Abstract

The effect of Bordetella bronchiseptica infection on the viability of murine macrophage-like cells and on primary porcine alveolar macrophages was investigated. The bacterium was shown to be cytotoxic for both cell types, particularly where tight cell-to-cell contacts were established. In addition, bvg mutants were poorly cytotoxic for the eukaryotic cells, while a prn mutant was significantly less toxic than wild-type bacteria. B. bronchiseptica-mediated cytotoxicity was inhibited in the presence of cytochalasin D or cycloheximide, an inhibitor of microfilament-dependent phagocytosis or de novo eukaryotic protein synthesis, respectively. The mechanism of eukaryotic cell death was examined, and cell death was found to occur primarily through a necrotic pathway, although a small proportion of the population underwent apoptosis.

Bordetella bronchiseptica is a pathogen of both domestic and farm animals and an opportunistic pathogen in immunocompromised humans (17). The bacterium colonizes the respiratory tract and is thought to preferentially adhere to ciliated epithelial cells and possibly to alveolar macrophages (39). Like its close relative Bordetella pertussis, the causative agent of whooping cough, B. bronchiseptica produces an array of virulence factors whose expression, in both species, is in general controlled by the bvgAS operon in response to environmental stimuli (1). These factors include toxins such as adenylate cyclase toxin (ACT) and dermonecrotic toxin and adhesins such as fimbriae, filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), and pertactin. The latter is an immunogenic surface protein with apparent molecular masses of 68 and 69 kDa in B. bronchiseptica and B. pertussis, respectively (5, 30). P69/pertactin has been shown to be a protective antigen against B. pertussis infections in mice and is a component of acellular vaccines against whooping cough (16, 36), and P68/pertactin protects against B. bronchiseptica-mediated atrophic rhinitis in animals (37, 38). While P69/pertactin is known to promote adhesion of B. pertussis to eukaryotic cells, possibly via an RGD tripeptide sequence (9, 28, 29), the role of P68/pertactin in adhesion of B. bronchiseptica to eukaryotic cells remains to be characterized.

Until relatively recently, B. bronchiseptica was considered to be an exclusively extracellular pathogen, but a number of studies have now demonstrated intracellular invasion or intracellular persistence of the bacterium in a wide variety of eukaryotic cells, including professional phagocytes (3, 14, 21, 23, 41, 42). It has been suggested that this is a bvg-independent process, as bvg mutants survived in equal numbers to or greater numbers than their wild-type parent (3, 21, 42). Few of the factors involved in these processes have been identified, although mutants deficient in urease or acid phosphatase synthesis (6, 30, 32) or motility (47) are less able to survive intracellularly and mutants deficient in bvg adhere less efficiently (21). B. pertussis has also been recovered from the intracellular milieu in a number of studies, but this appears to require a Bvg+ phenotype with the bacteria unable to persist for extended periods (11, 15, 27, 40). Recently, a cytotoxic effect, dependent on environmental modulation of B. bronchiseptica gene expression, has been reported for an epithelial cell line infected with the bacterium (45). In addition, B. pertussis-mediated apoptosis of macrophages has been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo and is mediated by ACT (19, 24, 25). In this study, we have examined the interaction of B. bronchiseptica with a murine macrophage-like cell line and with porcine alveolar macrophages (PAM) and have determined that the bacterium is cytotoxic for mononuclear phagocytic cells. Furthermore, we show that cell death occurs both by necrosis and by apoptosis but that a significant proportion of the population remains viable after infection. Cytotoxicity was also found to be bvg dependent and to involve pertactin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and tissue culture.

B. bronchiseptica strains were grown on Bordet-Gengou agar plates supplemented with 12% (vol/vol) sheep blood and streptomycin and/or chloramphenicol, as appropriate. BBC17 was isolated in this laboratory and is a spontaneous streptomycin-resistant mutant of CN7531, which was isolated from a pig with atrophic rhinitis (30). CN7531 is also the strain from which the prn gene was cloned and sequenced (30). BRD866 and GVB39 are prn and bvgAS strains, respectively, of BBC17. BRD866 was constructed as follows. A 1.8-kb PstI internal fragment of the B. bronchiseptica prn gene was excised from the cosmid pBD844 (30) and cloned into pUC18 to give pBD865. This was then digested with ClaI, and, after end filling with Klenow fragment, it was ligated alongside a blunt-ended 0.7-kb cat (Cmr) cassette. The prn::cat cassette was recovered from the resulting plasmid, pBD866, by digestion with BamHI and HindIII and cloned into the similarly digested suicide vector pRTP1 (44) to generate pBD878. The suicide plasmid used to generate GVB39 was constructed by a similar strategy. A 2.7-kb EcoRI fragment of B. pertussis chromosomal DNA encoding all of bvgA and about half of bvgS was cloned into pUC18. This construct was digested with StuI (which cuts in the 5′ end of bvgS), and the ends were filled with Klenow fragment and ligated to the cat cassette, described above, to give plasmid pBD805. The inactivated bvg locus was recovered by digestion with BamHI and HindIII and ligated into identically digested pRTP1 to yield pBD901. Both pBD878 and pBD901 were conjugated independently into BBC17 by using Escherichia coli SM10λpir, and strains in which allelic exchange had taken place were selected by plating on medium containing chloramphenicol and streptomycin. Southern blot analysis was carried out to confirm that allelic replacement had occurred (data not shown). BB7866 (33) is a spontaneous bvgS strain of a human wild-type isolate, BB7865 (33), and GVB184 is BB7866 carrying PtacP68/pertactin on pBBR1MCS (26).

