Abstract

COVID-19 represents the newest health disparity faced by African Americans (AA). This study assessed the impact of COVID-19 on barriers and willingness to participate in research among older AAs. An online survey was sent to a nationwide sample of 65- to 85-year-old AAs between January and February 2021. Constant comparison analysis was used to extract themes. A total of 624 older AAs completed the survey. Approximately 40% of participants were willing to engage in virtual or in-person research. Of the individuals who were willing to participate in research, >50% were willing to engage in a spectrum of activities from group discussions to group exercise. Research participation themes related to logistics, technology, pandemic fears, and privacy or security. Older AAs face new research barriers that can be overcome through data use transparency and technology resources. This information can be used to encourage dementia research engagement among older AAs despite the pandemic.

Key Words: African American, COVID-19 pandemic, research participation, health disparities, aging

COVID-19 represents the newest health disparity faced by older African Americans (AA).1 Older AAs are among the highest risk groups for COVID-19 infection, severe COVID-19 outcomes, and COVID-19 mortality, in comparison to non-Hispanic whites due to preexisting health disparities such as a higher risk for developing Alzheimer disease (AD) and other dementias.1,2 Older AAs have long been under-represented in AD research and COVID has exacerbated barriers to research participation. A current notable example is that >75% of participants in ENGAGE/EMERGE trials of aducanumab, the recently FDA-approved AD drug, were white.3 COVID-19 reduced public transportation capacity and convenience, limiting older adults’ ability to travel to research centers.4 AAs express lower confidence in COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness,5 which impacts willingness to engage in face-to-face activities. Older AAs report limited access to, and familiarity with, remote communication technologies (eg, Zoom, FaceTime) thus limiting clinical research tools of choice to overcome novel COVID-19 barriers.6

Currently, few studies document the impact of COVID-19 on willingness to participate in research among older AAs. This study aimed to assess how the pandemic has shaped older AA adults’ barriers related to, and willingness toward, participation in online and in-person research. Gathering and understanding this information is imperative for researchers to adapt recruitment practices that could be applied to AD research during the COVID pandemic.

METHODS

Recruitment

Participants were aged 65 to 85 years and self-identified as AA. Recruitment was conducted by Forthright and Bovitz Inc., to facilitate survey participation nationwide. Individuals were recruited into their database through digital ads, online searches, social media, and mailings. Potential participants were solicited to complete a survey via email or text. Participants earned ~$2.27 for completing the survey and could enter a lottery for $50.

Survey

The survey assessed participant characteristics, the impact of COVID-19 on willingness to participate in research through multiple-choice and open-ended responses. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Pennington Biomedical Research Center and all participants provided informed consent.

RESULTS

Participants

A total of 624 participants completed the survey nationwide between January and February 2021. In all, 54% were female, with a mean age of 69.9 (4.4) years, and 38% of participants reported completing at least 1 to 3 years of college (Supplementary Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/WAD/A398).

Research Participation

Virtual Research Participation

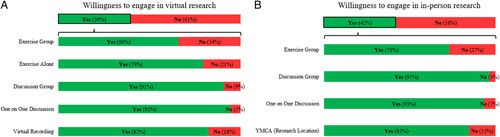

Sixty-one percent of respondents reported they would not participate in research using a videoconferencing program (eg, Zoom, Skype, etc.). Among those who indicated willingness to participate in research via videoconferencing, >60% of individuals indicated willingness to have videoconferences recorded, and to have those sessions include group exercise, solitary exercise, group discussions, and one-on-one discussions (Fig. 1A). Fifty-six percent of individuals who indicated willingness to participate in research via videoconferencing programs indicated they would be comfortable using Zoom, with fewer individuals being comfortable using other videoconferencing programs [ie, FaceTime (21%), Skype (15%), and Facebook Portal (8%)]. Participants were allowed to choose multiple programs.

FIGURE 1.

Research participation willingness: virtual research (A) in-person research (B).

