Abstract

The FasG subunit of the 987P fimbriae of enterotoxigenic strains of Escherichia coli was previously shown to mediate fimbrial binding to a glycoprotein and a sulfatide receptor on intestinal brush borders of piglets. Moreover, the 987P adhesin FasG is required for fimbrial expression, since fasG null mutants are nonfimbriated. In this study, fasG was modified by site-directed mutagenesis to study its sulfatide binding properties. Twenty single mutants were generated by replacing positively charged lysine (K) or arginine (R) residues with small, nonpolar alanine (A) residues. Reduced levels of binding to sulfatide-containing liposomes correlated with reduced fimbriation and FasG surface display in four fasG mutants (R27A, R286A, R226A, and R368). Among the 16 remaining normally fimbriated mutants with wild-type levels of surface-exposed FasG, only one mutant (K117A) did not interact at all with sulfatide-containing liposomes. Four mutants (K117A, R116A, K118A, and R200A) demonstrated reduced binding to such liposomes. Since complete phenotypic dissociation between the structure and specific function of 987P was observed only with mutant K117A, this residue is proposed to play an essential role in the FasG-sulfatide interaction, possibly communicating with the sulfate group of sulfatide by hydrogen bonding and/or salt bridge formation. Residues K17, R116, K118, and R200 may stabilize this interaction.

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strains cause diarrhea by delivering one or more enterotoxins to the host after colonizing the intestinal mucosa. Effective colonization or localized multiplication of ETEC strains fully depends on their ability to adhere to intestinal epithelial cells. Studies of various ETEC fimbriae, including 987P, have documented their requirement for the induction of diarrhea in animals and human volunteers by mediating enteroadhesion (3, 19, 30, 31, 37).

The 987P fimbria is a heteropolymeric structure consisting essentially of a major subunit, FasA, and two minor subunits, FasF and FasG (2). Mutagenic inactivation of either subunit results in nonfimbriated strains, indicating that all three subunits are absolutely required for fimbrial expression (35). Export studies show that subunit translocation through the outer membrane follows a specific order, FasG being the first, FasF the second, and FasA the third type of exported subunit. Since fimbriae are thought to grow from the base, FasG was proposed to be at the tip of the fimbriae and FasF was hypothesized to link FasG to the fimbrial shaft, composed of helically arranged FasA subunits (2, 32). Similarly to other types of fimbriae, electron microscopic studies visualized minor fimbrial subunits not only at the fimbrial tip but also at intervals along the fimbrial length, suggesting that they are intermittently incorporated into the fimbrial structure during growth (2). The 987P fimbriae bind to several types of receptors in porcine intestines (6, 8, 17, 21). Interestingly, FasG mediates 987P binding both to 33-kDa and 39-kDa glycoproteins and to the glycolipid sulfatide from piglet brush borders (21, 22). FasA determines a third type of 987P-receptor interaction by recognizing intestinal ceramide monohexoside with hydroxylated fatty acids (21). In contrast to the FasG-mediated adhesion to piglet glycoproteins, interactions with the two glycolipid receptors require assembled fimbriae, suggesting cooperative effects between subunit binding sites of weak affinity or conformation-sensitive binding pockets.

In this study, residues of the 987P adhesin FasG required for the recognition of sulfatide were identified by targeting positively charged residues for alanine-scanning mutagenesis. One critical FasG residue was identified by the characterization of a nonadhesive but fimbriated fasG mutant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and reagents.

E. coli JM109 (42) was used for recombinant DNA work, and strain DMS741, a malE derivative of strain MC4100 (22), was used for Western blot studies. Nonfimbriated host strain SE5000 (36) was used for all other studies. Cultures for colony isolations or plasmid purifications were grown in L medium (36), supplemented with ampicillin (200 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml), or tetracycline (10 μg/ml) when appropriate. Medium components were purchased from Difco (Detroit, Mich.), and unless otherwise specified, reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Restriction and modification enzymes were from New England BioLabs (Beverly, Mass.). Oligonucleotides were prepared with an Applied Biosystems model 380B synthesizer.

Plasmid constructs.

Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmid pBKC1 was prepared by deleting a 430-bp BstXI fragment in fasG from pDMS158, which contains the complete fas gene cluster in the pACYC184 vector (33). Plasmid pBKC2 was constructed by cloning the fasG-containing BamHI-XhoI fragment from pDMS127 (22) into BamHI- and SalI-restricted pALTER-1 (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and/or relevant characteristics | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| SE5000 | MC4100 recA56 (Fim−) | 34 |

| DMS741 | MC4100 ΔmalE | 21 |

| 987 | O9:K103:987P (prototype F6) | 16 |

| ES1301 mutS | lacZ53 mutS201::Tn5 thyA36 rha-5 metB1 deoC IN(rrnD-rrnE) | Promega Corp. |

| Plasmids | ||

| pALTER-1 | pBR322 derivative; Aps Tcr | |

| pDMS127 | pBluescript KS fasG+ | 21 |

| pDMS158 | pACYC184 fas ΔTn1681 | 2, 31 |

| pBKC1 | pDMS158 ΔfasG (in-frame deletion of BstXI fragment in fasG) | This study |

