Abstract

Interleukin 12 (IL-12) plays an important role in the induction of protective immunity against cancer and infectious diseases. In this study we asked whether IL-12 cDNA could increase the protective capacity of the antigen 2 (Ag2) gene vaccine in experimental coccidioidomycosis. Coimmunization of BALB/c mice with a single-chain IL-12 cDNA (p40-L-p35) and Ag2 cDNA, both subcloned into the pVR1012 plasmid, significantly enhanced protection against systemic challenge with 2,500 arthroconidia, as evidenced by a greater-than-1.3-log-unit reduction in the fungal load in the lungs and spleens compared to mice receiving the pVR1012 vector alone, Ag2 cDNA alone, or IL-12 cDNA alone. The enhanced protection was associated with increased gamma interferon secretion; production of immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a), IgG2b, and IgG3 antibodies to Coccidioides immitis antigen; and the influx of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in lungs and spleens. When challenged by the pulmonary route, mice covaccinated with Ag2 cDNA and IL-12 cDNA were not protected at the lung level but did show a significant reduction in the fungal load in their livers and spleens compared to mice vaccinated with Ag2 cDNA or IL-12 cDNA alone. These results suggest that IL-12 acts as a therapeutic adjuvant to enhance Ag2 cDNA-induced protective immunity against experimental coccidioidomycosis through the induction of Th1-associated immune responses.

Interleukin 12 (IL-12), a heterodimeric cytokine composed of a 40-kDa chain and a 35-kDa chain (35), is produced by a variety of antigen-presenting cells, including monocytes, macrophages, and B cells (24, 40, 41). It displays a potent array of biological activities affecting natural killer (NK) and T cells. These biological activities include the ability to enhance the proliferation of T and NK cells; increase cytolytic activities of T cells, NK cells, and macrophages; promote T helper 1 (Th1) cell development; and induce production of Th1-associated cytokines such as IL-2, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (3, 9, 24, 30, 38–41, 45). The induction of Th1-associated IFN-γ has been recognized as one of the most important functions of the IL-12-mediated cellular immune response against tumors and infectious diseases (9, 41, 45, 46).

Coccidioidomycosis is a fungal disease caused by inhalation of arthroconidia, the disarticulated mycelial phase of the dimorphic fungus Coccidioides immitis (37). This fungus is endemic in the arid southwestern United States and Mexico in the geographic area termed the lower Sonoran Life Zone, which also extends into parts of Central and South America. The disease displays symptoms ranging from a mild flu-like syndrome to frank pneumonia. About 5% of all cases result in severe, disseminated extrapulmonary disease. Investigations with humans and experimentally infected animals have documented that the severity of coccidioidomycosis directly correlates with depressed cell-mediated immune responses, evidenced by decreased skin test reactivity and the production of IFN-γ and IL-2 in response to coccidioidal antigens (4, 11, 14, 16, 28). It has been also established that recovery from primary infection is accompanied by strong cell-mediated immune responses to C. immitis antigens and lifelong immunity against reinfection (13, 15, 37).

Our previous studies showed that IL-12 plays a central role in the induction of host defenses against C. immitis (29). Administration of recombinant IL-12 before and during the course of the disease was shown to protect BALB/c mice against challenge with C. immitis and to effect a shift in the Th1 response. Whereas control BALB/c mice demonstrated low levels of IFN-γ mRNA expression and high levels of IL-4 mRNA, recombinant IL-12-treated mice exhibited high levels of IFN-γ message expression and low levels of IL-4 mRNA. More recently, we reported that immunotherapy of BALB/c mice with J774 macrophages that had been transduced with a plasmid expressing IL-12 cDNA ameliorated the course of the disease (21). The decrease in disease severity was associated with increased production of IFN-γ. These results, together with reports by others that IL-12 cDNA amplifies Th1 responses to microbial vaccines (2, 3, 10, 19, 22, 36, 42–44), document the feasibility of using IL-12 cDNA as an adjuvant for vaccination against C. immitis.

Early studies with experimental animal models established that vaccination with killed spherules induces protection against pulmonary challenge with a lethal dose of C. immitis arthroconidia (27). Investigations by us (26) and others (25, 33) showed that the protective component resided in the cell walls and that cell wall extracts, enriched in antigen 2 (Ag2), induced protection against challenge with C. immitis. We recently cloned the gene that encodes Ag2 (47, 48) and showed that immunization of mice with the Ag2 gene induced protection against intraperitoneal challenge with 2,500 arthroconidia of C. immitis (20). Our results were corroborated in a recent study by Abuodeh et al. (1), who reported on the protective capacity of a gene which encodes a proline-rich antigen. This gene was previously shown to have a nucleotide sequence identical to that of Ag2 cDNA (17, 23).

The vaccine efficacy of Ag2 cDNA, coupled with the immunopotentiating effects of IL-12, prompted us to determine if IL-12 cDNA would enhance the induction of protective immunity in mice vaccinated with Ag2 cDNA. Our results demonstrate that an IL-12-expressing plasmid has potent adjuvant activity for enhancing Ag2 cDNA-induced protective immunity and the induction of Th1 responses after systemic challenge with C. immitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of recombinant plasmids.

