Abstract

Background

Blood pressure (BP) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) are important risk factors for cardiovascular (CV) diseases. Although treating these factors simultaneously is recommended by current guidelines, only short-term clinical results are available.

Objectives

To examine the longer-term efficacy and safety of fixed-dose combination (FDC) versus free combination of amlodipine and atorvastatin in patients with concomitant hypertension and hypercholesterolemia.

Methods

Patients with hypertension and hypercholesterolemia were stratified into three groups [FDC of amlodipine 5 mg/atorvastatin 10 mg (Fixed 5/10), FDC of amlodipine 5 mg/atorvastatin 20 mg (Fixed 5/20), and free combination of amlodipine 5 mg/atorvastatin 10 mg (Free 5/10)]. After inverse probability of treatment weighting, the composite CV outcome, liver function, BP, LDL-C and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) changes were compared.

Results

A total of 1,788 patients were eligible for analysis, and the mean follow-up period was 1.7 year. There was no significant difference in the composite CV outcome among the three groups (Fixed 5/10 6.1%, Fixed 5/20 6.3% and Free 5/10 6.0%). The LDL-C level was significantly reduced in the Fixed 5/20 group (-35.7 mg/dL) compared to the Fixed 5/10 (-23.6 mg/dL) and Free 5/10 (-10.3 mg/dL) groups (p = 0.001 and < 0.001, respectively). The changes in HbA1c were similar among the three groups.

Conclusions

FDC of amlodipine and atorvastatin, especially the regimen with a higher dosage of statins, significantly reduced the mid-term LDL-C level compared to a free combination in patients with concomitant hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. Blood sugar level was not significantly changed by this aggressive treatment strategy.

Keywords: Fixed-dose combination, Glycated hemoglobin, Hypercholesterolemia, Hypertension, Long term outcome

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension and hypercholesterolemia are two important modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD). They have been reported to coexist in up to 30% of patients with CVD,1,2 and their synergistic effect on cardiovascular mortality is greater than each condition alone.3 Therefore, current clinical guidelines recommended treating these risk factors simultaneously rather than in isolation.4,5 However, the increased pill burden when prescribing antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapy concomitantly may have a negative impact on drug adherence,6 which may then attenuate the beneficial effects of the simultaneous treatment strategy.

Fixed-dose combination (FDC) is widely used in several chronic diseases including hypertension, diabetes mellitus and pulmonary tuberculosis. Compared to free combination, FDC simplifies the treatment regimen, reduces healthcare costs, and improves both drug compliance and clinical outcomes.7-12 Relatively few studies have compared the efficacy, adherence and interaction be-tween FDC and free combination strategies in patients with two different diseases, such as hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. Among these studies, the follow-up periods ranged from only 6 weeks to 6 months.13-22 In our previous work, we demonstrated improved clinical outcomes with the use of FDC of amlodipine and atorvastatin in patients with concomitant hypertension and dyslipidemia compared to a free-equivalent combination (FEC), including major adverse cardiovascular events, hospitalization for coronary artery disease and newly initiating hemodialysis.23 However, these results were generated from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of Taiwan, which is a large administrative database that does not contain personal data such as smoking, body weight, blood pressure (BP) records or laboratory data. Therefore, the efficacy of lowering BP and cholesterol, and the safety profiles such as blood sugar, renal and liver function could not be estimated.

In the present study, we aimed to analyze the long-term efficacy and safety of FDC versus free combination of amlodipine and atorvastatin in patients with concomitant hypertension and hypercholesterolemia registered in a real-world, multi-institutional, electronic medical record (EMR) database.

METHODS

Data source

The data used in this study were retrospectively obtained from the Chang Gung Research Database (CGRD), which is a multi-institutional, de-identified standardized EMR database maintained by the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CGMH) organization, and also the largest such database in Taiwan.24,25 The CGMH organization is currently the largest medical system in Taiwan, comprising two medical centers, two regional hospitals and three district hospitals, with a total of 10,070 beds, more than 280,000 admissions, 8,500,000 outpatient visits and 500,000 emergency department visits a year.25

The CGRD contains more clinical details than administrative claims databases, including pathological reports, laboratory results, procedure reports, smoking habit, vital sign records and body mass index (BMI). Diseases were recorded using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes before 2016, and ICD-10-CM codes thereafter. The research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board of CGMH, Linkou, Taiwan (committee’s approval number: 202100 864B0), and the need for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective design of the study and anonymized clinical data.

Study cohort and design

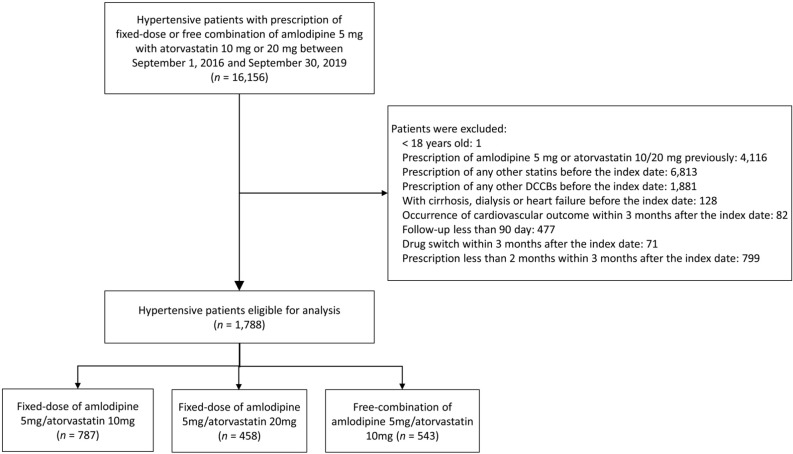

We identified patients diagnosed with hypertension in the CGRD from September 1, 2016 to September 30, 2019 who had prescriptions of FDC or free combinations of amlodipine with atorvastatin (Figure 1). The only available dosages of amlodipine/atorvastatin FDC in Taiwan are amlodipine 5 mg with atorvastatin 10 or 20 mg, and both dosages of FDC were available at CGMH from September 2016. To avoid potential confounding of previously prescribed medications, we only included patients with a first prescription of either FDC or free combination of amlodipine and atorvastatin. The date of the first prescription of the studied medication was defined as the index date.

Figure 1.

Study design and flow chart of the inclusion and exclusion of the patients. DCCBs, dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers.

Patients who received any form of dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers or statins before the index date were excluded from this study. To evaluate the long-term efficacy, we excluded patients who developed cardiovascular (CV) outcomes within 3 months after the index date or whose follow-up period was less than 90 days. To ascertain the long-term use of the studied drugs, we also excluded patients who switched drugs or received the treatment medication for less than 60 days within 3 months after the index date. Other exclusion criteria were an age less than 18 years, a diagnosis of liver cirrhosis, those undergoing dialysis, and those with heart failure before the index date. After exclusion, three study cohorts were generated. The first cohort consisted of patients who received FDC of amlodipine 5 mg and atorvastatin 10 mg (Fixed 5/10 group), the second received FDC of amlodipine 5 mg and atorvastatin 20 mg (Fixed 5/20 group), and the third received free combination of amlodipine 5 mg plus atorvastatin 10 mg (Free 5/10 group). The use of FDC or free combination treat-ment or the indication of these drugs were at the physician’s discretion. The baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes of these three cohorts were compared.

