Summary

Background

Many of the 10–20% percent of COVID-19 survivors who develop Post COVID-19 Condition (PCC, or Long COVID) describe experiences suggestive of stigmatization, a known social determinant of health. Our objective was to develop an instrument, the Post COVID-19 Condition Stigma Questionnaire (PCCSQ), with which to quantify and characterise PCC-related stigma.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study to assess the reliability and validity of the PCCSQ. Patients referred to our Post COVID-19 Clinic in the Canadian City of Edmonton, Alberta between May 29, 2021 and May 24, 2022 who met inclusion criteria (attending an academic post COVID-19 clinic; age ≥18 years; persistent symptoms and impairment at ≥ 12 weeks since PCR positive acute COVID-19 infection; English-speaking; internet access; consenting) were invited to complete online questionnaires, including the PCCSQ. Analyses were conducted to estimate the instrument's reliability, construct validity, and association with relevant instruments and defined health outcomes.

Findings

Of the 198 patients invited, 145 (73%) met inclusion criteria and completed usable questionnaires. Total Stigma Score (TSS) on the PCCSQ ranged from 40 to 174/200. The mean (SD) was 103.9 (31.3). Cronbach's alpha was 0.97. Test-retest reliability was 0.92. Factor analysis supported a 6-factor latent construct. Subtest reliabilities were >0.75. Individuals reporting increased TSS occurred across all demographic groups. Increased risk categories included women, white ethnicity, and limited educational opportunities. TSS was positively correlated with symptoms, depression, anxiety, loneliness, reduced self-esteem, thoughts of self-harm, post-COVID functional status, frailty, EQ5D5L score, and number of ED visits. It was negatively correlated with perceived social support, 6-min walk distance, and EQ5D5L global rating. Stigma scores were significantly increased among participants reporting employment status as disabled.

Interpretation

Our findings suggested that the PCCSQ is a valid, reliable tool with which to estimate PCC-related stigma. It allows for the identification of patients reporting increased stigma and offers insights into their experiences.

Funding

The Edmonton Post COVID-19 Clinic is supported by the University of Alberta and Alberta Health Services. No additional sources of funding were involved in the execution of this research study.

Keywords: Long COVID, Post COVID-19 condition, PCC, Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Stigma, Health related stigma, Stigmatization, Stigma as a social determinant of health

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We conducted a search in PubMed for English studies published between January 1, 2012 and June 30, 2022 focusing on health-related stigma, and a second search in PubMed for English studies published between May 1, 2020 and June 30, 2022 addressing stigma among individuals with post COVID-19 condition. The following search terms were utilised: stigma; health-related stigma; long COVID-19; post COVID-19 condition; measuring health-related stigma. By the end of 2020, it was apparent that a worrisome proportion of COVID-19 survivors were experiencing health difficulties that persisted for more than 12 weeks following acute infection, thus meeting criteria of Post COVID-19 Condition (PCC). It was speculated that stigma, now recognised as a social determinant of health, was imposing an additional burden on PCC patients and could be undermining efforts to address this disorder at the level of both the individual and populations.

Added value of this study

This study presents an instrument designed to assess the specific form of stigma arising from post-COVID-19 condition, with items tailored to its unique symptoms and social context. Both are distinct in important ways from other forms of health-related stigma that have been the focus of instrumentation and measurement. Additionally, the study provides estimates of multiple aspects of the instrument's reliability and validity.

Implications of all the available evidence

People with health-related conditions—especially those that are contagious and unconcealable—experience forms of discrimination that affect their quality life and their willingness to seek treatment. Health professionals have designed interventions that mitigate the stigma, and assessment, pre-and post, has been pivotal in their success. Our findings suggest that the PCCSQ can fulfill this function in the context of PCC, and it can contribute to our understanding of PCC-related stigma generally.

Introduction

Essential to the scientific understanding of stigma is our capacity to observce and measure it.1

Stigma, as defined by Goffman, is an attribute – physical mark, condition, character trait, or status – that is deeply discrediting.2 Stigmatization is the process, embedded within social relationships, that enables the devaluation of people in possession of these attributes through labelling and stereotypes.3 Discrimination can be thought of as behaviours that endorse stereotypes and disadvantage those so labelled.3

The Stigma Complex and the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework are examples of theoretical models used to outline the conditions and interactions responsible for these emergent social phenomena, which can manifest at many levels ranging from the individual to groups, organizations, institutions, and entire societies.3,4

The potential consequences of stigmatization are substantial, and include psychological stress, fear, anxiety, depression, and self-harm; continuing risk of transmission of infectious diseases; delays in diagnosis and initiation of treatment; more rapid advancement of the underlying condition; increased disability; increased morbidity; poorer prognosis; increased mortality; restricted participation in social activities, including loss of life chances (education, social benefits, employment) and, undermining of public health efforts.2, 3, 4, 5, 6

COVID-19 is the clinical syndrome caused by SARS-CoV-2, a new viral pathogen that has spread rapidly around the globe since 2019. Acute COVID-19 ranges in severity from an asymptomatic, self-limited infection to an overwhelming multisystem critical illness with significant risk of mortality.7

Post COVID-19 Condition (PCC, or Long COVID) is defined by the persistence of symptoms beyond 12 weeks following the acute illness. At least 10–20% of COVID-19 survivors meet this definition.8

