Abstract

Objective:

Chemoradiation for patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) may achieve organ preservation, but appropriate patient selection remains unknown. This study investigates pre-treatment risk factors associated with functional and survival outcomes after radiation-based therapy in patients with advanced laryngeal SCC.

Methods:

A retrospective cohort study was performed on 75 adult patients with stage III or IV laryngeal SCC receiving definitive radiation-based therapy from 1997 to 2016 at a tertiary care center. Tracheostomy and gastrostomy dependence were the primary functional outcomes. Multivariable logistic regressions were performed to evaluate relationships between pre-treatment factors and tracheostomy and gastrostomy dependence. Time-to-event analyses were performed to determine risk factors associated with overall survival.

Results:

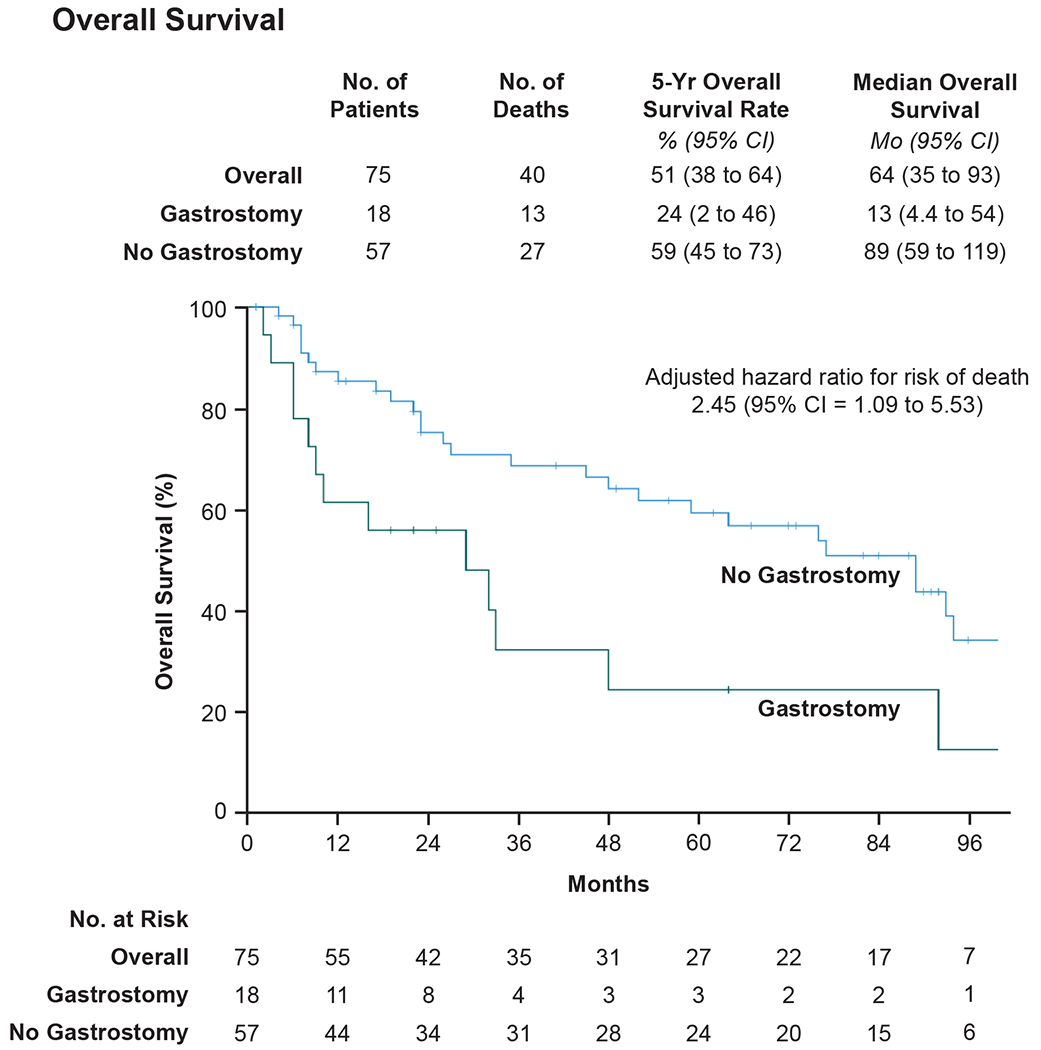

Among 75 patients included in analysis, 30 (40%) patients were tracheostomy dependent and 31 (41%) were gastrostomy tube dependent. Median length of follow up was 31 months (range = 1 to 142 months). Pre-treatment tracheostomy was a significant predictor of post-treatment tracheostomy (aOR = 13.9, 95% CI = 3.35 to 57.5) and moderate-severe comorbidity was a significant predictor of post-treatment gastrostomy dependence (aOR = 2.96, 95% CI = 1.04 to 8.43). The five-year overall survival was 51% (95% CI = 38 to 64%). Pre-treatment gastrostomy tube dependence was associated with an increased risk of death (aHR = 2.45, 95% CI = 1.09 to 5.53).