In-Person Research Participation

Fifty-eight percent of individuals reported they were not willing to meet in person with groups as part of a research study despite promises that participants and research staff would follow government guidelines for social distancing, face covering, and hand washing. Of the individuals who reported they were willing to participate in person, >50% were willing to exercise in a group, engage in group discussion, engage in one-on-one discussion, and meet at a Young Men’s Christian Association (Fig. 1B).

Research Participation Barrier Themes

Virtual and In-Person Research Participation

Participants were asked to provide open-ended responses to the questions “Would you be willing to participate in a research study using a videoconferencing program (ie, Zoom, Skype, Facetime, Facebook portal)?” and “Would you be willing to regularly meet in person with groups of other people as part of a research study, as long as government guidelines for social distancing, face covering, and hand washing are followed by other participants and research staff?”. All themes can be found in Table 1A. COVID-19 related themes that emerged included logistics, privacy and security concerns, COVID-19 pandemic fears or restrictions, and underlying health issues. For logistics, responses pointed to problems such as transportation restrictions. Privacy and security concerns included statements about anxieties about research being too invasive into one’s personal life and personal information mistreatment. COVID-19 pandemic fears and restrictions statements ranged from being around people to not wanting to wear a mask. Underlying health issues responses identified medical problems that would impede participation.

TABLE 1.

Themes Related to Virtual and In-Person Research Participation Barriers (A), Research Participation Willingness (B)

| Theme | Definition | Example Quote |

|---|---|---|

| (A) Prior, virtual, and in-person research participation barriers | ||

| Virtual—86% (316 of 369) had substantive elaborations. In-person—79% (277 out of 352) had substantive elaborations | ||

| Logistics | Referring to details that involve some part of the coordination, or structure of the research study that they could not participate in | “Cannot get to most areas. No car.” |

| Inadequate outreach | The lack of engagement with the community about existing research opportunities | “I was never afforded the opportunity.” |

| Lack of interest | Responses about having no interest in participating in research or having no reason to | “Never found a study that interested me enough.” |

| Mistrust in research | Wariness of participating due to possible mistreatment or risk | “Keep (sic) do not like being treated like a guinea pig.” |

| Psychological barriers | Mental obstacle that would impede or prevent research participation | “I have bad teeth and am self-conscious of them.” |

| Privacy and security concerns | Statements describing fear, worry, trust, or safety about the use of personal data or invasion of one’s life | “Do not have full trust in video being used in other ways that I am not aware of.” |

| Lack of familiarity with technology | Referring to skill level or hesitancy toward using technology | “I’m not that computer savvy!” |

| Unreliable or missing equipment | Needed equipment such as a computer that the person does not have or have consistent access to | “Do not have a webcam on my desktop.” |

| COVID-19 pandemic fears or restrictions | Describing fears or recommended rules related to the COVID-19 pandemic that would prevent someone from participating in research | “I do not, per Dr. Fauci, mingle with ANYONE other than immediate members of my household.” |

| Underlying health issues | Referring to a medical problem | “At this point in my life, I’m unable to meet with groups due to my limited ability to walk distances or stand for long periods of time.” |

| (B) Research participation willingness | ||

| Virtual—72% (449 out of 624 participants) had substantive elaborations. In-person—79% (492 out of 624) had substantive elaborations | ||

| Already confident | Statements that indicate that the individual is already comfortable with the prospect of participating in virtual or in-person research and does not need any further assurances | “I am comfortable and confident in meeting in person with groups of other people.” |

| Nothing will change confidence | Statements that indicate an individual is not willing to participate in virtual or in-person research and no further information or assurance will change that decision | “Nothing would make me more comfortable.” |

| Logistics | Involving some part of the coordination, or structure of the research study that they would need to enable research participation | “Just have refreshments.” |

| Welcoming environment | Need for certain details of research participation to make the participant fell comfortable engaging | “Perhaps if I felt that I wouldn’t be laughed at or scorned, because I didn’t look “good enough.”” |

| Security and privacy assurance | Need for personal information to be used properly and protected | “As long it was use (sic) for study and not for personal gain.” |

