Abstract

Adolescents and young adults (15–24 yrs.) have poorer HIV clinical outcomes than adults. Despite this, there is minimal data on individual-level factors such as self-efficacy towards antiretroviral adherence among perinatally infected adolescents living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. Our study examined the interaction between antiretroviral treatment adherence self-efficacy and other psychosocial factors among adolescents receiving care in Nairobi, Kenya.

We enrolled perinatally infected Adolescent Living with HIV (ALWHIV) 16–19 yrs. who were accessing care routinely at the HIV clinic. We measured self-reported ART adherence (7-day recall) and defined optimal adherence as >95%, and conducted a regression analysis to identify independently associated factors. Mediation analysis explored interactions between the psychosocial variables.

We enrolled 82 ALWHIV median age 17 (IQR 16,18) who had been on ART for a median age of 11 yrs. (IQR 7,13). Sixty-four per cent (52) of the ALWHIV reported optimal adherence of >95%, and 15% reported missing doses for three or more months. After controlling for the other covariates, self-esteem, high viral load and an adherence level > 95% were significantly associated with adherence self-efficacy. Self-esteem was significantly associated with adherence self-efficacy and social support (p<0.001 and p=0.001), respectively. The paramed test indicated that the association between self-efficacy and adherence was mediated by self-esteem with a total effect of OR 6.93 (bootstrap 95% CI 1.99–24.14). Adherence self-efficacy was also mediated by self-esteem in developing adherence behavior. Interventions focused on increasing adherence among ALWHIV should include self-esteem building components.

Introduction

HIV is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among adolescents (10–19 yrs.) in Africa. Existing literature extensively describes non-modifiable factors associated with non-adherence in adolescents, which include age, gender, Berihun Assefa Dachew1, 2014, Nabukeera-Barungi et al., 2015), distance from the treatment centre (Getachew Arage1, 2014) and past traumatic events/stressors like loss of a family member (Nyandiko et al., 2006). However, there is little documentation on modifiable behavioural/psychosocial barriers. One of these critical modifiable factors includes ART adherence self-efficacy (defined as the extent or strength of one’s belief in one’s own ability to complete tasks and attain goals despite environmental and social barriers )(Bandura, 1977) (Farmer, Jarvis, Berent, & Corbett, 2001)(Sharma & Agarwala, 2015) is associated with improved adherence and better treatment outcomes (Firdu, Enquselassie, & Jerene, 2017), (Mueller, Alie, Jonas, Brown, & Sherr, 2011), (Johnson et al., 2007), (Adefolalu, Nkosi, Olorunju, & Masemola, 2014), (Aregbesola & Adeoye, 2018). While all adolescents living with HIV (ALWHIV) face the same difficulty during the developmental stage, data suggests adolescents presenting with behavioural HIV acquisition are uniquely different from those with perinatal acquired infection with regards to the persistent and cumulative psychological stressors experienced (Petersen et al., 2010) (Kasedde, Kapogiannis, McClure, & Luo, 2014). Transition by these ALWHIV to adult care aims at supporting them to continue ART adherence and to navigate the health systems during clinic appointment as independent individuals. Understanding factors that potentially produce long-term motivation towards adherence to ART and clinic attendance are crucial for establishing adolescent transition.

There is little data on the interaction between self-efficacy and factors such as perceived social support, the experience of HIV related stigma and self-esteem. (Lee & Hazra, 2015). Despite the role of self-esteem in decision making in older adolescents (World health organization, 2006), there is no consensus (Education, 2016) (Le et al., 2018), with some studies indicating self-esteem is not associated with poor adherence. In contrast, other studies among ALWHIV have found associations with better ART adherence and higher self–esteem (Naar-King et al., 2013). In sub-Saharan Africa, the role of self-esteem has not been described extensively in the literature. Understanding drivers and mediators of self-efficacy among older ALWHIV can provide much-needed data useful in developing interventions that would motivate them towards optimal self-management and optimal outcomes as they transition to adult care. This study aimed at investigating self-efficacy and other associated factors among older ALWHIV transitioning to adult care.