The full-length (194-nucleotide) Ag2 cDNA was subcloned into the XbaI site of the eukaryotic expression vector plasmid pVR1012 as previously reported (20).

Details of the procedure for the construction of a single chain of murine IL-12 cDNA have been published earlier (21). Briefly, the cDNAs for the p40 and p35 subunits of IL-12 were amplified by PCR and then linked with a synthetic linker by second-round PCR. The 1.66-kb PCR fragment was cloned into the pCR2.1 vector (InVitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) and sequenced. To prepare the IL-12-expressing pVR1012 plasmid, the NotI-BamHI fragment of murine IL-12 was removed from pCR2.1-IL-12 cDNA and then subcloned into the pVR1012 plasmid. Previous experiments established that the recombinant pVR1012-IL-12 plasmid expressed IL-12 mRNA, as measured by reverse transcription-PCR, and was bioactive, as judged by the induction of IFN-γ by BALB/c spleen cells after incubation with the supernatant from IL-12-transduced J774 macrophages (21).

To prepare plasmid DNA for immunization, Escherichia coli XL-Blue cells were transformed with either pVR1012-Ag2, pVR1012-IL-12, or the pVR1012 plasmid alone and then cultured at 37°C for 16 h in Luria broth supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml). Plasmid DNA was isolated by using an EndoFree plasmid purification kit (Qiagen, Santa Clara, Calif.). The DNA was resuspended in USP saline (Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Deerfield, Ill.) and stored at −20°C until used.

Immunization and challenge.

Five-week-old female BALB/c (H-2d) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). The mice were maintained for at least 1 week before use.

DNA immunization was performed by injecting groups of mice intramuscularly with 50 μg of pVR1012-Ag2 plus 5 μg of pVR1012-IL-12. These doses were shown to be optimal in a series of preliminary experiments. Comparative controls consisted of mice vaccinated with 50 μg of pVR1012 DNA alone, 50 μg of pVR1012-Ag2 cDNA alone, or 5 μg of pVR1012-IL-12. Before each injection, the mice were lightly anesthetized via inhalation of Metofane (Mallinckrodt Veterinary, Inc., Mundelein, Ill.). Injections were given in the tibialis anterior muscle in a site that had been treated with Nair (Carter-Wallace, Inc., New York, N.Y.) 1 day before administration of the first injection. A total of three immunizations were given at weekly intervals in alternating sites on the left and right legs, and the mice were challenged 2 weeks after the last immunization.

Challenge and assessment of disease severity.

Arthroconidia were harvested from 4- to 8-week-old mycelium-phase cultures of C. immitis CC, a recent isolate from a patient with disseminated coccidioidomycosis. The arthroconidial suspensions were passed over a nylon column to remove hyphal elements, and the cells were enumerated by hemacytometer counts. Mice were infected by an intraperitoneal injection with 2,500 arthroconidia suspended in 0.5 ml of pyrogen-free saline or an intranasal instillation of 50 arthroconidia suspended in 30 μl of pyrogen-free saline. The viability of the inocula was confirmed by plate counts on 1% glucose–2% yeast extract agar.

Vaccine-induced protection was evaluated by determining the numbers of C. immitis CFU in the lungs, spleens, and livers at 12 days postinfection as detailed earlier (20). At sacrifice, the organs were weighed, and the results obtained were expressed as log10 CFU per gram of tissue.

Cytokine induction.

Spleens were harvested at day 12 after challenge and processed as described above for single-cell suspensions (20). The cultures were stimulated with the C. immitis cell wall extract C-ASWS, which contains native Ag2 (12); concanavalin A (ConA) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.); or medium alone. After a 48-h incubation at 37°C under 5% CO2, the supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C until assayed.

Cytokine expression for IFN-γ and IL-4 was assayed by two-site sandwich enzyme-linked immunoassays (ELISA) as described previously (20, 21). All ELISA reagents were purchased from PharMingen, San Diego, Calif. Recombinant IFN-γ and IL-4 proteins were used to prepare standard curves.

Analysis of serum IgG isotypes.

Blood was collected from mice on the day before challenge and 12 days after challenge. The sera were harvested and stored at −20°C until assayed for immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody isotypes by ELISA. Wells on a 96-well microtiter plate were coated with 100 ng of coccidioidin, prepared as a toluene-induced lysate of young mycelia (34). Twofold serial dilutions of mouse sera were added, and after a 1-h incubation at room temperature, the plates were washed and incubated for 1 h with goat anti-mouse IgG1, rabbit anti-mouse IgG2a, goat anti-mouse IgG2b, or goat anti-mouse IgG3, each conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Zymed, South San Francisco, Calif.). The wells were washed, and the p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate (Sigma) was added to obtain color development in 30 min. The reactions were read at 410 nm on an MR 700 microplate reader (Dynatech Laboratories).

FACS analysis.