Expression of P68/pertactin and FHA in whole-cell lysates of all strains was analyzed by Western blotting with the pertactin-specific monoclonal antibody BB05 (34) and rabbit polyclonal anti-B. pertussis FHA, respectively. P68/pertactin was expressed in BBC17, BB7865, and GVB184 (at 60% of that of wild-type B. bronchiseptica) and was absent in BRD866 (prn), GVB39 (bvg), and BB7866 (bvg) (data not shown). FHA was expressed in BBC17, BRD866 (prn), and BB7865 and was not expressed in GVB39 (bvg), BB7866 (bvg), and GVB184 (data not shown). ACT activity was assayed in all strains and was produced at around the same levels in BBC17, BRD866 (prn), and BB7865 and was not expressed in GVB39 (bvg), BB7866 (bvg), and GVB184 (19a). The murine macrophage-like cell line RAW264.7 and PAM were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Gibco BRL Life Sciences, Paisley, United Kingdom) supplemented with 10% Myoclone Super Plus fetal calf serum and 2 mM glutamine in 5% CO2 at 37°C. PAM were collected by lavaging pig lungs with 200 ml of room temperature (RT) DMEM three times. The pooled cells were washed twice with DMEM and pelleted by centrifugation for 5 min at 110 × g. They were then resuspended in 500 ml of ACK erythrocyte lysis buffer and incubated for 10 min at RT. After harvesting by centrifugation for 5 min at 110 × g, the cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion and were seeded at a concentration of 106 cells/ml in DMEM supplemented with 10 μg of gentamicin per ml.

LDH assay.

The CytoTox nonradioactive cytotoxicity assay (Promega, Southampton, United Kingdom) was used to quantitate cytosolic lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release as an indicator of cell viability, as recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, RAW264.7 cells were seeded in 96-well trays at a concentration of 106 cells/ml 24 h prior to use. Where appropriate, cells were incubated with cytochalasin D (CD) (0.5 μg/ml) or cycloheximide (CH) (100 μg/ml) for 1 h prior to infection. CD and CH were kept in the medium throughout infections. Suspensions of bacteria prepared from 18-h-old Bordet-Gengou lawns were prepared in prewarmed (37°C) DMEM. The cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 500:1 or 100:1, and where appropriate, trays were centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min after infection. Following an incubation period of 1, 2, or 4 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, the plates were centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min, 50-μl aliquots of medium were transferred to a fresh tray, and 50 μl of substrate mix was added to each well. After a 30-min incubation at RT in the dark, 50 μl of stop solution was added to each well and the absorbance was recorded at 490 nm. Positive controls in each assay were represented by wells in which cells were lysed by the addition of Triton X-100 (0.8%). Each assay was carried out at least twice in triplicate. Results were analyzed by a one-way analysis of variance.

Nucleosome ELISA.

A Nucleosome enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Calbiochem, Nottingham, United Kingdom), which employs DNA affinity-mediated capture of free nucleosomes, was used to quantitate apoptotic cells in vitro. Briefly, RAW264.7 cells or freshly harvested PAM were seeded in 96-well trays at a concentration of 106 cells/ml 24 h prior to use. Positive control cells were pretreated with 0.5 μg of actinomycin D (AD) per ml for 4 or 18 h to induce apoptosis. The cells were infected at an MOI of 100:1 with suspensions of bacteria as described above, and where appropriate, plates were centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min after infection. After an incubation period of 2 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, the plates were centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min. The medium was removed, and the cells were resuspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer per well and were disrupted by vigorous pipetting. The plate was incubated on ice for 30 min before being centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the lysis buffer was removed to a fresh 96-well tray. After at least 18 h at −20°C, the lysates were thawed at RT and transferred into wells of the Nucleosome ELISA microtiter plate supplied by the manufacturer. Following incubation for 3 h at RT, the wells were washed three times with 1× wash buffer and 100 μl of detector antibody was added to each well. After incubation for 1 h at RT, the wells were again washed three times with 1× wash buffer. One hundred microliters of freshly filtered 1× streptavidin conjugate (streptavidin-linked horseradish peroxidase conjugate) was added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 30 min at RT. Wells were washed twice with 1× wash buffer and flooded once with distilled H2O, and 100 μl of RT substrate solution was added to each well. After 30 min of incubation at RT in the dark, 100 μl of stop solution was added to each well. The absorbance was read with a spectrophotometric plate reader at 450 nm. Each assay was carried out at least twice in triplicate.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of infected cells.

RAW264.7 cells were seeded in 24-well trays at a concentration of 106 cells/ml 24 h prior to use. The cells were infected at an MOI of 100:1 with suspensions of bacteria prepared as described above. Where appropriate, cells were treated with CD or AD as described above. After an incubation period of 2 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, the cells were washed three times with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 1 ml of cold 1× Hanks balanced salt solution supplemented with 2.5 mM CaCl2. Cells (100 μl) were stained with 10 μl of fluorescein-conjugated annexin V (AV-fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]) (R&D Diagnostics, Abingdon, United Kingdom) at a concentration of 10 μg/ml. AV is a phospholipid binding protein with a selective affinity for negatively charged phospholipids and a specificity for phosphotidylserine (46). The latter is exposed on the outer leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane of apoptotic cells as a consequence of loss of cell membrane phospholipid asymmetry and thus acts as a marker of early-phase apoptosis. After incubation at RT for 15 min in the dark, 400 μl of 1× Hanks balanced salt solution supplemented with 2.5 mM CaCl2 was added and analysis was carried out within 1 h on an EPICS-XL flow cytometer (Coulter). Seven thousand events were acquired.

Fluorescence microscopy.

