Abstract

Activated endothelial, immune, and cancer cells prefer glycolysis to obtain energy for their proliferation and migration. Therefore, the blocking of glycolysis can be a promising strategy against cancer and autoimmune disease progression. Inactivation of the glycolytic enzyme PFKFB3 (6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase) suppresses glycolysis level and contributes to decreased proliferation and migration of cancer (tumorigenesis) and endothelial (angiogenesis) cells. Recently, several glycolysis inhibitors have been developed, among them (E)-1-(pyridin-4-yl)-3-(quinolin-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (PFK15) that is considered as one of the most promising. It is known that PFK15 decreases glucose uptake into the endothelial cells and efficiently blocks pathological angiogenesis. However, no study has described sufficiently PFK15 synthesis enabling its general availability. In this paper we provide all necessary details for PFK15 preparation and its advanced characterization. On the other hand, there are known tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., sunitinib), that affect additional molecular targets and efficiently block angiogenesis. From a biological point of view, we have studied and proved the synergistic inhibitory effect by simultaneous administration of glycolysis inhibitor PFK15 and multikinase inhibitor sunitinib on the proliferation and migration of HUVEC. Our results suggest that suppressing the glycolytic activity of endothelial cells in combination with growth factor receptor blocking can be a promising antiangiogenic treatment.

Keywords: PFK15 synthesis, sunitinib L-malate, HUVEC, angiogenesis, synergy

1. Introduction

The alteration of metabolism and increased level of glucose metabolism in activated endothelial cells points to glycolysis as a possible target to inhibit pathological angiogenesis. Endothelial and tumor cells utilize glycolysis to metabolize glucose to lactate instead of oxidative phosphorylation, a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect, which provides an anabolic substrate to cover the demand for rapid cell proliferation and migration. The key regulator of glycolytic flux is the enzyme PFKFB3, which catalyzes the synthesis of F2,6P2 (fructose-2,6-bisphosphate), activating phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK-1), the rate-limiting key enzyme of glycolysis. In recent years, several glycolysis inhibitors have been developed, such as (E)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)-1-(pyridin-4-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (3PO) [1], (E)-1-(pyridin-4-yl)-3-(quinolin-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (PFK15) [2], and (E)-1-(pyridin-4-yl)-3-(7-(trifluoromethyl)quinolin-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (PFK158) [3]. Previously published data demonstrate that glycolysis inhibitors decrease glucose uptake and lactate production, simultaneously reduce the intracellular concentration of F2,6P2, and finally also reduce the level of glycolysis in the cells. Moreover, in our previous study, we confirmed that simultaneous administration of glycolysis inhibitor 3PO and inhibition of the post-receptor signal cascade has a synergic inhibitory effect on the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells [4].

Generally, PFK15 is considered to be a more effective glycolysis inhibitor than 3PO, and its effectivity has been described in several studies [5,6]. In gastric cancer cell lines, PFK15 induced cell cycle arrest by inhibiting the cyclin-CDKs/Rb/E2F-signaling pathway. Moreover, PFK15 suppressed tumor growth by inducing the apoptosis of hepatocellular cancer cells and reducing the tumor vessel diameter [7]. Additionally, previously published data confirmed that chronotherapy represents an additional promising approach to glycolysis inhibition [5,8].

PFK15 is not limited to cancer treatment but can also be related to understanding the activation of immune cells in chronic infection and autoimmune diseases. PFK15 treatment reduces metabolic reprogramming in T-cells in vitro, leading to a delay in the onset of type I diabetes [9]. Therefore, the regulation of glycolysis metabolism in immune cells can be a new possible therapeutic target in autoimmune disease prevention. Additionally, uncontrolled angiogenesis contributes to the microvascular changes in diabetic patients, including the development of diabetic retinopathy [10]. Thus, angiogenesis inhibition is one of the potential targets in the diabetic nephropathy treatment [11].

The effectivity of PFK15 was confirmed in several studies on different cell lines [2,12]; however, its synthesis has not yet been sufficiently described in the literature. The need for PFK15 to be available on a larger scale, e.g., for in vivo assays, motivated us to develop the missing synthesis of this compound. Therefore, we here provide all necessary details for the synthesis of PFK15 and its advanced characterization (e.g., by 2D NMR spectra), which are missing in the literature. To test the predicted antiangiogenic efficacy of PFK15, multiple assays were used. None of them were performed with a combination of PFK15 and sunitinib before. The tests were performed on human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), which provide a useful model system to study prospective antiangiogenic inhibitors or their synergy in combination with differently operating compounds.

2. Results

The antiangiogenic potential (endothelial cells growth, proliferation, and migration) of glycolysis inhibitor PFK15 and multikinase inhibitor sunitinib was tested on HUVEC isolated from human umbilical cords.

2.1. Effect of PFK15 and Sunitinib on HUVEC Growth and Proliferation (IC50)

The IC50 concentration of HUVEC proliferation was determined as 2.6 µM for PFK15 [8] and 1.6 µM for sunitinib (Table 1).