| pBKC2 | pALTER-1 fasG | This study |

| pBKC-K17A | pBKC2 (Lys17 to Ala17 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-R27A | pBKC2 (Arg27 to Ala27 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-R116A | pBKC2 (Arg116 to Ala116 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-K117A | pBKC2 (Lys117 to Ala117 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-K118A | pBKC2 (Lys118 to Ala118 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-R123A | pBKC2 (Arg123 to Ala123 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-K181A | pBKC2 (Lys181 to Ala181 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-R182A | pBKC2 (Arg182 to Ala182 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-R200A | pBKC2 (Arg200 to Ala200 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-R226A | pBKC2 (Arg226 to Ala226 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-K233A | pBKC2 (Lys233 to Ala233 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-K269A | pBKC2 (Lys269 to Ala269 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-K277A | pBKC2 (Lys277 to Ala277 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-R286A | pBKC2 (Arg286 to Ala286 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-K309A | pBKC2 (Lys309 to Ala309 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-R323A | pBKC2 (Arg323 to Ala323 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-K335A | pBKC2 (Lys335 to Ala335 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-K359A | pBKC2 (Lys359 to Ala359 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-R368A | pBKC2 (Arg368 to Ala368 in FasG) | This study |

| pBKC-K371A | pBKC2 (Lys371 to Ala371 in FasG) | This study |

Alanine-scanning mutagenesis.

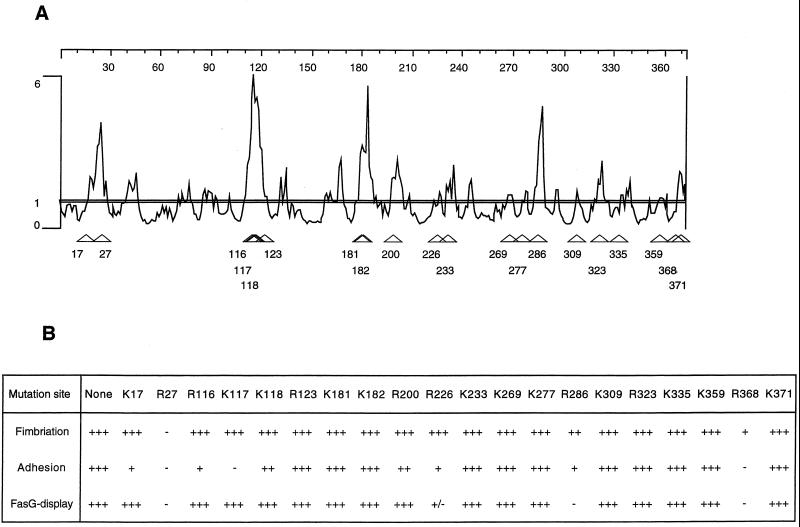

The fasG gene of pBKC2 was subjected to alanine-scanning mutagenesis (5, 13, 14). Twenty of the 31 arginine or lysine residues of processed FasG were predicted to be the most surface exposed by using the algorithm of Emini et al. (10) with a threshold value of 1 (DNASTAR, Madison, Wis.). The mutagenic oligonucleotides encoding alanine substitutions for these 20 residues were synthesized and used for in vitro mutagenesis (Fig. 1A). Mutagenesis was performed with the Altered Sites II in vitro mutagenesis system (Promega Corp.). Mutated sites were confirmed by restriction analysis, each mutagenic primer having been designed to carry a different diagnostic restriction site. Primers spaced approximately 300 bp over the entire length of fasG were synthesized and used to sequence each mutated fasG. The engineered mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing, and no additional mutations in the remaining complete fasG sequences were detected.

FIG. 1.

(A) Surface probability profile of FasG. Horizontal-axis values correspond to the amino acid residue numbers of mature FasG. Vertical-axis values are surface probabilities, as calculated by Emini et al. (10). Basic residues replaced by alanine are indicated by open arrowheads. All basic residues with a surface probability value of at least 1 (horizontal line) were mutated. (B) Fimbriation was determined by seroagglutination with anti-987P antiserum. Adhesion was determined by liposome agglutination. FasG display was determined by seroagglutination with anti-FasG antibodies. For each strain, the mutation site is characterized by the identity and position of the basic residue replaced by alanine. Seroagglutinations and liposome agglutination were quantitated as follows: +++, immediate very strong reaction; ++, strong reaction after 30 s; +, weak reaction after 1 min; +/−, very weak reaction after 1 min; −, no reaction for 2 min.

Complementation assays.

E. coli SE5000 (36) containing pBKC1, which expresses all of the Fas proteins with the exception of FasG, is nonfimbriated and nonadhesive. In contrast, SE5000/pBKC1 can be complemented for fimbriation and adhesion with fasG-containing pBKC2. Therefore, the phenotypes determined by the mutated FasG proteins were studied by complementation assays using the corresponding mutated fasG alleles expressed from the pBKC2 derivatives. For all complementation assays, the numbers of bacteria in each overnight culture were adjusted to 2 × 108 cells/ml and the copy numbers of the plasmids were analyzed by densitometric analysis using negative pictures of ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels. The copy numbers of the plasmids encoding the mutated and nonmutated FasG proteins were very similar (<2.4% variation). Therefore, the copy number did not affect the interpretation of our studies.

Seroagglutination.

Slide agglutinations were performed with preadsorbed rabbit anti-987P fimbrial antiserum or with a conformation-specific anti-FasG antibody, as described previously (2, 32, 35).

Isolation of fimbriae.

Fimbriae were isolated from wild-type clinical strain 987 (29), strain DMS741/pDMS158, and strain DMS741 containing derivatives of pBKC1 and pBKC2 essentially as described previously (22). Briefly, bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in 0.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–75 mM NaCl, and treated at 60°C for 30 min. After a subsequent centrifugation clearing step, ammonium sulfate was added to the supernatants to a 20% final concentration to precipitate the fimbrial proteins overnight on ice. The supernatants were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min, and the pellets were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 10 mM NaHPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, 2.7 mM KCl, 137 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]) or Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 154 mM NaCl). Excess ammonium sulfate was removed by ultrafiltration (Centricon 30; Amicon, Beverley, Mass.).

