Abstract

Nano-enabled agriculture is a topic of intense research interest. However, our knowledge of how nanoparticles enter plants, plant cells, and organelles is still insufficient. Here, we discuss the barriers that limit the efficient delivery of nanoparticles at the whole-plant and single-cell levels. Some commonly overlooked factors, such as light conditions and surface tension of applied nano-formulations, are discussed. Knowledge gaps regarding plant cell uptake of nanoparticles, such as the effect of electrochemical gradients across organelle membranes on nanoparticle delivery, are analyzed and discussed. The importance of controlling factors such as size, charge, stability, and dispersibility when properly designing nanomaterials for plants is outlined. We mainly focus on understanding how nanoparticles travel across barriers in plants and plant cells and the major factors that limit the efficient delivery of nanoparticles, promoting a better understanding of nanoparticle–plant interactions. We also provide suggestions on the design of nanomaterials for nano-enabled agriculture.

Keywords: barriers, cell membranes, cell wall, efficient delivery, electrochemical gradients, nanoparticles

A better understanding of how nanoparticles enter plants, plant cells, and organelles is important for facilitating the development of nano-enabled agriculture. This review discusses how nanoparticles travel across barriers in plants and plant cells and the main factors that limit the efficient delivery of nanoparticles in plants. Some suggestions about the proper design of nanomaterials for nano-enabled agriculture are provided in this review.

Introduction

Agriculture faces many challenges from abiotic and biotic stress. With the population predicted to be over 9 billion in 2050 (Lee, 2011), increased food demand necessitates a 60% increase in agricultural production from the 2005–2007 level (van Ittersum et al., 2016). However, breeding programs by cereal crop growers do not meet expectations. Application of high amounts of fertilizers and pesticides has reached a plateau in terms of improving agricultural production and causes problems such as environmental pollution. New approaches that can help to maintain plant performance under stress conditions should be discussed and encouraged.

Plant nanobiotechnology is a currently emerging field in agricultural research (White and Gardea-Torresdey, 2018; Pulizzi, 2019). It has shown potential for improving plant performance under biotic stress (e.g., pathogens and pests) and abiotic stress (e.g., salinity, drought, and temperature) (Zhao et al., 2020). A common question is why nanobiotechnology, or more specifically, nanoproducts, should be used in agriculture. First, nanomaterials (with at least one dimension less than 100 nm; Xia et al., 2003) are not new to nature, including plants. For example, microorganisms such as yeast strains are able to form silver nanoparticles from medium containing silver chemicals such as AgNO3 (Meenal et al., 2003; Eugenio et al., 2016; Singh et al., 2016). Alfalfa plants grown in silver-rich solid medium can form silver nanoparticles in their shoots (Gardea-Torresdey et al., 2003). Second, one bottleneck in agricultural production is that applying increasingly high amounts of agrochemicals does not result in yield increases and may even result in yield decreases (Wu and Ge, 2019). Climate change exacerbates the frequency of plant abiotic and biotic stress, which adds another challenge to agricultural production. Stress conditions lead to economic losses in agricultural production. For example, salinity (Shabala et al., 2014) and drought (Suzuki et al., 2014) cause billions of dollars of losses annually. We need more efficient and environmentally friendly ways to protect plants from stress conditions, especially abiotic stresses. For example, salinity is a worldwide environmental constraint that limits agricultural production. Breeding salt-tolerant crops is a long-term process, and flushing soil with fresh water is not affordable in many areas, especially areas that lack water resources. New approaches, such as plant nanobiotechnology, that can enable better tolerance to plant stresses (e.g., salinity) (Li et al., 2022a) could be an alternative way to promote sustainable agriculture and secure the food supply. Nanoparticles (i.e., CeO2, SeNP, TiO2, and AgNP) improve salinity stress tolerance in barley (Karami and Sepehri, 2018), Brassica napus (Rossi et al., 2016, 2017; Zhao et al., 2019), potato (Mahmoud et al., 2020), tomato (Almutairi, 2016; Morales-Espinoza et al., 2019), and broccoli (Martínez-Ballesta et al., 2016), suggesting that plant nanobiotechnology is an alternative means of improving crop tolerance to stress (e.g., salinity).

Nanomaterials have a larger surface area than the same amount of bulk materials (a higher surface area-to-volume ratio and probably more reaction sites) (Alavi and Rai, 2019) and can be less toxic to plants than commercial products. For example, metal-based engineered nanomaterials such as CuO nanoparticles are often less toxic than their ionic counterparts at equivalent doses (Gao et al., 2018). This effect might be associated with the dissolution rate and possibly the reactivity of nanoparticles. A previous study has shown that the dissolution rate of nanoceria (cerium oxide nanoparticles) in carboxylic acid solution is proportional to the nanoparticle surface area (Grulke et al., 2019). Zn2+ concentrations from dissolved ZnO nanoparticles were significantly higher for 9-nm particles than for 40-nm particles (Lv et al., 2021). Nanoproducts can be used as an adjunct component to improve the efficiency of commercial products (Kah and Hofmann, 2014). Compared with the limits on their commercial counterparts (mostly in chemical form), nanoparticles can allow researchers to perform easy surface conjugation, imparting numerous possibilities for functionalizing nanoparticles with designed properties. This makes it possible to design and optimize nanoparticles to address issues in plant science and agriculture in real time and more efficiently compared with conventional means of exploring new chemicals. Engineered nanomaterials have been proposed as ideal platforms for leading the agri-technology revolution (Lowry et al., 2019). For example, efforts have been made to deliver genetic materials such as DNA (Torney et al., 2007; Lakshmanan et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2017a; Demirer et al., 2019; Kwak et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022a), RNA (Mitter et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019a, 2022; Demirer et al., 2020), and proteins (Ng et al., 2016; Santana et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Watanabe et al., 2021) to plants. Using a plant nanobionics approach, bomb-detecting plants (plants as detectors of explosive chemicals) (Wong et al., 2017), light-emitting plants (Kwak et al., 2017), and smart plant sensors (Giraldo et al., 2019) have been developed. These examples could provide ideas to the agricultural research community for manipulating nanomaterials to achieve specific production goals. Nanobiotechnology could play an important role in enabling efficient and sustainable agricultural production.

To facilitate the use of plant nanobiotechnology in agriculture, information on how nanoparticles enter plants is necessary. However, our knowledge of this topic is still insufficient. Investigating the details of what happens at the initial interface between nanoparticles and plants and evaluating the factors that affect this process will provide clues to better understand the biological role of nanoparticles and to better design nanoparticles on demand. Phloem and xylem are involved in the transport of nanoparticles to the whole plant, and apoplastic and symplastic transport play a role in nanoparticle distribution in plants. Recent reviews (Su et al., 2019; Avellan et al., 2021; Hong et al., 2021) discuss these topics in detail. Comparisons of different nanomaterials and delivery systems, important factors that affect delivery, and locations that nanoparticles (NPs) can reach, together with efficiency analyses, can be found in a previous review (Su et al., 2019). In this review, we have tried to focus on discussing and analyzing the gaps in our knowledge of how NPs travel across barriers in plants and plant cells and the main factors that affect the efficient delivery of NPs in plants.

Interfacing NPs to plants: Factors affecting efficient delivery of NPs

Efficient foliar delivery of NPs: The importance of stomata, adhesion ability, sieve plate pores, phloem loading, light conditions, and surface tension of applied formulations

Regarding the interaction between NPs and leaf cells, we argue that NPs can directly interface with most leaf cells via stomata or cuticular pathways. The reported average radii of the pores in waxy hydrophobic cuticles are usually smaller than 2.4 nm (Schonherr, 2006; Eichert and Goldbach, 2008), limiting the transport of large NPs. Previous studies have shown that NPs up to 50 nm enter plant leaves via cuticular uptake pathways (Nadiminti et al., 2013; Avellan et al., 2019). It has been suggested that cuticle composition and NP surface properties may affect the efficiency of cuticular NP uptake (Avellan et al., 2019). Compared with the cuticular pathway, which applies more to small NPs, the stomatal pathway is the main route for plant foliar uptake of NPs. Stomata, which are located in the leaf epidermis, are formed by two guard cells and are important for gas exchange during photosynthesis. The length and width of stomata are usually at the scale of micrometers, with variations among plant species. For example, stomatal length and width in rice are about 30 μm and 15 μm, respectively (Yu et al., 2013). In barley, stomatal width is around 4 μm, and length is about 27 μm (Liu et al., 2014). In 11 rainforest species, stomatal length ranged from 17–24 μm, and stomatal width was about 12–18 μm (Kardiman and Ræbild, 2018). The pore area of stomata or stomatal size in the open state is usually a few hundred square micrometers (Yu et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014; Kardiman and Ræbild, 2018), which is large enough to allow NPs to pass through. Avoiding stomatal closure is important for the efficient delivery of foliar NPs in plants. However, few studies have focused on the effect of NPs on stomatal properties, hampering our understanding of the interaction between NPs and stomata. Stomatal density on the abaxial and adaxial sides of a leaf is usually different (Pathare et al., 2020).

