Abstract

We have analyzed oral tolerance of microbial antigens in an experimental model in which mice are treated orally with a single small dose of soluble antigen and challenged systemically with the antigen in complete Freund's adjuvant. We found that, while oral administration of sonicated extracts of either Leishmania major, Leishmania donovani, or Staphylococcus aureus was tolerogenic, as was administration of the nominal antigen ovalbumin or conalbumin, oral administration of Escherichia coli or Salmonella typhimurium sonicated extract was not. Since E. coli is an enteric commensal that colonizes the intestine soon after birth, these data suggested that lack of demonstrable oral tolerance may be related to the frequency of oral exposure to an antigen. In support of this, we found that multiple oral doses of ovalbumin or S. aureus or L. donovani antigens did not increase systemic hyporesponsiveness beyond that achieved with a single oral dose. We have also tested the ability of mice fed with sonicates of the tolerogenic S. aureus or the nontolerogenic S. typhimurium to clear a subsequent systemic infection with the homologous bacteria and found that, while clearance of S. aureus was unaffected by prior feeding, clearance of S. typhimurium was actually enhanced. The data suggest that frequent oral antigenic exposure may eventually lead to induction of systemic immunity in tolerant mice.

The gastrointestinal tract, lined by a layer of simple epithelium, is prey to constant assault from ingested parasites. Protective immune responses are initiated predominantly in Peyer's patches, the organized lymphoid tissue present at discrete intervals along the length of the small and large intestine, and for gastrointestinal immunity to be effective, immune cells generated here have to seed, via circulation, the entire epithelial layer and the lamina propria of the gut. A further layer of complexity is added to gastrointestinal immunity by the fact that absorption of nutrients also takes place at this site, so that a balance has to be struck between the generation of protective antimicrobial immune responses and the nongeneration of harmful immune responses against food antigens. It is known that oral administration of soluble antigens or inert particulate antigens usually leads to antigen-specific systemic hyporesponsiveness. The phenomenon, called oral tolerance, was described several years ago in models of anaphylaxis and experimental drug allergy (4, 46) and, in more recent years, as systemic hyporesponsiveness to a variety of antigens, often following antigen-specific T-cell activation (13) and in the face of a good mucosal immunoglobulin A (IgA) response. The readouts used have been as varied as delayed-type hypersensitivity, passive cutaneous anaphylaxis, serum IgG and IgE levels, enumeration of plaque-forming cells, cytotoxic allograft reactions, T-cell stimulation, induction of autoimmune disease, and measurement of systemic antigen-specific cells (1–3, 7, 9, 16–19, 22, 29, 34, 35, 42, 44).

If oral tolerance is a generalized phenomenon and applicable to all antigens, it raises the possibility that oral exposure to microbial antigens may immunocompromise the host by dampening the generation of subsequent antimicrobial systemic immune responses against the parasite. We have explored this possibility by looking at the ability of a single oral application of microbial sonicates to induce systemic hyporesponsiveness in fed mice, by using in vitro T-cell stimulation assays and in vivo bacterial clearance assays as readouts. We report here our findings on oral tolerance induced by a single, low-dose, oral application of sonicates obtained from enteric and nonenteric microorganisms. We also report the effects of administering multiple oral doses of antigens on oral tolerance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

Escherichia coli HB101 (American Type Culture Collection) and Stm 754, a clinical isolate of Salmonella typhimurium (39), are routinely maintained in the laboratory. Staphylococcus aureus was a gift of A. Kapil, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. Leishmania donovani was a gift of K. P. Chang, Chicago Medical School, and Leishmania major was a gift of D. Sarkar, Indian Institute of Chemical Biology, Calcutta, India. Bacterial stocks were stored in glycerol broth at −70°C, and a fresh aliquot was plated out either on salmonella-shigella agar (SS agar; Hi Media, Bombay, India) in the case of S. typhimurium or on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar (Hi Media) in the case of S. aureus and E. coli, for each immunization. Leishmania promastigotes were propagated in tissue culture flasks (Falcon; Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) at 30°C in M199 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Bet Haemek, Israel), 100 μg of penicillin per ml, and 100 U of streptomycin (Hi Media) per ml. For preparation of bacterial sonicates, overnight cultures of bacteria in LB broth cultures were spun down, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and killed by treating the cells in a boiling water bath for 45 min. The suspension was sonicated for 15 min in phosphate-buffered saline containing 10 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, Mo.) as a protease inhibitor. The sonicates were spun at 100,000 × g for 60 min to remove insoluble debris and to decrease lipopolysaccharide levels, and the supernatants were filtered and used as soluble antigen for in vitro assays. For preparation of leishmanial antigens, promastigote cultures were spun down, washed, killed in a boiling water bath, and sonicated as described above.

Mice and immunization.

Six- to ten-week-old BALB/c mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine), bred in the Small Animal Facility of the National Institute of Immunology, were used for all experiments. For oral tolerance experiments, mice were fed orally with various doses of antigen in 3.5% sodium bicarbonate (Sigma) and challenged in the footpad with homologous antigen emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA). All oral doses were administered with a 21-gauge gavage needle attached to a 1-ml tuberculin syringe. Ovalbumin (OA) and conalbumin (CA) were purchased from Sigma. For bacterial challenge experiments, sonicate-fed and control, unfed, mice were challenged intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 105 S. aureus or 106 S. typhimurium organisms, and 5 to 7 days later, their spleens were harvested and appropriate dilutions were plated out on LB or SS agar. The bacteria were enumerated as CFU per spleen. The limit of detection was 50 CFU/spleen.

