Abstract

Ferns are used as traditional and fascinating foods in many countries. They are also considered to possess important ethnomedicinal values; however, ferns are one of the underutilized plant resources by both scientific and local communities. Pharmagonostical studies reveal that ferns and fern-allies possess several biological activities including antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, antimalarial, antidiarrheal, anthelmintic, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, anticancer, neuroprotective, nephroprotective, hepatoprotective, antifertility, etc. Flavonoids and terpenoids are major secondary metabolites present in ferns. Ugonins, particularly isolated from Helminthostachys zeylanica, have found diverse bioactivities. Ptaquiloside, a norsesquiterpene glucoside, found in Pteridium revolutum, Dryopteris cochleata and Polystichum squarrosum, is one of the hazardous metabolites of ferns which is responsible for the toxic effect. Alkaloids are reported to be present in the ferns; however, the qualitative data are uncertain. Some fern metabolites, such as cyanogenic glycosides and terpenoids, are considered to possess defensive activity against animal attacks. Some ferns are also used for manuring as biological alternative to pesticides. Nepalese have consumed at least 33 species of ferns and fern-allies belonging to 13 families, 20 genera as cooked vegetable foods. The aim of this review is compilation of information available on their distribution, ethnomecinal values, pharmcognosy, pharmacology and phytochemistry.

Keywords: Bioactivity, Biodiversity, Food, Pteridophytes, Secondary metabolite, Traditional knowledge

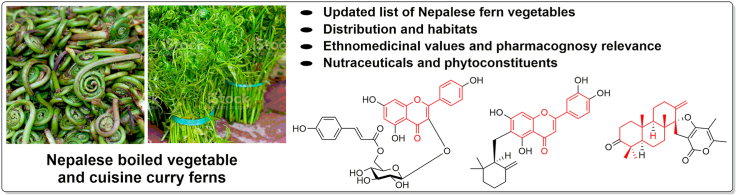

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Ferns and fern-allies are consumed as a vegetable in many countries.

-

•

Ferns possess several ethnomedicinal values, but are less explored scientifically.

-

•

Flavonoids, terpenoids and steroids are major secondary metabolites found in ferns.

-

•

This review compiles pharmcognosy and phytochemistry of 33 wild ferns eaten by Nepalese as cooked vegetable foods.

Bioactivity; Biodiversity; Food; Pteridophytes; Secondary metabolite; Traditional knowledge.

1. Introduction

Nepal is a small land-locked country resides on the lap of the great Himalaya, in the north. It is sandwitched between China and India. Despite occupying only 0.1% of the global area, the country is naturally blessed and enriched with cultural, geographical and biological diversities [1]. Its cultural diversities are interlinked with more than 60 ethnic groups speaking more than 100 languages. Geographically, it has a large altitudinal variations ranging from a low land (altitude nearly 60 m in south) to the higest peak of the earth (Mt. Everest, 8,848.86 m in north) within a span of just about 200 km of aerial expansion from south to north. Its physiographic regions comprises (1) Tarai, (2) Siwaliks and Chure, (3) Mahabharat, (4) Midlands or central hills, (5) Himalayas, and (6) Inner Himalayas and Tibetan marginal mountains [2]. The country has 118 different types of ecosystems harboring 3.2% of the world's flora including 5.1% of gymnosperms, 3.2% of angiosperms, 5.1% of pteridophytes, 8.2% of bryophytes, 2.5% of algae, 2.6% of fungi and 2.3% of lichens [1].

For food and livelihood securities, Nepalese significantly depend on cultivated and wild vegetables [3]. In Nepal, it has been estimated that >650 species are used as food materials, and >1,000 species possess medicinal values [4]. Recently, we have listed 318 wild plant species (excluding mushrooms, fruits, spices and condiments, seeds and pulses) that are consumed by Nepalese as vegetables [5]. Wild vegetables are indispensable constituent of the human diet and are the nature's gift to mankind. They are not only cheap but also supply minerals, vitamins and certain hormone precursors. Among them, wild edible ferns play an important role in diet, and they are also a measure of income source with no investment.

Wild plants are globally used by human societies for food, medicine, ornament, defence and industrial purposes. Ferns and fern-allies have unique features in their appearance, natural habitat, food value and ethnomedicinal properties. Ferns possess a wide range of medicinal activities; unfortunately, they are poorly investigated. Comprehensive review on phytochemicals and bioactivities of ferns and fern-allies is rare. It is commonly considered that plants grown in harsh environmental conditions usually possess incredible bioactivity. Therefore, writing of this review article is envisioned to increase scientific attention on the fern species, particularly those grown in high altitudes of Nepal. Consequently, an extensive literature search was conducted. Dissertations, books, journal articles and conference proceedings on ethnobotonical surveys in Nepal were accessed in the libraries to generate a list of wild vegetable food ferns of Nepal. Taxonomic names mentioned in the original articles were verified using several efloral databases. Online literature search was conducted in Google Scholar and Pub Med by using the terms ferns, pteridophytes and individual name of the fern species. Cited references in the published research articles were also traced to obtain information on pharmacognosy, phytochemicals and bioactivites of the fern species grown across the globe.

2. Ferns and fern-allies (pteridophytes)

Fern and fern-allies (pteridophytes) are considered as a very ancient family. They are the first vascular land plants that evoluted during the Devonian and Carboniferous periods of the Paleozoic era [6]. Pteridophytes dominated the earth's vegetation in the beginning of the Mesozoic era, about 280–230 million years ago [7, 8]. Ferns are consumed as vegetables in many countries across the globe and they are also used in the traditional Chinese medicines [9, 10]. However, surprisingly, compared to other vascular plants, pteridophytes are remain under-explored both in ethnobotanical and pharmacological aspects. In the last decade, some natural compounds have been isolated from different fern species and some phramacognostical studies are begun [11]. Initially, traditional knowledge based ferns were ethnomedicinally used for some ailments, and the major studies on pteridophytes were primarily focused on taxonomic identification.

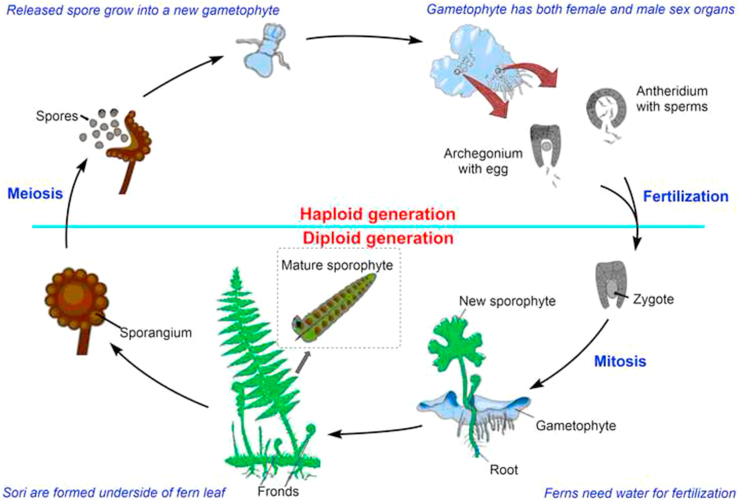

Ferns are seedless vascular plants and they reproduce by sporulation. They have many similar features of mosses and algae, but are usually differentiated from them by having xylem and phloem to transport water and nutrient materials. Like other vascular plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms), they possess stems, fronds, pinnae and roots. The life-cycle of fern is referred to as alternation of generations with two different stages‒gametophyte phase (sexual) and sporophyte phase (asexual) (Figure 1). Motile male gametes (antherozoids) are produced from antheridia and non-motile female gametes (egg cells) are bornt singly in archegonia. Fusion of both the gametes results in the formation of a zygote, which develops into the sporophyte (diploid) after mitotic divisions. Fern sporophytes are free-living, independent on the gametophyte (prothallus), dominant and grow to a much larger size. Mature sporophyte bears sori on the underside of the blade. Sporangia release a number of non-motile spores that germinate and grow by mitotic divisions into haploid gametophytes.

Figure 1.

Fern lifecycle.

It has been estimated that there are around 4,03,000 plant species in the earth including phanerogams and cryptogams [12]. About 13,271 species of pteridophytes are distributed which forms nearly 3% of the world flora [13]. The Plant List has listed 35 plant families and 568 genera of pteridophytes [14]. About 63 families, 230 genera and 2,600 species of pteridophytes have been reported in China [15]. From India, 33 families, 130 genera and 1,267 species of ferns and fern-allies are reported [16]. About 37 families, 687 species in Japan [17]; 801 species in Taiwan [18]; 39 families, 144 genera, 1,100 species in the Philippines [19]; 1,165 species in Malaysia [20], and 670 species of pteridophytes in Thailand [21] have been reported.

In Nepal, ferns are called as “Unyu/Oony” and they are distributed between 60 to 4,800 m above sea level (asl) [22, 23]. Thapa et al. [24] have listed 535 species of pteridophytes belonging to 35 families and 102 genera from Nepal. Recently, a book Ferns and Fern-allies of Nepal [25] has been published including annotated checklist and critical account of 550 species and additional 32 sub-species, altogether 582 taxa of fern and fern-allies of Nepal belonging to 32 families and 99 genera. In Nepal, Deparia boryana, Diplazium esculentum, Dryopteris cochleata, Ophioglossum vulgatum, Pteridium revolutum, Diplazium maximum, Diplazium spectabile, Diplazium stoliczkae, Polystichum squarrosum, Pteris biaurita, Tectaria gemmifera, etc. are popularly consumed as vegetables, and they are also sold in the markets [5, 26]. Popularity gained in consumption of ferns in Nepalese communities is not only due to their unique taste but also due to beliefs of their high nutritional contents such as vitamin C and iron [27]. Obviously, it is considered that the nutritional value and mineral content in wild edible plants are richer than that of commercial vegetables [28]; therefore, their consumption for the nutritional purpose should be encouraged. At the same time, their poor availability and prone vulnerability are the serious issues.

3. History, expeditions and literature on Nepalese pteridophytes

Species Plantarum, originally published in 1753 by Carl Linnaeus, is the first botanical work that applied the binomial nomenclature sytem for the taxonomic description of 5,940 plant species, and recognized 15 fern genera [29]. The pioneering plant collection and taxonomic study of Nepalese pteridophytes were first begun in the early 19th century when Scottish Franchis Buchannan (later known as Franchis Hamliton) collected 433 plant specimens including 34 species of Nepalese pteridophytes in 1802–1803 and published An Account of Kingdom of Nepal [30, 31, 32]. In subsequent historical book publications, namely, Tentamen Florae Nepalensis Illustratae by Wallich [33], Prodromus Florae Nepalensis by Don [34], The Flora of British India by Hooker [35], Index Filicum by Moore [36], A Priced Catalogue of Hardy Exotic and British Ferns by Sim [37], Catalogue of the Plants of Kumaon by Duthie [38], Notes from a Journey to Nepal by Burkill [39] and A Plantsman in Nepal by Lancaster [40] have documented many Nepalese ferns. Some foreign authors have also contributed in the taxonomic identification of pteridophytes of Nepal [41, 42, 43, 44].

