Abstract

BACKGROUND

Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS) is a form of cyclic vomiting syndrome characterized by episodic vomiting occurring every few weeks or months and is associated with prolonged and frequent use of high-dose cannabis. CHS in the pediatric population has been increasingly reported over the last decade and can lead to life-threatening complications such as pneumomediastinum, which warrant careful consideration for surgical intervention.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 17-year-old female with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting for 24 hours. She had four episodes of green-yellow emesis followed by dry heaves. She also complained of chest and back pain, worse with deep inspiration. Upon further history, the patient reported a similar episode of abdominal pain and repetitive vomiting six months prior to the current episode. She smoked cannabis at least once daily and has done so for the past two years. Chest X-ray revealed a subtle abnormal lucency along the anteroposterior window and anterior mediastinum, consistent with a small amount of pneumomediastinum without any other acute intrathoracic abnormalities. Follow-up chest computed tomography with contrast showed multiple foci of air within the anterior and posterior mediastinum tracking up to the thoracic inlet. There was no evidence of contrast extravasation; however, small esophageal perforation could not be excluded. Given uncomplicated pneumomediastinum without frank contrast extravasation, the patient was treated medically with piperacillin-tazobactam, metronidazole, and micafungin for microbial prophylaxis; hydromorphone for pain control; as well as with pantoprazole, ondansetron, and promethazine. Nutrition was provided via total parenteral nutrition. The patient was intensely monitored for signs of occult esophageal perforation, but none were detected. She was advanced to a soft diet on hospital day eight, solid food diet on day nine, at which point antibiotics were discontinued, and the patient was subsequently discharged.

CONCLUSION

CHS in an increasingly common disorder encountered in the pediatric setting due to rising prevalence of cannabis use. The management of CHS and potentially life-threatening complications such as pneumomediastinum should be given careful consideration. Pneumomediastinum can be a harbinger of more sinister pathology such as esophageal perforation, which may warrant urgent surgical intervention.

Keywords: Hyperemesis, Cannabis, Pneumomediastinum, Pediatric, Management, Surgical Consultation

INTRODUCTION

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is a form of cyclic vomiting syndrome characterized by episodic vomiting that occurs periodically every few weeks or months and is associated with prolonged and frequent use of high-dose cannabis. First described in South Australia in 2004 by Allen JH, et al., CHS has been increasingly documented in the literature over the last decade [1]. This is likely due to increased prevalence of the legalization of recreational cannabis worldwide, including in the United States, as well as increased usage of cannabis products such as electronic vaping, edible products, and synthetic cannabinoids which may provide higher doses to users [2]. CHS is a rare complication, most often seen in patients who have used cannabis for a prolonged period of years and use cannabis on a frequent or daily basis [3]. Based on larger case series, it is most common in younger adults, although it appears to be increasingly relevant in adolescents and children despite fewer studies focusing on the pediatric population [2,4]. It is also more predominant in males.

In stark contrast to the well-known anti-emetic effects of cannabis, CHS presents with acute episodes of nausea, colicky abdominal pain, and vomiting, often without warning, that occur every few weeks or months with notable absence of symptoms between these episodes. This hyperemesis phase may be preceded by a prodromal phase, during which patients experience early morning nausea with occasional vomiting for a period of time prior to the development of cyclical hyperemesis [1].

During the hyperemesis phase, patients commonly experience other autonomic symptoms including flushing, increased thirst, sweating, and weight loss despite normal patterns of eating. Notably, many patients report a unique and characteristic behavior of repetitive, compulsive bathing in hot water, documented in a majority of patients [1,4].

Patients often report that the only way they can experience relief during symptomatic episodes is by taking very hot showers or baths. Patients may report that these behaviors are the only manner in which they experience relief of symptoms, as often the vomiting is refractory to anti-emetic medications.