RAW264.7 cells were seeded in four-well plastic chamber slides (Lab-Tek, Leicester, United Kingdom) at a concentration of 106 cells/ml 24 h prior to use in phenol red-free DMEM. The cells were infected at an MOI of 100:1 with suspensions of bacteria as described above, and after a 1-h incubation, infected cells were washed three times with PBS. Staining with fluorochromes was carried out in 1 ml of phenol red-free DMEM. Cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) (20 mM) and AV-FITC or PI and SYTO-9 (3.34 μM) (Molecular Probes Europe BV, Leiden, The Netherlands) for 15 min at RT in the dark. AV-FITC, as discussed above, stains the membranes of apoptotic cells, while PI is taken up by necrotic cells. Thus, apoptotic and necrotic cells can be distinguished. SYTO-9 is a green fluorochrome which, in the presence of PI, stains cells with intact membranes, and therefore, these two fluorochromes can be used to distinguish between viable and nonviable cells. Slides were washed twice with PBS before being imaged on a Leica DMLB fluorescence microscope with a standard long pass fluorescein filter set and LabSpectrum software (Vysis, London, United Kingdom).

RESULTS

B. bronchiseptica is cytotoxic for macrophages, and toxicity is mediated by pertactin and other bvg-regulated factors.

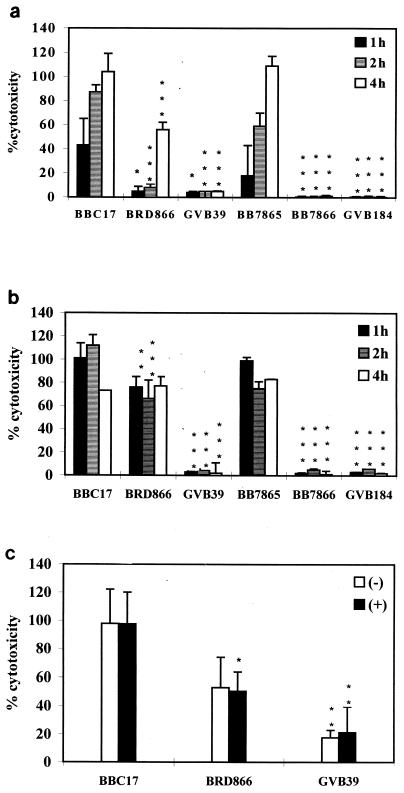

RAW264.7 cells were infected with different B. bronchiseptica strains at an MOI of 100:1 and were incubated for 1, 2, or 4 h. As is evident from Fig. 1a, wild-type strains BBC17 and BB7865 exerted a significant cytotoxic effect which increased with time. In contrast, the bvg mutants GVB39 and BB7865 caused very little cell damage, even with extended incubation. The prn mutant BRD866 behaved similarly to the bvg mutants at the 1- and 2-h points, but at 4 h, it had induced LDH release considerably greater than that of GVB39 (bvg) but still significantly less than that of BBC17 at this time point. The amount of cytotoxicity (assessed by LDH release) by BRD866 at 4 h was similar to that of the wild-type strain at 1 h. Expression of pertactin in a bvg strain (GVB184) did not enhance its cytotoxicity. The difference in the cytotoxicity of the different strains is not due to differences in their growth rate in DMEM (data not shown). The effect of close cell-to-cell contacts was examined by centrifuging the bacteria onto the monolayer directly after infection. Figure 1b shows that the two wild-type strains and the pertactin mutant were all highly cytotoxic for the cell line in these circumstances, regardless of the length of incubation, although BRD866 (prn) was significantly less cytotoxic than its wild-type parent (BBC17) at 1 and 2 h. As before, the bvg mutants were mildly cytotoxic and the presence of pertactin in a bvg-negative background was not sufficient to induce cytotoxicity. RAW264.7 cells were also infected at MOI of 1:1, 10:1, and 500:1 with all strains used previously. At an MOI of 500:1, levels of toxicity increased, while at MOI of 1:1 and 10:1, levels of toxicity decreased in comparison to those observed at an MOI of 100:1. However, the same patterns of cytotoxicity were observed as when the cells were infected at an MOI of 100:1 (data not shown). In another experiment, freshly harvested PAM were infected with B. bronchiseptica for 2 h, and as can be seen in Fig. 1c, these cells appeared to be generally more sensitive to infection, as both BRD866 (prn) and GVB39 (bvg) induced around fourfold-higher levels of LDH release than those which occurred in the RAW264.7 cells at 2 h postinfection. Also, levels of LDH release were around the same regardless of whether the bacteria were centrifuged onto the monolayer. This may suggest that cells recovered from the in vivo milieu are more susceptible to B. bronchiseptica infection.

FIG. 1.

Cytotoxic effects of B. bronchiseptica on macrophages. Macrophages were infected at an MOI of 100:1, and LDH assays were carried out at 1, 2, or 4 h postinfection with RAW264.7 cells (a); 1, 2, or 4 h postinfection with RAW264.7 cells which were centrifuged for 5 min at 400 × g immediately after infection (b); and 2 h postinfection with PAM and without (−) or with (+) centrifugation (c). The bars represent the mean percent release of LDH from three wells in comparison with the positive control wells, and the error bars represent the standard deviations. Statistical significance of strain-dependent cytotoxicity is shown as P < 0.001 (∗∗∗), P < 0.01 (∗∗), and P < 0.05 (∗). BRD866 and GVB39 were compared to BBC17 at each time point, and BB7866 and GVB184 were compared to BB7865 at each time point.

CD and CH inhibit B. bronchiseptica-induced cytotoxicity.