After establishement of Botanical Survey and Herbarium Office by Nepal Government in 1961 (later renamed as National Herbarium and Plant Laboratories), Nepalese botanists have started collection of plants and preservation of herbariums, and then they could publish several articles and books [45]. Earlier contributions are made by Gurung [46, 47, 48, 49] and Manandhar [50, 51, 52, 53] followed by others [24, 54, 55, 56, 57].

A major contribution of plant collection and taxonomic studies on Nepalese pteridophytes including Sikkim Himalayan ferns has been made by Christopher Fraser-Jenkins, a Welsh pteridologist, who resides for 40 years in Kathmandu, Nepal. Formerly, he was a research fellow at the Natural History Museum, London, and at the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh. Lately, he worked in conjunction with the National Herbarium and Plant Laboratories Godawari, Nepal. He has spent more than five and half decades in studying Himalayan pteridophytes and published Ferns and Fern-allies of Nepal, Vols. 1–3 [58, 59, 25]; Annotated Checklist of Indian Pteridophytes, Parts 1–3 [60, 61, 62]; including a series of other publications [63, 64, 65].

A number of works on exploration, taxonomic identification and documentation along with rare molecular study on Nepalese pteridophytes have been made; however, not only Nepalese but also global edible peridophytes are poorly investigated for their phytochemical constituents and pharmacological effects. Therefore, exploitation of both edible and non-edible fern flora deserves serious attention by scientific communities [66].

4. A list of wild edible ferns of Nepal

From the literature survey of the publications on Nepalese ferns by various authors, we have generated a list of 33 edible fern species (Table 1). The taxonomic identification of the species was followed according to Kramer and Green [67], modified by Fraser-Jenkins [65], and was cross-verified in the e-databases of The Plant List [68] and Flora of China [69]. Cornopteris decurrenti-alata and Matteuccia intermedia are rarely occurred in Nepal, while Blechnum orientale, Osmunda japonica, Coniogramme intermedia and Pteris wallichiana are common species [31]. These species are used as fern food in China [70]. We could not find proper documentation for these pteridophytes as wild edible ferns of Nepal; therefore, they are omitted in the list. The pteridophytes, which consumed for the medicinal values, but not eaten as salad or cooked vegetables, are also not included in the table [71].

Table 1.

List of edible ferns and fern-allies of Nepal that eaten as vegetables.

| SN | Botanical name [synonym] | Local name (in different community) | Habit | Vegetative parts | Altitude | Season | Availability | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athyriaceae | ||||||||

| 1 | Athyrium atkinsonii Bedd. | Niuro | Herb | Young leaf | 1,200‒4,000 | - | Common | [25, 31, 72] |

| 2 | Athyrium strigillosum (T. Moore ex E. J. Lowe) T. Moore ex Salomon | Niguro | Herb | Young frond | 600‒2,600 | - | Common | [25, 31] |

| 3 | Deparia boryana (Willd.) M. Kato [Dryoathyrium boryanum (Willd.) Ching] | Kalo niuro, Dhengan (Tamang) | Herb | Leaf, tender shoot | 400‒3,300 | May–Jul | Common | [26, 31, 73, 74, 75, 76] |

| 4 | Diplazium esculentum (Retz.) Sw. | Masino niuro, Chipley niuro, Kuturke, Pani nyuro, Piraunli | Herb | Young leaf | 100‒1,300 | Apr–Oct | Common | [23, 26, 31, 73, 74, 77, 78] |

| 5 | Diplazium kawakamii Hayata | Niuro, Jire ningro (Darjiling) | Herb | Tender shoot | 1,300‒2,400 | - | Common | [31, 59, 72] |

| 6 | Diplazium maximum (D. Don) C. Chr. [Allantodia maxima (D. Don) Ching] | Neuro | Herb | Leaf | 9,00–1,800 | May–Jul | Common | [26, 31, 79] |

| 7 | Diplazium spectabile (Wall. ex. Mett.) Ching [Allantodia spectabilis (Wall. ex Mett.) Ching] | Saune niuro | Herb | Leaf | 1,500‒2,700 | May–Jul | Common | [26, 31] |

| 8 | Diplazium stoliczkae Bedd. [Allantodia stoliczkae (Bedd.) Ching] | Kalo niuro, Lekh chipley niuro, Bhandhengan (Tamang) | Shrub | Tender shoot, leaf | 1,300‒4,000 | May–Jun | Common | [26, 31, 76, 80] |

| Blechnaceae | ||||||||

| 9 | Stenochlaena palustris (Burm. f.) Bedd. | - | Climber | Young shoot | 60–900 | - | Rare | [25, 31, 72] |

| 10 | Woodwardia unigemmata (Makino) Nakai | - | Shrub | Stem | 400‒3,000 | Jun–Jul | Common | [26, 31, 73, 74] |

| Cyatheaceae | ||||||||

| 11 | Cyathea spinulosa Wall. ex Hook. [Alsophila spinulosa (Wall. ex Hook.) R.M. Tryon] | Chattre, Rukh uniyu, Thulo uniyu, Jatashankari (Indian) | Shrub | Young shoot | 300‒1,600 | Jul–Aug | Scattered to common | [23, 31, 81] |

| Dennstaedtiaceae | ||||||||

| 12 | Pteridium revolutum (Blume) Nakai [Pteridium aquilinum subsp. wightianum (J. Agardh) W.C. Shieh] | Saune niuro, Ainu | Herb | Shoot | 600‒3,000 | Jul–Jul | Common | [8, 26, 31, 73, 74] |

| Dryopteridaceae | ||||||||

| 13 | Dryopteris cochleata (D. Don) C. Chr. | Pani niuro, Ghee niuro, Danthe niuro, Lotah niuro | Herb | Tender leaf | 1,200‒1,600 | Mar–Oct | Common | [23, 26, 31, 72, 78, 80, 82] |

| 14 | Dryopteris splendens (Hook. ex Bedd.) Kuntze | Danthe neuro | Herb | <1,000 | Jul–Sep | Scattered | [31, 83] | |

| 15 | Polystichum squarrosum (D. Don) Fée [Polystichum apicisterile Ching & S.K. Wu] | Phusre niuro, Rato unyu | Herb | Shoot | 1,900‒2,400 | May–Jun | Common | [26, 31, 73, 74, 80] |

| Lygodiaceae | ||||||||

| 16 | Lygodium flexuosum (L.) Sw. | Parandi sag, Lahare unyu | Climber | Young shoot, leaf | 60‒1,000 | Whole year | Common | [23, 31, 74] |

| 17 | Lygodium japonicum (Thunb.) Sw. | Janai lahara, Nagbeli, Lute jhar, Ukuse jhar (Magar), Pinse (Tamang) | Climber | Leaf | 60‒3,900 | May–Jun | Common | [23, 26, 31, 74, 84] |

| Marsileaceae | ||||||||

| 18 | Marsilea quadrifolia L. | Charpate behuli | Herb | Tender shoot | 900‒1,700 | [85] | ||

| Nephrolepidaceae | ||||||||

| 19 | Nephrolepis cordifolia (L.) C. Prest | Pani amala, Bhui amala, Ras amala, Ambeli (Tamang), Pani saro (Majhi) | Herb | Tuber, shoot | 60‒2,400 | Jul–Sep | Common | [23, 31, 74, 75, 77, 81] |

| Ophioglossaceae | ||||||||

| 20 | Botrychium lanuginosum Wall. ex Hook. & Grev. | Jaluko, Bayakhra | Herb | Shoot | 1,000–3,000 | May–Jun | Common | [26, 31, 74] |

| 21 | Helminthostachys zeylanica (L.) Hook | Majurgoda (Chepang), Kamsaj (Tharu) | Herb | Tender shoot | <1,000 | Scattered | [31, 75] | |

| 22 | Ophioglossum nudicaule L.f. | Jibre sag | Herb | Leaf | 1,800‒4,300 | Mar–Apr | Common | [26, 73, 74] |

| 23 | Ophioglossum petiolatum Hook. | Jibre sag | Herb | Leaf | 200‒3,300 | Feb–Apr | Scattered | [31, 84] |

| 24 | Ophioglossum reticulatum L. | Jibre sag, Ek patiya (Tharu), Jibre dhap (Tamang) | Herb | Young leaf, tender shoot | 1,100‒4,000 | Mar–Apr | Common | [26, 31, 73, 74, 77, 80] |

| 25 | Ophioglossum vulgatum L. | Jibre sag | Herb | Whole plant | <3,000 | Mar–Apr | Common | [74] |

| Osmundaceae | ||||||||

| 26 | Osmunda claytoniana L. [Osmunda claytoniana subsp. vestita (Milde) Á. Löve & D. Löve] | Kuthurke | Herb | Leaf | 1,600‒3,400 | May–Jun | Common | [26, 31, 73, 74, 77] |

| Pteridaceae | ||||||||

| 27 | Ceratopteris thalictroides (L.) Brongn. | Pani dhaniya, Dhaniya jhar | Herb | Whole plant | <1,000 | Jun–Aug | Scattered | [23, 31, 74, 85, 86, 87] |

| 28 | Pteris biaurita L. [Pteris flavicaulis Hayata] | Haade unyu, Kuthurke niuro (Raji) | Herb | Young leaf, shoot | 200‒2,500 | Aug–Oct | Common | [23, 31, 78, 88] |

| 29 | Pteris vittata L. | Unigar, Urakthewn | Herb | Shoot, rhizome | 400‒3,000 | Jul–Sep | Common | [23, 31, 74] |

| Tectariaceae | ||||||||

| 30 | Tectaria gemmifera (Fée) Alston [Tectaria coadunata C. Chr.] | Danthe niuro, Kuthurke, Toplign degni (Tamang) | Herb | Young leaf, shoot | 500‒2,500 | Jun–Oct | Common | [23, 26, 31, 73, 74, 78, 82, 86, 89, 90] |

| 31 | Tectaria zeylanica (Houtt.) Sledge [Osmunda zeylanica L.] | Mayur kutea, Dhagrajawa (Tharu) | Herb | Leaf | 100‒1,000 | Mar–Apr | [74, 77] | |

| Thelypteridaceae | ||||||||

| 32 | Thelypteris auriculata (J. Sm.) K. Iwats [Cyclosorus auriculata (J. Sm.) C.M. Kuo] | Kochaya | Herb | Shoot | 1,600‒1,800 | Mar–May | Common | [31, 74] |

| 33 | Thelypteris nudata (Roxb.) C.V. Morton [Thelypteris multilineata (Wall. ex Hook.) C.V. Morton; Pronephrium nudatum (Roxb.) Holttum] | Koche (Tharu) | Herb | Shoot | 2,100 | Jun–Jul | Common | [26, 31, 73, 74] |

5. Distribution, ethnomedicine, pharmacognosy and phytochemistry of the wild edible ferns

It has been recently reported that there are 582 taxa of pteridophytes in Nepal [72]; however, Nepalese researchers have not been focused in the ethnopteridological studies in traditional medicinal knowledge, food safety and phytoconstituents present in the pteridophytes. At the same time, surprisingly, very few scientific studies have been carried out globally in the areas of the chemical constituents and pharmacological activites of pteridophytes [71]. In this section, we accumulate available information on the distribution, ethnomedicinal uses, pharmacognosy and phytochemistry of the wild edible ferns listed in Table 1.

