Abstract

In the present study, we investigated the isolation frequency, the genetic diversity, and the infectious characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) from the incoming meat and the meat products, the environment, and the workers’ nasal cavities, in two meat-processing establishments in northern Greece. The isolated S. aureus strains were examined for their resistance to antimicrobials, carriage of the mecA and mecC genes, carriage of genes encoding for the production of nine staphylococcal enterotoxins, carriage of the Panton–Valentine Leukocidin and Toxic Shock Syndrome genes, and the ability to form biofilm. The genetic diversity of the isolates was evaluated using Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) and spa typing. S. aureus was isolated from 13.8% of the 160 samples examined, while only one sample (0.6%) was contaminated by MRSA carrying the mecA gene. The evaluation of the antimicrobial susceptibility of the isolates revealed low antimicrobial resistance. The higher resistance frequencies were observed for penicillin (68.2%), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (36.4%) and tetracycline (18.2%), while 31.8% of the isolates were sensitive to all antimicrobials examined. Multidrug resistance was observed in two isolates. None of the isolates carried the mecC or lukF-PV genes, and two isolates (9.1%) harbored the tst gene. Eight isolates (36.4%) carried the seb gene, one carried the sed gene, two (9.1%) carried both the sed and sei genes, and one isolate (4.5%) carried the seb, sed and sei genes. Twenty-one (95.5%) of the isolates showed moderate biofilm production ability, while only one (4.5%) was characterized as a strong biofilm producer. Genotyping of the isolates by PFGE indicates that S. aureus from different meat-processing establishments represent separate genetic populations. Ten different spa types were identified, while no common spa type isolates were detected within the two plants. Overall, our findings emphasize the need for the strict application of good hygienic practices at the plant level to control the spread of S. aureus and MRSA to the community through the end products.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA, meat products, antimicrobial resistance, virulence genes, biofilms, Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE), spa typing, next-generation sequencing

1. Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is part of the skin and mucous microbiota of humans, with the nasal cavity constituting the most common carriage site. The nasal cavity is regarded as the source of colonization of secondary body sites, such as the hands [1]. S. aureus is also an important versatile pathogen causing various types of infections, ranging from skin and soft-tissue infections to life-threatening septicemia and toxin-mediated diseases, such as staphylococcal food poisoning (SFP), toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1) and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) [2]. Moreover, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is of particular importance for both public and animal health. There are three groups among MRSA strains: hospital-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA), community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) and livestock-associated MRSA (LA-MRSA) [3,4]. Transmission of LA-MRSA occurs mainly in humans with occupational exposure to livestock [4]. It is also likely that LA-MRSA may be transmitted through contaminated meat products [3,5].

The presence of S. aureus and MRSA in the environment of livestock farms and slaughterhouses and the risk of their transmission to the meat and the workers in these settings has been of great concern to the scientific community [6,7,8,9,10,11].

Pathogenic bacterial attachment and the formation of persistent biofilms in food-processing establishments represent an important risk for food contamination and the spread of pathogens in the community [12,13]. S. aureus can develop persistent biofilms on both biotic and abiotic surfaces [14]. The co-existence of different species within the biofilm matrix of staphylococci, and especially of S. aureus, with numerous benefits for them, such higher antimicrobial tolerance, has been well documented [15,16]. Preventing the development of biofilms on food-processing surfaces is critical for food safety.

Given their ever-changing epidemiology of S. aureus and MRSA, updated information is needed for the implementation of effective control measures [17,18]. The identification of possible sources and routes of meat contamination in the processing facilities contributes significantly to the evaluation and improvement of preventive measures targeting their transmission to the final products and therefore their dispersion in the community. In this study, to obtain more insights into the epidemiology of S. aureus, in meat-processing plants, we investigated the prevalence of S. aureus and MRSA in the incoming meat and meat products, the environment, and the workers’ nasal cavities of two meat-processing establishments in northern Greece. All S. aureus isolates were tested for their resistance to certain antimicrobials. In addition, staphylococcal strains were tested by molecular methods for detection of the mecA, mecC, pvl, tst-1 and enterotoxin genes, while their ability to form biofilms was also investigated. Their genetic relatedness was evaluated using Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) and spa typing.

2. Results

2.1. Isolation of S. aureus

S. aureus was isolated from 22 of the 160 (13.8%) samples examined from the two meat-processing establishments. The isolation frequency was 23.3% (14/60) and 8.0% (8/100) for plant F and Z, respectively (Table 1). The isolation frequency of S. aureus in descending order was 37.5% (6/16) from ground meat products, 25% (5/20) from workers, 12.3% (7/57) from equipment, 10.0% (2/20) from incoming pork meat, 8.3% (1/12) from incoming bovine meat, and 4.5% (1/22) from infrastructure. The isolation frequency of S. aureus was 8.1% (3/37) in samples from the incoming meat (bovine, porcine and ovine), and 25.0% (6/24) in samples from the processed raw meat products (ground meat and non-ground meat products), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Isolation frequency of Staphylococcus aureus and of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) from the incoming meat, raw meat products, the environment, and the workers of two meat-processing plants in northern Greece.

| Sample Origin | Plant F | Plant Z | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n * |

S. aureus ± (%) |

MRSA (%) | n * | S. aureus ± (%) | MRSA (%) | n * |

S. aureus ± (%) |

MRSA (%) | |

| Incoming bovine meat | 6 | 1 (16.7) | - | 6 | - | - | 12 | 1 (8.3) | - |

| Incoming porcine meat | 6 | 1 (16.7) | - | 14 | 1 (7.1) | - | 20 | 2 (10.0) | - |

| Incoming ovine meat | 4 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 5 | - | - |

| Non-ground meat products | 6 | - | - | 2 | - | - | 8 | - | - |

| Ground meat products | 8 | 4 (50.0) | - | 8 | 2 (25.0) | 1 (12.5) | 16 | 6 (37.5) | 1 (6.3) |

| Nasal cavity of workers | 9 | 3 (33.3) | - | 11 | 2 (18.2) | - | 20 | 5 (25.0) | - |

| Infrastructure | 5 | - | - | 17 | 1 (5.9) | - | 22 | 1 (4.5) | - |

| Equipment | 16 | 5 (31.3) | - | 41 | 2 (4.9) | - | 57 | 7 (12.3) | - |

| Total | 60 | 14 (23.3) | - | 100 | 8 (8.0) | 1 (1.0) | 160 | 22 (13.8) | 1 (0.6) |

n *, number of samples; ±, includes MRSA isolates.

2.2. Antimicrobial Resistance of S. aureus

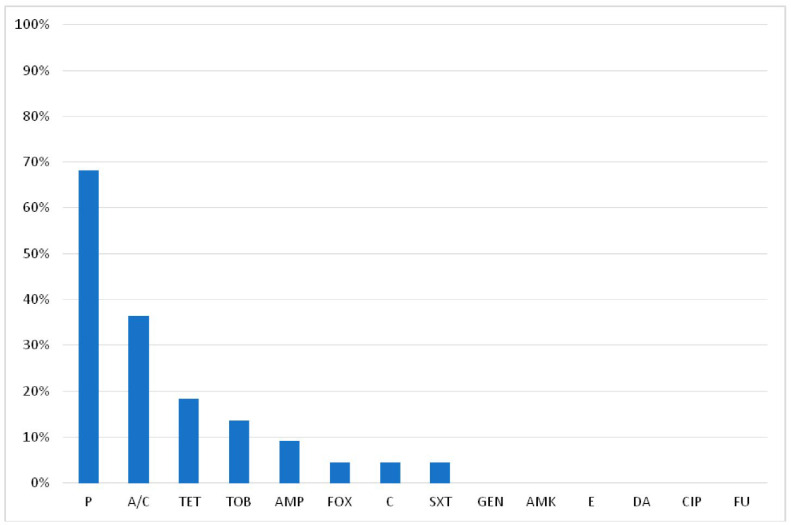

The frequency of resistance (in descending order) of the S. aureus strains to the tested antimicrobials was: penicillin (P) (68.2%), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (A/C) (36.4%), tetracycline (TET) (18.2%), tobramycin (TOB) (13.6%), ampicillin (AMP) (9.1%), cefoxitin (FOX) (4.5%), chloramphenicol (C) (4.5%) and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (SXT) (4.5%) (Figure 1). One isolate (Z112) being resistant to cefoxitin was phenotypically considered as MRSA; seven isolates (31.8%) were susceptible to all antimicrobials examined while 45.4% (10/22) of the S. aureus was resistant to more than one antimicrobial (Table 2). In total, seven antimicrobial resistance profiles (ARPs) were found, with the profiles ‘P’ and ‘P, A/C’ being the most frequent (22.7% each). Two isolates (F40 and Z112) were identified as multidrug resistant (MDR), exhibiting resistance to three and six different classes of antimicrobials, respectively.