T-cell proliferation.

Single-cell suspensions from pooled populations of inguinal and popliteal lymph nodes were cultured in triplicate at 3 × 105 cells/well with graded doses of antigen. All assays were done in 200 μl of Click's medium (Irvine Scientific, Irvine, Calif.) containing 10% fetal calf serum (HyClone, Logan, Utah), 100 μg of penicillin per ml, 100 U of streptomycin per ml, and 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) in 96-well flat-bottom plates (Falcon). Proliferation was measured by pulsing the wells with 0.5 μCi of [3H]thymidine (NEN, Boston, Mass.) 72 h after initiation of culture and harvesting the samples 12 to 16 h later onto glass fiber filters for scintillation spectroscopy (Betaplate; Wallac, Turku, Finland). Replicate-well samples were harvested for cytokine estimation by enzyme-linked immunoassay (EIA).

Adoptive transfer.

T and B cells were purified from spleens of mice 1 week after feeding by magnetic separation on Midi-MACS columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Hamburg, Germany), with Thy1 and B220 beads, respectively, according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Fractionated cells were analyzed by flow cytometry and were used for adoptive transfer experiments only if enrichment was >95%. Unfractionated cells and purified subsets were transferred into naive recipients intravenously (3 × 107 cells per mouse), and the recipients were challenged with live bacteria i.p. 12 h later.

Cytokine assays.

EIAs were performed on culture supernatants with appropriate purified and biotinylated antibody pairs for gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (Genzyme, Boston, Mass.) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) (PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Purified monoclonal anti-mouse IFN-γ or IL-10 was captured onto polystyrene microtiter plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). Culture supernatants were then added, followed by either biotinylated goat anti-mouse IFN-γ or biotinylated monoclonal rat anti-mouse IL-10. Streptavidin peroxidase, followed by hydrogen peroxide and tetramethylbenzidine (Sigma), was used for detection. Titration curves of recombinant IFN-γ (Genzyme) and IL-10 (PharMingen) were used as standards for calculating cytokine concentrations in the culture supernatants. The limit of detection for both cytokines was 15 to 30 pg/ml.

Fragment cultures.

Peyer's patch fragment cultures were set up as described earlier (21). Briefly, Peyer's patches from mice rendered tolerant and control mice not rendered tolerant were recovered by dissection from the small intestines and halved, and groups of four halves were cultured in 2 ml of Dulbecco minimal essential medium (Gibco BRL) supplemented as described above, with graded doses of antigen. Plates were incubated in an atmosphere of 90% O2–10% CO2, and supernatants were tested 5 to 7 days later for antibody by EIA on plates coated with OA and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma). Addition of supernatants was followed by addition of biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgA (Southern Biotechnology). Streptavidin peroxidase, followed by hydrogen peroxide and tetramethylbenzidine (Sigma), was used for detection.

RESULTS

Generation of oral tolerance to soluble nominal antigens.

