Abstract

Patients with glioblastoma (GBM) have limited options and require novel approaches to treatment. Here, we studied and deployed nonfreezing “cytostatic” hypothermia to stunt GBM growth. This growth-halting method contrasts with ablative, cryogenic hypothermia that kills both neoplastic and infiltrated healthy tissue. We investigated degrees of hypothermia in vitro and identified a cytostatic window of 20° to 25°C. For some lines, 18 hours/day of cytostatic hypothermia was sufficient to halt division in vitro. Next, we fabricated an experimental tool to test local cytostatic hypothermia in two rodent GBM models. Hypothermia more than doubled median survival, and all rats that successfully received cytostatic hypothermia survived their study period. Unlike targeted therapeutics that are successful in preclinical models but fail in clinical trials, cytostatic hypothermia leverages fundamental physics that influences biology broadly. It is a previously unexplored approach that could provide an additional option to patients with GBM by halting tumor growth.

'Cytostatic' hypothermia dampens cellular pathways, safely halts glioblastoma growth in rats, and holds translational promise.

INTRODUCTION

Despite standard-of-care treatment, patients with glioblastoma (GBM) have a poor median survival of 15 to 18 months, and at best, ~7% survive 5 years after diagnosis (1, 2). This is due to the ineffectiveness of current therapies, resulting in nearly all GBMs recurring. More than 80% of recurrences are local (3–5), which provides a role for local therapies. Unfortunately, because of the traumatic effects of treatment, only 20 to 30% of the recurrences can be resected before recurring once more (6).

The ineffectiveness of current GBM therapies necessitates novel domains of therapeutics, such as manipulating physical phenomena like electric fields, topographical guidance, and temperature. For example, tumor-treating electric fields can disrupt mitosis and mildly affect overall survival (7, 8). Topological cues of aligned nanofibers can induce directional migration of GBM to a cytotoxic sink (9), and this strategy recently received U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) breakthrough status. Applying electric fields may also induce directional GBM migration (10). Both hyper- and hypothermia have been successfully used to kill tumor cells (11, 12). Thus, approaches that leverage physics may expand the repertoire of options available to GBM patients.

Hypothermia as a cancer therapy remains relatively underexplored and can be divided into two forms: cryogenic (freezing) and noncryogenic hypothermia. Currently, our only hypothermia-driven approach against cancer is cryosurgery (13). In the 1940s, neurosurgeon T. Fay first applied whole-body hypothermia to limit tumor growth, but it proved hazardous and infeasible (14). He then attempted locally freezing tumor in one glioma patient with a cryoprobe tethered to a “beer cooler.” However, the details of this case are unavailable (e.g., hypothermia degree, duration, intermittency, and follow-up), possibly due to hypothermia falling out of favor after being misused during World War II (15). Eventually, cryogenic freezing of brain tumors was reattempted, and cryosurgery was born (12, 16). However, subzero temperatures indiscriminately ablate diseased and healthy tissue (13, 17) and thus offer little advantage over current GBM therapies.

Alternatively, the healthy brain is resilient to noncryogenic hypothermia (14, 18, 19). In addition, temperatures of 32° to 35°C may be neuroprotective after injury (20). This moderate hypothermia reduces cell metabolism, oxygen and glucose consumption, edema, excitotoxicity, and free radical formation (20). In epilepsy, cortical cooling devices can halt seizures in primates (19, 21) and intraoperatively in patients (22). Thus, noncryogenic hypothermia could have therapeutic utility without notable cortical damage.

This study proposes noncryogenic hypothermia to halt brain tumor growth in awake and freely moving rodents. We first identify a window of temperatures that safely halts cell division, and we term this range “cytostatic hypothermia.” Our approach validates and expands upon suggestions from in vitro studies (23–28), including one from 1959 (14), that hypothermia can reduce cell proliferation. We investigate the effects of the degree and duration of hypothermia on the growth and metabolism of multiple human GBM lines in vitro. We also explore the effect of concomitant hypothermia with chemotherapy and chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR T) immunotherapy in vitro. Next, we computationally model and fabricate an experimental device to deliver cytostatic hypothermia in vivo for rats to demonstrate proof of concept. We then test the application of cytostatic hypothermia in two GBM rat models. Grounded by our findings, we propose our vision of a patient-centric device. With this approach, we leverage temperature, a fundamental physical trait, to influence biology by simultaneously modulating numerous cellular pathways. Thus, the broad biological effects may not be species-specific (i.e., they may translate to humans). On the basis of our evidence and the potential for translation, cytostatic hypothermia could be a much needed option for patients who would otherwise succumb to GBM.

RESULTS

In vitro GBM growth is influenced by hypothermia

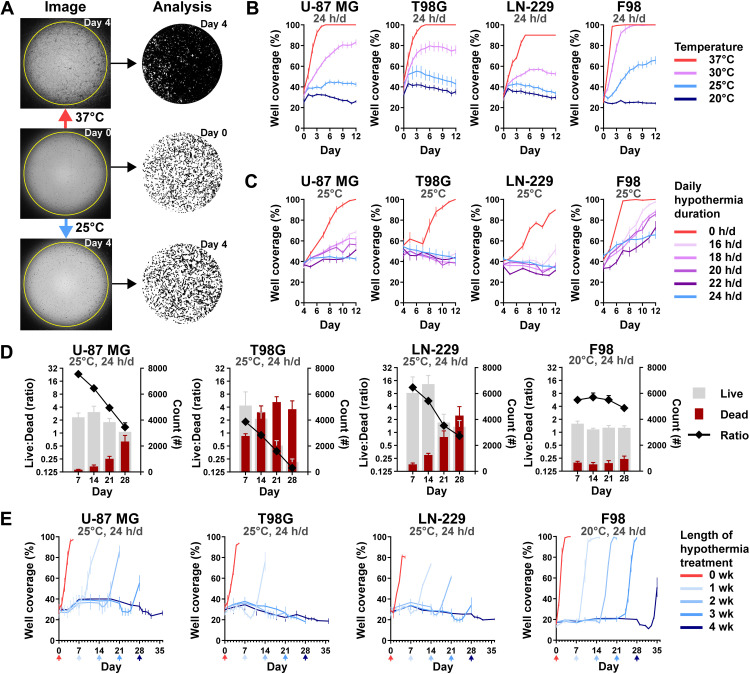

To investigate how different degrees of hypothermia affect cell growth rates, we cultured three human GBM cell lines and one rat GBM line at 20°, 25°, 30°, and 37°C. Growth was assessed daily through a custom live-cell imaging and analysis method we developed (Fig. 1A). It uses contrast and edge detection with optimized thresholds to identify tumor coverage as a proxy for growth in a two-dimensional (2D) well. All cell lines grew at 37°C (fig. S1A) and became fully confluent within 3 to 5 days (Fig. 1B). Reducing the temperature to 30°C reduced growth rates such that a significant (P < 0.0001) difference in cell coverage was present at 12 days with U-87 MG, T98G, and LN-229. Furthermore, three human GBM lines showed no growth at 25°C (Fig. 1B and fig. S1B), again demonstrating significantly reduced cell coverage by day 12 (P < 0.0001). While F98 (rat GBM) did have significantly reduced coverage at 12 days under 25°C (P < 0.0001), it required 20°C to halt growth (Fig. 1B and fig. S1C).

Fig. 1. Effect of continuous and intermittent cytostatic hypothermia on GBM cell lines in vitro.

(A) Tumor coverage analysis; photos (left) and resulting masks (right). Cells were incubated overnight in 96-well plates at 37°C (middle) and then incubated under either normothermia or hypothermia for 4 days (top and bottom). A custom ImageJ macro identified tumor from background and quantified confluence as “well coverage (%).” In the masks, cells are black, and background is white. (B) GBM growth curves (n = 8) via coverage at continuous 37°, 30°, 25°, or 20°C; statistical significance determined via two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons. (C) GBM growth rates under intermittent 25°C hypothermia after 25°C pretreatment (n = 8); statistical significance determined via two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons. (D) Live/Dead assay of GBM lines over time at cytostatic hypothermia temperatures (n = 8). Right y axis: number of living (gray) and dead cells (maroon); left y axis: ratio of Live:Dead cell. (E) Cell viability imaging assay (n = 8). Cells were grown at their cytostatic temperatures for 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 weeks and then incubated at 37°C for one final week (x-axis arrows indicate the date the color-corresponding plate was transferred). Statistical significance determined via two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons reported in Results with remaining statistics in table S1. All graphs show means ± SD.

To explore the minimum daily duration of cooling required to maintain cytostasis, we cycled the plates between 37° and 25°C incubators for a predefined number of hours per day (hours/day) (fig. S2A). The temperature change of the medium had a rapid phase followed by a slow phase, reaching the desired temperature within 30 to 60 min (fig. S2B). The growth rates of all cell lines were significantly reduced with as little as 16 hours/day of 25°C hypothermia compared to 37°C (fig. S2C). The application of 20 hours/day of 20°C hypothermia on F98 also reduced its growth rate compared to 25°C (fig. S2D). To assess whether an “induction” dose of hypothermia made cells more sensitive to intermittent hypothermia, we added a 4-day 25°C pretreatment period. Growth rates were significantly affected (Fig. 1C) such that T98G and LN-229 demonstrated equivalent coverage on day 12 compared to day 4 after 18 hours/day of hypothermia (P < 0.0001 at day 12 between 0 hours/day and all durations of hypothermia across all lines; F98 at 16 hours/day P = 0.0013) (Fig. 1C).