Covariates

Covariates were obtained from the CGRD including age, sex, BMI, smoking status, CVD (including coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, acute coronary syndrome or stroke), comorbidities, Charlson’s Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, concomitant medications, vital signs (office BP and heart rate) and laboratory data. Comorbidities included diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, malignancy and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The presence of CVD and comorbidities was confirmed if the patients had at least one inpatient or two outpatient diagnoses before the index date. Concomitant medications included antiplatelet agents, anti-hypertensive agents other than DCCBs [angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), beta-blockers, diuretics and other anti-hypertensive agents such as nitrates and vasodilators] and anti-diabetic drugs [glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2is), insulin and other oral anti-diabetic drugs]. Laboratory data included low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), non-HDL-C, total cholesterol, triglycerides, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C), fasting glucose, serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), serum uric acid, urine albumin/creatinine ratio, alanine amino transferase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST). Concomitant medications, BMI, vital signs and laboratory data were extracted from the EMRs within 3 months before or after the index date.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was composite CV outcome, including all-cause death, coronary intervention, acute myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke. Coronary interventions were identified by inpatient procedure codes of percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary arterial bypass grafting. Acute MI was defined as having a principal inpatient diagnosis of MI with an elevated cardiac troponin level above the 99th percentile upper reference limit during hospitalization. Stroke was defined as having a principal inpatient diagnosis and an image (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) showing stroke. Information on deaths was obtained from the sub-database of death certificates in the CGRD.

The secondary outcomes were renal, safety and laboratory/BP outcomes. The renal outcomes included a decline in eGFR of more than 40%, newly initiating dialysis, the composite of both outcomes, and all-cause death. The safety outcomes included new-onset diabetes mellitus (NODM) and abnormal liver function. NODM was identified as having newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus and an HbA1c level greater than 6.5% during follow-up. Abnormal liver function was defined as an elevation in ALT level of more than three times the upper reference limit, namely greater than 105 U/L. Laboratory outcomes were long-term LDL-C and HbA1c levels during follow-up.

Medication adherence was assessed by using the proportion of days covered (PDC) according to the EMRs, which was defined as the total number of days covered by the study drugs divided by the total number of follow-up days.7,9,13,23,26 The follow-up period started from the index date of the first prescription of the study drug until the date of an outcome, death, the date of switching among the study drugs, the last visit date in the CGRD, or the end of the study period (September 30, 2019), whichever occurred first.

Statistical analyses

The distribution of baseline characteristics among the three study groups (Fixed 5/10 vs. Fixed 5/20 vs. Free 5/10) was balanced by using generalized boosted modeling-inverse probability of treatment weighting (GBM-IPTW) based on propensity scores with 10,000 trees.27 The propensity scores were calculated based on all of the baseline characteristics, except that the follow-up year was replaced with the index date. Baseline characteristic data that were missing were imputed using a single expectation-maximization algorithm before conducting GBM-IPTW. The balance among the three study groups before and after GBM-IPTW was assessed by using the maximum absolute standardized difference (MASD), and an MASD less than 0.2 was considered to indicate good balance among the groups.27

The risk of fatal outcomes (i.e., all-cause death, composite CV outcome) among the three study groups was compared using a Cox proportional hazard model. The incidence of non-fatal outcomes (i.e., decline in renal function) among the three study groups was compared using a Fine and Gray sub-distribution hazards model, which considered all-cause death during follow-up as a competing risk. The study groups were the only explanatory variables in the aforementioned survival analyses. A subgroup analysis of primary CV outcomes was further stratified by prior CVD. Changes in laboratory data and BP from baseline to long-term follow-up among the three study groups were compared using a generalized estimating equation which contained the intercept, main effects of the study groups and time (treated as a continuous variable) and an interaction effect of the study groups by time. Changes between groups were considered to be significantly different when the interaction was statistically significant.

A two-sided p value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), including the "PHREG" procedure for conducting the survival analysis and the "TWANG" macro for estimating GBM-IPTW.27

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

A total of 16,156 hypertensive patients with prescriptions of the studied drugs were identified in the CGRD during the study period. After exclusion, 1,788 patients were eligible for further analyses, including 787 patients in the Fixed 5/10 group, 458 patients in the Fixed 5/20 group, and 543 patients in the Free 5/10 group (Figure 1). The mean age of all patients was 60 ± 12.2 years, and 53.9% were male. The baseline HbA1c level was 7.56 ± 1.73% in the patients with diabetes and 6.06 ± 0.84% in the patients without diabetes.

Medication adherence rates assessed by PDC after IPTW were 59.0 ± 35.4% in the Fixed 5/10 group, 63.3 ± 39.4% in the Fixed 5/20 group and 58.0 ± 46.2% in the Free 5/10 group, which were not significantly different (MASD 0.124). The number of concomitant anti-hypertensive agents during the study period was significantly higher in the Fixed 5/20 group (2.12 ± 1.06 in the Fixed 5/10 group, 2.33 ± 1.21 in the Fixed 5/20 group and 2.19 ± 1.09 in the Free 5/10 group, p < 0.001). Compared to the patients in the other two groups, those in the Free 5/10 group were older, had lower BMI, higher prevalence of stroke and higher CCI score (MASD > 0.2; Table 1). Regarding the baseline concomitant medications, patients in the Free 5/10 group received more anti-platelet agents but fewer SGLT2is (MASD 0.272 and 0.238, respectively) than those in the other two groups, whereas the Fixed 5/20 group received more ARBs (43.9%, MASD 0.277). Both baseline systolic and diastolic BP were significantly higher in the Fixed 5/20 group than in the other groups. The Fixed 5/20 group also had higher LDL-C, non-HDL-C, total cholesterol and ALT levels.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study patients.

| Variable | Available numbers | All (n = 1,788) | Fixed 5/10 (n = 787) | Fixed 5/20 (n = 458) | Free 5/10 (n = 543) | MASD |

| Age, years | 1,788 | 64.0 ± 12.2 | 63.4 ± 11.9 | 62.3 ± 12.4 | 66.4 ± 12.0 | 0.232 |

| Male | 1,788 | 963 (53.9) | 424 (53.9) | 249 (54.4) | 290 (53.4) | 0.037 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 1,375 | 26.5 ± 3.8 | 26.6 ± 3.8 | 27.1 ± 4.1 | 26.0 ± 3.5 | 0.248 |

| Smoking | 1,788 | 251 (14.0) | 99 (12.6) | 68 (14.8) | 84 (15.5) | 0.078 |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 1,788 | 274 (15.3) | 115 (14.6) | 87 (19.0) | 72 (13.3) | 0.136 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 1,788 | 80 (4.5) | 39 (5.0) | 10 (2.2) | 31 (5.7) | 0.147 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 1,788 | 35 (2.0) | 7 (0.89) | 12 (2.6) | 16 (2.9) | 0.107 |