Figure 1.

Frequency of antimicrobial resistance of S. aureus isolates from two meat-processing plants.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus and of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains isolated from different sites within two meat-processing establishments in northern Greece.

| Sample Code * |

Sample Origin | Antimicrobial Resistance Profile ** | mecA | mecC | lukF-PV/tst | SE Genes | Biofilm Formation Ability |

Spa Type | PFGE Electrophoretic Cluster |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F20 | Meat | P, TET, TOB | - | - | -/- | - | moderate | t084 | A |

| F22 | Equipment | - | - | - | -/+ | sed, sei | moderate | t012 | NT *** |

| F28 | Meat product | P, A/C, TET | - | - | -/- | - | moderate | t499 | A |

| F29 | Meat product | P, TET | - | - | -/- | - | moderate | t774 | A |

| F32 | Meat product | P | - | - | -/- | seb | moderate | t084 | A |

| F36 | Equipment | P, A/C | - | - | -/- | seb | moderate | t084 | A |

| F37 | Equipment | P | - | - | -/- | seb | moderate | t084 | A |

| F39 | Equipment | P, A/C | - | - | -/- | seb | moderate | t084 | A |

| F40 | Equipment | P, AMP, A/C, TOB | - | - | -/- | seb | moderate | t084 | A |

| F42 | Meat product | P, A/C | - | - | -/- | seb | moderate | t084 | A |

| F43 | Meat product | P, A/C | - | - | -/- | seb | moderate | t084 | A |

| F44 | Human nasal cavity | P | - | - | -/- | sed, sei | moderate | t891 | NT |

| F45 | Human nasal cavity | P | - | - | -/- | sed | moderate | t197 | A |

| F46 | Human nasal cavity | P | - | - | -/- | seb | moderate | t084 | NT |

| Ζ5 | Human nasal cavity | P, A/C | - | - | -/+ | seb, sed, sei | moderate | t1510 | NT |

| Ζ7 | Human nasal cavity | - | - | - | -/- | - | moderate | new | C |

| Ζ18 | Infrastructure | - | - | - | -/- | - | moderate | new | C |

| Ζ19 | Equipment | - | - | - | -/- | - | moderate | t091 | B |

| Ζ77 | Meat product | - | - | - | -/- | - | moderate | new | C |

| Ζ104 | Equipment | - | - | - | -/- | - | strong | t091 | B |

| Ζ112 | Meat product | P, AMP, A/C, FOX, TET, TOB, C, SXT | + | - | -/- | - | moderate | t899 | NT *** |

| Ζ146 | Meat product | - | - | - | -/- | - | moderate | new | C |

* F: Plant F, Ζ: Plant Ζ. ** (P). penicillin, (AMP) ampicillin, (A/C) amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, (TET) tetracycline, (FOX) cefoxitin, (GEN) gentamicin, (AMK) amikacin, (ΤOΒ) tobramycin, (E) erythromycin, (DA) clindamycin, (CIP) ciprofloxacin, (C) chloramphenicol, (FU) fucidic acid, (SXT) sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim. *** NT: Isolates non-typeable by PFGE.

2.3. Carriage of the mecA, mecC, tst, lukF-PV and Enterotoxin Genes

The mecC and lukF-PV genes were not detected in any S. aureus isolate. Two isolates carried the tst gene: one from equipment of plant F and the other from a worker’s nasal cavity from plant Z (Table 2). Ten of the isolates (45.6%) did not carry any of the examined staphylococcal enterotoxin genes, eight of the isolates (36.4%) carried only the seb gene, two (9.1%) carried the sed and sei genes and one (4.5%) carried the seb, sed and sei genes (Table 2). Of the 12 isolates that carried enterotoxin genes, five (41.7%) were isolated from equipment surfaces, four (33.3%) from workers’ nasal cavities and three (16.7%) from meat products. The MRSA isolate (Z112) that originated from a sample of meat product in plant Z carried the mecA gene, but it did not harbor any of the remaining virulence genes examined (Table 2).

2.4. Biofilm Formation Ability

All except one of the S. aureus isolates (21/22, 95.5%) were classified as moderate biofilm producers and the remaining isolate was classified as a strong biofilm producer (Table 2).

2.5. Spa Typing

The spa typing of the 22 S. aureus strains revealed ten spa types, one of which was detected for the first time. About half the strains (9/22) belonged to spa type t084, two strains belonged to type t091 and four strains belonged to the new spa type. The sequence of the novel spa type (repeats 07-23-12-12-21-17-13-34-33-34) was confirmed in the whole genome sequence; actually, it is similar to the spa type t2414 (07-23-12-12-21-17-34-33-34) with one additional repeat (repeat 13). The other seven isolates belonged to t012, t197, t499, t774, t891, t899 and t1510 (Table 2). The MRSA strain belonged to spa type t899 and was not typeable by PFGE. This spa type belongs either to CC398 or to CC9 [19]. The five S. aureus isolates from the nasal cavities of workers were assigned to five different spa types (t084, t197, t891, t1510, ‘new’).

2.6. Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis Typing

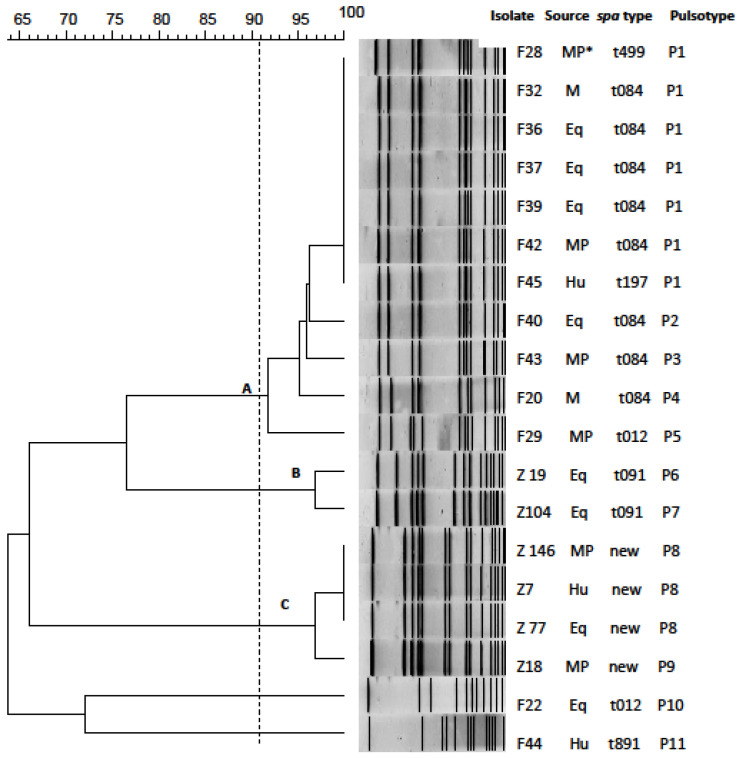

Nineteen of the staphylococcal isolates were typeable by PFGE revealing 11 distinct pulsotypes (Figure 2). At a similarity level of 91%, most of the S. aureus isolates (57.9%, 11/19) were grouped into the cluster A; isolates from the same processing plant were assigned into separate clusters (A, B, and C). Two isolates from plant F (F22 and F44) were not assigned to any of the three clusters (Figure 2). Within clusters, common pulsotypes among isolates originating from human (Hu), meat (M), meat product (MP), and equipment (Eq) samples were identified: within cluster A, pulsotype P1 was shared by Hu, M, MP and Eq isolates, while within cluster C, pulsotype P8 was shared by Hu, MP and Eq isolates.

