Abstract

The development of bioorthogonal fluorogenic probes constitutes a vital force to advance life sciences. Tetrazine-encoded green fluorescent proteins (GFPs) show high bioorthogonal reaction rate and genetic encodability, but suffer from low fluorogenicity. Here, we unveil the real-time fluorescence mechanisms by investigating two site-specific tetrazine-modified superfolder GFPs via ultrafast spectroscopy and theoretical calculations. Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) is quantitatively modeled and revealed to govern the fluorescence quenching; for GFP150-Tet with a fluorescence turn-on ratio of ~9, it contains trimodal subpopulations with good (P1), random (P2), and poor (P3) alignments between the transition dipole moments of protein chromophore (donor) and tetrazine tag (Tet-v2.0, acceptor). By rationally designing a more free/tight environment, we created new mutants Y200A/S202Y to introduce more P2/P1 populations and improve the turn-on ratios to ~14/31, making the fluorogenicity of GFP150-Tet-S202Y the highest among all up-to-date tetrazine-encoded GFPs. In live eukaryotic cells, the GFP150-Tet-v3.0-S202Y mutant demonstrates notably increased fluorogenicity, substantiating our generalizable design strategy.

Keywords: turn-on fluorescence, bioorthogonal toolkit, genetic code expansion, ultrafast energy transfer, rational protein design, femtosecond laser spectroscopy

Graphical Abstract

Targeted mutagenesis aided by ultrafast molecular spectroscopic insights into the tetrazine-encoded green fluorescent proteins in action in physiologically relevant environments has effectively achieved the record-high bioorthogonal fluorogenicity to date for next-generation bioimaging and life science advances. The rational protein design strategy incorporating noncanonical amino acids with a gain of function and demonstrated live eukaryotic cell applications is generalizable to any fluorescence-based detectors and sensors.

1. Introduction

Fluorogenic bioorthogonal probes represent one of the most powerful tools for bioimaging developed in recent years (1–4). These bioprobes achieve high signal-to-noise ratio with low fluorescence background (5) and can selectively label targeted proteins without affecting natural biochemical processes (6). Among them, s-tetrazine (1,2,4,5-tetrazine) (7) and its derivatives have attracted increasing attention due to their dual function as a fluorescence quencher and a bioorthogonal reactive group (8). An inherent “dark” nπ* transition between the ground (S0) and first singlet excited state (S1) of s-tetrazine allows it to quench emission of nearby fluorophores (9). Moreover, s-tetrazine undergoes inverse-electron-demand Diels-Alder reactions (iEDDA) with olefins such as trans-cyclooctene (TCO) (10). Due to its fast kinetics, high selectivity, high yield, reactant and product stability, and biocompatibility, iEDDA has found wide applications across chemical biology and life sciences (11, 12).

To date, the development of tetrazine-based fluorogens has been focused on small organic molecules (13). A common strategy is to covalently bond s-tetrazine with a chromophore whose fluorescence can be quenched via Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET, through-space) (14) and electron exchange (Dexter mechanism) (15) or through-bond energy transfer (TBET) (16). Recent innovations include the monochromophoric design (17) and formation of new fluorophores after iEDDA reaction (18). Notably, s-tetrazine can also be incorporated into carbon nanotubes and polypept(o)ides, expanding their applications (19, 20). These advances greatly improve the properties of such tetrazine-fluorophore conjugates with longer emission wavelengths and larger fluorescence turn-on ratios (17, 21–23).

However, exogenous organic fluorophores are intrinsically more invasive than endogenous reporters such as the heterologously expressed green fluorescence protein (GFP), whose discovery and development have revolutionized bioimaging and biomedicine (24, 25). The genetic code expansion (GCE) technique (26) has further allowed site-specific incorporation of noncanonical amino acid (ncAA) derivatives with tetrazine into FPs and other proteins (27–31). We previously encoded a superfolder (sf)GFP (32) with a tetrazine-containing amino acid referred to as Tet-v2.0 and showed that this genetically encoded handle can effectively react with a cyclopropane-fused sTCO (a strained TCO) (27). Interestingly, we observed that in addition to enabling ultrafast labeling, incorporation of Tet-v2.0-Me at TAG150 (ASN149Tet-v2.0 mutation, Me indicates methyl group on Tet ring) significantly quenches the fluorescence, the restoration of which can be achieved through reaction with sTCO. In fact, we exploited this unique property to accurately reveal the in cellulo biomolecular rate constant between genetically encoded Tet-v2.0 and sTCO to be ~7.2×104 M−1·s−1 – the first measurement of its kind (29). We envisioned the fluorescence quenching property to be of critical value to a number of other approaches, ranging from biosensing to imaging in life sciences; however, the relatively low fluorescence turn-on ratio (9-fold, see the measured fluorescence quantum yield/FQY in Table 1) (30) when compared to typical tetrazine dyes limits its utility (33). Therefore, we posit that improving the fluorogenicity of tetrazine-encoded GFP is of great significance to develop this bioorthogonal toolset with versatile combinations of tetrazine amino acids and sTCO reagents – also establishing a solid molecular foundation for rational design of proteins – for future use in eukaryotic cells to mitigate background fluorescence and enhance turn-on probing.

Table 1.

Fluorescence quantum yield (FQY) of sfGFP and its Tet-v2.0 mutants1

| Protein | FQY | FQY after reaction with sTCO | Turn-on ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| sfGFP | 0.65 | N/A | N/A |

| GFP134-Tet | 0.53 ± 0.02 | 0.62 ± 0.02 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| GFP150-Tet | 0.070 ± 0.002 | 0.64 ± 0.02 | 9.1 ± 0.4 |

Error bars for the GFP-Tet proteins were calculated as two times the standard error at the 95% confidence level. Note that no error bars were reported for the FQY of sfGFP (32). Error propagation has been performed to obtain the error bars for the turn-on ratios.

In this work, we develop a series of Tet-v2.0-Me-modified sfGFP with various optical properties, including two site-specific mutants (GFP150-Tet and GFP134-Tet) with different fluorescence turn-on ratios (Table 1), aiming to delineate the underlying fluorescence quenching mechanism with ultrafast spectroscopy, quantum calculations, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. We found that FRET is responsible for fluorescence quenching with incorporation of Tet-v2.0 at a specific site, which introduces several distinct populations with different transition dipole moment (TDM) alignments between the tetrazine moiety and protein chromophore, thus governing the FRET rate and overall fluorescence properties. With these fundamental insights, we rationally designed four new GFP150-Tet-based mutants and discovered that Y200A and S202Y mutations can markedly improve fluorescence turn-on ratios to ~14 and 31 folds. We also demonstrated the application of our engineered sfGFP for monitoring labelling reactions in live HEK293T cells. This development makes the fluorogenicity of GFP150-Tet-S202Y, to our knowledge, the highest among up-to-date tetrazine-tagged GFPs as a powerful bioorthogonal toolset for myriad downstream applications. The quantitative mapping of FRET in action via ultrafast spectroscopy also provides generalizable strategies for biophysics and photochemistry.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Steady-State Electronic Characterization of sfGFP and its Mutants

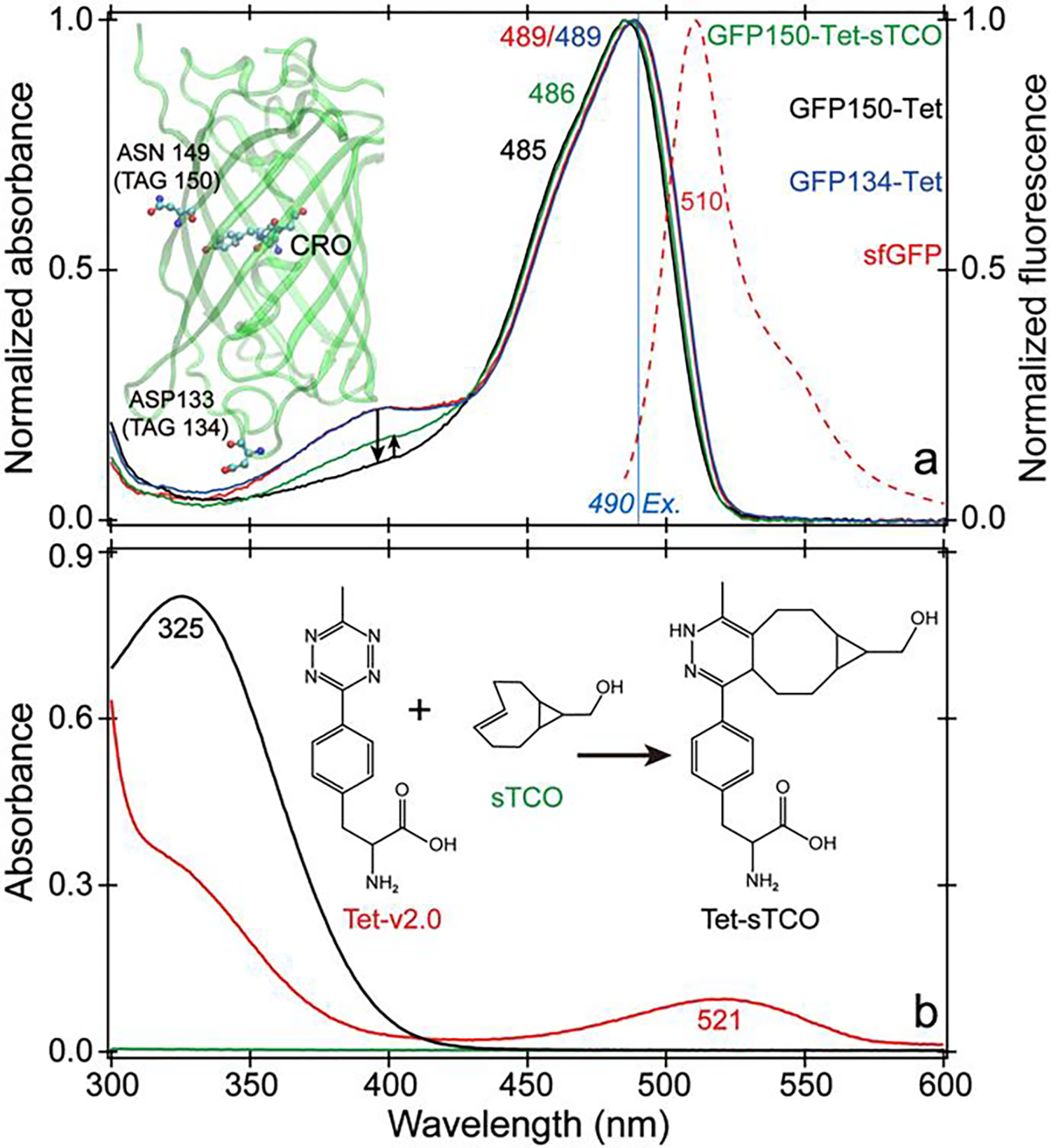

The ground state absorption spectra of all sfGFP mutants display the classic absorption profile of GFP with ~400 and 490 nm peaks attributed to the protonated and deprotonated chromophores, respectively (Figure 1a) (24, 34, 35). Incorporation of Tet-v2.0 at site 150 reduces the chromophore pKa (suppression of protonated state at same buffer pH) and blue-shifts the deprotonated state absorption peak by 4 nm. Reaction with sTCO partially mitigates these effects. However, the absorption profile of GFP134-Tet almost matches sfGFP. All the emission spectra are largely identical with a 510 nm peak regardless of mutation or reaction (Figure S1, Supporting Information). Upon inspection of the sfGFP crystal structure (32), the chromophore (CRO) at the β-barrel center sees TAG150 (Asn149) and 134 (Asp133) on dramatically different sites on β-barrel surface (Figure 1a inset), indicative of some distance-related effects caused by Tet-v2.0 (see below). A detailed look at the CRO local environment shows that Asn149 cannot directly hydrogen (H)-bond with the CRO compared to a closer water molecule, Thr203, and His148 (Figure S2).