| Stroke | 1,788 | 400 (22.4) | 142 (18.0) | 65 (14.2) | 193 (35.5) | 0.490 |

| Any cardiovascular disease | 1,788 | 674 (37.7) | 264 (33.5) | 147 (32.1) | 263 (48.4) | 0.318 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1,788 | 700 (39.1) | 323 (41.0) | 168 (36.7) | 209 (38.5) | 0.101 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1,788 | 350 (19.6) | 158 (20.1) | 81 (17.7) | 111 (20.4) | 0.074 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1,788 | 75 (4.2) | 28 (3.6) | 22 (4.8) | 25 (4.6) | 0.114 |

| Malignancy | 1,788 | 388 (21.7) | 186 (23.6) | 100 (21.8) | 102 (18.8) | 0.079 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1,788 | 118 (6.6) | 55 (7.0) | 28 (6.1) | 35 (6.4) | 0.022 |

| Charlson’s Comorbidity Index score | 1,788 | 2.1 ± 2.1 | 2.1 ± 2.1 | 1.8 ± 2.0 | 2.5 ± 2.2 | 0.308 |

| Medication | ||||||

| Antiplatelet agents | 1,788 | 741 (41.4) | 295 (37.5) | 163 (35.6) | 283 (52.1) | 0.272 |

| ACEi | 1,788 | 64 (3.6) | 28 (3.6) | 19 (4.1) | 17 (3.1) | 0.039 |

| ARBs | 1,788 | 624 (34.9) | 235 (29.9) | 201 (43.9) | 188 (34.6) | 0.277 |

| Beta-blockers | 1,788 | 541 (30.3) | 232 (29.5) | 154 (33.6) | 155 (28.5) | 0.117 |

| Diuretics | 1,788 | 152 (8.5) | 61 (7.8) | 40 (8.7) | 51 (9.4) | 0.098 |

| Other anti-hypertensive agents | 1,788 | 182 (10.2) | 65 (8.3) | 54 (11.8) | 63 (11.6) | 0.113 |

| GLP-1 RA | 1,788 | 8 (0.45) | 2 (0.25) | 3 (0.66) | 3 (0.55) | 0.051 |

| SGLT2i | 1,788 | 77 (4.3) | 31 (3.9) | 36 (7.9) | 10 (1.8) | 0.238 |

| Other oral hypoglycemic agents | 1,788 | 275 (15.4) | 119 (15.1) | 60 (13.1) | 96 (17.7) | 0.166 |

| Insulin | 1,788 | 83 (4.6) | 33 (4.2) | 19 (4.1) | 31 (5.7) | 0.111 |

| Vital signs at baseline | ||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 1,717 | 145.8 ± 21.4 | 146.2 ± 21.6 | 149.0 ± 22.4 | 142.5 ± 19.6 | 0.286 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 1,717 | 82.2 ± 13.2 | 82.8 ± 13.4 | 83.7 ± 13.2 | 79.9 ± 12.5 | 0.223 |

| Heart rate, beat/min | 1,707 | 80.3 ± 13.3 | 79.8 ± 13.3 | 81.0 ± 13.9 | 80.5 ± 12.7 | 0.051 |

| Laboratory data at baseline | ||||||

| LDL, mg/dL | 1,737 | 118.6 ± 49.0 | 115.1 ± 46.8 | 128.2 ± 52.9 | 115.6 ± 47.7 | 0.235 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 1,716 | 47.7 ± 13.3 | 48.0 ± 12.9 | 47.8 ± 13.5 | 47.2 ± 13.5 | 0.034 |

| Non-HDL, mg/dL | 1,634 | 142.4 ± 50.0 | 138.5 ± 41.7 | 151.7 ± 66.9 | 140.2 ± 43.0 | 0.213 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 1,741 | 191.3 ± 51.4 | 187.3 ± 43.1 | 202.4 ± 67.7 | 187.8 ± 44.9 | 0.236 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 1,734 | 127 [89, 176] | 128 [85, 174] | 138 [97, 190] | 120 [88, 166] | 0.168 |

| HbA1C, % | 1,625 | 6.7 ± 1.5 | 6.7 ± 1.5 | 6.7 ± 1.5 | 6.7 ± 1.6 | 0.019 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 1,612 | 116.9 ± 40.9 | 118.4 ± 41.5 | 118.7 ± 45.6 | 113.3 ± 35.3 | 0.090 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1,778 | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 1.4 | 0.103 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 1,778 | 81.2 ± 30.8 | 83.0 ± 30.5 | 79.5 ± 27.6 | 79.8 ± 33.5 | 0.096 |

| Serum uric acid, mg/dL | 1,587 | 6.0 ± 1.6 | 5.9 ± 1.6 | 6.1 ± 1.6 | 5.9 ± 1.7 | 0.075 |

| Urine ACR | 724 | 64 [6, 331] | 42 [6, 289] | 80 [7, 388] | 87 [3, 348] | 0.053 |

| ALT, U/L | 1,744 | 22 [16, 32] | 22 [16, 31] | 24 [17, 37] | 21 [16, 29] | 0.201 |

| AST, U/L | 1,426 | 25 [21, 32] | 26 [21, 32] | 25 [20, 31] | 25 [21, 31] | 0.066 |

| Follow up year | 1,788 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 0.232 |

ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ACR, albumin/creatinine ratio; ALT, alanine amino transferase; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; AST, aspartate transaminase; eGFR, estimated Glomerular filtration rate; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; HbA1C, glycated hemoglobin; HDL, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; HTN, hypertension; LDL, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; MASD, maximum absolute standardized difference; Non-HDL, non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor.

Data were presented as frequency (percentage), median [25th, 75th percentile] or mean ± standard deviation.

After imputation and GBM-IPTW, all covariates at baseline were well-balanced with no significant differences among the three study groups (all MASD values < 0.2; Supplementary Table 1). The maximum follow-up period in this study was 30 months, and the mean follow-up periods were 1.7 ± 0.9 years in the Fixed 5/10 group, 1.6 ± 0.8 years in the Fixed 5/20 group, and 1.7 ± 0.9 years in the Free 5/10 group, respectively (MASD 0.133).

