Abstract

Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae give rise to dramatically different diseases. Their interactions with the host, however, do share common characteristics: they are both human pathogens which do not survive in the environment and which colonize and invade mucosa at their port of entry. It is therefore likely that they have common properties that might not be found in nonpathogenic bacteria belonging to the same genetically related group, such as Neisseria lactamica. Their common properties may be determined by chromosomal regions found only in the pathogenic Neisseria species. To address this issue, we used a previously described technique (C. R. Tinsley and X. Nassif, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11109–11114, 1996) to identify sequences of DNA specific for pathogenic neisseriae and not found in N. lactamica. Sequences present in N. lactamica were physically subtracted from the N. meningitidis Z2491 sequence and also from the N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 sequence. The clones obtained from each subtraction were tested by Southern blotting for their reactivity with the three species, and only those which reacted with both N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae (i.e., not specific to either one of the pathogens) were further investigated. In a first step, these clones were mapped onto the chromosomes of both N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae. The majority of the clones were arranged in clusters extending up to 10 kb, suggesting the presence of chromosomal regions common to N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae which distinguish these pathogens from the commensal N. lactamica. The sequences surrounding these clones were determined from the N. meningitidis genome-sequencing project. Several clones corresponded to previously described factors required for colonization and survival at the port of entry, such as immunoglobulin A protease and PilC. Others were homologous to virulence-associated proteins in other bacteria, demonstrating that the subtractive clones are capable of pinpointing chromosomal regions shared by N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae which are involved in common aspects of the host interaction of both pathogens.

Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are two human pathogens which belong to the same genospecies. Furthermore, phylogenetic analyses by rRNA similarities and DNA-DNA hybridizations have placed N. meningitidis, N. gonorrhoeae, N. lactamica, and N. cinerea in a subgroup with particularly close interspecies relatedness (19, 27, 39). Although these bacteria are closely related, they express very different pathogenicities. N. lactamica and N. cinerea are nonpathogenic. N. meningitidis colonizes the nasopharynx, from where it may spread into the bloodstream before crossing the blood-brain barrier to induce meningitis. N. gonorrhoeae colonizes and invades the epithelium of the genitourinary tract and may cause a localized inflammatory process or an ascending infection leading to salpingitis. However, even though N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae give rise to two very different diseases, they both have to colonize and cross an epithelium at their port of entry. This is consistent with the fact that in addition to having specific virulence factors, they have common virulence attributes such as pili, immunoglobulin A (IgA) proteases, and class 5 outer membrane proteins. However other as yet unidentified proteins, some of which are specific for the pathogenic Neisseria species and are not found in N. lactamica, are most probably involved in this common step of interaction of these bacterial pathogens with their host.

While differences in pathogenic potential may theoretically result from differential expression or subtly differing proteins, the situation is more generally found to involve the possession of pathogen-specific sequences. Attributes of bacterial virulence are often grouped in islands and frequently are passed horizontally between more or less closely related species (22). Representational difference analysis (33, 44) provides a quick means of cloning DNA corresponding to such species-specific sequences, by direct physical subtraction of the chromosomal DNA of a closely related, avirulent strain from the chromosomal DNA of the pathogen. Thus large islands of DNA which may encode N. meningitidis-specific virulence factors which are not present in N. gonorrhoeae have recently been identified. To identify the chromosomal regions that are common to pathogenic Neisseria species and are responsible for the colonization and survival at the port of entry, we first subtracted from N. meningitidis those sequences which were also present in the commensal N. lactamica and then performed a similar experiment subtracting the N. lactamica sequences from the chromosome of N. gonorrhoeae. The results of these experiments confirmed that both pathogens have common sequences which are absent from the nonpathogenic N. lactamica and identify putative virulence factors involved in survival and dissemination from the port of entry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

N. meningitidis Z2491 and N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 were chosen as reference pathogenic Neisseria strains; both are in the process of being sequenced, and both also have many of their important genetic markers positioned on published macrorestriction maps (10, 11). Two strains of N. lactamica, 8064 and 9764, from this laboratory were used to provide DNA for subtraction. Other strains came from the collection of X. Nassif. Neisseria strains were grown on GCB (Difco) agar plates, containing the Kellogg supplements and ferric nitrate (26), for 14 to 16 h at 37°C in a humid atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Molecular genetic techniques.

Routine molecular biological techniques were carried out as recommended (3, 41). DNA sequences were determined by using an ABI-Prism 370 automated sequencer with the Big Dye primer-sequencing kit. Southern blotting was performed as previously described (7, 44) but omitting the bovine serum albumin from the hybridization buffer. DNA fragments were labelled for Southern hybridizations by random-primed incorporation of [α-32P]dCTP. Chromosomal DNA extraction was performed on cells grown in broth or scraped from agar plates. Bacteria from one 7-cm plate or from 10 ml of broth were suspended in 1 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–10 mM EDTA–100 mM NaCl containing 2 μg of RNase A. After addition of 50 μl of 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate and incubation at 65°C for 30 min, the mixtures were digested for 2 h at 37°C with proteinase K (100 μg). The solutions were then extracted once with an equal volume of phenol (pH 8), twice with phenol-choroform-isopentanol (25:24:1), and once with chloroform-isopentanol (24:1). The solution was overlaid with an equal volume of ethanol and cooled to 0°C, and the DNA was spooled from the interface by mixing with a glass Pasteur pipette. The fibrous DNA was washed in 70% ethanol, partially dried, and then redissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 1 mM EDTA).

Chromosomal DNA was quantified by UV spectrophotometry. For quantification of fragmented DNA, preparations were diluted into TE buffer containing 1 μg of ethidium bromide per ml and appropriate dilutions were performed to produce 20-μl samples containing 1, 1/3, 1/10, 1/30, and 1/100 μl of the DNA preparation. In parallel, solutions of 200, 100, 50, 20, 10, 5, and 0 ng of standard DNA per 20 μl (HindIII digest of lambda phage) were prepared in the same solution. Drops were placed on a sheet of polyethylene film, illuminated with UV light, and photographed. The concentration of the DNA preparation was measured against the scale of luminosities of the lambda DNA standards.

Representational difference analysis.