C (central), N (north), E (east), W (west) and S (south) abbreviations are used to indicate distribution of the fern species. The edible fern distribution in China and India is specified as available in different provinces.

5.1. Athyriaceae

5.1.1. Athyrium atkinsonii

5.1.1.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Chongqing, Fujian, Gansu, Guizhou, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Sichuan, Xizang and Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Pakistan; Bhutan; Myanmar; Taiwan; S Korea; Japan; etc. [31, 69].

5.1.1.2. Habitat

Damp forest at high altitude.

5.1.1.3. Phytochemistry

The plant material contains carbohydrates, proteins, alkaloids, phenolics, flavonoids, etc. [91].

5.1.2. Athyrium strigillosum

5.1.2.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hunan, Jiangxi, Sichuan, Xizang and Yunnan; Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Pakistan; Bhutan; Myanmar; Taiwan; Japan; etc. [31, 69].

5.1.2.2. Habitat

Wet forest and partially exposed area or along banks and beds of well-shaded ravines.

5.1.3. Deparia boryana [Dryoathyrium boryanum]

5.1.3.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan, Hunan, Shaanxi, Sichuan, SE Xizang, Yunnan and Zhejiang; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Bhutan; Sri Lanka; Myanmar; Thailand; Vietnam; Malaysia; Indonesia; Philippines; Taiwan; Africa; etc. [31, 69].

5.1.3.2. Habitat

Densely forested ravine with waterfalls, moist and shade places.

5.1.3.3. Ethnomedicine

The tender shoot is used as demulcent, stomachic and laxative [92]. The powder or paste is used to treat dysentery [93]. Rhizome is used in abdominal spasm [75]. Root paste is applied externally to treat burns, injury and wounds [76].

5.1.3.4. Pharmacognosy

The ethyl acetate extract inhibits the lipid formation with 35% at 100 μg/mL in 3T3-L1 cell model [92]. Antioxidant as well as anticancer activities are explored [92, 94].

5.1.3.5. Phytochemistry

The polyphenolic content in the aerial parts is 266 μg gallic acid equivalent/mg [92]. The total flavonoids content is estimated about 145.8 mg/g [94]. By using HPLC–DAD–ESI–MS, 3-hydroxyphloretin 6′-O-hexoside, quercetin-7-hexoside, apigenin7-O-glucoside, luteolin 7-O-glucoside, apigenin 7-O-galactoside, acacetin 7-O-(α-D-apio-furanosyl) (1→6)-β-D-glucoside, 3-hydroxy phloretin 6-O-hexoside, luteolin-6-C-glucoside, kaempferol 3-O-glucoside, etc. are tentatively identified in the plant extract [94].

5.1.4. Diplazium esculentum

5.1.4.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Anhui, Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan, Hunan, Jiangxi, Sichuan, Xizang, Yunnan and Zhejiang; Arunachal; Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Pakistan; Bhutan; Taiwan; etc. [31, 69].

5.1.4.2. Habitat

Moist, shade forest and rocks.

5.1.4.3. Ethnomedicine

Young fronds are used as tonic and eaten for laxative effect [95]. Aerial parts are used to treat fever, pain, glandular swelling, diarrhea, dermatitis, wound and measles. The rhizome is considered as anthelmintic, antidysenteric, antidiarrheal and pest repellent [96]. It is also used in cough, asthma, fever, dyspepsia and stomachache. Decoction of rhizome and young leaves are useful in haemoptysis and constipation. Rhizomes are also used in scabies and boils [53]. A paste of leaf and stem is applied externally to treat cuts and wounds [97].

5.1.4.4. Pharmacognosy

Biological activities of the leaf extracts such as antimicrobial [98, 99, 100], antioxidant [101, 102, 103, 104], antidiabetic [103], anticaner [105], anti-inflammatory [99, 106], hepatoprotective [103], anti-Alzheimer's [104], etc. have been reported. Antibacterial [96] and anthelmintic activities of the rhizomes are reported [107].

5.1.4.5. Phytochemistry

Estimation of quercetin in the plant is performed [108]. Proximate analysis shows the presence of fat (3.4%), protein (10.7%), fiber (9.1%), total phenolics (125.6 mg gallic acid equivalent/100 g) and total flavonoids (110.8 mg quercetin equivalent/100 g) [109]. Total phenolics (167.7 mg gallic acid equivalent/100 g) and total flavonoids (70.8 mg quercetin equivalent/100 g) in the hydroalcoholic extract are separately reported by Junejo et al. [103]. Qualitative phytochemical screening shows the presence of carbohydrates, fats, alkaloids, anthraquinones, phenolics, saponins, cyanidins, cardiac glycosides, steroids, flavonoids, terpenoids, etc. [110]. Evaluation of vitamin C (22.2 mg/100 g), mineral contents (Ca, Cu, Fe, Mg, Mn, Na and Zn), heavy metals (Al, As, Cd, Hg, Li, Ni and Pb), etc. are performed in the leaves [27]. β-Pinene (17.2%), α-pinene (10.5%), caryophyllene oxide (7.5%), sabinene (6.1%), 1,8-cineole (5.8%), α-cardinol (4.8), β-caryophyllene (4.3%) are identified as the major volatile constituents in the essential oil obtained from the leaves [111]. Pentadecanoic acid, α-linolenic acid, phytol, β-sitosterol, stigmasta-5,22-dien-3-ol, methyl palmitate, diisobutyl phthalate, neophytadiene, 10,12-hexadecadien-1-ol, etc. are identified in the extracts of young fronds from Indian Himalaya [112].

Ascorbic acid [113], eriodictyol 5-O-methyl ether 7-O-β-D-xylosylgalactoside [114], α-tocopherol [115], quercetin [108, 116], ptaquiloside [117], pterosin [108], hopan-triterpene lactone [118], lutein [119], etc. are isolated from the edible parts of D. esculentum. Phenolics ((2R)-3-(4′-hydroxyphenyl)lactic acid, trans-cinnamic acid, protocatechuic acid and rutin) and ecdysteroids (amarasterone A1, makisterone C and ponasterone A) are recently isolated from the young fronds collected in Japan [120].

5.1.5. Diplazium kawakamii

5.1.5.1. Distribution

E Nepal; Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim and Darjeeling; Bhutan; Taiwan; Japan; etc. [31, 69].

5.1.5.2. Habitat

Wet, densely forested ravine and besides streamlets.

5.1.6. Diplazium maximum [Allantodia maxima]

5.1.6.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Fujian, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan, Jiangxi, Xizang and Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Pakistan; Afghanistan; Bhutan; Myanmar; etc. [31, 69].

5.1.6.2. Habitat

Valley, evergreen forest, besides streamlets and north-west facing slopes.

5.1.6.3. Ethnomedicine

Young shoots are used in stomach problem [79].

5.1.6.4. Pharmacognosy

Fronds exhibit antioxidant potentiality [121].

5.1.6.5. Phytochemistry

The plant material contains alkaloids, phenolics, tannins, saponins, flavonoids, terpenoids, etc. [91]. Chettri et al. have estimated total crude fat (2.5%), fiber (11.3%), protein (13.4%), vitamin C (25.4 mg/100 g) and several metal contents [27]. Fronds have high contents of dietary fibre (38.3%) and crude protein (25.4%) [121]. It constitutes several fatty acids and phenolics like catechin, epicatechin, procatechuric acid, myricetin, etc.

5.1.7. Diplazium spectabile [Allantodia spectabilis]

5.1.7.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Yunnan and Xizang; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Bhutan; etc. [31, 69].

5.1.7.2. Habitat

South facing forest and valley, evergreen broad-leaved forests and besides streamlets.

5.1.7.3. Phytochemistry

Crude fat (0.2%), fiber (3.4%), protein (3.6%), vitamin C (21.6 mg/100 g), mineral contents (Ca, Cu, Fe, Mg, Mn, Na and Zn), heavy metals (Al, As, Cd, Hg, Li, Ni and Pb), etc. are determined in the leaves [27].

5.1.8. Diplazium stoliczkae [Allantodia stoliczkae]

5.1.8.1. Distribution

C and E Nepal; Xizang; Arunachal; Sikkim and Darjeeling; Bhutan; etc. [31].

5.1.8.2. Habitat

Dense forest.

5.1.8.3. Ethnomedicine

Root paste is applied externally to cure burn, injury and wounds [53]. Leaf juice is given to treat diarrhea and dysentery [122].

5.1.8.4. Phytochemistry

Total phenolic content (440.6 mg gallic acid equivalent/g) and flavonoid content (625.5 quercetin equivalent/g) together with antioxidant activity in the rhizomes have been investigated [123].

5.2. Blechnaceae

5.2.1. Stenochlaena palustris

5.2.1.1. Distribution

E Nepal; Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan and Yunnan; Arunachal, Assam, Sikkim and Darjeeling; Thailand; Laos; Vietnam; Cambodia; Malaysia; Indonesia; Australia; Pacific islands; etc. [31, 69].

5.2.1.2. Habitat

Secondary forest, open forests and interior on the hills.

5.2.1.3. Ethnomedicine

Leaves decoction cures fever [124]. Fronds are used traditionally to treat fever, diarrhea, skin diseases, cutaneous disorders and gastric ulcers [125, 126].

5.2.1.4. Pharmacognosy

Fronds extracts show antifungal [127], antibacterial [128], antioxidant [[129], [130], [131]], and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory [126] activities. Antimalarial activity of the leaf extract is recently reported [132].

5.2.1.5. Phytochemistry

Leaves constitute stenopalustrosides A−E, kaem-pferol 3-O-(3″-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-(6″-O-E-feruloyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-(3″,6″-di-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-(3″-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-(6″-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, (4S∗,5R∗)-4-[(9Z)-2,13-di-(O-β-D-glucopyranosyl)-5,9,10-trimethyl-8-oxo-9-tetradecene-5-yl]-3,3,5-trimethylcyclohexanone, 1-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(2S∗,3R∗,4E,8Z)-2-N-[(2R)-hydroxytetracosanoyl]octadecasphinga-4,8-dienine, 3-oxo-4,5-dihydro-α-ionyl β-D-glucopyranoside, 3-formylindole, lutein and β-sitosterol-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside [128, 133].

Fronds contain kaempferol 3-O-β-glucopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-(3″-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-(6″-O-E-feruloyl)-β-glucopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-(3″,6″-di-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-glucopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-(6″-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-glucopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-(3″-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-glucopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-α-rhamnopyranoside and kaempferol 3-O-(6″-O-α-rhamnopyranoside)-β-glucopyranoside [126].

5.2.2. Woodwardia unigemmata [Woodwardia biserrata]

5.2.2.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Fujian, Gansu, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Shanxi, Sichuan, Xizang and Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Pakistan; Bhutan; Myanmar; Vietnam; Philippines; Taiwan; Japan; etc. [31, 69].

5.2.2.2. Habitat

Densely forested gully and slopes below trees, exposed and shaded places or wet localities along roadsides.

5.2.2.3. Ethnomedicine

Fronds are used in dysentery, skin diseases and infirtility [134, 135, 136]. Leaf is used for abdominal pain, constipation and sore throat [135]. Rhizome is used as purgative.

5.2.2.4. Pharmacognosy

Antioxidant [137, 138] and antibacterial [138] activitities of the aerial parts are reported. Anti-HIV activity has been shown by the rhizome extracts [139, 140].

