Abstract

Background & Aims

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is used for the diagnosis and follow-up of individuals with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). The aim of our study is to develop an MRCP-score based on cholangiographic findings previously associated with outcomes and assess its reproducibility and prognostic value in PSC.

Methods

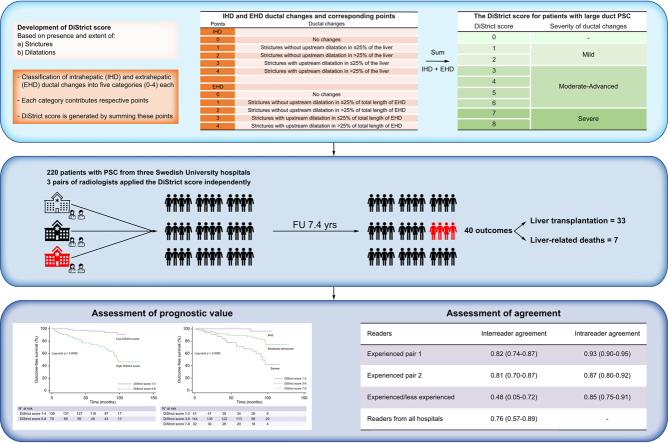

The score (DiStrict score) was developed based on the extent and severity of cholangiographic changes of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts (range 0–8) on 3D-MRCP. In this retrospective, multicentre study, three pairs of radiologists with different levels of expertise from three tertiary centres applied the score independently. MRCP examinations of 220 consecutive individuals with PSC from a prospectively collected PSC-cohort, with median follow-up of 7.4 years, were reviewed. Inter-reader and intrareader agreements were assessed via intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). After consensus, the prognostic value of the score was assessed using Cox-regression and outcome-free survival rates were assessed via Kaplan-Meier estimates. Harrell's C-statistic was calculated.

Results

Forty patients developed outcomes (liver transplantation or liver-related death). Inter-reader agreement between experienced radiologists was good (ICC 0.82; 95% CI 0.74–0.87, and ICC 0.81; 95% CI 0.70–0.87, respectively) and better than the agreement for the pair of experienced/less-experienced radiologists (ICC 0.48; 95% CI 0.05–0.72). Agreement between radiologists from the three centres was good (ICC 0.76; 95% CI 0.57–0.89). Intrareader agreement was good to excellent (ICC 0.85–0.93). Harrell's C was 0.78. Patients with a DiStrict score of 5–8 had 8.2-fold higher risk (hazard ratio 8.2; 95% CI 2.97–22.65) of developing outcomes, and significantly worse survival (p <0.001), compared to those with a DiStrict score of 1–4.

Conclusions

The novel DiStrict score is reproducible and strongly associated with outcomes, indicating its prognostic value for individuals with PSC in clinical practice.

Impact and implications

The diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is based on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). However, the role of MRCP in the prognostication of PSC is still unclear. We developed a novel, simple, and reproducible risk-score, based on MRCP findings, that showed a strong association with prognosis in individuals with PSC (DiStrict score). This score can be easily used in clinical practice and thus has the potential to be useful in clinical trials and in patient counselling and management.

Keywords: Cholangitis sclerosing, Cholangiopancreatography, Magnetic resonance, Bile ducts, Prognosis

Abbreviations: CBD, common bile duct; CHD, common hepatic duct; EHD, extrahepatic ducts; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; HR, hazard ratio; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; IHD, intrahepatic ducts; LHD, left hepatic duct; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; RHD, right hepatic duct

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

We developed a novel MRCP-score (DiStrict score) for large-duct PSC based on MRCP-findings.

-

•

The DiStrict score is based on presence and extent of biliary strictures and dilatations.

-

•

The DiStrict score can predict liver transplantation and liver-related death.

-

•

Individuals with high DiStrict scores have worse survival.

-

•

The District score is easy to apply and reproducible.

Introduction

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is the diagnostic imaging test of choice for primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). PSC is characterised by progressive biliary destruction, often leading to biliary cirrhosis, liver failure, and the need for liver transplantation. The disease can be complicated by hepatobiliary cancer, mainly cholangiocarcinoma, and estimated transplant-free survival is between 13 and 20 years.[1], [2], [3], [4] Prognostication of the disease is challenging due to disease heterogeneity and insufficient biomarkers. In addition to diagnosis, MRCP is used as a follow-up modality in many expert centres.[5], [6], [7]

The broad use of MRCP for PSC diagnosis and management has led to an increasing interest in the potential prognostic value of MRCP findings. However, this is hampered by the low agreement between readers regarding the interpretation of imaging findings of examinations of PSC patients.[8], [9], [10] Earlier studies, utilising both MRI/MRCP and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), used mainly two ERCP-based classifications for the evaluation of PSC cholangiographic findings, one proposed by Craig from the Mayo clinic11 and one from Majoie and the Amsterdam group.12 Craig's classification has been adopted, fully or partially, by other studies,13 including the recently developed ANALI scores.14 The reproducibility of the Craig and Majoie classifications in adult PSC is not known, and direct application of ERCP findings to MRCP is problematic. Results regarding which cholangiographic findings are significant for prognosis vary, but the extent and grade of intrahepatic strictures, together with dilatation of the intrahepatic ducts are features that have been associated with clinically important outcomes.11,13,14 The extent of ductal changes is a finding that can be easily assessed using MRI/MRCP; however, its reproducibility has not been evaluated. On the contrary, evaluation of stricture grade can be difficult to evaluate on MRCP (especially if the ducts are not dilated), due to resolution restrictions of this imaging technique (1 × 1 × 1 mm) and artifacts from vessels, air, and bile duct stones that can produce signal voids in the ducts, mimicking high-grade strictures.15,16 Furthermore, evaluation of the grade of a stricture can be problematic, especially at ductal branching points. Instead of stricture grade, dilatation upstream of a stricture may reflect the severity of a stricture more appropriately, by indicating the obstruction of bile flow caused by the stricture. This may also be more clinically relevant since it has been shown to cause liver damage.17 Regarding reproducibility, a study of the ANALI scores demonstrated that, although the inter-reader agreement was unsatisfactory, dilatation of intrahepatic ducts (the only cholangiographic feature included in these scores), was the most reproducible parameter.9