To assess cell viability after prolonged cytostatic hypothermia, we used a Live-Dead assay (Fig. 1D) at predetermined time points (7, 14, 21, and 28 days). In a separate assay, we monitored growth after returning the cells to 37°C (Fig. 1E). All GBM lines demonstrated a reduction in the Live:Dead ratio at their cytostatic temperatures (25°C for human lines and 20°C for F98), with T98G being the most affected and F98 being the least affected (Fig. 1D). Similarly, growth lagged after removal of 2 or 3 weeks of cytostatic hypothermia in all lines except for F98. Growth lagged in all lines (including F98) after 4 weeks, with significantly reduced well coverage 7 days after returning to 37°C (Fig. 1E and table S1) (7 days after 4 weeks versus 7 days after 0 weeks; U-87 MG, T98G, and LN-229 P < 0.0001 and F98 P = 0.0246).

As we observed morphological changes under hypothermia (fig. S1), we attempted to quantify these with the same custom imaging assay assessing circularity and average size. Compared to cell circularity after overnight incubation at 37°C (day 0), hypothermia significantly increased U-87 MG and LN-229 circularity (fig. S2E and table S2), while T98G remained unaffected. While F98 circularity significantly decreased with hypothermia over time, it displayed significantly greater circularity under 20°C compared to 25°C. Similarly, prolonged hypothermia significantly reduced the average cell size of U-87 MG and T98G (fig. S2F and table S3). F98 average cell size increased under 25°C but not under its cytostatic temperature of 20°C (fig. S2F and table S3).

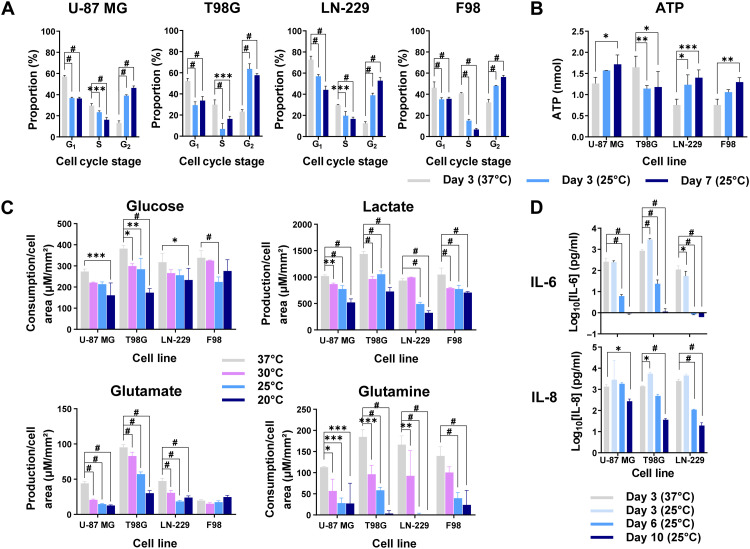

Hypothermia arrests the cell cycle and reduces metabolism and cytokine synthesis

To investigate the effects of cytostatic hypothermia on cellular activity, we assayed cell cycle, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels, metabolite production/consumption, and cytokine production under hypothermia. Cells grown for 3 days at 37°C were predominantly in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 2A). The application of 3 or 7 days of 25°C significantly shifted the portion of cells in G1 and S phases to the G2 phase across all lines (Fig. 2A). Next, we quantified intracellular ATP to investigate whether ATP production and consumption ceased. Intracellular ATP was significantly reduced in T98G but significantly increased in the remaining three lines under 25°C hypothermia (Fig. 2B and table S4). Next, we assayed medium glucose, lactate, glutamate, and glutamine at 0, 3, 7, and 14 days at 20°, 25°, 30°, and 37°C (Fig. 2C, fig. S3, and table S5). To account for cell growth under noncytostatic conditions, the data were normalized to tumor cell– occupied surface area using our imaging assay (Fig. 2C). Results demonstrated that any degree of hypothermia significantly reduced metabolite production and consumption. F98 glutamate production per unit cell area was not significantly different on day 3 (Fig. 2C) but remained low under 20°C (fig. S3D). Similarly, expression of inflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-8 from human GBM lines was significantly lower after 6 or 10 days of hypothermia (Fig. 2D). A mild but significant increase of both cytokines was observed after the first 3 days of 25°C from T98G, but it subsided by day 6. We did not detect expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-10, or the inflammatory cytokine interferon-γ (IFN-γ) under any condition.

Fig. 2. Effects of hypothermia on tumor cell cycle, metabolism, and cytokine synthesis.

(A) Percentage of cells in each stage of the cell cycle after 3 days of 37°C, 3 days of 25°C, or 7 days of 25°C (n = 3). (B) Amount of intracellular ATP from the tumor cell lines when grown for 3 days at 37°C, 3 days at 25°C, or 7 days at 25°C (n = 3). Specific adjusted P values are provided in table S4. (C) Metabolite production or consumption per cell surface area across cell lines and temperatures after either 3 days of 37°C or 3 days of hypothermia (30°, 25°, and 20°C) (n = 3). (D) Concentration of cytokines (IL-6 and IL-8) collected in the medium at different time points and temperatures (n = 3). All studies used two-way ANOVAs with post hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and #P < 0.0001). All graphs show means ± SD.

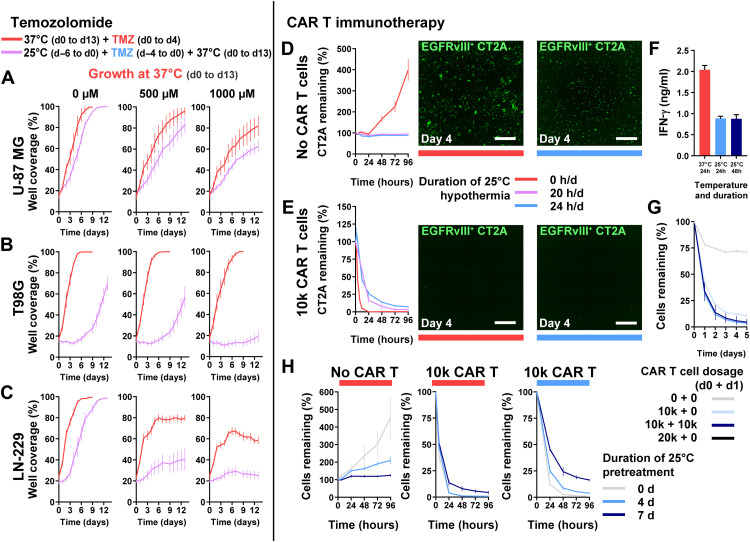

Adjuvants can function with cytostatic hypothermia in vitro

We next assessed whether cytostatic hypothermia would dampen temozolomide (TMZ) chemotherapy or CAR T immunotherapy in vitro. Human GBM lines received TMZ at one of three concentrations (0, 500, or 1000 μM) and at either 37° or 25°C followed by medium replacement and incubation at 37°C (for details, see Materials and Methods). There were no significant differences of well coverage on day 0 between 37° and 25°C for each cell line. However, all three lines had reduced well coverage 12 days after completion of treatment with 1000 μM TMZ compared to no TMZ [dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) only] under 25°C (Fig. 3, A to C). U-87 MG growth was significantly reduced on day 13 by combined TMZ and hypothermia compared to TMZ alone (at 37°C) (Fig. 3A) (37°C versus 25°C, 500 μM P = 0.0207 and 1000 μM P = 0.0292). Growth of T98G, a TMZ-resistant line, was significantly reduced by hypothermia alone and unaffected by 500 and 1000 μM TMZ alone (at 37°C) (Fig. 3B). However, the combination of 500 or 1000 μM TMZ with 25°C hypothermia had significantly delayed growth by day 13 (37°C versus 25°C, 500 μM TMZ P < 0.0001 and 1000 μM TMZ P < 0.0001). Similarly, LN-229 growth was significantly reduced by both TMZ and hypothermia individually, and the combination resulted in an enhanced effect (Fig. 3C) (37°C versus 25°C, 500 μM TMZ P < 0.0001 and 1000 μM TMZ P < 0.0001).

Fig. 3. Use of cytostatic hypothermia with chemotherapy and CAR T immunotherapy.

(A to C) Growth curves of U-87 MG, T98G, and LN-229 at 37°C with or without TMZ (DMSO only or 500 and 1000 μM TMZ) and either after or without hypothermia. Red line represents growth with concomitant TMZ chemotherapy from days 0 to 4 at 37°C and subsequent growth in fresh medium. Purple line represents growth at 37°C in fresh medium after completion of TMZ and 25°C hypothermia treatment (n = 8). Statistical significance determined via two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc test. (D and E) GFP+EGFRvIII+ CT2A tumor cells remaining after treatment without (D) and with 10,000 CAR T cells (E) under normothermia, or continuous or intermittent hypothermia (20 hours/day) (n = 4). Representative images of remaining tumor cells at day 4 after beginning treatment. White scale bars, 1000 μm. (F) IFN-γ quantification from the medium with EGFRvIII+ CT2A cells and CAR T cells. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test demonstrated a significant difference (P < 0.0001) between the 37°C and each of the 25°C groups. (G) Remaining CT2A cells with higher or multiple CAR T cell dosage over 2 days under 25°C hypothermia. (H) Remaining CT2A cells after pretreatment with 25°C hypothermia for 0, 4, or 7 days, followed by addition of 0 or 10,000 CAR T cells, and plate moved to either 37°C (left and middle) or 25°C (right). All graphs show means ± SD.