Figure 1. Steady-state electronic characterization of sfGFP mutants and the tetrazine moiety.

(a) Absorption (solid) spectra of sfGFP (red), GFP134-Tet (blue), GFP150-Tet (black), and GFP150-Tet-sTCO (green) with emission (red dashed) spectrum of sfGFP. Black arrows show notable variation of the blue-absorbing band due to the protonated chromophore (CRO). (b) Absorption spectra of Tet-v2.0 (short for Tet-v2.0-Me, red), sTCO (green), and their product Tet-sTCO (black) in aqueous buffer.

Since Tet-v2.0 is much bulkier and less polar than Asn, the chromophore pKa is likely affected by long-range steric and/or electrostatic interactions. Steric effects are excluded because GFP150-Tet-sTCO with an even larger sidechain exerts less effect (Figure 1a). Our quantum calculations of the sidechain dipole moments of Asn, Tet-v2.0, and Tet-sTCO in ground state (S0) exhibit an interesting trend: ~5.36, 0.83, and 1.54 D (Figure S3). Incorporation of the least polar Tet-v2.0 at TAG150 reduces the original electrostatic interaction between Asn149 and CRO, while Tet-sTCO with an intermediate polarity alleviates this effect. Therefore, the electrostatic interaction change can lead to the observed spectral variation (Figure 1a): a smaller dipole moment at site 150 results in a smaller pKa and more stabilization of the deprotonated CRO ground state (36).

Notably, Tet-v2.0 exhibits a visible absorption band from ~450–570 nm (Figure 1b) that overlaps with the emission band of sfGFP. Reaction with sTCO eliminates this absorption band and restores the protein fluorescence. Since the degree of quenching is distance-dependent (see GFP134-Tet versus GFP150-Tet in Table 1, Figure 1a), the mechanism is likely FRET, which supports the energy transfer from photoexcited sfGFP chromophore to the tagged Tet-v2.0. Similar to s-tetrazine, the S0–S1 electronic transition of Tet-v2.0 is concentrated on the tetrazine ring with nπ* character, supported by density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent (TD)-DFT calculations (37) (Figure S3). Meanwhile, Tet-v2.0 emits dim fluorescence around 590 nm with an FQY of 1.2×10−3 upon 520 nm excitation (Figure S4). Reaction with sTCO disrupts the tetrazine conjugation, changes the S0–S1 electronic transition to ππ*, increases the oscillator strength, and blue-shifts the reddest absorption peak to UV region (Figure 1b and Figure S3) outside the GFP chromophore emission range.

2.2. Fluorescence Quenching with Conformational Heterogeneity inside GFP134/150-Tet

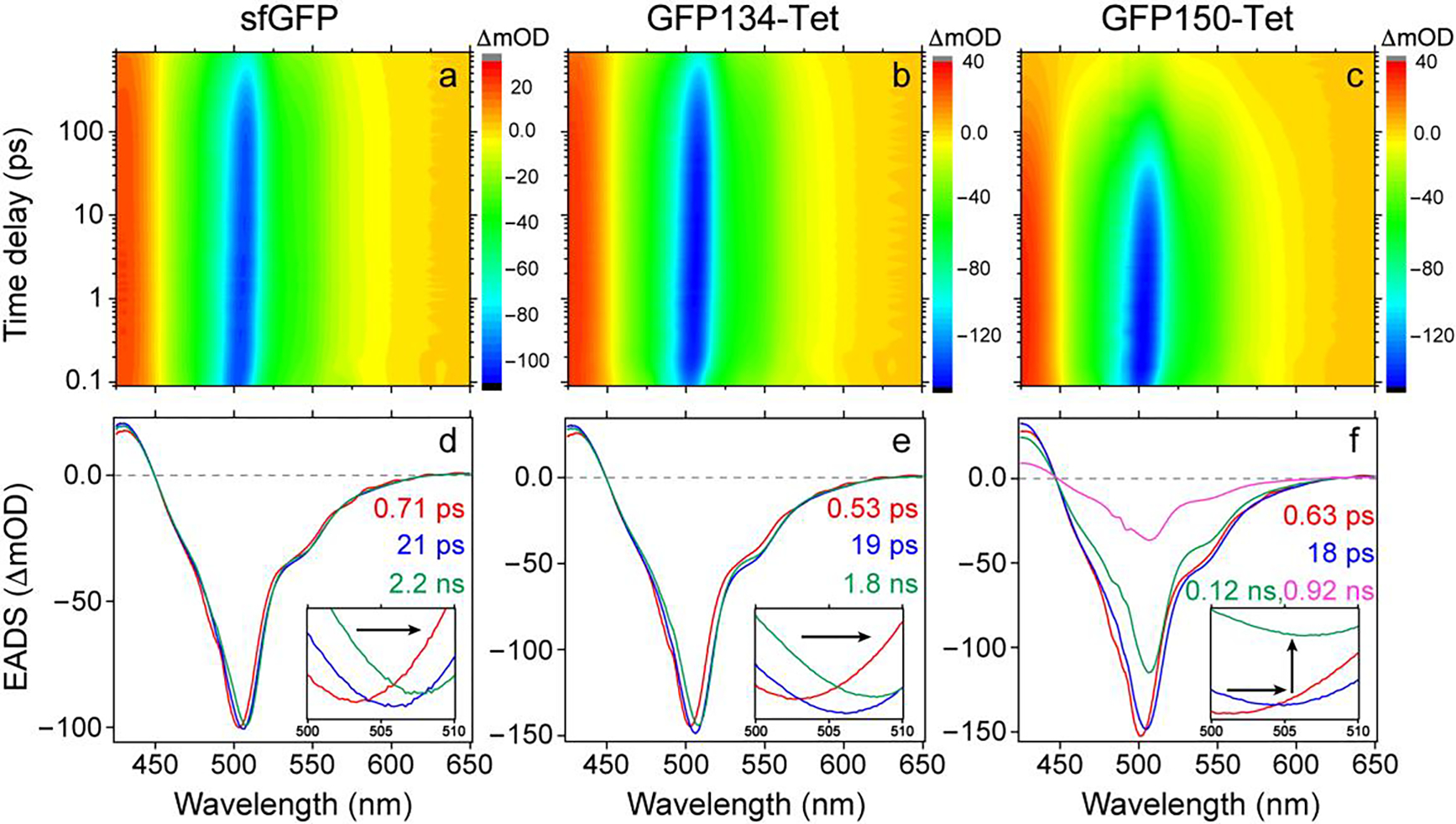

Insights into FRET “in action” can be gained by tracking the excited-state dynamics of sfGFP samples. Femtosecond transient absorption (fs-TA) with 490 nm excitation was performed to focus on the deprotonated chromophores, exhibiting almost identical electronic features with a dominant stimulated emission (SE) band centered at 510 nm and an excited-state absorption (ESA) band below ~450 nm. Notably, the SE band of GFP150-Tet decays much faster than all the other sfGFP samples (Figure 2 and Figure S5). Moreover, multiexponential fitting of the fs-TA signal intensity within a certain spectral region has the intrinsic limit to capture the broad TA band’s peak wavelength shift, especially when the shift is small while the peak intensity remains largely constant within that probe window (38). Therefore, as an example, the intermediate ~20 ps components all have a very low weight (see Figure S5e and f, except for GFP150-Tet that has an FRET-induced faster relaxation rate and a much higher amplitude weight) and cannot be clearly observed or accurately determined from the probe-dependent fits of the TA spectra (36, 38).

Figure 2. Transient electronic dynamics elucidate the excited-state relaxation of proteins after 490 nm excitation.

(a–c) 2D-semilogarithmic contour plots of fs-TA spectra and (d–f) global analysis with evolution-associated difference spectra (EADS) of sfGFP, GFP134-Tet, and GFP150-Tet, respectively. The retrieved red→blue→green/magenta traces are shown with the corresponding lifetimes color-coded and listed in the insets.

Global analysis with the evolution-associated difference spectra (EADS) reveals three decay components for sfGFP and GFP134-Tet but four components for GFP150-Tet, corroborated by the aforementioned multiexponential fitting of SE band intensities (Figure S5e and f). All the spectra exhibit a peak redshift with a sub-picosecond (sub-ps) and ~20 ps time constants, attributable to local water solvation and relaxation of polar residue sidechains around the chromophore, respectively (39, 40). The initial solvation process also leads to a slight enhancement of S1→S0 oscillator strength, reflected by the SE band increase (red→blue traces in Figure 2d and e), consistent with the fluorescence intensity rise time constant of ~1.9 ps as observed in GFP using fluorescence upconversion spectroscopy (41). Notably, the SE peak shows a noticeable redshift but its intensity hardly decreases during the second process for sfGFP and GFP134-Tet (Figure 2 and Figure S5), indicating that most of their populations remain in S1 on the tens-of-ps timescale.

Regarding the distinct longer time constants, we note that global analysis (Figure 2d,e,f) or least-squares fitting to the probe-dependent TA data (Figures S5e,f and S10e,f) can retrieve the characteristic time constants that go beyond the value set by the delay stage length, owing to the nature of exponential decay functions. In particular, the 2.2±0.1 nanoseconds (ns) component for sfGFP (Figure 2d) is the apparent fluorescence lifetime τFL, which can be calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where kr, knr and τr, τnr are the reaction rate constants and lifetimes of the radiative, nonradiative pathways, respectively. Note that there could be multiple nonradiative rate constants, which can be summed up to one knr value. Regarding the emission property,

| (2) |

where ϕFL is FQY (0.65 for sfGFP, see Table 1) (32). Therefore, τr and τnr were calculated to be ~3.4 and 6.3 ns, respectively, capturing the essence of these distinct decay processes.

