Abstract

This study investigated the characteristics of humoral immune responses to Treponema denticola following primary infection, reinfection, and active immunization, as well as immune protection in mice. Primary infection with T. denticola induced a significant (400-fold) serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) response compared to that in control uninfected mice. The IgG response to reinfection was 20,000-fold higher than that for control mice and 10-fold higher than that for primary infection. Mice actively immunized with formalin-killed treponemes developed serum antibody levels seven- to eightfold greater than those in animals after primary infection. Nevertheless, mice with this acquired antibody following primary infection or active immunization demonstrated no significant alterations of lesion induction or decreased size of the abscesses following a challenge infection. Mice with primary infection developed increased levels of IgG3, IgG2b, and IgG2a antibodies, with IgG1 being lower than the other subclasses. Reinfected mice developed enhanced IgG2b, IgG2a, and IgG3 and less IgG1. In contrast, immunized mice developed higher IgG1 and lower IgG3 antibody responses to infection. These IgG subclass distributions indicate a stimulation of both Th1 and Th2 activities in development of the humoral immune response to infection and immunization. Our findings also demonstrated a broad antigen reactivity of the serum antibody, which was significantly increased with reinfection and active immunization. Furthermore, serum antibody was effective in vitro in immobilizing and clumping the bacteria but did not inhibit growth or passively prevent the treponemal infection. These observations suggest that humoral immune responses, as manifested by antibody levels, isotype, and antigenic specificity, were not capable of resolving a T. denticola infection.

Oral treponemes have been implicated as etiological agents of severe periodontal disease in adults. The oral spirochetes Treponema denticola, T. socranskii, T. pectinovorum, T. vincentii, T. maltophilum, T. medium, and T. amylovorum and the pathogen-related oral spirochetes have been found to be associated with human periodontal disease (3, 29, 38, 45, 46, 50, 54, 55), necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (33), acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (21), and human immunodeficiency virus-associated periodontal diseases (41). T. denticola has been the most extensively studied of the oral treponemes (18) and is the predominant spirochete identified within the gingival crevice and subgingival ecology of the developing periodontal pocket of various forms of periodontitis (44).

A limited group of human studies have investigated the characteristics of humoral immune responses to the oral treponemes (13). In general, antibodies of multiple isotypes have been detected in human sera; however, the relationship between levels of these antibodies and periodontal disease was quite variable (4, 13, 20, 27, 30). A detailed study of serum antibody responses to oral spirochetes (e.g., T. denticola and T. socranskii subspecies) in severe periodontitis, juvenile periodontitis, and healthy patients was reported (48, 49). The data showed a higher frequency of juvenile periodontitis patients seropositive to T. denticola, T. socranskii subsp. buccale, and T. socranskii subsp. paredis; the patients with severe periodontitis had a uniformly low level or absence of antibody to the treponemes. While these treponemes were present in all patient groups, including those with severe periodontitis (i.e., some of the isolates were actually cultivated from these patients), the level of antibody was not consistent with the burden of these species in the plaque. Less work has been done on evaluating humoral immune responses to the oral treponemes in animal models. We have noted that even with ligature-induced periodontitis in Macaca fascicularis, in which substantial increases in T. denticola in the plaque from diseased sites have been reported, the antibody response was quite low (unpublished observations). Also, our preliminary studies demonstrated a virtual absence of serum antibody to T. denticola in normal mice (unpublished observations).

The murine abscess model has been successfully utilized in examining the pathogenesis of oral bacterial infections, including Porphyromonas gingivalis (16, 22), Campylobacter rectus (24), and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (16). In these studies, increased levels of the pathogens within the murine host resulted in concomitant increases in humoral immune responses to the microorganisms. The purpose of this investigation, therefore, was to evaluate the immunologic characteristics of T. denticola infection in a murine model. Our preliminary studies suggested a lack of immune protection against T. denticola, in contrast to protection in mice with other oral pathogens, such as P. gingivalis and C. rectus (22, 24). Accordingly, four hypotheses were tested in this investigation. The first was that a minimal humoral immune response is induced by infection with the treponemes and that infection would be thus ineffective in providing protection against a subsequent reinfection. However, if antibody was elicited, it would have minimal functional capabilities for interfering with T. denticola infection. Alternatively, the ineffectiveness of the antibody would be associated with a skewed immunoglobulin G (IgG) subclass distribution, resulting in a lack of immune protection. Finally, antibody produced to T. denticola would be directed to a limited antigen repertoire and thus reflect the lack of humoral immunity to T. denticola infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

T. denticola ATCC 35404 (16, 23, 25, 51), a type strain of this species, was grown in GM-1 broth (7) or modified NOS medium (51) for 72 h in a Coy anaerobic chamber in an atmosphere of 85% N2, 5% CO2, and 10% H2 at 37°C. All manipulations were carried out under anaerobic conditions to ensure maximum cell viability. Culture purity of the treponemes was determined by dark-field and phase-contrast microscopy, with culture viability being estimated by the degree of motility and presence or absence of spherical bodies of the treponemes (23, 25). Log-phase cultures were harvested by centrifugation (9,000 × g for 10 min), and pellets were resuspended in fresh GM-1 broth under anaerobic conditions. An aliquot of the culture was removed from the chamber, and 10-fold dilutions were made in GM-1 broth for estimating total counts with a Petroff-Hausser bacterial counting chamber. The cells were enumerated, excluding spherical bodies.

P. gingivalis 3079.03 was used in these studies (16) as a positive control for immune protection in the murine abscess model. This microorganism was routinely grown anaerobically in a Coy anaerobic chamber for 48 to 72 h on prereduced Trypticase soy agar plates enriched with 5% sheep blood and harvested for infection studies, as described previously (22).

Mice.

ICR (Harlan Sprague-Dawley Inc., Indianapolis, Ind.) female mice aged 8 to 12 weeks old were used in these studies. The animals were housed in isolator cages in an accredited (American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care) animal facility at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Animals were provided autoclaved TEKLAD chow (Harlan Sprague-Dawley Inc., Madison, Wis.) and water ad libitum.

Murine virulence model.

The murine abscess model (15) as modified by Kesavalu et al.(22, 24, 25) was used to examine the virulence capacities of T. denticola and P. gingivalis. For determination of virulence and abscess-forming capability, bacterial dilutions (5 × 1010 for T. denticola and 2 × 1010 for P. gingivalis) were made in GM-1 medium (T. denticola) or reduced transport fluid (P. gingivalis) under anaerobic conditions as described previously (16, 22, 23). Mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) within 15 to 30 min of the bacterial preparation. After primary infection, the animals were monitored daily for symptoms of infection, and virulence was scored as the size of a localized abscess and/or necrotic spreading skin lesion and death. Sizes (length and width) of s.c. abscesses and necrotic spreading lesions were measured with a caliper gauge, and the area was determined and expressed in square millimeters. Our previous study (23) demonstrated that mice injected s.c. with GM-1 medium demonstrated neither toxicity nor any lesion at the site of injection. After the lesions healed (14 to 21 days), selected groups of mice were reinfected on the contralateral side of the back.

Active immunization.

Both T. denticola and P. gingivalis were grown as described above, and the cells were harvested by centrifugation and suspended overnight in 0.5% (vol/vol) buffered formal saline (formalin-killed [F-K] cells). Formalin-treated cells were washed three times with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the total counts, purity, and sterility were determined (22, 24, 25). F-K cells were stored at 4°C for use in active immunization and also for coating microtiter plates for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Mice were immunized by s.c. injection into the nape of the neck with 0.1 ml of 109 F-K T. denticola or P. gingivalis cells emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA). The control placebo-treated mice received IFA emulsified with sterile PBS, pH 7.2. A booster immunization of an identical preparation was administered 2 weeks later. Following booster immunization, two groups of mice were examined: (i) mice subjected to primary infection plus active immunization and (ii) mice subjected to active immunization alone. Both groups were challenged s.c. with viable T. denticola (5 × 1010 cells) approximately 2 weeks after the booster immunization. Following s.c. lesion healing and/or immunization, blood was collected and serum was prepared for antibody analysis.