Clearly, acute COVID-19 can stigmatise. Like Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) or tuberculosis, it is caused by an infectious agent transmitted through close contact with others. Like Parkinson's disease, the body of knowledge surrounding pathogenesis is complex and incomplete. And, like obesity, epilepsy, mental illness, and many other conditions, mis- and disinformation, often perpetuated through social media, can fuel public attitudes.9 Several reports have confirmed stigma among patients with or quarantined for acute COVID-19. Another study found that the majority of health care workers, merely by providing care to patients with acute COVID-19, experienced stigmatization. One-third rated this as severe.10

Do people with PCC also experience stigmatization? Our experience in an academic post COVID-19 clinic, operational since June 2020, suggested this could be the case. Almost immediately, clinic patients began describing experiences similar to the stigmatization and discrimination reported by researchers studying other discrediting medical conditions. Patients were discouraged from returning to work, subjected to excessive isolation precautions, alienated from family, friends, and co-workers, or accused of malingering or laziness.

More recently, reports describing PCC-related stigma have started to appear in the medical literature. Existing and new scales have been administered to COVID-19 survivors in an attempt to identify and measure this phenomenon.11,12 Researchers are beginning to explore questions such as contributing sociologic factors, who might be affected, and promising preventive responses.13 All this suggests that PCC too has the potential to stigmatise.

To better understand the experience of COVID-19 survivors, we developed an instrument (the Post COVID-19 Condition Stigma Questionnaire, or PCCSQ) to detect and quantify PCC-related stigma. The purpose of this study is to report the reliability and validity of this novel instrument, and to offer some insights into PCC-related stigma.

Methods

Instrument development

At the time of study inception, instruments designed to estimate stigma in patients with PCC were not available. Using the Short HIV Stigma Scale14 and our patients’ relayed experiences, we developed a 40-item, self-reported questionnaire, the PCCSQ.

Our clinic research group based item selection and design on the dimensionality of the HIV instrument. This instrument has been employed in numerous studies of HIV-related stigma and has been adapted to measure other forms of health-related stigma, including that associated with COVID-19. It was postulated that the stigma associated with HIV, COVID-19, and their sequelae could share similar latent constructs. Additional items were added to sample other possible factors, such as fear of COVID-19, impact on social relationships, impact on employer-employee dynamics, or reaction of health providers.

A five-point Likert scale was utilised to record participant responses to each item: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neutral (3), agree (4), strongly agree (5). Total Stigma Score (TSS) was defined as the sum of numeric responses for all 40 items. The lowest possible score was 40 (no stigma) while the highest was 200 (maximum stigma). Respondents were also asked to rate their perception of PCC-related stigma on a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 0 (no stigma) – 10 (maximum stigma). The PCCSQ was designed for grade 8 readability in English.

Study design and population

A prospective cohort study was undertaken to evaluate the soundness of the PCCSQ instrument. We included patients referred to our Post COVID-19 Clinic who met the following criteria: English speaking; age ≥18-years; a positive Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) test for SARS-CoV-2; at least 12 weeks since onset of acute infection; internet access; willingness to provide informed consent.

Study protocol

The study protocol was approved by the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board (Pro00107350).

Patients assessed in the University of Alberta/Alberta Health Services Post COVID-19 Clinic in the Canadian city of Edmonton, Alberta were made aware of this study. Interested individuals received an email link to information describing the study, and were given the opportunity to have their questions answered by the principal investigator. Informed consent was documented electronically.

Once enrolled, study participants received an email link to a battery of on-line instruments, including: a sociodemographic data questionnaire, a rating of acute COVID-19 severity (1: able to stay home; 2: treated in Emergency Department (ED); 3: hospitalised; 4: required Intensive Care (ICU)), the PCCSQ, the UCLA Loneliness Scale,15 the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS),16 the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),17 the Post-COVID Functional Scale (PCFS),18 and the European Quality of Life – 5 Dimensions – 5 Levels (EQ5D5L).19

Instruments validated to quantify PCC symptoms were not available at the time of study inception. Therefore, a modified version of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale Revised (ESAS-r)20 was utilised to gather symptom data. Participants were asked to rate the severity of the standard ESAS-r symptoms on a VAS from 0 (none) to 10 (worst possible). The modification allowed participants to list and rate additional symptoms not included in the ESAS-r. From this, total number of symptoms and mean symptom severity could be calculated. An additional metric, symptom burden, was defined as the sum of the VAS scores of all reported symptoms.

Ten percent of respondents were asked to repeat the PCCSQ within 24–72 h.

At the time of initial survey completion, electronic medical records of consenting participants were reviewed for the following: Clinical Frailty Scale21 score, Charlson Comorbidity Index22 score, and 6-min walk distance (6MWD). Published reference equations were used to convert 6MWD to percent predicted.23

The medical records of consenting participants were reviewed again in the spring of 2022 for clinical outcomes during the PCC phase (defined as the time between date of COVID-19 PCR positivity plus 12 weeks and date of follow-up chart review), including frequency of specialist referrals, frequency of ED visits, frequency of hospitalization, and total days spent in hospital.

Approval was obtained for all validating instruments.

No additional sources of funding were involved in the execution of this research study.