Supplemental Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study cohort after imputation and GBM-IPTW.

| Variable | Fixed 5/10 | Fixed 5/20 | Free 5/10 | MASD |

| Age, years | 64.3 ± 11.9 | 63.2 ± 12.0 | 65.2 ± 11.9 | 0.063 |

| Male | 53.9 | 53.0 | 52.9 | 0.063 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.5 ± 3.7 | 26.8 ± 3.7 | 26.3 ± 3.6 | 0.080 |

| Smoking | 12.9 | 16.9 | 13.5 | 0.095 |

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||

| Coronary artery disease | 14.3 | 17.4 | 13.7 | 0.078 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 5.1 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 0.070 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 0.88 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 0.086 |

| Stroke | 20.8 | 20.7 | 26.4 | 0.133 |

| Any cardiovascular disease | 35.7 | 36.5 | 40.0 | 0.092 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 41.8 | 37.9 | 36.2 | 0.093 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 20.4 | 17.4 | 19.9 | 0.048 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3.9 | 6.3 | 3.8 | 0.100 |

| Malignancy | 23.5 | 22.9 | 18.9 | 0.079 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 7.3 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 0.027 |

| Charlson’s Comorbidity Index score | 2.1 ± 2.1 | 1.9 ± 2.1 | 2.2 ± 2.1 | 0.121 |

| Medication | ||||

| Antiplatelet agents | 39.9 | 40.1 | 45.8 | 0.097 |

| ACEi | 3.7 | 4.5 | 2.9 | 0.065 |

| ARBs | 31.6 | 38.1 | 34.9 | 0.110 |

| Beta-blockers | 29.3 | 31.8 | 28.8 | 0.075 |

| Diuretics | 8.2 | 8.9 | 9.0 | 0.062 |

| Other anti-hypertensive agents | 8.4 | 11.4 | 10.9 | 0.071 |

| GLP-1 RA | 0.21 | 0.74 | 0.50 | 0.066 |

| SGLT2i | 3.9 | 5.5 | 2.0 | 0.120 |

| Other oral hypoglycemic agents | 15.4 | 13.0 | 15.8 | 0.109 |

| Insulin | 4.5 | 3.9 | 5.4 | 0.104 |

| Vital signs at baseline | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 145.6 ± 21.4 | 147.1 ± 22.0 | 144.1 ± 19.9 | 0.104 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 82.2 ± 13.3 | 82.7 ± 13.0 | 81.0 ± 12.6 | 0.061 |

| Heart rate, beat/min | 79.9 ± 13.1 | 80.9 ± 13.4 | 80.4 ± 12.6 | 0.041 |

| Laboratory data at baseline | ||||

| LDL, mg/dL | 116.5 ± 46.4 | 121.9 ± 46.9 | 116.9 ± 47.2 | 0.068 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 47.9 ± 12.8 | 47.7 ± 13.5 | 47.7 ± 13.2 | 0.005 |

| Non-HDL, mg/dL | 140.1 ± 42.3 | 146.4 ± 56.7 | 141.3 ± 43.2 | 0.076 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 188.7 ± 43.4 | 196.3 ± 57.9 | 190.2 ± 45.5 | 0.093 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 128 [86, 173] | 133 [95, 182] | 122 [90, 171] | 0.073 |

| HbA1C, % | 6.7 ± 1.5 | 6.7 ± 1.5 | 6.6 ± 1.4 | 0.042 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 117.8 ± 40.1 | 116.9 ± 41.5 | 112.8 ± 34.5 | 0.067 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 1.3 | 0.058 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 81.3 ± 30.5 | 80.5 ± 28.6 | 80.5 ± 31.2 | 0.029 |

| Serum uric acid, mg/dL | 5.9 ± 1.6 | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 6.0 ± 1.6 | 0.019 |

| Urine ACR | 54 [7, 315] | 61 [7, 346] | 87 [5, 326] | 0.009 |

| ALT, U/L | 22 [16, 31] | 23 [16, 33] | 22 [16, 30] | 0.062 |

| AST, U/L | 26 [21, 32] | 25 [20, 31] | 26 [21, 31] | 0.060 |

| Follow up year | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 0.133 |

ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ACR, albumin/creatinine ratio; ALT, alanine amino transferase; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; AST, aspartate transaminase; eGFR, estimated Glomerular filtration rate; GBM-IPTW, generalized boosted modeling-inverse probability of treatment weighting; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; HbA1C, glycated hemoglobin; HDL, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; HTN, hypertension; LDL, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; Non-HDL, non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor.

Data were presented as frequency (percentage), median [25th, 75th percentile] or mean ± standard deviation.

Clinical outcomes

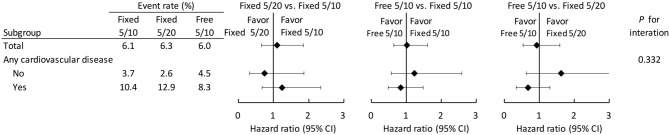

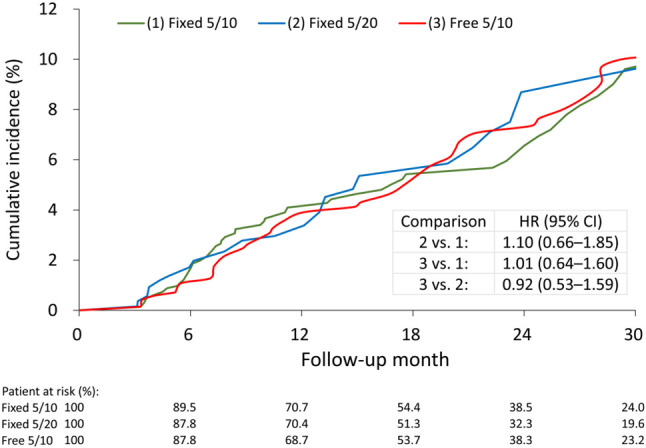

The number of events in each study group in the original cohort before GBM-IPTW is listed in Supplementary Table 2. After imputation and GBM-IPTW, the risk of clinical outcomes was compared among three study groups. The risk of composite CV outcome was not significantly different among the three groups (6.1% in the Fixed 5/10 group, 6.3% in the Fixed 5/20 group and 6.0% in the Free 5/10 group) as shown in Table 2 and Figure 2. The results showed that the risks of each component of the composite CV outcome did not differ among groups. The incidence of composite renal outcome was also comparable among the groups, including eGFR decline > 40%, newly initiating dialysis or all-cause mortality (10.4% in the Fixed 5/10 group, 11.1% in the Fixed 5/20 group and 11.5% in the Free 5/10 group). We further analyzed the composite CV outcome among the three study groups in patients with or without previously established CVD as primary and secondary prevention, which disclosed comparable results (p for interaction = 0.332) (Figure 3).

Supplemental Table 2. Follow-up outcomes of the original cohort.

| Outcome | Event (%) | |||

| All (n = 1,788) | Fixed 5/10 (n = 787) | Fixed 5/20 (n = 458) | Free 5/10 (n = 543) | |

| Cardiovascular outcome | ||||

| Coronary intervention | 18 (1.01) | 7 (0.89) | 6 (1.3) | 5 (0.92) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 7 (0.39) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.3) | 1 (0.18) |

| Stroke | 61 (3.4) | 29 (3.7) | 12 (2.6) | 20 (3.7) |

| All-cause death | 30 (1.7) | 14 (1.8) | 3 (0.66) | 13 (2.4) |

| Composite cardiovascular outcome* | 105 (5.9) | 47 (6.0) | 23 (5.0) | 35 (6.4) |

| Renal outcome | ||||

| eGFR decline > 40% | 190 (10.7) | 76 (9.7) | 45 (9.9) | 69 (12.8) |

| Dialysis | 28 (1.6) | 10 (1.3) | 5 (1.1) | 13 (2.4) |

| Composite outcome of eGFR decline > 40% or dialysis | 195 (10.9) | 78 (9.9) | 46 (10.0) | 71 (13.1) |

| Composite outcome of eGFR decline > 40% or dialysis or all-cause death | 205 (11.5) | 85 (10.8) | 47 (10.3) | 73 (13.4) |

| Safety outcome | ||||

| New-diagnosed diabetes mellitus | 121 (11.1) | 55 (11.9) | 41 (14.1) | 25 (7.5) |

| ALT > 105 U/L | 65 (3.6) | 31 (3.9) | 20 (4.4) | 14 (2.6) |

ALT, alanine amino transferase; CV, cardiovascular; eGFR, estimated Glomerular filtration rate.

