Abstract

To better understand the role of cytokines in susceptible and resistant subjects exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, intracellular gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and interleukin-4 (IL-4) in ex vivo peripheral blood-derived CD4+ T cells were examined by flow cytometry. Of the 37 individuals examined, 20 had clinical evidence of pulmonary tuberculosis and showed acid-fast bacilli in the sputum. Other individuals in close contact with these patients showed no evidence of disease. Patients had a higher number of CD4+ T cells expressing IFN-γ and IL-4 in unstimulated cultures compared to healthy subjects. Despite this, the ratio of IFN-γ+ to IL-4+ CD4+ T cells was similar in both groups. The Th1 response seen in CD4+ T cells in patients was also observed in the overall pattern of IFN-γ and IL-4 detected in control culture supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). However, after in vitro stimulation of PBMC with heat-killed M. tuberculosis there was a significant reduction in the percentage of IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells (P < 0.001) in patients. This trend was reflected in the IFN-γ ELISA assay with supernatants derived from stimulated cultures. However, the accumulated levels of IFN-γ were higher than those for IL-4. The reduction of IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells resulted in the dominance of IL-4+ CD4+ T cells in 13 patients (P < 0.05). The elevated levels of IL-4+ CD4+ T cells seen in patients may contribute to the downregulation of IFN-γ expression and the crucial effector function of CD4 T cells, leading to the persistence of disease and the immunopathology characteristically seen in patients. Preliminary data on the indicators of apoptosis in antigen-stimulated cultures in PBMC derived from patients are presented. Of the 17 high-risk healthy individuals examined, 11 differed in that, after mycobacterial-antigen stimulation, there was an enhancement in IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells.

With the advent of AIDS and multidrug resistance (MDR), tuberculosis has emerged as a disease of public health importance both in developed and developing countries, with annual associated death rate of 3 million (23, 31). The lack of the availability of an effective protective vaccine has further aggravated the situation (30). Elucidation of the immune response of immunocompetent healthy individuals after exposure to tubercle bacilli may provide strategies for effective immunotherapeutic and prophylactic regimens (43). The mode of activation of effector cells in humans is different from that of experimental models, thereby limiting the extrapolation of data (12, 13, 16, 26, 35, 46).

Cell-mediated immunity is the major component of host defense against tuberculosis. Antigen-specific T cells secrete cytokines that activate natural effector cells (6). Classically, the CD4+ T cells have been considered to play the most important role in antimycobacterial immunity (24, 40, 45).

Ever since Mosmann and Coffmann proposed the Th1 and Th2 paradigm, the study of their roles in various diseases in order to develop prophylactic vaccines and therapeutic regimens has become a major focus of immunological studies (29, 34). The degree of Th1 and Th2 polarization increases with the severity and the chronicity of the immune response (22, 33, 51). Thus, the Th0 cytokine pattern is most noticeable early after lymphocyte activation, and the clearest demonstrations of Th1 and Th2 cytokine profiles have been made in chronic disease states, in which antigens are persistent and cannot be eliminated (1).

Hence, the present study was undertaken to assess by flow cytometry the interleukin-4-positive (IL-4+) and gamma-interferon-positive (IFN-γ+) CD4+ T cells derived from the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of patients and healthy contacts following coculture with various concentrations of integral heat-killed tubercle bacilli. Our results show the preferential decrease in IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells, along with the sustained maintenance of IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells in patients. The predominance of IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells in patients may be one of the principal factors leading to an ineffective immune response against the tubercle bacilli (1).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Twenty untreated pulmonary-tuberculosis patients in an age group ranging between 22 and 50 years (X-ray and sputum acid-fast-bacillus positive) attending the outpatient clinic at the LRS Tuberculosis and Allied Diseases Hospital and the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, were included in the study. All patients were human immunodeficiency virus HIV negative. The institutional review board approved the study, and the subjects gave informed consent to participate in the study. Seventeen healthy volunteers who were closely associated with the patients were included in the study as high-risk healthy contacts. The contacts were radiologically screened for clinical signs of tuberculosis by chest X-ray and, when warranted on the basis of symptoms, additional tests such as sputum examination for acid-fast bacilli and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were undertaken. Tuberculin (1 tuberculin unit [TU]) (BCG Vaccine Laboratory, Guindy, Chennai, India) was injected intradermally into all individuals (patients and contacts) included in the study. After 48 h, an induration of ≥5 mm was considered a positive reaction. Of the 20 patients, 12 were tuberculin reactive (mean diameter of induration, 10.7 ± 1.7 mm) and 8 were negative (<5 mm). Eight contacts were tuberculin reactive (15.0 ± 2.5 mm), and 9 were nonreactive (<5 mm, CNR). Six tuberculin-negative volunteers from Europe were included in the study as nonendemic-area controls.

Cell preparation and in vitro culture.