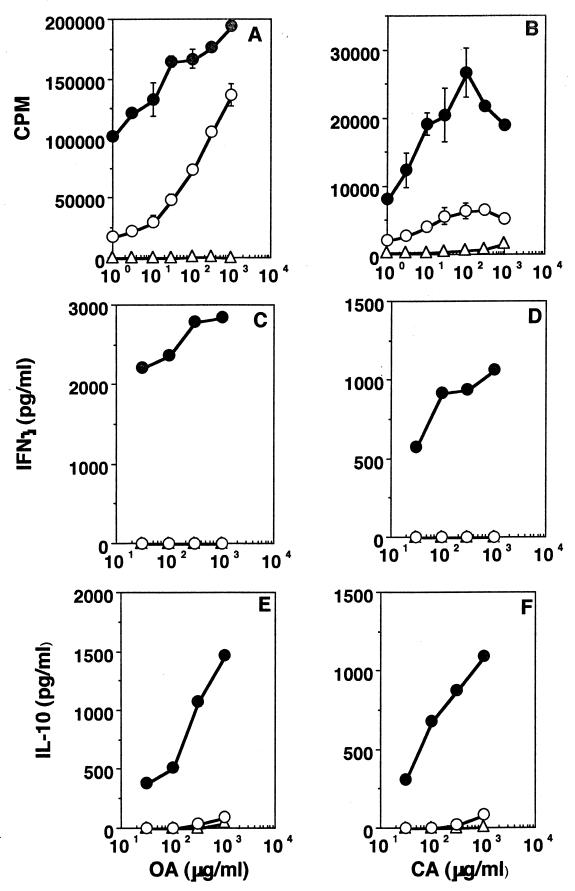

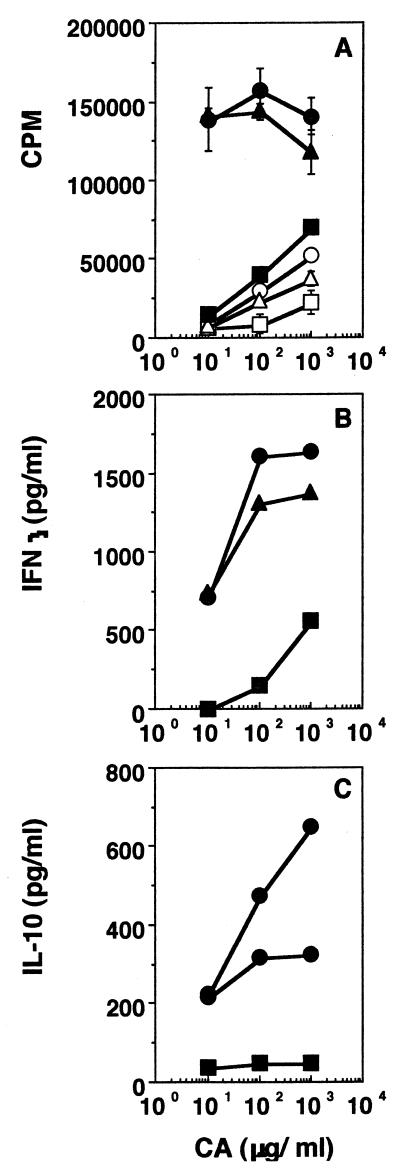

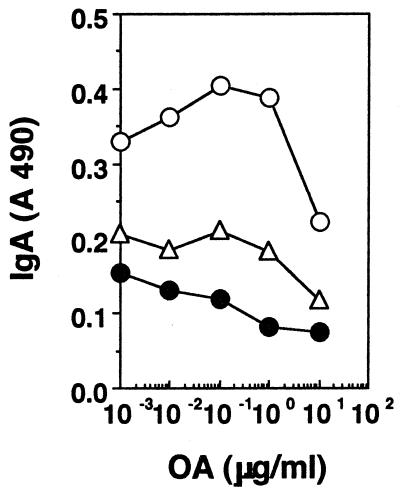

Mice were given 2 mg each of either OA or CA orally, and 1 week later they were challenged in the footpad with 10 μg of homologous antigen in CFA. T-cell stimulation assays were set up a week later with cells from draining lymph nodes, and the results are shown in Fig. 1. It can be seen that both proliferation (Fig. 1A and B) and cytokine secretion (Fig. 1C to F) are lower in cells from fed mice. To establish the phenotype of the responding cells, 10 μg of azide-free anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 (clones RM-5 and 53-6.7, respectively; PharMingen) per ml was added to the cultures (15, 47), and it can be seen that both proliferation (Fig. 2A) and cytokine secretion (Fig. 2B and C) are significantly reduced in the presence of anti-CD4, whereas they are largely unaffected by anti-CD8, suggesting that the cells responding to antigen in culture were CD4 T cells. To determine whether the systemic hyporesponsiveness to fed OA occurred in the face of a good mucosal IgA response, we looked for IgA-committed cells in Peyer's patches of fed mice in fragment cultures (21). Figure 3 shows that higher levels of anti-OA antibodies are, indeed, present in fragment cultures from mice rendered tolerant than in fragment cultures from unfed controls. Here, the lower levels of antibody seen at the higher antigen concentrations are probably due to neutralization of antibodies by antigen present in culture.

FIG. 1.

Induction of oral tolerance for soluble nominal antigens. Proliferation (A and B), IFN-γ (C and D), and IL-10 (E and F) responses of lymph node cells from mice rendered tolerant (open circles), mice not rendered tolerant (filled circles), and control mice that were fed but not challenged s.c. (open triangles) are shown. Antigens used were OA (A, C, and E) and CA (B, D, and F). Results of one experiment, representative of four for each antigen, are shown.

FIG. 2.

Phenotype of cells responding in vitro. Proliferation (A), IFN-γ (B), and IL-10 (C) responses of lymph node cells from mice rendered tolerant (open symbols) and mice not rendered tolerant (closed symbols) cultured in the presence of anti-CD4 (squares) or anti-CD8 (triangles) are shown. No cytokines were detectable in supernatants of cultures from mice rendered tolerant. Results of one experiment, representative of two for each mouse group, are shown.

FIG. 3.

Mucosal IgA responses are enhanced in oral tolerance. Peyer's patches from mice rendered tolerant (open circles), mice not rendered tolerant (filled circles), or control mice that were fed but not challenged s.c. (open triangles) were stimulated in fragment cultures with OA, and supernatants were assayed for anti-OA IgA. Results of one experiment, representative of two for each mouse group, are shown.

Effect of antigen dose in tolerance induction.