| Meaningful research for their community | The research that they will be participating in will in some way help or improve life or their friends/family/community/people | “I’m not sure…an assurance this would be for research that would improve the health and well-being of my people.” |

| Health status | Health conditions that the participant needs to have change or handled before participation | “Me feeling better still dealing with covid after effects.” |

| Following COVID-19 health guidelines | Requesting behaviors that reflect health guidelines issued by government agencies such as the CDC to mitigate the infection and spread of COVID-19 | “As long as they wore masks and social distanced and temperatures were taken as a part of entrance requirements. I don’t have a problem. I would also prefer if there was an air purifier in the room.” |

| Pandemic controlled or gone | Fears or recommended rules related to the COVID-19 pandemic that would be removed or lessen to be able to participate in research in-person | “Until I hear we do not need to use mask or worry about social distancing, I would not be comfortable in an in-person group.” |

Themes were only developed from responses to open-ended questions deemed substantive. A substantive response was defined as an answer that provided informative, sufficient, or specific details, beyond one word with no prior context or vague wording, to develop an interpretable theme. Responses considered nonsubstantive included one-word answers such as “Yes,” ambiguous statements like “life has change (sic) forever,” noninformative responses (eg, “No reason”), or answers suggesting misunderstanding of the question like “It is mean?”. Research participation barriers were gathered from the individuals who answered “No” to questions about willingness to participate in virtual and in-person research. Constant comparison analysis was used to evaluate information gathered from responses to open-ended questions. This analysis included the following steps: (1) generation of key words and descriptive categories from open-ended questions; (2) variable groupings based on unifying concepts and categories into overarching themes; and (3) review of variable groupings to ensure consistency and proposed unifying concepts relevance. Key words, descriptive categories, and overarching themes were generated separately by raters and a final codebook was produced through discussion among raters (K.L.G., E.A.P.). Ten percent of open-ended responses were randomly selected and coded separately by both raters using the final codebook to assess inter-rater agreement. The entire data set was then coded by the primary coder (K.L.G.) and checked by a separate rater (E.A.P.) at which time any concerns about coding were discussed and resolved.

Research Participation Willingness Themes

Participants were asked to provide open-ended responses to the questions “What would make you feel more confident in participating in a research study using a videoconferencing program?” and “What would make you feel more confident in meeting in person with groups of other people as part of a research study?”. All themes can be found in Table 1B. COVID-19 related themes that emerged were related to logistics, security, and privacy assurances, health status, following COVID-19 health guidelines, and control or end of the pandemic. Logistics theme responses ranged from needing more information about the study to needing research nearby. Security and privacy assurance theme focused on research institutions being transparent about participant data use. Health status theme related to medical problems that would need to improve or be accommodated to participate. COVID-19 health guidelines theme pointed to standard rules including social distancing, having an air purifier, or COVID-19 testing documentation for all participants. Pandemic control theme statements focused on the overall state of the United States such as relaxing federal mask mandates or the pandemic officially ending.

DISCUSSION

Our findings identified novel pandemic-related barriers that could be applicable to AD and related dementias research, including COVID-19 pandemic fears, greater restrictions on public transportation, and online security and privacy concerns. Participants expressed they would be the most comfortable participating in-person if individuals followed CDC guidelines (eg, wearing a mask, staying 6 feet apart, sanitizing equipment, etc.). Informing participants about institutional policies enforcing health guidelines may facilitate a comfortable environment for this population. Reducing group size to assuage fears, while minimizing the duration of intervention sessions (to minimize mask-wearing time), could help provide social engagement to this at-risk population, particularly considering the COVID-19 pandemic.1 Participants reported they needed to be informed about data protection practices for online research. With COVID-19 increasing the need for virtual research, this suggests a strong need for transparency about personal health information (PHI), for example, how PHI is protected online. Providing technology services to communities, for example, workshops on videoconferencing tools, may help build trust. In short, alleviating these barriers and tailoring AD interventions to this population can increase AA representation.7 These strategies can facilitate online research engagement and may open the door for safely increasing in-person research by building trust in the target community.