Besides the pore sizes of stomata and leaf cuticles, the adhesion ability of NPs on leaves is another factor that may affect the efficient delivery of foliar NPs into plants. Large NPs are always more easily washed off than small ones (Avellan et al., 2019; Kah et al., 2019). Zeta potential does not seem to play as important a role as size in NP adhesion to leaves. For example, 50-nm citrate-gold NPs (AuNPs) (−60 mV) and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)-AuNPs (−31 mV) were almost completely washed off from wheat leaves, whereas 10-nm PVP-AuNPs (−51 mV) showed significantly greater leaf adhesion ability than 10-nm citrate-AuNPs (−48 mV) (Avellan et al., 2019). Other factors that affect leaf adhesion of NPs may be associated with hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity. Because of the existence of surface waxes, most leaf surfaces are hydrophobic or only moderately hydrophilic (Burkhardt et al., 2012). Thus, theoretically, NPs with stronger hydrophobicity than hydrophilicity might show greater leaf adhesion. However, in terms of efficient translocation of NPs in plants, NPs with greater hydrophilicity than hydrophobicity might be more favorable. A balance between hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity should be considered when designing agro-nanomaterials. It has been proposed that better adhesion of PVP-AuNPs than citrate-AuNPs on wheat leaves could be associated with enhanced hydrophobic interactions between amphiphilic surfaces and lipophilic cuticles (Avellan et al., 2019). Foliar surface free energy (SFE) has been proposed as another mechanism that affects NP adhesion on leaves. Compared with high-SFE plants, low-SFE plants show a significantly greater ability to adhere and retain platinum NPs (Kranjc et al., 2018). For more information on the leaf adhesion ability of NPs, refer to previous papers (Grillo et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022b). Controlling the size and charge of NPs could impart a better ability to travel across leaf barriers. In cotton, foliar hydrophilic NPs of 2 nm and −44 mV can be efficiently translocated into mesophyll chloroplasts, but NPs of 18 nm and −46 mV cannot penetrate the leaf and therefore remain on the leaf surface (Hu et al., 2020). Coating NPs with proteins can enable their targeted delivery to plant structures. Coating of AuNPs with bovine serum albumin protein and the anti-pectic polysaccharide (α-1,5-arabinan) antibody LM6-M, which has an affinity for functional groups unique to stomata, enables targeted delivery of AuNPs to trichrome hairs and stomata, respectively, on broad bean leaves (Spielman-Sun et al., 2020).

After passing through the leaf epidermis via stomata or the cuticular pathway, foliar NPs are mainly distributed in plants by phloem transport. Our knowledge of how foliar NPs are transported to the phloem is still insufficient. After passing through the barrier of the leaf epidermis, NPs can reach the phloem by two main routes: 1) from mesophyll cells (palisade and spongy mesophyll cells) to the phloem, and 2) directly through the spaces between mesophyll cells to the phloem. For route 1, plasmodesmata between mesophyll and bundle sheath cells (Danila et al., 2016) could be the main pathway that allows NP transport from mesophyll cells to bundle sheath cells and then to the phloem. For route 2, passage of NPs through the cell walls of bundle sheath cells to reach the phloem can be envisaged. Compared with C3 plants, C4 plants may favor route 1 because of the difference in anatomical structure regarding whether mesophyll cells are assembled on the bundle sheath. Phloem pressure has long been regarded as an important driving force for phloem transport. However, it has been argued that phloem pressure does not scale to plant size and that the pressure gradient is difficult or impossible to detect in smaller plants (Turgeon, 2010).

Another major factor that limits the phloem transport of nanomaterials may be the size of the sieve plate pores in the phloem. Particularly large pores with diameters above 10 μm have been observed in gourds (Cucurbita sp., 10.3 μm), the genus Tetracera (13.1 μm), and the tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima, 14.3 μm), whereas many other species have pores of around or less than 1 μm (Lothar and Helariutta, 2019). Pore size, sieve plate diameter, and length of the individual sieve elements determine the conductivity of the sieve tube. For example, the size of sieve plate pores in tomato pedicels is about 150–600 nm (Bussie, 2014), which is large enough to allow loading of NPs into the phloem. Clearly, NP size is one of the main factors that affect the transport efficiency of foliar NPs to the phloem. However, our understanding of the roles of other properties, such as NP morphology, charge, and surface coating, in these processes is still limited. A previous study showed that negatively charged AuNPs with PVP and citrate coatings exhibited different behaviors in wheat plants (Avellan et al., 2019). Although almost all PVP-AuNPs crossed the leaf cuticle layers, their transport to the mesophyll was limited. Citrate-AuNPs with sizes similar to PVP-AuNPs showed good translocation to the plant vasculature, but their uptake by wheat leaves was incomplete (Avellan et al., 2019). This finding may reflect the different surface properties of PVP-AuNPs and citrate-AuNPs. More effort is required to better understand how foliar NPs enter the phloem.

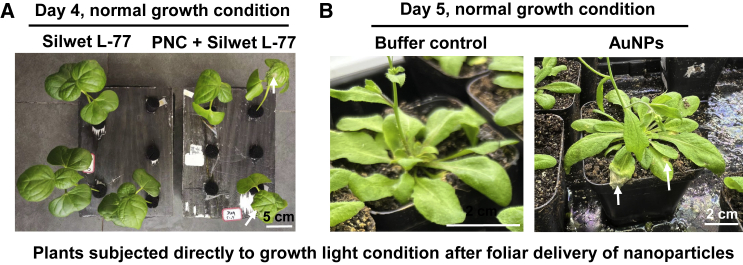

Light conditions may be another factor that affects the efficient delivery of foliar NPs to plants. Under growth lights (which usually range from 100–200 μmol m−2 s−1 for most crop plant species), active gas exchange at the stomata and transpiration could be factors that oppose the “downhill” nature of foliar sprayed NPs upon application. Thus, it may be important to keep plants under room light conditions (around 20–30 μmol m−2 s−1) but not dark conditions (which can cause stomatal closure) for a few hours to reduce the effect of active stomatal gas exchange and transpiration and allow more efficient transport of foliar sprayed NPs into plants. After foliar-sprayed plants were kept under room light conditions for 3 h, cerium oxide NPs did not cause damage to plants such as cotton (Liu et al., 2021), rapeseed (Li et al., 2022a, 2022b), and Arabidopsis (Wu et al., 2017b). Without adequate room light adaptation after foliar application of NPs, NPs caused phytotoxicity symptoms in plants such as cotton and Arabidopsis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phenotypes of plants subjected directly to a growth light after foliar application of NPs.

(A) Four days later, compared with a control plant (foliar spray with 0.05% Silwet L-77). Obvious phytotoxicity symptoms were observed in cotton plants subjected directly to growth light conditions after foliar application of 0.09 mM polyacrylic acid-coated nanoceria (PNC; ∼10 nm, approximately −18 mV).

(B) Five days later, compared with a control plant (leaf laminar infiltration with 10 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) + 10 mM MgCl2). Obvious phytotoxicity spots were observed in Arabidopsis plants subjected directly to growth light conditions after leaf laminar infiltration of 0.05 mg/l AuNPs (∼16 nm, ∼36 mV). White arrows indicate the damaged spots in NP-infiltrated plants without proper room light incubation.

During foliar spray application, the wetting behavior of an NP solution on the leaf is important for efficient delivery. Besides the factors mentioned above, including stomata, size of sieve plate pores, and light conditions, a frequently overlooked factor that limits the efficient delivery of foliar NPs is the surface tension of the solution. Plant leaves, especially waxy leaves, are known to repel foliar-sprayed water. Triton X-100, Silwet L-77, sodium dodecyl sulfate, and dodecyl trimethylammonium bromide are widely used agro-surfactants that help to deliver active ingredients (Zhang et al., 2017). Adding a surfactant to reduce surface tension is a common way to enable better absorption of NPs into leaves. The surface tension of water is 72.8 mN/m (Beattie et al., 2014). Without surfactant, multiple foliar applications of NP solution are commonly needed to produce a biological effect such as improving plant salt tolerance (Lu et al., 2020). The measured surface tensions for Triton X-100 and Silwet L-77 are 30 and 22 mN/m, respectively, much lower than the surface tension of water (Hu et al., 2020). Compared with Triton X-100, which enabled only 2-nm CDs (carbon dots) to enter maize leaves, the surfactant Silwet L-77 with a lower surface tension enabled the entry of 2-nm and 6-nm CDs (Hu et al., 2020). NPs with different sizes and charges (carboxyl or amine groups) do not significantly affect the surface tension of formulations with Triton X-100 or Silwet L-77, and Silwet L-77 does not cause aggregation of NPs such as PEI-CDs (polyethylenimine-coated CDs), succinic anhydride–modified PEI-CDs, and PNC (polyacrylic acid–coated nanoceria) (Hu et al., 2020). Compared with NPs designed for drug delivery, these NPs are fabricated somewhat more simply. For example, truncated chloroplast transit peptide–conjugated β-cyclodextrin-coated CDs have been developed for targeted delivery of methyl viologen and ascorbic acid to tune the redox state of chloroplasts (Santana et al., 2020). Their synthesis and characterization are much more complicated than those of PEI-CDs, succinic anhydride–modified PEI-CDs, and PNC (Hu et al., 2020). Whether surfactants affect properties such as the dispersibility and stability of nanoplatforms has been less studied. More studies are encouraged to investigate the role of surfactants in plant–NP interactions.