As CAR T immunotherapies against GBM are under investigation (29), we assessed whether CAR T–induced cytotoxicity (of EGFRvIII+ CT2A mouse glioma cells) was possible under cytostatic hypothermia. CAR T cells were chosen over other immunotherapies also as a proxy for plausible/best-case cellular immunological activity; if these did not function, there was little hope for other immunotherapies as all require immune cell functionality. We hypothesized that CAR T function would be abrogated under hypothermia. In the absence of CAR T cells, CT2A cell growth was inhibited by both 24 and 20 hours/day of 25°C hypothermia (Fig. 3D). Expression of the chimeric antigen receptor on T cells enabled killing of GFP+EGFRvIII+ CT2A cells and not GFP+EGFRvIII− cells at 37°C (fig. S4A). With the addition of 10,000 CAR T cells (5:1 ratio of T cell:tumor), EGFRvIII+ cells were eradicated within 24 hours at 37°C (Fig. 3E). Under 25°C hypothermia, 10,000 CAR T cells significantly reduced the glioma cells to 25% of the original count within 24 hours and to <10% by 96 hours. Reducing the hypothermia dosage to 20 hours/day further reduced the remaining tumor percentage (Fig. 3E). Reduced IFN-γ was detected in the medium when immune-mediated killing took place under hypothermia (Fig. 3F). Under hypothermia, adding a second dose of CAR T cells after 24 hours brought the remaining tumor to <5% of the original cell count (Fig. 3G). Pretreating CT2A cells with 25°C hypothermia for 4 to 7 days reduced their subsequent growth rate at 37°C (Fig. 3H, left). However, this reduced their susceptibility to CAR T cells at 37°C (Fig. 3H, middle) and 25°C (Fig. 3H, right).

While these results suggest that cytostatic hypothermia may function with adjuvants in vitro, its potential in vivo requires optimization and characterization, detailed in Discussion. Initial clinical trials would evaluate cytostatic hypothermia efficacy alone in recurrent and resistant GBMs (as a last resort). Thus, the in vivo potential for concomitant hypothermia could be postponed as the field matures and a patient-centric device is established.

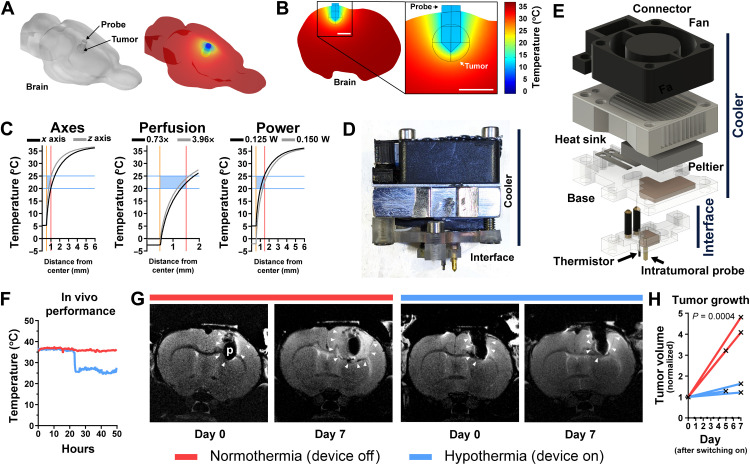

Hypothermia can be delivered in vivo and reduces GBM tumor growth

Given that hypothermia of 20° to 25°C halted cell division in vitro (Fig. 1A), we conceived a tool to deliver hypothermia in vivo to demonstrate proof of concept for cytostatic hypothermia. Using the finite-element method, we computationally modeled local intracranial hypothermia using parameters from prior studies (table S6) (30–33), Pennes’ bio-heat equations, temperature-dependent blood perfusion, and a previously modeled rat brain (34) (Fig. 4A and fig. S5A). A single 1-mm-wide gold probe was modeled invaginating into the brain with the goal of cooling a spherical volume of tissue (representing either a bulk tumor or the extent of an infiltrating tumor) via a Peltier plate (Fig. 4B and fig. S5B). Initial brain perfusion was set at 0.019333 s−1. The simulation demonstrated that a single probe creates a temperature gradient in the adjacent tissue (Fig. 4B). With the probe brought to ~12°C, the periphery of a 1-mm radius region reached 25°C (Fig. 4B) and reached >35°C within 4 mm (Fig. 4C, left). Cooling was greater across the x axis (of a coronal plane) than down the z axis (Fig. 4C, left). The extent of perfusion (ranging from 0.73 to 3.96 times brain perfusion) had a small effect on cooling even a larger 1.5-mm radius spherical region (Fig. 4C, middle). To achieve hypothermia in a 1.5-mm radius region, 125 mW of heat pulled was sufficient to attain 25°C at the periphery (Fig. 4C, right). Pulling 150 mW brought the probe to below 0°C, but the tissue was at 15°C within 0.5 mm from the probe (Fig. 4C, right). A time-dependent study using the models suggested that pulling 100 to 125 mW can bring the maximum tumor temperature to its target within 1 to 2 min (fig. S5C).

Fig. 4. Finite-element analysis and device testing for cytostatic hypothermia delivery.

(A) Left: 3D model of rat brain with a probe and subcortical spherical tumor. Right: Finite-element simulation of temperature on the brain surface. (B) Slice and magnified inset from finite-element model of rat brain with local hypothermia. (C) Finite-element analysis of hypothermia varying parameters. Center of tumor and probe lie at x = 0. Gold bar indicates surface of gold cooling probe. Red bar indicates surface of tumor. Blue bars and box show cytostatic range of temperature. Left: Extent of cooling of a 1-mm radius tumor from the nearest probe surface in the x axis (black) versus z axis (gray) of a coronal plane. Middle: Varying tumor (1.5-mm radius) perfusion relative to brain perfusion (0.73×, black to 3.96×, gray). Right: Varying heat energy withdrawal on cooling a 1.5-mm radius tumor. (D) Image of thermoelectric cooling device with lower Interface for tissue contact and an upper, removable Cooler. (E) Exploded 3D render of thermoelectric device. (F) In vivo temperature measurement from the thermistor of the Interface, 1.5 mm from the probe. (G) Representative T2-weighted MR images of F98 tumor growth on days 0 and 7 in the brains of Fischer rats. Red bar indicates that device was off (normothermia) between images, and blue bar indicates that device was on (hypothermia). White arrowheads indicate tumor boundaries. p, probe. (H) F98 tumor volume measured via MRI and normalized to day 0 (n = 3). Each line represents one rat. Mixed-effects analysis was conducted to compare the groups.

Next, to test cooling in vivo, we constructed an experimental device that consists of a removable “Cooler” and an implantable “Interface” (Fig. 4D and fig. S6). The Cooler uses an electrically powered thermoelectric (Peltier) plate secured with thermal paste between a copper plate (embedded in a polycarbonate base) and an aluminum heat sink (Fig. 4E). A fan, attached above, enhances convective heat transfer. The Interface attaches to the skull and has an intratumoral gold needle soldered to a second copper element and a thermistor wired to insulated brass screws (fig. S6, H and I). The copper parts make contact to transfer heat from the Interface to the Cooler (fig. S6L). This Cooler is powered through an external power supply. Temperature is measured by the thermistor attached to the Interface, with its wires connected to brass screws on the Implant and steel shims on the base and connected to an external voltage-divider circuit, Arduino, and a computer (fig. S7).

All rats were inoculated with F98 tumor cells, and tumor take was confirmed via T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 1 week after. The following day, the Interface with a gold probe was implanted (demonstrated in fig. S8, A and B). While mechanical forces from the intratumoral probe could influence tumor growth, this was always controlled for by using the same probe geometry in treatment and control animals (35). The Cooler was attached next. The rats were placed in and attached to a custom cage setup to enable free movement (fig. S8, C to E) (36). Once switched on, the device was able to bring tissue 1.5 mm from the surface of the probe to 25°C (Fig. 4F). Devices did not consistently reach 20°C due to inefficiencies of the heat-exchange mechanism. Interfaces embedded with an MRI-compatible thermistor enabled F98 tumor growth assessment via MRI under normothermia (device off) and hypothermia (device on) (Fig. 4G). MRI image analysis revealed a significant difference in tumor volume growth at 1 week under hypothermia versus tumors at normothermia (Fig. 4H). Because of high failure rates of the MRI-compatible thermistor, subsequent studies used an MRI-incompatible thermistor with tighter tolerance and greater reliability. These preliminary studies demonstrated that in vivo local cytostatic hypothermia was both possible and plausibly effective.

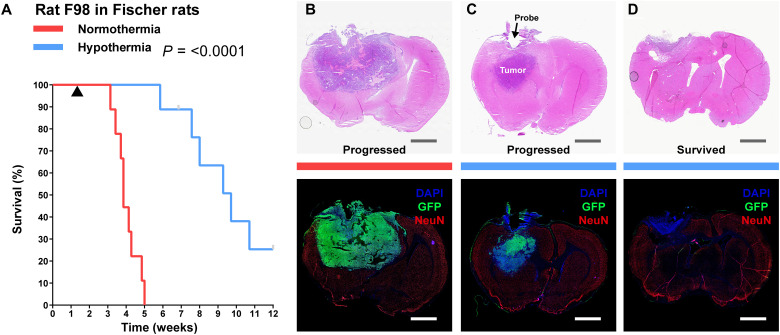

Cytostatic hypothermia extends survival of rodents with GBM in two models

As local hypothermia reduced in vivo tumor growth rate in preliminary imaging studies, we investigated its effect on animal survival. In a model with the aggressive F98 line in Fischer rats, we investigated whether survival would increase despite being unable to reach cytostatic temperature for F98 (20°C). After confirmation of tumor take with green fluorescent protein–positive (GFP+) F98 cells (fig. S9A), Interface implantation (example in fig. S8B), and Cooler attachment, rats were randomly assigned to two groups. One group (n = 9) had their devices switched on to deliver hypothermia, while the other groups’ devices (n = 9) remained off. Of the rats receiving hypothermia, only two reached near or below 20°C (1.5 mm from the probe; fig. S9B), the cytostatic temperature observed for F98 cells. All rats not receiving hypothermia required euthanasia with a median time of 3.9 weeks (Fig. 5A). After a short phase of recovery from surgery, rats receiving hypothermia did not exhibit obvious signs of weakness or distress, maintained an appetite, and gained weight (movies S1 and S2 and fig. S9C). In 3 of 450+ occasions of switching the devices on (after weighing and maintenance of rats), a seizure was observed that abated by turning off the device and did not recur when hypothermia was gradually resumed over a few minutes. With successful application of hypothermia, the median survival for six (of nine) rats was extended to 9.7 weeks (Fig. 5A). The Interface of one rat dislodged prematurely at week 7, and the point was censored. The remaining two rats survived the full 12-week study period; these were also the ones in which cytostatic hypothermia was achieved (fig. S9B). Thus, the application of hypothermia significantly increased survival (P < 0.0001) compared to the normothermia group.