The slight decrease of the third component (1.8±0.1 ns) in GFP134-Tet can be rationalized by FRET contribution. After reacting with sTCO, the SE lifetimes of both GFP134-Tet-sTCO and GFP150-Tet-sTCO increase to ~2.1 ns (Figure S5), implying a deactivation of the ultrafast FRET pathway. The FRET lifetime (τFRET) can be calculated as follows (42):

| (3) |

where is the donor fluorescence lifetime in the absence of an acceptor, which is 2.2 ns for sfGFP. R0, termed as the Förster radius, is the distance at which FRET efficiency is 50%. R is the distance between the donor and acceptor. R0 can be calculated by

| (4) |

where κ2 is the interdipole orientation factor, which equals to 2/3 assuming random orientations (43). The pre-factor 0.02108 has units of (M·cm·nm2)1/6, ϕD is the donor FQY in the absence of an acceptor (0.65 for sfGFP), n is the index of refraction of medium, and J(λ) represents spectral overlap between the donor emission and acceptor absorption, which is ~2.4×1013 M−1·cm−1·nm4 (see Experimental Methods). No uncertainties were recorded for the parameters in equation (4), and we thus find that R0 can be determined as 2.6 nm.

However, the lack of crystal structures for these tetrazine-encoded sfGFP mutants inhibits direct measurements of R. To overcome this problem, we performed 50-ns MD simulations of both GFP134-Tet and GFP150-Tet (see Experimental Methods). The resultant centroid structures of both proteins (Figure 3) show that Tet-v2.0 tags are located on the surface and pointing away from the β-barrel, ready to react with sTCO at high speed (29). The TDM of the chromophore, modeled as 4’-hydroxybenzylidene-2,3-dimethylimidazolinone (p-HBDI) (44), and Tet-v2.0 were calculated (Figure 4a). R was measured as distance between the HBDI bridge carbon and s-tetrazine ring carbon (C07, see SI Computational Appendix) connected with the benzene ring through MD simulation trajectories, and the probability density (see Experimental Methods) of these distance values were plotted for GFP134-Tet and GFP150-Tet (Figure 4b,c). These estimated distances allow us to use representative interdipole orientations to calculate the FRET rates for comparison to experimental results. Notably, we measured the aforementioned chromophore-tag distances using the centroid (average) structures shown in Figure 3 to be ~1.57 and 3.20 nm for GFP150-Tet and GFP134-Tet, respectively. This finding substantiates the validity of using the most probable distance from the largely symmetric distance distribution profiles (Figure 4b,c with peak distances denoted) for the ensuing calculations of characteristic FRET rates and efficiencies.

Figure 3. Conformational space of the protein chromophore (CRO) and tetrazine tag.

Centroid structures (a and b) with local environments of Tet-v2.0 amino acids (c and d) from molecular dynamics simulations of GFP134-Tet and GFP150-Tet, respectively. The CRO is shown in ball-and-stick model inside each protein pocket, and the Tet-v2.0 site positions are noted. Color schemes for the atomic spheres: carbon, cyan; nitrogen, blue; oxygen, red; hydrogen, white.

Figure 4. FRET distance estimates from molecular dynamics simulations.

(a) Transition dipole moments (black arrows) of p-HBDI (GFP model chromophore) and Tet-v2.0 with (b and c) representative distances between them in GFP134-Tet (green) and GFP150-Tet (olive). The plots do not start at zero distance to highlight the notably different distance profiles. The full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) of the distance distribution profile is denoted by the double-sided arrow in each panel with the FWHM values listed.

The most probable R value between TDMs of the chromophore and Tet-v2.0 at site 134 is 3.25 nm, so τFRET of GFP134-Tet was calculated to be 8.4±0.4 ns using equation (3). Moreover, the apparent fluorescence lifetime with an acceptor can be calculated by

| (5) |

Since the Asp133Tet-v2.0 mutation site is far away from the chromophore (Figures 1a and 3a), it is reasonable to assume that τr and τnr are unchanged from sfGFP as intrinsic parameters. Therefore, was calculated to be ~1.7 ns, well matching the measured 1.8 ns lifetime (Figure 2e). If we used 3.20 nm distance, we would get the same value of 1.7 ns.

Notably, the theoretical FRET efficiency can be calculated by three equations below (14, 45):

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

where and represent the apparent fluorescence lifetime, FQY of the donor with and without the acceptor, respectively. The EFRET for GFP134-Tet was calculated to be ~21, 18, and 18% based on equations (6), (7), and (8), respectively, also using data from Figure 4b, Figure 2d,e, and Table 1. Error propagation has been performed for the lifetime- and FQY-based EFRET values using equations (7) and (8) to have a typical error bar of ±3% (one standard deviation), while the distance-based values using equation (6) are accurate due to the calculation/simulation-derived values (see equation (4) and Figure 4b) with no uncertainties. Since we assumed a random orientation between both TDMs of the CRO and Tet-v2.0 and set the interdipole orientation factor (κ2) at 2/3 when calculating R0, the excellent match between these EFRET values suggests that Tet-v2.0 is indeed in a free environment and can adopt random orientations. This finding is corroborated by MD simulation results of GFP134-Tet (Figure 3c), showing three aliphatic residues (Glu132, Leu137, and Lys140) in close proximity to the α-carbon of Tet-v2.0 at site 134, leaving it free to rotate, also in accord with the larger full-width-at-half-maximum for the interdipole distances in GFP134-Tet (Figure 4b) than GFP150-Tet (Figure 4c).

In contrast, GFP150-Tet exhibits three distinct time constants of 18±2 ps, 0.12±0.01 ns, and 0.92±0.02 ns beyond the aforementioned solvation process (Figure 2f). It is tempting to assign the 18 ps component to protein sidechain relaxation around the chromophore (~20 ps in Figure 2d,e) due to similar time constants; however, the SE band of GFP150-Tet displays almost no peak redshift and decays notably on this timescale, which indicates a marked population loss and refutes this assignment. Upon direct calculation of FRET efficiencies based on these three lifetimes and equation (7), neither of them (99%, 95%, and 58%) would match the 89% value obtained from FQYs using equation (8) and data in Table 1. Error propagation using uncertainties in retrieved time constants (Figure 2) or measured FQYs (Table 1) results in a standard deviation at or below 2% for these calculated FRET efficiencies. Therefore, we propose that this protein mutant has three distinct populations in S0 and all of them contribute to FRET. Given the most probable distance R at 1.57 nm (Figure 4c), the FRET lifetime of GFP150-Tet was calculated to be ~0.11 ns assuming random TDM orientations and using equation (3). The fluorescence lifetimes can also be calculated using equation (5), and since site-150 mutation on the β-barrel surface is relatively distant from the chromophore (Figure 3b and Figure S2), τr and τnr should not be affected much in GFP150-Tet versus sfGFP. As a result, the calculated is ~0.10 ns, closely matching the observed ~0.12 ns component; we termed this population as P2.

For the population (P1) that exhibits the shortest time constant (~18 ps), its FRET lifetime can be back-derived from equation (5) to be ~19 ps, which may arise from a short R or good alignment of TDMs. When we used the same R0 of 2.6 nm, R was calculated by equation (3) to be 1.2 nm, well below the ~1.37 nm limit from the distance distributions (Figure 4c). Therefore, we used the most probable distance of 1.57 nm and calculated the associated κ2 to be ~4 (R0≈3.5 nm), reaching the theoretical maximum of 4 for parallel TDMs between the FRET donor and acceptor (42). These quantitative spectroscopic findings substantiate the importance of building an appropriate model for delineating major FRET pathways, and the aforementioned statistical analysis and error propagation for key parameters such as TA time constants, FQYs, and FRET efficiencies manifest the high accuracy of our analysis.

For the population (P3) that is responsible for the largest time constant of ~0.92 ns (), its FRET lifetime was calculated to be ~1.6 ns that may rise from a long R or poor alignment of TDMs. Similarly, using the same R0 value of 2.6 nm, the R that corresponds to this time constant would be ~2.5 nm, well beyond the distance range from MD simulations (Figure 4c). This long FRET lifetime should thus be owing to TDM poor alignment issues, and with the most probable R of 1.57 nm (Figure 4c, conserved for all the subpopulations of interest), κ2 was calculated to be ~0.047 (R0≈1.7 nm), slightly above the theoretical minimum of zero (mutually perpendicular TDMs) (42). Comparing to the largely homogenous GFP134-Tet, the significant inhomogeneity for GFP150-Tet stems from its compact local environment, wherein the Tet-v2.0 tag is surrounded by three aromatic residues (His148, Tyr200, and Tyr151) as well as Ser202 (Figure 3d). This crowded environment likely traps Tet-v2.0 in several specific geometries without a swift interconversion (36), leading to the conspicuous heterogeneity in GFP150-Tet (see Figure 2f).

Furthermore, the relative P1, P2, and P3 percentages of GFP150-Tet can be retrieved from their decay magnitudes of the associated lifetimes (Figure 2f), yielding ~24, 51, and 25%. Combining with their individual FRET efficiency of 99, 95, and 58% as calculated above, the overall FRET efficiency for GFP150-Tet reaches 87%, closely matching the 89% FRET efficiency calculated from FQYs and firmly supporting our quantitative analysis. Notably, the inhomogeneity of GFP150-Tet mainly arises from Tet-v2.0, not from the chromophore itself inside β-barrel because the TAG150 or TAG134 hardly affects local environment of the “distant” chromophore (Figure S2). Consequently, these subpopulations cannot be distinguished from steady-state electronic spectroscopy of proteins that mainly depends on the chromophores, but they can be readily revealed by tracking the time-resolved excited state pathways after photoexcitation, thus substantiating the necessity of performing ultrafast molecular spectroscopy. The observed distinct FRET lifetimes mainly arise from heterogeneous orientations of TDMs, not the distance, between the embedded chromophore and exposed Tet-v2.0 tag. Although we cannot retrieve exact TDM distributions from MD simulations, we plotted the dihedral angles between the bridge carbons of the chromophore and Tet-v2.0 (Figure S6). In contrast to the distance distributions (Figure 4) wherein the density profile of GFP150-Tet is narrower than GFP134-Tet, the dihedral angle distribution of GFP150-Tet is broader and also shows a long tail. Since the chromophores in both proteins are embedded in a rather rigid environment, a broader and more heterogeneous distribution of the C1-C2-C3-C4 dihedral angle (see atomic numbering in Figure S6) indicates that the Tet-v2.0 tag notably samples more conformational space in GFP150-Tet than GFP134-Tet, which can lead to different interdipole moment alignments and FRET constants as unveiled by ultrafast electronic spectroscopy (Figure 2).

