Abstract

Survival and growth of salmonellae within host cells are important aspects of bacterial virulence. We have developed an assay to identify Salmonella typhimurium genes that are induced inside Salmonella-containing vacuoles within macrophage and epithelial cells. A promoterless luciferase gene cassette was inserted randomly into the Salmonella chromosome, and the resulting mutants were screened for genes upregulated in intracellular bacteria compared to extracellular bacteria. We identified four genes in S. typhimurium that were upregulated upon bacterial invasion of both phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells. Expression of these genes was not induced by factors secreted by host cells or media alone. All four genes were induced at early time points (2 to 4 h) postinvasion and continued to be upregulated within host cells at later times (5 to 7 h). One mutant contained an insertion in the ssaR gene, within Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI-2), which abolished bacterial virulence in a murine typhoid model. Two other mutants contained insertions within SPI-5, one in the sopB/sigD gene and the other in a downstream gene, pipB. The insertions within SPI-5 resulted in the attenuation of S. typhimurium in the mouse model. The fourth mutant contained an insertion within a previously undescribed region of the S. typhimurium chromosome, iicA (induced intracellularly A). We detected no effect on virulence as a result of this insertion. In conclusion, all but one of the genes identified in this study were virulence factors within pathogenicity islands, illustrating the requirement for specific gene expression inside mammalian cells and indicating the key role that virulence factor regulation plays in Salmonella pathogenesis.

Salmonella-induced gastroenteritis is a multifaceted disease, requiring many different bacterial gene products to be expressed in a coordinated fashion (3, 5, 6, 15, 33, 35, 51). Salmonella species (specifically S. typhimurium and S. dublin) cause disease through their ability to adapt and grow in hostile environments within the body, simultaneously evading the immune system. During the disease process, salmonellae exist in both extracellular (29) and intracellular (14, 21, 30, 44) environments, and it is now clear that the intracellular component plays a significant role in the disease. Salmonellae that are attenuated for either invasion or survival within cells are less virulent (18, 31, 32, 40).

Bacterial pathogens tightly regulate the expression of genes required for virulence, and this regulation is often in response to very specific environmental conditions. Using two-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, several groups have shown that salmonellae inside cultured macrophages express different proteins than when grown in media (1, 11, 12). While these studies have provided a global picture of intracellular gene expression, they are limited in their ability to study the expression of individual genes. Although more than 100 bacterial proteins are upregulated within cells, and approximately 40 of these appear to be unique to the intracellular environment, few of these proteins have been identified.

A number of techniques have recently become available to identify the induction of specific Salmonella genes. A technique known as IVET (in vivo expression technology) positively selects for bacterial genes expressed upon infection of mice (15, 24, 25, 33). Genes expressed at any time during infection, rather than those genes expressed only upon interaction with a particular cell type, will be identified by this technique. While the relevance of IVET cannot be disputed, the selection process requires that the bacterial clones survive within the host until they can be recovered from the organs. Furthermore, IVET does not indicate at which point the bacterial genes are required (i.e., whether they are transiently induced or expressed in vivo at all times). In addition, a large number of the identified bacterial genes (i.e., housekeeping genes) are not specific for virulence. A second technique, known as differential fluorescence induction, uses the green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a reporter to identify genes expressed by salmonellae within macrophages (50, 51). This method involves using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter to isolate macrophages containing bacteria that express GFP after infection of cells. One limitation of this technique is that there is a time lag between expression and signal production of GFP, and the time course of GFP fluorescence has not been as well detailed as for other reporters, such as luciferase or β-galactosidase. Techniques involving the use of sensitive reporters such as bacterial luciferases (20, 41), β-galactosidase (3, 10, 19), and Pap fimbriae (43) have demonstrated the upregulation of specific genes by salmonellae inside tissue culture cells. However, these methods can detect the expression of only a single gene or a small number of genes at one time.

Here we describe the use of light-producing luciferase as a real-time reporter to globally screen for bacterial genes induced in the intracellular environment. Bacterial luciferase, encoded by the promoterless Vibrio harveyi luxAB gene cassette, has previously been used as a reliable indicator of intracellular Salmonella gene expression (41). The luxAB genes are not transcribed, and light production is negligible unless the cassette is inserted downstream of an active promoter (23, 41). In addition, the activity can be detected from bacteria while they remain inside cells, since the amphipathic luciferase substrate (n-decanal) is able to efficiently cross both mammalian and bacterial cell membranes (41). Luciferase from V. harveyi is also active at 37°C, unlike other bacterial luciferases (e.g., from V. fischeri) that are active at 28°C (34). Furthermore, the V. harveyi luciferase enzyme does not accumulate within the bacteria, with a half-life of less than 1 h at 37°C, allowing for the monitoring of gene expression over time (17). Another advantage of this system is that only activity from live bacteria is detected; bacterial luciferase requires energy, and nonviable bacteria do not exhibit activity (17, 34, 41). Therefore the activity of the luciferase reporter can be correlated to the number of cultured bacteria, allowing for a more accurate determination of gene expression compared to other reporters, such as β-galactosidase, whose activity can be detected from both live and killed bacteria. For these reasons, we used the luciferase system to detect gene expression from live intracellular salmonellae.

We used a modified two-plasmid competition system to randomly insert a promoterless luciferase gene cassette throughout the Salmonella chromosome. The system was initially developed in Escherichia coli (23), and in both bacterial systems, single insertions of the gene cassette within the bacterial chromosome were detected. We screened individual bacterial mutants for their lack of luciferase activity when outside cells and then further selected mutants that were able to induce light production from the intracellular environment within the Salmonella-containing vacuole (SCV) in both phagocytic and nonphagocytic cell lines. These inducible mutants were further characterized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and bacteriophage.

The bacterium S. typhimurium SL1344 (27) was used throughout. Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and agar plates and DMEM++ (Dulbecco's minimal Eagle's medium [Gibco Life Technologies] supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum [Gibco Life Technologies] and 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) were used to grow bacteria as indicated.

The phages P22HTint and P22H3 were harvested and used as previously described (46). P22HTint was used as a vehicle to transfer both plasmids and chromosomal insertions from one Salmonella strain to the next, while P22H3 was used for cross-streaking experiments to determine whether bacteria were phage sensitive (true transductants with no remaining phage lysogens) or resistant (lysogens) after transduction. Green plates were made up as previously described (46) and used to isolate phage-free bacteria after transductions. Mud-P22 prophage were used for rapid mapping of the gene insertions on the S. typhimurium chromosome (7).

Cell lines.

Two nonphagocytic cell lines, Madin-Darby canine kidney MDCK (ATCC CCL-34) and the human epithelial cell line HeLa (ATCC CCL-2), and two phagocytic cell lines, BALB/c mouse macrophage-like cell line J774A.1 (ATCC TIB-67) and the mouse bone marrow-derived macrophage cell line BALB.BM1 (8, 9), were used. Cultured cells were grown in DMEM++ at 37°C in 5% CO2.

