Abstract

Bone disease is a serious problem for many patients, often causing pathological bone fractures. A spinal collapse is a condition that affects the quality of life. It is the most frequent feature of multiple myeloma (MM), used in establishing the diagnosis and the need to start treatment. Because of these complications, imaging plays a vital role in the diagnosis and workup of myeloma patients.

For many years, conventional radiography has been considered the gold standard for detecting bone lesions. The main reasons are the wide availability, low cost, the relatively low radiation dose and the ability of this imaging method to cover the entire bone system. Because of its incapacity to evaluate the response to therapy, more sophisticated techniques such as whole-body low-dose computed tomography (WBLDCT), whole-body magnetic resonance imaging, and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) are used. In this review, some of the advantages, indications and applications of the three techniques in managing patients with MM will be discussed. The European Myeloma Network guidelines have recommended WBLDCT as the imaging modality of choice for the initial assessment of MM-related lytic bone lesions. Magnetic resonance imaging is the gold-standard imaging modality for the detection of bone marrow involvement. One of the modern imaging methods and PET/CT can provide valuable prognostic data and is the preferred technique for assessing response to therapy.

Keywords: multiple myeloma, skeletal survey, MRI, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT), whole-body low-dose computed tomography (WBLDCT)

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant hematologic disorder characterized by clonal expansion of malignant plasma cells that accumulate in the marrow leading to anemia and associated cytopenia, hypogammaglobulinemia, osteolytic bone disease, hypercalcemia, and renal dysfunction [1–4].

MM is the second most frequent malignancy of the blood, which accounts for ~1% of neoplastic diseases and 13% of hematologic cancers. During the last decades, MM has caused an increasing number of deaths globally [5].

Myeloma diagnostic criteria must evidence either 10% or more of clonal bone marrow plasma cell of biopsy-proven bony or extramedullary plasmacytoma and the presence of one or more myeloma defining events, the CRAB criteria: hypercalcemia, renal failure, anemia, lytic bone lesions, and three specific biomarkers of malignancy: clonal bone marrow plasma cell either 60% or more, the serum-free light chain of 100 or higher, and at least one focal lesion on MRI scans [2]. One of the criteria of active myeloma is represented by bone lesions, which can often lead to osteopenia to bone fractures in the pathological bone [2,6,7].

In multiple myeloma (MM), the patient’s quality of response to treatment, particularly the achievement of durable complete response, is related to improved progression-free survival and overall survival [8,9]. The introduction of new treatment strategies owing to the approval of several molecules in the last decade enabled a significant increase in survival of patients with MM [9,10]. In this context, imaging presents a vital role in the diagnosis and workup of myeloma patients. The detection of lytic/focal bone disease is part of the criteria for starting therapy and carries prognostic significance. Imaging may be the only way of assessing the extent of disease, response to therapy, or disease relapse [11]. Early detection of myeloma complications such as osteoporosis and compression fractures is valuable to help improve morbidity in myeloma patients [12].

Skeletal X-ray

The guidelines of the International Working Group on Myeloma (IMWG) highlight the presence of skeletal lytic lesions on skeletal X-rays as one of the criteria for classifying the symptomatic patient with multiple myeloma [13,14]. In treating patients with MM, whole-body planar radiography has long been considered the gold standard for detecting bone damage [9,15]. Skeletal radiographs have been widely used due to their availability, having the ability to highlight lytic lesions and pathological fractures present in MM [16].

Skeletal lesions can be seen in the spine (Figure 1), pelvis, ribs, sternum, skull, and proximal appendicular skeleton. Although rare, the more distal appendicular skeleton may be affected. Skeletal radiography could be described: solitary lesion (plasmacytoma), diffuse skeletal damage (myelomatosis), diffuse skeletal osteopenia, and sclerosing myeloma [17,18]. Bone lesions in myeloma patients usually appear in the flat bones of the skull and pelvis, as perforated ovoid lytic areas without sclerosis of the surrounding bone. Almost 80% of myeloma patients have skeletal involvement, which most commonly affects the following sites: 65% vertebrae, 45% ribs, 40% skull, 40% shoulders, 30% pelvis, and 25% long bones. Detectable radiographic lesions are rare in the elbows and knees [19–22].

Figure 1.

Osteolytic lesion of the spine T2–T3 – anterior view. Medical Radiology-Imaging department of the “Prof. Dr. Ion Chiricuta” Oncological Institute archive.