Table 1.

The IC50 values for PFK15 and sunitinib determined on HUVEC.

| IC50 [µM] | |

|---|---|

| PFK15 | 2.6 |

| sunitinib | 1.6 |

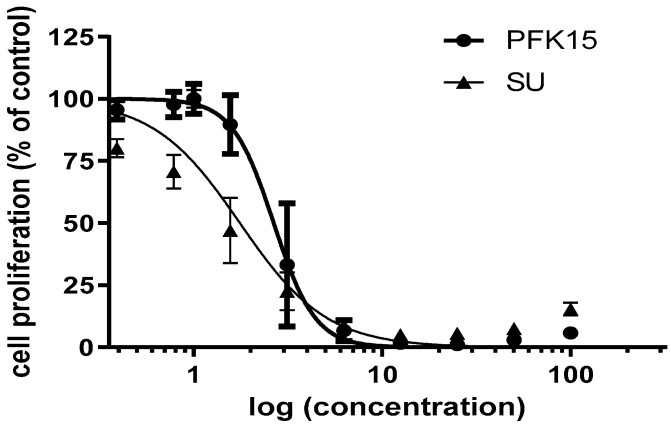

As demonstrated in Figure 1, the HUVEC showed a different shape of response curve for PFK15 and sunitinib, reflecting a higher sensitivity of HUVEC on PFK15 concentration on the one hand, and a higher potential of sunitinib to block cell growth and proliferation at lower concentrations on the other, underlining its multikinase properties.

Figure 1.

HUVEC response to PFK15 ((E)-1-(pyridin-4-yl)-3-(quinolin-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one) and sunitinib (SU) treatment after 72 h. Concentration values on the x-axis are on a logarithmic scale and are in µM.

2.2. Effect of PFK15 and Sunitinib on HUVEC Migration (Wound Healing Assay)

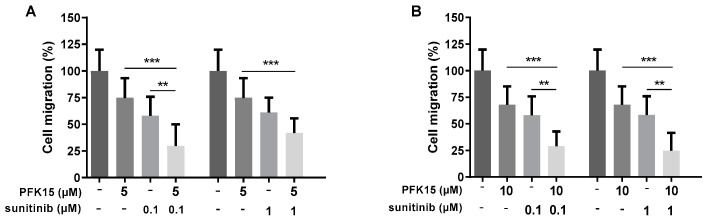

Cell migration was quantified after the cell treatment with PFK15 and sunitinib alone or in combination. The combined action of PFK15 (at 5 or 10 µM) with sunitinib (at 0.1 or 1 µM) more efficiently inhibited HUVEC migration compared to PFK15 or sunitinib alone. Simultaneous administration of PFK15 and sunitinib at specific concentrations clearly showed a synergistic effect on the inhibition of HUVEC migration (Figure 2; representative photos illustrating cell migration are available in Supplementary Material, Figure S8).

Figure 2.

Evaluation of the administration of PFK15 ((E)-1-(pyridin-4-yl)-3-(quinolin-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one) and sunitinib, alone or combined, on HUVEC migration. HUVEC were treated with PFK15 at 5 (A) and 10 µM (B) and sunitinib at 0.1 and 1 µM for 8 h and changes in cell migration were analyzed. Statistical differences among groups were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in quadruplicate (** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

2.3. Effect of PFK15 and Sunitinib on HUVEC Proliferation

In the next experiments, we studied changes in HUVEC proliferation in the presence of PFK15 and sunitinib in order to confirm their inhibitory and synergic effect. In the preliminary experiment, we applied PFK15 at concentrations of 5 and 10 µM and sunitinib at 0.1 and 1 µM (similarly to the previous wound healing assay), alone or in combination, but in this case, the effects of inhibitors applied alone were too strong to see any combined effects (see the pictures in Supplementary Materials, Figure S9).

Therefore, in the next experiments we selected lower concentrations of PFK15 (2, 3, and 4 µM) and sunitinib (4, 5, and 6 µM) alone or in combinations. In these trials, both PFK15 and sunitinib alone reduced cell proliferation compared to the control. Moreover, simultaneous administration of both inhibitors at specific concentrations showed a synergistic effect on cell proliferation compared to application of the inhibitors alone. PFK15 at 3 and 4 µM in combination with sunitinib at 4, 5, and 6 µM most efficiently inhibited HUVEC proliferation (Figure 3B,C).

Figure 3.