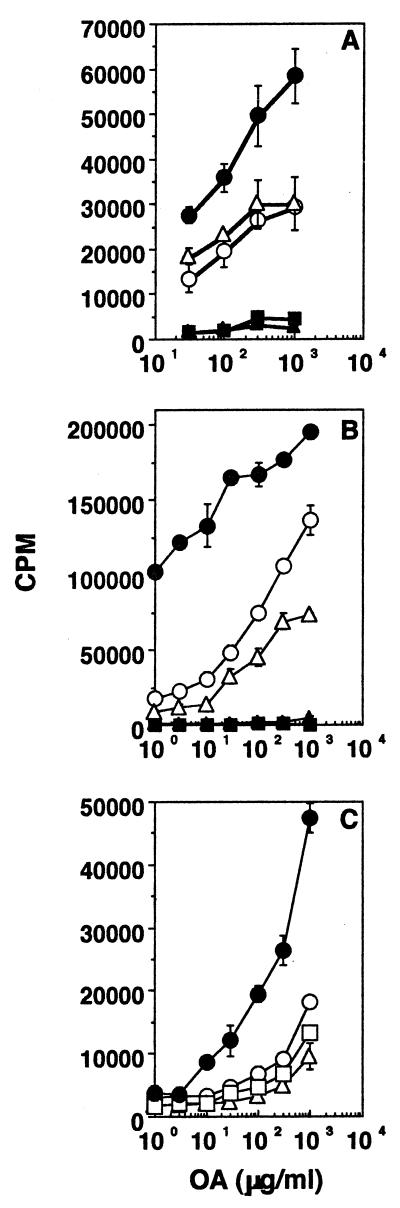

Mice were fed orally with either 1 mg or 300, 100, 30, or 10 μg of CA and challenged in the footpad a week later with 10 μg of CA in CFA. Figure 4 shows that the degree of systemic hyporesponsiveness following feeding depends on the oral dose used. Cells from mice fed with the various doses but not challenged subcutaneously (s.c.) did not respond (data not shown). These data extend earlier reports which indicated that induction of oral tolerance may be linked to antigen dosage (11, 36). These data also demonstrate the potency of oral tolerance—a minute (10 μg) amount of soluble antigen given orally can down regulate the response to the same amount administered systemically in adjuvant.

FIG. 4.

Effect of antigen dose in the induction of oral tolerance. Proliferation responses of lymph node cells from mice not rendered tolerant (line with no symbols) or mice rendered tolerant with either 1 mg (filled circles), 300 μg (filled squares), 100 μg (filled triangles), 30 μg (open triangles), or 10 μg (open circles) of CA and challenged s.c. with 10 μg of CA in CFA are shown. Standard errors of the means were less than 10%. Results of one experiment, representative of four for each mouse group, are shown.

Ability of microbial antigens to induce oral tolerance.

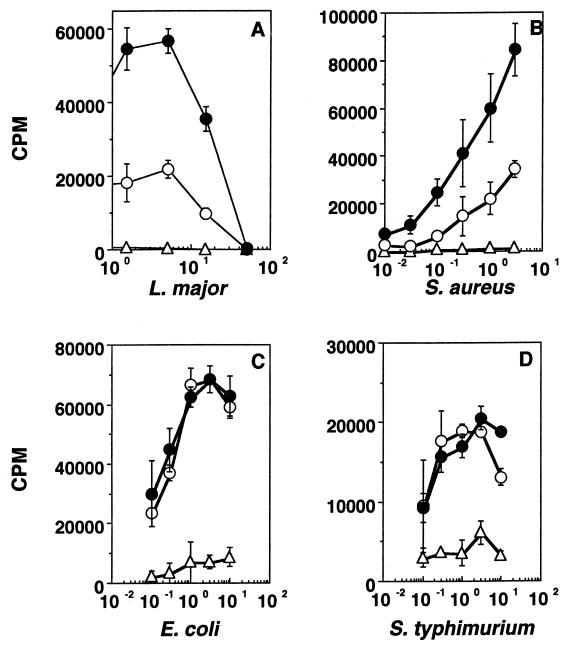

In order to test whether oral exposure to soluble parasite antigens can affect subsequent immune responses to a systemic challenge with the parasite, we treated mice orally with sonicates of E. coli, S. typhimurium, L. major, or S. aureus (2 mg each) and challenged them in the footpad a week later with 10 μg of the homologous antigen in CFA. Figure 5 shows that, while S. typhimurium and E. coli sonicates do not induce oral tolerance, L. major and S. aureus sonicates do. Similar results were seen with oral doses ranging from 1 mg to 100 μg, and the response to L. donovani sonicate was similar to that seen with L. major sonicate (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Induction of oral tolerance for L. major (A), S. aureus (B), E. coli (C), and S. typhimurium (D) sonicates. Proliferation responses of mice rendered tolerant (open circles), mice not rendered tolerant (filled circles), and control unchallenged mice (open triangles) are shown. Units on the x axis are micrograms of the respective antigen per milliliter. Results of one experiment, representative of two (A and B) or three (C and D) for each mouse group, are shown.

Inability of E. coli and S. typhimurium sonicates to affect bystander suppression of oral tolerance for OA.

Since microbial sonicates are complex mixtures of epitopes and bioactive molecules, it is possible that the lack of demonstrable tolerance for E. coli or S. typhimurium sonicates may be related to the presence of molecules in these sonicates that can suppress tolerance in a non-antigen-specific manner. To test this, groups of mice were fed with a mixture of either OA and S. typhimurium sonicate or OA and E. coli sonicate and challenged in the footpad with the homologous mixtures, and T-cell proliferation in vitro in response to both sets of antigens was determined. Figure 6 shows the proliferation response to OA, and it can be seen that neither E. coli nor S. typhimurium antigens present during oral immunization and the subsequent s.c. challenge affect the generation of tolerance for OA. Proliferation responses to E. coli and S. typhimurium antigens were not affected by the presence of OA in these experiments (data not shown). Similar experiments were done with mixtures of S. typhimurium and L. major sonicates, and there was no abrogation of tolerance of L. major antigens (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Induction of oral tolerance for OA (open circles) is unaffected by the coadministration of S. typhimurium (open squares) or E. coli (open triangles) sonicates. Controls include responses of cells from mice fed with the respective mixtures but not challenged s.c. (filled squares and filled triangles) and from control mice not rendered tolerant and challenged s.c. with either OA (filled circles) or OA and S. typhimurium sonicate together (line with no symbols). Standard errors of the means were less than 10%. Results of one experiment, representative of three for each mouse group, are shown.