Antibody analyses.

Blood for serum samples was collected after primary infection, reinfection, and active immunization by retro-orbital access either under general inhalation anesthesia or after CO2-induced euthanasia. IgG, IgM, and IgG subclass (IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3) antibodies were determined by ELISA (15). Briefly, formalin-killed T. denticola or P. gingivalis cells were applied to microtiter plates and left overnight at 4°C. After washing, the sera were serially diluted in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in microtiter plates and incubated for 2 h at room temperature on a rotator. Biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Fc specific; Sigma) and IgM (μ chain specific; Sigma) were added (1:5,000) to the washed plates and incubated for an additional 2 h at room temperature on a rotator. After washing, streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (1:1,000; Zymed, South San Francisco, Calif.) was added and incubated overnight at room temperature on a rotator. The substrate (p-nitrophenylphosphate; 1 mg/ml) was added to the washed plates, and the reaction was terminated by using 1 N NaOH. For IgG subclass ELISA analysis, goat anti-mouse IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 (heavy chain specific; Sigma), and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG (whole molecule; Sigma) were used. The optical density (OD) was measured spectrophotometrically at 405 nm (Dynatech MRX Plate Reader). Duplicate serial dilutions were used to construct curves relating the OD to the log2 of the dilution. From these individual curves, a linear dilution range was determined, and the antibody level was expressed in units described by the OD multiplied by the lowest dilution of the serum with an OD in the linear range of the ELISA curves. Normal pooled ICR mouse serum and either primary or reinfected serum were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Treponemal antigen.

T. denticola was grown to late logarithmic phase, and soluble antigen was prepared as described by Wicher et al. (53). The cells were pelleted by centrifugation (9,000 × g for 10 min), washed three times with sterile PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KH2PO4, 7 mM K2HPO4 [pH 7.2]), enumerated, and resuspended in PBS at 2 × 1010 cells/ml. The proteinase inhibitors phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and N-p-Tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone (2 mM each) were added. The cells were broken by sonication at ice bath temperature in six to eight 1-min cycles for complete disruption with a Cell Disruptor 200 (Branson Sonifier) and dissolved with 2% sodium N-laurylsarcosine for 30 min at 37°C. The protein concentration of the treponemal antigen was determined by the bicinchoninic acid procedure (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Ill.) and the preparation was aliquoted and stored at −70°C until use.

Electrophoresis.

Discontinuous sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed on a 10% gel as described by Laemmli (26). SDS-polyacrylamide gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R250 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) or by silver staining (Bio-Rad). Bio-Rad low-range molecular weight standards were used to estimate the molecular masses of T. denticola proteins.

Western immunoblotting.

T. denticola ATCC 35404 soluble antigen polypeptides were separated by SDS–10% PAGE. The proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto nitrocellulose paper (0.25-μm pore size; Schleicher & Schuell, Inc., Keene, N.H.) by using 25 mM Tris–192 mM glycine–20% methanol buffer (pH 8.3) at 8 V/cm for 3 h at 4°C (14). The nitrocellulose sheets were dried and then incubated for 4 h at 25°C in a blocking solution (1% bovine serum albumin in 10 mM Tris-buffered saline). Transferred proteins were probed with 1:2,000 dilutions of three individual mouse sera, from (i) primary infection, (ii) primary infection plus reinfection, and (iii) active immunization plus primary infection, by overnight incubation at 25°C. The bound antibody was identified with goat anti-mouse IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 (1:1,000) by incubation for 2 h at room temperature. The blots were washed, rabbit anti-goat IgG (whole molecule) conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (1:2,000) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 2 to 4 h at room temperature. After washing, the nitrocellulose blots were developed with a 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate–nitroblue tetrazolium substrate system (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's specifications. Molecular weights of the T. denticola polypeptides reacting with infected and immunized mouse sera were interpolated from known Bio-Rad Kaleidoscope prestained low-range molecular weight standards (14).

Immune immobilization of T. denticola.

T. denticola cultures were grown for 24 to 48 h. The T. denticola immobilization assay was modified from that described for T. pallidum (35, 37). Briefly, the treponemes with active motility were suspended at 108 cells per ml in NOS medium in sterile Microfuge tubes (79 μl) and mixed with pooled (n = 5) heat-inactivated (56°C, 30 min) primary infection, reinfection, or active-immunization mouse serum (11 μl) with unheated rabbit serum (undiluted) as a source of complement (10 μl). Heat-inactivated pooled normal mouse serum (undiluted) was used as a negative control. All manipulations were carried out under anaerobic conditions to ensure maximum cell viability. Aliquots were removed at 3 and 6 h for determination of motility, immobilization, and type of aggregation of cells (small and large clumps) by using dark-field phase-contrast microscopy. All immobilization assays were performed in duplicate on two different occasions to ensure consistency of the data.

In vitro immune function on growth kinetics.

To determine the cytotoxic function of the specific immune antibody on viability and growth of T. denticola, a 48-h-grown culture (160 μl) was mixed with (20 μl) of pooled (n = 5) heat-inactivated primary-infection serum (1:10, 1:100, or 1:1,000), normal mouse serum, and/or undiluted rabbit complement (20 μl) in tubes for 3 h under anaerobic conditions. Pooled, heat-inactivated normal mouse serum (undiluted) was used as a negative control. Ten milliliters of NOS medium was added to each tube after 3 h of exposure, mixed thoroughly, and incubated for an additional 72 h. At 24, 48, and 72 h postincubation, 1 ml of culture was removed from each tube, and growth was determined by measurement of OD at 660 nm. Culture purity was examined by phase-contrast microscopy and Gram staining.

In vivo immune antibody function.

T. denticola was grown in NOS medium as described above, pelleted by centrifugation, enumerated, and resuspended in fresh NOS medium at 5 × 1010 cells per ml. Pooled heat-inactivated primary infected or normal mouse serum (10%, vol/vol) and rabbit complement (10%, vol/vol) were mixed with viable T. denticola (80% vol/vol) inside the anaerobic chamber. Groups of mice were challenged (s.c. injection) with 1010 treponemes after 1 or 3 h of exposure to the mouse serum and complement. The groups consisted of (i) T. denticola plus primary-infection mouse serum and complement (1 h of exposure), (ii) T. denticola plus primary-infection mouse serum and complement (3 h of exposure), (iii) T. denticola plus normal mouse serum and complement (3 h of exposure), (iv) T. denticola plus complement (3 h of exposure), and (v) T. denticola alone (untreated control). After challenge, the animals were monitored and the lesions were scored. Following s.c. lesion healing, blood was collected, serum was separated, and IgG antibody levels were analyzed by ELISA.

Chemicals.

Unless otherwise stated, all the chemicals and reagents were obtained from Sigma Biosciences, St. Louis, Mo.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical differences in lesion size or antibody levels among various groups were determined by using a Wilcoxon–Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher's exact test (Minitab, State College, Pa.).

RESULTS

Virulence of T. denticola in the murine model.