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Separation and analysis of fimbrial preparations were undertaken by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 12% gels (23) and Western blotting (40), as described previously (22). Relative concentrations of fimbrial FasA and FasG subunits exported by the various mutants were evaluated by Western blot analysis, enhanced chemiluminescence (Renaissance; NEN, Boston, Mass.) using previously described specific antibodies recognizing denatured FasA and FasG (2, 22), and densitometry with the NIH Image software (Division of Computer Research and Technology, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.).

Electron microscopy.

Electron microscopy of bacterial cells was performed as described previously (32). Briefly, overnight-grown bacteria were washed once in PBS, and appropriate dilutions were applied onto Formvar-coated copper grids and negatively stained for 1 min with 0.5% phosphotungstic acid (pH 4.0). Electron micrographs were obtained with a JEOL Jem 1010 transmission electron microscope and a charge-coupled device camera system (Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Danvers, Mass.) at the Biomedical Imaging Core facility, University of Pennsylvania.

Preparation of BBV.

Brush border vesicles (BBV) were prepared from small-intestinal epithelial cells of 3-day-old piglets as described previously (22). Purity of the BBV was assessed by microscopy, protein concentrations were determined (25), and BBV were used immediately or frozen at −80°C for long-term storage.

Ligand blotting assays.

Ligand blotting assays identifying the 987P receptor in the isolated and purified BBV were performed as described elsewhere (22). Briefly, BBV proteins (30 μg for fimbrial binding or 50 μg for FasG binding assays) were separated by SDS-PAGE in the absence of reducing agents and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.). After being blocked with TBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin for 3 h at room temperature, blots were incubated with fimbriae (10 μg/ml in TBS–1% BSA) isolated from the wild type or fasG mutants for 2 h at room temperature. Fimbriae were detected by using, sequentially, quaternary-structure-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) E11 (32), horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies (Organon Teknika Corp., Durham, N.C.), and enhanced chemiluminescence.

ELISA inhibition assay.

Antibody titers (50% binding) of MAb E11 against isolated 987P fimbriae were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) essentially as described previously (2). For the inhibition assays, bacterial strains were grown overnight at 37°C and washed in PBS, and bacterial densities were adjusted to an A600 of 0.5 (approximately 2.0 × 108 CFU/ml). The bacteria were twofold serially diluted in nontreated polystyrene microtiter plates (Corning Costar Corp., Oneonta, N.Y.), equal amounts of MAb E11 were added to all wells, and the plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. These mixtures were transferred to a second set of microtiter plates (Immulon 4; Dynatech Laboratories, Chantilly, Va.) previously coated with isolated 987P fimbriae (10 mg/well), and the plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The wells were washed five times with PBS, and the amounts of bound MAb E11 were detected by using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies and ortho-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Sigma). The absorbance was measured at 450 nm (microplate reader model 450; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.), and percentages of inhibition were calculated as described previously (21).

Liquid-phase binding assays with liposomes.

Sulfatide-containing liposomes were prepared by mixing cholesterol, dicetylphosphate, phosphatidylcholine, and sulfatide in methanol-chloroform (1:1, vol/vol) at a molar ratio of 4:1:5:5. The mixtures were dried under N2 gas and then vacuum dried for 30 min. The dried pellets were resuspended in PBS and sonicated 15 times in a cup horn (model XL2020; Heat Systems, Farmingdale, N.Y.) at maximum amplitude output (190 W) for 1 min each, with 5-min cooling periods on ice between sonications. The sonicated mixtures were centrifuged at 22,000 × g and 20°C for 20 min. The supernatants with sulfatide-containing liposomes were collected and used for bacterial agglutinations on glass slides for screening and semiquantitative analysis of bacterial binding. For quantitative analysis, bacteria from overnight cultures were harvested and resuspended in PBS to a density of 108 cells/ml. Equal volumes (50 μl) of resuspended cells and sulfatide-containing liposomes were mixed in microcentrifuge tubes and incubated 10 min at room temperature. Mixtures were centrifuged at 69 × g for 2 min, and the number of unbound cells in the supernatant was determined by performing viable-cell counts. For each mutant, the values were compared with the ones for the wild-type strain to calculate relative binding percentages. The values are given as averages and standard deviations of data from three separate experiments.

Solid-phase binding assays in microtiter plates.

Bacterial strains were prepared as described for the ELISA inhibition assays. Binding assays were performed as described previously (21). Briefly, polyvinyl chloride plates (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) were coated with sulfatide (1 μg per well) in chloroform-methanol (1:1 [vol/vol]). The wells were blocked with PBS–1% BSA for 1 h. Bacteria were serially diluted twofold. After 2 h of incubation at room temperature, bacterial binding was determined as described above for the ELISA protocol.

RESULTS

Effect of specific substitutions for FasG residues on fimbriation.