Fig. 5. Delivery of local cytostatic hypothermia in Fischer rats inoculated with F98 GBM.

(A) Kaplan-Meier survival plot of rats with the device switched off (red, n = 9) or switched on to deliver hypothermia (blue, n = 9). Gray bars indicate censored rats. Black triangle indicates the start of hypothermia treatment. Groups were compared with the log-rank Mantel-Cox test. Median survival was calculated for nine rats in the normothermia group and six rats in the hypothermia group. Statistics are for all rats. (B to D) Coronal brain sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; top) and immunohistochemical markers, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), GFP, and NeuN (IHC; bottom) to show extent of tumor. Gray and white scale bars, 2.5 mm. (B) Representative section from a rat in the normothermia group. (C) Representative from a rat in the hypothermia groups in which tumor progressed and rat reached euthanasia criteria. Tumor visible in the z direction from probe (D). Representative section from a rat in the hypothermia group that survived through the study period.

Histology of rats receiving normothermia demonstrated large tumors with leptomeningeal infiltration, tumor-intrinsic necrosis and apoptosis, high Ki-67 activity, and peritumoral and ipsilateral gliosis (indentified by glial fibrillary acidic protein positivity, GFAP+) (Fig. 5B, fig. S10, and tables S7 and S8). With hypothermia, all rats showed necrosis immediately around the probe, with associated inflammation consisting of CD45+ mononuclear inflammatory cells and neutrophils (fig. S10F and table S7). Non-neoplastic brain tissue, at the border of the lesions, showed no neuronal loss or parenchymal destruction: NeuN and GFAP expression were always intact (fig. S10, A to D, and table S7). GFAP demonstrated reactive perilesional gliosis with varied extents of ipsilateral gliosis and normal patterns of glial expression elsewhere in the brain. Thus, there was no evident difference in the extent of perilesional gliosis under normothermic and hypothermic conditions. The six rats receiving 25°C hypothermia had tumors adjacent to the region of hypothermia (Fig. 5C and table S7). The two rats receiving 20°C (survivors) did not demonstrate a mass (Fig. 5D). They did have a few nonproliferative (Ki-67−) GFP+ cells (fig. S9, D and E) or a rim of viable tumor (table S7).

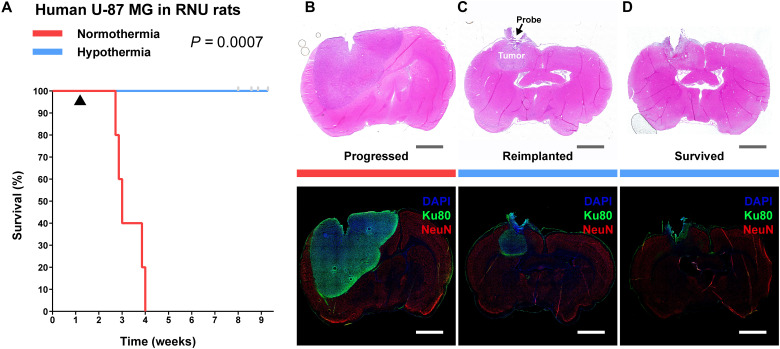

Next, we assessed cytostatic hypothermia on human U-87 MG inoculated in RNU rats. After confirmation of tumor take (fig. S11A), Interface implantation (fig. S8B), and Cooler attachment, six rats had their device switched on and five were kept off (rats were randomly assigned to each group). The devices of four treatment rats reliably delivered 25°C hypothermia (fig. S11B), the cytostatic temperature observed for U-87 MG. The thermistors of two rats failed early, and treatment of one may not have been reliably delivered (“N06”). All rats receiving normothermia required euthanasia with a median time of 3 weeks (Fig. 6A). As described previously, all rats undergoing treatment did not demonstrate signs of distress while receiving hypothermia, had a strong appetite, and gained weight (movies S1 and S2 and fig. S11C). RNU rats were more social and active than Fischer rats, and this persisted despite hypothermia. Because of this, their devices and cables required frequent maintenance and replacement with intermittent failures. Eventually, Interface implants started to break off by the seventh week, points were censored, and the study was terminated at 9 weeks (Fig. 6A). We attempted reimplantation in two rats (including N06), but this resulted in complications and days without treatment and the rats were censored. None of the rats in the hypothermia arm met euthanasia criteria within the study period (Fig. 6A), demonstrating a significant increase in survival (P = 0.0007). Histology demonstrated that rats not receiving hypothermia had large tumors with at least some tumor-intrinsic necrosis (Fig. 6B, fig. S12, and tables S7 and S8). The hypothermia rats again demonstrated necrosis with inflammatory cells immediately around the probe and intact NeuN and GFAP staining in the non-neoplastic tissue at the boundary of the lesion with brain parenchyma (fig. S12, A to D, and tables S7 and S8). In the rats receiving reimplantation (and the absence of treatment for a few days), a tumor mass and the presence of blood were visible (Fig. 6C and table S8). The remaining four hypothermia rats did not exhibit any definitive tumor away from the probe region (Fig. 6D and table S7). Together, these in vivo F98 and U-87 MG studies suggest that delivery of hypothermia, especially cytostatic hypothermia, can prolong survival.

Fig. 6. Delivery of local cytostatic hypothermia in RNU rats inoculated with human U-87 MG.

(A) Kaplan-Meier survival plot of rats with the device switched off (red, n = 5) or switched on to deliver hypothermia (blue, n = 6). Gray bars indicate censored rats. Black triangle indicates start of hypothermia. Groups were compared with the log-rank Mantel-Cox test. (B to D) Coronal brain sections stained with H&E (top) and IHC (bottom) to show extent of tumor. Gray and white scale bars, 2.5 mm. (B) Representative sections from a rat in the normothermia group. (C) Representative sections from a rat in the hypothermia groups that had poor treatment management or multiple device failures and grew a tumor in the z axis (n = 2). (D) Representative sections from a rat in the hypothermia group that did not grow a separate tumor mass (n = 4) and survived the study period.

DISCUSSION

These studies demonstrate the potential of hypothermia for preventing tumor growth. Through regimented in vitro studies, we defined a window of growth-halting temperatures, assessed their effects on cells, and explored strategic intermittent timelines to improve implementation logistics. In vitro studies also indicated that adjuvants may function with hypothermia but require extensive characterization for in vivo applicability. We computationally modeled hypothermia delivery and fabricated experimental devices to administer and monitor intracranial hypothermia, including one that was MRI compatible. In two rodent models of GBM, hypothermia extended survival while letting the animals behave normally and eat and move freely (Figs. 5 and 6 and movies S1 and S2). We suggest that the range of safe but growth-halting temperatures we term cytostatic hypothermia carries translational advantages and could one day be an option for patients.

We established cytostatic temperatures ranging from 20° to 25°C (Figs. 1B and 3D) for five glioma cell lines and observed multiple biochemical changes. Our work expands upon and validates findings, suggesting that mild hypothermia can reduce cell division (14, 23–27). This evidence is substantial, and future studies with more patient-derived lines can investigate the breadth of cytostatic degrees of temperature while simultaneously exploring mechanistic differences. In addition, we observed that intermittent hypothermia, especially after an induction dose, could be equally effective (Fig. 1C). Future studies could evaluate the mechanism of induction, but it may be a matter of cells arresting in the G2 phase (Fig. 2A) and intermittent normothermia not providing enough energy or time to complete division. With prolonged hypothermia, and cell cycle arrest, a decrease in viability was apparent, with T98G being the most sensitive (Fig. 1, D and E). Decreased viability may not be ideal as healthy cells, although more resilient to hypothermia compared to temperature-sensitive p53-mutant cells (24, 37), may die too. Potential mechanisms include Na+ or Ca2+ accumulation or increased aquaporin-4 expression (38–40) with cell swelling. To circumvent these effects, intermittent hypothermia could be equally cytostatic (Fig. 1C) but potentially less cytotoxic. Intriguingly, we discovered that F98 cells required 20°C hypothermia to halt division (Fig. 1B), and this was witnessed in its morphology (fig. S2, E and F) while it retained viability (Fig. 1D). A mechanistic cause was not elucidated, but deeper metabolomic or transcriptomic analyses (41) could help. Our brief examination of cytokine and metabolite production and consumption demonstrated reduced activity at all degrees of hypothermia as anticipated. However, as in a study of hypothermia for organ transplant preservation, accumulating ATP in most lines (Fig. 2B) also suggests that one process (e.g., consumption) can be more affected than the other (e.g., production) (42). Cytostatic hypothermia could nevertheless be an alternate approach to pharmaceutical and dietary efforts to starve tumors of resources by reducing glucose consumption and lactate production (43–45). Similarly, as glutamate is known to have a role in glioma growth (46), and inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 (Fig. 2C) are strongly associated with GBM invasiveness (47), reducing their production might be beneficial. Thus, hypothermia can be cytostatic and has broad effects on multiple cellular pathways simultaneously.