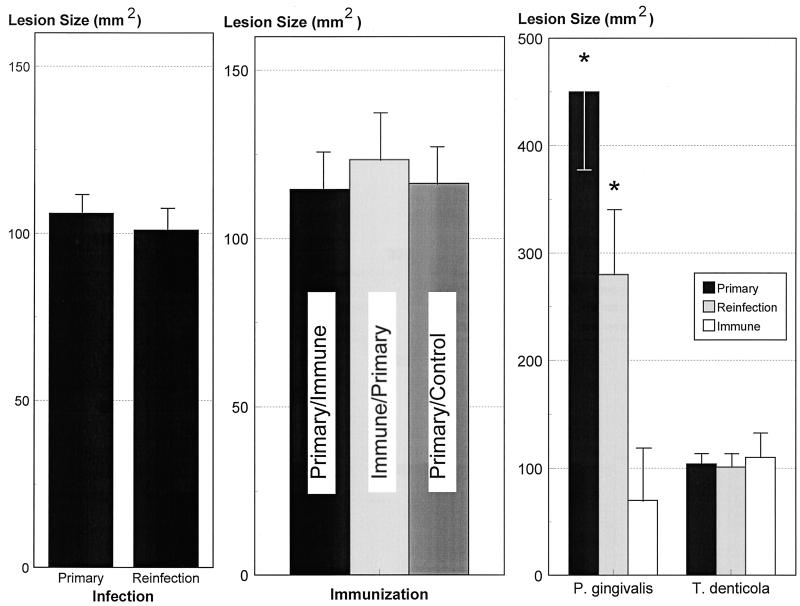

In this study we evaluated the immune characteristics and immune protection following primary infection and reinfection with T. denticola in a murine abscess model. Following both primary infection and reinfection, lesion sizes in all animals were approximately 100 mm2 (Fig. 1). There was gross evidence of hyperemia and diffuse edema at the site of inoculation, and by day 4 abscess formation was noted, as described previously (25). Following recovery from the primary T. denticola infection (14 to 21 days), these animals were reinfected on the contralateral dorsolateral surface of the back with 5 × 1010 T. denticola cells (reinfection) to evaluate the characteristics of acquired immune protection. All animals developed localized abscesses similar to those seen in the primary infection, with respect to onset, duration, and lesion characteristics. There was no mortality induced by s.c. infection with T. denticola. The effects of active immunization on T. denticola virulence in mice were evaluated. Both immunized and control mice challenged with viable T. denticola developed localized abscesses of sizes similar to those seen in primary infection or reinfection (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Virulence of T. denticola ATCC 35404 in mice. (Left) Mice were infected s.c. with 5 × 1010 T. denticola organisms, and the animals developed a localized lesion (Primary). After recovery from the localized lesion, mice were reinfected with 5 × 1010 T. denticola organisms (Reinfection). (Center) Lesion formation is also shown for mice actively immunized with T. denticola after (i) primary infection followed by immunization (Primary/Immune), (ii) T. denticola immunization (Immune/Primary), or (iii) primary T. denticola infection followed by control injection with IFA (Primary/Control). The lesion results for the Primary/Immune and Primary/Control groups are following a reinfection with 5 × 1010 T. denticola organisms. Each bar indicates the mean lesion size from five mice per group in three independent experiments, and the error bars indicate one standard deviation. (Right) Comparison of lesion sizes for P. gingivalis and T. denticola. Mice were infected with 2 × 1010 P. gingivalis or 5 × 1010 T. denticola organisms s.c. The bars indicate the mean lesion sizes from groups of 5 to 15 mice. No control results are provided for the lesion data, since mice injected with GM-1 medium and reduced transport fluid developed no lesions. The asterisks indicate results significantly different from those for the immune group (P < 0.01).

A comparison of the effects of acquired immunity on subsequent lesion formation following reinfection with either P. gingivalis or T. denticola is depicted in Fig. 1. In contrast to the apparent absence of immune protection against T. denticola, animals subjected to primary infection with P. gingivalis or actively immunized animals demonstrated significantly decreased lesions following reinfection, indicating significant immune protection. These observations demonstrate a substantial difference in immune protection between these two oral pathogens in this murine abscess model.

Humoral immune responses to T. denticola.

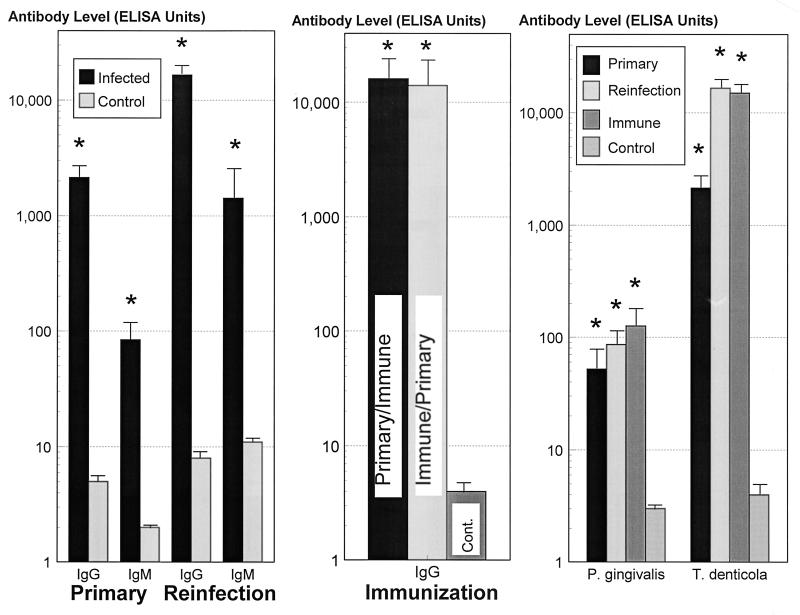

The serum IgG antibody response following primary infection with T. denticola was approximately 400-fold higher (P < 0.0001) than that in control uninfected animals (Fig. 2). Similarly, the primary IgM antibody response was 40-fold higher (P < 0.001) than that in control uninfected animals. Reinfection with T. denticola significantly enhanced serum IgG and IgM antibody levels by approximately 20,000-fold (P < 0.0001) and 150-fold (P < 0.0001) greater than that in control uninfected animals, respectively. Also, the IgG (10-fold; P < 0.005) and IgM (17-fold; P < 0.001) antibody responses from reinfection were greater than those induced by primary infection. Active immunization of the mice with T. denticola induced serum IgG levels similar to those following the reinfection (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

IgG and IgM antibody levels, expressed as ELISA units, in sera from mice infected and/or immunized with T. denticola ATCC 35404. (Left) Groups of four to five mice were infected s.c. with 5 × 1010 T. denticola organisms. The results represent serum antibody levels in blood collected at approximately 2.5 weeks postinfection. For primary infection and reinfection studies, the bars indicate the group mean antibody levels from three independent experiments. The error bars indicate one standard deviation, and the asterisks indicate levels of antibody significantly greater than those in control mice (P < 0.001). (Center) The bars indicate levels of antibody in groups treated by primary infection followed by immunization and reinfection (Primary/Immune), immunization followed by primary infection (Immune/Primary), and primary infection followed by control injection (IFA) and reinfection (Cont.). The error bars indicate one standard deviation, and the asterisks indicate levels of antibody significantly greater than those in control mice (P < 0.001). (Right) Comparison of serum antibody levels for P. gingivalis and T. denticola in mice. The bars indicate mean results from groups of 5 to 15 mice. The error bars indicate one standard deviation, and the asterisks indicate results significantly different from those for control mice (P < 0.01).

Figure 2 also compares serum IgG antibody levels elicited after infection or immunization with P. gingivalis or T. denticola. The results demonstrate that T. denticola induces significantly higher IgG antibody levels than P. gingivalis, although no immune protection against T. denticola reinfection was observed.

Functional activity of antibody to T. denticola.