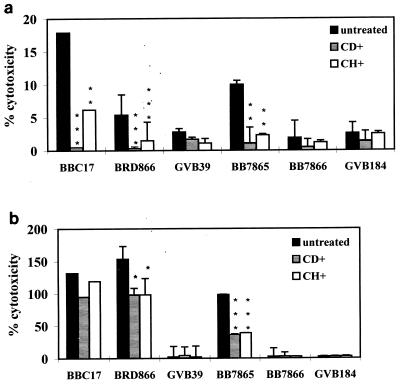

B. bronchiseptica can enter both phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells by a microfilament-dependent process (14, 20), and therefore, levels of cytotoxicity were characterized in RAW264.7 cells which were pretreated with CD before infection. Figure 2a shows that cytoxicity was significantly reduced at 1 h postinfection, and the LDH release fell by ∼90% in cells infected with BBC17, BB7865, and BRD866 (prn). At 4 h postinfection (Fig. 2b), addition of CD did not result in a significant decrease in cytotoxicity of strain BBC17. LDH release from cells infected with BB7865 and BRD866 (prn) remained lower in CD-treated cells than in untreated cells. The effect of pretreatment with CH was also examined, as it has been shown to inhibit pertactin-mediated adhesion (9). As seen with CD treatment, CH reduced B. bronchiseptica-mediated cytotoxicity at the 1- and 4-h points (this was not significant for BBC17 at 4 h). The same effects as those described above, in the presence of CD and CH, were observed when bacteria were centrifuged onto monolayers or at a higher MOI of 500:1 (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Inhibition of cytotoxicity by CD and CH. RAW264.7 cells were infected at an MOI of 100:1, and LDH assays were carried out at 1 (a) and 4 (b) h postinfection in the presence and absence of CD and CH. The bars represent the mean percent release of LDH from three wells in comparison with the positive control wells, and the error bars represent the standard deviations. Statistical significance of inhibition of cytotoxicity in each strain is shown as P < 0.001 (∗∗∗), P < 0.01 (∗∗), and P < 0.05 (∗). BRD866 and GVB39 were compared to BBC17 at each time point, and BB7866 and GVB184 were compared to BB7865 at each time point.

B. bronchiseptica induces apoptosis in macrophages.

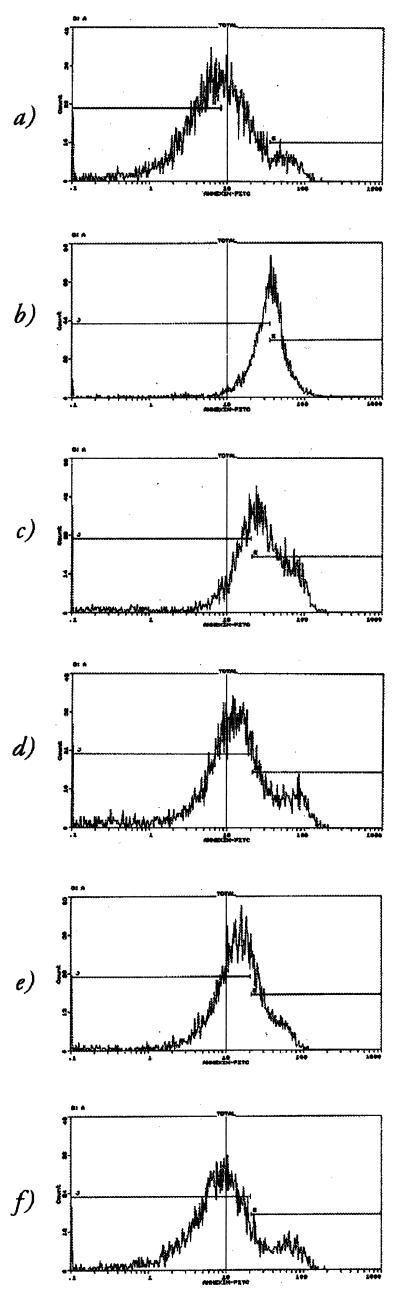

As B. bronchiseptica was clearly cytotoxic for macrophages, the effect was further characterized to define if toxicity was due to programmed cell death. After infection, RAW264.7 cells were labelled with AV-FITC and analyzed by FACS. A clear shift in the proportion of apoptotic cells in the population was evident in the presence of BBC17 (Fig. 3c), as opposed to uninfected cells (Fig. 3a), and to around the same degree as cells treated with AD for 18 h (Fig. 3b). This could be inhibited in cells pretreated with CD (Fig. 3d). BRD866 (prn) was also able to increase the proportion of apoptotic cells (Fig. 3e) but not to the same extent as seen with the wild-type infection, while GVB39 (bvg) had little effect (Fig. 3f). The effect of CD on uninfected cells was minimal, as a barely discernible shift was observed in its presence (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

FACS analysis of B. bronchiseptica-induced apoptosis. RAW264.7 cells were stained with AV-FITC and analyzed on an EPICS-XL flow cytometer. (a and b) Profiles of uninfected cells in the absence (a) and presence (b) of AD. (c to f) Profiles of cells which were infected with B. bronchiseptica for 2 h at an MOI of 100:1: BBC17 in the absence of CD (c), BBC17 in the presence of CD (d), BRD866 (e), and GVB39 (f). The cursors represent populations of differing fluorescent intensities.