The most concerning feature of CHS during symptomatic episodes is prolonged, repetitive vomiting. This can subsequently lead to severe dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, acute kidney injury, and several other potentially life-threatening complications related to repetitive, forceful vomiting [5,6]. These complications can include pneumomediastinum, esophageal perforation (Boerhaave syndrome), pneumothorax, and pneumopericardium [7–10]. Each of these can be devastating if not recognized and treated early; therefore, a high degree of suspicion should be maintained amongst primary care and emergency pediatric providers. Here, we report a case of CHS complicated by pneumomediastinum with concern for esophageal perforation. We provide an overview of the diagnosis and management of pneumomediastinum secondary to CHS, as well as a description of surgical implications of CHS for pediatricians and pediatric surgeons to consider in this increasingly documented syndrome.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 17-year-old female with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting for 24 hours. Her abdominal pain was mild, worse in the epigastric and right upper quadrant regions. She had four episodes of green-yellow emesis followed by dry heaves. On one of these occasions, she reported a few streaks of blood in her vomit. She also complained of chest and back pain, worse with deep inspiration. Upon further history, the patient reported a similar episode of abdominal pain and repetitive vomiting 6 months prior to the current episode. At that time, she did not seek medical attention, and the symptoms resolved after several days. The patient reported that she ate a lot of spicy, greasy food, but denied use of alcohol and tobacco. She did smoke cannabis at least once daily and had done so for the past two years. She reported that this helped her manage stress and anxiety as well as cope with a difficult family situation at home. She also felt weak and had dizziness when standing.

On physical examination at admission, the patient was afebrile, normotensive, mildly tachycardic, and tachypneic. She appeared anxious and distressed. Her abdomen was soft, non-distended, with normoactive bowel sounds. There was moderate tenderness to palpation in the right upper quadrant, left upper quadrant, and epigastric areas with voluntary guarding. During the initial exam, the patient began actively vomiting again, precluding further examination until the vomiting stopped.

The patient was initially given three liters of intravenous (IV) fluids, ondansetron 4 mg IV, aluminum and magnesium hydroxide-simethicone 200–200-20 mg/5 mL oral suspension, atropine/hyoscyamine/phenobarbital/scopolamine 16.2 mg/5 mL elixir, famotidine 20 mg IV, and made strictly nil per os (NPO). Abdominal ultrasound was performed and showed no sonographic evidence of cholelithiasis or acute cholecystitis. Her labs were largely unremarkable with complete blood count (including white blood cell count), basic metabolic panel, coagulation panel, liver function tests, and urinalysis within normal limits. The patient’s urine pregnancy test was negative. Urine toxicology test was positive for cannabis. Chest X-ray revealed a subtle abnormal lucency along the anteroposterior window and anterior mediastinum, consistent with a small amount of pneumomediastinum without any other acute intrathoracic abnormalities (Figure 1). Follow-up chest computed tomography (CT) with IV contrast showed multiple foci of air within anterior and posterior mediastinum tracking up to the thoracic inlet (Figure 2). There was no evidence of contrast extravasation; however, small esophageal perforation could not be excluded. This was further confirmed with a fluoroscopic esophageal swallow test using water soluble contrast which showed no evidence of contrast extravasation (Figure 3). Pediatric surgery was consulted for further recommendations on the management of pneumomediastinum and concern for contained esophageal perforation given the patient’s symptoms and the presence of pneumomediastinum.

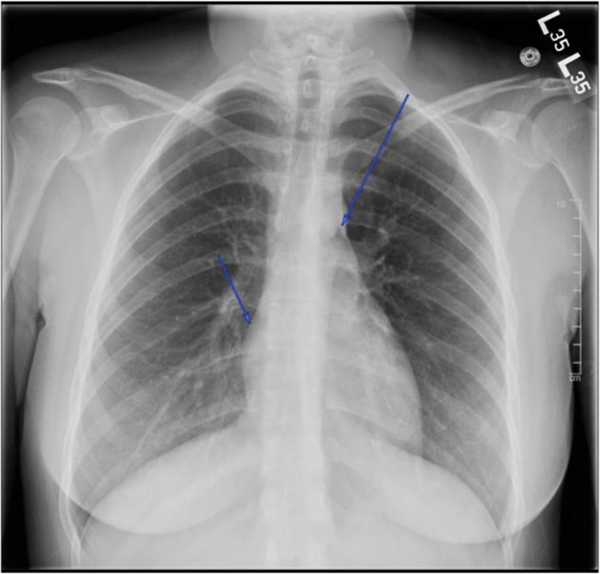

Figure 1:

Initial chest x-ray with evidence of pneumomediastinum in the setting of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome.

Note: Subtle abnormal lucency observed along the anteroposterior window and anterior mediastinum, consistent with a small amount of pneumomediastinum (arrows). Cardiomediastinal silhouette is normal in size. Pulmonary vasculature and hilar contours are within normal limits. Lungs are adequately expanded with no interstitial airspace opacity, pleural effusion, or discernible pneumothorax.