Immobilization of T. denticola was performed to determine if the antibodies elicited after primary infection and immunization were effective in limiting the motility of the treponemes (Table 1). Sera from mice after primary infection, with or without complement, immobilized all of the treponemes, resulting in large clumps by 3 h. Similar results were observed at higher serum dilutions with sera from reinfected mice by 3 to 6 h. There was enhanced aggregation and immobilization of treponemes at higher dilutions of active-immunization sera, with and without complement, by 3 h. Neither immobilization nor aggregation of T. denticola occurred in the presence of normal mouse serum, indicating the absence of specific immobilizing antibodies. The bacterial cells were actively motile in control assays with treponemes alone or treponemes in the presence of complement. In fact, aggregation and complete immobilization were noted by 30 to 40 min with mixtures containing immune serum with or without complement (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

T. denticola aggregation and immobilization with sera from actively immunized and/or infected micea

| Treatment (Mouse serum and rabbit complement)

|

3 h

|

6 h

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1° | Imm | 2° | C′ | Aggregationb | Immobilizationb | Aggregation | Immobilization |

| − | − | − | − | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 |

| − | − | − | + | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 |

| + | − | − | − | 1,000 | 100 | 1,000 | 100 |

| + | − | − | + | 1,000 | 100 | 10,000 | 100 |

| + | − | + | − | 10,000 | 1,000 | 10,000 | 1,000 |

| + | − | + | + | 10,000 | 1,000 | 10,000 | 1,000 |

| + | + | − | − | 10,000 | 100 | NDc | ND |

| + | + | − | + | 10,000 | 100 | ND | ND |

| + | + | + | − | 1,000 | 100 | ND | ND |

| + | + | + | + | 1,000 | 100 | ND | ND |

| + | −* | + | + | 1,000 | 100 | ND | ND |

| + | −* | + | + | 10,000 | 100 | ND | ND |

1°, primary infection; Imm, active immunization; 2°, reinfection; C′, rabbit complement; ∗, control immunization with IFA. Aggregation, small and/or large clumps of treponemes; immobilization, lack of motility of the treponemes. The treponeme-alone control consisted of uniformly motile, individual treponemes. The data is derived from replicate determinations of sera pooled from five mice per treatment group.

Minimum serum dilution required to demonstrate the alteration in the treponeme population.

ND, not done.

Since the antibody appeared to immobilize and aggregate the treponemes, we evaluated the effect of immobilizing antibody on the growth of T. denticola. Sera from mice after primary infection, with or without complement, appeared to initially retard the growth of T. denticola during the first 24 h of culture (Table 2). This was accompanied by aggregation and settling of the treponemes in the tubes. However, by 48 to 72 h, the treponeme cultures displayed normal growth (compared to controls with treponemes only or treponemes plus complement), and no further aggregation was observed. Normal mouse serum, with or without complement, had no apparent effect on T. denticola growth. The observations suggest that primary T. denticola-infected serum contains specific antibodies which aggregated the microorganism and inhibited T. denticola motility. However, this antibody activity only slowed initial T. denticola replication and did not alter the maximum growth in vitro.

TABLE 2.

Effect of immune mouse serum on T. denticola growth

| Treatmenta

|

OD at 600 nmb after growth for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum (dilution) | C′ | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h |

| − | − | 0.137 | 0.301 | 0.452 |

| − | + | 0.129 | 0.330 | 0.463 |

| N (10) | − | 0.133 | 0.350 | 0.496 |

| N (10) | + | 0.143 | 0.323 | 0.483 |

| P (10) | − | 0.063c | 0.291c | 0.525 |

| P (10) | + | 0.037c | 0.263c | 0.479 |

| P (100) | + | 0.041c | 0.266 | 0.446 |

| P (1,000) | + | 0.050 | 0.270 | 0.455 |

N, normal mouse serum; P, primary-infection mouse serum; C′, rabbit complement.

The data are derived from replicate determinations with sera pooled from five mice per treatment group.

Clumping of treponemes in culture was observed.

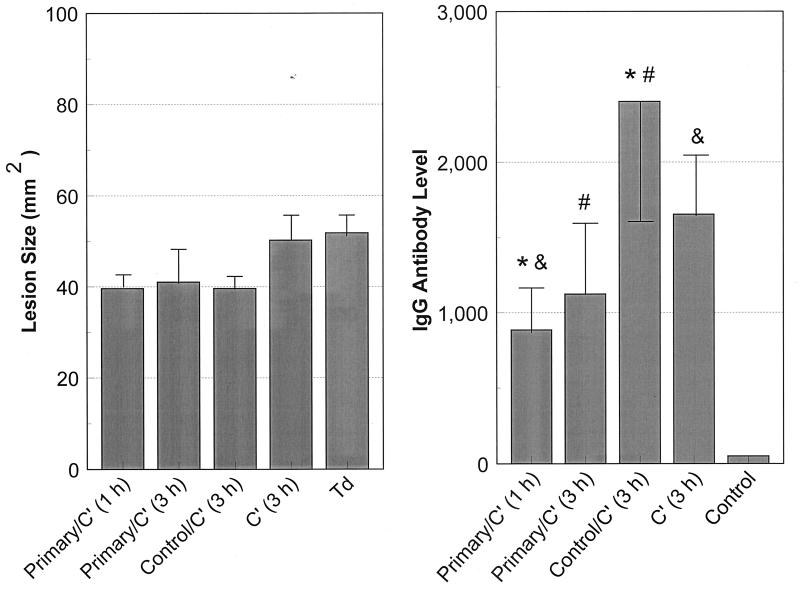

We therefore hypothesized that the lack of protection from lesion formation may occur because of an inability of anti-T. denticola antibody to access the local site of infection. To test this, viable T. denticola cells were directly mixed with (i) heat-inactivated pooled primary-infection serum and complement or (ii) heat-inactivated pooled normal mouse serum and complement. After a 1- or 3-h exposure under anaerobic incubation, mice were infected with 1010 treated treponemes. There was substantial aggregation of treponemes in the immune serum tubes with a clear supernatant by 40 to 45 min. In contrast, a uniform suspension of treponemes was observed in controls consisting of the normal mouse serum, complement alone, or untreated T. denticola, indicating no aggregation or immobilization of the treponemes (data not shown). All animals developed a localized abscess similar to that induced by a primary infection. The onset, duration, and characteristics of the abscess were similar to those in a primary infection. There was no significant difference in the sizes of abscesses induced by exposure of T. denticola for either 1 or 3 h to the murine serum containing antibody elicited by infection. In addition, there was no significant difference in abscess size between the groups treated with antibody-containing and normal sera. However, the lesion size was smaller by 25% (P < 0.001) compared to those induced by control untreated treponemes and treponemes incubated with complement only. The results indicate that the anti-T. denticola antibodies did not appear to modulate or eliminate the T. denticola infection, but the serum from mice subjected to primary infection, with complement, did appear to decrease the maximum lesion size.

We also determined the ability of preincubation of T. denticola with mouse serum with or without antibody to modify the acquired host response in infected mice. Sera from animals infected with treponemes exposed to the antibody-containing mouse serum and complement had lower levels of IgG antibody than sera from animals infected with treponemes exposed to normal mouse serum and complement (P < 0.03) or to complement only (Fig. 3). Minimal levels of serum IgG were detected in the normal pooled mouse serum (negative serum control). Thus, the murine anti-T. denticola antibody, which effected aggregation and immobilization of treponemes, appeared to result in impaired host recognition of T. denticola antigens.

FIG. 3.

(Left) Ability of serum antibody incubated with T. denticola in vitro to alter lesion development following reinfection. The bars indicate means for five animals per group challenged with 1010 T. denticola organisms after incubation with primary-infection sera and rabbit complement (Primary/C′) for 1 or 3 h, with control normal mouse serum and complement for 3 h, or with complement alone for 3 h. Td indicates control T. denticola maintained in NOS medium for 3 h (similar to the experimental incubations). The error bars indicate one standard deviation. (Right) Serum IgG antibody levels in mice challenged with T. denticola following in vitro incubations as described above. The bars indicate the mean serum IgG levels of 5 to 10 mice per group, and the error bars indicate one standard deviation. The paired symbols indicate IgG antibody levels significantly different at P < 0.02 (∗ and #) or P < 0.05 (&). Antibody levels in all treated groups were significantly greater than those in pooled normal mouse serum (Control) (P < 0.001).

IgG subclass responses to T. denticola.