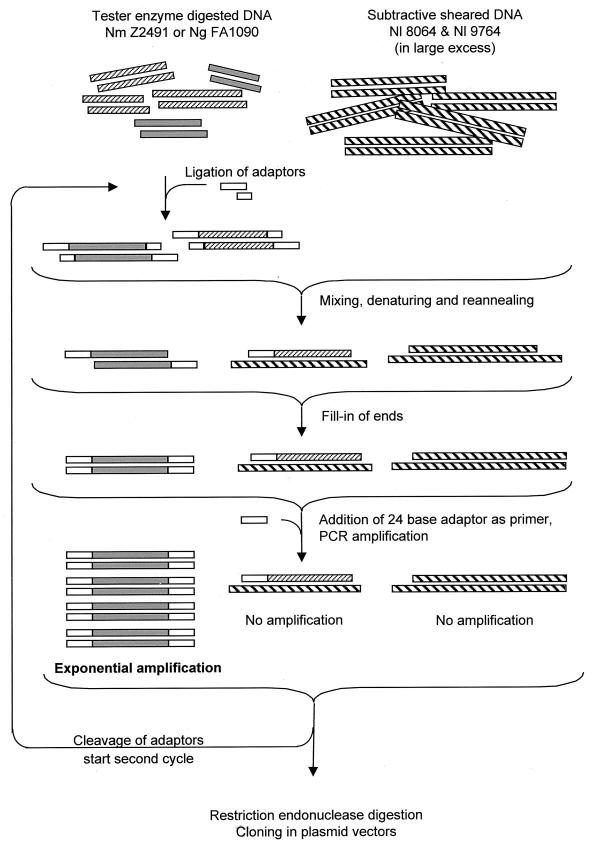

Clones of DNA fragments present in the genome of N. meningitidis and/or that of N. gonorrhoeae but absent from N. lactamica were prepared essentially as described previously (44) (Fig. 1). Six banks were created, three for N. gonorrhoeae and three for N. meningitidis. Briefly, 20 μg of DNA from N. gonorrhoeae or N. meningitidis was cleaved with MboI, MspI, or Tsp509I, precipitated with ethanol-sodium acetate, and ligated with 5 nmol of the appropriate oligonucleotide adapter pair (RBam12 and RBam24, RCla12 and RCla24, or REco12 and REco24 [Table 1]) for 18 h at 11°C. The mixture was gel purified on 2% low-melting-point agarose (taking fragments above 200 bp) to remove unincorporated primers, phenol purified, precipitated, and redissolved in TE buffer. This procedure results in DNA fragments whose two 5′ ends are covalently linked to the 24-base adapter. To prepare the subtracting DNA, chromosomes of two strains of N. lactamica were sheared by repeated passage through a hypodermic needle to give fragments ranging from about 3 to 10 kb. The DNA was repurified by phenol extraction, precipitated, and redissolved in TE buffer. Equal quantities of the two were mixed to make the subtracting DNA.

FIG. 1.

Procedure for representational difference analysis. Sequences specific to the pathogen are represented in grey; those in common with N. lactamica are hatched. DNA from N. meningitidis or from N. gonorrhoeae was digested with frequently cutting restriction endonucleases and ligated to adapter pairs such that only the 5′ end of each DNA stand was covalently linked to the 24-bp adapter. On denaturing, mixing, and reannealing, only the (pathogen-specific) sequences with an adapter covalently linked were able to rehybridize with their complementary sequence. The fragments of randomly sheared N. lactamica chromosome are generally over 10 times as long as the restriction fragments from the pathogen and not only sequester all pathogen fragments having homologies in N. lactamica but also, in the large majority of cases, prevent the polymerase from synthesizing the complement of the adapter during the filling-in procedure. Hence, these common fragments are effectively prevented from being amplified, and only the pathogen-specific fragments possessing an adapter at each end can be exponentially amplified.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| RBam12 | GATCCTCGGTGA |

| RBam24 | AGCACTCTCCAGCCTCTCACCGAG |

| JBam12 | GATCCGTTCATG |

| JBam24 | ACCGACGTCGACTATCCATGAACG |

| RCla10 | CGGTCGGTGA |

| RCla24 | AGCACTCTCCAGCCTCTCACCGAC |

| JCla10 | CGGGTTCATG |

| JCla24 | ACCGACGTCGACTATCCATGAACC |

| REco12 | AATTCTCGGTGA |

| REco24 | AGCACTCTCCAGCCTCTCACCGAG |

| JEco12 | AATTCGTTCATG |

| JEco24 | ACCGACGTCGACTATCCATGAACG |

The first subtractive hybridization was performed with 40 μg of N. lactamica subtracting DNA and 200 ng (MboI or MspI digested) or 400 ng (Tsp509I digested) of R-adapter-linked pathogen DNA fragments. The DNA was mixed, ethanol precipitated, and redissolved in 8μl of EE buffer [10 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(3-propanesulfonic acid), 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0)]. The liquid was overlaid with 30 μl of mineral oil, denatured at 100°C for 2 min, and then placed at 55°C. After the addition of 2 μl of 5 M NaCl, the mixture was left to hybridize at 55°C for 48 h.

The reaction mixture was then diluted 10-fold with preheated EE buffer-NaCl and immediately placed on ice. A portion of the subtraction mixture (10 μl) was diluted into 400 μl of PCR mix (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.0], 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.125 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 100 U of Taq polymerase per ml) to fill in the ends corresponding to the 24-base adapter. The reaction mixtures were diluted a further 10-fold, and PCR amplifications were performed on 400 μl of the dilutions. After denaturation for 5 min at 94°C and addition of the appropriate 24-base oligonucleotide, the mixtures were amplified by PCR (30 cycles of 1 min at 70°C, 3 min at 72°C, and 1 min at 94°C, followed by 1 cycle of 1 min at 94°C and 10 min at 72°C [Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp 9600 thermal cycler]). The amplified meningococcal DNA was separated by agarose gel electrophoresis from the primers and high-molecular-weight subtracting DNA.

The first adapters (R) were cleaved from the PCR products with the appropriate restriction enzymes, and the second-round adapters were ligated (2 μg of subtractive fragments and 2 nmol of adapters [JBam12 and JBam24, JCla12 and JCla24, or JEco12 and JEco24; Table 1] in a volume of 50 μl). The ligated fragments were gel purified and phenol extracted.

The second-round subtractive hybridization was performed with 25 ng of DNA from the pathogens (first-round products, cleaved and religated to the J adapters) and 40 μg of DNA from N. lactamica. Fragments amplified from the second round were cleaved with the appropriate enzyme, gel purified, and cloned into pBluescript (Stratagene) cleaved with the appropriate enzyme (BamHI for the MboI fragments, ClaI for the MspI fragments, and EcoRI for the Tsp509I fragments). The recombinant plasmids were maintained in Escherichia coli DH5α. Subsequent manipulations all used the PCR product corresponding to the inserted DNA, amplified between primers flanking the polycloning site of pBluescript.

Cloned DNA fragments were tested first by Southern blotting for their reactivity with N. meningitidis and/or N. gonorrhoeae and absence of reactivity with either of the strains of N. lactamica; this also permitted the elimination of obvious duplicate clones. Sequences were compared against other subtractive clones and against public-domain databases by using the BLAST algorithm (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, Md.) (2). The locations of the genes on the published macrorestriction maps of N. meningitidis Z2491 and of N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 were determined as described previously (44). The sequences were also used to extract the sequence of the chromosomal DNA surrounding the subtractive clones from the databases of the Z2491 genome sequencing project (46a) and FA1090 (44a). From this data, open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted by using the programs MacVector (Oxford Molecular Group, Oxford, United Kingdom) and CodonUse (Conrad Halling, Monsanto Corp.). These were also compared to sequences in public-domain databases by using BLAST.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Production of libraries of clones specific to the pathogenic species.