Effect of PFK15 ((E)-1-(pyridin-4-yl)-3-(quinolin-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one) and sunitinib administered alone or in combination on HUVEC proliferation. HUVEC were treated with PFK15 at 2 (A), 3 (B), or 4 (C) µM and sunitinib at 4, 5, or 6 µM for 72 h. Changes in cell proliferation were recorded. Statistical differences among groups were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

3. Discussion

The limited efficacy of the 1st generation of antiangiogenic therapy led to the development of selective PFKFB3 inhibitors that showed potential activity against the key glycolysis enzyme in different cell types, as well as in various animal models [2,5,6]. Recently, several glycolytic inhibitors were identified; among them, PFK15 showed important antitumor efficiency. However, until now, no study has described the synthesis of this generally available glycolytic inhibitor in detail. Therefore, we performed an efficient synthesis of PFK15 and confirmed its efficiency on activated HUVEC cells. Additionally, we observed more effective inhibition of HUVEC proliferation and migration using a combination of glycolysis inhibitor PFK15 with multikinase inhibitor sunitinib, targeting different biological pathways and explaining the synergic effect of their inhibition.

3PO is one of the first synthesized blockers of glycolysis [1], and its effective synthesis has already been described by our research group [13]. Although its antiangiogenic potential was described in several studies, the concentration at which 3PO is effective appears to be relatively high. Moreover, this high concentration is difficult to achieve in clinical studies because of the poor solubility of 3PO in water [14]. Therefore, other inhibitors of PFKFB3 have been developed. Substitution of the pyridine-4-yl ring in the inhibitor 3PO for the quinoline-2-yl group results in a more powerful inhibitor PFK15, which is also characterized by higher selectivity for the enzyme PFKFB3 [2]. The antitumor effect of PFK15 was compared with the effect of chemotherapy drugs that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of human cancer (e.g., irinotecan, temozolomide, and gemcitabine). The PFK15 inhibitor suppressed pancreatic and colon adenocarcinoma growth, similarly to gemcitabine and irinotecan, while the effect of PFK15 on glioblastoma growth was lower compared to the chemotherapeutic agent temozolomide [2]. The activity of the PFKFB3 enzyme can be regulated by several factors, including the AMPK signaling pathway, which can function as an upstream of the PFKFB3 regulator. It was confirmed that PFK15 is able to inhibit AMPK and Akt-mTORC1 signaling in colorectal cancer cells [15], and thereby reduce tumor cell viability.

Limitations related to low inhibitor water solubility may be solved using nanocarriers or by chemical modification of the inhibitor structure [14]. Moreover, the low cytotoxic effect of glycolysis inhibitors on healthy cells [6], confirmed in several studies [16,17], suggests that the combination of a glycolysis inhibitor with other chemotherapy agents (e.g., multikinase inhibitor or cytostatic drug) may be an important strategy in advanced cancer treatment.

The additive inhibitory effect of the simultaneous administration of 3PO and sunitinib on angiogenesis was demonstrated under in vivo conditions on a zebrafish embryo model, in which the formation of intersomitic vessels was evaluated [16]. Our previously published data [4] also confirmed that cells treated with the glycolysis inhibitor 3PO at 10 µM and sunitinib at 1 µM, as well as 20 µM 3PO in combination with sunitinib in a concentration range of 0.1–10 µM, significantly reduced cell proliferation compared to the inhibitors applied alone.

We determined the IC50 value for both PFK15 and sunitinib (Figure 1) and have observed a significant decrease of HUVECs migration and proliferation after cell treatment with PFK15 and sunitinib (Figure 2 and Figure 3). To confirm the synergic effect of the combined administration of both inhibitors, PFK15 and sunitinib were applied at different concentrations. PFK15 applied at 3 and 4 µM and sunitinib at 4, 5, and 6 µM more efficiently lowered cell proliferation compared to the inhibitors alone (Figure 3).

In addition to the simultaneous inhibition of the dominant metabolic pathway (e.g., by PFK15) and the activity on human kinase receptors (e.g., by sunitinib), there are also other possibilities to reduce cell metabolism and other physiological processes in cells. The inhibition of glycolysis in tumor cells may lead to the cells showing the increased preference for another metabolic pathway for ATP production, e.g., oxidative phosphorylation. The simultaneous inhibition of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation using metformin and 2-DG (2-deoxyglucose) showed an additive effect compared to the application of these inhibitors alone [18]. Another possibility is the use of phenformin, which was clinically tested in the treatment of diabetes, and oxamate, which acts as an inhibitor of lactate dehydrogenase enzyme activity. A synergistic effect was observed in the combined effect of phenformin and oxamate, where a significant antitumor effect was confirmed by simultaneous inhibition of complex I in mitochondria and LDH activity in the cytosol of the cells [17].

We used the IC50 value, which expresses the concentration of tested substance causing inhibition of cell growth by 50%, to determine the toxicity of sunitinib and the glycolysis blocker PFK15. The measured values show that HUVEC are more sensitive to sunitinib compared to PFK15. Similar results were obtained with bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAEC) at the IC50 concentration of 2.2 µM of sunitinib and 1.6 µM for HUVEC, respectively (Table 1). This reflects the multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitory action of sunitinib compared with PFK15. The multikinase inhibitor sunitinib is used in the clinical treatment of several types of cancer and its effect has been documented by many published data [19,20]. The mechanism of action of sunitinib includes several signaling pathways, possessing receptor as well as non-receptor tyrosine kinases (e.g., VEGF-R, PDGF-R, CSFR, c-KIT, etc.) [21].