The aim of our study is to develop an MRCP-score based on cholangiographic findings that have previously been associated with outcomes and assess its reproducibility and prognostic value in PSC.

Materials and methods

Study population

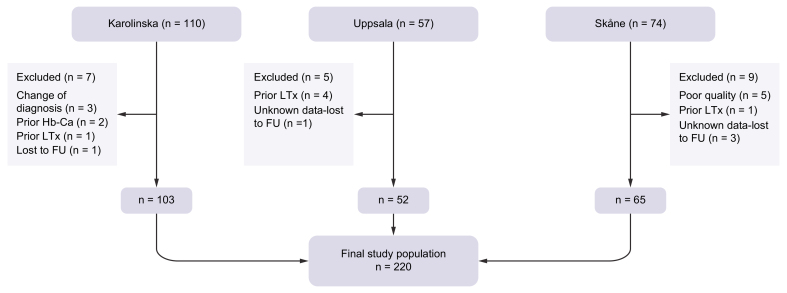

Patients from three Swedish university hospitals were included. All participants were recruited from a national, multicentre, prospective, observational cohort study for individuals with PSC.18 Participants had undergone annual liver MRI/MRCP for surveillance purposes, along with clinical and laboratory evaluations. Diagnosis of PSC was based on guidelines from the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.5,6 Inclusion criteria for the present study included diagnosis of large-duct PSC, available MRCP, and follow-up data. Exclusion criteria were a history of hepatobiliary malignancy or previous liver transplantation, and insufficient MCRP quality. 110 consecutive patients, starting from the first patient enrolled in the study, were recruited from Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm, 57 patients from Uppsala University Hospital, and 74 patients from Skåne University Hospital. After exclusion, the final cohort comprised 220 participants, included from April 2011 and followed up until December 2021. A flowchart of the study population is provided in Fig. 1. Demographic, laboratory, and outcome data were collected and are presented in Table 1. MRCP examinations closest to inclusion in the observational study were retrieved for evaluation.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study population.

FU, follow-up; Hb-Ca, hepatobiliary cancer; LTx, liver transplantation.

Table 1.

Demographic and laboratory data of study population.

| Study population | Normal range | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 220 | — |

| Stockholm | 103 | — |

| Skåne | 65 | — |

| Uppsala | 52 | — |

| Male/Female | 148/72 | — |

| Age in years (at MRI date) | 47 (18–76) | — |

| Time from PSC diagnosis to MRI (years) | 7.7 (0–34) | — |

| IBD, n (%) | 186 (85) | — |

| Ulcerative colitis | 135 (61) | — |

| Crohn's disease | 40 (18) | — |

| Indeterminate colitis | 11 (5) | — |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 11 (2–104) | <26 |

| ALT (μkat/L) | 0.79 (0.1–10.4) | <1.1 |

| AST (μkat/L) | 0.65 (0.21–8.5) | <0.76 |

| GGT (μkat/L) | 2.2 (0.1–59) | <1.4 |

| ALP (μkat/L) | 2.4 (0.6–19) | 0.7–1.9 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 39 (5.1–51) | 36-48 |

| INR | 1 (0.8–3.3) | <1.3 |

| CA 19-9 (kE/L) | 9.3 (0.55–1,056) | <34 |

| MELD score | 6 (6–14) | — |

| Follow-up time from MRI (years) | 7.4 (0.3–10.6) | — |

| Clinical events at follow-up | ||

| Liver transplantation | 33 | — |

| Liver-related death | 7 | — |

| Hepatobiliary cancer | 7 | — |

| Other causes of death | 6 |

All values expressed as medians (range).

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate transaminase; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; INR, international normalized ratio; Liver Tx, liver transplantation; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

The study was approved by the institutional review board, Dnr: 2011/824-31/2, 2018/1111-32, and 2018/1494-31/3. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Sample size estimation

To ensure sufficient power, we performed sample size calculations for comparison of survival functions of patient groups with log-rank test using the Freedman method, with the significance level set to 5%, power to 80%, and survival probabilities of 90% and 60%, based on previously published data from our group.9 This resulted in a required sample size of 74 patients and 19 outcomes.

Definition of outcomes

Outcome was defined as liver transplantation and liver-related death. All-cause mortality and development of hepatobiliary malignancies were recorded but not considered outcomes.

Image acquisition

MRI/MRCP examinations from Karolinska University Hospital were performed using two different 1.5T MRI Siemens scanners (Magnetom Aera and Magnetom Avanto, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). Examinations from Uppsala University Hospital were performed with Philips 1.5T MRI scanner (Achieva, Philips Healthcare). Examinations from Skåne University Hospital were performed with 1.5T and 3T MRI scanners from different vendors (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany, Philips Healthcare and GE Healthcare).