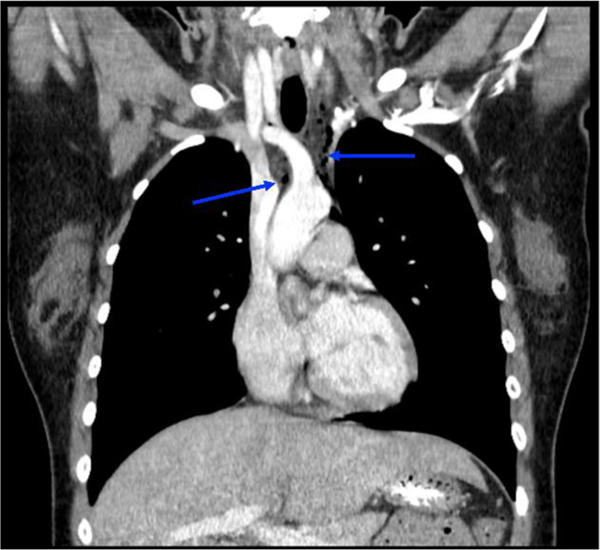

Figure 2:

Chest computed tomography (CT) with contrast confirms evidence of pneumomediastinum.

Note: Multidetector multiplanar CT images of the chest were obtained after administration of 70 mL iohexol IV contrast material. Foci of air were observed within the anterior and posterior mediastinum tracking up to the thoracic inlet (arrows), consistent with pneumomediastinum. There was no evidence of contrast extravasation; however, small esophageal perforation could not be excluded.

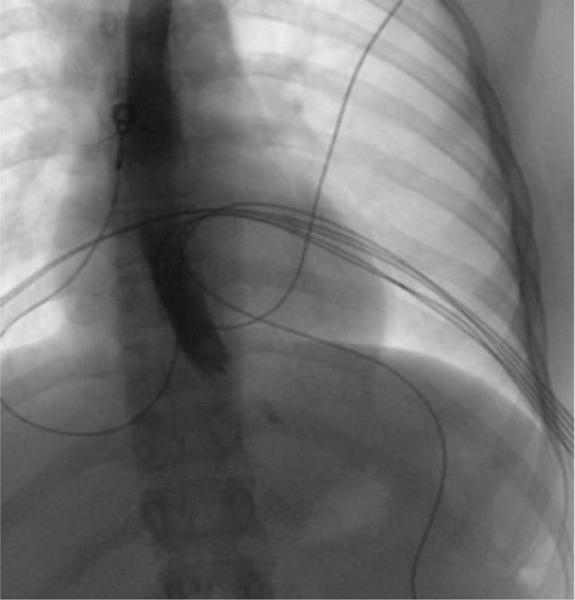

Figure 3:

Esophagram revealed no signs of extravasation, indicating lack of esophageal perforation.

Note: Following preliminary chest radiograph, the patient orally ingested water-soluble contrast solution, after which multiple fluoroscopic spot images were obtained. The esophagus was in normal position, without thickened folds, filling defect, abnormal contrast collection, or stricture. Normal peristalsis was observed under fluoroscopy.

Given uncomplicated pneumomediastinum without radiographic evidence of esophageal perforation, the patient was treated medically with piperacillin-tazobactam, metronidazole, and micafungin for microbial prophylaxis, hydromorphone for pain control, pantoprazole, ondansetron, promethazine, and kept NPO with nutritional supplementation via total parenteral nutrition. The patient was hemodynamically stable and admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) due to risk of acute decompensation. No surgical intervention was performed, although the patient was observed with repeated imaging studies due to concern for progression to complete esophageal perforation. Repeat chest X-ray at 24 and 48 hours after admission showed interval decreases in the degree of pneumomediastinum. The patient did not show any concerning signs for mediastinitis. Emesis began to decrease by hospital day three and was absent by day five, at which time the patient was advanced to a clear liquid diet. The patient was subsequently transferred from the PICU on hospital day five, with anti-emetic and antibiotic medications maintained. Patient was advanced to soft diet on hospital day eight, and solid food diet on day nine, at which point antibiotics were discontinued. The patient was discharged on hospital day 10 with scopolamine patch, prochlorperazine 10 mg, pantoprazole 40 mg daily, and PRN acetaminophen 325 mg. The patient was instructed to continue pantoprazole for one month. Ambulatory referrals were placed for pediatric gastroenterology and psychiatry for further follow-up and management, including discussion of abstinence from cannabis.

DISCUSSION

Cannabis is typically regarded as an antiemetic and is most notoriously known for the chemical compound tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The plant, however, contains over 400 different chemicals [2]. In the case of CHS, cannabis’s pro-emetic effect likely relates to high doses and chronic use leading to downregulation, desensitization, and internalization of cannabinoid receptors type 1 (CB1) and 2 (CB2). The gastrointestinal (GI) tract, including the enteric nervous system, has very high expression of these receptors [11]. One possible hypothesis for CHS is that overstimulation of these receptors leads to increased activity within the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in increased sympathetic stress response. Another hypothesis is that metabolism of cannabis over time can actually lead to the formation of pro-emetic compounds [12].