DNA manipulations.

Plasmid preparations were made by the alkaline lysis technique as previously described (45), with an extra phenol-chloroform step added. Bacterial chromosomal DNA preparations were made as previously described (4).

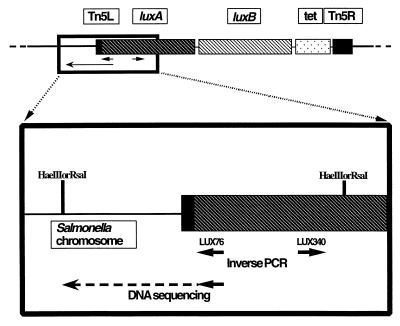

For inverse PCRs (39, 49), AmpliTaq Gold polymerase (Perkin-Elmer) was used. For sequencing reactions, AmpliTaq dye terminator cycle sequencing chemistry (Applied Biosystem, Inc.) with FS Taq was used. Sequencing gels were run by the Nucleic Acids and Proteins Unit at the University of British Columbia. Sequences were further analyzed by using the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST server and GenBank. Oligonucleotides used were 18-mer LUX76 (5′- CAA GCG ACG TTC ATT CAC), 18-mer LUX340 (5′- TGC CGC ACA TCT ATT AGG), 20-mer E-PLUS (5′- CAG TTT TCC AAT TAC CTC CC), 22-mer E-MINUS (5′- TTC TGG AGG ATG TCA ACG GGT G), 20-mer G-MINUS (5′- GGA GGA ATG CAC ACC TTT AG), and 19-mer G-PLUS (5′- TAG TCC CTA ACC CCC ATT G). Primer set LUX76-LUX340 was used to amplify upstream regions from all clones initially identified. Primer set E-MINUS-E-PLUS was used to further amplify and sequence the region around the insertion site of E12A2, and primer set G-MINUS-G-Plus was used to sequence around the insertion site of G7H1.

Transformation of salmonellae.

A two-plasmid competition system, previously described by Guzzo and DuBow (23), was used to obtain random insertions of a promoterless luciferase gene cassette throughout the Salmonella chromosome. Competent S. typhimurium SL1344 bacteria were initially transformed by electroporation with plasmid pFUSLUX (23) or pTF421 (23). Plasmid pFUSLUX has a ColE1 origin of replication and carries a gene cassette, flanked by Tn5 transposon sequences, containing promoterless V. harveyi luciferase genes, luxAB, and a gene coding for tetracycline resistance. Plasmid pTF421 carries resistance to ampicillin and encodes RNA1, which inhibits the replication of ColE1-based plasmids. Resulting bacterial transformants were selected on LB plates containing either tetracycline (15 μg/ml) or ampicillin (100 μg/ml). A phage P22HTint lysate was then made of SL1344 pFUSLUX and used to transfect SL1344 pTF421. SL1344 bacteria containing both plasmids were then grown for more than 5 days on LB plates containing both ampicillin and tetracycline. As a result of the cohabitation of the two plasmids, plasmid pFUSLUX was unable to replicate and the gene cassette was forced into the bacterial chromosome in order to maintain resistance to tetracycline. The extended incubation caused the bacteria to enter a hypermutability state that allowed for the random insertion of the luxAB-containing gene cassette into the bacterial chromosome (23). Previous testing with E. coli had shown that single chromosomal insertions resulted from this technique (23).

Screen for upregulation of intracellular bacterial gene expression.

Colonies that were resistant to both ampicillin and tetracycline were tested for light production by exposing the colonies to vapors of n-decanal (99%; Sigma), which was prepared as previously described (41) and streaked onto the lid of the petri plate by using a sterile swab. The resulting light output was imaged with a Luminograph LB980 low-light video imaging system (EG&G Berthold) (41) (results not shown). Of the approximately 1.5 × 105 colonies that were initially screened in this manner, approximately 3,500 (about 2.4%) showed low light production (less than 5 × 103 photons per colony). Colonies passing through a second round of the initial screen were individually transferred to broth cultures in 96-well plates; the bacterial mutants were not pooled. Bacteria transferred to broth were also streaked onto green plates to ensure that they were not chronically infected with phage P22 (46).

The selected bacterial mutants were tested for low light production outside mammalian cells while showing an induction of light following invasion of the cells. Both J774A.1 and BALB.BM1 macrophage cell lines were used for the initial screening. Approximately 3,500 S. typhimurium colonies were tested in this manner. Bacteria were initially grown at 37°C overnight in 100 μl of LB broth in 96-well plates sealed with Parafilm, with shaking at 150 rpm. Eukaryotic cells were seeded at 104 cells per well in sterile 96-well plates with black walls and clear bottoms (Corning-Costar) and were approximately 90% confluent within 18 h. The overnight bacterial plates were used as the extracellular stationary-phase bacterial controls. For the extracellular bacterial logarithmic-phase control plates, a 1:5,000 dilution of the stationary-phase bacteria was made in DMEM++. The plates were then incubated under conditions similar to those used for the tissue culture cells, i.e., without shaking at 37°C in 5% CO2. The light from the extracellular bacteria was determined at 4 h after inoculation of the log-phase plate. For the intracellular test plates, a 1:50 dilution of each bacterial mutant from the stationary-phase plates was used to inoculate the plates containing the macrophages. Bacteria were allowed to invade for 1 h, after which the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and DMEM++ containing gentamicin (100 μg/ml) was added. Light from the intracellular bacteria was first determined at 2 h postinoculation and again at 4 h. Once the activity at the 2-h time point had been determined, the aldehyde-containing medium was removed and replaced with fresh DMEM++ with gentamicin for another 2 h. After 4 h, the intracellular activity was again determined, and the bacteria were enumerated by serial dilutions and plating.

Invasion assay.

Invasion assays were done with a modified version of the gentamicin protection assay described by Tang et al. (48). S. typhimurium SL1344 and mutants A1A1, D11H5, E12A2, and G7H1 were grown overnight in 1 ml of LB broth in culture tubes, with shaking at 200 rpm, subcultured at a 1:100 dilution in DMEM++, and grown for another 3 h with shaking. Cultured mammalian cells (90% confluent) were infected with 2 μl of the bacterial cultures (multiplicity of infection was 50 to 100 bacteria per cell). Bacteria were allowed to invade phagocytic cells for 30 min and nonphagocytic cells for 1 h. (Note that bacterial growth and subsequent invasion of host cells took place in DMEM++ medium, which contained 10% fetal bovine serum.) Following internalization of the bacteria, the supernatant containing extracellular bacteria was removed. The cells were then washed with PBS and incubated with 100 μl of DMEM++ containing 100 μg of gentamicin per ml, which killed any extracellular bacteria remaining in the well after the washes. Where bacterial growth was studied for longer than 4 h, the gentamicin concentration was reduced to 10 μg/ml at 4 h in order to reduce any toxic effects of gentamicin on both the cells and intracellular bacteria. Cells were then lysed in 20 μl of PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. Dilutions were made in PBS, and bacteria were plated onto LB agar for enumeration. Bacterial counts were obtained from sample wells after the luciferase activity was determined. All activities shown in the figures were obtained from triplicate experiments, and error bars represent the standard error of the mean, P < 0.5 (36).