Methods

Study design and site

We conducted a cross-sectional study at the Mbagathi Comprehensive Care Centre (CCC), an HIV care and treatment outpatient clinic in Nairobi, Kenya, to determine the interaction between ART adherence self-efficacy and other psychosocial variables among older ALWHIV. The clinic provided HIV care and treatment to ~300 adolescents aged 10–19 and was purposively selected as it provides HIV care to a large cohort of adolescents in the process of transition to adult care.

The data analyzed and presented in this paper were collected between December 2018 and March 2019 among perinatally infected ALWHIV as part of a more extensive mixed-methods study evaluating psychosocial and clinical outcomes of ALWHIV.

Study population

We enrolled ALWHIV, who presented for routine HIV clinic visits between December 2018 and March 2019. Participants eligible for enrolment were between the ages of 16–19 years, were perinatally HIV infected, and had been using Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) for at least three years. We confirmed perinatal infection using either: 1) clinic records for HIV DNA results within the postnatal and infancy period, or 2) proxies such as duration of >3 years on ART and documented HIV status of the mother. Adolescents who were unaware of their HIV status were not eligible for participation. We received ethical approval from the Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi Ethics and Research Committee.

Measurements

ART Adherence Self-Efficacy

We measured self-efficacy using an unmodified HIV-Adherence self-efficacy assessment survey (HIV-ASES), a previously validated tool (Johnson et al., 2007) consisting of a 12 item Likert scale measuring the level of patient confidence to carry out relevant ART related behaviours. We determined the optimal HIV-ASES cut-off by assessing the performance (specificity and sensitivity) of different cut-off values using. The optimal cut-off was 89.5, and this cut-off had a sensitivity of 74% and specificity of 67%. We computed the area under the ROC curve at a cut-off point of 70% correctly classified 72.8% of all the participants based on whether they had treatment breaks or not. According to this cut-off, 67.5% of the participants had scores >=89.5. A score of < 90 was the cut-off for defining low self-efficacy, with >90 defining high self-efficacy.

Self-esteem

We measured self-esteem using the validated unmodified Rosenberg 10-point scale that measures global self-worth. All items are answered using a 4-point Likert scale format ranging from strongly agree to disagree strongly. (Rosenberg self-esteem scale, 1965) A score <25 indicated low adherence self-esteem, whereas a score >35 showed a higher adherence self-esteem

Adherence

Adherence was measured as self–reported missed doses. An adherence level of >95% has been recommended to achieve optimal viral suppression. (World health organization, 2006) 95% adherence was documented as no more than one dose a month- for those on a once a daily ART regimen and no more than three doses a month for those on twice a day regimens

Perception of social support

We measured social support using a modified question, ‘There is someone with whom I could discuss important decisions or challenges I face related to my HIV status. The validated shortened social provisions scale (Perera, n.d.)(Caron, 2013) measured level type and perceived satisfaction with social support from one’s social network. We selected this specific question as it measured the construct of integration, similar to ART adherence self-efficacy (the primary outcome).

Stigma

We measured experienced stigma using one modified question from the component that measured personalized stigma from the validated 12 points shortened HIV stigma scale (Berger, Ferrans, & Lashley, 2001) (Reinius et al., 2017).’Have you experienced stigma (people treated you differently) after learning of your HIV status? ‘