Conclusions:

Baseline laryngeal functional status and overall health in advanced laryngeal SCC are associated with poor functional outcomes after radiation-based therapy, highlighting the importance of patient selection when deciding between surgical and non-surgical treatment plans.

Keywords: laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, functional outcomes, tracheostomy, gastrostomy, chemoradiation

Introduction:

Chemoradiation therapy (CRT) has dramatically changed the management of advanced laryngeal cancer by offering the possibility of organ preservation. The Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study and RTOG 91-11 are landmark trials that found equivalent survival outcomes between laryngeal cancer patients that underwent definitive CRT and those managed with primary surgery1,2. Among those treated with induction chemotherapy and definitive radiation, the larynx was preserved in more than 70% of patients two years after treatment, suggesting that CRT may preserve the laryngopharynx without compromising oncologic outcomes. This has led to a paradigm shift towards non-surgical management to maximize functional outcomes and avoid the permanent morbidity associated with a total laryngectomy. In doing so, CRT may preserve important laryngopharyngeal functions, like deglutition and intelligible speech3.

Although CRT for laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) offers curative therapy with the possibility of organ preservation, poor functional and oncologic outcomes still occur. Full dose CRT is associated with various acute and late toxicities, including mucositis, throat pain, airway compromise, dysphagia, and recurrent pneumonias4–6. These side effects, combined with the local tissue destruction caused by the tumor itself, may render the preserved larynx non-functional7,8. In these cases, a salvage laryngectomy may be indicated, which has significantly higher risk of complications due to the challenges of operating in a previously irradiated surgical field combined with poor healing potential8,9. Furthermore, there is substantial evidence that the overall survival for advanced laryngeal SCC (stage III and IV) has decreased in the United States during the organ preservation era, regardless of treatment modality10,11. The reason for this decrease remains unknown, but the trend towards CRT for advanced laryngeal SCC may, in part, explain this decline in survival.

To better select patients for organ preservation treatment, some studies have investigated risk factors for post-treatment laryngopharyngeal dysfunction that require intervention. Most of the literature focuses on predictors of dysphagia, and relatively few studies have investigated the risk factors associated with laryngeal dysfunction12–16. By identifying factors that predict poor post-treatment laryngopharyngeal function in patients with advanced laryngeal SCC, patients at high risk of developing a non-functional larynx may benefit from primary total laryngectomy instead of non-surgical management to limit acute and late toxicities associated with definitive CRT and the additional risks of salvage surgery in a previously irradiated field.

The objective of this study was to determine whether pre-treatment laryngopharyngeal functional status, as measured by pre-treatment tracheostomy and gastrostomy tube dependence, in patients with advanced laryngeal SCC was associated with post-treatment functional and overall survival of patients treated with radiation-based therapy. Understanding predictors of a non-functional larynx after CRT may facilitate more nuanced patient counseling regarding post-treatment expectations for patients at high risk of developing laryngopharyngeal dysfunction.

Methods:

Study Population

A retrospective cohort study was performed at a tertiary care center in adults with stage III or IV laryngeal SCC who underwent definitive radiation-based therapy from 1997 to 2016. Patients that presented with early-stage laryngeal cancer (stage I or II) or recurrent disease, or those treated with primary surgical resection or palliative radiation-based therapy were excluded from the study. Patients were followed in a multi-disciplinary fashion, including regular surveillance with otolaryngology, radiation oncology, hematology-oncology, and serial imaging. Treatment regimens included radiation alone, concurrent chemoradiation therapy (CCRT), or induction chemotherapy and CCRT. Clinical data were extracted from electronic medical records. The adult comorbidity evaluation-27 (ACE-27), a validated comorbidity index in oncologic patients, was also calculated for each patient17. Pre-treatment factors included demographics, smoking status, tracheostomy, gastrostomy, weight loss (clinical documentation prior to treatment), dysphagia (clinical documentation by speech language pathologist or otolaryngologist), hoarseness, subglottic extension, and impaired true vocal fold (TVF) mobility on flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy.

Outcomes

Tracheostomy and gastrostomy tube dependence at last follow up or at first diagnosis of recurrence were the primary outcomes of this study because they represent definitive intervention for end-organ dysfunction following radiation-based therapy. Patients with a permanent stoma were considered equivalent to patients with a tracheostomy for the same reason. The primary outcomes were determined at either last follow up or at time of recurrence to maximize follow up length while mitigating recurrence as a potential confounder for placement of post-treatment tracheostomy or gastrostomy. Overall survival was a secondary outcome. The start date for time-to-event analysis was defined as the date of treatment initiation. An event was considered death from any cause. The Washington University in St. Louis institutional review board approved the present study (IRB# 201013031).