Our preliminary examination of hypothermia with TMZ chemotherapy (Fig. 3, A to C) and CAR T immunotherapy in vitro suggested that concomitant hypothermia may be a future strategy. Literature suggests that hypothermia can facilitate radiotherapy as well (48). We observed that TMZ and cytostatic hypothermia together reduced the growth of all three cell lines tested. This includes T98G cells that are typically TMZ resistant due to the enzyme MGMT (49). This synergy needs to be studied but could be due to increased hydrolysis of TMZ to its active ion, reduced MGMT expression, or compromising effects of hypothermia. T98G and LN-229, both with p53 mutations, were affected more than U-87 MG by the combination, suggesting another plausible mechanism (24, 50). On the immunotherapy front, as anticipated from whole-body hypothermia studies (51), hypothermia reduced IFN-γ production (Fig. 3F) and immune-mediated killing (Fig. 3E). However, although it took 4 days, CAR T cells still eradicated most glioma cells under cytostatic hypothermia (Fig. 3E). Intermittent hypothermia improved this efficacy (Fig. 3E), which suggests that future paradigms could apply cytostatic hypothermia between normothermic CAR T treatments. However, multiple caveats and limitations remain to be explored. The three human lines all had different responses to TMZ + hypothermia. For in vivo intervention, the effect of hypothermia on vasoconstriction and intravenous drug or cell delivery needs to be studied. Local delivery could be attempted but necessitates designing the device to enable injections. Critically, however, initial clinical trials will likely be conducted only on recurrent and resistant GBMs (after standard of care) and using only cytostatic hypothermia as a last resort. Thus, the in vivo potential for concomitant hypothermia would be relevant once the field matures, therapeutic and biological mechanisms are better understood, and a patient-centric device is established.

Fortunately, the literature and our studies present ample evidence to suggest that cytostatic hypothermia alone is safe in the brain. Intracerebral cryoprobes and cortical cooling devices in primates and patients have been safe to use (14, 16, 19, 21, 22). As we found intact neurons and glia at 20° to 25°C, another study locally cooling feline cortex down to 3°C, 2 hours/day, for 10 months demonstrated neuronal preservation and minimal histological changes (18). Cooling the feline visual cortex intermittently for >3 years also demonstrated this, but also found that visual evoked potentials were fully intact above 24°C and absent only below 20°C (19). Fortuitously, our data demonstrated that all GBM lines halted at 20°C or above. Computational modeling also demonstrated that brain perfusion kept cooling diffuse but relatively local to the region of interest (Fig. 3C), which is also seen in the literature (52). A minor reduction in neuronal activity could also have therapeutic advantages, given the recent discovery that inhibiting neuro-glial electrical conduction reduces glioma growth (53, 54). On the behavioral level, we observed that rats generally performed “normally”: They responded to stimuli, ate food, gained weight, and moved freely (movies S1 and S2). In addition, while hypothermia treatment exhibited tumor necrosis with leukocytic inflammation in the immediate region of the probe, there was no evident parenchymal damage to the adjacent brain. Even at the boundary of the lesion, no overt neuronal or glial loss was detected on immunostaining for NeuN and GFAP, respectively (fig. S10, A to D, and table S7). This provides in vivo evidence to support an in vitro study, suggesting that hypothermia can selectively protect non-neoplastic cells (24). There was no evidence of infarction, infection, or herniation, and reactive gliosis was limited to the ipsilateral hemisphere with no difference between treatment and controls (table S8). However, adverse effects of hypothermia are still possible from reduced neural firing and cellular swelling; these may be resolved by gradual temperature adjustments, intermittent hypothermia, administering molecular inhibitors (38–40), and plausibly the use of adjuvants to reduce the total length of therapy. The extent of safety and behavioral analysis with long-term treatment applied to functional cortex remains to be studied. Such studies could investigate subtle abnormalities and assess any plasticity-induced recovery over time (55). As demonstrated in the literature and our in vivo studies, compared to the adverse effects of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, cytostatic hypothermia may be relatively benign.

Perhaps the most exciting finding from this work is that an approach based on a physical phenomenon extended the survival of rodents bearing GBM. In these proof-of-concept studies, hypothermia was delivered to bring the periphery of a bulk tumor (U-87 MG) and one with leptomeningeal infiltration (56) (F98) to a cytostatic temperature. Promisingly, all rats with tumors that were treated at their cytostatic hypothermia (20°C for F98 and 25°C for U-87 MG) entirely survived the study period. Rats that demonstrated tumor growth due to insufficient treatment showed this growth deep to the probe tip (Figs. 4C and 5C). This corroborates our computational analyses, suggesting that cooling was less effective in the z axis (Fig. 4C). Fortunately, this problem can be resolved with improved device engineering and is not a biological limitation. Future studies could assess additional patient-derived xenograft models; however, our studies and the literature suggest that our observed effects may not be very cell specific. Ultimately, cytostatic hypothermia leverages fundamental physics that influences biology broadly. Thus, the effects observed in rats hold better translational promise in larger species (e.g., pigs and humans) compared to conventional species-specific targeted and molecular therapies.

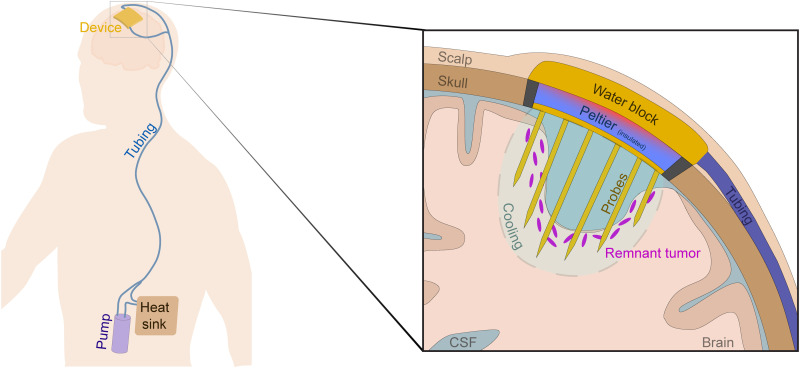

A remaining translational task is the development of a patient-centric cytostatic hypothermia device, iterations of which our team has begun designing and patented (57). Permanent neural implants have been clinically available for multiple neurological disorders for years (58). Simultaneously, an FDA-approved device for GBM now exists (worn on the scalp, powered by a backpack battery, and applies tumor-treating fields) (8). This is despite its mild benefit on survival in patients (8) and in rats (5.8 ± 2.7 weeks median and 10% total survival) (59). To induce hypothermia, heat must be transported out of the tissue. In the mid-20th century, this was attempted through a cryoprobe tethered to an external refrigerator (14). Today, variations of this approach exist, some of which use Peltier plates (19, 21, 52, 60–62). However, current approaches use percutaneous and external device components for heat removal; these increase infection susceptibility (in patients that may be immunocompromised). Similarly, to prove the concept of cytostatic hypothermia in our rodent studies, our tool used an external heat sink and fan. However, a patient-centric device would need to be fully implantable; one such iteration incorporates a more efficient fluid-based method of heat transfer while leveraging skin as a large heat sink (Fig. 7). To enable MRI compatibility for regular tumor monitoring, a piezoelectric or electromagnetic pump would move the fluid. Alternatively, perhaps biocompatible heat exchangers could be used in the future (63). At the intracranial Interface, the rodent studies used a single probe; this was effective, but per the computational analyses (Fig. 4B), it created a temperature gradient. At a larger scale, this gradient could steepen to the point of tissue ablation around the probe. Instead, a multiprobe strategy may deliver cytostatic hypothermia homogeneously in a larger volume of tissue with minimal tissue displacement (Fig. 7, inset). However, these designs require computational studies with robust validation. Implantation and design strategies must also consider the bed and potential cerebrospinal fluid cavity after surgical tumor resection. Once a device is implanted, numerous treatment strategies could be explored including lifelong, concomitant, or intermittent hypothermia [as tumors grow more slowly in vivo (64), a therapeutic device may need less than 18 hours/day; Fig. 1C]. While the tool we engineered can demonstrate the potential of cytostatic hypothermia, developing a patient-centric device may not be too far.

Fig. 7. Conceptual model of a translational device to deliver cytostatic hypothermia for GBM.

Representative diagram of a patient with GBM implanted with an envisioned cytostatic hypothermia system with zoomed inset of device (right). The envisioned system consists of an intracranial device consisting of a multiprobe array in conjunction with a cooling Peltier plate and a water block. An implanted, nonlocal, nonmagnetic pump facilitates water flow through tunneled, subcutaneous tubing to carry heat away from the hot side of the Peltier plate and distribute it to the surrounding skin via the tubing and a subcutaneous heat sink. Inset shows a slice of the cranial cavity after tumor resection with a hypothetical cytostatic hypothermia device and the remaining nonresectable tumor cells. A multiprobe array is envisioned to facilitate homogeneous cooling at the site of possible tumor recurrence.

Through these studies, we have provided evidence for the utility of cytostatic hypothermia to slow GBM growth and have demonstrated proof of concept in vivo. The data, indicating that it affects multiple cellular pathways simultaneously and slows cell division, suggest that the opportunities for tumor evolution could be reduced and the likelihood of translating to larger species is more likely. In addition, our preliminary computational and in vivo studies, in conjunction with our designs and the field of neural interfaces, make a patient-centric device within reach. As for the biology of cytostatic hypothermia, the field is open with multiple questions and mechanisms that can justify further studies [including those of noncerebral organs (23–27)]. Cytostatic hypothermia thus represents a novel approach to cancer therapy and that could serve as an addition to the few options patients with GBM currently have.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

All cell lines (U-87 MG, T98G, LN-229, F98, and CT2A) were purchased from either the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) or the Cell Culture Facility at Duke. To simplify culturing and passaging, all cells were progressively adapted to a unified medium: Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Corning, 10-013-CV) + Non-essential Amino Acids (NEAA; Gibco) + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gemini Bio). For metabolite assays, DMEM (Corning, 17-207-CV) was supplemented with 5 mM glucose (Gibco), 2 mM glutamine (Gibco), 1 mM Na+ pyruvate (Gibco), and 10% dialyzed FBS (Gemini Bio, 100-108). These media might affect growth rates for individual lines, and thus, future studies may scrutinize growth under different medium formulations under cytostatic hypothermia. Cell lines were passaged twice after thawing for recovery and then used within five passages for all experiments. To dislodge cells, 0.05% trypsin (Corning, 25-052) was used for U-87 MG and F98, while 0.25% trypsin (Corning, 25-053) was used for LN-229 and T98G. Cells were counted using an automated cell counter (Countess II, Invitrogen) calibrated to manual cell counts for each cell line. Cells were plated at a density ranging from 1000 to 20,000 cells per well in clear-bottom 96-well plates (Falcon, 353219) depending on the desired confluence at the start of the assay. Plated cells were always incubated overnight at 37°C to ensure adherence before any experiment. A HeraCell CO2 incubator was used for all experiments at 5% CO2 and set at 37°, 30°, 25°, or 20°C. The medium was carefully replaced every 2 to 4 days. To prevent losing cells from plates, multichannel pipettes were used to suction the medium instead of a vacuum.