PBMC were isolated from heparinized (GIBCO-BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) blood by density gradient centrifugation on Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO.) (5). PBMC were suspended at a concentration of 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 (GIBCO-BRL) supplemented with 20 mM HEPES (GIBCO-BRL), 2 mM glutamine (GIBCO-BRL), 0.1 mM sodium pyruvate (GIBCO-BRL), and 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum. A 100-μl portion of the PBMC suspension was distributed into 96-well round-bottom plates (Linbro) and then incubated with 20 μl of integral M. tuberculosis organisms/well (Tuberculosis Research Materials, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health). Four different concentrations of bacilli (0.005, 0.05, 0.5, and 5 × 106 bacilli/ml [M1 to M4, respectively]) were used in the study. These cultures were incubated for 40 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2–95% air atmosphere. With positive controls, cells were cultured in the presence of 1% phytohemagglutinin (PHA; GIBCO-BRL) for 24 h, followed by restimulation with PHA, phorbol myristate acetate (Sigma), and ionomycin (Sigma) for 12 h. Cultures incubated with medium alone served as negative controls.

Intracellular analysis of cytokine production in CD4+ T cells.

Intracellular cytokine staining was used to determine the cytokine expression in CD4+ T cells by flow cytometry (3, 20, 37). A total of 20 μl of brefeldin A, a potent nontoxic inhibitor of protein secretion (10 μM; Sigma) was added 4 h prior to termination of the culture. Cells were harvested and stained for the surface expression of CD4+ antigen in T cells by using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody (Becton Dickinson). After a washing with Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% fetal calf serum (DPBS-FCS; pH 7.2 to 7.4; GIBCO-BRL), the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (0.05 M, pH 7.4) for 15 min on ice. Cells were washed with DPBS–1% FCS and permeabilized with 0.2% saponin (Sigma) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-4 (2.5 μg/ml; Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) were added to separate aliquots of membrane stained and permeabilized cells and were incubated for 45 min. Cells were washed thrice with DPBS–0.2% saponin and finally with DPBS–1% FCS. Samples were acquired in a Bio-Rad flow cytometer (Bio-Rad; flow cytometer was provided courtesy The National Institute of Immunology (NII), New Delhi, India), and data were analyzed by using WIN MDI and WIN Bryte software. Control samples were incubated with irrelevant, isotype-matched monoclonal antibodies (Becton Dickinson) in parallel.

Staining specificity.

Both cold antibody competition and recombinant cytokine blocking established the staining specificity. In the former assay, an excess of nonconjugated antibody (Genzyme, Cambridge, Mass.) was allowed to react with permeabilized cells, followed by further incubation with PE-conjugated anti-cytokine antibody (anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-4 antibody), whereas in the latter experiment preincubation of a 500-fold molar excess of recombinant cytokine (GIBCO-BRL) with anti-cytokine antibody was undertaken for 1 h before it was added to the sample.

The CD4 staining was validated by the incubation of parallel cultures of PBMC with FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody and isotype control. The two-dimensional (2D) overlays of a representative European control have been included in the results.

Lymphocytes were gated based on their forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) profiles for each experiment. 2D display of FL1 versus FL2 of the gated population indicated the membrane marker, i.e., CD4 and the intracellular cytokine signals, respectively. The values of the actual percentage of cytokine-expressing cells were normalized by dividing the percentage of the dual-positive cells by the total percentage of FL1 positive cells. These normalized values have been used for the subsequent analysis and presenting the data.

ELISA for IFN-γ and IL-4.

Supernatants were collected at 48 h from cultures of PBMC stimulated with various concentrations of heat-killed M. tuberculosis bacilli (M1, M2, M3, and M4). Triplicate wells were pooled. IFN-γ and IL-4 concentrations in supernatants were assessed by use of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Genzyme) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Apoptosis (DNA fragmentation).

PBMC cultured with or without M. tuberculosis (0.005 × 106 bacilli/ml) were harvested and washed twice with PBS. The cell pellet was lysed in 400 μl of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 10 mM EDTA, pH 8.0; 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate; 0.2% Triton X-100; proteinase K at 0.1 mg/ml) at 50°C for 16 h. This was followed by incubation with 50 μg of RNase per ml for an additional hour at 68°C. DNA was extracted twice with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1 [vol/vol/vol]) and twice with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1 [vol/vol]). DNA in the aqueous phase was precipitated overnight at −20°C with twice the volume of 100% ethanol, washed with 70% ethanol, air dried, and dissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA) and subjected to electrophoresis through a 1.8% agarose gel. DNA fragments were stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical calculations were done by using MICROSTAT software. All values in text and figures have been expressed as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). Since the variables under study were not normally distributed, nonparametric statistical tests were used for data analysis. The Wilcoxon matched-pair test was used to analyze paired values in the same group, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to analyze paired values in different groups, the Friedman test was used to compare multiple values within the same group, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare multiple groups (38).