According to IMWG guidelines, X-ray should include a posteroanterior view of the chest, anteroposterior and lateral view of the spine, humerus, femur, skull, and anteroposterior view the pelvis [19]. X-ray is the imaging method used to detect lytic bone disease because it is widely available, easy to perform and report, it has a low cost, relatively low radiation dose, and can cover almost the entire bone system [11,23]. Although conventional radiography has historically been the standard imaging technique for many years, it has limited sensitivity and very low accuracy rates [11]. Detection of lytic bone disease is demonstrated only when 30–50% of the trabecular bone is lost [11,24].

X-rays show low specificity, especially in anatomically complex areas, such as the axial skeleton and thoracic cage, or patients with low bone mineral density [16]. Detection of lytic lesions, especially in the axial skeleton, is difficult due to overlapping structures. False-positive results may occur in the pelvis due to overlapping bowel loops that mimic the disease. Thus, 30%–70% of the results are false negative [16,24]. Limitations of radiography include prolonged study time, difficulty assessing certain areas, such as the pelvis and spine, difficulty distinguishing vertebral fractures secondary to benign osteoporosis from those present in MM, or lack of ability to assess response to treatment [11,17,25]. The long time spent by the patient on the examination table and the poor tolerance of elderly patients with severe pain and lytic bone disease is another common disadvantage. These conditions make it difficult to place these patients in the proper position [24].

The limitations of conventional radiography have led to an increase in the use of more advanced imaging methods. For these reasons, after the publication of the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines in 2017, conventional radiography is used to diagnose and stage multiple myeloma only if CT scanning is not available [19].

Whole-body low dose CT (WBLDCT)

WBLDCT is often used, replacing conventional radiography, due to its greater sensitivity for detecting bone lesions and diagnosing extraosseous lesions [23,26]. The European Myeloma Network (EMN) and the European Society’s Guide to Medical Oncology (ESMO) has recommended whole-body low dose CT (WBLDCT) as the imaging method of choice for the initial assessment of MM-related lytic bone damage [27].

Advances in CT technology allow the use of low-dose CT protocols. Introduced by Horger and colleagues, low-dose CT protocols aim to preserve sensitivity and imaging details [11]. WBLDCT allows the assessment of early bone marrow abnormalities in the long bones, which only become visible belatedly on conventional radiography, thus excluding false positive or negative results. Bone marrow myeloma lesions are generally hyperdense in adults, contrasting with healthy yellow marrow, which is usually hypodense [19,28,29]. WBLDCT describes the three main features of myeloma: lytic bone destruction of the entire skeleton, diffuse involvement of the bone marrow, especially in the appendicular skeleton, as osteopenia and osteoporosis, and extraosseous localization [30]. The inclusion of osteolytic lesions found only on CT was the result of several studies showing that CT has increased sensitivity compared to CSS to detect bone lesions in multiple myeloma (Figure 2) [31,32].

Figure 2.

Osteolytic lesion located in the sternal body. Medical-Imaging Radiology department of the “Prof. Dr. Ion Chiricuta” Oncological Institutearchive.

WBLDCT has significant advantages as a first-line imaging modality for the evaluation of bone disease in patients with MM. It is more sensitive than the conventional skeletal study for the detection of osteolysis, and the lytic lesions detected by WBLDCT justify the initiation of treatment in asymptomatic patients [24,31,33]. Moreover, it highlights concomitant extraosseous lesions, thus helping to define assessment algorithms for myeloma patients in various clinical conditions such as staging, follow-up, and assessment of spinal stability [30,34].

It is widely available, relatively inexpensive, easy to perform, with a scan time of less than one minute, superior image quality without the need to use contrast agents due to the intrinsic contrast of the bone [31,35]. For a good diagnosis and qualitative images, the selection of optimal imaging parameters and the correct positioning of the patient is mandatory while maintaining a low but effective radiation dose administered to the patient [24].

WBLDCT should be performed with a multidetector CT scanner with at least 16 rows of detectors, with a visual field from the skull to the proximal tibial metaphysis. It is not necessary to prepare the patient before the examination and the administration of contrast agents. The correct position of the patient is horizontal, on the table, with the arms positioned so as to include the shoulders in the field of view, without producing changes that could significantly degrade the image quality in the clinically relevant anatomical regions [31].

Positron emission tomography with computed tomography 18F-deoxy-fluoro glucose (FDG-PET/CT)

FDG-PET/CT is a non-invasive functional imaging modality of the whole body. It has been included in the 2019 International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) recommendations as a feasible imaging strategy for the initial workup of newly diagnosed MM. FDG-PET/CT detects myeloma-related lesions with excellent sensitivity and specificity with the advantage of carrying out both bone and extra-bone exploration in a single examination [36–38].