For the purposes of our study, we used only 3D-MRCP acquired in coronal plane and an axial T2-weighted image of the liver for anatomic correlation. Technical parameters of the sequences are presented in Table S1. All patients were fasting for at least 4 h prior to examination. No oral contrast was used.

Development of the DiStrict score

Based on results from previous studies we developed a score (DiStrict score) for individuals with large-duct PSC, by combining cholangiographic findings that have been previously associated with outcomes and have the potential to be reproducible; namely presence and extent of strictures, and bile duct dilatation caused by strictures.11,13,14,19

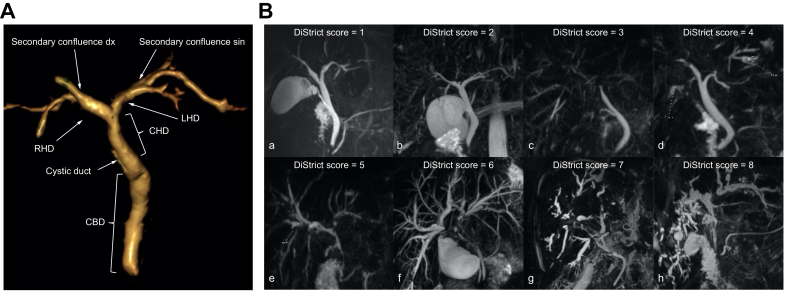

The biliary tree was divided into extrahepatic (EHD) and intrahepatic (IHD) portions. Extrahepatic ducts included the common bile duct (CBD), common hepatic duct (CHD), right (RHD) and left (LHD) hepatic ducts, up to secondary biliary confluence. Ducts peripheral to secondary biliary confluence were considered intrahepatic (Fig. 2A).

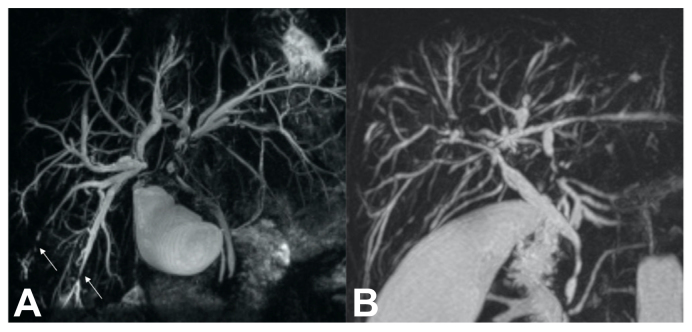

Fig. 2.

3D volume-rendered image of bile duct anatomy and MRCP images from individuals with PSC.

(A) 3D volume-rendered image of bile duct anatomy, used for DiStrict score. Extrahepatic ducts include common bile duct, common hepatic duct, right and left hepatic ducts up to secondary biliary confluence. Ducts peripheral to secondary confluence are considered intrahepatic. (B) MRCPs of individuals with PSC with different DiStrict scores and IHD and EHD points in parentheses. a) DiStrict score = 1 (EHD = 0, IHD = 1), b) DiStrict score = 2 (EHD = 0, IHD = 2), c) DiStrict score = 3 (EHD = 1, IHD = 2), d) DiStrict score = 4 (EHD = 1, IHD = 3), e) DiStrict score = 5 (EHD = 2, IHD = 3), f) DiStrict score = 6 (EHD = 4, IHD = 2), g) DiStrict score = 7 (EHD = 3, IHD = 4), h) DiStrict score = 8 (EHD = 4, IHD = 4). EHD, extrahepatic ducts; IHD, intrahepatic ducts; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Strictures were classified into two types: 1) strictures causing upstream dilatation (toward liver periphery), and 2) strictures without upstream dilatation.

Dilatation of the different portions of the biliary tree was defined as follows: CBD/CHD ≥8 mm for patients younger than 65 years that have not undergone cholecystectomy; CBD/CHD ≥10 mm for patients older than 65 years and/or post cholecystectomy; RHD/LHD ≥6 mm; IHD ≥4 mm.

The extent of ductal involvement was divided into two categories: 1) extent >25% (diffuse) and 2) extent ≤25% (localised). For EHD, extent was defined as the total length of a type of stricture divided by the sum of total length of the EHD (extent = stricture length/total length of CBD+CHD+RHD+LHD). For IHD, extent ≤25% was equivalent to presence of a type of stricture in up to two segments, according to the Couinaud classification.20,21

Intrahepatic and extrahepatic ductal changes were classified into five categories each. All categories were assigned a number ranging from 0 (no changes) to 4 (most severe changes). Each number yielded equal points. The DiStrict score was generated by addition of these points (DiStrict score = IHD+EHD, which consequently ranges from 0 to 8). An increase in the score indicated an increase in the severity of ductal changes. Table 2 shows the IHD and EHD ductal changes and their corresponding points used for the calculation of the DiStrict score. This score introduced a new approach in evaluating strictures and dilatation. It was designed to both evaluate intrahepatic and extrahepatic strictures separately, and to associate strictures’ direct effects on duct width to the portion of the biliary tree to which the strictures belong. Therefore, IHD could not be assigned with 3 or 4 points if the only possible cause of their dilatation was a stricture of the EHD. The IHD could be assigned 3 or 4 points only in the presence of intrahepatic strictures that were causing their dilatation, irrespective of the presence of strictures in the EHD.