Figure 2.

PFGE dendrogram of the S. aureus isolates. * MP = meat product, M = incoming meat, Eq = equipment, Hu = human.

2.7. Next-Generation Sequencing

Analysis of the whole genome sequence of the two isolates (Z77 and Z112) showed that Z77, which was sensitive to all antibiotics tested, did not carry any antimicrobial resistance gene. Regarding the isolate Ζ112, which was resistant to several antibiotics, genes conferring resistance to beta-lactams (mecA, blaZ), chloramphenicol (fexA), tetracycline (tetM) and trimethoprim (dfrC) were detected; however, no gene associated with resistance to tobramycin was detected (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of the analysis of the whole genome sequences of the two S. aureus isolates subjected to NGS.

| Feature | Isolate Z77 | Isolate Z112 |

|---|---|---|

| Number of contigs | 85 | 309 |

| N50 (bp) | 169,989 | 134,669 |

| GC (%), | 33.0 | 33.1 |

| Length (bp) | 2,896,939 | 2,840,021 |

| Sequence type (ST) | 97 | 398 |

| Spa type | Novel type (repeats 07-23-12-12-21-17-13-34-33-34) | t899 |

| Resistance genes | - | mecA, blaZ, tetM, fexA, dfrC |

| Antibiotic efflux genes |

mgrA, arlR, mepR, norC, sdrM, sepA |

mgrA, arlR, mepR, norA, norC, sdrM, sepA |

| Toxin genes | hlgA, hlgB, hlgC, lukD, lukE | hlgA, hlgB, hlgC |

| Exoenzyme genes | aur, splA, splB, splE | aur |

| Host immune defense genes | sak, scn | - |

| Plasmids | rep20 | rep21, repUS43 |

Spa typing confirmed the type t899 in the Z112 isolate, while it was not possible to be defined in the Z77 isolate. The Z112 isolate belonged to sequence type ST398 and the Z77 isolate to ST97, respectively. Among the toxin genes we found, hlgA, hlgB, and hlgC were encoding for gamma-hemolysin components A, B and C, respectively, while lukD and lukE encode for leucotoxins D and E; the exoenzyme genes aur, splA, splB, and splE encode for the aureolysin and serine protease-like proteins A, B and E, respectively; finally, sak and scn genes encode for the host immune defense proteins staphylokinase and staphylococcal complement inhibitor.

3. Discussion

3.1. Isolation, Antimicrobial Susceptibly and Biofilm Formation Ability of S. aureus and MRSA Isolates

Considering that bibliographic data on the prevalence of staphylococci in the products and in the environment of meat-processing establishments are limited, the main objective of this study was to report the prevalence of S. aureus and MRSA in two meat-processing establishments in northern Greece. In general, compared to meat-processing establishments, a higher detection frequency of S. aureus and MRSA has been reported for beef, pork and poultry meat products at the retail level [20]. In the present study, S. aureus was isolated from 13.8% of the samples examined, while only one sample of ground meat (0.6%) was contaminated with MRSA. These detection frequencies are lower than the estimates of 29.2% and 3.2% for S. aureus and MRSA, respectively, which were reported in a global meta-analysis of different meat products [20]. In samples taken from equipment surfaces of the meat-processing plants, the overall S. aureus isolation frequency was 12.3%, being comparable with a previous Spanish study, which reported a prevalence of 15.5% on equipment surfaces of a pork-processing plant [21]. However, further data concerning the S. aureus isolation frequency from equipment surfaces are scarce in the literature. In the personnel of the two meat-processing establishments, the isolation frequency of S. aureus was 25%. This finding is not surprising, since the detection of S. aureus in the population is around 20% and 60% in persistent and occasional nasal carriers, respectively [22]. Personnel in slaughterhouses and meat-processing plants are among the groups of workers with the highest incidence of occupational injuries. Injuries that lead to the disruption of skin-tissue integrity [23,24] as well as the frequent exposure to materials of animal origin (nasal secretions, gastrointestinal contents, etc.) favor the contamination of workers with S. aureus [11,25]. On the other hand, none of the samples from workers tested positive for MRSA. Drougka et al. [8] reported the isolation of MRSA from 4.2% of slaughterhouse workers in Greece, where the prevalence in the general population is low (0.94%) [26]. In our study, the lack of detection of MRSA in the samples obtained from workers at the examined facilities is likely due to the small number of samples examined. However, even the mere presence of S. aureus and MRSA on the surface of meat constitutes a potential risk for their transmission to humans, particularly to those who work in meat-processing companies [6].

To gain insight into the identification of specific phenotypic and genomic characteristics of S. aureus isolated from the meat-processing plants, we investigated their antimicrobial susceptibility, biofilm formation capacity and carriage of enterotoxin genes. The highest resistance frequency was observed to P (68.2%), A/C (36.4%), TET (18.2%) and TOB (13.6%). Seven distinct antimicrobial resistance profiles were revealed, with the profiles ‘P’ (22.7%) and ‘P, A/C’ (22.7%) being the most frequent. Finally, two MDR isolates (F40 and Z112) were revealed. The presence of antimicrobial-resistant strains of S. aureus and MRSA has been reported in various foods as well as in meat [8,27] and meat products [28,29] and multiple profiles of antimicrobial resistance are often observed among the S. aureus isolates [30]. The high resistance frequencies of S. aureus and MRSA isolates from livestock, meat and food handlers to P and TET, ranging from 60.9% to 100%, and from 5.6% to 89.1% respectively, have been reported by numerous studies worldwide (USA [29], Lithuania [31], Greece [8,32], Italy [33], Nigeria [34], China [35] and Korea [36]). The frequent resistance to penicillins and tetracyclines is apparently related to the widespread use of these antimicrobials due to their low cost, ease of access (without a prescription) and administration. We also observed a high (80%) resistance frequency to P among the S. aureus isolates originating from the workers’ nasal cavities (in four out of five positive workers) (Table 2). These findings are similar to those previously reported (70% [37], 48% [38], 57.9% [39]). On the other hand, the sensitivity of the workers’ S. aureus isolates to TET in the present study may be due to the infrequent use of tetracyclines in human clinical practice [40].

Previous studies have shown the presence (2.9%) of MDR MRSA isolates in turkey and pork meat [41]. Interestingly, the single MRSA isolate in our study (from ground pork meat) was characterized as MDR, showing resistance to six antimicrobial classes. Overall, the evaluation of antimicrobial susceptibility revealed a high frequency of resistance to specific antimicrobials as well as variable ARPs among the S. aureus isolates. Therefore, our findings emphasize the need for preventive measures to control the dispersion of antimicrobial resistance along the entire food production chain [42] with strict application of proper hygiene and industrial practices.