Data analysis

We computed descriptive statistics of demographic characteristics and the variables of interest. We examined various characteristics (age, gender, disclosure, adherence, treatment break, social support and stigma) with self-efficacy and self-esteem using non-parametric tests, Spearman correlation coefficients for continuous variables and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test and Kruskal Wallis test for categorical variables as appropriate. Next, we developed two multiple linear regression models by incorporating variables with statistical significance (p<0.2) during bivariate analysis. Standardized regression beta coefficients and their significance levels were reported. Lastly, mediation analysis was employed following the following steps (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007). One multivariate linear regression model (model 1) and two multivariate logistic regression models (model 2 and model 3) were used to test the effect of the mediator (self-esteem, M). In the first model, the mediation variable (self-esteem, M) was regressed on the independent variable (self-efficacy, X) with a regression coefficient a. In the second model, the dependent variable (adherence ART, Y) was regressed on the independent variable (self-efficacy, X) with a regression coefficient c. In the third model, the dependent variable (Y) was simultaneously regressed on the independent variable (X) and the mediation variable (M) with regression coefficients c′ (Y on X) and b (Y on M). The paramed package in STATA (Emsley & Liu, 2013) was used to confirm the mediation effect. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 13 Stata Corp Texas. (Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. Stata version 13).

We screened 140 HIV positive adolescents for eligibility according to the study criteria. Out of those screened, 20 participants aged <18 years of age were excluded due to the unavailability of the caregivers to sign the consent, while 28 participants were excluded due to missing information on perinatal infections. A total of 82 HIV positive adolescents were enrolled, Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Study enrolment schema

Baseline characteristics

Participants median age was 17 years [IQR; 16 to 18]. Approximately half (61%) were male. Eighty-one per cent of the adolescents were schooling and enrolled in high school at the time of the study. Most adolescents have been on ART for a median of 11 years [IQR 8,13]. Sixty-one per cent of the adolescents had lost at least one or both parents. Self-reported adherence of >95% was reported by 52 adolescents (64.2%), while 15% reported taking a treatment break in the three months before enrolment to the study. (see Table)

A high proportion of adolescents, 68.3%, showed a high (>89.5) ART adherence self-efficacy (Table 1). Most participants (85.4%) demonstrated high confidence in most areas related to their adherence to ART, particularly on sticking to treatment even when you are not feeling well. Only 42 (51.2%) reported that they would use ART in the presence of people unaware of their HIV status.

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of study participants (N=82)

| Characteristics | Frequency n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median, IQR | 17 (16,18) |

| Age at disclosure | |

| Median, IQR | 12(11,14) |

| Number of years on care | |

| Median, IQR | 12(8,13) |

| Number of years on ART | |

| Median, IQR | 11 (7,13) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 50 (61.0) |

| Female | 32 (39.0) |

| School enrollment | |

| Boarding school | 32 (39.0) |

| College/ university | 6 (7.3) |

| Day school | 35 (42.7) |

| Not enrolled in school | 5 (6.1) |

| Other | 4 (4.9) |

| Parental status | |

| Both parents alive | 29 (35.4) |

| Only father alive | 16 (19.5) |

| Only mother alive | 21 (25.6) |

| Both parents not alive | 13 (15.9) |

| Mother status NK | 3 (3.7) |

| Care giver HIV status | |

| Yes | 65 (79.3) |

| No | 17 (20.7) |

| Viral load (copies /ml) | |

| <400 | 53 (65.4) |

| 400 to 1000 | 2 (2.5) |

| 1000 to 5000 | 6 (7.4) |

| >5000 | 20 (24.7) |

| Treatment break incidence | |

| Yes | 12 (14.8) |

| No | 69 (85.2) |

| Reported ART adherence | |

| >95% adherence | 52 (64.2) |

| <95% adherence | 29 (35.8) |

| Self-efficacy score | |

| Low | 26 (31.7) |

| High | 56 (68.3) |

| Rosenberg Self-esteem score | |

| Low | 2 (2.50) |

| Normal | 37 (45.1) |

| High | 43 (52.4) |

| Social support | |

| Yes | 57 (69.5) |

| No | 25 (30.5) |

| Source of support | |

| Caregiver | 38 (66.7) |

| Sibling | 10 (17.5) |

| Clinic counsellor | 3 (5.3) |

| Other relative | 6 (10.5) |

| Stigma | |

| Yes | 6 (7.3) |

| No | 76 (92.7) |

Using the Rosenberg scale, slightly less than half of the adolescents (45%) had normal self-esteem (<35>25), 52.4% reported having high self-esteem (≥35), and only 2.5% had a low self-esteem score (<25). Almost a third (32.1%) of the participants had an elevated viral load, while 65% and 2.5% had viral suppression (<400 copies/ml) and low-level viremia (400 copies/ml-1000 copies/ml), respectively.

