Abstract

Escherichia coli is the most common gram-negative bacterium that causes meningitis during the neonatal period. We have previously shown that the entry of circulating E. coli organisms into the central nervous system is due to their ability to invade the blood-brain barrier, which is composed of a layer of brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMEC). In this report, we show by transmission electron microscopy that E. coli transmigrates through BMEC in an enclosed vacuole without intracellular multiplication. The microfilament-disrupting agents cytochalasin D and latrunculin A completely blocked E. coli invasion of BMEC. Cells treated with the microtubule inhibitors nocodazole, colchicine, vincristin, and vinblastine and the microtubule-stabilizing agent taxol also exhibited 50 to 60% inhibition of E. coli invasion. Confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy showed F-actin condensation associated with the invasive E. coli but no alterations in microtubule distribution. These results suggest that E. coli uses a microfilament-dependent phagocytosis-like endocytic mechanism for invasion of BMEC. Previously we showed that OmpA expression significantly enhances the E. coli invasion of BMEC. We therefore examined whether OmpA expression is related to the recruitment of F-actin. OmpA+ E. coli induced the accumulation of actin in BMEC to a level similar to that induced by the parental strain, whereas OmpA− E. coli did not. Despite the presence of OmpA, a noninvasive E. coli isolate, however, did not show F-actin condensation. OmpA+-E. coli-associated condensation of F-actin was blocked by synthetic peptides corresponding to the N-terminal extracellular domains of OmpA as well as BMEC receptor analogues for OmpA, chitooligomers (GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc oligomers). These findings suggest that OmpA interaction is critical for the expression or modulation of other bacterial proteins that will subsequently cause actin accumulation for the uptake of bacteria.

It is becoming increasingly evident that microbial entry into mammalian cells is a result of the interaction of specific bacterial determinants with host cell receptors. These interactions often dictate the tissue tropism of bacteria in several diseases. Escherichia coli is the most common gram-negative bacterium that causes meningitis in neonates. Although most cases of E. coli meningitis occur via hematogenous spread, it is not clear how the circulating E. coli cells become neurotropic. The blood-brain barrier, which is constituted by a single layer of specialized brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMEC), is the major target for neurotropic E. coli for gaining access into the central nervous system (CNS) for the development of disease. The interaction of E. coli surface structures with their corresponding BMEC ligands is a prerequisite for the invasion of BMEC. We have shown that several E. coli-BMEC interactions contribute to successful crossing of the blood-brain barrier by E. coli. The expression of S-fimbriae, the filamentous protein appendages that bind to terminal NeuAcα2,3Gal sequences present on glycoproteins, enhances the binding of E. coli to BMEC, which is mediated by a lectin-like activity of the SfaS adhesin both in vitro (22) and in a rat model (3). Furthermore, we have identified and characterized a novel 65-kDa S-fimbria binding sialoglycoprotein on BMEC (19). Binding to BMEC via S-fimbriae was, however, not accompanied by invasion into BMEC, indicating that S-fimbriae may be the prime attachment-promoting factor for E. coli.

In our efforts to identify nonfimbriated structures that contribute to E. coli invasion of BMEC, we showed that E. coli strains expressing OmpA exhibit significant invasive capability compared with strains lacking OmpA (17). The OmpA-mediated E. coli invasion occurs via GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc epitopes of surface glycoproteins on BMEC (18). Receptor analogues, the chitooligomers (GlcNAc1,4-GlcNAc oligomers), blocked the E. coli invasion of BMEC both in vitro and in a newborn rat model of hematogenous meningitis, suggesting that these epitopes are indeed involved in E. coli entry into the CNS. Since OmpA is highly conserved on several gram-negative bacteria, it is possible that other bacterial proteins also play a role in the invasion. Subsequently, we identified an 8-kDa E. coli protein, Ibe10, and its BMEC receptor necessary for E. coli invasion (6, 21). In addition, Ibe10 is present only in clinical E. coli isolates and not in laboratory strains or noninvasive strains (6). Absence of either OmpA or Ibe10 significantly hampers the ability of E. coli to invade BMEC, suggesting that both proteins are necessary for efficient bacterial invasion of BMEC.

Of interest is the finding that E. coli binding and invasion are specific to BMEC but not to systemic endothelial cells. This suggests that the expression of receptor molecules for E. coli determinants (e.g., S-fimbriae, OmpA, and Ibe10) allows BMEC to be more interactive with E. coli, resulting in E. coli traversal of the blood-brain barrier. In agreement with this hypothesis, our studies showed that the presence of a 65-kDa S-fimbria binding protein is unique to BMEC isolated from different species (19). Thus, E. coli recognizes a unique environment on BMEC for entering the CNS; however, the exact mechanism(s) of bacterial entry into BMEC is not known.

In this study, electron microscopy was used to reveal the ultrastructural characteristics of E. coli interaction with BMEC. Next, the role of BMEC structures involved in E. coli entry was examined by using selective eukaryotic inhibitors and fluorescence microscopy. In addition, the role of OmpA in the entry of E. coli was examined by using genetically defined OmpA+ and OmpA− E. coli strains, as well as by using synthetic peptides that represent the functional domains of OmpA and BMEC receptor analogues for OmpA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and chemicals.