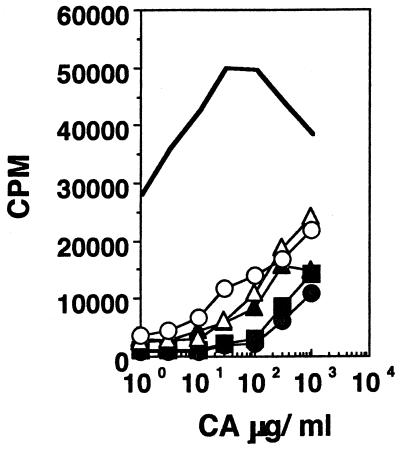

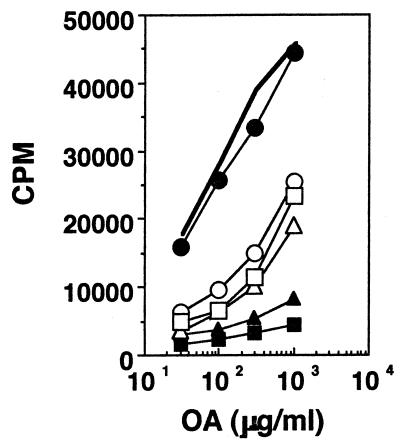

Effect of multiple oral doses on systemic hyporesponsiveness.

The lack of demonstrable oral tolerance for the enteric commensal E. coli and for the cross-reactive S. typhimurium antigens raises the possibility that oral tolerance may be related to the frequency of exposure to a given antigen. Since mice are colonized at birth with E. coli, the systemic response scored in experiments done with adult mice reflects the effects of constant gastrointestinal exposure, rather than a single oral dose, on s.c. challenge. It is possible, therefore, that while the first oral exposure is in fact tolerogenic, subsequent oral exposure does not induce further tolerance. In order to examine this possibility, we looked at the effect of multiple oral doses of OA (1 mg each) on the systemic response to a subsequent s.c. challenge. Figure 7 shows that neither two oral doses 1 week apart (Fig. 7A), two oral doses 14 weeks apart (Fig. 7B), or three oral doses 1 week apart (Fig. 7C) increase systemic hyporesponsiveness beyond that achieved with a single oral dose. A similar pattern was also seen with two doses of S. aureus and L. donovani sonicate given a week apart (data not shown). Thus, multiple oral doses do not enhance systemic unresponsiveness beyond that seen with a single dose in this experimental system.

FIG. 7.

Effect of multiple oral doses on tolerance. Responses of lymph node cells from mice not rendered tolerant (filled circles) or mice rendered tolerant with either a single dose of 1 mg (open circles), two doses of 1 mg each (open triangles), or three doses of 1 mg each (open squares) of OA are shown. Results of one experiment, representative of two for each group of mice, are shown. The oral doses were given 1 week apart for panels A and C and 14 weeks apart for panel B. Filled triangles and filled squares in panels A and B represent responses from control mice fed once or twice but not challenged s.c.

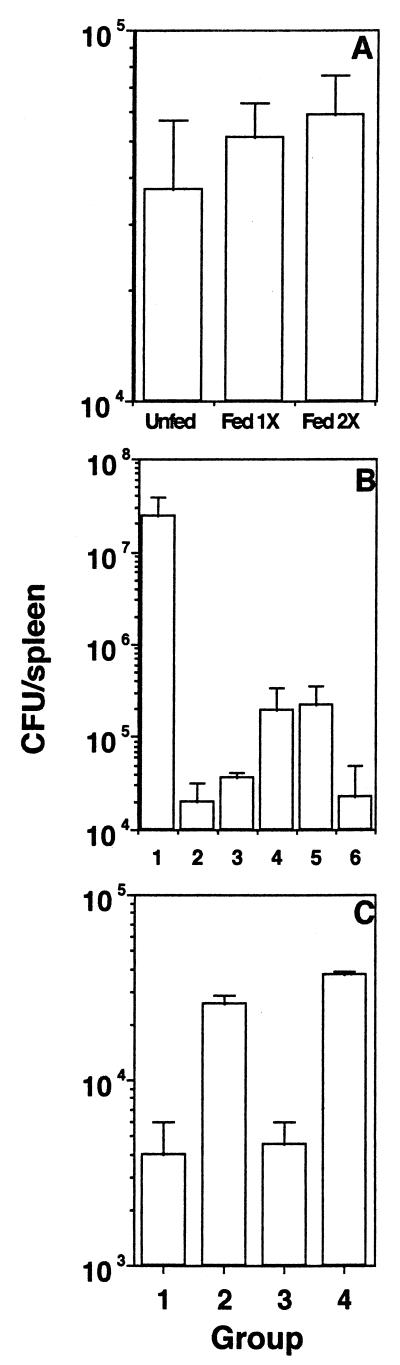

Effect of orally administered antigens on subsequent infections.

Since S. aureus sonicate induces demonstrable oral tolerance while S. typhimurium sonicate does not, we next assessed the effect of oral administration of these sonicates on the ability of the fed mice to clear a systemic challenge of live bacteria. Groups of mice were given S. aureus or S. typhimurium sonicate orally, challenged i.p. with live bacteria a week later, and sacrificed 5 to 6 days after challenge, and splenic bacterial load was determined by plating out individual spleen lysates on LB agar or SS agar, respectively. Figure 8A shows that mice fed with the tolerogenic S. aureus sonicate clear a homologous challenge infection as well as the unfed mice do and that bacterial clearance is not affected by multiple doses. On the other hand, mice fed with the nontolerogenic S. typhimurium sonicate actually clear a challenge infection better than unfed mice do, and the protection afforded by oral administration and that afforded by i.p. administration of sonicate are similar (Fig. 8B). While a good anti-Salmonella antibody response was detected in sera of mice 1 week after i.p. immunization and immediately before s.c. challenge, no significant response was detected in sera of the fed mice (data not shown), indicating that antibodies are not responsible for the enhanced systemic clearance of bacteria that is seen with fed mice. Adoptive transfer experiments showed that purified T cells from fed mice could transfer protection to naive recipients while purified B cells were ineffective (Fig. 8C).