Table 2.

Intrahepatic and extrahepatic ductal changes and corresponding points for calculation of the DiStrict score.

| Points |

Ductal changes |

|---|---|

| IHDa | |

| 0 | No changes |

| 1 | Strictures without upstream dilatation in ≤25% of the liverb |

| 2 | Strictures without upstream dilatation in >25% of the liver |

| 3 | Strictures with upstream dilatation in ≤25% of the liver |

| 4 |

Strictures with upstream dilatation in >25% of the liver |

| EHD | |

| 0 | No changes |

| 1 | Strictures without upstream dilatation in ≤25% of total length of EHD |

| 2 | Strictures without upstream dilatation in >25% of total length of EHD |

| 3 | Strictures with upstream dilatation in ≤25% of total length of EHD |

| 4 | Strictures with upstream dilatation in >25% of total length of EHD |

EHD, extrahepatic ducts; IHD, intrahepatic ducts.

IHD are registered as 3 or 4 only in presence of intrahepatic strictures that can be presumed as the mechanical cause of their dilatation.

Definitions of ductal dilatation: common bile duct/common hepatic duct ≥8 mm for patients younger than 65 years that have not undergone cholecystectomy; common bile duct/common hepatic duct ≥10 mm for patients older than 65 years and/or post cholecystectomy; right hepatic duct/left hepatic duct ≥6 mm; IHD ≥4 mm.

The score was tested first by one of the authors (A.G.) in 30 individuals with PSC (not included in the study) to evaluate applicability, with good results.

DiStrict score 0 in a patient with diagnosed PSC indicated small-duct PSC. A DiStrict score of 1–2 was defined as mild changes with no intrahepatic or extrahepatic dilatation, and a DiStrict score of 7–8 was defined as severe changes with both intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct dilatation. The intermediate group, with a DiStrict score between 3–6, with varying states of dilatation and extent of ductal changes, was defined as having moderate to more advanced changes. A score ≥5 indicated the definite presence of intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic dilatation, suggesting more severe ductal changes compared to scores of 3–4. Table 3 shows the DiStrict score, the corresponding grade of ductal changes severity, and how the score is generated using combinations of different IHD and EHD points. Examples of different DiStrict scores are depicted in Fig. 2B.

Table 3.

The DiStrict score for individuals with large-duct PSC.

| DiStrict score | IHD-EHD points | Extension1 | Dilatation | Severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0+0 | No changes2 | — | — |

| 1 | 0+1, 1+0 | Localised IHD or EHD | — | Mild |

| 2 | 1+1, 0+2, 2+0 | Diffuse IHD or EHD/Localised IHD+EHD | — | |

| 3 | 1+2, 2+1, 0+3, 3+0 | Diffuse/Localised EHD or IHD | +/− | Moderate-advanced |

| 4 | 2+2, 1+3, 3+1, 0+4, 4+0 | Diffuse/Localised IHD and/or EHD | +/− | |

| 5 | 2+3, 3+2, 1+4, 4+1 | Diffuse/Localised IHD and/or EHD | + | |

| 6 | 3+3, 2+4, 4+2 | Diffuse/Localised IHD and/or EHD | + | |

| 7 | 3+4, 4+3 | Diffuse/Localised IHD+EHD | + | Severe |

| 8 | 4+4 | Diffuse IHD+EHD | + |

Combinations of IHD and EHD points that generate the score, corresponding extension of ductal changes, presence or not of ductal dilatation and grade of severity of ductal changes.

EHD, extrahepatic ducts; IHD, intrahepatic ducts; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Extension considers the highest points in each pair of points.

No changes indicates small-duct PSC in a patient with diagnosed PSC.

Image evaluation

Six radiologists (readers) from four different institutions and two countries were recruited. The images of the 103 individuals from Stockholm were evaluated independently by two experienced radiologists (each of whom evaluate more than 100 MRI/MRCPs of individuals with PSC per year); one from Karolinska University Hospital (A.G.) and one from Hannover Medical School (K.I.R.). The 52 patients from Uppsala were evaluated independently by two local radiologists (working at Uppsala University Hospital at the time of the study); one experienced radiologist (N.K.H) and one less-experienced radiologist (C.F) (<100 MRI/MRCP of individuals with PSC per year). The 65 patients from Skåne University hospital were evaluated independently by two experienced local radiologists (J.B., E.F.B.). Readers were introduced to the DiStrict score by one of the authors (A.G) during digital (Uppsala and Skåne) or physical meetings (Stockholm). After a short presentation of the score (about 10 min), readers applied the score together with the author (A.G.) in 5–10 patients (not included in the study). They were then asked to apply the score independently to their respective cohort. The readers evaluated the quality of the MRCP images and deemed them as having adequate or insufficient quality for the assessment of the presence and extent of strictures and dilatations, and for the assessment of bile duct width. Images that were considered of insufficient quality were excluded by the respective readers. One reader from each institution (A.G, J.B, N.K.H) performed the reading twice with an interval of least 2 weeks, to evaluate intrareader agreement. Furthermore, one reader from each of the three institutions (A.G., J.B., N.K.H.) evaluated a common, randomly chosen subset of patients. For the purposes of survival analysis, cases of disagreement were resolved during a separate consensus reading by respective readers.