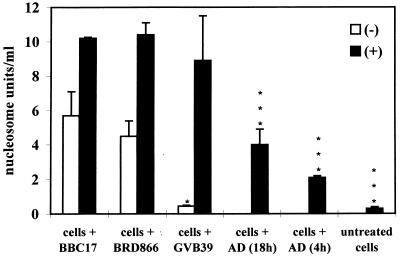

To confirm that B. bronchiseptica induces apoptosis in macrophages, infected RAW264.7 cells and PAM were assayed for release of free nucleosomes, a phenomenon associated with DNA laddering and late-stage apoptosis. In the case of the RAW264.7 cells, only BBC17 gave rise to a significant positive result (6 nucleosome units/ml) in comparison to uninfected cells (0.2 nucleosome units/ml) and only where bacteria were centrifuged onto the monolayer (data not shown). When PAM were infected, both BBC17 and BRD866 (prn) caused nucleosomes to be released (Fig. 4). In the presence of GVB39 (bvg), centrifugation was required before a significant positive result was obtained.

FIG. 4.

Nucleosome release by B. bronchiseptica-infected macrophages. PAM were infected at an MOI of 100:1, and Nucleosome ELISAs were carried out at 2 h postinfection without (−) or with (+) centrifugation. Nucleosome release in uninfected cells treated with AD for 4 or 18 h was also examined. The bars represent the mean counts from three wells, and the error bars represent the standard deviations. Statistical significance of strain-dependent nucleosome release is shown as P < 0.001 (∗∗∗), P < 0.01 (∗∗), and P < 0.05 (∗). BRD866 and GVB39 were compared to BBC17.

The major proportion of the cell population remains viable after infection with B. bronchiseptica.

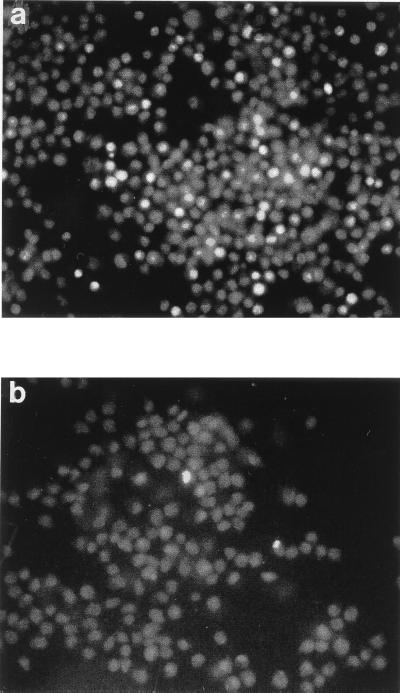

While B. bronchiseptica clearly induced apoptosis in macrophages, it was not known which proportion of the total eukaryotic cell population underwent programmed cell death or if any of the population died via a necrotic pathway. RAW264.7 cells, which had been infected for 1 h, were therefore stained with PI and AV-FITC or with PI and SYTO-9, which enable viable, necrotic, and apoptotic populations of cells to be distinguished and quantified. Examination of the cells by fluorescence microscopy showed that, after infection with BBC17, the major proportion of cells in the population remained viable. Those cells which were stained with PI and SYTO-9 but which had taken up PI constituted only around 10 to 20% of the population (Fig. 5a). This is generally in agreement with the results obtained from LDH assays carried out with RAW264.7 cells infected with BBC17 for 1 h (Fig. 1a and b), where around 20 to 40% cytotoxicity was observed. Of those cells which were stained with PI and AV-FITC, around 1% of cells stained with AV-FITC (Fig. 5b).

FIG. 5.

Quantification of live, necrotic, and apoptotic cells by fluorescence microscopy. RAW264.7 cells were infected with BBC17 at an MOI of 100:1. At 1 h postinfection, they were stained with PI and SYTO-9 (a) or PI and AV-FITC (b) and were imaged with a Leica DMLB fluorescence microscope at a magnification of ×200. Grey-scale representative images of a red-green exposure (a) and a green exposure (b) are shown. The highly fluorescent cells are in cells stained with PI (a) and cells stained with AV-FITC (b).

DISCUSSION

B. bronchiseptica has been shown to adhere to, invade, or persist intracellularly in eukaryotic cell lines in a variety of in vitro studies. In contrast, B. pertussis appears unable to survive intracellularly for prolonged periods, and the bacterium is known to induce apoptosis in macrophages both in vitro and in vivo (19, 24, 25). Cell death in this instance is mediated by ACT, and neither pertussis toxin nor pertactin/P69 is a prerequisite (24). There is little data detailing B. bronchiseptica-mediated eukaryotic cell death, although a cytotoxic effect in epithelial cells has been described elsewhere (45), and it has been suggested that viability of macrophages decreases on extended exposure to these bacteria (3).