* Anyone of coronary intervention, acute myocardial infarction, stroke or all-cause death.

Table 2. Follow-up outcomes of study cohort after imputation and GBM-IPTW.

| Outcome | Event rate (%) | HR or SHR (95% CI) | ||||

| Fixed 5/10 | Fixed 5/20 | Free 5/10 | Fixed 5/20 vs. Fixed 5/10 | Free 5/10 vs. Fixed 5/10 | Free 5/10 vs. Fixed 5/20 | |

| Cardiovascular outcome | ||||||

| Coronary intervention | 0.80 | 1.2 | 0.90 | 1.51 (0.75-3.04) | 1.15 (0.53-2.50) | 0.76 (0.36-1.59) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 0.00 | 1.8 | 0.12 | NA | NA | NA |

| Stroke | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 0.99 (0.69-1.41) | 0.96 (0.66-1.40) | 0.97 (0.66-1.45) |

| All-cause death | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 0.56 (0.16-1.97) | 1.06 (0.49-2.32) | 1.91 (0.54-6.80) |

| Composite cardiovascular outcome* | 6.1 | 6.3 | 6.0 | 1.10 (0.66-1.85) | 1.01 (0.64-1.60) | 0.92 (0.53-1.59) |

| Renal outcome | ||||||

| eGFR decline > 40% | 9.2 | 10.6 | 10.9 | 1.23 (0.99-1.53) | 1.23 (0.98-1.54) | 1.00 (0.79-1.25) |

| Dialysis | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.03 (0.56-1.91) | 1.49 (0.83-2.66) | 1.44 (0.78-2.66) |

| Composite outcome of eGFR decline > 40% or dialysis | 9.5 | 10.8 | 11.2 | 1.22 (0.99-1.52) | 1.23 (0.98-1.53) | 1.00 (0.80-1.26) |

| Composite outcome of eGFR decline > 40% or dialysis or all-cause death | 10.4 | 11.1 | 11.5 | 1.14 (0.78-1.65) | 1.14 (0.82-1.58) | 1.01 (0.68-1.49) |

| Safety outcome | ||||||

| New-diagnosed diabetes mellitus | 11.3 | 13.2 | 8.5 | 1.43 (1.11-1.85)* | 0.82 (0.61-1.10) | 0.57 (0.42-0.77)* |

| ALT > 105 U/L | 3.9 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 1.02 (0.72-1.46) | 0.53 (0.34-0.83)* | 0.52 (0.33-0.82)* |

ALT, alanine amino transferase; CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; eGFR, estimated Glomerular filtration rate; GBM-IPTW, generalized boosted modeling-inverse probability of treatment weighting; HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio.

* Anyone of coronary intervention, acute myocardial infarction, stroke or all-cause death.

Figure 2.

The IPTW-adjusted cumulative incidence of composite cardiovascular outcomes in the FDC of amlodipine 5 mg/atorvastatin 10 mg (green line), FDC of amlodipine 5 mg/atorvastatin 20 mg (blue line), and free combination of amlodipine 5 mg/atorvastatin 10 mg (red line) groups. The cumulative incidence was derived from Kaplan-Meier estimate. CI, confidence interval; FDC, fixed-dose combination; HR, hazard ratio; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the subgroup analysis according to the presence of preexisting cardiovascular disease in the IPTW-adjusted cohort. CI, confidence interval; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting.

The risk of NODM was significantly higher in the Fixed 5/20 group compared to the other two groups [Fixed 5/20 vs. Fixed 5/10, sub-distribution hazard ratio (SHR), 1.43; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.11 to 1.85; Free 5/10 vs. Fixed 5/20, SHR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.42 to 0.77]. The incidence of abnormal liver function was significantly lower in the Free 5/10 group than in the Fixed 5/20 group (SHR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.33 to 0.82) and the Fixed 5/10 group (SHR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.34 to 0.83; Table 2).

Laboratories and BP changes

We further evaluated the longitudinal changes of LDL-C, HbA1c and BP among the three groups. The mean levels and changes from baseline in the laboratory data and BP at different time points are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Supplemental Table 3. The mean level and change value from baseline of laboratory data and blood pressure at different time points in the GBM-IPTW cohort.

| HbA1C, % | LDL, mg/dL | SBP, mmHg | DBP, mmHg | |||||||||

| Fixed 5/10 | Fixed 5/20 | Free 5/10 | Fixed 5/10 | Fixed 5/20 | Free 5/10 | Fixed 5/10 | Fixed 5/20 | Free 5/10 | Fixed 5/10 | Fixed 5/20 | Free 5/10 | |

| Time point | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 6.74 | 6.72 | 6.62 | 116.5 | 121.9 | 116.9 | 145.6 | 147.1 | 144.1 | 82.2 | 82.7 | 81.0 |

| 6 months | 6.86 | 6.87 | 6.75 | 93.0 | 85.8 | 97.5 | 140.0 | 139.3 | 140.6 | 78.7 | 78.2 | 78.6 |

| 12 months | 6.85 | 6.85 | 6.74 | 95.1 | 84.0 | 100.0 | 141.7 | 140.1 | 139.4 | 79.9 | 79.1 | 79.1 |

| 18 months | 6.76 | 6.84 | 6.60 | 91.7 | 87.3 | 97.4 | 141.4 | 137.3 | 139.1 | 79.2 | 76.4 | 77.6 |

| 24 months | 6.68 | 6.70 | 6.61 | 93.3 | 88.1 | 99.2 | 142.7 | 139.2 | 138.8 | 79.5 | 77.2 | 77.2 |

| 30 months | 6.63 | 6.85 | 6.69 | 92.9 | 86.3 | 106.7 | 141.1 | 137.6 | 140.8 | 77.5 | 77.1 | 79.5 |

| Change value | ||||||||||||

| 6 months | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.13 | -23.5 | -36.1 | -19.5 | -5.6 | -7.7 | -3.5 | -3.4 | -4.5 | -2.4 |

| 12 months | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.13 | -21.4 | -38.0 | -17.0 | -3.9 | -6.9 | -4.7 | -2.2 | -3.6 | -1.9 |

| 18 months | 0.02 | 0.12 | -0.02 | -24.8 | -34.6 | -19.5 | -4.2 | -9.7 | -5.0 | -2.9 | -6.3 | -3.4 |

| 24 months | -0.06 | -0.02 | -0.01 | -23.2 | -33.9 | -17.8 | -2.9 | -7.9 | -5.3 | -2.7 | -5.5 | -3.8 |

| 30 months | -0.11 | 0.13 | 0.07 | -23.6 | -35.7 | -10.3 | -4.5 | -9.5 | -3.3 | -4.7 | -5.6 | -1.4 |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GBM-IPTW, generalized boosted modeling-inverse probability of treatment weighting; HbA1C, glycated hemoglobin; LDL, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