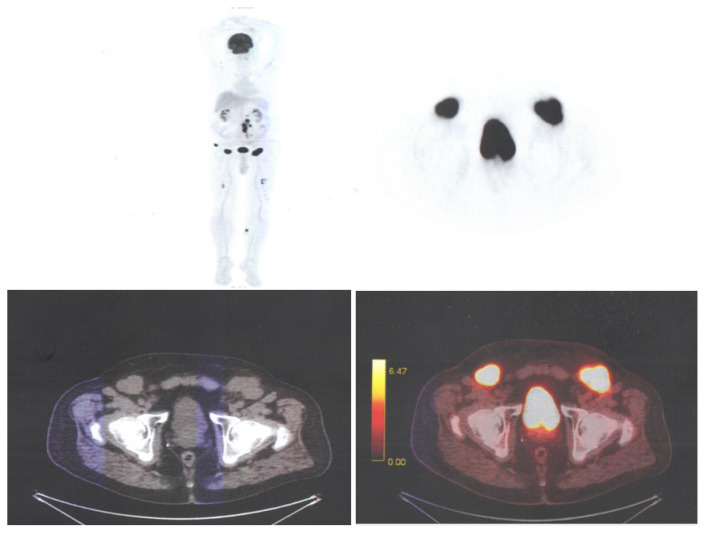

The most significant advantage of 18F-FDG PET/CT is its ability to accurately assess the severity of the disease and to distinguish between active metabolic lesions and inactive lesions [39–41]. PET/CT reveals multiple osteolytic lesions throughout the skeleton (Figure 3) (skull, ribs, upper limbs, femurs, pelvis and spine), with a short image acquisition time with 3-D tomographs, important in patients with fractures or bone pain [42,43].

Figure 3.

Multiple subcutaneous lesions in the left iliac region and multiple metabolically active lytic bone lesions: femur, iliac bone, skull, spine. Medical Radiology-Imaging department of the “Prof. Dr. Ion Chiricuta” Oncological Institute archive.

The performance of FDG-PET/CT in detecting MM is excellent, with a sensitivity of around 90% for the detection of myeloma lesions, and specificity was varying from 70 to 100% in several studies, with greater sensitivity than whole-body conventional radiography and comparable sensitivity with pelvic-spinal MRI. PET/CT detects more osseous myeloma manifestations in 40%–60% of cases as compared to conventional radiography and detects lesions in patients with false-negative conventional radiography results [23,36,44].

PET/CT is used to evaluate glucose metabolism activity and yields biochemical and functional information, in contrast to the solely anatomic data obtained with CT and MRI conventional sequences. The total duration of the procedure is approximately 80–90 minutes, and the field of view should include the region spanning from at least the skull to the femora, including the upper limbs. PET/CT, similar to WBLD CT and WB MRI, is a good option for detecting bone lesions in MM. The results of several studies have shown the usefulness of PET/CT, with high sensitivity and specificity reported in the detection of bone damage and extramedullary involvement [45–49].

In a prospective study designed to compare the 18F-FDG PET/CT method with whole-body skeletal X-ray survey (WBXR) and MRI of the spine and pelvis, 18F-FDG PET/CT was superior to WBXR for detecting bone lesions, while MRI was more sensitive than 18F-FDG PET/CT for the detection of diffuse plasma infiltration of bone marrow. However, in one third of patients, 18F-FDG PET/CT demonstrated bone changes in sites outside the visual field of MRI. In a further study, 18F-FDG PET/CT and MRI of the spine were equally effective in detecting focal lesions.

A systematic review of 18 studies comparing 18F-FDG PET/CT with WBXR, or MRI, confirmed that MRI is the gold standard technique for assessing diffuse involvement of the bone marrow, while 18F-FDG PET/CT is more sensitive than WBXR for bone damage detection [39,50].

Rasche et al. recently published a study that examined the FDG-PET/CT false-negative rate within a cohort of 227 newly diagnosed MM patients and identified the tumor-intrinsic parameters associated with this pattern. While 11% of patients were FDG-PET/CT negative, and this was not linked to the degree of bone marrow plasma cell infiltration or plasma cell proliferation. They then showed a statistically significant decrease in hexokinase-2 expression in this subset, an enzyme that catalyzes the first phosphorylation step of glycolysis, therefore providing a mechanistic reason. More recently, Abe et al. investigated the prognostic impact of low hexokinase-2 expression associated with false-negative FDG-PET in MM patients. Ninety patients with newly diagnosed MM were enrolled in this retrospective study, and the authors confirmed that an FDG-PET negativity rate of 12% was associated with low expression of hexokinase 2 [51–54].