RESULTS

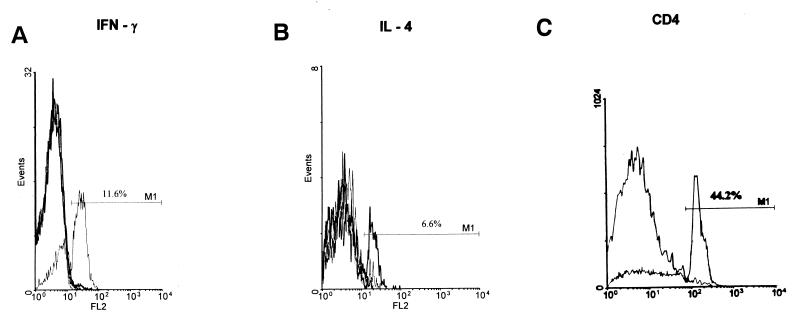

The in vitro immune response to M. tuberculosis as determined by flow cytometry was assessed in 20 pulmonary tuberculosis patients and 17 high-risk healthy subjects. PBMC isolated from these individuals were incubated with wide-ranging concentrations of heat-killed tubercle bacilli (0.005 × 106 to 5 × 106/ml) for 40 h. The cells were assessed for the intracellular presence of IL-4 and IFN-γ in CD4+ T cells. The specificity of the staining technique used for the detection of intracellular IFN-γ and IL-4 in the CD4+ subset of T cells was established by including the following controls: (i) positive control, (ii) nonspecific isotype-matched control, (iii) neutralization of IFN-γ and IL-4 staining with appropriate antibodies, and (iv) competitive inhibition of staining with recombinant IFN-γ and IL-4 (Fig. 1A and B). The 2D overlays of a representative European control establish the efficacy of the CD4 staining (44.2% CD4+ T cells; Fig. 1C). Reports of lymphopenia and absolute low CD4 numbers in HIV seronegative patients with advanced tuberculosis and pulmonary cavitation could account for the low percentage of the CD4+ population seen in patients (47). Studies reveal a lower percentage of CD4 T cells in the Indian population (4). Similarly, there have been reports in healthy adult Thais and Malaysians of low CD3 and CD4 cell numbers and the CD4/CD8 ratio appears to be significantly less than those reported in Caucasians (7, 49, 50). The low proportion of CD4 T cells seen in the subjects included in our study fall into the general observation made regarding the normal range of lymphocyte subpopulations in Asians.

FIG. 1.

(A and B) Validation of the specificity of the intracellular staining. In vitro cultures of mitogen-stimulated human PBMC were dually stained with anti-CD4+ and anti-cytokine antibody as described in Materials and Methods. The specificity of the staining was checked by preincubation of anti-cytokine antibodies with excess recombinant cytokine and blocking of the binding of fluorescence-tagged antibody with unlabelled antibody. Panels A and B show 2D overlay histograms of dually stained positive control, recombinant cytokine neutralized control, cold antibody inhibition control, and isotype control data for IFN-γ (A) and IL-4 (B). (C) Validation of the specificity of staining CD4+ T cells. Representative 2D overlays of PBMC cultures derived from a European donor stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody and isotype control.

IL-4+ or IFN-γ+ T cells were not detected in European samples in control or antigen-stimulated cultures where M. tuberculosis is not endemic and thus the data from these cultures was not considered for further analysis.

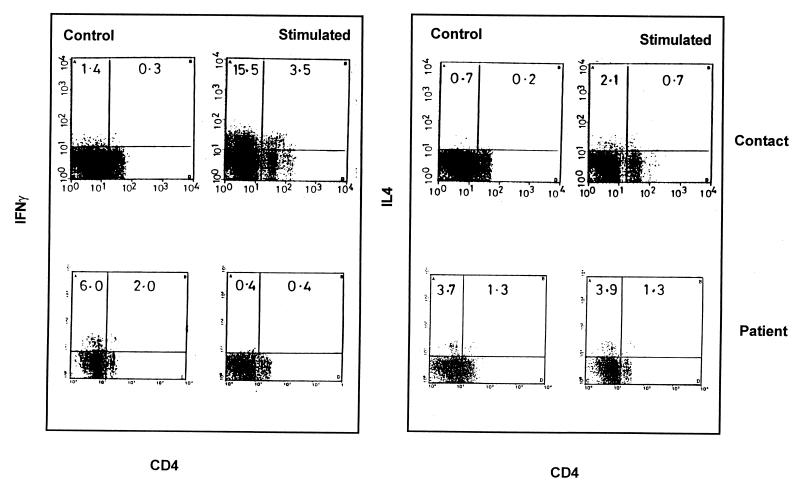

Representative dot plots of IFN-γ+ and IL-4+ CD4 T cells in patients and contacts.

Representative dot plots of CD4+ T cells showing intracellular IFN-γ and IL-4 in a healthy contact and in a tuberculosis patient are depicted in Fig. 2. The healthy contacts showed negligible levels of CD4+ T cells expressing IFN-γ and IL-4 in basal unstimulated cultures (0.3 and 0.2%, respectively). After stimulation with killed M. tuberculosis (0.005 × 106/ml; M1), selective increases in the frequency of IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells were detected (3.5%). A large number of non-CD4+ T cells (15.5%) expressing IFN-γ in healthy contacts at M1, the lowest antigen concentration, was detected. Further studies have shown this population to be a non-T-cell population, since neither CD8 nor γδ antibodies (data not shown) are able to stain it. IL-4-containing CD4+ T cells also increased from 0.2 to 0.7% with stimulation, although the frequency was lower compared to the percentage of IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells.