All S. aureus isolates were characterized by moderate biofilm-forming capabilities in polystyrene microtiter plates. In line with our findings, previous studies have reported the ability of biofilm formation by S. aureus isolates from raw meat [43], from several food-processing facilities [44,45] and from food of animal origin [35]. The ability of S. aureus to produce biofilms and their coexistence with saprophytic microorganisms within these biofilms result in persistent contamination sources in food-processing facilities [16,46].

3.2. Enterotoxin Gene Carriage of S. aureus Isolates

In the present study, 54.5% of the S. aureus isolates carried at least the seb or sed genes alone, together or in combination with sei (Table 2). Similarly high frequencies of enterotoxin gene carriage (51.3%) were reported for isolates from food of both animal and plant origin in China (sec (38.5%), seg (19.7%), sej (16.2%), see (12.8%), sea (11.1%), seb (10.3%), sei (4.3%), sed (3.4%) and seh (1.7%)) [47]. Normanno et al. [48] reported that 45.2% of the S. aureus isolates from meat and meat products at the retail level in Italy could produce at least the ‘classic’ enterotoxins (SEA (30.3%), SEB (7.6%), SEC (51.5%), SED (6.1%), SEA+SEB (1.5%), SEA+SED (3.0%)). In the same study, 50% of the isolates from surfaces in contact with meat could also produce SEC.

Four of the five (80%) S. aureus strains isolated from the workers’ nasal cavities were enterotoxigenic and five of the seven (71%) were from the equipment surfaces. In a study conducted in Hong Kong, 40% of the S. aureus isolates from the nasal cavities of meat handlers in mass-catering kitchens carried at least one enterotoxin gene, with sea (20%) and seb (11%) being the most frequently detected [49]. Workers carrying enterotoxigenic strains of S. aureus are recognized as the main source of their spread in food either through direct contact or indirectly through respiratory secretions [50].

The application of good hygiene practices during food processing and the effort to control and limit the population of staphylococci to low levels in foods are the most important measures for the prevention of staphylococcal intoxications [51].

3.3. Carriage of Genes Encoding for the Toxic Shock Syndrome and Panton–Valentine Leukocidin Toxins

The tst gene was detected in a S. aureus strain isolated from a worker’s nasal cavity and in one sample obtained from processing equipment. This low-isolation frequency (9.1%) is in line with the results of other studies. A zero-detection frequency was reported for isolates recovered from workers of a slaughterhouse in Greece and food handlers in Lebanon, respectively [8,52]. A low prevalence (5.3%) was also reported in samples taken from the hands of workers in restaurants in Spain [53]. These tst gene detection frequencies in workers are considerably lower compared to those reported for the general population in several countries, ranging from 15.8% to 40.0% (Brazil 15.8% [54], Madagascar 21.0% [55], Iran 22.8% [56], Spain 28.3% [57] and Egypt 40.0% [58]). There are limited reports on tst gene carriage among S. aureus isolates from processing surfaces. Sahin et al. [59] reported one S. aureus strain (isolated from surface samples in food-processing establishments in Turkey) carrying the tst gene, while Sospedra et al. [53] did not recover any S. aureus isolates carrying the tst gene from surfaces and equipment in restaurants in Spain.

In the present study, none of the S. aureus isolates carried the lukF-PV gene. Weese et al. [60] reported that none of the MRSA isolates from raw meat and its preparations in Canada carried this gene. On the contrary, Gutierrez et al. [45] reported that 10.1% of the S. aureus isolates from ground beef and pork chops in Colombia carried the lukF-PVL gene.

Given (a) the limited pertinent available literature internationally, (b) the fact that food handlers and processing surfaces are important sources of food contamination, and (c) the severity of clinical manifestations associated with TSST-1 and PVL intoxications, the low detection frequency of S. aureus isolates carrying these genes does not justify complacency.

3.4. Genetic Diversity of S. aureus Isolates

Another scope of this study was to reveal the genetic diversity of the S. aureus isolates to better understand the transmission routes and infection sources of this pathogen in meat-processing establishments. Ten different spa types were identified based on spa-typing; among them, five spa types (t197, t499, t774, t899 and t1510) were detected for the first time in Greece. Most of the strains belonged to the spa type t084 (40.9%), four (18.2%) to a new spa type and two (9.1%) to t091 (Figure 2). According to the Ridom Spa Server, the global spread of spa types t084 and t091 is quite high (1.74% and 0.99%, respectively). The most prevalent spa type (t084) was detected in all types of samples from plant F (Figure 2). Methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) strains of this type have been isolated from several sources globally [57,61,62]. The spa type t091 represents the basic type of the clonal complex CC7 and has been detected as either MSSA or MRSA from various sources [57,63,64,65,66]. In addition, the spa type t012, which was identified in one isolate in our study, displays high global spread (1.53%). The spa types t197, t499, t774, t891, t899 and t1510 show a relatively low global spread, ranging between 0.02% and 0.31%. Interestingly, S. aureus isolates from workers belonged to different spa types (t084, t197, t891, t1510 and to a new type), which are usually isolated from human clinical samples [67,68,69]. The only MRSA isolate in the present study belonged to spa type t899. To our knowledge, and according to the data available in the Ridom Spa Server, this spa type is detected for the first time in Greece, and its global spread is 0.31%, mainly in Italy and other European countries. Originally, this spa type was related with MLST type ST9, but recently, it is most often related with ST398, which is the predominant LA-MRSA lineage in Europe [19,70]. Although t011 and t034 still constitute the main spa types associated to CC398, isolates belonging to spa type t899 have been reported as the cause of sporadic illness in humans, and they are increasingly being described in the human and veterinary medical literature [71,72,73,74,75].

PFGE genotyping of the isolates revealed the existence of three PFGE clusters (A, B and C) (Figure 2). Each of them comprised enterotoxigenic isolates; cluster A included isolates from plant F only, whereas clusters B and C contained isolates from plant Z only. The assignment of isolates from the same processing plant into separate clusters indicates that S. aureus from different meat-processing establishments represent separate genetic populations. Furthermore, the findings of indistinguishable S. aureus pulsotypes from meat products, workers and equipment surfaces indicates probable cross-contamination pathways. These findings, in combination with the fact that isolates with no common spa type were detected from the two plants, supports the hypothesis that there is no universal spread of certain spa types and there is also a distinct genetic population of S. aureus in each processing plant. These facts emphasize the need for the strict application of good hygienic practices at the processing plant level in order to control the spread of foodborne and particularly multi-drug resistant pathogens to the community through the end products.

3.5. Next-Generation Sequencing

NGS was performed on two isolates, one MSSA belonging to the novel spa type, and one MRSA belonging to spa type t899. NGS analysis revealed that the isolate of the new spa type belonged to sequence type ST97 and the MRSA t899 isolate belonged to LA-associated ST398 (Table 3). The ST97 strain did not have any enterotoxin gene but carried the antibiotic efflux genes mgr (resistance to quinolones, tetracyclines), arlR (fluoroquinolones, disinfection agents and antiseptics), mepR (tetracycline, glycycycline), norC (hydrophobic quinolones such as moxifloxacin and norfloxacin), sdrM (norfloxacin, ethidium bromide) and sepA (resistance to disinfectants and dyes). The ST398/t899 carried the same with ST97 antibiotic efflux genes plus the norA (resistance to hydrophilic quinolones such as ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin) and the antimicrobial resistance genes mecA and blaZ (resistance to beta-lactamases), the tetM (tetracycline), the fexA (phencicol antibiotics) and the dfrC (diaminopyrimidine antibiotic) [76]. In the international literature, it has been reported that the ST97 S. aureus clone is shared by a great number of different spa types. Zhang et al. [77] isolated 82 S. aureus ST97 from bovine clinical mastitis in China, which shared 15 different spa types (t359, t237, t4682, t521, t730, t16314, t16315, t224, t6297, t2756, t131, t1234, t267, UK-1). In a study contacted in Czech Republic, Pomorska et al. [78] reported that S. aureus isolates t267 and t359 from the blood of hospitalized patients belonged to the ST97 clone. Sato et al. [79] isolated five MRSA ST97 strains from pigs of one farm in Japan identified as spa type t1236. To our knowledge, this is the first time that the ST97 clone of S. aureus has been isolated in Greece.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection

In the present study, we examined a total of 160 samples from two meat-processing establishments located in northern Greece (60 and 100 samples from establishment F and Z, respectively). The distance between the two establishments is more than 200 km. Thirty-seven samples were collected from the incoming meat (bovine, ovine, porcine), 24 samples from the final meat products (ground meat and non-ground meat products), 79 samples from the environment (22 from infrastructure surfaces that do not come in contact with meat and 57 from equipment surfaces) and 20 samples were obtained from the nasal cavities of workers (Table 1).