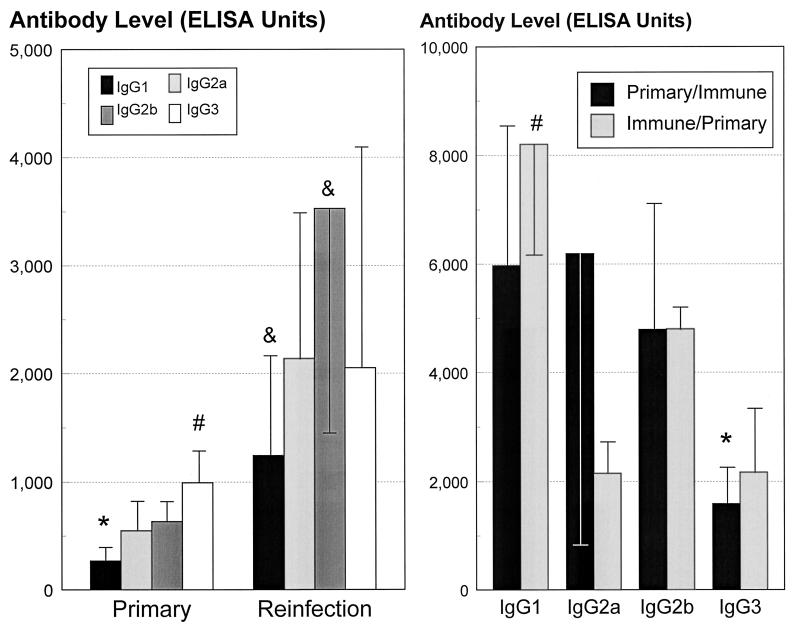

Thus, we had observed that T. denticola is antigenic in the mice, which resulted in elevated levels of serum antibodies. Furthermore, there was some functional activity of the antibody, although this did not translate into a protective immunity. In order to more fully evaluate the characteristics of the antibody, we determined the IgG subclass distribution of the humoral immune response following infection and immunization. Following a primary infection, the IgG3 subclass levels were significantly (P < 0.02) greater than the IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b antibody levels (Fig. 4). Additionally, the IgG1 antibody level was significantly less than those of the other IgG subclasses in response to this primary infection. The IgG subclass profiles in response to reinfection appeared generally similar to those for primary infection (Fig. 4). Reinfection significantly (P < 0.003) enhanced serum IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b subclass levels (four- to sixfold) over those in primary infection. IgG3 levels were increased to a lesser extent (twofold). As in the primary infection, the IgG1 subclass level was lower than those of other antibody subclasses. The results suggested a particular pattern of response to infection which consisted primarily of the IgG3, IgG2b, and IgG2a subclasses.

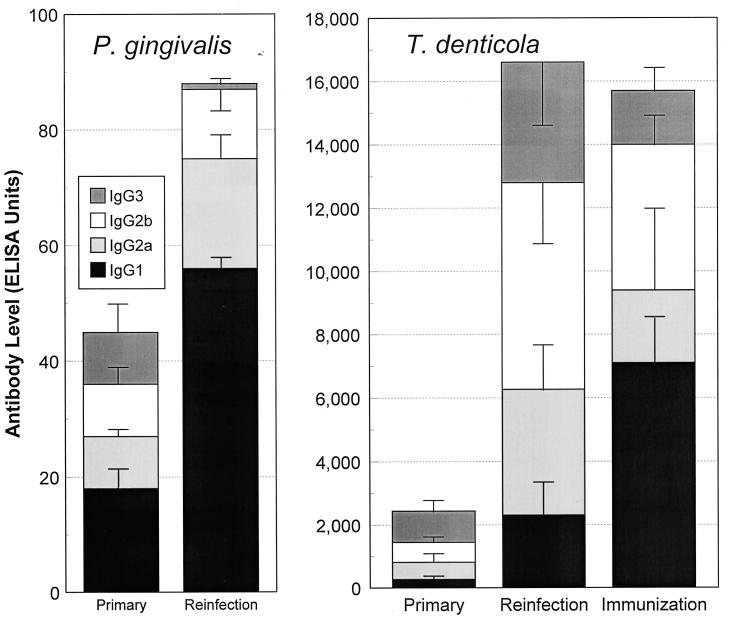

FIG. 4.

(Left) Serum IgG subclass antibody levels expressed as ELISA units, following primary infection or reinfection with T. denticola. The bars indicate the means from 10 to 15 animals derived from three independent experiments, and the error bars indicate one standard deviation. ∗, significantly less than all other subclasses at P < 0.025; #, significantly greater than all other subclasses at P < 0.025; &, significantly lower than IgG2b levels at P < 0.025. (Right) Serum IgG subclass antibody in sera from mice actively immunized with T. denticola after primary infection (Primary/Immune) and before primary infection (Immune/Primary). The IgG antibody levels were determined from sera obtained from the Primary/Immune and Immune/Primary groups following a reinfection with 5 × 1010 T. denticola organisms. Each bar indicates the mean antibody level from five mice per group, and the error bars indicate one standard deviation. ∗, significantly less than IgG1 and IgG2b levels at P < 0.02; #, significantly greater than all other subclasses within the treatment group at P < 0.01.

Active immunization plus primary infection induced significantly higher IgG1 responses than those of other subclasses. This immunization procedure also appeared to change the major IgG3 antibody subclass response to infection to a predominantly IgG1 response. Although different IgG subclass profiles were elicited by infection and immunization, these IgG isotype antibodies did not appear to correlate with in vivo protection. This observation was noted even though the immunization sera (i.e., elevated IgG1) appeared to be more effective in T. denticola immobilization and aggregation.

Figure 5 demonstrates a difference in the serum IgG isotype pattern and distribution, particularly related to the infection process of P. gingivalis and T. denticola. Primary infection with P. gingivalis induced IgG1 levels higher than those of other IgG subclass antibodies. Similarly, reinfection induced an elevated IgG1 antibody response, which correlated with immune protection (Fig. 1). In contrast, T. denticola infection induced an IgG3 and IgG2b response, and a lower IgG1 antibody level, following primary infection and reinfection. Active immunization with T. denticola altered the pattern of distribution to one more similar to that with P. gingivalis (i.e., IgG1 predominant); however, significant immune protection against subsequent T. denticola challenge infection was not observed (see Fig. 1).

FIG. 5.

Distribution of serum antibody subclasses in mice following primary infection and reinfection or after active immunization with either P. gingivalis or T. denticola. The bars indicate the mean levels in groups of 5 to 10 mice. The error bars indicate one standard deviation. Because of differences in optimizing the ELISAs for the individual subclasses, as well as the different antigens, the subclass proportions are expressed relative to the total IgG antibody to each of the individual microorganisms (Fig. 2).

Antigenic specificity of acquired humoral immune responses to T. denticola.

To assess antigen and antibody specificity in this model system, Western immunoblotting with solubilized T. denticola antigens was performed. SDS-PAGE demonstrated numerous protein bands from 18 to ∼160 kDa. Similarly, blots reacted with infected mouse serum demonstrated up to 36 antigen bands (Table 3). Major antigen bands identified by IgG subclass antibodies in sera from immunized and infected mice were noted at 95, 77, 75, 70, 60, 55, 40, 30, 29, and 20 kDa (Table 3). While there were some differences in the major antigens detected by the different subclasses (e.g., 116 kDa for IgG1 and IgG3, 90, 68, 50, and 38 kDa for IgG1 and IgG2b; and 19 kDa for IgG2b and IgG3), many of the antigen bands were recognized by multiple subclasses of IgG antibody (Table 3). The greatest heterogeneity in antigen band frequency occurred in the mice with primary infection. The characteristics of sera from reinfected animals were less variable in antigen band frequency, and similar numbers of antigen bands were detected by each of the subclasses (Table 4). However, there were additional antigens detected by the reinfection sera (e.g., 90, 68, 45, 35, 33, 30, and 20 kDa). Active-immunization sera reacted to antigen bands which were similar between animals and among IgG subclasses (Table 4). As was noted with the levels of IgG3 antibody to the whole microorganism, somewhat fewer antigen bands were detected by this subclass, and new antigens were detected by other subclasses compared to the case for primary infection. However, there was no demonstrable difference in antigens recognized by serum from reinfection versus active immunization. Specific for the hypothesis proposed, many antigen bands were commonly reactive with sera from primary infected, reinfected, and actively immunized mice, although the intensities of the antigen reactivity and subclass antibody characteristics varied among the sera. The findings suggest that T. denticola presents numerous antigens to the host and elicits a broadly based polyclonal antibody response.

