Abstract

Background:

Surgical wound complications represent an important risk factor, particularly in multilevel lumbar fusions. However, the literature regarding optimal wound closure techniques for these procedures is limited.

Methods:

We performed an online survey of 61 spinal surgeons from 11 countries, involving 25 different hospitals. The study included 26 neurosurgeons, 21 orthopedists, and 14 residents (Neurosurgery – 6 and orthopedics 8). The survey contained 17 questions on demographic information, closure techniques, and the use of drainage in posterior lumbar fusion surgery. We then developed a “consensus technique.”

Results:

The proposed standardized closure techniques included: (1) using subfascial gravity drainage (i.e., without suction) with drain removal for <50 ml/day or a maximum duration of 48 h, (2) paraspinal muscle, fascia, and supraspinous ligament closure using interrupted-X stitches 0 or 1 Vicryl or other longer-lasting resorbable suture (i.e., polydioxanone suture), (3) closure of subcutaneous tissue with interrupted inverted Vicryl 2-0 sutures in two planes for subcutaneous tissue greater >25 mm in depth, and (4) skin closure with simple interrupted nylon 3-0 sutures.

Conclusion:

There is great variability between closure techniques utilized for multilevel posterior lumbar fusion surgery. Here, we have described various standardized/evidence-based proven techniques for the closure of these wounds.

Keywords: Midline posterior lumbar fusion, Spine surgery, Standardized closure, Wound closure

INTRODUCTION

Surgical wound complications (incidence: 0.2–20%) for patients undergoing multilevel lumbar fusion surgery represent major risk factors that increase morbidity, mortality, and hospital costs.[5,13,14] Notably, there is scant consensus regarding the optimal lumbar wound closure techniques. Here, we offer a standardized and potentially optimal summary of the key wound closure techniques that should be utilized to close multilevel lumbar fusions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted an online survey of 61 participants: 26 neurosurgeons (+6 residents), 21 orthopedists (+8 residents) from 11 countries, to 25 different hospitals [Table 1]. Our survey (i.e., in Spanish and English) contained 7 questions regarding the use of various standardized closure techniques. It included how to close multilevel lumbar fusions, what sutures to use, when drains should be placed, and for how long [Table 2]. Three orthopedists and three neurosurgeons from two hospitals in Mexico City then developed a “consensus technique” based on an analysis of the survey data.

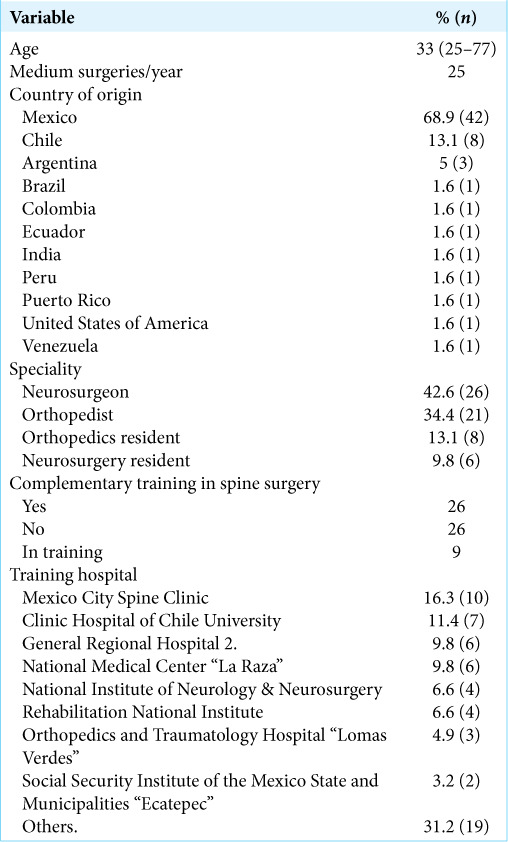

Table 1:

Demographics of participants in the survey of closure technique in spine surgery for posterior lumbar fusion.