In a first experiment, three banks of N. meningitidis-specific clones were prepared by subtracting the chromosome of N. lactamica from meningococcal chromosomal DNA, cleaved with three restriction enzymes. Meningococcal DNA from strain Z2491 was cleaved with MboI (GATC, compatible with BamHI), MspI (CCGG, compatible with ClaI) and Tsp509I (AATT, compatible with EcoRI) and subjected to two rounds of subtraction by using DNA mixed from two strains of N. lactamica. The use of two strains of N. lactamica ensured that clones isolated were not taken as being N. meningitidis specific due to their absence from one particular strain of N. lactamica. The N. meningitidis-specific fragments were cloned into pBluescript. PCR products corresponding to the inserts, were radiolabelled and used in an initial screening by Southern blotting against chromosomal DNA from the meningococcus Z2491, the gonococcus FA1090, and the two strains of N. lactamica used for subtraction, each cleaved with ClaI. Of 237 clones initially isolated, 41 showed a double specificity for N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis and no reactivity with N. lactamica. These were chosen for further study.

Pathogen-specific DNA sequences should be equally attainable by the subtraction of N. lactamica DNA from gonococcal DNA. To test the completeness of the bank obtained by subtraction of N. lactamica from N. meningitidis and to increase the representativity of the subtractive clones, another three banks were produced as above, but this time subtracting the DNA of the two strains of N. lactamica from N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 DNA. Again, 20 of 83 clones showing reactivity with both N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae were kept.