TABLE 3.

Western immunoblot analysis of mouse IgG subclass antibody binding to soluble antigens from T. denticola ATCC 35404

| IgG antigen band (kDa) | Recognition by antibodya

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG1 | IgG2a | IgG2b | IgG3 | |

| 162 | + | |||

| 155 | + | |||

| 150 | + | |||

| 145 | + | + | + | + |

| 140 | + | |||

| 137 | + | + | + | |

| 130 | ++ | + | ||

| 125 | + | + | ||

| 120 | + | + | + | + |

| 116 | ++ | + | + | ++ |

| 110 | + | + | + | |

| 100 | ++ | + | + | |

| 95 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 90 | ++ | + | ++ | |

| 85 | + | ++ | + | + |

| 82 | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| 80 | ++ | ++ | + | |

| 77 | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| 75 | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| 70 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 68 | ++ | + | ++ | |

| 64 | + | + | + | |

| 60 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 55 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 50 | ++ | + | ++ | + |

| 45 | ++ | + | + | |

| 43 | ++ | + | ||

| 40 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 38 | ++ | + | ++ | + |

| 35 | ++ | + | + | + |

| 33 | ++ | + | + | |

| 30 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 29 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| 20 | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| 19 | ++ | ++ | ||

| 18 | + | ++ | ++ | |

| Totalb | 27 (21) | 25 (12) | 32 (18) | 27 (11) |

++, high-intensity band.

Numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of high-intensity bands.

TABLE 4.

Distribution of T. denticola soluble polypeptide antigens reactive with mouse IgG subclass antibodies of infected animals

| Mouse IgG subclass antibody | No. of reactive antigensa from animals subjected to:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary infection | Primary infection + secondary infection | Active immunization + primary infection | |

| IgG1 | 5 (3), 9 (4), 14 (4) | 16 (5), 18 (7), 16 (7) | 16 (7), 19 (5) |

| IgG2a | 5 (3), 4 (3), 12 (2) | 16 (4), 14 (6), 21 (6) | 16 (4), 12 (5) |

| IgG2b | 6 (3), 17 (2), 12 (3) | 17 (8), 17 (5), 23 (5) | 14 (8), 16 (5) |

| IgG3 | 13 (2), 13 (3), 24 (5) | 17 (3), 20 (6), 22 (4) | 15 (3), 7 (2) |

Total number of polypeptides reactive with each mouse serum (values were obtained from three or two individual mouse sera from each group). The values in parentheses are the number of antigens reacting with high intensity.

DISCUSSION

Humoral immune responses to primary infection and reinfection with T. denticola and to active immunization of mice were quantified, immunoglobulin isotype and subclass profiles were determined, immunogenic T. denticola antigens were estimated, and immune functions were assessed. The ultimate importance of the investigation was to elucidate the capacity of the humoral immune response to confer immunity to infection and the characteristics of the response. The initial findings indicated that irrespective of recovery from a primary infection or active immunization, mice were not protected from a subsequent reinfection with T. denticola. Similar results were also noted with other oral treponemes, including T. socranskii, T. vincentii, and T. pectinovorum (unpublished data). In contrast, P. gingivalis and C. rectus infection or immunization induced immune protection in this model (22, 24).

Based on our initial findings, we hypothesized that the animals demonstrate a limited humoral immune response, which results in lack of protection from challenge infection. This concept was also based on the breadth of studies with human periodontitis populations, which showed that there were large numbers of treponemes in the plaque, while a rather minimal and inconsistent systemic antibody response was observed (4, 13, 20, 27, 48, 49). In contrast, the data presented in this study shows that primary infection with T. denticola in mice elicits a substantial serum IgM and IgG antibody response, with normal mice exhibiting no detectable serum antibody. We subsequently compared the actual level of antibody to that detected in a similar system with P. gingivalis, in which significant protection was observed (10, 11, 22). The results indicated that the level of IgG antibody to the treponemes was nearly 30 times greater than the levels of antibody to P. gingivalis following primary infection. Thus, the absence of protection did not appear to be associated with a lack of ability of the mice to mount a substantial antibody response. Moreover, following reinfection, mice generated an even greater IgG response, which was approximately 10 times more than that in the primary infection, but the lesion size was similar to that in the primary infection. Finally, actively immunized mice, whose serum IgG level was similar to that seen in reinfection, were also not protected from T. denticola infection. Consequently, the mice demonstrated a substantial humoral response, although the magnitude of antibody produced could not explain the lack of protective immunity.

Therefore, we hypothesized that this antibody may lack the ability to alter T. denticola growth and/or motility, which are likely important in infections with this pathogen. We observed that there was a gradation from primary infection to reinfection to active immunization in the ability of the specific antibody to aggregate and immobilize the treponemes in vitro. This was generally independent of complement fixation. This type of finding has been correlated with immune resistance to T. pallidum, although the activity against this pathogen was found to be complement dependent (37). While motility of these oral microorganisms has not been directly linked to their ability to colonize the subgingival sulcus, it is generally thought that this capability provides an important strategy for the treponemes to access nutrients within the plaque biofilm (9, 17), as well as being related to their capacity to invade tissues (39). These observations suggest that the serum immobilizing antibody bound to surface molecules of T. denticola, resulting in clumping and inhibiting motility; this has a minimal impact on the in vivo lesion-forming ability.

We then hypothesized that immune immobilization and aggregation would alter the growth characteristics of T. denticola. However, we observed that following total aggregation of the treponemes, they grew to normal densities similar to those of unaggregated cells. Therefore, the in vivo results demonstrating a lack of immune protection could be explained by (i) the antibody produced having a minimal effect on survival, even while aggregating and immobilizing the bacteria, or (ii) the antibody not reaching the infection site. We examined this alternative by mixing antibody-containing serum with T. denticola, incubating the mixture to allow aggregation and immobilization, and challenging mice with these treated treponemes. Thus, we could be assured that the antibody had the opportunity to interact with the treponemes at high levels and sufficiently early during an infectious challenge. The abscess size was somewhat less than that with T. denticola alone, and there was no difference in lesion size between the treponemes treated with immune and control normal sera. Furthermore, no difference in lesion characteristics was observed, even with extended incubation with the immune sera. Consequently, the antibody interacted with the treponemes, altering the physical characteristics of the population (i.e., they were aggregated and less motile), but had a minimal effect on their virulence. We also evaluated the murine antibody response to treponemes treated with immune antibody prior to the infection. The results showed that the humoral immune response of these infected mice was lower than that of mice challenged with T. denticola incubated with either control normal serum or complement, as well as with untreated T. denticola. Our interpretation of this finding was that the immune antibody coated or bound to surface antigens on the treponemes and minimized the subsequent host recognition of surface antigens following a challenge infection. This type of virulence strategy has been identified with T. pallidum, a phenomenon often attributed to an outer coat of host serum proteins wherein virulent T. pallidum reacts poorly with the specific antibodies present in human and rabbit syphilitic sera (1).