The images obtained by PET/CT 18F-FDG can provide morphological and metabolic findings being a valuable tool in the differential diagnosis of osteolytic lesions. However, PET-CT 18F-FDG is recommended to differentiate active myeloma from smoky myeloma, if WBXR is negative and whole body MRI is not available [52,55–58].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard imaging technique for assessing bone marrow involvement in myeloma [59,60]. MRI is a sensitive and specific imaging method for detecting bone marrow infiltration before the mineralized bone is destroyed. The presence of more than one focal lesion of at least 5 mm is sufficient to define MM [61], being considered asymptomatic disease requiring treatment according to the International Working Group on Myeloma (IMWG) [59,62–64].

MRI has a higher specificity and sensitivity in detecting focal lesions in multiple myeloma compared to plain radiography, computed tomography, and fluorescence positron emission tomography. Because of its high sensitivity in revealing bone marrow involvement, MRI is now used for the discrimination between asymptomatic/smoldering and symptomatic multiple myeloma. Moreover, MRI is the modality of choice for differentiating benign from malignant vertebral fractures, and for assessing painful complications and bone marrow compression. MRI is useful because of its superior soft-tissue contrast resolution [9].

A whole-body MRI is performed when the CT is negative or inconclusive. It provides prognostic information because more than one focal lesion is associated with an increased risk of disease progression. It can detect myeloma infiltration into the bone marrow before the development of cortical bone destruction [9,65–67]. A study of 611 patients showed that MRI detected more focal lesions than plain radiography, which led to an increase in survival. Comparing WBLDCT and WB-MRI, MRI detected the highest number of bone lesions [11]. MRI is based on examining the tissue composition in terms of water and fat content and has the highest sensitivity in detecting bone marrow infiltration by myeloma cells without radiation exposure [27,68,69].

The advantages of MRI are due to the fact that bone marrow infiltration can be visualized even before the appearance of lytic changes, thus demonstrating the superiority over conventional radiography. MRI provides improved detection of lesions in the spine (Figure 4), pelvis, sternum, skull and scapulae. MRI is similar to CT and PET/CT, but individual studies have shown advantages over MRI. MRI is more suitable than PET/CT to detect diffuse bone marrow damage. Another advantage of MRI is the ability to differentiate uncomplicated osteoporotic fractures from pathological fractures based on the appearance of the bone marrow and is well suited for visualizing extramedullary myeloma [17,33,70–73].

Figure 4.

Osteolytic lesion in the lumbar spinal canal, posterior to the L4 vertebral body. Medical Radiology-Imaging department of the “Prof. Dr. Ion Chiricuta” Oncological Institute archive.

In addition to the known advantages of MRI, it also has some disadvantages: limited availability, high costs, and long examination time (approximately 45–60 minutes). The application of the method requires an increased caution in the case of patients with metal implants or at risk of developing nephrogenic systematic fibrosis. Also, in purely morphological sequences, it is often impossible to distinguish between vital lesions and non-vital scars because some of the lesions disappear incompletely or only very slowly [17,23,74]. Not all patients can tolerate MRI, especially those suffering from pain or claustrophobia, but with mild sedation and effective analgesia, most patients can be successfully scanned [11]. Several studies have shown that MRI, both axially and the whole body, is more sensitive than WBXR to detect bone involvement in MM, providing greater diagnostic accuracy [27].

Lecouvet et al. compared axial MRI with WBXR and found that MRI had a higher detection rate, but that WBXR was generally higher because it showed more appendicular lesions. When performing a whole-body examination that includes at least the proximal appendicular skeleton, MRI has a higher detection rate than WBXR. The results have showed that approximately 10% of patients have lesions exclusively outside the axial skeleton. Baur Melnyk et al. compared whole-body MRI with whole CT and found that MRI revealed a more widespread disease in half of the patients [18,75].

Conclusions

Imaging plays an essential role in diagnosing patients with multiple myeloma because detection for bone lesions has prognostic significance and is part of the criteria for starting therapy.