These correlated experimental and simulation results suggest that in these proteins, κ2 often greatly affects the FRET efficiency. In fact, κ2 is intrinsically challenging to be accurately determined for fluorescent proteins even with crystal structures, which typically capture one dominant geometry of the proteins in solution with common mismatches between the measured FRET efficiency and calculated values using the crystal parameters (46, 47). Our calculations of FRET time constants and efficiencies for various GFP-Tet proteins confirm the robustness of this approach using the most likely distance with characteristic orientation factors to correlate with the ensemble average values from molecular spectroscopy (both steady-state and time-resolved), notably without incurring substantial uncertainty due to the nature of such representative calculations (i.e., capturing major factors with highly accurate mean values). In essence, our ultrafast-spectroscopy-enabled dynamic tracking of FRET inside tetrazine-encoded GFPs in solution uncovered the hidden ground-state species, supporting the targeted design for versatile and powerful bioorthogonal toolsets (see below).

2.3. Relaxation Lifetime of Tet-v2.0 Amino Acid

Following FRET, Tet-v2.0 continues to release energy nonradiatively. Fs-TA with the same 490 nm excitation was performed on Tet-v2.0, but it yields essentially no signal (Figure S7). This control experiment confirms that fs-TA spectra in Figure 2 and Figure S5 purely track the electronic response of sfGFP chromophore, especially given that the Tet-v2.0 monomer concentration used in fs-TA experiment (~4 mM, see Experimental Methods) is over 100 times larger than that in sfGFP mutants (0.035 mM). Several reports indicated the possibility of decomposing tetrazine with ultrafast laser (48), but this scenario often occurs with UV excitation, whereas our UV/Visible spectrum of Tet-v2.0 displayed almost no change before and after fs-TA experiments with 490 nm excitation (Figure S8) in our optical setup with all the irradiation power on the tetrazine molecules in solution (see Experimental Methods).

The radiative lifetime of Tet-v2.0 can be estimated from the Strickler-Berg equation (49):

| (9) |

where EA and EF are the measured steady-state absorption and fluorescence peak energies in eV unit (Figure S4) and f is the emission state oscillator strength, taken from TD-DFT geometric optimization calculation of S1 (Figure S3). Therefore, τr of Tet-v2.0 by itself can be calculated as ~920 ns, similar to the 850 ns radiative lifetime of s-tetrazine (50). Based on the FQY (1.2×10−3) of Tet-v2.0, τFL was calculated to be ~1.1 ns from equation (2) for free Tet-v2.0 in solution, which is longer than the aforementioned FRET timescales.

2.4. Rational Design for Higher Bioorthogonal Fluorogenicity of GFP-Based Probes

Based on the inhomogeneous population of GFP150-Tet, it is imperative to eliminate the existence of P3 (i.e., miniscule κ2 and hindered FRET) to effectively improve its fluorogenicity. We devised two strategies on the basis of Tet-v2.0 local environment (Figure 3d). First, we could mutate Tyr200 and/or Tyr151 to aliphatic residues with short sidechains (e.g., Ala), which may reduce steric hindrance around Tet-v2.0 (i.e., more free) to improve the FRET efficiency by decreasing P3 population and increasing P2 population. Assuming we could achieve 100% P2 with 0.12 ns time constant, would become 0.035, resulting in a fluorescence turn-on ratio of ~18. However, this type of mutation possesses the risk of destabilizing the β-barrel structure and allowing more solvent exposure to the chromophore, which may reduce GFP fluorescence after it is turned on. Second, Ser202 may be mutated to Tyr and potentially π-π stack with Tet-v2.0 at position 149 to trap it in a specific geometry (i.e., more tight), which could resemble P1 configuration. This way, the β-barrel structure can retain its stability. Assuming 100% P1 could be obtained, the highest fluorescence turn-on ratio would be ~120. However, the exact effect is unpredictable due to the unknown trapping geometry, while it is unrealistic to expect only good orientations.

Following both strategies, we performed single-site mutations of Y151A, Y200A, S202Y, and a double mutation of Y151AY200A for GFP150-Tet, then reacted these proteins with sTCO to examine the fluorescence recovery properties. Similar to sfGFP and GFP150-Tet (Figure S9), all mutants show a strong/weak absorption peak at ~490/400 nm due to deprotonated/protonated forms, and excitation of the deprotonated form leads to a largely conserved fluorescence peak at ~510 nm, indicating that these mutations do not significantly change the local environment of embedded chromophores (Figure 3). The relatively minor spectral shifts and protonation state change (also the chromophore pKa) (36) from sfGFP are caused by the intricate short and long-range electrostatic and steric effects, induced by the single/double point mutations and sTCO reactions around the tetrazine site. Notably, the interdipole distance and orientation between the tetrazine tag as acceptor and the embedded chromophore as donor still determine the intrinsic FRET efficiency and timescale.

We measured the FQYs of all variants before and after they react with sTCO (Table 2). Notably, the on-state FQYs of all Y-to-A mutants decrease (0.63, 0.57, and 0.56) versus sfGFP (0.65), implying that additional energy relaxation channels are opened due to the smaller sidechains of A than Y. In all three cases from Strategy 1, the Y200A mutant has the best fluorescence turn-on ratio of ~14. Notably, the enhanced fluorogenicity introduced by Y200A mutation is reduced by an additional Y151A mutation, which decreases the fluorescence quenching efficiency (off-state FQY increases from 0.042 in Y200A mutant to 0.068 in Y151AY200A double mutant), similar to the effect of a single Y151A mutation (off-state FQY increases from 0.070 in GFP-150Tet to 0.10 in GFP-150Tet-Y151A). These results indicate that the Y151A mutation may introduce more P3 population in addition to more P2 population, thus leading to a higher FQY. Based on Strategy 2, interestingly, the S202Y mutation led to the highest fluorescence turn-on ratio of ~31 and an even larger FQY (0.68) after reaction with sTCO when compared to sfGFP. In comparison to a report about the crystal and NMR structural investigation and rational improvement of FRET efficiency between two subunit chromophores inside a three-domain fusion FP-based calcium sensor Twitch-2B (46) and another report on the FRET pairs in fused FP dimers (47), our integrated fs-TA spectroscopy, MD simulations, and theoretical calculations enable a much more significant improvement of FRET efficiency for a standalone tetrazine-encoded GFP that manifests the highly desirable bioorthogonal fluorogenicity.

Table 2.

FQYs of rationally designed GFP150-Tet mutants (major improvements bolded)1

| GFP150-Tet mutants | FQY | FQY after reaction with sTCO | Turn-on ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y151A | 0.10 ± 0.002 | 0.63 ± 0.02 | 6.3 ± 0.3 |

| Y200A | 0.042 ± 0.001 | 0.57 ± 0.02 | 14 ± 0.6 |

| Y151AY200A | 0.068 ± 0.002 | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 8.2 ± 0.5 |

| S202Y | 0.022 ± 0.001 | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 31 ± 2 |

Error bars were calculated as two times the standard error at the 95% confidence level. Error propagation has been performed to obtain the error bars for the turn-on ratios.