Two variations of this invasion assay were also used to test bacterial invasion into host cells, since slight variations in technique may have a great effect on the results for a given experiment. In one variation, S. typhimurium parent and mutant strains were grown overnight in standing LB cultures as described by Hong and Miller (28) rather than subcultured in DMEM++ as described above. However, invasion of host cells by bacteria grown in this manner took place in DMEM++, which contained serum, and the remainder of the assay was as described above. A second variation tested bacterial invasiveness in the absence of serum. Bacteria were first grown overnight in 1 ml of LB broth in culture tubes, with shaking at 200 rpm, and then subcultured at a 1:100 dilution in fresh LB broth and grown shaking for another 3 h. The bacteria were then centrifuged for 2 min in a microcentrifuge and resuspended in 1 ml of Earle's balanced salt solution (Gibco Life Technologies). Invasion was then carried out in Earle's balanced salt solution. After a 15-min incubation, the supernatant was removed, the cells were washed with PBS, and the medium was replaced with 100 μl of DMEM++ containing 100 μg of gentamicin per ml. The assay was continued as described above.

Luciferase assay.

Luciferase assays were done as outlined previously (41), a procedure which included using the gentamicin protection assay technique to distinguish between intracellular and extracellular bacteria. Ten-microliter aliquots of the aldehyde substrate were added directly to 100-μl samples of either bacteria alone or intact cells containing intracellular bacteria, and light production was determined on a Luminograph LB980. Light emissions were obtained as photons per sample well. For characterization of the mutants in later studies, CFU were determined for each sample (see below), and activity was defined as photons per CFU. All activities shown in the figures were obtained from triplicate experiments, and error bars represent the standard error of the mean, P < 0.5 (36).

Typhoid mouse model.

Salmonella suspensions were grown at 37°C in LB broth overnight, with shaking at 200 rpm. The next day, bacteria were diluted 1:100 into fresh LB broth and incubated with shaking. After 4 h, bacteria were washed once with PBS and resuspended in PBS containing 2% glucose. Control mice were given PBS with glucose only. BALB/c female mice, aged 6 to 10 weeks, were inoculated orally with bacterial suspensions (31), after being deprived of water for 4 h. In the first experiment, the inoculation size was 25 μl. The dose of wild-type SL1344 was 2.5 × 106 CFU per mouse (approximately twice the reported 50% lethal dose [31]). The Salmonella mutants were given at 200 times this dose (5 × 108 CFU/mouse). Actual counts per mouse (per 25 μl) were as follows (±10% error): for D11H5, 4.2 × 108 CFU; for A1A1, 4.1 × 108 CFU; for E12A2, 3.3 × 108 CFU; and for G7H1, 5.0 × 108 CFU. Four mice were used per group. In the second experiment, three doses were used of approximately 108, 107, and 106 CFU/mouse. Actual counts per mouse (per 10 μl) were 10-fold dilutions of the following (±10% error): 7.6 × 107 CFU of SL1344; 9.6 × 107 CFU of A1A1; 1.3 × 108 CFU of E12A2; and 1.0 × 108 CFU of G7H1. Five mice were used per group. Mice surviving after 28 days were sacrificed; their livers and spleens were harvested, the organs were homogenized, and the resulting slurry was spread onto MacConkey plates to obtain bacterial colony counts. The day at which 50% of the mice in each group had died was determined by using the statistical calculations of Reed and Muench (42) and the median survival time (36).

In addition to oral infections, BALB/c mice were also intravenously inoculated with S. typhimurium by using tail vein injections as described by Richter-Dalfors et al. (44). Both wild-type Salmonella strain SL1344 and the mutants were injected at a dose of approximately 40 (±10% error) CFU per mouse. Five mice were used per group.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequence for iicA (G7141) has been submitted to GenBank and assigned accession no. AF164435.

RESULTS

Transformation of salmonellae and screen for upregulated bacterial genes.

A two-plasmid competition system (23) was transformed into wild-type S. typhimurium SL1344 in order to obtain random insertions of the promoterless reporter gene cassette luxAB within the chromosome. Approximately 1.5 × 105 S. typhimurium colonies resulted from the transformation with plasmids pFUSLUX (containing a ColE1 origin of replication and the Tn5::luxAB::tetracycline resistance cassette) and pTF421 (coding for ampicillin resistance and the production of RNA1, which acts to inhibit replication of plasmids containing ColE1 origins). By growing the colonies in the presence of both tetracycline and ampicillin, we selected for the transfer of the luxAB-containing cassette from the replication-inhibited plasmid pFUSLUX to the bacterial chromosome, where the tetracycline resistance would be maintained.

Using a Luminograph LB980 photon imager, we tested each colony for light production (i.e., luciferase activity) on LB agar plates. Those producing high amounts of light (more than 5 × 103 photons per colony) on plates were discarded. Over 3,500 colonies (about 2.4%) displaying low luciferase activity were detected, and each was then inoculated into LB broth in individual wells of a 96-well plate. At this stage, each colony was tested for luciferase activity during growth both outside and inside host cells. Eight bacterial mutants consistently demonstrated an estimated fivefold or greater upregulation in light production at both 2 and 4 h inside macrophages (J774A.1 and BALB.BM1) compared to the extracellular controls (results not shown).

To ensure the phenotype was linked to one particular gene and resulted from a single chromosomal insertion of the gene cassette, phage P22 lysates were made from each mutant and used to infect clean S. typhimurium SL1344 backgrounds. The new bacterial constructs were then tested to see whether their patterns of light induction matched that of the parent. Four mutants were identified and were named A1A1, E12A2, D11H5, and G7H1.

Inverse PCR and sequencing.