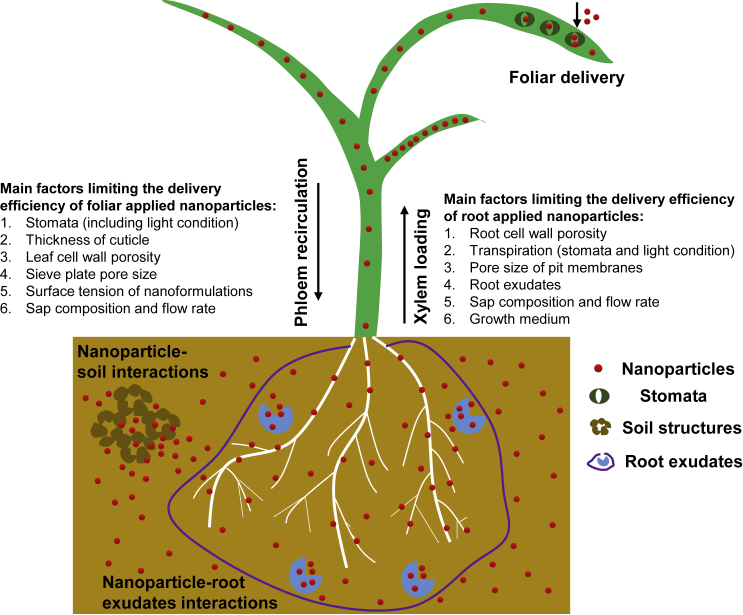

Figure 2 illustrates the main factors that limit leaf uptake efficiency of foliar NPs. Some NPs can be reduced in plants. For example, researchers have shown that during phloem recirculation of CuO NPs (20–40 nm, 100 g/l) in maize plants, Cu(II) is reduced to Cu(I) (Wang et al., 2012). Similar results have been shown in cucumber plants: about 15% of Ce(IV) was reduced to Ce(III) in roots treated with CeO2 NPs (25 nm, 200 mg/l) (Ma et al., 2017). A group from Carnegie Mellon University found Ce and Cu reduction in CeO2 NPs and Cu(OH)2 NPs during root uptake and leaf translocation (Spielman-Sun et al., 2018, 2019). Possible changes in valence states of metal oxide NPs during xylem loading and phloem recirculation in plants are worth considering in future studies. Another open question is what proportion of NPs in leaves have been recirculated from root-transported foliar NPs. Also, were the reduced nanoparticles reduced at their initial location or during long-distance transport; i.e., phloem transport to the root and xylem loading to the leaf? These could be good projects for future research.

Figure 2.

Main factors that limit delivery efficiency of nanoparticles to plants.

Interfacing NPs to plants in the field is done mainly through foliar delivery or root application. For foliar delivery, the status of stomata (open or closed), thickness of the cuticle, leaf cell wall porosity, sieve plate pore size in the phloem, surface tension of nanoformulations, sap composition, and sap flow rate are the main factors that affect the delivery efficiency of foliar NPs. For root application, interactions between NPs and soil or root exudates need to be considered. After NPs interface with roots, root cell wall porosity, transpiration, pore size of pit membranes, sap composition, and sap flow rate are the main factors that affect the delivery efficiency of root-applied NPs.

Efficient root uptake of NPs: The role of root exudates, root epidermis, Casparian strip, and transpiration rate

The first barrier to efficient root uptake of NPs could be root exudates. Root exudates can be grouped into low-molecular-weight compounds (mainly amino acids, organic acids, sugars, phenolics, and various other secondary metabolites) and high-molecular-weight compounds (mainly mucilage and proteins) (Walker et al., 2003). Approximately 30%–40% of photosynthetically fixed carbon is transferred to the rhizosphere as root exudates (Shang et al., 2019). Many studies have reported an effect of root exudates on root uptake efficiency of NPs. After 5 days in soybean root exudates, the size of nano-Cu(OH)2 (from 518 nm to 938 nm) and nano-MoO3 (from 372 nm to 690 nm) increased almost 2-fold (Cervantes-Avilés et al., 2021). Nano-CeO2 and nano-Mn3O4 were disaggregated in soybean root exudates from 289 nm to 129 nm and from 761 nm to 143 nm, respectively. Because of absorption of organic acids in root exudates onto particle surfaces, the four tested nanoparticles were negatively charged in root exudates. After 6 days in soybean root exudates, dissolution of MoO3, Cu(OH)2, Mn3O4, and CeO2 NPs was 38%, 1.2%, 0.5%, and less than 0.1% (Cervantes-Avilés et al., 2021), suggesting the stability of Mn3O4 and CeO2 NPs in root exudates. Similarly, maize root exudates modified the surface chemistry of CuO NPs, and higher-molecular-weight (>10 kDa) and lower-molecular-weight (<3 kDa) fractions of root exudates mostly reduced aggregation and promoted dissolution of CuO nanoparticles, respectively (Shang et al., 2019). Another study showed that citrate in wheat root exudates increased the dissolution of CuO NPs (McManus et al., 2018). Thus, elemental assessment of NPs may not fully represent the presence of NPs in plant tissue: the proportion of root exudate-enabled release of elements from NPs should be factored in. In root application of NPs, possible interactions between root exudates and NPs should be given more attention. The composition of root exudates differs among plant species, and we have an insufficient understanding of the effects of these different root exudate components on NPs.

The root epidermis could be the second barrier for efficient root uptake of NPs. When NPs interface with the root epidermis, the main routes for root uptake of NPs are the apoplastic and symplastic pathways (Schwab et al., 2016; Su et al., 2019). For the apoplastic pathway, cell wall porosity and the diameter and width of plasmodesmata are the main factors limiting the root uptake efficiency of NPs. For the symplastic pathway, the main limiting factors for efficient NP uptake include cell wall porosity, plasma membranes, organelle membranes, and the diameter and width of plasmodesmata. How NPs cross barriers at the single-cell level will be discussed below. Studies have shown that NPs can affect root apoplastic barriers. For example, CeO2 NPs shorten the root apoplastic barrier in rapeseed (Rossi et al., 2017). La2O3 NPs induce early development of apoplastic barriers (Yue et al., 2019). This suggests that a complex array of factors affect the root uptake efficiency of NPs. The main factors that limit the efficiency of NP movement across root cortical cells are likely to be very similar to those in the root epidermis, mainly associated with symplastic and apoplastic pathways.

After passing through the root epidermis and cortex, NPs face the endodermis. Here, in addition to the cell wall porosity of the endodermal cells, another barrier for efficient NP uptake is the Casparian strip, a localized impregnation of the primary cell wall that encircles the endodermal cell like a belt in the longitudinal direction (Geldner, 2013). This belt, which takes up approximately a quarter to a third of the transverse/anticlinal cell wall, is situated in the center of the transverse and anticlinal walls (Geldner, 2013). The compounds deposited in the Casparian strip are suberin, lignin, and some structural proteins, which are capable of reducing the diffusive apoplastic flow of water and solutes into the stele (Chen et al., 2011). Theoretically, NPs cannot easily pass through the Casparian strip, but some studies have shown distribution of NPs across the Casparian strip. One study showed that AuNPs (about 6 nm) traveled across the Casparian strips (Roppolo et al., 2011). A small portion of γ-Fe2O3 NPs was located close to the xylem, suggesting that γ-Fe2O3 with a size of 18 nm passed the Casparian strip (Li et al., 2016). Sub-micrometer plastics can enter the xylem through cracks where lateral roots penetrate the root endodermis and cortex (Li et al., 2020a). These findings suggest that a possible discontinuity in the Casparian strip or effects of NPs on the properties of the Casparian strip may allow their entry into the stele.

When NPs reach the xylem, transpiration rate may be another factor that affects the efficient uptake of NPs into roots. Previous studies have shown that dicots (tomato and lettuce) have a significantly higher translocation efficiency of CeO2 NPs than monocots (corn and rice), regardless of the positive, negative, or neutral charge of the CeO2 NPs (Spielman-Sun et al., 2019). This result may be associated with significantly higher transpiration rates in dicots than in monocots (Spielman-Sun et al., 2019). Similarly, compared with monocot plants (corn, lower transpiration rate), more CeO2 NPs were found in the root xylem of dicot plants (soybean, higher transpiration rate) (Zhang et al., 2019b). A study has shown that carbon-coated iron NPs can be detected not only in treated roots but also in untreated roots (pea, sunflower, and tomato) (Cifuentes et al., 2010), confirming the role of the transpiration stream in xylem loading of NPs. This result also suggests that the carbon-coated iron NPs had moved downward, probably through the phloem, using the source-sink pressure gradient (Cifuentes et al., 2010). These findings suggest that the transpiration rate is tightly associated with xylem loading of NPs. Transpiration rate is therefore an important factor that should be considered for the efficient delivery of NPs in plants.