Adherence

ART adherence self-efficacy

Bivariate analysis showed that adherence self-efficacy was significantly associated with self-esteem score, adherence and categorized viral load (p=0.05). The multivariable analysis, self-esteem score, 95% adherence level and viral load group 400 to 1000 copies/ml were significant with adherence self-efficacy. (Table 2).

Table 2:

Association between psychosocial and clinical variables and ART adherence self-efficacy

| HIV ASES SCORE ≥90 | HIV ASES SCORE < 90 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-esteem score (median IQR) | 30 (28–35) | 37 (34–37) | 0.002 |

| Adherence | |||

| ≤95% adherence | 17 (65.4) | 12 (21.8) | <0.001 |

| >95% adherence | 9 (34.6) | 43 (78.2) | |

| Age at disclosure (median IQR) | 12 (11–15) | 12 (10.5– 13.5) | 0.23 |

| No of yrs on ART (median IQR) | 10 (7–13) | 10.5 (6–13) | 0.50 |

| Viral load categories | 0.06 | ||

| <400 | 13 (50.0) | 40 (72.7) | |

| 400–1000 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.6) | |

| 1000–5000 | 4 (15.4) | 2 (3.6) | |

| >5000 | 9 (34.6) | 11 (20.0) | |

| Treatment break | |||

| Yes | 18 (69.2) | 51 (92.7) | 0.005 |

| No | 8 (30.8) | 4 (7.3) | |

| Social support | |||

| Yes | 10 (38.5) | 15 (26.7) | 0.28 |

| No | 16 (61.5) | 41 (73.3) | |

| Stigma | 0.05 | ||

| Yes | 22 (84.6) | 54 (96.4) | |

| No | 4 (15.4) | 2 (3.6) | |

Self-esteem

Multiple regression analysis for adherence self-efficacy and self-esteem score, as shown in Table 2. Controlling for the other covariates, self-esteem, viral load (400 to 1000) and >95% adherence level was found to be significantly associated with adherence self-efficacy (p value=<0.05) adolescents who had a viral load score of less than 400 and 1000 to 5000 were not significant. ART self-efficacy and social support were associated with self-esteem with a significant impact (p=<0.05)