FasG is essential for fimbrial biogenesis, since fasG null mutants are nonfimbriated (2, 34, 35). To focus our studies on the specific binding domains of FasG, it was important to create non- or poorly adhesive mutants demonstrating normal levels of fimbrial expression. In view of the basic nature of FasG, its expected positive charges at pH 7.0, and the acidic nature of sulfatide, and by analogy with other systems (5, 14, 15), we reasoned that positively charged residues of the adhesin might be directly involved in binding to sulfatide through specific electrostatic interactions. Therefore, the fasG gene was subjected to positively charged-to-alanine-scanning mutagenesis. Alanine was chosen because of its small size and nonpolar nature, making it the amino acid residue expected to least affect the secondary to quaternary structure of the mutated protein. Moreover, since it is the surface of FasG which is expected to interact with its receptor, to improve our chance of obtaining mutants with the desired nonadhesive phenotype, the 20 FasG lysine (K) or arginine (R) residues predicted to be the most accessible (10) were replaced by alanine residues (Fig. 1A).

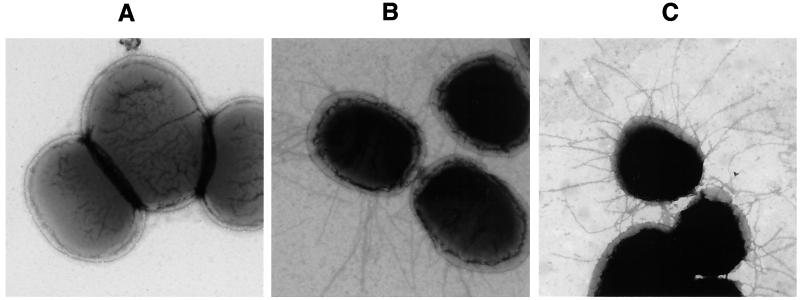

The 20 fasG mutants listed in Fig. 1B were tested for fimbriation by seroagglutination. Only 1 of the 20 mutants (substitution R27A) showed the same nonfimbriated phenotype (Fig. 1B) as the previously described fasG null mutants (34, 35). Two additional mutants (substitutions R286A and R368A) demonstrated reduced seroagglutination, indicating that several arginines dispersed along the primary structure of FasG are required for wild-type-level fimbriation. That 987P detection by seroagglutination effectively correlates with fimbrial expression, as described previously (35), was confirmed by electron microscopy. In contrast to seroagglutination-positive bacteria like the strains expressing the wild-type FasG or the mutated FasG(K117A) allelic protein, no fimbriae were detected on the bacterial surface of the seroagglutination-negative fasG R27A mutant (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Electron micrographs of wild-type or mutant strains. (A) Strain SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC-R27A expressing FasG(R27A); (B) strain SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC2 expressing wild-type FasG; (C) strain SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC-K117A expressing FasG(K117A). Magnification, ×23,000.

Identification of nonadhesive fasG mutants.

The sulfatide-binding property of the 20 fasG mutants was assessed by bacterial agglutination with sulfatide-containing liposomes. As shown in Fig. 1B, all three mutants with absent or reduced fimbriation, as detected by seroagglutination with anti-987P antibodies, demonstrated a concomitant decrease in their sulfatide-binding ability, supporting the previous data on the requirement of FasG for fimbriation—specifically, export and assembly of the major subunit FasA—and suggesting that FasG functions optimally as a sulfatide ligand only in the context of fimbriae (21). Among the 17 remaining fasG mutants (Fig. 1B), 4 demonstrated reduced binding to sulfatide-containing liposomes, and one additional mutant (K117A) was not agglutinated by the liposomes, despite the wild-type-level fimbriation of all 5 mutants. By dissociating structure-function phenotypes, these results indicate that FasG harbors different domains required for fimbriation and sulfatide binding and that at least one of the FasG residues which is not involved in fimbriation is essential for binding.

Adhesion-defective fasG mutants linked to decreased fimbriation or FasG display.

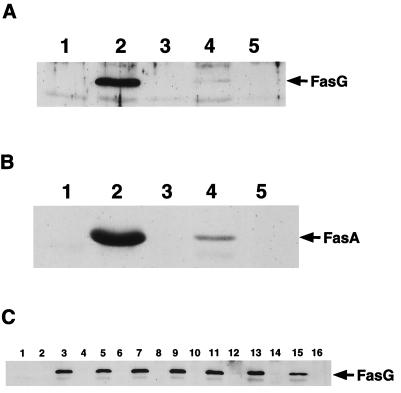

In addition to affecting the binding properties of FasG, mutations in fasG may alter fimbriation by various mechanisms. First, such mutations could interfere with correct assembly and export of the other structural subunits, FasA and FasF (2). Moreover, decreases in FasG stability or export and the occurrence of misfolding, affecting the display of major FasG surfaces of interactions for environmental molecules, could also interfere with receptor recognition. The following experiments were undertaken to eliminate such mutants in our specific search for sulfatide binding domains in FasG. The semiquantitative data for seroagglutination with anti-987P antibodies may not detect subtle changes in fimbrial expression on the bacterial surface. Therefore, to better assess subunit export, the amounts of heat-extractable FasG and FasA subunits of wild-type and nonbinding mutant strains were compared by Western blot analysis and enhanced chemiluminescence (Fig. 3). In addition to the expected three mutants (substitutions R27A, R286A, and R368A) demonstrating reduced fimbriation by seroagglutination (Fig. 1B), a fourth mutant (substitution R226A) exported consistently fewer FasA subunits (data not shown). Interestingly, these four mutants showed a concomitant decrease in FasG export, and this decrease was always of a larger magnitude than that for the major subunit FasA. Densitometric comparisons with the wild-type strain indicated that exported FasG and FasA were undetectable in the fasG R27A mutant and were reduced by approximately 96 and 60%, respectively, in the fasG R286A mutant, by 97.5 and 94%, respectively, in the fasG R368A mutant (Fig. 3A and 2B), and by 44% (Fig. 3C) and 14% (data not shown), respectively, in the fasG R226A mutant. To ensure that these results were not related to defects in fimbrial assembly resulting in subunit release into the medium, the media were analyzed for the presence of subunits. No subunits were detected in the culture media (data not shown), indicating that exported subunits were all cell associated.