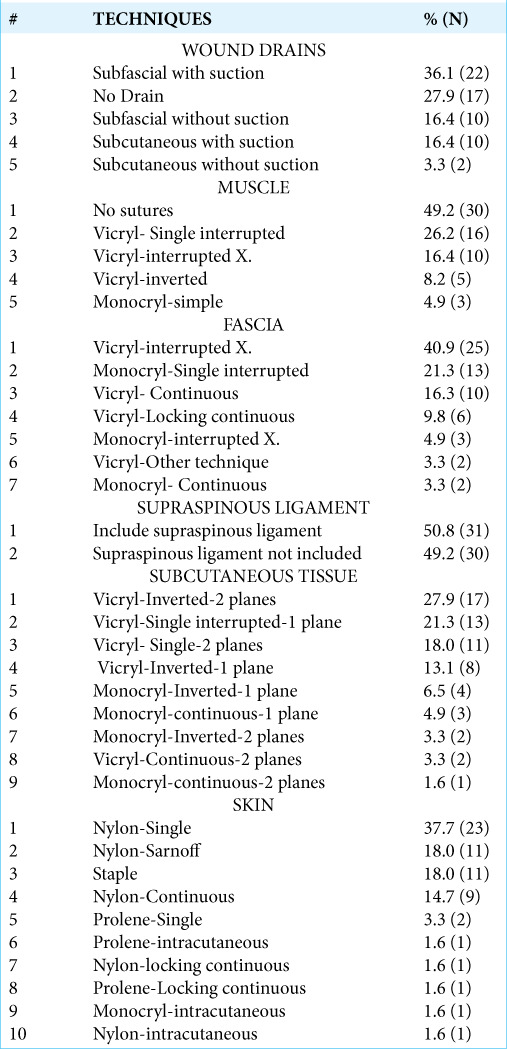

Table 2:

Results of the survey of closure technique in spine surgery for posterior lumbar fusion: variability in closure techniques in different anatomic planes.

RESULTS

Although 50.8% (31) of surgeons reported using a standardized closure method, they utilized different techniques for each of the planes of closure. In all, we encountered 61 different closure combinations for the 61 participants [Table 2].

DISCUSSION

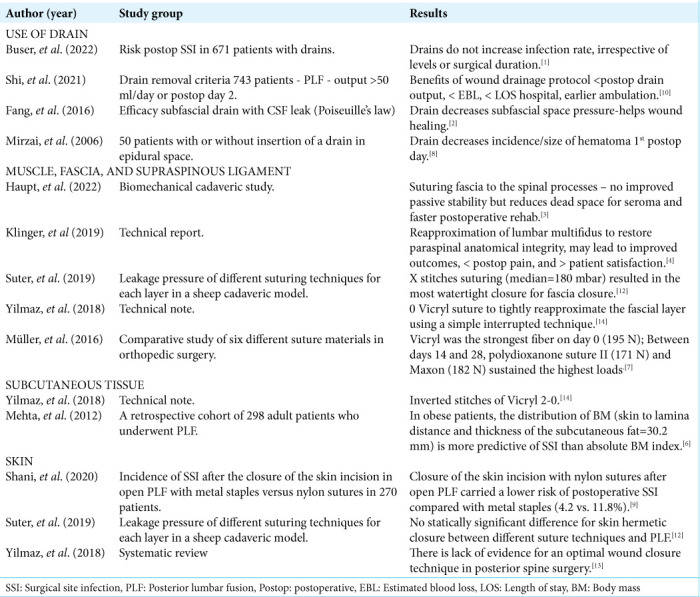

We analyzed the variability in the midline posterior closure techniques utilized by 26 neurosurgeons, 21 orthopedists, and 14 residents to perform multilevel lumbar spine fusion surgery. Different studies have individually evaluated closure techniques in multilevel lumbar fusion surgery [Table 3].

Table 3:

Review of the literature on closure techniques in different anatomic planes.