Consistent with our results, the different effectivity of 3PO and PFK15 was shown in a model of an immortalized human T-lymphocyte line (Jurkat cells) and non-small cell lung carcinoma cells (H522) after 48 h of treatment, with PFK15 having a more pronounced effect than 3PO [2]. Previously published data suggest that the effect of these inhibitors varies significantly depending on the cell type and origin (human vs. animal cells), degree of differentiation, inhibitor concentrations, and time of incubation [1,2,12,22]. Our previous study showed that PFK15 reduced HUVEC and colorectal adenocarcinoma DLD1 cell proliferation at the same level, indicating that the same molecular targets are affected by this treatment [8]. However, compared to an animal model of BAEC, the effectivity of PFK15 was quite different, as the IC50 value for BAEC was determined to be 7.4 µM. 3PO showed similar results to PFK15, with an IC50 value of 6.9 µM, indicating that the effectivity of glycolysis inhibition depends on several additional factors.

The simultaneous administration of PFK15 and the chemotherapeutic drug paclitaxel (PTX) showed a synergistic effect and may be an effective strategy in cancer treatment. Both drugs were carried to the cells by solid lipid nanoparticles encapsulated in membranes formulated by fusing breast cancer cell and activated fibroblast membranes [23]. The cytotoxic effect of PTX/PFK15 in solid lipid nanoparticles was confirmed in vitro, as well as in vivo. In tumor-bearing mice, the monotherapy of nanoparticles with PTX or PFK15 did not induce a significant therapeutic effect; however, mice treated with PTX/PFK15 nanoparticles showed enhanced tumor inhibition. These data suggest that the dual targeting of cancer cell and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) is more effective, as the energy supply from CAF to cancer cells is blocked by glycolysis inhibition [23].

In summary, we developed the missing synthesis of PFK15 with the aim of making this glycolysis inhibitor broadly available in large amounts for in vitro and in vivo biological studies. Additionally, PFK15 was also thoroughly physicochemically characterized. From a biological point of view, we proved sufficient sensitivity of HUVEC proliferation and migration to both inhibitors alone. More importantly, we have proven the synergistic effect on HUVEC proliferation and migration with the combination of PFK15 and sunitinib at their appropriate concentrations. In future research, the pharmacokinetic properties of PFK15 should be improved by developing more biologically active form of inhibitor, which can be tested either alone and/or in combination with other clinically used drugs in different pathophysiological conditions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemistry

4.1.1. General Conditions

The starting chemicals for syntheses were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Other chemicals and solvents were purchased from local commercial sources and were of analytical grade quality. The melting point was measured by a digital melting point apparatus Barnstead Electrothermal IA9200 and is uncorrected. 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Gemini (600 and 150 MHz, respectively); chemical shifts are given in parts per million (ppm); tetramethylsilane was used as an internal standard; and DMSO-d6 was used as the solvent. Infrared (IR) spectra were acquired by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) attenuated total reflectance REACT IR 1000 (ASI Applied Systems) with a diamond probe and MTS detector. Mass spectra were performed on a liquid chromatography mass spectrometer LC-MS using an Agilent Technologies 1200 Series equipped with mass spectrometer Agilent Technologies 6100 Quadrupole LC-MS. The course of the reactions was followed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) (Merck Silica gel 60 F254), and a UV lamp (254 nm), and iodine vapors were used for visualization of the TLC spots.

4.1.2. Synthetic Pathway to (E)-1-(Pyridin-4-yl)-3-(quinolin-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (PFK15)

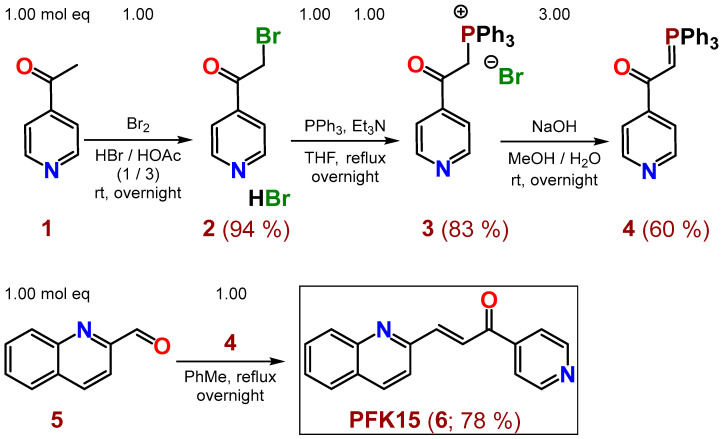

Inhibitor PFK15 (6) was prepared in four reaction steps, according to Scheme 1. After bromination of commercially available 4-acetylpyridine (1) with bromine in a mixture of conc. acids HBr/HOAc (1/3, respectively) at room temperature (rt), the hydrobromide of 2-bromo-1-(pyridin-4-yl)ethan-1-one (2) was obtained in 94% yield. Salt 2 was converted to compound 3 in 83% yield by PPh3 and Et3N in THF under reflux overnight. Compound 4 was prepared from salt 3 in 60% yield by NaOH in a mixture of MeOH/H2O at rt overnight. The desired PFK15 inhibitor (6) was finally synthetized from commercially available 2-quinolinecarboxaldehyde (5) and the previously prepared compound 4 in refluxing toluene overnight, with 78% yield (or 36.5% overall yield via 4 steps). PFK15 was purified by crystallization from EtOH or ethyl acetate (EA).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of inhibitor PFK15 (6), starting from commercially available 1-(pyridin-4-yl)ethan-1-one (1) and 2-quinolinecarboxaldehyde (5).