5.2.2.5. Phytochemistry

Total phenolic and flavonoid contents in the aerial parts are reported [137, 138]. GC-MS analysis of the aerial parts shows the presence of catechol (22%), glycerol (20.2%), n-pentadecanoic acid (6.9%), glyceryl monoacetate (6.3%), ethyl acetimidate (5.4%) and 3-hydroxy-2,3-dihydromaltol (5.4%) in the aqueous extract; β-sitosterol (17.4%), pentadecanoic acid (9.8%), vitamin E (7.8%) and glycerol (7.0%) in the methanolic extract; and γ-sitosterol (33.4%), vitamin E (10.0%) and campesterol (7.3%) in the hexane extract [138]. From the roots, crassirhizomosides B–C, sutchuenoside A, kaempferol 3-O-α-L-(3-O-acetyl) rhamopyranoside-7-O-α-L-rhanopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-α-L-(2-O-acetyl) rhamopyranoside-7-O-α-L-rhanopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-α-L-rhamopyranoside-7-O-α-L-rhanopyranoside and kaempferol 3-O-α-L-(3,4-O-di-acetyl) rhamopyranoside-7-O-α-L-(4-O-acetyl)rhanopyranoside are isolated [11].

5.3. Cyatheaceae

5.3.1. Cyathea spinulosa [Alsophila spinulosa]

5.3.1.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Chongqing, Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan, Jiangxi, Sichuan, Xizang and Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling and Uttarakhand; Bhutan; Bangladesh; Sri Lanka; Myanmar; N Thailand; Taiwan; S Japan; etc. [31, 69].

5.3.1.2. Habitat

Densely forested ravine with waterfalls and shade places.

5.3.1.3. Ethnomedicine

It is useful as hair tonic, sudorific and aphrodisiac [141]. Young leaf is taken orally in excessive bleeding during menstrual period [97]. Pith decoction is given in pains and bodyaches [142]. Rhizomes are used againts snake bites [143].

5.3.1.4. Pharmacognosy

Leaves possess antioxidant and anti-Alzheimer's potentiality [144].

5.3.1.5. Phytochemistry

From the fronds, hegoflavones A−B are isolated [145]. From the leaves, (2S,3S,4R)-2-[(2′R)-2′-hydroxytetracosanoylamino]-1,3,4-octadecanetriol, 1-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(2S,3R,4E,8Z)-2-[(2-hydroxyoctadecanoyl) amido]-4,8-octadecadiene-1,3-diol, 3α-hydroxyfilic-4(23)-ene, 2-oxofilic-3-ene, hop-22(29)-ene fern-7-ene, cycloaudenyl palmitate, daucosterol, dryocrasol, ergosterol, fern-9(11)-ene, filic-3-ene, hopan-29,17α-olide, hopan-17α,29-epoxide, hydroxyhopane, protocatechuic aldehyde, sitostanol, sitosterol, sitosteryl palmitate, stigmast-3,6-dione, stigmast-4-ene-3,6-dione and tetrahymanol are isolated [146, 147]. From the stalks, (E)-4-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl caffeic acid, 1-O-hexadecanolenin, 3,4,6-trihydroxy-1-ring vinyl carboxylic acid, 30-O-β-D-xylopyranosyl-dryocrassol, 4-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-p-coumaric acid, 6β-hydroxy-24-ethyl-cholest-4-en-3-one, 9α-hydroxy-1β-methoxycaryolanol, clovandiol, cyathenosin A, daucosterol, decumbic acid, isorientin, n-tetracosane, pimaric acid, protocatechualdehyde, protocatechuic acid, stigmastane-3,6-dione, vitexin and β-sitosterol are isolated [148, 149].

5.4. Dennstaedtiaceae

5.4.1. Pteridium revolutum [Pteridium aquilinum subsp. Wightianum]

5.4.1.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Gansu, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Xizang, Yunnan and Zhejiang; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Pakistan; Bhutan; Taiwan; N Australia; etc. [31, 69]. P. aquilinum, known as bracken fern, is one of the most commonly distributed weed species that grows in many types of soil with extreme high rate of reproduction [150].

5.4.1.2. Habitat

Exposed and shaded places, and open humus-rich forests.

5.4.1.3. Ethnomedicine

It is an ornamental fern that planted for indoor decoration and borders [151]. It is traditionally used for animal bedding [52]. The rhizomes are astringent and useful in diarrhea, intestinal inflammation and wounds. The rhizomes are also used for making breads and brews. The plant juice is considered antibacterial.

5.4.1.4. Pharmacognosy

It contains poisonous cyanogen glycosides which are antithiamine and carcinogenic. It has been demonstrated that feeding of the plant induces urinary bladder tumors, illeum sarcomas, pulmonary adenomas and leukemia [152, 153]. However, Yoshihira et al. performed toxicity tests and found that none of the plant extracts and the fractions could induce tumors under the conditions studied [154].

5.4.1.5. Phytochemistry

The rhizome constitutes the bitter starch [151]. It contains carbohydrate (51%), protein (9.5%), fat (1.2%), fibre (20%) and ash (8.3%). The fronds contain protein (1%), fat (0.1%), fibre (1.4%), minerals (0.6%), β-carotene (1 mg/100 g) and iodine (900 μg/kg). Phytochemical screening of the fronds grown in the Philippines reveals the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids and tannins [99]. Prunasin, a main cyanogen component in the fern that can release HCN to induce cyanogenesis, has been estimated about 10.4–61.3 mg/g in fresh plant tissue [155]. Ptaquiloside and quercetin are estimated in the plant material [108].

Several sesquiterpens have been isolated from the fronds that include pterosins A‒G, I‒J, K‒L, N, O, Z, etc. [156, 157, 158, 159]. Thiaminases 1 and 2 are isolated, which cause vitamin B1 deficiency in animals [160]. Steroids α- and β-ecdysones are identified in the bracken fern [161].

5.5. Dryopteridaceae

5.5.1. Dryopteris cochleata

5.5.1.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Guizhou, Sichuan and Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Pakistan; Bhutan; Bangladesh; Myanmar; Thailand; Indonesia; Philippines; etc. [31, 69].

5.5.1.2. Habitat

Moist and shady slopes, and roadsides.

5.5.1.3. Ethnomedicine

Decoction of rhizome, stem and stripe is given for blood purification [162]. Dried rhizome powder is internally taken to cure diarrhea [134]. Root decoction is used in cuts and throat problems. It is antibacterial, antiepileptic, and effective in rheumatism, amoebic dysentery and leprosy [163]. The juice of fronds is used to treat muscular and rheumatic pain [164].

5.5.1.4. Pharmacognosy

Antibacterial [165] and antioxidant [166] activities of the leaf extracts, and antimicrobial [167] activity of the rhizome extracts have been reported.

5.5.1.5. Phytochemistry

Leaves contain fat (3.6%), fiber (11.2%), protein (20.1%), vitamin C (23.1 mg/100 g) and minerals (Ca, Cu, Fe, Mg, Mn, Mo, Na, Zn, Al, As, Cd, Hg, Li, Ni and Pb) [27]. Preliminary phytochemical screenings and GC-MS analyses of the rhizomes and leaves extracts are reported [166, 167, 168]. The amounts of ptaquiloside and quercetin are estimated in the plant material [108].

5.5.2. Dryopteris splendens

5.5.2.1. Distribution

E. Nepal; Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim and Darjeeling; Bhutan; etc. [31, 69].

5.5.2.2. Habitat

Densely forested gully and slopes below trees, and evergreen and deciduous braod-leaved forests.

5.5.3. Polystichum squarrosum [Polystichum apicisterile]

5.5.3.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; S Xizang; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Pakistan; Bhutan; etc. [31, 69].

5.5.3.2. Habitat

Near streams and tree shades.

5.5.3.3. Pharmacognosy

Leaf extracts show antifungal [169] and antioxidant [165] activities. P. squarrosum fed rats show moderate mortality, splenomegaly and develop neoplastic lesions awaring its toxic effects [170].

5.5.3.4. Phytochemistry

The amounts of ptaquiloside and quercetin are estimated in the leaves [108].

5.6. Lygodiaceae

5.6.1. Lygodium flexuosum

5.6.1.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan, Hunan and Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand and Himachal; Bhutan; Sri Lanka; Thailand; Vietnam; Malaysia; Philippines; S Japan; E Australia; etc. [31, 69].

5.6.1.2. Habitat

Interior exposed area.

5.6.1.3. Ethnomedicine

The plant is used as an expectorant [171]. Root is smoked as cigarette [172]. Fresh root is boiled with mustard oil and then used for massage to treat rheumatism and sprains. It is also used for the treatment of jaundice, dysmenorrhea, wounds and eczema. Plant ash is used for treating gonorrhea, herpes, and other foot and mouth diseases. The whole plant is used in sprain, fracture, cuts and wounds [173].

5.6.1.4. Pharmacognosy

Antifertility [174, 175], antiproliferative, apoptotic, hepatoprotective [176, 177], antibacterial properties [178, 179] are reported.

5.6.1.5. Phytochemistry

It contains lygodinolide, coumaryl dryocrassol, tectoquinone, kaempferol, kaempferol 3-β-D-glucoside, β-sitosterol and stigmasterol [180, 181, 182]. Several anhidiogens are identified from the spores [183].

5.6.2. Lygodium japonicum

5.6.2.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Anhui, Chongqing, Fujian, Gansu, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Shaanxi, Shanghai, Sichuan, Xizang, Yunnan and Zhejiang; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Pakistan; Bhutan; Sri Lanka; Indonesia (Java); Philippines; Taiwan; Korea; Japan; Australia, N America; etc. [31, 69].

5.6.2.2. Habitat

Moist and exposed area, and roadsides.

5.6.2.3. Ethnomedicine

It has been used in China for the treatment of calculi, edema, dysentery, hepatitis, pneumonia, gonorrhea, etc. [184]. Vegetative parts and spores decoction is used for diuretic or cathartic effects [171]. The plant is also used as an expectorant. The plant juice is applied in scabies, boils and wounds, and the paste is used in joint pains [51, 185]. The whole plant is applied to treat whitlow [52].

5.6.2.4. Pharmacognosy

The methanolic extract of the spores shows neuroprotective effect [186].

5.6.2.5. Phytochemistry

The amount of quercetin present in L. japonicum is estimated [108]. GC-MS analysis of the essential oil from the whole herb leads to identify 52 compounds including 3-methyl-1-pentanol (4%), 2-(methylacetyl)-3-carene (4.2%), cyclooctenone (7.6%), (E)-2-hexenoic acid (12.8%) and 1-undecyne (28.6%) [187].

Roots contain 1-hentriacontanol, hexadecanoic acid 2,3-dihydroxy-propyl ester, kaempferol, kaempferol-7-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside, lygodiumsteroside B, p-coumaric acid, tilianin, daucosterol and β-sitosterol [188, 189]. From the aerial parts, 2-O-caffeoyl-D-glucopyranose, 3-O-caffeoyl-D-glucopyranose, 4-O-caffeoyl-D-glucopyranose, 4-O-pcoumaroyl-D-glucopyranose, 6-O-caffeoyl-D-glucopyranose, 6-O-p-coumaroyl-D-glucopyranose, caffeic acid and p-coumaric acid are isolated [190]. Antheridiogens are identified in the spores [191, 192].