Surface sampling was performed by swabbing a minimum area of 100 cm2 (or the maximum available area, in case of smaller tools) using swabs moistened in buffered peptone water (LAB M, Lancashire, United Kingdom). A bi-lateral nasal (anterior nares) swab sample was taken from all workers (who participated voluntarily).

All samples were collected aseptically using sterile swabs along with single-use, screw-capped tubes filled with Stuart transport medium (Deltalab, Barcelona, Spain). Samples were transported to the laboratory under refrigerated conditions in less than four hours from the time of sampling.

4.2. Isolation and Identification of Staphylococcus aureus

Upon arrival to the laboratory, each sample was immediately transferred to a test tube filled with 10 mL of Tryptone Soy Broth (TSB, LAB M) supplemented with 6.5% (w/v) NaCl (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 0.3% (w/v) yeast extract (LAB M). Following an 18 h incubation at 37 °C, 10 μL of the pre-enriched broth was surface-plated onto Baird–Parker Agar (LAB M) supplemented with egg-yolk tellurite (LAB M), and the plates were incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 48 h. Up to four presumptive S. aureus colonies (black colonies surrounded by an opaque zone and a clearance zone around the opaque zone) from each plate were sub-cultured on Tryptone Soya Agar (LAB M) for 24 h at 37 °C and were then subjected to Gram staining, along with mannitol fermentation testing and catalase-testing [80]. Furthermore, all suspect colonies were subjected to a rapid test (Microgen Staph Rapid Test; Microgen Bioproducts, Surrey, UK) for the detection of the coagulase enzyme and of the protein A, assisting the tentative identification to the species level (S. aureus). Among them, one presumptive S. aureus isolate (Gram-positive, catalase-positive, mannitol-positive, coagulase-positive and protein A-positive) per sample was randomly chosen and stored under freezing conditions (−80 °C) in cryotubes containing TSB with 20% glycerol for further processing.

4.3. Molecular Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus

For species confirmation of the presumptive S. aureus isolates, a PCR test detecting the coa and the species-specific nuc genes was performed. Genomic DNA was extracted by using a DNA purification protocol for Gram-positive bacteria (Pure Link Genomic DNA kit; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), while PCR conditions [81] and primers [82,83] previously described were used (Supplementary Table S1).

4.4. Detection of Virulence Genes and Methicillin Resistance Genes

Multiplex PCRs were used for the detection of virulence genes contributing to the pathogenicity of S. aureus and for the detection of methicillin resistance genes. Two separate sets of primers and multiplex PCR reactions were used to assess the carriage of genes that encode nine types of SEs (sea, seb, sec, seh and sej; sed, see, seg, sei) and the carriage of the tst gene, which encodes for the production of the toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1) [84]). The carriage of the mecA and mecC genes, which confer resistance to methicillin and the carriage of the lukF-PV gene, which encodes for the Panton–Valentine Leukocidin toxin (PVL) were sought also via multiplex PCR using the primers and conditions described by Stegger et al. [85] (Supplementary Table S1).

4.5. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by the disc-diffusion method using Mueller–Hinton agar (Merck) according to Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing [86]. For each isolate, the inocula were prepared by adjusting the turbidity to 0.5 McFarland. Susceptibility was evaluated to the following 14 antimicrobials: the beta-lactam antibiotics penicillin 10 IU (P), ampicillin 10 μg (AMP), cefoxitin 30 μg (FOX) and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 20/10 μg (A/C); tetracycline 30 μg (TET); the aminoglycosides gentamicin 10 μg (GEN), tobramycin 10 μg (ΤOΒ) and amikacin 30 μg (AMK); the macrolide erythromycin (E) 10 μg; the lincosamide clindamycin 2 μg (DA); ciprofloxacin 5 μg (CIP) belonging to quinolones; chloramphenicol 30 μg (C) belonging to amphenicol class; fusidic acid 10 μg (FU) belonging to fusidanes; trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 1.25/23.75 μg (SXT) belonging to diaminopyrimidine/sulfonamide classes. S. aureus ATTC 25923; Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC29212 were used as control strains. Multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories [87]. S. aureus ATTC 25923; Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC29212 were used as control strains.

4.6. Assessment of Biofilm-Formation Ability

The ability of the S. aureus isolates to produce biofilms was evaluated following the protocol of the microtiter plate method, as described by Wang et al. [88]. Staphylococcal strains were characterized according to Borges et al. [89] as no biofilm producers, weak biofilm producers, moderate biofilm producers, or strong biofilm producers.

4.7. Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis Analysis

PFGE analysis of the S. aureus isolates was performed according to a standardized protocol [90] with the SmaI endonuclease (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA) using a CHEF-DR III apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). DNA from Salmonella enterica serotype Braenderup H9812, which was digested with XbaI, was used as a reference size standard, while PFGE patterns were analyzed using the FPQuest software (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc. Pty Ltd.). PFGE profiles were compared using the Dice correlation coefficient with a maximum position tolerance of 1.5% and an optimization of 1.5%, while the Unweighted Pair Group Method using Averages (UPGMA) was used for clustering analysis and the generation of a dendrogram.

4.8. Spa Typing

For amplification of the Staphylococcus protein A (spa) repeat region, the extracted DNA (from Section 4.3) was subjected to a PCR using the primers described by Aires-de-Sousa et al. [91] according to the protocol described in the Ridom Spa Server website (http://spaserver.ridom.de/ accessed on 2 March 2021). PCR products were sequenced in a 3130 genetic analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, South San Francisco, CA, USA). For the analysis of spa sequences, the software Ridom StaphTypeTM (Ridom GmbH, Wόrzburg, Germany) was used [92].

4.9. Next-Generation Sequencing and Analysis of the Whole Genome

Two isolates were selected for further analysis by next-generation sequencing: S. aureus isolate was assigned to the novel spa type (Z77) and the multi-resistant MRSA isolate (Z112). DNA was extracted using the DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and its concentration was measured using the Qubit double strand (ds) DNA HS assay kit (Q32851, Life Technologies Corporation, Grand Island, NY, USA). NGS was performed using the Ion PGM Hi-Q View Sequencing kit on an Ion Torrent PGM Platform (Life Technologies Corporation).

The procedures of shearing, purification, ligation, barcoding, size selection, library amplification and quantitation, emulsion PCR and enrichment were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR products were loaded on an Ion-316™ chip kit V2BC. The Ion PGM Hi-Q View (200) chemistry (Ion PGM Hi-Q View Sequencing kit) was applied. The sequence reads were de novo assembled and annotated using Geneious Prime version 2021.2.1. Sequences from the whole genome of the samples Z77 and Z112 were submitted to ENA and received the accession numbers ERS13643805 and ERS13643806, respectively.