As B. bronchiseptica is known to persist within cultured and primary phagocytes, and as its close relative B. pertussis is toxic for these cells, we investigated the capacity of the former to promote cell death in macrophages. By using plasma membrane integrity as a marker of macrophage viability, it was apparent that both human and porcine wild-type isolates of B. bronchiseptica were toxic for these cells (Fig. 1a and 2a). This effect was exacerbated by centrifuging the bacteria onto the cells (Fig. 1b), suggesting that the process enhanced the number of contacts between B. bronchiseptica and the eukaryotic cells. Also, the fact that centrifugation overcame the reduced cytotoxicity of the prn-negative mutant suggests that the role of pertactin is to promote stable adhesion of B. bronchiseptica or to bring it into close apposition to the macrophages. Therefore, one would expect that pertactin would not be cytotoxic itself, and this is supported by the finding that expression of pertactin does not augment the cytotoxicity of a bvg mutant strain, even when centrifugation is employed. Also, pertactin has been used as a component of acellular pertussis vaccines in humans without recorded side effects. Levels of cytotoxicity increased with time possibly because there was an increase in bacterial numbers or because there was an increase in synthesis of a cytotoxic factor(s). However, little bacterial-mediated cytotoxicity, as assayed by LDH release, occurred in the presence of bvg mutants which do not produce dedicated virulence factors, including toxins and adhesins. This is in agreement with the morphological effects described by van den Akker (45), who showed that Bvg− phase variants of B. bronchiseptica are nontoxic for epithelial cells, and with the data showing that bvg mutants of B. pertussis and B. bronchiseptica are nontoxic for macrophages (3, 23). It should be noted, though, that the bvg mutants are not completely nontoxic for macrophages, as they were able to induce nuclesome release in PAM when centrifuged onto the monolayer. Also, BRD866, a mutant deficient in the production of P68/pertactin, induced low levels of cytotoxicity in the short term (1 to 2 h) but levels at around that induced by wild type in the longer term (4 h) (Fig. 1a). This is reminiscent of the finding that no significant difference was found in levels of cytotoxicity induced by wild type or a pertactin mutant of B. pertussis at 4 h postinfection (24). However, a strain also used in that study, which was deficient in both prn and fha, was less efficient at promoting DNA fragmentation in macrophages but had less ACT activity than its parent. This may suggest that other adhesins, such as FHA, are able to promote binding of the bacteria to macrophages in a compensatory time-dependent manner in the absence of pertactin, which, in turn, leads to increased cytotoxicity. Alternatively, P68/pertactin may act as a chaperon for correct FHA function in B. bronchiseptica, as has been suggested by Arico et al. (2) for P69/pertactin in B. pertussis. In that study, adhesion of B. pertussis to CHO cells was found to be time dependent, to absolutely require FHA, and to be influenced significantly by P69/pertactin. FHA has also been recently shown to be required and sufficient for mediating adherence of B. bronchiseptica to rat lung epithelial cells, but while required, it is not sufficient for tracheal colonization (8). As GVB184, a bvg mutant complemented only with P68/pertactin, behaves in a similar manner as noncomplemented bvg mutants, this may again suggest that cytotoxic activity is dependent on effective binding of the bacteria via multiple adhesins. The same effect was reported for bvg mutant B. pertussis (9). The viability of PAM was more affected by B. bronchiseptica (Fig. 1c) than was that of RAW264.7 cells, possibly because they are mature macrophages or because they are alveolar macrophages per se. However, again prn and bvg mutants were clearly less toxic than their wild-type parent. Our results and those for other bacteria that are intracellular pathogens but which can also cause apoptosis, such as Salmonella spp., are somewhat contradictory. That is, why do intracellular pathogens kill their host cell? It may be that they kill more mature, and potentially more bactericidal, macrophages preferentially, which increases their chances of entering a more friendly environment. This appears to be the case in our studies where PAM were more readily killed than RAW264.7 cells. Alternatively, B. bronchiseptica may invade macrophages merely to more efficiently kill them. However, this is in conflict with reports that B. bronchiseptica can persist for days inside cells. It is possible that the bacteria that persist within cells have adapted to live within cells by down regulating the expression of cytotoxic factors and possibly up regulating other genes. These hypotheses require further experiments before they can be confirmed or refuted.

CD inhibits internalization of B. bronchiseptica and Bordetella parapertussis by eukaryotic cells (10, 14, 20), presumably by blocking phagocytosis, but has been reported to have no effect on adherence of B. pertussis to CHO cells (35). Also, in a study examining the effects of B. pertussis-mediated apoptosis, while the kinetics of toxicity were slightly slower in the presence of CD, the bacteria were able to induce complete lysis of the macrophage population at 8 h postinfection (25). In this study, CD significantly inhibited the ability of B. bronchiseptica wild types and the prn mutant to induce cytotoxicity at 1 h postinfection (Fig. 2a). At 4 h postinfection, there was no significant difference in LDH release between CD-treated cells and untreated cells infected with the porcine isolate BBC17. However, it is possible that bacterial replication could have occurred by the 4-h point of the assay, causing toxic effects to be enhanced even in the presence of CD. In the presence of the human isolate BB7865 and the prn mutant BRD866, cytotoxic effects remained significantly lower than those induced in cells not treated with CD, although levels had increased from those observed at 1 h postinfection (Fig. 2b). Thus, it would appear that internalization of B. bronchiseptica profoundly enhances its ability to effect eukaryotic cell death but is not essential. The effects of CH treatment on cytotoxicity mirrored those seen with CD treatment, and as CH also inhibits P69/pertactin-mediated adhesion (9), it is possible that pertactin, which contains an RGD integrin-recognition motif, acts as a signalling molecule, resulting in the upregulation of receptors on the phagocytic cell surface. However, a recent report by Buckley et al. (4) has shown that RGD-containing peptides enter cells and directly induce activity of caspase-3, a proapoptotic protein. It would appear then that efficient adhesion, internalization, and production of a cytotoxic factor(s), possibly ACT, are the maximal conditions for B. bronchiseptica-mediated cell death. However, a recent paper has reported that a cyaA mutant of B. bronchiseptica is as cytotoxic for J774 macrophages as is its wild-type parent (22), but a cyaA mutant in which the type III secretion system was knocked out by a mutation in the bscN gene was significantly less toxic. Tracheal cytotoxin (7) and lipooligosaccharide (43) have also been described as having a toxic effect on polymorphonuclear leukocytes and thus may account for the degree of cytotoxicity of Bvg− B. bronchiseptica.