An increasing number of dementia prevention interventions are being delivered through telehealth, although few of these programs have specifically targeted AAs.8,9 Around 40% of participants reported willingness to engage in virtual research. While this is less than the majority of the sample, this percentage aligns with previous research.6 Thus, data from the current study suggests virtual research with older AA adults is a viable option. Since some individuals expressed a desire to avoid in-person research participation until the pandemic has subsided, this strategy could be applied immediately. Longer term, researchers will need to find ways to build confidence about the safety of in-person research in this population to overcome anxieties of contracting COVID-19. A balance between participant desires to engage remotely and the scientific need for lab-based measures (ie, magnetic resonance imaging, oral glucose tolerance test, etc.) or a certain kind of social engagement that virtual research may not be able to provide must be found.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to document older AA willingness to participate in research during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data were obtained from a nationwide sample of older AA adults, leading to results that have broad applicability. Themes generated from participant responses provide insights into novel COVID-19-related research barriers and can help researchers generate strategies to overcome these barriers. The study is limited by the fact that the COVID-19 pandemic is a rapidly evolving event, and this survey was deployed for a short period of time during that event. Responses therefore only reflect perspectives evident during that period. Given that AD research under-represents AA, it is important to increase representation of all sub-groups of AA, but a limitation of note is this sample may not be illustrative of the average AA sample based on national data.7,10

CONCLUSION

Older AAs face various barriers to participating in both online and in-person dementia research due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Adapting research modalities to changing barriers is important for reaching the widest range of participants. Ways to overcome barriers include using study data transparently, following COVID-19 health guidelines, and providing participants with needed resources (eg, transportation, Wi-Fi hotspot, etc.). This data will hopefully assist researchers working to facilitate older AA participation in research to fight health disparities and help ensure previous efforts to encourage dementia-related research engagement are not reversed by the pandemic.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the BrightFocus Foundation for their funding of the research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.alzheimerjournal.com.

Contributor Information

Kathryn L. Gwizdala, Email: Kathryn.Gwizdala@pbrc.edu.

Erika A. Pugh, Email: epugh4@lsu.edu.

Leah Carter, Email: leahthetrainer@gmail.com.

Owen T. Carmichael, Email: owen.carmichael@pbrc.edu.

Robert L. Newton, Jr, Email: robert.newton@pbrc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chatters LM, Taylor HO, Taylor RJ. Older black Americans during COVID-19: race and age double jeopardy. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47:855–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miles TP, Froehlich TE, Bogardus ST, Jr, et al. Dementia and race: are there differences between African Americans and Caucasians? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Biogen. Aducanumab (Combined FDA and Applicant PCNS Drugs Advisory Committee Briefing Document). 2020. Available at: https://fda.report/media/143503/PCNS-20201106-CombinedFDBiogenBackgrounder_0.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2022.

- 4. Hu S, Chen P. Who left riding transit? Examining socioeconomic disparities in the impact of COVID-19 on ridership. Transp Res Part Transp Environ. 2021;90:102654. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Olanipekun T, Abe T, Effoe V, et al. Attitudes and perceptions towards coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine acceptance among recovered African American patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2186–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. James DCS, Harville C. eHealth literacy, online help-seeking behavior, and willingness to participate in mHealth chronic disease research among African Americans, Florida, 2014–2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pugh E, Stewart J, Carter L, et al. Beliefs, understanding, and barriers related to dementia research participation among older African Americans. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2022;36:52–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carr LJ, Bartee RT, Dorozynski C, et al. Internet-delivered behavior change program increases physical activity and improves cardiometabolic disease risk factors in sedentary adults: results of a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2008;46:431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shaw CA, Williams KN, Lee RH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a telehealth intervention for in-home dementia care support: findings from the FamTechCare clinical trial. Res Nurs Health. 2021;44:60–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roberts AW, Ogunwole SU, Blakeslee L, et al. The population 65 years and older in the United States: 2016. US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau. 2018. Available at: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2018/acs/acs-38.html .

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.