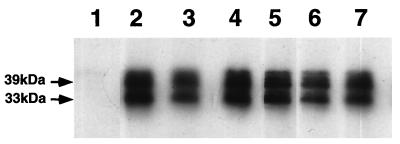

FIG. 3.

Western blots of fimbrial protein extracts, probed with anti-FasG (A and C) or anti-FasA (B) antibodies. (A and B) FasG and FasA export, respectively, by poorly or nonfimbriated fasG mutants. The same amount of boiled total protein was loaded in each well. Lanes 1, E. coli DMS741/pBKC1 (ΔfasG); lanes 2, DMS741/pBKC1/pBKC2, expressing wild-type FasG; lanes 3, DMS741/pBKC1/pBKC-R27A, expressing FasG(R27A); lanes 4, DMS741/pBKC1/pBKC-R286A, expressing FasG(R286A); lanes 5, DMS741/pBKC1/pBKC-R368A, expressing FasG(R368A). (C) FasG export by fimbriated fasG mutants. Boiled (odd lanes) and unboiled (even lanes) extracts containing the same amount of FasA protein were loaded in the wells. Lanes 1 and 2, E. coli DMS741/pBKC1(ΔfasG); lanes 3 and 4, DMS741/pBKC1/pBKC2, expressing wild-type FasG; lanes 5 and 6, DMS741/pBKC1/pBKC-K17A, expressing FasG(K17A); lanes 7 and 8, DMS741/pBKC1/pBKC-R116A, expressing FasG(R116A); lanes 9 and 10, DMS741/pBKC1/pBKC-K117A, expressing FasG(K117A); lanes 11 and 12, DMS741/pBKC1/pBKC-K118A, expressing FasG(K118A); lanes 13 and 14, DMS741/pBKC1/pBKC-R200A, expressing FasG(R200A); lanes 15 and 16, DMS741/pBKC1/pBKC-R226A, expressing FasG(R226A).

Moreover, since the heat extraction protocol used may not detect mutated subunits exhibiting tight cell association, the presence and accessibility of the mutated FasG proteins on the bacterial surface were further evaluated by seroagglutination (Fig. 1B), using a conformation-specific anti-FasG polyclonal antibody (2). In contrast to the wild-type strain, three of the mutants with reduced levels of heat-extractable subunits could not be agglutinated by the anti-FasG antibodies. Although the fasG R226A mutant expressed only slightly fewer fimbriae than the wild-type strain, as detected only by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3C and Fig. 1B), the 44%-reduced number of exported FasG molecules (Fig. 3C) was barely detectable by seroagglutination with the conformation-specific anti-FasG antibodies. Since these polyclonal antibodies do not recognize denatured FasG (2), the data suggest that the FasG molecules on the surface of this mutant are either inaccessible or sufficiently misfolded to have lost most of their major conformational epitopes. Taken together, the reduced sulfatide binding levels of the four mutants which do not react or react only poorly with the conformation-specific anti-FasG antibody can be attributed to a diminution of the display of FasG, or of correctly folded FasG, on the bacterial surface. These mutants were excluded from further studies focusing on the adhesive characteristics of FasG.

Adhesion-defective fasG mutants with conserved fimbriation and FasG display.

The amounts of FasA and FasG proteins exported by the five adhesion-defective mutants shown by seroagglutination to produce wild-type levels of fimbriae, as well as correctly folded and accessible FasG molecules (Fig. 1B), were evaluated by Western blot analysis and densitometric analysis as described above. All five mutants were shown to export amounts of FasA (95 to 113%) (data not shown) and FasG (96 to 116%) (Fig. 3C) proteins similar to those exported by the wild-type strain (set at 100%). Moreover, isolated fimbriae of these mutants behaved like the ones of the wild-type strain in showing dissociation into major and minor subunits after heating at 100°C but not after SDS treatment at room temperature. This indicated that the different mutated allelic FasG proteins are associated with the fimbrial structure (22). A conformation-specific MAb (E11) recognizing the quaternary structure of 987P was used to confirm correct subunit assembly and fimbrial integrity in each of these mutants. None of the described substitutions in the five mutants induced discernible conformational changes in 987P, as indicated by ELISA inhibition assays (data not shown). Moreover, electron microscopic visualization of the fimbriae on the wild-type bacteria and the fasG K117A mutant showed that their structures, lengths, and average numbers per bacterium are not significantly different (Fig. 2B and C).

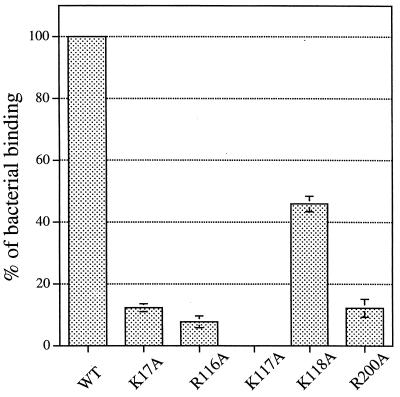

Characterization of the poorly adhesive and nonadhesive fasG fimbriated mutants.