Spleens were gently teased to obtain single-cell suspensions. The cells were suspended in cold Hanks' balanced salt solution and treated with isotonic ammonium chloride to lyse erythrocytes. The splenocytes were washed by centrifugation and resuspended in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (DMEM) (GIBCO, Grand Island, N.Y.) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS).

Fresh lung tissue was cut into small pieces with scissors and incubated in DMEM containing 10% FCS, DNase I (100 U/ml; Sigma), and collagenase (1 mg/ml; Sigma). After a 30-min incubation at 37°C under 5% CO2, the digested samples were washed, and the erythrocytes were lysed with ammonium chloride. The lung cells were passed through a nylon mesh to remove large tissue fragments, washed by centrifugation, and resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS.

A total of 106 splenocytes or lung cells were distributed into a series of polypropylene tubes and washed three times with fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) buffer (phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% FCS and 0.11% sodium azide). The cells were incubated for 10 min with rat anti-mouse CD16 monoclonal antibody (PharMingen) to block Fc receptors and then double stained with saturating concentrations of phycoerythrin-conjugated hamster anti-mouse CD3 plus fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD45R/B220 monoclonal antibody, FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD4, or FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD8, all from PharMingen. After a 30-min incubation on ice, the cells were washed by three centrifugations in FACS buffer, fixed by overnight incubation in 1% formalin, and then analyzed with a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.).

Statistical analyses.

The data were analyzed by using the Wilcoxon rank-sums test. Probability values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Enhanced efficacy of the Ag2 cDNA vaccine by the IL-12 expressing plasmid.

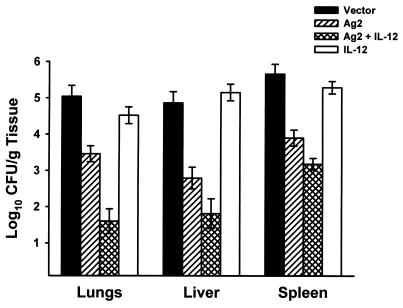

To determine if IL-12 cDNA would increase the protective capacity of the Ag2 gene vaccine, BALB/c mice were coinjected with pVR1012-Ag2 and pVR1012-IL-12 or, for comparative controls, pVR1012-Ag2 alone, pVR1012-IL-12 alone, or the pVR1012 plasmid. After three immunizations, the mice were challenged with 2,500 arthroconidia via an intraperitoneal route and then sacrificed 12 days later and evaluated for fungal CFU in the lungs and spleens. The results are shown in Fig. 1. Consistent with our earlier investigation (20), mice vaccinated with Ag2 cDNA showed a significant reduction in the fungal load in their lungs (P < 0.0001), livers (P < 0.0001), and spleens (P < 0.0001) compared to mice vaccinated with the pVR1012 vector alone. Mice vaccinated with both IL-12 cDNA and Ag2 cDNA were even more protected. The fungal loads in lungs, livers, and spleens from mice given the combined vaccine were reduced by 54% (P < 0.001), 35%, (P < 0.0001), and 19% (P > 0.05), respectively, compared to the number of CFU in mice given Ag2 cDNA alone. Compared to the vector control group, recipients of the combined vaccine showed a 68% reduction in the CFU in their lungs (P < 0.0001), a 63% reduction in their liver CFU (P < 0.0001), and a 44% reduction in the fungal load in their spleens (P < 0.0001). Vaccination with pVR1012-IL-12 alone did not protect mice against systemic challenge.

FIG. 1.

Protection in BALB/c mice immunized with the pVR1012 vector, pVR1012-Ag2 alone, pVR1012-Ag2 plus pVR1012-IL-12, or pVR1012-IL-12. Mice were challenged with 2,500 arthroconidia via an intraperitoneal route and evaluated for fungal CFU in tissues 12 days after challenge. Results depict means and standard errors obtained in two experiments, each with 10 mice per group.

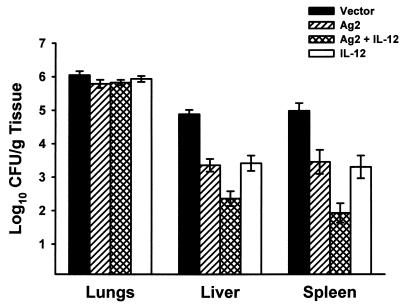

Since primary coccidioidomycosis is acquired via inhalation, we examined protection in the vaccine groups after pulmonary challenge with 50 arthroconidia. The results (Fig. 2) showed that mice vaccinated with pVR1012-Ag2 plus pVR1012-IL-12 had significantly decreased numbers of fungal CFU in their spleens and livers compared with mice vaccinated with pVR1012-Ag2 alone (P < 0.0001), pVR1012-IL-12 alone (P < 0.001), or the pVR1012 vector alone (P < 0.0001). IL-12 cDNA alone also effected a reduction in the CFU in spleens and livers of mice challenged by the pulmonary route. This is an anomalous finding, considering that IL-12 cDNA alone did not induce protection against an intraperitoneal challenge. None of the vaccine groups showed a decrease in the fungal load in lungs.

FIG. 2.