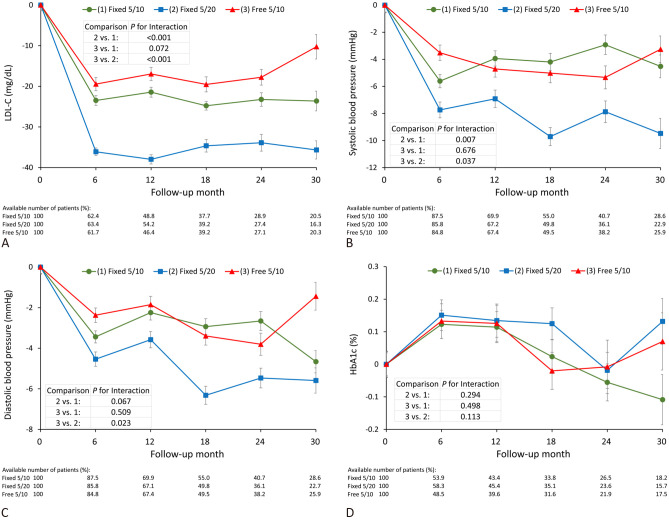

During the follow-up period, the decreases in LDL-C level were 23.6, 35.7 and 10.3 mg/dL in the Fixed 5/10, Fixed 5/20 and Free 5/10 groups, respectively. The generalized estimating equation model showed that the Fixed 5/20 group had a greater reduction in LDL-C than the Fixed 5/10 [regression coefficient (B), -2.7; 95% CI, -4.3 to -1.2; p < 0.001] and Free 5/10 (B, -4.2; 95% CI -5.8 to -2.5; p < 0.001) groups. However, there was no significant difference between the Free 5/10 and Fixed 5/10 groups (B, 1.5; 95% CI, -0.1 to 3.0; p = 0.072) (Figure 4A). In non-smoking patients, the LDL-C lowering effect was greater in the Fixed 5/20 group than in the Free 5/10 group (Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 4.

The longitudinal changes in LDL-C (A), systolic blood pressure (B), diastolic blood pressure (C) and HbA1c (D) in the FDC of amlodipine 5 mg/atorvastatin 10 mg (green line), FDC of amlodipine 5 mg/atorvastatin 20 mg (blue line), and free combination of amlodipine 5 mg/atorvastatin 10 mg (red line) groups. FDC, fixed-dose combination; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Supplemental Table 4. The change of low-density lipoprotein from baseline to 6th month in the GBM-IPTW cohort.

| Subgroup | Change from baseline, mg/dL | p for interaction | ||||

| (1) Fixed 5/10 | (2) Fixed 5/20 | (3) Free 5/10 | 2 vs. 1 | 3 vs. 1 | 3 vs. 2 | |

| Smoking | 0.520 | 0.123 | 0.046 | |||

| No | -26.1 ± 76.9 | -39.5 ± 83.2 | -20.8 ± 109.5 | |||

| Yes | -27.3 ± 65.0 | -33.6 ± 70.9 | -39.5 ± 65.6 | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.519 | 0.281 | 0.692 | |||

| < 27 | -27.8 ± 78.0 | -38.3 ± 82.2 | -20.3 ± 115.2 | |||

| ≥ 27 | -23.7 ± 71.2 | -38.7 ± 80.9 | -27.0 ± 83.6 | |||

| Baseline SBP, mmHg | 0.927 | 0.401 | 0.408 | |||

| < 140 | -20.5 ± 72.9 | -32.9 ± 80.9 | -21.0 ± 104.5 | |||

| ≥ 140 | -29.7 ± 76.5 | -41.8 ± 81.4 | -23.9 ± 105.6 |

BMI, body mass index; GBM-IPTW, generalized boosted modeling-inverse probability of treatment weighting; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation.

The reductions in systolic BP were 4.5, 9.5 and 3.3 in the Fixed 5/10, Fixed 5/20 and Free 5/10 groups, respectively, and the Fixed 5/20 group had a significantly greater reduction than the Fixed 5/10 (B, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.3 to 1.6; P = 0.007) and Free 5/10 (B, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.1 to 1.5; p = 0.037) groups (Figure 4B). The reductions in diastolic BP were 4.7, 5.6 and 1.4 in the Fixed 5/10, Fixed 5/20 and Free 5/10 groups, respectively. The Fixed 5/20 group had a borderline significantly greater reduction than the Fixed 5/10 group (B, 0.4; 95% CI, -0.03 to 0.78; p = 0.067). In addition, there was a significant difference between the Free 5/10 and Fixed 5/20 groups (B, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.07 to 0.96; p = 0.023) (Figure 4C). In the patients with a BMI less than 27 kg/m2, the reductions in systolic and diastolic BP were greater in the Fixed 5/20 group than in the other two groups (Supplementary Table 5 and 6). We also evaluated HbA1c changes among the three groups, however no significant effects were observed (Figure 4D).

Supplemental Table 5. The change of systolic blood pressure from baseline to 6th month in the GBM-IPTW cohort.

| Subgroup | Change from baseline, mmHg | p for interaction | ||||

| (1) Fixed 5/10 | (2) Fixed 5/20 | (3) Free 5/10 | 2 vs. 1 | 3 vs. 1 | 3 vs. 2 | |

| Smoking | 0.928 | 0.460 | 0.559 | |||

| No | -5.3 ± 34.3 | -8.3 ± 42.2 | -4.0 ± 36.8 | |||

| Yes | -2.8 ± 37.5 | -8.1 ± 47.5 | -3.8 ± 33.5 | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.046 | 0.793 | 0.041 | |||

| < 27 | -2.6 ± 34.7 | -7.7 ± 45.1 | -1.2 ± 32.3 | |||

| ≥ 27 | -9.2 ± 34.0 | -8.9 ± 40.5 | -9.1 ± 42.1 | |||

| Baseline SBP, mmHg | 0.579 | 0.523 | 0.973 | |||

| < 140 | 8.2 ± 30.3 | 6.4 ± 34.0 | 10.2 ± 28.6 | |||

| ≥ 140 | -14.1 ± 31.0 | -16.8 ± 39.8 | -14.1 ± 33.4 |

BMI, body mass index; GBM-IPTW, generalized boosted modeling-inverse probability of treatment weighting; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Supplemental Table 6. The change of diastolic blood pressure from baseline to 6th month in the GBM-IPTW cohort.