FIG. 2.

Representative profile of the gated populations of IFN-γ- and IL-4-expressing CD4+ T cells derived from the PBMC from one contact and one patient. Scattergrams indicating the intracellular expression of IFN-γ and IL-4 in CD4+ T cells in a contact and in a patient, as assessed by flow cytometry in control and stimulated cultures (M. tuberculosis, heat-killed, at 0.005 × 106/ml), are shown.

In contrast, in patients a decline in the percentage of IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells was detected in stimulated cultures (0.4%) compared to the control cultures (2.0%). Similar percentages of IL-4-positive cells were present in both control and stimulated cultures (1.3%).

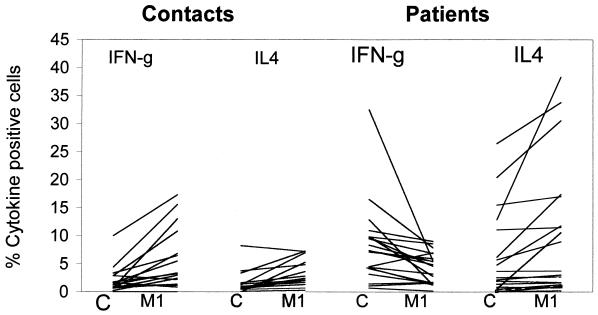

Cytokine profile in contacts and patients in control and stimulated cultures.

Figure 3 and Table 1 show the individual and mean data on the percentages of IFN-γ+ and IL-4+ CD4+ T cells of patients and contacts, respectively. In control cultures only one contact showed >5% of CD4+ T cells expressing IFN-γ and IL-4, respectively (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Overall analysis of the expression of IFN-γ and IL-4 of patients and contacts in CD4+ T cells. The percentages of CD4+ T cells expressing IFN-γ and IL-4 in all 37 individuals studied were plotted as line diagrams. Each line represents one individual. C, baseline control; M1, 0.005 × 106 M. tuberculosis bacilli/ml.

TABLE 1.

IFN-γ and IL-4 expression profile in CD4+ T cells of patients and contacts

| Subjects (n) | M. tuberculosis concn (106/ml) | % Positive CD4+ T cells (mean ± SEM) containing:

|

CD4+ T-cell ratio (IFN-γ/IL-4) | Th type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | IL-4 | ||||

| Patients (20) | Nil | 8.3 ± 0.6 | 5.9 ± 1.7 | 1.4 | Th1 |

| 0.005 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 9.9 ± 2.6 | 0.4 | Th2 | |

| 0.05 | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 10.4 ± 2.7 | 0.3 | Th2 | |

| 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 8.5 ± 1.5 | 0.2 | Th2 | |

| 5.0 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 0.2 | Th2 | |

| Contacts (17) | Nil | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.4 | Th1 |

| 0.005 | 5.6 ± 1.3 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 1.9 | Th1 ↑ | |

| 0.05 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 1.1 | Th1 | |

| 0.5 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 4.6 ± 1.1 | 0.8 | Th2 | |

| 5.0 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 0.6 | Th2 | |

Upon coculturing PBMC with tubercle bacilli (M1), 11 of the 17 healthy contacts examined showed an overall increase in the number of CD4+ T cells expressing IFN-γ (Fig. 3). The percentage of IL-4 expression was also increased in five healthy contacts. This percentage was lower than in the patients.

A shift in the baseline cytokine profile was seen upon antigen stimulation (Table 1). The stimulated cultures of contacts showed a gradual and sustained increase in IFN-γ-producing cells compared to the baseline levels. However, the predominance of the ratio of IFN-γ-containing CD4+ T cells (Th1 response) was confined to cultures stimulated with 0.005 × 106 (M1) and 0.05 × 106 (M2) bacilli/ml.

In contrast, the patients examined had higher mean percentages of IFN-γ (P < 0.001), along with IL-4+ CD4+ T cells, in unstimulated cultures compared to contacts (Table 1, P < 0.05). The average percentage of cells expressing IFN-γ was 8.3 ± 0.6% compared to contacts (2.1 ± 0.5 [Table 1], P < 0.001). Similarly, elevated levels of IL-4+ CD4+ T cells were detected in patients (5.9 ± 1.7) compared to contacts (1.5 ± 0.5) (Table 1, P < 0.05).

Of the 20 patients, 14 showed significant reduction of IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells after mycobacterial stimulation (P < 0.001). No concomitant reduction was detected in the percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing IL-4 upon mycobacterial stimulation; in fact, an increase was seen in few patients (Fig. 3 and Table 1). The reduction in IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells resulted in the dominance of IL-4+ CD4+ T cells in 13 patients (P < 0.05). The shift in cytokine profile, namely, from Th1 to Th2, was clearly evident in the CD4+ subset of T cells in patients (Table 1).