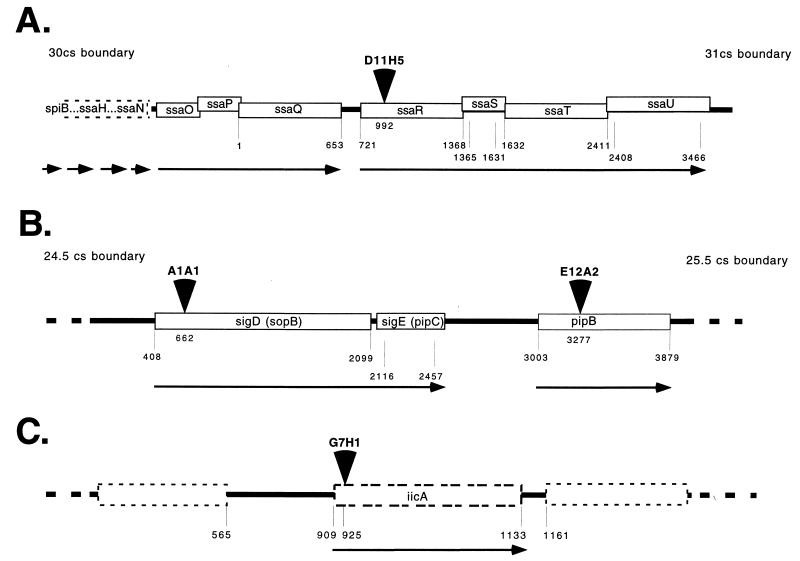

Inverse PCR, using outfacing primers LUX76 and LUX340 based on the luxA gene sequence, was used to amplify regions immediately upstream from the inserted luxAB genes (Fig. 1). Figure 2 illustrates the positions of these four insertions. D11H5 had the luxAB cassette inserted within the ssaR gene, which is found within Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI-2) (26) (accession numbers are given in the legend to Fig. 2). A1A1 had the gene cassette inserted within the sopB (sigD) gene found at centisome 25 on the chromosome (28) in a region recently called SPI-5 (52). In mutant E12A2 the luxAB gene cassette was inserted downstream of the sopB (sigD) gene in a region previously identified as a potential open reading frame (ORF) in S. typhimurium, and it is homologous to pipB of S. dublin. The S. typhimurium pipB gene is more than 90% identical at the nucleotide level to the S. dublin gene pipB. In mutant G7H1, the insertion was in a region that has not yet been identified; therefore, we named the potential ORF iicA (induced intracellularly A). However, this sequence appears to be present in both S. typhimurium and S. typhi genomes and matched a number of contigs found in the unfinished Salmonella sequencing projects at the Genome Sequencing Center at Washington University School of Medicine (22a) (B_STM.CONTIG.1607, B_STMA2A.CONTIG.3097, and B_STMA2A.CONTIG.3068) and The Sanger Centre (45a) (B_TYPHI2.hb56c04.s1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic of the luciferase reporter gene cassette which was inserted into the bacterial chromosome, and the orientation of the primer pairs used for inverse PCR and subsequent DNA sequencing.

FIG. 2.

Positions of luciferase gene insertions within known S. typhimurium genes. Insertions are indicated by arrowheads. Direction of transcription is indicated by the arrow below each gene. Numbers underlying genes correspond to sequence numbering in the accession references for S. typhimurium. (A) D11H5 had an insertion within the ssaR gene, which is part of SPI-2 found between centisomes (cs) 30 and 31 on the S. typhimurium chromosome (accession no. X99944). This region is part of an operon where the ORFs are found to overlap. (B) Both A1A1 and E12A2 had insertions within SPI-5 located near centisome 25 on the S. typhimurium chromosome (accession no. AF021817 and AF060858). A1A1 had an insertion in sopB/sigD, while E12A2 had an insertion within a downstream ORF, pipB. The corresponding genes from S. dublin, if named differently, are indicated in parentheses. (C) G7H1 had an insertion within a previously uncharacterized region of the Salmonella chromosome (accession no. AF164435). The insertion appeared to be within the 5′ end of a potential ORF.

Comparison of gene expression.

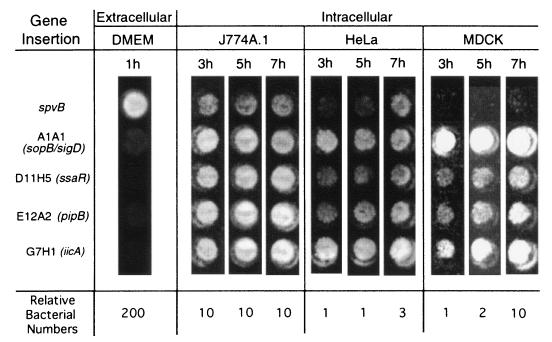

Luciferase activity, indicating gene expression, was induced intracellularly for each of the selected genes compared to extracellular activity. This is clearly evident in Fig. 3, particularly as the number of bacteria assayed was 20- to 200-fold higher in the extracellular media. The upregulation of bacterial gene expression occurred within macrophage-like cells (J774A.1) and also in the nonphagocytic cells (HeLa and MDCK). The spvB gene was used as a positive control for intracellular gene expression by S. typhimurium and has previously been shown to be induced 5- to 20-fold by intracellular Salmonellae, using a number of reporters including bacterial luciferase (41), β-galactosidase (19), and Pap fimbriae (43). Comparatively, the four genes detected in this study appear more tightly regulated outside of cells and more highly expressed inside cells than spvB.

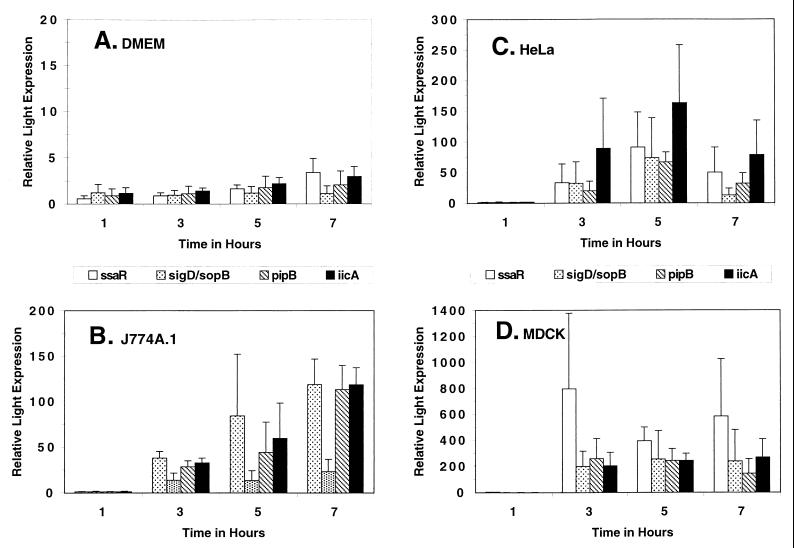

FIG. 3.

S. typhimurium mutants show increased light production inside mammalian cells. The image was taken using a Luminograph LB980 photon detector and provides a visual demonstration of gene induction. Note that the number of extracellular bacteria is 20- to 200-fold higher than the number of intracellular bacteria. The spvB gene is included as a positive control and has previously been shown to be induced within cells 5- to 20-fold compared to extracellular logarithmically growing bacteria.