Protection in BALB/c mice immunized with the pVR1012 vector, pVR1012-Ag2 alone, pVR1012-Ag2 plus pVR1012-IL-12, or pVR1012-IL-12. Mice were challenged with 50 arthroconidia via the pulmonary route and evaluated for fungal CFU in tissues 12 days after challenge. Results depict means and standard errors obtained in two experiments, each with 10 mice per group.

Enhanced induction of IFN-γ.

The foregoing results established that the Ag2 gene vaccine combined with an IL-12-expressing plasmid induced a significantly higher level of protection in mice than either Ag2 cDNA or IL-12 cDNA alone. Since we and others have shown that the induction of Th1-associated cellular responses is crucial to the host defense against C. immitis (8, 15, 28), spleen cells were collected from mice at 12 days postinfection and assayed for the production of the Th1- and Th2-associated cytokines IFN-γ and IL-4, respectively.

Spleen cells from mice coimmunized with the Ag2- and IL-12-expressing plasmids secreted IFN-γ constitutively, as evidenced by the detection of 600 pg of IFN-γ in supernatants from the cells cultured in medium alone (Table 1). Stimulation of the splenocytes with C-ASWS resulted in a twofold increase in IFN-γ production. Splenocytes from mice vaccinated with Ag2 cDNA alone also secreted IFN-γ in response to C-ASWS, but at a much lower level than that obtained with spleen cells from mice coimmunized with Ag2 and IL-12. As expected, IFN-γ secretion was not induced in C-ASWS-stimulated spleen cells from mice immunized with the pVR1012 vector alone or pVR1012-IL-12 alone. When stimulated with ConA, spleen cells from all four groups of mice secreted IFN-γ, with the highest level noted in recipients of the combined Ag2–IL-12 vaccine.

TABLE 1.

Production of IFN-γ and IL-4 by in vitro-stimulated spleen cells from immunized mice

| Stimulanta | IFN-γ and IL-4 production (pg/ml) in vaccine groupb:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pVR1012 alone

|

Ag2

|

Ag2 + IL-12

|

IL-12

|

|||||

| IFN-γ | IL-4 | IFN-γ | IL-4 | IFN-γ | IL-4 | IFN-γ | IL-4 | |

| Medium | <15c | <15 | <15 | <15 | 600 | <15 | 25 | <15 |

| ConA | 220 | <15 | 1,000 | 25 | 5,800 | <15 | 600 | <15 |

| C-ASWS | <15 | <15 | 330 | <15 | 1,200 | <15 | <15 | <15 |

ConA was used at 2 μg/ml; C-ASWS was used at 100 μg/ml.

Levels of IFN-γ and IL-4 in supernatant from 2 × 106 spleen cells obtained from groups of 10 BALB/c mice 12 days after challenge with 2,500 arthroconidia via an intraperitoneal route.

Lower limit of assay sensitivity.

In contrast to the increased production of the Th1-associated IFN-γ response, spleen cells from Ag2-vaccinated mice and from mice coinjected with the Ag2–IL-12 vaccine did not secrete the Th2 cytokine IL-4 in response to stimulation with C-ASWS. The lack of IL-4 production does not indicate suppression of this Th2 response by IL-12, since this cytokine was not produced by spleen cells from mice immunized with the vector alone or IL-12 alone (Table 1).