Readers were aware of PSC diagnosis but were blinded to other clinical and laboratory data. They were allowed to change window settings on both sequences and make their own maximum intensity projection reconstructions from the 3D-MRCPs. Measurements were made from non-reconstructed 3D-MRCP images. The readers were also instructed to give specific attention to the fact that intraductal stones, air, and susceptibility artifacts could make the ducts and their width difficult to evaluate on MRCP due to loss of signal. A complete guide for the application of the DiStrict score is provided in the supplementary material.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographics and clinical and laboratory data are presented as medians and ranges or as absolute numbers and percentages.

Inter-reader agreement was calculated with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) using a two-way random effects model, absolute agreement, and single measurements. Intrareader agreement was calculated with ICC using a two-way mixed effects model, absolute agreement, and single measurements.22,23 ICC >0.90 indicated excellent agreement, ICC between 0.75 and 0.90 good agreement, ICC between 0.50 and 0.75 moderate agreement and ICC <0.50 poor agreement.23

Association of DiStrict score and laboratory values with outcomes was evaluated with univariate Cox proportional-hazards regression analysis. The proportional-hazards assumption was tested. Variables that had p value <0.05 in the univariate analysis were entered into a multivariable model to find variables significantly and independently associated with outcomes. All Cox-regression analysis was performed using clustered standard errors to take into consideration clustering within the three sub-cohorts. Receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis was performed to find the best DiStrict score cut-off for predicting outcome development (Table S2, Fig. S1). Harrell’s C concordance statistic was calculated as a measure of the diagnostic accuracy of the DiStrict score. Assessment of survival rates was performed with Kaplan-Meier estimates and the curves were compared with log-rank test. Survival time was the time between the MRI/MRCP examination and last visit or development of outcome. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with STATA 15.1.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Two hundred and twenty individuals with large-duct PSC were evaluated;148 (67%) were males with a median age at diagnosis of 31 years (range 8–68). 186 (85%) had inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis, n =135; Crohn’s disease, n =40; indeterminate colitis, n =11). During a median follow-up time of 7.4 years (range 0.3–10.6 years), 40 patients developed outcomes (liver transplantation; n =33, liver-related death; n =7) and five patients developed hepatobiliary cancers and were alive at the end of the study period (cholangiocarcinoma, n = 3; gallbladder cancer, n = 2). The mean and median values of the DiStrict score were 4 for the whole cohort. Median model for end-stage liver disease score was 6 (range 6–21).

Assessment of agreement

In addition to evaluating inter-reader agreement of pairs of readers, evaluation of agreement between readers from different institutions was performed in two ways. First, by assessing the agreement between the Stockholm readers (working at different institutions in different countries) and second, by assessing agreement in the subset of patients evaluated by readers from the three different institutions.

For the pairs of experienced readers (Stockholm/Hannover and Skåne) and readers from different centres and countries (Stockholm/Hannover), agreement was good (ICC 0.82; 95% CI 0.74–0.87, ICC 0.81; 95% CI 0.70–0.88). For the pair of the experienced and less-experienced readers (Uppsala), agreement was poor (ICC 0.48; 95% CI 0.05–0.72). Agreement between readers from all three institutions was good (ICC 0.76; 95% CI 0.57–0.89). Intrareader agreement for the Stockholm reader (A.G.) was excellent (ICC 0.93; 95% CI 0.90–0.95), and good for the Uppsala reader (N.K.H) (ICC 0.85; 95% CI 0.75–0.91) and for reader from Skåne (J.B) (ICC 0.87; 95% CI 0.80–0.92).

Assessment of DiStrict score’s prognostic value

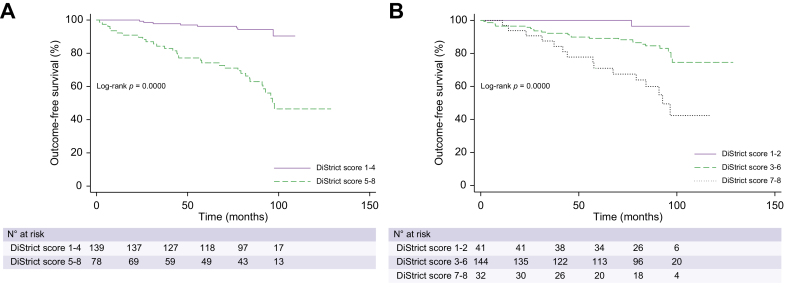

Three patients were excluded from the analysis because their DiStrict score was 0 according to the consensus reading (i.e., small-duct PSC). In univariate Cox-regression analysis, DiStrict score was significantly associated with outcomes (p <0.001) with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.63 (95% CI 1.33–1.99) (Table 4). The proportional-hazards assumption was tested and was shown not to be violated (p = 0.83). In the multivariable model, including alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyltransferase and bilirubin, DiStrict score remained significant (HR 1.51; 95% CI 1.24–1.83), and had higher HR compared to the laboratory variables (Table 4). Harrell's C concordance statistic for DiStrict score was 0.78. A cut-off for DiStrict scores ≥5 rendered best balance between sensitivity and specificity (sensitivity = 80%, specificity = 74%) (Table S2). Patients were therefore allocated into one of two groups based on a DiStrict score cut-off of 5. Patients with high scores (DiStrict score = 5–8) had significantly worse survival (p <0.001) than patients with low scores (DiStrict score =1–4), as shown in Kaplan-Meier curves in Fig. 3A. Five-year survival was 96% (95% CI 0.91–0.98) for patients with low scores, compared to 74% (95% CI 0.62–0.83) for patients with high scores. Only one patient with a DiStrict score ≤3 and eight with DiStrict scores <5 developed outcomes. Patients with high scores had an 8.2-fold higher risk of developing outcomes compared to patients with low scores (HR 8.2; 95% CI 2.97–22.65).