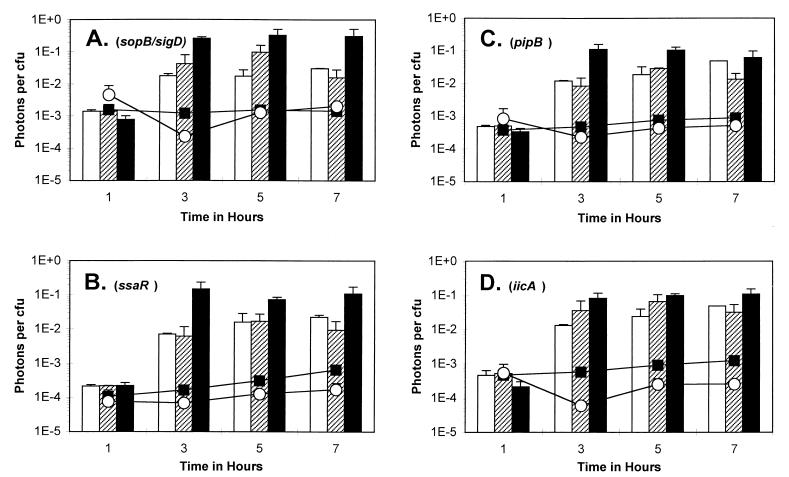

The high intracellular production of luciferase activity by the Salmonella mutants is further illustrated in Fig. 4. The bacteria remaining outside mammalian cells (i.e., those which did not invade the cells within the given time period) did not produce any more light than those grown in media alone, indicating that neither the proteins in the media and serum nor factors secreted by the cells were sufficient to induce the genes. The chance of finding mutants induced largely by growth phase was minimized in our rigorous screening setup. Contrary to previous findings (28), the sopB/sigD gene did not appear to be induced over time in media alone (up to 7 h), as indicated in Fig. 4A. The luciferase activity from the extracellular mutant A1A1 (sopB/sigD) was approximately 10−3 photons per CFU, which increased to 0.2 × 10−1 to 4.0 × 10−1 photons per CFU inside mammalian cells (Fig. 4A). For mutant D11H5 (ssaR), extracellular luciferase activity was approximately 2.0 × 10−4 photons per CFU, while intracellular activity ranged from 0.07 × 10−1 to 1.5 × 10−1 photons per CFU (Fig. 4B). For mutant E12A2 (pipB), extracellular luciferase activity was approximately 5.0 × 10−4 photons per CFU, while intracellular activity increased to 0.08 × 10−1 to 1.0 × 10−1 photons per CFU (Fig. 4D). In contrast, the luciferase activity from the spvB mutant was approximately 5.0 × 10−3 photons per CFU in logarithmic-phase growth outside mammalian cells, while it increased to approximately 0.25 × 10−2 to 1 × 10−1 photons per CFU upon entering stationary phase or within mammalian cells (data not shown) (41).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of light production of luciferase-expressing bacterial mutants exposed to different environmental conditions. Individual bacterial mutants represented: (A) A1A1 (sopB/sigD; (B) D11H1 (ssaR); (C) E12A2 (pipB); (D) G7H1 (iicA). Lines with symbols indicate bacteria grown in medium alone, either DMEM++ (filled squares) or LB broth (open circles). Bars for the 1-h time points represent activities from only the extracellular bacteria remaining in the supernatant outside the cells; bars for the following time points (3, 5, and 7 h) represent activities from only intracellular bacteria. Cell lines: J774A.1 (open bars); HeLa (hatched bars); MDCK (filled bars). Triplicate experiments were performed, and error bars represent the standard error, P < 0.5.

The ratio of induction of luciferase activity between intracellular and extracellular bacteria is shown in Fig. 5. The ratios were determined by dividing the activity of the intracellular bacteria at the different time points by the average activity of the extracellular mutant in DMEM++ at 1 h. Ratios were similarly determined for extracellular bacteria grown in broth alone (Fig. 5A). There was no induction by DMEM++ alone (Fig. 5A) or by LB broth (data not shown). This finding reemphasized that none of the bacterial gene fusions were induced by the media alone or by cell-secreted factors. However, the data do suggest that the intracellular conditions that salmonellae encounter varies greatly between cell types. All four genes showed the highest levels of light induction in MDCK cells (Fig. 5B to D). In both MDCK and J774A.1 cells, the ssaR gene was the most highly upregulated of the four genes (400- to 800-fold and 40- to 100-fold, respectively [Fig. 5B and D). In HeLa cells, the iicA gene fusion showed the largest increase in light production of the four genes (80- to 160-fold [Fig. 5C]). The kinetics of induction also varied between the three cell types, with induction continuing to increase after 7 h in J774A.1 cells (Fig. 5B) for all four genes but appearing to peak at 5 h in HeLa cells (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

Relative luciferase activities of extracellular and intracellular Salmonella mutants. Relative light expression is the ratio of the specific activity at each time point divided by the specific activity seen for bacteria grown in DMEM++ for 1 h. Bacteria were grown in DMEM++ alone (A), macrophage-like J774A.1 cells (B), epithelial-like HeLa cells (C), kidney-like MDCK cells (D). Symbols represent D11H5 (ssaR) (clear bars), A1A1 (sigD) (speckled bars), E12A2 (pipB) (striped bars), and G7H1 (iicA) (black bars). For panels B to D, the 1-h time points represent the activities of extracellular bacteria remaining in the supernatant taken from outside the cells; the following time points (3, 5, and 7 h) represent activities from the intracellular bacteria. Triplicate experiments were performed, and error bars represent the standard error of the ratio of two means.

The ssaR gene was upregulated within cultured macrophages about 40- to 100-fold, while within cultured epithelial cells, bacterial gene expression was upregulated 30- to 800-fold, depending on the cell type (30- to 90-fold within HeLa cells and 400- to 800-fold within MDCK cells). The sopB/sigD gene was induced 10- to 20-fold inside J774A.1 cells, 10- to 70-fold within HeLa cells, and 200- to 250-fold inside MDCK cells. The pipB gene was induced 30- to 100-fold within J774A.1 cells, 20- to 70-fold inside HeLa cells, and 140- to 260-fold inside MDCK cells. Expression of the iicA gene was upregulated 30- to 120-fold inside J774A.1 cells, 80- to 160-fold inside HeLa cells, and 200- to 270-fold inside MDCK cells.

Comparison of invasiveness of the mutants.

All four mutants remained as invasive as the wild-type bacteria in epithelial cell lines (HeLa and MDCK) when invasion took place in the presence of serum (data not shown). Previously it was reported that a small deletion in sigD resulted in a 10-fold reduction in invasion (28); therefore, we tested our mutants by growing them in LB broth (either shaking overnight and subculturing the next day or standing overnight with no further subculture) and assaying for bacterial invasion in the presence or absence of serum. Only in the absence of serum were we able to detect a small decrease of 30 to 40% in the invasion of the sopB/sigD mutant into epithelial cells (data not shown). In the absence of serum, the other three mutants (ssaR, pipB, and iicA) remained as invasive as the parent strain. Interestingly, bacteria grown in LB broth were approximately 10-fold more invasive than those grown in DMEM++ (data not shown).

Comparison of growth rates of the mutants.