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical data were summarized by standard descriptive statistics. Group differences between post-treatment tracheostomy or gastrostomy tube dependence were evaluated by Chi-squared tests or Fischer’s Exact test when cell sizes were smaller than 5 patients. Separate analyses were performed for each primary outcome. Univariate logistic regressions were performed to determine associations between pre-treatment risk factors and functional outcomes. Significant risk factors and known confounders were included in multivariable logistic regressions to estimate the odds ratio and strength of association between pre-treatment risk factors and laryngopharyngeal functional outcomes.

Time-to-event analysis with Kaplan-Meier survival curves was performed to evaluate overall survival in patients with advanced laryngeal SCC treated with radiation-based CRT. After testing for the proportional hazards assumption, a Cox proportional hazard model was performed for univariate and multivariable survival analysis to identify risk factors that affect overall survival. All analyses were performed in SPSS (Version 28.0, IBM, New York, USA). The effect size and 95% confidence intervals were reported to indicate the clinical magnitude and precision of the findings.

Results:

Data were extracted and analyzed defining a cohort of 75 patients with Stage III or IV laryngeal SCC that underwent definitive radiation-based therapy (Table 1). The median length of follow up was 31 months (range = 1 to 142 months). There were 54 males (72%). Seventy-four (99%) patients had a smoking history and 34 (45%) patients had moderate-severe comorbidities according to the ACE-27 comorbidity index. Treatment was radiation therapy (RT) alone in 13 (17%) patients, CCRT in 25 (33%) patients, and induction chemotherapy followed by CCRT in 37 (49%) patients. Fourteen (19%) patients presented with T4 disease (all T4a), which is generally considered a contraindication for definitive non-surgical therapy. This subset of patients was presented at multidisciplinary tumor board and offered surgical therapy, but elected to pursue CRT despite counseling on differences in oncologic outcomes. Pre-treatment dysphagia, weight loss, hoarseness, impaired true vocal fold mobility, subglottic extension was present in 43 (57%), 19 (25%), 63 (84%), 36 (48%) and 9 (12%) patients, respectively. Pre-treatment tracheostomy dependence was present in 26 (35%) patients and gastrostomy tube dependence in 18 (24%) patients.

Table 1.

Demographic and pre-treatment characteristics of functional outcomes after primary radiation-based therapy.

| Post-Treatment Tracheostomy Dependence/Permanent Stoma | Post-Treatment Gastrostomy Tube Dependence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 45) | Yes (n = 30) | Difference (95% CI) | No (n = 44) | Yes (n = 31) | Difference (95% CI) | ||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Mean Age, years (SD) | 60 (12) | 56 (9) | −3.5 (−1.5 to 8.5) | 57 (11) | 60 (11) | 3.6 (−1.6 to 8.9) | |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 33 (73%) | 19 (63%) | −10% (−32 to 12%) | 31 (71%) | 21 (68%) | −3% (−24 to 19%) | |

| Non-white | 12 (27%) | 11 (37%) | 10% (−12 to 32%) | 13 (29%) | 10 (32%) | 3% (−19 to 24%) | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 35 (78%) | 19 (63%) | −15% (−36 to 7%) | 29 (66%) | 25 (81%) | 15% (−5 to 35%) | |

| Female | 10 (22%) | 11 (37%) | 15% (−7 to 36%) | 15 (34%) | 6 (19%) | −15% (−35 to 5%) | |

| ACE-27 | |||||||

| 0-1 | 27 (60%) | 14 (47%) | −13% (−36 to 10%) | 29 (66%) | 12 (39%) | −27% (−49 to −5%) | |

| 2-3 | 18 (40%) | 16 (53%) | 13% (−10 to 36%) | 15 (34%) | 19 (61%) | 27% (5 to 49%) | |

| Smoking Status | |||||||

| Never or Former | 17 (38%) | 5 (17%) | −21% (−41 to −2%) | 15 (34%) | 7 (23%) | −11% (−32 to 9%) | |

| Current | 28 (62%) | 25 (83%) | 21% (2 to 41%) | 29 (66%) | 24 (77%) | 11% (−9 to 32%) | |

| Pretreatment Characteristics | |||||||

| T Stage | |||||||

| II or III | 35 (78%) | 26 (87%) | 9% (−8 to 26%) | 39 (89%) | 22 (71%) | −18% (−36 to 1%) | |

| IV | 10 (22%) | 4 (13%) | −9% (−26 to 8%) | 5 (11%) | 9 (29%) | 18% (−1 to 36%) | |

| Overall Stage | |||||||

| III | 21 (47%) | 21 (70%) | 23% (1 to 45%) | 26 (59%) | 16 (52%) | −7% (−30 to 15%) | |