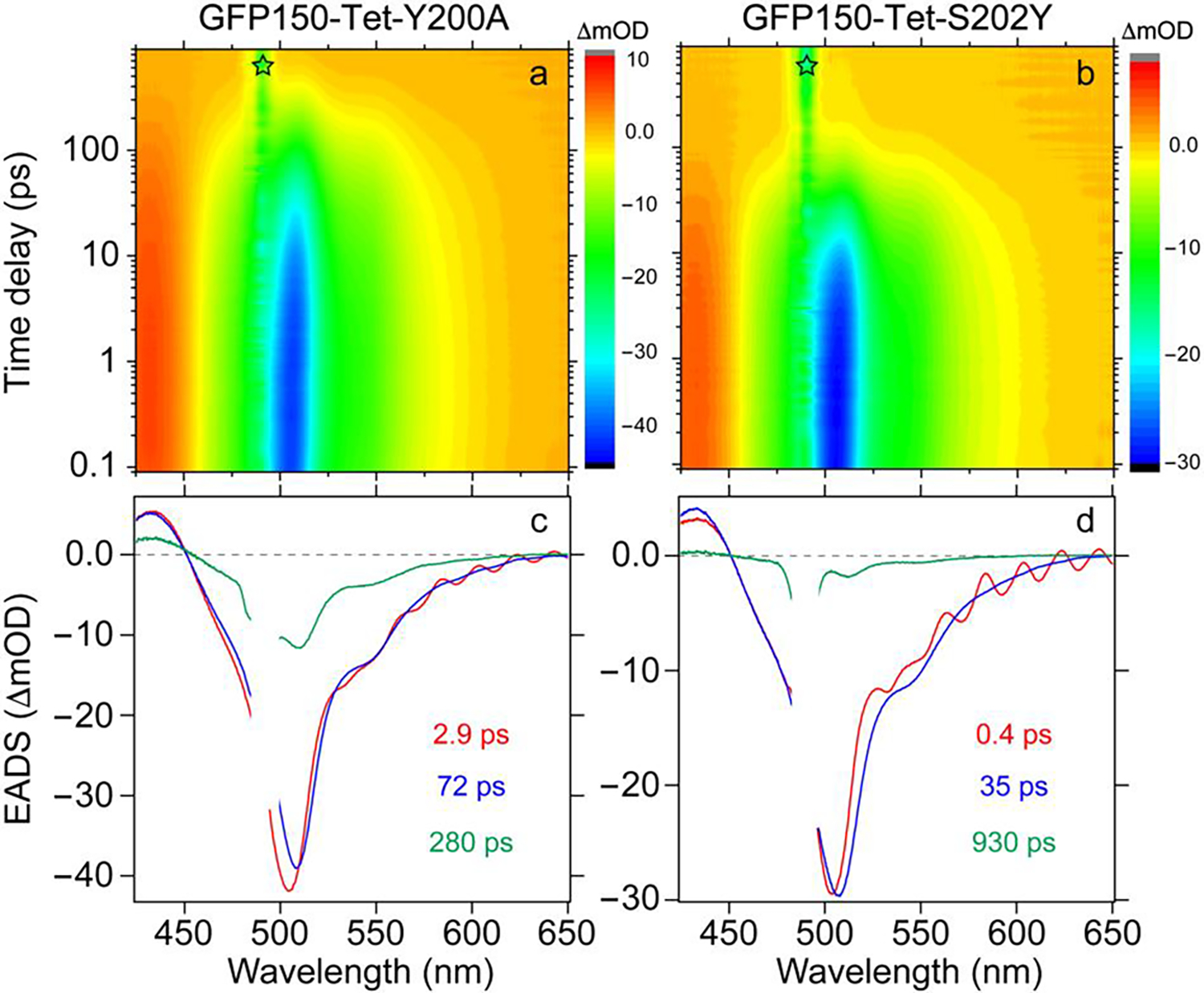

2.5. Tracking Fluorescence Quenching of the Newly Designed Bioprobes

To uncover fluorescence quenching mechanisms of these GFP150-Tet derivatives, especially the effect of Y200A and S202Y single mutations, we performed fs-TA measurements. All proteins exhibit similar ESA and SE bands (Figure 5, Figures S10 and S11) as sfGFP, GFP134-Tet, and GFP150-Tet (Figure 2), but decay on distinct timescales. Global analysis of fs-TA spectra of GFP150-Tet-Y200A yields three time constants of ~2.9, 72, and 280 ps, all of which are associated with noticeable SE band intensity loss and depopulation of the excited state (Figure 5a,c), substantiated by the probe-dependent fits (Figure S10e). Notably, the 2.9 ps lifetime far exceeds the ~18 ps FRET limit based on collinear TDMs (see above), while the SE peak displays a noticeable redshift. Therefore, this process is attributable to an extra rapid energy relaxation pathway caused by the Y-to-A mutation. This assignment is confirmed by fs-TA results of GFP150-Tet-sTCO-Y200A, wherein the FRET acceptor (Tet) is eliminated after reaction with sTCO, but this component remains (Figure S10c,e). The Y-to-A mutation likely leads to some β-barrel opening and more solvent-chromophore interactions, enabling the ultrafast depopulation pathways (36), corroborated by fs-TA results of other Y-to-A mutants also with ~2 ps time constants (Figure S11) and the reduced FQYs (Table 2).

Figure 5. Transient electronic dynamics of the newly designed GFP150-Tet mutants after 490 nm excitation.

(a–b) 2D-semilogarithmic contour plots of fs-TA spectra and (c–d) global analysis with the evolution-associated difference spectra (EADS) of GFP150-Tet-Y200A and GFP150-Tet-S202Y, respectively. The star denotes the pump laser scattering, and this region was omitted during spectral data analysis. The retrieved lifetimes are color-coded and listed in the insets.

The second time constant (72 ps, also termed P2 population herein) likely originates from the largely random-orientated Tet-v2.0 (due to extra space allowed by Ala200), which could adopt a closer distance to the chromophore than that in GFP150-Tet, thus showing a faster FRET time constant. The third time constant (0.28 ns) is owing to poor alignment between the donor and acceptor TDMs; however, this time constant is shorter than the last component in GFP150-Tet (0.92 ns) as a result of a more free environment for Tet-v2.0 with an adjacent Ala200. In addition, the P1 population in GFP150-Tet (18 ps lifetime) is not retrieved in GFP150-Tet-Y200A, which is likely converted (with the enhanced flexibility of acceptor TDM and reduced κ2) and becoming a part of the P2 population.

For GFP150-Tet-S202Y, following the initial solvation/relaxation of ~0.4 ps that does not change the SE peak intensity but still shows a small redshift, the majority of TA signal decays with a 35±2 ps time constant (Figure 5b,d and Figure S10f), corresponding to a 36±2 ps FRET lifetime. Since this mutation is unlikely to alter the distance between Tet-v2.0 and the chromophore (Figure 3d and 4c) with Y202 largely locking the tetrazine in place, the calculated FRET lifetime corresponds to an R0 of ~3.1 nm and κ2 of ~2.0. Moreover, similar to the P3 population in GFP150-Tet, the third time constant of 0.93±0.03 ns is generated from the Tet-v2.0 and chromophore pairs with poor TDMs alignment. The S202Y mutation does not greatly modify the orientation of this species (mainly regarding the acceptor Tet), but significantly decreases its population (Figure 5d versus Figure 2f). The relative population ratio of the two species (i.e., P1 and P3) can be estimated by their SE peak intensities from global analysis as ~94% and 6%. Combining with their associated time constants of 0.035 and 0.93 ns (mean values) while is ~2.3 ns from GFP150-Tet-sTCO-S202Y (see Figure S10d,f to represent the parent protein sfGFP-S202Y), the average FRET efficiency was calculated to be 96%, matching the 97% efficiency based on FQYs (error propagation shows one standard deviation well below 1%). This remarkably quantitative result confirms that our rationally designed S202Y mutant can successfully trap the TDM of Tet-v2.0 to be in good alignment with the chromophore TDM and significantly increase FRET efficiency when GFP is turned off, thus leading to a much enhanced fluorogenicity (Table 2). We note that our predictions and rational design principles are derived from real measurements of the proteins in solution and do not rely on crystallographic structural data that may not accurately represent protein conformations in solution or in cells.

2.6. Achieving High Fluorogenicity in Eukaryotic Cells

The background (off-state) fluorescence of the conventional GFP-Tet tags hinders their use in eukaryotic cells for rate calculation and as a tool for turn-on probing, which can be improved by GFP-Tet probes with higher fluorogenicity. Moreover, our newly designed and strategic S202Y mutation was able to significantly quench the fluorescence of GFP150-Tet in the absence of sTCO and can even slightly enhance the fluorescence after reaction with sTCO (i.e., FQY increases from 0.65 in sfGFP to 0.68 in GFP150-Tet-sTCO-S202Y, see Tables 1 and 2). Therefore, we proceeded to evaluate the suitability of a GFP150-Tet-S202Y system for imaging in live eukaryotic cells, thus providing a proof-of-principle and generalizable application of our “bottom-up” rationally designed sfGFP mutants. Since GFP-Tetv2.0 is not compatible with human cells due to the lack of GCE machinery for it that is orthogonal in eukaryotic cells, we implemented a newer version of the Tet-ncAA family with tetrazine ring on the meta-position of the phenylalanine, Tet-v3.0-Bu (Figure 6a) (30), and encoded the tag into GFP150-Tet and GFP150-Tet-S202Y in live HEK293T cells (Figure 6b) (10). Because the steric packing of the Tet-ncAA inside the protein is mainly determined by the phenyl ring close to the α-carbon of the amino acid (Figure 3d), we anticipate that Tet-v3.0-Bu still exhibits a similar effect as Tet-v2.0 as revealed by ultrafast spectroscopy and MD simulations (see above) upon S202Y mutation of the protein.

Figure 6. Effect of S202Y mutation on the sfGFP-Tet fluorogenicity in live eukaryotic cells.

(a) Chemical structure of Tet-v3.0-Bu with a butyl functional group. (b) Comparative fluorescence intensities between GFP variants with Tet-v3.0-Bu before (yellow) and after (green) reaction with sTCO-OH in live HEK293T cells. Red “+” signs represent the wild-type (WT)-sfGFP in the presence of free Tet tags as control samples.

Notably, the fluorescence of GFP150-Tet protein is enhanced after reaction with sTCO, leading to a fluorogenicity around ~1.6 (Figure 6b). In sharp contrast, the GFP150-Tet-S202Y protein emits weaker fluorescence before adding sTCO and stronger fluorescence after adding sTCO compared to the fluorescence intensities in GFP150-Tet, manifesting a similar in-cell trend as the in vitro (in-solution) studies with Tet-v2.0 (Tables 1 and 2). The fluorogenicity of GFP150-Tet-S202Y in eukaryotic cells was improved to ~3.0, almost double the value in the parent protein. As a useful control, wild-type (WT)-sfGFP was also expressed in the presence of Tet-v3.0-Bu (but without incorporation in the protein matrix) and its fluorescence only shows a slight decrease after the addition of sTCO (Figure 6b). We note that the magnitude of difference for in-cell brightness (Figure 6) differs from the corresponding in-solution FQY changes (see GFP150-Tet in Table 1 versus GFP150-Tet-S202Y in Table 2), though the change trend is in the same direction. These results could be due to the use of Tet-v3.0-Bu construct in cells and also from differences in the measured FQY from total brightness. In other words, though the spatial variation in protein matrix due to the chemical structure difference between the two tetrazine tags as well as the additional complexity of predicting actual cellular environments likely cause some deviation from a quantitative match to our FRET calculation predictions (see above), the increased fluorogenicity in a designed single-mutant protein is conspicuous. The improved fluorescence turn-on ratio is an exciting advance because it paves the way for measuring the biomolecular rate constants and cellular uptake rates of nonfluorescent probes in eukaryotic cells with higher signal-to-noise ratios, which provides an illuminating roadmap for future bioengineering and bioimaging endeavors.

3. Conclusions

In this work, a series of sfGFP variants with site-specific modification of Tet-v2.0 that can quench fluorescence to different extents were developed with their intrinsic quenching mechanisms elucidated by ultrafast electronic spectroscopy, molecular dynamics simulations, and quantum calculations in a rigorous quantitative manner. In contrast to wild-type sfGFP, the fluorescence of GFP134-Tet and GFP150-Tet is quenched by FRET, validated by distances between TDMs of the protein chromophore and tetrazine moiety from MD simulations. Notably, GFP150-Tet exhibits a trimodal heterogeneity (P1, P2, and P3 subpopulations) on the ground state, originating from a good, random (in-between average), and poor TDMs alignment between the embedded chromophore (largely conserved environment) and the exposed Tet-v2.0 at site 150, resulting in a reduced fluorogenicity (~9 fold) without reaching its full imaging potential. This unique line of inquiry unambiguously reveals typically hidden molecular mechanisms that power the highly desirable and beneficial fluorescence modulation for a “minimally” tagged protein as a biosensor.