Table 4.

HR point estimates and 95% CI in parentheses of DiStrict score and laboratory values, after univariate and multivariate Cox proportional-hazards regression analysis.

| Variable | Univariate |

Multivariate |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | p value | HR | p value | |

| DiStrict score | 1.63 (95% CI 1.33–1.99) | <0.001 | 1.51 (95% CI 1.24–1.83) | <0.001 |

| Bilirubin | 1.06 (95% CI 1.04–1.08) | <0.001 | 1.04 (95% CI 1.01–1.06) | 0.004 |

| ALP | 1.14 (95% CI 1.08–1.20) | <0.001 | 1.05 (95% CI 1.00–1.10) | 0.048 |

| GGT | 1.06 (95% CI 1.05–1.08) | <0.001 | 1.04 (95% CI 1.01–1.06) | 0.001 |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; HR, hazard ratio.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves of outcome-free survival according to DiStrict score.

(A) Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank test for survival without outcome (liver transplantation and liver-related death) for individuals with low DiStrict scores (1–4) (solid line) and high DiStrict scores (5–8) (dashed line). (B) Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank test for survival without outcome (liver transplantation and liver-related death) for individuals with mild (DiStrict score = 1–2; solid line), moderate to advanced (DiStrict score = 3–6; dashed line), and severe (DiStrict score = 7–8; dotted line) ductal changes.

We also performed a sub-analysis by dividing patients into three categories, depending on the severity of ductal changes: namely patients with mild changes (DiStrict score = 1–2); moderate to advanced ductal changes (DiStrict score = 3–6); and severe ductal changes (DiStrict score = 7–8). Patients in these categories also had differences in survival (p <0.001), as shown in Fig. 3B. Five-year survival was 100% for patients with mild changes, 89% for patients with moderate changes (95% CI 0.82–0.93), and 70% for patients with severe ductal changes (95% CI 0.50–0.83). For each incremental change of group (namely from low to moderate and from moderate to severe) the risk of developing outcomes increased by 3.5 times (HR = 3.43; 95% CI 1.65–7.17).

Discussion

In this study, we present a novel and simple MRCP-based prognostic score for individuals with PSC, the DiStrict score, based on the severity and extent of cholangiographic changes. Inter-reader agreement between experienced readers was good for the DiStrict score and it was strongly associated with outcomes.

This is the first study to evaluate the prognostic value of a score that is based on cholangiographic changes derived explicitly from MRCP. Our results show that the DiStrict score is strongly associated with clinically important outcomes (liver transplantation and liver-related death). Patients with a high score (DiStrict score = 5–8) have an 8.2-fold higher risk of developing adverse outcomes compared to patients with low scores (DiStrict score = 1–4). This is in line with previous studies assessing the prognostic value of various imaging findings, including cholangiography.11,13,19,[24], [25], [26] Our study confirms the value of cholangiographic findings in PSC prognostication, previously evaluated with ERCP,11,12 and provides data showing that MRCP findings alone have independent prognostic value. This is important for many reasons. In an effort to recognise and utilise reproducible imaging biomarkers in PSC, good agreement of the DiStrict score is promising, as the inter-reader agreement for MRI/MRCP in PSC is known to be low.[8], [9], [10] Moreover, MRCP is always a part of an MRI examination of individuals with PSC.7 This, together with its simplicity, increases the applicability of the DiStrict score. This score enables patient stratification into high- and low-risk of developing adverse outcomes. It provides valuable additional information to current clinical tools such as elastography and clinical scores[27], [28], [29] and it may be useful for patient counselling, identification of patients that need closer follow-up, and patient stratification in prospective clinical trials.

The DiStrict score demonstrated independent prognostic value in the multivariate analysis including biomarkers of cholestasis, such as alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyltransferase, and bilirubin. Moreover, the DiStrict score had comparable prognostic performance when compared to ANALI scores.9,19 However, we did not calculate ANALI scores in our study, and direct comparison is difficult due to different outcome definitions.

Earlier studies on the prognostic importance of cholangiographic findings in PSC were based on descriptions and classifications made using ERCP. Application of terms derived from ERCP directly to MRCP is generally discouraged.7,30 This new score is developed explicitly from findings present and described in MRCP. Moreover, it is developed in such a way that increases in the score indicate increases in severity of ductal changes. For example, in the Majoie classification of intrahepatic ducts, ranging from 0–III, the lower categories (I and II) reflect cholangiographic progression, whereas category III offers little information about intrahepatic strictures.24

One advantage of the DiStrict score is that it provides an overview of the presence and the severity of bile duct changes separately for IHD and EHD. This is the first time that the effect of strictures on ductal width – as a measure of stricture severity and bile flow obstruction – has been examined in such a way. Up to now, dilatation of IHD caused by a stricture of the EHD was assessed in the same manner as dilation of IHD caused by intrahepatic strictures, irrespective of the presence of EHD strictures. The DiStrict score handles these two cases differently by assigning the dilatation of ducts to either intrahepatic or extrahepatic strictures. We believe that this new approach evaluates more accurately the potential effect of strictures of the different portions of the biliary tree on liver function (as indicated partially by the need for liver transplantation) and their role in the natural history of the disease.