The growth rates of the four mutants did not differ significantly from the growth rate of the parent SL1344 when tested in LB broth or DMEM++ or within the epithelial cell lines (HeLa and MDCK). Moreover, the parental strain and all the mutants were able to survive within cultured macrophages for up to 7 h (data not shown). The bacteria were visibly cytotoxic to the mammalian cells over longer time periods of incubation (i.e., longer than 9 h).

Virulence in a murine typhoid model.

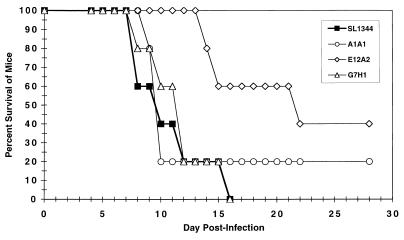

Having identified genes upregulated by the intracellular environment, experiments were carried out to determine the requirement for these genes in the disease process. The insertional mutations did not affect the invasion of S. typhimurium into cells except for the slight decrease in invasion by the sopB/sigD mutant. The virulence of the bacterial mutants was therefore tested in a typhoid mouse model. In the first experiment, the mice given D11H5 (ssaR) showed no detectable signs of disease even though they received 200 times the dose at which the wild-type bacteria were 100% lethal (i.e., approximately 1,000-fold higher than the reported 50% lethal dose for SL1344). In the second experiment, insertion into the pipB gene (E12A2) appeared to attenuate the bacteria by reducing the mortality to approximately 60% of that of the wild-type level when given at a dose of 106 CFU/mouse. At this dose, the insertion within the sopB/sigD gene (A1A1) reduced the virulence of the bacteria to approximately 80% mortality, while mutant G7H1 (iicA) remained as virulent as the wild-type SL1344 bacteria. Figure 6 shows the results of the second experiment where mice were inoculated orally with 106 CFU/mouse.

FIG. 6.

Virulence of S. typhimurium mutants in an orally infected typhoid mouse model. Each mouse was given 106 CFU, and disease progression was monitored for 1 month.

Although mutations in both the sopB/sigD (A1A1) and pipB (E12A2) regions appeared to slightly reduce the bacterial virulence, only a disruption of the pipB gene appeared to affect the rate at which disease developed in the mouse (Table 1). Generally, the higher the bacterial dose, the quicker the mice were to develop signs and die. The delay in the time at which 50% of the mice in the group had died was largest when lower doses of bacteria were used. For example, at a dose of 106 CFU/mouse, mice inoculated with E12A2 started showing signs of disease on day 12 and 50% mouse mortality was seen on day 21, while for wild-type SL1344, the mice started showing signs of disease on day 7 and 50% mortality occurred on day 13. This difference was not as noticeable at higher doses (i.e., at a dose of 107 to 108, 50% mouse mortality for E12A2 occurred only 1 to 2 days after that of the wild-type bacteria). A delay in mortality was also observed when the mice were inoculated intravenously with E12A2 (pipB). Mice inoculated with D11H5 (ssaR) showed no signs of disease and did not die during the course of the experiment (data not shown). Mice inoculated with either A1A1 or G7H1 developed disease around the same time as those inoculated with wild-type SL1344.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial dose affects kinetics of mortality of mice

| Salmonella mutant | Gene insertion | Day of 50% mouse mortalitya at bacterial dose of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 106 CFU | 107 CFU | 108 CFU | ||

| SL1344 | Wild type | 13 | 10 | 6 |

| A1A1 | sopB/sigD | 13 | 10 | 7 |

| E12A2 | pipB | 21 | 11 | 8 |

| G7H1 | iicA | 12 | 10 | 7 |

Day postinfection at which over half of the mice in the group died.

After 28 days postinfection, the remaining mice were sacrificed and organ homogenates were prepared from spleens and livers. Only the mice inoculated with either A1A1 (sopB/sigD) or E12A2 (pipB) were tested in this manner, as all mice inoculated with G7H1 (iicA) or wild-type SL1344 had died. No salmonellae could be cultured from the homogenates, indicating the mice were able to clear the bacteria completely and were not chronically infected (47).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we describe a screening procedure designed to detect bacterial genes that are upregulated by the intracellular environments of mammalian cells. Survival and growth of salmonellae within host cells are important for bacterial virulence, and recent evidence suggests that many genes required for virulence are not expressed when bacteria are grown on rich media in the absence of cells. Using this screen, we identified two genes within regions previously implicated in bacterial virulence and intramacrophage survival and showed that the intracellular environments of mammalian cells induce these genes. In addition, two new S. typhimurium genes were identified which were induced by intracellular bacteria, one of which, pipB, may affect bacterial pathogenesis.

A two-plasmid competition system was used to obtain single random insertions of a promoterless luxAB reporter gene cassette within the S. typhimurium chromosome. The luxAB genes were thereby placed under the transcriptional control of endogenous bacterial genes within the natural promoter environment, rather than from an engineered promoter or from a promoter on a multicopy plasmid. The bacterial genes were disrupted with this insertion and were not duplicated, reducing the chances of identifying genes crucial to bacterial viability (i.e., housekeeping genes) or those crucial to Salmonella survival within cells. Despite this concern, we were able to identify genes which have been previously implicated in the intramacrophage survival of Salmonella, perhaps because intracellular survival is multifactorial and possibly uses redundant factors.

We have shown that the expression of these specific bacterial genes was induced within the host cells and was not induced by media or by factors secreted by host cells (Fig. 3 to 5). The lack of induction of the genes in the media alone suggests that the genes were not regulated by quorum sensing mechanisms. These genes not only were induced at early time points after invasion (2 to 4 h) but remained upregulated after the bacteria had adapted and begun to grow within the cells (5 to 7 h). Interestingly, reporter activity from all four identified genes indicated that expression was induced in both phagocytic cells and nonphagocytic cells. Expression within cultured phagocytic cells continued to escalate over time, with the exception of the sopB/sigD gene, whose expression leveled off over time. The gene expression within the different cell types was not uniform. Of the four genes identified, ssaR was the most highly expressed within MDCK cells, while iicA was the most highly induced of the four within HeLa cells. Due to the nature of the insertional mutation, it is possible that some of the genes may play a role in their own expression (i.e., self-regulation).

The ssaR gene (D11H5), found within SPI-2, has homology to the Yersinia enterocolitica gene yscR, which encodes a membrane-bound subunit of the type III secretion system (26). We found this gene to be upregulated by S. typhimurium within cultured macrophage and epithelial cells. This insertion abolished virulence of S. typhimurium in the typhoid mouse model. These findings for the ssaR gene are novel and are consistent with previous reports of insertions within SPI-2 region (13, 51). A ssaH::gfp gene fusion was induced within macrophages and rendered the bacteria avirulent in mice (51). Various other gfp insertions into regulatory, structural, and effector/chaperone genes of SPI-2 were also found to be induced within macrophage cells. Furthermore, inactivation of type III secretion systems has been previously implicated in bacterial virulence (13, 16). The insertions within ssrA and sscB genes reduced the ability of the bacteria to spread to other organs within the mouse (13). The mutant D11H5 was not impaired in its ability to invade nonphagocytic cells, although previous reports suggest that insertions within a downstream gene (ssaT) reduced bacterial invasion (16, 26), indicating that insertion of the luxAB gene cassette did not cause a polar mutation.