Fimbrial biogenesis, FasG export, and folding of five fasG mutants with reduced binding to sulfatide-containing liposomes could not be differentiated from those of the wild-type strain. To better compare the binding properties of these mutants, numbers of liposome-associated bacteria were counted after differential centrifugation (Fig. 4). Confirming the original screening result, only one fasG mutant (K117A) did not bind to sulfatide at all. The other mutants retained different residual levels of sulfatide binding (K118A > R200A > K17A > R116A).

FIG. 4.

Binding of fasG mutants to sulfatide-containing liposomes. Binding by mutants was related to wild-type strain binding (100%) after determination by the liquid-phase binding assay described in Materials and Methods. Error bars represent standard deviations of data from three separate experiments. WT, strain SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC2, expressing wild-type FasG; K17A, SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC-K17A, expressing FasG(K17A); R116A, SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC-R116A, expressing FasG(R116A); K117A, SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC-K117A, expressing FasG(K117A); K118A, SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC-K118A, expressing FasG(K118A); R200A, SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC-R200A, expressing FasG(R200A).

That accessibility to the receptor differs depending on whether sulfatide is embedded in liposomes or dried on a solid phase was shown by evaluating the adhesion of the mutants to sulfatide-coated microtiter wells (data not shown). Although binding was less affected for the five mutants, the three mutants recognizing the least sulfatide in liposomes also exhibited the lowest level of binding to immobilized sulfatide. Since sulfatide contains only one carbohydrate residue, immobilization is expected to have drastic effects on its interaction capacity, rendering our results with sulfatide-embedded liposomes physiologically more relevant. Such liposomes better mimic receptor presentation by cellular brush border membranes. Residue K117 has as neighbors several basic residues predicted to form together the most surface-exposed domain of FasG (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, adhesion is abolished only when K117 is mutated, indicating that only this residue is critical for receptor recognition. It is tempting to suggest that K117 plays a central role in the steric fit of the FasG-sulfatide interaction by forming a salt bridge with the sulfate group of sulfatide. Moreover, FasG-sulfatide binding may be stabilized by additional electrostatic interactions, since four other substitutions of specific basic residues in FasG, two flanking K117, diminish binding.

In addition to binding to the sulfatide receptor, FasG also interacts with glycoprotein receptors on piglet brush borders. To determine whether FasG utilizes the same recognition sites for these two types of receptors, the five mutants whose binding to sulfatide was affected (K17A, R116A, K117A, K118A, and R200A) were also analyzed for glycoprotein binding by a ligand blotting assay. Most interestingly, all five of the mutants retained their ability to adhere to glycoprotein receptors (Fig. 5), indicating that FasG utilizes different mechanisms, domains, and/or residues for its interactions with its glycolipid and glycoprotein receptors. Moreover, that a functional property of 987P fimbriae distinct from sulfatide binding is unaffected in these mutants further strengthens the argument that the overall conformation of the mutated FasG proteins remains unaffected. However, it remains possible that the described mutations interfere indirectly with sulfatide binding by altering neighboring residues required for the correct presentation and orientation of the residues interacting with sulfatide.

FIG. 5.

Ligand blotting assays. BBV proteins were separated by SDS–12% PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose. After being blocked with TBS–3% BSA, each blotted strip was incubated with fimbriae. Bound fimbriae were visualized by chemiluminescence, using a MAb specific for the quaternary structure of 987P. Lane 1, E. coli SE5000/pBKC1(ΔfasG); lane 2, SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC2, expressing wild-type FasG; lane 3, SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC-K17A, expressing FasG(K17A); lane 4, SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC-R116A, expressing FasG(R116A); lane 5, SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC-K117A, expressing FasG(K117A); lane 6, SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC-K118A, expressing FasG(K118A); lane 7, SE5000/pBKC1/pBKC-R200A, expressing FasG(R200A).

DISCUSSION

FasG is thought to play an essential role in the diarrheal disease induced by 987P-fimbriated ETEC strains since it mediates the adherence of such strains to both glycoprotein receptors and sulfatide molecules located on the brush borders of intestinal receptors (7, 8, 21, 22). Among the three types of 987P structural proteins, FasG is the first type of subunit exported (2), and fasG null mutants do not produce 987P fimbriae (35). Therefore, in contrast to the type 1 and Pap fimbrial systems (24, 26), the 987P adhesin is absolutely required to initiate fimbrial biogenesis. In this study, we determined whether site-directed mutagenesis could be used to dissociate the adhesive properties of FasG from its role as an initiator of fimbriation. Because of the structure of the sulfatide receptor, it was hypothesized that specific basic residues of the FasG adhesin might interact with the acidic carbohydrate moiety of sulfatide. This hypothesis was tested by screening for fimbriated nonadhesive mutants after targeting basic residues of FasG by alanine-scanning mutagenesis. In addition to identifying four fasG mutants (K17A, R116A, K118A, and R200A) demonstrating reduced interaction with sulfatide, one fimbriated fasG mutant (K117A) exporting normal amounts of fimbria-associated FasG proteins did not bind at all to membrane-embedded sulfatide. In contrast, these five mutants still bound to the glycoprotein receptors, strongly suggesting that the mechanisms by which FasG binds to its two types of receptors are different and that the corresponding mutations do not alter the overall conformation of FasG. Only one fasG mutant (R27A) was nonfimbriated, and some mutants (R286A and R368A) expressed fewer fimbriae. These residues may be important during fimbrial biogenesis for heteropolymerization of FasG with its periplasmic chaperone FasC (9), for its channeling through the outer membrane usher protein FasD (33), for its proper folding and incorporation into the fimbrial structure, and/or for its role as an initiator of fimbrial export and assembly (2).