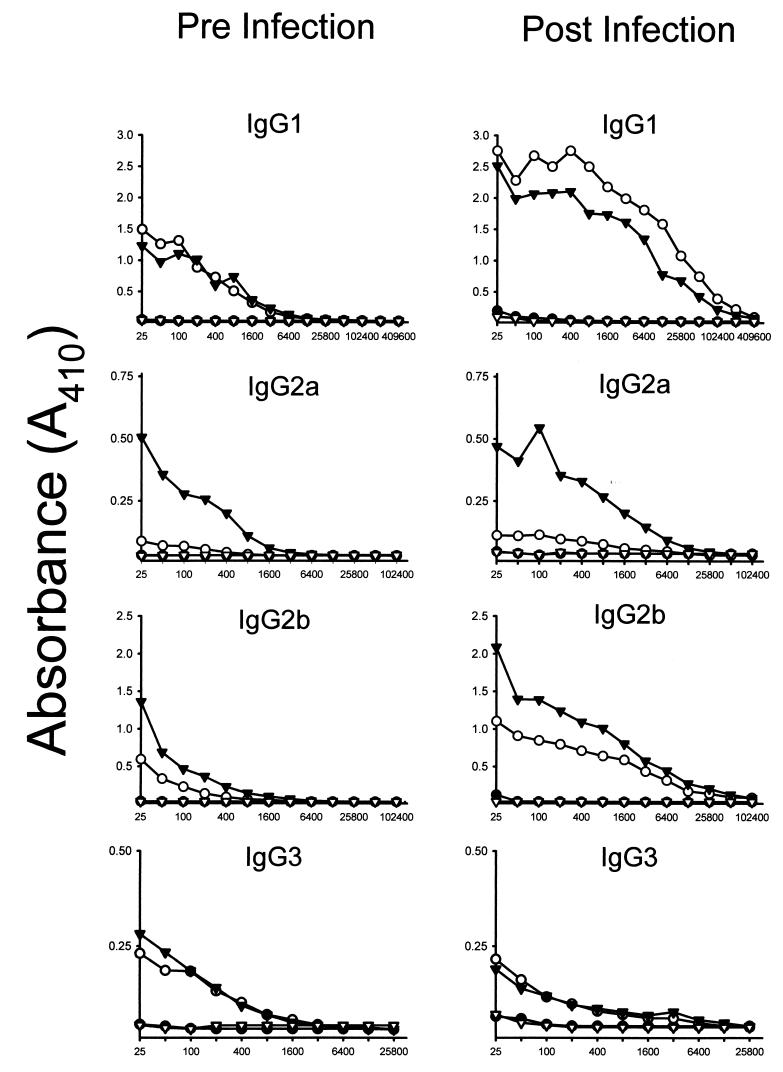

Induction of Ag2-specific IgG antibody responses.

The patterns of IgG antibody isotypes produced in response to immunization are reliable indicators of the types of cytokines induced in vivo (5, 18, 30–32). IFN-γ promotes the production of IgG2a, whereas IL-4 promotes the production of IgG1. Although the patterns are less clear with IgG2b and IgG3 isotypes, it is generally accepted that these are associated with IFN-γ production and are inhibited by IL-4 (5, 18).

To examine the humoral responses to the Ag2 gene vaccine and to determine if the responses were modulated by coadministration of the IL-12-expressing plasmid, sera were collected from mice on the day before and 12 days after challenge and assayed for IgG isotype antibodies to coccidioidin. As shown in Fig. 3, the combined Ag2–IL-12 vaccine induced the production of IgG2a in the sera of mice before and, to a greater level, after challenge with C. immitis. When compared with the antibody response of mice given Ag2 cDNA alone, the serum IgG2a levels in mice immunized with the combined Ag2-plus-IL-12 vaccine was increased by fourfold. Serum IgG2b and IgG3 antibodies were also induced in response to immunization with Ag2 cDNA alone or with cDNA, and while IgG3 levels were slightly reduced after challenge, IgG2b levels were increased. Although mice immunized with Ag2 cDNA showed only a low level of IL-4 production (Table 1), high levels of IgG1 antibodies were detected both before and after challenge. Surprisingly, administration of IL-12 cDNA in conjunction with Ag2 cDNA only slightly inhibited the production of IgG1 antibodies.

FIG. 3.

IgG antibody isotypes levels in sera obtained from BALB/c mice on the day before and 12 days after intraperitoneal challenge with 2,500 arthroconidia, as assessed by ELISA with coccidioidin as the target antigen. Results depict mean antibody levels in assays of sera pooled from groups of 10 mice immunized with vector (●), Ag2 (○), Ag2 plus IL-12 (▾), or IL-12 (▿).

FACS analyses of lung and spleen lymphocytes.

To characterize the cellular response to C. immitis in vaccinated mice, spleens and lungs were obtained from mice 12 days after systemic challenge and analyzed for lymphocyte populations by FACS. The results, expressed as the percentage of lymphocytes identified as CD3− B220+, CD3+ CD4+, or CD3+ CD8+ by double staining with FITC- or phycoerythrin-labeled antibodies against murine B cells and T-cell subpopulations, are summarized in Table 2. The most striking difference in the lymphocyte populations in the four mouse groups was the increase in the percentage of CD3+ CD8+ T cells in the lungs and spleens of mice coimmunized with Ag2- and IL-12-expressing plasmids compared to those in mice immunized with the vector alone, pVR1012-Ag2 alone, or pVR1012-IL-12 alone. A slight increase in the percentages of CD3+ CD4+ T cells in the lungs and spleens of recipients of the combined vaccine was also noted. B220+ B cells, on the other hand, were slightly increased in mice vaccinated with pVR1012-Ag2 alone or pVR1012-IL-12 alone compared to the percentages of B220+ B cells in mice vaccinated with the plasmid alone and mice covaccinated with Ag2- and IL-12-expressing plasmids.

TABLE 2.

Lymphocyte populations in lungs and spleens at day 12 postinfection

| Organ and lymphocyte population | % Positivea in vaccine group:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pVR1012 | Ag2 | Ag2 + IL-12 | IL-12 | |

| Lungb | ||||

| CD3− B220+ | 17.8 | 19.0 | 18.7 | 22.0 |

| CD3+ CD4+ | 17.5 | 18.8 | 19.6 | 13.8 |

| CD3+ CD8+ | 5.3 | 6.8 | 8.3 | 5.8 |

| Spleenc | ||||

| CD3− B220+ | 35.3 | 42.5 | 37.3 | 42.8 |

| CD3+ CD4+ | 18.6 | 17.8 | 21.4 | 16.6 |

| CD3+ CD8+ | 7.4 | 7.5 | 10.1 | 7.2 |

Percentage of lymphocytes that were positive when double stained with anti-mouse CD3 and B220, CD3 and CD4, or CD3 and CD8, as described in Materials and Methods.