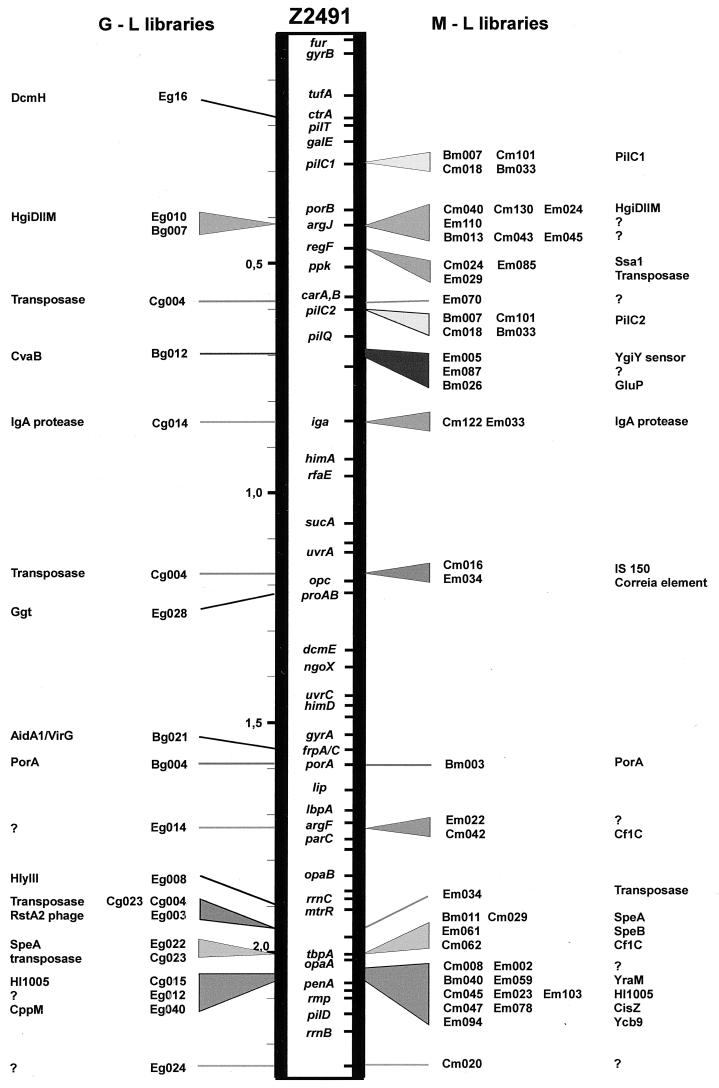

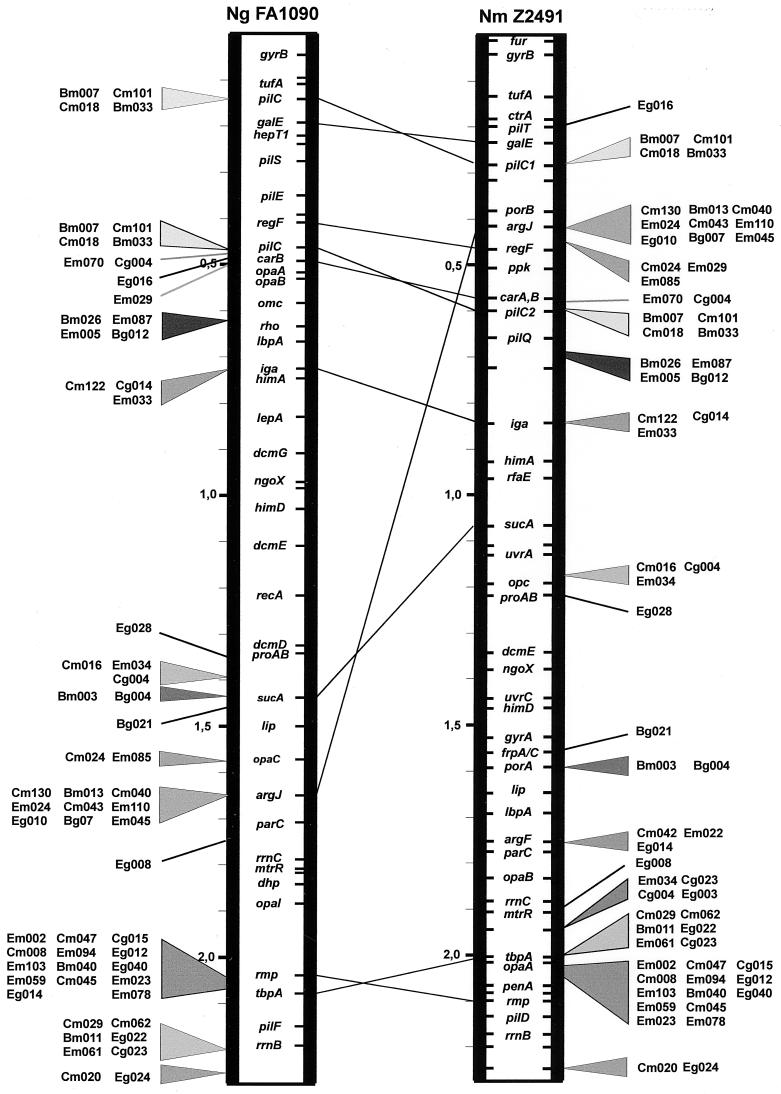

Clones derived from the subtraction involving meningococcal MboI fragments were designated Bm001, Bm002, etc.; those involving the MspI fragments were named Cm001, etc., and those involving the Tsp509I fragments were named Em001, etc.; the letters B, C, and E refer to the corresponding BamHI, ClaI, and EcoRI sites used for their cloning, respectively, and the letter m refers to the originating species N. meningitidis. Clones derived from N. gonorrhoeae were designated Bg001, Cg001, Eg001, etc. The positions of the 61 clones which were retained were determined in relation to the published macrorestriction maps of N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 (10) and N. meningitidis Z2491 (11) by probing Southern blots of chromosomal DNA cleaved with infrequently cutting restriction enzymes and subsequent comparison of the reactive bands with their published maps. In addition, the subtractive clones were sequenced, and, following BLAST searches of the partially sequenced chromosomes of N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 and N. meningitidis Z2491, the corresponding contigs were extracted from the genome sequence data of N. meningitidis Z2491 and analyzed to permit a tentative mapping of the subtractive clones on a smaller scale, relative to one another and to other defined genes. Figures 2 and 3 show the positions of the clones on the chromosome of N. meningitidis Z2491 and N. gonorrhoeae FA1090. In addition, in some cases the sequences surrounding these contigs were annotated and are shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 2.

Position of the pathogen-specific clones on the chromosomal map of N. meningitidis Z2491. Clones were mapped by Southern blotting and by comparison with the published partial genome sequence. Those derived from the N. gonorrhoeae-minus-N. lactamica subtraction are shown on the left (G-L libraries), and those from the N. meningitidis-minus-N. lactamica subtraction are shown on the right (M-L libraries). Clones from the two libraries derived from the same pathogen-specific region are marked with the same shading. Some clones were present in multiple copies (generally insertion sequences), and these are mapped only where they coincide with another identified locus.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the positions of the pathogen-specific clones on the chromosomes of N. gonorrhoeae FA1090 and N. meningitidis Z2491. The relative positions follow the lines of dislocation between the two chromosomes as previously described (11), with certain exceptions.

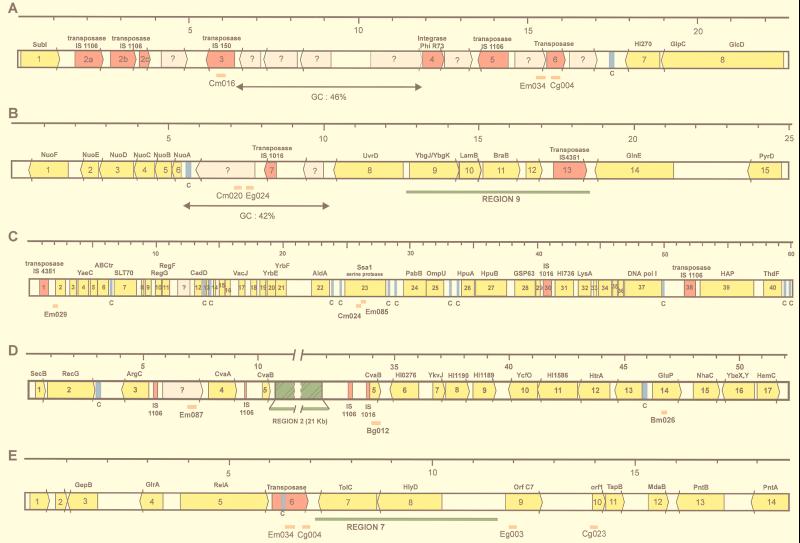

FIG. 4.

Genetic arrangement of the regions surrounding pathogen-specific clones. Genes are shown as arrows, yellow for those with homologies to proteins in the databases and grey for ORFs without significant homology. Transposases are shown in red, and Correia sequences (marked C) are shown in blue. The positions of the subtractive clones are shown as orange bars below the bar representing the genes. Regions previously discovered as being N. meningitidis specific are shown in green. A scale (in kilobases) is shown above the sequences. (A) The pathogen-specific clones flank a region of low G+C content (46%) containing several ORFs with no homologies to previously described genes. Homologies of surrounding ORFs, at the amino acid level, are as follows: 1, SubI, E. coli; 2a, 2b, 2c, transposase, IS1106, N. meningitidis; 3, ORF B, IS150, E. coli; 4, integrase, phage φR73; 5, transposase IS1106, N. meningitidis; 6, transposase, Synechocystis sp. (accession no. BAA10234); 7, (3′ end) HI0270, H. influenzae; 8, (5′ end) GlcD, Synechocystis sp. (3′ end) and GlpC, Helicobacter pylori. (B) The pathogen-specific clones correspond to a region of particularly low G+C content (42%), containing ORFs with no homologies. Homologies of surrounding ORFs, at the amino acid level, are as follows: 1, NuoF, Rickettsia prowazekii; 2, NuoE, R. prowazekii; 3, NuoD, R. prowazekii; 4, NuoC, Rhodobacter capsulatus; 5, NuoB, Rickettsia prowazekii; 6, NuoA, Sinorhizobium meliloti; 7, transposase, IS1016, H. influenzae; 8, UvrD, E. coli; 9, HI1731, H. influenzae; 10, LamB homolog, H. influenzae; 11, BraB homolog, H. influenzae; 12; MTH939, Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum; 13, transposase IS4351, N. meningitidis; 14, GlnE, E. coli; 15: PyrD, Salmonella typhimurium. (C) Homologies are as follows: 1, transposase IS4351, N. meningitidis; 2, ORF 288, Coxiella burnetii; 3, ORF 1244, Sphingomonas aromaticivorans; 4, YaeC, E. coli; 5, YaeE, E. coli; 6, ABC transporter (accession no. P30750), E. coli; 7, SLT70 transglycosylase (accession no. S56616), E. coli; 8, ribosomal protein S21, Burkholderia pseudomallei; 9, LporfX, Legionella pneumophila; 10, RegG, N. gonorrhoeae; 11, RegF, N. gonorrhoeae; 12, CadD, Staphylococcus aureus; 13, ribosomal protein L31, Haemophilus ducreyi; 14, putative acetyltransferase (accession no. CAA90593), Schizosaccharomyces pombe; 15, ResA, Bacillus subtilis; 16, YbaW, E. coli; 17, VacJ, Rickettsia prowazekii; 18, YrbC, E. coli; 19, HI1085, H. influenzae; 20, HI1086, H. influenzae; 21, HI1087, H. influenzae; 22, AldA, E. coli; 23, SsaI, Pasteurella haemolytica; 24, PabB, Helicobacter pylori; 25, OmpU, N. meningitidis; 26, HpuA, N. gonorrhoeae; 27, HpuB, N. meningitidis; 28, GroEL, N. gonorrhoeae; 29, GroES, N. gonorrhoeae; 30, transposase, IS1016, H. influenzae; 31, HI0736, H. influenzae; 32, LysA, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; 33, CyaY, E. coli; 34, HI1643, H. influenzae; 35, HI0931, H. influenzae; 36, YgaG, E. coli; 37, PolA, H. influenzae; 38, transposase IS1106, N. meningitidis; 39, Hap, H. influenzae; 40, ThdF, E. coli. (D) The subtractive clones flank the previously discovered N. meningitidis-specific region 2. Homologies are as follows: 1, SecB, E. coli; 2, RecG H. influenzae; 3, ArgC, Synechocystis sp.; 4, CvaA, plasmid ColV, E. coli; 5, CvaB, plasmid ColV, E. coli; 6, HI0276, H. influenzae; 7, YkvJ, Bacillus subtilis; 8, HI1190, H. influenzae; 9, HI1189, H. influenzae; 10, YcfO, 11, HI1586, H. influenzae; 12, MucD/HtrA serine protease homolog, Pseudomonas; 13, (5′ end) HI0489, H. influenzae, (3′ end) Nth endonuclease III, H. influenzae; 14, GluP, Brucella abortus; 15, NhaC, Bacillus firmus; 16, (5′ end) YbeY, E. coli, (3′ end) YbeX, E. coli; 17, HemC, Pseudomonas aeruginosa. (E) Homologies are as follows: 1, aq_1853, hypothetical protein, Aquifex aeolicus; 2, C09_orf404, Mycoplasma pneumoniae; 3, GepB, Dichelobacter nodosus; 4, GlrA, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans; 5, RelA, Vibrio sp.; 6, putative transposase (accession no. AAD10186), Streptococcus pneumoniae; 7, TolC, E. coli; 8, HlyD, E. coli; 9, ORF C7, Ralstonia solanacearum/RstA1, CTX phage, Vibrio cholerae; 10, ORF1, TspB, N. meningitidis; 11, TspB, N. meningitidis; 12, MdaB, H. influenzae; 13, PntB, H. influenzae; 14, PntA, E. coli.