MLST analysis was performed using the free web-based S. aureus database in PubMLST (https: //pubml st.org/saure us/ accessed on 10 March 2021) [93]. Antimicrobial resistance genes were identified using the online databases Resfinder version 4.1 [94] and Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) [76], with the selection criteria set to perfect (100% identity) and strict (>95% identity) hits only to the reference sequences in CARD [95]. Virulence genes and plasmid content were identified using the VirulenceFinder 2.0 and PlasmidFinder version 2.1 from the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (http://www.genomicepidemiology.org/ accessed on 15 March 2021) [96]. The threshold for %ID and for the minimum length were set to 90% and 60%, respectively.

5. Conclusions

Despite the limitations of the present study (two meat processing establishments and a relatively low number of examined samples), interesting conclusions can be drawn from the results. This study revealed the low prevalence of MRSA and MDR S. aureus, no common palsotypes among the isolates from the two establishments and high genetic diversity by spa typing. Although the prevalence of MRSA was low, meat-processing establishments are a very important spot for controlling pathogen spread in the community. Thus, the implementation of rules of good hygiene practice in combination with biosecurity measures are crucial factors for achieving this goal. However, further data are needed to monitor the spread of MRSA at meet the meat processing establishments level.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathogens11111370/s1, Table S1: Primers used in this study for the detection of molecular characterization genes, toxin genes and methicillin resistance genes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S. and C.K.; methodology, D.S., C.K., A.Z. and A.A.; software, S.P. and A.P.; validation, D.K., D.S., A.P., A.A. and A.Z.; data curation, D.S., C.K., A.P., V.G., S.P. and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S., C.K., D.K.; writing—review and editing, D.S., A.A., A.P., A.Z., and C.K.; funding acquisition, D.S. and A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, in compliance with the Greek legislation, and the protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Veterinary Research Institute, ELGO Dimitra.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