Consequently, we had found that T. denticola elicited high levels of antibody, which has the ability to alter some functions of the pathogen, although this did not translate into immune protection. One mechanism to account for these findings is that T. denticola uses a virulence strategy which skews the production of a subclass profile that could not abrogate its pathogenicity. Examples of these types of deviations or shifts of IgG subclass immune responses have been identified with Chlamydia psittaci (52), Mycobacteirum lepraemurium (31), and Trichuris muris (6) infections. The IgG subclass distribution of the antibody following primary infection, reinfection, and active immunization demonstrated a broad subclass response to infection. The predominant response following primary infection and reinfection was the IgG3 subclass, with IgG1 antibody levels being substantially less. Briles et al. (8) first demonstrated that mouse IgG3 antibodies to the phosphocholine determinant of pneumococcal C-carbohydrate and to type 3 pneumococcal polysaccharide were highly protective against experimental pneumococcal infection. In contrast, the predominant IgG3 subclass antibody response to primary infection with T. denticola did not protect against reinfection. It has been shown that IgG2a antibody is the most effective subclass for the induction of macrophage and killer cell antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity of tumor cells and the predominant IgG subclass in antibody-mediated protective responses in most viral infections, functioning by opsonization and complement-mediated lysis of viruses and destruction of virus-infected cells (47). The lack of a protective humoral immune response to T. denticola infection in mice correlated with a decreased IgG2a production, potentially reflecting a lack of opsonization and complement-mediated lysis potential of the antibody population. Various studies of the distribution of antibody responses in mice have identified profiles of subclass antibodies which are indicative of primary stimulation of either Th1 or Th2 functions (34, 47). In particular, Th2 cells elicited by immunization confer protective immunity against Borrelia burgdorferi (36), and all helminth parasites induce a dramatic expansion of the Th2 lymphocyte subset (2). Moreover, differential activation of Th1 and Th2 cell subsets results in induction of characteristic IgG subclass responses in Mycobacterium lepraemurium, coxsackievirus group B type 3, Trichuris muris, and Schistosoma mansoni infections (6, 19, 31, 32). The results indicated an initial IgG3 response after infection, suggesting a skewed IgG antibody subclass response which could account for the lack of humoral immune protection. In our study, active immunization of T. denticola with adjuvant, either prior to or following an infection, altered this dominant IgG subclass antibody response. This was noted as a principal IgG1 subclass response (Th2 response) and appeared to minimize the IgG3 response (immunization followed by primary infection) or turn off the IgG3 response (primary infection followed by immunization) (28, 40). This IgG subclass distribution was observed in sera from mice following P. gingivalis infection and accompanying immunity. Our findings were that primary infection and reinfection with P. gingivalis and active immunization elicited a predominant IgG1 antibody response, with the IgG3 response being nearly 8- to 10-fold less. Active immunization of mice with T. denticola shifted or modulated the antibody response to the IgG1 subclass, which was a distribution of subclasses similar to that for P. gingivalis. Consequently, the skewed IgG subclass humoral immune response to T. denticola could not explain the lack of immune protection.

Finally, we used Western immunoblotting to test the hypothesis that the lack of immunity was associated with a limitation in the breadth of antibody reactivities to the antigen repertoire presented by T. denticola. Results from other bacterial and helminth infections have indicated that selected pathogens utilize immune evasion strategies in which the host is unable to recognize critical antigens used for virulence determinants. This has been associated with antigenic mimicry in parasitic helminths (2) and antigenic variation in trypanosomes, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and B. burgdorferi (43). More recently, an immunodominant peptide motif in a lipoprotein antigen of T. pallidum with multiple repeats of amino acid sequences in human fibronectin was identified (5). This mimicry was suggested to be active in initially triggering anti-host protein responses associated with disseminated syphilis, with subsequent expansion of the responses by other self-epitopes. In contrast, our results demonstrated a broad reactivity of antibody to numerous T. denticola antigens. Intense reactions to many antigens were observed, which were somewhat characteristic of the individual subclasses of antibody. In addition, selected antigens elicited strong reactions with multiple IgG subclass antibodies. In comparing the frequencies of antigens detected, it appeared that mice with primary infection exhibited a more variable response, which reflected the subclass distribution of the total IgG antibody. More homogeneous responses were noted following reinfection and active immunization. Thus, while we could not determine, in this study design, whether T. denticola had critical virulence determinants to which the mice lacked a humoral immune response, the results demonstrated a gradual but continual increase in the number of antigens recognized from primary infection, to reinfection, to active immunization. These observations are in parallel with those for T. pallidum infection, where mice responded slowly but recognized increasing numbers of antigens during infection (42). Consequently, these findings favored an interpretation that the lack of protective immunity was not due to a limited specificity of the antibody repertoire.

Recent data have suggested that the major protective T. pallidum immunogens are not surface exposed, since treponemes with disrupted outer membranes were markedly more antigenic than intact treponemes, and the limited antigenicity of virulent microorganisms appeared to reflect a paucity of proteins in the outer membrane (12). This concept could also explain the lack of humoral immune protection observed in T. denticola infections in our model. Moreover, host defense mechanisms are multifactorial, and the key antigenic components of T. denticola which elicit protective immunity and the effector mechanisms of the immunity remain undefined. In reviewing the outcomes of this investigation, we were forced to conclude that the humoral immune response to T. denticola, was not an effective host response. While differences in the humoral immune response in mice and humans are observed, this murine model suggested that protective immunity to T. denticola may be dependent on other immune mechanisms, such as cell-mediated immunity. Selected pathogens use a virulence strategy involving induction of antibody via activation of selected T-cell subsets and specific cytokine production. This antibody response not only may be ineffective in immune protection but also may protect the pathogens from an effective cell-mediated immune response. We propose that T. denticola may use this virulence strategy, and further studies to explore mechanisms for inducing and/or shifting the host response to increase T-cell or macrophage participation as an alternative to provide immune protection will be required.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Public Health Service grant DE-11368 from the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research.