The strains used in this study, E44, E105, and E111, are derivatives of the E. coli K1 strain RS218 (serotype O18:K1:H7) isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid of a neonate with meningitis as described previously (17). Strain E44 is a spontaneous rifampin-resistant mutant, and E91 (OmpA−) is a mutant lacking the ompA gene. E105 is E91 containing the pUC9 plasmid in which the ompA gene was subcloned, resulting in pRD87, and expresses normal levels of OmpA by Western blot analysis with anti-OmpA antibody (17). E111 is E91 containing the pUC9 empty vector. Other phenotypic characteristics of strains E44, E105, and E111 were identical, including expression of hemolysin and aerobactin, as well as lipopolysaccharide, S-fimbriae, type 1 fimbriae, and the K1 capsule, as described previously (17). E. coli E412, a noninvasive K1 blood isolate, was used as a negative control (16). Bacteria were grown in brain heart infusion broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) with appropriate antibiotics. The following concentrations of antibiotics were used, unless otherwise stated: 100 μg of rifampin per ml for E44 and 100 μg of rifampin per ml and 100 μg of ampicillin per ml for E105 and E111. Lectins and chitin hydrolysate were obtained from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, Calif.). Monoclonal antibodies to tubulin, clathrin, and other reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.) unless otherwise specified. Preparation and the concentrations of synthetic peptides used in this study were described previously (17).

Invasion assay.

Bovine BMEC were isolated as described previously (22) and seeded into 24-well plates (Corning) in medium containing M199–Ham F-12 (1:1), 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate with antibiotics, and the mixture was cultured to confluence. Prior to the experiments the medium was aspirated and invasion assays were carried out as described previously (17, 18). Briefly, bacterial strains were grown in brain heart infusion broth, containing appropriate antibiotics, overnight at 37°C. The bacteria were washed three times with saline and resuspended in experimental medium (M199–Ham F12 [1:1], l-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, and 5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum with no antibiotics). The optical density (620 nm) of E. coli in experimental medium was adjusted to 0.25 to 0.3 (108 bacteria/ml), and approximately 107 bacteria were added to the confluent BMEC monolayer. The plates were incubated for 1.5 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 without shaking. Infection was stopped by rinsing the cells four times with RPMI 1640 medium, and the cells were further incubated with experimental medium containing 100 μg of gentamicin per ml at 37°C for 1 h to kill extracellular bacteria. The monolayers were then washed four more times and lysed with 0.5% Triton X-100. The number of released intracellular bacteria was enumerated by plating on sheep blood agar. The actual inoculum size was determined by colony plate count for every experiment. Each assay was conducted in triplicate and at least three times separately. Bacterial viability was not affected by 0.5% Triton X-100 treatment. The MIC of gentamicin for all strains used was 1 μg/ml. Cell viability was routinely verified by the addition of trypan blue.

Invasion assays in the presence of eukaryotic inhibitors.

To examine the role of cytoskeletal architecture in E. coli invasion, several eukaryotic inhibitors were used. Stock solutions of cytochalasin D and latrunculin A were made in dimethyl sulfoxide and diluted in experimental medium to 0.5 and 1.0 μM as working dilutions. These inhibitors were incubated with the BMEC monolayers for 30 min at 37°C before addition of bacteria. Inhibitors of microtubule polymerization, namely, nocodazole (20 μM) and colchicine (5 μM), were preincubated with the BMEC monolayers for 1 h at 4°C and then at 37°C for 30 min prior to infection. Other microtubule polymerization inhibitors, namely, vinblastine (10 μM) vincristine (5 μM), and the microtubule-stabilizing agent taxol (20 μM) were incubated with the monolayers for 1 h at 37°C before addition of bacteria. All inhibitors were present throughout the invasion experiment until the medium was replaced with experimental medium containing gentamicin. The total numbers of cell-associated bacteria, both extracellular and intracellular, were calculated in duplicate experiments in the presence of inhibitors but without the gentamicin incubation step. The effect of these inhibitors on both bacteria and BMEC was examined by the colony plate count and trypan blue methods, respectively.

Immunofluorescence.

In order to identify the cellular elements after infection with E. coli, the BMEC were grown in eight-well chamber slides and infected with E. coli for different times. After incubation, the cells were washed with RPMI 1640 and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for at least 15 min at room temperature. For staining cellular components, the cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS–1% normal goat serum (PBS-NGS) for 20 min and washed three times (5 min each) with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20. For staining F-actin, tetramethyl rhodamine isocyanate (TRITC)-labeled phalloidin (Molecular Probes) was used at a concentration of 0.5 to 1 μg/ml in PBS-NGS and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. For staining microtubules, the cells were fixed with microtubule stabilization buffer {100 mM PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid), 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA (pH 6.8)} for 5 min and then with paraformaldehyde buffer for at least 15 min (2). Anti-α-tubulin antibody (diluted 1:1,000) was added to permeabilized BMEC monolayers in PBS-NGS, and the monolayers were incubated for 30 min in a cell culture incubator, washed five times with RPMI 1640, and incubated again with TRITC-labeled anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (diluted 1:1,000) in PBS-NGS. After removal of primary reagents, the monolayers were washed four times for 10 min with PBS-Tween 20, the chambers were removed, and the slides were mounted in 50% glycerol–PBS. Cells were viewed with a Zeiss Axioscope laser scanning confocal microscope.

TEM.

The invasion of E. coli into BMEC was allowed to occur as described above. At different time points, BMEC monolayers were washed four times with prewarmed M199 and fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). The cells were rinsed, postfixed with 2% OsO4 for 1 h, and then rinsed again, dehydrated through graded ethanol solutions, and treated with a mixture of ethanol and propylene oxide. The resulting cell pellets or monolayers were embedded in Epon. Ultrathin sections were cut at right angles to the culture cell layer, mounted on collodion one-hole grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined with a Phillips CM 12 transmission electron microscope. In some experiments, the cells were scraped from the dishes, pelleted down, washed four times with PBS, and processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

RESULTS

TEM examination of E. coli invasion of BMEC.