Imaging and analysis

Imaging was performed on a live-cell microscope (DMi8, Leica Microsystems) with a built-in incubator and CO2 regulator. Well plate dimensions were added to the microscope software (LASX) to enable tile scanning. Images were taken at 5× with a 2 × 2 field with 25% overlap in 96-well plates. For lengthy imaging periods (>10 min per plate), the incubator and CO2 regulator were used. For analysis, images were merged without stitching as low cell counts prevented accurate automatic stitching. Images were then analyzed through a custom automated ImageJ script to quantify the area coverage of a well plate. To obtain cell morphology (circularity and average size), the script was modified to analyze single cells. For fluorescent live/dead cell detection, an EarlyTox Live/Dead Assay kit was used (Molecular Devices) and the microplate was imaged with a laser and GFP and TXR filters. For immunotherapy experiments, images were taken at 10× with a 4 × 4 field and a laser through a GFP filter. The ImageJ script was modified to count the number of GFP+ cells. All analyzed images were then processed through custom Python scripts to organize the data for analysis.

Molecular assays

Cell cycle analyses were conducted with a Propidium Iodide Flow Cytometry kit (ab139418, Abcam). Samples were run on a flow cytometer (Novocyte 2060, ACEA Biosciences). Data were analyzed on FlowJo v10.7.

Intracellular ATP was detected from homogenized cells via a Luminescent ATP Detection Assay kit (ab113849, Abcam). Luminescence was detected in a microplate reader (SpectraMax i3x, Molecular Devices).

Metabolites were detected from the medium through luminescence-based assays. Cells were grown in four plates with the modified medium at 37°C overnight, and then the medium was replaced. All plates were then left for 3 days at 37°C, after which the medium was collected and stored at −80°C from one plate and replaced in the others. Three plates were then moved to 30°, 25°, or 20°C. The medium was collected, stored at −80°C, and replaced every 3 days. Images were taken in a live-cell microscope before collecting the medium. Glucose consumption (Glucose-Glo, J6021, Promega), lactate production (Lactate-Glo, J5021, Promega), glutamine consumption (Glutamine/Glutamate-Glo, J8021, Promega), and glutamate production (Glutamate-Glo, J7021, Promega) were assayed from diluted samples. Luminescence was detected in the microplate reader and calibrated to a standard curve of each metabolite. Data were normalized to well coverage area quantified from images and a custom ImageJ macro.

For cytokine analysis, cells were seeded in 24-well plates at different densities for the 37° and 25°C plates to reach similar confluence at the time of the assay. All plates were incubated overnight at 37°C and then incubated for 3 days at their respective temperature. The medium was then collected and stored at −80°C from one plate. The medium in the remaining plates were replaced, and the plates were moved to 25°C. The medium was then collected, stored, and replaced every 3 to 4 days. Cytokines were detected from medium samples with a custom multiplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (LEGENDplex, BioLegend) and our flow cytometer (Novocyte 2060).

Adjuvant studies

Chemotherapy

TMZ (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in DMSO at 20 mg/ml and stored at −20°C in aliquots. Aliquots were used within 2 months. For these assays, cell lines were grown in the microplate overnight and then either kept at 37°C or moved to 25°C. TMZ at one of three doses (0, 500, or 1000 μM) was added to the 37°C plate and incubated for 4 days. The 0 μM TMZ dose consists of DMSO at an equivalent concentration to that in the 1000 μM TMZ group. The 25°C plate was first incubated for 2 days at 25°C (cytostatic for the three lines), then TMZ was added at one of the three doses, and the plate was then further incubated at 25°C for 4 days. After 4 days of TMZ treatment, the medium was completely replaced in both plates, and the plates were moved back to 37°C with daily imaging in a live-cell microscope. The line graphs of Fig. 3 (A to C) are overlaid to be able to easily compare TMZ treatment at 37°C versus TMZ treatment at 25°C.

Immunotherapy

Briefly, using a previously described protocol (65), CAR T cells were generated by harvesting splenocytes from mice and transducing them with a retrovirus that induces CAR T expression specifically targeting EGFRvIII on CT2A tumor cells. CAR T cells were stored in liquid nitrogen 4 days after transduction. All experiments used CAR T cells 5 to 7 days after transduction. For immune killing assays, 2000 EGFRvIII+ GFP+ CT2A cells were grown per well overnight in modified DMEM as described previously. In pretreatment studies, these plates were incubated for 4 or 7 days at 25°C. For experiments, different dosages of CAR T cells were added the following day with phenol red–free RPMI medium, and microplates were incubated at either 37° or 25°C. Microplates were imaged at regular intervals as described previously. The number of GFP+ cells was quantified through an ImageJ macro.

Device fabrication

Device design and manufacturing were done in collaboration with the Pratt Bio-Medical Machine Shop at Duke University. Designs were developed on MasterCam and Fusion360 (fig. S6). Most materials and parts were obtained through McMaster or vendors such as Digi-Key, Newark Element, Mouser, or Amazon. All components and manufacturing/fabrication methods are described in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Caging and treatment setup

To enable the free movement of awake rats under treatment, a custom caging and treatment setup was developed.

Cage and lever arm

Rat housing was constructed by flipping 22-quart plastic containers (Cambro), which were made hollow by sawing off the closed end. They were then sealed onto 1/4″ × 15″ × 15″ acrylic sheets (TAP Plastics) with cement for plastic (7515A11, McMaster). Parts were 3D-printed to hold a water bottle and a lever arm. The two-axis lever arm consisted of 3D-printed parts holding 1/4″ steel rods (McMaster) and a custom-made counterweight.

Electrical/treatment

Patch cables were made with male connectors (GHR-06V-S, JST Sales America) on either end of 12″ jumper cables (AGHGH28K305, JST Sales America). These were protected by a spring (9665K84, McMaster), and the joints were strengthened with epoxy and hot glue. A slipring (736, Adafruit Industries), to enable free rotation, had a female connector soldered and epoxied to an end hovering inside the cage. The patch cable connected the slipring to the Cooler.

Outside the cage, a variable voltage power supply (HM305, Hanmatek) was connected to the slipring with alligator clips. Each one powered the Peltier plate in one Cooler. USB 5V adapter towers (Amazon) were used to power the fans of multiple Coolers and connected with a USB jack on one end and alligator clips to the slipring on the other. Arduinos (Uno Rev 3, Arduino) connected to a laptop (through USB adapter towers) were connected to sliprings through a voltage-divider circuit on a breadboard and alligator clips. One Arduino was used per device for temperature monitoring.

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Duke Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Fischer (CDF) and nude (RNU) rats were purchased from Charles River at 7 to 9 weeks of age. All procedures began at 8 to 10 weeks of age. Tumor inoculation, device implantation, Cooler attachment, monitoring and maintenance, and euthanasia are described in detail in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Magnetic resonance imaging

All MRI was performed in the Center for In Vivo Microscopy (CIVM) at Duke University. For images after implantation, the Cooler was unscrewed and removed from the Interface under anesthesia. Rats were positioned on a custom 3D-printed bed, and eye gel and ear covers were applied. The rats were imaged in a Bruker BioSpin 7T MRI machine (Bruker, Billerica, MA) with a four-element rat brain surface coil. T1-weighted FLASH (TE/TR = 4.5/900 ms; flip angle = 30°; three averages) and T2-weighted TurboRARE (TE/TR = 45/8000 ms; RARE factor of 8; two to three averages) axial images were acquired at a resolution of 100-μm in-plane and slice thickness of 500 μm. During all protocols, breathing was monitored via telemetry. Animal body temperature was maintained with warm air circulation in the bore of the magnet. Upon completion, if an Interface was present, the Cooler was reattached with thermal paste applied between the copper contacts. T2-weighted images were analyzed on 3D Slicer v4.10.2 (www.slicer.org) with assistance of animal imaging experts at the CIVM for tumor take confirmation and volume quantification. Volume analysis was conducted by manually tracing tumor boundaries on each MR slice, and volume was computed by the software.

Histology

Brains were cryo-sectioned into 12-μm slices and collected on Superfrost+ slides, and the slides were stored at −20°C. Some slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and imaged under our microscope with a color filter. Other slides were stained with immunohistochemistry (IHC) markers (from Abcam) and imaged under our microscope with fluorescent lasers. These included mouse anti-GFP (ab1218), mouse anti-human Ku80 (ab119935), rabbit anti-rat NeuN (ab177487), chicken anti-rat GFAP (ab4674), rabbit anti-rat CD45 (ab10558), rabbit anti–Ki-67 (ab16667), and rabbit anti-rat/human cleaved caspase-3 (ab49822). Secondary antibodies included goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (ab150113), goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (ab150080), and goat anti-chicken Cy5.5 (ab97148). Briefly, slides were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 0.5% Triton X-100, blocked with 4% goat serum for 2 hours, followed by staining with primary antibodies diluted in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), overnight at 4°C. Secondary-only controls did not receive any primary antibody. The next day, slides were washed with PBS, stained with secondary antibodies diluted in 1% BSA for 2 hours, counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 15 min, washed and coverslipped with Fluoromount G (Southern Biotech), and left to dry overnight at room temperature. The subsequent day, nail polish was applied to the edges of the slides and then they were stored in boxes at room temperature.