The total numbers of lymphocytes recovered from the lungs of mice immunized with pVR1012, pVR1012-Ag2, pVR1012-Ag2 plus IL-12, and pVR1012-IL-12 were 2.30 × 107, 2.25 × 107, 3.45 × 107, and 3.20 × 107 respectively.

The total numbers of lymphocytes recovered from the spleens of mice immunized with pVR1012, pVR1012-Ag2, pVR1012-Ag2 plus IL-12, and pVR1012-IL-12 were 1.26 × 108, 1.32 × 108, 1.38 × 108, and 1.28 × 108, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This investigation established that coadministration of an IL-12-expressing plasmid in the highly susceptible BALB/c mouse strain enhances Ag2 cDNA vaccine-induced protection against systemic challenge with C. immitis. The enhanced protective effect was accompanied by an increased production of the Th1-associated cytokine IFN-γ, the production of anti-Ag2 IgG2a antibodies, and a cellular influx of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. These increased Th1-associated responses were accompanied, however, by only a modest inhibition of the Th2-associated IgG1 production.

IFN-γ has been recognized as one of the most important cellular immune responses in coccidioidomycosis (6, 7, 15, 28). We previously showed that treatment of the susceptible BALB/c mouse strain with recombinant IFN-γ ameliorated the course of the disease and, using the reciprocal approach, that neutralization of endogenous IFN-γ in the resistant DBA/2 mouse strain led to disease progression (28). The protective effects of IFN-γ were shown to reside, at least in part, in its ability to activate macrophages to an anticoccidioidal level (15). In this investigation, we found that IFN-γ was produced constitutively only by splenocytes from mice coimmunized with plasmids expressing Ag2 and IL-12 and that when stimulated with ConA or C-ASWS, splenocytes from recipients of the combined vaccine secreted more than fourfold-greater levels of IFN-γ than did spleen cells from mice receiving either Ag2 cDNA or IL-12 cDNA. The increased production of IFN-γ in response to the combined vaccine versus either component alone establishes a synergistic effect of Ag2 cDNA and IL-12 cDNA on the induction of this important Th1-associated cytokine. Although our results suggest that IFN-γ is crucial to the protective effect of the Ag2–IL-12 vaccine, studies are needed to show that treatment of mice with neutralizing anti-IFN-γ significantly diminishes or abrogates protection.

Previous studies have shown that adoptive transfer of T cells, but not serum, from immune mice protects recipients against challenge with C. immitis (8). Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were required for protection at the lung level, as evidenced by the lack of adoptive transfer after depletion of either subpopulation, whereas either T-cell subpopulation was able to transfer protection in spleens (15). In this investigation, analyses of lymphocyte populations in the lungs and spleens of mice covaccinated with Ag2 cDNA and IL-12 cDNA revealed increases in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Whereas studies have shown that CD4+ cells protect by secreting IFN-γ and other immunopotentiating cytokines (6–8, 15), the increase in CD8+ cells in lungs or spleens from mice having increased resistance to C. immitis raises the possibility that the CD8+ cells may exert a cytotoxic effect on the fungus.

IL-12 has been reported to be an important enhancer of IgG2a antibodies through the induction of IFN-γ (5, 18, 30–32). Our results showed that only the mice vaccinated with both the IL-12-expressing plasmid and Ag2 cDNA produced IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 antibodies. These increased Th1-associated antibody responses were accompanied, however, by only a modest inhibition of the Th2-associated IgG1 production. This is an unexpected result given that IFN-γ and not IL-4 was produced by C-ASWS-stimulated spleen cells from mice covaccinated with the Ag2- and IL-12-expressing plasmids. While it is recognized that antibody isotype responses may vary during the course of immunization and after challenge, owing to the changing dynamics of Th1 and Th2 responses, the predominance of IgG1 both before and after challenge is paradoxical and merits further study.

Although mice covaccinated with Ag2- and IL-12-expressing plasmids showed a decreased fungal load in their lungs and spleens following intraperitoneal challenge with C. immitis, the combined vaccine has limited effect on the fungal load in the lungs of mice challenged by the pulmonary route. We believe that induction of protective immunity at the lung level following pulmonary challenge may be achieved by targeted delivery of the combined Ag2–IL-12 vaccine directly to the lungs by using the adenovirus vector or DNA-liposome complexes. Since the disease is acquired via the pulmonary route, the induction of protection at the lung level remains a crucial goal for the development of a vaccine for use in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants AI32134 and AI21431 from the National Institutes of Health and by a grant from the California Health Care Foundation.