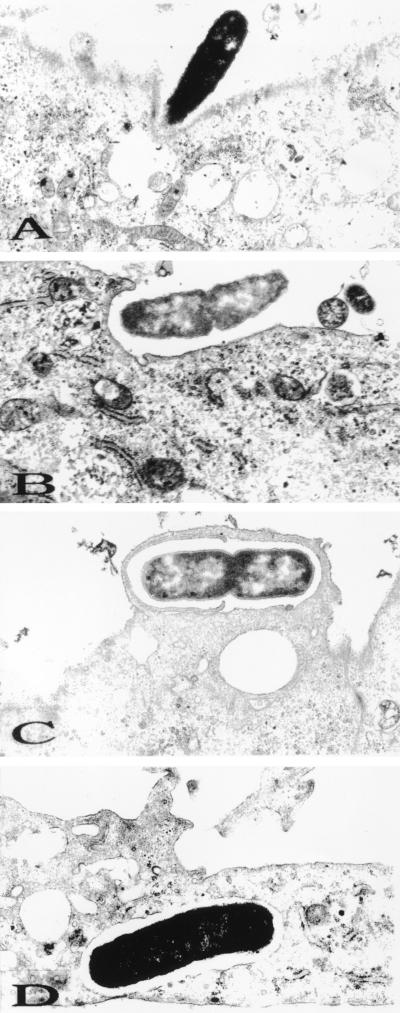

To visualize the interaction of E. coli with BMEC, TEM was performed with BMEC monolayers infected with strain E44 for different periods. Due to low invasion frequency, the data presented here were obtained from both BMEC monolayers and BMEC pellets processed for TEM. Ultrastructural experiments revealed that during the first ten minutes of infection, many bacteria were found on the top of the BMEC monolayer; however, very few bacteria attached to the BMEC surfaces. At this time, some of the bacteria were found to be present in BMEC cell invaginations (Fig. 1A). The bacterium appeared to closely contact the cell membrane and elicit its own uptake by 20 to 30 min postinfection (Fig. 1B and C). E. coli organisms were found intracellularly in membrane-bound vacuoles after 30 min of incubation with bacteria (Fig. 1D). Although a dividing bacterium started to enter the BMEC (Fig. 1B and C), only one bacterium was ever seen in the vacuole. Infrequently, two individually enclosed bacteria were observed per cell. In addition, no free bacteria were observed in the cytoplasm even at 2 h postinfection. At 45 min postinfection several bacteria were found at the basolateral side of the BMEC monolayer. Transwell experiments using BMEC monolayers also revealed that E44 traversed to the bottom chamber by 45 min following bacterial inoculation of the upper chamber (23). These results suggest that E. coli crosses the BMEC monolayers transcellularly within a short period and with no or very limited intracellular multiplication.

FIG. 1.

Transmission electron micrographs of BMEC infected with the E. coli K1 strain E44. (A and B) Cells at the 15-min time point; (C and D) cells at the 30-min time point. Magnifications, ×12,750 (A) and ×16,150 (B to D).

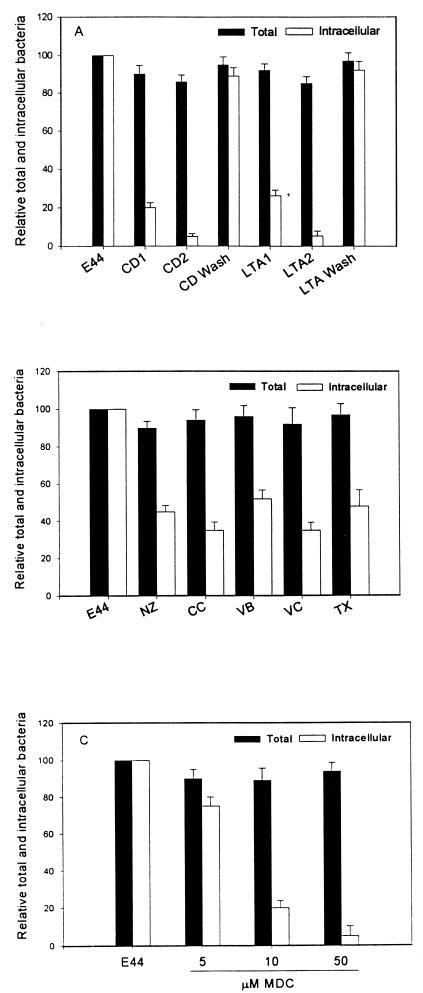

Role of actin filaments in E. coli invasion of BMEC.

TEM showed that an endocytosis-like mechanism may be involved in E. coli invasion of BMEC. Thus, the role of the actin-based cytoskeleton in the internalization of E. coli was evaluated by pretreating the BMEC with different concentrations of two actin-filament-disrupting agents, cytochalasin D and latranculin A. Cytochalasin D caps the growing ends of actin filaments and causes depolymerization of actin filaments, predominantly stress fibers (10). On the other hand, latrunculin A, unlike cytochalasins, destabilizes actin filaments by sequestering actin monomers and shifting the equilibrium to the disassembled state (10). These drugs changed the morphology of BMEC, causing cell rounding and retraction but no cell detachment. As shown in Fig. 2A, both drugs abolished the invasion of E. coli by >90% in a dose-dependent manner although the total number of bacteria associated with BMEC was not significantly affected. The effects of cytochalasin and latrunculin were reversed by washing the monolayers before the addition of bacteria, suggesting that the effects of these drugs are specific to BMEC microfilaments.

FIG. 2.