4.1.3. Synthesis of 2-Bromo-1-(pyridin-4-yl)ethan-1-one hydrobromide (2)

A solution of 32.0 g (264 mmol, 1.00 mol eq) 1-(pyridin-4-yl)ethan-1-one (1) in 250 mL glacial acetic acid (100%) was cooled in an ice bath, and 150 mL conc. HBr (48 w/w %) was carefully added. Subsequently, a solution of 42.2 g (264 mmol, 1.00 mol eq) Br2 in 20 mL glacial acetic acid was added dropwise to the reaction mixture. The reaction was stirred overnight at rt while a white precipitate formed. Afterwards, 250 mL Et2O was added, and the mixture was stirred for 30 min at rt and filtered. The obtained solid material was washed with 150 mL Et2O, dried to yield 70.0 g (249 mmol, 94%) of 2 in the form of a white solid powder. Salt 2 was used in the next step without further purification. Its m.p., 1H-NMR [24] and MS [25] spectra are described in the literature.

4.1.4. Synthesis of (2-Oxo-2-(pyridin-4-yl)ethyl)triphenylphosphonium bromide (3)

First of all, 65.4 g (249 mmol, 1.00 mol eq) PPh3 and 34.7 mL (25.2 g, 249 mmol, 1.00 mol eq) Et3N were sequentially added to a solution of 70.0 g (249 mmol, 1.00 mol eq) 2 in 400 mL of THF. The reaction mixture was refluxed overnight while an orange precipitate formed. After cooling the mixture to rt, the solid material was filtered off, washed with 150 mL Et2O, and dried under reduced pressure to yield 95.9 g (207 mmol, 83%) of an orange product 3, which was used without further purification in the next reaction.

4.1.5. Synthesis of 1-(Pyridin-4-yl)-2-(triphenyl-λ5-phosphanylidene)ethan-1-one (4)

Within 30 min, 10.6 g (265 mmol, 3.00 mol eq) NaOH in 303 mL H2O was added to a solution of 40.9 g (88.5 mmol, 1.00 mol eq) 3 in a mixture of solvents (82 mL of MeOH and 151 mL of H2O). The mixture was stirred overnight at rt. The brown precipitate was filtered off, and washed sequentially with 100 mL H2O and 100 mL Et2O and dried under reduced pressure. A yield of 20.11 g (52.7 mmol, 60%) of 4 was obtained and used without further purification in the next step. Its m.p., 1H-NMR, and IR spectra are described in the literature [26].

4.1.6. Synthesis of (E)-1-(Pyridin-4-yl)-3-(quinolin-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (6, PFK15)

First of all, 8.86 g (23.2 mmol, 1.00 mol eq) of a previously prepared compound 4 was added to a solution of 3.65 g (23.2 mmol, 1.00 mol eq) 2-quinolinecarboxaldehyde (5) in 250 mL toluene. The reaction mixture was stirred and refluxed overnight while a precipitated material appeared in the reaction. The mixture was cooled down and volatile parts were evaporated by rotary vacuum evaporator (RVE). The obtained crude reaction product (4.71 g, 78%) was crystallized from EtOH, yielding 2.54 g (9.76 mmol, 42%) of the required inhibitor 6 (PFK15), possessing an HPLC-UV (254 nm) purity of 99.2%. The synthesis and other characteristics of compound 6 are not yet described in the literature.

M.p.: 159.4–160.6 °C [EtOH].

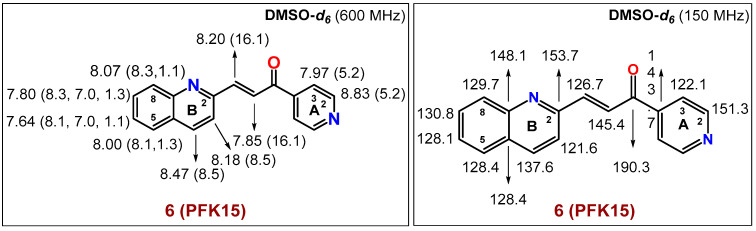

The spectral diagrams (1H- and 13C-NMR) of 6 (PFK15) are based on 1D- and 2D-NMR techniques and are shown in Figure 4 below (see also the Supplementary Material to this paper).