Equipped with these ultrafast electronic spectroscopic insights, we rationally designed a set of mutants surrounding the Tet-ncAA on GFP, and two point mutations of Y200A (more flexibility) and S202Y (more trapping) successfully increase the subpopulations of P2 and P1, respectively. The Y200A mutant increases the fluorescence turn-on ratio to ~14 by introducing more P2 species, but also opens additional energy relaxation pathways besides FRET. The S202Y mutant traps the acceptor (Tet-v2.0) in a good TDM alignment relative to the donor (chromophore) with ~36 ps FRET lifetime (P1 species) and effective fluorescence quenching, thus achieving a high fluorogenicity of ~31 fold and representing a more than 3-fold increase from the parent protein (GFP150-Tet). The uncovered fluorescence quenching mechanism in action bridges the current gap between fundamental chemistry and bioimaging applications (1, 10, 21, 51), demonstrated by a notably improved fluorescence turn-on ratio observed in our recently engineered GFP150-Tet-S202Y mutant with a Tet-v3.0-Bu tag that works in eukaryotic cells. Furthermore, the rational design of proteins with a gain of function has established an essential knowledge base and feedback loop to efficiently design next-generation noninvasive and bioorthogonal toolkits, so one could envision watching single eukaryotic cells where the GFP-Tet label in different organelles turns on at different rates as the sTCO-probe gains differential access. These mechanistic insights and spectroscopy-guided advances in physiological environments will help to elucidate a myriad of biological processes from ligand binding, allostery, signaling, catalysis, to cooperativity, and accelerate optogenetic and therapeutic applications.

4. Experimental Methods

4.1. Protein Sample Preparation

The plasmids used in this study were constructed using methods analogous to those previously described (29, 31). To generate the strains used for protein expression (Table 3), a pBAD plasmid containing a superfolder (sf)GFP construct, and where appropriate, a pDule1 plasmid housing the genetic code expansion machinery required for Tet2.0 encoding were co-transformed into Escherichia coli (E. coli) DH10B cells, recovered, and stored as a frozen glycerol stock. Prior to protein expression, a glycerol stock of the desired E. coli strain was used to inoculate an overnight culture. The following day, this overnight culture was used to inoculate 50 mL of auto-induction media (52) containing 500 μM Tet2.0 (synthesized as previously described (29)), 0.05% (w/v) arabinose, and appropriate antibiotics at 2% inoculum. These cultures were grown for 24 h at 37 °C and at 250 rpm in an orbital incubator-shaker prior to harvesting by centrifugation at 5,000 relative centrifugal force (rcf). Pelleted cells were resuspended in TALON Wash buffer (50 mM Na2HPO4, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM Imidazole, pH 7.0), then microfluidized using an M-110P microfluidizer (Microfluidics International Corp., USA) at 18,000 psi and the resulting lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 20,000 rcf for 30 minutes at 4 °C. This clarified lysate was then incubated with TALON Ni-NTA resin for 60 minutes at 4 °C to allow the protein to bind. After binding, the resin was loaded into a fritted column, washed with 50 column volumes of TALON Wash buffer, eluted into 2.5 mL of TALON Elution buffer (50 mM Na2HPO4, 500 mM NaCl, 250 mM Imidazole, pH 7.0), desalted into PBS (50 mM Na2HPO4, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.0) and stored at 4 °C until needed. In instances where the protein was reacted with hydroxylated strained trans-cyclooctene (nonplanar, sTCO-OH), this compound (synthesized as previously described (53)) was added at approximately 10 molar equivalents to sfGFP samples and allowed 15 minutes to react completely prior to desalting to remove excess sTCO-OH.

Table 3.

Plasmids and strains used in this study

| Name | Promoter | Resistance | Addgene ID |

| pBAD-sfGFP-WT | araBAD | Ampicillin | 85482 |

| pBAD-sfGFP-134TAG | araBAD | Ampicillin | - |

| pBAD-sfGFP-150TAG | araBAD | Ampicillin | 84583 |

| pBAD-sfGFP-Y151A | araBAD | Ampicillin | - |

| pBAD-sfGFP-Y200A | araBAD | Ampicillin | - |

| pBAD-sfGFP-Y151A+Y200A | araBAD | Ampicillin | - |

| pBAD-sfGFP-S202Y | araBAD | Ampicillin | - |

| pDule1-Tet2.0 | lpp (aaRS), glnS (tRNA) | Tetracycline | 85496 |

| Strains used in this study | |||

|

| |||

| Plasmid 1 | Plasmid 2 | Resistance | |

| pBAD-sfGFP-WT | - | Ampicillin | |

| pBAD-sfGFP-134TAG | pDule1-Tet2.0 | Ampicillin + Tetracycline | |

| pBAD-sfGFP-150TAG | pDule1-Tet2.0 | Ampicillin + Tetracycline | |

| pBAD-sfGFP-Y151A | pDule1-Tet2.0 | Ampicillin + Tetracycline | |

| pBAD-sfGFP-Y200A | pDule1-Tet2.0 | Ampicillin + Tetracycline | |

| pBAD-sfGFP-Y151A+Y200A | pDule1-Tet2.0 | Ampicillin + Tetracycline | |

| pBAD-sfGFP-S202Y | pDule1-Tet2.0 | Ampicillin + Tetracycline | |

4.2. Cloning sfGFP-S202Y into pAcBac1

Eukaryotic optimized genes for sfGFP-S202Y were created using overlap extension polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the template pAcBac1 Mb sfGFP 150TAG (30). Two PCR fragments were generated flanking the S202Y mutation using sfGFP-S202Y Fwd and sfGFP-S202Y Rev paired with pAcBac_sfGFP_for and pAcBac_sfGFP_rev primers. Those fragments were then amplified together using the pAcBac_sfGFP_for and pAcBac_sfGFP_rev primers to produce the sfGFP-S202Y gene. The final PCR product and pAcBac1 sfGFP150 template were digested with the restriction enzymes EcoR1 and NheI. The desired fragments were gel purified and ligated into the pAcBac1 backbone. The ligated product was sequenced to confirm identity. Identity of ligation products was confirmed by sequencing.

pAcBac_sfGFP_for :

5’- GACTCACTATAGGGAGACCCAAGCTGGCTAGCACCATGGTTTCTAAAGGTG-3’

pAcBac_sfGFP_rev :

5’- GGTTGATTGTCGACTTAACGCGTTGAATTCTTAGTGGTGATGGTGGTGATGAGTAG -3’

sfGFP-S202Y Fwd :

5’- ATCATTATCTGTATACCCAGAGCGT -3’

sfGFP-S202Y Rev :

5’- ACGCTCTGGGTATACAGATAATGAT -3’

4.3. Transfection of HEK Cells

Human embryonic kidney (HEK)293T cells were plated in a 24-well plate at ~40% confluency so that they reached 70–90% confluency at the time of transfection. The cells were transfected using jetPRIME®, DNA and siRNA transfection reagent using the manufacturer’s protocol with minor modification. Briefly, per well, 600 ng of plasmid DNA was diluted in 50 μL of jetPRIME® buffer and vortexed for 10 seconds. Then, 1.2 μL of jetPRIME® reagent was added to the DNA / jetPRIME® buffer mixture and vortexed for 1 second. They were then incubated for 20 min at room temperature before adding to cells, transfected at a 8:1 Gene-of-Interest:Synthetase ratio using pAcBac sfGFP:pAcBac R284 synthetase). Tet-v3.0-Bu noncanonical amino acid (ncAA, 30 μM) was added to the cells immediately and incubated for 24 hrs (30).

4.4. Labeling with sTCO-OH

After the 24-hour expression, the media on the cells was changed three times to remove excess amino acid before adding the label. The cells were then lifted and split into two eppendorf tubes. One tube was left with no addition, while in the other 10 μM sTCO-OH was added and allowed to incubate for 60 minutes.

4.5. Flow Cytometry

HEK293T cells were washed twice with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), resuspended in 200 μL DPBS, and put in a 96-well plate for flow cytometry. In total, 5000 events were collected using CytoFLEX (Beckman Coulter) and CytExpert software Version 2.2 (Beckman Coulter). Dead cells and cell aggregates were excluded from analysis by gating and doublet discrimination. The ratio and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the emitting GFP populations (for the selected 700 events that fall within the flow gating set to GFP-expressing cells, all samples in duplicate with individual expressions, labeling, and sorting) were calculated using CytExpert software. The error bars for standard deviation of the 700 cells (Figure 6b) were based on the average of both biological replicates.

4.6. Imaging using Keyence Microscope

HEK293T cells were imaged in the 24-well plates wherein they were transfected. Fluorescence images were captured using the Keyence BZ-X810 Fluorescence Microscope system at 4× magnification. The GFP signals were collected using the GFP fluorescence setting with exposure normalized to wild-type sfGFP (30, 32).

4.7. Ground State Spectral and Quantum Yield Measurements

The electronic absorption spectra of all samples were measured using the UV/Visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Evolution 201) at room temperature (22 °C). Protein samples were prepared in a phosphate buffer (50 mM Na2HPO4, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.0). To obtain the absorption properties of Tet-v2.0, sTCO-OH, and their reaction product, they were dissolved in the same aqueous buffer of sfGFPs with 10% (v/v) DMF. For Figure 1b above, we collected the absorption spectra of ~2.0 mM Tet-v2.0, 3.1 mM sTCO-OH (i.e., sTCO), and their products. For transient absorption (TA) experiments, the optical density (OD, unitless) of all sfGFP mutants were kept between ~0.2–0.3 per mm at ~490 nm (excitation wavelength) while the OD of Tet-v2.0 was ~0.16 per mm at ~520 nm.

The fluorescence spectra were collected via a spectrofluorophotometer (SHIMADZU RF-6000) with 3.0 nm excitation and emission bandwidth and low sensitivity. Fluorescence quantum yields (FQYs) of all the sfGFP mutants were measured using sfGFP (FQY=0.65, see Table 1 above) (32) as the standard with 480 nm excitation, and the FQY of Tet-v2.0 in water was obtained by using rhodamine 6G (FQY=0.95 in ethanol) (54) as the standard after 520 nm excitation (55).

The spectral overlap between the donor fluorescence profile and acceptor absorbance profile, termed J(λ), can be calculated by the following equation (42, 46):

| (10) |

where fD (λ) represents the integrated fluorescence intensity across the wavelength range of the donor, and εA (λ) is the extinction coefficient (in M−1·cm−1 unit) of the acceptor at the wavelength λ (in nm unit). This spectral overlap parameter in equation (10) thus has the unit of (M−1·cm−1·nm4), which allows the calculation of the Förster radius (R0) between the pair of chromophores (43) using the most convenient choice of units (e.g., Avogadro’s constant, and 1 L=1,000 cm3), as well as the index of refraction of medium (1.33 for water at room temperature). We did not record any uncertainties for the J(λ) value from direct integrations of data points over selected wavelength ranges. These calculations allow us to quantitatively evaluate FRET in action from the sfGFP “core” chromophore to “surface” tetrazine on intrinsic molecular timescales as exposed by the systematically collected fs-TA spectra on sfGFP, GFP134-Tet, GFP150-Tet, as well as the rationally designed and prepared single-site mutants (GFP150-Tet-Y151A, Y220A, and S202Y) and a double mutant (GFP150-Tet-Y151AY220A) before and after reaction with sTCO in aqueous buffer solution.