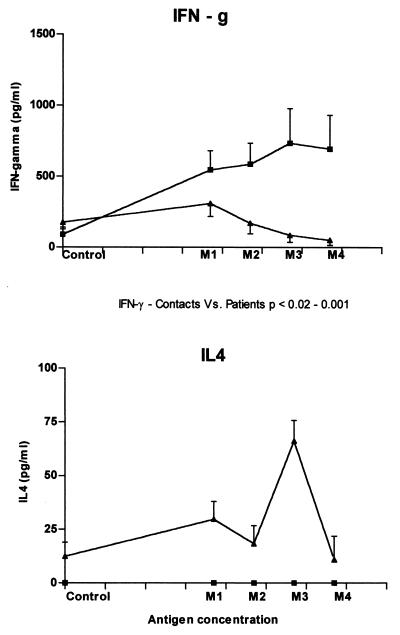

Cytokine ELISA.

IFN-γ and IL-4 present in the supernatants of PBMC were estimated by cytokine-specific ELISA for the groups of subjects mentioned above. IFN-γ levels (mean ± SEM) in supernatants of stimulated cultures were significantly higher in contacts compared to patients (Fig. 4, P < 0.05). Consistent with the data obtained by flow cytometry and whereas the healthy subjects showed an increase in IFN-γ upon stimulation with various doses of antigen, the PBMC of patients showed a decrease in IFN-γ from the second concentration (M2) onwards. Of interest was the absence of a detectable amount of IL-4 in the healthy group compared to the pulmonary tuberculosis patients. IL-4 was detected in the control cultures with a significant increase after antigen stimulation in patients. The relative levels of IFN-γ produced remained higher than the IL-4 at all antigen concentrations in patients. Hence, no differences in the type of immune response (Th1) were seen between patients and healthy contacts, as evaluated by cytokine-specific ELISA for IFN-γ and IL-4.

FIG. 4.

IFN-γ and IL-4 production as measured by ELISA. IFN-γ and IL-4 production was assessed by ELISA from supernatants collected by culturing the PBMC of patients (▴) and contacts (■) in the absence or presence of various mycobacterial-antigen concentrations (M1, 0.005 × 106; M2, 0.05 × 106; M3, 0.5 × 106; and M4, 5 × 106 M. tuberculosis bacilli/ml). Each point denotes the mean ± the SEM of the estimated cytokine concentrations.

Apoptosis (DNA fragmentation).

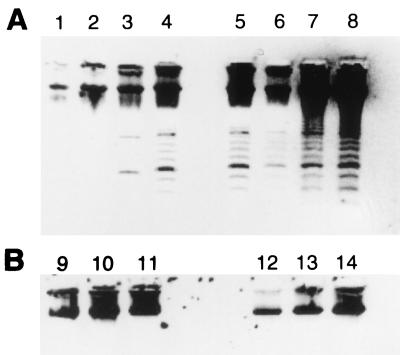

Experiments were carried out with PBMC of patients and contacts to check for the DNA laddering characteristic of apoptosis. The unstimulated (Fig. 5B, lanes 9 to 11) and stimulated (Fig. 5B, lanes 12 to 14) cultures of contacts showed no DNA fragmentation. In contrast, unstimulated cultures of two patients (Fig. 5A, lanes 3 and 4), along with the stimulated cultures (Fig. 5A, lanes 5 to 8) of all patients did show the laddering of the extracted DNA that is characteristic of apoptosis.

FIG. 5.

Apoptosis (DNA fragmentation). Agarose gel electrophoresis of DNA extracted from 48-h PBMC cultures of patients (A) and healthy contacts (B) cocultured with M. tuberculosis (lanes 5 to 8 and lanes 12 to 14) and control cultures (lanes 1 to 4 and lanes 9 to 11). A characteristic apoptotic ladder was observed in PBMC derived from patients (A) in control cultures (lanes 3 and 4) and in M. tuberculosis-stimulated cultures (lanes 5 to 8). No DNA fragmentation was seen in DNA obtained from the PBMC of healthy contacts in control (lanes 9 to 11) and M. tuberculosis-stimulated cultures, (lanes 12 to 14). The bacillus concentration used was 0.005 × 106 bacilli/ml.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that the expression of IFN-γ- and IL-4-producing cells in CD4+ T cells varied among healthy contacts and patients. More importantly, changes in patterns of the percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing IFN-γ and IL-4 were observed after in vitro stimulation of PBMC with mycobacteria. Patients had the higher number of CD4+ T cells expressing IFN-γ and IL-4 in unstimulated cultures compared to healthy subjects, although the ratio of these two subsets was similar in both groups (Fig. 3 and Table 1). This elevated response in patients, namely, larger numbers of CD4 T cells producing IFN-γ, is indicative of an on going Th1 response. However, upon stimulation with heat-killed M. tuberculosis IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells were selectively and significantly depleted in patients. The ELISA data confirms the impaired IFN-γ production by patients after mycobacterial stimulation. In contrast, the percentage of IL-4-expressing CD4+ T cells held steady in patients, with relatively little change in the percentage with antigen stimulation. This trend was seen at all concentrations of mycobacteria used in the study. Zhang and his colleagues (52) reported similar results. This selective loss of CD4 T cells producing IFN-γ in mycobacterium-stimulated cultures in patients may be significant considering the impaired cellular response in patients in specific areas such as lesions and granulomas, where the antigen concentration may be high. Nevertheless, the patients had the ability to systematically generate CD4 T cells producing IFN-γ, although local factors at the lesional site appear to critically influence the migration, sensitization, and activation of these and other immunocompetent cells. The preferential depletion of CD4 T cells producing IFN-γ in mycobacterium-stimulated cultures observed in patients appears to reflect the essential defect in cellular response at the local site of the infectious foci.