Interestingly, L. japonicum grown in the metal-enriched conditions can accumulates copper in the cell wall pectin [193].

5.7. Marsileaceae

5.7.1. Marsilea quadrifolia

5.7.1.1. Distribution

C and E Nepal; Gansu, Hebei, Heilongjiang, Henan, Jilin, Liaoning, Nei Mongol, Ningxia, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Shandong and Shanxi; Arunachal, Sikkim and Darjeeling; Bhutan; Korea; Japan; America; Europe; etc. [69, 85].

5.7.1.2. Habitat

Ponds and paddy fields.

5.7.1.3. Ethnomedicine

It produces aphordisiac effect [124]. Leaf juice is anti-inflammatory, diuretic, depurative, febrifuge and refrigerant [194]. The plant is useful to relieve hypertension, sleep disorder, headache, cough, convulaion, repiratory troubles, nervous problems, constipation, dyspepsia, etc. [195, 196]. It is also used in the treatment of leprosy, haemorrhoids, fever and insomnia [197]. It is a famine food and only used during food scarcity.

5.7.1.4. Pharmacognosy

The plant extracts exhibit antibacterial [196, 198, 199, 200], antidiarrheal [194], antifungal [201], analgesic [194], anti-inflammatory [202], antioxidant [203, 204], antidiabetic [205], anti-Alzheimer's [206, 207], antiepileptic [208], anticonvulsive [209], nephroprotective [210] and antitumor [211] activities.

5.7.1.5. Phytochemistry

The plant material contains carbohydrate (19.5% g), protein (4.9%), fat (0.2%), amino acid (3%), flavonoids (0.3%) and saponins (0.3%) [212]. Seasonal variations in the compositions of sodium, potassium, calcium, phosphorus and β-carotene contents in the whole plant have been reported [213]. Total phenolics, flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins and saponins in both leaves and stems have been separately evaluated [214].

Leaves possess alkaloids, steroids, tannins, terpenoids, flavonoids, etc. [200, 202, 208, 214]. 2,3,7,8-Tetracholorodibenzofuran, 3-hydoxy-triacontan-11-one, chlorogenic acid, hentriacontan-6-ol, marsileagenin A, marsilin (1-triacontanol-cerotate), methylamine, pentachlorophenylacetate, quercetin, triacontyl hexacosanoate, tridecyliodide, β-sitosterol, etc. are identified in M. quadrifolia [198, 202, 204].

Zhang et al. have isolated (±)-(E)-4b-methoxy-3b,5b-dihydroxyscirpusin A, (±)-(E)-cyperusphenol A, (±)-(E)-scirpusin A, (E)-caffeic acid 4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, (E)-ethyl caffeate, 4-methy-3′-hydroxypsilotinin, hegoflavone A, kaempferol 3-O-(2″-O-E-caffeoyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-(3″-O-E-caffeoyl)-α-L-arabinopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-(4″-O-E-caffeoyl)-α-L-arabinopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, kaempferol, mesocyperusphenol A, quercetin, quercetin 3-O-(6″-O-E-caffeoyl)-β-D-glucopyranoside, quercetin 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside and quercetin 3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside from the ethanolic extract of M. quadrifolia, and their antioxidant capacity is evaluated [215].

5.8. Nephrolepidaceae

5.8.1. Nephrolepis cordifolia [Nephrolepis auriculata]

5.8.1.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan, Hunan, Taiwan, Xizang, Yunnan and Zhejiang; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling and Uttarakhand; Pakistan; Bhutan; Bangladesh; Sri Lanka; Myanmar; Thailand; Laos; Vietnam; Cambodia; Malaysia; Singapore; Indonesia; Philippines; Korea; Japan; Australia; N and S America; Africa; etc. [31, 69].

5.8.1.2. Habitat

Moist place and roadsides.

5.8.1.3. Ethnomedicine

Tuberous root is used in indigestion, cold, cough, fever, jaundice and burning urination [52, [216]]. It is eaten to cure hypertension and inflammation [185]. Root paste is used in boils and skin problems [217]. Tuber juice is useful in dehydration [218]. Whole plant is used to cure renal, liver and skin disorders [219]. It is useful in chest congestion, rheumatism, jaundice and wounds [220]. Cough is cured by a decoction of the fresh fronds [221].

5.8.1.4. Pharmacognosy

Frond possesses antibacterial and antifungal potentials [99, 222]. Fruit and leaf are evaluated for the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging, α-amylase inhibitory and glucose diffusion inhibition activities [223]. Anthelmintic activity of the aqueous extract of leaves is claimed as it paralyzes earthworms (Pheretima posthuma) at the concentration of 10 mg/mL [224]. Diuretic potential of the rhizome juice is shown [225].

5.8.1.5. Phytochemistry

Proximate analysis of different parts of N. cordifolia grown in Nepal and Nigeria has been reported [226, 227]. Tannins (11.5 mg/100 g), alkaloids (9.1 mg/100 g), flavonoids (16.5 mg/100 g), phenols (8.3 mg/100 g), saponin (1.2 mg/100 g) and glycosides (5.4 mg/100 g) are estimated in the leaflets [227]. Essential oil obtained from the aerial parts constitutes nonanal (10.6%), β-ionone (8%), eugenol (7.2%) and anethol (4.6%) [228]. Sequoyitol, β-sitosterol, fern-9(11)-ene, oleanolic acid, myristic acid octadecylester, hentriacontanoic acid and triacontanol are isolated from the plant material [229].

5.9. Ophioglossaceae

5.9.1. Botrychium lanuginosum

5.9.1.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Guangxi, Guizhou, Hunan, Sichuan, Xizang and Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand and Himachal; Bhutan; Sri Lanka; Myanmar; Thailand; Vietnam; Malaysia; Indonesia; Philippines; Taiwan; New Guinea; etc. [31, 69].

5.9.1.2. Habitat

Moist and shady forest floor.

5.9.1.3. Ethnomedicine

It is used in dysentery and wounds [134, 163, 220, 230]. Rhizomes are used in pneumonia, catarrh and cough [124]. The paste is used as a facial mask, and it is applied in boils on the tongue and on the forehead to relieve headache [50]. Shoots are used in body ache [84].

5.9.1.4. Phytochemistry

Apigenin, luteolin, luteolin-7-O-glucoside, daucosterol, β-sitosterol, (6′-O-palmitoyl)-sitosterol-3-O-β-D-glucoside, thunberginol A, 30-nor-21β-hopan-22-one, 1-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(2S,3R,4E,8Z)-2-[(2R-hydroxy hexadecanoyl) amino]-4,8-octadecadiene-1,3-diol and sucrose are isolated from B. lanuginosum [231].

5.9.2. Helminthostachys zeylanica

5.9.2.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Guangdong, Hainan and Yunnan; Arunachal, Assam, Darjeeling, Bihar and Uttarakhand; Sri Lanka; Thailand; Laos; Vietnam; Cambodia; Philippines; Taiwan; Japan; Australia; Pacific islands; etc. [31, 69].

5.9.2.2. Habitat

Forest, edges of marshes and swampy places.

5.9.2.3. Ethnomedicine

Fronds are used as aphrodisiac [232]. The plant is considered as intoxicant and anodyne. It is useful in impotency, sciatica, dysentery, malaria and to relieve blisters on the tongue [124]. The rhizome is regarded as a tonic [233]. It is also used in dysentery, catarrh and phthisis. The rhizomes are popularly used as an antipyretic and anti-inflammatory Chinese herbal medicine, Daodi-Ugon [234, 235].

5.9.2.4. Pharmacognosy

Rhizomes show hepatoprotective [236, 237], anti-inflammatory [[238], [239], [240]], antihyperuricemia [241], cytotoxic [242], anticancer [243], antidiabetic [244] and antibacterial [245] activities.

5.9.2.5. Phytochemistry

The plant material contains fat (0.6%), crude fibre (1%), calcium (47.9 mg/100 g), phosphorus (91.5 mg/100 g), iron (1.8 mg/100 g), carotene (2.1 mg/100 g), riboflavin (0.1 mg/100 g), niacin (0.9 mg/100 g) and ascorbic acid (45.9 mg/100 g) [233].

From the rhizomes, flavonoids viz. ugonins E‒Y, quercetin, quercetin-4′-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside, quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-4′-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside, 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-6-((2,2-dimethyl-6-methylenecyclohexyl)methyl)-5,7-dihydroxy-chroman-4-one, 2-(3,4-dihydroxy-2-[(2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-2-enyl)methyl]phenyl)-3,5,7-trihydroxy-4 H-chromen-4-one and 5,4′-dihydroxy-4″,4″-dimethyl-5″-methyl-5″H-dihydrofurano[2″,3′′:6,7]flavanone are isolated by Huang et al. [[235], [246], [247], [248]]. Quality of the root and rhizome of H. zeylanica can be determined by using ugonins as markers [249]. Geranyl stilbenes ugonstilbenes A–C and 3-hydroxyacetophenone are isolated from the rhizomes by Chen et al. [234]. Ugonstilbenes A‒C exhibit moderate antioxidant activity. 4′-O-β-D-Glucopyranosyl-quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-D-glucopyranoside and 4′-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-glucopyranosyl-quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-D-glucopyranoside are isolated by Yamauchi et al. [250]. These glycosides display melanogenic acceleratory effect.

From the whole plant, neougonins A‒B, ugonins D‒E, ugonin J, ugonin L, ugonin N, ugonin S, 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-6-((2,2-dimethyl-6-methylenecyclohexyl)methyl)-5,7-dihydroxy-chroman-4-one, etc. are isolated [251].

5.9.3. Ophioglossum nudicaule

5.9.3.1. Distribution

Nepal; SW Sichuan, Xizang, C and NW Yunnan; Darjiling, Sikim, Himanchal, Jharkand, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamilnadu, Jammu and Kashmir; Indonesia; Malaysia; Thailand; etc. [69, 252].

5.9.3.2. Habitat

Rainforest, impermeable soil in open places and by culverts on roadsides in the hills.

5.9.3.3. Ethnomedicine

Fronds are used as a tonic and styptic [253]. It is used in wounds and old skin diseases [52, 254].

5.9.4. Ophioglossum petiolatum

5.9.4.1. Distribution

C and E Nepal; Fujian, Guizhou, Hainan, Hubei, Sichuan, Yunnan and Xizang; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Pakistan; Uzbekistan; Bhutan; Sri Lanka; Thailand; Indonesia; Philippines; Taiwan; Japan; Australia; New Zealand; N America; England; Fiji; etc. [31, 69, 252].

5.9.4.2. Habitat

Moist exposed grassy areas.

5.9.4.3. Ethnomedicine

It is used for checking of nose bleeding [84]. It has been used as a detoxifying agent and found effective against hepatitis [255, 256].

5.9.4.4. Phytochemistry

Ophioglonin, ophioglonin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, ophioglonol, ophioglonol prenyl ether, ophioglonol 4′-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, isoophioglonin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, quercetin, luteolin, kaempferol, 3,5,7,3′,4′-pentahydroxy-8-prenylflavone, and quercetin 3-O-methyl ether are isolated from the whole plant [256].