The mutants A1A1 and E12A2 had insertions within the sopB/sigD (28) and pipB (53) genes, respectively. Both of these genes are located within SPI-5 (28, 53), which is found near centisome 25 in both S. typhimurium and S. dublin. The S. typhimurium sigD gene is approximately 90% identical at the nucleotide level to the S. dublin sopB gene, which has recently been described as an inositol phosphate phosphatase (38). The pipB gene is also highly similar to its pipB S. dublin counterpart, the product of which has been suggested to play a role in glycolipid biogenesis (53). It has been suggested that within the SPI-5 region of S. dublin, sopB and the downstream genes pipC, pipB, and pipA are contained within the same transcriptional unit (53). This has not been shown for the genes found within the corresponding S. typhimurium SPI-5 region, although sigDE may be transcribed from a single promoter (28). Our data shows that while the sopB/sigD (A1A1) and pipB (E12A2) genes have similar expression patterns within epithelial cell types, the levels to which they were induced are not similar (Fig. 4 and 5), the downstream pipB gene being more highly induced. Furthermore, expression of pipB continued to escalate within the intramacrophage environment, whereas expression of sopB/sigD leveled off over time. This suggests that pipB is transcribed from a separate promoter. Further support for a separate promoter lies in the observation that an insertion within the pipB gene appeared to attenuated virulence of the bacteria, while an insertion within the upstream sopB/sigD gene had little to no effect on virulence. This point also argues that there was not a downstream polar effect by the insertion of the reporter gene cassette, but that the attenuation resulted directly from inactivation of the gene containing the insertion.

In cultured cell models, it had previously been reported (28) that an insertion within either the sopB/sigD or sigE gene causes a 10-fold reduction in invasion of epithelial cells compared to wild-type bacteria. Only in the absence of serum were we able to detect a 30 to 40% reduction in invasion by the sigD mutant (A1A1). We are unable to fully explain the nature of this discrepancy, although different S. typhimurium isolates and different cell lines were used in the two reports. It is interesting to note that others have reported variability in invasion efficiency of bacterial mutants depending on the point of mutation within a gene. Hensel et al. (26) reported that only one out of three insertions within the gene ssaV (SPI-2) resulted in a 10-fold reduction in bacterial invasion, while the other two did not affect the level of invasiveness.

In our study, the insertion within pipB caused an attenuation of S. typhimurium in the typhoid mouse model but did not abolish virulence of the bacteria, as did the ssaR insertion. The insertion within the pipB gene appeared to delay the onset of the disease in mice, as well as reduce mortality. In S. dublin, it has been shown that mutations within the SPI-5 region, including deletions within sopB/sigD and pipB, reduced intestinal secretion and inflammatory responses in a calf ileal loop model (22, 52, 53), although in a mouse model, bacterial mutants were recovered from organs in the same numbers as the wild-type strain (53). These results suggested that mutations in SPI-5-encoded genes affect the bacterial enteropathogenicity in a calf ileal loop model but have no major effect on the development of systemic disease in mice. Our studies suggest that the SPI-5-encoded gene pipB may be involved with the development of systemic disease, although the difference was only apparent when lower inoculation doses were used (Table 1). Low doses of bacteria may be more physiologically relevant as to what the immune system would normally encounter during a natural infection. It is interesting that the types of animal models used may produce different results when the effects of particular bacterial genes on the disease process are characterized.

Mutant G7H1 contained an insertion within a previously undescribed region of the S. typhimurium chromosome (iicA), which also displayed upregulated reporter activity within mammalian cells. Activity was upregulated 30- to 270-fold, depending on the mammalian cell type. However, this insertion had no detectable effect on invasion or survival of the bacteria within cells, nor did it appear to attenuate bacterial virulence in the mouse model. The nucleotide sequence is present in both S. typhimurium and S. typhi; however, the function of iicA remains to be determined.

In conclusion, we have identified regions of the bacterial chromosome that are upregulated in response to the intracellular environment of mammalian cells. Of the four genes identified, three have been identified as virulence factors, indicating that genes induced inside mammalian cells often play a key role in Salmonella pathogenesis. Future experiments will define the specific environmental conditions required to induce the expression of the various genes. Finally, the techniques described here may be used to isolate additional virulence factors in Salmonella and other pathogenic bacteria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Annick Gauthier and John Brumell for careful reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abshire K Z, Neidhardt F C. Analysis of proteins synthesized by Salmonella typhimurium during growth within a host macrophage. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3734–3743. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.12.3734-3743.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmer B M M, van Reeuwijk J, Watson P R, Wallis T S, Heffron F. Salmonella SirA is a global regulator of genes mediating enteropathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1999;31:971–982. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alpuche Aranda C M, Swanson J A, Loomis W P, Miller S I. Salmonella typhimurium activates virulence gene transcription within acidified macrophage phagosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10079–10083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajaj V, Lucas R L, Hwang C, Lee C A. Co-ordinate regulation of Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes by environmental and regulatory factors is mediated by control of hilA expression. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:703–714. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.d01-1718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behlau I, Miller S I. A phoP-repressed gene promotes Salmonella typhimurium invasion of epithelial cells. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4475–4484. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.14.4475-4484.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benson N R, Goldman B S. Rapid mapping in Salmonella typhimurium with Mud-P22 prophages. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1673–1681. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1673-1681.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blasi E, Radzioch D, Durum S K, Varesio L. A murine macrophage cell line, immortalized by v-raf and v-myc oncogenes, exhibits normal macrophage functions. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:1491–1498. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830171016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blasi E, Radzioch D, Merletti L, Varesio L. Generation of macrophage cell line from fresh bone marrow cells with a myc/raf recombinant retrovirus. Cancer Biochem Biophys. 1989;10:303–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchmeier N, Bossie S, Chen C Y, Fang F C, Guiney D G, Libby S J. SlyA, a transcriptional regulator of Salmonella typhimurium, is required for resistance to oxidative stress and is expressed in the intracellular environment of macrophages. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3725–3730. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3725-3730.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchmeier N A, Heffron F. Induction of Salmonella stress proteins upon infection of macrophages. Science. 1990;248:730–732. doi: 10.1126/science.1970672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns-Keliher L, Nickerson C A, Morrow B J, Curtiss R., III Cell-specific proteins synthesized by Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1998;66:856–861. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.856-861.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cirillo D M, Valdivia R H, Monack D M, Falkow S. Macrophage-dependent induction of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system and its role in intracellular survival. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:175–188. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conlan J W, North R J. Early pathogenesis of infection in the liver with the facultative intracellular bacteria Listeria monocytogenes, Francisella tularensis, and Salmonella typhimurium involves lysis of infected hepatocytes by leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1992;60:5164–5171. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5164-5171.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conner C P, Heithoff D M, Julio S M, Sinsheimer R L, Mahan M J. Differential patterns of acquired virulence genes distinguish Salmonella strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4642–4645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deiwick J, Nikolaus T, Shea J E, Gleeson C, Holden D W, Hensel M. Mutations in Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI2) genes affecting transcription of SPI1 genes and resistance to antimicrobial agents. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4775–4780. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4775-4780.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Escher A, O'Kane D J, Lee J, Szalay A A. Bacterial luciferase alpha-beta fusion protein is fully active as a monomer and highly sensitive in vivo to elevated temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6528–6532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fields P I, Swanson R V, Haidaris C G, Heffron F. Mutants of Salmonella typhimurium that cannot survive within the macrophage are avirulent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5189–5193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fierer J, Eckmann L, Fang F, Pfeifer C, Finlay B B, Guiney D. Expression of the Salmonella virulence plasmid gene spvB in cultured macrophages and nonphagocytic cells. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5231–5236. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5231-5236.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francis K P, Taylor P D, Inchley C J, Gallagher M P. Identification of the ahp operon of Salmonella typhimurium as a macrophage-induced locus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4046–4048. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.4046-4048.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frost A J, Bland A P, Wallis T S. The early dynamic response of the calf ileal epithelium to Salmonella typhimurium. Vet Pathol. 1997;34:369–386. doi: 10.1177/030098589703400501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galyov E E, Wood M W, Rosqvist R, Mullan P B, Watson P R, Hedges S, Wallis T S. A secreted effector protein of Salmonella dublin is translocated into eukaryotic cells and mediates inflammation and fluid secretion in infected ileal mucosa. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:903–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22a.GSC Salmonella Sequencing Project 23 June 1999, revision date. [Online.] http://www.genome.wustl.edu/gsc/bacterial/salmonella.shtml. Genome Sequencing Center, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Mo. [15 September 1999, last date accessed.]