The current work was supported in part by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 grant VEO (grant number 874735).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kaspar U., Kriegeskorte A., Schubert T., Peters G., Rudack C., Pieper D.H., Wos-Oxley M., Becker K. The culturome of the human nose habitats reveals individual bacterial fingerprint patterns. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;18:2130–2142. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowy F.D. Staphylococcus aureus Infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339:520–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuny C., Köck R., Witte W. Livestock associated MRSA (LA-MRSA) and its relevance for humans in Germany. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013;303:331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzgerald J.R. Livestock-associated Staphylococcus aureus: Origin, evolution and public health threat. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verkade E., Kluytmans J. Livestock-associated Staphylococcus aureus CC398: Animal reservoirs and human infections. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014;21:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Food Safety Authority Assessment of the Public Health significance of meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in animals and foods. EFSA J. 2009;7:1–73. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2009.993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Jonge R., E Verdier J., Havelaar A.H. Prevalence of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus amongst professional meat handlers in the Netherlands, March–July 2008. Eurosurveillance. 2010;15:19712. doi: 10.2807/ese.15.46.19712-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drougka E., Foka A., Giormezis N., Sergelidis D., Militsopoulou M., Jelastopulu E., Komodromos D., Sarrou S., Anastassiou E.D., Petinaki E., et al. Multidrug-resistant enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus lineages isolated from animals, their carcasses, the personnel, and the environment of an abattoir in Greece. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019;43:e13961. doi: 10.1111/jfpp.13961. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huber H., Koller S., Giezendanner N., Stephan R., Zweifel C. Prevalence and characteristics of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in humans in contact with farm animals, in livestock, and in food of animal origin, Switzerland, 2009. Eurosurveillance. 2010;15:19542. doi: 10.2807/ese.15.16.19542-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klimešová M., Manga I., Nejeschlebová L., Horáček J., Ponížil A., Vondrušková E. Occurrence of Staphylococcus aureus in cattle, sheep, goat, and pig rearing in the Czech Republic. Acta Vet. Brno. 2017;86:3–10. doi: 10.2754/avb201786010003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Cleef B.A.G.L., Broens E.M., Voss A., Huijsdens X.W., Züchner L., VAN Benthem B.H.B., Kluytmans J.A.J.W., Mulders M.N., VAN DE Giessen A.W. High prevalence of nasal MRSA carriage in slaughterhouse workers in contact with live pigs in The Netherlands. Epidemiol. Infect. 2010;138:756–763. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bridier A., Sanchez-Vizuete P., Guilbaud M., Piard J.-C., Naïtali M., Briandet R. Biofilm-associated persistence of food-borne pathogens. Food Microbiol. 2015;45:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Møretrø T., Langsrud S. Residential Bacteria on Surfaces in the Food Industry and Their Implications for Food Safety and Quality. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017;16:1022–1041. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donlan R.M. Biofilms: Microbial Life on Surfaces. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002;8:881–890. doi: 10.3201/eid0809.020063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dass S.C., Wang R. Biofilm through the Looking Glass: A Microbial Food Safety Perspective. Pathogens. 2022;11:346. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11030346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lianou A., Nychas G.-J.E., Koutsoumanis K.P. Strain variability in biofilm formation: A food safety and quality perspective. Food Res. Int. 2020;137:109424. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen C.-J., Huang Y.-C. New epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus infection in Asia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014;20:605–623. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stryjewski M., Corey G.R. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: An Evolving Pathogen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014;58:S10–S19. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.European Food Safety Authority. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2017/2018. EFSA J. 2020;18:e06007. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2020.6007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ou Q., Peng Y., Lin D., Bai C., Zhang T., Lin J., Ye X., Yao Z. A Meta-Analysis of the Global Prevalence Rates of Staphylococcus aureus and Methicillin-Resistant S. aureus Contamination of Different Raw Meat Products. J. Food Prot. 2017;80:763–774. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-16-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palá T.R., Sevilla A. Microbial Contamination of Carcasses, Meat, and Equipment from an Iberian Pork Cutting Plant. J. Food Prot. 2004;67:1624–1629. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-67.8.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kluytmans J.A.J.W. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in food products: Cause for concern or case for complacency? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010;16:11–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cai C., Perry M.J., Sorock G.S., Hauser R., Spanjer K.J., Mittleman M., Stentz T.L. Laceration injuries among workers at meat packing plants. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2005;47:403–410. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyeremateng-Amoah E., Nowell J., Lutty A., Lees P.S., Ba E.K.S. Laceration injuries and infections among workers in the poultry processing and pork meatpacking industries. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2014;57:669–682. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neyra R.C., Frisancho J.A., Rinsky J.L., Resnick C., Carroll K.C., Rule A.M., Ross T., You Y., Price L.B., Silbergeld E.K. Multidrug-Resistant and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Hog Slaughter and Processing Plant Workers and Their Community in North Carolina (USA) Environ. Health Perspect. 2014;122:471–477. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karapsias S., Piperaki E.T., Spiliopoulou I., Katsanis G., Kotsovili A.T. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage among healthy employees of the Hellenic Air Force. Eurosurveillance. 2008;13:18999. doi: 10.2807/ese.13.40.18999-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beneke B., Klees S., Stührenberg B., Fetsch A., Kraushaar B., Tenhagen B.-A. Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a Fresh Meat Pork Production Chain. J. Food Prot. 2011;74:126–129. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-10-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson C.R., Davis J.A., Barrett J.B. Prevalence and Characterization of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Retail Meat and Humans in Georgia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013;51:1199–1207. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03166-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leibler J.H., Jordan J.A., Brownstein K., Lander L., Price L.B., Perry M.J. Staphylococcus aureus Nasal Carriage among Beefpacking Workers in a Midwestern United States Slaughterhouse. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0148789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson D.A., Enright M.C. Evolutionary Models of the Emergence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3926–3934. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3926-3934.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ivbule M., Miklaševičs E., Čupāne L., Bērziņa L., Bālinš A., Valdovska A. Presence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in slaughterhouse environment, pigs, carcasses, and workers. J. Vet. Res. 2017;61:267–277. doi: 10.1515/jvetres-2017-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papadopoulos P., Papadopoulos T., Angelidis A.S., Boukouvala E., Zdragas A., Papa A., Hadjichristodoulou C., Sergelidis D. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) along the production chain of dairy products in north-western Greece. Food Microbiol. 2018;69:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parisi A., Caruso M., Normanno G., Latorre L., Miccolupo A., Fraccalvieri R., Intini F., Manginelli T., Santagada G. MRSA in swine, farmers and abattoir workers in Southern Italy. Food Microbiol. 2019;82:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okorie-Kanu O.J., Anyanwu M.U., Ezenduka E.V., Mgbeahuruike A.C., Thapaliya D., Gerbig G., Ugwuijem E.E., Okorie-Kanu C.O., Agbowo P., Olorunleke S., et al. Molecular epidemiology, genetic diversity and antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from chicken and pig carcasses, and carcass handlers. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0232913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ou C., Shang D., Yang J., Chen B., Chang J., Jin F., Shi C. Prevalence of multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates with strong biofilm formation ability among animal-based food in Shanghai. Food Control. 2020;112:107106. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mechesso A.F., Moon D.C., Ryoo G.-S., Song H.-J., Chung H.Y., Kim S.U., Choi J.-H., Kang H.Y., Na S.H., Yoon S.-S., et al. Resistance profiling and molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from goats in Korea. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021;336:108901. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2020.108901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Acco M., Ferreira F., Henriques J., Tondo E. Identification of multiple strains of Staphylococcus aureus colonizing nasal mucosa of food handlers. Food Microbiol. 2003;20:489–493. doi: 10.1016/S0740-0020(03)00049-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castro A., Santos C., Meireles H., Silva J., Teixeira P. Food handlers as potential sources of dissemination of virulent strains of Staphylococcus aureus in the community. J. Infect. Public Health. 2016;9:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seow W.-L., Mahyudin N.A., Amin-Nordin S., Radu S., Abdul-Mutalib N.A. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus among cooked food and food handlers associated with their occupational information in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Food Control. 2021;124:107872. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.107872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.di Cerbo A., Pezzuto F., Guidetti G., Canello S., Corsi L. Tetracyclines: Insights and Updates of their Use in Human and Animal Pathology and their Potential Toxicity. Open Biochem. J. 2019;13:1–12. doi: 10.2174/1874091X01913010001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ge B., Mukherjee S., Hsu C.-H., Davis J.A., Tran T.T.T., Yang Q., Abbott J.W., Ayers S.L., Young S.R., Crarey E.T., et al. MRSA and multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in U.S. retail meats, 2010–2011. Food Microbiol. 2017;62:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones T.F., E Kellum M., Porter S.S., Bell M., Schaffner W. An outbreak of community-acquired foodborne illness caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002;8:82–84. doi: 10.3201/eid0801.010174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang H., Wang H., Liang L., Xu X., Zhou G. Prevalence, genetic characterization and biofilm formation in vitro of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from raw chicken meat at retail level in Nanjing, China. Food Control. 2018;86:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.10.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Ciccio P., Vergara A., Festino A., Paludi D., Zanardi E., Ghidini S., Ianieri A. Biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus on food contact surfaces: Relationship with temperature and cell surface hydrophobicity. Food Control. 2015;50:930–936. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.10.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutiérrez D., Delgado S., Vázquez-Sánchez D., Martínez B., Cabo M.L., Rodríguez A., Herrera J.J., García P. Incidence of Staphylococcus aureus and Analysis of Associated Bacterial Communities on Food Industry Surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:8547–8554. doi: 10.1128/aem.02045-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sofos J.N., Geornaras I. Overview of current meat hygiene and safety risks and summary of recent studies on biofilms, and control of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in nonintact, and Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat, meat products. Meat Sci. 2010;86:2–14. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hao D., Xing X., Li G., Wang X., Zhang M., Zhang W., Xia X., Meng J. Prevalence, Toxin Gene Profiles, and Antimicrobial Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Quick-Frozen Dumplings. J. Food Prot. 2015;78:218–223. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Normanno G., Firinu A., Virgilio S., Mula G., Dambrosio A., Poggiu A., Decastelli L., Mioni R., Scuota S., Bolzoni G. Coagulase-positive Staphylococci and Staphylococcus aureus in food products marketed in Italy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005;98:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ho J., O’Donoghue M., Boost M. Occupational exposure to raw meat: A newly-recognized risk factor for Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization amongst food handlers. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2014;217:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Argudín M.Á., Mendoza M.C., Rodicio M.R. Food Poisoning and Staphylococcus aureus Enterotoxins. Toxins. 2010;2:1751–1773. doi: 10.3390/toxins2071751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.International Commission on Microbiological Specifications for Foods . Microorganisms in Foods 6: Microbial Ecology of Food Commodities. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York, NY, USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Osman M., Kamal-Dine K., El Omari K., Rafei R., Dabboussi F., Hamze M. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant nasal carriage in food handlers in Lebanon: A potential source of transmission of virulent strains in the community. Access Microbiol. 2019;1:e000043. doi: 10.1099/acmi.0.000043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sospedra I., Mañes J., Soriano J. Report of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1) from Staphylococcus aureus isolated in food handlers and surfaces from foodservice establishments. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2012;80:288–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Danelli T., Duarte F.C., De Oliveira T.A., Da Silva R.S., Alfieri D.F., Gonçalves G.B., De Oliveira C.F., Tavares E.R., Yamauchi L.M., Perugini M.R.E., et al. Nasal Carriage by Staphylococcus aureus among Healthcare Workers and Students Attending a University Hospital in Southern Brazil: Prevalence, Phenotypic, and Molecular Characteristics. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2020;2020:3808036. doi: 10.1155/2020/3808036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hogan B., Rakotozandrindrainy R., Al-Emran H., Dekker D., Hahn A., Jaeger A., Poppert S., Frickmann H., Hagen R.M., Micheel V., et al. Prevalence of nasal colonisation by methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among healthcare workers and students in Madagascar. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016;16:420. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1733-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pakbaz Z., Sahraian M.A., Sabzi S., Mahmoodi M., Pourmand M.R. Prevalence of sea, seb, sec, sed, and tsst-1 genes of Staphylococcus aureus in nasal carriage and their association with multiple sclerosis. Germs. 2017;7:171–177. doi: 10.18683/germs.2017.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lozano C., Gómez-Sanz E., Benito D., Aspiroz C., Zarazaga M., Torres C. Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage, virulence traits, antibiotic resistance mechanisms, and genetic lineages in healthy humans in Spain, with detection of CC398 and CC97 strains. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011;301:500–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elbargisy R.M., Rizk D.E., Abdel-Rhman S.H. Toxin gene profile and antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical and food samples in Egypt. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2016;10:428–437. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Şahin S., Moğulkoç M., Kalin R., Karahan M. Determination of the Important Toxin Genes of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Meat Samples, Food Handlers and Food Processing Surfaces in Turkey. Isr. J. Vet. Med. 2020;75:42–49. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weese J., Avery B., Reid-Smith R. Detection and quantification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) clones in retail meat products. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010;51:338–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Odetokun I., Ballhausen B., Adetunji V.O., Ghali-Mohammed I., Adelowo M.T., Adetunji S., Fetsch A. Staphylococcus aureus in two municipal abattoirs in Nigeria: Risk perception, spread and public health implications. Vet. Microbiol. 2018;216:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Strommenger B., Braulke C., Heuck D., Schmidt C., Pasemann B., Nübel U., Witte W. spa Typing of Staphylococcus aureus as a Frontline Tool in Epidemiological Typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46:574–581. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01599-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krupa P., Bystroń J., Podkowik M., Empel J., Mroczkowska A., Bania J. Population Structure and Oxacillin Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus from Pigs and Pork Meat in South-West of Poland. BioMed Res. Int. 2015;2015:141475. doi: 10.1155/2015/141475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nulens E., Stobberingh E.E., van Dessel H., Sebastian S., van Tiel F.H., Beisser P.S., Deurenberg R.H. Molecular Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Isolates Collected in a Dutch University Hospital between 1999 and 2006. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46:2438–2441. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00808-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Omuse G., Van Zyl K.N., Hoek K., Abdulgader S., Kariuki S., Whitelaw A., Revathi G. Molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from various healthcare institutions in Nairobi, Kenya: A cross sectional study. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2016;15:51. doi: 10.1186/s12941-016-0171-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Papadopoulos P., Papadopoulos T., Angelidis A.S., Kotzamanidis C., Zdragas A., Papa A., Filioussis G., Sergelidis D. Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from dairy industries in north-central and north-eastern Greece. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019;291:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nurjadi D., Fleck R., Lindner A., Schäfer J., Gertler M., Mueller A., Lagler H., Van Genderen P.J., Caumes E., Boutin S., et al. Import of community-associated, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to Europe through skin and soft-tissue infection in intercontinental travellers, 2011–2016. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019;25:739–746. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singh-Moodley A., Lowe M., Mogokotleng R., Perovic O. Diversity of SCCmec elements and spa types in South African Staphylococcus aureus mecA-positive blood culture isolates. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020;20:816. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05547-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tenover F.C., Tickler I.A., Goering R.V., Kreiswirth B.N., Mediavilla J.R., Persing D.H. Characterization of Nasal and Blood Culture Isolates of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Patients in United States Hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1324–1330. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05804-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tegegne H.A., Koláčková I., Florianová M., Wattiau P., Gelbíčová T., Boland C., Madec J.-Y., Haenni M., Karpíšková R. Genomic Insights into Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus spa Type t899 Isolates Belonging to Different Sequence Types. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021;87:e01994-20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01994-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Battisti A., Franco A., Merialdi G., Hasman H., Iurescia M., Lorenzetti R., Feltrin F., Zini M., Aarestrup F. Heterogeneity among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Italian pig finishing holdings. Vet. Microbiol. 2010;142:361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Köck R., Schaumburg F., Mellmann A., Köksal M., Jurke A., Becker K., Friedrich A.W. Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) as Causes of Human Infection and Colonization in Germany. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e55040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pirolo M., Gioffrè A., Visaggio D., Gherardi M., Pavia G., Samele P., Ciambrone L., Di Natale R., Spatari G., Casalinuovo F., et al. Prevalence, molecular epidemiology, and antimicrobial resistance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from swine in southern Italy. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:51. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1422-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schulz J., Boklund A., Toft N., Halasa T. Drivers for Livestock-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Spread Among Danish Pig Herds—A Simulation Study. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:16962. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34951-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tegegne H.A., Koláčková I., Karpíšková R. Diversity of livestock associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2017;10:929–931. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.CARD The Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. [(accessed on 20 March 2021)]. Available online: https://card.mcmaster.ca/home.