Mediation Analysis

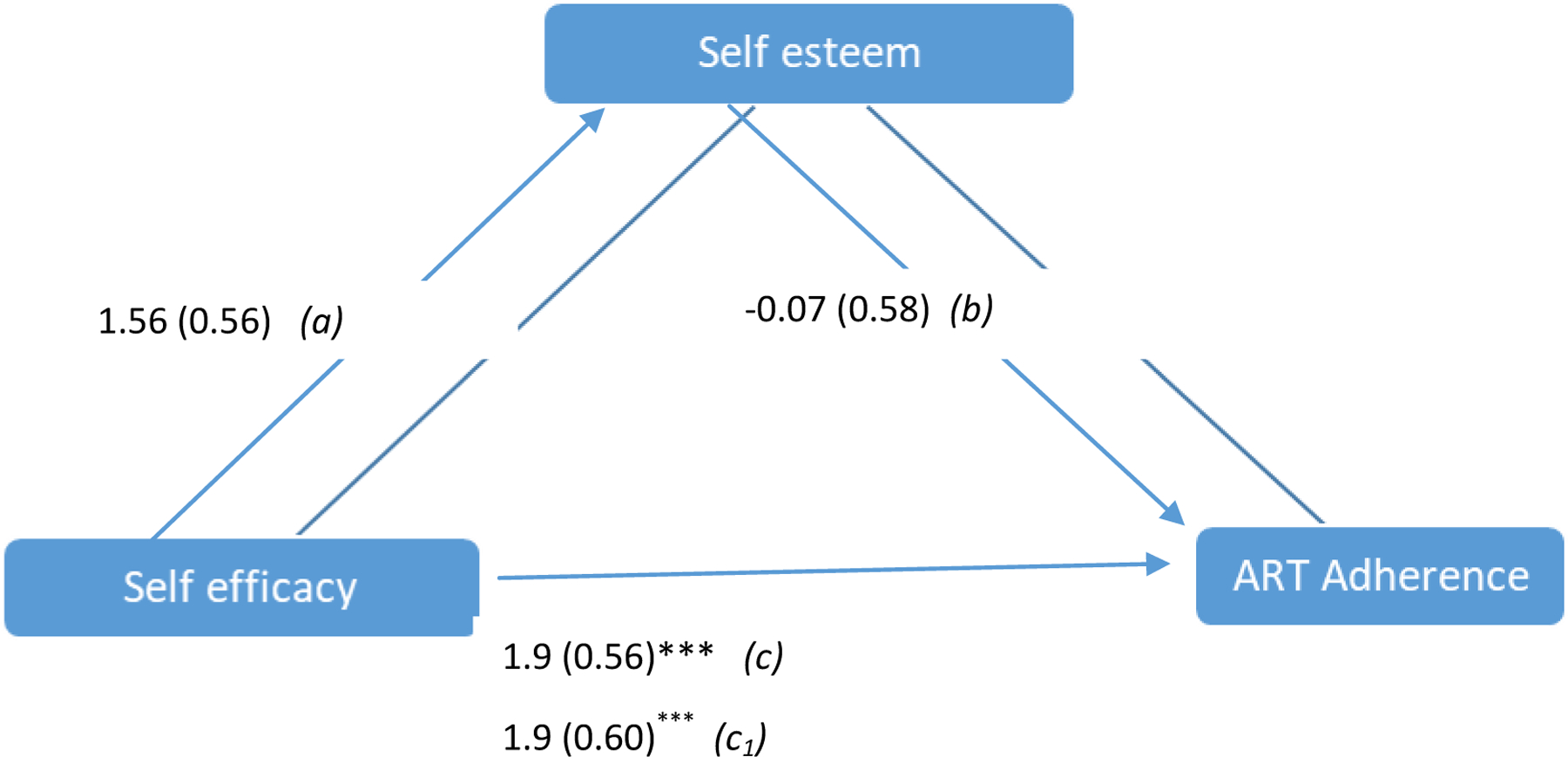

Mediation analysis indicated that self-esteem significantly mediated the effect of self-efficacy on adherence (Table 4 and Figure 2). In Model 1, self-esteem was associated with self-efficacy (regression coefficient=1.56, SE=0.56, p<0.001) after controlling for key demographic and psychosocial factors (treatment break, social support and stigma experience). Model 2 showed that adherence was significantly associated with self-efficacy (regression coefficient=1.93, SE=0.56, p= 0.001). In Model 3, adherence was associated with self-esteem when both adherence self-efficacy and self-esteem were included (regression coefficient=0.07, SE=0.58, p=0.479). In contrast, the significant direct effect of self-efficacy on adherence remained constant (regression coefficient at 1.9 resulting in a complete mediation.). The paramed test indicated that the association between self-efficacy and adherence was mediated by self-esteem with a total effect of OR 6.93 (bootstrap 95%CI 1.99–24.14) with a natural indirect effect (nie) of OR 0.97 (bootstrap 95%CI 0.49–1.59).