The reasons for the decrease in the IFN-γ-producing cells as a result of antigen stimulation in patients are not clear. Perhaps the effect is due to apoptosis induced by hyperstimulation of the effector population (8). Preliminary tests with PBMC incubated with mycobacterial antigen resulted in DNA fragmentation in patients (Fig. 4). However, further experiments are being carried out to define the cell subsets undergoing apoptosis. Recent reports have shown apoptosis of Th1-like cells in experimental tuberculosis (11, 48, 53). Data implicating apoptosis as having a primary role in the suppression of the immune response in tuberculosis were reported by Ellner in 1997 (14). The rapid death of Th1 cells by Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis has been shown as a likely mechanism leading to selective survival of Th2 cells in leishmaniasis (53).

In contrast, the CD4+ T cells in healthy contacts showed the induction of IFN-γ with mycobacterial-antigen stimulation. The enhancement indicates the importance of an IFN-γ response in imparting immunity to pathogenic mycobacteria. IFN-γ has been shown to be involved in inducing protective type 1 responses against M. avium and M. tuberculosis infections in mice (2, 17).

In humans decreased levels of IFN-γ have been recorded in tuberculosis patients and in patients with disseminated M. avium complex infection (18, 42, 52). MDR tuberculosis patients showed an impaired Th1 response (27). Clinical manifestations of leprosy correlate with host in vivo and in vitro immune responses to the M. leprae (28). The recent demonstration of killing of M. tuberculosis by CD4+ T cells in M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages in purified protein derivative-positive individuals (39) and the successful treatment of MDR pulmonary tuberculosis patients with aerosol IFN-γ (9) indicates the critical role played by IFN-γ in the clearance of pathogenic mycobacteria. In the murine system, a similar line of protection has been proved by studies on (i) MHC knockout mice (25), (ii) the adoptive transfer of immunized CD4+ T cells (32), (iii) IFN-γ (10), and (iv) IFN-γ receptor knockouts (21).

Though the present study is a one-point study, the data suggest that suppression of IFN-γ, along with the maintenance of the steady-state of IL-4 production, could be responsible for the persistence and progression of tuberculosis in susceptible individuals. The generation of inflammatory lesions in IL-4 transgenic mice (44) and the significant increase in the mean survival time of mice that had been infected with lethal dose of M. tuberculosis by the administration of anti-IL-4 monoclonal antibody supports this possibility (15). Earlier studies based on ELISA and enzyme-linked immunospot assay also indicated an increase of IL-4 production in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis (36, 41). If we take into consideration the ELISA data (Fig. 4), the relative levels of IL-4 production remained less than the total level of IFN-γ. However, the dominant biological influence of IL-4 compared to IFN-γ and other cytokines could influence the initiation of impaired cellular responses seen in patients (19).

In addition to the CD4+ T cells examined in the present study, IFN-γ and IL-4 expression has also been evaluated in CD8+ and γδ T cells. In all categories of individuals examined the γδ subsets of T cells showed no significant difference in the percentage of cells expressing IFN-γ and IL-4. Similar observations were made with the CD8+ T subset except in the case of a limited number of patients. In these individuals CD8+ T cells expressing IFN-γ were detected (data not shown). It was seen that a non-T-cell population contributed the bulk of IFN-γ only at the lowest antigen concentration in healthy contacts. The significance of these cells expressing IFN-γ and their role in immunity to tuberculosis still needs to be investigated. There have been reports demonstrating the positive role of non-T cells, such as NK cells, in antimycobacterial host response, (2, 14).

The present study indicates that the preferential loss of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells occurs in patients upon coculture with concentrations of M. tuberculosis antigen exceeding 0.005 × 106/ml. This then results in an impaired Th1-type response and the maintenance of steady-state of IL-4-producing T cells. This cellular response does not reflect the systemic response since the PBMC of patients had a higher percentage of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells than did healthy contacts. However, this effect may be of significance in view of the localized cellular response in granulomatous lesions where the mycobacterial antigen concentration may be high. The inability to generate a protective immune response at the lesional site leads to a prolonged chronic fatal disease in patients. Therefore, study of the manifestations of cellular responses at the lesional site, such as factors influencing impairment of Th1-type immune response and the role of apoptosis in the elimination of immunoreactive cells, could provide alternate targets for the immunotherapeutic treatment of these individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work received financial support from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India.