Foliar application versus root delivery of NPs: The barriers are different

Leaf laminar infiltration (Wu et al., 2017b; Chincinska, 2021), foliar spraying (Hong et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2020), vacuum infiltration (Wu et al., 2017a; Izuegbunam et al., 2021), and root application (Zhang et al., 2019b; Spielman-Sun et al., 2019) are the most commonly used approaches for delivering NPs into plants. Foliar application and root delivery are the main approaches used in agricultural practice. In terms of adaptability for agricultural use, root application of NPs has less potential than foliar application. The main reasons are probably the easier access to aboveground plant parts than roots, the fact that hydroponics differ from real field conditions, and the possible NP aggregation caused by root exudates and soil. Plants are grown in soil under field conditions, and soil can affect the behavior of the applied nanomaterials. For example, TiO2 (79 and 164 nm, 5 mg/l) and Ag NPs (73 and 180 nm, 5 mg/l) were aggregated in soil solution extracted from farmland and floodplain soil (Zehlike et al., 2019). Soil factors such as natural organic matter, ionic strength, and pH can result in NP aggregation (Zhang et al., 2020). In the presence of soybean root exudates, nano-Cu(OH)2 (50 nm, 4 mV, 16.4 mg/l in distilled water) and nano-MoO3 (13–80 nm, −52 mV, 38.9 mg/l in distilled water) increased their mean aggregate size from 518 to 938 nm and from 372 to 690 nm, respectively, after 5 days (Cervantes-Avilés et al., 2021). A droplet system could be a way to deliver solutions/formulations containing NPs to plant roots in soil. However, this not only increases agricultural production costs but also may cause NP aggregation in pipelines over long-term use. Thus, in this review, we focus more on the factors that affect the delivery efficiency of foliar NPs.

The barriers faced by NPs differ depending on whether they are applied as a foliar spray or a root application. For example, unlike the uptake of large NPs (>20 nm) through stomata in leaves, we know little about how large NPs enter roots. Many studies have reported root uptake of large NPs (>20 nm) in plants (Al-Amri et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020a; Lv et al., 2021), but the underlying mechanisms have rarely been addressed. At the site of lateral root emergence, sub-micrometer plastics entered the xylem through cracks where lateral roots penetrated the root endodermis and cortex (Li et al., 2020a). A possible discontinuity in the Casparian strip may be the reason for this “crack entry” mode. The root meristem zone could be another potential site of NP entry. In this area, root meristem cells are mostly in an actively dividing state, and cell wall structure and integrity are therefore not as strong as in mature root cells, potentially allowing the transport of some large NPs. However, in the early developmental stage, cuticles are formed on root caps of primary and lateral roots to protect the sensitive meristems (Berhin et al., 2019), and this may affect the efficiency of root meristem delivery of large NPs. When NPs enter root cells, they can travel via symplastic and apoplastic pathways. For example, with diameters of 40 to 60 nm and widths of 700 to 800 nm (Patrick and Slewinski, 2013), plasmodesmata could be a pathway for the transport of NPs in roots. Another possibility for root uptake is that some NPs may be able to change the properties of the root epidermal cell walls to allow for more efficient NP entry. However, we still lack sufficient information on this topic, and more can be done in the future to address this knowledge gap. Figure 2 shows the main factors that limit the delivery efficiency of root-applied NPs.

So far, we have discussed the main barriers that can affect the delivery efficiency of NPs in plants. Whether the interface between NPs and plant barriers affects their fate is also worthy of attention. As mentioned above, the dissolution and aggregation of NPs can be affected by root exudates. Ce and Cu reduction in CeO2 and Cu(OH)2 NPs has been found during root uptake and leaf translocation in plants (Ma et al., 2017; Spielman-Sun et al., 2018, 2019). Previous studies have shown that plant xylem and root exudate composition is important for the transformation of nCeO2 in plants and thus for the subsequent translocation of Ce species (Zhang et al., 2019b). More efforts are required to better understand how NP fate in plants is affected by interfaces with plant barriers.

From the outside to the inside of a cell: How do NPs travel across the barriers of the cell wall and membranes?

The cell wall as a barrier: How do NPs travel across the cell wall?

Unlike animal cells, plant cells have a structure called the cell wall. This is the first barrier through which NPs must pass to enter a single plant cell. Plant cell wall porosity is known to be about 13 nm (Albersheim et al., 2011), with variations among different plant species and cell types (Chesson et al., 1997; Fujino and Itoh, 1998). For example, cell wall pores with radii of 1.5–3 nm are predominant in wheat cells (Chesson et al., 1997). The average pore size within the elongating cell wall of pea (Pisum sativum) epidermal cells is 5.5 ± 1.4 nm, whereas the average pore size in the non-elongating cell wall is 13.4 ± 4.3 nm (Fujino and Itoh, 1998). The commonly assumed size exclusion limit of cell walls is about 5–20 nm (Schwab et al., 2016). No cerium translocation from roots to shoots was found when the size of Zr/CeOx NPs was greater than 23 nm (Schwabe et al., 2015). Similarly, γ-Fe2O3 NPs with a size of 18 nm could not be translocated from roots to shoots (Li et al., 2016). Foliar-sprayed NPs (positively and negatively charged) with a size greater than 11 nm remained on the leaf surface of maize (Hu et al., 2020). Transmission electron microscopy images showed that cell walls of rapeseed (B. napus) root cells treated with ZnO NPs (45 nm) became more electron dense than those of the controls, suggesting possible binding of ZnO NPs to the cell wall (Molnár et al., 2020). This was not observed in Brassica juncea (Molnár et al., 2020), confirming a role for the cell wall in NP delivery efficiency. Other studies have shown that NPs with a size of around 50 nm can be transported into the cell (Judy et al., 2012; Slomberg and Schoenfisch, 2012), suggesting that cell wall pore size may not be the sole criterion that determines the efficiency with which nanomaterials cross the cell wall. The interaction between nanomaterials and the cell wall may be more complex than previously thought. For example, some nanomaterials may potentially trigger pore enlargement because the plant cell wall is a dynamic structure and has the flexibility to undergo rapid remodeling in response to changes in the surrounding environment (Houston et al., 2016). A previous study has shown that with shifting of Ag0 to Ag+ in AgNPs, which interact with ROS (reactive oxygen species), the released Ag+ can bind to hydroxyls in the cellulose structure, causing the breakdown of hydrogen bonds to facilitate changes in cell wall structure that allow passage of AgNPs (Kennedy et al., 2021). The cell wall also has an electrochemical gradient that may favor differently charged NPs. Cell wall electrical charges usually vary around −50 to −110 mV (Shomer et al., 2003), which is large enough to provide a driving force to facilitate or restrict NP uptake in plants. For example, a negatively charged cell wall may retain positively charged NPs. In Arabidopsis roots, negatively charged AuNPs (10 mg/l, −32 mV) were almost exclusively distributed inside the roots, whereas no positively charged AuNPs (10 mg/l, +46 mV) were observed inside the roots (Avellan et al., 2017). This indicates a possible role for the negatively charged cell wall in retaining positively charged NPs in roots. A similar result was found in an experiment that investigated the effect of NP surface zeta potential on interactions between NPs and the xylem/phloem. The results showed that positively charged NPs are attracted to xylem/phloem surfaces, implying that positively charged NPs, but not negatively charged NPs, are likely to be deposited on cell walls (Su et al., 2019). However, other studies have shown that positively charged NPs can be delivered more efficiently into plants than negatively charged NPs (Cunningham et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2020), in contrast to the studies mentioned above. Our understanding of the role of cell wall electrical potential in plant NP uptake is limited. More efforts are needed to address these contrasting results. Factors such as application mode, organs that interface with NPs, NP properties, NP dosage, plant species, and plant growth stage could be candidates.

The plant cell wall is composed of cross-linked units, including pectin and proteins (Shomer et al., 2003). The primary composition of the cell wall is cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin (Zeng et al., 2017). NPs are known to affect plant cell wall components to remodel the plant cell wall. Exposure of tobacco suspension-cultured cells to nY2O3 NPs resulted in a 7- to 13-fold thickening of cell walls compared with unexposed controls, together with an up to 58% increase in pectin and a 29% reduction in hemicellulose (Chen et al., 2021). Because the cell wall is a barrier to NP uptake, NP-induced changes in the cell wall and its components may affect NP delivery efficiency into plants. ZnO NPs caused accumulation of the cell wall component callose when applied at 100 mg/l but not at 25 mg/l (Molnár et al., 2020), suggesting a role for dosage in NP interactions with cell wall components. Callose is known to play a role in plant response to stress or damage (De Storme and Geelen, 2014). More studies are needed to investigate the possible interactions between NPs and the cell wall and their possible role in the efficiency with which NPs cross the cell wall. Whether the interaction between NPs and the plant cell wall is associated with different cell types is still largely unknown. These are important issues worthy of further study to better understand the factors that affect the efficiency of NP movement across the cell wall.