Table 4:

A mediation analysis

| Model 1: (X → M) | Model 2: (X → Y) | Model 3: (X, M → Y) | |

|

DV=Self-esteem

(a) |

DV=Adherence

(c) |

DV=Adherence

(c′) (b) |

|

| Treatment break (No) | 0.29 (0.74) | −0.04 (0.73) | 0.04 (0.73) |

| Social support (Yes) | 1.22 (0.54)* | −0.27 (0.56) | −0.25 (0.58) |

| ART self-efficacy score | 1.56 (0.56)* | 1.93 (0.56)*** | 1.93 (0.60)*** |

| Self-esteem | - | - | −0.07 (0.58) |

| Total effect | 6.93 (8.45)*** | - | - |

Note: Numbers in the cells are unstandardized coefficients (SE).

X: self-esteem; M: self-efficacy; Y: Adherence to ART.

p<0.05;

p<0.001

Figure 2: Mediation analysis.

Note: Numbers are unstandardised coefficients and standard errors are given inside the brackets. paramed total effect=6.93 (8.45)*** *p<0.05

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper that describes the relationship between adherence ART self-efficacy and other psychosocial elements and particularly the mediation effect of these factors in affecting adherence among older ALWHIV in sub-Saharan Africa.

This study found that ART self-efficacy was strongly associated with self-esteem and that self-esteem mediated the expected effect of ART self-efficacy in optimal adherence.

Our study found that self-esteem was strongly associated with having social support, which aligns with other studies(Ebru Ikiz, Savi Cakar, & Prof, 2010) that describe a strong relationship between self-esteem during adolescence and perceived social support.

Higher ART adherence self-efficacy was associated with increased self-reported adherence and a higher proportion of adolescents achieving viral load suppression. This finding agrees with studies among adult populations (Johnson et al., 2007). This finding further indicates that higher ART self-efficacy could potentially act as a predictive tool for optimal clinical outcomes during the adolescent transition to adult HIV care. ART self-efficacy was not associated with stigma reported in other studies (Katz et al., 2013)(X. Li et al., 2011) we postulate this may be due to the fact that other reported studies primarily looked at adult populations and seemed to focus on enacted stigma while our study focused on perceived stigma. However, the association between individual characteristics, particularly adherence self-efficacy and adherence, is comparable to similar findings in adult studies(Aregbesola & Adeoye, 2018)(L. Li et al., 2017)(Johnson et al., 2007) and therefore significant because this study focussed on older adolescents in whom HIV disclosure had occurred and who were in the process of transition to adult HIV clinic. The transition process (Cervia, 2013) focuses on equipping adolescents to practice self-management, including self-administration of antiretroviral drugs.

Our study found a strong association between adherence efficacy and self-esteem among adolescents. The relationship of self-esteem and self-efficacy within the realm of self-concept are well described (“Human Nature and the Social Order - Charles Horton Cooley - Google Books,” n.d.)

One study reports no association with self-efficacy (Education, 2016), while another found an association between self-esteem and better adherence(Chen et al., 2013) among ALHIV. We argue that these studies did not primarily focus on adolescents, although one included adolescents in its sample size. Our main finding was the partial mediation of self-esteem on ART adherence self -efficacy resulting in improved adherence. This finding has not been reported in literature among ALWHIV in sub-Saharan Africa. The implications of this finding are mainly the potential effect of including self-esteem building activities within interventions focusing on improving adherence among ALWHIV. It also underscores the role of self-esteem in this population and the resultant effect on health behavior such as ART adherence.

A limitation of this study is that it did not include adolescents with non-perinatal HIV infection acquisition. While developmentally, all ALWHIV face the same challenges, the length of ART use and the life events and stressors provides a unique combination of environmental factors affecting adherence in perinatal HIV acquisition; the scope of this study. The greatest contributor if new infections in Kenya through sexual transmission remain the older adolescents and young adults, and there is still an inherent need to explore this population. Another limitation is that this study focused on urban adolescents, and therefore the results may not be generalizable.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the expected gains of ART adherence self-efficacy may be mediated by low self-esteem. The findings of this study are important in providing insights into the development and implementation of psychosocial interventions. Interventions focusing on adolescents transitioning to adult care should include a component that evaluates individuals’ self-esteem and providing cognitive, psychosocial care or life skills required to ensure that adherence to ART