5.9.5. Ophioglossum reticulatum

5.9.5.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Fujian, Gansu, Guizhou, Henan, Hubei, Jiangxi, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Xizang and Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Pakistan; Bhutan; Sri Lanka; Philippines; Korea; S America; Madagascar; Africa; etc. [31, 69, 252].

5.9.5.2. Habitat

Roadsides, under beneath of tree in the forests and grassy plateaus.

5.9.5.3. Ethnomedicine

It is used as cooling agent in burns, tonic and wounds remedy [230]. Fronds are used as styptic in contusions and haemorrages [163]. Leaf extract is vulnerary [124]. Leaf juice is useful against heart spasms [257]. Rhizome decoction is used in boils and the extract is used as an antidote in snake bite.

5.9.6. Ophioglossum vulgatum

5.9.6.1. Distribution

Nepal; Anhui, Fujian, Guangdong, Guizhou, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, S Shaanxi, Sichuan, Xizang, Yunnan and Zhejiang; India; Sri Lanka; Korea; Japan; Australia, N America; Europe; etc. [69].

5.9.6.2. Habitat

Naturally grow in damp grasslands and semi-evergreen forests, particularly after fire [258].

5.9.6.3. Ethnomedicine

It possesses detergent, antiseptic, styptic and vulnerary properties [259]. Rhizome is used to treat boils. Pulverized rhizome is externally applied to sores, burns and wounds [135]. Decoction is useful in heart diseases [134]. It is useful in clearing heat, detoxifying toxins, activating blood circulation, treating hepatitis and pneumonia, etc. [260].

5.9.6.4. Pharmacognosy

O. vulgatum exhibits wound healing [261, 262], antidiarrheal [263] and antiviral [264] properties.

5.9.6.5. Phytochemistry

The whole plant material constitutes total flavonoid and total polyphenols in 2.7 and 1.5%, respectively [263]. Flavonoids, glycerides and amino acids are the constituents in O. vulgatum [265]. From the aerial parts, 3-O-methylquercetin 7-O-diglycoside 4′-O-glycoside, quercetin-3-O-[(6-caffeoyl)-β-glucopyranosyl(1→3) α-rhamnopyranoside]-7-O-α-rhamnopyranoside, kaempferol-3-O-[(6-caffeoyl)-β-glucopyranosyl (1→3) α-rhamnopyranoside]-7-O-α-rhamnopyranoside and quercetin-3-O-methyl ether have been isolated [261, 266].

5.10. Osmundaceae

5.10.1. Osmunda claytoniana [Osmunda claytoniana subsp. Vestita]

5.10.1.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Chongqing, Guizhou, Hubei, Hunan, Liaoning, Sichuan, Taiwan, Xizang and Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Pakistan; Bhutan; Korea; Japan; E Russia; N America; etc. [31, 69].

5.10.1.2. Habitat

At high altitude above in meadows, moist and shady forest area.

5.10.1.3. Ethnomedicine

Plant paste is applied on wounds externally [134]. The rhizome and stipe bases are used for adulteration as a substitute of Filix-mas for vermifuge effect and flavor [267].

5.10.1.4. Pharmacognosy

α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity [268] and antitrypanosomal activity [269] of the plant extracts are evaluated.

5.10.1.5. Phytochemistry

The plant material consists of phenolics, tannins, flavonoids, saponins, terpoenoids, etc. [91].

5.11. Pteridaceae

5.11.1. Ceratopteris thalictroides

5.11.1.1. Distribution

W and C Nepal; Anhui, Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou (Liping), Hainan, Hubei, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Shandong, Sichuan, Yunnan and Zhejiang; Assam, W Bengal, Bihar, Uttarakhand, Himachal and C India; Sri Lanka; Myanmar; Thailand; Vietnam; Malaysia; Indonesia; Philippines; Taiwan; Japan; New Guinea; Australia; C, N and S America; Madagascar; Pacific islands; West Indies; Africa; etc. [31, 69].

5.11.1.2. Habitat

Marshy areas.

5.11.1.3. Ethnomedicine

The fronds are used as a poultice for skin problems [163, 270, 271]. It's paste with turmeric is applied in cuts and wounds. It is also used as a tonic and styptic [272], and it is also reported to be toxic [163].

5.11.1.4. Pharmacognosy

The plant extracts possess antibacterial [273], anti-inflammatory [274], antioxidative [275] and antidiabetic activities [276].

5.11.1.5. Phytochemistry

The leaves contain protein (13.4%), carbohydrate (54.3%), fat (3.2%), vitamin C (6.1 mg/100 g) and minerals (eg. Na, K, P, Mg, Ca, Mn, Fe, Zn and Cu) [277]. The plant materials showed the presence of alkaloids, steroids, coumarins, tannins, saponins, flavonoids, quinones, anthroquinones, phenols, proteins, xanthoproteins, carbohydrates, glycosides, catachins, sugars and terpenoids [270, 277]. 2-Nitroethyl benzene, γ-sitosterol, n-hexadecanoic acid and linalool are the major phytochemicals present in the leaves.

5.11.2. Pteris biaurita [Pteris flavicaulis]

5.11.2.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Guangdong, Guangxi (Baise), Guizhou, Hainan, Xizang and Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling and Uttarakhand; Bhutan; Bangladesh; Sri Lanka; Thailand; Laos; Malaysia; Indonesia; Philippines; C and S Taiwan; etc. [31, 69].

5.11.2.2. Habitat

Moist, shady and exposed areas, and roadsides.

5.11.2.3. Ethnomedicine

The rhizome and frond decoction is used to treat chronic disorders [278]. To relieve body pain, the rhizome paste is applied [279]. Frond juice and paste are applied on cuts and bruises [53, 280].

5.11.2.4. Pharmacognosy

The leaves exhibit antimicrobial activity [281]. The fronds are evaluated for the antioxidant activity [278].

5.11.2.5. Phytochemistry

Fronds constitute alkaloids (16.4 mg/g), phenolics (13.2 mg/g), saponins (11.1 mg/g), tannins (6.2 mg/g), flavonoids (17.5 mg/g) as well as steroids, triterpenoids, anthraquinones, amino acids and sugars [282]. Leaves contain flavonoids (14.5 mg/g), total phenol (10.4 mg/g), ascorbate (1.6 mg/g), α-tocophenol (0.9 mg/g) and total sugars (125 mg/g) [278]. Total protein (110.5 mg/g), total chlorophyll (0.9 mg/g) and carotenoids (62.3 μg/g) in the fresh material are also estimated. Eicosenes and heptadecanes present in the leaves are attributed for the antimicrobial activity [281].

5.11.3. Pteris vittata

5.11.3.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Anhui, Fujian, SE Gansu (Kangxian), Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, SW Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Xizang, Yunnan and Zhejiang; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling and Uttarakhand; Bhutan; Taiwan; etc. [31, 69]. It is commonly known as brake fern.

5.11.3.2. Habitat

Moist and shady areas, roadsides and tropical semi-evergreen forests.

5.11.3.3. Ethnomedicine

It is a poisonous plant and therefore it is planted on village borders to keep enemies away [283]. It is used in tongue sores, burns and glandular swellings and for population control [136, 220, 279]. Herb juice is used for treating dysentery and diarrhea [284]. Young fronds are used in manuring [134]. Plants are used as fodder and thatching [52].

5.11.3.4. Pharmacognosy

It's antibacterial property is explored [285, 286]. It has been reported that P. vittata hyperaccumulates arsenic [287, 288].

5.11.3.5. Phytochemistry

Leaves contain leucocyanidin, leucodelphinidin, apigenin 7-O-p-hydroxybenzoate, leutolin, kaempherol, quercetin, rutin, etc. [285, 289, 290].

5.12. Tectariaceae

5.12.1. Tectaria gemmifera [Tectaria coadunata; Tectaria macrodonta]

5.12.1.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Sichuan, Xizang and Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Bhutan; Sri Lanka; Myanmar; Thailand; Laos; Vietnam; Malaysia; Taiwan; Madagascar; Africa; etc. [31, 69].

5.12.1.2. Habitat

North-west facing moist and rocky slopes, exposed areas and roadsides or in rock crevices near water channels.

5.12.1.3. Ethnomedicine

Rhizome decoction is given to treat stomachache and gastrointestinal disorders [291]. Root juice is used to treat diarrhea and dysentery [142]. Leaf decoction is given to treat asthma and bronchitis [253]. Leaf paste is applied in stings of honeybee, centipeds, etc. Whole plant is used in eczema, scabies and jaundice [254, 292]. Leaves are used as fodder [134].

5.12.1.4. Pharmacognosy

Antibacterial [293, 294, 295, 296], antioxidant [295, 297, 298] and antidiabetic [299] activities are reported. Cholinesterases and tyrosinase inhibitory activities together with cytotoxic effect on the 2008 and BxPC3 cell lines of the plant extract from twigs and rhizomes are reported [297].

5.12.1.5. Phytochemistry

Crude fat (0.2%), fiber (2.3%), protein (12.1%), vitamin C (22.2 mg/100 g), mineral contents (Ca, Cu, Fe, Mg, Mn, Na and Zn), heavy metals (Al, As, Cd, Hg, Li, Ni and Pb), etc. are determined in T. gemmifera [27]. The fronds constituted of anthraquinones, coumarins, flavonoids, steroids, alkaloids, tannins, phenolics, etc. [296, 300], and the rhizomes constitutes alkaloids, coumarins, phenolics, flavonoids, quinones, etc. [294, 296, 301]. GC-MS analysis of the methanolic extract of leaves show the presence of palmitic acid, methyl palmitate, phytol, etc. as the major constituents [295], while the rhizome constitutes fatty acids [295, 302]. The qualitative and quantitative analyses reveal that the twig and rhizome contain a large amount of procyanidins as well as eriodictyol-7-O-glucuronide and luteolin-7-O-glucoronide [297].

5.12.2. Tectaria zeylanica [Osmunda zeylanica]

5.12.2.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan and Yunnan; S India; Sri Lanka; Thailand; Laos; Vietnam; Malaysia; Indonesia; Philippines; Taiwan; Indian Ocean islands (Mauritius); Pacific islands (Polynesia); etc. [69].

5.12.2.2. Habitat

Muddy rocks in forests, near streams and on steep banks.

5.12.2.3. Pharmacognosy

Ethanolic extract of the leaves shows antioxidant activity by scavenging DPPH free radical with the IC50 value of 0.78 mg/mL [303].

5.12.2.4. Phytochemistry

Leaf constitutes alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids, tannins, etc. [303]. Fronds constitute phenolics, saponins, steroids, tannins, coumarins, etc. [304].

5.13. Thelypteridaceae

5.13.1. Thelypteris auriculata [Cyclosorus auriculata]

5.13.1.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Guangxi, Guizhou, Xizang and Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand and Himachal; Bhutan; Sri Lanka; Thailand; Vietnam; etc. [31, 69].

5.13.1.2. Habitat

Along river banks and forest margins.

5.13.2. Thelypteris nudata [Thelypteris multilineata; Pronephrium nudatum]

5.13.2.1. Distribution

W, C and E Nepal; Guizhou, Xizang and Yunnan; Arunachal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, Uttarakhand, Himachal, Jammu and Kashmir; Bhutan; Indonesia; Vietnam; etc. [31, 69].