Conventional radiography has long been considered the gold standard for detecting bone damage. Because of the disadvantages of its use, conventional radiography has been replaced by new imaging methods, which include Whole-body low dose CT (WBLDCT), Positron emission tomography with computed tomography 18F- deoxy-fluoro glucose (FDG-PET/CT), and Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

As a modern imaging technique, WBLDCT offers superior image quality, is widely available, has high sensitivity, is relatively inexpensive, and easy to perform with a short scanning time.

PET/CT has been compared to other imaging modalities and is superior to WBXR and comparable to MRI. The sensitivity of PET/CT for detecting focal bone lesions is similar to MRI.

MRI is more suitable than PET/CT to detect diffuse bone marrow damage. An advantage of MRI is the ability to differentiate uncomplicated osteoporotic fractures from pathological fractures, suitable for visualizing extramedullary myeloma.

References

- 1.Leydon P, O’Connell M, Greene D, Curran K. Automatic bone marrow segmentation for PETCT imaging in multiple myeloma. Phys Med. 2016;32:242. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaudio A, Xourafa A, Rapisarda R, Zanoli L, Signorelli SS, Castellino P. Hematological Diseases and Osteoporosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:3538. doi: 10.3390/ijms21103538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colucci PG, Schweitzer AD, Saab J, Lavi E, Chazen JL. Imaging findings of spinal brown tumors: a rare but important cause of pathologic fracture and spinal cord compression. Clin Imaging. 2016;40:865–869. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gouliamos A, Andreou J, Kosmidis P. Imaging in Clinical Oncology. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2875-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang S, Xu L, Feng J, Liu Y, Liu L, Wang J, et al. Prevalence and Incidence of Multiple Myeloma in Urban Area in China: A National Population-Based Analysis. Front Oncol. 2020;9:1513. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auzina D, Erts R, Lejniece S. Prognostic value of the bone turnover markers in multiple myeloma. Exp Oncol. 2017;39:53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao R, Miller JA, Margetis K, Lubelski D, Lieberman IH, Benzel EC, et al. Radiographic progression of vertebral fractures in patients with multiple myeloma. Spine J. 2016;16:822–832. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dutoit JC, Claus E, Offner F, Noens L, Delanghe J, Verstraete KL. Combined evaluation of conventional MRI, dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI and diffusion weighted imaging for response evaluation of patients with multiple myeloma. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulé S, Reizine E, Blanc-Durand P, Baranes L, Zerbib P, Burns R, et al. Whole-Body Functional MRI and PET/MRI in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:3155. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillengass J, Usmani S, Rajkumar SV, Durie BGM, Mateos MV, Lonial S, et al. International myeloma working group consensus recommendations on imaging in monoclonal plasma cell disorders. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:e302–e312. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30309-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barwick T, Bretsztajn L, Wallitt K, Amiras D, Rockall A, Messiou C. Imaging in myeloma with focus on advanced imaging techniques. Br J Radiol. 2019;92:20180768. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20180768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansford BG, Silbermann R. Advanced Imaging of Multiple Myeloma Bone Disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:436. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallicchio R, Nardelli A, Calice G, Guarini A, Guglielmi G, Storto G. F-18 FDG PET/CT and F-18 FLT PET/CT as predictors of outcome in patients with multiple myeloma. A pilot study. Eur J Radiol. 2021;136:109564. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.109564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Czyż J, Małkowski B, Jurczyszyn A, Grząśko N, Łopatto R, Olejniczak M, et al. 18F-fluoro-ethyl-tyrosine (18F-FET) PET/CT as a potential new diagnostic tool in multiple myeloma: a preliminary study. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2019;23:23–31. doi: 10.5114/wo.2019.83342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zambello R, Crimì F, Lico A, Barilà G, Branca A, Guolo A, et al. Whole-body low-dose CT recognizes two distinct patterns of lytic lesions in multiple myeloma patients with different disease metabolism at PET/MRI. Ann Hematol. 2019;98:679–689. doi: 10.1007/s00277-018-3555-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simeone FJ, Harvey JP, Yee AJ, O’Donnell EK, Raje NS, Torriani M, et al. Value of low-dose whole-body CT in the management of patients with multiple myeloma and precursor states. Skeletal Radiol. 2019;48:773–779. doi: 10.1007/s00256-018-3066-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amos B, Agarwal A, Kanekar S. Imaging of Multiple Myeloma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30:843–865. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caers J, Withofs N, Hillengass J, Simoni P, Zamagni E, Hustinx R, et al. The role of positron emission tomography-computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis and follow up of multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2014;99:629–637. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.091918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Giuliano F, Picchi E, Muto M, Calcagni A, Ferrazzoli V, Da Ros V, et al. Radiological imaging in multiple myeloma: review of the state-of-the-art. Neuroradiology. 2020;62:905–923. doi: 10.1007/s00234-020-02417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portet M, Owens E, Howlett D. The use of whole-body MRI in multiple myeloma. Clin Med (Lond) 2019;19:355–356. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.19-4-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zamagni E, Cavo M, Fakhri B, Vij R, Roodman D. Bones in Multiple Myeloma: Imaging and Therapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:638–646. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_205583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Healy CF, Murray JG, Eustace SJ, Madewell J, O’Gorman PJ, O’Sullivan P. Multiple myeloma: a review of imaging features and radiological techniques. Bone Marrow Res. 2011;2011:583439. doi: 10.1155/2011/583439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derlin T, Bannas P. Imaging of multiple myeloma: Current concepts. World J Orthop. 2014;5:272–282. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ormond Filho AG, Carneiro BC, Pastore D, Silva IP, Yamashita SR, Consolo FD, et al. Whole-Body Imaging of Multiple Myeloma: Diagnostic Criteria. Radiographics. 2019;39:1077–1097. doi: 10.1148/rg.2019180096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jamet B, Bailly C, Carlier T, Touzeau C, Nanni C, Zamagni E, et al. Interest of Pet Imaging in Multiple Myeloma. Front Med (Lausanne) 2019;6:69. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gavriatopoulou M, Boultadaki A, Koutoulidis V, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Bourgioti C, Malandrakis P, et al. The Role of Low Dose Whole Body CT in the Detection of Progression of Patients with Smoldering Multiple Myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10:93. doi: 10.1038/s41408-020-00360-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zamagni E, Tacchetti P, Cavo M. Imaging in multiple myeloma: How? When? Blood. 2019;133:644–651. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-08-825356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubini G, Niccoli-Asabella A, Ferrari C, Racanelli V, Maggialetti N, Dammacco F. Myeloma bone and extra-medullary disease: Role of PET/CT and other whole-body imaging techniques. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;101:169–183. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hillengass J, Moulopoulos LA, Delorme S, Koutoulidis V, Mosebach J, Hielscher T, et al. Whole-body computed tomography versus conventional skeletal survey in patients with multiple myeloma: a study of the International Myeloma Working Group. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7:e599. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2017.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ippolito D, Besostri V, Bonaffini PA, Rossini F, Di Lelio A, Sironi S. Diagnostic value of whole-body low-dose computed tomography (WBLDCT) in bone lesions detection in patients with multiple myeloma (MM) Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:2322–2327. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moulopoulos LA, Koutoulidis V, Hillengass J, Zamagni E, Aquerreta JD, Roche CL, et al. Recommendations for acquisition, interpretation and reporting of whole body low dose CT in patients with multiple myeloma and other plasma cell disorders: a report of the IMWG Bone Working Group. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8:95. doi: 10.1038/s41408-018-0124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambert L, Ourednicek P, Meckova Z, Gavelli G, Straub J, Spicka I. Whole-body low-dose computed tomography in multiple myeloma staging: Superior diagnostic performance in the detection of bone lesions, vertebral compression fractures, rib fractures and extraskeletal findings compared to radiography with similar radiation exposure. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:2490–2494. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gariani J, Westerland O, Natas S, Verma H, Cook G, Goh V. Comparison of whole body magnetic resonance imaging (WBMRI) to whole body computed tomography (WBCT) or 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT (18F-FDG PET/CT) in patients with myeloma: Systematic review of diagnostic performance. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;124:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hemke R, Yang K, Husseini J, Bredella MA, Simeone FJ. Organ dose and total effective dose of whole-body CT in multiple myeloma patients. Skeletal Radiol. 2020;49:549–554. doi: 10.1007/s00256-019-03292-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chrzan R, Jurczyszyn A, Urbanik A. Whole-Body Low-Dose Computed Tomography (WBLDCT) in Assessment of Patients with Multiple Myeloma - Pilot Study and Standard Imaging Protocol Suggestion. Pol J Radiol. 2017;82:356–363. doi: 10.12659/PJR.901742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michaud-Robert AV, Jamet B, Bailly C, Carlier T, Moreau P, Touzeau C, et al. FDG-PET/CT, a Promising Exam for Detecting High-Risk Myeloma Patients? Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1384. doi: 10.3390/cancers12061384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi MES, Mosci C, Souza EM, Brunetto SQ, de Souza C, Pericole FV, et al. Computed tomography-based skeletal segmentation for quantitative PET metrics of bone involvement in multiple myeloma. Nucl Med Commun. 