| IV | 24 (53%) | 9 (30%) | −23% (−45 to −1%) | 18 (41%) | 15 (48%) | 7% (−15 to 30%) | |

| Subglottic Extension | |||||||

| No | 39 (87%) | 27 (90%) | 3% (−11 to 18%) | 41 (93%) | 25 (81%) | −12% (−28 to 3%) | |

| Yes | 6 (13%) | 3 (10%) | −3 (−18 to 11%) | 3 (7%) | 6 (19%) | 12% (−3 to 28%) | |

| Dysphagia | |||||||

| No | 19 (42%) | 13 (43%) | 1% (−22 to 24%) | 19 (43%) | 13 (42%) | −1% (−24 to 22%) | |

| Yes | 26 (58%) | 17 (57%) | −1% (−24 to 22%) | 25 (57%) | 18 (58%) | 1% (−22 to 24%) | |

| Weight loss | |||||||

| No | 38 (84%) | 18 (60%) | −24% (−45 to −4%) | 37 (84%) | 19 (61%) | −23% (−43 to −3%) | |

| Yes | 7 (16%) | 12 (40%) | 24% (4 to 45%) | 7 (16%) | 12 (39%) | 23 (3 to 43%) | |

| Hoarseness | |||||||

| No | 6 (13%) | 6 (20%) | 7% (−11 to 24%) | 7 (16%) | 5 (16%) | 0% (−17 to 17%) | |

| Yes | 39 (87%) | 24 (80%) | −7% (−24 to 11%) | 37 (84%) | 26 (84%) | 0% (−17 to 17%) | |

| Impaired VF Mobility | |||||||

| No | 25 (56%) | 14 (47%) | −9% (−32 to 14%) | 26 (59%) | 13 (42%) | −17% (−40 to 6%) | |

| Yes | 20 (44%) | 16 (53%) | 9% (−14 to 32%) | 18 (41%) | 18 (58%) | 16 (−6 to 40%) | |

| Pre-Treatment Tracheostomy | |||||||

| No | 39 (87%) | 10 (33%) | −54% (−73 to −34%) | 35 (80%) | 14 (45%) | −35% (−56 to −13%) | |

| Yes | 6 (13%) | 20 (67%) | 54% (34 to 73%) | 9 (20%) | 17 (55%) | 35% (13 to 56%) | |

| Pre-Treatment Gastrostomy | |||||||

| No | 38 (84%) | 19 (63%) | −21% (−41 to −1%) | 39 (89%) | 18 (58%) | −31% (−50 to −11%) | |

| Yes | 7 (16%) | 11 (37%) | 21% (1 to 41%) | 5 (11%) | 13 (42%) | 31% (11 to 50%) | |

| Treatment Regimen | |||||||

| Radiation Therapy | 7 (16%) | 6 (20%) | 4% (−13 to 22%) | 6 (14%) | 7 (23%) | 9% (−9 to 27%) | |

| CCRT | 14 (31%) | 11 (37%) | 6% (−16 to 28%) | 15 (34%) | 10 (32%) | −2% (−23 to 20%) | |

| Induction + CCRT | 24 (53%) | 13 (43%) | −10% (−33 to 13%) | 23 (52%) | 14 (45%) | −7% (−30 to 16%) | |

CI = confidence interval

SD = standard deviation

ACE-27 = adult comorbidity evaluation – 27

TV = true vocal fold

RT = radiation therapy

CCRT = concurrent chemoradiation therapy

Functional Outcomes

At last follow-up, tracheostomy or permanent stoma was present in 30 patients (40%; n = 30/75) overall (Table 1). In patients without a pre-treatment tracheostomy, 10 (20%; n = 10/49) required post-treatment tracheostomy or permanent stoma. In patients with a pre-treatment tracheostomy, 20 (77%; n = 20/26) still required post-treatment tracheostomy or permanent stoma. On univariate logistic analysis, the odds of requiring a post-treatment tracheostomy were: 13.0 times higher in patients with a pre-treatment tracheostomy compared to those without one (95% CI = 4.13 to 40.9), 3.14 times higher in patients with a pre-treatment gastrostomy compared to those without one (95% CI = 1.05 to 9.40), and 3.62 times higher in patients with clinically documented weight loss compared to those without weight loss (95% CI = 1.22 to 10.7). Smoking status and overall stage demonstrated group differences in tracheostomy dependence at last follow up (Table 1), but these risk factors did not reach statistical significance on univariate analysis (OR = 3.04, 95% CI = 0.98 to 9.43; OR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.14 to 1.01, respectively). No other pre-treatment variables, including T stage, were significantly associated with post-treatment tracheostomy dependence or permanent stoma (OR = 0.54, 95% CI = 0.15 to 1.91, respectively). Multivariable logistic regression analyses identified pre-treatment tracheostomy as the only significant predictor of long-term tracheostomy dependence (aOR = 13.9, 95% CI = 3.35 to 57.5; Table 2) when controlling for confounding variables.