Statistical analysis

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap24 electronic data capture tools hosted by the Women & Children's Health Research Institute at the University of Alberta. R Packages25 was used to conduct all statistical analyses. Frequency distributions for each variable were prepared and inspected to ensure that the data met assumptions for our analysis procedures. Measures of central tendency and variability appropriate to the distributions were calculated, including mean, mode, standard deviations, and ranges. Our principal research question addressed the reliability and validity of the data generated by the PCCSQ. To this end, we conducted item analysis on the responses to the 40 items, Cronbach's alpha and split-half procedures to estimate internal consistency of the instrument on the whole and of its dimensions, an exploration of test-retest reliability with an 8-day re-administration to a subset of the participants, and exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses to explore dimensionality of the data using a Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (DWLS) estimator which does not assume a normal distribution of Likert-scaled data. The factor analyses were prefaced with a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test to determine appropriateness of the dataset for factor analysis and a Bartlett's test of sphericity to confirm that the correlation was not an identity matrix. To explore the relationships between TSS and other variables for which data was collected, we calculated Pearson correlation coefficients for continuous variables and ANOVA, the Wilcoxson signed rank test, and the t-test for categorical variables.

Role of the funding source

There was no funding source for this study. RD, LR, YC, GY, MS, DF, JT, RV, CL, AL, EW, MS, and GF had access to the study dataset and agreed to submit for publication.

Results

Participants

Between May 29, 2021 and May 24, 2022, 198 patients were invited to participate in this study; 165 (83%) provided informed consent; 151 (76%) completed the entire battery of study instruments. Five patients did not have PCR confirmation of a COVID-19 infection; 1 patient was enrolled at less than 12 weeks from the onset of acute symptoms. Following these exclusions, 145 patients (73%) were included in the analysis. The response rate to PCCSQ items within this subgroup was 100%.

Participants completed the study questionnaires a mean of 322 (96–675) days following acute infection as defined by COVID-19 PCR positivity, and a mean of 601 (457–797) days following the World Health Organization's declaration of a global pandemic on March 11, 2020. Electronic medical record review allowed for assessment of clinical outcomes over a mean of 16.0 (range 4.5–25.2) months following time of PCC diagnosis. The time between the earliest and most recent documented acute COVID-19 infection was 596 days (March 12, 2020; October 29, 2021).

The age of participants ranged from 22 to 80 years, with a mean (SD) of 48.2 (12.2). Ninety-six (66.2%) identified as women; 108 (74.5%) were white; 28 (19.3%) were non-white, non-indigenous; 8 (5.5%) identified as Indigenous (First Nations/Inuit/Metis). Body Mass Index (BMI) ranged from 18.3 to 60.5 kg/m2, with a mean (SD) of 31.7 (8.3).

Although the majority of patients were able to manage at home during their acute COVID-19 infection, 24 (16.5%) visited an ED but were subsequently able to return home, 24 (16.5%) required admission to hospital, and 19 (13.1%) spent time in ICU (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at time of post COVID-19 condition stigma questionnaire completion.

| Participants | 145 | |

| Time between survey and PCR positivity (days) | 322 (96–675) | |

| Time between survey completion and start of pandemic (days) | 601 (457–797) | |

| Age (years) | 48.2 (12.2), 22–80 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.7 (8.3), 18.3–60.5 | |

| Gender | Woman | 96 (66.2%) |

| Man | 47 (32.4%) | |

| Not Disclosed | 2 (1.4%) | |

| Ethnicity | White | 108 (74.5%) |

| Visible minority | 28 (19.3%) | |

| First Nations | 8 (5.5%) | |

| Not Disclosed | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Level of care (acute COVID-19) | Home | 78 (53.7%) |

| Emergency Department | 24 (16.5%) | |

| Medical Ward | 24 (16.5%) | |

| Intensive Care Unit | 19 (13.1%) | |

| Marital status | Married | 90 (62.1%) |

| Common Law | 3 (2.1%) | |

| Separated/Divorced | 22 (15.2%) | |

| Widow/Widower | 2 (1.4%) | |

| Single | 26 (17.9%) | |

| Not disclosed | 2 (1.4%) | |

| Occupation (as of January 2020) | Working | 122 (84.1%) |

| Disabled | 5 (3.4%) | |

| Retired | 9 (6.2%) | |

| Not Employed, Looking | 4 (2.8%) | |

| Not Employed | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Student | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Parental Leave | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Not Disclosed | 3 (2.1%) | |

| Occupation (at time of survey completion) | Working | 94 (64.8%) |

| Disabled | 30 (20.7%) | |

| Retired | 8 (5.5%) | |

| Not Employed, Looking | 5 (3.4%) | |

| Not Employed | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Student | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Parental Leave | 2 (2.1%) | |

| Not Disclosed | 4 (2.8%) | |

| Education | Some High School | 8 (5.5%) |

| High School or Equivalent | 30 (20.7%) | |

| Diploma/Trade | 52 (34.9%) | |

| Bachelor's | 38 (26.2%) | |

| Graduate | 12 (8.3%) | |

| Not disclosed | 5 (3.4%) | |

| Annual household income | <25 k | 5 (3.4%) |

| 25–49 k | 15 (10.3%) | |

| 50–99 k | 50 (34.5%) | |

| 100–149 k | 29 (20.0%) | |

| >150 k | 25 (17.2%) | |

| Not disclosed | 21 (14.5%) | |

| Geographic location | Urban/suburban | 126 (86.9%) |

| Rural | 18 (12.4%) |

COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; PCR, Polymerase Chain Reaction; BMI, Body Mass Index; k, thousand.