Effect of eukaryotic inhibitors on E. coli invasion of BMEC. (A) The BMEC monolayers were preincubated with two different concentrations (0.5 and 1 μM) of either cytochalasin D (CD) or latrunculin A (LTA) as described in Materials and Methods. In some experiments the drugs were removed and the monolayers were washed three times before the addition of the bacteria (CD wash or LTA wash). The BMEC monolayers were incubated with drugs affecting microtubule polymerization, namely, nocodazole (NZ), colchicine (CC), vinblastine (VB), vincristine (VC), and taxol (TX) (B) or in separate experiments with different concentrations of MDC (C) as described in Materials and Methods. Values are means ± standard deviations of results from at least three experiments carried out in triplicate and are expressed as percentages of the value for the no-inhibitor control (E44). P < 0.001 for CD, LTA, or MDC (10 and 50 μM), and P < 0.01 for results with microtubule inhibitors versus results with the no-inhibitor control by unpaired two-tailed t test.

Accumulation of F-actin was observed with E. coli invasion of BMEC.

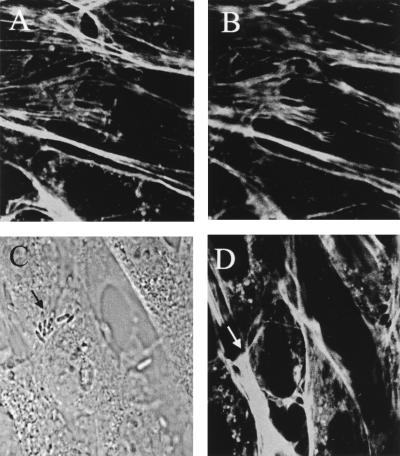

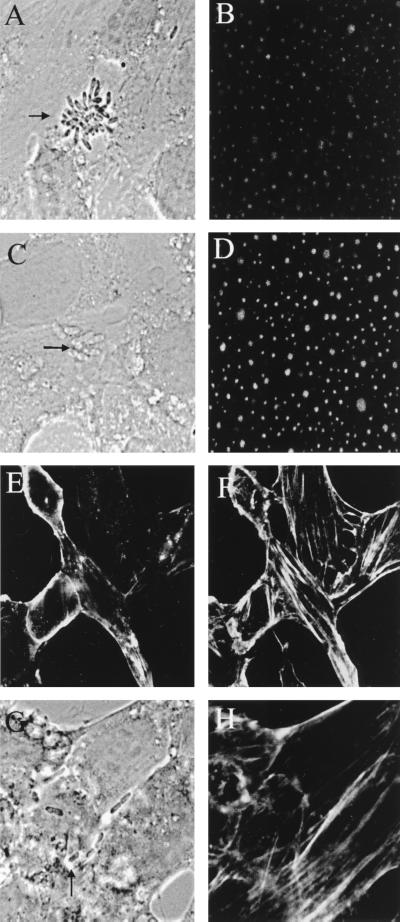

As described above, the microfilament-disrupting agents blocked E. coli invasion of BMEC significantly. Therefore, we examined whether E. coli induces cytoskeletal rearrangement in BMEC by staining the microfilaments of infected BMEC monolayers with rhodamine-phalloidin and analyzing the results by confocal microscopy. Uninfected BMEC showed bright staining of cortical actin filaments at the apical surface, whereas the basal portion revealed more actin filaments with a dense accumulation of actin (similar to results shown in Fig. 8A and B). At 10 min postinfection, monolayers showed bacteria attached in groups in several places on a particular subpopulation of BMEC, although individual bacteria were also seen (Fig. 3A). Actin condensation within the host cell occurred directly beneath the groups of adherent bacteria (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, not all the bacteria attached to BMEC can induce actin condensation. The actin accumulation appeared to be associated with one or two bacteria as a focal point. This phenomenon probably occurs near the front end of the entering bacteria, unlike footprinting, which can occur directly beneath the bacterium observed, as with Neisseria gonorrhoeae (4). A single bacterium with actin condensation in front of the invasive end is shown in Fig. 3C and D. In contrast, the noninvasive control strain E. coli E412 showed no such signs of induction of actin aggregation (Fig. 3E and F). At 45 min postinfection the intensity of actin condensation associated with E. coli was decreased considerably, indicating that once intracellular, bacteria may not be associated with polymerized actin (data not shown).

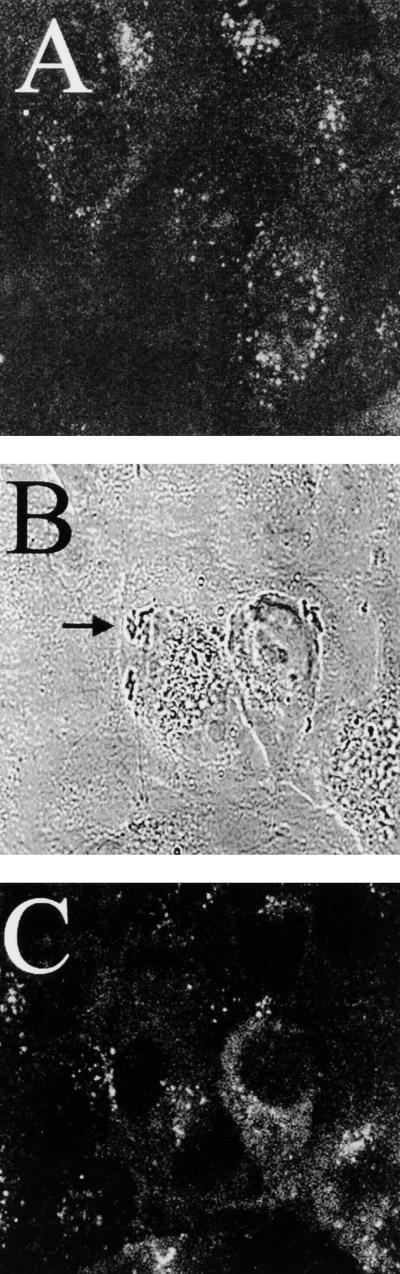

FIG. 8.