While there has been increased documentation of CHS within the literature, the incidence of pneumomediastinum has seldom been reported. Indeed, to our knowledge discussion of pneumomediastinum as a complication of CHS has only been mentioned in three other case reports, two in the United States and one in Spain [6–9]. In the case of our patient, uncomplicated pneumomediastinum could have been due to alveolar rupture which is often a self-limiting condition, commonly seen in tall, thin, adolescent men and can be related to hyperemesis [13]. Far more concerning was the possibility of an occult esophageal perforation. Spontaneous esophageal perforation has a mortality of up to 36%, usually due to delay in diagnosis [14]. As such, our patient was continuous l, § monitored for signs of esophageal perforation throughout the hospital course.

The differential and surgical implications of pediatric emesis are quite broad [15]. The surgical implications of CHS-induced pneumomediastinum in adolescents is far narrower, but the clinician should have a high suspicion for esophageal perforation and pneumothorax. Pneumothorax without tension physiology can often be managed with monitoring and supportive care alone, but intervention with a large bore needle, pigtail catheter, or chest tube should be given consideration. If a patient develops a pneumothorax in the setting of pneumomediastinum, they should be closely monitored for the possibility of tension physiology. Further, repeated retching or vomiting can be associated with two different esophageal injuries. Mallory-Weiss syndrome or gastroesophageal laceration syndrome occurs when there is bleeding from a laceration in the mucosa at the junction of the stomach and the esophagus and is likely not a full perforation. Boerhaave syndrome is a spontaneous perforation of the esophagus from a sudden increase in intraesophageal pressure.

If a perforation is suspected, then an X-ray and esophagram are both first-line imaging modalities. An X-ray may reveal a pleural effusion, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and possibly subdiaphragmatic air (Figure 1). An upper GI study with contrast (either water soluble or barium) should also be performed if there is suspicion for esophageal perforation (Figure 3). If you suspect that a patient could have a tracheoesophageal fistula or has an aspiration risk, then dilute barium should be used instead as Gastrografin can result in acute pulmonary edema. If an esophagram is positive, then there is no need for an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) prior to definitive management. If an upper GI study is equivocal, then an EGD is the next step if suspicion for perforation remains high. When an esophagram and EGD are performed in concert with one another they have a sensitivity of 95% for esophageal perforation detection [16].

It should also be noted that an EGD can cause an esophageal perforation to become a tension pneumothorax. The most common site for a spontaneous perforation is 2–3 cm above the gastroesophageal junction while the most common site of iatrogenic esophageal perforation is at the cricopharyngeus muscle or upper esophageal sphincter.

If a patient has no change in vital signs, the perforation is contained in the mediastinum, or more commonly, imaging is inconclusive (the case in our patient), then noninvasive management with antibiotics, antifungals, proton pump inhibitors (PPI), total parenteral nutrition, IV fluids, and close monitoring while keeping the patient NPO is the chosen treatment regimen. Length of antibiotic coverage and NPO status are patient- and provider-dependent, but continued pain, signs of infection, bleeding, or persistent signs of perforation on repeat X-ray or EGD would all be signs that a perforation is evolving and is not responding to conservative management. This would warrant consideration for potential surgical intervention.

Stents are an acceptable consideration for some esophageal perforations but are not widely used, especially in children [14]. Small perforations, as well large defects too big for primary repair, and perforations in patients too sick to tolerate an operation are all potential indications for esophageal stent placement at advanced centers. The standard approach for patients with esophageal perforation who become sick and/or have an uncontained perforation is immediate fluid, antimicrobial, and PPI resuscitation followed by emergent full myotomy and closure of mucosa.

The standard surgical approach for perforation is dependent on the site. If the perforation is in the neck, then a left cervical incision is used. If the perforation is in the middle chest, then a right thoracotomy is performed. Finally, if the perforation is in the lower esophagus or gastroesophageal junction, then a left thoracotomy with a possible concomitant laparotomy is performed.