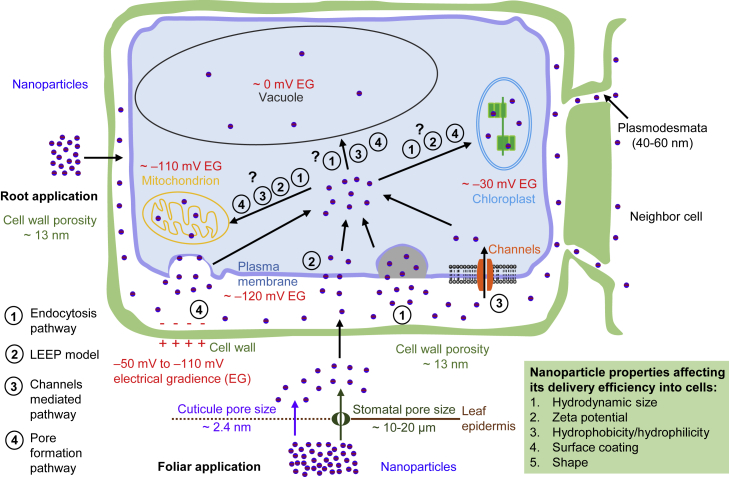

In addition to changes in cell wall thickness and cell wall components and the use of monoclonal antibodies against pectic and arabinogalactan protein epitopes, researchers found that NPs can induce changes in the cell wall composition of barley roots (Milewska-hendel et al., 2021). Methylesterified homogalacturonan (a major pectin that occurs in the primary cell wall) was observed in rhizodermal walls of the differentiation zone in AuNP-treated barley roots but was not detected in control roots (Milewska-hendel et al., 2021). This suggests that cell wall components can be modified by NPs, potentially affecting the efficiency with which they cross the cell wall. The transport of NPs across the cell wall might be facilitated or impaired by enlarging cell wall pores or aggregating/blocking NPs. Our knowledge about this possibility is insufficient. Whether the properties of NPs are affected by cell wall components is also largely unknown. Polysaccharides in cell walls might cause aggregation of NPs. For example, hemicellulose is known to cause aggregation of AgNPs (Fu et al., 2018). Also poorly understood is whether NPs affect the expression of genes involved in the synthesis of cell wall components. More research is needed on the interaction between NPs and plant cell walls. Figure 3 shows how NPs might travel across plant cell wall barriers.

Figure 3.

A proposed model showing cell barriers faced by NPs and possible mechanisms by which NPs pass through these barriers.

The cell wall, plasma membrane, and organelle membrane are the main barriers that limit the delivery efficiency of NPs into a cell. In foliar application, NPs can pass through the leaf barrier via the stomatal or cuticular pathway. The latter applies only to small NPs (less than ∼2.4 nm). Unlike the stomatal and cuticular pathways in foliar application, root-applied NPs directly interface with root cells. Cells located at the root meristem zone, which is in an actively dividing state, may be able to deliver large NPs. Three mechanisms are proposed by which NPs may cross the plasma membrane. As in animal cells, NPs might enter plant cells by endocytosis. Channels like mechanosensitive channels, which can deliver cargo about 4 nm in size, could be a possible means of plant cell NP uptake. A well-established model, lipid exchange envelope penetration, applies more to high-aspect-ratio nanomaterials. Some NPs may form a pore on the membrane to allow entry of NPs. The electrical gradient across cell membranes could be an important factor that affects NP delivery. It is mostly unknown how NPs cross organelle membranes. More efforts are needed on this topic.

Cell wall porosity and NP size may not be the only factors that limit the delivery efficiency of NPs across the cell wall. Other factors, such as the electrical gradient across the cell wall, dosage of NPs, and interactions between NPs and cell wall components may also contribute to the efficient delivery of NPs across the plant cell wall.

The membrane as a barrier: How do NPs travel across the plasma membrane and organelle membranes?

At the cell level, after the cell wall, the plasma membrane is the second barrier nanomaterials must overcome to enter the cell. How nanomaterials interact with the plant plasma membrane is still unknown. The plasma membrane is a single-layered membrane and a lipid bilayer embedded with proteins. In animal cells, which lack a cell wall, endocytosis is a common mechanism for the internalization of nanomaterials (Manzanares and Ceña, 2020). In plant cells, nanomaterials generally need to pass first through the cell wall barrier, which has a pore size of around 13 nm (Albersheim et al., 2011). This means that nanomaterials with at least one dimension close to 13 nm have a better chance of interfacing with the plasma membrane. Therefore, endocytosis may not be the most common pathway for plant nanomaterial uptake. Although endocytosis is a known mechanism for the internalization of nanomaterials in plants (Schwab et al., 2016; Lv et al., 2021), researchers have found that the uptake of foliar-injected cerium oxide NPs in Arabidopsis does not rely on endocytosis (Wu et al., 2017b). Researchers also found that, compared with rod-shaped AuNPs with cellular internalization, spherical small interfering RNA (siRNA)-functionalized AuNPs (10 nm) without cellular internalization showed the most efficient siRNA delivery and thus induced gene silencing in tobacco leaves (Zhang et al., 2022). Nanomaterials with a small size, less than ∼3 nm, may use transporters or channels located on the membrane to gain entry to the cell. For example, silver NPs can activate the mechanosensitive channel, which has channel pores of around 3 nm (Perozo et al., 2002; Sosan et al., 2016). Another known mechanism of nanomaterial transport into cells is lipid exchange envelope penetration (Wong et al., 2016), which is more common for high-aspect-ratio nanomaterials. Research has shown that quantum dots can form nanopores in suspended lipid bilayers (Klein et al., 2008). Instead of simply diffusing freely within the plane of the plasma membrane, membrane proteins tend to be localized in nanodomains, which usually have a size of 20–1000 nm (Mckenna et al., 2019). The plant cell wall regulates the dynamics and size of nanodomains (Mckenna et al., 2019), further indicating that the plant cell wall may play a role in NP movement across the plasma membrane.

Another factor worthy of investigation is the electrochemical gradient across the membrane (called the membrane potential) (Wu et al., 2013). The presence of an electrochemical gradient could favor and provide the driving force for the translocation of charged nanomaterials. The membrane potential across the plasma membrane in plant cells is around −120 mV (Wu et al., 2013), which is large enough to facilitate NP transport. The role of membrane potential in NP delivery efficiency and the effect of differently charged NPs on membrane potential formation in plants are rarely addressed. Previous studies have shown that neutral NPs are not transported into protoplasts, whereas small nanomaterials (<10 nm) with a high absolute zeta potential (>40 mV) can be efficiently transported into the cytosol and chloroplasts of plant protoplasts (Thomas et al., 2018). In animal cells, amine-modified polystyrene NPs lead to significant depolarization of the plasma membrane, whereas carboxylate-modified polystyrene NPs do not cause such depolarization (Warren and Payne, 2015). This suggests that positively charged polystyrene NPs are transported more efficiently into the cytosol of animal cells, causing membrane depolarization. This is not the case in plant cells. Our previous studies showed that negatively charged nanoceria (−18 mV, 10 nm) have significantly higher delivery efficiency into plant cells than positively charged nanoceria (Wu et al., 2017b), and they do not cause membrane depolarization in Arabidopsis leaf mesophyll cells (Wu et al., 2018). The process is more complicated in plant cells than in animal cells. Many factors may be involved. For example, the cell wall may retain some positively charged NPs (Avellan et al., 2019; Su et al., 2019) because it is negatively charged. This is also true in bacteria. Via electrostatic attraction, positively charged Fe3O4 NPs successfully capture bacteria, which have a negatively charged cell wall. Negatively charged NPs do not show affinity toward Escherichia coli (Li et al., 2019a).