Evaluation of imaging findings in individuals with PSC has been shown to be challenging, even for experts.[8], [9], [10] Assessment of bile ducts in particular is a difficult task owing to their small size and high number, and the fact that MRCP is sensitive to several types of artifacts that may reduce image quality. Nevertheless, bile duct changes are key findings in PSC and play a significant role in patient management. Few studies have evaluated the inter-reader agreement of imaging findings in individuals with PSC, which is an important step when assessing potential applicability of any imaging-based biomarker in clinical practice. The proposed DiStrict score is reproducible when applied by experienced radiologists, as shown in this study after extensive agreement assessment. The lower level of agreement found for the pair of experienced and less-experienced readers is not surprising, taking into consideration the difficulty of interpretating examinations of individuals with PSC. This finding underscores that examinations of individuals with PSC should be evaluated in high-volume centres by experienced radiologists, which is in line with the recommendation of the iPSC study group7 (Fig. 4). Nevertheless, the level of agreement may be improved by further reader training in the application of the DiStrict score.

Fig. 4.

Agreement and disagreement between readers in the application of DiStrict score.

Maximum intensity projection from 3D-MRCPs of a (A) 45-year-old and a (B) 35-year-old with large-duct PSC. (A) Both readers assigned DiStrict score = 6 (EHD = 4, IHD = 2). Notice that EHD are given 4 points due to the confluence stricture that engages by continuum the secondary biliary confluence and causes upstream dilatation of intrahepatic ducts. IHD were given a score of 2 because the aetiology of duct dilation was considered to be only the confluence stricture. Intrahepatic strictures are also present (white arrows); however, they do not cause upstream dilatation. (B) One reader assigned a DiStrict score of 3 (EHD = 1, IHD = 2) and the other a DiStrict score of 5 (EHD = 2, IHD = 3). EHD, extrahepatic ducts; IHD, intrahepatic ducts; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Our study has limitations. We did not perform external validation. The DiStrict score was developed based on clinical experience and previous findings and not in a data-driven manner. By applying it and assessing its prognostic value we validated the score in our cohort. Moreover, we used a combined cohort from three different geographical areas and centres, which increases generalizability. Further validation in other cohorts would be, nonetheless, of great value. The differentiation between benign and malignant strictures is challenging in PSC and the potential of the DiStrict score to predict development of bile duct cancer was not evaluated. The low occurrence of hepatobiliary malignancy in the population-based setting, however, makes this study cohort unsuitable for such evaluation. Lastly, we did not evaluate the potential dynamic function of the score longitudinally and the potential effect of interventional procedures to the score. This remains to be evaluated in future studies.

In conclusion, the novel DiStrict score, developed through combination of imaging findings present and described solely on MRCP, is simple, reproducible, and associated with clinical outcomes. The DiStrict score can easily be applied in clinical practice and, thus has the potential to be useful in clinical trials and patient counselling and management.

Financial support

This study has received funding from Stockholm County Council (SLL 20180096), The Swedish Cancer Society (20 0717 PjF 01 H) and Cancer Research Funds, Radiumhemmet.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Aristeidis Grigoriadis, Annika Bergquist, Nikolaos Kartalis, Kristina Imeen Ringe. Data curation: all authors. Formal Analysis: Aristeidis Grigoriadis, Annika Bergquist, Nikolaos Kartalis, Kristina Imeen Ringe. Funding acquisition: Annika Bergquist, Nikolaos Kartalis. Investigation: all authors. Methodology: Aristeidis Grigoriadis, Annika Bergquist, Nikolaos Kartalis, Kristina Imeen Ringe. Project administration: Aristeidis Grigoriadis, Annika Bergquist, Nikolaos Kartalis. Resources: Annika Bergquist, Nikolaos Kartalis, Johan Bengtsson, Nafsika Korsavidou-Hult, Fredrik Rorsman, Emma Nilsson. Software: Aristeidis Grigoriadis, Annika Bergquist, Nikolaos Kartalis, Kristina Imeen Ringe. Supervision: Annika Bergquist, Nikolaos Kartalis. Validation: Annika Bergquist, Nikolaos Kartalis, Aristeidis Grigoriadis. Visualization: Aristeidis Grigoriadis, Annika Bergquist, Nikolaos Kartalis. Writing-original draft: Aristeidis Grigoriadis, Annika Bergquist, Nikolaos Kartalis. Writing-review & editing: Aristeidis Grigoriadis, Annika Bergquist, Nikolaos Kartalis. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon request.

Conflicts of interest

Kristina Imeen Ringe received an honorarium from Bayer Healthcare. Fredrik Rorsman: advisory board for Norgine, Intercept; speaker fee from Norgine, Gore; research support from Norgine, Antaros Medical, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. Annika Bergquist has received a research grant from Gilead. Nikolaos Kartalis is a consultant speaker for Bayer.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Acknowledgements

Biostatistician Anna Warnqvist (Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden) kindly provided statistical advice for the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2022.100595.

Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Boonstra K., Weersma R.K., Erpecum K.J., Rauws E.A., Spanier B.W.M., Poen A.C., et al. Population-based epidemiology, malignancy risk, and outcome of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2013;58:2045–2055. doi: 10.1002/hep.26565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyson J.K., Beuers U., Jones D.E.J., Lohse A.W., Hudson M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Lancet. 2018;391:2547–2559. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weismuller T.J., Trivedi P.J., Bergquist A., Imam M., Lenzen H., Ponsioen C.Y., et al. Patient Age, sex, and inflammatory bowel disease phenotype Associate with course of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1975–1984 e1978. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergquist A., Ekbom A., Olsson R., Kornfeldt D., Loof L., Danielsson A., et al. Hepatic and extrahepatic malignancies in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2002;36:321–327. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman R., Fevery J., Kalloo A., Nagorney D.M., Boberg K.M., Shneider B., et al. Diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:660–678. doi: 10.1002/hep.23294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Association for the Study of the L. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of cholestatic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2009;51:237–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schramm C., Eaton J., Ringe K.I., Venkatesh S., Yamamura J., IPSCSG MRI Working Group Recommendations on the use of magnetic resonance imaging in PSC-A position statement from the International PSC Study Group. Hepatology. 2017;66:1675–1688. doi: 10.1002/hep.29293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grigoriadis A., Morsbach F., Voulgarakis N., Said K., Bergquist A., Kartalis N. Inter-reader agreement of interpretation of radiological course of bile duct changes between serial follow-up magnetic resonance imaging/3D magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:228–235. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2020.1720281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grigoriadis A., Ringe K.I., Andersson M., Kartalis N., Bergquist A. Assessment of prognostic value and interreader agreement of ANALI scores in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Eur J Radiol. 2021;142 doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.109884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zenouzi R., Liwinski T., Yamamura J., Weiler-Normann C., Sebode M., Keller S., et al. Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging/3D-magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: challenging for experts to interpret. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:169–178. doi: 10.1111/apt.14797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craig D.A., MacCarty R.L., Wiesner R.H., Grambsch P.M., LaRusso N.F. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: value of cholangiography in determining the prognosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:959–964. doi: 10.2214/ajr.157.5.1927817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Majoie C.B., Reeders J.W., Sanders J.B., Huibregtse K., Jansen P.L. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: a modified classification of cholangiographic findings. AJR Am J roentgenology. 1991;157:495–497. doi: 10.2214/ajr.157.3.1651643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsson R.G., Asztely M.S. Prognostic value of cholangiography in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7:251–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruiz A., Lemoinne S., Carrat F., Corpechot C., Chazouilleres O., Arrive L. Radiologic course of primary sclerosing cholangitis: assessment by three-dimensional magnetic resonance cholangiography and predictive features of progression. Hepatology. 2014;59:242–250. doi: 10.1002/hep.26620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffin N., Charles-Edwards G., Grant L.A. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography: the ABC of MRCP. Insights into imaging. 2011;3:11–21. doi: 10.1007/s13244-011-0129-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irie H., Honda H., Kuroiwa T., Yoshimitsu K., Aibe H., Shinozaki K., et al. Pitfalls in MR cholangiopancreatographic interpretation. Radiographics. 2001;21:23–37. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.1.g01ja0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammel P., Couvelard A., O’Toole D., Ratouis A., Sauvanet A., Fléjou J.F., et al. Regression of liver fibrosis after biliary drainage in patients with chronic pancreatitis and stenosis of the common bile duct. New Engl J Med. 2001;344:418–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oral Abstracts Hepatology. 2021;74:1–156. doi: 10.1002/hep.32187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemoinne S., Cazzagon N., El Mouhadi S., Trivedi P.J., Dohan A., Kemgang A., et al. Simple magnetic resonance scores associate with outcomes of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(13):2654–2656. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Couinaud C. Masson; 1957. Le foie: études anatomiques et chirurgicales. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Couinaud C. Surgical anatomy of the liver. Acheve d'Imprimer. 1989:61–74. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shrout P.E., Fleiss J.L. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koo T.K., Li M.Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponsioen C.Y., Vrouenraets S.M., Prawirodirdjo W., Rajaram R., Rauws E.A., Mulder C.J., et al. Natural history of primary sclerosing cholangitis and prognostic value of cholangiography in a Dutch population. Gut. 2002;51:562–566. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.4.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tischendorf J.J., Hecker H., Kruger M., Manns M.P., Meier P.N. Characterization, outcome, and prognosis in 273 patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a single center study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:107–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudolph G., Gotthardt D., Kloters-Plachky P., Kulaksiz H., Rost D., Stiehl A. Influence of dominant bile duct stenoses and biliary infections on outcome in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2009;51:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corpechot C., Gaouar F., El Naggar A., Kemgang A., Wendum D., Poupon R., et al. Baseline values and changes in liver stiffness measured by transient elastography are associated with severity of fibrosis and outcomes of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:970–979. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.030. quiz e915-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehlken H., Wroblewski R., Corpechot C., Arrive L., Rieger T., Hartl J., et al. Validation of transient elastography and comparison with spleen length measurement for staging of fibrosis and clinical prognosis in primary sclerosing cholangitis. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eaton J.E., Vesterhus M., McCauley B.M., Atkinson E.J., Schlicht E.M., Juran B.D., et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis risk estimate tool (PREsTo) predicts outcomes of the disease: a derivation and validation study using machine learning. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2020;71:214–224. doi: 10.1002/hep.30085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venkatesh S.K., Welle C.L., Miller F.H., Jhaveri K., Ringe K.I., Eaton J.E., et al. Reporting standards for primary sclerosing cholangitis using MRI and MR cholangiopancreatography: guidelines from MR working group of the international primary sclerosing cholangitis study group. Eur Radiol. 2021;32(2):923–937. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-08147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.