Effect of MDC on E. coli-induced condensation of actin. BMEC monolayers were pretreated with MDC for 1 h before the bacteria were added as described in Materials and Methods. Uninfected (A and B) and infected (D and F) cells were stained with TRITC-phalloidin to visualize actin. Arrows indicate the bacteria and corresponding actin accumulation.

FIG. 3.

Fluorescence micrographs showing the accumulation of F-actin. The BMEC monolayers were infected with either E44 (A to D) or E412 (E and F). The bacteria were visualized by transmitted light optics (A, C, and E). F-actin was stained with TRITC-phalloidin (B, D, and F). Arrows show the positions of the bacteria and the corresponding actin staining.

Cytochalasin D disrupts E. coli-induced actin condensation.

To further substantiate the role of microfilaments in E. coli invasion, we examined the inhibitory effect of cytochalasin D or latrunculin A on E. coli-induced condensation of actin. Uninfected BMEC treated with cytochalasin D showed complete dissolution of cortical filaments and the formation of a few actin aggregates at the apical membrane, whereas they showed the formation of heavy actin aggregates at the basolateral side (Fig. 4A and B). E. coli-infected BMEC showed no condensation of actin associated with bacteria, suggesting that cytochalasin D-sensitive actin recruitment may be necessary for E. coli entry into BMEC (Fig. 4C and D). Latrunculin A also showed similar inhibition of actin condensation (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Effect of cytochalasin D on BMEC infected with E. coli E44. BMEC monolayers were incubated with cytochalasin D (0.5 μM) for 15 min before the addition of the bacteria. The layers were fixed and stained as described in Materials and Methods. Optical sections of uninfected BMEC treated with drug are shown for microfilament organization on the apical side (A) and the basolateral side (B). The E. coli organisms were visualized by transmitted light optics (C) and actin staining of the infected BMEC (D).

Role of microtubules in E. coli invasion.

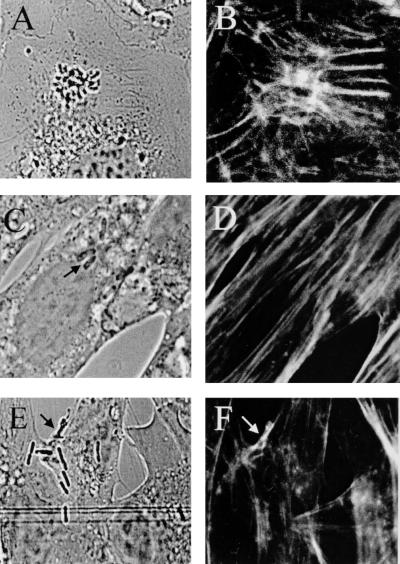

Microtubules have been shown to be involved in the uptake processes of several bacteria (e.g., E. coli, Citrobacter freundii, and Neisseria) into human epithelial cells (4, 11, 15) and also in the uptake of Candida albicans by human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) (2). The involvement of the microtubule network in E. coli invasion of BMEC was examined with the microtubule assembly inhibitors nocodazole, colchicine, vincristine, and vinblastine and the microtubule-stabilizing agent taxol. Confocal microscopy showed that all these drugs caused cellular retraction and flattening, indicative of microtubule disruption. This treatment did not affect the total number of bacteria associated with BMEC. In contrast, the invasive ability of E. coli was reduced by 50 to 60% with all the drugs (Fig. 2B). To further examine whether microtubule rearrangement is necessary for E. coli invasion, infected BMEC monolayers were stained with anti-tubulin antibody followed by TRITC-conjugated secondary antibody and examined with a confocal fluorescence microscope. Microtubule staining of uninfected BMEC showed a punctate pattern at the apical side (similar to the pattern shown in Fig. 5B). No change in microtubule staining was observed after infection of the BMEC monolayers with E44 (Fig. 5B), suggesting that microtubule reorganization may not be necessary for E. coli invasion. Nocodazole treatment of infected BMEC showed increased intensity of the punctate staining but no change in the pattern of association of E. coli with BMEC (Fig. 5C and D). Since these results contradict the results obtained from tissue culture invasion assays with microtubule inhibitors, the effect of nocodazole on microfilament organization was also examined. Unexpectedly, nocodazole treatment altered the actin filament pattern at the apical sides more significantly than it did at the basolateral sides of BMEC (Fig. 5E and F). Infected BMEC monolayers pretreated with the drug showed no actin condensation associated with bacteria in most places (Fig. 5G and H). These observations were reproducible in several experiments, suggesting that nocodazole indirectly affects microfilament organization, probably by affecting the downstream pathways common to microfilaments and microtubules.

FIG. 5.

Confocal micrographs showing the distribution of microtubules and microfilaments in infected BMEC after nocodazole treatment. Bacteria were visualized by transmitted light optics (A, C, and G). Microtubules were stained with anti-tubulin antibody and then with TRITC-conjugated secondary antibody (B and D). Uninfected (E and F) and infected (G and H) cells were stained with FITC-phalloidin to visualize actin after treatment with nocodazole. Arrows indicate the bacteria.

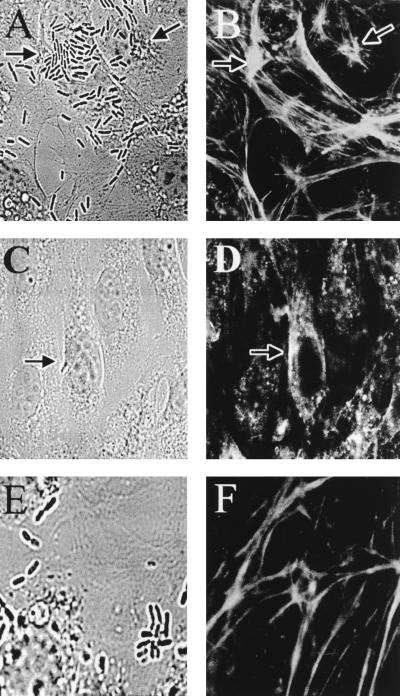

OmpA interaction with BMEC is required for F-actin condensation.