The finding that the substitution of only one FasG residue (K117A) was sufficient to result in the complete loss of the sulfatide receptor binding phenotype, while the fimbrial display of the adhesin and the glycoprotein receptor binding property remained unaltered, was unexpected. The same result was recently obtained by genetically engineering wild-type strain 987 to express the mutated FasG(K117A) protein instead of nonmutated FasG (4), indicating that the observed properties of the corresponding mutant were not influenced by the use of a high-copy-number plasmid for FasG expression. Therefore, it is suggested that the side chain of K117 mediates a key interaction, possibly a salt bridge, with the sulfate group of sulfatide. Although a similar critical bond has been described in the crystal structure of polyomavirus complexed with the acidic sugar moiety of its receptor (38), additional studies will be required to test the role of K117 in the FasG-sulfatide interaction. With the central location of K117 in a stretch of three basic residues, each of them modulating sulfatide binding, multiple hydrogen bonds could also be envisioned. The position of K117 could be critical to correctly align various electrostatic interactions in such a sulfatide binding pocket. Several studies have described and suggested how small clusters of basic residues mediate protein binding to acidic molecules (1, 12, 16, 41), including K99 and S fimbria binding to sialic acid-containing host receptors (18, 27). The elucidation of the crystal structure of heparin-derived oligosaccharide complexed to fibroblast growth factor (11) may best demonstrate how arrays of polar contacts, both ion pairs and hydrogen bonds, can mediate receptor-ligand interactions.

It was previously shown that assembled fimbriae, but neither pre- nor postassembly-dissociated fimbrial FasG subunits, were able to inhibit 987P-mediated bacterial binding to piglet sulfatide (21). Stable binding of microbial agents to host receptors typically requires the additive or cooperative interactions of several subunits (20). Therefore, it is likely that a low affinity of one FasG molecule for sulfatide can be compensated by the multivalent nature of both fimbrial and bacterial binding, since each fimbrial thread carries 5 to 20 FasG subunits (21, 22) and bacteria express hundreds of peritrichous fimbriae. Potentiation of the resulting interactions is best documented visually with bacterial agglutination by sulfatide-containing liposomes. The accessibility of glycolipid receptors to ligands is more restricted when the receptors are membrane associated than when they are coated onto a solid phase. It is thought that membranes modulate the accessibility of the receptor by determining the orientation of the receptor and by constraining the spacial fit between the receptor and the ligand, as supported by studies with various glycolipid receptors (20, 39). Such effects are expected to be very pronounced with sulfatide, since its receptor domain can only involve one carbohydrate. Therefore, it was not surprising that the liposome binding assay was more sensitive than the solid-phase binding assay. Results obtained with the former method are recognized as more relevant, since membrane-dependent receptor presentation better mimics the biological situation (20).

Although we have shown that FasG residue K117 is required for the FasG-sulfatide interaction, further investigations are needed to confirm that K117 directly participates in receptor binding via electrostatic interactions. For example, it remains possible that this and other described mutations affect optimal presentation of the binding surfaces interacting with sulfatide by altering indirectly the conformation of these surfaces. Finally, additional studies are required to dissect the glycoprotein receptor binding property of FasG. This information will be important to determine the biological relevance of each set of interactions by in vivo experimentation, a major goal being to design model therapeutic and prophylactic approaches, based on ligand or receptor analogues (28), for interfering with pathogen colonization.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. S. Khan for having developed the liposome protocols in our laboratory and W. C. Lawrence for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by U.S. Department of Agriculture grant 37204-1986.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ben-Tal N, Honig B, Peitzsch R M, Denisov G, McLaughlin S. Binding of small basic peptides to membranes containing acidic lipids: theoretical models and experimental results. Biophys J. 1996;71:561–575. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79280-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao J, Khan A S, Bayer M E, Schifferli D M. Ordered translocation of 987P fimbrial subunits through the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3704–3713. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.13.3704-3713.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casey T A, Schneider R A, Dean-Nystrom E A. Identification of plasmid and chromosomal copies of 987P pilus genes in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli 987. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2249–2252. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2249-2252.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi, B. K., and D. M. Schifferli. 1999. Unpublished data.