It is noticeable that these clones are not scattered throughout the chromosomes of N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis but are clustered only in some regions (Fig. 2). Furthermore, comparing the maps of N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis (Fig. 3), it is seen that in general the relative positions of the clones on the two chromosomes follow the lines linking the previously mapped markers (11), whose positions have presumably changed following the chromosomal rearrangements which have occurred since the divergence of these two species. Of particular interest is the group of clones Em085, Cm024, and Em029, mapping near argJ and regF at 0.45 Mb and separated one from another by about 25 kb in N. meningitidis. In the gonococcus, clone Em029 and regF map around 0.45 Mb whereas the other clones map at about 1.65 Mb, indicating that a large-scale genetic rearrangement has occurred to separate these genes in N. gonorrhoeae or to bring them together in N. meningitidis.

It should be pointed out that the clones cluster in the same regions of the chromosome, whether they have been obtained by subtracting the N. lactamica genome from either N. meningitidis or N. gonorrhoeae, thus suggesting the completeness of the bank and validating the hypothesis that these clones designate regions which are specific for pathogenic neisseriae.

Functional classification of ORFs corresponding to the N. meningitidis- and N. gonorrhoeae-specific clones.

To get some insight into the function of these regions specific for pathogenic Neisseria species, the homologies at the protein levels of the ORFs corresponding to the resulting subtractive clones were noted after a BLAST search of the gene and protein databases. The results are summarized in Table 2, where the various homologies are divided into groups based on the functionality of the homologous proteins.

TABLE 2.

Homologies of the pathogen-specific clones

| Clone | Length (kb) | Positiona | Homology of ORFb | BLASTX significance | Inter- or intragenic | Accession no. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virulence-associated genes | |||||||

| Bm033 | 304 | 0.28 and 0.6 | PilC1 (pilus-associated protein), N. meningitidis (Y13020) | 0 | Coding | AF169442 | 38 |

| Bm007 | 204 | PilC1 | Coding | AF169438 | |||

| Cm018 | 276 | PilC1 | Coding | AF169446 | |||

| Cm101 | 585 | PilC1 | Coding | AF169457 | |||

| Cm024 | 600 | 0.45 | Ssa1 (serotype-specific antigen), Pasteurella haemolytica (U07788) | 1e-7 | Coding | AF169448 | 18 |

| Em085 | 286 | Ssa1 | Coding | AF169473 | |||

| Em005 | 171 | 0.67 | YgiY (putative sensor/kinase protien), E. coli (P40719) | 2e-26 | Coding | AF169461 | 6 |

| IrlS (two-component regulatory system protein) Burkholderia pseudomallei (AF005358) | 4e-19 | 24 | |||||

| Cg014 | 156 | 0.85 | Iga (IgA protease), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (X04835) | 0 | Coding | AF169423 | 36 |

| Cm122 | 311 | Iga | Coding | AF169458 | |||

| Em033 | 276 | Iga | Coding | AF169466 | |||

| Bg021 | 444 | 1.55 | AidA-1 (putative adhesin), E. coli (D90793) | 2e-23 | Coding/inergenic | AF169420 | 1 |

| VirG (virulence-associated protein), Shigella flexnerii (M22802) | 4e-23 | 32 | |||||

| Eg008 | 302 | 1.9 | HlyIII (hemolysin III.), Bacillus cereus (P54176) | 3e-25 | Coding/intergenic | AF169427 | 4 |

| DNA modification, phage-related, and insertion sequences | |||||||

| Eg016 | 326 | 0.18 | DcmH (cytosine-specific methyltransferase), N. gonorrhoeae (AF001598) | 1e-148 | Coding | AF169431 | 20 |

| Cm130 | 851 | 0.42 | HgiDIIM (cytosine-specific methyltransferase), Herpetosyphon giganteus (JT0594) | 7e-49 | Coding | AF169459 | 13 |

| Em024 | 271 | HgiDIIM | Coding | AF169464 | |||

| Eg010 | 271 | HgiDIIM | Coding | AF169428 | |||

| Cm040 | 269 | HgiDIIM | Coding/intergenic | AF169451 | |||

| Em029 | 268 | 0.45 | Transposase in insertion sequence, Aeromonas salmonicida (L27157) | 1e-10 | Coding/intergenic | AF169465 | 21 |

| Cm016 | 280 | 1.17 | Hypothetical protein in insertion sequence IS150-like, N. gonorrhoeae (L36381) | 2e-88 | Coding | AF169445 | 37 |

| Cm042 | 203 | 1.75 | Hypothetical protein phage Cf1c), Xanthomonas campestris (M57538) | 1e-19 | Coding | AF169452 | 31 |

| Eg003 | 364 | 1.95 | RstA2 (phage CTX), Vibrio cholerae (U83796) | 7e-8 | Coding | AF169426 | 45 |