As a variety of pathogens have now been described as inducers of apoptosis, including B. pertussis, the ability of B. bronchiseptica to do so was examined by using markers for both early-stage and late-stage apoptosis. FACS analysis and ELISA-based histone detection (Fig. 3 and 4) clearly showed that B. bronchiseptica does induce apoptosis in murine macrophages, and as demonstrated in the LDH assays, cell death is reduced when macrophages are exposed to bacteria with a bvg- or prn-negative background. Quantification of the proportion of cells which had died via apoptosis was carried out by fluorescence microscopy, in order that the necrotic population, if any, could also be determined. Figure 5 shows that, while a small proportion of macrophages stained with the apoptotic marker AV-FITC, the majority of nonviable cells had taken up PI. Therefore, it would appear that B. bronchiseptica is able to trigger cell death by more than one mechanism. This phenomenon has also been described for Escherichia coli (enteroaggregative E. coli strains) (12) and for Shigella flexneri (13), but in these instances, the type of cell death appears to be dependent on the macrophage derivation. It has also been recently suggested that Salmonella typhimurium, which survives within macrophages and can cause them to apoptose, also induces a necrotic-type death (31). As discussed by Fernandez-Prada et al. (13) and Gordon et al. (18), there are extensive heterogeneity and diversity within the macrophage population, and one could presume that this would influence the route of bacterium-mediated cell death. Further study will be required to define the extent of B. bronchiseptica-mediated cytotoxicity in vivo and to identify the mechanisms and factors involved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nicole Guiso for carrying out ACT assays and Linda Andrews for assistance with FACS analysis.

This work received financial support from the Wellcome Trust, research grant no. 045078.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arico B, Scariato V, Monack D M, Falkow S, Rappuoli R. Structural and genetic analysis of the bvg-locus in Bordetella species. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:481–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arico B, Nuti S, Scarlato V, Rappuoli R. Adhesion of Bordetella pertussis to eukaryotic cells requires a time-dependent export and maturation of filamentous hemagglutinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9204–9208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banemann A, Gross R. Phase variation affects long-term survival of Bordetella bronchiseptica in professional phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3469–3473. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3469-3473.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckley C, Pilling D, Henriquez N V, Parsonage G, Threlfall K, Scheel-Toellner D, Simmons D L, Akbar A N, Lord J M, Salmon M. RGD peptides induce apoptosis by direct caspase-3 activation. Nature. 1999;397:534–539. doi: 10.1038/17409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charles I G, Dougan G, Pickard D, Chatfield S N, Smith P, Novotny P, Morrisey P M, Fairweather N F. Molecular cloning and characterization of a protective outer membrane protein P69/pertactin from Bordetella pertussis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;86:3554–3558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chhatwal G S, Walker M J, Yan H, Timmis K N, Guzman C A. Temperature dependent expression of an acid phosphatase by Bordetella bronchiseptica: role in intracellular survival. Microb Pathog. 1997;22:257–264. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cookson B T, Goldman E. Tracheal cytotoxin: a conserved virulence determinant of all Bordetella species. J Cell Biochem. 1987;11B:124–127. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cotter P A, Yuk M H, Mattoo S, Akerley B J, Boschwitz J, Relman D A, Miller J F. Filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella bronchiseptica is required for efficient establishment of tracheal colonization. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5921–5929. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5921-5929.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Everest P, Jingli L, Douce G, Charles I, De Azavedo J, Chatfield S, Dougan G, Roberts M. Role of the Bordetella pertussis P.69/pertactin protein and the P.69/pertactin RGD motif in the adherence to and invasion of mammalian cells. Microbiology. 1996;142:3261–3268. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-11-3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ewanowich C A, Sherburne R K, Man S F P, Peppler M S. Bordetella parapertussis invasion of HeLa229 cells and human respiratory cells in primary culture. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1240–1247. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1240-1247.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ewanowich C A, Sherburne R K, Man S F P, Peppler M S. Invasion of HeLa229 cells by virulent Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2698–2704. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.9.2698-2704.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez-Prada C, Tall B D, Elliott S E, Hoover D L, Nataro J P, Venkatesan M M. Hemolysin-positive enteroaggregative and cell-detaching Escherichia coli strains cause oncosis of human monocyte-derived macrophages and apoptosis of murine J774 cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3918–3924. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3918-3924.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Prada C, Hoover D L, Tall B D, Venkatesan M M. Human monocyte-derived macrophages infected with virulent Shigella flexneri in vitro undergo a rapid cytolytic event similar to oncosis but not apoptosis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1486–1496. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1486-1496.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forde C B, Parton R, Coote J G. Bioluminescence as a reporter of intracellular survival of Bordetella bronchiseptica in murine phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3198–3207. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3198-3207.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman R L, Nordensson K, Wilson L, Akporiaye E T, Yocum D E. Uptake and intracellular survival of Bordetella pertussis in human macrophages. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4578–4585. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4578-4585.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gamsin S, Chandler A. SmithKline Beecham's new acellular pertussis vaccine demonstrates enhanced efficacy in major NIAID studies. Press release. Philadelphia, Pa: SmithKline Beecham; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodnow R A. Biology of Bordetella bronchiseptica. Microbiol Rev. 1980;44:722–738. doi: 10.1128/mr.44.4.722-738.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon S, Fawson L, Rabinowitz S, Crocker R, Morris L, Perry V H. Antigen markers of macrophage differentiation in murine tissues. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;181:1–37. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77377-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gueirard P, Druilhe A, Pretolani M, Guiso N. Role of adenylate cyclase-hemolysin in alveolar macrophage apoptosis during Bordetella pertussis infection in vivo. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1718–1725. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1718-1725.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Guiso, N. Personal communication.