Figure 4.

The spectral diagrams describing 1H- and 13C-NMR characteristics of 6 (PFK15).

1H-NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.83 (d, 2H, J(A2,A3) = 5.2 Hz, 2 × H-CA(2)), 8.47 (d, 1H, J(B3,B4) = 8.5 Hz, H-CB(4)), 8.20 (d, 1H, J(CH=CH) = 16.1 Hz, -CH=CH-C=O), 8.18 (d, 1H, J(B3,B4) = 8.5 Hz, H-CB(3)), 8.07 (dd, 1H, J(B7,B8) = 8.3 Hz, J(B6,B8) = 1.1 Hz, H-CB(8)), 8.00 (dd, 1H, J(B5,B6) = 8.1 Hz, J(B5,B7) = 1.3 Hz, H-CB(5)), 7.97 (d, 2H, J(A2,A3) = 5.2 Hz, 2 × H-CA(3)), 7.85 (d, 1H, J(CH=CH) = 16.1 Hz, -CH=CH-C=O), 7.80 (ddd, 1H, J(B7,B8) = 8.3 Hz, J(B6,B7) = 7.00 Hz, J(B5,B7) = 1.3 Hz, H-CB(7)), 7.64 (ddd, 1H, J(B5,B6) = 8.1 Hz, J(B6,B7) = 7.00 Hz, J(B6,B8) = 1.1 Hz, H-CB(6)).

13C-NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 190.3 (-C=O), 153.7 CB(2), 151.3 (2 × CA(2)), 148.1 CB(9), 145.4 (-CH=CH-C=O), 143.7 CA(4), 137.6 CB(4), 130.8 CB(7), 129.7 CB(8), 128.4 CB(10), 128.4 CB(5), 128.1 CB(6), 126.7 (-CH=CH-C=O), 122.1 (2 × CA(3)), 121.6 CB(3).

FT IR (solid sample, cm−1): 3051 (m), 2111 (w), 2054 (w), 1930 (w), 1858 (w), 1661 (m), 1589 (s), 1551 (m), 1502 (m), 1433 (w), 1408 (m), 1377 (w), 1351 (m), 1306 (m), 1286 (m), 1255 (m), 1209 (s), 1149 (m), 1117 (m), 1060 (w), 1034 (s), 980 (s), 951 (m), 897 (m), 872 (m), 842 (m), 820 (s), 877 (s), 770 (s), 738 (s), 698 (s), 655 (s), 554 (m), 524 (m), 495 (m), 477 (m), 448 (m), 428 (m).

MS of 6 (PFK15, calculated FWexact = 260.09; ESI/positive mode: found [M+H]+ = 261.1).

Elemental Analysis: Calculated for C17H12N2O (260.30): C, 78.44; H, 4.65; N, 10.76. Found: C, 78.12; H, 4.38; N, 10.99.

The spectra and detailed spectral characteristics (1D-, 2D-NMR: NOESY, HSQC, HMBC, IR and MS) for PFK15 (6), not yet published in the literature, are presented in the Supplementary Material to this paper (Figures S1–S7).

4.2. Biology

4.2.1. Cell Culture and Cultivation

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were isolated from fresh umbilical cords, as described previously [4], and cultured in endothelial cell growth medium (ECGM; PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany) supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Biosera, Nuaillé, France). Cells were incubated in a humidified incubator (Heal Force Bio-meditech, Qingdao, China) at standard conditions (in 5% CO2 at 37 °C). Cells were used between passages 1 and 6.

4.2.2. Drug Preparation

Stock solutions of the multikinase inhibitor sunitinib L-malate (Pfizer, New York, NY, USA) (abbreviated to sunitinib or SU in the text for simplification) and the glucose metabolism inhibitor (E)-1-(pyridin-4-yl)-3-(quinolin-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (PFK15) were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at a concentration of 10 mM. The stock solutions were subsequently diluted in an appropriate concentration in ECGM (and finally in test solutions containing 1% DMSO) for the in vitro experiments. Sunitinib was obtained as a gift from a pharmaceutical company (Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA). The synthesis and exact structure assignments of PFK15 were performed as described above.

4.2.3. IC50 Evaluation

Cells were seeded in a 96-well plate with serial dilutions of PFK15 and sunitinib (starting at 100 µM solution containing 1% DMSO) at a density of 3 × 103 cells/well. The MTS assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, as previously described [8]. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value was calculated using Graph Pad Prism 6 software (Graph Pad, San Diego, CA, USA).

4.2.4. Cell Proliferation Assay

The MTS assay is generally used for the quantification of cell proliferation, viability, or cytotoxicity. Cell proliferation was determined by colorimetric MTS assay, according to the manufacturer´s instructions. Briefly, cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 3 × 103 cells/well and incubated with serial dilutions of PFK15 and sunitinib for 3 days. After 3 days, 10 µL of yellow MTS (5 mg/mL) (Promega, Madison, WI, USA, CAS: 138169-43-4) was added to each well and cells were incubated for 2–3 h at 37 °C. The absorbances were measured at a wavelength of 490 nm (green color). All determinations were performed in quadruplicate, with three independent experiments.

