Introduction

In the routine evaluation of the thyroid, imaging is often a useful modality, which gives anatomical and functional characteristics that can aid diagnosis. Thyroid ultrasonography is the principal imaging modality in this regard, whereas CT, MRI and PET scanning are much less frequently ordered for thyroid assessment through thyroid lesions are often discovered via such advanced imaging modalities as incidental findings.1 Unlike radiologists, most physicians tend to be unfamiliar with radiological features of thyroid disorders detected via these latter forms of scanning.2

Case description

A 25-year-old woman who was otherwise overtly healthy and asymptomatic without any history of medical illnesses or chronic medications had volunteered for a research study on brown fat. She underwent whole-body 18F-FDG PET/MR imaging according to a standard protocol. This unexpectedly revealed abnormally increased FDG uptake (SUVmax=6.84) over the anterior neck strangely reminiscent of typical radionuclide (99m Tc or 131I) thyroid scans of hyperthyroidism (figure 1A,B). What is the diagnosis, and how would you confirm it?

Figure 1.

18F-FDG-PET scans showing diffusely increased radionuclide uptake by the thyroid gland as shown in the coronal section (A) and the sagittal section (B).

Answer: A prescan screening thyroid function test revealed a serum-free thyroxine (FT4) of 10.0 pmol/L (RI: 8–20) and serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) of 4.28 mIU/L (RI: 0.45–4.50). An invaluable clue came from a thyroid function test performed 7 months earlier: FT4=13.2 pmol/L (RI: 8–20) and TSH=2.43 (RI: 0.45–4.50). This implied a progressive decline in FT4 associated with a reciprocal increase in TSH. Thyroid ultrasonography was done next, which revealed a general heterogeneous echotexture with parenchymal hypoechogenicity consistent with thyroiditis (figure 2). Corroborating the ultrasound scan, the nonenhanced T2-weighted MR images that were simultaneously acquired during the PET-MRI fusion scan revealed high and inhomogeneous signal intensities within the thyroid parenchyma suggestive of a diagnosis of Hashimoto thyroiditis (figure 3). Serum antithyroid peroxidase autoantibody exceeded 1000 IU/mL (normal <50 IU/mL), while serum antithyroglobulin autoantibody was 33.55 IU/mL (normal <4.1 IU/mL). Despite the relatively ‘normal’ thyroid function tests, the evidence was supportive of an actively evolving thyroid autoimmunity consistent with early Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Short ACTH stimulation test excluded concomitant hypocortisolism, a crucial step to avoid precipitating addisonian crisis during L-thyroxine initiation in those with unsuspected adrenalitis from autoimmune polyglandular syndrome. She was prescribed L-thyroxine at 25 μg/day. The dose was doubled 2 years later, which optimised her energy level and body weight. At a 4-year follow-up visit, she remained euthyroid with serum FT4 of 12.5 pmol/L (RI: 8–16), FT3 of 4.7 pmol/L (RI: 3.5–6.0) and TSH of 1.54 mIU/L (RI: 0.45–4.50).

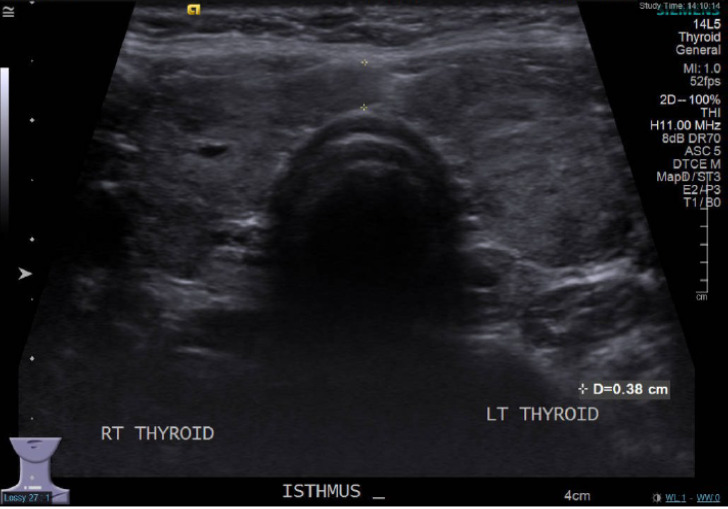

Figure 2.