| Cg011 | 315 | Multiple | ORF1 (transposase, insertion sequence IS1106 (partial; DNA homology), N. meningitidis | - | Coding/intergenic | AF169422 | 28 |

| Cm034 | 381 | Multiple | Insertion sequence IS1016, Haemophilus influenzae (X58176) | 4e-10 | ? | AF169450 | 30 |

| Cg004 | 358 | Multiple | Hypothetical transposase, Synechocystis sp. (D90913, g1653459) | 2e-18 | Coding/intergenic | AF169421 | 25 |

| Em034 | (365)c | Multiple | Correia repetitive element (partial; DNA homology), N. gonorrhoeae (M19676) | 8e-80 | Coding/intergenic | AF169467 | 8 |

| Metabolic and transporter genes | |||||||

| Bg012 | 363 | 0.7 | CvaB (ATP-binding colicin secretion protein), E. coli (U47048) | 8e-16 | Coding | AF169419 | 17 |

| Bm026 | 181 | 0.7 | GluP (glucose/galactose transporter), Brucella abortus (Q44623) | 1e-104 | Coding | AF169441 | 14 |

| Eg028 | 251 | 1.22 | Ggt (γ-glutamyltranspeptidase), Bacillus subtilis (P54422) | 2e-9 | Coding | AF169435 | 48 |

| Bm003 | (360)c | 1.6 | PorA (class 1 porin), N. meningitidis | 0 | Coding | AF169437 | 5 |

| Bg004 | 363 | PorA | Coding | AF169417 | |||

| Cm029 | 248 | 2.0 | SpeA1 (arginine decarboxylase), E. coli (M31770) | 1e-138 | Coding | AF169449 | 34 |

| Bm011 | 347 | SpeA1 | Coding | AF169439 | |||

| Eg022 | 281 | SpeA1 | Coding/intergenic | AF169433 | |||

| Em061 | 261 | SpeB (agmatinase), E. coli (M32363) | 1e-134 | Coding | AF169470 | 43 | |

| Cm062 | 212 | 2.0 | YflS (hypothetical protein), B. subtilis (D86417, g2443241) | 1e-130 | Coding | AF169456 | 49 |

| SODiT1 (dicarboxylate translocator), Spinacia oleracea (U13238) | 3e-97 | 46 | |||||

| Eg040 | 276 | 2.04 | CppM (putative CPEP phosphomutase), E. coli (P77541) | 8e-91 | Coding | AF169436 | 12 |

| Em078 | 308 | CisZ (citrate synthase), E. coli (P31660) | 8e-28 | Coding | AF169472 | 35 | |

| Cm047 | 224 | CisZ | Coding | AF169455 | |||

| Genes of unknown function | |||||||

| Cg023 | 470 | 2.0 | Hypothetical protein ‘ORF1’, N. meningitidis (AJ010115) | 6e-23 | Coding | AF169425 | 47 |

| Em103 | (375)c | 2.04 | HI1005 (hypothetical protein), H. influenzae (U32781) | 3e-56 | Coding | AF169476 | 16 |

| Cm045 | 206 | HI1005 | Coding | AF169454 | |||

| Cg015 | 267 | HI1005 | Coding | AF169424 | |||

| Em023 | 273 | HI1005 | Coding | AF169463 | |||

| Em094 | 196 | 2.04 | Ycb9 (hypothetical protein), Pseudomonas denitrificans | 6e-9 | Coding | AF169475 | 9 |

| Bm040 | 243 | 2.04 | YraM (hypothetical protein), Bacillus subtilis (U93875, g1934631) | 1e-50 | Coding | AF169443 | 42 |

| Em059 | (515)c | YraM | Coding | AF169469 | |||

| Genes with no homologies | |||||||

| Em110 | 217 | 0.6 | None | Coding | AF169477 | ||

| Bm013 | 349 | None | Coding | AF169440 | |||

| Cm043 | 229 | None | Coding | AF169453 | |||

| Bg007 | 400 | None | Coding | AF169418 | |||

| Em045 | 260 | None | ? | AF169468 | |||

| Em070 | 323 | 0.6 | ? | AF169471 | |||

| Em087 | 238 | 0.7 | None | Coding | AF169474 | ||

| Eg014 | 293 | 1.75 | None | Intergenic | AF169430 | ||

| Cm008 | 236 | 2.05 | None | Coding | AF169444 | ||

| Eg012 | 309 | None | Coding | AF169429 | |||

| Em002 | 308 | None | Coding | AF169460 | |||

| Cm020 | 354 | 2.25 | None | Coding | AF169447 | ||

| Eg024 | 345 | None | Coding | AF169434 | |||

| Em022 | (305)c | Multiple | None | ? | AF169462 |

Positions were determined by comparison of the pattern of reactivity on Southern blots with those of the macrorestriction map of N. meningitidis Z2491 (11) and by analysis of contigs from the genome-sequencing projects which contained the clones. The position is given in megabases, according to reference 11.

Homologous proteins or ORFs are those giving the best BLASTX scores, using the corresponding ORF or intergenic region as query sequence.

Sizes of clones in parentheses are approximate, where the sequence information was not considered sufficiently reliable to give an exact number of bases.

(i) Sequences having homologies to known virulence factors.

A few clones were located in sequences containing genes whose function has been established as playing a role in the colonization and survival of the port of entry, such as the IgA protease Iga (23, 29), and the pilus-associated adhesion molecule PilC (40). The fact that these genes are N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae restricted confirms the original hypothesis that these regions may encode virulence factors which are important in the first step of pathogenesis, i.e., the colonization of the epithelium and survival at the port of entry. Furthermore, it suggests that the other, as yet uninvestigated potential virulence factors (Table 2) which have been identified on the basis of homology could be involved in common steps of the disease.

(ii) Sequences related to DNA modifications and rearrangements, insertion sequences, and viral recombinases.

The sequences related to DNA modifications and rearrangements, insertion sequences, and viral recombinases include methyltransferases DcmH and HgiDIIM, transposases from IS1106 of N. meningitidis, IS18 of Acinetobacter, and IS150-like of N. gonorrhoeae, Synechocystis, and Aeromonas salmonicida, the Correia sequences from N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae, and proteins from phages Cf1c of Xanthomonas campestris and CTX of Vibrio cholerae. Hence a relatively large number of sequences identified were related to DNA modifications, insertion sequences or transposons, and phages. In the absence of further evidence, they may be taken to be clonal in their distribution between the species, reflecting the closer relationship between the gonococcus and the meningococcus rather than genetic differences maintained by natural selection.

(iii) Sequences with homologies to proteins involved in metabolic pathways or transporters.

The fact that metabolic genes may be specific for pathogenic Neisseria species could be related to the specific environment they both have to encounter. The outer membrane porin PorA (5) belongs to this category. PorA is found only in N. meningitidis, and the gene was initially thought to be N. meningitidis specific; however, in N. gonorrhoeae the porA gene is not expressed, being a pseudogene (15).