Satyajit Rath (NII) and S. N. Das (AIIMS) kindly provided flow cytometry facilities. Incisive discussions with S. Rath and J. S. Tyagi, Indira Nath helped us immensely. S. N. Dwivedi and Rajbir Singh of the Department of Biostatistics, AIIMS., helped us in analyzing the data. S.B. is a recipient of a UGC fellowship. Dhanpal Singh provided technical help. Assistance from Biotechnology Information Service and Bhavneet Singh is also acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas A K, Murphy K M, Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature. 1996;383:787–793. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appleberg R, Castro A G, Pedrosa J, Silva R A, Orme I M, Minoprio P. Role of IFN-γ and TNF alpha during T-cell-independent and -dependent phases of Mycobacterium avium infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3962–3971. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3962-3971.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhattacharyya S, Das S N, Dey A B, Nagarkar K, Lobo J, Kapoor S K, Prasad H K. Flow cytometric assessment of intracellular interferon-γ production in human CD4+ve T cells on mycobacterial antigen stimulation. J Biosci. 1997;22:99–109. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bose M, Gupta A, Banavalikar J N, Saha K. Dysregulation of homeostasis of blood T-lymphocyte subpopulations persists in chronic multibacillary pulmonary tuberculosis patients refractory to treatment. Tubercle Lung Dis. 1995;76:59–64. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(95)90581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyum A. Isolation of mononuclear cells and granulocytes from human blood. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1968;21(Suppl. 97):77–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chase M W. The cellular transfer of cutaneous hypersensitivity to tuberculin. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1945;59:134–135. doi: 10.3181/00379727-71-17242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choong M L, Ton S H, Cheong S K. Influence of race, age and sex on the lymphocyte subsets in peripheral blood of healthy Malaysian adults. Ann Clin Biochem. 1995;32(Pt. 6):532–539. doi: 10.1177/000456329503200603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen J J. Exponential growth in apoptosis. Immunol Today. 1995;16:346–348. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Condos R, Rom W N, Schluger N W. Treatment of multi-drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis with interferon-gamma via aerosol. Lancet. 1997;349:1513–1515. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)12273-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper A M, Dalton D K, Stewart T A, Griffin J P, Russell D G, Orme I M. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon γ gene-disrupted mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2243–2247. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das G, Vohra H, Saha B, Agrewala J N, Mishra G C. Apoptosis of Th1 like cells in experimental tuberculosis (TB) Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;115:324–328. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00755.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denis M. Killing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within human monocytes: activation by cytokines and calcitriol. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;84:200–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb08149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douvas G S, Looker L L, Vatter A E, Crowle A J. Gamma interferon activates human macrophages to become tumoricidal and leishmanicidal but enhances replication of macrophage associated bacteria. Infect Immun. 1985;50:1–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.1.1-8.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellner J J. Regulation of the human immune response during tuberculosis. J Lab Clin Med. 1997;130:469–475. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(97)90123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eremeev V V, Audienko V G, Bocharove I V, Liashenko S M, Moroz A M. Modulation of the course of experimental tuberculosis in mice by in vivo administration of monoclonal antibodies to interleukin-2, gamma-interferon and interleukin-4. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 1995;7:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flesch I, Kaufmann S H E. Mycobacterial growth inhibition by interferon-γ-activated bone marrow macrophages and differential susceptibility among strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1987;138:4408–4413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flynn J L, Chan J, Triebold K J, Dalton D K, Stewart T A, Bloom B R. An essential role for IFN-γ in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2249–2254. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frucht D M, Holland S M. Defective monocyte costimulation for IFN-γ production in familial disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Immunol. 1996;157:411–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gros L G, Ben-Sasson S Z, Seder R, Finkelman F D, Paul W E. Generation of interleukin-4 (IL-4)-producing cells in-vivo and in-vitro are required for in vitro generation of IL-4-producing cells. J Exp Med. 1990;172:921–929. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung T, Schauer U, Heusser C, Neumann C, Rieger C. Detection of intracellular cytokines by flowcytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1993;159:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamijo R, Le J, Shapiro D, Havell E A, Huang S, Auget M, Bosland M, Vilcek J. Mice that lack the interferon-γ receptor have profoundly altered responses to infection with bacillus Calmette-Guerin and subsequent challenge with lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1435–1440. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelso A. Th1 and Th2 subsets: paradigm lost? Immunol Today. 1995;16:374–379. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kochi A, Vareldzis B, Styblo K. Multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis and its control. Res Microbiol. 1993;144:104–110. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(93)90023-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krause A K. A few observations on immunity to tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1922;19:306–308. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ladel C H, Daugelet S, Kaufmann S H. Immune response to Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette Guerin infection in major histocompatibility complex class I and class II deficient knock-out mice: contribution of CD4 and CD8T cells to acquired resistance. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:377–384. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lurie M B. Studies on the mechanism of immunity in tuberculosis. The fate of tubercle bacilli ingested by mononuclear phagocytes derived from normal and immunised animals. J Exp Med. 1942;75:247–268. doi: 10.1084/jem.75.3.