Primary closure of the perforation with two layers of suture after complete myotomy is standard. Wide drainage of the neck and or chest should also be performed with drains and/or chest tubes. The patient must have a way to receive nutrition as the injury heals - either through a nasogastric tube or possibly a gastrostomy tube - prior to leaving the operating room. If the perforation has been present in the cervical esophagus for more than 24 hours, then placing a T-tube through the defect to create a controlled fistula is a reasonable alternative. Similarly, in the chest, if the patient is unstable then debriding devitalized tissue, closing the perforation, and ultimately performing a diversion in the neck with a cervical esophagostomy, and placing a T-tube through the defect to create a controlled fistula could be considered. In an otherwise healthy teenager with prompt recognition of possible perforation this treatment algorithm is unlikely. It should also be noted that Blakemore tubes are a way to temporize esophageal varices and placing one in the setting of a Mallory-Weiss tear or esophageal perforation could make a marginal situation categorically worse.

CONCLUSION

CHS is a pathology of increasing significance to pediatric health care providers due to the rising prevalence of cannabis use in the United States and worldwide. CHS can lead to potentially life-threatening complications, including the development of pneumomediastinum.

Pneumomediastinum can be a harbinger of more sinister pathology such as pneumothorax and esophageal perforation, and there should be a low threshold for providers to consult surgery and manage these patients judiciously.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the staff and personnel of the University of Illinois at Chicago Division of Pediatric Surgery and Department of Surgery for their support of this manuscript and patient care.

Funding

Not applicable

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS

All authors have no competing interests, personal financial interests, funding, employment, or other competing interests.

Authors’ Information

Joseph Geraghty, BS is an eighth-year MD/PhD student who completed his PhD in Neuroscience; Greg Klazura, MD is a global surgery fellow and general surgery resident; Marko Rojnica, MD, is Assistant Professor of Pediatric Surgery; Thomas Sims, MD, is Assistant Professor of Pediatric Surgery; Nathaniel Koo, MD, is Assistant Professor of Pediatric Surgery; Thom E Lobe, MD, is Professor and Chief of the Division of Pediatric Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, United States.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board gave approval for this study. The research protocol number is 2014–0396.

Consent for Publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and the patient’s guardian for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A record of the consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or nonfinancial competing interests

Citation: Greg Klazura, Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome Complicated by Pneumomediastinum: Implications for Pediatric Surgeons. Clin Surg J 5(S13): 6–13.

Availability of Data and Materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen JH, de Moore GM, Heddle R, et al. (2004) Cannabinoid hyperemesis: cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse. Gut 53(11): 1566–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blohm E, Sell P, Neavyn M (2019) Cannabinoid toxicity in pediatrics. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 31(2): 256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorensen CJ, DeSanto K, Borgelt L, et al. (2017) Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: Diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment - A systematic review. Journal of Medical Toxicology 13(1): 71–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simonetto DA, Oxentenko AS, Herman ML, et al. (2012) Cannabinoid hyperemesis: A case series of 98 patients. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 87(2): 114–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habboushe J, Sedor J (2014) Cannabinoid hyperemesis acute renal failure: a common sequela of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 32(6): 690.e1–690.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nourbakhsh M, Miller A, Gofton J, et al. (2019) Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: Reports of fatal cases. Journal of Forensic Science 64(1): 270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vecchio MJ, Binder WD (2021) Pneumomediastinum in a patient with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Rhode Island Medical Journal 104(3): 49–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis W, Frye K, Shah D, et al. (2020) Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome presenting with spontaneous pneumomediastinum. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders 22(2): 19I02509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernández-Ramos I, Parra-Esquivel P, López-Hernández Á, et al. (2019) Spontaneous pneumomediastinum secondary to cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Anales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra 42(2): 227–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen GM (2020) Asymptomatic pneumopericardium in a young male cannabis smoker. Ugeskrift for Laeger 182(12): V12190719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasenoehrl C, Taschler U, Storr M, et al. (2016) The gastrointestinal tract - A central organ of cannabinoid signaling in health and disease. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 28(12): 1765–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lapoint J, Meyer S, Yu CK, et al. (2018) Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: Public health implications and a novel model treatment guideline. The Western Journal of Emerging Medicine 19(2): 380–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forshaw MJ, Khan AZ, Strauss DC, et al. (2007) Vomiting-induced pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema does not always indicate Boerhaave’s syndrome: Report of six cases. Surgery Today 37(10): 888–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mavroudis CD, Kucharczuk JC (2014) Acute management of esophageal perforation. Current Surgery Reports 2: 34. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shields TM, Lightdale JR (2018) Vomiting in children. Pediatrics in Review 39(7): 342–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horwitz B, Krevsky B, Buckman RF Jr, et al. (1993) Endoscopic evaluation of penetrating esophageal injuries. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 88(8): 1249–1253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.