Besides being localized in the cytosol, previous studies have shown that nanomaterials can be transported into organelles; e.g., chloroplasts, mitochondria, and even vacuoles (Milewska-Hendel et al., 2019). Cerium oxide NPs have been reported to be transported into chloroplasts in rice (Zhou et al., 2021), cotton (Liu et al., 2021), rapeseed (Li et al., 2022), and Arabidopsis (Wu et al., 2017b). nY2O3 NPs can be transported into the vacuoles of tobacco suspension cells (Chen et al., 2021). At the organelle level, organelle membranes are another barrier for the transport of NPs. The main organelles in plant cells are the nucleus, chloroplast/plastid, mitochondrion, Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum, vacuole, and peroxisome. The nucleus, chloroplast, mitochondrion, Golgi apparatus, and endoplasmic reticulum have double-layered membranes, whereas the vacuole and peroxisome are surrounded by single-layered membranes. How NPs pass through organelle membranes to enter organelles is rarely studied. The mechanisms that underlie nanomaterial travel across membranes could vary among different organelles. As with the plasma membrane, the electrochemical gradient across the organelle membrane could be a driving force that facilitates NP transport into organelles. For chloroplasts in the light, the trans-envelope voltage difference is about 110 mV at 5 mM KCl and negative on the stromal side, showing a −110 mV electrochemical gradient (Pottosin and Dobrovinskaya, 2015). For mitochondria, the intermembrane space is more negative than the cytosol by about 30 mV (Pottosin and Shabala, 2015), showing a −30 mV electrochemical gradient. Although it has been argued that the electrochemical gradient across the tonoplast membrane is around zero in many plant species (Pottosin et al., 1999), the electrochemical gradient across tonoplasts can vary from −31 mV to 50 mV (Wu and Li, 2019). However, few studies have investigated the role of the electrochemical gradient across organelle membranes in NP transport into organelles. Our understanding of the possible effect of NPs on organelles is limited. In addition to damage to the structural organization of the photosynthetic apparatus, smaller and fewer chloroplasts per cell have been observed in barley plants treated with ZnO NPs (hydrodynamic diameter, 360 nm; −21 mV, 300 mg/l) than in controls (Rajput et al., 2021). In another study, ZnO NPs (46 nm, 400 mg/l) induced oxidative stress and dysfunction of the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria, leading to programmed cell death in tobacco BY2 cells (Balážová et al., 2020). Investigating how NPs enter organelles and their effect on organelles could be an important topic for future studies. Figure 3 shows the proposed mechanisms by which NPs travel across barriers at the level of the single plant cell. More effort is needed to obtain insights into the interaction between nanomaterials and plant cell organelles. The effects of NPs on membrane lipids are also worthy of study. Remodeling of membrane lipids is known to be an important strategy for plant response to stress (Yu et al., 2021). Designing nanomaterials to deliver lipids to fine-tune the composition of membrane lipids might be a way to improve plant stress tolerance.

Friend or foe? The importance of designing, evaluating, and using NPs for agriculture

The importance of controlling the properties of nanomaterials for agriculture

After determining the process of NP uptake and translocation, the next step for using nanomaterials in plants is to avoid causing phytotoxicity. Although the use of nanomaterials has good potential in agriculture (Adisa et al., 2019), their phytotoxicity (Khan et al., 2019) and effect on the environment must be considered. Phytotoxicity of nanomaterials is widely reported (Lee et al., 2010; Nhan et al., 2015; Ruttkay-Nedecky et al., 2017), although contrasting results are also reported. For example, although AgNPs show antifungal activity against Bipolaris sorokiniana (Mishra et al., 2014), wood-rotting pathogens (e.g., Gloeophyllum abietinum; Narayanan and Park, 2014), and phytophthora pathogens (e.g.,Phytophthora parasitica; Ali et al., 2015), etc., foliar application of AgNPs induces oxidative stress in cucumber leaves (Zhang et al., 2018a). Cerium oxide NPs with a negative charge, about 10-nm size, and low Ce3+/Ce4+ ratio improved plant tolerance to high light, heat, cold, and salinity in different plant species, including cotton, rice, rapeseed, cucumber, and Arabidopsis (Wu et al., 2017b, 2018; An et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2021, 2022; Liu et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022b; Chen et al., 2022). By contrast, cerium oxide NPs with a 99-nm size and 47-mV charge resulted in toxicity to asparagus lettuce plants, causing reduced root length (Cui et al., 2014). These contrasting results may be associated with many factors, such as size, morphology, surface conjugation, the ratio of metal element valence states, dosage, and application modes of the nanomaterials. For example, different application methods, such as leaf laminar infiltration and vacuum infiltration, produced varied delivery efficiency of quantum dots into Arabidopsis leaves (Wu et al., 2017a). This calls for rethinking of appropriate design, evaluation, and use of nanomaterials in agricultural production. As mentioned in previous studies, the majority of work suggests that the low-to-moderate overall phytotoxicity of nanomaterials to terrestrial plants is due to factors such as high dose, short exposure, inappropriate exposure medium, etc. (Servin and White, 2016).

Designing nanomaterials with appropriate properties is probably the key to minimizing potential negative effects of nanomaterials on plants. Avoiding heavy metal elements, controlling size, shape, and optical properties, ensuring good stability and solubility, determining correct dosages, and maintaining low costs should be key points when designing nanomaterials for sustainable agricultural applications. The importance of controlling nanomaterial properties for agricultural use is shown in Figure 4, with an emphasis on the proposed factors. More attention has been paid to this field. For example, it has been shown that the delivery efficiency of positively charged NPs is better than that of negatively charged NPs for foliar application (Hu et al., 2020). However, leaf laminar infiltration experiments have shown that negatively charged NPs can enter mesophyll cells more efficiently than positively charged ones (Wu et al., 2017b). Other work has shown that negatively charged cerium oxide NPs can be translocated more efficiently from roots to shoots (Li et al., 2019b). In tomato, positively charged CeO2 NPs mostly adhere to the roots untransformed, whereas negatively charged CeO2 NPs are translocated more efficiently from roots to shoots (Spielman-Sun et al., 2019). Similar results have been reported with small AuNPs (6–10 nm), showing that positively charged AuNPs are most readily taken up by plant roots, whereas negatively charged AuNPs are most efficiently translocated from roots to shoots (Zhu et al., 2012). Another study did not observe positively charged AuNPs inside the root but found that they were mainly trapped as large agglomerates in the outermost root mucilage layer. Most of the negatively charged AuNPs were found inside Arabidopsis roots (Avellan et al., 2017). With root application, the total mass of positively charged NPs that reach the root surface may be reduced because of the negative charge on most soil particles, and this may limit the availability of positively charged NPs to plants (Su et al., 2019). A group from the University of California, Berkeley has shown that size, shape, compactness, and stiffness of nanostructures affect the efficiency of cellular internalization and, thus, the subsequent gene silencing in tobacco plants (Zhao et al., 2019). They showed that when DNA-functionalized AuNPs were used to deliver siRNA, cellular internalization efficiency was not associated with the final induced gene silencing in tobacco leaves (Zhang et al., 2022). This result suggests that factors that affect biological functions and final outcomes in plants could vary among different NPs. These studies suggest that many factors, such as medium, application mode (foliar or root), plant species, root exudates, and NP properties, may affect the final delivery efficiency of NPs in plants, indicating the complexity of plant NP uptake and translocation. More studies are needed to determine the key parameters that govern NP uptake, fate, and biological effects.

Figure 4.

The importance of properly designing nanomaterials for crop production enhancement.

Different areas of the cycles represent the proposed priority of factors that should be considered during the design and synthesis of nanomaterials for crops.

Exploring environmentally friendly nanomaterials matters for nano-enabled agriculture: Learning from nature

Biosafety issues are always the main concerns from the public regarding the use of nanomaterials in agriculture. The biosafety of nanomaterials, especially those that contain heavy metals, is always questioned. Nanomaterials conjugated with polymers or chemicals with low biocompatibility or even toxicity are also raising biosafety concerns. Many studies have reported toxic effects of nanomaterials on biological systems (Ruttkay-Nedecky et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018b). Exploring nanomaterials without heavy metals or conjugated with biocompatible polymers or chemicals could possibly remove some concerns. As mentioned above, nanomaterials are not new to nature. Learning from nature and aiming to design environmentally friendly nanomaterials matter for the development and sustainability of nano-enabled agriculture. Future work in agricultural nanobiotechnology should consider the use or design of nanomaterials while addressing public concerns. Besides the effects on plants and the possibility of long-term environmental accumulation, we should pay attention to the effects of NPs on other living organisms in the soil and environment, such as insects, the soil microbiome, bees, etc., to make sure NPs are safe for use in agricultural fields.

Stress limits efficient crop production in agriculture. Overaccumulation of ROS and the resulting oxidative damage are common in plants under stress. Plants have evolved enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems to maintain a balance between ROS production and scavenging. Use of nanomaterials to augment plant ROS homeostasis maintenance is a feasible way to support nano-enabled agriculture. Efficient delivery of environmentally friendly NPs with ROS scavenging ability into plants might be a good approach to help to improve plant stress tolerance. For example, CDs have the advantages of small size, self-fluorescence, facile surface conjugation, and absence of heavy metal elements (Li et al., 2020b; Zhu et al., 2022). Their small size and facile surface conjugation could allow for efficient delivery into plants. Without proper control of these properties, carbon nanomaterials could also have negative effects on plants. For example, in a broad range of applied concentrations (100–1000 mg/l), carbon nanotubes (multilayer, with an outer diameter of 30–50 nm, a length of 10–20 μm, and ∼95% purity) and graphene (multilayer, with a diameter of 2 μm, a thickness of 8–12 nm, and ∼97% purity) resulted in reduced biomass of tomato seedlings (López-Vargas et al., 2020). CDs doped with elements that have multiple valence states may show ROS scavenging ability. For example, selenium-doped CDs have good ROS scavenging ability (Li et al., 2017). Agricultural products enriched with rare elements are increasingly favored in the market; e.g., selenium-rich agricultural products (Bañuelos et al., 2012). Thus, CDs such as selenium-doped CDs with ROS scavenging ability have good potential to be adopted for agricultural use. Another approach is to follow plant nutritional needs. Metal elements such as potassium, calcium, zinc, iron, magnesium, manganese, copper, and molybdenum are essential nutrients for plant growth. Designing nanomaterials based on these metal elements could be a way to largely remove public concern. Having ROS-scavenging ability, Mn3O4 NPs help to improve cucumber salinity stress tolerance (Lu et al., 2020). Application of NPs based on Fe, Zn, Mg, and Cu also showed improved plant stress tolerance (Faizan et al., 2018, 2021; Ma et al., 2020; Bidi et al., 2021). These approaches are worthy of consideration for nano-enabled agriculture. Environmentally friendly nanomaterials with ROS-scavenging ability, such as selenium-doped CDs and Mn3O4 NPs, could be good candidates for nano-improved plant stress tolerance. Controlling the properties of these NPs to allow for efficient delivery into plants is another key factor that should be considered in future studies.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

In this review, we analyzed and discussed important factors that affect the delivery efficiency of root and foliar NPs. Factors and proposed mechanisms regarding how nanomaterials travel across plant barriers, including the plant cell wall and membrane barriers, were reviewed and discussed. Knowledge gaps were identified. Learning from nature and designing nanomaterials based on needs could facilitate the development of nano-enabled agriculture.