FIG. 8.

Effect of orally administered antigens on subsequent homologous systemic infection. (A) Groups of mice were fed 2 mg of S. aureus sonicate either once or twice before i.p. challenge. (B) Mice were either unfed (bar 1); fed with 1, 2, or 3 mg of S. typhimurium sonicate (bars 2 to 4, respectively); or immunized with 10 or 100 μg of sonicate i.p. (bars 5 and 6, respectively) before i.p. challenge. (C) Purified splenic T cells (bar 1), splenic B cells (bar 2), or whole spleen cells (bar 3) from mice fed with 2 mg of S. typhimurium sonicate or whole spleen cells from unfed mice (bar 4) were adoptively transferred into naive recipients before i.p. challenge. Results of one experiment, representative of two for each group of mice, are shown.

DISCUSSION

The intestine is home to a host of aerobic and anaerobic microorganisms that constitute the normal flora of the gut (37), and control of their number and diversity is required to prevent opportunistic infections and inflammatory bowel diseases. Individuals appear to be immunologically tolerant of their own intestinal flora but not of heterologous intestinal flora (8), and tolerance of autologous flora has been shown to be disrupted in a model of experimental colitis (9). The mechanisms controlling tolerance of microbial antigens in this complex environment are unknown, but various mechanisms have been implicated in experimental models of oral tolerance of simple soluble and inert particulate antigens. These include clonal anergy (26, 42), serum factors (1, 18), suppressor T cells (20, 22, 23, 29, 34), and immunomodulation by γδ T cells (19, 24, 25, 27).

The presence of microorganisms and their products in the gut may influence systemic immunity in two distinct ways. On the one hand, some bacteria may express antigens resembling potential allergens, and they might, therefore, either cause or aggravate allergic reactions. In this context, it has been reported that rats colonized at birth with a recombinant E. coli strain producing OA make anti-OA IgE, but not antilipopolysaccharide or antifimbrial antibody (7), underlining the complex nature of responses to antigens in the gut. On the other hand, products of pathogenic organisms may induce oral tolerance, and this could conceivably lead to dampening of a subsequent protective immune response against the virulent organism. We tested antigens from various microorganisms, including normal gut flora and pathogens that invade by the enteric or systemic routes, in our experimental model of tolerance. We found that both leishmanial and staphyloccocal sonicates were tolerogenic in a T-cell stimulation readout assay (Fig. 5A and B), a pattern similar to that seen with OA or CA (Fig. 1A and B) and in keeping with the reported induction of systemic tolerance of orally administered staphylococcal enterotoxin B (28). Curiously, E. coli and S. typhimurium sonicates were not tolerogenic (Fig. 5C and D), raising the possibility that molecules that can suppress tolerance in a non-antigen-specific manner, as cholera toxin has been reported to do (10, 33, 38), may be present in the latter sonicates. However, this does not seem to be the case, as coadministration of these sonicates with either OA or leishmanial antigens does not abrogate tolerance of either (Fig. 5). Our results differ from those reported earlier (6) where E. coli heat-labile toxin was found to abrogate the induction of oral tolerance of unrelated antigens when administered together with them. This difference may be explained by the fact that the bacterial sonicates used in our study are made from heat-killed bacteria and therefore lack the adjuvanticity of the toxin. However, it has also been reported that cryptic determinants of an antigen may be nontolerogenic even when immunodominant determinants of the same antigen are tolerogenic (14), and we cannot conclusively rule out the possibility that certain mixtures of antigens will simply not induce tolerance because of a predominance of nontolerogenic determinants.

We next considered the possibility, envisaged earlier (3), that oral tolerance is related to the frequency of oral exposure to antigen. E. coli is a normal component of the murine gut flora, and the lack of oral tolerance of E. coli antigens (and of the cross-reactive S. typhimurium antigens) might indicate that, although initial oral exposure to these antigens is indeed tolerogenic, subsequent exposures may not enhance systemic hyporesponsiveness any further. Thus, the s.c. response that we see with both fed and unfed mice might well be an induced-tolerance response compared to the response in mice that were never exposed to the bacteria in their guts. Indeed, we found that multiple feeding with a tolerogenic antigen did not increase systemic hyporesponsiveness beyond that seen with a single dose (Fig. 7). In this context, it has been reported that oral tolerance is lacking in γδ knockout mice (19), and our prediction is that T-cell responses to E. coli sonicate following s.c. immunization will be higher in adult γδ knockout mice than in conventional mice.

The physiological consequences of oral tolerance for bacterial antigens may manifest not only as hyporesponsiveness of T cells from the mice rendered tolerant in vitro but also as an impaired ability of mice rendered tolerant to clear a subsequent systemic challenge with live bacteria. However, this appears not to be the case, and mice fed with the tolerogenic S. aureus sonicate clear a challenge infection as well as unfed mice do (Fig. 8A). Interestingly, S. typhimurium sonicate that is not tolerogenic by the oral route is actually immunogenic, and allows fed mice to clear a challenge infection better than unfed mice (Fig. 8B), and T cells, rather than B cells, are responsible for this enhanced clearance (Fig. 8C). These results extend our earlier data showing that live S. typhimurium given orally generates an excellent mucosal and systemic Th1 immune response (12). Our present data indicate that, although no direct T-cell readout of priming may be evident following oral administration of inert S. typhimurium, protective T-cell responses are, in fact, generated and can be read out as enhanced protection against challenge with virulent bacteria.