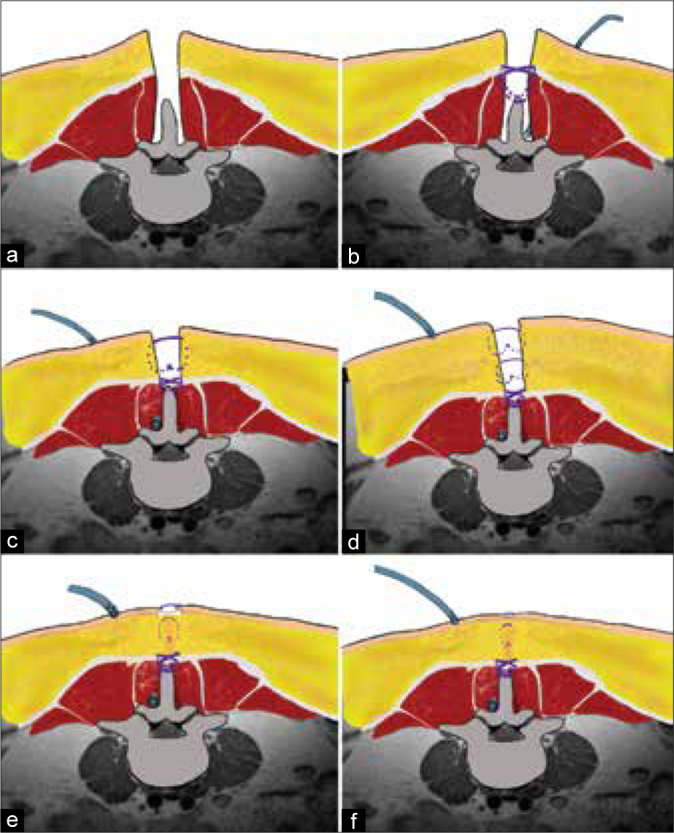

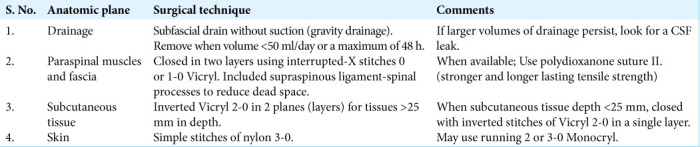

Our standardized technique first included utilizing a subfascial drain without suction (i.e., gravity drainage) with drain removal either when the volume was < 50 ml/day or when the drain has been in place a maximum of 48 h. (note: if larger volumes of drainage persist look for a cerebrospinal fluid leak).[1,2,8,10] Second, the paraspinal muscles, fascia, and supraspinal ligament should be closed in two or even three separate layers using interrupted-X stitches 0 or 1-0 Vicryl sutures.[3,4,12,14] Alternatively, one could choose to use, stronger, and longer-lasting PDS Polydioxanone sutures (PDS II:) absorbable suture maintain; 25% of tensile strength at 42 days; resorbs 130–180 days).[7] Third, closure of subcutaneous tissues should employ inverted Vicryl 2-0 in two planes for tissues >25 mm in depth.[6] Fourth, skin closure should include the use of simple nylon 3-0 sutures(i.e., others may use a running 2 or 3-0 Monocryl (i.e., 75% glycolide and 25% ε-caprolactone)[9,12,13] [Figure 1 and Table 4].

Figure 1:

(a) Midline posterior lumbar approach. (b) Using subfascial gravity drainage (i.e., without suction) with drain removal for <50 ml/day or a maximum duration of 48 h; paraspinal muscle and fascia closure with an interrupted-X technique of Vicryl 1 or other longer-lasting resorbable suture and include the supraspinous ligament. (c) Closure of subcutaneous tissue with interrupted inverted stitches of Vicryl 2-0 in 1 single plane when depth <25 mm. (d) Two planes for subcutaneous tissue greater > than 25 mm in depth. (e) Skin closure with simple interrupted nylon 3-0 sutures. (f) Standardized closure.

Table 4:

Standardized closure technique: Summary.

CONCLUSION

Process standardization enables evidence-based continual improvement by comparing different interventions on the same process.[11] There is a great variability for the closure of multilevel lumbar fusions performed utilizing a midline posterior approach.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Montes-Aguilar OJ, Alaniz-Sida KK, Alvarez-Betancourt L, Dufoo-Olvera M, Ladewig-Bernaldez G, López-López R, et al. Variability in wound closure technique in midline posterior lumbar fusion surgery. International survey and standardized closure technique proposal. Surg Neurol Int 2022;13:534.