We have previously shown that OmpA contributes to E. coli invasion of BMEC via GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc epitopes of BMEC membrane proteins (18). To investigate whether OmpA+ and OmpA− strains show any differences in the condensation of F-actin, we tested the E105 (OmpA+) and E111 (OmpA−) E. coli strains for their ability to recruit F-actin. The OmpA+ strain E105 induced actin condensation to a level similar to that induced by E44 at the site of adherence (Fig. 6A and B) within 10 min postinfection, and actin condensation was considerably decreased after 45 min. In contrast, OmpA− strain E111-infected BMEC showed no accumulation of cellular actin, similar to what occurred with E412 (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Fluorescence micrographs showing the effect of peptide analogues that represent OmpA domains or OmpA receptor analogues on F-actin accumulation. The BMEC monolayers were infected with invasive OmpA+ E. coli E105 (A and B) and processed for fluorescence microscopy as described in Materials and Methods. For some experiments, the BMEC monolayers were treated with either N peptide (C and D) or H peptide (E and F) before the bacteria were added. The bacteria were visualized by transmitted light optics (A, C, and E). F-actin was stained with TRITC-phalloidin (B, D, and F). Arrows indicate the locations of bacteria.

To further verify whether the recruitment of actin at the site of E. coli attachment was due to OmpA interaction with GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc epitopes of BMEC, we examined wheat germ agglutinin, simple sugars, and synthetic peptides analogous in sequence to OmpA binding domains for their ability to block the interaction. Representative pictures are presented for the results of all these inhibitory experiments. Both wheat germ agglutinin and the receptor analogue GlcNAc1-4GlcNAc polymers (chitooligomers) blocked the recruitment of F-actin associated with E. coli. These agents did not show any effect on the microfilament organization of uninfected BMEC. The synthetic peptides N (Asn27-Gly-Pro-Thr-His-Glu32) and G (Gly65-Ser-Val-Glu-Asn69), which represent two domains on the adjacent extracellular portions of OmpA and showed significant inhibition of E. coli invasion into BMEC in our previous study (17), also blocked F-actin accumulation (Fig. 6C and D). In contrast, peptide H (His19-Asp-Thr-Gly22), which had no effect on E. coli invasion, did not show efficient blocking (Fig. 6E and F). These results are in agreement with our invasion data, suggesting that these reagents inhibit the accumulation of F-actin associated with the bacteria by blocking OmpA interaction with BMEC.

Role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in E. coli invasion.

Since the interaction of OmpA with GlcNAc1-4GlcNAc epitopes present on BMEC glycoproteins is required for actin accumulation, we examined the contribution of receptor-mediated endocytosis in E. coli invasion of BMEC. Monodansylcadaverine (MDC), which blocks receptor-mediated endocytosis of various ligands (1), was used in the BMEC invasion assays. MDC treatment of BMEC prior to infection with E. coli blocked invasion by more than 80% compared to the level of invasion in untreated control BMEC (15,220 ± 3,300 CFU/well for E44 versus 2,920 ± 300 CFU/well for E44 with 10 μM MDC [P < 0.003] and 615 ± 135 CFU/well with 50 μM MDC [P < 0.001]) (Fig. 2C). The effect of MDC at these concentrations on receptor-mediated endocytosis was verified by demonstrating its inhibitory effect on diphtheria toxin-mediated cytotoxicity in BMEC (data not shown), which is known to occur via clathrin-coated-receptor-mediated endocytosis (13). To verify whether clathrin is associated with bacterial entry, we attempted to visualize the association of clathrin with bacteria by staining BMEC infected with E105 with anti-clathrin antibodies. Fluorescence microscopy of noninfected cells revealed a bright and punctate staining pattern, but fluorescence microscopy of infected BMEC showed no detectable recruitment of clathrin at the site of bacterial entry (Fig. 7). To rule out the possibility that the observed inhibitory effect with MDC was not due to blocking of F-actin recruitment, as with the microtubule inhibitor, the effect of MDC on microfilament organization was also examined by fluorescence microscopy. As shown in Fig. 8, the microfilament network was not affected by MDC treatment and the bacteria could still induce actin accumulation underneath. These results suggest that MDC inhibition of E. coli invasion may be due to its effect on other unknown cellular pathways required for invasion but not to microfilament disruption.

FIG. 7.

Confocal micrographs showing the distribution of clathrin. Anti-clathrin antibody staining of uninfected (A) and infected (C) BMEC shows the location of clathrin as dots. Bacteria were visualized by transmitted light optics (B). The arrow indicates the cluster of bacteria associated with BMEC.

DISCUSSION

The specificity of a bacteria-host cell interaction and the pattern of tissue distribution of host cell receptors determine which tissues are ultimately the targets of infection by bacteria. The blood-brain barrier, which is made up of a layer of BMEC, is a target for E. coli K1 in gaining access to the brain to cause meningitis. Although nonbrain endothelial cells have generally been used to study the interactions of the E. coli organisms causing meningitis with eukaryotic cells, our previous studies indicated that E. coli invasion was specific to BMEC but not to systemic endothelial cells such as HUVEC. Of note, the invasion by E. coli of HUVEC was negligible for up to 1 h of incubation, whereas the invasion of BMEC occurred within 1 h (11, 17, 18). Extended incubation of E. coli with BMEC beyond 4 h resulted in a lifting of the monolayers, a phenomenon not observed with HUVEC. These observations from in vitro invasion assays suggest that BMEC are significantly different from other endothelial cells, and it is important to examine the E. coli invasion of BMEC to gain a better understanding of the mechanism(s) of invasion.