Item analysis

Of a possible total score of 200, ratings on the PCCSQ ranged from 40 to 174, with a mean (SD) of 103.9 (31.3). Global ratings of perceived stigma ranged from 0 to 10/10, with a mean (SD) of 4.1 (3).

The correlation between PCCSQ TSS and global rating of stigma was statistically significant (r = 0.739, p < 0.001).

Item discrimination ranged from 0.37 to 0.80, with a mean (SD) of 0.63 (0.12).

Participants agreed or strongly agreed with 30% of items (range: 0–90%). Five percent did not agree or strongly agree with any of the items. Twenty-one percent agreed or strongly agreed with at least 50% of items.

Factor analysis

The KMO test demonstrated an overall measure of sampling adequacy of 0.93. KMO values for individual items ranged from 0.81 to 0.97. Bartlett's K-squared test was 200.2, df = 39, p < 0.001, indicating that not all items have the same variance.

Exploratory factor analysis found eight factors with Eigen value greater than 1. Inspection of 1- to 8-factor models suggested that a 6-factor solution accounted for the optimal amount of variance within the dataset (51%).

Confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated a satisfactory model-data fit (Comparative Fit Index = 0.996, Tucker–Lewis Index = 0.996, Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation = 0.049, Standardised Root Mean Squared Residual = 0.067). All 40 items loaded highly onto each of the corresponding factors, including negative self-image (items 2, 5, 8, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 26, 34), social isolation (10, 11, 13, 15, 19, 29, 33), disclosure concerns (4, 9, 21, 28, 30, 35), fear of PCC (7, 23, 31, 32, 36), COVID-19 stereotyping (25, 38, 39, 40), and concerns with public attitudes about PCC (1, 3, 6, 17, 24, 27, 37). Standardised factor loading varied from 0.491 to 0.942, with a mean (SD) of 0.767 (0.122) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Latent construct of post COVID-19 condition stigma questionnaire: Summary of 6-factor confirmatory analysis.

| Latent Variable | Item | Estimate of Factor Loading∗ | Standard Error | z-value | p of z-value | Standardized; Latent Factor Variance = 1.0 | Standardized; Latent Factor and Observed Variable Variance = 1.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Self-Image | 2 | 0.636 | 0.053 | 11.953 | 0.000 | 0.636 | 0.636 |