We gratefully acknowledge Teresa Quitugua, Melanie Woitaske, Isaac Rosas, and Yiqiang Zhang for their expert assistance in the animal studies. We also thank John Kalns at Brooks Aerospace Medical Center for assistance in the FACS analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abuodeh R O, Shubitz L F, Siegel E, Snyder S, Peng T, Osborn K I, Brummer E, Stevens D A, Galgiani J N. Resistance to Coccidioides immitis in mice after immunization with recombinant protein or a DNA vaccine of a proline-rich antigen. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2935–2940. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2935-2940.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afonso L C C, Scharton T M, Vieira L Q, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Scott P. The adjuvant effect of interleukin 12 in a vaccine against Leishmania major. Science. 1994;263:235–237. doi: 10.1126/science.7904381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahlers J D, Dunlop N, Alling D W, Nara P L, Berzofsky J A. Cytokine-in-adjuvant steering of the immune response phenotype to HIV-1 vaccine constructs. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and TNF-α synergize with IL-12 to enhance induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1997;158:3947–3958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ampel N M, Bejarano G C, Salas S D, Galgiani J N. In vitro assessment of cellular immunity in human coccidioidomycosis: relationship between dermal hypersensitivity, lymphocyte transformation, and lymphokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy adults. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:710–715. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.4.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arulanandam B P, Metzer D W. Modulation of mucosal and systemic immunity by intranasal interleukin 12 delivery. Vaccine. 1999;17:252–260. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beaman L. Fungicidal activation of murine macrophages by recombinant gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2951–2955. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.2951-2955.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaman L, Benjamini E, Pappagianis D. Activation of macrophages by lymphokines: enhancement of phagosome-lysosome fusion and killing of Coccidioides immitis. Infect Immun. 1983;39:1201–1207. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.3.1201-1207.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaman L, Pappagianis D, Benjamini E. Significance of T cells in resistance to experimental murine coccidioidomycosis. Infect Immun. 1977;17:580–585. doi: 10.1128/iai.17.3.580-585.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan S H, Perussia B, Gupta J W, Kobayashi M, Pospisil M, Young H A, Wolf S F, Yong D, Clark S C, Trinchieri G. Induction of interferon γ production by natural killer cell stimulatory factor: characterization of the responder cells and synergy with other inducers. J Exp Med. 1991;173:869–879. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow Y-H, Chiang B-L, Lee Y-L, Chi W-K, Lin W-C, Chen Y-T, Tao M-H. Development of Th1 and Th2 populations and the nature of immune responses to hepatitis B virus DNA vaccines can be modulated by codelivery of various cytokine genes. J Immunol. 1998;160:1320–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corry D B, Ampel N M, Christian L, Locksley R M, Galgiani J N. Cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in human coccidioidomycosis. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:440–443. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.2.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox R A, Britt L A. Antigenic heterogeneity of an alkali-soluble, water-soluble cell wall extract of Coccidioides immitis. Infect Immun. 1985;50:365–369. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.2.365-369.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox R A, Brumer E, Lecara G. In vitro lymphocyte responses of coccidioidin skin-test positive and -negative persons to coccidioidin, spherulin, and a Coccidioides immitis cell wall antigen. Infect Immun. 1977;15:751–755. doi: 10.1128/iai.15.3.751-755.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox R A, Kennell W, Boncyk L, Murphy J W. Induction and expression of cell-mediated immune responses in inbred mice infected with Coccidioides immitis. Infect Immun. 1988;56:13–17. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.1.13-17.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox R A, Magee D M. Protective immunity in coccidioidomycosis. Res Immunology. 1998;149:417–428. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(98)80765-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox R A, Vivas J R. Spectrum of in vivo and in vitro immune responses in coccidioidomycosis. Cell Immunol. 1977;31:130–141. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(77)90012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dugger K O, Willareal K M, Ngyuen A, Zimmermann C R, Law J H, Galgiani J N. Cloning and sequence analysis of the cDNA for a protein from Coccidioides immitis with immunogenic potential. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;218:485–489. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guery J-C, Galbiati F, Smiroldo S, Adorini L. Normal and β2-microglobulin-deficient BALB/c mice. J Exp Med. 1996;183:485–497. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irvine K R, Rao J B, Rosenberg S A, Restifo N P. Cytokine enhancement of DNA immunization leads to effective treatment of established pulmonary metastases. J Immunol. 1996;156:238–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang C, Magee D M, Quitugua T N, Cox R A. Genetic vaccination against Coccidioides immitis: comparison of vaccine efficacy of recombinant antigen 2 and antigen 2 cDNA. Infect Immun. 1999;67:630–635. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.630-635.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang C, Magee D M, Cox R A. Construction of a single-chain interleukin-12-expressing retroviral vector and its application in cytokine gene therapy against experimental coccidioidomycosis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2996–3001. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2996-3001.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J J, Ayyavoo V, Bagarazzi M L, Chattergoon M A, Dang K, Wang B, Boyer J D, Weiner D B. In vivo engineering of a cellular immune response by co-administration of IL-12 expression vector with DNA immunogen. J Immunol. 