Besides directly interfacing with plants, nanomaterials are also used as platforms to deliver cargo to plants. For example, Fe3O4 NPs (Zhao et al., 2017b; Wang et al., 2022a) and single-walled carbon nanotubes (Demirer et al., 2019; Kwak et al., 2019) have been used to deliver DNA to enable transgenic events in non-model plant species such as wheat and cotton. Clay nanosheets (Mitter et al., 2017), DNA nanostructures (Zhang et al., 2019a), gold nanoclusters (Zhang et al., 2021), and AuNPs (Zhang et al., 2022) have been used to deliver siRNA to enable RNA silencing in plants. Synthesized peptides have also been used to deliver proteins into Arabidopsis plant cells (Ng et al., 2016). The relationship between the internalization efficiency of nanomaterial cargo and the physical properties of the nanomaterials (e.g., size, charge, and stiffness) are discussed in these works. Factors that limit the efficiency of travel across barriers in plants may differ between nanomaterials and nanomaterial-cargo complexes. Future studies are encouraged to address this question.

Funding

This work was supported by the NSFC (32071971 and 31901464), project 2662020ZKPY001 supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and joint project SZYJY2021008 from Huazhong Agricultural University and the Agricultural Genomics Institute at Shenzhen, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (to H.W.).

Author contributions

H.W. and Z.L. conceived the manuscript. Both authors contributed to writing the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lin Yue, Jie Qi, and PhD candidate Jiahao Liu for help with preparing Figure 1. No conflict of interest is declared.

Published: June 9, 2022

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and CEMPS, CAS.

Contributor Information

Honghong Wu, Email: honghong.wu@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Zhaohu Li, Email: lizhaohu@cau.edu.cn.