The oral administration of antigens has been shown to be effective in preventing or suppressing experimental autoimmune encephalitis, collagen-induced arthritis, thyroiditis, and uveitis (5, 30, 32, 40, 43, 48), and the strategy is being considered for the clinical treatment of autoimmune diseases (31, 41, 45). However, a note of caution has been suggested by the report that oral administration of autoantigen may induce cytotoxic T cells that can lead to an induction of autoimmune diabetes (2). The present study shows that, even under conditions where systemic tolerance is observed, the effect may be entirely achievable with a single dose, and chronic or frequent oral administration may in fact immunize.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants to A.G. and V.B. from the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. The National Institute of Immunology is supported by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andre C, Heremans J F, Vaerman J P, Cambiaso C L. A mechanism for the induction of immunological tolerance by antigen feeding: antigen-antibody complexes. J Exp Med. 1975;142:1509–1519. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.6.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanas E, Carbone F R, Allison J, Miller J F A P, Heath W R. Induction of autoimmune diabetes by oral administration of autoantigen. Science. 1996;274:1707–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Challacombe S J, Tomasi T B., Jr Systemic tolerance and secretory immunity after oral immunization. J Exp Med. 1980;152:1459–1472. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.6.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chase M W. Inhibition of experimental drug allergy by prior feeding of the sensitizing agent. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1946;61:257–259. doi: 10.3181/00379727-61-15294p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Kuchroo V K, Inobe J I, Hafler D A, Weiner H L. Regulatory T cell clones induced by oral tolerance: suppression of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Science. 1994;265:1237–1240. doi: 10.1126/science.7520605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clements J D, Hartzog N M, Lyon F L. Adjuvant activity of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin and effect on the induction of oral tolerance in mice to unrelated protein antigens. Vaccine. 1988;6:269–277. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(88)90223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahlman A, Ahlstedt S, Hanson L A, Telemo E, Wold A E, Dahlgren U I. Induction of IgE antibodies and T-cell reactivity to ovalbumin in rats colonized with Escherichia coli genetically manipulated to produce ovalbumin. Immunology. 1992;76:225–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duchmann R, Kaiser I, Hermann E, Mayet W, Ewe K, Meyer zum Buschenfelde K H. Tolerance exists towards resident intestinal flora but is broken in active inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;102:448–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duchmann R, Schmitt E, Knolle P, Meyer zum Buschenfelde K H, Neurath M. Tolerance towards resident intestinal flora in mice is abrogated in experimental colitis and restored by treatment with interleukin-10 or antibodies to interleukin-12. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:934–938. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elson C O, Ealding W. Cholera toxin feeding did not induce oral tolerance in mice and abrogated oral tolerance to an unrelated protein antigen. J Immunol. 1984;133:2892–2897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman A, Weiner H L. Induction of anergy or active suppression following oral tolerance is determined by antigen dosage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6688–6692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.George A. Generation of gamma interferon responses in murine Peyer's patches following oral immunization. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4606–4611. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4606-4611.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutgemann I, Fahrer A M, Altman J D, Davis M M, Chien Y-H. Induction of rapid T cell activation and tolerance by systemic presentation of orally administered antigen. Immunity. 1998;8:667–673. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80571-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hachimura S, Fujikawa Y, Enomoto A, Kim S-M, Ametani A, Kaminogawa S. Differential inhibition of T and B cell responses to individual antigenic determinants in orally tolerized mice. Int Immunol. 1994;6:1791–1797. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.11.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollander N, Pillemer E, Weissman I L. Effects of Lyt antibodies on T cell functions: augmentation by anti-Lyt-1 as opposed to inhibition by anti-Lyt-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:1148–1151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.2.1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoyne G F, Thomas W R. T-cell responses to orally administered antigens. Study of the kinetics of lymphokine production after single and multiple feeding. Immunology. 1995;84:304–309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kagnoff M F. Functional characteristics of Peyer's patch lymphoid cells. IV. Effect of antigen feeding on the frequency of antigen-specific B cells. J Immunol. 1977;118:992–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kagnoff M F. Effects of antigen feeding on intestinal and systemic immune responses. III. Antigen specific serum-mediated suppression of humoral antibody responses after antigen feeding. Cell Immunol. 1978;40:186–203. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(78)90326-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ke Y, Pearce K, Lake J P, Ziegler H K, Kapp J A. γδ T lymphocytes regulate the induction and maintenance of oral tolerance. J Immunol. 1997;158:3610–3618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiyono H, McGhee J R, Wannemuehler M J, Michalek S M. Lack of oral tolerance in C3H/HeJ mice. J Exp Med. 1982;155:605–610. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.2.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Logan A C, Chow K-P N, George A, Weinstein P D, Cebra J J. Use of Peyer's patch and lymph node fragment cultures to compare local immune responses to Morganella morganii. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1024–1031. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.1024-1031.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mattingly J A, Waksman B H. Immunologic suppression after oral administration of antigen. I. Specific suppressor cells formed in rat Peyer's patches after oral administration of sheep erythrocytes and their systemic migration. J Immunol. 