Our results indicate that E. coli K1 invades cultured BMEC, as observed by TEM, primarily through a zipper-type mechanism. This process involves direct contact of bacteria with BMEC membranes, which sequentially encircle the organisms, similar to what occurs with Yersinia (26) and Listeria (24) entry into epithelial cells. Interestingly, one end of the E. coli organism appears to interact with BMEC to induce the endocytic process, which may indicate that some adhesins or invasins are polarly localized. The intracellular location of individual bacteria has always been observed to be in a membrane-bound vacuole and never free in cytoplasm. Location in a membrane-bound vacuole is perhaps an intermediate step in a transcytosis pathway. This suggests that E. coli may not be able to escape the vacuole and support its own movement in BMEC, as has been reported for Shigella, Listeria, and Rickettsia spp. in epithelial cells (5, 24, 25). The induction of a phagocytosis-like endocytic mechanism by E. coli depends on microfilaments of BMEC, as evidenced by the finding that cytochalasin D and latrunculin A inhibit internalization by more than 90%. E. coli entry into BMEC induces a local accumulation of polymerized actin that is associated with the bacterium, in agreement with the microfilament inhibition data. This mechanism of E. coli invasion may be similar to that described for N. gonorrhoeae in recruiting the microfilaments at the site of adherence (4). However, the effects of cytochalasin D differ between E. coli and Neisseria. As shown in the present study, E. coli could not recruit F-actin, whereas Neisseria was still able to condense F-actin in the presence of cytochalasin D. It is not known at this time why some but not all E. coli organisms associated with BMEC induce actin condensation. It may be that the receptors for E. coli determinants are present only on a subpopulation of BMEC and that the E. coli organisms engaged with these receptors can induce actin condensation while other bacteria just settle on the surfaces of BMEC.

We also observed that microtubule-depolymerizing drugs inhibited E. coli invasion of BMEC. Unlike with the microtubule inhibition results, no significant changes of microtubule staining following E. coli interaction with BMEC could be observed. Surprisingly, nocodazole treatment had some effect on microfilament staining, i.e., fewer cortical filaments, in uninfected cells, whereas E. coli-infected BMEC showed no actin accumulation associated with bacteria. Thus, the inhibitory effect of nocodazole, and probably of other microtubule-inhibitory drugs, on E. coli invasion may be due to blocking of pathways that are common to microfilaments and microtubules. Alternatively, these drugs may inhibit the transport of membrane-bound bacteria from the plasma membrane through the cytoplasm by preventing their movement along the microtubules or by inhibiting the actin-myosin-mediated contractile processes (9). It is possible that the invasion of E. coli into BMEC is a more complex mechanism, involving both microfilaments and microtubules. Such mechanisms of pathogen-host interactions have been described for enteropathogenic E. coli, N. gonorrhoeae, Citrobacter freundii, and group B streptococci (4, 8, 14, 15).

In our previous studies, we have shown that OmpA expression in E. coli significantly enhances the invasion into BMEC compared to the level of invasion of E. coli lacking OmpA. We have further shown that, in invasion, OmpA binds to the GlcNAc1-4GlcNAc epitopes of cell surface glycoproteins, which are present specifically on BMEC but not on systemic endothelial cells (17). In agreement with these observations, OmpA-expressing E. coli induced actin accumulation within 10 to 20 min of infection of BMEC whereas non-OmpA-expressing E. coli showed no sign of being capable of inducing actin accumulation under the experimental conditions employed. Results of inhibition studies using chitooligomers and synthetic peptides of OmpA extracellular loops suggest that BMEC glycoproteins containing GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc epitopes may be involved in transducing the signal for actin polymerization and the taking up of bacteria by BMEC. However, E. coli E412, which also expresses OmpA, was noninvasive of BMEC and failed to recruit cellular actin, suggesting that OmpA interaction with BMEC alone is not sufficient for invasion of E. coli into BMEC. It is possible that interaction of OmpA with BMEC induces the expression or release of other microbial factors necessary for invasion of E. coli. Alternatively, OmpA interaction with the GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc epitopes of its receptor may modulate the receptor(s) on BMEC for Ibe10 interaction, which may subsequently trigger actin reorganization. This possibility is in contrast to the entry mechanism utilized by Yersinia spp., where one single protein, invasin, promotes adherence and actin rearrangement for internalization (26). The invasion mechanisms of Shigella, Salmonella, and EPEC also appear to be multifactorial, involving several gene products (7, 8, 12). Since OmpA is a highly conserved protein, the multifactorial virulence of the neurotropic nature of E. coli might have been evolved to exploit intrinsic features of a household protein.

The OmpA-promoted cytoskeletal rearrangement associated with E. coli invasion of BMEC may require the activation of signal transduction pathways in BMEC for the uptake of the bacteria. Protein tyrosine phosphorylation by tyrosine kinases that regulate cellular signals is generally responsible for actin polymerization. Accordingly, we showed that inhibitors of protein tyrosine kinases completely blocked the invasion of E. coli into BMEC (20). Furthermore OmpA+ strains significantly increased the tyrosine phosphorylation of BMEC proteins within 10 to 20 min of infection compared to that of OmpA− strains. In contrast, increased tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins was not observed after interaction of OmpA+ strains in HUVEC under our experimental conditions (unpublished results). Thus, the invasion of E. coli into BMEC may be a result of a specific interaction of E. coli determinants acting cooperatively with corresponding ligands on BMEC that trigger the fast uptake of bacteria. It will be interesting to see whether expression of BMEC receptor molecules specific for E. coli increases invasion of nonbrain endothelial cells similar to that of BMEC.