- 5.Cunningham B C, Wells J A. High-resolution epitope mapping of hGH-receptor interactions by alanine-scanning mutagenesis. Science. 1989;244:1081–1085. doi: 10.1126/science.2471267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean E A. Comparison of receptors for 987P pili of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in the small intestines of neonatal and older pigs. Infect Immun. 1990;58:4030–4035. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.4030-4035.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean E A, Whipp S C, Moon H W. Age-specific colonization of porcine intestinal epithelium by 987P-piliated enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1989;57:82–87. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.82-87.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean-Nystrom E A, Samuel J E. Age-related resistance to 987P fimbria-mediated colonization correlates with specific glycolipid receptors in intestinal mucus in swine. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4789–4794. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4789-4794.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards R A, Cao J, Schifferli D M. Identification of major and minor chaperone proteins involved in the export of 987P fimbriae. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3426–3433. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3426-3433.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emini E A, Hughes J V, Perlow D S, Boger J. Induction of hepatitis A virus-neutralizing antibody by a virus-specific synthetic peptide. J Virol. 1985;55:836–839. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.3.836-839.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faham S, Hileman R E, Fromm J R, Linhardt R J, Rees D C. Heparin structure and interactions with basic fibroblast growth factor. Science. 1996;271:1116–1120. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flynn S J, Ryan P. The receptor-binding domain of pseudorabies virus glycoprotein gC is composed of multiple discrete units that are functionally redundant. J Virol. 1996;70:1355–1364. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1355-1364.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibbs C S, Zoller M J. Identification of electrostatic interactions that determine the phosphorylation site specificity of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5329–5334. doi: 10.1021/bi00236a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibbs C S, Zoller M J. Identification of functional residues in proteins by charged-to-alanine scanning mutagenesis. Methods Companion Methods Enzymol. 1991;3:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hacker J, Morschhäuser J. S and F1C fimbriae. In: Klemm P, editor. Fimbriae. Adhesion, genetics, biogenesis, and vaccines. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1994. pp. 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holt G D, Pangburn M K, Ginsburg V. Properdin binds to sulfatide [Gal(3-SO4)β1-1Cer] and has a sequence homology with other proteins that bind sulfated glycoconjugates. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2852–2855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isaacson R E, Fusco P C, Brinton C C, Moon H W. In vitro adhesion of Escherichia coli to porcine small intestinal epithelial cells: pili as adhesive factors. Infect Immun. 1978;21:392–397. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.2.392-397.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs A A C, Simons B H, de Graaf F K. The role of lysine-132 and arginine-136 in the receptor-binding domain of the K99 fibrillar subunit. EMBO J. 1987;6:1805–1808. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones G W, Rutter J M. Role of the K88 antigen in the pathogenesis of neonatal diarrhea caused by Escherichia coli in piglets. Infect Immun. 1972;6:918–927. doi: 10.1128/iai.6.6.918-927.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karlsson K-A, Ångström J, Bergström J, Lanne B. Microbial interaction with animal cell surface carbohydrates. APMIS. 1992;100:71–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan A S, Johnston N C, Goldfine H, Schifferli D M. Porcine 987P glycolipid receptors on intestinal brush borders and their cognate bacterial ligands. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3688–3693. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3688-3693.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan A S, Schifferli D M. A minor 987P protein different from the structural fimbrial subunit is the adhesin. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4233–4243. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4233-4243.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lund B, Lindberg F, Marklund B-I, Normark S. Tip proteins of pili associated with pyelonephritis: new candidates for vaccine development. Vaccine. 1988;6:110–112. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(88)80010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markwell M A, Haas S M, Bieber L L, Tolbert N E. A modification of the Lowry procedure to simplify protein determination in membrane and lipoprotein samples. Anal Biochem. 1978;87:206–210. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90586-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maurer L, Orendorff P E. A new locus, pilE, required for the binding of type 1 piliated Escherichia coli to erythrocytes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1985;30:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morschhäuser J, Hoschützky H, Jann K, Hacker J. Functional analysis of the sialic acid-binding adhesin SfaS of pathogenic Escherichia coli by site-specific mutagenesis. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2133–2138. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2133-2138.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mouricout M, Petit J M, Carias J R, Julien R. Glycoprotein glycans that inhibit adhesion of Escherichia coli mediated by K99 fimbriae: treatment of experimental colibacillosis. Infect Immun. 1990;58:98–106. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.1.98-106.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagy B, Moon H W, Isaacson R E. Colonization of porcine intestine by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: selection of piliated forms in vivo, adhesion of piliated forms to epithelial cells in vitro, and incidence of a pilus antigen among porcine enteropathogenic E. coli. Infect Immun. 1977;16:344–352. doi: 10.1128/iai.16.1.344-352.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutter J M, Jones G W. Protection against enteric disease caused by Escherichia coli—a model for vaccination with a virulence determinant? Nature. 1973;242:531–532. doi: 10.1038/242531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satterwhite T K, Evans D G, DuPont H L, Evans D J., Jr Role of Escherichia coli colonization factor antigen in acute diarrhoea. Lancet. 1978;ii:181–184. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)91921-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schifferli D M, Abraham S N, Beachey E H. Use of monoclonal antibodies to probe subunit- and polymer-specific epitopes of 987P fimbriae of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1987;55:923–930. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.4.923-930.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schifferli D M, Alrutz M A. Permissive linker insertion sites in the outer membrane protein of 987P fimbriae of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1099–1110. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.4.1099-1110.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schifferli D M, Beachey E H, Taylor R K. 987P fimbrial gene identification and protein characterization by T7 RNA polymerase induced transcription and TnphoA mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:61–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schifferli D M, Beachey E H, Taylor R K. Genetic analysis of 987P adhesion and fimbriation of Escherichia coli: the fas genes link both phenotypes. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1230–1240. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.3.1230-1240.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silhavy T J, Berman M L, Enquist L W. Experiments with gene fusion. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith H W, Linggood M L. Observations on the pathogenic properties of the K88, Hly and Ent plasmids of Escherichia coli with particular reference to porcine diarrhoea. J Med Microbiol. 1971;4:467–485. doi: 10.1099/00222615-4-4-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stehle T, Yan Y, Benjamin T L, Harrison S C. Structure of murine polyomavirus complexed with an oligosaccharide receptor fragment. Nature. 1994;369:160–163. doi: 10.1038/369160a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strömberg N, Marklund B-I, Lund B, Ilver D, Hamers A, Gaastra W, Karlsson K-A, Normark S. Host-specificity of uropathogenic Escherichia coli depends on differences in binding specificity to Gal1-4Gal containing isoreceptors. EMBO J. 1990;9:2001–2010. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Towbin H, Gordon J. Immunoblotting and dot immunobinding—current status and outlook. J Immunol Methods. 1984;72:313–340. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu D, Lin S L, Nussinov R. Protein binding versus protein folding: the role of hydrophilic bridges in protein associations. J Mol Biol. 1997;265:68–84. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]