- 20.Guzman C A, Rohde M, Timmis K M. Mechanisms involved in the uptake of Bordetella bronchiseptica in mouse dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5538–5544. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5538-5544.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guzman C A, Rohde M, Bock M, Timmis K N. Invasion and intracellular survival of Bordetella bronchiseptica in mouse dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5528–5537. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5528-5537.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harvill E T, Cotter P A, Yuk M H, Miller J F. Probing the function of Bordetella bronchiseptica adenylate cyclase toxin by manipulating host immunity. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1493–1500. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1493-1500.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jungnitz H, West N P, Walker M J, Chhatwal G S, Guzman C A. A second two-component regulatory system of Bordetella bronchiseptica required for bacterial resistance to oxidative stress, production of acid phosphatase, and in vivo persistence. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4640–4650. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4640-4650.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khelef N, Guiso N. Induction of macrophage apoptosis by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase-hemolysin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;134:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khelef N, Zychlinsky A, Guiso N. Bordetella pertussis induces apoptosis in macrophages: role of adenylate cyclase-hemolysin. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4064–4071. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4064-4071.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kovach M E, Phillips R W, Elzer P H, Roop II R M, Peterson K M. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host-range cloning vector. BioTechniques. 1994;16:800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee C K, Roberts A L, Finn T M, Knapp S, Mekalanos J J. A new assay for invasion of HeLa229 cells by Bordetella pertussis: effects of inhibitors, phenotypic modulation, and genetic alterations. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2516–2522. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2516-2522.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leininger E, Ewanowich C A, Bhargava A, Peppler M S, Kenimer J G, Brennan M J. Comparative roles of the Arg-Gly-Asp sequence present in the Bordetella pertussis adhesins pertactin and filamentous hemagglutinin. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2380–2385. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2380-2385.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leininger E, Roberts M, Kenimer J G, Charles I G, Fairweather N, Novotny P, Brennan M J. Pertactin, an arg-gly-asp containing Bordetella pertussis surface protein that promotes adherence of mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:345–349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, Fairweather N F, Novotny P, Dougan G, Charles I G. Cloning, nucleotide sequence and heterologous expression of the protective outer-membrane protein P.68 pertactin from Bordetella bronchiseptica. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1697–1705. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-8-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindgren S W, Heffron W. To sting or be stung: bacteria-induced apoptosis. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:263–264. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)88832-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMillan D J, Shojaei M, Chhatwal G S, Guzman C A, Walker M J. Molecular analysis of the bvg-repressed urease of Bordetella bronchiseptica. Microb Pathog. 1996;21:379–394. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monack D M, Arico B, Rappuoli R, Falkow S. Phase variants of Bordetella bronchiseptica arise by spontaneous deletions in the vir locus. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1719–1728. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montaraz J A, Novotny P, Ivanyi J. Identification of a 68-kilodalton protective protein antigen from Bordetella bronchiseptica. Infect Immun. 1985;47:744–751. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.3.744-751.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mouallem M, Farfel Z, Hanski E. Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin: intoxication of host cells by bacterial invasion. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3759–3764. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3759-3764.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Novotny P, Chubb A P, Cownley K, Charles I G. Biologic and protective properties of the 69-kDa outer membrane protein of Bordetella pertussis: a novel formulation for an acellular pertussis vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:114–122. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Novotny P, Kobisch M, Cownley K, Chubb A P, Montaraz J A. Evaluation of Bordetella bronchiseptica vaccines in specific-pathogen-free piglets with bacterial cell surface antigens in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Infect Immun. 1985;50:190–198. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.1.190-198.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novotny P, Chubb A P, Cownley K, Montaraz J A. Adenylate cyclase activity of a 68,000-molecular-weight protein isolated from the outer membrane of Bordetella bronchiseptica. Infect Immun. 1985;50:199–206. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.1.199-206.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rappuoli R. Pathogenicity mechanisms of Bordetella. In: Dangl J L, editor. Bacterial pathogenesis of plants and animals: molecular and cellular mechanisms. Berlin, Germany: Springer Verlag; 1994. pp. 319–336. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts M, Fairweather N F, Leininger E, Pickard D, Hewlett E L, Robinson A, Hayward C, Dougan G, Charles J G. Construction and characterisation of Bordetella pertussis mutants lacking the vir-regulated P.69 outer membrane protein. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1393–1404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savelkoul P H M, Kremer B, Kosters J G, van der Zeijst B A M, Gaastra W. Invasion of HeLa cells by Bordetella bronchiseptica. Microb Pathog. 1993;14:161–168. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schipper H, Krohne G F, Gross R. Epithelial cell invasion and survival of Bordetella bronchiseptica. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3008–3011. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.3008-3011.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shahin R D, Hamel J, Leef M F, Brodeur B R. Analysis of protective and nonprotective monoclonal antibodies specific for Bordetella pertussis lipooligosaccharide. Infect Immun. 1994;62:722–725. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.722-725.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stibitz S, Black W, Falkow S. The construction of a cloning vector designed for gene replacement in Bordetella pertussis. Gene. 1986;50:133–137. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van den Akker W M R. Bordetella bronchiseptica has a BvgAS-controlled cytotoxic effect upon interaction with epithelial cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;156:239–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vermes I, Haanen C, Steffens-Nakken H, Reutelingsperger C. A novel assay for apoptosis. Flow cytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on early apoptotic cells using fluorescein labelled Annexin V. J Immunol Methods. 1995;184:39–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00072-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.West N P, Fitter J T, Jakubzik U, Rohde M, Guzman C A, Walker M J. Non-motile mini-transposon mutants of Bordetella bronchiseptica exhibit altered abilities to invade and survive in eukaryotic cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;146:263–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]