Thyroid ultrasound scan revealing a gland with heterogeneous echotexture with diffuse hypo-echogenicity in bilateral lobes consistent with thyroiditis.

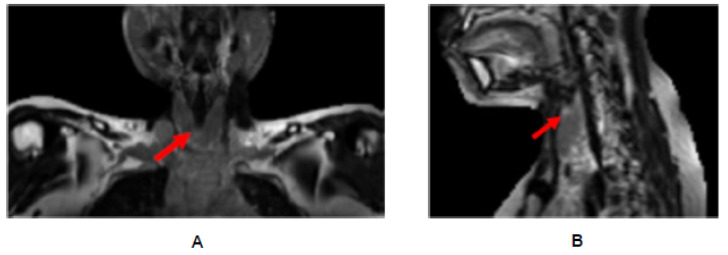

Figure 3.

MRI of thyroid of the same patient, showing non-enhanced T2-weighted coronal (A) and sagittal (B) images with inhomogeneous high signal intensities within the thyroid parenchyma supportive of Hashimoto thyroiditis.

Conclusion

The rising prevalence of autoimmune thyroiditis coupled with an increasing use of 18F-FDG-PET scanning for various indications will continue to generate such incidental findings as highlighted by our case.3 4 Although diffusely increased 18F-FDG thyroid uptake is observed in hyperthyroidism such as Graves’ disease, physicians should recognise that diffusely increased 18F-FDG thyroid uptake can also be due to Hashimoto thyroiditis,5 which contrasts starkly with diminished 99mTc/131I uptake typical of subacute thyroiditis6 and that must be differentiated from analogous scintigraphic features of Graves’ disease characterised by diffusely accentuated 99mTc/131I and 18F-FDG uptake.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the listed authors contributed to the manuscript preparation. LS wrote the first draft of the manuscript and submitted the manuscript. LS, HJG, SKV and SSV collected the data. NXW contributed the data and assisted with the editing of the manuscript. ML was the overall principal investigator and physician scientist in charge who analysed and interpreted the data, managed the patient and contributed to the writing, editing and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Funding: The study was funded by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council (NMRC) Clinician Scientist Award (grant ID NMRC/CSA-INV/0003/2015) awarded to MKSL.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1. Farrá JC, Picado O, Liu S, et al. Clinically significant cancer rates in incidentally discovered thyroid nodules by routine imaging. J Surg Res 2017;219:341–6. 10.1016/j.jss.2017.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Soto GD, Halperin I, Squarcia M, et al. Update in thyroid imaging. The expanding world of thyroid imaging and its translation to clinical practice. Hormones 2010;9:287–98. 10.14310/horm.2002.1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agrawal K, Weaver J, Ngu R, et al. Clinical significance of patterns of incidental thyroid uptake at (18)F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Radiol 2015;70:536–43. 10.1016/j.crad.2014.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Agrawal K, Weaver J, Ul-Hassan F, et al. Incidence and Significance of Incidental Focal Thyroid Uptake on (18)F-FDG PET Study in a Large Patient Cohort: Retrospective Single-Centre Experience in the United Kingdom. Eur Thyroid J 2015;4:115–22. 10.1159/000431319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nakamoto Y, Tatsumi M, Hammoud D, et al. Normal FDG distribution patterns in the head and neck: PET/CT evaluation. Radiology 2005;234:879–85. 10.1148/radiol.2343030301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Intenzo CM, dePapp AE, Jabbour S, et al. Scintigraphic manifestations of thyrotoxicosis. Radiographics 2003;23:857–69. 10.1148/rg.234025716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]