Histological images were acquired by either a color camera (for H&E) or a fluorescence camera (for IHC) attached to the DMi8 microscope previously described. Whole-section tile-scanned images were taken at 10× zoom with 25% overlap and automatically stitched. Care was taken to ensure that imaging for any stain group was conducted in a single sitting. Images were then processed via a custom ImageJ script to create composites with suppressed background signal. The final images and H&E slides were then independently analyzed by an expert neuropathologist who was blinded to the experimental conditions.

Computational modeling

Modeling was performed on COMSOL v5.2 to study heat transfer between the probe and surrounding tissue via the finite element method. Both the steady-state temperature and transient effects of initiating and stopping cooling were studied. The geometry of the model consisted of a rat brain model containing a spherical volume of tissue (which could be interpreted as both a bulk tumor or the extent of a small, infiltrating tumor) and gold probe. The rat brain model, acquired from the literature (34), was generated from MRI data and smoothened to reduce anatomical indentations. The probe was modeled as a cylinder with a diameter of 1 mm and height of 2.5 mm with a 45° chamfer at the tip. The tip of the probe was embedded in the tumor that was modeled as a sphere with diameters of 2 and 3 mm. Heat transfer was modeled with the Pennes’ bioheat equation. A negative heat flux was applied to the top face of the probe to cool the probe. All other outer surfaces were fully insulated with zero heat flux.

All tissues and materials used in the model were assumed to be homogeneous and isotropic—features such as brain blood vessels were not modeled. Multiple parameters used for the tissues, perfusion, and materials were investigated (table S6). Original perfusion values in units of ml/100 g/min were converted into s−1 using a blood density of 1050 kg/m3.

The blood perfusion and metabolic heat generation parameters were temperature dependent based on the following equations

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed on GraphPad Prism v9.0.2. Error is expressed as SD. Where appropriate, one-way, repeated-measures, and two-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons post hoc test unless otherwise specified. Survival was analyzed with the log-rank Mantel-Cox test. Significance was set to 0.05 for all studies.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to N. Mehta and S. Carroll for providing CAR T cells, the CIVM at Duke University for MRI, the staff (K. Lynn, B. Pickle, J. DeGraff, and F. Orozco) and veterinarians (F. Smith and C. Rouse) at the Duke Vivarium for assistance in setting up and maintaining animal experiments, E. Mallon for advice on setting up a temperature recording system, and S. Ather Enam for neurosurgical insights.

Funding: The authors acknowledge that they received no funding in support of this research.

Author contributions: S.F.E. conceived the project. S.F.E., C.Y.K., J.H., C.S.T., and E.I. conducted the in vitro studies and data analysis. S.F.E., B.J.K., and M.I.B. conducted the in vivo studies and histology. R.C. and S.F.E. conducted the computational studies. S.J.B. conducted MRI and analysis. A.F.B. and S.F.E. conducted histological analysis. S.F.E. and S.J.O. designed and fabricated the devices. S.F.E. wrote the manuscript. All authors edited and reviewed the manuscript. S.F.E., J.G.L., and R.V.B. supervised the studies. R.V.B. funded all the studies.

Competing interests: S.F.E., S.J.O., R.C., and R.V.B. are inventors on a patent related to this work filed by Duke University (no. WO2021076962A1, filed on 16 October 2020, published on 22 April 2021) and pending patent filed by Duke University (no. 17/769,985, filed on 18 April 2022). The authors declare no other competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S12

Tables S1 to S8

Other Supplementary Material for this : manuscript includes the following:

Movies S1 and S2

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.M. Koshy, J. L. Villano, T. A. Dolecek, A. Howard, U. Mahmood, S. J. Chmura, R. R. Weichselbaum, B. J. McCarthy,Improved survival time trends for glioblastoma using the SEER 17 population-based registries. J. Neurooncol. 107,207–212 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Q. T. Ostrom, G. Cioffi, H. Gittleman, N. Patil, K. Waite, C. Kruchko, J. S. Barnholtz-Sloan,CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2012–2016. Neuro Oncol. 21,v1–v100 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.M. Rapp, J. Baernreuther, B. Turowski, H. J. Steiger, M. Sabel, M. A. Kamp,Recurrence pattern analysis of primary glioblastoma. World Neurosurg. 103,733–740 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.J. P. Kirkpatrick, N. N. Laack, H. A. Shih, V. Gondi,Management of GBM: A problem of local recurrence. Neurooncol. 134,487–493 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.A. A. Brandes, A. Tosoni, E. Franceschi, G. Sotti, G. Frezza, P. Amistà, L. Morandi, F. Spagnolli, M. Ermani,Recurrence pattern after temozolomide concomitant with and adjuvant to radiotherapy in newly diagnosed patients with glioblastoma: Correlation with MGMT promoter methylation status. J. Clin. Oncol. 27,1275–1279 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.M. Weller, M. van den Bent, J. C. Tonn, R. Stupp, M. Preusser, E. Cohen-Jonathan-Moyal, R. Henriksson, E. Le Rhun, C. Balana, O. Chinot, M. Bendszus, J. C. Reijneveld, F. Dhermain, P. French, C. Marosi, C. Watts, I. Oberg, G. Pilkington, B. G. Baumert, M. J. B. Taphoorn, M. Hegi, M. Westphal, G. Reifenberger, R. Soffietti, W. Wick; European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) Task Force on Gliomas ,European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of adult astrocytic and oligodendroglial gliomas. Lancet Oncol. 18,e315–e329 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D. Gramatzki, P. Roth, E. J. Rushing, J. Weller, N. Andratschke, S. Hofer, D. Korol, L. Regli, A. Pangalu, M. Pless, J. Oberle, R. Bernays, H. Moch, S. Rohrmann, M. Weller,Bevacizumab may improve quality of life, but not overall survival in glioblastoma: An epidemiological study. Ann. Oncol. 29,1431–1436 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.S. Kesari, Z. Ram; EF-14 Trial Investigators ,Tumor-treating fields plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for glioblastoma at first recurrence: A post hoc analysis of the EF-14 trial. CNS Oncol. 6,185–193 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.A. Jain, M. Betancur, G. D. Patel, C. M. Valmikinathan, V. J. Mukhatyar, A. Vakharia, S. B. Pai, B. Brahma, T. J. MacDonald, R. V. Bellamkonda,Guiding intracortical brain tumour cells to an extracortical cytotoxic hydrogel using aligned polymeric nanofibres. Nat. Mater. 13,308–316 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.J. G. Lyon, S. L. Carroll, N. Mokarram, R. V. Bellamkonda,Electrotaxis of glioblastoma and medulloblastoma spheroidal aggregates. Sci. Rep. 9,5309 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.F. K. Storm, D. L. Morton,Localized hyperthermia in the treatment of cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 33,44–56 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.I. S. Cooper, S. Stellar,Cryogenic freezing of brain tumors for excision or destruction in situ. J. Neurosurg. 20,921–930 (1963). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A. A. Gage, J. M. Baust, J. G. Baust,Experimental cryosurgery investigations in vivo. Cryobiology 59,229–243 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.T. Fay,Early experiences with local and generalized refrigeration of the human brain. J. Neurourg. 16,239–260 (1959). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.M. A. Bohl, N. L. Martirosyan, Z. W. Killeen, E. Belykh, J. M. Zabramski, R. F. Spetzler, M. C. Preul,The history of therapeutic hypothermia and its use in neurosurgery. J. Neurosurg. 130,1006–1020 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.G. F. Rowbotham, A. L. Haigh, W. G. Leslie,Cooling cannula for use in the treatment of cerebral neoplasms. Lancet 273,12–15 (1959). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D. Wion,Therapeutic dormancy to delay postsurgical glioma recurrence: The past, present and promise of focal hypothermia. J. Neurooncol. 133,447–454 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.X.-F. Yang, B. R. Kennedy, S. G. Lomber, R. E. Schmidt, S. M. Rothman,Cooling produces minimal neuropathology in neocortex and hippocampus. Neurobiol. Dis. 23,637–643 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.S. G. Lomber, B. R. Payne, J. A. Horel,The cryoloop: An adaptable reversible cooling deactivation method for behavioral or electrophysiological assessment of neural function. J. Neurosci. Methods 86,179–194 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.H. A. Choi, N. Badjatia, S. A. Mayer,Hypothermia for acute brain injury—Mechanisms and practical aspects. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 8,214–222 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.M. D. Smyth, S. M. Rothman,Focal cooling devices for the surgical treatment of epilepsy. Neurosurg Clin. N. Am. 22,533–546 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.K. M. Karkar, P. A. Garcia, L. M. Bateman, M. D. Smyth, N. M. Barbaro, M. Berger,Focal cooling suppresses spontaneous epileptiform activity without changing the cortical motor threshold. Epilepsia 43,932–935 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D. Kalamida, I. V. Karagounis, A. Mitrakas, S. Kalamida, A. Giatromanolaki, M. I. Koukourakis, O. Gires,Fever-range hyperthermia vs. hypothermia effect on cancer cell viability, proliferation and HSP90 expression. PLOS ONE 10,e0116021 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Z. Matijasevic,Selective protection of non-cancer cells by hypothermia. Anticancer Res. 22,3267–3272 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.C. Fulbert, C. Gaude, E. Sulpice, S. Chabardès, D. Ratel,Moderate hypothermia inhibits both proliferation and migration of human glioblastoma cells. J. Neurooncol. 144,489–499 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.X. Zhang, Y. G. Lv, G. B. Chen, Y. Zou, C. W. Lin, L. Yang, P. Guo, M. P. Lin,Effect of mild hypothermia on breast cancer cells adhesion and migration. Biosci. Trends 6,313–324 (2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D. K. Kelleher, C. Nauth, O. Thews, W. Krueger, P. Vaupel,Localized hypothermia: Impact on oxygenation, microregional perfusion, metabolic and bioenergetic status of subcutaneous rat tumours. Br. J. Cancer 78,56–61 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.C. Fulbert, S. Chabardès, D. Ratel,Adjuvant therapeutic potential of moderate hypothermia for glioblastoma. J. Neurooncol. 152,467–482 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.L. Maggs, G. Cattaneo, A. E. Dal, A. S. Moghaddam, S. Ferrone,CAR T cell-based immunotherapy for the treatment of glioblastoma. Front. Neurosci. 15,662064 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.P. Hasgall, F. Di Gennaro, C. Baumgartner, E. Neufeld, B. Lloyd, M. Gosselin, D. Payne, A. Klingenböck, N. Kuster, IT’IS Database for thermal and electromagnetic parameters of biological tissues (2018); doi: 10.13099/VIP21000-04-0. [DOI]