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDyer J F, Hackley M N, Walsh T E, Cook J L, Seder R A. Patients with multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis with low CD4+ T-cell counts have impaired Th1 responses. J Immunol. 1997;158:492–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Modlin R L. Th1-Th2 paradigm: insights from leprosy. J Investig Dermatol. 1994;102:828–832. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12381958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mosmann T R, Coffman R L. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray C J L, Styblo K, Rouillon A. Tuberculosis in developing countries: burden, intervention and cost. Bull Int Union Tubercle Lung Dis. 1990;65:6–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narain J P, Raviglione M C, Kochi A. HIV-associated tuberculosis in developing countries: epidemiology and strategies for prevention. Tubercle Lung Dis. 1992;73:311–321. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(92)90033-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orme I M, Collind F M. Protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by adoptive immunotherapy. Requirement for T-cell-deficient recipients. J Exp Med. 1983;158:74–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson D S, Hamid Q, Ying S, Tsicopoulous A, Barkans J, Bently A M, Corrigan C, Durham S R, Kay A B. Predominant TH2-like bronchoalveolar T-lymphocyte population in atopic asthma. New Engl J Med. 1992;326:298–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201303260504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romagnani S. Lymphokine production by human T cells in disease states. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:227–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rook G A W, Steele J, Ainsworth M, Champion B R. Activation of macrophages to inhibit proliferation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: comparison of the effects of recombinant gamma-interferon on human monocytes and murine peritoneal macrophages. Immunology. 1986;59:333–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanchez F O, Rodriguez J I, Agudelo G, Garcia L F. Immune responsiveness and lymphokine production in patients with tuberculosis and healthy controls. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5673–5678. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5673-5678.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sander B, Andersson J, Andersson U. Assessment of cytokines by immunofluorescence and the paraformaldehyde-saponin procedure. Immunol Rev. 1991;119:65–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1991.tb00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siegel S. Non-parametric statistics for the behavioral sciences, international student edition. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc.; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silver R F, Li Q, Boom W H, Ellner J J. Lymphocyte-dependent inhibition of growth of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv within human monocytes: requirement for CD4+ T cells in purified protein derivative positive but not in purified protein derivative negative subjects. J Immunol. 1998;160:2408–2417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slutkin G, Leowki J, Mann J. The effect of AIDS epidemic on the tuberculosis problem, and on the tuberculosis programme. Bull Int Union Tubercle Lung Dis. 1988;63:21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Surcel H M, Troye-Blomberg M, Paulie S, Andersson G, Morreno C, Pasvol G, Ivanyi J. TH1/TH2 profiles in tuberculosis, based on proliferation and cytokine response of blood lymphocytes to mycobacterial antigens. Immunology. 1994;81:171–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taha R A, Kotsimbos J C, Song Y L, Menzies D, Hamid Q. IFN-gamma and IL-12 are increased in active compared with inactive tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1135–1139. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.3.9116999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan J S, Canaday D H, Boom W H, Balaji K N, Schwander S K, Rich E A. Human alveolar T lymphocyte responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens. Role for CD4+ and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and relative resistance of alveolar macrophages to lysis. J Immunol. 1997;159:290–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tepper R I, Levinson D A, Stanger B Z, Campos-Torres J, Abbas A K, Leder P. IL-4 induces allergic-like inflammatory disease and alters T cell development in transgenic mice. Cell. 1990;62:457–467. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toossi Z, Kleinerz M E, Ellner J J. Defective interleukin-2 production and responsiveness in human pulmonary tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 1986;163:1162–1172. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.5.1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turcotte R, Des Ormeaux Y, Borduas A F. Partial characterization of a factor extracted from sensitized lymphocytes that inhibits the growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within macrophages in vitro. Infect Immun. 1976;14:337–344. doi: 10.1128/iai.14.2.337-344.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turett G S, Telzak E E. Normalization of CD4+ T-lymphocyte depletion in patients without HIV infection treated for tuberculosis. Chest. 1994;105:1335–1337. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.5.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Varadhachary A S, Perdo S N, Hu C, Ramanarayanan M, Salgame P. Differential ability of T cell subsets to undergo activation-induced cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5778–5783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vithayasai V, Sirisanthana T, Sakonwasun C, Suvanpiyasiri C. Flow cytometric analysis of T-lymphocytes subsets in adult Thais. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 1997;15:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Webster H K, Pattanapanyasat K, Phanupak P, Wasi C, Chuenchitra C, Ybarra L, Buchner L. Lymphocyte immunophenotype reference ranges in healthy Thai adults: implications for management of HIV/AIDS in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1996;27:418–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamamura M, Uyemura K, Deans R J, Weinberg K, Rea T H, Bloom B R, Modlin R L. Defining protective response to pathogens: cytokine profiles in leprosy lesions. Science. 1991;254:277–279. doi: 10.1126/science.254.5029.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang M, Lin Y, Iyer D V, Gong J, Abrams J S, Barnes P F. T cell cytokine responses in human infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3231–3234. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3231-3234.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang X, Brunner T, Carter L, Dutton R W, Rogers P, Bradley L, Sato T, Reed J C, Green D, Swain S L. Unequal death in T helper cell 1 (Th1) and Th2 effectors: Th1 but not Th2 effectors undergo rapid Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1837–1849. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.10.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]