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression model of pre-treatment factors affecting post-radiation tracheostomy or permanent stoma dependence.

| Risk Factor | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Weight Loss | |

| No | -ref- |

| Yes | 2.28 (0.51 to 10.2) |

| T Stage | |

| II or III | -ref- |

| IV | 0.32 (0.06 to 1.78) |

| Gastrostomy | |

| No | -ref- |

| Yes | 0.60 (0.11 to 3.23) |

| Tracheostomy | |

| No | -ref- |

| Yes | 13.9 (3.35 to 57.5) |

CI = confidence interval

As a surrogate for pharyngeal dysfunction, gastrostomy tube dependence was present in 31 patients (41%; Table 1) at last follow up. In patients without a pre-treatment gastrostomy, 18 (32%; n = 18/57) required post-treatment gastrostomy. Among patients with a pre-treatment gastrostomy, 13 (72%; n = 13/18) still required post-treatment gastrostomy. On univariate logistic analysis, the odds of requiring a post-treatment gastrostomy were: 4.72 times higher among patients with a pre-treatment tracheostomy compared to those without one (95% CI = 1.71 to 13.1), 5.63 times higher among patients with a pre-treatment gastrostomy compared to those without one (95% CI = 1.74 to 18.2), 3.34 times higher among patients with clinically documented weight loss (95% CI = 1.13 to 9.87), and 3.06 times higher among patients with moderate-severe comorbidities compared to those with none-mild comorbidities (95% CI = 1.18 to 7.95). Multivariable logistic regression analyses identified moderate-severe comorbidity as the only significant pre-treatment predictor of long-term gastrostomy dependence (aOR = 2.96, 95% CI = 1.04 to 8.43; Table 3). When controlling for confounding variables, pre-treatment gastrostomy and pre-treatment tracheostomy were not associated with post-treatment gastrostomy dependence (aOR = 2.69, 95% CI = 0.62 to 11.6; aOR 2.68, 95% CI 0.81 to 8.86, respectively; Table 3). However, their effect sizes suggest that poor pre-treatment functional status may be clinically relevant risk factors for gastrostomy dependence.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression model of pre-treatment factors affecting post-radiation gastrostomy dependence.

| Risk Factor | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| ACE-27 | |

| 0 or 1 | -ref- |

| 2 or 3 | 2.96 (1.04 to 8.43) |

| Weight Loss | |

| No | -ref- |

| Yes | 1.50 (0.38 to 5.87) |

| Tracheostomy | |

| No | -ref- |

| Yes | 2.68 (0.81 to 8.86) |

| Gastrostomy | |

| No | -ref- |

| Yes | 2.69 (0.62 to 11.6) |

CI = confidence interval

ACE-27 = adult comorbidity evaluation – 27

Survival Outcome

Among 75 patients included for overall survival analysis, 40 patients (53%; n = 40/75) were deceased at last follow up. Twenty-five (33%; n = 25/75) patients died from disease, 13 (17%; n = 13/75) patients from non-primary-disease, and 2 (3%; n = 2/75) patients from unknown causes. The five-year overall survival rate was 51% (95% CI = 38 to 64%; Figure 1). The median overall survival was 64 months (95% CI = 35 to 93 months; Figure 1). Univariate Cox proportional hazard analyses demonstrated that patients with pretreatment gastrostomy were at 2.37 times greater risk of death compared to patients without pretreatment gastrostomy (95% CI = 1.21 to 4.64). Patients treated with CCRT and induction followed by CCRT were associated with decreased risk of death compared to patients treated with radiation therapy alone (HR = 0.30, 95% CI = 0.12 to 0.75; HR = 0.37, 95% CI = 0.16 to 0.83, respectively). Presence of pre-treatment tracheostomy was not associated with risk of death (HR = 1.32, 95% CI 0.70 to 2.51). Multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis demonstrated that patients with pre-treatment gastrostomy tube dependence had an increased risk of death compared to patients without gastrostomy tube dependence (aHR = 2.45, 95% CI = 1.09 to 5.53; Table 4) and patients treated with CCRT and induction followed by CCRT had a decreased risk of death compared to patients treated with definitive radiation therapy (aHR 0.29, 95% CI = 0.11 to 0.75; aHR 0.43, 95% CI = 0.18 to 1.04, respectively; Table 4). Further exploration of the 13 patients treated with definitive radiation therapy revealed that these patients sought non-surgical intervention and had comorbidities that prevented concurrent chemotherapy, likely representing a sicker cohort than those treated with multimodal therapy. Moderate-severe comorbidity status also demonstrated a strong effect on increased risk of death (aHR = 1.46, 95% CI = 0.77 to 2.79; Table 4), which was not statistically significant but likely clinically meaningful. Pre-treatment tracheostomy was not associated with risk of death when adjusting for confounding variables (aHR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.76; Table 4).