| 5 | 0.711 | 0.048 | 14.848 | 0.000 | 0.711 | 0.711 | |

| 8 | 0.858 | 0.028 | 30.543 | 0.000 | 0.858 | 0.858 | |

| 12 | 0.674 | 0.055 | 12.148 | 0.000 | 0.674 | 0.674 | |

| 14 | 0.733 | 0.043 | 17.001 | 0.000 | 0.733 | 0.733 | |

| 16 | 0.748 | 0.042 | 17.707 | 0.000 | 0.748 | 0.748 | |

| 18 | 0.663 | 0.052 | 12.839 | 0.000 | 0.663 | 0.663 | |

| 20 | 0.750 | 0.043 | 17.505 | 0.000 | 0.750 | 0.750 | |

| 22 | 0.741 | 0.041 | 18.016 | 0.000 | 0.741 | 0.741 | |

| 26 | 0.916 | 0.022 | 41.141 | 0.000 | 0.916 | 0.916 | |

| 34 | 0.926 | 0.025 | 36.862 | 0.000 | 0.926 | 0.926 | |

| Social Isolation | 10 | 0.761 | 0.034 | 22.144 | 0.000 | 0.761 | 0.761 |

| 11 | 0.855 | 0.029 | 29.930 | 0.000 | 0.855 | 0.855 | |

| 13 | 0.816 | 0.030 | 26.953 | 0.000 | 0.816 | 0.816 | |

| 15 | 0.842 | 0.027 | 31.309 | 0.000 | 0.842 | 0.842 | |

| 19 | 0.873 | 0.026 | 34.111 | 0.000 | 0.873 | 0.873 | |

| 29 | 0.860 | 0.029 | 29.596 | 0.000 | 0.860 | 0.860 | |

| 33 | 0.839 | 0.031 | 27.212 | 0.000 | 0.839 | 0.839 | |

| Disclosure Concerns | 4 | 0.796 | 0.042 | 18.985 | 0.000 | 0.796 | 0.796 |

| 9 | 0.824 | 0.033 | 25.111 | 0.000 | 0.824 | 0.824 | |

| 21 | 0.926 | 0.020 | 45.407 | 0.000 | 0.926 | 0.926 | |

| 28 | 0.793 | 0.035 | 22.544 | 0.000 | 0.793 | 0.793 | |

| 30 | 0.863 | 0.028 | 30.768 | 0.000 | 0.863 | 0.863 | |

| 35 | 0.726 | 0.042 | 17.117 | 0.000 | 0.726 | 0.726 | |

| Fear of PCC | 7 | 0.515 | 0.075 | 6.819 | 0.000 | 0.515 | 0.515 |

| 23 | 0.618 | 0.055 | 11.333 | 0.000 | 0.618 | 0.618 | |

| 31 | 0.798 | 0.038 | 21.075 | 0.000 | 0.798 | 0.798 | |

| 32 | 0.841 | 0.037 | 22.889 | 0.000 | 0.841 | 0.841 | |

| 36 | 0.942 | 0.028 | 33.747 | 0.000 | 0.942 | 0.942 | |

| COVID-19 Stereotypes | 25 | 0.514 | 0.064 | 8.087 | 0.000 | 0.514 | 0.514 |

| 38 | 0.582 | 0.065 | 8.2954 | 0.000 | 0.582 | 0.582 | |

| 39 | 0.878 | 0.027 | 32.756 | 0.000 | 0.878 | 0.878 | |

| 40 | 0.918 | 0.030 | 30.502 | 0.000 | 0.918 | 0.918 | |

| Concern re: Attitudes | 1 | 0.704 | 0.045 | 15.502 | 0.000 | 0.704 | 0.704 |

| 3 | 0.693 | 0.045 | 15.259 | 0.000 | 0.693 | 0.693 | |

| 6 | 0.491 | 0.066 | 7.433 | 0.000 | 0.491 | 0.491 | |

| 17 | 0.791 | 0.032 | 24.964 | 0.000 | 0.791 | 0.791 | |

| 24 | 0.798 | 0.033 | 24.253 | 0.000 | 0.798 | 0.798 | |

| 27 | 0.885 | 0.025 | 35.909 | 0.000 | 0.885 | 0.885 | |

| 37 | 0.539 | 0.059 | 9.140 | 0.000 | 0.539 | 0.539 |

Comparative Fit Index = 0.996, Tucker–Lewis Index = 0.996, Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation = 0.049, Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual = 0.067.

Reliability

Cronbach's alpha for the PCCSQ was 0.97. Average split half reliability for the instrument was 0.97 (CI: 0.93, 0.98). Subtest reliability ranged from 0.77 to 0.92 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Overall and subtest reliability of post COVID-19 condition stigma questionnaire.

| Test | Average split half, CI [ ] | Internal consistency |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Self-Image | 0.91 [0.87, 0.93] | 0.92 |

| Social Isolation | 0.92 [0.86, 0.91] | 0.91 |

| Disclosure Concerns | 0.90, [0.86, 0.93] | 0.89 |

| Fear of PCC | 0.76, [0.71, 0.81] | 0.81 |

| COVID-19 Stereotypes | 0.77, [0.76, 0.79] | 0.77 |

| Concern About Public Attitudes | 0.84, [0.78, 0.86] | 0.83 |

| Overall | 0.97, [0.93, 0.98] | 0.97 |

COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; PCC, Post COVID-19 Condition.

Nineteen patients (13%) completed the PCCSQ a second time. Mean time between test re-test was 3.7 (0.7–8.0) days. Test-retest reliability was 0.92.

Construct and face validity

Three demographic characteristics were associated with a significantly higher value in the TSS on the PCCSQ, including female vs male gender (t = 5.592, p < 0.005), White vs Non-White ethnic background (t = 5.729, p < 0.018), and limited vs advanced educational opportunities (t = 3.332, p < 0.007).

Individual participants had an average of 6.7 symptoms (range 0–12). Fifty-four unique symptoms were reported among the 145 members of the PCC cohort.

TSS correlated significantly with number of symptoms (r = 0.547, p < 0.001); mean symptom intensity (r = 0.559, p < 0.001); symptom burden (r = 0.635, p < 0.001); ESAS-r depression (r = 0.580, p < 0.001); ESAS-r anxiety (r = 0.561, p < 0.001); PHQ-9 total (r = 0.640, p < 0.001); EQ5D5L depression/anxiety (r = 0.539, p < 0.001), MSPSS social support (r = - 0.236, p = 0.004); UCLA loneliness (r = 0.605, p < 0.001); reduced self-esteem (r = 0.551, p < 0.001), and thoughts of self-harm (r = 0.280, p < 0.001).