| Subgroup | Change from baseline, mmHg | p for interaction | ||||

| (1) Fixed 5/10 | (2) Fixed 5/20 | (3) Free 5/10 | 2 vs. 1 | 3 vs. 1 | 3 vs. 2 | |

| Smoking | 0.617 | 0.047 | 0.185 | |||

| No | -3.5 ± 19.5 | -4.8 ± 22.9 | -2.2 ± 21.6 | |||

| Yes | -1.1 ± 20.8 | -5.2 ± 31.7 | -4.3 ± 20.5 | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.063 | 0.520 | 0.023 | |||

| < 27 | -1.9 ± 19.6 | -4.6 ± 23.7 | -0.8 ± 19.4 | |||

| ≥ 27 | -5.4 ± 19.4 | -5.2 ± 25.2 | -5.6 ± 24.3 | |||

| Baseline SBP, mmHg | 0.627 | 0.947 | 0.694 | |||

| < 140 | 2.8 ± 18.1 | 0.6 ± 23.4 | 3.7 ± 16.3 | |||

| ≥ 140 | -7.3 ± 18.4 | -8.1 ± 23.1 | -6.9 ± 22.4 |

BMI, body mass index; GBM-IPTW, generalized boosted modeling-inverse probability of treatment weighting; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

This multi-institutional retrospective study is the first study to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of FDC versus free combination of amlodipine and atorvastatin in patients with concomitant hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. During the 30-month follow-up period, we found no significant difference in the composite CV outcome among the three study groups. FDC of amlodipine 5 mg and atorvastatin 20 mg resulted in a greater reduction in LDL-C than the other two regimens, however the HbA1c level was not significantly different. The LDL-C lowering effect was not statistically different between the Fixed 5/10 and Free 5/10 groups.

In our previous study, we demonstrated that FDC regimen of amlodipine and atorvastatin improved composite CV outcomes compared to FEC of the same medications in patients with newly diagnosed hypertension and dyslipidemia during a 5-year follow-up period.23 In that study, the medication adherence as assessed by PDC was better in the FDC than in the FEC group (0.49 ± 0.26 vs. 0.32 ± 0.3, p < 0.001), and this may explain the results. However, based on the nature of the large administrative NHIRD, the major limitations of the study were a lack of possible confounding variables and efficacy parameters including BP and LDL-C changes. In the current study, we analyzed the efficacy and safety of FDC of amlodipine and atorvastatin by using data from the CGRD, a real-world, multi-institutional, standardized EMR database. Previous studies have reported that drug compliance with FDC is always better than free combination, which is the main explanation for the beneficial clinical effects of FDC.7,9-11,13,14,23 However, the medication adherence as assessed by PDC in the current study was not significantly different among the three study groups, which may be related to the stricter study criteria compared to previous studies in that we excluded patients who switched drugs or received the study medications for less than 2 months within 3 months after the index date. Subsequently, the remaining patients, especially those in the free combination group, may have had better drug compliance and tolerability which may explain the comparable medication adherence between the FDC and free combination groups in the present study. Moreover, the follow-up period and number of patients were relatively limited, and this may have further resulted in the similar composite CV outcome among the three study groups.

In the present study, both systolic and diastolic BP were significantly lower in the Fixed 5/20 group than in the other two groups with similar medication adherence, which may be because the Fixed 5/20 group used the highest number of concomitant anti-hypertensive drugs. In previous studies, different dosages of FDC amlodipine/atorvastatin have been administered and titrated to improve BP and lipid control.16,20-22 The JEWEL program, which included JEWEL 1 conducted in the United Kingdom and Canada and JEWEL 2 conducted in European countries, was an international open-label study which assessed the efficacy and safety of FDC amlodipine/atorvastatin in attaining BP and lipid targets recommended by country-specific guidelines.16 Eight dosages of amlodipine/atorvastatin (5/10 to 10/80 mg) were titrated, and 62.9% of the patients in JEWEL 1 and 50.6% of the patients in JEWEL 2 achieved both country-specific BP and LDL-C goals. At the end of the study, the average dosages were 7.3/26.8 mg in JEWEL 1 and 6.7/24.1 mg in JEWEL 2 during a 16-week follow-up period. Similarly, the Gemini and Gemini-AALA studies were also open-label studies conducted in the United States and internationally (Australia, Asia, Latin America, Africa/Middle East), respectively, to evaluate the achievement of BP and lipid goals by titrating different dosages of amlodipine/atorvastatin FDC.20,21 After 14 weeks, 57.7% of the patients in Gemini and 55.2% of the patients in Gemini-AALA had achieved both their BP and LDL-C goals. The mean dosages at the end point were 7.1/26.2 mg and 7.1/19.7 mg, respectively. In African Americans, Flack et al. reported that different dosages of amlodipine/atorvastatin FDC in addition to lifestyle modification improved the attainment of BP and cholesterol goals.22 After a 20-week follow-up period, 48.3% of the patients reached both their BP and LDL-C goals, and the mean received dose of amlodipine/atorvastatin was 8.2/26.4 mg at the final visit. In the current study, the patients in the Fixed 5/20 group had a significantly lower LDL-C level than those in the lower dose Fixed 5/10 and Free 5/10 groups, and the amlodipine/atorvastatin 5/20 dosage was closer to the mean dosages of the aforementioned studies, which may explain the better attainment of both BP and lipid goals in our patients. Interestingly, even under the titration design of the aforementioned studies, approximately half of the patients were started on the lowest amlodipine 5 mg/atorvastatin 10 mg FDC dosage, and about 30-60% of these patients were not up-titrated. Current guidelines recommend that the initial dosage of statins should be of moderate intensity,28-30 and it is thus reasonable to first prescribe or early up-titrate to Fixed 5/20 rather than Fixed 5/10 or Free 5/10 in order to achieve better BP and LDL-C control concomitantly. The LDL-C levels were significantly reduced in the first 6 months in all groups. This effect was sustained during the follow-up period, and the beneficial effect of a greater reduction in LDL-C with a higher dose of statins was maintained. In patients with a high CV risk, the outcomes may be further improved by using this aggressive treatment strategy.

The risk of NODM with statin therapy has been shown to be positively correlated with the strength of the statins,31 with a reported overall risk of 9%.32 In the current study, we also found that the risk of NODM was highest in the Fixed 5/20 group and lowest in the Free 5/10 group, and this may be explained by the different strengths of the statins. However, there were no significant differences among the three study groups with regards to HbA1c level during follow-up. The reason for this discrepancy may be multifactorial, such as the different diagnostic criteria for diabetes among physicians, not routinely checking HbA1c level in all patients or by chance. On the other hand, statin-associated liver toxicity is well established, however there are very few reports of liver failure directly attributed to statins.33,34 In the current study, we also found an increased risk of ALT elevation in the higher strength statin (Fixed 5/20) group. However, it should be emphasized that the beneficial effects of statins on CVD outweigh the risk of NODM development or mild liver function abnormalities, and therefore adequate dosages of statin should be prescribed if indicated to improve CV outcomes. Myopathy, myalgia and fatigue are also possible adverse effects of statin but it was not routinely examined or reported in our database.

Adequate BP and LDL-C control are recommended by clinical guidelines both in primary and secondary CVD prevention.29,35,36 In our previous study, we only demonstrated the beneficial effect of reducing major adverse cardiovascular events with FDC of amlodipine/ atorvastatin in the primary prevention setting.23 In the present study, we further analyzed the differences in efficacy among three study groups with regards to primary and secondary CVD prevention, and the results were comparable in composite CV outcome. The major adverse cardiovascular event rates were not significantly different among the three study groups both in primary and secondary prevention, which may be due to relatively homogenous drug compliance among the groups, shorter follow-up period, different population and study design.