2020;41:377–382. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000001165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Madduri D, Barlogie B. PET-Computed Tomography in Myeloma: Current Overview and Future Directions. PET Clin. 2019;14:411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.cpet.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haghighat S. The Role of 18F-FDG-PET/CT Scan in the Management of Multiple Myeloma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;5:119–123. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vicentini JRT, Bredella MA. Role of FDG PET in the staging of multiple myeloma. Skeletal Radiol. 2022 Jan;51(1):31–41. doi: 10.1007/s00256-021-03771-2. Epub 2021 Apr 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zamagni E, Nanni C, Gay F, Pezzi A, Patriarca F, Bellò M, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT focal, but not osteolytic, lesions predict the progression of smoldering myeloma to active disease. Leukemia. 2016;30:417–422. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nanni C, Zamagni E, Versari A, Chauvie S, Bianchi A, Rensi M, et al. Image interpretation criteria for FDG PET/CT in multiple myeloma: a new proposal from an Italian expert panel. IMPeTUs (Italian Myeloma criteria for PET USe) Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:414–421. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dammacco F, Rubini G, Ferrari C, Vacca A, Racanelli V. 18F-FDG PET/CT: a review of diagnostic and prognostic features in multiple myeloma and related disorders. Clin Exp Med. 2015;15:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s10238-014-0308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paternain A, García-Velloso MJ, Rosales JJ, Ezponda A, Soriano I, Elorz M, et al. The utility of ADC value in diffusion-weighted whole-body MRI in the follow-up of patients with multiple myeloma. Correlation study with 18F-FDG PET-CT. Eur J Radiol. 2020;133:109403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.109403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lecouvet FE, Boyadzhiev D, Collette L, Berckmans M, Michoux N, Triqueneaux P, et al. MRI versus 18F-FDG-PET/CT for detecting bone marrow involvement in multiple myeloma: diagnostic performance and clinical relevance. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:1927–1937. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06469-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seval GC, Ozkan E, Beksac M. PET with Fluorodeoxyglucose F 18/Computed Tomography as a Staging Tool in Multiple Myeloma. PET Clin. 2019;14:369–381. doi: 10.1016/j.cpet.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deng S, Zhang B, Zhou Y, Xu X, Li J, Sang S, et al. The Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in Multiple Myeloma Staging according to IMPeTUs: Comparison of the Durie-Salmon Plus and Other Staging Systems. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2018;2018:4198673. doi: 10.1155/2018/4198673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y, Liu J, Huang B, Chen M, Diao X, Li J. Application of PET/CT in treatment response evaluation and recurrence prediction in patients with newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:25637–25649. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferrarazzo G, Chiola S, Capitanio S, Donegani MI, Miceli A, Raffa S, et al. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Imaging of Multiple Myeloma in a Post-Treatment Setting. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:230. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11020230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cavo M, Terpos E, Nanni C, Moreau P, Lentzsch S, Zweegman S, et al. Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis and management of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell disorders: a consensus statement by the International Myeloma Working Group. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e206–e217. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jamet B, Zamagni E, Nanni C, Bailly C, Carlier T, Touzeau C, et al. Functional Imaging for Therapeutic Assessment and Minimal Residual Disease Detection in Multiple Myeloma. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:5406. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li X, Wu N, Zhang W, Liu Y, Ming Y. Differential diagnostic value of (18)F-FDG PET/CT in osteolytic lesions. J Bone Oncol. 2020;24:100302. doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2020.100302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ulaner GA, Landgren CO. Current and potential applications of positron emission tomography for multiple myeloma and plasma cell disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2020;33:101148. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2020.101148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abe Y, Ikeda S, Kitadate A, Narita K, Kobayashi H, Miura D, et al. Low hexokinase-2 expression-associated false-negative 18F-FDG PET/CT as a potential prognostic predictor in patients with multiple myeloma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:1345–1350. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-04312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lapa C, Schreder M, Schirbel A, Samnick S, Kortüm KM, Herrmann K, et al. [(68)Ga]Pentixafor-PET/CT for imaging of chemokine receptor CXCR4 expression in multiple myeloma - Comparison to [18F]FDG and laboratory values. Theranostics. 