Contributor Information

Oscar Josue Montes Aguilar, Email: oscar_16031@hotmail.com.

Karmen Karina Alaniz Sida, Email: karialanizs@gmail.com.

Leonardo Álvarez Betancourt, Email: leoalvarezb1@hotmail.com.

Manuel Dufoo Olvera, Email: mdufoo27@yahoo.com.

Guillermo Ivan Ladewig Bernaldez, Email: dr.ladewig@gmail.com.

Ramón López López, Email: dr_ramonzl@hotmail.com.

Edith Oropeza Oropeza, Email: dra.edith.oropeza@gmail.com.

Héctor Alonso Tirado Ornelas, Email: hector.alonso.7@hotmail.com.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buser Z, Chang K, Kall R, Formanek B, Arakelyan A, Pak S, et al. Lumbar surgical drains do not increase the risk of infections in patients undergoing spine surgery. Eur Spine J. 2022;31:1775–83. doi: 10.1007/s00586-022-07130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fang Z, Jia Y, Tian R, Liu Y. Subfascial drainage for management of cerebrospinal fluid leakage after posterior spine surgery-a prospective study based on Poiseuille’s law. Chin J Traumatol. 2016;19:35–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haupt S, Cornaz F, Falkowski AL, Widmer J, Farshad M. Biomechanical considerations of the posterior surgical approach to the lumbar spine. Spine J. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2022.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klinger N, Yilmaz E, Halalmeh DR, Tubbs RS, Moisi MD. Reattachment of the multifidus tendon in lumbar surgery to decrease postoperative back pain: A technical note. Cureus. 2019;11:e6366. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee N, Shin J, Kothari P, Kim J, Leven D, Steinberger J, et al. Incidence, impact, and risk factors for 30-day wound complications following elective adult spinal deformity surgery. Global Spine J. 2017;7:417–24. doi: 10.1177/2192568217699378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehta A, Babu R, Karikari I, Grunch B, Agarwal V, Owens T, et al. 2012 young investigator award winner: The distribution of body mass as a significant risk factor for lumbar spinal fusion postoperative infections. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:1652–6. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318241b186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller DA, Snedeker JG, Meyer DC. Two-month longitudinal study of mechanical properties of absorbable sutures used in orthopedic surgery. J Orthop Surg Res. 2016;11:111. doi: 10.1186/s13018-016-0451-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mirzai H, Eminoglu M, Orguc Ş. Are drains useful for lumbar disc surgery? A prospective randomized clinical study. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19:171–7. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000190560.20872.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shani A, Poliansky V, Mulla H, Rahamimov N. Nylon skin sutures carry a lower risk of post-operative infection than metal staples in open posterior spine surgery: A retrospective case-control study of 270 patients. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2020;21:440–4. doi: 10.1089/sur.2019.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi H, Huang ZH, Huang Y, Zhu L, Jiang ZL, Wang YT, et al. Which criterion for wound drain removal is better following posterior 1-level or 2-level lumbar fusion with instrumentation: Time driven or output driven? Global Spine J. 2021 doi: 10.1177/21925682211013770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skjold-Ødegaard B, Søreide K. Standardization in surgery: Friend or foe? Br J Surg. 2020;107:1094–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suter A, Spirig J, Fornaciari P, Bachmann E, Götschi T, Klein K, et al. Watertightness of wound closure in lumbar spine-a comparison of different techniques. J Spine Surg. 2019;5:358–64. doi: 10.21037/jss.2019.08.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yilmaz E, Blecher R, Moisi M, Ankush C, O’Lynnger T, Abdul-Jabbar A, et al. Is there an optimal wound closure technique for major posterior spine surgery? A systematic review. Global Spine J. 2018;8:535–44. doi: 10.1177/2192568218774323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yilmaz E, Tawfik T, O’Lynnger T, Iwanaga J, Blecher R, Abdul-Jabbar A, et al. Wound closure after posterior multilevel lumbar spine surgery: An anatomical cadaver study and technical note. Cureus. 2018;10:e3595. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]