Figure 1.

Effect of pre-treatment gastrostomy on overall survival in patients with advanced laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards model of pre-treatment factors affecting risk of death.

| Risk Factor | Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| ACE-27 | |

| 0 to 1 | -ref- |

| 2 to 3 | 1.46 (0.77 to 2.79) |

| Overall Stage | |

| III | -ref- |

| IV | 1.45 (0.76 to 2.78) |

| Treatment | |

| RT Alone | -ref- |

| CCRT | 0.29 (0.11 to 0.75) |

| Induction + CCRT | 0.43 (0.18 to 1.04) |

| Gastrostomy | |

| No | -ref- |

| Yes | 2.45 (1.09 to 5.53) |

| Tracheostomy | |

| No | -ref- |

| Yes | 0.81 (0.37 to 1.76) |

CI = confidence interval

ACE-27 = adult comorbidity evaluation – 27

RT = radiation therapy

CCRT = concurrent chemoradiation therapy

Discussion:

Over the past two decades, advanced laryngeal carcinoma is the only head and neck cancer subsite that has experienced a decline in rates of survival10,11,18,19. Although the reasons for this trend are unknown, some postulate that the reduction in overall survival is secondary to the paradigm shift towards primary treatment with organ preservation strategies instead of upfront total laryngectomy20. Maintaining a functional laryngopharynx is an important goal to strive for in every treatment plan, but studies have suggested that appropriate patient selection is key for achieving organ preservation21–25. Understanding pre-treatment risk factors associated with a dysfunctional larynx is important to maximize benefit in patients with a high likelihood of organ preservation and limit unnecessary toxicities from definitive CRT in patients with a low likelihood of organ preservation. Our study demonstrates that baseline functional status of the laryngopharynx, indicated by pre-treatment tracheostomy or gastrostomy tube dependence, is the most significant predictor of a dysfunctional organ after radiation-based therapy. Among patients with impaired laryngopharyngeal dysfunction prior to treatment, organ preservation may not be successful and should be considered during patient counseling when discussing surgical versus non-surgical treatment plans.

The decision to pursue surgical versus non-surgical management in patients with laryngeal SCC is complicated and begins with the landmark VA Laryngeal Trial and follow up RTOG 91-11 study1,2. These trials randomized patients with laryngeal cancer to receive either surgery with adjuvant radiation or induction chemotherapy with definitive radiation. They demonstrated that overall survival rates were not significantly different and that more than two-thirds of patients in the non-surgical cohort achieved organ preservation. One caveat is that patients with cancers extending beyond the thyroid cartilage and those invading the base of tongue were excluded from RTOG 91-111. These excluded cancers correspond to T4a cancers in the most recent American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Eighth Edition Cancer Staging Manual, limiting the generalizability of their findings among patients with advanced laryngopharyngeal SCC26. Another consideration is that organ preservation referred to the absence of a total laryngectomy, not necessarily a functional larynx, so patients with tracheostomy and gastrostomy tube dependence did not satisfy their primary end point. Nonetheless, management of laryngeal SCC has shifted away from primary total laryngectomy and towards CRT to attempt organ preservation, even among patients with a high burden of disease. Certainly, in patients with T3 disease the standard-of-care in the United States would typically be a non-surgical approach; however, these prior data and limitations in these studies and the definition of their endpoints raise important questions worthy of thoughtful reconsideration.

Our finding that baseline laryngopharyngeal dysfunction correlates with post-treatment laryngopharyngeal dysfunction is consistent with the previous literature. Prior studies have demonstrated that patients treated with radiation-based strategies may initially avoid total laryngectomy, but nearly 50% of patients require tracheostomy at last follow up due to impaired breathing and/or airway protection25. More advanced T stage is likely associated with pre-treatment tracheostomy and post-treatment function because of greater local destruction and extension into the larynx. However, our analysis demonstrated that pre-treatment tracheostomy was still a strong predictor of laryngopharyngeal dysfunction when controlling for overall tumor size. For gastrostomy tube dependence, moderate-severe comorbidity was a significant pre-treatment risk factor identified in our predictive model, corresponding with univariate analysis reported in previous studies in head and neck cancer patients27. Weight loss, pre-treatment tracheostomy, and pre-treatment gastrostomy have also been implicated as risk factors for long-term gastrostomy tube dependence, but these models do not consider comorbidity in their analyses28–30. These risk factors were significant on univariate analysis in our study as well. However, their significances were largely explained by poor overall health on multivariable analysis, highlighting the importance of considering comorbidity in patient counseling. Nonetheless, pre-treatment tracheostomy and pre-treatment gastrostomy demonstrated clinically relevant effect sizes for post-treatment gastrostomy tube dependence in our predictive model (Table 3). When viewed within the context of existing literature, these findings expand upon the notion that the presence of pre-treatment tracheostomy and gastrostomy are independent risk factors for severe laryngopharyngeal impairment after radiation-based organ preservation strategies and that comorbidity burden should always be considered when counseling and treating cancer patients. More broadly speaking, we feel these results reinforce our own clinical experience which emphasizes the overriding principle that chemoradiation for laryngeal cancers rarely improves a patient’s function – instead, patients should expect the same or worsened function compared to baseline.