- 77.Zhang L., Gao J., Barkema H.W., Ali T., Liu G., Deng Y., Naushad S., Kastelic J.P., Han B. Virulence gene profiles: Alpha-hemolysin and clonal diversity in Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bovine clinical mastitis in China. BMC Vet. Res. 2018;14:63. doi: 10.1186/s12917-018-1374-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pomorska K., Jakubu V., Malisova L., Fridrichova M., Musilek M., Zemlickova H. Antibiotic Resistance, spa Typing and Clonal Analysis of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Isolates from Blood of Patients Hospitalized in the Czech Republic. Antibiotics. 2021;10:395. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10040395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sato T., Usui M., Motoya T., Sugiyama T., Tamura Y. Characterisation of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST97 and ST5 isolated from pigs in Japan. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2015;3:283–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.O’Brien A.M., Hanson B.M., Farina S.A., Wu J.Y., Simmering J., Wardyn S.E., Forshey B.M., Kulick M.E., Wallinga D.B., Smith T.C. MRSA in Conventional and Alternative Retail Pork Products. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Antonios Z., Theofilos P., Ioannis M., Georgios S., Georgios V., Evridiki B., Loukia E., Kyriaki M., Athanasios A., Vasiliki L. Prevalence, genetic diversity, and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bulk tank milk from Greek traditional ovine farms. Small Rumin. Res. 2015;125:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2015.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hookey J.V., Richardson J.F., Cookson B.D. Molecular Typing of Staphylococcus aureus Based on PCR Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism and DNA Sequence Analysis of the Coagulase Gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998;36:1083–1089. doi: 10.1128/JCM.36.4.1083-1089.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sudagidan M., Aydin A. Screening virulence properties of staphylococci isolated from meat and meat products. Wien. Tierarztl. Mon. 2009;96:128–134. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Løvseth A., Loncarevic S., Berdal K.G. Modified Multiplex PCR Method for Detection of Pyrogenic Exotoxin Genes in Staphylococcal Isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:3869–3872. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3869-3872.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stegger M., Andersen P., Kearns A., Pichon B., Holmes M., Edwards G., Laurent F., Teale C., Skov R., Larsen A. Rapid detection, differentiation and typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus harbouring either mecA or the new mecA homologue mecALGA251. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012;18:395–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Patel J.B. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 30th ed. CLSI Supplement M100; Berwyn, PA, USA: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Magiorakos A.-P., Srinivasan A., Carey R.B., Carmeli Y., Falagas M.E., Giske C.G., Harbarth S., Hindler J.F., Kahlmeter G., Olsson-Liljequist B., et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012;18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang W., Liu F., Baloch Z., Zhang C.S., Ma K., Peng Z.X., Yan S.F., Hu Y.J., Gan X., Dong Y.P., et al. Genotypic Characterization of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Pigs and Retail Foods in China. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2017;30:570–580. doi: 10.3967/bes2017.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Borges S., Silva J., Teixeira P.M.L. Survival and biofilm formation by Group B streptococci in simulated vaginal fluid at different pHs. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2011;101:677–682. doi: 10.1007/s10482-011-9666-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McDougal L.K., Steward C.D., Killgore G.E., Chaitram J.M., McAllister S.K., Tenover F.C. Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis Typing of Oxacillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from the United States: Establishing a National Database. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003;41:5113–5120. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5113-5120.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Aires-De-Sousa M., Boye K., De Lencastre H., Deplano A., Enright M.C., Etienne J., Friedrich A., Harmsen D., Holmes A., Huijsdens X., et al. High Interlaboratory Reproducibility of DNA Sequence-Based Typing of Bacteria in a Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:619–621. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.619-621.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Harmsen D., Claus H., Witte W., Rothgänger J., Claus H., Turnwald D., Vogel U. Typing of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a University Hospital Setting by Using Novel Software for spa Repeat Determination and Database Management. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003;41:5442–5448. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5442-5448.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jolley K.A., Bray J.E., Maiden M.C.J. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:124. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bortolaia V., Kaas R.S., Ruppe E., Roberts M.C., Schwarz S., Cattoir V., Philippon A., Allesoe R.L., Rebelo A.R., Florensa A.F., et al. ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020;75:3491–3500. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Alcock B.P., Raphenya A.R., Lau T.T.Y., Tsang K.K., Bouchard M., Edalatmand A., Huynh W., Nguyen A.-L.V., Cheng A.A., Liu S., et al. CARD 2020: Antibiotic resistome surveillance with the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D517–D525. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Carattoli A., Zankari E., García-Fernández A., Voldby Larsen M., Lund O., Villa L., Møller Aarestrup F., Hasman H. In Silico Detection and Typing of Plasmids. Antimicrob using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.