(iv) Sequences with weak homologies and homologies to hypothetical proteins typically derived from genome-sequencing projects.

The significance of sequences with weak homologies and homologies to hypothetical proteins remains to be investigated.

Genetic arrangement of the pathogen-specific regions.

The origin of the pathogenic Neisseria sequences is another important question. In several bacterial species, which contain more or less virulent variants (for example, E. coli, Helicobacter pylori, Salmonella typhimurium, and Yersinia enterocolitica), genes specifying the attributes of increased pathogenic potential are clustered in so-called pathogenicity islands (PAIs) (22). PAIs are usually large (50 to 200 kb), often having a G+C content different from that of the host chromosome. None of the regions had the characteristics typical of PAIs, of bacteriophages, or of compound transposons, structures which are associated with the introduction into bacterial chromosomes of foreign DNA coding for virulence factors. Several of the regions were, however, of particularly low G+C content (Fig. 4) and were associated with transposase and integrase genes, suggesting that at some time in the genetic history of the species, the regions were the result of recombinational events with DNA from other species. For example, the region containing Cm016, Em024, and Cg004 at 1.17 Mb (Fig. 4A) contains a region with a particularly low G+C content (46%, compared with 52% for the chromosome in general) with no homologies to genes in the databases, surrounded by ORFs with homologies to sequences encoding transposases and a phage integrase, and may well represent DNA, as yet unknown, acquired from another organism. A similar situation is seen with the region corresponding to clones Cm020 and Eg024 (Fig. 4B).

The region between the clones Em085 and Cm024 and the regF gene is the site of one of the large chromosomal translocations discovered by Dempsey et al. (11). The surrounding region (Fig. 4C) contains several copies of the Correia sequence, singly or in pairs, and these sequences are likely to be important in intrachromosomal rearrangements, as has been suggested previously (28).

Another striking feature of these regions is the association of many of the clones with the previously described N. meningitidis-specific regions (44). This suggests that previously discovered N. meningitidis-specific islands, at least in regions 2 and 7 (Fig. 4D and E), have inserted into preexisting pathogen-specific sequences. Together, these data suggest that these N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae regions correspond to islands of pathogen-specific DNA, as was seen to be the case in the N. meningitidis-N. gonorrhoeae subtraction.

Conclusion.

Our data demonstrate that even though N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae display very different pathogeneses, they have regions of their chromosomes in common which are not found in the nonpathogenic N. lactamica and which are probably involved in common aspects of their life cycle, i.e., colonization and survival at the port of entry. The subtractive technique has enabled us to identify novel candidate genes and regions involved in these common steps. A further understanding of these steps will require systematic mutagenesis of the genes located in these regions. The postgenomic era has begun for many bacterial pathogens; our data have confirmed that the technique of genomic subtraction has the potential to pinpoint regions of chromosome that are most likely to be involved in the differential virulence of bacterial pathogens. This technique has therefore the potential to identify from among the thousands of ORFs brought to light by genome sequencing a number of potential targets for new therapies and vaccine production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the INSERM, the Université Paris V René Descartes and the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

Thanks are due to N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae sequencing teams at the Sanger Centre and the University of Oklahoma, who made their sequences publicly available throughout the progress of the genome projects.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiba H, Baba T, Fujita K, Hayashi K, Inada T, Isono K, Itoh T, Kasai H, Kashimoto K, Kimura S, Kitakawa M, Kitagawa M, Makino K, Miki T, Mizobuchi K, Mori H, Mori T, Motomura K, Nakade S, Nakamura Y, Nashimoto H, Nishio Y, Oshima T, Saito N, Sampei G, Seki Y, Sivasundaram S, Tagami H, Takeda J, Takemoto K, Takeuchi Y, Wada C, Yamamoto Y, Horiuchi T. A 570-kb DNA sequence of the Escherichia coli K-12 genome corresponding to the 28.0-40.1 min region on the linkage map. DNA Res. 1996;3:363–377. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.6.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of potein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley-Interscience; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baida G E, Kuzmin N P. Cloning and primary structure of a new hemolysin gene from Bacillus cereus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1264:151–154. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00150-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barlow A K, Heckels J E, Clarke I N. The class 1 outer membrane protein of Neisseria meningitidis: gene sequence and structural and immunological similarities to gonococcal porins. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blattner, F. R., G. I. Plunkett, G. F. Mayhew, N. T. Perna, and F. D. Glasner. 1997. Direct submission to EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ data banks.

- 7.Church G M, Gilbert W. Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correia F F, Inouye S, Inouye M. A family of small repeated elements with some transposon-like properties in the genome of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:12194–12198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crouzet J, Levy-Schil S, Cameron B, Cauchois L, Rigault S, Rouyez M-C, Blanche F, Debussche L, Thibaut D. Nucleotide sequence and genetic analysis of a 13.1-kilobase-pair Pseudomonas denitrificans DNA fragment containing five COB genes and identification of structural genes encoding COB(I)alamin adenosyltransferase, cobyric acid synthase, and bifunctional cobin. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6074–6087. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.19.6074-6087.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dempsey J F, Litaker W, Madhure A, Snodgrass T L, Cannon J G. Physical map of the chromosome of Neisseria gonorrhoeae FA1090 with locations of genetic markers, including opa and pil genes. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5476–5486. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5476-5486.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dempsey J F, Wallace A B, Cannon J G. The physical map of the chromosome of a serogroup A strain of Neisseria meningitidis shows complex rearrangements relative to the chromosomes of the two mapped strains of the closely related species N. gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6390–6400. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6390-6400.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan, M., E. Allen, R. Araujo, A. M. Aparico, E. Chung, K. Davis, N. Federspeil, R. Hyman, S. Kalman, C. Komp, O. Kurdi, H. Lew, D. Lin, A. Namath, P. Oefner, D. Roberts, S. Schramm, and R. W. Davis. 1996. Direct submission to EMBL/GenBan/DDJB data banks.

- 13.Dusterhoft A, Kroger M. Cloning, sequence and characterization of m5C-methyltransferase-encoding gene, hgiDIIM (GTCGAC), from Herpetosiphon giganteus strain Hpa2. Gene. 1991;106:87–92. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90569-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Essenberg, R., and C. Candler. 1996. Direct submission to EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ data banks.