This study was based on a multi-institutional standardized EMR database and has several limitations. First, although the CGRD is the largest EMR database in Taiwan and covers almost 10% of the entire population, we could not collect the clinical events that developed in hospitals that were not involved in the CGRD, which may have led to underestimation of the actual event rates. Meanwhile, we used IPTW to balance the confounding medications but any additional drugs from other institutes could not be obtained. However, this should be balanced among the three study groups, and the between-group comparisons should still be reasonable. Second, the BP values used in the present analysis were based on office BP records, which may not represented home BP and ambulatory BP monitoring. Therefore, we could not rule out the possibility of white-coat or masked hypertension. Third, we used PDC as a surrogate marker of medication adherence but we could not ensure that the patients consumed the medications accordingly, and therefore drug compliance may have been overestimated. Finally, this is a retrospective, non-randomized study, and the results may be confounded by other unmeasured factors. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution.

CONCLUSIONS

In this retrospective, EMR-based study, FDC of amlodipine and atorvastatin, especially the regimen with a higher dosage of statins, significantly reduced the mid-term LDL-C level compared to free combination in patients with concomitant hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. HbA1c control during the follow-up period was not compromised by this aggressive treatment strategy, and it should be particularly considered in patients with high CV risk to improve clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Alfred Hsing-Fen Lin for his statistical analysis during the completion of this article. This research was supported by grants 109-2314-B-182A-155 from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asmar R, Vol S, Pannier B, et al. High blood pressure and associated cardiovascular risk factors in France. J Hypertens. 2001;19:1727–1732. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson ML, Pietz K, Battleman DS, Beyth RJ. Prevalence of comorbid hypertension and dyslipidemia and associated cardiovascular disease. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:926–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas F, Bean K, Guize L, et al. Combined effects of systolic blood pressure and serum cholesterol on cardiovascular mortality in young (< 55 years) men and women. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:528–535. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:e127–e248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021–3104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman RH, Benner JS, Petrilla AA, et al. Predictors of adherence with antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1147–1152. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.10.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tung YC, Lin YS, Wu LS, et al. Clinical outcomes and healthcare costs in hypertensive patients treated with a fixed-dose combination of amlodipine/valsartan. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2015;17:51–58. doi: 10.1111/jch.12449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lima GC, Silva EV, Magalhaes PO, Naves JS. Efficacy and safety of a four-drug fixed-dose combination regimen versus separate drugs for treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Microbiol. 2017;48:198–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verma AA, Khuu W, Tadrous M, et al. Fixed-dose combination antihypertensive medications, adherence, and clinical outcomes: a population-based retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simons LA, Chung E, Ortiz M. Long-term persistence with single-pill, fixed-dose combination therapy versus two pills of amlodipine and perindopril for hypertension: Australian experience. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33:1783–1787. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1367275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris SB. The power of two: an update on fixed-dose combinations for type 2 diabetes. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9:1453–1462. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2016.1221758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JH, Lee YH, Ko SK, Cha BS. Cost-effectiveness analysis of low density lipoprotein cholesterol-lowering therapy in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes in Korea: single-pill regimen (amlodipine/atorvastatin) versus double-pill regimen (amlodipine+atorvastatin). Epidemiol Health. 2015;37:e2015010. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2015010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel BV, Leslie RS, Thiebaud P, et al. Adherence with single-pill amlodipine/atorvastatin vs a two-pill regimen. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4:673–681. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussein MA, Chapman RH, Benner JS, et al. Does a single-pill antihypertensive/lipid-lowering regimen improve adherence in US managed care enrolees? A non-randomized, observational, retrospective study. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2010;10:193–202. doi: 10.2165/11530680-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messerli FH, Bakris GL, Ferrera D, et al. Efficacy and safety of coadministered amlodipine and atorvastatin in patients with hypertension and dyslipidemia: results of the AVALON trial. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2006;8:571–581; quiz 582-573. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2006.05636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richard Hobbs FD, Gensini G, John Mancini GB, et al. International open-label studies to assess the efficacy and safety of single-pill amlodipine/atorvastatin in attaining blood pressure and lipid targets recommended by country-specific guidelines: the JEWEL programme. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16:472–480. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32832b63f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee HY, Kim SY, Choi KJ, et al. A randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and the tolerability of a triple combination of amlodipine/losartan/rosuvastatin in patients with comorbid essential hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Clin Ther. 2017;39:2366–2379. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Preston RA, Harvey P, Herfert O, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and pharmacodynamic interaction of coadministered amlodipine and atorvastatin in 1660 patients with concomitant hypertension and dyslipidemia: the respond trial. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47:1555–1569. doi: 10.1177/0091270007307879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grimm R, Malik M, Yunis C, et al. Simultaneous treatment to attain blood pressure and lipid goals and reduced CV risk burden using amlodipine/atorvastatin single-pill therapy in treated hypertensive participants in a randomized controlled trial. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2010;6:261–271. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s7710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erdine S, Ro YM, Tse HF, et al. Single-pill amlodipine/atorvastatin helps patients of diverse ethnicity attain recommended goals for blood pressure and lipids (the Gemini-AALA study). J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:196–210. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blank R, LaSalle J, Reeves R, et al. Single-pill therapy in the treatment of concomitant hypertension and dyslipidemia (the amlodipine/atorvastatin gemini study). J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2005;7:264–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2005.04533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flack JM, Victor R, Watson K, et al. Improved attainment of blood pressure and cholesterol goals using single-pill amlodipine/atorvastatin in African Americans: the CAPABLE trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:35–45. doi: 10.4065/83.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin CP, Tung YC, Hsiao FC, et al. Fixed-dose combination of amlodipine and atorvastatin improves clinical outcomes in patients with concomitant hypertension and dyslipidemia. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2020;22:1846–1853. doi: 10.1111/jch.14016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shao SC, Chan YY, Kao Yang YH, et al. The Chang Gung Research Database - a multi-institutional electronic medical records database for real-world epidemiological studies in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28:593–600. doi: 10.1002/pds.4713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai MS, Lin MH, Lee CP, et al. Chang Gung Research Database: a multi-institutional database consisting of original medical records. Biomed J. 2017;40:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care. 2005;43:521–530. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163641.86870.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCaffrey DF, Griffin BA, Almirall D, et al. A tutorial on propensity score estimation for multiple treatments using generalized boosted models. Stat Med. 2013;32:3388–3414. doi: 10.1002/sim.5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:e285–e350. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140:e596–e646. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:111–188. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preiss D, Seshasai SR, Welsh P, et al. Risk of incident diabetes with intensive-dose compared with moderate-dose statin therapy: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:2556–2564. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, et al. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet. 2010;375:735–742. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61965-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson PD, Panza G, Zaleski A, Taylor B. Statin-associated side effects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2395–2410. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Denus S, Spinler SA, Miller K, Peterson AM. Statins and liver toxicity: a meta-analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:584–591. doi: 10.1592/phco.24.6.584.34738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts). Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315–2381. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:407–477. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]