4.2.5. Migration Assay (Wound Healing Assay)

Cells were seeded in 24-well plates coated with 1.5% gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well (HUVEC). After reaching a confluent monolayer the medium was replaced with a starvation medium (ECGM supplemented with 2% FBS) and cells were incubated for a further 17 h. The confluent cell monolayer was wounded using pipet tips and washed twice with PBS. Subsequently, cells were treated with different doses of inhibitors diluted in ECGM medium. The migration of HUVEC was observed with an Olympus IMT2 inverted optical microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and recorded by a Moticam 1000 camera system (Motic Incorporation, Hong Kong) at 0 h and 8 h after treatment. Changes in cell migration were evaluated using the software Motic Images Plus 2.0 PL (Motic Incorporation, Hong Kong).

4.3. Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as a mean ± SEM. Each value represents the average of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using STATISTICA 7.0 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA) and GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Statistical differences among groups were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. The value p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we described the synthesis of the glycolysis inhibitor PFK15 in detail. Our results confirmed the effectivity of PFK15 in combination with sunitinib. Sunitinib is an approved drug with therapeutic applications against tumor growth and tumor angiogenesis. The glycolysis inhibitor PFK15 reduces glucose uptake and causes starvation of activated endothelial and tumor cells. Both tumor and activated endothelial cells are dependent on a high influx of glucose as an important source of energy and building blocks. Therefore, the synergistic effect of the above inhibitors to block different biological targets and mechanisms of action on HUVEC-based angiogenesis is promising from a therapeutical point of view.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the pharmaceutical company Pfizer Inc., USA, for supporting us with sunitinib L-malate that was obtained as a gift.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms232214295/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z., R.M., M.Z., M.M., G.A. and A.B.; methodology, J.Z., R.M., M.M., G.A. and A.B.; formal analysis, J.Z., R.M. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z., A.B. and M.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.Z., A.B. and M.Z.; visualization, J.Z. and A.B.; supervision, M.Z. and A.B.; funding acquisition, M.Z. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grants APVV-17-0178 and by the Operation Program of Integrated Infrastructure for the Project, Advancing University Capacity and Competence in Research, Development and Innovation, ITMS2014+: 313021X329, co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, VEGA 1/0670/18 and Biomagi, Ltd.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Clem B., Telang S., Clem A., Yalcin A., Meier J., Simmons A., Rasku M.A., Arumugam S., Dean W.L., Eaton J., et al. Small-Molecule Inhibition of 6-Phosphofructo-2-Kinase Activity Suppresses Glycolytic Flux and Tumor Growth. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008;7:110–120. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clem B.F., O’neal J., Tapolsky G., Clem A.L., Imbert-Fernandez Y., Ii D.A.K., Klarer A.C., Redman R., Miller D.M., Trent J.O., et al. Targeting 6-Phosphofructo-2-Kinase (PFKFB3) as a Therapeutic Strategy against Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013;12:1461–1470. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mondal S., Roy D., Sarkar Bhattacharya S., Jin L., Jung D., Zhang S., Kalogera E., Staub J., Wang Y., Xuyang W., et al. Therapeutic Targeting of PFKFB3 with a Novel Glycolytic Inhibitor PFK158 Promotes Lipophagy and Chemosensitivity in Gynecologic Cancers. Int. J. Cancer. 2019;144:178–189. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horváthová J., Moravčík R., Boháč A., Zeman M. Synergic Effects of Inhibition of Glycolysis and Multikinase Receptor Signalling on Proliferation and Migration of Endothelial Cells. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2019;38:157–163. doi: 10.4149/gpb_2018047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen L., Zhao J., Tang Q., Li H., Zhang C., Yu R., Zhao Y., Huo Y., Wu C. PFKFB3 Control of Cancer Growth by Responding to Circadian Clock Outputs. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24324. doi: 10.1038/srep24324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H.M., Yang J.G., Liu Z.J., Wang W.M., Yu Z.L., Ren J.G., Chen G., Zhang W., Jia J. Blockage of Glycolysis by Targeting PFKFB3 Suppresses Tumor Growth and Metastasis in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;36:7. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0481-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsumoto K., Noda T., Kobayashi S., Sakano Y., Yokota Y., Iwagami Y., Yamada D., Tomimaru Y., Akita H., Gotoh K., et al. Inhibition of Glycolytic Activator PFKFB3 Suppresses Tumor Growth and Induces Tumor Vessel Normalization in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2021;500:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horváthová J., Moravčík R., Matúšková M., Šišovský V., Boháč A., Zeman M. Inhibition of Glycolysis Suppresses Cell Proliferation and Tumor Progression in Vivo: Perspectives for Chronotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:4390. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martins C.P., New L.A., O’Connor E.C., Previte D.M., Cargill K.R., Tse I.L., Sims-Lucas S., Piganelli J.D. Glycolysis Inhibition Induces Functional and Metabolic Exhaustion of CD4+ T Cells in Type 1 Diabetes. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:669456. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.669456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng R., Ma J.-X. Angiogenesis in Diabetes and Obesity. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2015;16:67–75. doi: 10.1007/s11154-015-9310-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Min J., Zeng T., Roux M., Lazar D., Chen L., Tudzarova S. The Role of HIF1α-PFKFB3 Pathway in Diabetic Retinopathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021;106:2505. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu W., Ye L., Zhang J., Yu P., Wang H., Ye Z., Tian J. PFK15, a Small Molecule Inhibitor of PFKFB3, Induces Cell Cycle Arrest, Apoptosis and Inhibits Invasion in Gastric Cancer. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0163768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murár M., Horvathová J., Moravčík R., Addová G., Zeman M., Boháč A. Synthesis of Glycolysis Inhibitor (E)-3-(Pyridin-3-Yl)-1-(Pyridin-4-Yl)Prop-2-En-1-One (3PO) and Its Inhibition of HUVEC Proliferation Alone or in a Combination with the Multi-Kinase Inhibitor Sunitinib. Chem. Pap. 2018;72:2979–2985. doi: 10.1007/s11696-018-0548-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotowski K., Supplitt S., Wiczew D., Przystupski D., Bartosik W., Saczko J., Rossowska J., Drag-Zalesińska M., Michel O., Kulbacka J. 3PO as a Selective Inhibitor of 6-Phosphofructo- 2-Kinase/Fructose-2,6-Biphosphatase 3 in A375 Human Melanoma Cells. Anticancer Res. 2020;40:2613–2625. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan S., Yuan D., Li Q., Li S., Zhang F. AICAR Enhances the Cytotoxicity of PFKFB3 Inhibitor in an AMPK Signaling-Independent Manner in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Med. Oncol. 2021;39:10. doi: 10.1007/s12032-021-01601-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schoors S., de Bock K., Cantelmo A.R., Georgiadou M., Ghesquière B., Cauwenberghs S., Kuchnio A., Wong B.W., Quaegebeur A., Goveia J., et al. Partial and Transient Reduction of Glycolysis by PFKFB3 Blockade Reduces Pathological Angiogenesis. Cell Metab. 2014;19:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miskimins W.K., Ahn H.J., Kim J.Y., Ryu S., Jung Y.S., Choi J.Y. Synergistic Anti-Cancer Effect of Phenformin and Oxamate. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:85576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahra I.B., Laurent K., Giuliano S., Larbret F., Ponzio G., Gounon P., le Marchand-Brustel Y., Giorgetti-Peraldi S., Cormont M., Bertolotto C., et al. Targeting Cancer Cell Metabolism: The Combination of Metformin and 2-Deoxyglucose Induces P53-Dependent Apoptosis in Prostate Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2465–2475. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu J., Wang W., Liu C., Li M., Nice E., Xu H. Retraction Note: Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Sunitinib and Integrin Antagonist Peptide HM-3 Show Similar Lipid Raft Dependent Biphasic Regulation of Tumor Angiogenesis and Metastasis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;39:381. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-1538-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pla A.F., Brossa A., Bernardini M., Genova T., Grolez G., Villers A., Leroy X., Prevarskaya N., Gkika D., Bussolati B. Differential Sensitivity of Prostate Tumor Derived Endothelial Cells to Sorafenib and Sunitinib. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:939. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.le Tourneau C., Raymond E., Faivre S. Sunitinib: A Novel Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor. A Brief Review of Its Therapeutic Potential in the Treatment of Renal Carcinoma and Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GIST) Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2007;3:341. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.2007.3.2.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Bock K., Georgiadou M., Carmeliet P. Role of Endothelial Cell Metabolism in Vessel Sprouting. Cell Metab. 2013;18:634–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zang S., Huang K., Li J., Ren K., Li T., He X., Tao Y., He J., Dong Z., Li M., et al. Metabolic Reprogramming by Dual-Targeting Biomimetic Nanoparticles for Enhanced Tumor Chemo-Immunotherapy. Acta Biomater. 2022;148:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turcotte S., Chan D.A., Sutphin P.D., Giaccia A.J., Hay M.P., Denny W.A., Bonnet M.M. Heteroaryl Compounds, Compositions, and Methods of Use in Cancer Treatment. WO2009114552A1. U.S. Patent. 2009 September 19;

- 25.Newcom J.S., Spear K.L. P2x4 Receptor Modulating Compounds and Methods of Use Thereof. Pain. 2015;161:1425. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Portevin B., Tordjman C., Pastoureau P., Bonnet J., de Nanteuil G. 1,3-Diaryl-4,5,6,7-Tetrahydro-2H-Isoindole Derivatives: A New Series of Potent and Selective COX-2 Inhibitors in Which a Sulfonyl Group Is Not a Structural Requisite. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:4582–4593. doi: 10.1021/jm990965x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.