5.13.2.2. Habitat

Shaded sparse forests on slopes.

5.13.2.3. Pharmacognosy

The frond extract exhibits synergistic antibacterial effect against methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [305].

6. Altitudinal zones-based categorization of Nepalese wild edible ferns

The distribution of ferns is varied with different altitudinal zones. Nepal is particularly considered to be divisible into three altitudinal zones, namely, (a) Tarai (plain area), (b) Pahad (hilly area) and (c) Himal (mountainous area). Accordingly, based on the species found at different altitudes, the Nepalese wild edible vegetable ferns can be categorized into three:

6.1. Lower altitude species (60−1,200 m asl)

The species grown in low-lands, i.e. Tarai, Siwalik and Chure areas of Nepal, include: A. strigillosum, D. boryana, D. esculentum, S. palustris, W. unigemmata, C. spinulosa, P. revolutum, D. maximum, D. splendens, D. cochleata, L. flexuosum, L. japonicum, N. cordifolia, B. lanuginosum, H. zeylanica, O. petiolatum, O. reticulatum, C. thalictroides, P. biaurita, P. vittata, T. gemmifera and T. zeylanica.

6.2. Mid-hills species (1,200−2,500 m asl)

The species grown in mid-lands, i.e. Chure and Mahabharat areas of Nepal, include: A. atkinsonii, A. strigillosum, D. boryana, D. esculentum, D. kawakamii, D. spectabile, D. stoliczkae, W. unigemmata, C. spinulosa, P. revolutum, D. maximum, D. cochleata, P. squarrosum, M. quadrifolia, L. japonicum, N. cordifolia, B. lanuginosum, B. lanuginosum, H. zeylanica, O. nudicaule, O. petiolatum, O. reticulatum, O. vulgatum, O. claytoniana, P. biaurita, P. vittata, T. gemmifera, T. auriculata and T. multilineata.

6.3. High altitude species (2,500−4,000 m asl)

The species grown in upper-lands, i.e. Himalayas or mountainous areas of Nepal, include: D. boryana, D. spectabile, D. stoliczkae, P. squarrosum, L. japonicum, W. unigemmata, P. revolutum, B. lanuginosum, O. nudicaule, O. petiolatum, O. reticulatum, O. vulgatum and O. claytoniana.

7. Inhabitations-based distribution of Nepalese wild edible ferns

Virtually, the ferns are inhabitated where flowering plants are found [32]. Humid, moist and shady forests are more suitable for their growth. Based on the species found at different ecological habitats, the edible vegetable ferns of Nepal are categorized into epiphytes, lithohytes, terrestrials, climbers and hydrophytes as given below. Noteworthly, some species could be found in more than one habitat.

7.1. Epiphytes

These species grow on bases, trunks and branches of trees, and are covered with mosses and liverworts. Rainy season, hill-side evergreen forest and moist forest are more suitable for their growth. In middle elevation, altitude up to 2,000 m, the distribution of ephiphytes is very few. Examples of epiphytes are: N. cordifolia, B. lanuginosum and P. vittata.

7.2. Lithophytes

These species grow in rock crevices; humus rich rocks in shady areas; moist, shaded and exposed forests; crevices of brick walls; and muddy rocks in streamlets. Examples of lithophytes are: W. unigemmata, D. cochleata, N. cordifolia, B. lanuginosum, P. biaurita, P. vittata and T. gemmifera.

7.3. Terrestrials

They grow in evergreen and semi-evergreen forests that enriched with humus and organic nutrients. They also grow in shady areas, stream banks, moist hill slopes and shaded roadsides. Examples of terrestrial species are: A. strigillosum, D. boryana, D. esculentum, D. maximum, D. stoliczkae, W. unigemmata, C. spinulosa, P. revolutum, D. cochleata, D. splendens, P. squarrosum, N. cordifolia, B. lanuginosum, H. zeylanica, O. nudicaule, O. petiolatum, O. reticulatum, O. claytoniana, P. biaurita, P. vittata, T. gemmifera, T. zeylanica and T. nudata.

7.4. Climbers

They grow on rich humus soil. They climb other trees growing inside shaded forests, forerst edges and tropical areas. Examples of climber species include: S. palustris, L. flexuosum and L. japonicum.

7.5. Hydrophytes

They are water loving species. They occur on wet or marshy border of ponds, lakes and waterfalls. They also occur in paddy fields. Examples of hydrophytes include: M. quadrifolia and C. thalictroides.

8. Medicinal ailments categorization of Nepalese wild edible ferns

Based on pharmacognosy of the plant extracts of ferns and fern-allies reported by several authors, the medicinal ailments categorization of Nepalese wild edible vegetable food ferns is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the medicinal ailments of the vegetable food ferns.

| SN | Medicinal ailments | Ferns | Parts used | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Antibacterial | D. esculentum | Rhizome, leaf | [96, 98, 99, 100] |

| S. palustris | Frond | [128] | ||

| W. unigemmata | Aerial part | [138] | ||

| D. cochleata | Leaf, rhizome | [165, 167] | ||

| L. flexuosum | Frond, whole plant | [178, 179] | ||

| M. quadrifolia | Stem, leaf, aerial part | [196, 198, 199, 200] | ||

| N. cordifolia | Frond | [99, 222] | ||

| H. zeylanica | Rhizome | [245] | ||

| O. vulgatum | Frond, leaf and stem | [261, 262] | ||

| C. thalictroides | Leaf | [273] | ||

| P. vittata | Frond | [285, 286] | ||

| T. gemmifera | Rhizome, leaf, frond | [293, 294, 295, 296] | ||

| 2 | Antiviral | W. unigemmata | Rhizome | [139, 140] |

| O. vulgatum | Not specified | [264] | ||

| 3 | Antifungal | S. palustris | Frond | [127] |

| P. squarrosum | Leaf | [169] | ||

| M. quadrifolia | Whole part | [201] | ||

| N. cordifolia | Frond | [222] | ||

| P. biaurita | Leaf | [281] | ||

| 4 | Antimalarial | S. palustris | Leaf | [132] |

| 5 | Antidiarrheal | M. quadrifolia | Aerial part | [194] |

| O. vulgatum | Whole part | [263] | ||

| 6 | Anthelmintic | D. esculentum | Rhizome | [107] |

| N. cordifolia | Leaf | [224] | ||

| 7 | Analgesic and anti-inflammatory | D. esculentum | Leaf | [99, 106] |

| M. quadrifolia | Aerial part, leaf | [194, 202] | ||

| H. zeylanica | Rhizome | [238, 239, 240] | ||

| C. thalictroides | Spore | [274] | ||

| 8 | Antidiabetic | D. esculentum | Leaf | [103] |

| M. quadrifolia | Aerial part | [205] | ||

| H. zeylanica | Rhizome | [244] | ||

| O. claytoniana | Frond, rhizome | [268] | ||

| C. thalictroides | Whole part | [276] | ||

| T. gemmifera | Frond, rhizome | [299, 301] | ||

| 9 | Antioxidant and anticancer | D. boryana | Aerial part | [92, 94] |

| D. esculentum | Leaf | [101, 102, 103, 104, 105] | ||

| D. maximum | Frond | [121] | ||

| S. palustris | Frond | [129, 130, 131] | ||

| W. unigemmata | Aerial part | [137, 138] | ||

| C. spinulosa | Leaf | [144] | ||

| D. cochleata | Leaf | [166] | ||

| P. squarrosum | Leaf | [165] | ||

| M. quadrifolia | Aerial part, leaf | [203, 204, 211] | ||

| N. cordifolia | Fruit, leaf | [223] | ||

| H. zeylanica | Rhizome | [242, 243] | ||

| C. thalictroides | Frond | [275] | ||

| P. biaurita | Frond | [278] | ||

| T. gemmifera | Rhizome, leaf, twig | [295, 297, 298] | ||

| T. zeylanica | Leaf | [303] | ||

| 10 | Neuroprotective | D. esculentum | Leaf | [104] |

| C. spinulosa | Leaf | [144] | ||

| L. japonicum | Spore | [186] | ||

| M. quadrifolia | Whole plant, leaf | [206, 207, 208, 209] | ||

| 11 | Nephroprotective | M. quadrifolia | Leaf | [210] |

| N. cordifolia | Rhizome | [225] | ||

| 12 | Hepatoprotective | D. esculentum | Leaf | [103] |

| L. flexuosum | Whole plant | [176, 177] | ||

| H. zeylanica | Rhizome | [236, 237] | ||

| 13 | Antifertility | L. flexuosum | Not specified | [174, 175] |

9. Important phytochemicals present in the wild edible ferns

The major bioactive compounds present in the ferns and fern-allies are flavonoids, terpenoids, steroids and alkaloids.

9.1. Flavonoids

The total flavonoid content has been reported in the edible parts of some ferns, for examples, 145.8 mg/g in D. boryana (arial parts) [94], 110.8 mg quercetin equivalent/100 g in D. esculentum (arial parts) [109], 151 mg quercetin equivalent/g in W. unigemmata (arial parts) [138], 3.5 mg/g in M. quadrifolia (arial parts) [212], 7.5 mg/g in M. quadrifolia (leaves) [214], 6.4 mg/g M. quadrifolia (stems) [214], 27.4 mg/g in O. vulgatum (whole plant) [263], 17.5 mg/g in P. biaurita (fronds) [282], 14.5 mg/g in P. biaurita (leaves) [278], etc. A higher total flavonoid content in the plant material is usually correlated with a more antioxidant capacity and thus potentially anticarcinogenic [306, 307].

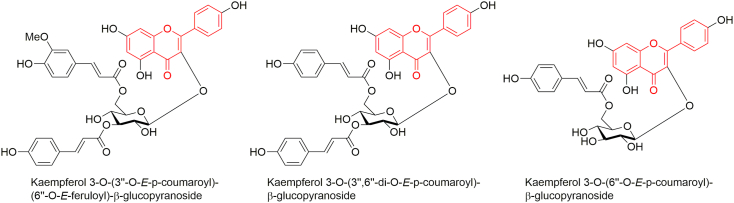

Several flavonoid glycosides have been reported from the leaves [128] and fronds of S. palustris [126] (Figure 2). The isolated flavonoids viz. kaempferol 3-O-(3″-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-(6″-O-E-feruloyl)-β-glucopyranoside and kaempferol 3-O-(3″,6″-di-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-glucopyranoside moderately inhibit butyrylcholieserase (BChE) with IC50 values of 113.66 and 85.37 μM, respectively [126]; and kaempferol 3-O-(6″-O-E-p-coumaroyl)-β-glucopyranoside strongly inhibits acetylcholinesterase (AChE) with IC50 value of 23.5 μM [308] exhibiting potentiality against Alzheimer's disease.

Figure 2.

Some flavonoids isolated from S. palustris.