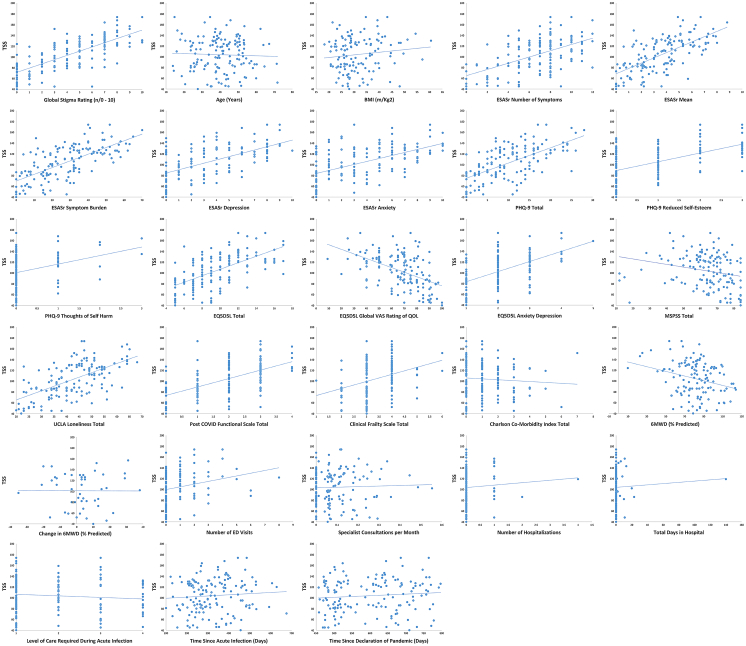

Post-COVID functional status (r = 0.566, p < 0.001), frailty (r = 0.348, p < 0.001), 6-min walk distance at enrollment as percent predicted (r = - 0.279, p = 0.002), quality of life (EQ5D5L total: 0.613, p < 0.001; EQ5D5L global rating: - 0.502, p < 0.001), and number of ED visits (r = 0.245, p = 0.003) also correlated significantly with TSS (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Scatter Plots of Total Stigma Score versus Validation Variables. Total Stigma Score (TSS) was defined as the sum of numeric responses for all 40 items on the Post COVID-19 Condition Stigma Questionnaire. A modified version of the ESAS-r was used in this study. The modification allowed participants to list and rate additional symptoms not included in the ESAS-r. Symptom burden was defined as the sum of the VAS scores of all reported symptoms. COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; BMI: Body Mass Index; ESAS-r: revised Edmonton Symptom Scale; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; EQ5D5L: European Quality of Life – 5 Dimensions – 5 Levels; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; MSPSS: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; UCLA: University of California, Los Angeles; 6MWD: 6-Minute Walk Distance; ED: Emergency Department.

Significantly more participants reported their post COVID-19 employment status as disabled compared to their pre-pandemic status (20.7% vs 3.4%, V = 270, p < 0.001). Mean TSS was significantly higher among participants who reported their employment status as disabled after having had COVID-19 compared to those who did not (disabled: 123.6 vs nondisabled: 99.0, t = - 4.5773, df = 59.956, p < 0.001).

There was no association between TSS and age, BMI, level of care during acute infection, number of comorbidities, time since acute COVID-19 infection, time since declaration of pandemic, number of specialist referrals, or frequency of hospitalization (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation of total stigma score from post COVID-19 condition stigma questionnaire with continuous variables.

| Name | n | R | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 145 | −0.040 | 0.632 |

| BMI | 145 | 0.127 | 0.156 |

| ESAS-r Total Score | 145 | 0.683 | <0.001 |

| ESAS-r Number of symptoms | 145 | 0.547 | <0.001 |

| ESAS-r Mean Score | 145 | 0.661 | <0.001 |

| ESAS-r Symptom Burden | 145 | 0.635 | <0.001 |

| ESAS-r Depression | 145 | 0.580 | <0.001 |

| ESAS-r Anxiety | 145 | 0.561 | <0.001 |

| PHQ-9 Total | 145 | 0.640 | <0.001 |

| PHQ-9 Reduced Self-Esteem | 145 | 0.551 | <0.001 |

| PHQ-9 Thoughts of Self-Harm | 145 | 0.280 | <0.001 |

| EQ5D5L Total Score | 145 | 0.613 | <0.001 |

| EQ5D5L Global VAS Rating of QOL | 145 | −0.502 | <0.001 |

| EQ5D5L Depression/Anxiety | 145 | 0.539 | <0.001 |

| MSPSS | 145 | −0.236 | 0.004 |

| UCLA Loneliness Score | 145 | 0.605 | <0.001 |

| Post COVID-19 Functional Scale | 145 | 0.566 | <0.001 |

| Clinical Frailty Score | 140 | 0.348 | <0.001 |

| Change in 6MWD Over Time | 49 | −0.0266 | 0.065 |

| 6MWD as Percent Predicted | 126 | −0.079 | 0.002 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 145 | −0.072 | 0.390 |

| Number of ED Visits | 144 | 0.245 | 0.003 |

| Number of Specialist Consultations | 144 | 0.036 | 0.665 |

| Number of Hospitalizations | 144 | 0.066 | 0.435 |

| Total Days in Hospital | 144 | 0.044 | 0.597 |

| Level of Care During Acute Infection | 145 | −0.102 | 0.224 |

| Time Since Acute COVID-19 | 145 | 0.079 | 0.344 |

| Time Since Declaration of Pandemic | 145 | 0.094 | 0.260 |

Total Stigma Score (TSS) was defined as the sum of numeric responses for all 40 items on the Post COVID-19 Condition Stigma Questionnaire.

A modified version of the ESAS-r was used in this study. The modification allowed participants to list and rate additional symptoms not included in the ESAS-r. Symptom burden was defined as the sum of the VAS scores of all reported symptoms.

COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; BMI, Body Mass Index; ESAS-r, revised Edmonton Symptom Scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; EQ5D5L, European Quality of Life – 5 Dimensions – 5 Levels; VAS, Visual Analog Scale; MSPSS, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles; 6MWD, 6-Minute Walk Distance; ED, Emergency Department.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the PCCSQ has high overall, split-half, and subtest reliabilities. Despite retests being completed an average of almost four days following first administration, and despite the large number of items, retest reliability was also high. These findings indicate acceptable internally consistency.

Item discrimination was good across all 40 items, indicating clear and unambiguous item construction. The 40 items of the PCCSQ checklist seemed to cohere into six latent dimensions, labelled: negative self-image, social isolation, disclosure concerns, fear of PCC, COVID-19 stereotyping, and concerns with public attitudes. The dimensionality of the PCC-related stigma construct is analogous to those described in other discrediting medical conditions.

Our results suggest that the PCCSQ provides a valid measure of PCC-related stigma, with evidence of construct and face validity. PCCSQ scores related in predictable patterns to a number of other relevant variables. For example, 54 distinct symptoms were reported by study participants. Fatigue, drowsiness, shortness of breath, pain, anxiety, and depression were most frequent. These findings are similar to reports in the long COVID-19 literature.26 Stigma scores were significantly associated with symptom number, intensity, and burden.