1997;158:816–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirkland T N, Finley F, Orsborn K I, Galgiani J N. Evaluation of the proline-rich antigen of Coccidioides immitis as a vaccine candidate in mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3519–3522. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3519-3522.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi M, Fitz L, Ryan M, Hewick R M, Clark S C, Chan S, Loudon R, Sherman F, Perussia B, Trinchiera G. Identification and purification of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF), a cytokine with multiple biological effects on human lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1989;170:827–845. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kong Y M, Levine H B, Smith C E. Immunogenic properties of nondisrupted and disrupted spherules of Coccidioides immitis in mice. Sabouraudia. 1963;2:131–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lecara G, Cox R A, Simpson R B. Coccidioides immitis vaccine: potential of an alkali-soluble, water-soluble cell wall antigen. Infect Immun. 1983;39:473–475. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.1.473-475.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine H B, Cobb J M, Smith C E. Immunogenicity of spherule-endospore vaccines of Coccidioides immitis for mice. J Immunol. 1961;87:218–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magee D M, Cox R A. Roles of gamma interferon and interleukin-4 in genetically determined resistance to Coccidioides immitis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3514–3518. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3514-3519.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magee D M, Cox R A. Interleukin-12 regulation of host defenses against Coccidioides immitis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3609–3613. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3609-3613.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKnight A J, Zimmer G J, Fogelman I, Wolf S F, Abbas A K. Effects of IL-12 on helper T cell-dependent immune responses in vivo. J Immunol. 1994;152:2172–2179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Metzger D W, McNutt R M, Collins J T, Buchanan J M, Cleve V H V, Dunick W A. Interleukin-12 acts as an adjuvant for humoral immunity through interferon-γ-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1958–1965. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosmann T R, Coffman R L. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pappagianis D, Hector R, Levine H B, Collins M S. Immunization of mice against coccidioidomycosis with a subcellular vaccine. Infect Immun. 1979;25:440–445. doi: 10.1128/iai.25.1.440-445.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pappagianis D, Smith C E, Kobayashi G S, Saito M T. Studies of antigens from young mycelia of Coccidioides immitis. J Infect Dis. 1961;108:35–44. doi: 10.1093/infdis/108.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schoenhaut D S, Chua A O, Wolitzky A G, Phyllis M, Quinn P M, Dwyer C M, McComas W, Familletti P C, Gately M K, Gubler U. Cloning and expression of murine IL-12. J Immunol. 1992;148:3433–3440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sin J-I, Kim J J, Arnold R L, Shroff K E, McCallus D, Pachuk C, McElhiney S P, Wolf M W, Pompa-de Bruin S J, Higgins T J, Ciccarelli R B, Weiner D B. IL-12 gene as a DNA vaccine adjuvant in a herpes mouse model: IL-12 enhances Th1-type CD4+ T cell-mediated protective immunity against herpes simplex virus-2 challenge. J Immunol. 1999;162:2912–2921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevens D A. Current concepts: coccidioidomycosis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1077–1082. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504203321607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sypek J P, Chung C L, Mayor S E H, Subramanyam J M, Goldman S J, Sieburth D S, Wolf S F, Schaub R G. Resolution of cutaneous leishmaniasis: interleukin 12 initiates a protective T helper type 1 immune response. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1797–1802. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tahara H, Zitvogel L, Storkus W J, Zeh III H J, McKinney T G, Schreiber R D, Gubler U, Robbins P D, Lotze M T. Effective eradication of established murine tumors with IL-12 gene therapy using a polycistronic retroviral vector. J Immunol. 1995;154:6466–6474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a cytokine produced by antigen-presenting cells with immunoregulatory functions in the generation of T-helper cells type 1 and cytotoxic lymphocytes. Blood. 1994;84:4008–4027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;152:1883–1887. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsuji T, Hamajima K, Fukushima J, Xin K-Q, Ishii N, Aoki I, Ishigatsubo Y, Tani K, Kawamoto S, Nitta Y, Miyazaki J-I, Koff W C, Okubo T, Okuda K. Enhancement of cell-mediated immunity against HIV-1 induced by coinoculation of plasmid-encoded HIV-1 antigen with plasmid expressing IL-12. J Immunol. 1997;158:4008–4013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wynn T A, Cheever A W, Jankovic D, Poindexter R W, Caspar P, Lewis F A, Sher A. An IL-12 based vaccination method for preventing fibrosis induced by schistosome infection. Nature. 1995;376:594–596. doi: 10.1038/376594a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wynn T A, Jankovic D, Hieny S, Cheever A W, Sher A. IL-12 enhances vaccine-induced immunity to Schistosoma mansoni in mice and decreases T helper 2 cytokine expression, IgE production, and tissue eosinophilia. J Immunol. 1995;154:4701–4709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zatloukal K, Schneeberger A, Berger M, Schmidt W, Koszik F, Kutil R, Cotton M, Wagner E, Buschle M, Maass G, Payer E, Stingl G, Birnstiel M L. Elicitation of a systemic and protective anti-melanoma immune response by an IL-12 based vaccine. J Immunol. 1995;154:3406–3419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou P, Sieve M C, Bennett J, Kwon-Chung K J, Tewari R P, Gazzinelli R T, Sher A, Seder R A. IL-12 prevents mortality in mice infected with Histoplasma capsulatum through induction of IFN-γ. J Immunol. 1995;155:785–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu Y, Yang C, Magee D M, Cox R A. Coccidioides immitis antigen 2: analysis of gene and protein. Gene. 1996;181:121–125. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu Y, Yang C, Magee D M, Cox R A. Molecular cloning and characterization of Coccidioides immitis antigen 2 cDNA. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2695–2699. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2695-2699.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]