References

- Adisa I.O., Pullagurala V.L.R., Peralta-Videa J.R., Dimkpa C.O., Elmer W.H., Gardea-Torresdey J.L., White J.C. Recent advances in nano-enabled fertilizers and pesticides: a critical review of mechanisms of action. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2019;6:2002–2030. doi: 10.1039/c9en00265k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Amri N., Tombuloglu H., Slimani Y., Akhtar S., Barghouthi M., Almessiere M., Alshammari T., Baykal A., Sabit H., Ercan I., et al. Size effect of iron (III) oxide nanomaterials on the growth, and their uptake and translocation in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020;194:110377. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alavi M., Rai M. Recent progress in nanoformulations of silver nanoparticles with cellulose, chitosan, and alginic acid biopolymers for antibacterial applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019;103:8669–8676. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-10126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albersheim P., Darvill A., Roberts K., Sederoff R., Staehelin A. Plant Cell Walls; 2011. Cell Walls and Plant Anatomy. Advance Access published 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ali M., Kim B., Belfield K.D., Norman D., Brennan M., Ali G.S. Inhibition of Phytophthora parasitica and P. capsici by silver nanoparticles synthesized using aqueous extract of Artemisia absinthium. Phytopathology. 2015;105:1183–1190. doi: 10.1094/phyto-01-15-0006-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- M Almutairi Z. Influence of silver nano-particles on the salt resistance of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) during germination. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2016;18:449–457. doi: 10.17957/ijab/15.0114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- An J., Hu P., Li F., Wu H., Shen Y., White J.C., Tian X., Li Z., Giraldo J.P. Emerging investigator series: molecular mechanisms of plant salinity stress tolerance improvement by seed priming with cerium oxide nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2020;7:2214–2228. doi: 10.1039/d0en00387e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Avellan A., Schwab F., Masion A., Chaurand P., Borschneck D., Vidal V., Rose J., Santaella C., Levard C. Nanoparticle uptake in plants: gold nanomaterial localized in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana by X-ray computed nanotomography and hyperspectral imaging. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:8682–8691. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b01133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avellan A., Yun J., Zhang Y., Spielman-Sun E., Unrine J.M., Thieme J., Li J., Lombi E., Bland G., Lowry G.V. Nanoparticle size and coating chemistry control foliar uptake pathways, translocation, and leaf-to-rhizosphere transport in wheat. ACS Nano. 2019;13:5291–5305. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b09781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avellan A., Yun J., Morais B.P., Clement E.T., Rodrigues S.M., Lowry G.V. Critical review: role of inorganic nanoparticle properties on their foliar uptake and in planta translocation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021;55:13417–13431. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c00178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balážová Ľ., Baláž M., Babula P. Zinc oxide nanoparticles damage tobacco BY-2 cells by oxidative stress followed by processes of autophagy and programmed cell death. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:1066. doi: 10.3390/nano10061066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bañuelos G.S., Stushnoff C., Walse S.S., Zuber T., Yang S.I., Pickering I.J., Freeman J.L. Biofortified, selenium enriched, fruit and cladode from three Opuntia Cactus pear cultivars grown on agricultural drainage sediment for use in nutraceutical foods. Food Chem. 2012;135:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie J.K., Djerdjev A.M., Gray-weale A., Kallay N., Lützenkirchen J., Preočanin T., Selmani A. pH and the surface tension of water. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;422:54–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhin A., de Bellis D., Franke R.B., Buono R.A., Nowack M.K., Nawrath C., Berhin A., Bellis D.D., Franke R.B., Buono R.A., et al. The root cap cuticle: a cell wall structure for seedling establishment and lateral root formation. Cell. 2019;176:1367–1378.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidi H., Fallah H., Niknejad Y., Barari Tari D. Iron oxide nanoparticles alleviate arsenic phytotoxicity in rice by improving iron uptake, oxidative stress tolerance and diminishing arsenic accumulation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021;163:348–357. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt J., Basi S., Pariyar S., Hunsche M. Stomatal penetration by aqueous solutions - an update involving leaf surface particles. New Phytol. 2012;196:774–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussières P. Estimating the number and size of phloem sieve plate pores using longitudinal views and geometric reconstruction. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4929. doi: 10.1038/srep04929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes-Avilés P., Huang X., Keller A.A. Dissolution and aggregation of metal oxide nanoparticles in root exudates and soil leachate: implications for nanoagrochemical application. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021;55:13443–13451. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c00767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Cai X., Wu X., Karahara I., Schreiber L., Lin J. Casparian strip development and its potential function in salt tolerance. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011;6:1499–1502. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.10.17054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Wang C., Yue L., Zhu L., Tang J., Yu X., Cao X., Schröder P., Wang Z. Cell walls are remodeled to alleviate nY2O3 cytotoxicity by elaborate regulation of de novo synthesis and vesicular transport. ACS Nano. 2021;15:13166–13177. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c02715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Peng Y., Zhu L., Huang Y., Bie Z., Wu H. CeO2 nanoparticles improved cucumber salt tolerance is associated with its induced early stimulation on antioxidant system. Chemosphere. 2022;299:134474. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesson A., Gardner P.T., Wood T.J. Cell wall porosity and available surface area of wheat straw and wheat grain fractions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1997;75:289–295. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0010(199711)75:3<289::aid-jsfa879>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chincinska I.A. Leaf infiltration in plant science: old method, new possibilities. Plant Methods. 2021;17:83. doi: 10.1186/s13007-021-00782-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes Z., Custardoy L., de la Fuente J.M., Marquina C., Ibarra M.R., Rubiales D., Pérez-de-Luque A. Absorption and translocation to the aerial part of magnetic carbon-coated nanoparticles through the root of different crop plants. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2010;8:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui D., Zhang P., Ma Y., He X., Li Y., Zhang J., Zhao Y., Zhang Z. Effect of cerium oxide nanoparticles on asparagus lettuce cultured in an agar medium. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2014;1:459–465. doi: 10.1039/c4en00025k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham F.J., Goh N.S., Demirer G.S., Matos J.L., Landry M.P. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery towards advancing plant genetic engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2018;36:882–897. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danila F.R., Quick W.P., White R.G., Furbank R.T., von Caemmerer S. The metabolite pathway between bundle sheath and mesophyll: quantification of plasmodesmata in leaves of C3 and C4 monocots. Plant Cell. 2016;28:1461–1471. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Storme N., Geelen D. Callose homeostasis at plasmodesmata: molecular regulators and developmental relevance. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:138. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirer G.S., Zhang H., Matos J.L., Goh N.S., Cunningham F.J., Sung Y., Chang R., Aditham A.J., Chio L., Cho M.J., et al. High aspect ratio nanomaterials enable delivery of functional genetic material without DNA integration in mature plants. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019;14:456–464. doi: 10.1038/s41565-019-0382-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirer G.S., Zhang H., Goh N.S., Pinals R.L., Chang R., Landry M.P. Carbon nanocarriers deliver siRNA to intact plant cells for efficient gene knockdown. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eaaz0495. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz0495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichert T., Goldbach H.E. Equivalent pore radii of hydrophilic foliar uptake routes in stomatous and astomatous leaf surfaces – further evidence for a stomatal pathway. Physiol. Plantarum. 2008;132:491–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2007.01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugenio M., Müller N., Frasés S., Almeida-Paes R., Lima L.M.T.R., Lemgruber L., Farina M., De Souza W., Sant’Anna C. Yeast-derived biosynthesis of silver/silver chloride nanoparticles and their antiproliferative activity against bacteria. RSC Adv. 2016;6:9893–9904. doi: 10.1039/c5ra22727e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faizan M., Faraz A., Yusuf M., Khan S.T., Hayat S. Zinc oxide nanoparticle-mediated changes in photosynthetic efficiency and antioxidant system of tomato plants. Photosynthetica. 2018;56:678–686. doi: 10.1007/s11099-017-0717-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faizan M., Bhat J.A., Chen C., Alyemeni M.N., Wijaya L., Ahmad P., Yu F. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) induce salt tolerance by improving the antioxidant system and photosynthetic machinery in tomato. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021;161:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L.H., Gao Q.L., Qi C., Ma M.G., Li J.F. Microwave-hydrothermal rapid synthesis of cellulose/Ag nanocomposites and their antibacterial activity. Nanomaterials. 2018;8:978. doi: 10.3390/nano8120978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino T., Itoh T. Changes in pectin structure during epidermal cell elongation in pea (Pisum sativum) and its implications for cell wall architecture. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998;39:1315–1323. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Avellan A., Laughton S., Vaidya R., Rodrigues S.M., Casman E.A., Lowry G.V. CuO nanoparticle dissolution and toxicity to wheat (Triticum aestivum) in rhizosphere soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52:2888–2897. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b05816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardea-Torresdey J.L., Gomez E., Peralta-Videa J.R., Parsons J.G., Troiani H., Jose-Yacaman M. Alfalfa sprouts: a natural source for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2003;19:1357–1361. doi: 10.1021/la020835i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geldner N. The endodermis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013;64:531–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo J.P., Wu H., Newkirk G.M., Kruss S. Nanobiotechnology approaches for engineering smart plant sensors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019;14:541–553. doi: 10.1038/s41565-019-0470-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillo R., Mattos B.D., Antunes D.R., Forini M.M.L., Monikh F.A., Rojas O.J. Foliage adhesion and interactions with particulate delivery systems for plant nanobionics and intelligent agriculture. Nano Today. 2021;37:101078. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2021.101078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grulke E.A., Beck M.J., Yokel R.A., Unrine J.M., Graham U.M., Hancock M.L. Surface-controlled dissolution rates: a case study of nanoceria in carboxylic acid solutions. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2019;6:1478–1492. doi: 10.1039/c9en00222g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J., Peralta-Videa J.R., Rico C., Sahi S., Viveros M.N., Bartonjo J., Zhao L., Gardea-Torresdey J.L. Evidence of translocation and physiological impacts of foliar applied CeO2 nanoparticles on cucumber (Cucumis sativus) plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:4376–4385. doi: 10.1021/es404931g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J., Wang C., Wagner D.C., Gardea-torresdey J.L., He F., Rico C.M. Foliar application of nanoparticles: mechanisms of absorption, transfer, and multiple impacts. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2021;8:1196–1210. doi: 10.1039/d0en01129k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houston K., Tucker M.R., Chowdhury J., Shirley N., Little A. The plant cell wall: a complex and dynamic structure as revealed by the responses of genes under stress conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:984. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P., An J., Faulkner M.M., Wu H., Li Z., Tian X., Giraldo J.P. Nanoparticle charge and size control foliar delivery efficiency to plant cells and organelles. ACS Nano. 2020;14:7970–7986. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b09178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izuegbunam C.L., Wijewantha N., Wone B., Ariyarathne M.A., Sereda G., Wone B.W.M. A nano-biomimetic transformation system enables in planta expression of a reporter gene in mature plants and seeds. Nanoscale Adv. 2021;3:3240–3250. doi: 10.1039/d1na00107h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judy J.D., Unrine J.M., Rao W., Wirick S., Bertsch P.M. Bioavailability of gold nanomaterials to plants: importance of particle size and surface coating. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:8467–8474. doi: 10.1021/es3019397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kah M., Hofmann T. Nanopesticide research: current trends and future priorities. Environ. Int. 2014;63:224–235. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kah M., Tufenkji N., White J.C. Nano-enabled strategies to enhance crop nutrition and protection. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019;14:532–540. doi: 10.1038/s41565-019-0439-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karami A., Sepehri A. Nano titanium dioxide and nitric oxide alleviate salt induced changes in seedling growth, physiological and photosynthesis attributes of barley. Zemdirbyste. 2018;105:123–132. doi: 10.13080/z-a.2018.105.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kardiman R., Ræbild A. Relationship between stomatal density, size and speed of opening in Sumatran rainforest species. Tree Physiol. 2018;38:696–705. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpx149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paiva Pinheiro S.K., Rangel Miguel T.B.A., Chaves M.d.M., Barros F.C.d.F., Farias C.P., de Moura T.A., Ferreira O.P., Paschoal A.R., Souza Filho A.G., de Castro Miguel E., et al. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) internalization and passage through the Lactuca sativa (Asteraceae) outer cell wall. Funct. Plant Biol. 2021;48:1113. doi: 10.1071/fp21161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M.R., Adam V., Rizvi T.F., Zhang B., Ahamad F., Jośko I., Zhu Y., Yang M., Mao C. Nanoparticle–plant interactions: two-way traffic. Small. 2019;15:1901794. doi: 10.1002/smll.201901794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M.N., Li Y., Khan Z., Chen L., Liu J., Hu J., Wu H., Li Z. Nanoceria seed priming enhanced salt tolerance in rapeseed through modulating ROS homeostasis and α-amylase activities. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19:276. doi: 10.1186/s12951-021-01026-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M.N., Li Y., Fu C., Hu J., Chen L., Yan J., Khan Z., Wu H., Li Z. CeO2 nanoparticles seed priming increases salicylic acid level and ROS scavenging ability to improve rapeseed salt tolerance. Glob. Challenges. 2022:2200025. doi: 10.1002/gch2.202200025. (Accepted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S.A., Wilk S.J., Thornton T.J., Posner J.D. Formation of nanopores in suspended lipid bilayers using quantum dots. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2008;109:012022. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/109/1/012022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kranjc E., Mazej D., Regvar M., Drobne D., Remškar M. Foliar surface free energy affects platinum nanoparticle adhesion, uptake, and translocation from leaves to roots in arugula and escarole. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2018;5:520–532. doi: 10.1039/c7en00887b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak S.Y., Giraldo J.P., Wong M.H., Koman V.B., Lew T.T.S., Ell J., Weidman M.C., Sinclair R.M., Landry M.P., Tisdale W.A., et al. A nanobionic light-emitting plant. Nano Lett. 2017;17:7951–7961. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b04369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak S.Y., Lew T.T.S., Sweeney C.J., Koman V.B., Wong M.H., Bohmert-Tatarev K., Snell K.D., Seo J.S., Chua N.H., Strano M.S. Chloroplast-selective gene delivery and expression in planta using chitosan-complexed single-walled carbon nanotube carriers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019;14:447–455. doi: 10.1038/s41565-019-0375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmanan M., Kodama Y., Yoshizumi T., Sudesh K., Numata K. Rapid and efficient gene delivery into plant cells using designed peptide carriers. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:10–16. doi: 10.1021/bm301275g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. The outlook for population growth. Science. 2011;333:569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.1208859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.W., Mahendra S., Zodrow K., Li D., Tsai Y.C., Braam J., Alvarez P.J.J. Developmental phytotoxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles to Arabidopsis thaliana. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010;29:669–675. doi: 10.1002/etc.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Li T., Sun C., Xia J., Jiao Y., Xu H. Selenium-doped carbon quantum dots for free-radical scavenging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;129:10042–10046. doi: 10.1002/ange.201705989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Hu J., Ma C., Wang Y., Wu C., Huang J., Xing B. Uptake, translocation and physiological effects of magnetic iron oxide (γ-Fe2O3) nanoparticles in corn (Zea mays L.) Chemosphere. 2016;159:326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.05.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]