Table 3:

Bivariate analysis Association between psychosocial and clinical variables and self-esteem

| Normal Self-esteem (n=39) | High self-esteem (n=43) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy score (median IQR) | 94 (70–110) | 110 (100–115) | 0.002 |

| Age at disclosure (median IQR) | 12 (11–14) | 12 (11–14) | 0.86 |

| ART years (median IQR) | 11 (7–12) | 10 (6–13) | 0.79 |

| Viral load categories | |||

| <400 | 23 (58.9)) | 30 (71.4) | 0.64 |

| 400–1000 | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.4) | |

| 1000–5000 | 4 (10.3) | 2 (4.8) | |

| >5000 | 11 (28.2) | 9 (21.4) | |

| Treatment break | |||

| Yes | 30 (78.9) | 39 (90.7) | 0.13 |

| No | 8 (21.1) | 4 (9.3) | |

| Social support | |||

| Yes | 17 (43.6) | 8 (18.6) | 0.01 |

| No | 22 (56.4) | 35 (81.4) | |

| Stigma | |||

| Yes | 35 (89.7) | 41 (95.4) | 0.33 |

| No | 4 (10.3) | 2 (4.6) |

Acknowledgements;

We want to thank the adolescents at Mbagathi hospital who participated in this study. The leadership and staff at Mbagathi hospital, in particular Lilian Abonyo. The study staff included Brenda Anundo and Veronica Mwania for their diligence.

Funding

Support for this project was by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number D43TW009343 and the University of California Global Health Institute (UCGHI). The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or UCGHI. The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest statement

All authors declare no conflicting interest.

References

- Adefolalu A, Nkosi Z, Olorunju S, & Masemola P (2014). Self-efficacy, medication beliefs and adherence to antiretroviral therapy by patients attending a health facility in Pretoria. South African Family Practice, 56(5), 281–285. [Google Scholar]

- Aregbesola OH, & Adeoye IA (2018). Self-efficacy and antiretroviral therapy adherence among HIV positive pregnant women in South-West Nigeria: a mixed-methods study. Tanzania Journal of Health Research, 20(4). [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, & Lashley FR (2001). Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing and Health, 24(6), 518–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berihun Assefa Dachew1*, T. B. T. A. M. B. (2014). Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy and associated factors among children at theUniversity of Gondar Hospital and Gondar PolyClinic, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional institutional based study. BMC Public Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Caron J (2013). [A validation of the Social Provisions Scale: the SPS-10 items]. Sante Mentale Au Quebec, 38(1), 297–318. Retrieved from [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervia JS (2013). Easing the transition of HIV-infected adolescents to adult care. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 27(12), 692–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W-T, Wantland D, Reid P, Corless IB, Eller LS, Iipinge S, … Webel AR (2013). Engagement with Health Care Providers Affects Self-Efficacy, Self-Esteem, Medication Adherence and Quality of Life in People Living with HIV. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 4(11), 256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebru Ikiz F, Savi Cakar F, & Prof A (2010). Perceived social support and self-esteem in adolescence. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 2338–2342. [Google Scholar]

- Education JP (2016). IMPLICATIONS OF SELF-ESTEEM. XIV(1), 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Emsley R, & Liu H (2013). PARAMED: Stata module to perform causal mediation analysis using parametric regression models. Statistical Software Components.