- 31.J. R. Larkin, M. A. Simard, A. A. Khrapitchev, J. A. Meakin, T. W. Okell, M. Craig, K. J. Ray, P. Jezzard, M. A. Chappell, N. R. Sibson,Quantitative blood flow measurement in rat brain with multiphase arterial spin labelling magnetic resonance imaging. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 39,1557–1569 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.J. L. Boxerman, K. M. Schmainda, R. M. Weisskoff,Relative cerebral blood volume maps corrected for contrast agent extravasation significantly correlate with glioma tumor grade, whereas uncorrected maps do not. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 27,859–867 (2006). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Y. Wang, L. Zhu, A. J. Rosengart,Targeted brain hypothermia induced by an interstitial cooling device in the rat neck: Experimental study and model validation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 51,5662–5670 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 34.B. M. Pohl, F. Gasca, U. G. Hofmann, IGES and .stl file of a rat brain (2013); doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.823546.v1. [DOI]

- 35.R. K. Jain, J. D. Martin, T. Stylianopoulos,The role of mechanical forces in tumor growth and therapy. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 16,321–346 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.S. F. Enam, B. J. Kang, J. G. Lyon, R. V. Bellamkonda, DIY caging apparatus to facilitate chronic and continuous stimulation or recording in an awake rodent. bioRxiv 10.1101/2021.12.16.473031 [Preprint]. 19 December 2021. 10.1101/2021.12.16.473031. [DOI]

- 37.J. Lu, L. Chen, Z. Song, M. Das, J. Chen,Hypothermia effectively treats tumors with temperature-sensitive p53 mutations. Cancer Res. 81,3905–3915 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.N. Plesnila, E. Muller, S. Guretzki, F. Ringel, F. Staub, A. Baethmann,Effect of hypothermia on the volume of rat glial cells. J. Physiol. 523Pt 1,155–162 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.J. S. Bayley, C. B. Winther, M. K. Andersen, C. Grønkjær, O. B. Nielsen, T. H. Pedersen, J. Overgaard, Cold exposure causes cell death by depolarization-mediated Ca2+ overload in a chill-susceptible insect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115,E9737–E9744 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.M. M. Salman, P. Kitchen, M. N. Woodroofe, J. E. Brown, R. M. Bill, A. C. Conner, M. T. Conner,Hypothermia increases aquaporin 4 (AQP4) plasma membrane abundance in human primary cortical astrocytes via a calcium/transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4)- and calmodulin-mediated mechanism. Eur. J. Neurosci. 46,2542–2547 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.J. Zhang, X. Xue, Y. Xu, Y. Zhang, Z. Li, H. Wang,The transcriptome responses of cardiomyocyte exposed to hypothermia. Cryobiology 72,244–250 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.J. Ishikawa, M. Oshima, F. Iwasaki, R. Suzuki, J. Park, K. Nakao, Y. Matsuzawa-Adachi, T. Mizutsuki, A. Kobayashi, Y. Abe, E. Kobayashi, K. Tezuka, T. Tsuji,Hypothermic temperature effects on organ survival and restoration. Sci. Rep. 5,9563 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.E. C. Woolf, N. Syed, A. C. Scheck,Tumor metabolism, the ketogenic diet and β-hydroxybutyrate: Novel approaches to adjuvant brain tumor therapy. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 9,122 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.T. N. Seyfried, P. Mukherjee,Targeting energy metabolism in brain cancer: Review and hypothesis. Nutr. Metab. 2,30 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.T. N. Seyfried, M. A. Kiebish, J. Marsh, L. M. Shelton, L. C. Huysentruyt, P. Mukherjee,Metabolic management of brain cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1807,577–594 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.H. Sontheimer,A role for glutamate in growth and invasion of primary brain tumors. J. Neurochem. 105,287–295 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.V. F. Zhu, J. Yang, D. G. LeBrun, M. Li,Understanding the role of cytokines in glioblastoma multiforme pathogenesis. Cancer Lett. 316,139–150 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.A. H. Nias, P. M. Perry, A. R. Photiou,Modulating the oxygen tension in tumours by hypothermia and hyperbaric oxygen. J. R. Soc. Med. 81,633–636 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.S. Y. Lee,Temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma multiforme. Genes Dis. 3,198–210 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Z. Matijasevic, J. E. Snyder, D. B. Ludlum,Hypothermia causes a reversible, p53-mediated cell cycle arrest in cultured fibroblasts. Oncol. Res. 10,605–610 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.G. Du, Y. Liu, J. Li, W. Liu, Y. Wang, H. Li,Hypothermic microenvironment plays a key role in tumor immune subversion. Int. Immunopharmacol. 17,245–253 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.D. Aronov, M. S. Fee,Analyzing the dynamics of brain circuits with temperature: Design and implementation of a miniature thermoelectric device. J. Neurosci. Methods 197,32–47 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.H. S. Venkatesh, T. B. Johung, V. Caretti, A. Noll, Y. Tang, S. Nagaraja, E. M. Gibson, C. W. Mount, J. Polepalli, S. S. Mitra, P. J. Woo, R. C. Malenka, H. Vogel, M. Bredel, P. Mallick, M. Monje,Neuronal activity promotes glioma growth through neuroligin-3 secretion. Cell 161,803–816 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.H. S. Venkatesh, W. Morishita, A. C. Geraghty, D. Silverbush, S. M. Gillespie, M. Arzt, L. T. Tam, C. Espenel, A. Ponnuswami, L. Ni, P. J. Woo, K. R. Taylor, A. Agarwal, A. Regev, D. Brang, H. Vogel, S. Hervey-Jumper, D. E. Bergles, M. L. Suvà, R. C. Malenka, M. Monje,Electrical and synaptic integration of glioma into neural circuits. Nature 573,539–545 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.A. J. C. Kalisvaart, B. Prokop, F. Colbourne,Hypothermia: Impact on plasticity following brain injury. Brain Circ. 5,169–178 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.R. F. Barth, B. Kaur,Rat brain tumor models in experimental neuro-oncology: The C6, 9L, T9, RG2, F98, BT4C, RT-2 and CNS-1 gliomas. J. Neurooncol. 94,299–312 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.S. F. Enam, M. Calhoun, T. Saxena, S. Owen, R. Bellamkonda, R. Chen, P. Maccarini, Devices, systems, and methods for modulating tissue temperature. U.S. Patent 17/273,548 (2021).

- 58.M. R. Burns, S. Y. Chiu, B. Patel, S. G. Mitropanopoulos, J. K. Wong, A. Ramirez-Zamora,Advances and future directions of neuromodulation in neurologic disorders. Neurol. Clin. 39,71–85 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.H. Wu, C. Wang, J. Liu, D. Zhou, D. Chen, Z. Liu, A. Wu, L. Yang, J. Chang, C. Luo, W. Cheng, S. Shen, Y. Bai, X. Mu, C. Li, Z. Wang, L. Chen,Evaluation of a tumor electric field treatment system in a rat model of glioma. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 26,1168–1177 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.D. F. Cooke, A. B. Goldring, I. Yamayoshi, P. Tsourkas, G. H. Recanzone, A. Tiriac, T. Pan, S. I. Simon, L. Krubitzer,Fabrication of an inexpensive, implantable cooling device for reversible brain deactivation in animals ranging from rodents to primates. J. Neurophysiol. 107,3543–3558 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.H. Imoto, M. Fujii, J. Uchiyama, H. Fujisawa, K. Nakano, I. Kunitsugu, S. Nomura, T. Saito, M. Suzuki,Use of a Peltier chip with a newly devised local brain-cooling system for neocortical seizures in the rat. Technical note. J. Neurosurg. 104,150–156 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.H. E. Bakken, H. Kawasaki, H. Oya, J. D. W. Greenlee, M. A. Howard,A device for cooling localized regions of human cerebral cortex. J. Neurosurg. 99,604–608 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.D. C. Corbett, W. B. Fabyan, B. Grigoryan, C. E. O’Connor, F. Johansson, I. Batalov, M. C. Regier, C. A. DeForest, J. S. Miller, K. R. Stevens,Thermofluidic heat exchangers for actuation of transcription in artificial tissues. Sci. Adv. 6,eabb9062 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.S. Rockwell,In vivo-in vitro tumour cell lines: Characteristics and limitations as models for human cancer. Br. J. Cancer 41,118–122 (1980). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.K. Riccione, C. M. Suryadevara, D. Snyder, X. Cui, J. H. Sampson, L. Sanchez-Perez,Generation of CAR T cells for adoptive therapy in the context of glioblastoma standard of care. J. Vis. Exp. 96,e52397 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S12

Tables S1 to S8

Movies S1 and S2