4.8. Femtosecond Transient Absorption (fs-TA) Spectroscopy

Our fs-TA setup was built on the basis of a 1 kHz-repetition-rate Ti:sapphire regenerative amplifier (Legend Elite-USP-1K-HE, Coherent, Inc.) which produces the ~800 nm fundamental pulses with ~35 fs duration and ~3.7 W power (56, 57). In brief, the fs 490 nm photoexcitation pulse train was generated from a home-built two-stage fs noncollinear optical parametric amplifier (NOPA) system and then compressed by a chirped mirror pair (DCM-12, 400–700 nm, Laser Quantum, Inc.). The probe pulse as supercontinuum white light was produced by focusing a portion of the fundamental laser output onto a 2-mm-pathlength deionized-water-filled quartz cell (Spectrosil 1-Q-2, Starna Cells, Inc.), then passed through a chirped mirror pair (DCM-9, 450–950 nm, Laser Quantum, Inc.) for temporal compression (57). The actinic pump power was set at ~0.25 mW by using a circular variable metallic neutral density (ND) filter (50FS04DV.4, Newport, Inc.). The pump and probe pulses were both focused by a reflective parabolic mirror on the 1-mm-pathlength quartz flow cell (Spectrosil 48-Q-1, Starna Cells, Inc.) filled with sample solution at room temperature. We note that tetrazine is not photostable over a long period of time, so we stored samples (both free tetrazines and GFP-Tet variants) in the dark inside a 4 °C fridge and only took them out before each fs-TA experiment and then immediately put them back after each measurement. Our flow cell and low actinic pump power did not cause any notable damage to sample solution during the experiments (Figure S8). Past the sample in our optical setup, the probe beam was collimated and focused into a spectrograph (IsoPlane SCT-320, Princeton Instruments, Inc.), dispersed by a reflective grating (300 grooves/mm, 300 nm blaze wavelength), and then imaged on a CCD array camera (PIXIS:100F, Princeton Instruments, Inc.) for spectral data collection and processing.

The sample solution linear flow rate was measured at 0.12 mL/s in our flow cell with a dimension of 0.8 × 0.1 × 4 cm3 (L × W × H) and a total volume of 0.3 mL (48-Q-1, see above). The diameter of actinic pump spot size was ~150 μm, hence it takes ~10 ms for the sample to flow out of the pump laser spot. In our experiments, each spectral data point was collected with 3000 laser shots at 1 kHz repetition rate, with a phase-stable optical chopper synchronized at 500 Hz, so there are five laser pulses acting as the fs pump (with the corresponding fs probe) before the sample is completely replenished, then repeated for 300 times consecutively to increase the signal-to-noise ratio. The data were collected from −2 to 900 ps with 50 fs steps from −100 fs to 2 ps, 0.2 ps steps from 2 to 4 ps, 0.5 ps steps from 4 to 10 ps, 5 ps steps from 10 to 100 ps, and 50 ps steps from 100 to 900 ps. Given the typical ns lifetimes of protein chromophores in this work, our measurement scheme is sufficient in recording high-quality ultrafast electronic spectra that accurately track the chromophore dynamics and enable a systematic comparison between related GFP-Tet protein systems.

4.9. Quantum Chemical Calculations

We optimized the electronic ground (S0) / first singlet excited (S1) state structure of s-tetrazine, Tet-v2.0, and Tet-sTCO with density functional theory (DFT) / time-dependent (TD)-DFT methods, RB3LYP functional and 6–311G+(d,p) basis sets using the Gaussian16 software (37). The bulk solvent was modeled with the default IEFPCM (solvent = water) method. The excitation energy from S0 to S1 of these molecules were calculated at the S0 optimized structures with TD-DFT method whereas the fluorescence energy from S1 to S0 can be directly retrieved from the S1 optimization calculation. Although Tet-v2.0 and Tet-sTCO are noncanonical amino acids, we only kept their sidechains for these calculations (e.g., absorption, emission, oscillator strength, and dipole moment) because other parts of the residue do not conjugate with the tetrazine unit and have minimal effect on the electronic properties, while the calculation complexity and cost can be effectively reduced. For a direct comparison between dipole moments, only the sidechain of ASN was optimized in the electronic ground state (Figure S3, bottom panel). The transition dipole moments of the protein chromophore (4’-hydroxybenzylidene-2,3-dimethyl-imidazolinone, or p-HBDI) (58, 59) and Tet-v2.0 were obtained from the output (*.log) file of the TD-DFT energy calculation at the ground-state (S0) optimized structure.

4.10. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

We performed 50 ns MD simulations on the tetrazine mutant proteins to assess how point mutations affect the chromophore environment. We used the July 2020 version of the CHARMM force field to describe the atomic forces throughout the simulations (60). The protein chromophore was described by the previously published parameters (61). The tetrazine amino acid, however, does not have published parameters available. As a result, we used the Force Field Toolkit (FFTK) (62) plugin in VMD (63) in combination with Gaussian 16 software (37) to generate force-field parameters for this moiety. We created an initial estimate of its parameters using the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) program (64–66). We subsequently refined these estimates though FFTK using methods described previously. Briefly, we performed geometrical optimization of the tetrazine sidechain in Gaussian using an MP2/6–31G* level of theory. Partial charges on the tetrazine were estimated using the water interaction method (61). Similarly, we determined target data for bond and angle parameters through Hessian calculations, and we used molecular mechanics calculations in NAMD (67) to find appropriate parameters to match the target data. Finally, we determined the dihedral parameters by calculating the potential energy surface (PES) of molecular dihedrals using quantum calculations, and then we selected the parameters that accurately reproduced this PES when the molecule was simulated in NAMD. This procedure completed the parameterization of the tetrazine sidechain, which was provided in “Tetrazine Amino Acid Parameters” (see the Computational Appendix in Supporting Information).

After defining all the interaction parameters, we simulated three protein systems: the wild-type sfGFP (PDB: 2B3P) (32), sfGFP with a tetrazine point mutation at residue position 133 (tag site 134), and sfGFP with a tetrazine at residue position 149 (tag site 150, see Figure 1a). Tetrazine molecules were added to the mutant systems using PyMOL (68). Each system was padded with a 14 Å TIP3P water box, which was then neutralized and ionized to 0.1 M concentration using Na+ and Cl− ions. The topology preparation, solvation, and ionization were performed through the VMD program (63). Each protein system underwent four steps during each simulation: an energy minimization protocol, a constant pressure (NPT) equilibration, a constant volume (NVT) equilibration, followed by a constant-pressure production step. Simulations were conducted with a 2 fs time step and periodic boundary conditions. The electrostatics were calculated every other time step through a Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) with a 1 Å grid spacing (69). Van der Waals interactions used a switching scheme with a 12 Å cutoff and 10 Å switching distance. Non-bonded interactions were excluded using the scaled 1–4 scheme, which a 1.0 scaling constant for 1–4 pairs. All bonds connected to hydrogen were maintained at a constant length using SHAKE algorithm (70). The simulations maintained a constant temperature of 300 K using Langevin dynamics, with a 5 ps−1 damping coefficient that was applied to all non-hydrogen atoms. During the aforementioned NPT equilibration and production simulations, the pressure of the system was maintained at a constant 1 bar using a Nosé-Hoover Langevin piston (100 fs oscillation period, 50 fs decay, and 300 K target temperature). Energy minimization consisted of 50,000 conjugate gradient steps. Subsequently, each equilibration step lasted for 1 ns, where harmonic restraints were applied to the backbone atoms. During the NPT equilibration, a constant 10 kcal·mol−1·Å−2 restraint relative to the starting configuration was applied throughout. These restraints were gradually released during the NVT equilibration: 10 kcal·mol−1·Å−2 was applied during the first 0.25 ns, followed by 5 kcal·mol−1·Å−2 for the next 0.25 ns, 1 kcal·mol−1·Å−2 for the next 0.25 ns, and no restraints for the remaining 0.25 ns. Finally, a production simulation, which formed the basis for the subsequent analysis (as summarized in Figure 4b,c and Figure S6), was run for 50 ns.

The atomic trajectories were analyzed using the MDAnalysis library in Python. Snapshots from the production simulation were recorded every 20 ps for a total of 2500 frames. The distance distributions between atoms were approximated with kernel density estimation (KDE) in the Seaborn package using default parameters (Gaussian kernel, bandwidth selected using Scott’s rule) and presented in Figure 4 and Figure S6b.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Steady-state electronic absorption and emission spectra of sfGFP mutants.

Figure S2. Local environment of the chromophore (CRO) inside sfGFP.

Figure S3. Calculated electronic properties of s-Tetrazine (Tet), Tet-v2.0, Tet-sTCO, and the asparagine (ASN) sidechain.

Figure S4. Steady-state electronic spectroscopy of Tet-v2.0 in aqueous buffer.

Figure S5. Transient electronic dynamics of the tetrazine-encoded sfGFPs after reaction with sTCO.

Figure S6. Calculated range of dihedral angles and correlation with the separation between the transition dipoles of HBDI chromophore and Tet-v2.0 tag in GFP134-Tet and GFP150-Tet.

Figure S7. 2D-semilogarithmic contour plot of the fs-TA spectra of Tet-v2.0 in aqueous buffer upon 490 nm excitation.

Figure S8. Steady-state electronic absorption spectra of Tet-v2.0 in aqueous buffer before and after the fs-TA experiment with 490 nm excitation.

Figure S9. Steady-state normalized electronic absorption and emission spectra of sfGFP and GFP150-Tet mutants before and after reaction with sTCO.

Figure S10. Transient electronic dynamics of GFP150-Tet-sTCO with Y200A or S202Y single-site point mutations.

Figure S11. Transient electronic dynamics of two other GFP150-Tet mutants (Y151A and Y151AY200A) before and after reaction with sTCO.

Key points:

Ultrafast spectroscopy reveals FRET in action and inhomogeneous populations with different transition dipole moment alignments.

Rational protein design of two new superfolder GFP mutants with record-high fluorogenicity.

Bioimaging application of the designed bioorthogonal protein mutant in live eukaryotic cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) grants MCB-1817949 and CHE-2003550 (to C.F.) and MCB-2054824 (to R.A.M.), and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences grants RM1-GM144227 and R01GM131168 (to R.A.M.). This work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), supported by NSF grant ACI-1548562; the Bridges system was supported by NSF grant ACI-1445606 at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (PSC). We thank Dr. Cheng Chen and Taylor Krueger for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information (SI) for this article is available from the Wiley Online Library at DOI: 10.1002/ntls.XXXXX or from the author.