Similarly, measures demonstrating reduced functional status (PCFS, 6MWD) and increased frailty (CFS) were significantly associated with increased stigma scores. One possible explanation is that symptoms (discreditable or concealable stigma) and/or impaired function (discredited or unconcealable stigma), by linking the sufferer to a potentially life-altering and poorly understood disease, constitute a substantial portion of the mark of PCC.

Based upon our results, PCC-related stigma appears to be a pervasive but variable phenomenon. A range of stigma scores were found in all demographic categories. Highest risk occurred among individuals identifying as women, individuals of white ethnicity, and those with limited educational opportunity. Pescosolido et al. demonstrated unmistakable variations in the intensity and patterns of stigma from region to region.3 Could it be that regional variations in social drivers and facilitators has led to preferential stigma ‘marking’ of some groups over others? Alternatively, perhaps some individuals and groups are more prone to perceived and/or self-stigmatization?4 Further research is needed to confirm and explain these observations.

Participants with increased stigma were also noted to have reduced perception of social support and increased loneliness. These observations are congruent with the isolation and ostracism described among people with other stigmatizing medical conditions. It is not clear from our analysis, however, if perceptions of reduced social support, loneliness, anxiety, depression, decreased self-esteem, thoughts of self-harm, etc., are precursor sensitizing states, making individuals more susceptible to stigmatization, consequent states, a derivative of having been stigmatised, or a combination of both.

The above observations fit with the concept of PCC-related stigma arising from an interplay between the disease label, the psychological context of the stigmatised individual, and a predisposing social milieu as outlined by the Stigma Complex. Similarly, the inability to clearly differentiate between drivers, facilitators, and manifestations of stigma, key components of the Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework, is consistent with current theory.

Importantly, stigma scores on the PCCSQ did not correlate with age, BMI, or other comorbid conditions. This suggests that a signal distinct to that of these potentially stigmatizing conditions is being detected.

Our analysis demonstrated a strong association between PCC-related stigma and decreased quality of life. Despite completing the PCCSQ almost 1 year following their acute COVID-19 infection, the mean EQ5D5L VAS rating of quality of life among the entire cohort was 67.7, a full ten points below the index value of 77.4 for the province of Alberta.27 The impact on quality of life was more profound among participants with increased stigma scores.

Similarly, high levels of stigma among study participants were associated with loss of employment due to disability. While overwhelming symptoms and loss of function could make return to work difficult or impossible for many PCC sufferers, it is compelling to speculate about the role that co-workers, employers, institutions, the health system, and government could be playing through behaviours and policies. The observed impact of stigma on quality of life and employment status is well-documented in the stigma literature, occurs across a wide range of other conditions, and has been incorporated into existing stigma frameworks.

Our data revealed an increase in ED use among individuals reporting increased levels of stigma. There was no impact on the other health system utilization metrics studies. It is possible that stigmatised individuals avoid some aspects of routine health care while, at other times, seeking urgent assistance if mental or physical illness devolves to crisis-level. Further research will be required to determine if this is the case.

Our analysis did not demonstrate a relationship between severity of acute COVID-19 infection, as indicated by required level of care, and PCC-related stigma. Patients who were able to manage at home appear to be as susceptible as those who spent time in hospital or ICU.

There was no change in stigma scores with time since acute COVID-19 infection or time since declaration of global pandemic. These observations suggest that normalization of PCC is either not occurring or is proceeding at a very slow pace, at least within the timeframe of its existence as a defined medical condition. This is another area for investigation.

Response rates to study questionnaires were high. Completeness of data was high. The only exception to this was 6MWD data where results were available for only 126 of 145 (87%) participants.

The limited number of participants enrolled into this study is a key factor to be considered in the interpretation of results. Additionally, volunteer convenience sampling could have introduced a number of biases. Self-reporting (though an appropriate sampling strategy to estimate a perceived psychologic phenomenon), recall bias, and non-response bias are other factors that could have undermined the quality of our sampling. Despite these concerns, our cohort appears to be similar to patients described elsewhere in the PCC literature.26

The distribution of ethnic background was not equal within our cohort. As well, the majority of participants lived in an urban setting. Reference to Canadian Census data (2016) demonstrates that the make-up of our cohort closely reflects the ethnocultural and rural-to-urban make-up of Alberta, Canada.28, 29, 30 Nonetheless, the small number of participants in several subgroups limits our ability to make inferences about the experiences of people in some demographic categories, intersectionality, or system-level health outcomes.

Development of a shortened version of the PCCSQ, multicentre validation across are larger cohort, and validation in additional languages are areas for future research. Finally, this study does not provide insight into the prevention or treatment of PCC-related stigma/stigmatization.

The PCCSQ, when administered to a sample of patients attending a post COVID-19 clinic, demonstrated acceptable reliability, construct validity, and face validity. It allowed for identification of a subgroup of people reporting increased levels of stigma and offered some insights into their experiences. Our findings are consistent with current sociologic models and theory of stigma.

We believe this study could help open the door to a deeper understanding of Post COVID-19 Condition-related stigma and stigmatization.