- 23.Guzzo A, DuBow M S. Construction of stable, single-copy luciferase gene fusions in Escherichia coli. Arch Microbiol. 1991;156:444–448. doi: 10.1007/BF00245390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heithoff D M, Conner C P, Hanna P C, Julio S M, Hentschel U, Mahan M J. Bacterial infection as assessed by in vivo gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:934–939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heithoff D M, Conner C P, Mahan M J. Dissecting the biology of a pathogen during infection. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:509–513. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hensel M, Shea J E, Raupach B, Monack D, Falkow S, Gleeson C, Kubo T, Holden D W. Functional analysis of ssaJ and the ssaK/U operon, 13 genes encoding components of the type III secretion apparatus of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:155–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3271699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoiseth S K, Stocker B A. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature. 1981;291:238–239. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong K H, Miller V L. Identification of a novel Salmonella invasion locus homologous to Shigella ipgDE. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1793–1802. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1793-1802.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu H S. Pathogenesis and immunity in murine salmonellosis. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:390–409. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.390-409.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen V B, Harty J T, Jones B D. Interactions of the invasive pathogens Salmonella typhimurium, Listeria monocytogenes, and Shigella flexneri with M cells and murine Peyer's patches. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3758–3766. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3758-3766.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leung K Y, Finlay B B. Intracellular replication is essential for the virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11470–11474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindgren S W, Stojiljkovic I, Heffron F. Macrophage killing is an essential virulence mechanism of Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4297–4201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahan M J, Tobias J W, Slauch J M, Hanna P C, Collier R J, Mekalanos J J. Antibiotic-based selection for bacterial genes that are specifically induced during infection of a host. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:669–673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meighen E A. Molecular biology of bacterial bioluminescence. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:123–142. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.1.123-142.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller J F, Mekalanos J J, Falkow S. Coordinate regulation and sensory transduction in the control of bacterial virulence. Science. 1989;243:916–922. doi: 10.1126/science.2537530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Motulsky H. Intuitive biostatistics. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mounier J, Bahrani F K, Sansonetti P J. Secretion of Shigella flexneri Ipa invasins on contact with epithelial cells and subsequent entry of the bacterium into cells are growth stage dependent. Infect Immun. 1997;65:774–782. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.774-782.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norris F A, Wilson M P, Wallis T S, Galyov E E, Majerus P W. SopB, a protein required for virulence of Salmonella dublin, is an inositol phosphate phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14057–14059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ochman H, Gerber A S, Hartl D L. Genetic applications of an inverse polymerase chain reaction. Genetics. 1988;120:621–623. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.3.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Penheiter K L, Mathur N, Giles D, Fahlen T, Jones B D. Non-invasive Salmonella typhimurium mutants are avirulent because of an inability to enter and destroy M cells of ileal Peyer's patches. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:697–709. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3741745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfeifer C G, Finlay B B. Monitoring gene expression of Salmonella inside mammalian cells: comparison of luciferase and β-galactosidase fusion systems. J Microbiol Methods. 1995;24:155–164. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reed L J, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhen M, Riikonen P, Taira S. Transcriptional regulation of Salmonella enterica virulence plasmid genes in cultured macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:45–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richter-Dahlfors A, Buchan A, Finlay B B. Murine salmonellosis studied by confocal microscopy: Salmonella typhimurium resides intracellularly inside macrophages and exerts a cytotoxic effect on phagocytes in vivo. J Exp Med. 1997;186:569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 45a.The Sanger Centre. 23 June 1999, revision date. [Online.] Sanger Centre, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge, United Kingdom. http://www.sanger.ac.uk. [15 September 1999, last date accessed.]

- 46.Sternberg N L, Maurer R. Bacteriophage-mediated generalized transduction in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:18–42. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sukupolvi S, Edelstein A, Rhen M, Normark S J, Pfeifer J D. Development of a murine model of chronic Salmonella infection. Infect Immun. 1997;65:838–842. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.838-842.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang P, Foubister V, Pucciarelli M G, Finlay B B. Methods to study bacterial invasion. J Microbiol Methods. 1993;18:227–240. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Triglia T, Peterson M G, Kemp D J. A procedure for in vitro amplification of DNA segments that lie outside the boundaries of known sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:8186. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.16.8186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valdivia R H, Falkow S. Bacterial genetics by flow cytometry: rapid isolation of Salmonella typhimurium acid-inducible promoters by differential fluorescence induction. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:367–378. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valdivia R H, Falkow S. Fluorescence-based isolation of bacterial genes expressed within host cells. Science. 1997;277:2007–2011. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watson P R, Paulin S M, Bland A P, Jones P W, Wallis T S. Characterization of intestinal invasion by Salmonella typhimurium and Salmonella dublin and effect of a mutation in the invH gene. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2743–2754. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2743-2754.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wood M W, Jones M A, Watson P R, Hedges S, Wallis T S, Galyov E E. Identification of a pathogenicity island required for Salmonella enteropathogenicity. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:883–891. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]