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Stephen Walker, Michelle Steffen, and Pravina Patel.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alderete J F, Baseman J B. Surface-associated host proteins on virulent Treponema pallidum. Infect Immun. 1979;26:1048–1056. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.3.1048-1056.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen J E, Maizels R M. Immunology of human helminth infection. Int Arch Allergy Immun. 1996;109:3–10. doi: 10.1159/000237225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armitage G C, Dickinson W R, Jenderseck R S, Levine S M, Chambers D W. Relationship between the percentage of subgingival spirochetes and the severity of periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1982;53:550–556. doi: 10.1902/jop.1982.53.9.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aukhil I, Lopatin D E, Syed S A, Morrison E C, Kowalski C J. The effects of periodontal therapy on serum antibody (IgG) levels to plaque microorganisms. J Clin Periodontol. 1988;15:544–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1988.tb02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baughn R E, Jiang A, Abraham R, Ottmers V, Mucher D M. Molecular mimicry between an immunodominant amino acid motif on the 47-kDa lipoprotein of Treponema pallidum (Tpp47) and multiple repeats of analogous sequences in fibronectin. J Immunol. 1996;157:720–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellaby T, Robinson K, Wakelin D. Induction of differential T-helper-cell responses in mice infected with variants of the parasite nematode Trichuris muris. Infect Immun. 1996;64:791–795. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.791-795.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blakemore R P, Canale-Parola E. Arginine catabolism by Treponema denticola. J Bacteriol. 1976;128:616–622. doi: 10.1128/jb.128.2.616-622.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briles D E, Claflin J L, Schroer K, Forman C. Mouse IgG3 antibodies are highly protective against infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nature. 1981;294:88–90. doi: 10.1038/294088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlsson J. Bacterial metabolism in dental biofilms. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11:75–80. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110012001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen P B, Neiders M E, Miller S J, Reynolds H S, Zambon J J. Effect of immunization on experimental Bacteroides gingivalis infection in a murine model. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2534–2537. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.10.2534-2537.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen P B, Davern L B, Schifferle R, Zambon J J. Protective immunization against experimental Bacteroides (Porphyromonas) gingivalis infection. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3394–3400. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3394-3400.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox D L, Chang P, McDowall A W, Radolf J D. The outer membrane, not a coat of host proteins, limits antigenicity of virulent Treponema pallidum. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1076–1083. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1076-1083.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebersole J L. Systemic humoral immune responses in periodontal disease. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1990;1:283–331. doi: 10.1177/10454411900010040601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebersole J L, Cappelli D, Sandoval M-N, Steffen M J. Antigen specificity of serum antibody in A. actinomycetumcomitans-infected periodontitis patients. J Dent Res. 1995;74:658–666. doi: 10.1177/00220345950740020601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebersole J L, Frey D E, Taubman M A, Smith D J. An ELISA for measuring serum antibodies to Actinobacillus actinomycetumcomitans. J Periodontal Res. 1980;15:621–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1980.tb00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ebersole J L, Kesavalu L, Schneider S L, Machen R L, Holt S C. Comparative virulence of periodontopathogens in a mouse abscess model. Oral Dis. 1995;1:115–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1995.tb00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellen R P, Lepine G, Nghiem P-M. In vitro models that support adhesion specificity in biofilm of oral bacteria. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11:33–42. doi: 10.1177/08959374970110011401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holt S C, Bramanti T E. Factors in virulence expression and their role in periodontal disease pathogenesis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1991;2:177–281. doi: 10.1177/10454411910020020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huber S A, Pfaeffle B. Differential Th1 and Th2 cell responses in male and female BALB/c mice with coxsackievirus group B type 3. J Virol. 1994;68:5126–5132. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5126-5132.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacob E, Meiller T F, Nauman R K. Detection of elevated serum antibodies to Treponema denticola in humans with advanced periodontitis by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Periodontal Res. 1982;17:145–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1982.tb01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson B D, Engel D. Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis: a review of diagnosis, etiology and treatment. J Periodontol. 1986;57:141–150. doi: 10.1902/jop.1986.57.3.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kesavalu L, Ebersole J L, Machen R L, Holt S C. Porphyromonas gingivalis virulence in mice: induction of immunity to bacterial components. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1455–1464. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1455-1464.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kesavalu L, Holt S C, Ebersole J L. Environmental modulation of oral treponeme virulence in a murine model. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2783–2789. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2783-2789.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kesavalu L, Holt S C, Crawley R R, Borinski R, Ebersole J L. Virulence of Wolinella recta in a murine abscess model. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2806–2817. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2806-2817.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kesavalu L, Walker S, Holt S C, Crawley R R, Ebersole J L. Virulence characteristics of oral treponemes in a murine model. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5096–5102. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5096-5102.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai C-H, Listgarten M A, Evian C I, Dougherty P. Serum IgA and IgG antibodies to Treponema vincentii and Treponema denticola in adult periodontitis, juvenile periodontitis and periodontally healthy subjects. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:752–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindblad E B, Elhay M J, Silva R, Appelberg R, Anderson P. Adjuvant modulation of immune responses to tuberculosis subunit vaccines. Infect Immun. 1997;65:623–629. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.623-629.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loesche W J. The role of spirochetes in periodontal disease. Adv Dent Res. 1988;2:275–283. doi: 10.1177/08959374880020021201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mangan D F, Laughon B E, Bower B, Lopatin D E. In vitro lymphocyte blastogenic responses and titers of humoral antibodies from periodontitis patients to oral spirochete isolates. Infect Immun. 1982;37:445–451. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.2.445-451.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez-Abrajan D M. Differential specific humoral response of susceptible and resistant mice infected with Mycobacterium lepraemurium. Rev Latinoamericana Microbiol. 1993;35:171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mountford A P, Fisher A, Wilson R A. The profile of IgG1 and IgG2a antibody responses in mice exposed to Schistosoma mansoni. Parasite Immunol. 1994;16:521–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1994.tb00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray P A. HIV disease as a risk factor for periodontal disease. Compendium. 1994;15:1052–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paul W E, Seder R A. Lymphocyte responses and cytokines. Cell. 1994;76:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90332-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radolf J D, Fehniger T E, Silverblatt F J, Miller J N, Lovett M A. The surface of virulent Treponema pallidum: resistance to antibody binding in the absence of complement and surface association of recombinant antigen 4D. Infect Immun. 1986;52:579–585. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.2.579-585.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rao T D, Fisher A, Frey A B. CD+ Th2 T cells elicited by immunization confers protective immunity to experimental Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Ann NY Med Sci. 1994;730:364–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rice M, Fitzgerald T J. Immune immobilization of Treponema pallidum: antibody and complement interactions revisited. Can J Microbiol. 1985;31:1147–1151. doi: 10.1139/m85-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riviere G R, Weisz K S, Simonson L, Lukehart S A. Pathogen-related spirochetes identified within gingival tissue from patients with acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2653–2657. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2653-2657.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riviere G R, Weisz K S, Adams D F, Thomas D D. Pathogen-related oral spirochetes from dental plaque are invasive. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3377–3380. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3377-3380.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rook G A, Stanford J L. Adjuvants, endocrines and conserved epitopes; factors to consider when designing “therapeutic vaccines.”. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1995;17:91–102. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(94)00091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenstein D I, Riviere G R, Elott K. HIV-associated periodontal disease: new oral spirochete found. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993;124:76–80. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1993.0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saunders J M, Folds J D. Humoral response of the mouse to Treponema pallidum. Genitourin Med. 1985;61:221–229. doi: 10.1136/sti.61.4.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seiler K P, Weis J J. Immunity to Lyme disease: protection, pathology and persistence. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:503–509. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simonson L G, Goodman C H, Morton H E. Quantitative immunoassay of Treponema denticola serovar in adult periodontitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1493–1496. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.7.1493-1496.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smibert R M, Burmeister J A. Treponema pectinovorum sp. nov. isolated from humans with periodontitis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1983;33:852–856. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smibert R M, Johnson J L, Ranney R R. Treponema socranskii sp. nov., Treponema socranskii subsp. socranskii subsp. nov., Treponema socranskii subsp. buccale subsp. nov., and Treponema socranskii subsp. paredis subsp. nov. isolated from humans with experimental gingivitis and periodontitis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1984;34:456–462. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Snapper C M, Paul W E. Inteferon-γ and B cell stimulatory factor-1 reciprocally regulate IgG isotype production. Science. 1987;236:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.3107127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tew J G, Marshall D R, Moore W E C, Best A M, Palcanis K G, Ranney R R. Serum antibody reactive with predominant organisms in the subgingival flora of young adults with generalized severe periodontitis. Infect Immun. 1985;48:303–311. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.2.303-311.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tew J G, Smibert R M, Scott E A, Burmeister J A, Ranney R R. Serum antibodies in young adult humans reactive with periodontitis associated treponemes. J Periodontal Res. 1985;20:580–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1985.tb00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Umemoto T, Nakazawa F, Hoshino E, Okada K, Fukunaga M, Namikawa I. Treponema medium sp. nov., isolated from human subgingival dental plaque. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:67–72. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-1-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walker S G, Ebersole J L, Holt S C. Identification, isolation, and characterization of the 42-kilodalton major outer membrane protein (MompA) from Treponema pectinovorum ATCC 33768. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6441–6447. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6441-6447.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Westbay T D, Dascher C C, Hsia R, Zauderer M, Bavoil P M. Deviation of immune response to Chlamydia psittaci outer membrane protein in lipopolysaccharide-hyporesponsive mice. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1391–1393. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1391-1393.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wicher K, Wos S M, Wicher V. Kinetics of antibody response of pathogenic and nonpathogenic treponemes in experimental syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1986;13:251–257. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198610000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wyss C, Choi B K, Schupbach P, Guggenheim B, Gobel U B. Treponema maltophilum sp. nov., a small oral spirochete isolated from human periodontal lesions. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:745–752. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-3-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wyss C, Choi B K, Schupbach P, Guggenheim B, Gobel U B. Treponema amylovorum sp. nov., a saccharolytic spirochete of medium size isolated from an advanced human periodontal lesion. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:842–845. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-3-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]