that of other studies (28.85%)40, possibly due to that the education level of participants in our study were higher than in previous study.

The current study has several limitations. First, the study participants were recruited from a city in south China by convenience sampling and, this may lead to selection bias. Thus, the generalizability of the results of this study might be threatened, as a large number of the participants were recruited from Han ethic group and higher level of education. Further research should test the ABCD-C in more diverse sample from various regions of China. Second, we did not conduct CFA on a separate sample to confirm the structure of the factors resulting from the EFA. The results of CFA in our study will favor the EFA model and inflate the model fit indices. As such, we will test this factor structure in further study. Third, the concurrent validity was performed based on correlations between the scores of ABCD-C and single item CVD subjective risk perception which was widely used to evaluate CVD risk perception in previous studies16,41. It will be beneficial to analyze the relationship between ABCD-C and objective estimated CVD risk (e.g. prediction for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in China, China-PAR42) in further research, which allows conclusion of underestimation, overestimation or accurate risk perception to be drawn.

Conclusion

This is the first Chinese version of the ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire. The study followed a robust methodology in its translation and validation. This study confirmed that the ABCD-C has good psychometric properties to measure CVD-related knowledge and risk perception in the Chinese adult population.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Conceptualization, G.Z. and J.J.; Methodology, G.Z., D.C., G.W., H.J., and T.J.; Validation, G.Z., J.J., and Z.Y.; Formal analysis, G.Z. and T.J.; Investigation, G.Z. and Z.Y.; Data curation, G.Z. and D.C.; Writing, G.Z. and J.J.; Supervision, J.J.; and Project administration, Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-24620-9.

References

- 1.Roth GA, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020;76:2982–3021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen X, et al. Risk factors of stroke in Western and Asian countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:776. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pocnet C, et al. Personality, tobacco consumption, physical inactivity, obesity markers, and metabolic components as risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the general population. Psychol. Health Med. 2017;22:932–939. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2016.1255767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whelton PK, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018;71:2199–2269. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnett DK, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019;74:e177–e232. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navar AM, et al. Influence of cardiovascular risk communication tools and presentation formats on patient perceptions and preferences. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:1192–1199. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imes CC, Lewis FM. Family history of cardiovascular disease, perceived cardiovascular disease risk, and health-related behavior: a review of the literature. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2014;29:108–129. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e31827db5eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnhart JM, et al. Risk perception and its association with cardiac risk and health behaviors among urban minority adults: the Bronx Coronary Risk Perception study. Am. J. Health Promot. 2009;23:339–342. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.07072574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thakkar J, Heeley EL, Chalmers J, Chow CK. Inaccurate risk perceptions contribute to treatment gaps in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Intern. Med. J. 2016;46:339–346. doi: 10.1111/imj.12982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fung V, Graetz I, Reed M, Jaffe MG. Patient-reported adherence to statin therapy, barriers to adherence, and perceptions of cardiovascular risk. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0191817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Homko CJ, et al. Cardiovascular disease knowledge and risk perception among underserved individuals at increased risk of cardiovascular disease. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2008;23:332–337. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000317432.44586.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siaki LA, Loescher LJ, Trego LL. Synthesis strategy: building a culturally sensitive mid-range theory of risk perception using literary, quantitative, and qualitative methods. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013;69:726–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischhoff B, Bostrom A, Quadrel MJ. Risk perception and communication. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 1993;14:183–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.14.050193.001151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Lima MM, Jr, da Silva GR, Jensem Filho SS, Granja F. Association between perceived lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease and calculated risk in a male population in Brazil. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2016;12:279–286. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S107874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abed MA, Khalil AA, Moser DK. Awareness of modifiable acute myocardial infarction risk factors has little impact on risk perception for heart attack among vulnerable patients. Heart Lung. 2015;44:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desgraz B, Collet TH, Rodondi N, Cornuz J, Clair C. Comparison of self-perceived cardiovascular disease risk among smokers with Framingham and PROCAM scores: A cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e012063. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson RS, Zwickle A, Walpole H. Developing a broadly applicable measure of risk perception. Risk Anal. 2019;39:777–791. doi: 10.1111/risa.13207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ammouri AA, Neuberger G. The Perception of Risk of Heart Disease Scale: Development and psychometric analysis. J. Nurs. Meas. 2008;16:83–97. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.16.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woringer M, et al. Development of a questionnaire to evaluate patients' awareness of cardiovascular disease risk in England's National Health Service Health Check preventive cardiovascular programme. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014413. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martos T, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk perception in a Hungarian community sample: Psychometric evaluation of the ABCD Risk Perception Questionnaire. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e036028. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hassen HY, et al. Validation of the Dutch-Flemish translated ABCD questionnaire to measure cardiovascular diseases knowledge and risk perception among adults. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8952. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88456-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mat Said Z, et al. The Malay version of the attitudes and beliefs about cardiovascular disease (ABCD-M) risk questionnaire: A translation, reliability and validation study. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:1412. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13811-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Elm E, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hair, J. F.J., Black, W., Babin, B., Anderson, R. & Tatham, R. L. Mutivariate Data Analysis. Vol. 31 (2006).

- 25.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: A clear and user-friendly guideline. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2011;17:268–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mokkink LB, et al. COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018;27:1171–1179. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1765-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Figueiras MJ, Maroco J, Monteiro R, Caeiro R, Neto DD. Discerning the impact of personal and situational variables in risk perception of coronary heart disease. J. Health Psychol. 2017;22:483–492. doi: 10.1177/1359105315604379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lance CE, Butts MM, Michels LC. The sources of four commonly reported cutoff criteria: What did they really say? Organ. Res. Methods. 2006;9:202–220. doi: 10.1177/10944281052849. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011;2:53–55. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health. 2007;30:459–467. doi: 10.1002/nur.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polit DF, Beck CT. Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melnyk BM, Hsieh AP, Mu J. Psychometric properties of the Organizational Culture and Readiness Scale for System-Wide Integration of Evidence-Based Practice. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2022 doi: 10.1111/wvn.12603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fornell C, Larcker DF. Structural equation models with unobservable Variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981;18:382–388. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andresen EM. Criteria for assessing the tools of disability outcomes research. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2000;81:S15–20. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.20619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Do OD, et al. Cultural adaptation and validity testing of the Portuguese version of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:6465. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19116465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ozturk Birge A, Tel Aydin H, Salman F. The development of a delirium knowledge test for intensive care nurses: A validity and reliability study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2020;61:102900. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moosbrugger H, Kelava A. Testtheorie und Fragebogenkonstruktion. Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu D, Han Y, Ning G, Ma C. Guidelines for primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in China. Chin. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020;48:1000–1038. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hassen HY, Bowyer M, Gibson L, Abrams S, Bastiaens H. Level of cardiovascular disease knowledge, risk perception and intention towards healthy lifestyle and socioeconomic disparities among adults in vulnerable communities of Belgium and England. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:197. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-12608-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Homko CJ, et al. Gender differences in cardiovascular risk factors and risk perception among individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:483–488. doi: 10.1177/0145721710366757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo ZT, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk prediction models in the Chinese population—A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:1608. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13995-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.