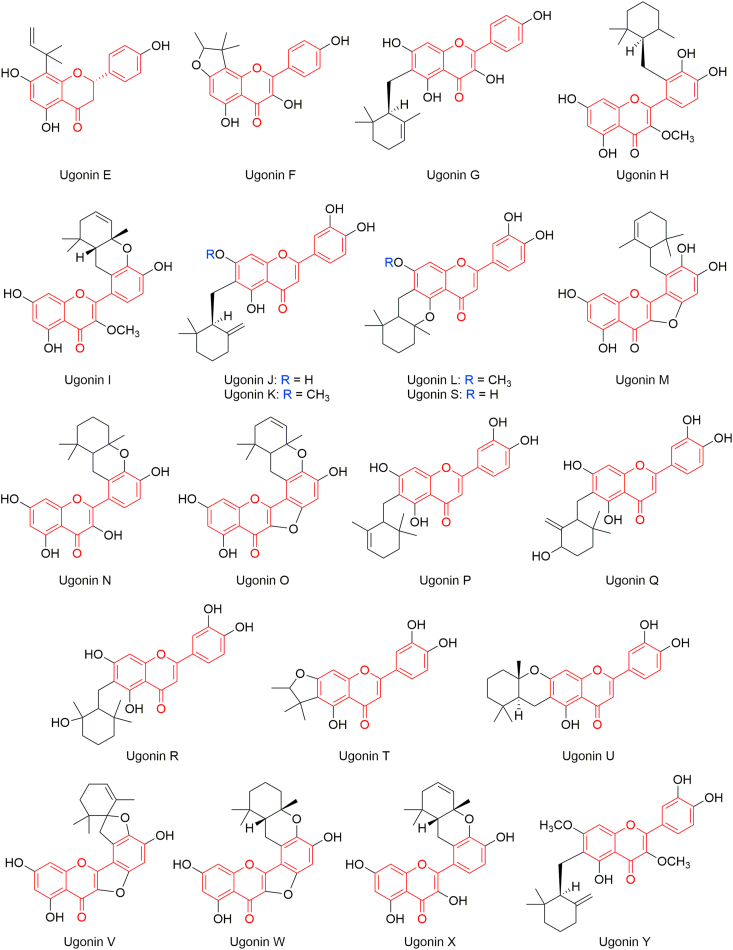

Huang et al. reported isolation of several flavonoids (ugonins E–Y) from the rhizomes of H. zeylanica [235, 246, 247, 248] (Figure 3). Ugonins J‒L are found more active than trolox, with IC20 values of 5.29 ± 0.32, 7.23 ± 0.22 and 7.93 ± 0.31 μM, respectively, in antioxidative activity using the DPPH assay; ugonins L,M,O,Q,S and T are found anti-inflammatory; and ugonin K is found antiosteoporosis. Ugonins J,K,L,M,S and U possess antidiabetic activity by inhibiting α-glucosidase [309, 310]. Ugonin J is found effective in inhibition of neointima formation [311]. Being a novel viral protease inhibitor, ugonin J inhibits severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) 3CLpro activity and hence is therapeutically potential for SARS-CoV-2 infection [312]. Ugonin K induces apoptosis [313]. Neuroprotective [314] and osteogenesis [315] effects of ugonin K are reported. Ugonin M is considerably potential to develop hepatoprotective and anti-inflammatory natural agents [316]. Ugonin U shows immunomodulatory effect in human neutrophils via stimulation of phospholipase C [317], and induces Ca2+ mobilization and eventually activates the NLRP3 inflammasome [318].

Figure 3.

Ugonins isolated from H. zeylanica rhizomes.

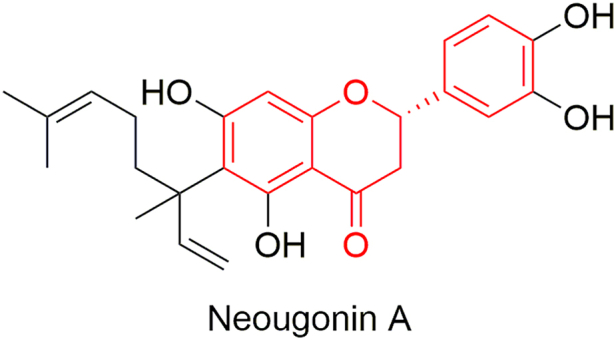

From the whole plant of H. zeylanica, Su et al. have isolated several prenylated flavonoids [251]. Among them, neougonin A (Figure 4) inhibited NO production in lipopolysaccharide-treated RAW264.7 cells with an IC50 value of 3.32 μM, and it displayed a moderate cytotoxicity with IC50 value of 16.13 μM in the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay.

Figure 4.

Neougonin A isolated from H. zeylanica.

9.2. Terpenoids

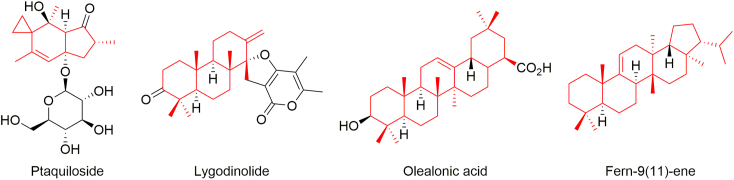

Ptaquiloside (Figure 5) is one of the main hazardous metabolites found in the fern that is considered to be responsible for the toxicological problems to ruminant and non-ruminant animals, and then to human alike through the milk and meat [150]. The amounts of ptaquiloside have been estimated in P. revolutum, D. cochleata and P. squarrosum (leaves) that collected from different parts of India [108]. P. revolutum is considered as carcinogenic [152]. It has been demonstrated that feeding of bracken fern induces urinary bladder tumors, illeum sarcomas, pulmonary adenomas and leukemia [153]. On the other hand, Yoshihira et al. have isolated several sesquiterpens, namely, pterosins A‒G, J‒L, N, O, Z, pterosides A‒C, etc., from the fronds of Japanese bracken fern and performed cytotoxicity test (Table 3) [154]. They have mentioned that although these indanonone derivatives showed some cytotoxicity to HeLa cells; however, none of them could induce tumors under the conditions studied.

Figure 5.

Some bioactive terpenoids obtained from food ferns.

Table 3.

Cytotoxicity (HeLa Cell) of pterosins and pterosides isolated from Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | Cytotoxicity IC50 (μg/mL) |

| Pterosin A | ‒CH2OH | ‒CH3 | H | ‒CH2OH | 320 |

| Pterosin B | ‒CH3 | H | H | ‒CH2OH | 100 |

| Pterosin C | H | ‒CH3 | ‒OH | ‒CH2OH | 320 |

| Pterosin D | ‒CH3 | ‒CH3 | ‒OH | ‒CH2OH | >320 |

| Pterosin E | ‒CH3 | H | H | ‒CO2H | 30 |

| Pterosin F | ‒CH3 | H | H | ‒CH2Cl | 65 |

| Pterosin G | ‒CH2OH | H | H | ‒CH2OH | 180 |

| Pterosin J | H | ‒CH3 | ‒OH | ‒CH2Cl | >100 |

| Pterosin K | ‒CH2OH | ‒CH3 | H | ‒CH2Cl | >100 |

| Pterosin L | ‒CH2OH | ‒CH3 | ‒OH | ‒CH2OH | >100 |

| Pterosin N | ‒CH3 | ‒OH | H | ‒CH2OH | 180 |

| Pterosin O | ‒CH3 | H | H | ‒CH2OCH3 | 30 |

| Pterosin Z | ‒CH3 | ‒CH3 | H | ‒CH2OH | 10 |

| Pteroside A | ‒CH2OH | ‒CH3 | H | ‒CH2O glucose | >320 |

| Pteroside B | ‒CH3 | H | H | ‒CH2O glucose | >100 |

| Pteroside C | H | ‒CH3 | ‒OH | ‒CH2O glucose | >320 |

Lygodinolide (Figure 5), present as major constituent in L. flexuosum, is attributed for the wound healing property [[181], [182]].

From N. cordifolia, oleanolic acid and fern-9(11)-ene have been isolated (Figure 5) [229]. Fern-9(11)-ene has also been isolated from C. spinulosa leaves [146]. Oleanolic acid shows antimicrobial activity against vancomycin resistant enterococci, Streptococcus pneumoniae and MRSA [319]. It is also found to exhibit anticancer activity [320]. Fern-9(11)-ene is found to be susceptible against Salmonella typhi and Pseudomona aeruginosa [321].

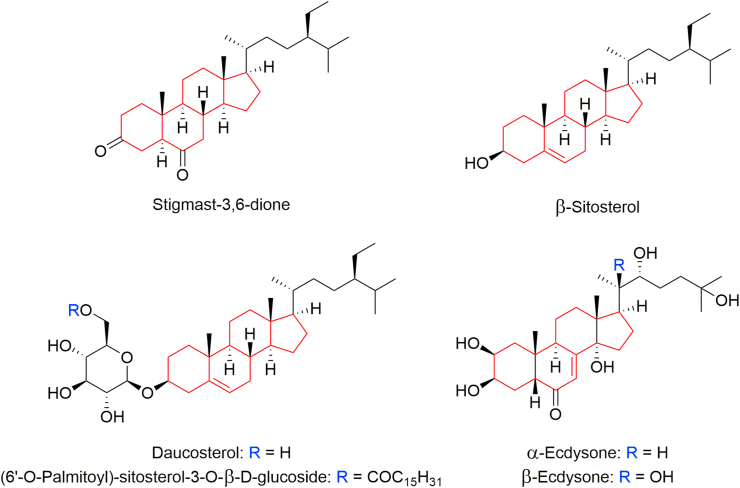

9.3. Steroids

Stigmast-3,6-dione, β-sitosterol and daucosterol in the leaves and stalks of C. spinulosa [147, 148, 149]; α- and β-ecdysones in the arial parts of P. revolutum [161]; and daucosterol, β-sitosterol, (6′-O-palmitoyl)-sitosterol-3-O-β-D-glucoside in B. lanuginosum [231] are some examples of alkaloids present in different edible parts of the ferns and fern-allies (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Steroids found in food ferns.

9.4. Alkaloids

Total alkaloids of 6.1 mg/g in M. quadrifolia (leaves) [214], 5.9 mg/g M. quadrifolia (stems) [214], 0.1 mg/g in N. cordifolia (leaves) [227] and 16.4 mg/g in P. biaurita (fronds) [282] are reported.

10. Conclusion

Taxonomic and ethnobotanical studies on the ferns of Nepal are exploited; however, chemical and biological investigations on Nepalese ferns and fern-allies are limited. This review primarily briefs historical background on expeditious journey on Nepalese pteridophytes, updates number of ferns consumed as vegetables by Nepalese, outlines their ethnomedicinal uses, and compiles information on their pharmacognosy, pharmacology and phytochemistry that reported from elsewhere. In Nepal, some species of ferns that primarily collected from nearby forests are sold in the markets. Some species are consumed by rural Nepalese as the last option of food and there is no proper information transformation to the next generation about ferns as food materials and their potential medicinal values. C. decurrenti-alata, M. intermedia, B. orientale, O. japonica, C. intermedia and P. wallichiana are available in Nepal, but there is no precedented report for their consumption by Nepalese; however, they are consumed in China. The traditional ethnopharmacological knowledge on ferns and fern-allies is neglected both by locals and scientific community.

11. Future recommendation

Most of the ferns and fern-allies, collected for vegetable food by Nepalese, grow in their natural habitat. Lack of sharing of traditional ethnomedicinal knowledge to new generation and unsustainable collection practice making them vulnerable. Only in the recent past, a very few species bearing economical value are agricultured in local farms. From the literature evidences, we believe that investigations on unfocused ferns can provide new research opportunities and potent bioactive phytochemicals.