2017;7:205–212. doi: 10.7150/thno.16576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mesguich C, Hulin C, Lascaux A, Bordenave L, Marit G, Hindié E. Choline PET/CT in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1394. doi: 10.3390/cancers12061394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maggialetti N, Ferrari C, Nappi AG, Quinto A, Rossini B, Zappia M, et al. Is whole body low dose CT still necessary in the era of 18F-FDG PET/CT for the assessment of bone disease in multiple myeloma patients? Hell J Nucl Med. 2020;23:264–271. doi: 10.1967/s002449912206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moon SH, Choi WH, Yoo IR, Lee SJ, Paeng JC, Jeong SY, et al. Prognostic Value of Baseline (18)F-Fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT in Patients with Multiple Myeloma: A Multicenter Cohort Study. Korean J Radiol. 2018;19:481–488. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2018.19.3.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh S, Pilavachi E, Dudek A, Bray TJP, Latifoltojar A, Rajesparan K, et al. Whole body MRI in multiple myeloma: Optimising image acquisition and read times. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0228424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hillengass J, Merz M, Delorme S. Minimal residual disease in multiple myeloma: use of magnetic resonance imaging. Semin Hematol. 2018;55:19–21. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karampinos DC, Ruschke S, Dieckmeyer M, Diefenbach M, Franz D, Gersing AS, et al. Quantitative MRI and spectroscopy of bone marrow. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2018;47:332–353. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koutoulidis V, Papanikolaou N, Moulopoulos LA. Functional and molecular MRI of the bone marrow in multiple myeloma. Br J Radiol. 2018;91:20170389. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20170389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Messiou C, Kaiser M. Whole body diffusion weighted MRI--a new view of myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2015;171:29–37. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rasch S, Lund T, Asmussen JT, Lerberg Nielsen A, Faebo Larsen R, Østerheden Andersen M, et al. Multiple Myeloma Associated Bone Disease. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:2113. doi: 10.3390/cancers12082113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park HY, Kim KW, Yoon MA, Lee MH, Chae EJ, Lee JH, et al. Role of whole-body MRI for treatment response assessment in multiple myeloma: comparison between clinical response and imaging response. Cancer Imaging. 2020;20:14. doi: 10.1186/s40644-020-0293-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mosebach J, Thierjung H, Schlemmer HP, Delorme S. Multiple Myeloma Guidelines and Their Recent Updates: Implications for Imaging. Rofo. 2019;191:998–1009. doi: 10.1055/a-0897-3966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Torres C, Hammond I. Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Differentiation of Osteoporotic Fractures From Neoplastic Metastatic Fractures. J Clin Densitom. 2016;19:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lecouvet F, Boyadzhiev D, Collette L, Berckmans M, Michoux N, Triqueneaux P, et al. Bone marrow MRI versus 18F-FDG-PET/CT for detecting multiple myeloma lesions: diagnostic performance and clinical relevance. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19:e35–e6. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06469-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Amini B, Yellapragada S, Shah S, Rohren E, Vikram R. State-of-the-Art Imaging and Staging of Plasma Cell Dyscrasias. Radiol Clin North Am. 2016;54:581–596. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Latifoltojar A, Hall-Craggs M, Rabin N, Popat R, Bainbridge A, Dikaios N, et al. Whole body magnetic resonance imaging in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: early changes in lesional signal fat fraction predict disease response. Br J Haematol. 2017;176:222–233. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Croft J, Riddell A, Koh DM, Downey K, Blackledge M, Usher M, et al. Inter-observer agreement of baseline whole body MRI in multiple myeloma. Cancer Imaging. 2020;20:48. doi: 10.1186/s40644-020-00328-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Messiou C, Hillengass J, Delorme S, Lecouvet FE, Moulopoulos LA, Collins DJ, et al. Guidelines for Acquisition, Interpretation, and Reporting of Whole-Body MRI in Myeloma: Myeloma Response Assessment and Diagnosis System (MY-RADS) Radiology. 2019;291:5–13. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019181949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hanrahan CJ, Christensen CR, Crim JR. Current concepts in the evaluation of multiple myeloma with MR imaging and FDG PET/CT. Radiographics. 2010;30:127–142. doi: 10.1148/rg.301095066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dutoit JC, Verstraete KL. MRI in multiple myeloma: a pictorial review of diagnostic and post-treatment findings. Insights Imaging. 2016;7:553–569. doi: 10.1007/s13244-016-0492-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Terpos E, Dimopoulos MA, Moulopoulos LA. The Role of Imaging in the Treatment of Patients With Multiple Myeloma in 2016. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:e407–e117. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_159074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]