- Farmer RF, Jarvis LRL, Berent MK, & Corbett A (2001). Contributions to global self-esteem: The role of importance attached to self-concepts associated with the five-factor model. Journal of Research in Personality, 35(4), 483–499. [Google Scholar]

- Firdu N, Enquselassie F, & Jerene D (2017). HIV-infected adolescents have low adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A cross-sectional study in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Pan African Medical Journal, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getachew Arage1, G. A. T. H. K. (2014). Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and its associated factors among children at South Wollo Zone Hospitals, Northeast Ethiopia_ a cross-sectional study _ Kopernio. BMC Public Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Human Nature and the Social Order - Charles Horton Cooley - Google Books. (n.d.). Retrieved June 4, 2020, from

- Johnson MO, Neilands TB, Dilworth SE, Morin SF, Remien RH, & Chesney MA (2007). The role of self-efficacy in HIV treatment adherence: validation of the HIV Treatment Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale (HIV-ASES). Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 30(5), 359–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasedde S, Kapogiannis BG, McClure C, & Luo C (2014). Executive summary: Opportunities for action and impact to address HIV and AIDS in adolescents. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 66(SUPPL. 2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, Psaros C, Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, & Tsai AC (2013). Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. Journal of the International AIDS Society, Vol. 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le M, Arenas-pinto A, Melvin D, Parrott F, Foster C, & Ford D (2018). Anxiety and depression symptoms in young people with perinatally acquired HIV and HIV affected young people in England. AIDS Care, 30(8), 1040–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, & Hazra R (2015, December 2). Achieving 90–90-90 in paediatric HIV: Adolescence as the touchstone for transition success. Journal of the International AIDS Society, Vol. 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Lin C, Lee SJ, Tuan LA, Feng N, & Tuan NA (2017). Antiretroviral therapy adherence and self-efficacy among people living with HIV and a history of drug use in Vietnam. International Journal of STD and AIDS, 28(12), 1247–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Huang L, Wang H, Fennie KP, He G, & Williams AB (2011). Stigma mediates the relationship between self-efficacy, medication adherence, and quality of life among people living with HIV/AIDS in China. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 25(11), 665–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, & Fritz MS (2007). Mediation Analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 593–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller J, Alie C, Jonas B, Brown E, & Sherr L (2011). A quasi-experimental evaluation of a community-based art therapy intervention exploring the psychosocial health of children affected by HIV in South Africa. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 16(1), 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Outlaw AY, Sarr M, Parsons JT, Belzer M, Macdonell K, … Adolescent Medicine Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2013). Motivational Enhancement System for Adherence (MESA): a randomized pilot trial of a brief computer-delivered prevention intervention for youth initiating antiretroviral treatment. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(6), 638–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabukeera-barungi N, Elyanu P, Asire B, Katureebe C, Lukabwe I, Namusoke E, … Tumwesigye N (2015). Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and retention in care for adolescents living with HIV from 10 districts in Uganda. BMC Infectious Diseases, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nyandiko WM, Ayaya S, Nabakwe E, Tenge C, Sidle JE, Yiannoutsos CT, … Tierney WM (2006). Outcomes of HIV-infected orphaned and non-orphaned children on antiretroviral therapy in Western Kenya. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 43(4), 418–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera HN (n.d.). RUNNING HEAD: THE SOCIAL PROVISIONS SCALE AND BI-FACTOR-ESEM Construct Validity of the Social Provisions Scale: A Bifactor Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling Approach. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Petersen I, Bhana A, Myeza N, Alicea S, John S, Holst H, … Mellins C (2010). Psychosocial challenges and protective influences for socio-emotional coping of HIV+ adolescents in South Africa: A qualitative investigation. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 22(8), 970–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinius M, Wettergren L, Wiklander M, Svedhem V, Ekström AM, & Eriksson LE (2017). Development of a 12-item short version of the HIV stigma scale. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSENBERG SELF-ESTEEM SCALE. (1965).

- Sharma S, & Agarwala S (2015). Self-Esteem and Collective Self-Esteem Among Adolescents: An Interventional Approach. Psychological Thought, 8(1), 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- World health organization. (2006). From Access to Adherence: The Challenges of Antiretroviral Treatment - Studies from Botswana, Tanzania and Uganda, 2006: Factors that facilitate or constrain adherence to antiretroviral therapy among adults in Uganda: a pre-intervention study: Chapter 3: Retrieved March 26, 2020, from