SI Computational Appendix: Tetrazine Amino Acid Parameters.

Data Availability Statement:

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supporting Information.

References

- 1.Sletten EM, Bertozzi CR, From mechanism to mouse: A tale of two bioorthogonal reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 666–676 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patterson DM, Nazarova LA, Xie B, Kamber DN, Prescher JA, Functionalized cyclopropenes as bioorthogonal chemical reporters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18638–18643 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng T, Hang HC, Site-specific bioorthogonal labeling for fluorescence imaging of intracellular proteins in living cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 14423–14433 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu H, Alexander SC, Jin S, Devaraj NK, A bioorthogonal near-infrared fluorogenic probe for mRNA detection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 11429–11432 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L, Tran M, D’Este E, Roberti J, Koch B, Xue L, Johnsson K, A general strategy to develop cell permeable and fluorogenic probes for multicolour nanoscopy. Nat. Chem. 12, 165–172 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devaraj NK, The future of bioorthogonal chemistry. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 952–959 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clavier G, Audebert P, S-tetrazines as building blocks for new functional molecules and molecular materials. Chem. Rev. 110, 3299–3314 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu H, Devaraj NK, Advances in tetrazine bioorthogonal chemistry driven by the synthesis of novel tetrazines and dienophiles. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 1249–1259 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Escudero D, Revising intramolecular photoinduced electron transfer (PET) from first-principles. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 1816–1824 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J, Jia S, Chen PR, Diels-Alder reaction–triggered bioorthogonal protein decaging in living cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 1003–1005 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackman ML, Royzen M, Fox JM, Tetrazine ligation: Fast bioconjugation based on inverse-electron-demand Diels−Alder reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 13518–13519 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knall A-C, Slugovc C, Inverse electron demand Aiels–Alder (iEDDA)-initiated conjugation: A (high) potential click chemistry scheme. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 5131–5142 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi S-K, Kim J, Kim E, Overview of syntheses and molecular-design strategies for tetrazine-based fluorogenic probes. Molecules 26, 1868 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bajar BT, Wang ES, Zhang S, Lin MZ, Chu J, A guide to fluorescent protein FRET pairs. Sensors 16, 1488 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dexter DL, A theory of sensitized luminescence in solids. J. Chem. Phys. 21, 836–850 (1953). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meimetis LG, Carlson JCT, Giedt RJ, Kohler RH, Weissleder R, Ultrafluorogenic coumarin–tetrazine probes for real-time biological imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 7531–7534 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee Y, Cho W, Sung J, Kim E, Park SB, Monochromophoric design strategy for tetrazine-based colorful bioorthogonal probes with a single fluorescent core skeleton. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 974–983 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shang X, Song X, Faller C, Lai R, Li H, Cerny R, Niu W, Guo J, Fluorogenic protein labeling using a genetically encoded unstrained alkene. Chem. Sci. 8, 1141–1145 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H, Conde J, Guerreiro A, Bernardes GJL, Tetrazine carbon nanotubes for pretargeted in vivo “click-to-release” bioorthogonal tumour imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 16023–16032 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johann K, Svatunek D, Seidl C, Rizzelli S, Bauer TA, Braun L, Koynov K, Mikula H, Barz M, Tetrazine- and trans-cyclooctene-functionalised polypept(o)ides for fast bioorthogonal tetrazine ligation. Polym. Chem. 11, 4396–4407 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukinavičius G, Umezawa K, Olivier N, Honigmann A, Yang G, Plass T, Mueller V, Reymond L, Corrêa IR Jr, Luo Z-G, Schultz C, Lemke EA, Heppenstall P, Eggeling C, Manley S, Johnsson K, A near-infrared fluorophore for live-cell super-resolution microscopy of cellular proteins. Nat. Chem. 5, 132–139 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wieczorek A, Werther P, Euchner J, Wombacher R, Green- to far-red-emitting fluorogenic tetrazine probes – synthetic access and no-wash protein imaging inside living cells. Chem. Sci. 8, 1506–1510 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao W, Tang J, Dai L, He X, Li J, Cai L, Liao P, Jiang R, Zhou J, Wu H, A general strategy to design highly fluorogenic far-red and near-infrared tetrazine bioorthogonal probes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 2393–2397 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Remington SJ, Green fluorescent protein: A perspective. Protein Sci. 20, 1509–1519 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dedecker P, De Schryver FC, Hofkens J, Fluorescent proteins: Shine on, you crazy diamond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 2387–2402 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manandhar M, Chun E, Romesberg FE, Genetic code expansion: Inception, development, commercialization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 4859–4878 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seitchik JL, Peeler JC, Taylor MT, Blackman ML, Rhoads TW, Cooley RB, Refakis C, Fox JM, Mehl RA, Genetically encoded tetrazine amino acid directs rapid site-specific in vivo bioorthogonal ligation with trans-cyclooctenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 2898–2901 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang K, Sachdeva A, Cox DJ, Wilf NM, Lang K, Wallace S, Mehl RA, Chin JW, Optimized orthogonal translation of unnatural amino acids enables spontaneous protein double-labelling and fret. Nat. Chem. 6, 393–403 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blizzard RJ, Backus DR, Brown W, Bazewicz CG, Li Y, Mehl RA, Ideal bioorthogonal reactions using a site-specifically encoded tetrazine amino acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 10044–10047 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jang HS, Jana S, Blizzard RJ, Meeuwsen JC, Mehl RA, Access to faster eukaryotic cell labeling with encoded tetrazine amino acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 7245–7249 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bednar RM, Jana S, Kuppa S, Franklin R, Beckman J, Antony E, Cooley RB, Mehl RA, Genetic incorporation of two mutually orthogonal bioorthogonal amino acids that enable efficient protein dual-labeling in cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 16, 2612–2622 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pédelacq J-D, Cabantous S, Tran T, Terwilliger TC, Waldo GS, Engineering and characterization of a superfolder green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 79–88 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beliu G, Kurz AJ, Kuhlemann AC, Behringer-Pliess L, Meub M, Wolf N, Seibel J, Shi Z-D, Schnermann M, Grimm JB, Lavis LD, Doose S, Sauer M, Bioorthogonal labeling with tetrazine-dyes for super-resolution microscopy. Commun. Biol. 2, 261 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsien RY, The green fluorescent protein. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 509–544 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fang C, Frontiera RR, Tran R, Mathies RA, Mapping GFP structure evolution during proton transfer with femtosecond Raman spectroscopy. Nature 462, 200–204 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fang C, Tang L, Mapping structural dynamics of proteins with femtosecond stimulated Raman spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 71, 239–265 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Li X, Caricato M, Marenich AV, Bloino J, Janesko BG, Gomperts R, Mennucci B, Hratchian HP, Ortiz JV, Izmaylov AF, Sonnenberg JL, Williams-Young D, Ding F, Lipparini F, Egidi F, Goings J, Peng B, Petrone A, Henderson T, Ranasinghe D, Zakrzewski VG, Gao J, Rega N, Zheng G, Liang W, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Throssell K, Montgomery JJA, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark MJ, Heyd JJ, Brothers EN, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Keith TA, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell AP, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Millam JM, Klene M, Adamo C, Cammi R, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Farkas O, Foresman JB, Fox DJ (2016) Gaussian 16, Revision A.03 (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT: ). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fang C, Tang L, Chen C, Unveiling coupled electronic and vibrational motions of chromophores in condensed phases. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 200901 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abbyad P, Childs W, Shi X, Boxer SG, Dynamic stokes shift in green fluorescent protein variants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 20189–20194 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang D, Li X, Zhang S, Wang L, Yang X, Zhong D, Revealing the origin of multiphasic dynamic behaviors in cyanobacteriochrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117, 19731–19736 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chattoraj M, King BA, Bublitz GU, Boxer SG, Ultra-fast excited state dynamics in green fluorescent protein: Multiple states and proton transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93, 8362–8367 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mondal SK, Ghosh S, Sahu K, Mandal U, Bhattacharyya K, Ultrafast fluorescence resonance energy transfer in a reverse micelle: Excitation wavelength dependence. J. Chem. Phys. 125, 224710 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patterson GH, Piston DW, Barisas BG, Förster distances between green fluorescent protein pairs. Anal. Biochem. 284, 438–440 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ansbacher T, Srivastava HK, Stein T, Baer R, Merkx M, Shurki A, Calculation of transition dipole moment in fluorescent proteins—towards efficient energy transfer. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 4109–4117 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.George Abraham B, Sarkisyan KS, Mishin AS, Santala V, Tkachenko NV, Karp M, Fluorescent protein based FRET pairs with improved dynamic range for fluorescence lifetime measurements. PLOS ONE 10, e0134436 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trigo-Mourino P, Thestrup T, Griesbeck O, Griesinger C, Becker S, Dynamic tuning of FRET in a green fluorescent protein biosensor. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw4988 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pope JR, Johnson RL, Jamieson WD, Worthy HL, Kailasam S, Ahmed RD, Taban I, Auhim HS, Watkins DW, Rizkallah PJ, Castell OK, Jones DD, Association of fluorescent protein pairs and its significant impact on fluorescence and energy transfer. Adv. Sci. 8, 2003167 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tucker MJ, Abdo M, Courter JR, Chen J, Smith AB, Hochstrasser RM, Di-cysteine s,s-tetrazine: A potential ultra-fast photochemical trigger to explore the early events of peptide/protein folding. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 234, 156–163 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strickler SJ, Berg RA, Relationship between absorption intensity and fluorescence lifetime of molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 37, 814–822 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alfano JC, Martinez SJ III, Levy DH, Time-resolved spectroscopy of 3-amino–s-tetrazine and 3-amino–6-methyl–s-tetrazine in a supersonic jet. J. Chem. Phys. 94, 2475–2481 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jemas A, Xie Y, Pigga JE, Caplan JL, am Ende CW, Fox JM, Catalytic activation of bioorthogonal chemistry with light (CABL) enables rapid, spatiotemporally controlled labeling and no-wash, subcellular 3D-patterning in live cells using long wavelength light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 1647–1662 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Studier FW, Protein production by auto-induction in high-density shaking cultures. Protein Expr. Purif. 41, 207–234 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Royzen M, Yap GPA, Fox JM, A photochemical synthesis of functionalized trans-cyclooctenes driven by metal complexation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3760–3761 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Magde D, Wong R, Seybold PG, Fluorescence quantum yields and their relation to lifetimes of rhodamine 6G and fluorescein in nine solvents: Improved absolute standards for quantum yields. Photochem. Photobiol. 75, 327–334 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]