Contributors

Ronald Damant participated in the conceptualisation of the study; the collection, curation, and analyses of data; the development of the methodology; project administration; and the preparation and revisions of the manuscript. Liam Rourke participated in the verification of the underlying data, study conceptualisation, data analyses, preparation of the original draft and revisions to the manuscript. Ying Cui participated in the verification of the underlying data, data analyses, development of the methodology, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. Grace Lam provided resources for the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Maeve Smith contributed resources for the study and participated in reviewing and editing the manuscript. Desi Fuhr was involved in data curation, software selection, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. Jacqueline Tay provided resources for the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Rhea Varughese provided resources for the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Cheryl Laratta provided resources for the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Angela Lau provided resources for the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Eric Wong provided resources for the study and I reviewed and edited the manuscript. Michael Stickland provided resources for the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Giovanni Ferarra provided resources for the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and accept responsibility to submit for publication.

Data sharing statement

The study protocol is presented in the Methods section of this article, and the complete set of data collected in this study, along with the data dictionary defining each field in the data file are available upon any reasonable request from Ron Damant (rdamant@ualberta.ca) for a period of five-years following the publication of this article. Participant data will be deidentified prior to circulation.

Declaration of interests

GL: research grants from the Alberta Lung Association and Roche Diagnostics.

GF: honoraria for educational events sponsored by AstraZeneca, Roche, and Boehringer Ingelheim; consulting fees for advisory board work with Roche and Boehringer Ingelheim. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The Edmonton Post COVID-19 Clinic is supported by the University of Alberta and Alberta Health Services. No additional sources of funding were involved in the execution of this research study. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Dwight Harley, Kate Singbeil, and Giselle Prosser for assistance with background research and administrative tasks.

Footnotes

Translation: For the French translation of the abstract see Supplementary Materials section.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101755.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Link B.G., Yang L.H., Phelan J.C., Collins P.Y. Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(3):511–541. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goffman E. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1963. Stigma : notes on the management of spoiled identity; p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pescosolido B.A., Martin J.K. The stigma complex. Annu Rev Sociol. 2015;41(1):87–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stangl A.L., Earnshaw V.A., Logie C.H., et al. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Link B., Hatzenbuehler M.L. Stigma as an unrecognised determinant of population health: research and policy implications. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2016;41(4):653–673. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3620869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatzenbuehler M.L., Phelan J.C., Link B.G. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Publ Health. 2013;103(5):813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., et al. A novel Coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . 2021. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Post COVID-19 Condition[internet]. [updated 2021 December 16]https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-post-covid-19-condition Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabarron E., Oyeyemi S.O., Wynn R. COVID-19-related misinformation on social media: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2021;99(6):455–463A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.276782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mostafa A., Sabry, Mostafa N.S. COVID-19-related stigmatization among a sample of Egyptian healthcare workers. PLoS One. 2020;15(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan Y., Zhao Y.J., Zhang Q.E., et al. COVID-19-related stigma and its sociodemographic correlates: a comparative study. Glob Health. 2021 May 7;17(1):54. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00705-4. PMID: 33962651; PMCID: PMC8103123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pantelic M., Ziauddeen N., Boyes M., O'Hara M.E., Hastie C., Alwan N.A. Long Covid stigma: estimating burden and validating scale in a UK-based sample. medRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0277317. 2022.05.26.22275585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rewerska-Juśko M., Rejdak K. Social stigma of patients suffering from COVID-19: challenges for health care system. Healthcare. 2022;10(2):292. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10020292. PMID: 35206906; PMCID: PMC8872526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reinius M., Wettergren L., Wiklander M., Svedhem V., Ekström A.M., Eriksson L.E. Development of a 12-item short version of the HIV stigma scale. Health Qual Life Outcome. 2017;15(1):115. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0691-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell D.W. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66(1):20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimet G.D., Powell S.S., Farley G.K., Werkman S., Berkoff K.A. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(3–4):610–617. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klok F.A., Boon G., Barco S., et al. The Post-COVID-19 Functional Status scale: a tool to measure functional status over time after COVID-19. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(1) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01494-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Euroqol. EQ5D5L | About [internet]. updated 2021 November 30. 2021. https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-5l-about/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hui D., Bruera E. The Edmonton symptom assessment system 25 Years later: past, present, and future developments. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;53(3):630–643. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pranata R., Henrina J., Lim M.A., et al. Clinical frailty scale and mortality in COVID-19: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2021;93 doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlson M.E., Pompei P., Ales K.L., MacKenzie C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Enright P.L., Sherrill D.L. Reference equations for the six-minute walk in healthy adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(5 Pt 1):1384–1387. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9710086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna (AT): 2013. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [internet]http://www.R-project.org/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michelen M., Manoharan L., Elkheir N., et al. Characterising long COVID: a living systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The APERSU Team . 2018. Alberta Population Norms for EQ5D5L [internet]https://apersu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Alberta-Norms-Report_APERSU-1.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 28.Statistics Canada . 2019. Aboriginal Peoples Highlight Tables. 2016 Census.https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/start [Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 29.Statistics Canada . 2019. Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables. 2016 Census.https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/start [Available from: Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- 30.Statistics Canada . 2019. 2016 Census of Canada – Population and Dwelling Release.https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/7d02c106-a55a-4f88-8253-4b4c81168e9f/resource/e435dd59-2dbd-4bf2-b5b6-3173d9bd6c39/download/2016-census-population-and-dwelling-counts.pdf [Available from: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.