When controlling for confounding variables, pre-treatment gastrostomy tube dependence was associated with increased risk of death. Previous studies in patients with early and advanced laryngeal cancer have reported that pre-treatment tracheostomy dependence is also an independent risk factor for decreased overall survival, as this likely corresponds to a greater extension of disease and worse laryngeal function7,25. This was not observed in our study, possibly because our patient cohort was restricted to advanced stages of laryngeal SCC only. Nonetheless, the five-year overall survival rate was comparable to those reported in other studies of patients with advanced laryngeal SCC treated with radiation-based therapies2,25,31,32. Further investigations comparing long-term functional outcomes after laryngopharyngeal treatment must be performed to further elucidate the pre-treatment risk factors associated with surgical and non-surgical management.

The results of our study should be considered within the limitations of a retrospective study design. Our study was unable to determine whether pre-treatment tracheostomies were placed prophylactically or in response to patient decompensation. Therefore, the relationship between indication of pre-treatment tracheostomy and decannulation at last follow up remains unknown. Pre-emptive indications for tracheostomy include airway compromise from bulky disease, and pre-emptive indications for gastrostomy include impaired swallow function resulting in aspiration pneumonia or failure to thrive. These indications are likely collinear with advanced T stage as larger tumors should result in worse laryngopharyngeal dysfunction at baseline. However, practice at our institution is not to prophylactically place tracheostomy or gastrostomy tubes prior to CRT, minimizing bias from this potential confounder. Furthermore, our primary outcomes captured end-organ dysfunction that required intervention, and our study was unable to assess the patient experience in less severe laryngopharyngeal impairment. Although tracheostomy and gastrostomy tube dependence indicate poor functional status, patient-reported quality of life measures related to laryngopharyngeal dysfunction, like intelligible speech, would have provided greater insight to potential benefits of larynx-preserving treatment among patients with a high likelihood of post-treatment dysfunction. Another consideration is that our study spans over two decades and that our findings may not be representative of advances in both surgical and non-surgical treatment of advanced laryngeal SCC31.

Conclusion:

Tracheostomy, gastrostomy tube dependence, and advanced comorbidity prior to radiation-based therapy predict post-treatment laryngopharyngeal dysfunction in patients with advanced laryngeal SCC. These findings suggest that patients with poor functional status and overall health at baseline are less likely to achieve organ preservation. This should be considered when counseling patients on surgical and non-surgical management of advanced laryngeal SCC.

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) within the National Institutes of Health (NIH), through the “Development of Clinician/Researchers in Academic ENT” training grant, award number T32DC000022. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Level of Evidence: Level 3

References:

- 1.Forastiere AA, Zhang Q, Weber RS, et al. Long-term results of RTOG 91-11: A comparison of three nonsurgical treatment strategies to preserve the larynx in patients with locally advanced larynx cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(7). doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Induction Chemotherapy plus Radiation Compared with Surgery plus Radiation in Patients with Advanced Laryngeal Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;324(24). doi: 10.1056/nejm199106133242402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fung K, Lyden TH, Lee J, et al. Voice and swallowing outcomes of an organ-preservation trial for advanced laryngeal cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2005;63(5). doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muttath G, Vinin NV, Shringarpure K, et al. Late toxicities among laryngopharyngeal cancers patients treated with different schedules of concurrent chemoradiation at a rural tertiary cancer care center. South Asian Journal of Cancer. 2019;08(04). doi: 10.4103/sajc.sajc_289_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Givens DJ, Karnell LH, Gupta AK, et al. Adverse events associated with concurrent chemoradiation therapy in patients with head and neck cancer. Archives of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2009;135(12). doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Machtay M, Moughan J, Trotti A, et al. Factors associated with severe late toxicity after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer: An RTOG analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(21). doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anschuetz L, Shelan M, Dematté M, Schubert AD, Giger R, Elicin O. Long-term functional outcome after laryngeal cancer treatment. Radiation Oncology. 2019;14(1). doi: 10.1186/s13014-019-1299-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theunissen EAR, Timmermans AJ, Zuur CL, et al. Total laryngectomy for a dysfunctional larynx after (chemo)radiotherapy. Archives of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2012;138(6). doi: 10.1001/archoto.2012.862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan CB, Ostedgaard KL, Al-Qurayshi Z, Pagedar NA, Sperry SM. Primary Laryngectomy Versus Salvage Laryngectomy: A Comparison of Outcomes in the Chemoradiation Era. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(9). doi: 10.1002/lary.28343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dziegielewski PT, O’Connell DA, Klein M, et al. Primary total laryngectomy versus organ preservation for T3/T4A laryngeal cancer: A population-based analysis of survival. Journal of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2012;41(SUPPL. 1). doi: 10.2310/7070.2011.110081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Megwalu UC, Sikora AG. Survival outcomes in advanced laryngeal cancer. JAMA Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2014;140(9). doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baijens LWJ, Walshe M, Aaltonen LM, et al. European white paper: oropharyngeal dysphagia in head and neck cancer. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2021;278(2). doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06507-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthew JM, Mukherji A, Saxena SK, et al. Change in dysphagia and laryngeal function after radical radiotherapy in laryngo pharyngeal malignancies — a prospective observational study. Reports of Practical Oncology and Radiotherapy. 2021;26(5). doi: 10.5603/rpOr.a2021.0078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huh G, Ahn SH, Suk JG, et al. Severe late dysphagia after multimodal treatment of stage III/IV laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019;50(2). doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyz158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutcheson KA, Barringer DA, Rosenthal DI, May AH, Roberts DB, Lewin JS. Swallowing outcomes after radiotherapy for laryngeal carcinoma. Archives of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2008;134(2). doi: 10.1001/archoto.2007.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granell J, Garrido L, Millas T, Gutierrez-Fonseca R. Management of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Laryngeal and Hypopharyngeal Cancer. International Journal of Otolaryngology. 2012;2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/157630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piccirillo JF, Zequeira MR, Creech C, Anderson S. The inclusion of comorbidity in oncology data registries. In: Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. Vol 51. ; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carvalho AL, Nishimoto IN, Califano JA, Kowalski LP. Trends in incidence and prognosis for head and neck cancer in the United States: A site-specific analysis of the SEER database. International Journal of Cancer. 2005;114(5). doi: 10.1002/ijc.20740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li MM, Zhao S, Eskander A, et al. Stage Migration and Survival Trends in Laryngeal Cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2021;28(12). doi: 10.1245/s10434-021-10318-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffman HT, Porter K, Karnell LH, et al. Laryngeal cancer in the United States: Changes in demographics, patterns of care, and survival. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(9 SUPPL. 2). doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000236095.97947.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu MP, Goldsmith T, Holman A, et al. Risk Factors for Laryngectomy for Dysfunctional Larynx After Organ Preservation Protocols: A Case-Control Analysis. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery (United States). 2021;164(3). doi: 10.1177/0194599820947702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tennant PA, Cash E, Bumpous JM, Potts KL. Persistent tracheostomy after primary chemoradiation for advanced laryngeal or hypopharyngeal cancer. In: Head and Neck. Vol 36. ; 2014. doi: 10.1002/hed.23508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacKenzie R, Franssen E, Balogh J, Birt D, Gilbert R. The prognostic significance of tracheostomy in carcinoma of the larynx treated with radiotherapy and surgery for salvage. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 1998;41(1). doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00030-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanabria A, Chaves ALF, Kowalski LP, et al. Organ preservation with chemoradiation in advanced laryngeal cancer: The problem of generalizing results from randomized controlled trials. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2017;44(1). doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byrd SA, Xu MJ, Cass LM, et al. Oncologic and functional outcomes of pretreatment tracheotomy in advanced laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma: A multi-institutional analysis. Oral Oncology. 2018;78. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, et al. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2017;67(2). doi: 10.3322/caac.21388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanchford H, Hamilton D, Bowe I, et al. Factors affecting duration of gastrostomy tube retention in survivors following treatment for head and neck cancer. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 2014;128(3). doi: 10.1017/S0022215113002582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng SS, Terrell JE, Bradford CR, et al. Variables associated with feeding tube placement in head and neck cancer. Archives of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2006;132(6). doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.6.655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Setton J, Lee NY, Huang S, et al. A Multi-institution Pooled Analysis of G-Tube Dependence in Patients With Oropharyngeal Cancer Treated With Definitive IMRT. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2013;87(2). doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.06.363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mays AC, Moustafa F, Worley M, Waltonen JD, D’Agostino R. A model for predicting gastrostomy tube placement in patients undergoing surgery for upper aerodigestive tract lesions. In: JAMA Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. Vol 140. ; 2014. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.2360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuller C, Mohamed ASR, Garden ASG, et al. Long-Term Outcomes Following Multi-Disciplinary Management of T3 Larynx Squamous Cell Carcinomas: Modern Therapeutic Approaches Improve Functional Outcomes and Survival. Head Neck. 2016;38(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fong PY, Tan SH, Lim DWT, et al. Association of clinical factors with survival outcomes in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC). PLoS ONE. 2019;14(11). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]