Taken together, our previous and present findings suggest that E. coli invasion of BMEC may involve a series of discrete events, i.e., S-fimbria-mediated binding of E. coli to NeuAcα2,3Gal epitopes of the 65-kDa BMEC surface protein (19) followed by OmpA attachment to GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc epitopes of BMEC glycoproteins. The OmpA interaction with GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc epitopes may regulate another receptor(s) in triggering signals in eukaryotic cells for actin polymerization and/or in bacteria for expression of new gene products involved in invasion. This speculation is under investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the excellent technical assistance of Ernesto Barron of the Doheny Eye Institute confocal microscope core facility at the University of Southern California School of Medicine, funded by NEI/NIH core grant EY03040. We also thank Barbara Driscoll for a critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH grant R29 AI40567 (N.V.P) and partly by NIH grant NS26310 (K.S.K.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Davies P J A, Davies D R, Levitzki A, Maxfield F R, Milhaud P, Willingham M C, Pastan I. Transglutaminase is essential in receptor-mediated endocytosis of α2-macroglobulin and polypeptide hormones. Nature (London) 1980;283:162–167. doi: 10.1038/283162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filler S G, Swerdloff J N, Hobbs C, Luckett P M. Penetration and damage of endothelial cells by Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1995;63:976–983. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.976-983.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garner A M, Kim K S. The effects of Escherichia coli S-fimbriae and outer membrane protein A on rat pial arterioles. Pediatr Res. 1996;39:604–608. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199604000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grassme H U C, Ireland R M, van Putten J P M. Gonococcal opacity protein promotes bacterial entry associated rearrangements of the epithelial cell actin cytoskeleton. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1621–1630. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1621-1630.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heinzen R A, Hayes S F, Peacock M G, Jackstadt T. Directional actin polymerization associated with spotted fever group Rickettsia infection of Vero cells. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1926–1935. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1926-1935.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang S H, Wass C A, Fu Q, Prasadarao N V, Stins M F, Kim K S. Escherichia coli invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo: molecular cloning and characterization of invasion gene ibe10. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4470–4475. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4470-4475.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isberg R R, Tran Van Nhieu G. Two mammalian cell internalization strategies used by pathogenic bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:10–14. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.28.120194.002143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenny B, Finlay B B. Protein secretion by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is essential for transducing signals to epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7991–7995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolodny M S, Elson E L. Contraction due to microtubule disruption is associated with increased phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10252–10256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamaze C, Fujimoto L M, Yin H L, Schmid S L. The actin cytoskeleton is required for receptor-mediated endocytosis in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20332–20335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meier C, Oelschlaeger T A, Merkert H, Korhonen T K, Hacker J. Ability of Escherichia coli that causes meningitis in newborns to invade epithelial and endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2391–2399. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2391-2399.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menard R, Sansonetti P, Parsot C, Vasselon T. Extracellular association and cytoplasmic partitioning of the IpaB and IpaC adhesins of Shigella flexneri. Cell. 1994;79:515–525. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moya M, Dautry-Varsat A, Goud B, Louvard D, Boquet P. Inhibition of coated pit formation in Hep2 cells blocks the cytotoxicity of diphtheria toxin but not that of ricin toxin. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:548–559. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.2.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nizet V, Kim K S, Stins M, Jonas M, Chi E Y, Nguyen D, Rubens C E. Invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells by group B streptococci. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5074–5081. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5074-5081.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oelschlaeger T A, Guerry P, Kopecko D J. Unusual microtubule-dependent endocytosis mechanisms triggered by Campylobacter jejuni and Citrobacter freundii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6884–6888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prasadarao N V, Stins M F, Wass C A, Kim K S. Role of S-fimbriae and outer membrane protein A in Escherichia coli binding to and invasion of endothelial cells. FASEB J. 1994;8:A70. . (Abstract.) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prasadarao N V, Wass C A, Weiser J N, Stins M F, Huang S H, Kim K S. Outer membrane protein A of Escherichia coli contributes to invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:146–153. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.146-153.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prasadarao N V, Wass C A, Kim K S. Endothelial cell GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc epitopes for outer membrane protein A enhance traversal of Escherichia coli across the blood-brain barrier. Infect Immun. 1996;64:154–160. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.154-160.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasadarao N V, Wass C A, Kim K S. Identification and characterization of S fimbria-binding sialoglycoproteins on brain microvascular endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2852–2860. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2852-2860.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prasadarao N V, Zhou J, Wass C A, Arditi M A, Kim K S. Abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Tyrosine protein kinases are involved in Escherichia coli invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells, abstr. B-63; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prasadarao N V, Wass C A, Huang S H, Kim K S. Identification and characterization of a novel Ibe10 binding protein that contributes to Escherichia coli invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1131–1138. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1131-1138.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stins M F, Prasadarao N V, Ibric L, Wass C A, Luckett P M, Kim K S. Binding of S-fimbriated Escherichia coli to brain microvascular endothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1228–1236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stins, M. F., N. V. Prasadarao, J. L. Badger, F. Gilles, and K. S. Kim. Transfected human brain endothelial cells as a model to study bacterial binding, invasion, and transcytosis across the blood brain barrier. Submitted for publication.

- 24.Tilney L G, Portnoy D A. Actin filaments and the growth, movement, and spread of the intracellular bacterial parasite, Listeria monocytogenes. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:1597–1608. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasselon T, Mounier J, Hellio R, Sansonetti P. Movement along actin filaments of the perijunctional area and de novo polymerization of cellular actin are required for Shigella flexneri colonization of epithelial Caco-2 cell monolayers. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1031–1040. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1031-1040.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young V, Falkow S, Schoolnik G K. The invasin of Yersinia enterocolitica: internalization of invasin bearing bacteria by eukaryotic cells is associated with reorganization of cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol. 1997;116:197–207. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]