- 15.Feavers I M, Maiden M C. A gonococcal porA pseudogene: implications for understanding the evolution and pathogenicity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:647–656. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J-F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, Mckenney K, Sutton G, Fitzhugh W, Fields C A, Gocayne J D, Scott J D, Shirley R, Liu L-I, Glodek A, Kelley J M, Weidman J F, Phillips C A, Spriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton M D, Utterback T R, Hanna M C, Nguyen D T, Saudek D M, Brandon R C, Fine L D, Fritchman J L, Fuhrmann J L, Geoghagen N S M, Gnehm C L, Mcdonald L A, Small K V, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Venter J C. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilson L, Mahanty H K, Kolter R. Genetic analysis of an MDR-like export system: the secretion of colicin V. EMBO J. 1990;9:3875–3894. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez C T, Maheswaran S K, Murtaugh M P. Pasteurella haemolytica serotype 2 contains the gene for a noncapsular serotype 1-specific antigen. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1340–1348. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1340-1348.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guibourdenche M, Popoff J Y, Riou J Y. Deoxyribonucleic acid relatedness among Neisseria gonorrhoeae, N. meningitidis, N. lactamica, N. cinerea and “Neisseria polysaccharea”. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol (Paris) 1986;137B:177–185. doi: 10.1016/s0769-2609(86)80106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunn J S, Stein D C. The Neisseria gonorrhoeae S. NgoVIII restriction/modification system: a type IIs system homologous to the Haemophilus parahaemolyticus HphI restriction/modification system. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4147–4152. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.20.4147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gustafson C E, Chu S, Trust T J. Mutagenesis of the paracrystalline surface protein array of Aeromonas salmonicida by endogenous insertion elements. J Mol Biol. 1994;237:452–463. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hacker J, Blum-Oehler G, Mühldorfer I, Tschäpe H. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1089–1097. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3101672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halter R, Pohlner J, Meyer T F. IgA protease of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: isolation and characterization of the gene and its extracellular product. EMBO J. 1984;3:1595–1601. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones A L, DeShazer D, Woods D E. Identification and characterization of a two-component regulatory system involved in invasion of eukaryotic cells and heavy-metal resistance in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4972–4977. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.4972-4977.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sugiura M, Sasamoto S, Kimura T, Hosouchi T, Matsuno A, Muraki A, Nakazaki N, Naruo K, Okumura S, Shimpo S, Takeuchi C, Wada T, Watanabe A, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 1996;3:109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kellogg D S J, Peacock W L, Deacon W E, Brown L, Pirkle C I. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. I. Virulence genetically linked to clonal variation. J Bacteriol. 1963;85:1274–1279. doi: 10.1128/jb.85.6.1274-1279.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kingsbury D T. Deoxyribonucleic acid homologies among species of the genus Neisseria. J Bacteriol. 1967;94:870–874. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.4.870-874.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knight A I, Ni H, Cartwright K A V, McFadden J J. Identification and characterization of a novel insertion sequence, IS1106, downstream of the porA gene in B15 Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1565–1573. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koomey J M, Gill R E, Falkow S. Genetic and biochemical analysis of gonococcal IgA1 protease: cloning in Escherichia coli and construction of mutants of gonococci that fail to produce the activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:7881–7885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.24.7881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kroll J S, Loynds B M, Moxon E R. The Haemophilus influenzae capsulation gene cluster: a compound transposon. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1549–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuo T-T, Tan M-S, Su M-T, Yang M K. Complete nucleotide sequence of filamentous phage Cf1c from Xanthomonas campestris pv. citri. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:2498–2498. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.9.2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lett M-C, Sasakawa C, Okada N, Sakai T, Makino S, Yamada M, Komatsu K, Yoshikawa M. virG, a plasmid-coded virulence gene of Shigella flexneri: identification of the VirG protein and determination of the complete coding sequence. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:353–359. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.353-359.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lisitsyn N, Lisitsyn N, Wigler M. Cloning the differences between two complex genomes. Science. 1993;259:946–951. doi: 10.1126/science.8438152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore R C, Boyle S M. Nucleotide sequence and analysis of the speA gene encoding biosynthetic arginine decarboxylase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4631–4640. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4631-4640.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patton A J, Hough D W, Towner P, Danson M J. Does Escherichia coli possess a second citrate synthase gene? Eur J Biochem. 1993;214:75–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pohlner J, Halter R, Beyreuther K, Meyer T F. Gene structure and extracellular secretion of Neisseria gonorrhoeae IgA protease. Nature. 1987;325:458–462. doi: 10.1038/325458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Porcella, S. F., R. J. Belland, and R. C. Judd. 1996. Direct submission to EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ data banks.

- 38.Rahman M, Kallstrom H, Normark S, Jonsson A B. PilC of pathogenic Neisseria is associated with the bacterial cell surface. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:11–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4601823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rossau R, Vandenbussche G, Thielemans S, Segers P, Grosch H, Gothe E, Mannheim W, de Ley J. Ribosomal ribonucleic acid cistron similarities and deoxyribonucleic acid homologies of Neisseria, Kingella, Eikenella, Simonsiella, Alysiella, and Centers for Disease Control groups EF-4 and M-5 in the emended family Neisseriaceae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1989;39:185–198. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rudel T, Schuerpflug I, Meyer T F. Neisseria PilC protein identified as a type 4 pilus tip-located adhesin. Nature. 1995;373:357–359. doi: 10.1038/373357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sorokin A, Bolotin A, Purnelle B, Hilbert H, Lauber J, Dusterhoft A, Ehrlich S D. Sequence of the Bacillus subtilis genome region in the vicinity of the lev operon reveals two new extracytoplasmic function RNA polymerase sigma factors SigV and SigZ. Microbiology. 1997;143:2939–2943. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-9-2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szumanski M B, Boyle S M. Influence of cyclic AMP, agmatine, and a novel protein encoded by a flanking gene on speB (agmatine ureohydrolase) in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:758–764. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.758-764.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tinsley C R, Nassif X. Analysis of the genetic differences between Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, two closely-related bacteria expressing two different pathogenicities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11109–11114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44a.University of Oklahoma. 1998. Sequences. [Online.] http://www.genome.ou.edu/gono.html. [16 December 1998, last date accessed.]

- 45.Waldor M K, Rubin E J, Pearson G D, Kimsey H, Mekalanos J J. Regulation, replication, and integration functions of the Vibrio cholerae CTXphi are encoded by region RS2. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:917–926. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3911758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weber, A., E. Menzlaff, B. Arbinger, M. Gutensohn, C. Eckerskorn, and U. I. Flugge. 2621–2627. The 2-oxoglutarate/malate translocator of chloroplast envelope membranes: molecular cloning of a transporter containing a 12-helix motif and expression of the functional protein in yeast cells. Biochemistry 34:2621–2627. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46a.Wellcome Trust/Sanger Centre. 1999. Sequences. [Online.] http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/N_meningitidis. [25 January 1999, last date accessed.]

- 47.Wooldridge, K. G., G. Kizil, M. Jones, L. A. De-Netto, I. Todd, and D. A. A. Ala Aldeen. 1998. Unpublished data.

- 48.Xu K, Strauch M A. Identification, sequence, and expression of the gene encoding gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4319–4322. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4319-4322.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamamoto H, Uchiyama S, Nugroho F A, Sekiguchi J. Cloning and sequencing of 35.7 kb in the 70 degree-73 degree region of the Bacillus subtilis genome reveal genes for a new two-component system, three spore germination proteins, an iron uptake system and a general stress response protein. Gene. 1997;194:191–199. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]