1978;121:1878–1883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattingly J A, Kaplan J M, Janeway C A., Jr Two distinct antigen-specific suppressor factors induced by the oral administration of antigen. J Exp Med. 1980;152:545–554. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.3.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMenamin C, Pimm C, McKersey M, Holt P G. Regulation of IgE responses to inhaled antigen in mice by antigen-specific γδ T cells. Science. 1994;265:1869–1871. doi: 10.1126/science.7916481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMenamin C, McKersey M, Kuehnlein P, Huenig T, Holt P G. Gamma delta T cells down-regulate primary IgE responses in rats to inhaled soluble protein antigens. J Immunol. 1995;154:4390–4394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melamed D, Friedman A. In vivo tolerization of Th1 lymphocytes following a single feeding with ovalbumin: anergy in the absence of suppression. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1974–1981. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mengel J, Cardillo F, Aroeira L S, Williams O, Russo M, Vaz M. Anti-γδ T cell antibody blocks the induction and maintenance of oral tolerance to ovalbumin in mice. Immunol Lett. 1995;48:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(95)02451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Migita K, Ochi A. Induction of clonal anergy by oral administration of staphylococcal enterotoxin B. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2081–2086. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller A, Lider O, Weiner H L. Antigen-driven bystander suppression after oral administration of antigens. J Exp Med. 1991;174:791–798. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller A, Zhang Z J, Sobel R A, al-Sabbah A, Weiner H L. Suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by oral administration of myelin basic protein. VI. Suppression of adoptively transferred disease and differential effects of oral vs. intravenous tolerization. J Neuroimmunol. 1993;46:73–82. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(93)90235-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muir A, Schatz D, Maclaren N. Antigen-specific immunotherapy: oral tolerance and subcutaneous immunization in the treatment of insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1993;9:279–287. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610090408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peterson K E, Braley-Mullen H. Suppression of murine experimental autoimmune thyroiditis by oral administration of porcine thyroglobulin. Cell Immunol. 1995;166:123–130. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pierre P, Denis O, Bazin H, Mbongolo-Mbella E, Vaerman J P. Modulation of oral tolerance to ovalbumin by cholera toxin and its B subunit. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:3179–3182. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richman L K, Chiller J M, Brown W R, Hanson D G, Vaz N M. Enterically induced immunologic tolerance. I. Induction of suppressor T lymphocytes by intragastric administration of soluble proteins. J Immunol. 1978;121:2429–2434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richman L K, Graeff A S, Yarchoan R, Strober W. Simultaneous induction of antigen-specific IgA helper T cells and IgG suppressor T cells in the murine Peyer's patch after protein feeding. J Immunol. 1981;126:2079–2083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saklayen M G, Pesce A J, Pollack V E, Gabriel-Michael J. Kinetics of oral tolerance: study of variables affecting tolerance induced by oral administration of antigen. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1984;73:5–9. doi: 10.1159/000233428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon G L, Gorbach S L. Intestinal flora in health and disease. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:174–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stok W, van der Heijden P J, Bianchi A T J. Conversion of orally induced suppression of the mucosal immune response to ovalbumin into stimulation by conjugating ovalbumin to cholera toxin or its B subunit. Vaccine. 1994;12:521–526. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thatte J, Rath S, Bal V. Immunization with live versus killed Salmonella typhimurium leads to the generation of an IFN-gamma dominant versus an IL-4 dominant immune response. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1431–1436. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.11.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson H S, Harper N, Bevan D J, Staines N A. Suppression of collagen induced arthritis by oral administration of type II collagen: changes in immune and arthritic responses mediated by active peripheral suppression. Autoimmunity. 1993;16:189–199. doi: 10.3109/08916939308993327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trentham D E, Dynesisus-Trentham R A, Orav E J, Combitchi D, Lorenzo C, Sewell K L, Haffler D A, Weiner H L. Effects of oral administration of type II collagen on rheumatoid arthritis. Science. 1993;261:1727–1730. doi: 10.1126/science.8378772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Houten N, Blake S F. Direct measurement of anergy of antigen-specific T cells following oral tolerance induction. J Immunol. 1996;157:1337–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Z Y, Qiao J, Melms A, Link H. T cell reactivity to acetylcholine receptor in rats orally tolerized against experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Cell Immunol. 1993;152:394–404. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1993.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wannemuehler M J, Kiyono H, Babb J L, Michalek S M, McGhee J R. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) regulation of the immune response: LPS converts germfree mice to sensitivity to oral tolerance induction. J Immunol. 1982;129:959–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiner H L, Mackin G A, Matsui M, Orav E J, Khoury S J, Dawson D M, Hafler D A. Double blind pilot trial of oral tolerization with myelin antigen in multiple sclerosis. Science. 1993;259:1321–1324. doi: 10.1126/science.7680493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wells H G. Studies on the chemistry of anaphylaxis. III. Experiments with isolated proteins, especially those of the hen's egg. J Infect Dis. 1911;9:147–171. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilde D B, Marrack P, Kappler J, Dialynas D P, Fitch F W. Evidence implicating L3T4 in class II MHC antigen reactivity: monoclonal antibody GK1.5 (anti-L3T4a) blocks class II MHC antigen-specific proliferation, release of lymphokines and binding by cloned murine helper T lymphocyte lines. J Immunol. 1983;131:2178–2183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Z Y, Lee C S Y, Lider O, Weiner H L. Suppression of adjuvant arthritis in Lewis rats by oral administration of type II collagen. J Immunol. 1990;145:2489–2493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]